Noretynodrel

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Enovid (with mestranol), others |

| Other names | Norethynodrel; Noretinodrel Norethinodrel; NYD; SC-4642; NSC-15432; 5(10)-Norethisterone; 17α-Ethinyl-19-nor-5(10)-testosterone; 17α-Ethynyl-δ5(10)-19-nortestosterone; 17α-Ethynylestr-5(10)-en-17β-ol-3-one; 19-Nor-17α-pregn-5(10)-en-20-yn-17β-ol-3-one |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Progestogen; Progestin; Estrogen |

| ATC code | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | Noretynodrel: to albumin and not to SHBG or CBG[1] |

| Metabolism | Liver, intestines (hydroxylation, isomerization, conjugation)[1][3] |

| Metabolites | • 3α-Hydroxynoretynodrel[2] • 3β-Hydroxynoretynodrel[2] • Norethisterone[2][1][3] • Ethinylestradiol[3][4]• Conjugates[3] |

| Elimination half-life | Very short (< 30 minutes)[5] |

| Excretion | Breast milk: 1%[6] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.620 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H26O2 |

| Molar mass | 298.426 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Noretynodrel, or norethynodrel, sold under the brand name Enovid among others, is a progestin medication which was previously used in birth control pills and in the treatment of gynecological disorders but is now no longer marketed.[3][6][7][8] It was available both alone and in combination with an estrogen.[7][8][9] The medication is taken by mouth.[7]

Noretynodrel is a progestin, or a synthetic progestogen, and hence is an agonist of the progesterone receptor, the biological target of progestogens like progesterone.[3] It is a relatively weak progestogen.[10] The medication has weak estrogenic activity, no or only very weak androgenic activity, and no other important hormonal activity.[3][8][11][12] It is a prodrug of various active metabolites in the body, such as norethisterone among others.[3][13]

Noretynodrel was introduced for medical use in 1957.[8] It was specifically approved at this time in combination with mestranol for the treatment of gynecological and menstrual disorders.[8] Subsequently, in 1960, this formulation was approved for use as a birth control pill.[8][14] It was the first birth control pill to be introduced, and was followed by birth control pills containing norethisterone and other progestins shortly thereafter.[8][14][15] Due to its nature as a relatively weak progestogen, noretynodrel is no longer used in medicine.[10] As such, it is no longer marketed.[6][16]

Medical uses

Noretynodrel was formerly used in combination with the estrogen mestranol in the treatment of gynecological and menstrual disorders and as a combined birth control pill.[8][14] It has also been used in the treatment of endometriosis at high dosages of 40 to 100 mg/day.[17] The medication has been discontinued, and is no longer marketed or used medically.[10][16][18]

Contraindications

No adverse effects have been observed in breastfeeding infants whose mothers were treated with noretynodrel.[6] Because of this, the American Academy of Pediatrics has considered noretynodrel to be usually compatible with breastfeeding.[6]

Side effects

There is a reported case of signs of masculinization in a female infant whose mother was treated with noretynodrel for threatened miscarriage during pregnancy.[6][19][20]

Overdose

Interactions

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Noretynodrel has weak progestogenic activity, weak estrogenic activity, and no or only very weak androgenic activity.[3] It is considered to be a prodrug, and for this reason, the metabolites of noretynodrel play an important role in its biological activity.[3] As such, the pharmacodynamics of noretynodrel cannot be understood without reference to its metabolism.[3]

Noretynodrel is closely related to norethisterone and tibolone, which are the δ4-isomer and the 7α-methyl derivative of noretynodrel, respectively.[2][21] It is metabolized in a very similar manner to tibolone, whereas the metabolism of norethisterone differs.[2] Both noretynodrel and tibolone are transformed into 3α- and 3β-hydroxylated metabolites and a δ4-isomer metabolite (in the case of noretynodrel, this being norethisterone), whereas norethisterone is not 3α- or 3β-hydroxylated (and of course does not form a δ4-isomer metabolite).[2][21] The major metabolites of noretynodrel are 3α-hydroxynoretynodrel and to a lesser extent 3β-hydroxynoretynodrel, formed respectively by 3α- and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (AKR1C1–4), while the δ4-isomer norethisterone is a minor metabolite formed in small amounts.[2]

Tibolone is considered to be a prodrug of both its 3α- and 3β-hydroxylated and δ4-isomerized metabolites.[2] Noretynodrel is also thought to be a prodrug, as it is rapidly metabolized and cleared from circulation and shows very weak relative affinity for the progesterone receptor (PR), although it appears to form norethisterone in only minor quantities.[2][5][13]

| Compound | Code name | PR | AR | ER | GR | MR | SHBG | CBG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noretynodrel | – | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Norethisterone (δ4-NYD) | – | 67–75 | 15 | 0 | 0–1 | 0–3 | 16 | 0 |

| 3α-Hydroxynoretynodrel | – | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 3β-Hydroxynoretynodrel | – | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Ethinylestradiol | – | 15–25 | 1–3 | 112 | 1–3 | <1 | 0.18 | <0.1 |

| Tibolone (7α-Me-NYD) | ORG-OD-14 | 6 | 6 | 1 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Δ4-Tibolone | ORG-OM-38 | 90 | 35 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 3α-Hydroxytibolone | ORG-4094 | 0 | 3 | 4–6 | 0 | ? | ? | ? |

| 3β-Hydroxytibolone | ORG-301260 | 0 | 4 | 3–29 | 0 | ? | ? | ? |

| 7α-Methylethinylestradiol | – | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Notes: Values are percentages (%). Reference ligands (100%) were promegestone for the PR, metribolone for the AR, E2 for the ER, DEXA for the GR, aldosterone for the MR, DHT for SHBG, and cortisol for CBG. Sources: See template. | ||||||||

| Compound | Typea | PR | AR | ER | GR | MR | SHBG | CBG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norethisterone | – | 67–75 | 15 | 0 | 0–1 | 0–3 | 16 | 0 |

| 5α-Dihydronorethisterone | Metabolite | 25 | 27 | 0 | 0 | ? | ? | ? |

| 3α,5α-Tetrahydronorethisterone | Metabolite | 1 | 0 | 0–1 | 0 | ? | ? | ? |

| 3α,5β-Tetrahydronorethisterone | Metabolite | ? | 0 | 0 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 3β,5α-Tetrahydronorethisterone | Metabolite | 1 | 0 | 0–8 | 0 | ? | ? | ? |

| Ethinylestradiol | Metabolite | 15–25 | 1–3 | 112 | 1–3 | 0 | 0.18 | 0 |

| Norethisterone acetate | Prodrug | 20 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ? | ? |

| Norethisterone enanthate | Prodrug | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Noretynodrel | Prodrug | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Etynodiol | Prodrug | 1 | 0 | 11–18 | 0 | ? | ? | ? |

| Etynodiol diacetate | Prodrug | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ? | ? |

| Lynestrenol | Prodrug | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | ? | ? |

| Notes: Values are percentages (%). Reference ligands (100%) were promegestone for the PR, metribolone for the AR, estradiol for the ER, dexamethasone for the GR, aldosterone for the MR, dihydrotestosterone for SHBG, and cortisol for CBG. Footnotes: a = Active or inactive metabolite, prodrug, or neither of norethisterone. Sources: See template. | ||||||||

Progestogenic activity

Noretynodrel is a relatively weak progestogen, with only about one-tenth of the progestogenic activity of norethisterone.[10] The ovulation-inhibiting dosage of noretynodrel is 4.0 mg/day, relative to 0.4 mg/day in the case of norethisterone.[1] Conversely, the endometrial transformation dosage of noretynodrel is 150 mg per cycle, relative to 120 mg per cycle for norethisterone.[1] In terms of the PR, noretynodrel possesses only about 6 to 19% of the affinity of norethisterone for the PRA, whereas the affinity of the two drugs for the PRB is similar (noretynodrel possesses 94% of the affinity of norethisterone for the PRB).[21] Tibolone and the δ4-isomer metabolite of tibolone have similar affinity for the PRs as noretynodrel and norethisterone, respectively, whereas the 3α- and 3β-hydroxylated metabolites of tibolone are virtually devoid of affinity for the PRs.[21] Since the structurally related androgen/anabolic steroid trestolone (7α-methyl-19-nortestosterone) is known to be a potent progestogen,[22] suggesting that a 7α-methyl substitution does not interfere with progestogenic activity, 3α- and 3β-hydroxynoretynodrel likely are devoid of affinity for the PR similarly to the 3α- and 3β-hydroxylated metabolites of tibolone.[21]

Androgenic activity

Noretynodrel has been said to possess no or only very weak androgenic activity.[8][11][12] This is in contrast to norethisterone, which shows mild but significant androgenicity.[8][3] Relative to norethisterone, noretynodrel has 45 to 81% lower affinity for the androgen receptor (AR).[21] In accordance, no androgenic effects (such as hirsutism, clitoral enlargement, or voice changes) have been observed with noretynodrel even when used in large dosages (e.g., 60 mg/day) for prolonged periods of time (9–12 months) in the treatment of women with endometriosis.[23] Additionally, noretynodrel has not been found to virilize female fetuses, in contrast to many other testosterone-derived progestins including ethisterone, norethisterone, and norethisterone acetate.[24] However, at least one case of pseudohermaphroditism (virilized genitalia) has been observed that may have been due to noretynodrel.[20] The δ4-isomer metabolite of tibolone shows dramatically and disproportionately increased affinity for the AR relative to norethisterone and noretynodrel (5.7- to 18.5-fold greater than that of norethisterone), indicating that the 7α-methyl group of tibolone markedly increases its androgenic activity and is responsible for the greater androgenic effects of tibolone relative to noretynodrel.[21]

Estrogenic activity

Noretynodrel, unlike most progestins but similarly to etynodiol diacetate, has some estrogenic activity.[11] Relative to other 19-nortestosterone progestins, noretynodrel is said to possess much stronger estrogenic activity.[5] In the Allen–Doisy test of estrogenicity in animals, noretynodrel has been reported to possess 100-fold greater estrogenic activity than norethisterone.[3] Whereas norethisterone has virtually no affinity for the estrogen receptors (ERs), noretynodrel shows some, albeit very weak affinity for both the ERα and the ERβ (in terms of relative binding affinity, 0.7% and 0.22% of that of estradiol, respectively).[21][25] The estrogenic activity of 3α- and 3β-hydroxynoretynodrel has never been assessed.[2] However, while tibolone shows similar affinity for the ERs as noretynodrel, the 3α- and 3β-hydroxylated metabolites of tibolone have several-fold increased affinity for the ERs.[2][21] As such, the 3α- and 3β-hydroxylated metabolites of noretynodrel may also show increased estrogenic activity, and this may account for the known estrogenic effects of noretynodrel.[2][21]

The δ4-isomer of tibolone, similarly to norethisterone, is virtually devoid of affinity for the ERs.[21] Neither tibolone nor its metabolites are aromatized, whereas trestolone is readily aromatized similarly to testosterone and 19-nortestosterone, and for these reasons, it is unlikely that noretynodrel or its metabolites, aside from norethisterone, are aromatized either.[26] As such, aromatization likely does not play a role in the estrogenic activity of tibolone or noretynodrel.[26] However, controversy on this matter exists, and other researchers have suggested that tibolone and noretynodrel may be aromatized in small amounts to highly potent estrogens (ethinylestradiol and its 7α-methyl derivative, respectively).[27][28]

Pharmacokinetics

Noretynodrel is rapidly absorbed upon oral administration and is rapidly metabolized, disappearing from the circulation within 30 minutes.[29][5] In terms of plasma protein binding, noretynodrel is bound to albumin, and show no affinity itself for sex hormone-binding globulin or corticosteroid-binding globulin.[1] The plasma protein binding of its metabolites, such as norethisterone, may differ however.[3]

The major metabolites of noretynodrel in the circulation are 3α-hydroxynoretynodrel (formed by 3α-HSD) and to a lesser extent 3β-hydroxynoretynodrel (formed by 3β-HSD), and more minor metabolites of noretynodrel are norethisterone (formed by δ5-4-isomerase) and possibly ethinylestradiol (formed by aromatase or possibly other cytochrome P450 enzymes, most likely monooxygenases).[3][2][4][29] Due to its very short elimination half-life and its low affinities for steroid hormone receptors in receptor binding assays, noretynodrel is considered to be a prodrug which is rapidly transformed into its active metabolites in the intestines and liver following oral administration.[1][3][5][13] Some researchers have stated that it is specifically a prodrug of norethisterone.[1][3][13] According to other researchers however, there is, due to a lack of research, insufficient data to unequivocally show this to be the case at present.[13]

About 1% of an oral dose of noretynodrel is detected in breast milk.[6]

The pharmacokinetics of noretynodrel have been reviewed.[30]

Chemistry

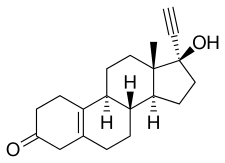

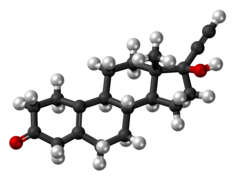

Noretynodrel, also known as 17α-ethynyl-δ5(10)-19-nortestosterone or as 17α-ethynylestr-5(10)-en-17β-ol-3-one, is a synthetic estrane steroid and a derivative of testosterone.[18][31] It is specifically a derivative of testosterone that has been ethynylated at the C17α position, demethylated at the C19 position, and dehydrogenated (i.e., has a double bond) between the C5 and C10 positions).[18][31] As such, noretynodrel is also a combined derivative of nandrolone (19-nortestosterone) and ethisterone (17α-ethynyltestosterone).[18][31] In addition, it is an isomer of norethisterone (17α-ethynyl-19-nortestosterone) in which the C4 double bond has been replaced with a double bond between the C5 and C10 positions.[18][31] For this reason, noretynodrel is also known as 5(10)-norethisterone.[18][31] Few other 19-nortestosterone progestins share the C5(10) double bond of noretynodrel, but examples of a couple that do include tibolone, the C7α methyl derivative of noretynodrel (i.e., 7α-methylnoretynodrel), and norgesterone, the C17α vinyl analogue of noretynodrel.[18][31]

Synthesis

Chemical syntheses of noretynodrel have been published.[31][30]

History

Noretynodrel was first synthesized by Frank B. Colton of G. D. Searle & Company in 1952, and this was preceded by the synthesis of norethisterone by Luis E. Miramontes and Carl Djerassi of Syntex in 1951.[8] In 1957, both noretynodrel and norethisterone, in combination with mestranol, were approved in the United States for the treatment of menstrual disorders.[15] In 1960, noretynodrel, in combination with mestranol (as Enovid), was introduced in the United States as the first oral contraceptive, and the combination of norethisterone and mestranol followed in 1963 as the second oral contraceptive to be introduced.[15] In 1988, Enovid, along with other oral contraceptives containing high doses of estrogen, was discontinued.[32][33]

Noretynodrel was first studied in the treatment of endometriosis in 1961 and was the first progestin to be investigated for the treatment of the condition.[17]

Society and culture

Generic names

Noretynodrel is the INN of the drug while norethynodrel is its USAN and BAN.[6][16][18][31] It is also known by its developmental code name SC-4642.[6][16][18][31]

Brand names

Noretynodrel has been marketed by alone under the brand names Enidrel, Orgametril, and Previson and in combination with mestranol under the brand names Conovid, Conovid E, Enavid, Enavid E, Enovid, Enovid E, Norolen, and Singestol.[9]

Availability

Noretynodrel is no longer available in any formulation in the U.S.,[34] nor does it appear to still be marketed in any other country.[16][18]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kuhl H (September 1990). "Pharmacokinetics of oestrogens and progestogens". Maturitas. 12 (3): 171–97. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(90)90003-O. PMID 2170822.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Jin Y, Duan L, Chen M, Penning TM, Kloosterboer HJ (2012). "Metabolism of the synthetic progestogen norethynodrel by human ketosteroid reductases of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 129 (3–5): 139–44. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.12.002. PMC 3303946. PMID 22210085.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947. S2CID 24616324.

- ^ a b Kuhl H (2011). "Pharmacology of Progestogens" (PDF). J Reproduktionsmed Endokrinol. 8 (1): 157–177.

- ^ a b c d e Hammerstein J (1990). "Prodrugs: advantage or disadvantage?". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 163 (6 Pt 2): 2198–203. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(90)90561-K. PMID 2256526.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Sex hormones and their modulators". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 2120–2121. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ^ a b c Jucker (21 December 2013). Progress in Drug Research / Fortschritte der Arzneimittelforschung / Progrès des recherches pharmaceutiques. Birkhäuser. pp. 85–88. ISBN 978-3-0348-7065-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lara Marks (2010). Sexual Chemistry: A History of the Contraceptive Pill. Yale University Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-0-300-16791-7.

- ^ a b IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Man (1974). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Man: Sex Hormones (PDF). World Health Organization. p. 88,191. ISBN 9789283212065.

- ^ a b c d David A. Williams; William O. Foye; Thomas L. Lemke (January 2002). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 700–. ISBN 978-0-683-30737-5.

- ^ a b c Benno Clemens Runnebaum; Thomas Rabe; Ludwig Kiesel (6 December 2012). Female Contraception: Update and Trends. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-3-642-73790-9.

- ^ a b Ethel Sloane (2002). Biology of Women. Cengage Learning. pp. 426–. ISBN 978-0-7668-1142-3.

- ^ a b c d e Stanczyk, Frank Z. (Sep 2002). "Pharmacokinetics and Potency of Progestins used for Hormone Replacement Therapy and Contraception". Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 3 (3): 211–224. doi:10.1023/A:1020072325818. ISSN 1389-9155. PMID 12215716. S2CID 27018468.

Although there is no convincing evidence for the in vivo transformation of norethynodrel to norethindrone, data from receptor-binding tests and bioassays suggest that norethynodrel is also a prodrug.

- ^ a b c Mannfred A. Hollinger (19 October 2007). Introduction to Pharmacology, Third Edition. CRC Press. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-1-4200-4742-4.

- ^ a b c Enrique Ravina (11 January 2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 190–. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3.

- ^ a b c d e [1][dead link]

- ^ a b Eric J. Thomas; J. Rock (6 December 2012). Modern Approaches to Endometriosis. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 223–. ISBN 978-94-011-3864-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ WILKINS L (March 1960). "Masculinization of female fetus due to use of orally given progestins". Problems of Birth Defects. Vol. 172. pp. 1028–32. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-6621-8_31. ISBN 978-94-011-6623-2. PMID 13844748.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b Korn GW (1961). "The use of norethynodrel (enovid) in clinical practice". Can Med Assoc J. 84: 584–7. PMC 1939348. PMID 13753182.

Pseudohermaphroditism should not be a problem in these patients as it appears that norethynodrel does not possess androgenic properties, but it is believed that Wilkins has now found one such case in a patient who has been on norethynodrel therapy.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k de Gooyer ME, Deckers GH, Schoonen WG, Verheul HA, Kloosterboer HJ (2003). "Receptor profiling and endocrine interactions of tibolone". Steroids. 68 (1): 21–30. doi:10.1016/s0039-128x(02)00112-5. PMID 12475720. S2CID 40426061.

- ^ Beri, Ripla; Kumar, Narender; Savage, T.; Benalcazar, L.; Sundaram, Kalyan (1998). "Estrogenic and progestational activity of 7α-methyl-19-nortestosterone, a synthetic androgen". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 67 (3): 275–283. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(98)00114-9. ISSN 0960-0760. PMID 9879986. S2CID 21302338.

- ^ Kistner RW (1964). "Steroid compounds with progestational activity". Postgrad Med. 35 (3): 225–32. doi:10.1080/00325481.1964.11695038. PMID 14129897.

This difference is important clinically since no androgenic effects (hirsutism, enlarged clitoris, voice change) have been reported even with large dosages of norethynodrel (60 mg. daily) continued from 9 to 12 months in patients with endometriosis.

- ^ Simpson, Joe Leigh; Kaufman, Raymond H. (1998). "Fetal effects of estrogens, progestogens and diethylstilbestrol". In Fraser, Ian S. (ed.). Estrogens and Progestogens in Clinical Practice (3rd ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 533–53. ISBN 978-0-443-04706-0.

- ^ Kuiper GG, Carlsson B, Grandien K, Enmark E, Häggblad J, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA (1997). "Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors alpha and beta". Endocrinology. 138 (3): 863–70. doi:10.1210/endo.138.3.4979. PMID 9048584.

- ^ a b de Gooyer, Marcel E.; Oppers-Tiemissen, Hendrika M.; Leysen, Dirk; Verheul, Herman A.M.; Kloosterboer, Helenius J. (2003). "Tibolone is not converted by human aromatase to 7α-methyl-17α-ethynylestradiol (7α-MEE)". Steroids. 68 (3): 235–243. doi:10.1016/S0039-128X(02)00184-8. ISSN 0039-128X. PMID 12628686. S2CID 29486350.

- ^ Kuhl, H.; Wiegratz, I. (2009). "Can 19-nortestosterone derivatives be aromatized in the liver of adult humans? Are there clinical implications?". Climacteric. 10 (4): 344–353. doi:10.1080/13697130701380434. ISSN 1369-7137. PMID 17653961. S2CID 20759583.

- ^ Kloosterboer, H. J. (2009). "Tibolone is not aromatized in postmenopausal women". Climacteric. 11 (2): 175–176. doi:10.1080/13697130701752087. ISSN 1369-7137. PMID 18365860. S2CID 37940652.

- ^ a b G. Seyffart (6 December 2012). Drug Dosage in Renal Insufficiency. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 423–. ISBN 978-94-011-3804-8.

- ^ a b Die Gestagene. Springer-Verlag. 27 November 2013. pp. 15, 285. ISBN 978-3-642-99941-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 886–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ Reuters News Service (1988-04-15). "Searle, 2 others to stop making high-estrogen pill". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. pp. 7D. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "High-estrogen 'pill' going off market". San Jose Mercury News. 1988-04-15. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 27 November 2016.