Xiang Chinese

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2013) |

| Xiang | |

|---|---|

| Hunanese | |

| 湘語/湘语 | |

"Xiang Language" written in Chinese characters | |

| Native to | China |

| Region | Central and southwestern Hunan, northern Guangxi, parts of Guizhou and Hubei provinces |

| Ethnicity | Hunanese people (Han Chinese) |

Native speakers | 38 million (2007)[1] |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Dialects | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | hsn |

| Glottolog | xian1251 |

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-e |

| |

| Xiang Chinese | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 湘語 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 湘语 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Hunanese | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 湖南話 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 湖南话 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Xiang or Hsiang (Chinese: 湘; pinyin: xiāng; Mandarin pronunciation: [ɕi̯ɑ́ŋ]), also known as Hunanese (English: /ˌhuːnɑːˈniːz/), is a group of linguistically similar and historically related varieties of Chinese, spoken mainly in Hunan province but also in northern Guangxi and parts of neighboring Guizhou and Hubei provinces. Scholars divided Xiang into five subgroups, Chang-Yi, Lou-Shao, Hengzhou, Chen-Xu and Yong-Quan.[2] Among those, Lou-shao, also known as Old Xiang, still exhibits the three-way distinction of Middle Chinese obstruents, preserving the voiced stops, fricatives, and affricates. Xiang has also been heavily influenced by Mandarin, which adjoins three of the four sides of the Xiang speaking territory, and Gan in Jiangxi Province, from where a large population immigrated to Hunan during the Ming Dynasty.[3]

Xiang-speaking Hunanese people have played an important role in Modern Chinese history, especially in those reformatory and revolutionary movements such as the Self-Strengthening Movement, Hundred Days' Reform, Xinhai Revolution[4] and Chinese Communist Revolution.[5] Some examples of Xiang speakers are Mao Zedong, Zuo Zongtang, Huang Xing and Ma Ying-jeou.[6]

History

Ancient ages

Prehistorically, the main inhabitants were the ancient country of Ba, Nanman, Baiyue and other tribes whose languages cannot be studied. During the Warring States period, large numbers of Chu migrated into Hunan. Their language blended with that of the original natives to produce a new dialect Nanchu (Southern Chu).[7] During Qin and Han dynasty, most part of today's Eastern Hunan belonged to Changsha-Xian/Changsha-Guo. According to Yang Xiong's Fangyan, people in this region spoke Southern Chu, which is considered the ancestor of Xiang Chinese today.[8]

Middle ages and recent history

During the Tang dynasty, a large-scale emigration took place with people emigrating from the north to the south, bringing Middle Chinese into Hunan.[9] Today's Xiang still keeps some Middle Chinese words, such as 嬉 (to have fun), 薅 (to weed), 行 (to walk). Entering tone vowels started weakening in Hunan at this time. Migrants who came from the North mainly in northern Hunan followed by western Hunan. For this reason northern and western Hunan are Mandarin districts.[7]

Migrants from Jiangxi concentrated mainly in southeastern Hunan and present day Shaoyang and Xinhua districts. They came for two reasons:[7] The first is that Jiangxi became too crowded and its people sought expansion. The second is that Hunan suffered greatly during the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty, when there was mass slaughter.[10] The late Yuan Dynasty peasant uprising caused a great many casualties in Hunan.

During the Ming dynasty, a large-scale emigration from Jiangxi to Hunan took place. In the early Ming dynasty, large numbers of migrants came from Jiangxi and settled in present day Yueyang, Changsha, Zhuzhou, Xiangtan, and Hengyang districts. After the middle of the Ming dynasty, migrants came more diverse, and came more for economic reasons and commerce.[7] Gan, which was brought by settlers from Jiangxi, influenced Xiang. The speech in east Hunan differentiated into New Xiang during that period.

Quanzhou County became part of Guangxi province after the adjustment of administrative divisions in the Ming Dynasty. Some features of Xiang at that time were kept in this region.

Classification

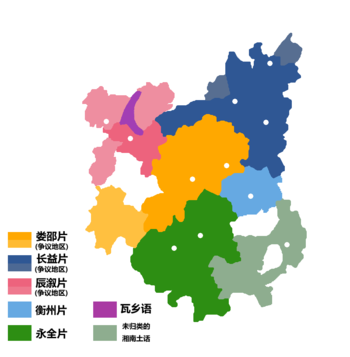

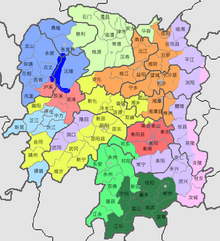

Note other dialects are shown in larger areas than in the next map. Hakka pink, Southwestern Mandarin light blue, medium blue, light green, and Waxiang dark blue

Since the classification of Yuan Jiahua (1960), Xiang has been considered one of seven major groups of varieties of Chinese.[11] Jerry Norman classified Xiang, Gan and Wu, as central groups, intermediate between the Mandarin group to the north and the southern groups, Min, Hakka and Yue.[12]

In Xiang dialects, the voiced initials of Middle Chinese yield unaspirated initials in all tone categories. A few varieties have retained voicing in all tones, but most have voiceless initials in some or all tone categories.[13]

| gloss | Middle Chinese | Chengbu | Shuangfeng | Shaoyang | Changsha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| peach | 桃 daw | dao2 | də2 | daɤ2 | taɤ2 |

| sit | 坐 dzwaX | dzo6 | dzu6 | tso6 | tso6 |

| together | 共 gjowngH | goŋ6 | gaŋ6 | kong6 | kong5 |

| white | 白 baek | ba7 | piɛ6 | pe6 | pɤ7 |

|

Pervasive influence from Mandarin dialects has made Xiang dialects difficult to classify.[13] Yuan Jiahua divided Xiang into New Xiang, in which voicing has been lost completely, and Old Xiang varieties, which retain voiced initials in at least some tones.[14] The Changsha dialect is usually taken as representative of New Xiang, while Shuangfeng dialect represents Old Xiang.[15] Norman describes the boundary between New Xiang and Southwestern Mandarin as one of the weakest in China, with considerable similarities between dialects near either side of the boundary, though more distant dialects are mutually unintelligible.[16] Indeed, Zhou Zhenhe and You Rujie (unlike most authors) classified New Xiang as part of Southwestern Mandarin.[17][18]

The Language Atlas of China relabelled the New and Old Xiang groups as Chang-Yi and Lou-Shao respectively, and identified a third subgroup, Ji-Xu, in some parts of Western Hunan.[19] Bao & Chen (2005) split out part of Atlas's Chang-Yi subgroup as a new Hengzhou subgroup, and part of Lou-Shao as a Yong-Quan subgroup. They also reclassified parts of the Ji–Xu subgroup as Southwestern Mandarin, renaming the remainder of the subgroup as Chen-Xu Xiang. Their five subgroups are:

- Chang-Yi

- (17.8 million speakers) voiced initials in Middle Chinese become unaspirated voiceless consonant. Most of the dialects retain the entering tone as a separate category.

- Lou-Shao

- (11.5 million speakers) Voiced initials still exist. The entering tone does not exist in most of the dialects.

- Chen-Xu Xiang

- (3.4 million speakers) Some of the voiced consonants are retained.

- Hengzhou Xiang

- (4.3 million speakers)

- Yong-Quan Xiang

- (6.5 million speakers) Voiced consonants still exist.

Geographic distribution

Xiang is spoken by over 36 million people in China, primarily in the most part of the Hunan province, and in the four counties of Quanzhou, Guanyang, Ziyuan, and Xing'an in northeastern Guangxi province, and in several places of Guizhou and Guangdong provinces. It is abutted by Southwestern Mandarin-speaking areas to the north and west, as well as by Gan in the eastern parts of Hunan and Jiangxi. Xiang is also in contact with the Qo-Xiong Miao and Tujia languages in West Hunan.

References

- ^ Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

- ^ 鲍, 鲍; 陈晖 (24 August 2005). 湘语的分区(稿). 方言 (2005年第3期): 261.

- ^ 徐, 明. 60%湖南人是从江西迁去的 专家:自古江西填湖广. 人民网. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Qi, Feng (October 2010). 辛亥革命,多亏了不怕死的湖南人. 文史博览 (2011年第10期). Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ Ma, Na. 揭秘:建党时为啥湖南人特别多 都有哪些人?. 中国共产党新闻网. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ Liu, Shuangshuang (20 July 2005). 湖南表兄称马英九祖籍湖南湘潭 祖坟保存完好. Xinhua Net. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d Jiang 2006, p. 8.

- ^ 袁家骅 (1983). 汉语方言槪要. p. 333. ISBN 9787801264749.

- ^ 旧唐书. Vol. 地理志.

中原多故,襄邓百姓,两京衣冠,尽投江湘,故荆南井邑,十倍其初,乃置荆南节度使。

- ^ Coblin, W. South (2011). Comparative Phonology of the Central Xiāng Dialects. Taipei, Taiwan: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica. ISBN 978-986-02-9803-1.

- ^ Norman 1988, p. 181.

- ^ Norman 1988, pp. 181–183.

- ^ a b c Norman 1988, p. 207.

- ^ Wu 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Yan 2006, p. 107.

- ^ Norman 1988, p. 190.

- ^ Zhou & You 1986.

- ^ Kurpaska 2010, p. 55.

- ^ Yan 2006, pp. 105, 107.

Bibliography

- Bào, Hòuxīng 鮑厚星; Chén, Huī 陳暉 (2005). "Xiāngyǔ de fēnqū" 湘語的分區 [The divisions of Xiang languages]. Fāngyán: 261–270.

- Jiang, Junfeng (June 2006). Xiāngxiāng fāngyán yǔyīn yánjiū 湘乡方言语音研究 [A Phonological Study of Xiangxiang Dialect] (PhD thesis). Hunan Normal University. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

{{cite thesis}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kurpaska, Maria (2010). Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism of "The Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects". Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-021914-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29653-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wu, Yunji (2005). A synchronic and diachronic study of the grammar of the Chinese Xiang dialects. Trends in linguistics. Vol. 162. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-018366-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yan, Margaret Mian (2006). Introduction to Chinese Dialectology. LINCOM Europa. ISBN 978-3-89586-629-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yang, Shifeng (楊時逢) (1974). 湖南方言調查報告 (1-2). 中央研究院歷史語言研究所專刊[第66卷]. Taipei: 中央研究院歷史語言研究所. ISBN 978-0009121760..

- Yuan, Jiahua (1989) [1960]. Hànyǔ fāngyán gàiyào 漢語方言概要 [An introduction to Chinese dialects]. Beijing: Wénzì gǎigé chūbǎnshè 文字改革出版社.

- Zhou, Zhenhe; You, Rujie (1986). Fāngyán yǔ zhōngguó wénhuà 方言与中国文化 [Dialects and Chinese culture]. Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Xiang at Omniglot

- Hunan Provincial Gazetteer: dialects 湖南省志: 方言志