COVID-19 vaccine

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

A COVID‑19 vaccine is a vaccine intended to provide acquired immunity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2), the virus causing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19). Prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, there was an established body of knowledge about the structure and function of coronaviruses causing diseases like severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), which enabled accelerated development of various vaccine technologies during early 2020.[1] On 10 January 2020, the SARS-CoV-2 genetic sequence data was shared through GISAID, and by 19 March, the global pharmaceutical industry announced a major commitment to address COVID-19.[2]

In Phase III trials, several COVID‑19 vaccines have demonstrated efficacy as high as 95% in preventing symptomatic COVID‑19 infections. As of March 2021[update], 12 vaccines were authorized by at least one national regulatory authority for public use: two RNA vaccines (the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine and the Moderna vaccine), four conventional inactivated vaccines (BBIBP-CorV, CoronaVac, Covaxin, and CoviVac), four viral vector vaccines (Sputnik V, the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine, Convidecia, and the Johnson & Johnson vaccine), and two protein subunit vaccines (EpiVacCorona and RBD-Dimer).[3] In total, as of March 2021[update], 308 vaccine candidates were in various stages of development, with 73 in clinical research, including 24 in Phase I trials, 33 in Phase I–II trials, and 16 in Phase III development.[3]

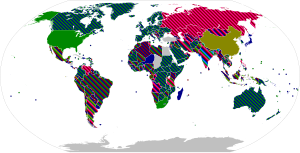

Many countries have implemented phased distribution plans that prioritize those at highest risk of complications, such as the elderly, and those at high risk of exposure and transmission, such as healthcare workers.[4] As of 30 March 2021[update], 574.25 million doses of COVID‑19 vaccine have been administered worldwide based on official reports from national health agencies.[5] AstraZeneca-Oxford anticipates producing 3 billion doses in 2021, Pfizer-BioNTech 1.3 billion doses, and Sputnik V, Sinopharm, Sinovac, and Johnson & Johnson 1 billion doses each. Moderna targets producing 600 million doses and Convidecia 500 million doses in 2021.[6][7] By December 2020, more than 10 billion vaccine doses had been preordered by countries,[8] with about half of the doses purchased by high-income countries comprising 14% of the world's population.[9]

Background

Prior to COVID‑19, a vaccine for an infectious disease had never been produced in less than several years—and no vaccine existed for preventing a coronavirus infection in humans.[10] However, vaccines have been produced against several animal diseases caused by coronaviruses, including (as of 2003) infectious bronchitis virus in birds, canine coronavirus, and feline coronavirus.[11] Previous projects to develop vaccines for viruses in the family Coronaviridae that affect humans have been aimed at severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Vaccines against SARS[12] and MERS[13] have been tested in non-human animals.

According to studies published in 2005 and 2006, the identification and development of novel vaccines and medicines to treat SARS was a priority for governments and public health agencies around the world at that time.[14][15][16] As of 2020, there is no cure or protective vaccine proven to be safe and effective against SARS in humans.[17][18] There is also no proven vaccine against MERS.[19] When MERS became prevalent, it was believed that existing SARS research may provide a useful template for developing vaccines and therapeutics against a MERS-CoV infection.[17][20] As of March 2020, there was one (DNA based) MERS vaccine which completed Phase I clinical trials in humans[21] and three others in progress, all being viral-vectored vaccines: two adenoviral-vectored (ChAdOx1-MERS, BVRS-GamVac) and one MVA-vectored (MVA-MERS-S).[22]

Planning and development

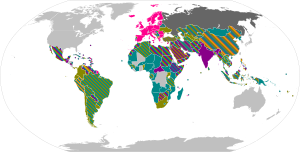

Since January 2020, vaccine development has been expedited via unprecedented collaboration in the multinational pharmaceutical industry and between governments.[23] According to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the geographic distribution of COVID‑19 vaccine development puts North American entities having about 40% of the activity compared to 30% in Asia and Australia, 26% in Europe, and a few projects in South America and Africa.[23][24]

Multiple steps along the entire development path are evaluated, including:[10][25]

- the level of acceptable toxicity of the vaccine (its safety),

- targeting vulnerable populations,

- the need for vaccine efficacy breakthroughs,

- the duration of vaccination protection,

- special delivery systems (such as oral or nasal, rather than by injection),

- dose regimen,

- stability and storage characteristics,

- emergency use authorization before formal licensing,

- optimal manufacturing for scaling to billions of doses, and

- dissemination of the licensed vaccine.

Challenges

There have been several unique challenges with COVID-19 vaccine development.

The urgency to create a vaccine for COVID‑19 led to compressed schedules that shortened the standard vaccine development timeline, in some cases combining clinical trial steps over months, a process typically conducted sequentially over years.[26]

Timelines for conducting clinical research – normally a sequential process requiring years – are being compressed into safety, efficacy, and dosing trials running simultaneously over months, potentially compromising safety assurance.[26][27] As an example, Chinese vaccine developers and the government Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention began their efforts in January 2020,[28] and by March were pursuing numerous candidates on short timelines, with the goal to showcase Chinese technology strengths over those of the United States, and to reassure the Chinese people about the quality of vaccines produced in China.[26][29]

The rapid development and urgency of producing a vaccine for the COVID‑19 pandemic may increase the risks and failure rate of delivering a safe, effective vaccine.[24][30][31] Additionally, research at universities is obstructed by physical distancing and closing of laboratories.[32][33]

Vaccines must progress through several phases of clinical trials to test for safety, immunogenicity, effectiveness, dose levels and adverse effects of the candidate vaccine.[34][35] Vaccine developers have to invest resources internationally to find enough participants for Phase II–III clinical trials when the virus has proved to be a "moving target" of changing transmission rate across and within countries, forcing companies to compete for trial participants;[36] clinical trial organizers may encounter people unwilling to be vaccinated due to vaccine hesitancy[37] or disbelieving the science of the vaccine technology and its ability to prevent infection.[38] Even as new vaccines are developed during the COVID‑19 pandemic, licensure of COVID‑19 vaccine candidates requires submission of a full dossier of information on development and manufacturing quality.[39][40][41]

Organizations

Internationally, the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator is a G20 and World Health Organization (WHO) initiative announced in April 2020.[42][43] It is a cross-discipline support structure to enable partners to share resources and knowledge. It comprises four pillars, each managed by two to three collaborating partners: Vaccines (also called "COVAX"), Diagnostics, Therapeutics, and Health Systems Connector.[44] The WHO's April 2020 "R&D Blueprint (for the) novel Coronavirus" documented a "large, international, multi-site, individually randomized controlled clinical trial" to allow "the concurrent evaluation of the benefits and risks of each promising candidate vaccine within 3–6 months of it being made available for the trial." The WHO vaccine coalition will prioritize which vaccines should go into Phase II and III clinical trials, and determine harmonized Phase III protocols for all vaccines achieving the pivotal trial stage.[45]

National governments have also been involved in vaccine development. Canada announced funding for 96 research vaccine research projects at Canadian companies and universities, with plans to establish a "vaccine bank" that could be used if another coronavirus outbreak occurs,[46] and to support clinical trials and develop manufacturing and supply chains for vaccines.[47] China provided low-rate loans to a vaccine developer through its central bank and "quickly made land available for the company" to build production plants.[27] Three Chinese vaccine companies and research institutes are supported by the government for financing research, conducting clinical trials, and manufacturing.[48] Great Britain formed a COVID‑19 vaccine task force in April 2020 to stimulate local efforts for accelerated development of a vaccine through collaborations of industry, universities, and government agencies. It encompassed every phase of development from research to manufacturing.[49] In the United States, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), a federal agency funding disease-fighting technology, announced investments to support American COVID‑19 vaccine development and manufacture of the most promising candidates.[27][50] In May 2020, the government announced funding for a fast-track program called Operation Warp Speed.[51][52]

Large pharmaceutical companies with experience in making vaccines at scale, including Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), formed alliances with biotechnology companies, governments, and universities to accelerate progression to an effective vaccine.[27][26]

History

SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), the virus that causes COVID-19, was isolated in late 2019.[53] Its genetic sequence was published on 11 January 2020, triggering an urgent international response to prepare for an outbreak and hasten the development of a preventive COVID-19 vaccine.[54][55][56] Since 2020, vaccine development has been expedited via unprecedented collaboration in the multinational pharmaceutical industry and between governments.[57] By June 2020, tens of billions of dollars were invested by corporations, governments, international health organizations, and university research groups to develop dozens of vaccine candidates and prepare for global vaccination programs to immunize against COVID‑19 infection.[55][58][59][60] According to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the geographic distribution of COVID‑19 vaccine development shows North American entities to have about 40% of the activity, compared to 30% in Asia and Australia, 26% in Europe, and a few projects in South America and Africa.[54][57]

In February 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) said it did not expect a vaccine against SARS‑CoV‑2 to become available in less than 18 months.[61] Virologist Paul Offit commented that, in hindsight, the development of a safe and effective vaccine within 11 months was a remarkable feat.[62] The rapidly growing infection rate of COVID‑19 worldwide during 2020 stimulated international alliances and government efforts to urgently organize resources to make multiple vaccines on shortened timelines,[63] with four vaccine candidates entering human evaluation in March (see COVID-19 vaccine § Trial and authorization status).[54][64]

On 24 June 2020, China approved the CanSino vaccine for limited use in the military and two inactivated virus vaccines for emergency use in high-risk occupations.[65] On 11 August 2020, Russia announced the approval of its Sputnik V vaccine for emergency use, though one month later only small amounts of the vaccine had been distributed for use outside of the phase 3 trial.[66]

The Pfizer–BioNTech partnership submitted an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) request to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the mRNA vaccine BNT162b2 (active ingredient tozinameran) on 20 November 2020.[67][68] On 2 December 2020, the United Kingdom's Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) gave temporary regulatory approval for the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine,[69][70] becoming the first country to approve the vaccine and the first country in the Western world to approve the use of any COVID‑19 vaccine.[71][72][73] As of 21 December 2020, many countries and the European Union[74] had authorized or approved the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID‑19 vaccine. Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates granted emergency marketing authorization for the Sinopharm BIBP vaccine.[75][76] On 11 December 2020, the FDA granted an EUA for the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID‑19 vaccine.[77] A week later, they granted an EUA for mRNA-1273 (active ingredient elasomeran), the Moderna vaccine.[78][79][80][81]

On 31 March 2021, the Russian government announced that they had registered the first COVID‑19 vaccine for animals.[82] Named Carnivac-Cov, it is an inactivated vaccine for carnivorous animals, including pets, aimed at preventing mutations that occur during the interspecies transmission of SARS-CoV-2.[83]

In October 2022, China began administering an oral vaccine developed by CanSino Biologics using its adenovirus model.[84]

Despite the availability of mRNA and viral vector vaccines, worldwide vaccine equity has not been achieved. The ongoing development and use of whole inactivated virus (WIV) and protein-based vaccines has been recommended, especially for use in developing countries, to dampen further waves of the pandemic.[85][86]Vaccine types

As of January 2021, nine different technology platforms – with the technology of numerous candidates remaining undefined – are under research and development to create an effective vaccine against COVID‑19.[3][23] Most of the platforms of vaccine candidates in clinical trials are focused on the coronavirus spike protein and its variants as the primary antigen of COVID‑19 infection.[23] Platforms being developed in 2020 involved nucleic acid technologies (nucleoside-modified messenger RNA and DNA), non-replicating viral vectors, peptides, recombinant proteins, live attenuated viruses, and inactivated viruses.[10][23][24][30]

Many vaccine technologies being developed for COVID‑19 are not like vaccines already in use to prevent influenza, but rather are using "next-generation" strategies for precision on COVID‑19 infection mechanisms.[23][24][30] Vaccine platforms in development may improve flexibility for antigen manipulation and effectiveness for targeting mechanisms of COVID‑19 infection in susceptible population subgroups, such as healthcare workers, the elderly, children, pregnant women, and people with existing weakened immune systems.[23][24]

RNA vaccines

An RNA vaccine contains RNA which, when introduced into a tissue, acts as messenger RNA (mRNA) to cause the cells to build the foreign protein and stimulate an adaptive immune response which teaches the body how to identify and destroy the corresponding pathogen or cancer cells. RNA vaccines often, but not always, use nucleoside-modified messenger RNA. The delivery of mRNA is achieved by a coformulation of the molecule into lipid nanoparticles which protect the RNA strands and help their absorption into the cells.[87][88][89][90]

RNA vaccines were the first COVID-19 vaccines to be authorized in the United States and the European Union.[91][92] As of January 2021[update], authorized vaccines of this type are the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID‑19 vaccine

Severe allergic reactions are rare. In December 2020, 1,893,360 first doses of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID‑19 vaccine administration resulted in 175 cases of severe allergic reaction, of which 21 were anaphylaxis.[99] For 4,041,396 Moderna COVID-19 vaccine dose administrations in December 2020 and January 2021, only 10 cases of anaphylaxis were reported.[99] The lipid nanoparticles were most likely responsible for the allergic reactions.[99]

Adenovirus vector vaccines

These vaccines are examples of non-replicating viral vectors, using an adenovirus shell containing DNA that encodes a SARS‑CoV‑2 protein.[100] The viral vector-based vaccines against COVID-19 are non-replicating, meaning that they do not make new virus particles, but rather produce only the antigen which elicits a systemic immune response.[100]

As of January 2021, authorized vaccines of this type are the British Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine,

Convidecia and Johnson & Johnson's vaccines are both one-shot vaccines which offer less complicated logistics; and can be stored under ordinary refrigeration for several months.[107][108]

Sputnik V uses Ad26 for the first dose the same as Johnson & Johnson's vaccine and Ad5 for the 2nd dose the same as Convidecia with similar single dose effectiveness and full trial taking place on single dose effectiveness.

Inactivated virus vaccines

Inactivated vaccines consist of virus particles that have been grown in culture and then are killed using a method such as heat or formaldehyde to lose disease producing capacity, while still stimulating an immune response.[109]

As of January 2021, authorized vaccines of this type are the Chinese CoronaVac,[110][111][112] BBIBP-CorV

Subunit vaccines

Subunit vaccines present one or more antigens without introducing whole pathogen particles. The antigens involved are often protein subunits, but can be any molecule that is a fragment of the pathogen.[117]

As of January 2021, the only authorized vaccine of this type is the peptide vaccine EpiVacCorona.

Other types

Additional types of vaccines that are in clinical trials include multiple DNA plasmid vaccines,[122]

Scientists investigated whether existing vaccines for unrelated conditions could prime the immune system and lessen the severity of COVID‑19 infection.[131] There is experimental evidence that the BCG vaccine for tuberculosis has non-specific effects on the immune system, but no evidence that this vaccine is effective against COVID‑19.[132]

Efficacy

The effectiveness of a new vaccine is defined by its efficacy during clinical trials.[134] The efficacy is the risk of getting the disease by vaccinated participants in the trial compared with the risk of getting the disease by unvaccinated participants.[134] An efficacy of 0% means that the vaccine does not work (identical to placebo). An efficacy of 50% means that there are half as many cases of infection as in unvaccinated individuals.

It is not straightforward to compare the efficacies of the different vaccines because the trials were run with different populations, geographies, and variants of the virus.[135] In the case of COVID‑19, a vaccine efficacy of 67% may be enough to slow the pandemic, but this assumes that the vaccine confers sterilizing immunity, which is necessary to prevent transmission. Vaccine efficacy reflects disease prevention, a poor indicator of transmissibility of SARS‑CoV‑2 since asymptomatic people can be highly infectious.[136] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) set a cutoff of 50% as the efficacy required to approve a COVID‑19 vaccine.[137][138] Aiming for a realistic population vaccination coverage rate of 75%, and depending on the actual basic reproduction number, the necessary effectiveness of a COVID-19 vaccine is expected to be at least 70% to prevent an epidemic and at least 80% to extinguish it without further measures, such as social distancing.[139]

In efficacy calculations, symptomatic COVID-19 is generally defined as having both a positive PCR test and at least one or two of a defined list of COVID-19 symptoms, although exact specifications varying between trials. The trial location also affects the reported efficacy because different countries have different prevalences of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Ranges below are 95% confidence intervals unless indicated otherwise, and all values are for all participants regardless of age. Efficacy against severe COVID-19 is the most important, since hospitalizations and deaths are a public health burden whose prevention is a priority.[140] Authorized and approved vaccines have shown the following efficacies:

| Vaccine | Efficacy by severity of COVID-19 | Trial location | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild or moderate[A] | Severe without hospitalization or death[B] | Severe with hospitalization or death[C] | |||

| Moderna vaccine | 94% (89–97%)[D] | 100%[E] | 100%[E] | United States | [141] |

| Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine | 95% (90–98%) | Not reported | Not reported | Multinational | [142] |

| Sputnik V | 92% (86–95%) | 100% (94–100%) | 100% | Russia | [143] |

| Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine | 81% (60–91%)[F] | 100% (97.5% CI, 72–100%) | 100% | Multinational | [144] |

| 76% (68–82%)[G] | 100% | 100% | United States | [145] | |

| Novavax vaccine | 89% (75–95%) | 100%[H] | 100%[H] | United Kingdom | [146][147] |

| 60% (20–80%) | 100%[H] | 100%[H] | South Africa | ||

| BBIBP-CorV | 79% | 100%[148] | 100%[148] | Multinational | [149][unreliable medical source?] |

| CoronaVac | 78% | 100% | 100% | Brazil | [150][151][152][unreliable medical source?] |

| Johnson & Johnson vaccine | 66% (55–75%)[I][J] | 85% (54–97%)[J] | 100%[J] | Multinational | [153] |

| 72% (58–82%)[I][J] | 86% (−9 to 100%)[J] | 100%[J] | United States | ||

| 68% (49–81%)[I][J] | 88% (8–100%)[J] | 100%[J] | Brazil | ||

| 64% (41–79%)[I][J] | 82% (46–95%)[J] | 100%[J] | South Africa | ||

| Covaxin | 81% | Not reported | Not reported | India | [154][155][unreliable medical source?] |

| Convidecia | 66% | 91% | Not reported | Multinational | [156][unreliable medical source?] |

- ^ Mild symptoms: fever, dry cough, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia, sore throat, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, headache, anosmia, ageusia, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, conjunctivitis, skin rash, chills, dizziness. Moderate symptoms: mild pneumonia.

- ^ Severe symptoms without hospitalization or death for an individual, are any one of the following severe respiratory symptoms measured at rest on any time during the course of observation (on top of having either pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, dyspnea, hypoxia, persistent chest pain, anorexia, confusion, fever above 38 °C (100 °F)), that however were not persistent/severe enough to cause hospitalization or death: Any respiratory rate ≥30 breaths/minute, heart rate ≥125 beats/minute, oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≤93% on room air at sea level, or partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) <300 mmHg.

- ^ Severe symptoms causing hospitalization or death, are those requiring treatment at hospitals or results in deaths: dyspnea, hypoxia, persistent chest pain, anorexia, confusion, fever above 38 °C (100 °F), respiratory failure, kidney failure, multiorgan dysfunction, sepsis, shock.

- ^ Mild/Moderate COVID-19 symptoms observed in the Moderna vaccine trials, were only counted as such for vaccinated individuals if they began more than 14 days after their second dose, and required presence of a positive RT-PCR test result along with at least two systemic symptoms (fever above 38ºC, chills, myalgia, headache, sore throat, new olfactory and taste disorder) or just one respiratory symptom (cough, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, or clinical or radiographical evidence of pneumonia).

- ^ a b Severe COVID-19 symptoms observed in the Moderna vaccine trials, were defined as symptoms having met the criteria for mild/moderate symptoms plus any of the following observations: Clinical signs indicative of severe systemic illness, respiratory rate ≥30 per minute, heart rate ≥125 beats per minute, SpO2 ≤93% on room air at sea level or PaO2/FIO2 <300 mm Hg; or respiratory failure or ARDS, (defined as needing high-flow oxygen, non-invasive or mechanical ventilation, or ECMO), evidence of shock (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, diastolic BP <60 mmHg or requiring vasopressors); or significant acute renal, hepatic, or neurologic dysfunction; or admission to an intensive care unit or death. No severe cases were detected for vaccinated individuals in the trials, compared with 30 severe cases reported in the placebo group (incidence rate 9.1 per 1000 person-years).

- ^ With 12 weeks or more of interval between doses. For an interval of less than 6 weeks, the trial found an efficacy 55% (33–70%).

- ^ With a 4 week interval between doses. Efficacy is "at preventing symptomatic COVID-19."

- ^ a b c d No cases detected in trial.

- ^ a b c d Moderate cases.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Efficacy reported 28 days post-vaccination for the Johnson & Johnson single shot vaccine. A lower efficacy was found for the vaccinated individuals 14 days post-vaccination.

Real-world studies of vaccine effectiveness

The real-world studies of vaccine effectiveness, measure to which extend a certain vaccine have succeded preventing COVID-19 infection, symptoms, hospitalization and deaths for the vaccinated individuals in a large population.

- In Israel, among 715,425 individuals vaccinated by the Moderna/Pfizer vaccine during December 20 to January 28, it was observed for the period starting seven days after the second shot, that only 317 people (0.04%) became sick with mild/moderate Covid-19 symptoms and only 16 people (0.002%) were hospitalized.[157]

- Pfizer and Moderna Covid-19 vaccines provide highly effective protection, according to a report from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Under real-world conditions, mRNA vaccine effectiveness of full immunization (≥14 days after second dose) was 90% against SARS-CoV-2 infections regardless of symptom status; vaccine effectiveness of partial immunization (≥14 days after first dose but before second dose) was 80%.[158]

Variants

The emergence of a SARS-CoV-2 variant that is moderately or fully resistant to the antibody response elicited by the current generation of COVID-19 vaccines may require modification of the vaccines.[159] Trials indicate many vaccines developed for the initial strain have lower efficacy for some variants against symptomatic COVID-19.[160] As of February 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration believed that all FDA authorized vaccines remained effective in protecting against circulating strains of SARS-CoV-2.[159]

B.1.1.7 variant

In December 2020, a new SARS‑CoV‑2 variant, B.1.1.7, was identified in the UK.[161] Early results suggest protection to the UK variant from the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines.[162][163] One study indicated that the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine had an efficacy of 42–89% against the B.1.1.7 variant, versus 71–91% against non-B.1.1.7 variants.[164] Preliminary data from a clinical trial indicated that the Novavax vaccine was ~96% effective for symptoms against the original variant, ~86% against B.1.1.7, and ~60% against the "South African" B.1.351 variant.[165]

501.V2 variant

Moderna has launched a trial of a vaccine to tackle the South African 501.V2 variant (also known as B.1.351).[166] On 17 February 2021, Pfizer announced neutralization activity was reduced by two-thirds for the 501.V2 variant, while stating no claims about the efficacy of the vaccine in preventing illness for this variant could yet be made.[167] Decreased neutralizing activity of sera from patients vaccinated with Moderna and Pfizer vaccines against B.1.351 was latter confirmed by several studies.[163][168]

In January, Johnson & Johnson, which held trials for its Ad26.COV2.S vaccine in South Africa, reported the level of protection against moderate to severe COVID-19 infection was 72% in the United States and 57% in South Africa.[169]

On 6 February 2021, the Financial Times reported that provisional trial data from a study undertaken by South Africa's University of the Witwatersrand in conjunction with Oxford University demonstrated reduced efficacy of the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine against the 501.V2 variant.[170] The study found that in a sample size of 2,000 the AZD1222 vaccine afforded only "minimal protection" in all but the most severe cases of COVID-19.[171] On 7 February 2021, the Minister for Health for South Africa suspended the planned deployment of around 1 million doses of the vaccine whilst they examine the data and await advice on how to proceed.[172][173]

P1 variant

The P1 variant (also known as 20J/501Y.V3), initially identified in Brazil, seems to partially escape vaccination with the Pfizer/BioNtech vaccine.[168]

Trial and authorization status

Phase I trials test primarily for safety and preliminary dosing in a few dozen healthy subjects, while Phase II trials – following success in Phase I – evaluate immunogenicity, dose levels (efficacy based on biomarkers) and adverse effects of the candidate vaccine, typically in hundreds of people.[34][35] A Phase I–II trial consists of preliminary safety and immunogenicity testing, is typically randomized, placebo-controlled, while determining more precise, effective doses.[35] Phase III trials typically involve more participants at multiple sites, include a control group, and test effectiveness of the vaccine to prevent the disease (an "interventional" or "pivotal" trial), while monitoring for adverse effects at the optimal dose.[34][35] Definition of vaccine safety, efficacy, and clinical endpoints in a Phase III trial may vary between the trials of different companies, such as defining the degree of side effects, infection or amount of transmission, and whether the vaccine prevents moderate or severe COVID‑19 infection.[36][174][175]

A clinical trial design in progress may be modified as an "adaptive design" if accumulating data in the trial provide early insights about positive or negative efficacy of the treatment.[176][177] Adaptive designs within ongoing Phase II–III clinical trials on candidate vaccines may shorten trial durations and use fewer subjects, possibly expediting decisions for early termination or success, avoiding duplication of research efforts, and enhancing coordination of design changes for the Solidarity trial across its international locations.[176][178]

List of authorized and approved vaccines

National regulatory authorities have granted emergency use authorizations for twelve vaccines. Six of those have been approved for emergency or full use by at least one WHO-recognized stringent regulatory authorities.

|

|

| Vaccine, developers/sponsors | Country of origin | Type (technology) | Doses, interval | Storage temperature | Current phase (participants) | Authorization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine (Gam-COVID-Vac) Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology |

Russia | Adenovirus vector (recombinant Ad5 and Ad26) |

2 doses 3 weeks |

≤-18 °C (freezer) |

Phase III (40,000) Randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled to evaluate efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety.[182] Interim analysis from the trial was published in The Lancet, indicating 91.6% efficacy without unusual side effects.[143] Aug 2020 – May 2021, Russia, Belarus,[183] India,[184][185] Venezuela,[186][187] UAE[188] |

Template:CovidVacNum |

| Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine (Vaxzevria, Covishield) University of Oxford, AstraZeneca, CEPI |

United Kingdom, Sweden | Adenovirus vector (ChAdOx1) |

2 doses 4–12 weeks |

2–8 °C |

Phase III (30,000) Interventional; randomized, placebo-controlled study for efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity.[195] Overall efficacy of 76% after the first dose and 81% after a second dose taken 12 weeks or more after the first.[144] May 2020 – Aug 2021, Brazil (5,000),[196] United Kingdom, India[197] |

Template:CovidVacNum |

| Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (Comirnaty) BioNTech, Pfizer |

United States, Germany | RNA (modRNA in lipid nanoparticles) |

2 doses 3–4 weeks |

-70±10 °C (ULT) |

Phase III (43,448) Randomized, placebo-controlled. Positive results from an interim analysis were announced on 18 November 2020[203] and published on 10 December 2020 reporting an overall efficacy of 95%.[204][205] Jul – Nov 2020,[206][134] Germany, United States |

Template:CovidVacNum |

| BBIBP-CorV Sinopharm: Beijing Institute of Biological Products, Wuhan Institute of Biological Products |

China | Inactivated SARS‑CoV‑2 (vero cells) |

2 doses 3–4 weeks |

2–8 °C |

Phase III (48,000) Randomized, double-blind, parallel placebo-controlled, to evaluate safety and protective efficacy. Sinopharm's internal analysis indicated a 79% efficacy.[209] Jul 2020 – Jul 2021, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Jordan,[210] Argentina,[211] Morocco,[212] Peru[213] |

Template:CovidVacNum |

| CoronaVac[110][111][112] Sinovac |

China | Inactivated SARS‑CoV‑2 (vero cells) |

2 doses 2 weeks |

2–8 °C |

Phase III (33,620) Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled to evaluate efficacy and safety. Final Phase III results from Turkey showed an efficacy of 83.5%.[216] Additional results were announced by Indonesia with an efficacy of 65.3%.[217] Brazil announced results showing 50.4% effective at preventing symptomatic infections, 78% effective in preventing mild cases, and 100% effective in preventing severe cases.[218] July 2020 – Oct 2021, Brazil (15,000);[219] Aug 2020 – January 2021, Indonesia (1,620); Chile (3,000);[220] Turkey (13,000)[221] |

Template:CovidVacNum |

| Moderna COVID-19 vaccine Moderna, NIAID, BARDA, CEPI |

United States | RNA (modRNA in lipid nanoparticles) |

2 doses 4 weeks |

-20±5 °C (freezer) |

Phase III (30,000) Interventional; randomized, placebo-controlled study for efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity. Positive results from an interim analysis were announced on 15 November 2020[225] and published on 30 December 2020 reporting an overall efficacy of 94%.[226] Jul 2020 – Oct 2022, United States |

Template:CovidVacNum |

| Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine[105][106] Janssen Vaccines (Johnson & Johnson), BIDMC |

United States, Netherlands | Adenovirus vector (recombinant Ad26) |

1 dose[228] | 2–8 °C[228] | Phase III (40,000) Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled Positive results from an interim analysis were announced on 29 January 2021. J&J reports an efficacy of 66% against mild and moderate symptoms, and 85% against severe symptoms. Further, the mild and moderate efficacy ranged from 64% in South Africa to 72% in the United States.[229][153] Jul 2020 – 2023, United States, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, South Africa, Ukraine |

Template:CovidVacNum |

| Ad5-nCoV (Convidecia) CanSino Biologics, Beijing Institute of Biotechnology of the Academy of Military Medical Sciences |

China | Adenovirus vector (recombinant Ad5) |

1 dose[156] | 2–8 °C[156] | Phase III (40,000) Global multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled to evaluate efficacy, safety and immunogenicity. In February 2021, interim analysis from global trials showed an efficacy of 65.7% against moderate cases of COVID-19 and 90.98% efficacy against severe cases.[156] Mar–Dec 2020, China; Sep 2020 – Dec 2021, Pakistan; Sep – Nov 2020, Russia,[231] China, Argentina, Chile;[232] Mexico;[233] Pakistan;[234] Saudi Arabia[235][236] |

Template:CovidVacNum |

| BBV152 (Covaxin) Bharat Biotech, Indian Council of Medical Research |

India | Inactivated SARS‑CoV‑2 (vero cells) |

2 doses 4 weeks |

2–8 °C |

Phase III (25,800) Randomised, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled[239] The interim efficacy rate is 81% as per third phase trial.[240] All data from the animal, first, second phase trials have been made public through peer-reviewed journals.[241] Phase-3 trials had shown 81% efficacy.[242] Nov 2020 – Mar 2021, India. |

Template:CovidVacNum |

| EpiVacCorona Vector Institute |

Russia | Subunit (peptide) |

2 doses 3 weeks |

2–8 °C |

Phase III (40,000) Randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled to evaluate efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety Nov 2020 – Dec 2021, Russia[245] |

Template:CovidVacNum |

| ZF2001 (RBD-Dimer)[3] Anhui Zhifei Longcom Biopharmaceutical Co. Ltd. |

China | Subunit (recombinant) | 3 doses 30 days |

Phase III (29,000) Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled[246] Dec 2020 – Apr 2022, China, Ecuador, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, Uzbekistan[248][249] |

Template:CovidVacNum | |

| CoviVac[250] The Chumakov Centre at the Russian Academy of Sciences |

Russia | Inactivated SARS‑CoV‑2 |

2 doses 2 weeks |

2–8 °C |

Phase III (3,000) Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled to evaluate efficacy and safety. |

Template:CovidVacNum |

Vaccine candidates in human trials

| Vaccine candidates, developers, and sponsors |

Country of origin | Type (technology) | Current phase (participants) design |

Completed phase[f] (participants) Immune response |

Pending authorization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novavax COVID-19 vaccine (Covovax) Novavax, CEPI |

United States | Subunit[256][257][258]/virus-like particle[259][260] (SARS‑CoV‑2 recombinant spike protein nanoparticle with adjuvant) | Phase III (45,000) Randomised, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled trial[261] Sep 2020 – Jan 2021, UK (15,000); December 2020 – Mar 2021, US, Mexico, (30,000);[262] India[263] |

Phase I–II (131) IgG and neutralizing antibody response with adjuvant after booster dose.[264] |

||

| CureVac COVID-19 vaccine (CVnCoV) CureVac, CEPI |

Germany | RNA (unmodified RNA)[273] | Phase III (39,020) Phase 2b/3 (36,500): Multicenter efficacy and safety trial in adults. Phase 3 (2,520): Randomized, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled. Nov 2020 – Jun 2021, Argentina, Belgium, Colombia, Dominican Republic, France, Germany, Mexico, Netherlands, Panama, Peru, Spain |

Phase I–II (944) Phase I (284): Partially blind, controlled, dose-escalation to evaluate safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity. Phase IIa (660):Partially observer-blind, multicenter, controlled, dose-confirmation. Jun 2020 – Oct 2021, Belgium (phase I), Germany (phase I), Panama (phase IIa), Peru (phase IIa) |

Emergency (1)

| |

| CIGB-66 (ABDALA) Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology |

Cuba | Subunit | Phase III (48,000) Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled. Mar – Jul 2021, Cuba |

Phase I–II (132) Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, factorial. Nov 2020 – May 2021, Cuba |

||

| SOBERANA 02 (FINLAY-FR-2) Instituto Finlay de Vacunas |

Cuba | Conjugate | Phase III (44,010) Multicenter, adaptive, parallel-group, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind Mar – Nov 2021, Cuba |

Phase I–II (950) Phase I (40): Non-randomized controlled trial. Masking: Open. Control group: Uncontrolled. Study design: Adaptive, sequential Phase II (910): Randomized controlled trial. Masking: Double Blind. Control group: Placebo. Study design: Parallel. Nov 2020 – Mar 2021, Cuba |

Emergency (1)

| |

| Sanofi–GSK COVID-19 vaccine (VAT00002) Sanofi Pasteur, GSK |

France, United Kingdom | Subunit | Phase III (34,520) Efficacy, Immunogenicity, and Safety of SARS-CoV-2 Recombinant Protein Vaccine with Adjuvant in Adults 18 Years of Age and Older. Dec 2020 – Apr 2022, Kenya |

Phase I–II (1,160) Phase I-IIa (440): Immunogenicity and Safety of SARS-CoV-2 Recombinant Protein Vaccine Formulations (With or Without Adjuvant) in Healthy Adults 18 Years of Age and Older.[286] Phase IIb (720): Immunogenicity and Safety of SARS-CoV-2 Recombinant Protein Vaccine With AS03 Adjuvant in Adults 18 Years of Age and Older.[287] Sep 2020 – Sep 2022, United States |

||

| Unnamed Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences |

China | Inactivated SARS‑CoV‑2 | Phase III (34,020) Randomized, double-blinded, single-center, placebo-controlled Jan – Sep 2021, Brazil, Malaysia |

Phase I–II (942) Randomized, double-blinded, single-center, placebo-controlled May – Sep 2020, Chengdu |

||

| QazCovid-in[294] Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems |

Kazakhstan | Inactivated SARS‑CoV‑2 | Phase III (3,000) Randomised, blind, placebo-controlled trial[295] Dec 2020 – Mar 2021, Kazakhstan [295] |

Phase I–II (244[296]) Sep – Nov 2020, Kazakhstan |

||

| ZyCoV-D Cadila Healthcare |

India | DNA (plasmid expressing SARS‑CoV‑2 S protein) | Phase III (26,000) Randomised, blind, placebo-controlled trial[298] Jan 2021 – ?, India[299] |

Phase I–II (1,000) Interventional; randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled[300][298] Jul 2020 – Jan 2021, India |

||

| CoVLP[301] Medicago, GSK |

Canada, United Kingdom | Virus-like particles[g] (recombinant, plant-based with AS03) | Phase II–III (30,918) Event-driven, randomized, observer blinded, placebo-controlled[303] Nov 2020 – Dec 2021, Canada |

Phase I (180) Neutralizing antibodies at day 42 after the first injection (day 21 after the second injection) were at levels 10x that of COVID-19 survivors. Jul 2020 – Sept 2021, Canada[304] |

Emergency (1)

| |

| SCB-2019 Clover Biopharmaceuticals,[308][309] GSK, CEPI |

China, United Kingdom | Subunit (Spike protein trimeric subunit with AS03) | Phase II–III (22,000) Randomized, double-blind, controlled Mar 2021 – Jul 2022, Belgium, Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Germany, Nepal, Panama, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa |

Phase I (150) Jun – Oct 2020, Perth |

||

| COVIran Barakat[310] Barakat Pharmaceutical Group, Shifa Pharmed Industrial Group |

Iran | Inactivated SARS‑CoV‑2 | Phase II–III (20,000) Randomized, double-blind, parallel arms, placebo-controlled.[311] Mar – May 2021, Iran |

Phase I (56) Randomized, double-blind, parallel arms, placebo-control.[312] Dec 2020 – Feb 2021, Iran |

||

| UB-612 United Biomedical,Inc, COVAXX, DASA |

Brazil, United States | Subunit | Phase II–III (11,170) Phase IIa (3,850): Placebo-controlled, Randomized, Observer-blind Study. Phase IIb-III (7,320): Randomized, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Placebo Controlled, Dose-Response. Jan 2021–Mar 2023, Taiwan |

Phase I (60) Open-label study Sep 2020–Jan 2021, Taiwan |

||

| GRAd-COV2 ReiThera, Lazzaro Spallanzani National Institute for Infectious Diseases |

Italy | Adenovirus vector (modified chimpanzee adenovirus vector, GRAd) | Phase II–III (10,300) Randomized, stratified, observer-blind, placebo-controlled. Mar–May 2021, Italy |

Phase I (90) Subjects (two groups: 18–55 and 65–85 years old) randomly receiving one of three escalating doses of GRAd-COV2 or a placebo, then monitored over a 24-week period. 93% of subjects who received GRAd-COV2 developed anti-bodies. Aug–Dec 2020, Rome |

||

| Unnamed Jiangsu Province Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, West China Hospital |

China | Subunit (recombinant with Sf9 cell) | Phase II (4,960) Phase IIa (960):Single-center, Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled. Phase IIb (4,000):Single-center, Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled. Nov 2020 – May 2021, China |

Phase I (45) Single-center, Randomized, Placebo-controlled, Double-blind. Aug –Oct 2020, China |

||

| MVC-COV1901 Medigen Vaccine Biologics |

Taiwan | Subunit (recombinant) | Phase II (3,700) Prospective, double-blinded, multi-center, multi-regional Dec 2020 – Jun 2021, Taiwan, Vietnam |

Phase I (45) Prospective, open-labeled, single-center Oct 2020–Jan 2021, Taiwan |

||

| Unnamed Minhai Biotechnology Co. |

China | Inactivated SARS‑CoV‑2 (vero cell) | Phase II (1,000) Randomized, double-blind, placebo parallel-controlled. Oct 2020 – Jun 2021, China |

Phase I (180) Randomized, double-blind, placebo parallel-controlled. Oct 2020 – Jun 2021, China |

||

| DelNS1-2019-nCoV-RBD-OPT Beijing Wantai Biological Pharmacy |

China | Viral vector | Phase II (720) Nov 2020 – Dec 2021, China |

Phase I (60) Sep 2020 – Oct 2021, China |

||

| Nanocovax[330] Nanogen Pharmaceutical Biotechnology JSC |

Vietnam | Subunit (SARS‑CoV‑2 recombinant spike protein with aluminum adjuvant)[331][332] | Phase II (560) Randomization, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled Feb – May 2021, Vietnam |

Phase I (60) Open label, dose escalation Dec 2020 – Jan 2021, Vietnam |

||

| Unnamed PLA Academy of Military Science, Walvax Biotech[335] |

China | RNA | Phase II (420) Jan 2021 – Mar 2022, China[336] |

Phase I (168) Jun 2020 – Dec 2021, China |

||

| INO-4800[123][124] Inovio, CEPI, Korea National Institute of Health, International Vaccine Institute |

South Korea, United States | DNA vaccine (plasmid delivered by electroporation) | Phase II–III (1,041) Phase II/III (401): Randomized, placebo-controlled, multi-center.[337] Phase IIa (640): Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, dose-finding.[338] Nov 2020 – Sep 2022, United States (phase II/III) |

Phase I–II (280) Phase Ia (120): Open-label trial. Phase Ib-IIa (160): Dose-Ranging Trial.[339] April 2020 – Feb 2022, United States, South Korea (phase Ib-IIa) |

||

| AG0302-COVID‑19 AnGes Inc.,[341] AMED |

Japan | DNA vaccine (plasmid) | Phase II–III (500) Randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled[342] Nov 2020 – May 2021, Japan |

Phase I–II (30) Randomized/non-randomized, single-center, two doses Jun – Nov 2020, Osaka |

||

| IIBR-100 (Brilife) The Israel Institute for Biological Research |

Israel | Vesicular stomatitis vector (recombinant) | Phase I–II (1,040) Oct 2020 – May 2021, Israel |

Preclinical |

||

| ARCT-021 (Lunar-COV19)[344][345] Arcturus Therapeutics, Duke–NUS Medical School |

United States, Singapore | RNA | Phase I–II (798) Phase I/II (92): Randomized, double-blinded, placebo controlled Phase IIa (106): Open label extension[346] Phase IIb (600): Randomized, observer-blind, placebo-controlled[347] Aug 2020 – Apr 2022, Singapore, United States (phase IIb) |

Preclinical |

||

| VBI-2902 Variation Biotechnologies |

United States | Virus-like particle | Phase I–II (780) Randomized, observer-blind, dose-escalation, placebo-controlled Mar 2021 – Jun 2022, Canada |

Preclinical |

||

| NDV-HXP-S Mahidol University |

Thailand | Viral vector | Phase I–II (460) Randomized, placebo-controlled, observer-blind. Mar 2021 – Apr 2022, Thailand |

Preclinical |

||

| MRT5500[350] Sanofi Pasteur and Translate Bio |

France, United States | RNA | Phase I–II (415) Immunogenicity and Safety of the First-in-Human SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Formulation in Healthy Adults 18 Years of Age and Older. Mar 2021 – May 2022, United States |

Preclinical |

||

| EuCorVac-19 EuBiologics Co |

South Korea | Subunit | Phase I–II (280) Dose-exploration, randomized, observer-blind, placebo-controlled Feb 2021 – Mar 2022, South Korea |

Preclinical |

||

| RBD SARS-CoV-2 HBsAg VLP SpyBiotech |

United Kingdom | Virus-like particle | Phase I–II (280) Randomized, placebo-controlled, multi-center. Aug 2020 – 2021, Australia |

Preclinical |

||

| GX-19 (GX-19N) Genexine consortium,[355] International Vaccine Institute |

South Korea | DNA vaccine | Phase I–II (380) Phase I-II (170-210): Multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Jun 2020 – Mar 2021, Seoul |

Preclinical |

||

| AV-COVID-19 AIVITA Biomedical, Inc., Ministry of Health (Indonesia) |

United States, Indonesia | Viral vector | Phase I–II (202) Adaptive. Dec 2020 – Jul 2021, Indonesia (phase I), United States (phase I/II) |

Preclinical |

||

| VLA2001[115][116] Valneva |

France | Inactivated SARS‑CoV‑2 | Phase I–II (150) Randomized, multi-center, double-blinded Dec 2020 – Feb 2021, United Kingdom |

Preclinical |

||

| TAK-919[358] Takeda |

Japan | RNA | Phase I–II (200) Randomized, observer-blind, placebo-controlled Jan 2021 – Mar 2022, Japan |

Preclinical |

||

| TAK-019[360] Takeda |

Japan | Subunit | Phase I–II (200) Randomized, observer-blind, placebo-controlled. Feb 2021 – April 2022, Japan |

Preclinical |

||

| COVID-eVax Takis Biotech |

Italy | DNA | Phase I–II (160) Phase I:First-in-human, dose escalation. Phase II: Open-label, randomize, dose expansion. Feb – Sep 2021, Italy |

Preclinical |

||

| ChulaCov19 Chulalongkorn University |

Thailand | RNA | Phase I–II (96) Dose-finding Study. Jan – Mar 2021, Thailand |

Preclinical |

||

| COVID‑19/aAPC Shenzhen Genoimmune Medical Institute[364] |

China | Lentiviral vector (with minigene modifying aAPCs) | Phase I (100) Mar 2020 – 2023, Shenzhen |

Preclinical |

||

| LV-SMENP-DC Shenzhen Genoimmune Medical Institute[364] |

China | Lentiviral vector (with minigene modifying DCs) | Phase I (100) Mar 2020 – 2023, Shenzhen |

Preclinical |

||

| ImmunityBio COVID-19 vaccine (hAd5) ImmunityBio |

United States | Viral vector | Phase I (160) Open-Label. Oct 2020 – Apr 2022, South Africa, United States |

Preclinical |

||

| COVAX-19 Vaxine Pty Ltd[369] |

Australia | Subunit (recombinant protein) | Phase I (40) Jun 2020 – Jul 2021, Adelaide |

Preclinical |

||

| HGC019 Gennova Biopharmaceuticals, HDT Biotech Corporation[371] |

India, United States | RNA | Phase I (120) Jan 2021 – ?, India |

Preclinical |

||

| Bio E COVID-19 (BECOV2D) Biological E. Limited, Baylor College of Medicine,[375] CEPI |

India, United States | Subunit (using an antigen) | Phase I–II (360) Randomized, Parallel Group Trial Nov 2020 – Feb 2021, India |

Preclinical |

||

| Bangavax Globe Biotech Ltd. of Bangladesh |

Bangladesh | RNA | Phase I (100) Randomized, Parallel Group Trial Feb 2021 – Feb 2022,[380] Bangladesh |

Preclinical |

||

| PTX-COVID19-B[381] Providence Therapeutics |

Canada | RNA | Phase I (60) Jan – May 2021, Canada |

Preclinical |

||

| COVAC-2[382] VIDO (University of Saskatchewan) |

Canada | Subunit | Phase I (108) Feb 2021 – Jan 2022, Halifax |

Preclinical |

||

| COVI-VAC Codagenix Inc. |

United States | Attenuated | Phase I (48) First-in-human, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation Dec 2020 – Jun 2021, United Kingdom |

Preclinical |

||

| CoV2 SAM (LNP) GSK |

United Kingdom | RNA | Phase I (48) Open-label, dose escalation, non-randomized Feb – Jun 2021, United States |

Preclinical |

||

| COVIGEN University of Sydney |

Australia | DNA | Phase I (150) Double-blind, dose-ranging, randomised, placebo-controlled. Feb 2021 – Jun 2022, Sydney |

Preclinical |

||

| BBV154 Bharat Biotech[387] |

India | Adenovirus vector (intranasal) | Phase I (175) Randomized, double-blinded, multicenter. Mar 2021, India |

Preclinical |

||

| MV-014-212[388] Meissa Vaccine Inc. |

United States | Attenuated | Phase I (130) Randomized, double-blinded, multicenter. Mar 2021 – Oct 2022, United States |

Preclinical |

||

| S-268019 Shionogi |

Japan | Subunit | Phase I–II (214) Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group. Dec 2020 – Jun 2022, Japan |

Preclinical |

||

| GBP510 SK Bioscience Co. Ltd. |

South Korea | Subunit | Phase I–II (260) Placebo-controlled, randomized, observer-blinded, dose-finding. Jan – Aug 2021, South Korea |

Preclinical |

||

| KBP-201 Kentucky Bioprocessing |

United States | Subunit | Phase I–II (180) First-in-human, observer-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel group Dec 2020 – May 2021, United States |

Preclinical |

||

| AdimrSC-2f Adimmune Corporation |

Taiwan | Subunit | Phase I (70) Randomized, single center, open-label, dose-finding. Aug – Nov 2020, Taiwan |

Preclinical |

||

| ERUCOV-VAC Health Institutes of Turkey |

Turkey | Inactivated SARS‑CoV‑2 | Phase I (44) Study for the Determination of Safety and Immunogenicity of Two Different Strengths of the Inactivated COVID-19 Vaccine ERUCOV-VAC, Given Twice Intramuscularly to Healthy Volunteers, in a Placebo Controlled Study Design. Nov 2020 – Mar 2021, Turkey |

Preclinical |

||

| AKS-452 University Medical Center Groningen |

Netherlands | Subunit | Phase I–II (130) Non-randomized, Single-center, open-label, combinatorial. Jan – Apr 2021, Netherlands |

Preclinical |

||

| GLS-5310 GeneOne Life Science Inc. |

South Korea | DNA | Phase I–II (345) Multicenter, Randomized, Combined Phase I Dose-escalation and Phase IIa Double-blind. Dec 2020 – Jul 2022, South Korea |

Preclinical |

||

| Covigenix VAX-001 Entos Pharmaceuticals Inc. |

Canada | DNA | Phase I–II (72) Placebo-controlled, randomized, observer-blind, dose ranging adaptive. Mar – Aug 2021, Canada |

Preclinical |

||

| COH04S1 City of Hope Medical Center |

United States | Viral vector | Phase I (129) Dose Escalation Study. Dec 2020 – Nov 2022, California |

Preclinical |

||

| FAKHRAVAC (MIVAC) Organization of Defensive Innovation and Research |

Iran | Inactivated SARS‑CoV‑2 | Phase I (135) Randomized, double blind, controlled trial with factorial design. Mar – Apr 2021, Iran |

Preclinical |

||

| NBP2001 SK Bioscience Co. Ltd. |

South Korea | DNA | Phase I (50) Placebo-controlled, Randomized, Observer-blinded, Dose-escalation. Dec 2020 – Apr 2021, South Korea |

Preclinical |

||

| CoVac-1 University Hospital Tuebingen |

Germany | Subunit | Phase I (36) Placebo-controlled, Randomized, Observer-blinded, Dose-escalation. Nov 2020 – Sep 2021, Germany |

Preclinical |

||

| bacTRL-Spike Symvivo |

Canada | DNA | Phase I (24) Randomized, observer-blind, placebo-controlled. Nov 2020 – Feb 2022, Australia |

Preclinical |

||

| Razi Cov Pars Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute |

Iran | Subunit | Phase I (133) Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled. Jan – Mar 2021, Iran |

Preclinical |

||

| CORVax12 Providence Health & Services |

United States | DNA | Phase I (36) Open-label. Dec 2020 – May 2021, United States |

Preclinical |

||

| ChAdV68-S NIAID, Gritstone Oncology |

United States | Viral vector | Phase I (130) Open-label, dose and age escalation, parallel design. Mar 2021 – Sep 2022, United States |

Preclinical |

||

| AdCOVID Altimmune Inc. |

United States | Viral vector | Phase I (180) Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, first-in-Human. Feb 2021 – Feb 2022, United States |

Preclinical |

||

| VXA-CoV2-1 Vaxart |

United States | Viral vector | Phase I (35) Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, first-in-Human. Sep – Dec 2020, United States |

Preclinical |

||

| AdCLD-CoV19 Cellid Co |

South Korea | Viral vector | Phase I (150) Phase I: Dose Escalation, Single Center, Open. Phase IIa: Multicenter, Randomized, Open. Dec 2020 – Mar 2021, South Korea |

Preclinical |

||

| SpFN COVID-19 Vaccine United States Army Medical Research and Development Command |

United States | Subunit | Phase I (72) Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled. Apr 2021 – Oct 2022, United States |

Preclinical |

||

| MVA-SARS-2-S University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf |

Germany | Viral vector | Phase I (30) Open, Single-center. Oct 2020 – May 2021, Germany |

Preclinical |

||

| LNP-nCoVsaRNA MRC clinical trials unit at Imperial College London |

United Kingdom | RNA | Terminated (105) Randomized trial, with dose escalation study (15) and expanded safety study (at least 200) Jun 2020 – Jul 2021, United Kingdom |

? |

||

| COVID-19-101 Institut Pasteur |

France | Viral vector | Terminated (90) Randomized, Placebo-controlled. Aug – Nov 2020, Belgium, France |

? |

||

| SARS-CoV-2 Sclamp/V451 UQ, Syneos Health, CEPI, Seqirus |

Australia | Subunit (molecular clamp stabilized spike protein with MF59) | Terminated (120) Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging. False positive HIV test found among participants. Jul–Oct 2020, Brisbane |

? |

||

| V590[413] and V591/MV-SARS-CoV-2[414] Merck & Co. (Themis BIOscience), Institut Pasteur, University of Pittsburgh's Center for Vaccine Research (CVR), CEPI | United States, France | Vesicular stomatitis virus vector[415] / Measles virus vector[416] | Terminated In phase I, immune responses were inferior to those seen following natural infection and those reported for other SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 vaccines.[417] |

- ^ Storage temperature for the frozen Gam-COVID-Vac formulation. The lyophilised Gam-COVID-Vac-Lyo formulation can be stored at 2-8°C.[181]

- ^ Serum Institute of India will be producing the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine for India[190] and other low- and middle-income countries.[191]

- ^ Oxford name: ChAdOx1 nCoV-19. Manufacturing in Brazil to be carried out by Oswaldo Cruz Foundation.[192]

- ^ a b Recommended interval. The second dose of the Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna vaccines can be administered up to 6 weeks after the first dose to alleviate a shortage of supplies.[199][200]

- ^ Long-term storage temperature. The Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine can be kept between −25 and −15 °C (−13 and 5 °F) for up to two weeks before use, and between 2 and 8 °C (36 and 46 °F) for up to five days before use.[201][202]

- ^ Latest Phase with published results.

- ^ Virus-like particles grown in Nicotiana benthamiana[302]

- ^ Phase I–IIa in South Korea in parallel with Phase II–III in the US

Formulation

As of September 2020[update], eleven of the vaccine candidates in clinical development use adjuvants to enhance immunogenicity.[23] An immunological adjuvant is a substance formulated with a vaccine to elevate the immune response to an antigen, such as the COVID‑19 virus or influenza virus.[418] Specifically, an adjuvant may be used in formulating a COVID‑19 vaccine candidate to boost its immunogenicity and efficacy to reduce or prevent COVID‑19 infection in vaccinated individuals.[418][419] Adjuvants used in COVID‑19 vaccine formulation may be particularly effective for technologies using the inactivated COVID‑19 virus and recombinant protein-based or vector-based vaccines.[419] Aluminum salts, known as "alum", were the first adjuvant used for licensed vaccines, and are the adjuvant of choice in some 80% of adjuvanted vaccines.[419] The alum adjuvant initiates diverse molecular and cellular mechanisms to enhance immunogenicity, including release of proinflammatory cytokines.[418][419]

Deployment

| Location | Vaccinated[a] | Percent[b] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| World[c][d] | 5,645,247,500 | 70.70% | |

| China[e] | 1,318,026,800 | 92.48% | |

| India | 1,027,438,900 | 72.08% | |

| European Union[f] | 338,481,060 | 75.43% | |

| United States[g] | 270,227,170 | 79.12% | |

| Indonesia | 204,419,400 | 73.31% | |

| Brazil | 189,643,420 | 90.17% | |

| Pakistan | 165,567,890 | 67.94% | |

| Bangladesh | 151,507,170 | 89.45% | |

| Japan | 104,740,060 | 83.79% | |

| Mexico | 97,179,496 | 75.56% | |

| Nigeria | 93,829,430 | 42.05% | |

| Vietnam | 90,497,670 | 90.79% | |

| Russia | 89,081,600 | 61.19% | |

| Philippines | 82,684,776 | 72.55% | |

| Iran | 65,199,830 | 72.83% | |

| Germany | 64,876,300 | 77.15% | |

| Turkey | 57,941,052 | 66.55% | |

| Thailand | 57,005,496 | 79.47% | |

| Egypt | 56,907,320 | 50.53% | |

| France | 54,677,680 | 82.50% | |

| United Kingdom | 53,806,964 | 78.92% | |

| Ethiopia | 52,489,510 | 41.86% | |

| Italy[h] | 50,936,720 | 85.44% | |

| South Korea | 44,764,956 | 86.45% | |

| Colombia | 43,012,176 | 83.13% | |

| Myanmar | 41,551,930 | 77.30% | |

| Argentina | 41,529,056 | 91.46% | |

| Spain | 41,351,230 | 86.46% | |

| Canada | 34,742,936 | 89.49% | |

| Tanzania | 34,434,932 | 53.21% | |

| Peru | 30,563,708 | 91.30% | |

| Malaysia | 28,138,564 | 81.10% | |

| Nepal | 27,883,196 | 93.83% | |

| Saudi Arabia | 27,041,364 | 84.04% | |

| Morocco | 25,020,168 | 67.03% | |

| South Africa | 24,210,952 | 38.81% | |

| Poland | 22,984,544 | 59.88% | |

| Mozambique | 22,869,646 | 70.03% | |

| Australia | 22,231,734 | 84.85% | |

| Venezuela | 22,157,232 | 78.54% | |

| Uzbekistan | 22,094,470 | 63.24% | |

| Taiwan | 21,899,240 | 93.51% | |

| Uganda | 20,033,188 | 42.34% | |

| Afghanistan | 19,151,368 | 47.20% | |

| Chile | 18,088,516 | 92.51% | |

| Sri Lanka | 17,143,760 | 75.08% | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 17,045,720 | 16.65% | |

| Angola | 16,550,642 | 46.44% | |

| Ukraine | 16,267,198 | 39.63% | |

| Ecuador | 15,345,791 | 86.10% | |

| Cambodia | 15,316,670 | 89.04% | |

| Sudan | 15,207,452 | 30.79% | |

| Kenya | 14,494,372 | 26.72% | |

| Ghana | 13,864,186 | 41.82% | |

| Ivory Coast | 13,568,372 | 44.64% | |

| Netherlands | 12,582,081 | 70.27% | |

| Zambia | 11,711,565 | 58.11% | |

| Iraq | 11,332,925 | 25.72% | |

| Rwanda | 10,884,714 | 79.74% | |

| Kazakhstan | 10,858,101 | 54.20% | |

| Cuba | 10,805,570 | 97.70% | |

| United Arab Emirates | 9,991,089 | 97.55% | |

| Portugal | 9,821,414 | 94.28% | |

| Belgium | 9,261,641 | 79.55% | |

| Somalia | 8,972,167 | 50.40% | |

| Guatemala | 8,937,923 | 50.08% | |

| Tunisia | 8,896,848 | 73.41% | |

| Guinea | 8,715,641 | 62.01% | |

| Greece | 7,938,031 | 76.24% | |

| Algeria | 7,840,131 | 17.24% | |

| Sweden | 7,775,726 | 74.14% | |

| Zimbabwe | 7,525,882 | 46.83% | |

| Dominican Republic | 7,367,193 | 65.60% | |

| Bolivia | 7,361,008 | 60.95% | |

| Israel | 7,055,466 | 77.51% | |

| Czech Republic | 6,982,006 | 65.42% | |

| Hong Kong | 6,920,057 | 92.69% | |

| Austria | 6,899,873 | 76.12% | |

| Honduras | 6,596,213 | 63.04% | |

| Belarus | 6,536,392 | 71.25% | |

| Hungary | 6,420,354 | 66.30% | |

| Nicaragua | 6,404,524 | 95.15% | |

| Niger | 6,248,483 | 24.69% | |

| Switzerland | 6,096,911 | 69.34% | |

| Burkina Faso | 6,089,089 | 27.05% | |

| Laos | 5,888,649 | 77.90% | |

| Sierra Leone | 5,676,123 | 68.58% | |

| Romania | 5,474,507 | 28.56% | |

| Malawi | 5,433,538 | 26.42% | |

| Azerbaijan | 5,373,253 | 52.19% | |

| Tajikistan | 5,328,277 | 52.33% | |

| Singapore | 5,287,005 | 93.58% | |

| Chad | 5,147,667 | 27.89% | |

| Jordan | 4,821,579 | 42.83% | |

| Denmark | 4,746,522 | 80.41% | |

| El Salvador | 4,659,970 | 74.20% | |

| Costa Rica | 4,650,636 | 91.52% | |

| Turkmenistan | 4,614,869 | 63.83% | |

| Finland | 4,524,288 | 81.24% | |

| Mali | 4,354,292 | 18.87% | |

| Norway | 4,346,995 | 79.66% | |

| South Sudan | 4,315,127 | 39.15% | |

| New Zealand | 4,302,330 | 83.84% | |

| Republic of Ireland | 4,112,237 | 80.47% | |

| Paraguay | 3,995,915 | 59.11% | |

| Liberia | 3,903,802 | 72.65% | |

| Cameroon | 3,753,733 | 13.58% | |

| Panama | 3,746,041 | 85.12% | |

| Benin | 3,697,190 | 26.87% | |

| Kuwait | 3,457,498 | 75.33% | |

| Serbia | 3,354,075 | 49.39% | |

| Syria | 3,295,630 | 14.67% | |

| Oman | 3,279,632 | 69.33% | |

| Uruguay | 3,010,464 | 88.78% | |

| Qatar | 2,852,178 | 98.61% | |

| Slovakia | 2,840,017 | 51.89% | |

| Lebanon | 2,740,227 | 47.70% | |

| Madagascar | 2,710,365 | 8.90% | |

| Senegal | 2,684,696 | 15.21% | |

| Central African Republic | 2,600,389 | 51.01% | |

| Croatia | 2,323,025 | 59.46% | |

| Libya | 2,316,327 | 32.07% | |

| Mongolia | 2,284,018 | 67.45% | |

| Togo | 2,255,579 | 24.81% | |

| Bulgaria | 2,155,863 | 31.58% | |

| Mauritania | 2,103,754 | 43.15% | |

| Palestine | 2,012,767 | 37.94% | |

| Lithuania | 1,958,299 | 69.52% | |

| Botswana | 1,951,054 | 79.96% | |

| Kyrgyzstan | 1,736,541 | 24.97% | |

| Georgia | 1,654,504 | 43.60% | |

| Albania | 1,349,255 | 47.72% | |

| Latvia | 1,346,184 | 71.57% | |

| Slovenia | 1,265,802 | 59.84% | |

| Bahrain | 1,241,174 | 80.94% | |

| Armenia | 1,150,915 | 39.95% | |

| Mauritius | 1,123,773 | 88.06% | |

| Moldova | 1,109,524 | 36.50% | |

| Yemen | 1,050,202 | 2.75% | |

| Lesotho | 1,014,073 | 44.36% | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 943,394 | 29.44% | |

| Kosovo | 906,858 | 52.79% | |

| Timor-Leste | 886,838 | 64.77% | |

| Estonia | 870,202 | 64.46% | |

| Jamaica | 859,773 | 30.28% | |

| North Macedonia | 854,570 | 46.44% | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 754,399 | 50.43% | |

| Guinea-Bissau | 747,057 | 35.48% | |

| Fiji | 712,025 | 77.44% | |

| Bhutan | 699,116 | 89.52% | |

| Republic of the Congo | 695,760 | 11.53% | |

| Macau | 679,703 | 96.50% | |

| Gambia | 674,314 | 25.58% | |

| Cyprus | 671,193 | 71.37% | |

| Namibia | 629,767 | 21.79% | |

| Eswatini | 526,050 | 43.16% | |

| Haiti | 521,396 | 4.53% | |

| Guyana | 497,550 | 60.56% | |

| Luxembourg | 481,957 | 73.77% | |

| Malta | 478,953 | 90.68% | |

| Brunei | 451,149 | 99.07% | |

| Comoros | 438,825 | 52.60% | |

| Djibouti | 421,573 | 37.07% | |

| Maldives | 399,308 | 76.19% | |

| Papua New Guinea | 382,020 | 3.74% | |

| Cabo Verde | 356,734 | 68.64% | |

| Solomon Islands | 343,821 | 44.02% | |

| Gabon | 311,244 | 12.80% | |

| Iceland | 309,770 | 81.44% | |

| Northern Cyprus | 301,673 | 78.80% | |

| Montenegro | 292,783 | 47.63% | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 270,109 | 14.98% | |

| Suriname | 267,820 | 42.98% | |

| Belize | 258,473 | 64.18% | |

| New Caledonia | 192,375 | 67.00% | |

| Samoa | 191,403 | 88.91% | |

| French Polynesia | 190,908 | 68.09% | |

| Vanuatu | 176,624 | 56.42% | |

| Bahamas | 174,810 | 43.97% | |

| Barbados | 163,853 | 58.04% | |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 140,256 | 61.97% | |

| Curaçao | 108,601 | 58.59% | |

| Kiribati | 100,900 | 77.33% | |

| Aruba | 90,546 | 84.00% | |

| Seychelles | 88,520 | 70.52% | |

| Tonga | 87,375 | 83.17% | |

| Jersey | 84,365 | 81.52% | |

| Isle of Man | 69,560 | 82.67% | |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 64,290 | 69.24% | |

| Cayman Islands | 62,113 | 86.74% | |

| Saint Lucia | 60,140 | 33.64% | |

| Andorra | 57,913 | 72.64% | |

| Guernsey | 54,223 | 85.06% | |

| Bermuda | 48,554 | 74.96% | |

| Grenada | 44,241 | 37.84% | |

| Gibraltar | 42,175 | 112.08% | |

| Faroe Islands | 41,715 | 77.19% | |

| Greenland | 41,227 | 73.60% | |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 37,532 | 36.77% | |

| Burundi | 36,909 | 0.28% | |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 33,794 | 72.32% | |

| Dominica | 32,995 | 49.36% | |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | 32,815 | 71.54% | |

| Sint Maarten | 29,788 | 70.65% | |

| Monaco | 28,875 | 74.14% | |

| Liechtenstein | 26,771 | 68.06% | |

| San Marino | 26,357 | 77.26% | |

| British Virgin Islands | 19,466 | 50.77% | |

| Caribbean Netherlands | 19,109 | 66.69% | |

| Cook Islands | 15,112 | 102.48% | |

| Nauru | 13,106 | 110.87% | |

| Anguilla | 10,858 | 76.45% | |

| Tuvalu | 9,763 | 97.51% | |

| Wallis and Futuna | 7,150 | 62.17% | |

| Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha | 4,361 | 81.23% | |

| Falkland Islands | 2,632 | 74.88% | |

| Tokelau | 2,203 | 95.29% | |

| Montserrat | 2,104 | 47.01% | |

| Niue | 1,638 | 88.83% | |

| Pitcairn Islands | 47 | 100.00% | |

| North Korea | 0 | 0.00% | |

| |||

As of 12 August 2024[update], 13.53 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered worldwide, with 70.6 percent of the global population having received at least one dose.[421][422] While 4.19 million vaccines were then being administered daily, only 22.3 percent of people in low-income countries had received at least a first vaccine by September 2022, according to official reports from national health agencies, which are collated by Our World in Data.[423]

During a pandemic on the rapid timeline and scale of COVID-19 cases in 2020, international organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) and Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), vaccine developers, governments, and industry evaluated the distribution of the eventual vaccine(s).[424] Individual countries producing a vaccine may be persuaded to favor the highest bidder for manufacturing or provide first-class service to their own country.[425][426][427] Experts emphasize that licensed vaccines should be available and affordable for people at the frontlines of healthcare and in most need.[425][427]

In April 2020, it was reported that the UK agreed to work with 20 other countries and global organizations, including France, Germany, and Italy, to find a vaccine and share the results, and that UK citizens would not get preferential access to any new COVID‑19 vaccines developed by taxpayer-funded UK universities.[428] Several companies planned to initially manufacture a vaccine at artificially low prices, then increase prices for profitability later if annual vaccinations are needed and as countries build stock for future needs.[427]

The WHO had set out the target to vaccinate 40% of the population of all countries by the end of 2021 and 70% by mid-2022,[429] but many countries missed the 40% target at the end of 2021.[430][431]Liability

The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2020) |

On 4 February 2020, US Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar published a notice of declaration under the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act for medical countermeasures against COVID‑19, covering "any vaccine, used to treat, diagnose, cure, prevent, or mitigate COVID‑19, or the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 or a virus mutating therefrom", and stating that the declaration precludes "liability claims alleging negligence by a manufacturer in creating a vaccine, or negligence by a health care provider in prescribing the wrong dose, absent willful misconduct".[432] The declaration is effective in the United States through 1 October 2024.[432]

In the European Union, the COVID‑19 vaccines are licensed under a Conditional Marketing Authorisation which does not exempt manufacturers from civil and administrative liability claims.[433] While the purchasing contracts with vaccine manufacturers remain secret, they do not contain liability exemptions even for side-effects not known at the time of licensure.[434]

Pfizer has been criticised for demanding far-reaching liability waivers and other guarantees from countries such as Argentina and Brazil, which go beyond what was expected from other countries such as the US (above).[435][436]

Society and culture

Access

Nations pledged to buy doses of COVID-19 vaccine before the doses were available. Though high-income nations represent only 14% of the global population, as of 15 November 2020, they had contracted to buy 51% of all pre-sold doses. Some high-income nations bought more doses than would be necessary to vaccinate their entire populations.[437]

On 18 January 2021, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warned of problems with equitable distribution: "More than 39 million doses of vaccine have now been administered in at least 49 higher-income countries. Just 25 doses have been given in one lowest-income country. Not 25 million; not 25 thousand; just 25."[438]

Some nations involved in long-standing territorial disputes have reportedly had their access to vaccines blocked by competing nations; Palestine has accused Israel blocking vaccine delivery to Gaza, while Taiwan has suggested that China has hampered its efforts to procure vaccine doses.[439][440][441]

A single dose of the COVID-19 vaccine by AstraZeneca would cost 47 Egyptian pounds (EGP) and the authorities are selling it between 100 and 200 EGP. A report by Carnegie Endowment for International Peace cited the current poverty rate in Egypt as around 29.7 percent, which constitutes approximately 30.5 million people, and claimed that about 15 million of the Egyptians would be unable to gain access to the luxury of vaccination. A human rights lawyer, Khaled Ali launched a lawsuit against the government, forcing them to provide vaccination free of cost to all members of the public.[442]

According to immunologist Dr. Anthony Fauci, mutant strains of virus and limited vaccine distribution pose continuing risks and he said: "we have to get the entire world vaccinated, not just our own country."[443] Edward Bergmark and Arick Wierson are calling for an global vaccination effort and wrote that the wealthier nations' "me-first" mentality could ultimately backfire, because the spread of the virus in poorer countries would lead to more variants, against which current vaccines could be less effective.[444]

On 10 March 2021, the United States, Britain, European Union nations and other WTO members, blocked a push by over 80 developing countries to waive COVID-19 vaccine patent rights in an effort to boost production of vaccines for poor nations.[445]

Misinformation

Vaccine hesitancy

Some 10% of the public perceives vaccines as unsafe or unnecessary, refusing vaccination – a global health threat called vaccine hesitancy[446] – which increases the risk of further viral spread that could lead to COVID‑19 outbreaks.[37] As of May 2020, estimates from two surveys were that 67% or 80% of people in the U.S. would accept a new vaccination against COVID‑19, with wide disparity by education level, employment status, ethnicity, and geography.[447] As of March 2021, 19% of US adults claim to have been vaccinated and 50% of US adults plan to get vaccinated.[448][449]

In an effort to demonstrate the vaccine's safety, prominent politicians have received it on camera, with others pledging to do so.[450][451][452]

Encouragement by public figures and celebrities

Due to vaccine hesitancy caused by COVID vaccine conspiracy theories many public figures and celebrities have publicly declared and they have been vaccinated and encouraged people to have COVID vaccines, many documented themselves getting vaccinated.[453]

Politicians and heads of state

Several heads of state and government ministers have released photographs of their vaccinations, encouraging others to be vaccinated including Kyriakos Mitsotakis, Zdravko Marić, Olivier Véran, US President Joe Biden, Former US Presidents Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton, the Dalai Lama, all nine US Supreme Court Justices, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Nancy Pelosi and Kamala Harris.[454][455][456]

Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip announced they had had the vaccine, breaking from protocol of keeping the British royal family's health private.[453] Pope Francis and ex Pope Benedict both announced they had been vaccinated.[453]

Musicians

Dolly Parton recorded herself getting vaccinated with the Moderna vaccine she helped fund, she encouraged people to get vaccinated and created a new version of her song "Jolene" called "Vaccine".[453] Patti Smith, Yo-Yo Ma, Carole King, Tony Bennett, Mavis Staples, Brian Wilson, Joel Grey, Loretta Lynn, Willie Nelson, and Paul Stanley have all released photographs of them being vaccinated and encouraged others to do so.[457] Grey stated "I got the vaccine because I want to be safe. We've lost so many people to COVID. I've lost a few friends. It's heartbreaking. Frightening."[454]

Actresses and actors

Amy Schumer, Rosario Dawson, Arsinio Hall, Danny Trejo, Mandy Patinkin, Magic Johnson, Samuel L. Jackson, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Buzz Aldrin, Sharon Stone, Kate Mulgrew, Jeff Goldblum, Jane Fonda, Anthony Hopkins, Bette Midler, Kim Catrell, Isabella Rosselini, Christie Brinkley, Cameran Eubanks, Hugh Bonneville, Alan Alda, David Harbour, Sean Penn, Johnathan Van Ness, Dan Rather, Al Roker, Amanda Kloots, Kareem Abdul Jabbar, Martha Stewart, Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart have released photographs of themselves getting vaccinated and encouraging others to do the same.[453][458]

Stephen Fry was photographed being vaccinated, described it as a "wonderful moment, but you feel that it's not only helpful for your own health, but you know that you're likely to be less contagious if you yourself happen to carry it... It's a symbol of being part of society, part of the group that we all want to protect each other and get this thing over and done with."[453] Dame Judi Dench, Sir David Attenborough, Joan Collins have announced they have been vaccinated.[453]

Specific communities

Romesh Ranganathan, Meera Syal, Adil Ray, Sadiq Khan and others produced a video specifically encouraging ethnic minority communities in the UK to be vaccinated including addressing conspiracy theories stating 'there is no scientific evidence to suggest it will work differently on people from ethnic minorities and that it does not include pork or any material of fetal or animal origin'.[459]

Oprah Winfrey and Whoopi Goldberg have spoken about being vaccinated for COVID and encouraged black Americans to be vaccinated.[460][461] Stephanie Elam volunteered to be a trial volunteer stating "a large part of the reason why I wanted to volunteer for this COVID-19 vaccine research — more Black people and more people of color need to be part of these trials so more diverse populations can reap the benefits of this medical research."[454]

See also

References