User:SheriffIsInTown/Praise and veneration of Prophet Muhammad

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

Praise and veneration of Muhammad has been expressed by various historical personalities including those who lived with Muhammad, Muslim scholars, Muslim mystics, and some non-Muslims. Praise and veneration of Muhammad encompasses a wide-array of formats of expression, including poetry (i.e. naat), Durood, Salawat, literature, speech, and songs. Praise and veneration of Muhammad often focuses on the personality, character, teachings, morality, conduct, actions, way of life, and person of Muhammad.

Islamic Tradition[edit]

Muslims view Muhammad as a sacred personality who should be revered, loved, and respected. Various Muslim personalities have praised Muhammad utilizing a variety of different modalities of expression. Praise of Muhammad can be found by contemporaries of his and throughout history. Throughout history, notable Muslim personalities and Muslims in general have looked up to Muhammad as a role-model and exemplar of divinely appointed morality and conduct. According to Constance E. Padwick, love for the prophet Muhammad is at the heart of the Islamic tradition.[1]

Contemporaries of Muhammad[edit]

| “ | When I saw his light shining forth, |

” |

Muhammad, at an early age was commonly referred to by his contemporaries as al-Amin (faithful, trustworthy) and as-Sadiq (truthful).[2] When Muhammad ventured outside it was common for the people of Makkah to point out Muhammad as al-Amin and as-Sadiq. Muhammad was well known for his righteous and noble character and conduct and according to Martin Lings praise for him was continually on peoples lips.[3] Al-‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib, an uncle of Muhammad, has been described as saying: "And then, when you were born, a light rose over the earth until it illuminated the horizon with its radiance. We are in that illumination and that original light and those paths of guidance and thanks to them we pierce through."[4] Ka'b bin Zuhayr, a poet and contemporary of Muhammad extensively praised Muhammad in his poetry.[5] Hassan ibn Thabit, a Sahaba or companion of Muhammad also praised Muhammad extensively in his poetry. An example of this may be found in the following passage:

By God, no woman has conceived and born

One like the apostle, the prophet of mercy and the guide

Nor has there walked on the surface of the earth

One more faithful to the protection of a neighbor or to a promise

Than he who was the light that shone on us

Blessed in his deeds, just, and rightly guided

—Hassan ibn Thabit[6]

One of the Sahaba or companions of Muhammad, named 'Amr ibn al-'As is reputed to have said "There is no one I love better than the Messenger of Allah."[7] It has been reported that Ali ibn Abi Talib said in regards to Muhammad "By Allah, we loved him more than our wealth, our sons, our fathers and our mothers, and more than cold water in a time of great thirst."[7] Prior to the passing away of Bilal Ibn Rabah, his wife is said to have called out "O sorrow!" Bilal responded with "What joy! I will meet those I love, Muhammad and his party!"[7] Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, who was a staunch enemy of Muhammad said in regards to the Sahaba (companions of Muhammad) "I have not seen any people who love anyone the way the Companions of Muhammad love Muhammad."[7] Abu Sufyan Ibn Harb would later convert to Islam.[7] It is recorded, on a multitude of occasions that the Sahaba sat so attentively around Muhammad, such that they were sitting as if birds were over their heads. Ali ibn Abi Talib also said about Muhammad that "Whoever saw him suddenly was in awe of him."[7] Aisha, the wife of Muhammad said about Muhammad that "his character is the Quran," and "his morals are the Quran."[8] Abdullah ibn Umar is reputed to have said about Muhammad, "I have never seen anybody stronger and braver; more generous and more benevolent, more pure and more radiant."[9] Abd Allah ibn Abbas referred to Muhammad as "the most generous of people."[10] In regards to the birth of Muhammad, Hassan ibn Thabit spoke of "a light which illuminated the whole world" when the Prophet Muhammad was born.[11] When Quraish demanded the handing over of The Holy Prophet to them, His uncle Abu Talib (r.a) has said to have praised him by saying

Shall i make over to you one "who is the refuge of the orphans and protector of the widows"

and when Gibrail came to Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) with first verses of The Holy Quran and he came home to his dear wife Syeda Khadija (r.a), she consoled him with following words

Nay, I call Allah to witness that Allah will never bring thee to disgrace, for thou unitest the ties of relationship and bearest the burden of the weak and earnest for the destitue and honourest the guest and helpest people in real distress.

Islamic History[edit]

Early History[edit]

In the early generations there were Shama'il and Dala'il literatures that were utilized to describe Muhammad's character, life, attributes, and qualities in detail.[13] The Shama'il literatures focused on the beautiful characteristics, lofty qualities, excellent conduct, and attributes of Muhammad. The Dala'il literatures focused on the proofs of prophethood. An example of an early Shama'il literature may be seen in Muhammad ibn Isa at-Tirmidhi's, Shamail al-Mustafa (or Shama'il Muhammadiyah) in which there exists a compilation of hadiths in which Muhammad's appearance, moral superiority, excellent conduct, and astounding character are described.[13] In this book Muhammad is portrayed as an model of moral and ethical perfection.[13] Muqatil ibn Sulayman, an 8th-century mufassir of the Quran idealized Muhammad and wrote about him extensively in his work.[14] The founder of the Maliki school of Sunni Jurisprudence, Malik ibn Anas, would not mount a horse in the Islamic holy city of Madinah and would walk barefooted in the city out of veneration of Muhammad.[15]

Some of the most notable personalities throughout history who extensively praised Muhammad were Sufis. All Sufi orders trace their origins to Muhammad and Sufi personalities have historically revered Muhammad as the greatest of men and a perfect exemplar of the morality of God. According to Carl W. Ernst, devotion to Muhammad is an exceptionally strong practice within Sufism.[16]

Islamic Golden Age[edit]

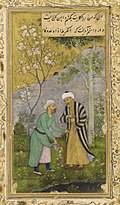

The Islamic Golden Age saw the expansion of Islamic civilization throughout much of the world. By 750 AD, Muslim communities could be found from Al-Andalus in the Iberian Peninsula to China. Praise and veneration of Muhammad has also existed throughout these various communities throughout the Muslim world. Both Muslim philosophers and mystics looked up to Muhammad as their ideal, and many examples of praise and veneration aimed at Muhammad may be found throughout this period. One of the most famous Sufi mystics, Bayazid Bastami, is said to have revered the Sunnah of Muhammad so much that he refused to eat a watermelon as he did not find proof of the Prophet eating one. Similarly, philosopher Ibn Sina, referred to Muhammad as "our lord, and our master"[17] and according to Frank Griffel, Ibn Sina is outspoken about the qualities, virtues, and merits of Prophet Muhammad in his works.[18] Praise and veneration can also be found across the Muslim world during this period from Al-Andalus to South Asia. Figures such as the Andalusian Polymath, Lisan ad-Din ibn al-Khatib stated that he was incapable of praising the greatness of the Prophet Muhammad since the holy book (Quran) praised him.[19] In Persia, Al-Biruni, who is considered to be one of the greatest scientists during this period was a staunch believer in the doctrine of the Perfect Man (Al-Insān al-Kāmil), in which Muhammad is seen as the primary perfect man who exemplifies pure divine morality and who is the apex of humanity and creation.[20] Similarly during this period, figures all the way in South Asia in the court of the Delhi Sultanate also praised Muhammad. Various other examples by notable Muslim personalities may be found throughout history. Examples of these may be seen in Mansur Al-Hallaj, Omar Khayyam, Abdul-Qadir Gilani, Sanai, Qadi Ayyad, Fariduddin Attar, Ibn Arabi, Jalaluddin Rumi, Saadi Shirazi, Al-Busiri, Yunus Emre, Amir Khusrow, Abd al-Karim al-Jili, and Jami.

Mansur Al-Hallaj[edit]

| “ | "All knowledge is but a drop from his [Muhammad's] ocean, and all wisdom is but a handful from his stream, and all times are but an hour from his life." | ” |

Mansur Al-Hallaj, one of the most famous Sufi personalities praised Muhammad extensively in his Kitab at-Tawasin.[22] According to Mansur Al-Hallaj all created beings exist from the light of the Prophet Muhammad.[22] Mansur Al-Hallaj maintains the belief that God created all things for the sake of Prophet Muhammad.[22] According to Hallaj, Prophet Muhammad is both the cause and goal of creation.[22] Al-Hallaj praises the various attributes of Prophet Muhammad such as his wisdom, knowledge, intellect, power, strength, virtue, nobility, honor, status, righteousness, purity and character of Prophet Muhammad.[23] In his Kitab at-Tawasin, Al-Hallaj makes note of Prophet Muhammad's closeness to Allah.[21] Mansur Al-Hallaj describes his supremacy over creation by stating:

His [Muhammad's] aspiration preceded all other aspirations, his existence preceded nothingness, and his name preceded the Pen, because he existed before all peoples. There is not in the horizons, beyond the horizons or below the horizons, anyone more elegant, more noble, more knowing, more just, more fearsome, or more compassionate, than the subject of this tale. He is the leader of created beings, the one "whose name is glorious Ahmad"[Quran 61:6]. - Mansur Al-Hallaj[24]

Ali Hujwiri[edit]

Ali Hujwiri was a major figure in the spread of Islam in the South Asian Sub-Continent. Hujwiri's book, Kashf ul Mahjoob (Revelation of the Veiled), is seen as a major work in Islamic spirituality.[25] Hujwiri relates the accounts of various Sufi shaykhs and his book gives great insight into the lifestyles of Sufis in the 11th century.[25] Throughout Hujwiri's book, Muhammad is seen as the central figure of attaining success in this world and the next. Hujwiri describes in his book of a personal encounter between a Sufi and a Sufi master named Abu Halim Habib Ibn Salim. According to Hujwiri, the Sufi witnessed some miracles, such as a wolf taking care of Ibn Salim's flock of sheep and honey and milk miraculously gushing from some rocks. When Hujwiri asked Salim about how he attained such a state, Ibn Salim responded, "by obedience to Muhammad, the Apostle of God. O my son! the rock gave water to the people of Moses [Koran vii: 160], although they disobeyed him, and although Moses is not equal in rank to Muhammad: why should not the rock give milk and honey to me, inasmuch as I am obedient to Muhammad, who is superior to Moses?"[25]

Omar Khayyam[edit]

Omar Khayyam revered Muhammad as demonstrated by his writings. In his book entitled On the elaboration of the problems concerning the book of Euclid he refers to the Prophet Muhammad as "master of prophets."[26] In the same book, Khayyam at the end of it affirms what he stated and praises God and Prophet Muhammad.[26] In his piece entitled On Existence Khayyam refers to Prophet Muhammad as his master.[27] In his Quatrains, Khayyam asks Prophet Muhammad to admit him into heaven.[28] Khayyam states about Muhammad:

O Thou! to please whose love and wrath as well,

Allah created heaven and likewise hell;

Thou hast thy court in heaven, and I have naught,

Why not admit me in thy courts to dwell?[28]

Abdul-Qadir Gilani[edit]

Abdul-Qadir Gilani has praised and venerated Muhammad extensively in his writings. As the founder of the largest Sufi order, the Qadiriyya, Gilani's spiritual practices have had a great impact on the Sufi traditions. One such practice that Gilani taught his followers was to recite the ninety-nine names of Prophet Muhammad everyday and every night, as to be safeguarded from affliction and to keep their faith strong.[29]

Gilani states about Muhammad:

"He has been glorified by all glorious qualities; he was granted all words. By his noble nature the props of the tent of the whole of existence stay firmly placed; he is the secret of the word of the book of the angel, the meaning of the letters "creation of the world and the heavens"; he is the pen of the Writer Who has written the growing of created things; he is the pupil in the eye of the world, the master who has smithed the seal of existence. He is the one that suckles at the teats of revelation, and carries the eternal mystery; he is the translator of the tongue of eternity. He carries the banner of honor and keeps the reins of praise; he is the central pearl in the necklace of prophethood and the gem in the diadem of messengers. He is the first according to the cause, and the last in existence. He was sent with the Greatest namus to tear the veil of sorrow, to make the difficult easy, to push away the temptation of the hearts, to console the sadness of the spirit, to polish the mirror of the souls, to illuminate the darkness of the hearts, to make rich those who are poor in heart and to loosen the fetters of the souls."[30]

Sanai[edit]

Sanai in his Hadiqatu'l-Haqiqat, makes reference to Muhammad throughout his book.[31] Sanai devotes a significant aspect of his writings to the praise and veneration of Prophet Muhammad. Sanai states about Muhammad:

"To speak any word but your name

Is error, is error;

To sing any artistic praise but for you

Is shame, is shame!"[32]

Sanai had made a major contribution to the naat genre of poetry.[32] One of the greatest odes in the Persian language by Sanai may be seen in his tafsir or commentary on the Quran's Surah Ad-Duhaa (93rd chapter of the Quran) and Surah Al-Layl (92nd chapter of the Quran).[32] Sanai expresses that attributes of God, such as Jalal (Majesty) are manifest through the Prophet Muhammad and that the Prophet Muhammad is key in preserving faith and inhibiting infidelity (kufr). Sanai's poetry in praise and veneration of Prophet Muhammad had a great impact on later poets such as Nizami and Muhammad Iqbal.[32] Sanai asserts the superiority of Prophet Muhammad over creation, as evident in the following passage:

"I asked the wind: "Why do you serve Solomon?"

It said: "Because Ahmad's name is engraved on his seal!"[33]

Qadi Ayyad[edit]

Qadi Ayyad, in his book Ash-Shifa, relates various hadiths of Muhammad as well as accounts about Muhammad by various contemporaries of Muhammad.

Qadi Ayyad states about Muhammad:

"God has elevated the dignity of His Prophet and granted him virtues, beautiful qualities and special prerogatives. He has praised his high dignity so overwhelmingly that neither tongue nor pen are sufficient [to describe him]. In His book He has clearly and openly demonstrated his high rank and praised him for his qualities of character and his noble habits. He asks His servants to attach themselves to him and to follow him obediently. It is God—great is His Majesty!—who grants honor and grace, who purifies and refines, He that lauds and praises and grants a perfect recompense... He places before our eyes his noble nature, perfected and sublime in every respect. He grants him perfect virtue, praiseworthy qualities, noble habits and numerous preferences. He supports his message with radiant miracles, clear proofs, and apparent signs."[34]

Fariduddin Attar[edit]

| “ | ” | |

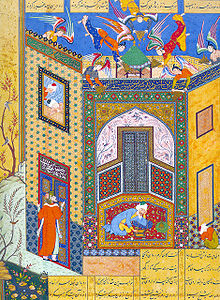

Fariduddin Attar, considered to be one of the greatest Persian poets and Sufi personalities claimed to have praised Muhammad in a way that no other poet had previously done, in his book the Ilahi-nama.[36] Many of Attar's works focus on the praise and veneration of Muhammad. In his book The Conference of the Birds, Attar describes a story of a deeply distressed Shaykh named Sam'an who is pressured by the Christian woman he loves to do certain acts that are forbidden in Islam. In the story, the Shaykh's followers ask Prophet Muhammad for help and the Prophet Muhammad helps Sam'an, thus bringing him back to Islam.[37] A main focus of the story is the ability of Prophet Muhammad to intercede and help those in need, even those born long after him.

Fariduddin Attar states:

"Muhammad is the exemplar to both worlds, the guide of the descendants of Adam.

He is the sun of creation, the moon of the celestial spheres, the all-seeing eye;

The torch of knowledge, the candle of prophecy, the lamp of the nation and the way of the people;

The commander-in-chief on the parade-ground of the Law; the general of the army of mysteries and morals;

The lord of the world and the glory of 'But for thee'; ruler of the earth and of the celestial spheres..."[36]

Attar also states:

Nizami[edit]

According to Gholamreza Aavani, a main theme for nearly all traditional Persian poets is the glorification and praise of the prophet Muhammad.[39] Considered by many to be one of the greatest poets of Persian literature, a main focus of Nizami has been the praise and veneration of Muhammad in his writings. In regards to the night journey of Muhammad, Isra and Mi'raj, Nizami has written in his epics in vivid and very artistic details about the journey.[40] Nizami has borrowed, from Sanai, the approach of juxtaposing the qualitites and attributes of the Prophet, which he regards as majestic and beautiful.[41] According to Annemarie Schimmel, Nizami was one of the greatest non-mystical panegyrists of the Prophet in Persian history and he had a significant impact on the naa'tiyya genre of poetry.[42] An example of the clear devotion of Nizami to the praise and veneration of the Prophet may be seen in his "Khusro and Shirin", where he states about the Prophet, "Your sandals are the crown for the Throne's seat,"[43] which is in clear reference to Muhammad's visit to the throne of Allah during Isra and Mi'raj journey. Another example may be seen in Nizami's explanation of the name "Ahmad."

Straight like an alif in faithfulness to the covenant

The first and last of the prophets.[44]

Ibn Arabi[edit]

Ibn Arabi the Andalusian Sufi mystic and thinker makes mention of Muhammad throughout his works.[45] Ibn Arabi expressed that Muhammad is the Perfect Man (Al-Insān al-Kāmil) by which God makes himself known to the world. According to the concept of the Al-Insān al-Kāmil, Muhammad is the apex or peak of humanity and all other lesser men can only attain a state of spiritual perfection through the Prophet Muhammad.[46] According to Ibn Arabi, Prophet Muhammad is the first and final prophet.[45] Ibn Arabi expressed that Prophet Muhammad's tastes and attributes are such that he loves only that which is good and pure and dislikes that which is evil and impure.[45] Ibn Arabi refers to Muhammad as the overseer of the Muslim nation and the master of all of the sons of Adam.[47] Ibn Arabi states in his Fusus Al Hikam:

"Muhammad's wisdom is uniqueness (fardiya) because he is the most perfect existent creature of this human species. For this reason, the command began with him and was sealed with him. He was a Prophet while Adam was between water and clay, and his elemental structure is the Seal of the Prophets.[45]

According to Ibn Arabi, Islam is the best religion because of Muhammad.[48] Ibn Arabi regards that the first entity that was brought into existence is the reality or essence of Muhammad (al-haqiqa al-Muhammadiyya).[48] Ibn Arabi regards Muhammad as the supreme human being and master of all creatures. Muhammad is therefore the primary role-model for human beings to aspire to emulate. Ibn Arabi believes that God's attributes and names are manifested in this world and that the most complete and perfect display of these divine attributes and names are seen in Muhammad. Ibn Arabi believes that one may see God in the mirror of Muhammad, meaning that the divine attributes of God are manifested through Muhammad.[48] Ibn Arabi maintains that Muhammad is the best proof of God and by knowing Muhammad one knows God.[48] Ibn Arabi also maintains that Muhammad is the master of all of humanity in both this world and the afterlife. In Ibn Arabis view, Islam is the best religion, because Muhammad is Islam.[48]

Ibn al-Jawzi[edit]

Ibn al-Jawzi, wrote about the birth of Muhammad in his maulid book. Ibn al-Jawzi states:

When Muhammad was born, angels proclaimed it with high and low voices. Gabriel came with the good tidings, and the Throne trembled. The houris came out of their castles, and fragrance spread. Ridwan [the keeper of the gates of Paradise] was addressed: "Adorn the highest Paradise, remove the curtain from the palace, send a flock of birds from the birds of Eden to Amina's dwelling place that they may drop a pearl each from their beaks." And when Muhammad was born, Amina saw a light, which illuminated the palaces of Bostra. The angels surrounded her and spread out their wings. The rows of angels, singing praise, descended and filled hill and dale.[49]

Jalaluddin Rumi[edit]

| “ | ” | |

Rumi has extensively praised Muhammad throughout his life, in his Masnavi and his Diwan. When Rumi became spiritually intoxicated he would whirl around and recite: "O God, pour blessings upon Muhammad and upon the family of Muhammad."[51] The practice of Sama, in which Rumi has been a major practitioner of, traditionally begins with na't i-sharif, or poetry praising Muhammad.[52] Rumi regards the spiritual influence of Muhammad to wipe out ignorance, unbelief (kufr), and polytheism.[53] Rumi asserts the importance of all Muslims to establish a connection with Muhammad and goes as far as saying that "Following (the example of) the holy Prophet of God [Muhammad] is among all the required duties for the people of spiritual reality" and "The Sufi is hanging on to Muhammad, like Abu Bakr."[54][55] Rumi regards Muhammad as a perfect role-model.

In regards to the Islamic holy city of Medina, in which Muhammad lived and is buried, Rumi states:

| “ | "I "sewed" my two eyes shut from [desires for] this world and the next - this I learned from Muhammad." | ” |

Rumi also states:

"O God's beloved [Muhammad], O messenger of God - unique are you!

You, chosen by the Lord of Majesty - so pure are you!"[58]

Saadi Shirazi[edit]

| “ | ” | |

Saadi Shirazi displayed great reverence to Muhammad in his poetry. Shirazi has placed a great emphasis on utilizing the Quran and Sunnah in his poetry, when praising Muhammad.[60] Shirazi places a great deal of emphasis on following Muhammad and recognizing him as the right guide and teacher. Shirazi states: "He who chooses a path contrary to that of the prophet [Muhammad] shall never reach the destination. O Saadi, do not think that one can tread that way of purity except in the wake of the Chosen one [Muhammad]."[61] Shirazi has had a major influence on the tradition of naat and his influence can be found throughout naat performers from a variety of diverse backgrounds. Shirazi states: "If you are in search of true wisdom, go to the threshold of Muhammad"[62] Shirazi also states:

| “ | ” | |

God made your praise and uttered your glorification

He made Gabriel kiss the threshold of your mystic rank

The lofty heaven is ashamed before your sublime worth

You were created while Adam was being kneaded of water and clay

You were the primordial starting-point of creation

Whatever came into being thence forward was your offshoot and branch[64]

Al-Busiri[edit]

| “ | Muhammad, the lord of the two worlds and of men and djinn, Of the two communities, the Arabs and the non-Arabs. |

” |

Al-Busiri wrote what he called al-Kawākib ad-Durrīya fī Madḥ Khayr al-Barīya (The Celestial Lights in Praise of the Best of Creation), which is commonly known as the Qaṣīdat al-Burda (Poem of the Mantle) across the Islamic world. In this lengthy poem, Al-Busiri praises Muhammad—His character, morality, way of life, traits, personality, and conduct.[67] Al-Busiri's poem demonstrates immense reverence towards Prophet Muhammad and it is widely recognized as a masterpiece of Arabic poetry. Various Muslims, especially Sufi groups commonly recite this poem in their gatherings and this poem has been utilized by various Sufi groups throughout the world, especially those in North Africa and the Middle-East.[68] This poem has been translated into a variety of languages, including Urdu, Swahili, Turkish, Persian and Malay, and is very famous throughout the Muslim world.[68] In his poem, Al-Busiri, refers to Prophet Muhammad as the leader of all creation—The lord of men and jinn.[69] Al-Busiri praises the various noble qualities of Prophet Muhammad and refers to him as the best of the prophets.[69] Al-Busiri claimed that half of his body was paralyzed and that he composed this poem and supplicated to Muhammad, asking him to intercede on his behalf and to cure him of this illness. According to tradition, after writing this poem and following repeated prayers, crying and asking Prophet Muhammad for help Al-Busiri fell asleep and in his sleep, Prophet Muhammad appeared to him in a dream.[67] In this dream Prophet Muhammad covered Al-Busiri in a mantle and when Al-Busiri woke up he was able to walk again.[67]

Al-Busiri's poem consists of 10 chapters and 164 verses all of which are rhyming.[67] The poem would decorated Al-Masjid al-Nabawi and remained there for centuries until the Al-Saud dynasty emerged and destroyed all but two verses of the poem. The Al-Saud dynasty did this in accordance with their Wahhabist beliefs.

Yunus Emre[edit]

Yunus Emre played a major role in the Turkish literary tradition. Emre throughout his life produced a variety of poems praising Muhammad. Major themes present within the poetry of Emre focus on Mevlüt, desire for visiting Madinah, and longing to be in the presence of Prophet Muhammad. An example of this may be seen in his following piece:

"Please pray for us on Doomsday-

Your name is beautiful, you yourself are beautiful, Muhammad!

Your words are accepted near God, the Lord-

Your name is beautiful, you yourself are beautiful, Muhammad!"[70]

Amir Khusrow[edit]

Amir Khusrow is considered to be the "father of qawwali" and he is credited with introducing this style of music.[71] Since its inception, a central theme in the musical style has been on the praise and veneration of Muhammad. Amir Khusrow also composed a variety of poems and literary works. In the beginning passages of his epic compositions of poetry he would praise Muhammad.[42] An example of this may be seen in his story of Layla and Majnun, where in the beginning he states about the Prophet:

"The king of the kingdoms of messengerdom,

The tughra of the page of Majesty."[42]

Abd al-Karīm al-Jīlī[edit]

Abd al-Karīm al-Jīlī, following in the tradition of Ibn Arabi, further elaborated on the concept of the al-insan al-kamil, in which Muhammad is viewed as the ideal man who is the apex of humanity. al-Jili authored a book on the matter with the same title, the Perfect Man (al-insan al-kamil), and also authored another piece about Muhammad, his names, and attributes called The Divine Perfections. In this work al-Jili specifies and describes each of the divine names of Allah as qualities that the Prophet realized. This text addresses both the attributes of God and their relation to Muhammad.[72]

In an invocation to Muhammad, Abd al-Karīm al-Jīlī states:

O perfect one, and perfecter of the most perfect, who has been beautified by the majesty of God the Merciful!

Thou art the Pole (qutb) of the most wondrous things. The sphere of perfection in its solitude turns on thee.

Thou art transcendent, nay thou art immanent, nay thine is all that is known and unknown, everlasting and imperishable.

[73]

Jami[edit]

| “ | ” | |

Jami, who wrote on a wide array of topics in the humanities and religion[74] praised Muhammad extensively in his works.[75] Jami, in his Haft Awrang details the story of Yusuf and Zulaikha.[75][76] In this story, Jami, details a blessed night in which lion and sheep as well as wolf and lamb are together at peace before Muhammad's trip to Jerusalem, the heavens and the throne of Allah, known as Al-Isra Wal Miraj.[75]

Jami says in regards to Muhammad:

Everyone on whom the light of your kindness [or, sun:mihr] shines,

Will become red-faced [honored] in the whole world like the dawn.[77]

Jami also states in his Haft Awrang in regards to Muhammad:

His light appeared on Adam's forehead

So that the angels bowed their heads in prostration;

Noah, in the dangers of the flood,

Found help from him in his seamanship;

The scent of his grace reached Abraham,

And his rose bloomed from Nimrod's pyre.

Yusuf was for him, in the court of kindness

[Only] a slave, seventeen dirhams' worth.

His face lighted the fire of Moses,

And his lip taught Christ how to quicken the dead.[78]

Ottoman and Mughal Empires[edit]

The 16th century saw the expansion of the Ottoman and Mughal empires. Within the empires, Sufis played a considerable role in the spread of Islamic doctrines and ideas. Continuing on from their predecessors, Sufis within the Mughal and Ottoman Empires contributed to various art forms, especially poetry, in which praise and veneration of Muhammad continued to play a central role. Various court poets in the Mughal empire, such as Urfi, have praised Muhammad heavily in their poetry.[79] Similarly, in the Ottoman Empire, figures such as Süleyman Çelebi (an Ottoman prince), wrote Mevlut poetry that described the miraculous birth of Muhammad and praised his attributes, status and character.[80]

Another prominent personality of the Ottoman Empire, Aziz Mahmud Hudayi, has described in his book Khulasat al-bayan (The Summary Explanation) the creation of the world, in which the Prophet Muhammad is described as the ultimate aim of the cosmos.[81] Similarly, Evliya Çelebi, the famous Turkish explorer, is said to have been inspired to undergo his long journeys because of a dream in which he saw Muhammad.[82] In the Mughal Empire, figures such as Ahmad Sirhindi, who was a prominent Muslim scholar, also contributed to the tradition of praise and veneration of Muhammad.[83]

18th-19th Century[edit]

The 18th century saw the stagnation of the Mughal and Ottoman Empires and eventual decline of the empires. During this period the Mughal Empire would disintegrate in to various dominions and Muslim rule in the South Asian Sub-Continent would fall to various kingdoms such as the Kalhora Dynasty in Sindh and the Sultanate of Mysore in Mysore. During this period, Muhammad, would be seen by various personalities as a source of comfort and inspiration. Sarfaraz Khan, a prince of the Kalhora dynasty, wrote an invocation in 1774 addressed to Muhammad while he was imprisoned.[77] Muslim scholars such as Shah Waliullah Dehlawi continued to speak about the miracles of Muhammad[84] and the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar too expressed praise and veneration of Muhammad in his poetry.[41]

Tipu Sultan, known for his sustained efforts against British rule in South Asia and the Padshah of Mysore, minted several coins named after prominent Islamic figures in his mints located at Seringapatam and Bednur.[85] The most valuable of these coins was a gold coin called the ahmadi. The ahmadi was named after Muhammad and weighed approximately 211 grams.[85] Tipu Sultan also introduced a new lunisolar calendar in 1784 called the Mauloodi.[86][87] The calendar starts at the year of the birth of Muhammad, in contrast to the Hijri calendar which starts at the year in which Muhammad travelled from Makkah to Madinah.[87] The first month in the Mauloodi calendar was also called ahmadi and was also named after Muhammad.[86] Tipu Sultan also ordered for a Mosque to be build in 1784, called Masjid e A'la (also known as Jumma Masjid) in Seringapatam. The mosque contained the 99 names of Prophet Muhammad alongside the 99 names of Allah (God).[88]

A large part of Mirza Ghalib's poetry focuses on the praise and veneration of Muhammad.[89] Ghalib wrote his Abr-i gauharbar (The Jewel-carrying Cloud) in honor of Prophet Muhammad.[90] Ghalib also wrote a qasida of 101 verses in dedication to the Prophet.[89] Ghalib described himself as a sinner who should be silent before the Prophet as he was not worthy of addressing the Prophet, who was praised by God.[89]

20th Century[edit]

The 20th century saw the solidification of European colonial powers, the conquest and colonization of many Muslim lands, and the replacement of various Islamic institutions with European ones throughout the conquered lands. During this period of decline of Islamic civilization, movements such as Wahhabism, Salafism and Deobandism opposed what they deemed as the "shirk" or polytheism in the praise and veneration of Muhammad.[91][92][93] These allegations were heavily opposed by figures in the Barelvi movement, such as Ahmad Raza Khan, who insisted that praise and veneration of Prophet Muhammad is an essential aspect of the Islamic religion and that praise and veneration of Prophet Muhammad does not constitute shirk or polytheism, rather it brings one closer to God.[94][95] According to Ahmad Raza Khan, opposing the practice of praise and veneration of Prophet Muhammad is kufr (unbelief). Ahmad Raza Khan upholds the belief that praise and veneration of Prophet Muhammad is in essence praise and veneration of God and is therefore an essential aspect of belief in the oneness of God. Similarly, figures such as Muhammad Iqbal continued on the tradition of previous Muslim mystics and scholars in his strong and committed devotion to the praise and veneration of Muhammad. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, a friend of Muhammad Iqbal and considered to be the founder of Pakistan said "I have one underlying principle in mind: the principle of Muslim democracy. It is my belief that our salvation lies in following the golden rules of conduct set for us by our great lawgiver, the Prophet of Islam."[96] Jinnah is also said to have joined Lincoln’s Inn because he saw the name of Muhammad at the entrance.[97]

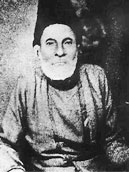

Ahmad Raza Khan[edit]

Ahmad Raza Khan was a staunch opponent of the Wahhabi-inspired Deobandi movement. Khan viewed the doctrines of Deobandism to be an affront to traditional Sunni theology.[98] Khan especially opposed many of the views that Deobandi scholars had about Muhammad. Ahmad Raza Khan wrote many works in praise and veneration of Prophet Muhammad. Due to his immense love for Muhammad, Ahmad Raza Khan was often called "Abd al-Mustafa" (Servant of Mustafa [Muhammad]).[99] An example of Ahmad Raza Khan's poetry in praise and veneration of Prophet Muhammad may be seen in the following translation of his work:

"You are free from the defect of having an end,

I am perplexed my Master! What shall I call thee?

The melodies of Razā echo resoundingly in the gardens

And why not? Does he not sing the praises of the majestic flower?

I will say that, you to be the Master, for you are the beloved of The Master (Allah).

For between the Beloved and One who loves Him, there is no mine and yours."[99]

Muhammad Iqbal[edit]

| “ | There is a beloved hidden within thine heart: |

” |

Muhammad Iqbal's praise and veneration of Muhammad encompasses a variety of different writing styles. Iqbal sees Muhammad as the central figure of a Muslim's spiritual life and as a dynamic figure who reveals himself in a variety of different facets.[101] Iqbal's veneration of Muhammad has been described as so intense that he used to often shed tears when the Prophet Muhammad was mentioned.[102] Iqbal viewed Muhammad as the primary figure whom Muslims within South Asia should unite under.[102] A major theme of Iqbal's writings in regards to Muhammad is his absolute trust in him.[102] Iqbal's belief in the supernatural powers of Muhammad were strong and he would often seek out support and aid from Prophet Muhammad.[103] Iqbal saw Muhammad as the "visible aspect of God's activity" and believed he was unworthy of pronouncing the name of Muhammad, as he regarded Muhammad's name as being so highly sacred and holy.[103] In the fall of 1932, after seeing the cloak of Muhammad (called Khirqa-i Sharif) in Kandahar, Afghanistan, Iqbal was inspired to compose a fine Persian hymn.[104] Iqbal in this piece compared his heart to that of the angel Gabriel's when he saw Muhammad physically.[104]

Prophet Muhammad to Iqbal was the source of all good and meaningful in human life.[105] In his famous piece called Jawab-i Shikwa, Iqbal concludes by stating that Muslims must be faithful to Prophet Muhammad if they wish to rise as a major world power again. Iqbal recounts a series of spiritual exchanges between him and notable Muslim mystics like Mansur al-Hallaj in his Javidnama. In this encounter Al-Hallaj reveals to Iqbal various mysteries of the Prophet Muhammad and describes his perfection.[106] Iqbal's concept of the mard-i momin - or an ideal man, is a status that can only be attained by emulating the Prophet Muhammad.[106] Alongside the mystical and supernatural qualities of Prophet Muhammad, Iqbal, placed great emphasis on the political and social role of the Prophet Muhammad.[107] Iqbal strongly criticized Muslims who neglected this aspect of the Prophet Muhammad's life, when he said: "That kind of prophethood is hashish for the Muslim; In which there is not the message of power and energy!"[107] According to Iqbal, the mystic who secludes himself to a retired life away from civilization is seduced by Satan.[107] Iqbal maintains that ambition and action are traits demonstrated by the Prophet Muhammad and that the Prophet Muhammad brought creative and positive changes to the world.[108] Iqbal viewed European orientalist depictions of Prophet Muhammad as utterly repellent and strongly opposed European orientalists like Aloys Sprenger whom Iqbal regards as having unjustly and dishonestly made claims about Prophet Muhammad.[108] Iqbal also strongly opposed Qadianis and their leader Mirza, who claimed to be a prophet.[109] Iqbal states on this matter "For us, Mustafa is enough." Iqbal strongly supported the idea of the finality of prophethood as being a quality attributed to Prophet Muhammad alone.[109]

Iqbal states in regards to Muhammad:

"We are like a rose with many petals but with one perfume:

He is the soul of the society, and he is one."[110]

Iqbal also states:

"The caravan leader for us is the prince of Hijaz,

By his name our soul acquires peace!"[111]

Non-Muslims[edit]

Sino-Confuscian Civilization[edit]

Du Huan a Chinese traveler and writer of the Tang Dynasty said in an early account that the Prophet governed with virtue.[112] Islam is said to have been preached in China by a relative of Muhammad himself, Sa`d ibn Abi Waqqas. Muslims have made up a significant part of the Chinese population ever since. During the Ming Dynasty Muhammad was seen by the Chinese Emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang, as the leader of holy figures and as a guide to all creations. Yuanzhang viewed the Prophet Muhammad as a sage and declared that the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad should be preserved for future generations.[113] Yuanzhang had great reverence and admiration for the Prophet Muhammad. Zhu Yuanzhang would compose a poem in praise of Prophet Muhammad, which consists of 100 words in Chinese.[114] Yuanzhang would also add inscriptions praising the Prophet in mosques across China. During the Qing Dynasty, veneration and acceptance of Prophet Muhammad as a sage would continue within the imperial court.[115] Zhu Yuanzhang, states about Muhammad:

| Chinese Text | English Translation |

|

至聖百字讃 |

"Since the creation of the universe |

Western Civilization[edit]

In Christendom during the Middle-Ages, Christian perspectives of Muhammad were often negative. However, during the Enlightenment and after it, more positive perspectives were expressed in greater frequency and detail. An example of a positive outlook of Muhammad from the West may be seen in Alphonse de Lamartine's writings:

"If greatness of purpose, smallness of means, and astounding results are the three criteria of human genius, who could dare to compare any great man in modern history with Muhammad? The most famous men created arms, laws and empires only. They founded, if anything at all, no more than material powers, which often crumbled away before their eyes. This man moved not only armies, legislation, empires, peoples and dynasties, but millions of men in one-third of the then-inhabited world; and more than that he moved the altars, the gods, the religions, the ideas, the beliefs and souls.... His forbearance in victory, his ambition which was entirely devoted to one idea and in no manner striving for an empire, his endless prayers, his mystic conversations with God, his death and his triumph after death - all these attest not to an imposture, but to a firm conviction, which gave him the power to restore a dogma. This dogma was two fold: the unity of God and the immateriality of God; the former telling what God is, the latter telling what God is not; the one overthrowing false gods with the sword, the other starting an idea with the words. Philosopher, orator, apostle, legislator, warrior, conqueror of ideas, restorer of rational beliefs, of a cult without images; the founder of twenty terrestrial empires and of one spiritual empire, that is Muhammad. As regards all standards by which human greatness may be measured, we may well ask, is there any man greater than he."

Such perspectives of Muhammad often involve a re-examination and re-evaluation of previously held ideas that have historically been embedded in Western societies about Muhammad. Thomas Carlyle, for example, criticized Western slanderers for inaccurately describing Muhammad, Carlyl states "The lies which well-meaning zeal has heaped round this man are disgraceful to ourselves only."[117]

John William Draper, the American scientist stated: "Four years after the death of Justinian, A.D. 569, was born at Mecca, in Arabia, the man who, of all others has exercised the greatest influence upon the human race-Mohammed..."[118] Bosworth Smith (1839–1908) stated: "He was Caesar and Pope in one; but he was Pope without Pope's pretensions, Caesar without the legions of Caesar: without a standing army, without a bodyguard, without a palace, without a fixed revenue; if ever any man had the right to say that he ruled by the right divine, it was Mohammed, for he had all the power without its instruments and without its supports. He rose superior to the titles and ceremonies, the solemn trifling, and the proud humility of court etiquette..."[119] Bosworth Smith, however, asserts the superiority of Christianity, by stating: "Assuredly, if Christian missionaries are ever to win over Mohammedans to Christianity, they must alter their tactics. It will not be by discrediting the great Arabian Prophet, nor by throwing doubts upon his mission, but by paying him that homage which is his due; by pointing out, not how Mohammedanism differs from Christianity, but how it resembles it..."[120]

The attitude various Western thinkers have had towards Muhammad has been met with aversion and disgust by Muslim communities. Annemarie Schimmel states in this respect, "From the nineteenth century onward Western scholars began to study the classical Arabic sources, which hence-forward slowly became available in Europe. However, even during that period biographies of the Prophet were often marred by prejudices and in no way did justice to the role of the Prophet as seen by pious Muslims. It is understandable that the Muslims reacted with horror to the European image of their beloved Prophet, with which they became acquainted, particularly in India, through British educational institutions and missionary schools. Small wonder that they as Muslims loathed this Christian attitude, which contrasted so markedly with the veneration they were wont to show to Jesus, the last prophet before Muhammad, and to his mother the Virgin. This encounter with such a distorted image of the Prophet is one of the reasons for the aversion of at least the Indian Muslims to the British."[121]

Although more positive perspectives of Prophet Muhammad from Western thinkers have been expressed, they can not, however, be compared to the devotion, commitment, and immense love that Muslim thinkers, scholars, and mystics have had for the Prophet Muhammad, whom they regard as an exemplar of pure and perfect morals and guidance.

Dharmic sources[edit]

Rana Bhagwandas, a Hindu, and former Chief Justice of Pakistan "wrote poetry and a book in praise of the Holy Prophet (pbuh)."[122] Nanak, a major figure in the Sikh religion is also reputed to have said "I have seen the light of Muhammad (with my mind's eye). I have seen the prophet and the messenger of God, in other words, I have understood his message or imbibed his spirit. After contemplating the glory of God, my ego was completely eliminated."[123] Similarly Gandhi said "I wanted to know the best of the life of one (Muhammad) who holds today an undisputed sway over the hearts of millions of mankind. I became more than ever convinced that it was not the sword that won a place for Islam in those days in the scheme of life. It was the rigid simplicity, the utter self-effacement of the Prophet, the scrupulous regard for pledges, his intense devotion to his friends and followers, his intrepidity, his fearlessness, his absolute trust in God and in his own mission. These and not the sword carried everything before them and surmounted every obstacle."[124]

Jewish sources[edit]

Michael H. Hart considers The Holy Prophet as the most influential person in history of mankind in his book The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History.[125]

Greatest lawgiver[edit]

Lincoln's Inn depicts Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) as one of the greatest lawgivers of history in a painting at it's dining hall.[97]

The Supreme Court of the United States includes The Holy Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) among the greatest lawgivers of history using a sculpted image.[126]

References[edit]

- ^ Ali S. Asani, Kamal Abdel-Malek (1995), Celebrating Muhammad (PDF), University of South Carolina Press, p. 1

- ^ Muhammad AbdulRaoof (1999), Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) A Blessing For Mankind, IIPH, p. 10, ISBN 9960-672-89-1

- ^ Martin Lings, Muhammad - His Life Based on the Earliest Sources, Inner Traditions, p. 41, ISBN 978-1-59477-153-8

- ^ Muhammad Hisham Kabbani, Remembrance of Allah and praising the Prophet - Volume 2, Kazi Publications, p. 120

- ^ Encyclopedia of Arabic Literature, Volume 2, Routledge, 1998, p. 421, ISBN 0-415-18572-6

- ^ Jennifer Hill Boutz (2009), HASSĀN IBN THĀBIT, A TRUE MUKHADRAM:A STUDY OF THE GHASSĀNID ODES OF HASSĀN IBN THĀBIT, Georgetown University, p. 40

- ^ a b c d e f Qadi 'Iyad (2013), Muhammad - Messenger of Allah, Ash-Shifa of Qadi Iyad, Aisha Bewley (translator), Diwan Press, ISBN 1908892277

- ^ Hanif D. Sherali (2014), Spiritual Discourses, AuthorHouse LLC, p. 87, ISBN 978-1-4918-5179-1

- ^ Sunan Darmi, Vol. 1, P.30

- ^ Riyad As Salihin, 1222

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel (1985), And Muhammad is his Messenger - The Veneration of the Prophet in Islamic Piety, The University of North Carolina Press, p. 149, ISBN 0-8078-1639-6

- ^ Mohammad Ali Jouhar (2011), The Living Thoughts of the Prophet Muhammad, Ahmadiyya Anjuman Ishaat Islam, Lahore, ISBN 1934271225

- ^ a b c Schimmel (1985), p.33

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel (1975), Mystical Dimensions of Islam, The University of North Carolina Press

- ^ I. M. N. Al-Jubouri (2010), Islamic Thought: From Mohammed to September 11, 2001, Xlibri Corporation, p. 117, ISBN 978-1-4535-9585-5

- ^ Carl W. Ernst (2010), The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad, Muḥammad as the Pole of Existence, Cambridge University Press, p. 130

- ^ Frank Griffel (2010), The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad, Muslim philosophers' rationalist explanation, Cambridge University Press, p. 174

- ^ Griffel(2010), p.173

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 177

- ^ Mario Kozah (2015), The Birth of Indology as an Islamic Science, BRILL, p. 13, ISBN 978-90-04-30554-0

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b Mansur Al-Hallaj, Translated by Aisha Bewley (1974), The Tawasin, Diwan Press, pp. 1–3

- ^ a b c d Schimmel (1975), p.215

- ^ Mansur Al-Hallaj, Translated by Aisha Bewley (1974), The Tawasin, Diwan Press

- ^ Carl W. Ernst (2010), p. 125

- ^ a b c Hazrat Ali bin Usman Al-Hujwiri(R.A.) (2001), The Kashf Al-Mahjub (PDF), Zia-ul-Quran Publications

- ^ a b Mehdi Aminrazavi (2005), The Wine of Wisdom: The Life, Poetry and Philosophy of Omar Khayyam, Oneworld Publications, p. 55, ISBN 978 1-85168-504-2

- ^ Mehdi Aminrazavi (2005), p.56

- ^ a b The Sufistic Quatrains of Omar Khayyam, New York M.W. Dunne, 1903, p. 145

- ^ Qamar-ul Huda (2003), Striving for Divine Union: Spiritual Exercises for Suhraward Sufis, RoutledgeCurzon, ISBN 0-203-99487-6

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p.135

- ^ The first book of the Hadiqatu'l-Haqiqat or the enclosed garden of the truth of the Hakim Abu'l-Majd Majdud Sana'i of Ghazna, J. Stephenson (translator), Calcutta Printed at the Baptist Mission Press, 1910, p. 166

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d Schimmel (1985), p. 176

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 197

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 46

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p.200

- ^ a b Fariduddin Attar, Ilahi-nama - The Book of God, John Andrew Boyle (translator), Manchester University Press,

Thou knowest that none of the poets have sung such praise save only I.

- ^ Fariduddin Attar (2012), The Story of Sheikh Sam'an in The Conference of the Birds, Afkham Darbandi and Dick Davis (Translators), The Norton Anthology of World Literature, pp. 57–75

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 201

- ^ Gholamreza Aavani, Glorification of the Prophet Muhammad in the Poems of Sa'adi, Institute For Research In Philosophy, p. 1

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 170

- ^ a b Schimmel (1985), p. 196

- ^ a b c Schimmel (1985), p. 205

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p.272, note. 67

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 116

- ^ a b c d Ibn Arabi, The Seals of Wisdom (Fusus al-Hikam), Aisha Bewley

- ^ Mohammed Rustom, Rumi’s Metaphysics of the Heart (PDF), p. 73

- ^ https://bewley.virtualave.net/fusus2.html

- ^ a b c d e Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture, ABC-CLIO, LLC, p. 446, ISBN 978-1-61069-177-2

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 150

- ^ The life of Rumi, 2009-09-01, BBC

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Ibrahim Gamard (2004), Rumi and Islam, SkyLight Paths, p. 138

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel, Mystical Poetry in Islam: The Case of Maulana Jalaladdin Rumi, The Literature of Islam, The University of Notre Dame, p. 78

- ^ Gamard (2004), p.162

- ^ Gamard (2004), p.170

- ^ Gamard (2004), p.171

- ^ a b Muhammad Iqbal, The Secrets of the Self (Asrar-I Khudi), Translated by Reynold A. Nicholson, Macmillan and Co., Limited (1920), p. 36

- ^ Gamard (2004), p.169

- ^ Schimmel (1985), 203

- ^ Gholamreza Aavani, p. 15

- ^ Gholamreza Aavani, p.2

- ^ Gholamreza Aavani, p.4

- ^ Gholamreza Aavani, p.11

- ^ Christiane Gruber (2009), BETWEEN LOGOS ( KALIMA ) AND LIGHT ( NŪR ): REPRESENTATIONS OF THE PROPHET MUHAMMAD IN ISLAMIC PAINTING, Muqarnas, p. 240

- ^ Gholamreza Aavani, p.6

- ^ Al-Busiri, The Poem Of Scarf, Shaikh Faizullah Bhai (translator), Taj Company Ltd.

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 185

- ^ a b c d David Thomas (2013), Encyclopaedia of Islam, Routledge, p. 110, ISBN 1135179603

- ^ a b Thomas (2013), p.112

- ^ a b Thomas (2013), p.111

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 105

- ^ Malika Mohammada (2007), The Foundations of the Composite Culture in India, AAKAR, p. 201, ISBN 978-81-89833-18-3

- ^ Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God, p. 416

- ^ Carl W. Ernst (2010), p. 135

- ^ JĀMI, Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ^ a b c Schimmel (1985), p.28

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 170

- ^ a b Schimmel (1985), p. 128

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 133

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 207

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 153

- ^ Ibrahim Kalin (2015), The Biographical Encyclopedia of Islamic Philosophy, Bloomsbury Academic, p. 152, ISBN 978-1-4725-6944-8

- ^ Selcuk Aksin Somel (2003), The A to Z of the Ottoman Empire, The Scarecrow Press Inc., p. 88, ISBN 978-0-8108-7579-1

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 216

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 70

- ^ a b Mohibbul Hasan, History of Tipu Sultan, Aakar Books, p. 397

- ^ a b Hasan, p. 399

- ^ a b Anwar Haroon (2013), Kingdom of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, Xlibris Corporation, p. 257, ISBN 978-1-4836-1536-3

- ^ Haroon (2013), p. 289

- ^ a b c Schimmel(1985), p.115

- ^ Schimmel(1985), p.81

- ^ Islamic Beliefs, Practices, and Cultures, Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2011, p. 145, ISBN 978-0-7614-7926-0

- ^ Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad, Jane I. Smith, Kathleen M. Moore (2006), Muslim Women in America, Oxford University Press, p. 69, ISBN 978-019-517783-1

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mir Zohair Husain (2003), Global Islamic Politics, Longman, p. 96, ISBN 9780321129352

- ^ Madrasas in South Asia: Teaching Terror?, Routledge, 2008, p. 24, ISBN 978-0-203-93657-3

- ^ Mofakhkhar Hussain Khan (2001), The Holy Qurʼān in South Asia: A Bio-bibliographic Study of Translations of the Holy Qurʼān in 23 South Asian Languages, Digitized by the University of Michigan, Bibi Akhtar Prakãs̆ani, p. 285

- ^ "World: South Asia Screening the life of Jinnah". BBC News. 13 September 1998. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ a b "Jinnah, Pakistan and Islamic Identity". The New York Times. 1997. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ Ebrahim Moosa (2015), What Is a Madrasa?, The University of North Carolina Press, p. 100, ISBN 978-1-4696-2014-5

- ^ a b Imam Ahmed Raza Khan and Love for the Prophet, The Sunni Way

- ^ Muhammad Iqbal, The Secrets of the Self (Asrar-I Khudi), Translated by Reynold A. Nicholson, Macmillan and Co., Limited (1920), pp. 30–32

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p.239

- ^ a b c Schimmel (1985), p.241

- ^ a b Schimmel (1985), p.242

- ^ a b Schimmel (1985), p.243

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p.244

- ^ a b Schimmel, p.246

- ^ a b c Schimmel (1985), p.247

- ^ a b Schimmel (1985), p. 248

- ^ a b Schimmel (1985), p. 255

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p.251

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p.256

- ^ Hyunhee Park (2012). Mapping the Chinese and Islamic Worlds. Cambridge University Press. p. 120. ISBN 9781107018686. Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- ^ Zvi Ben-Dor Benite (2005). The dao of Muhammad: a cultural history of Muslims in late imperial China. Harvard University Asia Center. p. 187. ISBN 981-230-837-7. Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton (2014), Faiths Across Time: 5,000 Years of Religious History, ABC-CLIO, p. 929, ISBN 978-1-61069-026-3

- ^ Zvi Ben-Dor Benite (2005), p.182

- ^ Kaikyōken: Le monde Islamique, Volume 7, Digitized by University of Michigan in 2007, Shikai Shobō., p. 139

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Thomas Carlyle (1840), On Heroes, Hero-worship and the Heroic in History, Robson and Sons, p. 53

- ^ John William Draper (1863), History of the intellectual development of Europe, Harper & Brothers, p. 244

- ^ Bosworth R. Smith (1874), Mohammed and Mohammedanism, Smith, Elder & Co., p. 235

- ^ Bosworth (1874), p. 236

- ^ Schimmel (1985), p. 5

- ^ "Symbol of tolerance". The News International. 14 March 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ "Guru Granth Sahib: A Model For Interfaith Understanding". sikhchic.com. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ Young India (23 September 1924) Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol.29, "My Jail experiences", p. 133

- ^ Michael H. Hart. "The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History". Citadel Press. p. 3.

- ^ "Muhammad Sculpture Inside Supreme Court a Gesture of Goodwill". The Wall Street Journal. 14 January 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

Category:Islamic belief and doctrine Category:570s births Category:7th-century rulers in Asia Category:Arab Muslims Category:Islam Category:Medina Category:People from Mecca Category:Prophets of Islam Category:Quraish Category:7th-century Arab people Category:Miracles attributed to Muhammad Category:Medieval Muslims