Women's sports

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

|

Women's sports includes amateur as well as women's professional sports, in virtually all varieties of sports. Female participation in sports rose dramatically in the twentieth century, especially in the last quarter, reflecting changes in modern societies that emphasized gender parity. Although the level of participation and performance still varies greatly by country and by sport, women's sports have broad acceptance throughout the world in the 2010s. In a few instances, such as figure skating, women athletes rival or exceed their male counterparts in popularity. An important aspect about women's sports is that women usually do compete on equal terms against men.[1]

History

Ancient civilizations

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2011) |

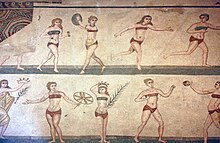

Before each ancient Olympic Games there was a separate women's athletic event, the Heraean Games, dedicated to the goddess Hera and held at the same stadium at Olympia. Myth held that the Heraea was founded by Hippodameia the wife of the king who founded the Olympics.[2]

Although married women were excluded from the Olympics even as spectators, Cynisca won an Olympic game as owner of a chariot (champions of chariot races were owners not riders), as did Euryleonis, Belistiche, Zeuxo, Encrateia and Hermione, Timareta, Theodota and Cassia.

After the classical period, there was some participation by women in men's athletic festivals.[2]

Early modern

During the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties, women played in professional Cuju teams [2][3]

The first Olympic games in the modern era, which were in 1896 were not open to women, but since then the number of women who have participated in the Olympic games have increased dramatically.[3]

19th and early 20th centuries

The educational committees of the French Revolution (1789) included intellectual, moral, and physical education for girls and boys alike. With the victory of Napoleon less than twenty years later, physical education was reduced to military preparedness for boys and men. In Germany, the physical education of GutsMuths (1793) included girl's education. This included the measurement of performances of girls. This led to women's sport being more actively pursued in Germany than in most other countries.[4] When the Fédération Sportive Féminine Internationale was formed as an all women's international organization it had a German male vice-president, and German international success in elite sports.

Women's sports in the late 1800s focused on correct posture, facial and bodily beauty, muscles, and health.[citation needed] In 1916 the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) held its first national championship for women.[citation needed]

Few women competed in sports in Europe and North America until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as social changes favored increased female participation in society as equals with men. Although women were technically permitted to participate in many sports, relatively few did. There was often disapproval of those who did.

"Bicycling has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world." Susan B. Anthony said "I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride on a wheel. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance."

The modern Olympics had female competitors from 1900 onward, though women at first participated in considerably fewer events than men. Women first made their appearance in the Olympic Games in Paris in 1900. That year, 22 women competed in tennis, sailing, croquet, equestrian, and golf.[5] As of the IOC-Congress in Paris 1914 a woman's medal had formally the same weight as a man's in the official medal table. This left the decisions about women's participation to the individual international sports federations.[6] Concern over the physical strength and stamina of women led to the discouragement of female participation in more physically intensive sports, and in some cases led to less physically demanding female versions of male sports. Thus netball was developed out of basketball and softball out of baseball.

In response to the lack of support for women's international sport the Fédération Sportive Féminine Internationale was founded in France. This organization initiated the Women's World Games, which attracted participation of nearly 20 countries and was held four times between 1922 and 1934.[7] The International Olympic Committee began to incorporate greater participation of women at the Olympics in response. The number of Olympic women athletes increased over five-fold in the period, going from 65 at the 1920 Summer Olympics to 331 at the 1936 Summer Olympics.[8][9]

Most early women's professional sports leagues foundered. This is often attributed to a lack of spectator support. Amateur competitions became the primary venue for women's sports. Throughout the mid-twentieth century, Communist countries dominated many Olympic sports, including women's sports, due to state-sponsored athletic programs that were technically regarded as amateur. The legacy of these programs endured, as former Communist countries continue to produce many of the top female athletes. Germany and Scandinavia also developed strong women's athletic programs in this period.

- Women's sports in history

-

Young women wearing swimming competition medals, around 1920.

-

Fraulein Kussinn and Mrs. Edwards boxing, 1912.

-

Fencer Sibyl Marston holding a foil.

-

Edith Cummings was the first woman athlete to appear on the cover of Time magazine, a major step in women's athletic history.

United States

In 1972 the United States government implemented Title IX, a law stating that any federally funded program cannot discriminate anyone based on their sex.[10] Participation by women in sports increased dramatically after its introduction, amid fears that this new law would jeopardize men's sports programs.[10][11] In 1990, Bernadette Mattox became the first female Division I coach of a men's basketball team at the University of Kentucky. A year later, goaltender Jenny Hanley of Hamline University became the first women to play on a men's college ice hockey team.[12] By 1994, the number of females playing sports in high school had increased threefold since Title IX was implemented, and ground was broken for the Women's Basketball Hall of Fame, the first such hall of fame devoted to exclusively women athletes. In 1996 the number of female high school athletes reached 2.4 million, including 819 football players, 1164 wrestlers, and 1471 ice hockey players.[12]

Canada

Sports are high priority in Canadian culture, but women were long relegated to second-class status. There were regional differences as well, with the eastern provinces emphasizing a more feminine "girls rule" game of basketball, while the Western provinces preferred identical rules. Girls’ and women’s sport has traditionally been slowed down by a series of factors: girls and women historically have low levels of interest and participation; there were very few women in leadership positions in academic administration, student affairs or athletics; there were few women coaches; the media strongly emphasized men's sports as a demonstration of masculinity, suggesting that women seriously interested in sports were crossing gender lines; the male sports establishment was actively hostile. Staunch feminists dismissed sports as unworthy of their support. Women's progress was uphill; they first had to counter the widespread notion that women's bodies were so restricted and delicate that vigorous physical activity was dangerous. These notions where first challenged by the "new woman" around 1900. These women started with bicycling; they rode into new gender spaces in education, work, and suffrage. The 1920s marked a breakthrough for women, including working-class young women in addition to the pioneering middle class sportswomen.[13]

21st century

Heather Watson broke one of the last taboos in women's sport when she openly admitted after a poor performance in a tennis match that the reason behind it was the fact that she was menstruating.[14]

United States: Title IX

Implementation and Regulation

In 1972 women's sports in the United States got a boost when the Congress passed the Title IX legislation. The United States Congress passed this law as a part of the additional Amendment Act to the 1964 Civil Rights Act.[15] Title IX states that: "no person shall on the basis of sex, be excluded from participating in, be denied benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational programs or activities receiving federal financial assistance..."[16] in other words, Title IX prohibits gender discrimination in schools that receive federal funds through grants, scholarships, or other support for students. The law states that federal funds can be withdrawn from a school engaging in intentional gender discrimination in the provision of curriculum, counseling, academic support, or general educational opportunities; this includes interscholastic or varsity sports.[17] This law from the Education Act requires that both male and female athletes have equal facilities, equal benefits. The equal benefits are the necessities such as equal equipment, uniforms, supplies, training, practice, quality in coaches and opponents, awards, and cheerleaders and bands at the game.[18] In practice, the difficulty with Title IX is making sure schools are compliant with the law. In 1979, there was a policy interpretation that offered three ways in which schools could be compliant with Title IX; it became known as the "three-part test".

- Providing athletic participation opportunities that are substantially proportionate to the student enrollment. This prong of the test is satisfied when participation opportunities for men and women are "substantially proportionate" to their respective undergraduate enrollment.

- Demonstrating a continual expansion of athletic opportunities for the underrepresented sex. This prong of the test is satisfied when an institution has a history and continuing practice of program expansion that is responsive to the developing interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex (typically female).

- Accommodating the interest and ability of underrepresented sex. This prong of the test is satisfied when an institution is meeting the interests and abilities of its female students even where there are disproportionately fewer females than males participating in sports.

Although schools only have to be compliant with one of the three prongs, many schools have not managed to achieve equity. Many schools attempt to achieve compliance through the first prong, however, in order to achieve that compliance schools cut men's programs which is not the way the OCR wanted compliance achieved.[19] Equity is not the only way to be compliant with Title IX. To be considered compliant with Title IX, athletic departments simply need to show that they are making efforts to achieve parity in participation, treatment, and athletic financial assistance.[20]

Effect on women's sports

The main objective of Title IX is to avoid the discrimination of anyone due to their sex in a federally funded program. It was also used to provide protection to those who are being descrminated due to their gender.[21] However, Title IX is most commonly associated with its impact on athletics and more specifically the impact it has had on women's participation in athletics at every age. Today there are more females participating in athletics than ever before. As of the 2007-2008 school year, females made up 41% of the participants in college athletics.[22] To see the growth of women's sports just look at the difference in participation before the passing of Title IX and today. In 1971-1972 there were 294,015 females participating in high school athletics and in 2007-2008 there were over three million females participating, meaning there has been a 940% increase in female participation in high school athletics.[22]

In 1971-1972 there were 29,972 females participating in college athletics and in 2007-2008 there were 166,728 females participating, that is a 456% increase in female participation in college athletics.[22] In 1971, less than 300,000 females played in high school sports. After the law was passed many females started to play. By 1990, only eighteen years later, 1.9 million female high school students were playing sports.[15] More females are getting involved and finding a love and passion for sports that were once seen as something for men. Increased participation in sports has had direct effects on other areas of women's lives. These effects can be seen in women's education and employment later on in life; a recent study found that the changes set in motion by Title IX explained about 20 percent of the increase in women's education and about 40 percent of the rise in employment for 25-to-34-year-old women.[23] This is not to say that all women who are successful later on in life played sports, but it is saying that women who did participate in athletics received benefits in their education and employment later on in life.[23]

"In 1971, fewer than 295,000 girls participated in high school varsity athletics, accounting for just 7 percent of all varsity athletes; in 2001, that number leaped to 2.8 million, or 41.5 percent of all varsity athletes, according to the National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education. In 1966, 16,000 females competed in intercollegiate athletics. By 2001, that number jumped to more than 150,000, accounting for 43 percent of all college athletes. In addition, a 2008 study of intercollegiate athletics showed that women’s collegiate sports had grown to 9,101 teams, or 8.65 per school. The five most frequently offered college sports for women are, in order: (1) basketball, 98.8% of schools have a team, (2) volleyball, 95.7%, (3) soccer, 92.0%, (4) cross country, 90.8%, and (5) softball, 89.2%. Since 1972, women have also competed in the traditional male sports of wrestling, weightlifting, rugby, and boxing. Parents have begun to watch their daughters on the playing fields, courts, and on television. A recent article in the New York Times found that there are lasting benefits for women from Title IX: participation in sports increased education as well as employment opportunities for girls. Furthermore, the athletic participation by girls and women spurred by Title IX was associated with lower obesity rates. No other public health program can claim similar success." [24]

"However, as part of the backlash against the women’s movement, opposition quickly organized against Title IX. Worried about how it would affect men’s athletics, legislators and collegiate sports officials became concerned and looked for ways to limit its influence. One argument was that revenue-producing sports such as college football should be exempted from Title IX compliance. Another was that in order for schools and colleges to comply, they would have to cut men’s sports such as wrestling. Others argued that federal legislation was not the way to achieve equality or even parity. Finally, conservative opponents of women’s rights believed that feminists used Title IX as an all-purpose vehicle to advance their agenda in the schools. Since 1975, there have been twenty court challenges to Title IX in an attempt to whittle down greater gender equity in all fields of education—mirroring the ups and downs of the women’s movement at large. According to the National Federation of State High School Associations, female students received 1.3 million fewer opportunities to participate in high school athletics than their male peers in the 2006–2007 school years. Yet as a result of Title IX, women have benefited from involvement in amateur and professional sports and, in turn, sports are more exciting with their participation." [24]

The battle for equality

The battle for equality between men's and women's sports continues in the 2000s. Women make up 54% of enrollment at 832 schools that responded to an NCAA gender equity study in 2000, however, females at these institutions only account for 41% of the athletes. Before Title IX 90% of women's college athletic programs were run by women, but by 1992 the number dropped to 42% since Title IX requires that there are equal opportunities for both genders.[15] This violates Title IX's premise that the ratio of female athletes to male athletes should be roughly equivalent to the overall proportion of female and male students.[25] Many of the issues today often revolve around the amount of money going into men and women's sports. According to 2000-2001 figures, men's college programs still have many advantages over women's in the average number of scholarships (60.5%), operating expenses (64.5%), recruiting expenses (68.2%) and head coaching salaries (59.5%).[25] Other forms of inequality are in the coaching positions. Before Title IX, women coached 90% of women's teams, in 1978 that percentage dropped to 58, and in 2004 it dropped even more to 44 percent.[26] In 1972, women administered 90 percent of women's athletic programs, in 2004 this fell to 19 percent and also in 2004 18 percent of all women's programs had no women administrators.[26] In 2004 there were 3356 administrative jobs in NCAA women's athletic programs and of those jobs women held 35 percent of them.[26]

The 2012 London Olympics were the first games of their kind in which women competed in every sport.[27]

Media coverage

Researchers[who?] have shown that media coverage for women’s sports has been significantly less than the coverage for men’s sports. Millions of young women from all over the world play sports every day. However, the number of women playing sports does not correspond to the amount of media coverage that they get. In 1989, a study was conducted that recorded and compared the amount of media coverage of men and women’s sports on popular sports commentary shows. Michael Messner and his team analyzed three different two-week periods by recording the amount of time that the stories were on air and the content of the stories. After recording sports news and highlights, they wrote a quantitative description of what they saw and a qualitative of the amount of time that story received.[citation needed]

During that first year that the research was conducted in 1989, it was recorded that 5% of the sports segments were based on women’s sports, compared to the 92% that were based on men’s sports and the 3% that was a combination of both. In 1999, women’s sports coverage reached an all-time high when it was recorded at 8.7%. It maintained its higher percentages until it reached an all-time low in 2009, decreasing to 1.6%. The researchers also measured the amount of time that women’s sports were reported in the news ticker, the strip that displays information at the bottom of most news broadcasts. When recorded in 2009, 5% of ticker coverage was based on women’s sports, compared to the 95% that was based on men’s sports. These percentages were recorded in order to compare the amount of media coverage for each gender.

When researching the actual amount of time that women’s sports stories were mentioned, they focused specifically on differences between the National Basketball Association (NBA) and the Women’s National Basketball Association. They recorded two different time periods: when they were in season and when they were off-season. The WNBA had 8 stories, totaling 5:31 minutes, during their season, which was less than the NBA, which had a total of 72 stories, totaling approximately 65:51 minutes. During the off-season, the WNBA did not receive any stories or time on the ticker, while the NBA received a total of 81, which were approximately 50:15 minutes. When compared, the WNBA had a total of 8 stories and 5:31 minutes while the NBA had 153 stories and 1:56:06 hours. The actual games had several differences in the way the games were presented. The findings were that WNBA games had lower sound quality, more editing mistakes, fewer views of the shot clock and fewer camera angles. There was less verbal commentary and visual statistics about the players throughout the games as well.[28] The quality of the stories has also significantly changed. In past studies, women were sexualized, portrayed as violent, or portrayed as girlfriends, wives and mothers. Female athletes were often included in gag stories that involved sexual dialogue or emphasized their bodies. In Australia, the wives of the men’s cricket team members were given more media coverage than the players on the women’s cricket team, who also had won more games than the men’s rugby team.[29] In 2009, SportsCenter broadcast segments called “Her Story”, which was a commentary that highlighted women’s athletic careers.[30]

In newspapers articles, coverage on men’s sports once again had a greater number of articles than women’s sports in a ratio of 23–1. In 1990, a study was conducted that recorded and compared the amount of media coverage of men and women’s sports on popular newspapers. They analyzed four different sports magazines for three months and recorded the amount of women’s sports stories that were featured and the content of the stories. Women’s sports made up 3.5%, compared to the 81% of men’s coverage. The lengths of these articles were 25–27% shorter than the length of men’s articles.[31] There was an international frenzy in 2012 when the first woman that represented Saudi Arabia in the 2012 Olympics competed in track. That was the most women’s sports coverage that there had been in several years.[citation needed] Exactly 12 months later, the newspapers returned to featuring only 4% of articles on women’s sports.[32]

Dr. Amy Godoy-Pressland conducted a study that investigated the relationship between sports reporting and gender in Great Britain. She studied Great Britain’s newspapers from January 2008 to December 2009 and documented how media coverage of men’s sports and women’s sports was fairly equal during the Olympics and then altered after the Olympics were over. “Sportswomen are disproportionately under-represented and the sheer quantity and quality of news items on sportsmen demonstrates how male athletes are represented as dominant and superior to females.” She also documented how women’s bodies were sexualized in photographs and written coverage, noting that the women featured were either nude, semi-nude, or wearing revealing clothing. “The sexualisation of sportswomen in Sunday reporting is commonplace and aimed at the mostly male readership. It promotes the idea of female aesthetics over achievements, while the coverage of women not directly involved in sport misrepresents the place of women in sport and inferiorizes real sportswomen's achievements.” [33] The media has the ability to create or prevent interest in women’s sports. Excluding women’s sports from the media makes it much less likely for young girls to have role models that are women athletes.[34] According to Tucker Center for Research on Girls & Women in Sport at the University of Minnesota 40% of all athletes in the United States are women but women’s sports only receive about 4% of sports media coverage.[35] This amount of coverage has decreased in the last 20 years although there has been a major increase in women athletes.

The media coverage received by women athletes has increasingly become sexualized.[citation needed] This representative data is showcasing a main part of the minimal interaction the media has with women athletes. Scholarly studies (Kane, M. J., LaVoi, N. M., Fink, J. S. (2013) show that when women athletes were given the option to pick a photo of a picture that would increase respect for their sport, they picked an on-the-court competency picture. However, when women athletes were told to pick a picture that would increase interest in their sport, 47% picked a picture that sexualized the women athlete.[36] The UK is more representative than the United States with the BBC giving women’s sports about 20% of their sports coverage (BBC spokesperson). Many women athletes in the UK do not see this as adequate coverage for the 36% of women who participate in sports.[37]

1960s-2010s

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2012) |

Girls' and boys' participation rates in sports varies by country and region. In the United States today, nearly all schools require student participation in sports, guaranteeing that all girls were exposed to athletics at an early age, which was generally not the case in Western Europe and Latin America.[citation needed] In intramural sports, the genders were often mixed, though for competitive sports the genders remained segregated. Title IX legislation required colleges and universities to provide equal athletic opportunities for women. This large pool of female athletes enabled the U.S. to consistently rank among the top nations in women's Olympic sports, and female Olympians from skater Peggy Fleming (1968) to Mary Lou Retton (1986) became household names.[citation needed]

Tennis was the most-popular professional female sport from the 1970s onward,[citation needed] and it provided the occasion for a symbolic "battle of the sexes" between Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs, enhancing the profile of female athletics.[citation needed] The success of women's tennis, however, did little to help the fortunes of women's professional team sports.[citation needed]

Women's professional team sports achieved popularity for the first time in the 1990s, particularly in basketball and football (soccer).[citation needed] This popularity has been asymmetric, being strongest in the U.S., certain European countries and former Communist states.[citation needed] Thus, women's soccer was originally dominated by the U.S., China, and Norway, who have historically fielded weak men's national teams. However, [when?] several nations with strong and even dominant men's national teams, such as Germany, Sweden, and Brazil, have established themselves as women's powers.[citation needed] Despite this increase in popularity, women's professional sports leagues continue to struggle financially. The WNBA is operated at a loss by the NBA,[citation needed] perhaps in the hope of creating a market that will eventually be profitable. A similar approach is used to promote women's boxing, as women fighters are often undercards on prominent male boxing events, in the hopes of attracting an audience.[citation needed]

The National Women's Hockey League is an American women's professional ice hockey league, established in 2015.

Today, women compete professionally and as amateurs in virtually every major sport, though the level of participation typically decreases when it comes to the more violent contact sports; few schools have women's programs in American football, boxing or wrestling.[citation needed] However, these typical non-participation habits may slowly be evolving as more women take real interest in the games, for example Katie Hnida became the first woman ever to score points in a Division I NCAA American football game when she kicked two extra-points for the University of New Mexico in 2003.[citation needed]

Modern sports have seen the development of a higher profile for female athletes in other historically male sports, such as golf, marathons or ice hockey.[citation needed]

As of 2013, the only sports that men but not women play professionally in the United States are football, baseball, and Ultimate Frisbee.

Recently there has been much more crossover as to which sports males and females participate in, although there are still some differences. For example, at the 1992 Winter Olympics, both genders were allowed to participate in the sport of figure skating, previously a female-only sporting event. However, the programs for the event required men to perform three triple jumps, and women only one.

- Women athletes today

-

A female athlete from the University of California, San Diego playing soccer.

-

Olympic Games track gold medalist Meseret Defar of Ethiopia.

-

Master Hao Zhihua, the most accomplished female Wushu athlete in China's history.

-

Dutch cyclist Ellen van Dijk, at the 2012 Summer Olympics.

-

Fernanda Brito of Chile playing women's doubles tennis at Wimbledon in 2010.

-

A collage of Italian international sportswomen

Further reading

- Dong Jinxia: Women, Sport and Society in Modern China: Holding Up More Than Half the Sky, Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0-7146-8214-4

- Allen Guttmann: Women's Sports: A History, Columbia University Press 1992, ISBN 0-231-06957-X

- Helen Jefferson Lenskyj: Out of Bounds: Women, Sport and Sexuality. Women's Press, 1986.

- Helen Jefferson Lenskyj: Out on the Field: Gender, Sport and Sexualities. Women's Press, 2003.

- The Nation: Sports Don't Need Sex To Sell - NPR, Mary Jo Kane - August 2, 2011

- Else Trangbaek & Arnd Krüger (eds.): Gender and Sport from European Perspectives. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen 1999

See also

- History of Women in Sports Timeline

- Timeline of women's sports

- List of sportswomen

- Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act (Title IX)

- Women's Sports Foundation

- Major women's sport leagues in North America

- WTSN (TV channel)

- Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (defunct since 1982)

- Misogyny in sports

References

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b Scanlon, Thomas F. "Games for Girls". "Ancient Olympics Guide". Retrieved February 18, 2006.

- ^ "Women and Sport Commission". Retrieved January 14, 2014.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ Arnd Krüger (2003): Germany, in: James Riordan & Arnd Krüger (eds.): European Cultures in Sport. Examining the Nations and Regions. Bristol: Intellect 2003, pp. 57 – 88.

- ^ "Equality for Women in the Olympics." Feminist Majority Foundation. Web. November 2014. http://www.feminist.org/sports/olympics.asp

- ^ Arnd Krüger: Forgotton Decisions. The IOC on the Eve of World War I, in: Olympika 6 (1997), 85 – 98. (http://www.la84foundation.org/SportsLibrary/Olympika/Olympika_1997/olympika0601g.pdf)

- ^ Leigh, Mary H.; Bonin, Thérèse M. (1977). "The Pioneering Role Of Madame Alice Milliat and the FSFI in Establishing International Trade and Field Competition for Women" (PDF). Journal of Sport History. 4 (1). North American Society for Sport History: 72–83. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ Antwerp 1920. IOC. Retrieved on 2014-01-11.

- ^ Berlin 1936. IOC. Retrieved on 2014-01-11.

- ^ a b "Empowering Women in Sports".

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ Greenberg, Judith E. (1997). Getting into the Game: Women and Sports. New York: Franklin Watts.

- ^ a b "Part 6- 1990-1997".

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ M. Ann Hall, The Girl and the Game: A History of Women's Sport in Canada (Broadview Press, 2002)

- ^ http://www.theguardian.com/sport/shortcuts/2015/jan/21/menstruation-last-great-sporting-taboo

- ^ a b c Steiner, Andy (1995). A Sporting Chance: Sports and Genders.

- ^ Greenburg, Judith. E (1997). Getting into the Game: Women and Sports. New York: Franklin Watts.

- ^ Coakley, Jay (2007). Sports in Society. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 238.

- ^ Greenberg, Judith E. "Getting into the Game Women and Sports". Franklin Watts.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Irons, Alicia (Spring 2006). "The Economic Inefficiency of Title IX" (PDF). Major Themes in Economics. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ "Title IX Information". Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/cor/coord/titleix.php. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c "Title IX Athletic Statistics". Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Parker-Pope, Tara (February 16, 2010). "As Girls Become Women, Sports Pay Dividends". New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ a b http://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/seventies/essays/impact-title-ix

- ^ a b Garber, Greg. "Landmark law faces new challenges even now". Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c Coakley, Jay (2007). Sports in Society. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 255.

- ^ http://www.channel4.com/news/london-2012-is-this-the-womens-olympics

- ^ "Gender Stereotyping in Televised Sports." LA 48 Foundation. June 2010. Web. November 2014. http://www.la84.org/gender-stereotyping-in-televised-sports/

- ^ Holmes, Tracy. "After Homophobia Let's Tackle Prejudice Against Women's Sports." ABC. April 2014. Web. November 2014. http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/lifematters/after-homophobia-lets-tackle-prejudice-against-womens-sport/5381930

- ^ "Gender in Televised Sports News and Highlights Shows, 1989-2009." Center for Feminist Research, University of California. June 2010. Web. November 2014

- ^ "Coverage of Women's Sports in Four Daily Newspapers." LA84 Foundation. June 2010. Web. November 2014. http://www.la84.org/coverage-of-womens-sports-in-four-daily-newspapers/

- ^ Davies, Amanda. "Why has coverage of women's sport stopped post Olympics?" CNN. August 2013. Web. November 2014. http://edition.cnn.com/2013/08/07/sport/olympics-women-equality-attar/

- ^ “Women underrepresented, sexualized in weekend sports reporting” Science Daily. September 2013. Web. December 2014. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/09/130918090756.htm

- ^ Donna A. Lopiano, Ph.D., (2008). Media Coverage of Women’s Sports is Important, (2), Sports Management Resources, http://www.sportsmanagementresources.com/library/media-coverage-womens-sports

- ^ University of Minnesota (Producer) and PBS, (2014). Media Coverage & Female Athletes, http://video.tpt.org/video/2365132906/

- ^ Kane, M. J., LaVoi, N. M., Fink, J. S. (2013). Exploring elite female athletes' interpretations of sport media images: A window into the construction of social identity and "selling sex" in women's sports. Communication & Sport, 1(3), 269-298. doi: 10.1177/2167479512473585

- ^ Gareth Lewis, (2014). Nicole Cooke calls for women's sport to have equal coverage on BBC, (p. 2), BBC News Wales, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-26653208