Fascist Italy

Kingdom

of Italy Regno d'Italia (Italian) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1922–1943 | |||||||||||

| Motto: FERT (Motto for the House of Savoy) | |||||||||||

| Anthem: (1861–1943) Marcia Reale d'Ordinanza ("Royal March of Ordinance") (1924–1943) Giovinezza ("Youth")[a] | |||||||||||

All territory ever controlled by Fascist Italy:

| |||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Rome | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Italian | ||||||||||

| Religion | Catholic Christianity | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Italians | ||||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 1900–1946 | Victor Emmanuel III | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

• 1922–1943 | Benito Mussolini | ||||||||||

• 1943 | Pietro Badoglio[b] | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||||

| Senate | |||||||||||

| Chamber of Deputies (1922–1939) Chamber of Fasces and Corporations (1939–1943) | |||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 31 October 1922 | |||||||||||

| 29 August 1923 | |||||||||||

| 11 February 1929 | |||||||||||

| 14 April 1935 | |||||||||||

| 1935–1936 | |||||||||||

| 1936–1939 | |||||||||||

| 7–12 April 1939 | |||||||||||

| 22 May 1939 | |||||||||||

| 10 June 1940 | |||||||||||

| 27 September 1940 | |||||||||||

| 25 July 1943 | |||||||||||

| 3 September 1943 | |||||||||||

| 29 September 1943 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1938 (including colonies)[1] | 3,798,000 km2 (1,466,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1936 | 42,993,602 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Lira (₤) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Fascist Italy (Italian: Italia Fascista) is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy when it was governed by the National Fascist Party from 1922 to 1943 with Benito Mussolini as prime minister and dictator. The Italian Fascists imposed totalitarian rule and crushed political opposition, while simultaneously promoting economic modernization, traditional social values and a rapprochement with the Roman Catholic Church.

According to historian Stanley G. Payne, "[the] Fascist government passed through several relatively distinct phases". The first phase (1922–1925) was nominally a continuation of the parliamentary system, albeit with a "legally-organized executive dictatorship". In foreign policy, Mussolini ordered the Pacification of Libya against rebels in the Italian colonies of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (eventually unified in Italian Libya), inflicted the bombing of Corfu, established a protectorate over Albania, and annexed the city of Fiume into Italy after a treaty with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The second phase (1925–1929) was "the construction of the Fascist dictatorship proper". The third phase (1929–1935) saw less interventionism in foreign policy. The fourth phase (1935–1940) was characterized by an aggressive foreign policy: the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, which was launched from Eritrea and Somaliland; confrontations with the League of Nations, leading to sanctions; growing economic autarky; the invasion of Albania; and the signing of the Pact of Steel. The fifth phase (1940–1943) was World War II itself, ending in military defeat, while the sixth and final phase (1943–1945) was the rump Salò Government under German control.[2]

Italy was a leading member of the Axis powers in World War II, battling with initial success on several fronts. However, after the German-Italian defeat in Africa, the successes of the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front, and the subsequent Allied landings in Sicily, King Victor Emmanuel III overthrew and arrested Mussolini. The new government signed an armistice with the Allies in September 1943. Nazi Germany seized control of the northern half of Italy and rescued Mussolini, setting up the Italian Social Republic (RSI), a collaborationist puppet state which was ruled by Mussolini and Fascist loyalists.

From that point onward, the country descended into civil war, and the large Italian resistance movement continued to wage its guerrilla war against the German and RSI forces. Mussolini was captured and killed by the resistance on 28 April 1945, and hostilities ended the next day. Shortly after the war, civil discontent led to the 1946 institutional referendum on whether Italy would remain a monarchy or become a republic. The Italians decided to abandon the monarchy and form the Italian Republic, the present-day Italian state.

Culture and society

After rising to power, the Fascist regime of Italy set a course to becoming a one-party state and to integrate Fascism into all aspects of life. A totalitarian state was officially declared in the Doctrine of Fascism of 1935:

The Fascist conception of the State is all-embracing; outside of it no human or spiritual values can exist, much less have value. Thus understood, Fascism is totalitarian, and the Fascist State—a synthesis and a unit inclusive of all values—interprets, develops, and potentiates the whole life of a people.

— Doctrine of Fascism, 1935[3]

With the concept of totalitarianism, Benito Mussolini and the Fascist regime set an agenda of improving Italian culture and society based on ancient Rome, personal dictatorship and some futurist aspects of Italian intellectuals and artists.[4] Under Fascism, the definition of the Italian nationality was to rest on a militarist foundation and the Fascist's "new man" ideal, in which loyal Italians would rid themselves of individualism and autonomy and see themselves as a component of the Italian state and be prepared to sacrifice their lives for it.[5] Under such a totalitarian government, only Fascists would be considered "true Italians", and membership and endorsement of the Fascist Party was necessary for people to gain "Complete Citizenship"; those who did not swear allegiance to Fascism would be banished from public life and could not gain employment.[6] The Fascist government also reached out to Italians living overseas to endorse the Fascist cause and identify with Italy rather than their places of residence.[7] Despite efforts to mould a new culture for fascism, Fascist Italy's efforts were not as drastic or successful in comparison to other one-party states like Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in creating a new culture.[8]

Mussolini's propaganda idolized him as the nation's saviour, and the Fascist regime attempted to make him omnipresent in Italian society. Much of Fascism's appeal in Italy was based on Mussolini's popularity and charisma. Mussolini's passionate oratory and the personality cult around him were displayed at huge rallies and parades of his Blackshirts in Rome, which served as an inspiration to Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Germany.

The Fascist regime established propaganda in newsreels, radio broadcasting and a few feature films deliberately endorsing Fascism.[9] In 1926, laws were passed to require that propaganda newsreels be shown prior to all feature films in cinemas.[10] These newsreels were more effective in influencing the public than propaganda films or radio, as few Italians had radio receivers at the time. Fascist propaganda was widely present in posters and state-sponsored art. However, artists, writers and publishers were not strictly controlled: they were only censored if they were blatantly against the state. There was a constant emphasis on the masculinity of the "new Italian", stressing aggression, virility, youth, speed and sport.[11] Women were to attend to motherhood and stay out of public affairs.[12]

General elections were held in the form of a referendum on 24 March 1929. By this time, the country was a single-party state with the National Fascist Party (PNF) as the only legally permitted party. Mussolini used a referendum to confirm a fascist single-party list. The list put forward was ultimately approved by 98.43% of voters.[13] The universal male suffrage, which was legal since 1912, was restricted to men who were members of a trade union or an association, to soldiers and to members of the clergy. Consequently, only 9.5 million people were able to vote.

Roman Catholic Church

In 1870, the newly formed Kingdom of Italy annexed the remaining Papal States, depriving the Pope of his temporal power. Relations with the Roman Catholic Church improved significantly during Mussolini's tenure. Despite earlier opposition to the Church, after 1922 Mussolini made an alliance with the Catholic Partito Popolare Italiano (Italian People's Party). In 1929, Mussolini and the papacy came to an agreement that ended the bitter standoff between the Church from the Italian government going back to 1860. The Orlando government had begun the process of reconciliation during World War I and the Pope furthered it by cutting ties with the Christian Democrats in 1922.[14] Mussolini and the leading Fascists were anti-clericals and atheists, but they recognized the advantages of warmer relations with Italy's large Roman Catholic element.[15]

The Lateran Accord of 1929 was a treaty that recognized the Pope as the head of the new city-state of Vatican City within Rome, which gave it independent status and made it an important hub of world diplomacy. The Concordat of 1929 made Roman Catholicism the sole religion of the State[a] (although other religions were tolerated), paid salaries to priests and bishops, recognized religious marriages (previously couples had to have a civil ceremony) and brought religious instruction into the public schools. In turn, the bishops swore allegiance to the Italian Fascist régime, which had a veto power over their selection. A third agreement paid the Vatican 1.75 billion lire (about $100 million) for the seizures of Church property since 1860. The Catholic Church was not officially obliged to support the Fascist régime and the strong differences remained, but the general hostility ended. The Church especially endorsed foreign policies such as support for the Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War and for the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. Friction continued over the Catholic Action (Azione Cattolica) youth network, which Mussolini wanted to merge into his Fascist youth group.[17] In 1931, Pope Pius XI issued the encyclical Non abbiamo bisogno ("We do not need") that denounced the regime's persecution of the Church in Italy and condemned "pagan worship of the state".[18]

Clerical fascism

The 1929 treaties with Mussolini partially recovered the Papacy's spiritual primacy in Italy, making the Pope sovereign in the Vatican City state,[16] and restoring Roman Catholicism as the State religion.[16][19] In March 1929, a nationwide plebiscite was held to publicly endorse the Treaty. Opponents were intimidated by the Fascist régime, the Catholic Action party instructed Catholics to vote for Fascist candidates, and Mussolini claimed that the only "no" votes were of those "few ill-advised anti-clericals who refuse to accept the Lateran Pacts".[20] Nearly 9 million Italians voted (90% of the registered electorate), and only 136,000 voted "no".[21] The Lateran Treaty remains in place today.

In 1938, the Italian Racial Laws and the Manifesto of Race were promulgated by the Fascist régime, designed to outlaw and persecute both Italian Jews[22] and Protestant Christians,[19][23][24] especially Evangelicals and Pentecostals.[23][24]

In January 1939, The Jewish National Monthly reported "the only bright spot in Italy has been the Vatican, where fine humanitarian statements by the Pope have been issuing regularly". When Mussolini's anti-Semitic decrees began depriving Jews of employment in Italy, Pius XI personally admitted professor Vito Volterra, a famous Italian Jewish mathematician, into the Pontifical Academy of Science.[25]

Despite Mussolini's close alliance with Hitler's Germany, Italy did not fully adopt Nazism's genocidal ideology towards the Jews. The Nazis were frustrated by the Italian authorities' refusal to co-operate in the round-ups of Jews, and no Jews were deported prior to the formation of the Italian Social Republic puppet-state following the Armistice of Cassibile.[26] In the Italian-occupied Independent State of Croatia, German envoy Siegfried Kasche advised Berlin that Italian forces had "apparently been influenced" by Vatican opposition to German anti-Semitism.[27] As anti-Axis feeling grew in Italy, the use of Vatican Radio to broadcast papal disapproval of race murder and anti-Semitism angered the Nazis.[28]

Mussolini was overthrown in July 1943, the Germans moved to occupy Italy, and they also commenced a round-up of Jews. Thousands of Italian Jews and a small number of Protestants died in the Nazi concentration camps.[22][24]

Antisemitism

Until he formed his alliance with Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini always denied the existence of antisemitism within the National Fascist Party (PNF). In the early 1920s, Mussolini wrote an article which stated that Fascism would never elevate a "Jewish Question" and the article also stated that "Italy knows no antisemitism and we believe that it will never know it" and then, the article elaborated "let us hope that Italian Jews will continue to be sensible enough so as not to give rise to antisemitism in the only country where it has never existed".[29] In 1932, during a conversation with Emil Ludwig, Mussolini described antisemitism as a "German vice" and stated: "There was 'no Jewish Question' in Italy and could not be one in a country with a healthy system of government".[30] On several occasions, Mussolini spoke positively about Jews and the Zionist movement.[31] Mussolini had initially rejected Nazi racism, especially the idea of a master race, as "arrant nonsense, stupid and idiotic".[32]

In 1929, Mussolini acknowledged the contributions which Italian Jews had made to Italian society, despite their minority status, and he also believed that Jewish culture was Mediterranean, aligning his early opinion of Italian Jews with his early Mediterraneanist perspective. He also argued that Jews were natives of Italy, after living on the Italian Peninsula for a long period of time.[33] In the early 1930s, Mussolini held discussions with Zionist leadership figures over proposals to encourage the emigration of Italian Jews to the mandate of Palestine, as Mussolini hoped that the presence of pro-Italian Jews in the region would weaken pro-British sentiment and potentially overturn the British mandate.[34]

On the issue of antisemitism, the Fascists were divided on what to do, especially after the rise of Hitler in Germany. A number of members of the Fascist Party were Jewish and Mussolini affirmed that he was a Zionist,[35] but to appease Hitler, antisemitism within the Fascist Party steadily increased. In 1936, Mussolini made his first written denunciation of Jews by claiming that antisemitism had only arisen because Jews had become too predominant in the positions of power of countries and claimed that Jews were a "ferocious" tribe who sought to "totally banish" Christians from public life.[36] In 1937, Fascist member Paolo Orano criticized the Zionist movement as being part of British foreign policy which designed to secure British hold of the area without respecting the Christian and Islamic presence in Palestine. On the matter of Jewish Italians, Orano said that they "should concern themselves with nothing more than their religion" and not bother boasting of being patriotic Italians.[37]

The major source of friction between National Socialist Germany and Fascist Italy was Italy's stance on Jews. In his early years as Fascist leader, Mussolini believed in racial stereotypes of Jews, however, he did not hold firm to any concrete stance on Jews because he changed his personal views and his official stance on them in order to meet the political demands of the various factions of the Fascist movement.[38] Of the 117 original members of the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento founded on 23 March 1919, five were Jewish.[39] Since the movement's early years, there were a small number of prominent openly antisemitic Fascists such as Roberto Farinacci.[40] There were also prominent Fascists who completely rejected antisemitism, such as Italo Balbo, who lived in Ferrara, which had a substantial Jewish community that was widely accepted and suffered few antisemitic incidents.[41] Mussolini initially had no antisemitic statements in his policies.[42] However, in response to his observation of large numbers of Jews amongst the Bolsheviks and claims (that were later confirmed to be true) that the Bolsheviks and Germany (that Italy was fighting in World War I) were politically connected, Mussolini made antisemitic statements involving the Bolshevik-German connection as being "an unholy alliance between Hindenburg and the synagogue".[42] Mussolini came to believe rumors that Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin was of Jewish descent.[42] Mussolini attacked the Jewish banker Giuseppe Toeplitz of Banca Commerciale Italiana by claiming that he was a German agent and traitor of Italy.[43] In an article in Il Popolo d'Italia in June 1919, Mussolini wrote a highly antisemitic analysis on the situation in Europe involving Bolshevism following the October Revolution, the Russian Civil War and war in Hungary involving the Hungarian Soviet Republic.[43] In June 1919, Mussolini wrote on Il Popolo d'Italia:

If Petrograd (Pietrograd) does not yet fall, if [General] Denikin is not moving forward, then this is what the great Jewish bankers of London and New York have decreed. These bankers are bound by ties of blood to those Jews who in Moscow as in Budapest are taking their revenge on the Aryan race that has condemned them to dispersion for so many centuries. In Russia, 80 percent of the managers of the Soviets are Jews, in Budapest 17 out of 22 people's commissars are Jews. Might it not be that bolshevism is the vendetta of Judaism against Christianity?? It is certainly worth pondering. It is entirely possible that bolshevism will drown in the blood of a pogrom of catastrophic proportions. World finance is in the hands of the Jews. Whoever owns the strongboxes of the peoples is in control of their political systems. Behind the puppets (making peace) in Paris, there are the Rothschilds, the Warburgs, the Schiffs, the Guggenheims who are of the same blood who are conquering Petrograd and Budapest. Race does not betray race ... Bolshevism is a defense of the international plutocracy. This is the basic truth of the matter. The international plutocracy dominated and controlled by Jews has a supreme interest in all of Russian life accelerating its process of disintegration to the point of paroxysm. A Russia that is paralyzed, disorganized, starved, will be a place where tomorrow the bourgeoisie, yes the bourgeoisie, o proletarians will celebrate its spectacular feast of plenty.[43]

Mussolini's statement on a Jewish-Bolshevik-plutocratic connection and conspiracy was met with opposition in the Fascist movement, leading Mussolini to respond to this opposition amongst his supporters by abandoning and reversing this stance shortly afterward in 1919.[42] In reversing his stance due to opposition to it, Mussolini no longer expressed his previous assertion that Bolshevism was Jewish, but warned that—due to the large numbers of Jews in the Bolshevik movement—the rise of Bolshevism in Russia would result in a ferocious wave of anti-Semitism in Russia.[42] He then claimed that "anti-Semitism is foreign to the Italian people", but warned Zionists that they should be careful not to stir up antisemitism in "the only country where it has not existed".[42] One of the Jewish financial supporters of the Fascist movement was Toeplitz, whom Mussolini had earlier accused of being a traitor during World War I.[44] Early on there were prominent Jewish Italian Fascists such as Aldo Finzi,[44] who was born of a mixed marriage of a Jewish and Christian Italian and was baptized as a Roman Catholic.[45] Another prominent Jewish Italian Fascist was Ettore Ovazza, who was a vocal Italian nationalist and an opponent of Zionism in Italy.[46] 230 Italian Jews took part in the Fascists' March on Rome in 1922.[39] In 1932, Mussolini made his private attitude about Jews known to the Austrian ambassador when discussing the issue of the antisemitism of Hitler, saying: "I have no love for the Jews, but they have great influence everywhere. It is better to leave them alone. Hitler's anti-Semitism has already brought him more enemies than is necessary".[42]

At the 1934 Montreux Fascist conference which was chaired by the Italian-led Comitati d'Azione per l'Universalita di Roma (CAUR) in an attempt to found a Fascist International, the issue of antisemitism was debated amongst representatives of various fascist parties, some of them were more favorable to it than others were. Two final compromises were adopted, resulting in the official stance of the Fascist International:

[T]he Jewish question cannot be converted into a universal campaign of hatred against the Jews ... Considering that in many places certain groups of Jews are installed in conquered countries, exercising in an open and occult manner an influence injurious to the material and moral interests of the country which harbors them, constituting a sort of state within a state, profiting by all benefits and refusing all duties, considering that they have furnished and are inclined to furnish, elements conducive to international revolution which would be destructive to the idea of patriotism and Christian civilization, the Conference denounces the nefarious action of these elements and is ready to combat them.[47]

Italian Fascism adopted antisemitism in the late 1930s and as a result, Mussolini personally returned to his earlier invokation of antisemitic statements.[48] From 1937 to 1938, during the Spanish Civil War, the Fascist regime circulated antisemitic propaganda which stated that Italy was supporting Spain's Nationalist forces in their fight against a "Jewish International".[48] The Fascist regime's adoption of official antisemitic racial doctrine in 1938 met opposition from Fascist members including Balbo, who regarded antisemitism as having nothing to do with Fascism and staunchly opposed the antisemitic laws.[41]

In 1938, under pressure from Germany, Mussolini ordered the regime to adopt an antisemitic policy, a policy which was extremely unpopular within Italy as well as within the Fascist Party itself. As a result of this policy, the Fascist regime lost its propaganda director, Margherita Sarfatti, who was Jewish and had previously been Mussolini's mistress. A minority of high-ranking Fascists were pleased with the antisemitic policy such as Roberto Farinacci, who claimed that Jews had taken control of key positions in finance, business and schools through intrigue, accused Jews of sympathizing with Ethiopia during Italy's war with it and accused Jews of sympathizing with Republican Spain during the Spanish Civil War.[49] In 1938, Farinacci became the minister in charge of culture and he also adopted racial laws which were designed to prevent racial intermixing, including antisemitic laws. Until the armistice with the Allies in September 1943, the Italian Jewish community was protected from deportation to the German death camps in the east. With the armistice, Hitler took control of the German-occupied territory in the North and he also launched an effort to liquidate the Jewish community which was under his control. Shortly after the entry of Italy into the war, numerous camps were established for the imprisonment of enemy aliens and Italians suspected to be hostile to the regime. In contrast to the brutality of the National Socialist-run camps, the Italian camps allowed families to live together and there was a broad program of social welfare and cultural activities.[50]

Antisemitism was unpopular within Italy, and it was also unpopular within the Fascist Party. Once, when a Fascist scholar protested about the treatment of his Jewish friends to Mussolini, Mussolini reportedly stated: "I agree with you entirely. I don't believe a bit in the stupid anti-Semitic theory. I am carrying out my policy entirely for political reasons".[51]

Education

The Fascist government endorsed a stringent education policy in Italy aiming at eliminating illiteracy, which was a serious problem in Italy at the time, as well as improving the allegiance of Italians to the state.[52] To reduce drop-outs, the government changed the minimum age of leaving school from twelve to fourteen and strictly enforced attendance.[53] The Fascist government's first minister of education from 1922 to 1924 Giovanni Gentile recommended that education policy should focus on indoctrination of students into Fascism and to educate youth to respect and be obedient to authority.[53] In 1929, education policy took a major step towards being completely taken over by the agenda of indoctrination.[53] In that year, the Fascist government took control of the authorization of all textbooks, all secondary school teachers were required to take an oath of loyalty to Fascism and children began to be taught that they owed the same loyalty to Fascism as they did to God.[53] In 1933, all university teachers were required to be members of the National Fascist Party.[53] From the 1930s to 1940s, Italy's education focused on the history of Italy displaying Italy as a force of civilization during the Roman era, displaying the rebirth of Italian nationalism and the struggle for Italian independence and unity during the Risorgimento.[53] In the late 1930s, the Fascist government copied Nazi Germany's education system on the issue of physical fitness and began an agenda that demanded that Italians become physically healthy.[53]

Intellectual talent in Italy was rewarded and promoted by the Fascist government through the Royal Academy of Italy which was created in 1926 to promote and coordinate Italy's intellectual activity.[54]

Social welfare

A major success in social policy in Fascist Italy was the creation of the Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro (OND) or "National After-work Program" in 1925. The OND was the state's largest recreational organizations for adults.[55] The Dopolavoro was so popular that by the 1930s all towns in Italy had a Dopolavoro clubhouse and the Dopolavoro was responsible for establishing and maintaining 11,000 sports grounds, over 6,400 libraries, 800 movie houses, 1,200 theaters and over 2,000 orchestras.[55] Membership was voluntary and nonpolitical. In the 1930s, under the direction of Achille Starace, the OND became primarily recreational, concentrating on sports and other outings. It is estimated that by 1936 the OND had organized 80% of salaried workers.[56] Nearly 40% of the industrial workforce had been recruited into the Dopolavoro by 1939 and the sports activities proved popular with large numbers of workers. The OND had the largest membership of any of the mass Fascist organizations in Italy.[57] The enormous success of the Dopolavoro in Fascist Italy prompted Nazi Germany to create its own version of the Dopolavoro, the Kraft durch Freude (KdF) or "Strength through Joy" program, which was even more successful than the Dopolavoro.[58]

Another organization the Opera Nazionale Balilla (ONB) was widely popular and provided young people with access to clubs, dances, sports facilities, radios, concerts, plays, circuses and outdoor hikes at little or no cost. It sponsored tournaments and sports festivals.[59]

Between 1928 and 1930, the government introduced pensions, sick pay and paid holidays.[60] In 1933, the government established unemployment benefits.[60] At the end of the 1930s, 13 million Italians were enrolled in the state health insurance scheme and by 1939 social security expenditure accounted for 21% of government spending.[61] In 1935, the 40-hour working week was introduced and workers were expected to spend Saturday afternoons engaged in sporting, paramilitary and political activities.[62][63] This was called Sabato fascista ("Fascist Saturday") and was aimed mainly at the young; exceptions were granted in special cases but not for those under 21.[63] According to Tracy H. Koon, this scheme failed as most Italians preferred to spend Saturday as a day of rest.[63]

Police state and military

For security of the regime, Mussolini advocated complete state authority and created the Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale ("National Security Volunteer Militia") in 1923, which are commonly referred to as "Blackshirts" for the color of their Royal Italian Army, Navy, and Air Force uniforms. Most of the Blackshirts were members from the Fasci di Combattimento. A secret police force called the Organizzazione di Vigilanza Repressione dell'Antifascismo ("Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism") or OVRA was created in 1927. It was led by Arturo Bocchini to crack down on opponents of the regime and Mussolini (there had been several near-miss assassination attempts on Mussolini's life in his early years in power). Although the OVRA were responsible for far fewer deaths than the Schutzstaffel (SS) in Germany or the NKVD of the Soviet Union, they were nevertheless highly effective in terrorizing political opponents. One of their most notorious methods of torture involved physically forcing opponents of Fascism to swallow castor oil, which would cause severe diarrhea and dehydration, leaving the victim in a physically debilitated state that occasionally resulted in death.[64]

To combat Italian organized crime, notably the Cosa Nostra in Sicilia and the 'Ndrangheta in Calabria, the Fascist government gave special powers in 1925 to Cesare Mori, the prefect of Palermo.[65] These powers gave him the ability to prosecute the Mafia, forcing many Mafiosi to flee abroad (many to the United States) or risk being jailed.[66] However, Mori was fired when he began to investigate Mafia links within the Fascist regime and was removed from his position in 1929, when the Fascist regime declared that the threat of the Mafia had been eliminated. Mori's actions weakened the Mafia, but did not destroy them. From 1929 to 1943 the Fascist regime completely abandoned its previously aggressive measures against the Mafia, and the Mafiosi were left relatively undisturbed.[67]

Women

The Fascists paid special attention to the role of women, from elite society women to factory workers[68] and peasants.[69] Fascist leaders sought to "rescue" women from experiencing emancipation even as they trumpeted the advent of the "new Italian woman" (nuova italiana).[70] The policies revealed a deep conflict between modernity and traditional patriarchal authority, as Catholic, Fascist and commercial models of conduct competed to shape women's perceptions of their roles and their society at large. The Fascists celebrated violent "virilist" politics and exaggerated its machismo while also taxing celibate men to pay for child welfare programs. Italy's invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 and the resulting League of Nations sanctions shaped the tasks assigned to women within the Fascist Party. The empire and women's contribution to it became a core theme in Fascist propaganda. Women in the party were mobilized for the imperial cause both as producers and as consumers, giving them new prominence in the nation. The Fascist women's groups expanded their roles to cover such new tasks as running training courses on how to fight waste in housework. Young Italian women were prepared for a role in Italy's "place in the sun" through special courses created to train them for a future as colonial wives.[71]

The government tried to achieve "alimentary sovereignty", or total self-sufficiency with regard to food supplies. Its new policies were highly controversial among a people who paid serious attention to their food. The goal was to reduce imports, support Italian agriculture and encourage an austere diet based on bread, polenta, pasta, fresh produce and wine. Fascist women's groups trained women in "autarkic cookery" to work around items no longer imported. Food prices climbed in the 1930s and dairy and meat consumption was discouraged, while increasing numbers of Italians turned to the black market. The policy demonstrated that Fascists saw food—and people's behavior generally—as strategic resources that could be manipulated regardless of traditions and tastes.[72]

Economy

Mussolini and the Fascist Party promised Italians a new economic system known as corporatism (or tripartism), the creation of profession-wide corporations, in which the trade union and employers organisation belonging to the same profession or branch are organized into professional corporations. In 1935, the Doctrine of Fascism was published under Mussolini's name, although it was most likely written by Giovanni Gentile. It described the role of the state in the economy under corporatism. By this time, Fascism had been drawn more towards the support of market forces being dominant over state intervention. A passage from the Doctrine of Fascism read:

The corporate State considers that private enterprise in the sphere of production is the most effective and useful instrument in the interest of the nation. In view of the fact that private organisation of production is a function of national concern, the organiser of the enterprise is responsible to the State for the direction given to production. State intervention in economic production arises only when private initiative is lacking or insufficient, or when the political interests of the State are involved. This intervention may take the form of control, assistance or direct management.[73]

Fascists claimed that this system would be egalitarian and traditional at the same time. The economic policy of corporatism quickly faltered; the left-wing elements of the Fascist manifesto were opposed by industrialists and landowners who supported the party because it pledged to defend Italy from socialism, and corporatist policy became dominated by the industries. Initially, economic legislation mostly favoured the wealthy industrial and agrarian classes by allowing privatization, liberalization of rent laws, tax cuts, and administrative reform; however, economic policy changed drastically following the Matteotti Crisis where Mussolini began pushing for a totalitarian state. In 1926, the Syndical Laws, also known as the Rocco Laws, were passed, organizing the economy into twelve separate employer and employee unions.[74] The unions were largely state-controlled and were mainly used to suppress opposition and reward political loyalty. While the Fascist unions could not protect workers from all economic consequences, they were responsible for the handling of social security benefits, claims for severance pay, and could sometimes negotiate contracts that benefited workers.[75]

After the Great Depression hit the world economy in 1929, the Fascist regime followed other nations in enacting protectionist tariffs and attempted to set direction for the economy. In the 1930s, the government increased wheat production and made Italy self-sufficient for wheat, ending imports of wheat from Canada and the United States.[76] However, the transfer of agricultural land to wheat production reduced the production of vegetables and fruit.[76] Despite improving production for wheat, the situation for peasants themselves did not improve, as 0.5% of the Italian population (usually wealthy) owned 42% of all agricultural land in Italy[77] and income for peasants did not increase while taxes did increase.[77] The Depression caused unemployment to rise from 300,000 to 1 million in 1933.[78] It also caused a 10% drop in real income and a fall in exports. Italy fared better than most western nations during the Depression: its welfare services did reduce the impact of the Depression.[78] Its industrial growth from 1913 to 1938 was even greater than that of Germany for the same time period. Only the United Kingdom and the Scandinavian nations had a higher industrial growth during that period.[78]

Italy's colonial expansion into Ethiopia in 1936 proved to have a negative impact on Italy's economy. The budget of the colony of Italian East Africa in the 1936–1937 fiscal year requested from Italy 19.136 billion lire to be used to create the necessary infrastructure for the colony.[79] Italy's entire revenue that year was only 18.581 billion lire.[80]

Technology and modernization

In 1933, Italy made multiple technological achievements. The Fascist government spent large sums of money on technological projects such as the construction of the Italian ocean liner SS Rex, which in 1933 made a transatlantic sea crossing record of four days,[81] funded the development of the Macchi M.C.72 seaplane, which became the world's fastest seaplane in 1933 and retained the title in 1934.[82] In 1933, Fascist government member Italo Balbo, who was also an aviator, made a transatlantic flight in a flying boat to Chicago for the World's Fair known as the Century of Progress.[83]

Foreign policy

Stephen Lee identifies three major themes in Mussolini's foreign policy. The first was a continuation of the foreign-policy objectives of the preceding Liberal regime. Liberal Italy had allied itself with Germany and Austria and had great ambitions in the Balkans and North Africa. It had been badly defeated in Ethiopia in 1896, when there was a strong demand for seizing that country. Second was a profound disillusionment after the heavy losses of the First World War. In the eyes of many Italians the small territorial gains from Austria-Hungary were not enough to compensate for the war's terrible costs, especially since countries, such as Poland and Yugoslavia, who contributed far less to the allied victory but received much more. Third was Mussolini's promise to restore the pride and glory of the old Roman Empire.[84]

Mussolini promised to revive Italy's status as a Great Power in Europe, carving out a "New Roman Empire". Mussolini promised that Italy would dominate the Mediterranean Sea. In propaganda, the Fascist government used the originally ancient Roman term "Mare Nostrum" (Latin for "Our Sea") to refer to the Mediterranean Sea. The Fascist regime increased funding and attention to military projects and began plans to create an Italian Empire in Northern and Eastern Africa and reclaim dominance in the Mediterranean Sea and Adriatic Sea. The Fascists launched wars to conquer Dalmazia, Albania and Greece for the Italian Empire.

Africa

Colonial efforts in Africa began in the 1920s, as civil war plagued Italian North Africa (Africa Settentrionale Italiana, or ASI) as the Arab population there refused to accept Italian colonial government. Mussolini sent Marshal Rodolfo Graziani to lead a punitive pacification campaign against the Arab nationalists. Omar Mukhtar led the Arab resistance movement. After a much-disputed truce on 3 January 1928, the Fascist policy in Libya increased in brutality. A barbed wire fence was built from the Mediterranean Sea to the oasis of Jaghbub to sever lines critical to the resistance. Soon afterwards, the colonial administration began the wholesale deportation of the people of the Jebel Akhdar to deny the rebels the support of the local population. The forced migration of more than 100,000 people ended in concentration camps in Suluq and Al-'Aghela where tens of thousands died in squalid conditions. It is estimated that the number of Libyans who died – killed either through combat or starvation and disease – was at least 80,000, including up to half of the Cyrenaican population. After Al-Mukhtar's capture on 15 September 1931 and his execution in Benghazi, the resistance petered out. Limited resistance to the Italian occupation crystallized around Sheik Idris, the Emir of Cyrenaica.[85]

Negotiations on expanding the borders of the colony of Libya took place with the British government. The first negotiations began in 1925 to define the border between Libya and British-held Egypt. These negotiations resulted in Italy gaining previously undefined territory.[86] In 1934, once again the Italian government requested more territory for Libya from British-held Sudan. The United Kingdom allowed Italy to gain some territory from Sudan to add to Libya.[86]

In 1935, Mussolini believed that the time was right for Italy to invade Ethiopia (also known as Abyssinia) to make it a colony. As a result, the Second Italo-Abyssinian War erupted. Italy invaded Ethiopia from the Italian colonies of Eritrea and Somaliland. Italy committed atrocities against the Ethiopians during the war, including the use of aircraft to drop poison gas on the defending Ethiopian soldiers. Ethiopia surrendered in 1936, completing Italy's revenge for its failed colonial conquest of the 1890s. King Victor Emmanuel III was soon proclaimed Emperor of Ethiopia. The international consequences for Italy's belligerence resulted in its diplomatic isolation. France and Britain quickly abandoned their trust of Mussolini but failed to take decisive action. Italy's actions were formally condemned by the League of Nations, prompting a Grand Council of Fascism vote to withdraw from the League on 11 December 1937 and Mussolini denounced the League as a mere "tottering temple".[87]

Racial Laws

Until 1938, Mussolini had denied any antisemitism within Fascist Italy and dismissed the racial policies of Nazi Germany. However, by mid-1938 Hitler's influence over Mussolini had persuaded him to make a specific agenda on race, the Fascist regime moved away from its previous promotion of colonialism based on the spread of Italian culture to a directly race-oriented colonial agenda.

In 1938, Fascist Italy passed the Manifesto of Race which stripped Jews of their Italian citizenship and prohibited them from any professional position. The Racial Laws declared that Italians were of the Aryan race and forbid sexual relations and marriages between Italians and Jews or Africans.[88] The final decision about the Racial Laws was made during the meeting of the Gran Consiglio del Fascismo, which took place on the night between 6 and 7 of October 1938 in Rome, Palazzo Venezia. Not all Italian Fascists supported discrimination: while the pro-German, anti-Jewish Roberto Farinacci and Giovanni Preziosi strongly pushed for them, Italo Balbo strongly opposed the Racial Laws. Balbo, in particular, regarded antisemitism as having nothing to do with fascism and staunchly opposed the antisemitic laws.[89] The Fascist regime declared that it would promote mass Italian settlements in the colonies that would—in the Fascist government's terms—"create in the heart of the African continent a powerful and homogeneous nucleus of whites strong enough to draw those populations within our economic orbit and our Roman and Fascist civilization".[90]

Fascist rule in its Italian colonies differed from region to region. Rule in Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana, or AOI), a colony including Ethiopia, Eritrea and Italian Somaliland, was harsh for the native peoples as Fascist policy sought to destroy native culture. In February 1937, Rodolfo Graziani ordered Italian soldiers to pillage native settlements in Addis Ababa, which resulted in hundreds of Ethiopians being killed and their homes being burned to the ground.[91] After the occupation of Ethiopia, the Fascist government endorsed racial segregation to reduce the number of mixed offspring in Italian colonies, which they claimed would "pollute" the Italian race.[92] Marital and sexual relationships between Italians and Africans in its colonies were made a criminal offense when the Fascist regime implemented decree-law No. 880 19 April 1937 which gave sentences of one to five years imprisonment to Italians caught in such relationships.[92] The law did not give any sentences to native Africans, as the Fascist government claimed that only those Italians were to blame for damaging the prestige of their race.[92] Despite racist language used in some propaganda, the Fascist regime accepted recruitment of native Africans who wanted to join Italy's colonial armed forces and native African colonial recruits were displayed in propaganda.[93][94]

Fascist Italy embraced the "Manifesto of the Racial Scientists" which embraced biological racism and it declared that Italy was a country populated by people of Aryan origin, Jews did not belong to the Italian race and that it was necessary to distinguish between Europeans and Jews, Africans and other non-Europeans.[95] The manifesto encouraged Italians to openly declare themselves as racists, both publicly and politically.[96] Fascist Italy often published material that showed caricatures of Jews and Africans.[97]

In Italian Libya, Mussolini downplayed racist policies as he attempted to earn the trust of Arab leaders there. Individual freedom, inviolability of home and property, right to join the military or civil administrations and the right to freely pursue a career or employment were guaranteed to Libyans by December 1934.[92] In a famous trip to Libya in 1937, a propaganda event was created when on 18 March Mussolini posed with Arab dignitaries who gave him an honorary "Sword of Islam" (that had actually been crafted in Florence), which was to symbolize Mussolini as a protector of the Muslim Arab peoples there.[98] In 1939, laws were passed that allowed Muslims to be permitted to join the National Fascist Party and in particular the Muslim Association of the Lictor (Associazione Musulmana del Littorio) for Islamic Libya and the 1939 reforms allowed the creation of Libyan military units within the Italian Army.[99]

Balkans

The Fascist regime also engaged in an interventionist foreign policy in Europe. In 1923, Italian soldiers captured the Greek island of Corfu as part of the Fascists' plan to eventually take over Greece. Corfu was later returned to Greece and war between Greece and Italy was avoided. In 1925, Italy forced Albania to become a de facto protectorate which helped Italy's stand against Greek sovereignty. Corfu was important to Italian imperialism and nationalism due to its presence in the former Republic of Venice which left behind significant Italian cultural monuments and influence, though the Greek population there (especially youth) heavily protested the Italian occupation.

Relations with France were mixed: the Fascist regime consistently had the intention to eventually wage war on France to regain Italian-populated areas of France,[100] but with the rise of Hitler the Fascists immediately became more concerned of Austria's independence and the potential threat of Germany to Italy, if it demanded the German-populated areas of Tyrol. Due to concerns of German expansionism, Italy joined the Stresa Front with France and Britain against Germany which existed from 1935 to 1936. This followed a previous treaty with the Soviet Union aimed against Germany: the Italo-Soviet Pact.[101]

The Fascist regime held negative relations with Yugoslavia, as they long wanted the implosion of Yugoslavia in order to territorially expand and increase Italy's power. Italy pursued espionage in Yugoslavia, as Yugoslav authorities on multiple occasions discovered spy rings in the Italian Embassy in Yugoslavia, such as in 1930.[100] In 1929, the Fascist government accepted Croatian extreme nationalist Ante Pavelić as a political exile to Italy from Yugoslavia. The Fascists gave Pavelić financial assistance and a training ground in Italy to develop and train his newly formed fascist militia and terrorist group, the Ustaše. This organization later became the governing force of the Independent State of Croatia, and murdered hundreds of thousands of Serbs, Jews and Roma during World War II.[102]

After Germany annexed Czechoslovakia, Mussolini turned his attention to Albania. On 7 April 1939, Italy invaded the country and after a short campaign, Albania was occupied, turned into a protectorate and its parliament crowned Victor Emmanuel III King of Albania. The historical justification for the annexation of Albania laid in the ancient history of the Roman Empire in which the region of Albania had been an early conquest for the Romans, even before Northern Italy had been taken by Roman forces. However, by the time of annexation little connection to Italy remained amongst Albanians. Albania was very closely tied to Italy even before the Italian invasion. Italy had built up heavy influence over Albania through the Treaties of Tirana, which gave Italy concessions over the Albanian economy and army. The occupation was not appreciated by King Emmanuel III, who feared that it had isolated Italy even further than its war against Ethiopia.[103]

Spain

As the conquest of Ethiopia in the Second Italo-Ethiopian War made the Italian government confident in its military power, Benito Mussolini joined the war to secure Fascist control of the Mediterranean,[104] supporting the Nationalists to a greater extent than Nazi Germany did.[105] The Royal Italian Navy (Italian: Regia Marina) played a substantial role in the Mediterranean blockade, and ultimately Italy supplied machine guns, artillery, aircraft, tankettes, the Aviazione Legionaria, and the Corpo Truppe Volontarie (CTV) to the Nationalist cause.[106] The Italian CTV would, at its peak, supply the Nationalists with 50,000 men.[106] Italian warships took part in breaking the Republican navy's blockade of Nationalist-held Spanish Morocco and took part in naval bombardment of Republican-held Málaga, Valencia, and Barcelona.[107] In addition, the Italian air force made air raids of some note, targeting mainly cities and civilian targets.[108] These Italian commitments were heavily propagandised in Italy proper, and became a point of fascist pride.[108] In total, Italy provided the Nationalists with 660 planes, 150 tanks, 800 artillery pieces, 10,000 machine guns, and 240,747 rifles.[109]

Italian military for war and improve relations with the Roman Catholic Church. It was a success that secured Italy's naval access in and out of the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean and its ability to pursue its policy of Mare Nostrum without fear of opposition by Spain. The other major foreign contributor to the Spanish Civil War was Germany. This was the first time that Italian and German forces fought together since the Franco-Prussian War in the 1870s. During the 1930s, Italy built many large battleships and other warships to solidify Italy's hold on the Mediterranean Sea.

Germany

When the Nazi Party attained power in Germany in 1933, Mussolini and the Fascist regime in public showed approval of Hitler's regime, with Mussolini saying: "The victory of Hitler is our victory".[110] The Fascist regime also spoke of creating an alliance with the new regime in Germany.[111] In private, Mussolini and the Italian Fascists showed disapproval of the National Socialist government and Mussolini had a disapproving view of Hitler despite ideological similarities. The Fascists distrusted Hitler's Pan-German ideas which they saw as a threat to territories in Italy that previously had been part of the Austrian Empire. Although other National Socialists disapproved of Mussolini and Fascist Italy, Hitler had long idolized Mussolini's oratorical and visual persona and adopted much of the symbolism of the Fascists into the National Socialist Party, such as the Roman, straight-armed salute, dramatic oratory, the use of uniformed paramilitaries for political violence and the use of mass rallies to demonstrate the power of the movement. In 1922, Hitler tried to ask for Mussolini's guidance on how to organize his own version of the "March on Rome" which would be a "March on Berlin" (which came into being as the failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923). Mussolini did not respond to Hitler's requests as he did not have much interest in Hitler's movement and regarded Hitler to be somewhat crazy.[112] Mussolini did attempt to read Mein Kampf to find out what Hitler's National Socialist movement was, but was immediately disappointed, saying that Mein Kampf was "a boring tome that I have never been able to read" and remarked that Hitler's beliefs were "little more than commonplace clichés".[100] While Mussolini like Hitler believed in the cultural and moral superiority of whites over colored peoples,[92] he opposed Hitler's antisemitism. A number of Fascists were Jewish, including Mussolini's mistress Margherita Sarfatti, who was the director of Fascist art and propaganda, and there was little support amongst Italians for antisemitism. Mussolini also did not evaluate race as being a precursor of superiority, but rather culture.

Hitler and the National Socialists continued to try to woo Mussolini to their cause and eventually Mussolini gave financial assistance to the Nazi Party and allowed National Socialist paramilitaries to train in Italy in the belief that despite differences, a nationalist government in Germany could be beneficial to Italy.[100] As suspicion of the Germans increased after 1933, Mussolini sought to ensure that Germany would not become the dominant nationalist state in Europe. To do this, Mussolini opposed German efforts to annex Austria after the assassination of fascist Austrian President Engelbert Dollfuss in 1934 and promised the Austrians military support if Germany were to interfere. This promise helped save Austria from annexation in 1934.

Public appearances and propaganda constantly portrayed the closeness of Mussolini and Hitler and the similarities between Italian Fascism and German National Socialism. While both ideologies had significant similarities, the two factions were suspicious of each other and both leaders were in competition for world influence. Hitler and Mussolini first met in June 1934, as the issue of Austrian independence was in crisis. In private after the visit in 1934, Mussolini said that Hitler was just "a silly little monkey".

After Italy became isolated in 1936, the government had little choice but to work with Germany to regain a stable bargaining position in international affairs and reluctantly abandoned its support of Austrian independence from Germany. In September 1937, Mussolini visited Germany in order to build closer ties with his German counterpart.[113] On 28 October 1937, Mussolini declared Italy's support of Germany regaining its colonies lost in World War I, declaring: "A great people such as the German people must regain the place which is due to it, and which it used to have beneath the sun of Africa".[114]

With no significant opposition from Italy, Hitler proceeded with the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria in 1938. Germany later claimed the Sudetenland, a province of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by Germans. Mussolini felt he had little choice but to help Germany to avoid isolation. With the annexation of Austria by Germany in 1938, the Fascist regime began to be concerned about the majority ethnic German population in South Tyrol and whether they would want to join a Greater Germany. The Fascists were also concerned about whether Italy should follow National Socialist antisemitic policies in order to gain favor from those National Socialists who had mixed feelings about Italy as an ally. In 1938, Mussolini pressured fellow Fascist members to support the enacting of antisemitic policies, but this was not well taken as a number of Fascists were Jewish and antisemitism was not an active political concept in Italy. Nevertheless, Mussolini forced through antisemitic legislation even while his own son-in-law and prominent Fascist Count Galeazzo Ciano personally condemned such laws. In turn for enacting the extremely unpopular antisemitic laws, Mussolini and the Fascist government demanded a concession from Hitler and the National Socialists. In 1939, the Fascists demanded from Hitler that his government willingly accept the Italian government's plan to have all Germans in South Tyrol either leave Italy or be forced to accept Italianization. Hitler agreed and thus the threat to Italy from the South Tyrol Germans was neutralized.

Alliance with Germany

As war approached in 1939, the Fascist regime stepped up an aggressive press campaign against France claiming that Italian people were suffering in France.[115] This was important to the alliance as both regimes mutually had claims on France, Germany on German-populated Alsace-Lorraine and Italy on Italian-populated Corsica, Nizza and Savoia. In May 1939, a formal alliance was organized. The alliance was known as the Pact of Steel, which obliged Italy to fight alongside Germany if war broke out against Germany. Mussolini felt obliged to sign the pact in spite of his own concerns that Italy could not fight a war in the near future. This obligation grew from his promises to Italians that he would build an empire for them and from his personal desire to not allow Hitler to become the dominant leader in Europe.[116] Mussolini was displeased with Germany's invasion of Poland as he wanted to mediate the crisis, but decided to remain officially silent.[117]

World War II

Italy's military and logistical resources were stretched by successful pre-WWII military interventions in Spain,[118] Ethiopia, Libya, and Albania and were not ready for a long conflict. Nevertheless, Mussolini went to war to further the imperial ambitions of the Fascist regime, which aspired to restore the Roman Empire in the Mediterranean (the Mare Nostrum).

Italy joined the war as one of the Axis Powers in 1940, entering after it appeared France was likely to lose to Germany. The Italian invasion of France was brief as the French Third Republic surrendered shortly afterward. Italy readied to fight against the British Empire in Africa and the Middle East, known as the "parallel war", while expecting a similar collapse of British forces in the European theatre. The Italians bombed Mandatory Palestine, invaded Egypt and occupied British Somaliland with initial success. The Italian military machine showed weakness during the 1940 Greco-Italian War, a war of aggression Italy launched unprovoked, but where the Italian army found little progress. German intervention during the Battle of Greece would eventually bail the Italians out, and their grander ambitions were partially met by late 1942 with Italian influence extended throughout the Mediterranean. Most of Greece was occupied by Italy; Italians administered the French territories of Corsica and Tunisia following Vichy France's collapse and occupation by German forces; and a puppet regime was installed in Croatia following the German-Italian Invasion of Yugoslavia. Albania, Ljubljana, coastal Dalmatia (for the presence of Dalmatian Italians), and Montenegro had been directly annexed by the Italian state. Italo-German forces had also achieved victories against insurgents in Yugoslavia and had occupied parts of British-held Egypt on their push to El-Alamein after their victory at Gazala.

However, Italy's conquests were always heavily contested, both by various insurgencies (most prominently the Greek resistance and Yugoslav partisans) and Allied military forces, which waged the Battle of the Mediterranean throughout and beyond Italy's participation. German and Japanese actions in 1941 led to the entry of the Soviet Union and United States, respectively, into the war, thus ruining the Italian plan of forcing Britain to agree to a negotiated peace settlement.[119] Ultimately the Italian Empire collapsed after disastrous defeats in the Eastern European and North African campaigns. In July 1943, following the Allied invasion of Sicily, Mussolini was arrested by orders of King Victor Emmanuel III, and Badoglio became the new prime minister of Italy. Badoglio began to dismantle all Fascist organizations throughout Italy as well as the National Fascist Party. Italy's military outside of the Italian peninsula collapsed, its occupied and annexed territories falling under German control. Italy signed the armistice to the Allies on 3 September 1943. And on 29 September, Italy officially signed the instrument of surrender at Malta.

After Italy's surrender to the Allies. The Italian Civil War began. The northern half of the country was occupied by the Germans with the cooperation of Italian fascists and became the Italian Social Republic, a collaborationist puppet state still led by Benito Mussolini that recruited more than 500,000 soldiers for the Axis cause. The south was officially controlled by monarchist forces, which fought for the Allied cause as the Italian Co-Belligerent Army (at its height numbering more than 50,000 men), as well as around 350,000[120] Italian resistance movement partisans (mostly former Royal Italian Army soldiers) of disparate political ideologies that operated all over Italy. On 28 April 1945, Benito Mussolini was executed by Italian partisans, two days before Adolf Hitler's suicide.

Anti-fascism during Mussolini's rule

In Italy, Mussolini's Fascist regime used the term anti-fascist to describe its opponents. Mussolini's secret police was officially known as the Opera Vigilanza Repressione Antifascismo (usually known simply as the OVRA). During the 1920s in the Kingdom of Italy, anti-fascists, many of them members and supporters of the labor movement, fought against the violent Blackshirts and they also fought against the rise of the fascist leader Benito Mussolini. After the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) signed a pacification pact with Mussolini and his Fasces of Combat on 3 August 1921,[121] and trade unions adopted a legalist and pacified strategy, members of the workers' movement who disagreed with this strategy formed Arditi del Popolo.[122]

The Italian General Confederation of Labour (CGL) and the PSI refused to officially recognize the anti-fascist militia and it also maintained a non-violent, legalist strategy, while the Communist Party of Italy (PCd'I) ordered its members to leave the organization. The PCd'I organized some militant groups, but their actions were relatively minor.[123] The Italian anarchist Severino Di Giovanni, who exiled himself to Argentina following the 1922 March on Rome, organized several bombings against the Italian fascist community.[124] The Italian liberal anti-fascist Benedetto Croce wrote his Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals, which was published in 1925.[125] Other notable Italian liberal anti-fascists around that time were Piero Gobetti and Carlo Rosselli.[126]

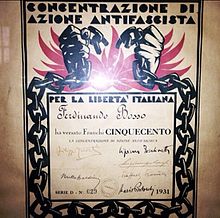

Concentrazione Antifascista Italiana (English: Italian Anti-Fascist Concentration), officially known as Concentrazione d'Azione Antifascista (Anti-Fascist Action Concentration), was an Italian coalition of Anti-Fascist groups which existed from 1927 to 1934. Founded in Nérac, France, by expatriate Italians, the CAI was an alliance of non-communist anti-fascist forces (republican, socialist, nationalist) trying to promote and to coordinate expatriate actions to fight fascism in Italy; they published a propaganda paper entitled La Libertà.[127][128][129]

Giustizia e Libertà (English: Justice and Freedom) was an Italian anti-fascist resistance movement, active from 1929 to 1945.[130] The movement was cofounded by Carlo Rosselli,[130] Ferruccio Parri, who later became Prime Minister of Italy, and Sandro Pertini, who became President of Italy, were among the movement's leaders.[131] The movement's members held various political beliefs but shared a belief in active, effective opposition to fascism, compared to the older Italian anti-fascist parties. Giustizia e Libertà also made the international community aware of the realities of fascism in Italy, thanks to the work of Gaetano Salvemini.

Many Italian anti-fascists participated in the Spanish Civil War with the hope of setting an example of armed resistance to Franco's dictatorship against Mussolini's regime; hence their motto: "Today in Spain, tomorrow in Italy".[132]

Between 1920 and 1943, several anti-fascist movements were active among the Slovenes and Croats in the territories annexed to Italy after World War I, known as the Julian March.[133][134] The most influential was the militant insurgent organization TIGR, which carried out numerous sabotages, as well as attacks on representatives of the Fascist Party and the military.[135][136] Most of the underground structure of the organization was discovered and dismantled by the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism (OVRA) in 1940 and 1941,[137] and after June 1941 most of its former activists joined the Slovene Partisans.

During World War II, many members of the Italian resistance left their homes and went to live in the mountains, fighting against Italian fascists and German Nazi soldiers during the Italian Civil War. Many cities in Italy, including Turin, Naples and Milan, were freed during anti-fascist uprisings.[138]

Historiography

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

Most of the historiographical controversy centers on sharply conflicting interpretations of Fascism and the Mussolini regime.[139] The 1920s writers on the left, following the lead of communist theorist Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937), stressed that Fascism was a form of capitalism. The Fascist regime controlled the writing and teaching of history through the central Giunta Centrale per gli Studi Storici and control of access to the archives and sponsored historians and scholars who were favorable toward it such as philosopher Giovanni Gentile and historians Gioacchino Volpe and Francesco Salata.[140] In October 1932, it sponsored a large Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution, featuring its favored modernist art and asserting its own claims to express the spirit of Roman glory.[141]

After the war, most historiography was intensely hostile to Mussolini, emphasizing the theme of Fascism and totalitarianism.[142] An exception was historian Renzo De Felice (1929–1996), whose Mussolini's Biography, four volumes and 6,000 pages long (1965–1997), remains the most exhaustive examination of public and private documents about Italian Fascism and serves as a basic resource for all scholars. De Felice argued that Mussolini was a revolutionary modernizer in domestic issues, but a pragmatist in foreign policy who continued the Realpolitik policies of liberal Italy (1861–1922).[143] In the 1990s, a cultural turn began with studies that examined the issue of popular reception and acceptance of Fascism using the perspectives of "aestheticization of politics" and "sacralisation of politics".[144] By the 21st century, the old "anti-Fascist" postwar consensus was under attack from a group of revisionist scholars who have presented a more favorable and nationalistic assessment of Mussolini's role, both at home and abroad. Controversy rages as there is no consensus among scholars using competing interpretations based on revisionist, anti-Fascist, intentionalist or culturalist models of history.[145]

See also

- Fascist and anti-Fascist violence in Italy (1919–1926)

- Italian Fascism

- Mussolini government

- European interwar dictatorships

- Fascism in Europe

Notes

References

- ^ Harrison, Mark (1998). The Economics of World War II: Six Great Powers in International Comparison. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-5216-2046-8. OL 7748977M.

- ^ Payne, Stanley G. (1995). A History of Fascism, 1914–1945. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 212. ISBN 0-2991-4870-X. OL 784569M.

- ^ Mussolini, Benito (1935). Fascism: Doctrine and Institutions. Rome: Ardita. p. 14.

- ^ Pauley, Bruce F. (2003). Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini: Totalitarianism in the Twentieth Century Italy. Wheeling: Harlan Davidson. p. 107.

- ^ Gentile, Emilio (2003). The Struggle For Modernity Nationalism Futurism and Fascism. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. p. 87.

- ^ Gentile, p. 81.

- ^ Gentile, p. 146.

- ^ Pauley, p. 108.

- ^ Caprotti, Federico (2005). "Information management and fascist identity: newsreels in fascist Italy". Media History. 11 (3): 177–191. doi:10.1080/13688800500323899.

- ^ Pauley, p. 109.

- ^ Gori, Gigliola (1999). "Model of masculinity: Mussolini, the 'new Italian' of the Fascist era". International Journal of the History of Sport. 16 (4): 27–61. doi:10.1080/09523369908714098. PMID 21812160.

- ^ Caldwell, Lesley. Madri d'ltalia: Film and Fascist Concern with Motherhood. in Bara'nski, Zygmunt G.; Yannopoulos, George N., eds. (1991). Women and Italy: Essays on Gender, Culture and History. pp. 43–63.

- ^ "Italy, 24 May 1929: Fascist single list". Direct Democracy (in German). 24 May 1929.

- ^ Smith, Italy, pp. 40–443.

- ^ Pollard, John F. (2014). The Vatican and Italian Fascism, 1929–32: A Study in Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 53. ISBN 978-0-5212-6870-7.

- ^ a b c Feinstein, Wiley (2003). The Civilization of the Holocaust in Italy: Poets, Artists, Saints, Anti-semites. London: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-8386-3988-7..

- ^ Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1961). Christianity In a Revolutionary Age: A History of Christianity in the 19th and 20th Century. The 20th Century In Europe. Vol. 4. pp. 32–35, 153, 156, 371.

- ^ Duffy, Eamon (2002). Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. p. 340. ISBN 0-3000-9165-6.

- ^ a b Kertzer, David I. (2014). The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe. New York: Random House. pp. 196–198. ISBN 978-0-8129-9346-2.

- ^ Pollard (2014), p. 49.

- ^ Pollard (2014), p. 61.

- ^ a b Giordano, Alberto; Holian, Anna (2018). "The Holocaust in Italy". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 3 April 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

In 1938, the Italian Fascist regime under Benito Mussolini enacted a series of racial laws that placed multiple restrictions on the country's Jewish population. At the time the laws were enacted, it is estimated that about 46,000 Jews lived in Italy, of whom about 9,000 were foreign born and thus subject to further restrictions such as residence requirements. ... Estimates suggest that between September 1943 and March 1945, about 10,000 Jews were deported. The vast majority of them perished, principally at Auschwitz.

- ^ a b Pollard 2014, pp. 109–111; Zanini, Paolo (2015). "Twenty years of persecution of Pentecostalism in Italy: 1935–1955". Journal of Modern Italian Studies. 20 (5). Taylor & Francis: 686–707. doi:10.1080/1354571X.2015.1096522. hdl:2434/365385. S2CID 146180634.

- ^ a b c "Risveglio Pentecostale" (in Italian). Assemblies of God in Italy. Archived from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Scholars at the Vatican". Commonweal, 4 December 1942, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Gilbert (2004), pp. 307–308.

- ^ Gilbert (1986), p. 466.

- ^ Gilbert (2004), pp. 308, 311.

- ^ Joshua D. Zimmerman (2005). Jews in Italy Under Fascist and Nazi Rule, 1922–1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-5218-4101-6.

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher (1975). Benito Mussolini. p. 99.

- ^ Zimmerman, p.160

- ^ Hibbert (1975), p. 98.

- ^ Baum, David (2011). Hebraic Aspects of the Renaissance: Sources and Encounters. Brill. ISBN 978-9-0042-1255-8. Retrieved 9 January 2016.; Neocleous, Mark (1997). Fascism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 35.

- ^ Herf, Jeffrey (2013). Anti-Semitism and Anti-Zionism in Historical Perspective: Convergence and Divergence. Routledge. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-4154-0069-5.

- ^ Alessandri, Giuseppe (2020). Il processo Mussolini (in Italian). Gruppo Albatros Il Filo. ISBN 978-8-8306-2337-8.

- ^ Sarti, p. 199.

- ^ Sarti, p. 200.

- ^ Lindemann, Albert S. (1997). Esau's Tears: Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews. Cambridge University Press. pp. 466–467.

- ^ a b Brustein, William I. (2003). Roots of Hate: Anti-Semitism in Europe Before the Holocaust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 327.

- ^ Neville, Peter. Mussolini. p. 117.

- ^ a b Segrè, Claudio G. (1999). Italo Balbo: A Fascist Life. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 346.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lindemann (1997), p. 466.

- ^ a b c Feinstein, Wiley (2003). The Civilization of the Holocaust in Italy: Poets, Artists, Saints, Anti-Semites. Rosemont Publish & Printing. p. 201.

- ^ a b Wiley Feinstein. The Civilization of the Holocaust in Italy: Poets, Artists, Saints, Anti-Semite's. Rosemont Publish & Printing Corp., 2003. p. 202. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Sarfatti, Michele; Tedeschi, Anne C. The Jews in Mussolini's Italy: From Equality to Persecution. p. 202.

- ^ Steinberg, Jonathan. All Or Nothing: The Axis and the Holocaust, 1941–1943. p. 220.

- ^ "Pax Romanizing". Time, 31 December 1934.

- ^ a b Feinstein, p. 304.

- ^ Sarti, p. 198.

- ^ "Italy". www.edwardvictor.com. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Hibbert (1975), p. 110.

- ^ Pauley, p. 117.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pauley, p. 117

- ^ Cannistraro, Philip V. (1982) Historical Dictionary of Fascist Italy, Westport, CN; London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-3132-1317-8, p. 474

- ^ a b Pauley, p. 113.

- ^ de Grazia, Victoria (1981). The Culture of Consent: Mass Organizations of Leisure in Fascist Italy Cambridge.

- ^ Kallis, Aristotle, ed. (2003). The Fascism Reader, London: Routledge, pp. 391–395.

- ^ Pauley, pp. 113–114

- ^ Hamish Macdonald (1999). Mussolini and Italian Fascism. Nelson Thornes. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-7487-3386-6.

- ^ a b Farrell, Nicholas (2004). Mussolini. London: Phoenix. p. 234.

- ^ Farrell (2004), pp. 234–235.

- ^ Farrell (2004), p. 235.

- ^ a b c Koon, Tracy H. (1985). Believe, Obey, Fight: Political Socialization of Youth in Fascist Italy, 1922–1943. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 112.

- ^ "Italy The rise of Mussolini". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2007.; "Benito's Birthday". Time. 6 August 1923. Archived from the original on 7 April 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2007.; Bosworth, R. J. B. (2002). Mussolini. New York: Arnold/Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-3407-3144-3.; "The Straight Dope: Did Mussolini use castor oil as an instrument of torture?". www.straightdope.com. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Fabio Truzzolillo, "The 'Ndrangheta: the current state of historical research", Modern Italy (August 2011) 16#3 pp. 363–383.

- ^ "Mafia Trial", Time, 24 October 1927.

- ^ "Feature Articles 302". AmericanMafia.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007.

- ^ Willson, Perry R., The Clockwork Factory: Women and Work in Fascist Italy (1994)

- ^ Willson, Perry R., Peasant Women and Politics in Fascist Italy: The Massaie Rurali (2002)

- ^ De Grazia, Victoria, How Fascism Ruled Women: Italy, 1922–1945 (1993)

- ^ Willson, Perry R., "Empire, Gender and the 'Home Front' in Fascist Italy", Women's History Review, October 2007, Vol. 16 Issue 4, pp. 487–500.

- ^ Helstosky, Carol, "Fascist food politics: Mussolini's policy of alimentary sovereignty, Journal of Modern Italian Studies March 2004, Vol. 9 Issue 1, pp. 1–26.

- ^ Mussolini, Benito. 1935. Fascism: Doctrine and Institutions. Rome: Ardita Publishers. pp. 135–136.

- ^ Sarti, 1968.

- ^ Pauley, p. 85.

- ^ a b Pauley, p. 86

- ^ a b Pauley, p. 87

- ^ a b c Pauley, p. 88

- ^ Cannistraro, Philip V. 1982. Historical Dictionary of Fascist Italy. Westport, CT / London: Greenwood Press. p. 5

- ^ Cannistraro, p. 5.

- ^ "Rex". The Great Ocean Liners. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Caliaro, Luigino (23 October 2014). "Today in Aviation History – Macchi Castoldi M.C. 72, The World's Fastest Piston-Powered Seaplane". Warbirds News. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ LaMorte, Chris (2 October 2017). "Century of Progress Homes Tour at Indiana Dunes takes visitors back to the future". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ Stephen J. Lee (2008). European Dictatorships, 1918–1945. Routledge. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-0-4154-5484-1.

- ^ Lawson, Edward; Bertucci, Mary Lou; Dargel, Jan (1996). Encyclopedia of Human Rights. Taylor & Francis. p. 971. ISBN 978-1-5603-2362-4.

- ^ a b "IBS No. 10 – Libya (LY) & Sudan (SU) 1961" (PDF). fsu.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Gilbert, Martin (introduction). 1989. The Illustrated London News: Marching to War, 1933–1939. Toronto, Canada: Doubleday Canada Ltd., p. 137.

- ^ Davide Rodogno (3 August 2006). Fascism's European Empire: Italian Occupation During the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. p. 65.

- ^ Claudio G. Segrè. Italo Balbo: A Fascist Life. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-5200-7199-5

- ^ Sarti, Roland. 1974. The Ax Within: Italian Fascism in Action. New York: New Viewpoints, p. 189.

- ^ Sarti, p. 191.

- ^ a b c d e Sarti, p. 190.

- ^ "[image]". www.germaniainternational.com.

- ^ "[image]". www.germaniainternational.com.

- ^ Joshua D. Zimmerman, Jews in Italy Under Fascist and Nazi Rule, 1922–1945, pp. 119–120

- ^ Michael A. Livingston, The Fascists and the Jews of Italy: Mussolini's Race Laws, 1938–1943, p. 17

- ^ Livingston, p. 67

- ^ Sarti, p. 194.

- ^ Sarti, p. 196.

- ^ a b c d Smith. 1983. p. 172.

- ^ Stoker, Donald J.; Grant, Jonathan (2003). Girding for Battle: The Arms Trade in a Global Perspective, 1815–1940. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-275-97339-1. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Glenny, Misha. Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1804–1999. New York: Penguin Books, 2001. p. 431

- ^ Smith, 1997. pp. 398–399

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2001) [1982]. The Spanish Civil War. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-0-14-100148-7.

- ^ Neulen, Hans Werner (2000). In the skies of Europe – Air Forces allied to the Luftwaffe 1939–1945. Ramsbury, Marlborough, England: The Crowood Press. p. 25. ISBN 1861267991.

- ^ a b Beevor, Antony (2001) [1982]. The Spanish Civil War. New York: Penguin Books. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-14-100148-7.

- ^ Balfour, Sebastian; Preston, Paul (2009). Spain and the great powers in the twentieth century. London; New York: Routledge. p. 172. ISBN 978-0415180788.

- ^ a b Rodrigo, Javier (2019). "A fascist warfare? Italian fascism and war experience in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39)". War in History. 26 (1): 86–104. doi:10.1177/0968344517696526. JSTOR 26986937. S2CID 159711547.

- ^ Thomas (2001), pp. 938–939.

- ^ Mack Smith, Denis (1983). Mussolini: A Biography. New York: Vintage Books. p. 181.

- ^ Smith, 1983. p. 181.

- ^ Smith, 1983. p. 172.