Cantonese

| Cantonese | |

|---|---|

| 廣東話 / 广东话 Gwóngdūng Wah / gwong2 dung1 waa6 廣州話 / 广州话 Gwóngjàu Wah / gwong2 zau1 waa6 | |

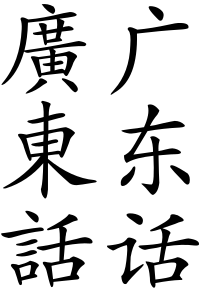

Gwóngdūng Wah / gwong2 dung1 waa6 (Cantonese) written in traditional Chinese (left) and simplified Chinese (right) characters | |

| Native to | China, Hong Kong, Macau, Overseas Communities |

| Region | Guangdong, eastern Guangxi |

| Dialects | |

| Written Cantonese Cantonese Braille Written Chinese | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | yyef (Yue F) |

| Glottolog | cant1236 |

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-ma |

| This article is part of the series on the |

| Cantonese language |

|---|

| Yue Chinese |

| Grammar |

|

| Phonology |

Cantonese, or Standard Cantonese (t廣東話, s广东话; originally known as t廣州話, s广州话),[2][3] is the dialect of Yue Chinese spoken in the vicinity of Canton in southern China. It is the traditional prestige dialect of Yue.

Cantonese is the language of the Cantonese people. Inside mainland China, it is a lingua franca in Guangdong Province and some neighbouring areas, such as the eastern part of Guangxi Province. It is the majority language of Hong Kong, Macau and the Pearl River Delta region of China. It is also the most spoken variety of Chinese among overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia (most notably in Vietnam, Malaysia, and Singapore) and the Western world, especially Canada, Australia, Western Europe, and the United States.

While the term Cantonese refers narrowly to the prestige variety, it is often used in a broader sense for the entire Yue branch of Chinese, including related but largely mutually unintelligible dialects such as Taishanese. When standard Cantonese and the closely related Yuehai dialects are classified together, there are about 80 million total speakers.[4]

Cantonese is viewed as part of the cultural identity for its native speakers across large swathes of southern China, Hong Kong and Macau. Although Cantonese shares some vocabulary with Mandarin Chinese, the two varieties are mutually unintelligible because of pronunciation, grammatical, and also lexical differences. Sentence structure, in particular the placement of verbs, sometimes differs between the two varieties. More historic roots can often be found in Cantonese vocabulary. One of the most notable differences between Cantonese and Mandarin is how the spoken word is written; both can be recorded verbatim but very few Cantonese speakers are knowledgeable in the full Cantonese written vocabulary, so a non-verbatim formalised written form is adopted which is more akin to the Mandarin written form.[5][6] This results in the situation in which a Mandarin and Cantonese text may look similar, but are pronounced differently.

Names

In English, the term "Cantonese" is ambiguous. Cantonese proper is the variety native to the city of Canton, which is the traditional English name of Guangzhou. This narrow sense may be specified as "Canton language" or "Guangzhou language" in English.[7]

However, "Cantonese" may also refer to the primary branch of Cantonese that contains Cantonese proper as well as Taishanese and Gaoyang; this broader usage may be specified as "Yue" (s[粤] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-s (help); t[粵] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-t (help)). In this article, "Cantonese" is used for Cantonese proper.

Historically, speakers called this variety "Canton speech" or "Guangzhou speech" (s[广州话] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-s (help); t[廣州話] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-t (help),[8]), although this term is now seldom used outside mainland China. In Guangdong province, people also call it "provincial capital speech" (s[省城话] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-s (help); t[省城話] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-t (help))[9] or "plain speech" (s[白话] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-s (help); t[白話] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-t (help)).[10]

In Hong Kong and Macau, as well as among overseas Chinese communities, the language is referred to as "Guangdong speech" (s[广东话] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-s (help); t[廣東話] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-t (help),[11]), "plain speech" (s[白话] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-s (help); t[白話] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-t (help)) or simply "Chinese" (中文,[12]).[13] In mainland China, the term "plain speech" or [白話] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-t (help) is being used.

Due to its status as a prestige dialect among all the dialects of the Cantonese or Yue branch of Chinese varieties, it is often called "Standard Cantonese" (s[标准粤语] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-s (help); t[標準粵語] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: zh-t (help)).[14]

Geographic distribution

Hong Kong and Macau

The official languages of Hong Kong are Chinese and English, as defined in the Hong Kong Basic Law.[15] The Chinese language has many different varieties, of which Cantonese is one. Given the traditional predominance of Cantonese within Hong Kong, it is the de facto official spoken form of the Chinese language used in the Hong Kong Government and all courts and tribunals. It is also used as the medium of instruction in schools, alongside English.

A similar situation also exists in neighboring Macau, where Chinese is an official language along with Portuguese. As in Hong Kong, Cantonese is the predominant spoken variety of Chinese used in everyday life and is thus the official form of Chinese used in the government.

The Cantonese spoken in Hong Kong and Macau is mutually intelligible with the Cantonese spoken in the Chinese city of Canton (Guangzhou), although there exist minor differences in accent and vocabulary. The Cantonese spoken in Hong Kong and Macau is known as Hong Kong Cantonese.

China

Cantonese first developed around the port city of Guangzhou in the Pearl River Delta region of southeastern China. Due to the city's long standing as an important cultural center, Cantonese emerged as the prestige dialect of the Yue varieties of Chinese in the Southern Song dynasty and its usage spread around most of what is now the province of Guangdong.[16]

Despite the cession of Macau to Portugal in 1557 and Hong Kong to Britain in 1842, the ethnic Chinese population of the two territories largely originated from the 19th and 20th century immigration from Guangzhou and surrounding areas, making Cantonese the prominent Chinese variety in the territories. On the mainland, Cantonese continued to serve as the lingua franca of Guangdong and eastern Guangxi province even after Mandarin was made the official language of the government by the Qing Dynasty in the early 1900s.[17] Cantonese remained the dominant language and influential in southeastern China until the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949 and its promotion of Mandarin as the sole official language of the country throughout the mid-20th century.[18]

While the Chinese government discourages the use of all forms of Chinese except Standard Mandarin, Cantonese enjoys a relatively higher standing than other Chinese varieties, with its own media and usage in public transportation in Guangdong province.[19] Furthermore, it is also a medium of instruction in select academic curricula, including some university elective courses and Chinese as a foreign language programs.[20][21] The permitted usage of Cantonese in mainland China is largely a countermeasure against Hong Kong influence, as the territory has the right to freedom of the press and speech and its Cantonese-language media has a substantial exposure and following in Guangdong.[22]

Nevertheless, the place of local Cantonese language and culture remains contentious. A 2010 proposal to switch some programming on Guangzhou television from Cantonese to Mandarin was abandoned following massive public protests, the largest since the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. As a major economic center of China, there have been recent concerns that the use of Cantonese in Guangzhou is diminishing in favour of Mandarin, both through the continual influx of Mandarin-speaking migrants from poorer areas and government policies. As a result, Cantonese is being given a more important status by Guangdong natives than ever before as a common identity of the local people.[23]

Southeast Asia

Cantonese has historically served as a lingua franca among overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia, who speak a variety of other forms of Chinese including Hakka, Teochew and Hokkien.[24] Additionally, Cantonese media and pop culture from Hong Kong is popular throughout the region.

Vietnam

In Vietnam, Cantonese is the dominant language of the ethnic Chinese community, usually referred to as Hoa, which numbers about roughly one million people and constitutes one of the largest minority groups in the country.[25] Over half of the ethnic Chinese population in Vietnam speaks Cantonese as a native language, and the variety also serves as a lingua franca between the different Chinese dialect groups. However, a large number of speakers have been influenced by Vietnamese, and hence speak with a Vietnamese accent or code-switch between Cantonese and Vietnamese.[26]

Malaysia

In Malaysia, Cantonese is widely spoken among the Malaysian Chinese community in Kuala Lumpur,[27] the capital city, and surrounding areas in the Klang Valley and Subang Jaya, the dialect is also widely spoken in the state of Perak especially in the state capital city, Ipoh. Although Hokkien is the most spoken variety of Chinese and Mandarin is the medium of education at Chinese-language schools, Cantonese is largely influential in Chinese language media and is used as a commercial vernacular by Chinese Malaysians in and with regions where Cantonese is prominent.[28]

Due to the popularity of Hong Kong pop culture, especially through drama series, Cantonese is widely understood by the Chinese in all parts of Malaysia, even though a large proportion of the Chinese population is non-Cantonese. Television networks in Malaysia regularly broadcast Hong Kong television programmes in their original Cantonese soundtrack. Cantonese radio is also available in the country and Cantonese is prevalent in locally produced Chinese television.[29][30]

Singapore

In Singapore, Mandarin is the official variety of the Chinese language used by the government, which has a Speak Mandarin Campaign (SMC) seeking to actively promote the use of Mandarin over other Chinese varieties. Cantonese is spoken by a little over 15% of Chinese households in Singapore. Despite the government's active promotion of SMC, the Cantonese-speaking Chinese community has had relative success in preserving its language against Mandarin compared to other dialect groups.[31]

Notably, all nationally produced non-Mandarin Chinese TV and radio programs were stopped after 1979.[32] The prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, then, also stopped giving speeches in Hokkien to prevent giving conflicting signals to the people.[32] Hong Kong (Cantonese) and Taiwanese dramas are unavailable in their untranslated form on Terrestrial TV, though Japanese and Korean drama series are available in their original languages. Cantonese drama series on terrestrial TV channels are instead dubbed in Mandarin and broadcast without the original Cantonese soundtrack. However, originals may be available through other sources such as cable television and video.

Furthermore, an offshoot of SMC is the Pinyinisation of certain terms which originated from southern Chinese varieties. For instance, dim sum is often known as dianxin in Singapore's English-language media, though this is largely a matter of style, and most Singaporeans will refer to dim sum when speaking English.[33]

Nevertheless, since the government restriction on media in non-Mandarin varieties was relaxed in the mid-1990s and 2000s, the presence of Cantonese in Singapore has grown substantially. Forms of popular culture from Hong Kong, such as television dramas, cinema and Cantopop have become popular in Singaporean society, and non-dubbed original versions of the media are widely available. Consequently, there has been a large of number of non-Cantonese Chinese Singaporeans being able to understand or speak Cantonese, with a number of educational institutes offering Cantonese as an elective language course.[34]

Cambodia

Cantonese is widely used as the inter-communal language among Chinese Cambodians, especially in Phnom Penh and other urban areas. While Teochew speakers form the majority of the Chinese population in Cambodia, Cantonese is often used as a vernacular in commerce and with other Chinese variant groups in the country.[35] Chinese-language schools in Cambodia are conducted in both Mandarin and Cantonese.[36]

Thailand

Thailand is home to the largest overseas Chinese community in the world, numbering over 9 million individuals. Cantonese is the fourth most spoken variety of Chinese in Thai Chinese households after Teochew, Hakka and Hainanese.[37] However, within the Thai Chinese commercial sector it serves as a common language alongside Teochew or Thai. Chinese-language schools in Thailand have also traditionally been conducted in Cantonese. Furthermore, Cantonese serves as the lingua franca with other Chinese communities in Southeast Asia.[38]

Indonesia

In Indonesia, Cantonese is locally known as Konghu and is one of the variants spoken by the Chinese Indonesian community, with speakers largely concentrated in major cities such as Batam, Medan and Jakarta. However, it has a relatively minor presence compared to other Southeast Asian countries, being the fourth most spoken Chinese variety after Hokkien, Hakka and Mandarin.[39]

North America

United States

Over a period of 150 years, Guangdong has been the origin of most Chinese emigrants to Western countries; one coastal county, Taishan (or Tóisàn, where the Sìyì or sei yap dialect of Yue is spoken), alone may have been the origin of the vast majority of Chinese immigrants to the U.S. before 1965.[40] As a result, Yue dialects such as Cantonese and the closely related variety of Taishanese have been the major Chinese varieties traditionally spoken in the United States.

The Zhongshan variety of Cantonese, with origins in the Pearl River Delta, is spoken by many Chinese immigrants in Hawaii, and some in San Francisco and the Sacramento River Delta (see Locke, California); it is a Yuehai dialect much like Guangzhou Cantonese, but has "flatter" tones. Chinese is the third most widely spoken non-English language in the United States when both Cantonese and Mandarin are combined, behind Spanish and French.[41] Many institutes of higher education have traditionally had Chinese programs based on Cantonese, with some continuing to offer these programs despite the rise of Mandarin. The most popular romanization for learning Cantonese in the United States is Yale Romanization.[citation needed]

The majority of Chinese emigrants have traditionally originated from Guangdong as well as Hong Kong (beginning in the latter half of the 20th century and before the Handover) and Southeast Asia, with Cantonese as their native language. However, more recent immigrants are arriving from the rest of mainland China and Taiwan and most often speak Standard Mandarin (putonghua/guoyu) as their native language,[42][43] although some may also speak their native local variety, such as Hokkien and other Min Chinese dialects, Wu, Hakka, etc. As a result, Mandarin is becoming more common among the Chinese American community.

The increase of Mandarin-speaking communities has resulted in the rise of separate neighborhoods or enclaves segregated by the primary Chinese variety spoken. Socioeconomic statuses are also a factor as well.[44] For example, in New York City, Cantonese still predominates in the city's Older and Traditional Western Portion of Chinatown in Manhattan and in Brooklyn's small new Chinatowns in sections of Bensonhurst and in Homecrest. The newly emerged Eastern Portion of Manhattan's Chinatown and Brooklyn Main Large Sunset Park Chinatown are mostly populated by Fuzhou speakers, who often speak Mandarin as well. The Cantonese and Fuzhou speaking enclaves in NYC are more working class. Flushing's Large Chinatown, which now holds the crown as the largest Chinatown of NYC and Elmhurst's Smaller Chinatown in Queens are very mixed with large numbers of Mandarin speakers from many different parts of China and Taiwan. They comprise the primary cultural center for NYC's Chinese population and are more middle class.[45] In Northern California, especially in the San Francisco Bay Area, Cantonese has historically and continues to predominate in the Chinatowns of San Francisco and Oakland, as well as the surrounding suburbs and metropolitan area, although Mandarin is now also found in Silicon Valley. In contrast, Southern California hosts a much larger Mandarin-speaking population, with Cantonese found in more historical Chinese communities such as that of Chinatown, Los Angeles and older Chinese ethnoburbs such as San Gabriel, Rosemead and Temple City.[46]

Although a large number of more-established Taiwanese immigrants have learned Cantonese to foster relations with the traditional Cantonese-speaking Chinese American population, more recent arrivals and the larger number of mainland Chinese immigrants have largely continued to use Mandarin as the exclusive variety of Chinese. This has led to a linguistic discrimination that has also contributed to social conflicts between the two sides, with a growing number of Chinese Americans (including American-born Chinese) of Cantonese background defending the historic Chinese American culture against the impacts of increasing Mandarin-speaker arrivals.[44][47]

Canada

Cantonese is the most common Chinese variety spoken among Chinese Canadians. According to the Canada 2011 Census, there were nearly 300,000 Canadian residents who reported Cantonese as their mother tongue. The actual number of Cantonese speakers in the country, however, is thought to be greater as an additional 297,295 people who reported a Chinese mother tongue did not specify the variety spoken.[48]

As in the United States, the Chinese Canadian community traces its roots to early immigrants from Guangdong during the latter half of the 19th century.[49] Later Chinese immigrants came from Hong Kong in two waves, first in the late 1960s to mid 1970s, and again in the 1980s to late 1990s on fears arising from the impending handover to the People's Republic of China. Chinese-speaking immigrants from conflict zones in Southeast Asia, especially Vietnam, arrived beginning in the mid-1970s and were also largely Cantonese speaking. Unlike the United States, recent immigration from mainland China and Taiwan to Canada has been small, and Cantonese still remains the predominant Chinese variety in the country.[50]

Western Europe

United Kingdom

The overwhelming majority of Chinese speakers in the United Kingdom use Cantonese, with about 300,000 British people claiming it as their first language.[51] This is largely due to the presence of British Hong Kongers and the fact that most British Chinese have origins from the former British colonies in Southeast Asia such as Malaysia and Singapore, as well as Guangdong, China.

France

Among the Chinese community in France, Cantonese is spoken by immigrants who fled the former French Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia) following the conflicts and communist takeovers in the region during the 1970s. While a slight majority of ethnic Chinese from Indochina speak Teochew at home, knowledge of Cantonese is prevalent due to its historic prestige status in the region and is used for commercial and community purposes between the different Chinese variety groups. As in the United States, there is a divide between Cantonese-speakers and those speaking other mainland Chinese varieties.[52]

Portugal

Cantonese is spoken by ethnic Chinese in Portugal who originate from Macau, the most established Chinese community in the country with a presence dating back to the 16th century and Portuguese colonialism. Since the late-20th century however, Mandarin and Wu Chinese speaking migrants from mainland China have outnumbered those from Macau, although Cantonese is still retained among mainstream Chinese community associations.[53]

Oceania

Australia

Cantonese has traditionally been the dominant Chinese language of the Chinese Australian community since the first ethnic Chinese settlers arrived in the 1850s.[54] It maintained this status until the mid-2000s, when a heavy increase in immigration from Mandarin-speakers largely from Mainland China led to Mandarin surpassing Cantonese as the dominant Chinese dialect spoken by Chinese Australians. Based on the 2011 census, the Australian Bureau of Statistics lists 336,410 speakers of Mandarin followed by Cantonese at 263,673.

History

During the Southern Song period, Guangzhou became the cultural centre of the region.[16] Cantonese emerged as the prestige dialect of Yue Chinese when the port city of Guangzhou on the Pearl River Delta became the largest port in China, with a trade network stretching as far as Arabia.[55] Cantonese was also used in the popular Yuèōu, Mùyú and Nányīn folksong genres, as well as Cantonese opera.[56][57] Additionally, a distinct classical literature was developed in Cantonese, with Middle Chinese texts sounding more similar to modern Cantonese than other present-day Chinese varieties, including Mandarin.[58]

As Guangzhou became China's key commercial center for foreign trade and exchange in the 1700s, Cantonese became the variety of Chinese interacting most with the Western world.[55] Around this period and continuing into the 1900s, the ancestors of most of the population of Hong Kong and Macau arrived from Guangzhou and surrounding areas after they were ceded to Britain and Portugal, respectively.[59] A popular urban legend claims that after the Xinhai Revolution of 1912, Cantonese almost became the official language of the Republic of China but lost by one vote.[60]

In Mainland China, standard Mandarin has been promoted as the medium of instruction in schools and as the official language, especially after the communist takeover in 1949. Meanwhile, Cantonese has remained the official variety of Chinese in Hong Kong and Macau, both during and after the colonial period.[22]

Cultural role

Spoken Chinese has numerous regional and local varieties, many of which are mutually unintelligible. Most of these are rare outside their native areas, though they may be spoken outside of China. Since a 1909 Qing Dynasty decree, China has promoted Mandarin for use in education, the media and official communication.[61] The proclamation of Mandarin as the official national language however was not fully accepted by the Cantonese authority in the early 20th century, who argued for the "regional uniqueness" of its local dialect and commercial importance of the region.[62] The use of Cantonese in mainland China is unique relative to non-Mandarin Chinese varieties in that it continues to persist in a few state television and radio broadcasts today.

Nevertheless, there have been recent attempts to curb the use of Cantonese in China. The most notable has been the 2010 proposal that Guangzhou Television increase its broadcast in Mandarin at the expense of Cantonese programs. This however led to mass protests in Guangzhou, which eventually dissuaded authorities from enforcing the linguistic switch.[63] Additionally, there have been reports of students being punished for speaking non-Mandarin forms of Chinese at school, resulting in a reluctance of younger children to communicate in their native Chinese variety, including Cantonese.[64] Such actions have further strengthened the role of Cantonese in local Guangdong culture, with the variety being seen as an identity of the province's native people, in contrast to migrants who have generally arrived from poorer areas of China and largely speak Mandarin.[65] In 2014 the station made the switch as planned, but this time without much mass protests.

Due to the linguistic history of Hong Kong and Macau, and the use of Cantonese in most established overseas Chinese communities, international usage of Cantonese is relatively widespread compared to its proportion of speakers who make up the population in China. Cantonese is the predominant Chinese variety spoken in Hong Kong and Macau. In these areas, political discourse takes place almost exclusively in Cantonese, making it the only variety of Chinese other than Mandarin to be used as the primary language for official state functions. Because of their use by non-Mandarin-speaking Yue speakers overseas, Cantonese and Taishanese are the primary forms of Chinese that many Westerners encounter.

Increasingly since the 1997 Handover, Cantonese has been used as a symbol of local identity in Hong Kong, largely through the development of democracy in the territory and desinicization practices to emphasise a separate Hong Kong identity.[66]

A similar identity situation exists in the United States, where social conflicts have arisen within the Chinese American community due to a large recent influx of Mandarin-speakers from Taiwan and China. While many established Taiwanese immigrants have learned Cantonese to foster relations with the traditional Cantonese-speaking Chinese American population, more recent arrivals and the larger number of mainland Chinese immigrants have largely continued to use Mandarin, sometimes as their exclusive language as well rather than attempting to use English. This has contributed to a segregation of communities based on variety of Chinese spoken, as well as a growing number of Chinese Americans (including American-born Chinese) of Cantonese background defending the historic Chinese American culture before the recent arrival of Mandarin-speakers, including dis-identification with China itself in favor of their families' countries of origin (e.g. Hong Kong, Macau, Vietnam, etc.) if not from the mainland.[44][47]

Along with Mandarin and Hokkien, Cantonese has its own popular music, Cantopop. In Hong Kong, Cantonese lyrics predominate within popular music, and many artists from Beijing and Taiwan have learned Cantonese to make Cantonese versions of their recordings.[67] Popular native Mandarin speaking singers, including Faye Wong, Eric Moo, and singers from Taiwan, have been trained in Cantonese to add "Hong Kong-ness" to their performances.[67]

Films were also made in Cantonese from the early days of Chinese cinema, and the first Cantonese talkie, White Gold Dragon (白金龍), was made in 1932 by the Tianyi Film Company.[68] Despite a ban on Cantonese films by the Nanjing authority in the 1930s, Cantonese film production continued in Hong Kong which was then under British colonial rule.[62][69] From the mid-1970s to the 1990s, Cantonese films made in Hong Kong were very popular among overseas Chinese communities.

Phonology

Initials and finals

The de facto standard pronunciation of Cantonese is that of Canton (Guangzhou), which is described in the Cantonese phonology article. Hong Kong Cantonese has some minor variations in phonology, but is largely identical to standard Guangzhou Cantonese.

In Hong Kong and Macau, certain phoneme pairs have caused one sound to merge into another. Although termed as "lazy sound" (懶音) and considered substandard to Guangzhou pronunciation, the phenomenon has been widespread in the territories since the early 20th century. The most notable difference between Hong Kong and Guangzhou pronunciation is the substitution of the liquid nasal (/l/) for the nasal initial (/n/) in many words.[70] An example of this is manifested in the word for you (你), pronounced as néih in Guangzhou and as léih in Hong Kong.

Another key feature of Hong Kong Cantonese is the merging of the two syllabic nasals /ŋ̩/ and /m̩/. This can be exemplified in the elimination of the contrast of sounds between 吳 (Ng, a surname) (ng4/ǹgh in Guangzhou pronunciation) and 唔 (not) (mh4/m̀h in Guangzhou pronunciation). In Hong Kong, both words are pronounced as the latter.[71]

Lastly, the initials /kʷ/ and /kʷʰ/ can be merged into /k/ and /kʰ/ when followed by /ɔː/. An example is in the word for country (國), pronounced in standard Guangzhou as gwok but as gok with the merge. Unlike the above two differences, this merge is found alongside the standard pronunciation in Hong Kong rather than being replaced. Educated speakers often stick to the standard pronunciation but can exemplify the merged pronunciation in casual speech. In contrast, less educated speakers pronounce the merge more frequently.[71]

Less prevalent, but still notable differences found among a number of Hong Kong speakers include:

- Merging of /ŋ/ initial into null initial.

- Merging of /ŋ/ and /k/ codas into /n/ and /t/ codas respectively, eliminating contrast between these pairs of finals (except after /e/ and /o/): /aːn/-/aːŋ/, /aːt/-/aːk/, /ɐn/-/ɐŋ/, /ɐt/-/ɐk/, /ɔːn/-/ɔːŋ/ and /ɔːt/-/ɔːk/.

- Merging of the rising tones (陰上 2nd and 陽上 5th).[72]

Cantonese vowels tend to be traced further back to Middle Chinese back than their Mandarin analogues, such as M. /aɪ/ vs. C. /ɔːi/; M. /i/ vs. C. /ɐi/; M. /ɤ/ vs. C. /ɔː/; M. /ɑʊ/ vs. C. /ou/ etc. For consonants, some differences include M. /ɕ, tɕ, tɕʰ/ vs. C. /h, k, kʰ/; M. /ʐ/ vs. C. /j/; and a greater syllable coda diversity in Cantonese (such as syllables ending in -t, -p, or -k).

Tones

Generally speaking, Cantonese is a tonal language with six phonetic tones.

Historically, finals that end in a stop consonant were considered as "checked tones" and treated separately by diachronic convention, identifying Cantonese with nine tones. However, phonetically these are now considered a conflation of tone and final consonant and are seldom counted as individual tones in modern linguistics.[73]

| Syllable type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tone name | dark flat (陰平) |

dark rising (陰上) |

dark departing (陰去) |

light flat (陽平) |

light rising (陽上) |

light departing (陽去) |

| Description | high level, high falling |

medium rising | medium level | low falling, very low level |

low rising | low level |

| Yale or Jyutping tone number |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Example | 詩 | 史 | 試 | 時 | 市 | 是 |

| Tone letter | siː˥, siː˥˧ | siː˧˥ | siː˧ | siː˨˩, siː˩ | siː˩˧ | siː˨ |

| IPA diacritic | síː, sîː | sǐː | sīː | si̖ː, sı̏ː | si̗ː | sìː |

| Yale diacritic | sī, sì | sí | si | sìh | síh | sih |

Written Cantonese

Cantonese is used primarily in Hong Kong, Macau, and other overseas Chinese communities, so it is usually written with traditional Chinese characters. Cantonese includes extra characters and characters with different meanings from Standard Written Chinese.

Romanization

Cantonese romanization systems are based on the accent of Canton and Hong Kong, and have helped define the concept of Standard Cantonese. The major systems are Meyer–Wempe, the Chinese government's Guangdong Romanization, Yale and Jyutping. While they do not differ greatly, Yale is the one most commonly seen in the west today.[citation needed] The Hong Kong linguist Sidney Lau modified the Yale system for his popular Cantonese-as-a-second-language course and is still widely in use today. The Cantonese romanization systems of Macau are slightly different from Hong Kong's, the spellings are basically influenced by the Portuguese language. However, some words under the Macau's romanization systems are same as Hong Kong's (e.g. Lam 林, Chan 陳). Words with the alphabet "u" under Hong Kong's romanization systems are often replaced by "o" under Macao's romanization systems (e.g. Chau vs Chao 周, Leung vs Leong 梁). Both the spellings of Hong Kong and Macao Cantonese romanization systems do not look similar to the mainland China's pinyin system. Generally, plain stops are written with voiced consonants (/p/, /t/, /ts/, and /k/ as b, d, z/j, and g respectively), and aspirated stops with unvoiced ones.

Early Western effort

Systematic efforts to develop an alphabetic representation of Cantonese began with the arrival of Protestant missionaries in China early in the nineteenth century. Romanization was considered both a tool to help new missionaries learn the variety more easily and a quick route for the unlettered to achieve gospel literacy. Earlier Catholic missionaries, mostly Portuguese, had developed romanization schemes for the pronunciation current in the court and capital city of China but made few efforts to romanize other varieties.

Robert Morrison, the first Protestant missionary in China published a "Vocabulary of the Canton Dialect" (1828) with a rather unsystematic romanized pronunciation. Elijah Coleman Bridgman and Samuel Wells Williams in their "Chinese Chrestomathy in the Canton Dialect" (1841) were the progenitors of a long-lived lineage of related romanizations with minor variations embodied in the works of James Dyer Ball, Ernst Johann Eitel, and Immanuel Gottlieb Genăhr (1910). Bridgman and Williams based their system on the phonetic alphabet and diacritics proposed by Sir William Jones for South Asian languages. Their romanization system embodied the phonological system in a local dialect rhyme dictionary, the Fenyun cuoyao, which was widely used and easily available at the time and is still available today. Samuel Wells Willams' Tonic Dictionary of the Chinese Language in the Canton Dialect (Yinghua fenyun cuoyao 1856), is an alphabetic rearrangement, translation and annotation of the Fenyun. To adapt the system to the needs of users at a time when there were only local variants and no standard—although the speech of the western suburbs, xiguan, of Guangzhou was the prestige variety at the time—Williams suggested that users learn and follow their teacher's pronunciation of his chart of Cantonese syllables. It was apparently Bridgman's innovation to mark the tones with an open circle (upper register tones) or an underlined open circle (lower register tones) at the four corners of the romanized word in analogy with the traditional Chinese system of marking the tone of a character with a circle (lower left for "even," upper left for "rising," upper right for "going," and lower right for "entering" tones). John Chalmers, in his "English and Cantonese pocket-dictionary" (1859) simplified the marking of tones using the acute accent to mark "rising" tones and the grave to mark "going" tones and no diacritic for "even" tones and marking upper register tones by italics (or underlining in handwritten work). "Entering" tones could be distinguished by their consonantal ending. Nicholas Belfeld Dennys used Chalmers romanization in his primer. This method of marking tones was adopted in the Yale romanization (with low register tones marked with an 'h'). A new romanization was developed in the first decade of the twentieth century which eliminated the diacritics on vowels by distinguishing vowel quality by spelling differences (e.g. a/aa, o/oh). Diacritics were used only for marking tones. The name of Tipson is associated with this new romanization which still embodied the phonology of the Fenyun to some extent. It is the system used in Meyer-Wempe and Cowles' dictionaries and O'Melia's textbook and many other works in the first half of the twentieth century. It was the standard romanization until the Yale system supplanted it. The distinguished linguist Y. R. Chao developed a Cantonese adaptation of his Gwoyeu Romatzyh system. The Barnett-Chao romanization system was first used in Chao's Cantonese Primer, published in 1947 by Harvard University Press (The Cantonese Primer was adapted for Mandarin teaching and published by Harvard University Press in 1948 as Mandarin Primer). The BC system was also used in textbooks published by the Hong Kong government.

Cantonese romanization in Hong Kong

An influential work on Cantonese, A Chinese Syllabary Pronounced According to the Dialect of Canton, written by Wong Shik Ling, was published in 1941. He derived an IPA-based transcription system, the S. L. Wong system, used by many Chinese dictionaries later published in Hong Kong. Although Wong also derived a romanization scheme, also known as the S. L. Wong system, it is not widely used as his transcription scheme. This system was preceded by the Barnett–Chao system used by the Hong Government Language School.

The romanization advocated by the Linguistic Society of Hong Kong (LSHK) is called Jyutping, which attempts to solve many of the flaws and inconsistencies of the older, favored, and more familiar system of Yale Romanization, but departs from it in a number of ways unfamiliar to Yale users. The phonetic values of some consonants are closer to the approximate equivalents in Pinyin/IPA than those in Yale. Some effort has been undertaken to promote Jyutping with some official support, but the success of its proliferation within the region has yet to be examined.

Another popular scheme is Cantonese Pinyin, which is the only romanization system accepted by Hong Kong Education and Manpower Bureau and Hong Kong Examinations and Assessment Authority. Books and studies for teachers and students in primary and secondary schools usually use this scheme. But there are teachers and students who use the transcription system of S. L. Wong.

Despite the efforts to standardize Cantonese romanization, those learning the language may feel frustrated that most native Cantonese speakers, regardless of their level of education, are unfamiliar with any romanization system. Because Cantonese is primarily a spoken language and does not carry its own writing system (written Cantonese, despite having some Chinese characters unique to it, primarily follows modern standard Chinese, which is closely tied to Mandarin), it is not taught in schools. As a result, locals do not learn any of these systems. In contrast with Mandarin-speaking areas of China, Cantonese romanization systems are excluded in the education systems of both Hong Kong and the Guangdong province. In practice, Hong Kong follows a loose, unnamed romanization scheme used by the Government of Hong Kong.

Google Cantonese input uses Yale, Jyutping or Cantonese Pinyin, Yale being the first standard.[74][75]

Comparison

Differences between the three main standards are in bold.

Initials

| Yale | Cantonese Pinyin | Jyutping | IPA | Hanyu Pinyin |

| b | b | b | p | b |

| p | p | p | pʰ | p |

| m | m | m | m | m |

| f | f | f | f | f |

| d | d | d | t | d |

| t | t | t | tʰ | t |

| n | n | n | n | n |

| l | l | l | l | l |

| g | g | g | k | g |

| k | k | k | kʰ | k |

| ng | ng | ng | ŋ | |

| h | h | h | h | |

| j | dz | z | ts | z |

| ch | ts | c | tsʰ | c |

| s | s | s | s | s |

| gw | gw | gw | kw | gu |

| kw | kw | kw | kʰw | ku |

| y | j | j | j | y |

| w | w | w | w | w |

Finals

| Yale | Cantonese Pinyin | Jyutping | IPA |

| aa | aa | aa | aː |

| aai | aai | aai | aːi |

| aau | aau | aau | aːu |

| aam | aam | aam | aːm |

| aan | aan | aan | aːn |

| aang | aang | aang | aːŋ |

| aap | aap | aap | aːp |

| aat | aat | aat | aːt |

| aak | aak | aak | aːk |

| ai | ai | ai | ɐi |

| au | au | au | ɐu |

| am | am | am | ɐm |

| an | an | an | ɐn |

| ang | ang | ang | ɐŋ |

| ap | ap | ap | ɐp |

| at | at | at | ɐt |

| ak | ak | ak | ɐk |

| e | e | e | ɛː |

| ei | ei | ei | ei |

| eng | eng | eng | ɛːŋ |

| ek | ek | ek | ɛːk |

| i | i | i | iː |

| iu | iu | iu | iːu |

| im | im | im | iːm |

| in | in | in | iːn |

| ing | ing | ing | eŋ |

| ip | ip | ip | iːp |

| it | it | it | iːt |

| ik | ik | ik | ek |

| o | o | o | ɔː |

| oi | oi | oi | ɔːy |

| ou | ou | ou | ou |

| on | on | on | ɔːn |

| ong | ong | ong | ɔːŋ |

| ot | ot | ot | ɔːt |

| ok | ok | ok | ɔːk |

| u | u | u | uː |

| ui | ui | ui | uːy |

| un | un | un | uːn |

| ung | ung | ung | oŋ |

| ut | ut | ut | uːt |

| uk | uk | uk | ok |

| eu | oeu | oe | œː |

| eung | oeng | oeng | œːŋ |

| euk | oek | oek | œːk |

| eui | oey | eoi | ɵy |

| eun | oen | eon | ɵn |

| eut | oet | eot | ɵt |

| yu | yu | yu | yː |

| yun | yun | yun | yːn |

| yut | yut | yut | yːt |

| m | m | m | m̩ |

| ng | ng | ng | ŋ̩ |

Tones

| Yale | Cantonese Pinyin | Jyutping | IPA | Tone Contour[76] |

| ā, à | 1 | 1 | 55, 53 | ˥, ˥˧ |

| á | 2 | 2 | 35 | ˧˥ |

| a | 3 | 3 | 33 | ˧ |

| àh | 4 | 4 | 21, 11 | ˨˩, ˩ |

| áh | 5 | 5 | 24, 13 | ˩˧ |

| āh | 6 | 6 | 22 | ˨ |

| āk | 7 | 1 | 5 | ˥ |

| ak | 8 | 3 | 3 | ˧ |

| ahk | 9 | 6 | 2 | ˨ |

Loanwords

Life in Hong Kong is characterized by the blending of Asian (mainly south Chinese) and Western influences, as well as the status of the city as a major international business center. Influences from this territory are widespread in foreign cultures. As a result, many loanwords are created and exported to China, Taiwan, and Singapore. Some of the loanwords are even more popular than their Chinese counterparts. At the same time, some new words created are vividly borrowed by other languages as well.

Many Mandarin words originally of foreign origin come from varieties which borrowed them from the original foreign language. The Mandarin word "ningmeng" (檸檬), meaning "Lemon", originated from Cantonese, in which the characters are pronounced as "lìng mung".[77][78]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ "Official Language Division, Civil Service Bureau, Government of Hong Kong". Csb.gov.hk. 2008-09-19. Retrieved 2012-01-20.

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2] Cantonese program at Chinese University of Hong Kong, designating standard Cantonese as 廣東話

- ^ Grasso, J.F. The Everything Speaking Mandarin Book. Foreign Language Study, 2009.

- ^ Cantonese: a comprehensive grammar, p.5, Stephen Matthews and Virginia Yip, Routledge, 1994

- ^ Cantonese as written language: the growth of a written Chinese vernacular, p. 48, Donald B. Snow, Hong Kong University Press, 2004

- ^ Ramsey and Ethnologue, respectively

- ^ Jyutping: gwong2 zau1 waa2; Yale: Gwóngjàu Wah

- ^ Jyutping: saang2 sing4 waa2

- ^ Jyutping: baak6 waa2

- ^ Jyutping: gwong2 dung1 waa2; Yale: Gwóngdūng Wah

- ^ Jyutping: zung1 man2; Yale: Jūngmán

- ^ The Hong Kong Observatory is one of the examples of the Hong Kong Government officially adopting the name "廣東話": Hong Kong Observatory - Audio Web Page

- ^ Jyutping: biu1zeon2 jyut6jyu5; Guangdong Romanization: biu1 zên2 yud6 yu5

- ^ "Basic Law, Chapter I : General Principles".

- ^ a b Yue-Hashimoto (1972), p. 4.

- ^ Coblin (2000), pp. 549–550.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), pp. 3–15.

- ^ "Code of Professional Ethics of Radio and Television Hosts of China" (in Chinese). State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (SARFT). 2005-02-07. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Chinese Language Programme, South China University of Technology

- ^ Chinese Language non-degree program, South China Normal University

- ^ a b Zhang & Yang (2004), p. 154.

- ^ Move to Limit Cantonese on Chinese TV Is Assailed Wong, Edward. The New York Times 26 July 2010.

- ^ West (2010), pp. 289-90

- ^ General Statistics Office of Vietnam. "Kết quả toàn bộ Tổng điều tra Dân số và Nhà ở Việt Nam năm 2009–Phần I: Biểu Tổng hợp". p. 134/882. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Khanh (1993), p. 31

- ^ [3]

- ^ Tze Wei Sim, Why are the Native Languages of the Chinese Malaysians in Decline. Journal of Taiwanese Vernacular, p. 75, 2012

- ^ Malaysian Cantonese

- ^ Tze Wei Sim, Why are the Native Languages of the Chinese Malaysians in Decline. Journal of Taiwanese Vernacular, p. 74, 2012

- ^ Profile of the Singapore Chinese Dialect Groups Lee, Edward Eu Fah. Singapore Department of Statistics, 2000

- ^ a b "http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/singaporelocalnews/view/413581/1/.html". Channelnewsasia.com. 2009-03-06. Retrieved 2012-01-20.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Speak Mandarin Campaign". Mandarin.org.sg. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- ^ Chua, Beng Huat. Life is Not Complete Without Shopping: Consumption Culture in Singapore, 2003, Singapore University Press, pp. 89–90.

- ^ "Cambodia - The Chinese". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- ^ Chan, Sambath. The Chinese Minority in Cambodia: Identity Construction and Contestation, p.34, 2005

- ^ Knodel, John; Ofstedal, Mary Beth; Hermalin, Albert I (2002). "The Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Cultural Context of the Four Study Countries". The Well-Being of the Elderly in Asia: A Four-Country Comparative Study. University of Michigan Press: 38–39.

- ^ Tong, Chee Kiong. Alternate Identities: The Chinese of Contemporary Thailand, 2001, BRILL, pp. 21–25.

- ^ Lewis 2005, p. 391.

- ^ Bryson, Bill. Made In America.

- ^ Lai, H. Mark (2004). Becoming Chinese American: A History of Communities and Institutions. AltaMira Press. ISBN 0-7591-0458-1. need page number(s)

- ^ Mandarin Use Up in Chinese American Communities

- ^ "As Mandarin language becomes standard, Chinatown explores new identity". News.medill.northwestern.edu. Retrieved 2012-01-20.

- ^ a b c Chee Beng Tan (2007). Chinese Transnational Networks. Taylor & Francis. p. 115.

- ^ Semple, Kirk. "In Chinatown, Sound of the Future Is Mandarin." The New York Times. October 21, 2009. p. 2. Retrieved on March 22, 2014.

- ^ Pierson, David (2006-03-31). "Dragon Roars in San Gabriel - Los Angeles Times". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b Him Mark Lai; Hsu, Madeline Y. (2010). Chinese American Transnational Politics. University of Illinois Press. pp. 49–51.

- ^ 2011 Census

- ^ Pierre Berton, The Last Spike, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-011763-6, pp249-250

- ^ Post, National (2012-03-03). "Why is Canada keeping out China's rich?". Canada.com. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ^ "Cantonese speakers in the UK". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2012-01-20.

- ^ [4] Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission, R.O.C.

- ^ de Oliveira, Catarina Reis (July 2003), "Immigrant's Entrepreneurial Opportunities: The Case of the Chinese in Portugal", FEEM Working Papers (75), Portugal: Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei, doi:10.2139/ssrn.464682, retrieved 2009-03-18

- ^ "History of Chinese Australians". Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

- ^ a b Li (2006), p. 126.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1972), pp. 5–6.

- ^ Ramsey (1987), p. 99.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1972), p. 5.

- ^ Yue-Hashimoto (1972), p. 70.

- ^ http://www.scmp.com/article/694592/cantonese-almost-became-official-language

- ^ Minglang Zhou, Hongkai Sun (2004). Language Policy in the People's Republic of China: Theory and Practice Since 1949. Springer. ISBN 978-1402080388.

- ^ a b Yingjin Zhang, ed. (1999). Cinema and Urban Culture in Shanghai, 1922-1943. Stanford University Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0804735728.

- ^ Yiu-Wai Chu (2013). Lost in Transition: Hong Kong Culture in the Age of China. State University of New York Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-1438446455.

- ^ 学校要求学生讲普通话 祖孙俩竟变"鸡同鸭讲" (in Chinese). Yangcheng Evening News. 2010-07-09. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "粵語播音須報准 民轟「弱智」 | 國際新聞 | 蘋果日報". Tw.nextmedia.com. Retrieved 2012-01-06.

- ^ Say It Loud: Language and Identity in Taiwan and Hong Kong, 6 November 2014

- ^ a b Donald, Stephanie; Keane, Michael; Hong, Yin (2002). Media in China: Consumption, Content and Crisis. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 113. ISBN 0-7007-1614-9.

- ^ Hong Kong Connections: Transnational Imagination in Action Cinema. Duke University Press Books. 2006. p. 193. ISBN 978-1932643015.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Lisa Odham Stokes (2007). Historical Dictionary of Hong Kong Cinema. Scarecrow Press. p. 427. ISBN 978-0810855205.

- ^ Matthews, Steven., Yip, Virginia. Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar: 2nd edition (2011), p.4

- ^ a b Matthews, Steven., Yip, Virginia. Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar: 2nd edition (2011), p.37

- ^ Bauer, Robert S.; Cheung, Kwan-hin; Cheung, Pak-man (2003). "Variation and merger of the rising tones in Hong Kong Cantonese". Language Variation and Change. 15 (2): 211–225. doi:10.1017/S0954394503152039.

- ^ Bauer & Benedict (1997:119–120)

- ^ Google Cantonese Input

- ^ [5]

- ^ MATTHEWS, S.; YIP, V. Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar; London: Routledge, 1994

- ^ Lydia He Liu (1995). Translingual practice: literature, national culture, and translated modernity--China, 1900-1937 (illustrated, annotated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 364. ISBN 0-8047-2535-7. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

last car 拉斯卡 lasi ka Shanghainese origin lemon 檸檬 ningmeng Cantonese origin: lihngmung lemonade # MK* ningmeng shui lemon time wmmw ningmeng shijian lepton w&m leibodun Leveler / B»&:£ niweila dang (political party) liaison mm lianyong libido Wc& laibiduo

() - ^ http://ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/elt/article/download/6245/5015

Works cited

- Bauer, Robert S.; Benedict, Paul K. (1997), Modern Cantonese Phonology, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-014893-0.

- Coblin, W. South (2000), "A brief history of Mandarin", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 120 (4): 537–552, doi:10.2307/606615, JSTOR 606615.

- Li, Qingxin (2006), Maritime Silk Road, trans. William W. Wang, China Intercontinental Press, ISBN 978-7-5085-0932-7.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987), The Languages of China, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-01468-5.

- Yue-Hashimoto, Anne Oi-Kan (1972), Studies in Yue Dialects 1: Phonology of Cantonese, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-08442-0.

- Zhang, Bennan; Yang, Robin R. (2004), "Putonghua education and language policy in postcolonial Hong Kong", in Zhou, Minglang (ed.), Language policy in the People's Republic of China: theory and practice since 1949, Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 143–161, ISBN 978-1-4020-8038-8.

Further reading

- Benoni, Lanctot (1867). Chinese and English phrase book : with the Chinese pronunciation indicated in English. San Francisco: A. Roman & Company. OCLC 41220764. OL 13999723M.

- Bridgman, Elijah Coleman (1841). A Chinese Chrestomathy in the Canton Dialect. Macao: S. Wells Williams.

- Matthew, W. (1880). The book of a thousand words: translated, annotated and arranged so as to indicate the radical number and pronunciation (in Mandarin and Cantonese) of each character in the text. Stawell: Thomas Stubbs. OL 13996959M.

- Morrison, Robert (1828). Vocabulary of the Canton Dialect: Chinese words and phrases. Macao: Steyn. OCLC 610578376.

- Williams, Samuel Wells (1856). Tonic dictionary of the Chinese language in the Canton dialect. Canton: Chinese Repository.