American cuisine: Difference between revisions

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

===Cuisine in the West=== |

===Cuisine in the West=== |

||

{{Main|Cuisine of the Western United States}} |

{{Main|Cuisine of the Western United States}} |

||

Cooking in the American West gets its influence from Native American and |

Cooking in the American West gets its influence from Native American and Hispanophone cultures, and other European settlers into the part of the country. Common dishes vary depending on the area. For instance, the Northwestern region encompasses [[Oregon]], [[Washington]], and Northern California, and all rely on local seafood and a few classics of their own. In [[New Mexico]], [[Colorado]], [[Nevada]], [[Arizona]], [[Utah]], [[West Texas]], and [[Southern California]], Mexican flavors are extremely common, especially from the Mexican states of [[Chihuahua]], [[Baja California]], and [[Sonora]]]. |

||

The Pacific Northwest as a region generally includes the state of Washington near the Canadian Border and terminates near [[Sacramento, California]], |

|||

===Common dishes found on a regional level=== |

===Common dishes found on a regional level=== |

||

Revision as of 00:42, 16 November 2014

This article currently links to a large number of disambiguation pages (or back to itself). (November 2014) |

| Part of a series on |

| American cuisine |

|---|

|

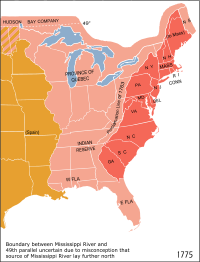

The cuisine of the United States reflects its history. The European colonization of the Americas yielded the introduction of a number of ingredients and cooking styles to the latter. The various styles continued expanding well into the 19th and 20th centuries, proportional to the influx of immigrants from many foreign nations; such influx developed a rich diversity in food preparation throughout the country.

Early Native Americans utilized a number of cooking methods in early American Cuisine that have been blended with early European cooking methods to form the basis of American Cuisine. When the colonists came to Virginia, Massachusetts, or any of the other English colonies on the eastern seaboard of North America, they farmed animals for clothing and meat in a similar fashion to what they had done in Europe. They had cuisine similar to their previous British cuisine. The American colonial diet varied depending on the settled region in which someone lived. Commonly hunted game included deer, bear, buffalo and wild turkey. A number of fats and oils made from animals served to cook much of the colonial foods. Prior to the Revolution, New Englanders consumed large quantities of rum and beer, as maritime trade provided them relatively easy access to the goods needed to produce these items: Rum was the distilled spirit of choice, as the main ingredient, molasses, was readily available from trade with the West Indies. In comparison to the northern colonies, the southern colonies were quite diverse in their agricultural diet and did not have a central region of culture.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Americans developed many new foods. During the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) food production and presentation became more industrialized. One characteristic of American cooking is the fusion of multiple ethnic or regional approaches into completely new cooking styles. A wave of celebrity chefs began with Julia Child and Graham Kerr in the 1970s, with many more following after the rise of cable channels like Food Network.

History

Pre-Colonial cuisine

Seafood

Seafood in the United States originated with the Native Americans, who often ate cod, lemon sole, flounder, herring, halibut, sturgeon, smelt, drum on the East Coast, and olachen and salmon on the West Coast. Whale was hunted by Native Americans off the Northwest coast, especially by the Makah, and used for their meat and oil.[1] Seal and walrus were also eaten, in addition to eel from New York's Finger Lakes region. Catfish was also popular amongst native peoples, including the Modocs. Crustacean included shrimp, lobster, crayfish, and dungeness crabs in the Northwest and blue crabs in the East. Other shellfish include abalone and geoduck on the West Coast, while on the East Coast the surf clam, quahog, and the soft-shell clam. Oysters were eaten on both shores, as were mussels and periwinkles.[2]

Cooking methods

Early Native Americans utilized a number of cooking methods in early American Cuisine that have been blended with early European cooking methods to form the basis of American Cuisine. Grilling meats was common. Spit roasting over a pit fire was common as well. Vegetables, especially root vegetables were often cooked directly in the ashes of the fire. As early Native Americans lacked pottery that could be used directly over a fire, they developed a technique which has caused many anthropologists to call them "Stone Boilers". They would heat rocks directly in a fire and then add the rocks to a pot filled with water until it came to a boil so that it would cook the meat or vegetables in the boiling water. In what is now the Southwestern United States, they also created adobe ovens called hornos to bake items such as cornmeal breads, and in other parts of America, made ovens of dug pits. These pits were also used to steam foods by adding heated rocks or embers and then seaweed or corn husks placed on top to steam fish and shellfish as well as vegetables; potatoes would be added while still in-skin and corn while in-husk, this would later be referred to as a clambake by the colonists.[3]

Colonial period

When the colonists came to Virginia, Massachusetts, or any of the other English colonies on the eastern seaboard of North America, their initial attempts at survival included planting crops familiar to them from back home in England. In the same way, they farmed animals for clothing and meat in a similar fashion. Through hardships and eventual establishment of trade with Britain, the West Indies and other regions, the colonists were able to establish themselves in the American colonies with a cuisine similar to their previous British cuisine. There were some exceptions to the diet, such as local vegetation and animals, but the colonists attempted to use these items in the same fashion as they had their equivalents or ignore them entirely if they could. The manner of cooking for the American colonists followed along the line of British cookery up until the Revolution. The British sentiment followed in the cookbooks brought to the New World as well.[4]

There was a general disdain for French cookery, even with the French Huguenots in South Carolina and French-Canadians. One of the cookbooks that proliferated in the colonies was The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy written by Hannah Glasse, wrote of disdain for the French style of cookery, stating “the blind folly of this age that would rather be imposed on by a French booby, than give encouragement to a good English cook!” Of the French recipes, she does add to the text she speaks out flagrantly against the dishes as she “… think it an odd jumble of trash.”[5] Reinforcing the anti-French sentiment was the French and Indian War from 1754–1764. This created a large anxiety against the French, which influenced the English to either deport many of the French, or as in the case of many Acadians from Nova Scotia, they forcibly relocated to Louisiana. The Acadian French did create a large French influence in the diet of those settled in Louisiana, but had little or no influence outside of Louisiana - except among the Acadian Francophones who settled eastern Maine at the same time they colonised New Brunswick.[6]

Common ingredients

The American colonial diet varied depending on the settled region in which someone lived. Local cuisine patterns had established by the mid-18th century. The New England colonies were extremely similar in their dietary habits to those that many of them had brought from England. A striking difference for the colonists in New England compared to other regions was seasonality.[7] While in the southern colonies, they could farm almost year round, in the northern colonies, the growing seasons were very restricted. In addition, colonists’ close proximity to the ocean gave them a bounty of fresh fish to add to their diet, especially in the northern colonies. Wheat, however, the grain used to bake bread back in England was almost impossible to grow, and imports of wheat were far from cost productive.[8] Substitutes in cases such as this included cornmeal. The Johnnycake was a poor substitute to some for wheaten bread, but acceptance by both the northern and southern colonies seems evident.[9]

As many of the New Englanders were originally from England game hunting was often a pastime from back home that paid off when they immigrated to the New World. Much of the northern colonists depended upon the ability either of themselves to hunt, or for others from which they could purchase game. This was the preferred method for protein consumption over animal husbandry, as it required much more work to defend the kept animals against Native Americans or the French.

Livestock and game

Commonly hunted game included deer, bear, buffalo and wild turkey. The larger muscles of the animals were roasted and served with currant sauce, while the other smaller portions went into soups, stews, sausages, pies, and pasties.[10] In addition to game, colonists' protein intake was supplemented by mutton. The Spanish in Florida originally introduced sheep to the New World, but this development never quite reached the North, and there they were introduced by the Dutch and English. The keeping of sheep was a result of the English non-practice of animal husbandry.[11] The animals provided wool when young and mutton upon maturity after wool production was no longer desirable.[12] The forage-based diet for sheep that prevailed in the Colonies produced a characteristically strong, gamy flavor and a tougher consistency, which required aging and slow cooking to tenderize.[13]

Fats and oils

A number of fats and oils made from animals served to cook much of the colonial foods. Many homes had a sack made of deerskin filled with bear oil for cooking, while solidified bear fat resembled shortening. Rendered pork fat made the most popular cooking medium, especially from the cooking of bacon. Pork fat was used more often in the southern colonies than the northern colonies as the Spanish introduced pigs earlier to the South. The colonists enjoyed butter in cooking as well, but it was rare prior to the American Revolution, as cattle were not yet plentiful.[14]

Alcoholic drinks

Prior to the Revolution, New Englanders consumed large quantities of rum and beer, as maritime trade provided them relatively easy access to the goods needed to produce these items: Rum was the distilled spirit of choice, as the main ingredient, molasses, was readily available from trade with the West Indies. Further into the interior, however, one would often find colonists consuming whiskey, as they did not have similar access to sugar cane. They did have ready access to corn and rye, which they used to produce their whiskey.[15] However, until the Revolution, many considered whiskey to be a coarse alcohol unfit for human consumption, as many believed that it caused the poor to become raucous and unkempt drunkards.[16] In addition to these alcohol-based products produced in America, imports were seen on merchant shelves, including wine and brandy.[17]

Southern variations

In comparison to the northern colonies, the southern colonies were quite diverse in their agricultural diet and did not have a central region of culture. The uplands and the lowlands made up the two main parts of the southern colonies. The slaves and poor of the south often ate a similar diet, which consisted of many of the indigenous New World crops. Salted or smoked pork often supplement the vegetable diet. Rural poor often ate squirrel, possum, rabbit and other woodland animals. Those on the “rice coast” often ate ample amounts of rice, while the grain for the rest of the southern poor and slaves was cornmeal used in breads and porridges. Wheat was not an option for most of those that lived in the southern colonies.[18]

The diet of the uplands often included cabbage, string beans, white potatoes, while most avoided sweet potatoes and peanuts. Well-off whites in the uplands avoided crops imported from Africa because of the perceived inferiority of crops of the African slaves. Those who could grow or afford wheat often had biscuits as part of their breakfast, along with healthy portions of pork. Salted pork was a staple of any meal, as it was used in the preparations of vegetables for flavor, in addition to being eaten directly as a protein.[19]

The lowlands, which included much of the Acadian French regions of Louisiana and the surrounding area, included a varied diet heavily influenced by Africans and Caribbeans, rather than just the French. As such, rice played a large part of the diet as it played a large part of the diets of the Africans and Caribbean. In addition, unlike the uplands, the lowlands subsistence of protein came mostly from coastal seafood and game meats. Much of the diet involved the use of peppers, as it still does today.[20] Interestingly, although the English had an inherent disdain for French foodways, as well as many of the native foodstuff of the colonies, the French had no such disdain for the indigenous foodstuffs. In fact, they had a vast appreciation for the native ingredients and dishes.[21]

North Carolina has two popular variations of barbecue, typically described by region. Eastern style barbecue is a vinegar based pork barbecue, resulting in a tangy taste. Western Style barbecue is a sweeter style of pork barbecue. Eastern style barbecue is generally shredded, while the pork in western style barbecue is served in both shredded and chopped forms. Coleslaw is usually served with both variations of barbecue. Eastern style coleslaw is mayonnaise based, while western style coleslaw is ketchup based.

Post-colonial cuisine

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Americans developed many new foods. Some, such as Rocky Mountain oysters, stayed regional; some spread throughout the nation but with little international appeal, such as peanut butter (a core ingredient of the famous peanut butter and jelly sandwich); and some spread throughout the world, such as popcorn, Coca-Cola and its competitors, fried chicken, cornbread, unleavened muffins such as the poppyseed muffin, and brownies.

Modern cuisine

During the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) food production and presentation became more industrialized. Major railroads featured upscale cuisine in their dining cars.[22] Restaurant chains emerged with standardized decor and menus, most famously the Fred Harvey restaurants along the route of the Sante Fe Railroad in the Southwest.[23]

At the universities, nutritionists and home economists taught a new scientific approach to food. During World War I the Progressives' moral advice about food conservation was emphasized in large-scale state and federal programs designed to educate housewives. Large-scale foreign aid during and after the war brought American standards to Europe.[24]

Newspapers and magazines ran recipe columns, aided by research by corporate kitchens (for example, General Mills, Campbell's, Kraft Foods). One characteristic of American cooking is the fusion of multiple ethnic or regional approaches into completely new cooking styles. Hamburgers and hot dogs from German cuisine, spaghetti and pizza from Italian cuisine became popular. Since the 1960s Asian cooking has played a particularly large role in American fusion cuisine.[25]

Similarly, some dishes that are typically considered American have their origins in other countries. American cooks and chefs have substantially altered these dishes over the years, to the degree that the dishes now enjoyed around the world are considered to be American. Hot dogs and hamburgers are both based on traditional German dishes, but in their modern popular form they can be reasonably considered American dishes.[26]

Pizza is based on the traditional Italian dish, brought by Italian immigrants to the United States, but varies highly in style based on the region of development since its arrival (a "Chicago" style has focus on a thicker, more bread-like crust, whereas a "New York Slice" is known to have a much thinner crust, for example) and these types can be advertised throughout the country and are generally recognizable/well-known (with some restaurants going so far as to import New York City tap water from a thousand or more miles away to recreate the signature style in other regions).[27]

Many companies in the American food industry develop new products requiring minimal preparation, such as frozen entrees.[28] Many of these recipes have become very popular. For example, the General Mills Betty Crocker's Cookbook, first published in 1950 and currently in its 10th edition,[29] is commonly found in American homes.[30]

A wave of celebrity chefs began with Julia Child and Graham Kerr in the 1970s, with many more following after the rise of cable channels like Food Network. Trendy food items in the 2000s and 2010s (albeit with long traditions) include doughnuts, cupcakes, macaroons, and meatballs.[31]

New American

During the 1980s, upscale restaurants introduced a mixing of cuisines that contain Americanized styles of cooking with foreign elements commonly referred as New American cuisine.[32]

Regional cuisines

Generally speaking, in the present day 21st century, the modern cuisine of the United States is very much regional in nature. The terrain spans 3,000 miles west to eat and more than a thousand North to South when only including the continental USA.

New England

New England is a Northeastern region of the United States, including the six states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont, with its cultural capital Boston, founded in 1630. The Native American cuisine became part of the cookery style that the early colonists brought with them.[citation needed] The style of New England cookery originated from its colonial roots, that is to say practical, frugal and willing to eat anything other than what they were used to from their British roots.[33] Much of the cuisine started with one-pot cookery, which resulted in such dishes as succotash, chowder, baked beans, and others.[34] Starches are fairly simple, and typically encompass potatoes and cornmeal, and a few native breads like Anadama bread and johnnycakes are a staple. This region is fairly conservative with its spices, but typical spices include nutmeg, ginger, cinnamon, cloves, and allspice, especially in desserts, and for savory foods, thyme and sage. Typical condiments include maple syrup, molasses, and the famous cranberry sauce.

New England is noted for having a heavy emphasis on seafood, a legacy inherited from coastal tribes like the Wampanoag and Narragansett, who equally used the rich fishing banks offshore for sustenance. Favorite fish include cod salmon, winter flounder, haddock, striped bass, bluefish, and tautog, which are prepared numerous ways, such as frying cod for fish fingers, grilling bluefish over hot coals for summertime, smoking salmon or serving a whole one chilled for feasts with a dill sauce, or serving haddock baked in casserole dish with milk and crumbled breadcrumbs as a top. Farther inland brook trout, largemouth bass and herring are sought after, especially in the rivers and finger lakes in upper New England. Meat is present though not as prominent, and typically is either stewed in dishes like Yankee pot roast and New England boiled dinner or roasted, as in a Boston butt. A variety of linguiça is favored as a breakfast food, brought with Portuguese fisherman and Brazilian immigrants.

Crustaceans and mollusks are also an essential ingredient in the regional cookery. Maine is noted for harvesting peekytoe crab and Jonah crab and making crab bisques and crabcakes out of them, and often they appear on the menu as far south as to be out of region in New York City, where they are sold to four star restaurants. Squid are heavily fished for and eaten as calamari, and often are an ingredient in Italian American cooking in this region. Whelks are often eaten in salad, and most famous of all is the lobster, which is indigenous to the coastal waters of the region and are a feature of many dishes, baked, boiled, roasted, and steamed, or simply eaten as a sandwich, chilled with mayonnnaise and chopped celery.

Shellfish of all sorts are part of the diet, and shellfish of the coastal regions include little neck clams, sea scallops, blue mussels, oysters, soft shell clams and razor shell clams. Much of this shellfish contributes to New England tradition, the clambake. The clambake as known today is a colonial interpretation of an American Indian tradition.[35] Oysters and razor clams are dipped in batter and fried, served with french fries, or in the case of oysters, eaten on the half shell. Large quahogs are stuffed with breadcrumbs and seasoning and baked in their shells, and smaller ones often find their way into clam chowder.

The fruits of the region include the Vitis labrusca grapes used in grape juice made by companies such as Welch's, along with jelly, Kosher wine by companies like Mogen David and Manischewitz along with other wineries that make higher quality wines. Apples from New England include the original varieties Baldwin, Lady, Mother, Pomme Grise, Porter, Roxbury Russet, Wright, Sops of Wine, Hightop Sweet, Peck's Pleasant, Titus Pippin, Westfield-Seek-No-Further, and Duchess of Oldenburg. Cranberries are another fruit indigenous to the region.[36] Blueberries are a very common summertime treat owing to them being an important crop, and find their way into muffins, pies and pancakes. Typical favorite desserts are quite diverse, and encompass hasty pudding, Boston cream pie, pumpkin pie, Joe Frogger cookies, hand crafted ice cream, Hermit cookies, and most famous of all, the chocolate chip cookie, invented in Massachusetts in the 1930s.

Pacific and Hawaiian cuisine

Hawaii is often considered to be one of the most culturally diverse U.S. states, as well as being the only state with an Asian majority population and being one of the few places where United States territory extends into the tropics. As a result, Hawaiian cuisine borrows elements of a variety of cuisines, particularly those of Asian and Pacific-rim cultures, as well as traditional native Hawaiian and a few additions from the American mainland. American influence of the last 150 years has brought cattle, goats, and sheep to the islands, introducing cheese, butter, and yogurt products, as well as crops like red cabbage. Just to name a few, major Asian and Polynesian influences on modern Hawaiian cuisine are from Japan, Korea, Vietnam, China (especially near the Pearl River delta), Samoa, and the Philippines. From Japan, the concept of serving raw fish as a meal with rice was introduced, as was soft tofu, setting the stage for the very popular dish called poke. From Korea, immigrants to Hawaii brought a love of spicy garlic marinades for meat and kimchi. From China, their version of char siu baau became modern manapua, a type of steamed pork bun with a spicy filling. Filipinos brought vinegar,bagoong and lumpia, and during the 20th century immigrants from American Samoa brought the open pit fire umu and the Vietnamese introduced lemongrass and fish sauce. Each East Asian culture brought several different kinds of noodles, including udon, ramen, mei fun, and pho, and today these are common lunchtime meals.

Much of this cuisine mixes and melts into traditions like the infamous lu'au, whose traditional elaborate fare was once the prerogative of kings and queens but today is the subject of parties for both tourists and also private parties for the ‘ohana (meaning family and close friends.) Traditionally, women and men ate separately under the Hawaiian kapu system, a system of religious beliefs that honored the Hawaiian gods similar to the Maori tapu system, though in this case had some very specific prohibitions towards females eating things like coconut, pork, turtle meat, and bananas as these were considered parts of the male gods, and punishment for violation could be very severe, as a woman might endanger a man's mana, or soul, by eating with him or dishonoring the male gods. As the system broke down after 1810, introductions of foods from laborers on plantations began to be included at feasts and much cross pollination occurred, where Asian foodstuffs mixed with Polynesian foodstuffs like breadfruit, kukui nuts, and purple sweet potatoes.

Some notable Hawaiian fare includes seared ahi tuna, opakapaka (snapper) with passionfruit, Hawaiian island-raised lamb, beef and meat products, Hawaiian plate lunch, and Molokai shrimp. Seafood traditionally is caught fresh in Hawaiian waters, and particular delicacies are 'ula poni , papaikualoa, ‘opihi, and ‘opihi malihini , better known as Hawaiian spiny lobster, Kona crab, Hawaiian limpet, and abalone. Some cuisine also incorporates a broad variety of produce and locally grown agricultural products, including tomatoes, sweet Maui onions, taro, and macadamia nuts. Tropical fruits equally play an important role in the cuisine as a flavoring in cocktails and in desserts, including local cultivars of bananas, sweetsop, mangoes, lychee, coconuts, papayas, and lilikoi (passionfruit). Pineapples have been an island staple since the 19th century and figure into many marinades and drinks.

Midwest

Midwestern cuisine covers everything from barbecue to the Chicago-style hot dog.

The American South

When referring to the American South as a region, typically it should indicate Southern Maryland and the states that were once part of the Old Confederacy, with the dividing line between the East and West jackknifing about 100 miles west of Dallas, Texas, and mostly south of the old Mason-Dixon line. These states are much more closely tied to each other and have been part of US territory for much longer than states much farther west than East Texas, and in the case of food, the influences and cooking styles are strictly separated as the terrain begins to change to prairie and desert from bayou and hardwood forest.

This section of the country has some of the oldest known foodways in the land, with some recipes approaching 400 years old. Native American influences are still quite visible in the use of cornmeal as an essential staple [37] and found in the Southern predilection for hunting wild game, in particular wild turkey, deer, and various kinds of waterfowl.[38][39] Native Americans also consumed turtles and catfish, specifically the snapping turtle and blue catfish, both very important parts of the diet in the South today, often fried in the latter case and made into a stew or soup in the former.[40][41] Native American tribes of the region such as the Cherokee or Choctaw often cultivated or gathered local plants like pawpaw, maypop,[42]spicebush,[43]sassafrass,[44] and several sorts of squash and maize, and the aforementioned fruits still are cultivated as food in a Southerner's back garden.[45] Maize is to this day found in dishes for breakfast, lunch and dinner in the form of grits, hoecakes, and spoonbread, and nuts like the hickory, black walnut and pecan are very commonly included in desserts and pastries as varied as mince pies, pecan pie, pecan rolls (a type of sticky bun), and quick breads, which were themselves invented in the South during the American Civil War.

European influence began soon after the settlement of Jamestown in 1607 and the earliest recipes emerging by the end of the 17th century. Specific influences from Europe were quite varied, and remain traditional and essential to the modern cookery overall. To the upper portion of the South, French Huguenots brought the concept of making rouxs to make sauces and soups, and later French settlers hunted for frogs in the swamps to make frog's legs. German speakers often settled in Appalachia on small farms or in the backcountry away from the coast, and invented an American breakfast delicacy that is now nationally beloved, apple butter, based on their recipe for apfelkraut, and later introduced red cabbage and rye. From the UK, an enormous amount of influence was bestowed upon the South, specifically foodways found in 17th and 18th century Ulster, the borderlands between England and Scotland, the Scottish Highlands, portions of Wales, the West Midlands and Black Country. Settlers bound for America fled the tumult of the Civil War and troubles in the plantation of Ireland and the Highland Clearances, and very often ships manifests show their belongings nearly always included their wives' cookpots or bakestones and seed stock for plants like peaches, plums, and apples to grow orchards. Each group brought foods and ideas from their region which gave birth in time to American whiskey and Kentucky bourbon, derived from the recipes of Celtic peoples, tipsy cakes, derived from 18th century recipes for English trifle, and all of the above made the staple meat of the South pork, to this day consumed as pickled pig's feet, country ham, especially when discussing Virginia and parts of the Appalachians, and baby back ribs.

African influences came with slaves from Ghana, Benin,Mali, Côte d'Ivoire, Angola, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, and other portions of West Africa, and the mark they and their descendants have made on Southern food is very strong today. Crops like okra, sorghum, sesame seeds, eggplant, chili peppers, and many different kinds of melons were brought with them from West Africa along with the incredibly important introduction of rice to the Carolinas and later to Texas and Louisiana, whence it became a staple grain of the region and still remains a staple today, found in dishes like Hoppin John, rice and beans, purloo, and Charleston red rice. Other crops, like sugar cane, kidney beans, and certain spices would have been familiar to slaves through contact with British colonies in the Caribbean and also brought with them. Like the poorer indentured servants that came to the South, slaves often got the leftovers of what was slaughtered for the consumption of the master of the plantation and so many recipes had to be adapted for offal, like hog maw and cracklins,[46] though other methods encouraged low and slow methods of cooking to tenderize the tougher cuts of meat, like braising, smoking, and pit roasting. It is from this class of people that Southern cuisine gets barbecue and fried chicken. Other recipes certainly brought by Africans involve peanuts, as evidenced by the local nickname for the legume in Southern dialects of American English: goober, taken from the Kongo word for peanut, nguba. The 300 year old recipe for peanut soup is a classic of Southern cuisine that has never stopped being eaten, handed down to the descendants of Virginia slaves and adapted to be creamier and less spicy than the original African dish.[47]

Certain portions of the South often have their own very distinct subtypes of cuisine owing to local history and landscape: though Cajun cuisine is more famous, Floridian cuisine, for example, has a very distinct way of cooking that includes ingredients her other Southern sisters do not use, especially points south of Tampa. The Spanish Crown had control of the state until the early 19th century and used the southern tip as an outpost beginning in the 1500s, but Florida kept and still maintains ties with the Caribbean Sea, including the Bahamas Haiti, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Jamaica, and also holds the legacy of Anglophone settlers foodways and the foodways of the Seminole tribe of Native Americans. Thus, tomatoes, bell peppers, plantains, Caribbean lobsters, heart of palm, citrus of all kinds, scotch bonnet peppers, mangoes, blue crab, and marlins tend to be local favorites, and dairy, though available, less emphasized due to the year round warmth. Traditional key lime pie, a dessert from the islands off the coast of Miami, is made with condensed milk to form the custard with the eye wateringly tart limes native to the Florida Keys in part because milk would spoil in an age before refrigeration.

Cuisine in the West

Cooking in the American West gets its influence from Native American and Hispanophone cultures, and other European settlers into the part of the country. Common dishes vary depending on the area. For instance, the Northwestern region encompasses Oregon, Washington, and Northern California, and all rely on local seafood and a few classics of their own. In New Mexico, Colorado, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, West Texas, and Southern California, Mexican flavors are extremely common, especially from the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Baja California, and Sonora].

The Pacific Northwest as a region generally includes the state of Washington near the Canadian Border and terminates near Sacramento, California,

Common dishes found on a regional level

-

Chicago-style deep-dish pizza from the original Pizzeria Uno location

Ethnic and immigrant influence

This section possibly contains original research. (February 2008) |

The demand for ethnic foods in the United States reflects the nation's changing diversity as well as its development over time. According to the National Restaurant Association,

Restaurant industry sales are expected to reach a record high of $476 billion in 2005, an increase of 4.9 percent over 2004... Driven by consumer demand, the ethnic food market reached record sales in 2002, and has emerged as the fastest growing category in the food and beverage product sector, according to USBX Advisory Services. Minorities in the U.S. spend a combined $142 billion on food and by 2010, America's ethnic population is expected to grow by 40 percent.[48]

A movement began during the 1980s among popular leading chefs to reclaim America's ethnic foods within its regional traditions, where these trends originated. One of the earliest was Paul Prudhomme, who in 1984 began the introduction of his influential cookbook, Paul Prodhomme's Louisiana Kitchen, by describing the over 200 year history of Creole and Cajun cooking; he aims to "preserve and expand the Louisiana tradition."[49] Prodhomme's success quickly inspired other chefs. Norman Van Aken embraced a Floridian type cuisine fused with many ethnic and globalized elements in his Feast of Sunlight cookbook in 1988. The movement finally gained fame around the world when California became swept up in the movement, then seemingly started to lead the trend itself, in, for example, the popular restaurant Chez Panisse in Berkeley. Examples of the Chez Panisse phenomenon, chefs who embraced a new globalized cuisine, were celebrity chefs like Jeremiah Tower and Wolfgang Puck, both former colleagues at the restaurant. Puck went on to describe his belief in contemporary, new style American cuisine in the introduction to The Wolfgang Puck Cookbook:

Another major breakthrough, whose originators were once thought to be crazy, is the mixing of ethnic cuisines. It is not at all uncommon to find raw fish listed next to tortillas on the same menu. Ethnic crossovers also occur when distinct elements meet in a single recipe. This country is, after all, a huge melting pot. Why should its cooking not illustrate the American transformation of diversity into unity?[50]

Puck's former colleague, Jeremiah Tower became synonymous with California Cuisine and the overall American culinary revolution. Meanwhile, the restaurant that inspired both Puck and Tower became a distinguished establishment, popularizing its so called "mantra" in its book by Paul Bertolli and owner Alice Waters, Chez Panisse Cooking, in 1988. Published well after the restaurants' founding in 1971, this new cookbook from the restaurant seemed to perfect the idea and philosophy that had developed over the years. The book embraced America's natural bounty, specifically that of California, while containing recipes that reflected Bertoli and Waters' appreciation of both northern Italian and French style foods.

Early ethnic influences

While the earliest cuisine of the United States was influenced by indigenous Native Americans, the cuisine of the thirteen colonies or the culture of the antebellum American South; the overall culture of the nation, its gastronomy and the growing culinary arts became ever more influenced by its changing ethnic mix and immigrant patterns from the 18th and 19th centuries unto the present. Some of the ethnic groups that continued to influence the cuisine were here in prior years; while others arrived more numerously during “The Great Transatlantic Migration (of 1870—1914) or other mass migrations.

Some of the ethnic influences could be found in the nation from after the American Civil War and into the History of United States continental expansion during most of the 19th century. Ethnic influences already in the nation at that time would include the following groups and their respective cuisines:

- Select nationalities of Europe and the respective developments from early modern European cuisine of the colonial age:

- British-Americans and on-going developments in New England cuisine, the national traditions founded in cuisine of the thirteen colonies and some aspects of other regional cuisine.

- Spanish Americans and early modern Spanish cuisine, as well as Basque-Americans and Basque cuisine.

- Early German-American or Pennsylvania Dutch and Pennsylvania Dutch cuisine

- French Americans and their "New World" regional identities such as:

- Louisiana Creole and Louisiana Creole cuisine. Louisiana Creole (also called French Créole) refers to native born people of the New Orleans area who are descended from the Colonial French and/or Spanish settlers of Colonial French Louisiana, before it became part of the United States in 1803 with the Louisiana Purchase.

- The various ethnicities originating from early social factors of Race in the United States and the gastronomy and cuisines of the “New World,” Latin American cuisine and North American cuisine:

- Indigenous Native Americans in the United States and American Indian cuisine

- African-Americans and “Soul food.”

- Cuisine of Puerto Rico

- Mexican-Americans and Mexican-American cuisine; as well as related regional cuisines:

- Tex-Mex (regional Texas and Mexican fusion)

- Cal-Mex (regional California and Mexican fusion)

- Some aspects of “Southwestern cuisine.”

- Cuisine of New Mexico

Later ethnic and immigrant influence

Mass migrations of immigrants to the United States came in several waves. Historians identify several waves of migration to the United States: one from 1815–1860, in which some five million English, Irish, Germanic, Scandinavian, and others from northwestern Europe came to the United States; one from 1865–1890, in which some 10 million immigrants, also mainly from northwestern Europe, settled, and a third from 1890–1914, in which 15 million immigrants, mainly from central, eastern, and southern Europe (many Austrian, Hungarian, Turkish, Lithuanian, Russian, Jewish, Greek, Italian, and Romanian) settled in the United States.[51]

Together with earlier arrivals to the United States (including the indigenous Native Americans, Hispanic and Latino Americans, particularly in the West, Southwest, and Texas; African Americans who came to the United States in the Atlantic slave trade; and early colonial migrants from Britain, France, Germany, Spain, and elsewhere), these new waves of immigrants had a profound impact on national or regional cuisine. Some of these more prominent groups include the following:

- Arab Americans, particularly Lebanese Americans (the largest ethnic Arab group in the United States) – Arab cuisine, Lebanese cuisine

- Chinese Americans – American Chinese cuisine, Chinese cuisine

- Cuban Americans – Cuban cuisine

- German Americans – German cuisine (the Pennsylvania Dutch, although descended from Germans, arrived earlier than the bulk of German migrants and have distinct culinary traditions)

- Greek Americans – Greek American cuisine, Greek cuisine, Mediterranean cuisine

- Indian Americans – Indian cuisine

- Irish Americans – Irish cuisine

- Italian Americans – Italian-American cuisine, Italian cuisine

- Japanese Americans – Japanese cuisine, with influences on the Hawaiian cuisine

- Jewish Americans – Jewish cuisine, with particular influence on New York City cuisine

- Lithuanian Americans – Lithuanian cuisine, Midwest

- Nicaraguan American-Nicaraguan cuisine

- Pakistani Americans – Pakistani cuisine

- Polish Americans – Polish cuisine, with particular impact on Midwest

- Polynesian Americans – Hawaiian cuisine

- Portuguese Americans – Portuguese cuisine

- Romanian Americans – Romanian cuisine

- Russian Americans – Russian cuisine, with particular impact on Midwest

- Salvadoran Americans – Salvadoran cuisine

- Scottish Americans – Scottish cuisine

- Turkish Americans - Turkish cuisine, Balkan cuisine

- Vietnamese Americans – Vietnamese cuisine

- West Indian Americans – Caribbean cuisine, Jamaican cuisine

"Italian, Mexican and Chinese (Cantonese) cuisines have indeed joined the mainstream. These three cuisines have become so ingrained in the American culture that they are no longer foreign to the American palate. According to the study, more than nine out of 10 consumers are familiar with and have tried these foods, and about half report eating them frequently. The research also indicates that Italian, Mexican and Chinese (Cantonese) have become so adapted to such an extent that "authenticity" is no longer a concern to customers."[52]

Contributions from these ethnic foods have become as common as traditional "American" fares such as hot dogs, hamburgers, beef steak, which are derived from German cuisine, (chicken-fried steak, for example, is a variation on German schnitzel), cherry pie, Coca-Cola, milkshakes, fried chicken (Fried chicken is of Scottish and African influence) and so on. Nowadays, Americans also have a ubiquitous consumption of foods like pizza and pasta, tacos and burritos to "General Tso's chicken" and fortune cookies. Fascination with these and other ethnic foods may also vary with region.

Notable American chefs

American chefs have been influential both in the food industry and in popular culture. An important 19th Century American chef was Charles Ranhofer of Delmonico's Restaurant in New York City. American cooking has been exported around the world, both through the global expansion of restaurant chains such as T.G.I. Friday's and McDonald's and the efforts of individual restaurateurs such as Bob Payton, credited with bringing American-style pizza to the UK.[53]

The first generation of television chefs such as Robert Carrier and Julia Child tended to concentrate on cooking based primarily on European, especially French and Italian, cuisines. Only during the 1970s and 1980s did television chefs such as James Beard and Jeff Smith shift the focus towards home-grown cooking styles, particularly those of the different ethnic groups within the nation. Notable American restaurant chefs include Thomas Keller, Charlie Trotter, Grant Achatz, Alfred Portale, Paul Prudhomme, Paul Bertolli, Frank Stitt, Alice Waters, Patrick O’Connell and celebrity chefs like Mario Batali, David Chang, Alton Brown, Emeril Lagasse, Cat Cora, Michael Symon, Bobby Flay, Ina Garten, Todd English, Sandra Lee, Anthony Bourdain, and Paula Deen.

Regional chefs are emerging as localized celebrity chefs with growing broader appeal, such as Peter Merriman (Hawaii Regional Cuisine), Jerry Traunfeld, Alan Wong (Pacific Rim cuisine), Norman Van Aken (New World Cuisine – fusion Latin, Caribbean, Asian, African and American), and Mark Miller (American Southwest cuisine).

See also

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of the United States |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

United States portal |

- Cuisine of Antebellum America

- Cuisine of New York City

- List of American desserts

- List of American breads

- List of American foods

- List of American regional and fusion cuisines

- Native American cuisine

- Tlingit cuisine

References

Notes

- ^ A Fact Sheet Issued by the Makah Whaling Commission

- ^ Root & De Rochemont 1981:21, 22

- ^ Root & De Rochemont 1981:31, 32

- ^ Smith 2004:512.

- ^ Glasse 1750.

- ^ Smith 2004:512, Vol. 1.

- ^ Oliver 2005:16–19.

- ^ Pillsbury 1998:25.

- ^ Oliver 2005:22.

- ^ Smith 2004:546–547, Vol. 1.

- ^ Smith 2004:26, Vol. 2.

- ^ Root & De Rochemont 1981:176–182

- ^ Apple Jr., R.W. (2006-03-29). "Much Ado About Mutton, but Not in These Parts". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

Until it fell from favor after World War II, it was a favorite of most Britons, who prized mutton (defined there as the meat from sheep at least 2 years old) above lamb (from younger animals) for its texture and flavor. It has a bolder taste, a deeper color and a chewier consistency.

- ^ Smith 2004:458–459, Vol. 2.

- ^ Pillsbury 1998:17.

- ^ Crowgey 1971:18–19.

- ^ Pillsbury 1998:18.

- ^ Pillsbury 1998:34–35.

- ^ Pillsbury 1998:47–48.

- ^ Pillsbury 1998:48–49.

- ^ Smith 2004:149, Vol. 2.

- ^ James D. Porterfield, Dining by Rail: The History and Recipes of America's Golden Age of Railroad Cuisine (1993)

- ^ Stephen Fried, Appetite for America: How Visionary Businessman Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire That Civilized the Wild West (Bantam; 2010)

- ^ Helen Zoe Veit, Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century (2013)

- ^ Asian Cuisine & Foods

- ^ Hamburgers & Hot Dogs – All-American Food

- ^ Eddie and Sams Pizza of Tampa, FL

- ^ ConAgra’s Chief Is Moving to Revitalizny's products

- ^ Crocker 2005.

- ^ Face value: Fictional Betty Crocker gives big business a human touch

- ^ Bonny Wolf (2011-12-04). "Meatballs: A Happy Food In Hard Times". NPR. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- ^ "Foodies". Studio 10. 2011. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

- ^ Smith 2004:181–182.

- ^ Danforth, Feierabend & Chassman 1998:13

- ^ Danforth, Feierabend & Chassman 1998:12–19

- ^ Danforth, Feierabend & Chassman 1998:24–26

- ^ http://www.wrmills.com/indian-head-yellow-corn-meal

- ^ http://www.wdtv.com/wdtv.cfm?func=view§ion=5-News&item=Fall-Wild-Turkey-Season-Opens-Oct-11-

- ^ http://www.deeranddeerhunting.com/blogs/southern-hunting-for-whitetail-deer

- ^ http://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2014/aug/03/snapping-turtle-makes-delicious-dinner/?f=threerivers

- ^ http://www.southernliving.com/food/kitchen-assistant/fried-catfish-recipes

- ^ http://www.tn.gov/state-symbols.shtml

- ^ http://www.monticello.org/library/exhibits/lucymarks/gallery/spicebush.html

- ^ http://www.choctawschool.com/home-side-menu/iti-fabvssa/history-and-development-of-choctaw-food.aspx

- ^ http://www.southernmatters.com/native_edibles/

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=xhpBsIa5yqEC&pg=PA97&lpg=PA97&dq=black+slaves+offal&source=bl&ots=AXdv1wKOPv&sig=1zdCmnO01j_sXPMBSKT8ydh2IWA&hl=en&sa=X&ei=9aJcVMzeC5KNyATxzYC4Dw&ved=0CCYQ6AEwBA

- ^ http://nationalpeanutboard.org/recipes/a-thanksgiving-recipe-virginia-peanut-soup/

- ^ Oralia 2005 (par. 6).

- ^ Prodhomme 1984 n.p.

- ^ Puck 1986 n.p.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Hensley, Sue, National Restaurant Association. Article/ News Release, "International Cuisine Reaches America's Main Street," 10 August 2000.

- ^ Bob Payton, 50, Restaurateur, Dies. New York Times July 16, 1994, Obituary, p 28.[2]

Works cited

- Bertolli, Paul; Alice Waters (1988). Chez Panisse Cooking. New York: Random House..

- Crocker, Betty (2005). Betty Crocker Cookbook: Everything You Need to Know to Cook Today (10, illustrated, revised ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-7645-6877-0..

- Crowgey, Henry G. (1971). Kentucky Bourbon: The Early Years of Whiskeymaking'. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky..

- Danforth, Randi; Feierabend, Peter.; Chassman, Gary. (1998). Culinaria The United States: A Culinary Discovery. New York: Konemann..

- Fried, Stephen. Appetite for America: How Visionary Businessman Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire That Civilized the Wild West (Bantam; 2010)

- Glasse, Hannah (1750). Art of Cookery Made Easy. London..

- Oliver, Sandra L. (2005). Food in Colonial and Federal America. London: Greenwood Press..

- Oralia, Michael (2005-04-05). "Demand for Ethnic & International Foods Reflects a Changing America". National Restaurant Association. Retrieved 2009-03-08. [dead link].

- Pillsbury, Richard (1998). No Foreign Food: The American Diet in Time and Place. Westview..

- Porterfield, James D. (1993). Dining by Rail: The History and Recipes of America's Golden Age of Railroad Cuisine. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-18711-4.

- Prodhomme, Paul (1984). Paul Prodhomme's Louisiana Kitchen. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0-688-02847-0..

- Puck, Wolfgang (1986). The Wolfgang Puck Cookbook. New York: Random House.

- Root, Waverly; De Rochemont, Richard (1981). Eating in America: a History. New Jersey: The Ecco Press..

- Smith, Andrew F. (2004). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press..

- Tower, Jeremiah (2004). California Dish, What I Saw (and cooked) at the American Culinary Revolution. New York: Free Press/Simon & Schuster..

- Tower, Jeremiah (1986). New American Classics. Harper & Row..

- Van Aken, Norman (1988). Feast of Sunlight. New York: Ballantine/Random House. ISBN 0-345-34582-7.

- Veit, Helen Zoe. Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century (2013)

External links

- Key Ingredients: America by Food -Educational companion to Smithsonian Institution's exhibit on American food ways.