Hindi cinema: Difference between revisions

Dr. Blofeld (talk | contribs) remove vios |

→Golden Age: mentioned Kamal Amrohi |

||

| (13 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

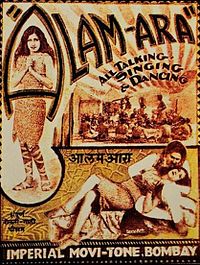

[[Image:Alam Ara poster, 1931.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Film poster for first Indian sound film, [[Ardeshir Irani]]'s ''[[Alam Ara]]'' (1931)]] |

[[Image:Alam Ara poster, 1931.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Film poster for first Indian sound film, [[Ardeshir Irani]]'s ''[[Alam Ara]]'' (1931)]] |

||

[[Image:Awaara.jpg|thumb|200px|[[Nargis]] and [[Raj Kapoor]] in ''[[Awaara]]'' (1951), also directed and produced by Kapoor. It was nominated for the [[Palme d'Or|Grand Prize]] of the [[1951 Cannes Film Festival]].]] |

[[Image:Awaara.jpg|thumb|200px|[[Nargis]] and [[Raj Kapoor]] in ''[[Awaara]]'' (1951), also directed and produced by Kapoor. It was nominated for the [[Palme d'Or|Grand Prize]] of the [[1951 Cannes Film Festival]].]] |

||

[[Image:GuruDutt.jpg|thumb|200px|[[Guru Dutt]] in ''[[Pyaasa]]'' (1957), for which he was the director, producer and leading actor. It is one of [[Time magazine's "All-TIME" 100 best movies]].]] |

|||

''[[Raja Harishchandra]]'' (1913), by [[Dadasaheb Phalke]], was the first silent feature film made in India. By the 1930s, the industry was producing over 200 films per annum. The first Indian sound film, [[Ardeshir Irani]]'s ''[[Alam Ara]]'' (1931), was a major commercial success. There was clearly a huge market for talkies and musicals; Bollywood and all the regional film industries quickly switched to sound filming. |

''[[Raja Harishchandra]]'' (1913), by [[Dadasaheb Phalke]], was the first silent feature film made in India. By the 1930s, the industry was producing over 200 films per annum. The first Indian sound film, [[Ardeshir Irani]]'s ''[[Alam Ara]]'' (1931), was a major commercial success. There was clearly a huge market for talkies and musicals; Bollywood and all the regional film industries quickly switched to sound filming. |

||

| Line 16: | Line 17: | ||

===Golden Age=== |

===Golden Age=== |

||

Following [[Indian independence movement|India's independence]] |

Following [[Indian independence movement|India's independence]], the period from the late 1940s to the 1960s are regarded by film historians as the "Golden Age" of Hindi cinema.<ref>{{citation|title=Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change|last=K. Moti Gokulsing|first=K. Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake|publisher=Trentham Books|year=2004|isbn=1858563291|page=17}}</ref><ref>{{citation|title=Gender, Nation, and Globalization in Monsoon Wedding and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge|first= |

||

Jenny|last=Sharpe|journal=Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism|volume=6|issue=1|year=2005|pages=58-81 [60 & 75]}}</ref><ref>{{citation|first=Sharmistha|last=Gooptu|title=Reviewed work(s): ''The Cinemas of India'' (1896-2000) by Yves Thoraval|journal=[[Economic and Political Weekly]]|volume=37|issue=29|year=2002|date=July 2002|pages=3023-4}}</ref> Some of the most critically-acclaimed Hindi films of all time were produced during this period. Examples include the [[Guru Dutt]] films ''[[Pyaasa]]'' (1957) and ''[[Kaagaz Ke Phool]]'' (1959) and the [[Raj Kapoor]] films ''[[Awaara]]'' (1951) and ''[[Shree 420]]'' (1955). These films expressed social themes mainly dealing with working-class urban life in India; ''Awaara'' presented the city as both a nightmare and a dream, while ''Pyaasa'' critiqued the unreality of city life.<ref name=Gokulsing-18>{{citation|title=Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change|last=K. Moti Gokulsing|first=K. Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake|publisher=Trentham Books|year=2004|isbn=1858563291|page=18}}</ref> Some of the most famous [[epic film]]s of Hindi cinema were also produced at the time, including [[Mehboob Khan]]'s ''[[Mother India]]'' (1957), which was nominated for the [[Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film]],<ref>{{imdb title|id=0050188|title=Mother India}}</ref> and [[K. Asif]]'s ''[[Mughal-e-Azam]]'' (1960).<ref>{{cite web|title=Film Festival - Bombay Melody|publisher=[[University of California, Los Angeles]]|date=March 17, 2004|url=http://www.international.ucla.edu/calendar/showevent.asp?eventid=1618|accessdate=2009-05-20}}</ref> ''[[Madhumati]]'' (1958), directed by [[Bimal Roy]] and written by [[Ritwik Ghatak]], popularized the theme of [[reincarnation]] in [[Reincarnation in popular western culture|Western popular culture]].<ref name=Doniger/> Other acclaimed mainstream Hindi filmmakers at the time included [[V. Shantaram]], [[Kamal Amrohi]] and [[Vijay Bhatt]]. Successful actors at the time included [[Dev Anand]], [[Dilip Kumar]], Raj Kapoor and Guru Dutt, while successful actresses included [[Nargis]], [[Meena Kumari]], [[Nutan]], [[Madhubala]], [[Waheeda Rehman]] and [[Mala Sinha]].<ref name="actorsuntil90"/> |

|||

While commercial Hindi cinema was thriving, the 1950s also saw the emergence of a new [[Parallel Cinema]] movement.<ref name=Gokulsing-18/> Though the movement was mainly led by [[Bengali cinema]], it also began gaining prominence in Hindi cinema. Early examples of Hindi films in this movement include [[Chetan Anand]]'s ''[[Neecha Nagar]]'' (1946)<ref name=Hindu>[http://www.thehindu.com/fr/2007/06/15/stories/2007061551020100.htm Maker of innovative, meaningful movies]. ''[[The Hindu]]'', June 15, 2007</ref> and Bimal Roy's ''[[Two Acres of Land]]'' (1953). Their critical acclaim, as well as the latter's commercial success, paved the way for Indian [[Neorealism (art)|neorealism]]<ref name=filmreference>[http://www.filmreference.com/Films-De-Dr/Do-Bigha-Zamin.html Do Bigha Zamin at filmreference]</ref> and the ''Indian New Wave''.<ref>{{cite web|title=Do Bigha Zamin: Seeds of the Indian New Wave|author=Srikanth Srinivasan|publisher=Dear Cinema|date=August 4, 2008|url=http://dearcinema.com/review-do-bigha-zamin-bimal-roy|accessdate=2009-04-13}}</ref> Some of the internationally-acclaimed Hindi filmmakers involved in the movement included [[Mani Kaul]], [[Kumar Shahani]], [[Ketan Mehta]], [[Govind Nihalani]], [[Shyam Benegal]] and [[Vijaya Mehta]].<ref name=Gokulsing-18/> |

While commercial Hindi cinema was thriving, the 1950s also saw the emergence of a new [[Parallel Cinema]] movement.<ref name=Gokulsing-18/> Though the movement was mainly led by [[Bengali cinema]], it also began gaining prominence in Hindi cinema. Early examples of Hindi films in this movement include [[Chetan Anand (producer & director)|Chetan Anand]]'s ''[[Neecha Nagar]]'' (1946)<ref name=Hindu>[http://www.thehindu.com/fr/2007/06/15/stories/2007061551020100.htm Maker of innovative, meaningful movies]. ''[[The Hindu]]'', June 15, 2007</ref> and Bimal Roy's ''[[Two Acres of Land]]'' (1953). Their critical acclaim, as well as the latter's commercial success, paved the way for Indian [[Neorealism (art)|neorealism]]<ref name=filmreference>[http://www.filmreference.com/Films-De-Dr/Do-Bigha-Zamin.html Do Bigha Zamin at filmreference]</ref> and the ''Indian New Wave''.<ref>{{cite web|title=Do Bigha Zamin: Seeds of the Indian New Wave|author=Srikanth Srinivasan|publisher=Dear Cinema|date=August 4, 2008|url=http://dearcinema.com/review-do-bigha-zamin-bimal-roy|accessdate=2009-04-13}}</ref> Some of the internationally-acclaimed Hindi filmmakers involved in the movement included [[Mani Kaul]], [[Kumar Shahani]], [[Ketan Mehta]], [[Govind Nihalani]], [[Shyam Benegal]] and [[Vijaya Mehta]].<ref name=Gokulsing-18/> |

||

Ever since the [[Socialist realism|social realist]] film ''Neecha Nagar'' won the [[Palme d'Or|Grand Prize]] at the [[1946 Cannes Film Festival|first Cannes Film Festival]],<ref name=Hindu/> Hindi films were frequently in competition for the [[Palme d'Or]] at the [[Cannes Film Festival]] throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, with some of them winning major prizes at the festival.<ref name=passionforcinema>{{cite web|title=India and Cannes: A Reluctant Courtship|publisher=Passion For Cinema|year=2008|url=http://passionforcinema.com/india-and-cannes-a-reluctant-courtship|accessdate=2009-05-20}}</ref> [[Guru Dutt]], while overlooked in his own lifetime, had belatedly generated international recognition much later in the 1980s.<ref name=passionforcinema/><ref>{{citation|title=Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change|last=K. Moti Gokulsing|first=K. Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake|publisher=Trentham Books|year=2004|isbn=1858563291|page=18-9}}</ref> Dutt is now regarded as one of the greatest [[Asian cinema|Asian filmmakers]] of all time, alongside the more famous Indian Bengali filmmaker [[Satyajit Ray]]. The 2002 ''[[Sight & Sound]]'' critics' and directors' poll of greatest filmmakers ranked Dutt at #73 on the list.<ref name=Lee>{{cite web|title=A Slanted Canon|author=Kevin Lee|publisher=Asian American Film Commentary|date=2002-09-05|url=http://www.asianamericanfilm.com/archives/000026.html|accessdate=2009-04-24}}</ref> Some of his films are now included among the [[Films considered the greatest ever|greatest films of all time]], with ''[[Pyaasa]]'' being featured in [[Time magazine's "All-TIME" 100 best movies]] list,<ref name=Time>{{cite web|url=http://www.time.com/time/2005/100movies/the_complete_list.html|title=[[Time magazine's "All-TIME" 100 best movies|All-Time 100 Best Movies]]|year=2005|accessdate=2008-05-19|work=[[Time (magazine)|Time]]|publisher=Time, Inc.}}</ref> and with both ''Pyaasa'' and ''[[Kaagaz Ke Phool]]'' tied at #160 in the 2002 ''Sight & Sound'' critics' and directors' poll of all-time greatest films. Several other Hindi films from this era were also ranked in the ''Sight & Sound'' poll, including [[Raj Kapoor]]'s ''[[Awaara]]'' |

Ever since the [[Socialist realism|social realist]] film ''Neecha Nagar'' won the [[Palme d'Or|Grand Prize]] at the [[1946 Cannes Film Festival|first Cannes Film Festival]],<ref name=Hindu/> Hindi films were frequently in competition for the [[Palme d'Or]] at the [[Cannes Film Festival]] throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, with some of them winning major prizes at the festival.<ref name=passionforcinema>{{cite web|title=India and Cannes: A Reluctant Courtship|publisher=Passion For Cinema|year=2008|url=http://passionforcinema.com/india-and-cannes-a-reluctant-courtship|accessdate=2009-05-20}}</ref> [[Guru Dutt]], while overlooked in his own lifetime, had belatedly generated international recognition much later in the 1980s.<ref name=passionforcinema/><ref>{{citation|title=Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change|last=K. Moti Gokulsing|first=K. Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake|publisher=Trentham Books|year=2004|isbn=1858563291|page=18-9}}</ref> Dutt is now regarded as one of the greatest [[Asian cinema|Asian filmmakers]] of all time, alongside the more famous Indian Bengali filmmaker [[Satyajit Ray]]. The 2002 ''[[Sight & Sound]]'' critics' and directors' poll of greatest filmmakers ranked Dutt at #73 on the list.<ref name=Lee>{{cite web|title=A Slanted Canon|author=Kevin Lee|publisher=Asian American Film Commentary|date=2002-09-05|url=http://www.asianamericanfilm.com/archives/000026.html|accessdate=2009-04-24}}</ref> Some of his films are now included among the [[Films considered the greatest ever|greatest films of all time]], with ''[[Pyaasa]]'' (1957) being featured in [[Time magazine's "All-TIME" 100 best movies]] list,<ref name=Time>{{cite web|url=http://www.time.com/time/2005/100movies/the_complete_list.html|title=[[Time magazine's "All-TIME" 100 best movies|All-Time 100 Best Movies]]|year=2005|accessdate=2008-05-19|work=[[Time (magazine)|Time]]|publisher=Time, Inc.}}</ref> and with both ''Pyaasa'' and ''[[Kaagaz Ke Phool]]'' (1959) tied at #160 in the 2002 ''Sight & Sound'' critics' and directors' poll of all-time greatest films. Several other Hindi films from this era were also ranked in the ''Sight & Sound'' poll, including [[Raj Kapoor]]'s ''[[Awaara]]'' (1951), [[Vijay Bhatt]]'s ''[[Baiju Bawra (1952 film)|Baiju Bawra]]'' (1952), [[Mehboob Khan]]'s ''[[Mother India]]'' (1957) and [[K. Asif]]'s ''[[Mughal-e-Azam]]'' (1960) all tied at #346 on the list.<ref name=Cinemacom>{{cite web|title=2002 Sight & Sound Top Films Survey of 253 International Critics & Film Directors|publisher=Cinemacom|year=2002|url=http://www.cinemacom.com/2002-sight-sound.html|accessdate=2009-04-19}}</ref> |

||

===Modern cinema=== |

===Modern cinema=== |

||

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, romance movies and action films starred actors like [[Rajesh Khanna]] and [[Dharmendra]], and actresses like [[Sharmila Tagore]], [[Mumtaz (actress)|Mumtaz]], [[Leena Chandavarkar]] and [[Helen (actress)|Helen]]. In the mid-1970s, romantic confections made way for gritty, violent films about gangsters (see [[Indian mafia]]) and bandits. [[Amitabh Bachchan]], the star known for his "angry young man" roles, rode the crest of this trend with actors like [[Mithun Chakraborty]] and [[Anil Kapoor]], which lasted into the early 1990s. Actresses from this era included [[Hema Malini]], [[Jaya Bachchan]] and [[Rekha]].<ref name="actorsuntil90">{{cite web|title=The Present|author=Ahmed, Rauf|publisher=[[Rediff.com]]|url=http://www.rediff.com/millenni/rauf2.htm|accessdate=2008-06-30}}</ref> |

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, romance movies and action films starred actors like [[Rajesh Khanna]] and [[Dharmendra]], and actresses like [[Sharmila Tagore]], [[Mumtaz (actress)|Mumtaz]], [[Leena Chandavarkar]] and [[Helen (actress)|Helen]]. In the mid-1970s, romantic confections made way for gritty, violent films about gangsters (see [[Indian mafia]]) and bandits. [[Amitabh Bachchan]], the star known for his "angry young man" roles, rode the crest of this trend with actors like [[Mithun Chakraborty]] and [[Anil Kapoor]], which lasted into the early 1990s. Actresses from this era included [[Hema Malini]], [[Jaya Bachchan]] and [[Rekha]].<ref name="actorsuntil90">{{cite web|title=The Present|author=Ahmed, Rauf|publisher=[[Rediff.com]]|url=http://www.rediff.com/millenni/rauf2.htm|accessdate=2008-06-30}}</ref> |

||

Some Hindi filmmakers such as [[Shyam Benegal]] continued to produce realistic [[Parallel Cinema]] throughout the 1970s,<ref name=Rajadhyaksa96-685>Rajadhyaksa, 685</ref> alongside [[Mani Kaul]], [[Kumar Shahani]], [[Ketan Mehta]], [[Govind Nihalani]] and [[Vijaya Mehta]].<ref name=Gokulsing-18/> However, the 'art film' bent of the Film Finance Corporation came under criticism during a Committee on Public Undertakings investigation in 1976, which accused the body of not doing enough to encourage commercial cinema. The 1970s thus saw the rise of commercial cinema in the form of enduring films such as ''[[Sholay]]'' (1975), which solidified Amitabh Bachchan's position as a lead actor. The devotional classic ''[[Jai Santoshi Ma]]'' was also released in 1975.<ref name=Rajadhyaksa96-688>Rajadhyaksa, 688</ref> Another important film from 1975 was ''[[Deewar (1975 film)|Deewar]]'', directed by [[Yash Chopra]] and written by [[Salim-Javed]]. A [[crime film]] pitting "a policeman against his brother, a gang leader based on real-life smuggler [[Haji Mastan]]", portrayed by Amitabh Bachchan, it was described as being “absolutely key to Indian cinema” by [[Danny Boyle]].<ref name=Kumar/> The most internationally-acclaimed Hindi film of the 1980s was [[Mira Nair]]'s ''[[Salaam Bombay!]]'' (1988), which won the [[Camera d'Or]] at the [[1988 Cannes Film Festival]] and was nominated for the [[Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film]]. |

|||

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the pendulum swung back toward family-centric romantic musicals with the success of such films as ''[[Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak]]'' (1988), ''[[Maine Pyar Kiya]]'' (1989), ''[[Hum Aapke Hain Kaun]]'' (1994) and ''[[Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge]]'' (1995), making stars out of a new generation of actors (such as [[Aamir Khan]], [[Salman Khan]] and [[Shahrukh Khan]]) and actresses (such as [[Sridevi]], [[Madhuri Dixit]], [[Juhi Chawla]] and [[Kajol]]).<ref name="actorsuntil90"/> In that point of time, action and comedy films were also successful, with actors like [[Govinda (actor)|Govinda]] and [[Akshay Kumar]] and actresses such as [[Raveena Tandon]] and [[Karisma Kapoor]] appearing in films of this genre. Furthermore, this decade marked the entry of new performers in [[Art films|art]] and independent films, some of which succeeded commercially, the most influential example being ''[[Satya (film)|Satya]]'' (1998), directed by [[Ram Gopal Varma]] and written by [[Anurag Kashyap (director)|Anurag Kashyap]]. The critical and commerical success of ''Satya'' led to the emergence of a distinct genre known as ''[[Mumbai noir]]'',<ref name=Nayar>{{cite news| title = Bollywood on the table| author = Aruti Nayar| work = The Tribune| date = 2007-12-16| accessdate = 2008-06-19| url = http://www.tribuneindia.com/2007/20071216/spectrum/main11.htm}}</ref> urban films reflecting social problems in the city of [[Mumbai]].<ref name=Jungen>{{cite web|title=Urban Movies: The Diversity of Indian Cinema|author=Christian Jungen|publisher=[[FIPRESCI]]|date=April 4, 2009|url=http://www.fipresci.org/festivals/archive/2009/fribourg/indian_cinema_chjungen.htm|accessdate=2009-05-11}}</ref> This led to a resurgence of [[Parallel Cinema]] by the end of the decade. These films often featured actors like [[Nana Patekar]], [[Manoj Bajpai]], [[Manisha Koirala]], [[Tabu (actress)|Tabu]] and [[Urmila Matondkar]], whose performances were usually acclaimed by critics. |

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the pendulum swung back toward family-centric romantic musicals with the success of such films as ''[[Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak]]'' (1988), ''[[Maine Pyar Kiya]]'' (1989), ''[[Hum Aapke Hain Kaun]]'' (1994) and ''[[Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge]]'' (1995), making stars out of a new generation of actors (such as [[Aamir Khan]], [[Salman Khan]] and [[Shahrukh Khan]]) and actresses (such as [[Sridevi]], [[Madhuri Dixit]], [[Juhi Chawla]] and [[Kajol]]).<ref name="actorsuntil90"/> In that point of time, action and comedy films were also successful, with actors like [[Govinda (actor)|Govinda]] and [[Akshay Kumar]] and actresses such as [[Raveena Tandon]] and [[Karisma Kapoor]] appearing in films of this genre. Furthermore, this decade marked the entry of new performers in [[Art films|art]] and independent films, some of which succeeded commercially, the most influential example being ''[[Satya (film)|Satya]]'' (1998), directed by [[Ram Gopal Varma]] and written by [[Anurag Kashyap (director)|Anurag Kashyap]]. The critical and commerical success of ''Satya'' led to the emergence of a distinct genre known as ''[[Mumbai noir]]'',<ref name=Nayar>{{cite news| title = Bollywood on the table| author = Aruti Nayar| work = The Tribune| date = 2007-12-16| accessdate = 2008-06-19| url = http://www.tribuneindia.com/2007/20071216/spectrum/main11.htm}}</ref> urban films reflecting social problems in the city of [[Mumbai]].<ref name=Jungen>{{cite web|title=Urban Movies: The Diversity of Indian Cinema|author=Christian Jungen|publisher=[[FIPRESCI]]|date=April 4, 2009|url=http://www.fipresci.org/festivals/archive/2009/fribourg/indian_cinema_chjungen.htm|accessdate=2009-05-11}}</ref> This led to a resurgence of [[Parallel Cinema]] by the end of the decade. These films often featured actors like [[Nana Patekar]], [[Manoj Bajpai]], [[Manisha Koirala]], [[Tabu (actress)|Tabu]] and [[Urmila Matondkar]], whose performances were usually acclaimed by critics. |

||

| Line 41: | Line 45: | ||

*Western '''musical television''', particularly [[MTV]], which has had an increasing influence since the 1990s, as can be seen in the pace, camera angles, dance sequences and music of 2000s Indian films. An early example of this approach was in [[Mani Ratnam]]'s ''[[Bombay (film)|Bombay]]'' (1995).<ref>{{citation|title=Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change|last=K. Moti Gokulsing|first=K. Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake|publisher=Trentham Books|year=2004|isbn=1858563291|page=99}}</ref> |

*Western '''musical television''', particularly [[MTV]], which has had an increasing influence since the 1990s, as can be seen in the pace, camera angles, dance sequences and music of 2000s Indian films. An early example of this approach was in [[Mani Ratnam]]'s ''[[Bombay (film)|Bombay]]'' (1995).<ref>{{citation|title=Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change|last=K. Moti Gokulsing|first=K. Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake|publisher=Trentham Books|year=2004|isbn=1858563291|page=99}}</ref> |

||

==Influence== |

|||

In the 2000s, Bollywood began influencing [[musical film]]s in the [[Western world]], and played a particularly instrumental role in the revival of the American musical film genre. [[Baz Luhrmann]] stated that his successful musical film ''[[Moulin Rouge!]]'' (2001) was directly inspired by Bollywood musicals.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://movies.about.com/library/weekly/aa030902a.htm|title=Baz Luhrmann Talks Awards and "Moulin Rouge"}}</ref> The film thus pays homage to India, incorporating an Indian-themed play based on the ancient [[Sanskrit drama|Sanskrit]] drama ''[[Mṛcchakatika|The Little Clay Cart]]'' and a Bollywood-style dance sequence with a song from the film ''[[China Gate (1998 film)|China Gate]]''. The critical and financial success of ''Moulin Rouge!'' renewed interest in the then-moribund Western musical genre, and subsequently films such as ''[[Chicago (2002 film)|Chicago]], [[The Producers (2005 film)|The Producers]], [[Rent (film)|Rent]]'', ''[[Dreamgirls (film)|Dreamgirls]]'', ''[[Hairspray (2007 film)|Hairspray]]'', ''[[Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2007 film)|Sweeney Todd]]'', ''[[Across the Universe (film)|Across the Universe]]'', ''[[The Phantom of the Opera (2004 film)|The Phantom of the Opera]]'', ''[[Enchanted (film)|Enchanted]]'' and ''[[Mamma Mia! (film)|Mamma Mia!]]'' were produced, fueling a renaissance of the genre.<ref>{{cite web|title=Guide Picks - Top Movie Musicals on Video/DVD|publisher=[[About.com]]|url=http://movies.about.com/library/weekly/aatpmusicals.htm|accessdate=2009-05-15}}</ref> |

In the 2000s, Bollywood began influencing [[musical film]]s in the [[Western world]], and played a particularly instrumental role in the revival of the American musical film genre. [[Baz Luhrmann]] stated that his successful musical film ''[[Moulin Rouge!]]'' (2001) was directly inspired by Bollywood musicals.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://movies.about.com/library/weekly/aa030902a.htm|title=Baz Luhrmann Talks Awards and "Moulin Rouge"}}</ref> The film thus pays homage to India, incorporating an Indian-themed play based on the ancient [[Sanskrit drama|Sanskrit]] drama ''[[Mṛcchakatika|The Little Clay Cart]]'' and a Bollywood-style dance sequence with a song from the film ''[[China Gate (1998 film)|China Gate]]''. The critical and financial success of ''Moulin Rouge!'' renewed interest in the then-moribund Western musical genre, and subsequently films such as ''[[Chicago (2002 film)|Chicago]], [[The Producers (2005 film)|The Producers]], [[Rent (film)|Rent]]'', ''[[Dreamgirls (film)|Dreamgirls]]'', ''[[Hairspray (2007 film)|Hairspray]]'', ''[[Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2007 film)|Sweeney Todd]]'', ''[[Across the Universe (film)|Across the Universe]]'', ''[[The Phantom of the Opera (2004 film)|The Phantom of the Opera]]'', ''[[Enchanted (film)|Enchanted]]'' and ''[[Mamma Mia! (film)|Mamma Mia!]]'' were produced, fueling a renaissance of the genre.<ref>{{cite web|title=Guide Picks - Top Movie Musicals on Video/DVD|publisher=[[About.com]]|url=http://movies.about.com/library/weekly/aatpmusicals.htm|accessdate=2009-05-15}}</ref> |

||

| Line 191: | Line 196: | ||

==Plagiarism== |

==Plagiarism== |

||

Constrained by rushed production schedules and small budgets, certain Bollywood writers and musicians have been known to resort to plagiarism. They copy ideas, plot lines, tunes or riffs from sources close at hand from other Indian films or far away (including [[Cinema of the United States|Hollywood]] and [[ |

Constrained by rushed production schedules and small budgets, certain Bollywood writers and musicians have been known to resort to plagiarism. They copy ideas, plot lines, tunes or riffs from sources close at hand from other Indian films or far away (including [[Cinema of the United States|Hollywood]] and other [[Asian cinema|Asian films]]). This has lead to criticism towards the film industry.<ref name="Times plagiarism">{{cite web|url=http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/cms.dll/html/uncomp/articleshow?msid=46715385|title=Plagiarism issue jolts Bollywood.|publisher=The Times Of India|accessdate=2007-10-17}}</ref> |

||

In past times, this could be done with impunity. Copyright enforcement was lax in India and few actors or directors ever saw an official contract.<ref name="Ayres">{{cite book|author=Ayres, Alyssa; Oldenburg, Philip|url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=gi7w-vTfELsC&pg=PA174&dq=bollywood+plagiarism#PPA174,M1|title=India briefing: takeoff at last|publisher=M.E. Sharpe|date=2005|pages=174}}</ref> The Hindi film industry was not widely known to non-Indian audiences (excluding the [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] states), who would not even be aware that their material was being copied. Audiences may also not have been aware of the plagiarism since many audiences in India were unfamiliar with foreign films and music. While copyright enforcement in India is still somewhat lenient, Bollywood and other film industries are much more aware of each other now and Indian audiences are more familiar with foreign movies and music. Organizations like the India EU Film Initiative seek to foster a community between film makers and industry professionel between India and the EU.<ref name="Times plagiarism"/> |

In past times, this could be done with impunity. Copyright enforcement was lax in India and few actors or directors ever saw an official contract.<ref name="Ayres">{{cite book|author=Ayres, Alyssa; Oldenburg, Philip|url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=gi7w-vTfELsC&pg=PA174&dq=bollywood+plagiarism#PPA174,M1|title=India briefing: takeoff at last|publisher=M.E. Sharpe|date=2005|pages=174}}</ref> The Hindi film industry was not widely known to non-Indian audiences (excluding the [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] states), who would not even be aware that their material was being copied. Audiences may also not have been aware of the plagiarism since many audiences in India were unfamiliar with foreign films and music. While copyright enforcement in India is still somewhat lenient, Bollywood and other film industries are much more aware of each other now and Indian audiences are more familiar with foreign movies and music. Organizations like the India EU Film Initiative seek to foster a community between film makers and industry professionel between India and the EU.<ref name="Times plagiarism"/> |

||

| Line 226: | Line 231: | ||

* Raheja, Dinesh and Kothari, Jitendra. ''Indian Cinema: The Bollywood Saga''. (ISBN 81-7436-285-1) |

* Raheja, Dinesh and Kothari, Jitendra. ''Indian Cinema: The Bollywood Saga''. (ISBN 81-7436-285-1) |

||

* Raj, Aditya (2007) "Bollywood Cinema and Indian Diaspora" in ''Media Literacy: A Reader'' edited by Donaldo Macedo and Shirley Steinberg New York: Peter Lang |

* Raj, Aditya (2007) "Bollywood Cinema and Indian Diaspora" in ''Media Literacy: A Reader'' edited by Donaldo Macedo and Shirley Steinberg New York: Peter Lang |

||

* Rajadhyaksa, Ashish (1996), "India: Filming the Nation", ''The Oxford History of World Cinema'', Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198112572. |

|||

* Rajadhyaksha, Ashish and Willemen, Paul. ''Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema'', Oxford University Press, revised and expanded, 1999. |

* Rajadhyaksha, Ashish and Willemen, Paul. ''Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema'', Oxford University Press, revised and expanded, 1999. |

||

Revision as of 07:56, 24 May 2009

Bollywood (Hindi: बॉलीवूड) is the informal term popularly used for the Hindi-language film industry based in Mumbai, India. The term is often incorrectly used to refer to the whole of Indian cinema; it is only a part of the Indian film industry.[1] Bollywood is the largest film producer in India and one of the largest in the world.[2][3][4]

The name is a portmanteau of Bombay (the former name for Mumbai) and Hollywood, the center of the American film industry.[5] However, unlike Hollywood, Bollywood does not exist as a physical place. Though some deplore the name, arguing that it makes the industry look like a poor cousin to Hollywood,[5][6] it has its own entry in the Oxford English Dictionary.

Bollywood is often referred to as Hindi cinema, even though frequent use of poetic Urdu words is fairly common. There has been a growing presence of Indian English in dialogue and songs as well. It is not uncommon to see films that feature dialogue with English words and phrases, even whole sentences. There is a growing number of films made entirely in English.[7]

History

Raja Harishchandra (1913), by Dadasaheb Phalke, was the first silent feature film made in India. By the 1930s, the industry was producing over 200 films per annum. The first Indian sound film, Ardeshir Irani's Alam Ara (1931), was a major commercial success. There was clearly a huge market for talkies and musicals; Bollywood and all the regional film industries quickly switched to sound filming.

The 1930s and 1940s were tumultuous times: India was buffeted by the Great Depression, World War II, the Indian independence movement, and the violence of the Partition. Most Bollywood films were unabashedly escapist, but there were also a number of filmmakers who tackled tough social issues, or used the struggle for Indian independence as a backdrop for their plots.

In 1937, Ardeshir Irani, of Alam Ara fame, made the first colour film in Hindi, Kisan Kanya. The next year, he made another colour film, Mother India. However, colour did not become a popular feature until the late 1950s. At this time, lavish romantic musicals and melodramas were the staple fare at the cinema.

Golden Age

Following India's independence, the period from the late 1940s to the 1960s are regarded by film historians as the "Golden Age" of Hindi cinema.[8][9][10] Some of the most critically-acclaimed Hindi films of all time were produced during this period. Examples include the Guru Dutt films Pyaasa (1957) and Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959) and the Raj Kapoor films Awaara (1951) and Shree 420 (1955). These films expressed social themes mainly dealing with working-class urban life in India; Awaara presented the city as both a nightmare and a dream, while Pyaasa critiqued the unreality of city life.[11] Some of the most famous epic films of Hindi cinema were also produced at the time, including Mehboob Khan's Mother India (1957), which was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film,[12] and K. Asif's Mughal-e-Azam (1960).[13] Madhumati (1958), directed by Bimal Roy and written by Ritwik Ghatak, popularized the theme of reincarnation in Western popular culture.[14] Other acclaimed mainstream Hindi filmmakers at the time included V. Shantaram, Kamal Amrohi and Vijay Bhatt. Successful actors at the time included Dev Anand, Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor and Guru Dutt, while successful actresses included Nargis, Meena Kumari, Nutan, Madhubala, Waheeda Rehman and Mala Sinha.[15]

While commercial Hindi cinema was thriving, the 1950s also saw the emergence of a new Parallel Cinema movement.[11] Though the movement was mainly led by Bengali cinema, it also began gaining prominence in Hindi cinema. Early examples of Hindi films in this movement include Chetan Anand's Neecha Nagar (1946)[16] and Bimal Roy's Two Acres of Land (1953). Their critical acclaim, as well as the latter's commercial success, paved the way for Indian neorealism[17] and the Indian New Wave.[18] Some of the internationally-acclaimed Hindi filmmakers involved in the movement included Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Ketan Mehta, Govind Nihalani, Shyam Benegal and Vijaya Mehta.[11]

Ever since the social realist film Neecha Nagar won the Grand Prize at the first Cannes Film Festival,[16] Hindi films were frequently in competition for the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, with some of them winning major prizes at the festival.[19] Guru Dutt, while overlooked in his own lifetime, had belatedly generated international recognition much later in the 1980s.[19][20] Dutt is now regarded as one of the greatest Asian filmmakers of all time, alongside the more famous Indian Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray. The 2002 Sight & Sound critics' and directors' poll of greatest filmmakers ranked Dutt at #73 on the list.[21] Some of his films are now included among the greatest films of all time, with Pyaasa (1957) being featured in Time magazine's "All-TIME" 100 best movies list,[22] and with both Pyaasa and Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959) tied at #160 in the 2002 Sight & Sound critics' and directors' poll of all-time greatest films. Several other Hindi films from this era were also ranked in the Sight & Sound poll, including Raj Kapoor's Awaara (1951), Vijay Bhatt's Baiju Bawra (1952), Mehboob Khan's Mother India (1957) and K. Asif's Mughal-e-Azam (1960) all tied at #346 on the list.[23]

Modern cinema

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, romance movies and action films starred actors like Rajesh Khanna and Dharmendra, and actresses like Sharmila Tagore, Mumtaz, Leena Chandavarkar and Helen. In the mid-1970s, romantic confections made way for gritty, violent films about gangsters (see Indian mafia) and bandits. Amitabh Bachchan, the star known for his "angry young man" roles, rode the crest of this trend with actors like Mithun Chakraborty and Anil Kapoor, which lasted into the early 1990s. Actresses from this era included Hema Malini, Jaya Bachchan and Rekha.[15]

Some Hindi filmmakers such as Shyam Benegal continued to produce realistic Parallel Cinema throughout the 1970s,[24] alongside Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Ketan Mehta, Govind Nihalani and Vijaya Mehta.[11] However, the 'art film' bent of the Film Finance Corporation came under criticism during a Committee on Public Undertakings investigation in 1976, which accused the body of not doing enough to encourage commercial cinema. The 1970s thus saw the rise of commercial cinema in the form of enduring films such as Sholay (1975), which solidified Amitabh Bachchan's position as a lead actor. The devotional classic Jai Santoshi Ma was also released in 1975.[25] Another important film from 1975 was Deewar, directed by Yash Chopra and written by Salim-Javed. A crime film pitting "a policeman against his brother, a gang leader based on real-life smuggler Haji Mastan", portrayed by Amitabh Bachchan, it was described as being “absolutely key to Indian cinema” by Danny Boyle.[26] The most internationally-acclaimed Hindi film of the 1980s was Mira Nair's Salaam Bombay! (1988), which won the Camera d'Or at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, the pendulum swung back toward family-centric romantic musicals with the success of such films as Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1988), Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), Hum Aapke Hain Kaun (1994) and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), making stars out of a new generation of actors (such as Aamir Khan, Salman Khan and Shahrukh Khan) and actresses (such as Sridevi, Madhuri Dixit, Juhi Chawla and Kajol).[15] In that point of time, action and comedy films were also successful, with actors like Govinda and Akshay Kumar and actresses such as Raveena Tandon and Karisma Kapoor appearing in films of this genre. Furthermore, this decade marked the entry of new performers in art and independent films, some of which succeeded commercially, the most influential example being Satya (1998), directed by Ram Gopal Varma and written by Anurag Kashyap. The critical and commerical success of Satya led to the emergence of a distinct genre known as Mumbai noir,[27] urban films reflecting social problems in the city of Mumbai.[28] This led to a resurgence of Parallel Cinema by the end of the decade. These films often featured actors like Nana Patekar, Manoj Bajpai, Manisha Koirala, Tabu and Urmila Matondkar, whose performances were usually acclaimed by critics.

The 2000s saw a growth in Bollywood's popularity in the world. This led the nation's filmmaking to new heights in terms of quality, cinematography and innovative story lines as well as technical advances in areas such as special effects, animation, etc.[29] Some of the largest production houses, among them Yash Raj Films and Dharma Productions were the producers of new modern films.[29] The opening up of the overseas market, more Bollywood releases abroad and the explosion of multiplexes in big cities, led to wider box office successes in India and abroad, including Lagaan (2001), Devdas (2002), Koi... Mil Gaya (2003), Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003), Veer-Zaara (2004), Rang De Basanti (2006), Lage Raho Munnabhai (2006), Krrish (2006), Dhoom 2 (2006), Om Shanti Om (2007), Taare Zameen Par (2007), and Ghajini (2008), delivering a new generation of popular actors (Hrithik Roshan, Abhishek Bachchan) and actresses (Aishwarya Rai, Preity Zinta and Rani Mukerji[30][31]), and keeping the popularity of actors of the previous decade. Among the mainstream films, Lagaan won the Audience Award at the Locarno International Film Festival and was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the 74th Academy Awards, while Devdas and Rang De Basanti were both nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

The Hindi film industry has preferred films that appeal to all segments of the audience (see the discussion in Ganti, 2004, cited in references), and has resisted making films that target narrow audiences. It was believed that aiming for a broad spectrum would maximise box office receipts. However, filmmakers may be moving towards accepting some box-office segmentation, between films that appeal to rural Indians, and films that appeal to urban and overseas audiences.

Influences

There have generally been six major influences that have shaped the conventions of Indian popular cinema:

- The ancient Indian epics of Mahabharata and Ramayana which have exerted a profound influence on the thought and imagination of Indian popular cinema, particularly in its narratives. Examples of this influence include the techniques of a side story, back-story and story within a story. Indian popular films often have plots which branch off into sub-plots; such narrative dispersals can clearly be seen in the 1993 films Khalnayak and Gardish.[32]

- Ancient Sanskrit drama, with its highly stylized nature and emphasis on spectacle, where music, dance and gesture combined "to create a vibrant artistic unit with dance and mime being central to the dramatic experience." Sanskrit dramas were known as natya, derived from the root word nrit (dance), characterizing them as specacular dance-dramas which has continued Indian cinema.[32]

- The traditional folk theatre of India, which became popular from around the 10th century with the decline of Sanskrit theatre. These regional traditions include the Yatra of Bengal, the Ramlila of Uttar Pradesh, and the Terukkuttu of Tamil Nadu.[32]

- The Parsi theatre, which "blended realism and fantasy, music and dance, narrative and spectacle, earthy dialogue and ingenuity of stage presentation, integrating them into a dramatic discourse of melodrama. The Parsi plays contained crude humour, melodious songs and music, sensationalism and dazzling stagecraft."[32]

- Hollywood, where musicals were popular from the 1920s to the 1950s, though Indian filmmakers departed from their Hollywood counterparts in several ways. "For example, the Hollywood musicals had as their plot the world of entertainment itself. Indian filmmakers, while enhancing the elements of fantasy so pervasive in Indian popular films, used song and music as a natural mode of articulation in a given situation in their films. There is a strong Indian tradition of narrating mythology, history, fairy stories and so on through song and dance." In addition, "whereas Hollywood filmmakers strove to conceal the constructed nature of their work so that the realistic narrative was wholly dominant, Indian filmmakers made no attempt to conceal the fact that what was shown on the screen was a creation, an illusion, a fiction. However, they demonstrated how this creation intersected with people's day to day lives in complex and interesting ways."[33]

- Western musical television, particularly MTV, which has had an increasing influence since the 1990s, as can be seen in the pace, camera angles, dance sequences and music of 2000s Indian films. An early example of this approach was in Mani Ratnam's Bombay (1995).[34]

Influence

In the 2000s, Bollywood began influencing musical films in the Western world, and played a particularly instrumental role in the revival of the American musical film genre. Baz Luhrmann stated that his successful musical film Moulin Rouge! (2001) was directly inspired by Bollywood musicals.[35] The film thus pays homage to India, incorporating an Indian-themed play based on the ancient Sanskrit drama The Little Clay Cart and a Bollywood-style dance sequence with a song from the film China Gate. The critical and financial success of Moulin Rouge! renewed interest in the then-moribund Western musical genre, and subsequently films such as Chicago, The Producers, Rent, Dreamgirls, Hairspray, Sweeney Todd, Across the Universe, The Phantom of the Opera, Enchanted and Mamma Mia! were produced, fueling a renaissance of the genre.[36]

A. R. Rahman, an Indian film composer, wrote the music for Andrew Lloyd Webber's Bombay Dreams, and a musical version of Hum Aapke Hain Koun has played in London's West End. The Bollywood musical Lagaan (2001) was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and two other Bollywood films Devdas (2002) and Rang De Basanti (2006) were nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Danny Boyle's Slumdog Millionaire (2008), which has won four Golden Globes and eight Academy Awards, was also directly inspired by Bollywood films,[26][37] and is considered to be a "homage to Hindi commercial cinema".[16] Several other Hollywood films are also believed to have been inspired by Bollywood films. For example, the theme of reincarnation was popularized in Western popular culture through Bollywood films, with Madhumati (1958) inspiring the Hollywood film The Reincarnation of Peter Proud (1975),[14] which in turn inspired the Bollywood film Karz (1980), which in turn influenced another Hollywood film Chances Are (1989).[38]

The influence of Bollywood filmi music can also be seen in popular music elsewhere in the world. For example, Devo's 1988 hit song "Disco Dancer" was inspired by the song "I am a Disco Dancer" from the Bollywood film Disco Dancer (1982).[39] The 2002 song "Addictive", sung by Truth Hurts and produced by DJ Quik and Dr. Dre, was lifted from Lata Mangeshkar's "Thoda Resham Lagta Hai" from Jyoti (1981).[40] The Black Eyed Peas' Grammy Award winning 2005 song "Don't Phunk with My Heart" was inspired by two 1970s Bollywood songs: "Ye Mera Dil Yaar Ka Diwana" from Don (1978)[41] and "Ae Nujawan Hai Sub" from Apradh (1972).[42] Both songs were originally composed by Kalyanji Anandji, sung by Asha Bhosle, and featured the dancer Helen.[43] Also in 2005, the Kronos Quartet re-recorded several R. D. Burman compositions, with Asha Bhosle as the singer, into an album You've stolen my heart - Songs From R D Burman's Bollywood, which was nominated for "Best Contemporary World Music Album" at the 2006 Grammy Awards. Filmi music composed by A. R. Rahman (who would later win two Academy Awards for the Slumdog Millionaire soundtrack) has frequently been sampled by musicians elsewhere in the world, including the Singaporean artist Kelly Poon, the Uzbek artist Iroda Dilroz, the French rap group La Caution, the American artist Ciara, and the German band Löwenherz,[44] among others. Many artists among the overseas Indian diaspora have also been inspired by Bollywood music.

Genre conventions

Bollywood films are mostly musicals, and are expected to contain catchy music in the form of song-and-dance numbers woven into the script. A film's success often depends on the quality of such musical numbers.[45] Indeed, a film's music is often released before the movie itself and helps increase the audience.

Indian audiences expect full value for their money, with a good entertainer generally referred to as paisa vasool, (literally, "money's worth"). Songs and dances, love triangles, comedy and dare-devil thrills are all mixed up in a three-hour-long extravaganza with an intermission. Such movies are called masala films, after the Hindi word for a spice mixture. Like masalas, these movies are a mixture of many things such as action, comedy, romance etc. Most films have heroes who are able to fight off villains all by themselves.

Bollywood plots have tended to be melodramatic. They frequently employ formulaic ingredients such as star-crossed lovers and angry parents, love triangles, family ties, sacrifice, corrupt politicians, kidnappers, conniving villains, courtesans with hearts of gold, long-lost relatives and siblings separated by fate, dramatic reversals of fortune, and convenient coincidences.

There have always been Indian films with more artistic aims and more sophisticated stories, both inside and outside the Bollywood tradition (see Art cinema in India). They often lost out at the box office to movies with more mass appeal. Bollywood conventions are changing, however. A large Indian diaspora in English speaking countries, and increased Western influence at home, have nudged Bollywood films closer to Hollywood models.[46]

Film critic Lata Khubchandani writes,"..our earliest films...had liberal doses of sex and kissing scenes in them. Strangely, it was after Independence the censor board came into being and so did all the strictures."[47] Plots now tend to feature Westernised urbanites dating and dancing in clubs rather than centering on pre-arranged marriages. Though these changes can widely be seen in contemporary Bollywood, traditional conservative ways of Indian culture continue to exist in India outside the industry and an element of resistance by some to western-based influences.[46] Despite this, Bollywood continues to play a major role in fashion in India.[46] Indeed some studies into fashion in India have revealed that some people are unaware that the changing nature of fashion in Bollywood films which are presented to them are often influenced by globalisation and many consider the clothes worn by Bollywood actors as authentically Indian.[46]

Cast and crew

- for further details see Indian movie actors, Indian movie actresses, Indian film directors, Indian film music directors and Indian playback singers

Bollywood employs people from all parts of India. It attracts thousands of aspiring actors and actresses, all hoping for a break in the industry. Models and beauty contestants, television actors, theatre actors and even common people come to Mumbai with the hope and dream of becoming a star. Just as in Hollywood, very few succeed. Since many Bollywood films are shot abroad, many foreign extras are employed too.[48]

Stardom in the entertainment industry is very fickle, and Bollywood is no exception. The popularity of the stars can rise and fall rapidly. Directors compete to hire the most popular stars of the day, who are believed to guarantee the success of a movie (though this belief is not always supported by box-office results). Hence many stars make the most of their fame, once they become popular, by making several movies simultaneously.

Only a very few non-Indian actors are able to make a mark in Bollywood, though many have tried from time to time. There have been some exceptions, one recent example is the hit film Rang De Basanti, where the lead actress is Alice Patten, an Englishwoman. Kisna, Lagaan, and The Rising: Ballad of Mangal Pandey also featured foreign actors.

Bollywood can be very clannish, and the relatives of film-industry insiders have an edge in getting coveted roles in films and/or being part of a film's crew. However, industry connections are no guarantee of a long career: competition is fierce and if film industry scions do not succeed at the box office, their careers will falter. Some of the biggest stars, such as Dharmendra, Amitabh Bachchan, and Shahrukh Khan have succeeded despite total lack of show business connections. For film clans, see List of Bollywood film clans.

Sound

Sound in Bollywood films is rarely recorded on location (otherwise known as sync sound). Therefore, the sound is usually created (or recreated) entirely in the studio, with the actors reciting their lines as their images appear on-screen in the studio in the process known as "looping in the sound" or ADR—with the foley and sound effects added later. This creates several problems, since the sound in these films usually occurs a frame or two earlier or later than the mouth movements or gestures. The actors have to act twice: once on-location, once in the studio—and the emotional level on set is often very difficult to recreate. Commercial Indian films, not just the Hindi-language variety, are known for their lack of ambient sound, so there is a silence underlying everything instead of the background sound and noises usually employed in films to create aurally perceivable depth and environment.

The ubiquity of ADR in Bollywood cinema became prevalent in the early 1960s with the arrival of the Arriflex 3 camera, which required a blimp (cover) in order to shield the sound of the camera, for which it was notorious, from on-location filming. Commercial Indian filmmakers, known for their speed, never bothered to blimp the camera, and its excessive noise required that everything had to be recreated in the studio. Eventually, this became the standard for Indian films.

The trend was bucked in 2001, after a 30-year hiatus of synchronized sound, with the film Lagaan, in which producer-star Aamir Khan insisted that the sound be done on location. This opened up a heated debate on the use and economic feasibility of on-location sound, and several Bollywood films have employed on-location sound since then.

Bollywood song and dance

Bollywood film music is called filmi music (from Hindi, meaning "of films"). Songs from Bollywood movies are generally pre-recorded by professional playback singers, with the actors then lip synching the words to the song on-screen, often while dancing. While most actors, especially today, are excellent dancers, few are also singers. One notable exception was Kishore Kumar, who starred in several major films in the 1950s while also having a stellar career as a playback singer. K. L. Saigal, Suraiyya, and Noor Jehan were also known as both singers and actors. Some actors in the last thirty years have sung one or more songs themselves; for a list, see Singing actors and actresses in Indian cinema.

Playback singers are prominently featured in the opening credits and have their own fans who will go to an otherwise lackluster movie just to hear their favourites. Going by the quality as well as the quantity of the songs they rendered, most notable singers of Bollywood are Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle, Geeta Dutt, Shamshad Begum and Alka Yagnik among female playback singers; and K. L. Saigal, Talat Mahmood, Mukesh, Mohammed Rafi, Manna Dey, Hemant Kumar, Kishore Kumar, Kumar Sanu,S.P.Balasubramanyam,Udit Narayan and Sonu Nigam among male playback singers. Mohammed Rafi is often considered arguably the finest of the singers that have lent their voice to Bollywood songs, followed by Lata Mangeshkar, who, through the course of a career spanning over six decades, has recorded thousands of songs for Indian movies. The composers of film music, known as music directors, are also well-known. Their songs can make or break a film and usually do. Remixing of film songs with modern beats and rhythms is a common occurrence today, and producers may even release remixed versions of some of their films' songs along with the films' regular soundtrack albums.

The dancing in Bollywood films, especially older ones, is primarily modelled on Indian dance: classical dance styles, dances of historic northern Indian courtesans (tawaif), or folk dances. In modern films, Indian dance elements often blend with Western dance styles (as seen on MTV or in Broadway musicals), though it is not unusual to see Western pop and pure classical dance numbers side by side in the same film. The hero or heroine will often perform with a troupe of supporting dancers. Many song-and-dance routines in Indian films feature unrealistically instantaneous shifts of location and/or changes of costume between verses of a song. If the hero and heroine dance and sing a pas de deux, it is often staged in beautiful natural surroundings or architecturally grand settings. This staging is referred to as a "picturisation".

Songs typically comment on the action taking place in the movie, in several ways. Sometimes, a song is worked into the plot, so that a character has a reason to sing; other times, a song is an externalisation of a character's thoughts, or presages an event that has not occurred yet in the plot of the movie. In this case, the event is almost always two characters falling in love.

Bollywood films have always used what are now called "item numbers". A physically attractive female character (the "item girl"), often completely unrelated to the main cast and plot of the film, performs a catchy song and dance number in the film. In older films, the "item number" may be performed by a courtesan (tawaif) dancing for a rich client or as part of a cabaret show. The dancer Helen was famous for her cabaret numbers. In modern films, item numbers may be inserted as discotheque sequences, dancing at celebrations, or as stage shows.

For the last few decades Bollywood producers have been releasing the film's soundtrack, as tapes or CDs, before the main movie release, hoping that the music will pull audiences into the cinema later. Often the soundtrack is more popular than the movie. In the last few years some producers have also been releasing music videos, usually featuring a song from the film. However, some promotional videos feature a song which is not included in the movie.

Dialogues and lyrics

The film script or lines of dialogue (called "dialogues" in Indian English) and the song lyrics are often written by different people.

Dialogues are usually written in an unadorned Hindi or Hindustani that would be understood by the largest possible audience. Some movies, however, have used regional dialects to evoke a village setting, or old-fashioned courtly Urdu in Mughal era historical films. Contemporary mainstream movies also make great use of English. In fact, many movie scripts are first written in English, and then translated into Hindi. Characters may shift from one language to the other to express a certain atmosphere (for example, English in a business setting and Hindi in an informal one).

Cinematic language, whether in dialogues or lyrics, is often melodramatic and invokes God, family, mother, duty, and self-sacrifice liberally.

Music directors often prefer working with certain lyricists, to the point that the lyricist and composer are seen as a team. This phenomenon is not unlike the pairings of American composers and songwriters that created old-time Broadway musicals (e.g., Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, or Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe). Song lyrics are usually about love. Bollywood song lyrics, especially in the old movies, frequently use Arabo-Persic Urdu vocabulary. Another source for love lyrics is the long Hindu tradition of poetry about the mythological amours of Krishna, Radha, and the gopis. Many lyrics compare the singer to a devotee and the object of his or her passion to Krishna or Radha.

Finances

Bollywood films are multi-million dollar productions, with the most expensive productions costing up to 100 crores Rupees (roughly USD 20 million). Sets, costumes, special effects, and cinematography were less than world-class up until the mid-to-late 1990s, although with some notable exceptions. As Western films and television gain wider distribution in India itself, there is increasing pressure for Bollywood films to attain the same production levels. In particular, in areas such as action and special effects. Recent Bollywood films have employed international technicians to improve in these areas, such as Krrish (2006) which has action choreographed by Hong Kong based Tony Ching. The increasing accessibility to professional action and special effects, coupled with rising film budgets, has seen an explosion in the action and sci-fi genres.

Sequences shot overseas have proved a real box office draw, so Mumbai film crews are increasingly filming in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the United States, continental Europe and elsewhere. Nowadays, Indian producers are winning more and more funding for big-budget films shot within India as well, such as Lagaan, Devdas and other recent films.

Funding for Bollywood films often comes from private distributors and a few large studios. Indian banks and financial institutions were forbidden from lending money to movie studios. However, this ban has now been lifted.[49] As finances are not regulated, some funding also comes from illegitimate sources, such as the Mumbai underworld. The Mumbai underworld has been known to be involved in the production of several films, and are notorious for their patronisation of several prominent film personalities; On occasion, they have been known to use money and muscle power to get their way in cinematic deals. In January, 2000, Mumbai mafia hitmen shot Rakesh Roshan, a film director and father of star Hrithik Roshan. In 2001, the Central Bureau of Investigation seized all prints of the movie Chori Chori Chupke Chupke after the movie was found to be funded by members of the Mumbai underworld.[50]

Another problem facing Bollywood is widespread copyright infringement of its films. Often, bootleg DVD copies of movies are available before the prints are officially released in cinemas. Manufacturing of bootleg DVD, VCD, and VHS copies of the latest movie titles is a well established 'small scale industry' in parts of South Asia and South East Asia. The Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) estimates that the Bollywood industry loses $100 million annually in loss of revenue from pirated home videos and DVDs. Besides catering to the homegrown market, demand for these copies is large amongst some sections of the Indian diaspora, too. (In fact, bootleg copies are the only way people in Pakistan can watch Bollywood movies, since the Government of Pakistan has banned their sale, distribution and telecast). Films are frequently broadcast without compensation by countless small cable TV companies in India and other parts of South Asia. Small convenience stores run by members of the Indian diaspora in the U.S. and the UK regularly stock tapes and DVDs of dubious provenance, while consumer copying adds to the problem. The availability of illegal copies of movies on the Internet also contributes to the piracy problem.

Satellite TV, television and imported foreign films are making huge inroads into the domestic Indian entertainment market. In the past, most Bollywood films could make money; now fewer tend to do so. However, most Bollywood producers make money, recouping their investments from many sources of revenue, including selling ancillary rights. There are also increasing returns from theatres in Western countries like the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States, where Bollywood is slowly getting noticed. As more Indians migrate to these countries, they form a growing market for upscale Indian films.

For an interesting comparison of Hollywood and Bollywood financial figures, see chart. It shows tickets sold in 2002 and total revenue estimates. Bollywood sold 3.6 billion tickets and had total revenues (theatre tickets, DVDs, television etc.) of US$1.3 billion, whereas Hollywood films sold 2.6 billion tickets and generated total revenues (again from all formats) of US$51 billion.

Advertising

Many Indian artists used to make a living by hand-painting movie billboards and posters (The well-known artist M.F. Hussain used to paint film posters early in his career) This was because human labour was found to be cheaper than printing and distributing publicity material.[51] Now, a majority of the huge and ubiquitous billboards in India's major cities are created with computer-printed vinyl. The old hand-painted posters, once regarded as ephemera, are becoming increasingly collectible as folk art.[51]

Releasing the film music, or music videos, before the actual release of the film can also be considered a form of advertising. A popular tune is believed to help pull audiences into the theaters.[52]

Bollywood publicists have begun to use the Internet as a venue for advertising. Most of the better-funded film releases now have their own websites, where browsers can view trailers, stills, and information about the story, cast, and crew.[53]

Bollywood is also used to advertise other products. Product placement, as used in Hollywood, is widely practiced in Bollywood.[54]

Bollywood movie stars appear in print and television advertisements for other products, such as watches or soap (see Celebrity endorsement). Advertisers say that a star endorsement boosts sales.

Awards

The Filmfare Awards ceremony is one of the most prominent film events given for Hindi films in India.[55] The Indian screen magazine Filmfare started the first Filmfare Awards in 1954, and awards were given to the best films of 1953. The ceremony was referred to as the Clare Awards after the magazine's editor. Modelled after the poll-based merit format of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, individuals may submit their votes in separate categories. A dual voting system was developed in 1956.[56] Like the Oscars, the Filmfare awards are frequently accused of bias towards commercial success rather than artistic merit.

As the Filmfare, the National Film Awards were introduced in 1954. Since 1973, the Indian government has sponsored the National Film Awards, awarded by the government run Directorate of Film Festivals (DFF). The DFF screens not only Bollywood films, but films from all the other regional movie industries and independent/art films. These awards are handed out at an annual ceremony presided over by the President of India. Under this system, in contrast to the National Film Awards, which are decided by a panel appointed by Indian Government, the Filmfare Awards are voted for by both the public and a committee of experts.[57]

Additional ceremonies held within India are:

Ceremonies held overseas are:

- Bollywood Movie Awards - Long Island, New York, United States

- Global Indian Film Awards - (different country each year)

- IIFA Awards - (different country each year)

- Zee Cine Awards- (different country each year)

Most of these award ceremonies are lavishly staged spectacles, featuring singing, dancing, and numerous celebrities.

Film education

- Film and Television Institute of India

- Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute

- Asian Academy of Film & Television

Popularity and appeal

Besides being popular among the India diaspora, such far off locations as Nigeria to Egypt to Senegal and to Russia generations of non-Indian fans have grown up with Bollywood during the years, bearing witness to the cross-cultural appeal of Indian movies.[58]

Over the last years of the twentieth century and beyond, Bollywood progressed in its popularity as it entered the consciousness of Western audiences and producers.[29][59]

Asia

Bollywood films are widely watched in South Asian countries, such as Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Most Pakistanis watch Bollywood films,[60] as they understand Hindi (due to its linguistic similarity to Urdu). Despite a government ban on Indian films since 1965,[60] a few Bollywood films were legally released in the country in 2006, including Taj Mahal and Mughal-e-Azam, decades after its release, though more movies followed.[61] For the most part, Bollywood movies are watched on cable television in Pakistan; there is also a huge market for Bollywood movies in local video stores. Historically, video piracy was another accessible venue to watch Indian movies.[62]

Bollywood movies are also popular in Afghanistan due to the country's proximity with the Indian subcontinent and certain other cultural perspectives present in the movies.[63] A number of Bollywood movies were filmed inside Afghanistan while some dealt with the country, including Dharmatma, Kabul Express, Khuda Gawah and Escape From Taliban.[64][65] Hindi films have also been popular in numerous Arab countries, including Palestine, Jordan, Egypt and the Gulf countries.[66] Imported Indian films are usually subtitled in Arabic upon the film's release. Since the early 2000s, Bollywood has progressed in Israel. Special channels dedicated to Indian films have been displayed on cable television.[67] Bollywood films are also popular across Southeast Asia (particularly the Malay Archipelago)[68] and Central Asia (particularly in Uzbekistan[69] and Tajikistan).[70]

Some Hindi movies also became big successes in the People's Republic of China during the 1940s and 1950s. The most popular Hindi films in China were Dr. Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani (1946), Awaara (1951) and Two Acres of Land (1953). Raj Kapoor was a famous movie star in China, and the song "Awara Hoon" ("I am a Tramp") was popular in the country. Since then, Hindi films significantly declined in popularity in China, until the Academy Award nominated Lagaan (2001) became the first Indian film to have a nation-wide release there in decades.[71] The Chinese filmmaker He Ping was impressed by Lagaan, especially its soundtrack, and thus hired the film's music composer A. R. Rahman to score the soundtrack for his film Warriors of Heaven and Earth (2003).[72] Several older Hindi films also have a cult following in Japan, particularly the films directed by the late Guru Dutt.[73]

Africa

Historically, Hindi films have been distributed to some parts of Africa, largely by Lebanese businessmen. Mother India (1957), for example, continued to be played in Nigeria decades after its release. Indian movies have also gained ground so as to alter the style of Hausa fashions, songs have also been copied by Hausa singers and stories have influenced the writings of Nigerian novelists. Stickers of Indian films and stars decorate taxis and buses in Northern Nigeria, while posters of Indian films adorn the walls of tailor shops and mechanics' garages in the country. Unlike in Europe and North America where Indian films largely cater to the expatriate Indian market yearning to keep in touch with their homeland, in West Africa, as in many other parts of the world, such movies rose in popularity despite the lack of a significant Indian audience, where movies are about an alien culture, based on a religion wholly different, and, for the most part, a language that is unintelligble to the viewers. One such explanation for this lied in the similarities between the two cultures. Clothing is largely similar, where men often wear long kurtas similar to the Hausa Babba riga and kaftan. Other similarities include wearing turbans; the presence of animals in markets; porters carrying large bundles, chewing sugar cane; youths riding Bajaj motor scooters; wedding celebrations, and so forth. With the strict Muslim culture, Indian movies were said to show "respect" toward women, where Hollywood movies were seen to have "no shame". In Indian movies women were modestly dressed, men and women rarely kiss, and there is no nudity, thus Indian movies are said to "have culture" that Hollywood films lack. The latter choice was a failure because "they don't base themselves on the problems of the people," where the former is based socialist values and on the reality of developing countries emerging from years of colonialism. Indian movies also allowed for a new youth culture to follow without such ideological baggage as "becoming western."[58] Bollywood is also popular among Somalis and the Somali diaspora, where the emerging Islamic Courts Union found a bete noire.[74] Chad and Ethiopia have also shown an interest in the movies.[75]

Several Bollywood personalities have avenued to the continent for both shooting movies and off-camera projects. The film Padmashree Laloo Prasad Yadav (2005) was one of many movies shot in South Africa. Dil Jo Bhi Kahey (2005) was shot almost entirely in Mauritius, which has a large ethnically Indian population.

Ominously, however, the popularity of old Bollywood versus a new, changing Bollywood seems to be diminishing the popularity on the continent. The changing style of Bollywood has begun to question such an acceptance. The new era features more sexually explicit and violent films. Nigerian viewers, for example, commented that older films of the 1950s and 1960s had culture to the newer, more westernized picturizations.[58] The old days of India avidly "advocating decolonization ... and India's policy was wholly influenced by his missionary zeal to end racial domination and discrimination in the African territories" were replaced by newer realities.[76] The emergence of Nollywood, Africa's local movie industry has also contributed to the declining popularity of Bollywood films. A greater globalised world worked in tandem with the sexualisation of Indian films so as to become more like American films, thus negating the preferred values of an old Bollywood and diminishing Indian soft power.

Russia and Eastern Europe

Bollywood films are particularly popular in the former Soviet Union. Bollywood films have been dubbed into Russian, and shown in prominent theatres such as Mosfilm and Lenfilm.

Ashok Sharma, Indian Ambassador to Suriname, who has served three times in the Commonwealth of Independent States region during his diplomatic career said:

The popularity of Bollywood in the CIS dates back to the Soviet days when the films from Hollywood and other Western countries were banned in the Soviet Union. As there was no means of other cheap entertainment, the films from Bollywood provided the Soviets a cheap source of entertainment as they were supposed to be non-controversial and non-political. In addition, the Soviet Union was recovering from the onslaught of the Second World War. The films from India, which were also recovering from the disaster of partition and the struggle for freedom from colonial rule, were found to be a good source of providing hope with entertainment to the struggling masses. The aspirations and needs of the people of both countries matched to a great extent. These films were dubbed in Russian and shown in theatres throughout the Soviet Union. The films from Bollywood also strengthened family values, which was a big factor for their popularity with the government authorities in the Soviet Union.[77]

The film Mera Naam Joker (1970), sought to cater to such an appeal and the popularity of Raj Kapoor in Russia, when it recruited Russian actress Kseniya Ryabinkina for the movie. In the contemporary era, Lucky: No Time for Love was shot entirely in Russia. After the collapse of the Soviet film distribution system, Hollywood occupied the void created in the Russian film market. This made things difficult for Bollywood as it was losing market share to Hollywood. However, Russian newspapers report that there is a renewed interest in Bollywood among young Russians.[78]

Western Europe and the Americas

Bollywood has experienced a marked growth in revenue in North American markets, and is particularly popular amongst the South Asian communities of such large cities as Chicago, Toronto and New York City.[29] Yash Raj Films, one of India's largest production houses and distributors, reported in September 2005 that Bollywood films in the United States earn around $100 million a year through theater screenings, video sales and the sale of movie soundtracks.[29] In other words, films from India do more business in the United States than films from any other non-English speaking country.[29] Numerous films in the mid-1990s and onwards have been largely, or entirely, shot in New York, Los Angeles, Vancouver and Toronto. Bollywood's immersion in the traditional Hollywood domain was further tied with such films as The Guru (2002) and Marigold: An Adventure in India (2007) trying to popularise the Bollywood-theme for Hollywood.

The awareness of Hindi cinema is however more spread in the United Kingdom,[79] where they frequently enter the UK top ten. Many films, such as Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (2001) have been set in London. Bollywood is also appreciated in Germany, France, and the Scandinavian countries. Various Bollywood movies are dubbed in German and shown on the German television channel RTL II on a regular basis.[80] A considerable number of Hindi movies has been shot in Western Europe as well, particularly in Switzerland, starting with Dilwale Dulhania le Jayenge.

Bollywood's popularity, however, is not greatly matched in the non-English speaking countries of South America, though Bollywood culture and dance is recognised. In 2006, Dhoom 2 became the first Bollywood film to be shot in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.[81] The feeling was reciprocated as Latin America's largest theater chain, Mexico's Cinepolis, was considering expanding its domains outside the Spanish-speaking areas of the continent as it appeared to be bound for Bollywood.[82]

Oceania

Bollywood is not as successful in the Oceanic countries and Pacific Islands such as New Guinea. However, it ranks second to Hollywood in countries such as Fiji, with its large Indian minority, Australia and New Zealand.[83]

Australia is one of the countries where there is a large South Asian Diaspora. Bollywood is popular amongst non-Asians in the country as well.[83] Since 1997 the country has provided a backdrop for an increasing number of Bollywood films.[83] Indian filmmakers have been attracted to Australia's diverse locations and landscapes, and initially used it as the setting for song-and-dance sequences, which demonstrated the contrast between the values.[83] However, nowadays, Australian locations are becoming more important to the plot of Bollywood films.[83] Hindi films shot in Australia usually incorporate aspects of Australian lifestyle. The Yash Raj Film Salaam Namaste (2005) became the first Indian film to be shot entirely in Australia and was the most successful Bollywood film of 2005 in the country.[84] This was followed by Heyy Babyy (2007) Chak De! India (2007) and Singh Is Kinng (2008) which turned out to be box office successes.[83] Following the release of Salaam Namaste, on a visit to India the then Prime Minister John Howard also sought, having seen the film, to have more Indian movies shooting in the country to boost tourism, where the Bollywood and cricket nexus, was further tightened with Steve Waugh's appointment as tourism ambassador to India.[85] Australian actress Tania Zaetta, who co-starred in Salaam Namaste, among other Bollywood films, expressed her keenness to expand her career in Bollywood.[86]

Plagiarism

Constrained by rushed production schedules and small budgets, certain Bollywood writers and musicians have been known to resort to plagiarism. They copy ideas, plot lines, tunes or riffs from sources close at hand from other Indian films or far away (including Hollywood and other Asian films). This has lead to criticism towards the film industry.[87]

In past times, this could be done with impunity. Copyright enforcement was lax in India and few actors or directors ever saw an official contract.[88] The Hindi film industry was not widely known to non-Indian audiences (excluding the Soviet states), who would not even be aware that their material was being copied. Audiences may also not have been aware of the plagiarism since many audiences in India were unfamiliar with foreign films and music. While copyright enforcement in India is still somewhat lenient, Bollywood and other film industries are much more aware of each other now and Indian audiences are more familiar with foreign movies and music. Organizations like the India EU Film Initiative seek to foster a community between film makers and industry professionel between India and the EU.[87]

One of the main problems in curbing plagiarism in Bollywood is due to the fact that producers in a competitive market, where gross income is important, often play a safer option by remaking popular Hollywood films in an Indian context. Screenwriters generally produce original scripts, but due to financial uncertainty and insecurity over the success of a film many were rejected.[87] Screenwriters themselves have been criticised for lack of creativity which happened due to tight schedules and restricted funds in the industry to employ better screenwriters.[89] Certain filmmakers see plagiarism in Bollywood as an intergral part of globalisation where American and western cultures are firmly embedding themselves into Indian culture, which is manifested, amongst other mediums, in Bollywood films.[89] Vikram Bhatt, director of films such as Raaz, a remake of What Lies Beneath, and Kasoor, a remake of Jagged Edge, has spoken about the strong influence of American culture and desire to produce box office hits based along the same lines in Bollywood, "Financially, I would be more secure knowing that a particular piece of work has already done well at the box office. Copying is endemic everywhere in India. Our TV shows are adaptations of American programmes. We want their films, their cars, their planes, their diet cokes and also their attitude. The American way of life is creeping into our culture."[89] Mahesh Bhatt has said ,"If you hide the source, you're a genius. There's no such thing as originality in the creative sphere".[89]