Brazil: Difference between revisions

m Revert to the revision prior to revision 323779696 dated 2009-11-03 22:21:01 by 189.58.135.135 using popups |

|||

| Line 122: | Line 122: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{{Main|History of Brazil}} |

{{Main|History of Brazil}} |

||

===Native Brazilians and early Portuguese settlers=== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

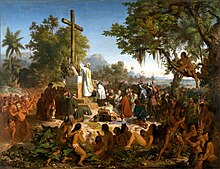

[[File:Meirelles-primeiramissa2.jpg|thumb|220px|right|The first Christian mass celebrated in what would later be called Brazil marking the beginning of the [[Colonial Brazil|Portuguese colonization]].]] |

|||

When arriving in April 1500 in the coast of what would later be known as Brazil, the Portuguese fleet commanded by [[Pedro Álvares Cabral]] found the primitive inhabitants who inhabited it.<ref name="Boxer, p.98">Boxer, p.98</ref> They were divided in several distinct tribes, that fought among themselves<ref name="Boxer, p.100">Boxer, p.100</ref> and that shared the same [[Tupi-Guarani]] linguistic family.<ref name="Boxer, p.98"/> The “men were hunters, fishers and food collectors and the women were encharged of the reduced agricultural activity that was practiced.”<ref name="Boxer, p.98">Boxer, p.98</ref> Some of the tribes were nomads and other sedentary; they knew the fire but not metal casting and a few were cannibals.<ref name="Boxer, p.98"/> |

|||

The settling was effectively initiated in 1534, when King [[Don (honorific)|Dom]] [[John III of Portugal|João III]] divided the Brazilian territory in twelve hereditary captainships that would be governed by members of the lesser nobility or proceeding from educated families.<ref>Boxer, pp.100-101</ref> The experience revealed itself to be an utter disaster, and in 1549 the king assigned a governor-general to administrate the entire colony.<ref>Boxer, p.101</ref> With the foundation of villages appeared the [[municipal council]]s, and consequently, the beginning of the [[Representative democracy|democratic representative system]] in Brazil.<ref>Boxer, p.291, the municipal council of Salvador was created at the same time as the city itself in 1549, for example.</ref> Up to 1549, most of the (few) colonists were exiled men, but from that date and on, the voluntary emigrants (including women and children) became predominant.<ref>Boxer, p.104</ref> |

|||

===Origins=== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:Participantes do Fórum Social Mundial 2009 1600FRP8520.jpg|thumb|200px|Two Brazilians of indigenous descent wearing traditional costumes.]] |

|||

Around 1530, the [[Tupiniquim]] (the same tribe that Cabral met) and their bitter enemies the [[Tupinambá]], the largest and most important tribes in Brazil, allied themselves with the Portuguese and the French, respectively.<ref name="Boxer, p.100"/> Between the Portuguese and the Tupiniquim “occurred a certain intermittently pacific inter-racial assimilation.”<ref>Boxer, p.108</ref> While the Tupinambás, however, were mostly exterminated in long wars and mainly by European diseases to which they had no immunities.<ref name="Boxer, p.102">Boxer, p.102</ref> The ones that survived were enslaved by other tribes or by the Portuguese or fled toward the countryside.<ref name="Boxer, p.102"/> By the middle of the 16th century, sugar had become the most important item of the Brazilian exportations.<ref name="Boxer, p.100"/> Thus, the Portuguese turned to other forms of man power to handle with the increasing international [[demand (economics)|demand]].<ref name="Boxer, p.102"/> Enslaved Africans were imported and became the “basic pillar of the economy” in the most populous areas of the colony.<ref>Boxer, p.110</ref> |

|||

Most [[Indigenous peoples|native peoples]] who live and lived within Brazil's current borders are thought to descend from the first wave of immigrants from North Asia ([[Siberia]]) that crossed the [[Bering Land Bridge]] at the end of the last [[Ice Age]] around 9000 BC. In 1500 AD, the territory of modern Brazil had an estimated total population of nearly 3 million [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Amerindians]] divided in 2,000 nations and tribes. |

|||

===Territorial expansion=== |

|||

A not-updated linguistic survey found 188 living [[Languages of Brazil|indigenous languages]] with 155,000 total speakers. In 2007, [[Fundação Nacional do Índio]] ({{lang-en|National Indian Foundation}}) reported the presence of 67 different tribes yet living without contact with civilization, up from 40 in 2005. With this figure, now Brazil has the largest number of [[uncontacted peoples]] in the world, even more than the island of [[New Guinea]].<ref>[http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/07/07/AR2007070701312.html In Amazonia, Defending the Hidden Tribes]. The Washington Post. July 8, 2007.</ref> |

|||

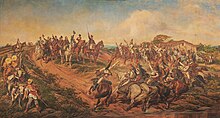

Through wars against the French, the Portuguese slowly expanded their territory to the Southeast, taking [[Rio de Janeiro]] in 1567, and to the northwest, [[São Luís]] in 1615.<ref>Bueno, pp.80-81</ref> They suffered a setback with the Dutch invasions that began in 1630 and that managed to conquer large portions of the Brazilian northeastern coastline. The Dutch domain did not last long and they were expelled definitively in 1649.<ref>Bueno, p.96</ref> The Portuguese sent military expeditions to the [[Amazon Rainforest|Amazon rainforest]] that defeated and conquered British and Dutch strongholds. The Portuguese settlement in the region initiated in 1669, with the foundation of villages and forts.<ref>Calmon, p.294</ref> In 1680 they reached the far south and founded [[Colonia del Sacramento|Sacramento]] at the side of the [[Rio de la Plata]], in the Eastern Strip region (current [[Uruguay]]).<ref>Bueno, p.86</ref> |

|||

When the [[Portugal|Portuguese]] explorers arrived in 1500, the Amerindians were mostly semi-[[nomadic]] tribes, with the largest population living on the coast and along the banks of major rivers. Unlike [[Christopher Columbus]] who thought he had reached [[India]], the Portuguese sailor [[Vasco da Gama]] had already reached India sailing around [[Africa]] two years before [[Pedro Álvares Cabral]] reached Brazil. Nevertheless, the word ''índios'' ("Indians") was by then established to designate the peoples of the [[New World]] and stuck being used today in the Portuguese language, while the people of India are called ''indianos''. Initially, the Europeans saw the natives as [[noble savage]]s, and [[miscegenation]] of the population began right away. Tribal warfare and [[cannibalism]] convinced the Portuguese that they should "[[civilising mission|civilize]]" the Amerindians.<ref>Megan Mylan, [http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/brazil501/indians_trade.html Indians of the Amazon], Jewel of the Amazon, FRONTLINE/World, [[Public Broadcasting Service]] (PBS), (24 January 2006)</ref> |

|||

[[File:Meirelles-guararapes.jpg|thumb|220px|left|The [[Portuguese people|Portuguese]] and their [[Amerindian]] and [[African people|African]] allies expanded the Brazilian territory through endless wars of conquest.]] |

|||

At the end of the 17th century sugar exports entered in decline due to competition with the British and Dutch colonies in the Caribbean and also due to high taxes.<ref>Boxer, p.164</ref> The discovery of gold by [[Bandeirantes|explorers]] in the region that would later be called [[Minas Gerais]] (General Mines) between 1693 and 1695 saved the colony from its imminent collapse.<ref>Boxer, p.168</ref> From all over Brazil, as well from Portugal, thousands of immigrants, from all ethnicities, departed toward the mines.<ref>Boxer, p.169</ref> A 20% tax over the gold extraction created dissatisfaction that resulted in an open rebellion in 1720. The Portuguese government suffocated it with relative easiness, assuring its rule over the region for the next seventy years,<ref>Boxer, p.170</ref> until the discovery of two small secessionist conspiracies in Minas Gerais and [[Bahia]].<ref>Boxer, pp.212-213</ref> In the following decades other gold mines were found in current [[Mato Grosso]] and [[Goiás]], in the Brazilian [[Central-West Region, Brazil|Central-West]].<ref>Boxer, p.170 “...continuaram tomando o rumo do ocidente nas décadas seguintes e descobriram os campos auríferos de Cuiabá, Goiás e Mato Grosso.”</ref> The Spanish tried to prevent the Portuguese expansion on the territory belonged to them according to the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494 and succeeded on conquering the Eastern Strip in 1777. All in vain as the [[First Treaty of San Ildefonso|Treaty of San Ildefonso]] signed in the same year confirmed Portuguese domain over all lands proceeding from its territorial expansion, thus creating most of current Brazilian borders.<ref>Boxer, p.207</ref> |

|||

In 1808, the Portuguese Royal family, fleeing from the troops of the French Emperor [[Napoleon I]] that were invading Portugal and most of Central Europe, [[Transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil|established themselves]] in the city of Rio de Janeiro, which thus became the seat of the entire [[Portuguese Empire]]<ref name="Boxer, p.213">Boxer, p.213</ref> In 1815 King [[John VI of Portugal|Dom João VI]], then regent on behalf of his incapacitated mother, elevated Brazil from colony to sovereign [[United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves|Kingdom united with Portugal]].<ref name="Boxer, p.213"/> The Portuguese invaded [[French Guiana]] in 1809 (that was returned to France in 1817)<ref>Bueno, p.145</ref> and the Eastern Strip in 1816 that was subsequently renamed [[Cisplatina|Cisplatine]].<ref>Calmon (2002), p.191</ref> |

|||

===Colonization=== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Image:Brazil-16-map.jpg|left|thumb|Map of Brazil issued by the [[Portugal|Portuguese]] [[explorer]]s in 1519.]] |

|||

===Independence and Empire=== |

|||

Portugal had little interest in Brazil, mainly because of the high profits to be gained from its commerce with [[India]], [[Indochina]], [[China]] and [[Japan]]. Brazil's only economic exploitation was the pursuit of [[brazilwood]] for its treasured red dye. Starting in 1530, the [[List of Portuguese monarchs|Portuguese Crown]] devised the [[Hereditary Captaincies]] system to effectively occupy its new colony, and later took direct control of the failed captaincies.<ref>{{cite web|title=Casa História website - "Colonial Brazil"|url=http://www.casahistoria.net/Brazil.htm#Colonial_Brazi|accessdate=2008-12-12}}</ref> Although temporary [[trading post]]s were established earlier to collect brazilwood, with permanent settlement came the establishment of the [[sugar cane]] industry and its intensive labor. Several early settlements were founded along the coast, among them the colonial capital, [[Salvador, Brazil|Salvador]], established in 1549 at the [[Bay of All Saints]] in the north, and the city of [[Rio de Janeiro]] on March 1567, in the south. The Portuguese colonists adopted an economy based on the production of agricultural goods for export to Europe. Sugar became by far the most important Brazilian colonial product until the early 18th century.<ref>[http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0013-0117(1963)2%3A16%3A2%3C219%3AAT1%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Q JSTOR: Anglo-Portuguese Trade, 1700-1770]. [[JSTOR]]. Retrieved on 16 August 2007.</ref><ref>Janick, Jules. [http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/history/lecture34/lec34.html Lecture 34]. Retrieved on 16 August 2007</ref> Even though Brazilian sugar was reputed to be of high quality, the industry faced a crisis during the 17th and 18th centuries when the Dutch and the French started to produce sugar in the [[Antilles]], located much closer to Europe, causing sugar prices to fall. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Image:Raposo Tavares.jpg|thumb|150px|Statue of [[António Raposo Tavares]] at the [[Museu Paulista]].]] |

|||

King Dom [[John VI of Portugal|João VI]] returned to Europe in 26 April, 1821, leaving his elder son Dom [[Pedro I of Brazil|Pedro]] as regent to rule Brazil.<ref>Lustosa, pp.109-110</ref> The Portuguese government attempted to turn Brazil into a colony once again, thus depriving it of its achievements since 1808.<ref>Lustosa, pp.117-119</ref> The Brazilians refused to yield and Prince Pedro stood by their side declaring the country's independence from Portugal in September 7, 1822.<ref>Lustosa, pp.150-153</ref> On October 12, 1822, Pedro was acclaimed first Emperor of Brazil as Dom Pedro I and crowned on 1 December 1822.<ref>Vianna, p.418</ref> In 1822 almost all Brazilians were in favor of a monarchical form of government. [[Republicanism]] was an ideal supported by few individuals at that moment of the Brazilian history.<ref>Holanda (O Brasil Monárquico: o processo de emancipação), p.403 "... o que sabemos é que a idéia republicana no percurso da independência, pelo menos depois de 1821, foi um devaneio de poucos."</ref> The subsequent [[Brazilian Declaration of Independence|Brazilian War of Independence]] expanded through almost its entire territory, with battles that were fought in the northern<ref>Diégues 2004, p. 168</ref>, northeastern<ref>Diégues 2004, p. 164</ref> and southern<ref>Diégues 2004, p. 178</ref> regions of Brazil. The last Portuguese army surrendered in March 8, 1824<ref>Diégues 2004, pp. 179–180</ref> and Brazilian independence was recognized by Portugal in November 25, 1825.<ref>Lustosa, p.209</ref> |

|||

During the 17th century, private explorers from [[São Paulo (state)|São Paulo]] Captaincy, now called [[Bandeirantes]], explored and expanded Brazil's borders, mainly while raiding the hinterland tribes to enslave native Brazilians.<ref>[http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/51530/bandeira Bandeira (Brazilian history)]. Britannica Online Encyclopedia.</ref> In the 18th century, the Bandeirantes found gold and diamond deposits in the modern-day state of Minas Gerais. Profits from the development of these deposits were mostly used to finance the Portuguese Royal Court's expenditure on the preservation of its [[Global Empire]] and the support of its luxurious lifestyle. The way in which such deposits were exploited by the Portuguese Crown and the powerful local elites burdened colonial Brazil with excessive taxation, giving rise to some popular independence movements such as the [[Tiradentes]] in 1789; however, the secessionist movements were often dismissed by the colonial authorities. Gold production declined towards the end of the 18th century, beginning a period of relative stagnation in Brazil's hinterland.<ref>Maxwell, Kenneth R. ''Conflicts and Conspiracies: Brazil and Portugal 1750-1808''. Cambridge University Press: 1973.</ref> Both [[Indigenous peoples in Brazil|Amerindian]] and [[Afro-Brazilian|African]] [[slave]]s' man power were largely used in Brazil's colonial economy.<ref>[http://www.labhstc.ufsc.br/pdf2007/16.16.pdf Slavery in Brazil] retrieved on 19 August 2007.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Independência ou Morte.jpg|thumb|right|220px|Declaration of the [[Brazilian Declaration of Independence|Brazilian independence]] by Emperor [[Pedro I of Brazil|Dom Pedro I]] in September 7, 1822.]] |

|||

The first Brazilian constitution was promulgated in 25 March 1824, after its acceptance by the municipal councils across the country.<ref>Vianna, p.140</ref><ref>Carvalho (1993), p.23</ref><ref>Calmon (2002), p.189</ref><ref name="Vainfas, p.170">Vainfas, p.170</ref> It was “a highly advanced charter for the time where it was elaborated”<ref>Vianna, p.431</ref> and had all individual guarantees that would be found in the subsequent Brazilian republican constitutions.<ref>Vainfas, p.171</ref> The government form was a hereditary, constitutional and representative (and after 1847, parliamentary<ref>Carvalho (1993), p.33</ref>) monarchy.<ref>Armitage, p.88</ref> The State was divided in four branches: Executive, Legislative, Judiciary and Moderating (or [[Royal Prerogative]])<ref name="Vainfas, p.170"/> – the latter, responsible for the “consolidation of the national unit and for the stability of the Empire’s political system”.<ref>Bonavides (1978), p.233</ref> |

|||

The Brazilian defeat in the [[Argentina-Brazil War]] resulting in the loss of Cisplatine (nowadays [[Uruguay]]),<ref>Vainfas, p.322</ref> Pedro I incapacity in dealing with a representative system where he would have to take in account the opinion of the parliamentary opposition<ref>Vainfas, p.197</ref> and the provincial desire for a higher decentralization<ref> Dohlnikoff, pp.60-61</ref> all contributed for lowering his prestige among the Brazilians. But the main reason for his abdication was due to his continuous interest in the succession crisis in Portugal.<ref>Lustosa, p.278</ref> The emperor refused the Portuguese crown in favor of his [[Maria II of Portugal|eldest daughter]] in 1826,<ref>Lustosa, p.221</ref> but his brother [[Michael I of Portugal|Dom Miguel]] usurped the throne.<ref>Lustosa, p.280</ref> For the surprise, and against the will, of the Brazilians,<ref>Vianna, p.448 “levando a sua renúncia ao Trono, em favor do filho, o Príncipe Imperial D. Pedro de Alcântara. Agiu, portanto, por sua livre vontade, uma vez que o pronunciamento popular e militar não tinha esse objetivo, destinando-se a volta do Gabinete de março.”</ref><ref>Janotti, p. 180 “Caiu o primeiro monarca – e a bem dizer a verdade por que ele abdicou e não por que quisessem que ele abdicasse – mas a Monarquia não caiu”.</ref><ref>Calmon (2002), p.207</ref> Pedro I abdicated in 7 April 1831 and departed to Europe to [[Liberal Wars|reclaim his daughter’s crown]] leaving behind his son and heir who became [[Pedro II of Brazil|Dom Pedro II]].<ref> Lyra (v.1), p.17</ref> |

|||

In contrast to the neighboring Spanish possessions in South America, the Portuguese colony of Brazil kept its territorial, political and linguistic integrity, through the efforts of the colonial Portuguese administration. Although the colony was threatened by other nations during the era of Portuguese rule, in particular by the [[Netherlands|Dutch]] and the French, the authorities and the people ultimately managed to protect its [[Borders of Brazil|borders]] from foreign attacks. Portugal even sent [[bullion]] (a rare naturally occurring [[metal]]lic chemical element of high economic value) to Brazil, a spectacular reversal of the colonial trend, in order to protect the integrity of the colony.<ref>Kenneth R. Maxwell, [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-1615(197410)31%3A2%3C221%3ACACBAP%3E2.0.CO%3B2-L Conflicts and Conspiracies: Brazil and Portugal 1750-1808 (p. 216)], [[JSTOR]]</ref> |

|||

=== |

===Emperor Pedro II reign=== |

||

{{NPOV|date=October 2009}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Image:Fala do trono.jpg|left|thumb|[[Imperial Family of Brazil|Emperor]] [[Pedro II of Brazil|Dom Pedro II of Brazil]] in 1873. ''Fala do Trono'', by [[Pedro Américo]].]] |

|||

[[File:Pedro II of Brazil 1853.jpg|thumb|right|220px|Emperor [[Pedro II of Brazil|Dom Pedro II]] at age 27, 1853. For "the longevity of his government and the transformations that occurred in its course, no other Head of State has marked more deeply the history of the country."<ref>Carvalho (2007), p.9</ref>]] |

|||

As the new emperor could not exert his constitutional prerogatives as Emperor ([[Politics of the Empire of Brazil#Executive branch|Executive]] and [[Politics of the Empire of Brazil#Moderating branch|Moderating Power]]) until he reached majority, a [[Regent|regency]] was created.<ref>Carvalho 2007, p.21</ref> Disputes between political factions that led to rebellions resulted in an unstable, almost anarchical, regency.<ref name="Dohlnikoff, p.206">Dohlnikoff, p.206</ref> The rebellious factions, however, continued to uphold the throne of Pedro II as a way of giving the appearance of legitimacy to their actions (that is, they were not in revolt against the monarchy, but against the uneven social structure that it imposed).<ref name="RIBEIRO, Darcy 2008">RIBEIRO, Darcy. O Povo Brasileiro, Companhia de Bolso, fourth reprint, 2008 (2008).</ref> The [[Cabanagem]] (from 30 to 40% of the population of the Province of [[Grão-Pará]] was killed),<ref>"A hora da desforra", por Júlio José Chiavenato, Revista História Viva, nº 45, páginas 84 a 91.</ref><ref name="Carvalho 2007, p.43"/> the [[Sabinada]]<ref name="Carvalho 2007, p.43">Carvalho (2007), p.43</ref> and the [[Balaiada]],<ref name="Carvalho 2007, p.43"/><ref>Souza, p.326</ref> all followed this course, even though some declared the secession of the provinces as independent republics (but only so long as Pedro II was a minor).<ref>Janotti, p.171 "No Pará, [...] declarou-se que a província não reconheceria o Governo da Regência durante a menoridade do Imperador (1835); começava a ''Cabanagem'', para durar até 1840." and p.172 "explodia em novembro de 1837 a ''Sabinada'' que, declarava-se em ''Estado Republicano Independente'' [...], limitava o tempo da separação até o advento da maioridade de D. Pedro II."</ref> The "generation of politicians who had come to power in the 1830s, following upon the abdication of Pedro I, had learned from bitter experience the difficulties and dangers of government. By 1840 they had lost all faith in their ability to rule the country on their own. They accepted Pedro II as an authority figure whose presence was indispensable for the country's survival."<ref>Barman, p.317</ref> |

|||

Thus, Pedro II was prematurely declared of age and “Brazil was to enjoy nearly half a century of internal peace and rapid material progress.”<ref>Munro, p.273</ref> From then "onward the Empire’s stability and prosperity when compared to the turmoil and poverty of the Spanish American republics gave ample proof” of the emperor’s successful government<ref>Barman (1999), p.307</ref> “with all the freedom permitted by an extremely broad-minded and tolerant policy toward the press.”<ref>Munro, p.274</ref> Brazilian economic growth, especially after 1850, compared "very well" with that of with the United States and the European countries.<ref>Fausto (2005), p.50</ref> The absolute value of the exports of the Empire was the highest in Latin America<ref>Fausto (2005), p. 47</ref> and the country held undisputed hegemony over all the region until its end.<ref>Lyra (v.2), p.9</ref> Brazil also won three international wars during his long reign of 58 years ([[Platine War]],<ref>Lyra (v.1),p.164</ref> [[Uruguayan War]]<ref>Lyra (v.1),p.225</ref> and [[War of the Triple Alliance]],<ref>"[http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/442711/War-of-the-Triple-Alliance War of the Triple Alliance]". Britannica Online Encyclopedia.</ref> which left more than 300,000 dead).<ref>Lyra (v.1),p.272</ref> |

|||

In 1808, the Portuguese court, fleeing from [[Napoleon I of France|Napoleon]]'s troops who were invading Portugal and most of [[Central Europe]], [[Transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil|established themselves]] in the city of [[Rio de Janeiro]], which thus became the seat of government of Portugal and the entire [[Portuguese Empire]], even though it was located outside of Europe. Rio de Janeiro was the capital of the Portuguese empire from 1808 to 1815, while Portugal repelled the French invasion in the [[Peninsular War]]. After that, the [[United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves]] (1815–1825) was created with [[Lisbon]] as its capital. After João VI returned to Portugal in 1821, his heir-apparent [[Pedro I of Brazil|Pedro]] became regent of the Kingdom of Brazil, within the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. Following a series of [[Brazilian Declaration of Independence|political incidents and disputes]], Brazil achieved its independence from Portugal on 7 September 1822. On 12 October 1822, Dom Pedro became the first Emperor of Brazil, being crowned on 1 December 1822. Portugal recognized Brazil as an independent country in 1825. |

|||

During the reign of Pedro II, the Brazilian economy was dependent on the export of [[coffee]]. The economic center was concentrated in the provinces of [[Minas Gerais]], [[Rio de Janeiro (state)|Rio de Janeiro]] and [[São Paulo (state)|São Paulo]]. The rest of the country had a poor and stagnant economy.<ref name="RIBEIRO, Darcy 2008"/> Work force on coffee plantations was based on [[Slavery in Brazil|African slavery]].<ref name="RIBEIRO, Darcy 2008"/> The emperor, who never owned slaves,<ref>Barman (1999), p.194</ref> also led the abolitionist campaign<ref>Lyra (v.3), pp.29-30</ref> that eventually extinguished slavery after a slow but steady process that went from the end of international traffic in 1850<ref> Lyra (v.1), p.166</ref> up to the complete abolition in 1888.<ref>Lyra (v.3), p.62</ref> The reign of Pedro II was the period that Brazil imported the largest numbers of slaves from Africa, and in [[1864]] as many as 1,715,000 people were living under slavery in Brazil.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ibge.gov.br/brasil500/tabelas/negros_regioes.htm |title=Slave population in Brazil IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) |publisher=Ibge.gov.br |date= |accessdate=2009-10-29}}</ref> Brazil was the last Western country to abolish slavery,<ref>{{Cite book | title = História Econômica da Primeira República - Volume 3 | date = 2002 | publisher = EDUSP | location = | isbn = 978-85-314-0689-8 | url=http://books.google.com.br/books?id=Sfs_8KASx4EC&pg=PA22&lpg=PA22&dq=brazil+last+country+abolish+slavery&source=bl&ots=laZRDlGn92&sig=NcylhWWj1Gwb2liqgOVNxm5e82E&hl=pt-BR&ei=7ZbnSsxo0Yu2B9OfifsG&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=9&ved=0CCsQ6AEwCA#v=onepage&q=brazil%20last%20country%20abolish%20slavery&f=false |page = 22 }}</ref> because the Emperor did not want to risk antagonizing slave owners, who formed the elite of the country.{{OR?}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/78101/Brazil/25041/The-Brazilian-Empire |title=Encyclopedia Britannica The Brazilian Empire |publisher=Britannica.com |date= |accessdate=2009-10-30}}</ref>{{citation needed}} By the end of the 19th century, most of the Brazilian population was composed of people of African descent.<ref>[http://www.ibge.gov.br/brasil500/negros/popnegra.html Black and Brown population in Brazilian censuses (IBGE)]</ref> |

|||

In 1824, Pedro closed the Constituent Assembly, stating that the body was "endangering liberty." Pedro then produced a constitution modeled on that of Portugal (1822) and France (1814). It specified indirect elections and created the legislative, executive and judicial branches of government; however, it also added a fourth branch, the "moderating power", to be held by the Emperor. Pedro's government was considered economically and administratively inefficient. Political pressures eventually made the Emperor step down on 7 April 1831. He returned to Portugal leaving behind his five-year-old son [[Pedro II of Brazil|Pedro II]]. Until Pedro II reached maturity, Brazil was governed by regents from 1831 to 1840. The regency period was turbulent and marked by numerous local revolts including the [[Male Revolt|Malê Revolt]],<ref>[http://isc.temple.edu/evanson/brazilhistory/Bahia.htm Rebelions in Bahia, 1798-l838]</ref> the largest urban [[slave rebellion]] in the Americas, which took place in Bahia in 1835.<ref>Reis, João José. ''Slave Rebellion in Brazil — The Muslim Uprising of 1835 in Bahia''. Translated by Arthur Brakel. Johns Hopkins University Press.</ref> The [[Cabanagem]], one of the bloodiest revolts ever in Brazil, which was chiefly directed against the white ruling class, reduced the population of [[Pará]] from about 100,000 to 60,000.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://noticias.uol.com.br/licaodecasa/materias/fundamental/historia/brasil/ult1689u20.jhtm|title=Cabanagem (1835-1840): Uma das mais sangrentas rebeliões do período regencial|work=[[Universo Online]] Liçao de Casa|author=Renato Cancian|accessdate=2007-11-12|language=Portuguese}}</ref> |

|||

Brazil was a “prosperous and [internationally] respected” country<ref>Lima, p.87</ref> when the monarchy was overthrown in November 15, 1889.<ref name="Munro, p.280">Munro, p.280</ref> There was no desire in Brazil (at least among the majority of its population) to change the [[form of government]]<ref>Ermakoff, p.189 "Não havia, portanto, clamor pela mudança do regime de governo, exceto alguns gritos de "Viva a República", entoados por pequenos grupos de militantes à espreita da passagem da carruagem imperial."</ref> and Pedro II was on the height of his popularity among his subjects.<ref>Schwarcz, p.444</ref><ref>Vainfas, p.201</ref> Pedro II, however, “bore prime, perhaps sole, responsibility for his own overthrown.”<ref>Barman (1999), p.399</ref> After the death of his two male sons, he believed that “the imperial regime was destined to end with him.”<ref>Barman (1999), p.130</ref> The emperor did not care about its fate<ref>Lyra (v.3), p.126</ref><ref>Barman (1999), p.361</ref> and did nothing (nor allowed anyone) to prevent the military coup<ref>Lyra (v.3), p.99</ref> that was backed by former slave owners that resented the abolition of slavery.<ref>Schwarcz, pp.450 and 457</ref> The monarchist reaction after the fall of the empire “was not small and even less its repression”.<ref>Salles, p.194</ref> |

|||

[[File:Flag of the Second Empire of Brazil.svg|thumb|right|Banner of the Empire of Brazil]] |

|||

On 23 July 1840, Pedro II was crowned Emperor. His government was marked by a substantial rise in [[coffee]] exports, the [[War of the Triple Alliance]], which left more than 300,000 dead,<ref>[http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/442711/War-of-the-Triple-Alliance War of the Triple Alliance]. Britannica Online Encyclopedia.</ref> and the end of [[History of slavery|slave trade]] from Africa in 1850, although [[slavery]] in Brazilian territory would only be abolished in 1888. By the Eusébio de Queirós law,<ref>Leslie Bethell, [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-1953(197122)2%3A1%3C198%3ATAOTBS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-5 The Abolition of the Brazilian Slave Trade: Britain, Brazil, and the Slave Trade Question, 1807-1969], [[JSTOR]]</ref> Brazil stopped [[Atlantic slave trade|trading slaves from Africa]] in 1850. Slavery was abandoned altogether in 1888, thus making Brazil the last country of the Americas to ban slavery.<ref>[http://forests.org/shared/reader/welcome.aspx?linkid=9263 Brazil's Prized Exports Rely on Slaves and Scorched Land] Larry Rohter (2002) New York Times, 25 March</ref><ref>Anstey, Roger: The Atlantic Slave Trade and British abolition, 1760-1810. London: Macmillan, 1975.</ref> When slavery was finally abolished, a large influx of European immigrants took place.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/latam/SLAVERY-ABOLITION.html |title=Slavery and Abolition |date= |quote=A Journal of Comparative Studies |accessdate=2007-07-19}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://http.gogobrazil.com/angloirishpress.html |title=Links between Brazil & Ireland |year=2004 |quote= Aspects of an Economic and Political Controversy between Great Britain and Brazil, 1865-1870. |accessdate=2007-07-19}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-216X(196911)1%3A2%3C115%3ATIOBAT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-S |title=JSTOR |date= |quote=The Independence of Brazil and the Abolition of the Brazilian Slave Trade: Anglo-Brazilian Relations, 1822-1826 |accessdate=2007-07-19}}</ref> By the 1870s, the Emperor's control of domestic politics had started to deteriorate in the face of crises with the Catholic Church, the Army and the slaveholders. The Republican movement slowly gained strength. The dominant classes no longer needed the empire to protect their interests and deeply resented the [[abolitionism|abolition of slavery]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ciaonet.org/atlas/countries/br_data_loc.html#a4 |title=CIAO Atlas |date= |quote=The Empire, 1822-89 |accessdate=2007-06-23}}</ref> Indeed, imperial centralization ran counter to their desire for local autonomy. By 1889 Pedro II had stepped down and the Republican system had been adopted in Brazil. In the end, the empire really fell because of a coup d'état. |

|||

===Republic=== |

===Old Republic and Vargas dictatorship=== |

||

[[File:Revolução de 1930.jpg|thumb|220px|right|The Brazilian coup d'état of 1930 raised [[Getúlio Vargas]] (center) to power. He would rule the country for fifteen years as a fascist dictator. Although Vargas led a highly repressive order, he "contributed with undeniable advances for the development of the country".<ref>Ferreira, p.14</ref>]] |

|||

{{Main|Estado Novo (Brazil)|Brazilian Second Republic|Military dictatorship (Brazil)|History of Brazil (1964–1985)|History of Brazil since 1985}} |

|||

The [[Brazilian people|Brazilian population]] practically had no involvement in the change from [[Monarchy]] to [[Republic]], which was conducted by the small [[elite]] of the country. In fact, the same elite of land owners that ruled Brazil during the Empire continued to dominate the country after the Proclamation of the Republic.<ref name="RIBEIRO, Darcy 2008"/> The [[socioeconomic]] structure of Brazil remained virtually untouched: the economy continued [[Agriculture|agrarian]] and dependent on [[coffee]] exports. The slave manpower was replaced by the labor force of [[Immigration to Brazil|European immigrants]] attracted to the country. The productive lands remained in the hands of the same [[aristocracy]], forcing the majority of Brazilians to work for those land owners in poor conditions, while thousands of Brazilians were compelled to migrate to urban centers in order to escape from [[poverty]] and from the arbitrariness of land owners. This massive [[rural exodus]] has formed a huge [[underemployed]] population in cities, creating large pockets of poverty ([[favela]]s).<ref name="RIBEIRO, Darcy 2008"/> The early republican government “was little more than a military dictatorship. The army dominated affairs both at Rio de Janeiro and in the states. Freedom of the press disappeared and elections were controlled by those in power”.<ref name="Munro, p.280"/> In 1894 the republican civilians rose to power, opening a “prolonged cycle of civil war, financial disaster, and government incompetence.”<ref name="Barman 1999, p.403">Barman (1999), p.403</ref> By 1902, the government "began a return to the policies pursued during the Empire, policies that promised peace and order at home and a restoration of Brazil’s prestige abroad.”<ref name="Barman 1999, p.403"/> [[Baron of Rio Branco|José Paranhos Júnior, the Baron of Rio Branco]] was appointed minister of foreign relations and was highly successful in negotiating several treaties that expanded and secured the Brazilian boundaries<ref>Barman (1999), p.404</ref> but failed to reinstate the country’s prominence in Latin America.<ref>Doratioto (2005), p.27</ref> |

|||

[[File:Lula - foto oficial05012007 edit.jpg|thumb|right|[[Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva]], current President of the Federative Republic of Brazil]] |

|||

[[Image:Chamber of Deputies of Brazil 2.jpg|thumb|left|The [[Chamber of Deputies of Brazil]], the [[lower house]] of the [[Congresso Nacional|National Congress]].]] |

|||

A military junta took control in 1930. [[Getúlio Vargas]] took office soon after and remained as dictatorial ruler until 1945. He was re-elected in 1951 and stayed in office until his suicide in 1954. During this period Brazil also took part in [[Brazil during World War I|World War I]] and [[Brazilian Expeditionary Force|World War II]]. After 1930, successive governments continued industrial and agricultural growth and the development of the vast interior of Brazil.<ref name=uscongress>U.S. Library of Congress, Federal Research Division, Country Studies: Brazil, [http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+br0022) "The Era of Getúlio Vargas, 1930-54"]</ref><ref>Valença, Márcio M. [http://www.lse.ac.uk/collections/geographyAndEnvironment/research/Researchpapers/rp58.pdf "Patron-Client Relations and Politics in Brazil: A Historical Overview"]. Retrieved June 16, 2007.</ref> |

|||

===Military dictatorship and Contemporary era=== |

|||

The military took office in Brazil in a [[1964 Brazilian coup d'état|coup d'état in 1964]] and remained in power until March 1985, when it fell from grace because of political struggles between the regime and the Brazilian elites. In 1967 the name of the country was changed to ''Federative Republic of Brazil''. Just as the Brazilian regime changes of 1889, 1930, and 1945 unleashed competing political forces and caused divisions within the military, so too did the 1964 regime change.<ref>CasaHistória website, [http://www.casahistoria.net/Brazil.htm#Military_Rule "Military Rule"]. Retrieved June 12, 2007.</ref> Democracy was re-established in 1988 when the current Federal Constitution was enacted.<ref>{{cite web |title=Election Resources on the Internet: Federal Elections in Brazil |url=http://electionresources.org/br/index_en.html |date=2006-10-30 |author=Manuel Álvarez-Rivera |accessdate=2007-06-20}}</ref> [[Fernando Collor de Mello]] was the first president truly elected by popular vote after the military regime.<ref name=Gover>{{cite web |url=http://www.brasil.gov.br/ingles/about_brazil/history/xx_cent/ | publisher=Brazilian Government website |title=20th century (1990-1992 The Collor Government) |accessdate=2007-06-20}}</ref> Collor took office in March 1990. In September 1992, the National Congress voted for Collor's impeachment after a sequence of scandals were uncovered by the media.<ref name=Gover/><ref>{{cite web |url=http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-1937(1993)35%3A1%3C1%3ATRAFOP%3E2.0.CO%3B2-0 |title=The Rise and Fall of President Collor and Its Impact on Brazilian Democracy | publisher=JSTOR | accessdate=2007-07-19}}</ref> The vice-president, [[Itamar Franco]], assumed the presidency. Assisted by the Minister of Finance at that time, [[Fernando Henrique Cardoso]], Itamar Franco's administration implemented the [[Plano Real]] economic package,<ref name=Gover/> which included a new currency temporarily pegged to the U.S. dollar, the [[Brazilian real|''real'']]. In the elections held on 3 October 1994, Fernando Henrique Cardoso ran for president and won, being reelected in 1998. Brazil's current president is [[Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva]], elected in 2002 and reelected in 2006. |

|||

[[File:1964coupRJ.jpg|thumb|left|220px|The 1964 coup d'état began a dictatorship that lasted until 1985, the longest in Brazilian history.]] |

|||

[[Juscelino Kubitschek de Oliveira|Juscelino Kubitschek]]'s office years (1956–1961) were marked by the political campaign motto ''"50 anos em 5"'' ({{lang-en|fifty years of development in five}}).<ref>{{cite web |title=Plano de Metas criado por JK foi um marco da economia brasileira |date=2006-02-17 |url=http://aol.universiabrasil.net/materia/materia.jsp?materia=10094 |author=Renato Marques |language=Portuguese |accessdate=2007-08-12 }}</ref> |

|||

The military took office in Brazil in a [[1964 Brazilian coup d'état|coup d'état in 1964]] and remained in power until March 1985, when it fell from grace because of political struggles between the regime and the Brazilian elites. In 1967 the name of the country was changed to ''Federative Republic of Brazil''. Just as the Brazilian regime changes of 1889, 1930, and 1945 unleashed competing political forces and caused divisions within the military, so too did the 1964 regime change.<ref>CasaHistória website, [http://www.casahistoria.net/Brazil.htm#Military_Rule "Military Rule"]. Retrieved June 12, 2007.</ref> |

|||

The civilians fully returned to power in 1985 when [[José Sarney]] assumed the presidency.<ref>Fausto (2005), p.460</ref> His government was deemed a failure due to the uncontrollable economic crisis and unusually high inflation that resulted in his extreme unpopularity.<ref>Fausto (2005), pp.464-465</ref> That allowed the election in 1989 of the almost unknown nationwide [[Fernando Collor]], <ref>Fausto (2005), p.465</ref> who was impeached by the National Congress in 1992.<ref>Fausto (2005), p.475</ref> He was succeeded by his Vice-President [[Itamar Franco]], who called [[Fernando Henrique Cardoso]] to assume the Ministry of Finance portfolio. Cardoso was highly successful with his [[Plano Real]] (Royal Plan)<ref>The name of the current Brazilian currency came from an older currency that existed up to 1942. In Portuguese it is called "Real", but it does not come from "realism", but istead, from "royal", as its origins are from Portugal when it was a monarchy.</ref> that granted stability to the Brazilian economy<ref>Fausto (2005), p.482</ref> and his efforts were recognized when he was elected president in 1994 and again in 1998.<ref>Fausto (2005), p.474</ref> The peaceful and warmly transition from power to [[Luís Inácio Lula da Silva]], who was elected in 2002 (and re-elected in 2006), revealed that Brazil had finally succeeded in achieving its long sought political stability.<ref>Fausto (2005), p.502</ref> |

|||

==Government and politics== |

==Government and politics== |

||

Revision as of 01:35, 4 November 2009

Federative Republic of Brazil [República Federativa do Brasil] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Template:Pt icon | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Ordem e Progresso" Template:Pt icon "Order and Progress" | |

| Anthem: Hino Nacional Brasileiro Template:Pt icon "Brazilian National Anthem" | |

| National seal Selo Nacional do Brasil Template:Pt icon "National Seal of Brazil" | |

| |

| Capital | Brasília |

| Largest city | São Paulo |

| Official languages | Portuguese (see Languages of Brazil) |

| Ethnic groups | 49.4% White 42.3% Pardo (Brown) 7.4% Black 0.5% Asian 0.4% Amerindian |

| Demonym(s) | Brazilian |

| Government | Presidential Federal republic |

| Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) | |

| José Alencar (PRB) | |

| Michel Temer (PMDB) | |

| José Sarney (PMDB) | |

| Gilmar Mendes | |

| Independence from Portugal | |

• Declared | September 7, 1822 |

| August 29, 1825 | |

• Republic | November 15, 1889 |

| October 5, 1988 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 8,514,877 km2 (3,287,612 sq mi) (5th) |

• Water (%) | 0.65 |

| Population | |

• 2009 estimate | 191,241,714[1] (5th) |

• 2007 census | 189,987,291 |

• Density | 22/km2 (57.0/sq mi) (182nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2008 estimate |

• Total | $1.984 trillion[2] (9th) |

• Per capita | $10,465[2] (77th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2008 estimate |

• Total | $1.665 trillion [3] (8th) |

• Per capita | $8,295[2] (63rd) |

| Gini (2009) | 49.3[4] Error: Invalid Gini value |

| HDI (2007) | 0.813[5] Error: Invalid HDI value (75th) |

| Currency | Real (R$) (BRL) |

| Time zone | UTC-2 to -4[6] (BRT [7]) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC-2 to -4 (BRST [8]) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (CE) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +55 |

| ISO 3166 code | BR |

| Internet TLD | .br |

Brazil (Portuguese: Brasil), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: República Federativa do Brasil) , is the largest country in South America and the only Portuguese-speaking country on that continent.[9] It is the fifth largest country by geographical area, occupying nearly half of South America[10] and the fifth most populous country in the world.[9][11]

Bounded by the Atlantic Ocean on the east, Brazil has a coastline of over Template:Km to mi.[9] It is bordered on the north by Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and the French overseas department of French Guiana; on the northwest by Colombia; on the west by Bolivia and Peru; on the southwest by Argentina and Paraguay and on the south by Uruguay. Numerous archipelagos are part of the Brazilian territory, such as Fernando de Noronha, Rocas Atoll, Saint Peter and Paul Rocks, and Trindade and Martim Vaz.[9]

Brazil was a colony of Portugal from the landing of Pedro Álvares Cabral in 1500 until its independence in 1822.[12] Initially independent as the Brazilian Empire, the country has been a republic since 1889, although the bicameral legislature, now called Congress, dates back to 1824, when the first constitution was ratified.[12] Its current Constitution defines Brazil as a Federal Republic.[13] The Federation is formed by the union of the Federal District, the 26 States, and the 5,564 Municipalities.[13][14]

Brazil is the world's eighth largest economy at market exchange rates[3] and the ninth largest by purchasing power parity.[15] Economic reforms have given the country new international recognition.[16] It is a founding member of the United Nations and the Union of South American Nations. A predominantly Roman Catholic, Portuguese-speaking, and multiethnic society,[11] Brazil is also home to a diversity of wildlife, natural environments, and extensive natural resources in a variety of protected habitats.[9]

Etymology

The etymology of the name Brazil is not well established. The most accepted is that it was named after the tree brazilwood[17] which in Portuguese is pau-brasil, and the word brasil is commonly defined by the dictionaries of different languages as the color of red like ember, formed by the word brasa (ember) plus the suffix -il* (from iculum or ilium).[18][19][20] Another possibility, is the Irish legendary island of Hy-Brazil, known to Western European sailors in the 1500s[21] and popularized in its current spelling by Italian cartographer Angelinus Alorto's 1325 map "L'Isola Brazil."[22] Its origin comes from the celtic word "bress" that means "to bless" which named the mythical island Hy Brazil or "Bresail" (Blessed land). The "scholars from the 16th century did not doubt that the name Brazil came from the legendary island", but the wrongly held belief that it had been named after the wood came from the sailors that trafficked it.[23]

Geography

Brazil occupies a large area along the eastern coast of South America and includes much of the continent's interior region,[24] sharing land borders with Uruguay to the south; Argentina and Paraguay to the southwest; Bolivia and Peru to the west; Colombia to the northwest; Venezuela, Suriname, Guyana and the French overseas department of French Guiana to the north.[9] Brazil shares a border with every country in South America, except for Ecuador and Chile. The factors of size, relief, climate, and natural resources make Brazil geographically diverse.[24] Brazil is the fifth largest country in the world—after Russia, Canada, China and the United States—and third largest in the Americas; with a total area of Template:Km2 to mi2, including Template:Km2 to mi2 of water.[9] It spans three time zones; from UTC-4, in the western states; to UTC-3, in the eastern states, the official time of Brazil, and UTC-2, in the Atlantic islands.[25]

Brazilian topography is also diverse, including hills, mountains, plains, highlands, and scrublands. Much of Brazil lies between 200 metres (660 ft) and 800 metres (2,600 ft) in elevation.[26] The main upland area occupies most of the southern half of the country.[26] The northwestern parts of the plateau consist of broad, rolling terrain broken by low, rounded hills.[26] The southeastern section is more rugged, with a complex mass of ridges and mountain ranges reaching elevations of up to 1,200 metres (3,900 ft).[26] These ranges include the Mantiqueira Mountains, the Espinhaço Mountains, and the Serra do Mar.[26] In north, the Guiana Highlands form a major drainage divide, separating rivers that flow south into the Amazon Basin from rivers that empty into the Orinoco River system, in Venezuela, to the north. The highest point in Brazil is the Pico da Neblina at 3,014 metres (9,888 ft), and the lowest point is the Atlantic Ocean.[9] Brazil has a dense and complex system of rivers, one of the world's most extensive, with eight major drainage basins, all of which drain into the Atlantic Ocean.[27] Major rivers include the Amazon, the largest river in terms of volume of water, and the second-longest in the world; the Paraná and its major tributary, the Iguaçu River, where the Iguazu Falls are located; the Negro, São Francisco, Xingu, Madeira and the Tapajós rivers.[27]

Climate

The climate of Brazil comprises a wide range of weather conditions across a large geographic scale and varied topography, but the largest part of the country is tropical.[9] Analysed according to the Köppen system, Brazil hosts five major climatic subtypes: equatorial, tropical, semiarid, highland tropical, and temperate; ranging from equatorial rainforests in the north and semiarid deserts in the northeast, to temperate coniferous forests in the south and tropical savannas in central Brazil.[28] Many regions have starkly different microclimates.[29][30]

An equatorial climate characterizes much of northern Brazil. There is no real dry season, but there are some variations in the period of the year when most rain falls.[28] Temperatures average 25 °C (77 °F),[30] with more significant temperature variations between night and day than between seasons.[29] Over central Brazil rainfall is more seasonal, characteristic of a savanna climate.[29] This region is as large and extensive as the Amazon basin but, lying farther south and being at a moderate altitude, it has a very different climate.[28] In the interior northeast, seasonal rainfall is even more extreme. The semiarid climate region generally receives less than 800 millimetres (31 in) of rain,[31] most of which falls in a period of three to five months[32] and occasionally even more insufficiently, creating long periods of drought.[29] From south of Bahia, near São Paulo, the distribution of rainfall changes, where some appreciable rainfall occurs in all months.[28] The south has temperate conditions, with average temperatures below 18 °C (64 °F) and cool winters;[30] frosts are quite common, with occasional snowfalls in the higher areas.[28][29]

Wildlife

Brazil's large territory comprises different ecosystems, such as the Amazon Rainforest, recognized as having the greatest biological diversity in the world;[33] the Atlantic Forest and the Cerrado, which together sustain some of the world's greatest biodiversity.[34] In the south, the Araucaria pine forest grows under temperate conditions.[34] The rich wildlife of Brazil reflects the variety of natural habitats. Much of it, however, remains largely unknown, and new species are found on nearly a daily basis.[35]

Scientists estimate that the total number of plant and animal species in Brazil could approach four million.[34] Larger mammals include pumas, jaguars, ocelots, rare bush dogs, and foxes. Peccaries, tapirs, anteaters, sloths, opossums, and armadillos are abundant. Deer are plentiful in the south, and monkeys of many species abound in the northern rain forests.[34][36] Concern for the environment in Brazil has grown in response to global interest in environmental issues.[37]

Its natural heritage is extremely threatened by cattle ranching and agriculture, logging, mining, resettlement, oil and gas extraction, over-fishing, expansion of urban centres, wildlife trade, fire, climate change, dams and infrastructure, water contamination, and invasive species.[33] In many areas of the country, the natural environment is threatened by development.[38] Construction of highways has opened up previously remote areas for agriculture and settlement; dams have flooded valleys and inundated wildlife habitats; and mines have scarred and polluted the landscape.[37][39]

History

Native Brazilians and early Portuguese settlers

When arriving in April 1500 in the coast of what would later be known as Brazil, the Portuguese fleet commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral found the primitive inhabitants who inhabited it.[40] They were divided in several distinct tribes, that fought among themselves[41] and that shared the same Tupi-Guarani linguistic family.[40] The “men were hunters, fishers and food collectors and the women were encharged of the reduced agricultural activity that was practiced.”[40] Some of the tribes were nomads and other sedentary; they knew the fire but not metal casting and a few were cannibals.[40]

The settling was effectively initiated in 1534, when King Dom João III divided the Brazilian territory in twelve hereditary captainships that would be governed by members of the lesser nobility or proceeding from educated families.[42] The experience revealed itself to be an utter disaster, and in 1549 the king assigned a governor-general to administrate the entire colony.[43] With the foundation of villages appeared the municipal councils, and consequently, the beginning of the democratic representative system in Brazil.[44] Up to 1549, most of the (few) colonists were exiled men, but from that date and on, the voluntary emigrants (including women and children) became predominant.[45]

Around 1530, the Tupiniquim (the same tribe that Cabral met) and their bitter enemies the Tupinambá, the largest and most important tribes in Brazil, allied themselves with the Portuguese and the French, respectively.[41] Between the Portuguese and the Tupiniquim “occurred a certain intermittently pacific inter-racial assimilation.”[46] While the Tupinambás, however, were mostly exterminated in long wars and mainly by European diseases to which they had no immunities.[47] The ones that survived were enslaved by other tribes or by the Portuguese or fled toward the countryside.[47] By the middle of the 16th century, sugar had become the most important item of the Brazilian exportations.[41] Thus, the Portuguese turned to other forms of man power to handle with the increasing international demand.[47] Enslaved Africans were imported and became the “basic pillar of the economy” in the most populous areas of the colony.[48]

Territorial expansion

Through wars against the French, the Portuguese slowly expanded their territory to the Southeast, taking Rio de Janeiro in 1567, and to the northwest, São Luís in 1615.[49] They suffered a setback with the Dutch invasions that began in 1630 and that managed to conquer large portions of the Brazilian northeastern coastline. The Dutch domain did not last long and they were expelled definitively in 1649.[50] The Portuguese sent military expeditions to the Amazon rainforest that defeated and conquered British and Dutch strongholds. The Portuguese settlement in the region initiated in 1669, with the foundation of villages and forts.[51] In 1680 they reached the far south and founded Sacramento at the side of the Rio de la Plata, in the Eastern Strip region (current Uruguay).[52]

At the end of the 17th century sugar exports entered in decline due to competition with the British and Dutch colonies in the Caribbean and also due to high taxes.[53] The discovery of gold by explorers in the region that would later be called Minas Gerais (General Mines) between 1693 and 1695 saved the colony from its imminent collapse.[54] From all over Brazil, as well from Portugal, thousands of immigrants, from all ethnicities, departed toward the mines.[55] A 20% tax over the gold extraction created dissatisfaction that resulted in an open rebellion in 1720. The Portuguese government suffocated it with relative easiness, assuring its rule over the region for the next seventy years,[56] until the discovery of two small secessionist conspiracies in Minas Gerais and Bahia.[57] In the following decades other gold mines were found in current Mato Grosso and Goiás, in the Brazilian Central-West.[58] The Spanish tried to prevent the Portuguese expansion on the territory belonged to them according to the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494 and succeeded on conquering the Eastern Strip in 1777. All in vain as the Treaty of San Ildefonso signed in the same year confirmed Portuguese domain over all lands proceeding from its territorial expansion, thus creating most of current Brazilian borders.[59]

In 1808, the Portuguese Royal family, fleeing from the troops of the French Emperor Napoleon I that were invading Portugal and most of Central Europe, established themselves in the city of Rio de Janeiro, which thus became the seat of the entire Portuguese Empire[60] In 1815 King Dom João VI, then regent on behalf of his incapacitated mother, elevated Brazil from colony to sovereign Kingdom united with Portugal.[60] The Portuguese invaded French Guiana in 1809 (that was returned to France in 1817)[61] and the Eastern Strip in 1816 that was subsequently renamed Cisplatine.[62]

Independence and Empire

King Dom João VI returned to Europe in 26 April, 1821, leaving his elder son Dom Pedro as regent to rule Brazil.[63] The Portuguese government attempted to turn Brazil into a colony once again, thus depriving it of its achievements since 1808.[64] The Brazilians refused to yield and Prince Pedro stood by their side declaring the country's independence from Portugal in September 7, 1822.[65] On October 12, 1822, Pedro was acclaimed first Emperor of Brazil as Dom Pedro I and crowned on 1 December 1822.[66] In 1822 almost all Brazilians were in favor of a monarchical form of government. Republicanism was an ideal supported by few individuals at that moment of the Brazilian history.[67] The subsequent Brazilian War of Independence expanded through almost its entire territory, with battles that were fought in the northern[68], northeastern[69] and southern[70] regions of Brazil. The last Portuguese army surrendered in March 8, 1824[71] and Brazilian independence was recognized by Portugal in November 25, 1825.[72]

The first Brazilian constitution was promulgated in 25 March 1824, after its acceptance by the municipal councils across the country.[73][74][75][76] It was “a highly advanced charter for the time where it was elaborated”[77] and had all individual guarantees that would be found in the subsequent Brazilian republican constitutions.[78] The government form was a hereditary, constitutional and representative (and after 1847, parliamentary[79]) monarchy.[80] The State was divided in four branches: Executive, Legislative, Judiciary and Moderating (or Royal Prerogative)[76] – the latter, responsible for the “consolidation of the national unit and for the stability of the Empire’s political system”.[81]

The Brazilian defeat in the Argentina-Brazil War resulting in the loss of Cisplatine (nowadays Uruguay),[82] Pedro I incapacity in dealing with a representative system where he would have to take in account the opinion of the parliamentary opposition[83] and the provincial desire for a higher decentralization[84] all contributed for lowering his prestige among the Brazilians. But the main reason for his abdication was due to his continuous interest in the succession crisis in Portugal.[85] The emperor refused the Portuguese crown in favor of his eldest daughter in 1826,[86] but his brother Dom Miguel usurped the throne.[87] For the surprise, and against the will, of the Brazilians,[88][89][90] Pedro I abdicated in 7 April 1831 and departed to Europe to reclaim his daughter’s crown leaving behind his son and heir who became Dom Pedro II.[91]

Emperor Pedro II reign

As the new emperor could not exert his constitutional prerogatives as Emperor (Executive and Moderating Power) until he reached majority, a regency was created.[93] Disputes between political factions that led to rebellions resulted in an unstable, almost anarchical, regency.[94] The rebellious factions, however, continued to uphold the throne of Pedro II as a way of giving the appearance of legitimacy to their actions (that is, they were not in revolt against the monarchy, but against the uneven social structure that it imposed).[95] The Cabanagem (from 30 to 40% of the population of the Province of Grão-Pará was killed),[96][97] the Sabinada[97] and the Balaiada,[97][98] all followed this course, even though some declared the secession of the provinces as independent republics (but only so long as Pedro II was a minor).[99] The "generation of politicians who had come to power in the 1830s, following upon the abdication of Pedro I, had learned from bitter experience the difficulties and dangers of government. By 1840 they had lost all faith in their ability to rule the country on their own. They accepted Pedro II as an authority figure whose presence was indispensable for the country's survival."[100]

Thus, Pedro II was prematurely declared of age and “Brazil was to enjoy nearly half a century of internal peace and rapid material progress.”[101] From then "onward the Empire’s stability and prosperity when compared to the turmoil and poverty of the Spanish American republics gave ample proof” of the emperor’s successful government[102] “with all the freedom permitted by an extremely broad-minded and tolerant policy toward the press.”[103] Brazilian economic growth, especially after 1850, compared "very well" with that of with the United States and the European countries.[104] The absolute value of the exports of the Empire was the highest in Latin America[105] and the country held undisputed hegemony over all the region until its end.[106] Brazil also won three international wars during his long reign of 58 years (Platine War,[107] Uruguayan War[108] and War of the Triple Alliance,[109] which left more than 300,000 dead).[110]

During the reign of Pedro II, the Brazilian economy was dependent on the export of coffee. The economic center was concentrated in the provinces of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. The rest of the country had a poor and stagnant economy.[95] Work force on coffee plantations was based on African slavery.[95] The emperor, who never owned slaves,[111] also led the abolitionist campaign[112] that eventually extinguished slavery after a slow but steady process that went from the end of international traffic in 1850[113] up to the complete abolition in 1888.[114] The reign of Pedro II was the period that Brazil imported the largest numbers of slaves from Africa, and in 1864 as many as 1,715,000 people were living under slavery in Brazil.[115] Brazil was the last Western country to abolish slavery,[116] because the Emperor did not want to risk antagonizing slave owners, who formed the elite of the country.[original research?][117][citation needed] By the end of the 19th century, most of the Brazilian population was composed of people of African descent.[118]

Brazil was a “prosperous and [internationally] respected” country[119] when the monarchy was overthrown in November 15, 1889.[120] There was no desire in Brazil (at least among the majority of its population) to change the form of government[121] and Pedro II was on the height of his popularity among his subjects.[122][123] Pedro II, however, “bore prime, perhaps sole, responsibility for his own overthrown.”[124] After the death of his two male sons, he believed that “the imperial regime was destined to end with him.”[125] The emperor did not care about its fate[126][127] and did nothing (nor allowed anyone) to prevent the military coup[128] that was backed by former slave owners that resented the abolition of slavery.[129] The monarchist reaction after the fall of the empire “was not small and even less its repression”.[130]

Old Republic and Vargas dictatorship

The Brazilian population practically had no involvement in the change from Monarchy to Republic, which was conducted by the small elite of the country. In fact, the same elite of land owners that ruled Brazil during the Empire continued to dominate the country after the Proclamation of the Republic.[95] The socioeconomic structure of Brazil remained virtually untouched: the economy continued agrarian and dependent on coffee exports. The slave manpower was replaced by the labor force of European immigrants attracted to the country. The productive lands remained in the hands of the same aristocracy, forcing the majority of Brazilians to work for those land owners in poor conditions, while thousands of Brazilians were compelled to migrate to urban centers in order to escape from poverty and from the arbitrariness of land owners. This massive rural exodus has formed a huge underemployed population in cities, creating large pockets of poverty (favelas).[95] The early republican government “was little more than a military dictatorship. The army dominated affairs both at Rio de Janeiro and in the states. Freedom of the press disappeared and elections were controlled by those in power”.[120] In 1894 the republican civilians rose to power, opening a “prolonged cycle of civil war, financial disaster, and government incompetence.”[132] By 1902, the government "began a return to the policies pursued during the Empire, policies that promised peace and order at home and a restoration of Brazil’s prestige abroad.”[132] José Paranhos Júnior, the Baron of Rio Branco was appointed minister of foreign relations and was highly successful in negotiating several treaties that expanded and secured the Brazilian boundaries[133] but failed to reinstate the country’s prominence in Latin America.[134]

A military junta took control in 1930. Getúlio Vargas took office soon after and remained as dictatorial ruler until 1945. He was re-elected in 1951 and stayed in office until his suicide in 1954. During this period Brazil also took part in World War I and World War II. After 1930, successive governments continued industrial and agricultural growth and the development of the vast interior of Brazil.[135][136]

Military dictatorship and Contemporary era

Juscelino Kubitschek's office years (1956–1961) were marked by the political campaign motto "50 anos em 5" (Template:Lang-en).[137]

The military took office in Brazil in a coup d'état in 1964 and remained in power until March 1985, when it fell from grace because of political struggles between the regime and the Brazilian elites. In 1967 the name of the country was changed to Federative Republic of Brazil. Just as the Brazilian regime changes of 1889, 1930, and 1945 unleashed competing political forces and caused divisions within the military, so too did the 1964 regime change.[138]

The civilians fully returned to power in 1985 when José Sarney assumed the presidency.[139] His government was deemed a failure due to the uncontrollable economic crisis and unusually high inflation that resulted in his extreme unpopularity.[140] That allowed the election in 1989 of the almost unknown nationwide Fernando Collor, [141] who was impeached by the National Congress in 1992.[142] He was succeeded by his Vice-President Itamar Franco, who called Fernando Henrique Cardoso to assume the Ministry of Finance portfolio. Cardoso was highly successful with his Plano Real (Royal Plan)[143] that granted stability to the Brazilian economy[144] and his efforts were recognized when he was elected president in 1994 and again in 1998.[145] The peaceful and warmly transition from power to Luís Inácio Lula da Silva, who was elected in 2002 (and re-elected in 2006), revealed that Brazil had finally succeeded in achieving its long sought political stability.[146]

Government and politics

The Brazilian Federation is based on the union of three autonomous political entities: the States, the Municipalities and the Federal District.[13] A fourth entity originated in the aforementioned association: the Union.[13] There is no hierarchy among the political entities. The Federation is set on six fundamental principles:[13] sovereignty, citizenship, dignity of the people, social value of labor, freedom of enterprise, and political pluralism. The classic tripartite branches of government (executive, legislative, and judicial under the checks and balances system), is formally established by the Constitution.[13] The executive and legislative are organized independently in all four political entities, while the judiciary is organized only in the federal and state levels.

All members of the executive and legislative branches are directly elected.[147][148][149] Judges and other judicial officials are appointed after passing entry exams.[147] Voting is compulsory for those between 18 and 65 years old.[13] Four political parties stand out among several small ones: Workers' Party (PT), Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), and Democrats (formerly Liberal Front Party – PFL). Almost all governmental and administrative functions are exercised by authorities and agencies affiliated to the Executive.

The form of government is that of a democratic republic, with a presidential system.[13] The president is both head of state and head of government of the Union and is elected for a four-year term,[13] with the possibility of re-election for a second successive term. The current president is Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. He was elected on October 27, 2002,[150] and re-elected on October 29, 2006.[151] The President appoints the Ministers of State, who assist in governing.[13] Legislative houses in each political entity are the main source of laws in Brazil. The National Congress is the Federation's bicameral legislature, consisting of the Chamber of Deputies and the Federal Senate. Judiciary authorities exercise jurisdictional duties almost exclusively.

Law

Brazilian law is based on Roman-Germanic traditions.[152] Thus, civil law concepts prevail over common law practices. Most of Brazilian law is codified, although non-codified statutes also represent a substantial part of the system, playing a complementary role. Court decisions set out interpretive guidelines; however, they are not binding on other specific cases except in a few situations. Doctrinal works and the works of academic jurists have strong influence in law creation and in law cases. The legal system is based on the Federal Constitution, which was promulgated on 5 October 1988, and is the fundamental law of Brazil. All other legislation and court decisions must conform to its rules.[153] As of April 2007, there have been 53 amendments. States have their own constitutions, which must not contradict the Federal Constitution.[154] Municipalities and the Federal District do not have their own constitutions; instead, they have "organic laws" ([leis orgânicas] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)).[13][155] Legislative entities are the main source of statutes, although in certain matters judiciary and executive bodies may enact legal norms.[13]

Jurisdiction is administered by the judiciary entities, although in rare situations the Federal Constitution allows the Federal Senate to pass on legal judgments.[13] There are also specialized military, labor, and electoral courts.[13] The highest court is the Supreme Federal Tribunal. This system has been criticised over the last decades due to the slow pace at which final decisions are issued. Lawsuits on appeal may take several years to resolve, and in some cases more than a decade elapses before definitive rulings are made.[156] Nevertheless, Supreme Federal Tribunal is the first court in the world to transmit its sessions on television, and more recently also in Youtube.[157][158]

Foreign relations

Brazil is a political and economic leader in Latin America.[159][160] However, social and economic problems prevent it from becoming an effective global power.[161] Between World War II and 1990, both democratic and military governments sought to expand Brazil's influence in the world by pursuing a state-led industrial policy and an independent foreign policy. More recently, the country has aimed to strengthen ties with other South American countries, engage in multilateral diplomacy through the United Nations and the Organization of American States.[162] Brazil's current foreign policy is based on the country's position as a regional power in Latin America, a leader among developing countries, and an emerging world power.[163] In general current Brazilian foreign policy reflects multilateralism, peaceful dispute settlement, and nonintervention in the affairs of other countries.[164] The Brazilian Constitution also determines the country shall seek the economic, political, social and cultural integration of the nations of Latin America.[13][165][166][167]

Military

The Armed forces of Brazil consist of the Brazilian Army, the Brazilian Navy, and the Brazilian Air Force. The Brazilian military numbers about 300,000 men and women and has a budget of 2.6 percent of the national economy in 2009 or about $52 billion US dollars.[13] The Military Police (States' Military Police) is described as an ancillary force of the Army by the constitution, but is under the control of each state's governor.[13] The Brazilian armed forces are the largest in Latin America. The Brazilian Air Force is the aerial warfare branch of the Brazilian armed forces, the largest air force in Latin America, with about 700 manned aircraft in service.[168] The Brazilian Navy is responsible for naval operations and for guarding Brazilian territorial waters. It is the oldest of the Brazilian Armed forces and the only navy in Latin America to operate an aircraft carrier, the NAe São Paulo (formerly FS Foch of the French Navy).[169] The Brazilian Army is responsible for land-based military operations, with a strength of approximately 190,000 soldiers. In 2008 the Brazilian minister of defense has formulated the “Estratégia Nacional de Defesa” (National defense Strategy), that claims to build a strong national industry and make strategic partnerships with allied nations to develop technology together.[170]

of the Brazilian Navy.

Recently, Brazil has began to emerge as a major world power and a potential superpower; thus Brazil has begun to develop as a major military power. In 2008, Brazil has signed a strategic partnership with France and Russia to trade military technology. Brazil has also begun negotiations with France to have Brazil build 120 Rafale aircraft locally by Embraer.[171] Also in 2008 the Brazilian company Embraer showcased the Brazilian transport aircraft, Embraer KC-390, and some countries already have shown interest in the aircraft, with France even placing orders.[172][173] In 2009 Brazil purchased 4 Scorpène submarines for US $9.9 billion with a massive technology transfer agreement. In a second agreement, France will provide technical assistance to Brazil so that Brazil can design and produce indigenous nuclear powered submarines, to be completely built in Brazil.[174] The Brazilian government has announced that a Helibras factory in Itajubá, Minas Gerais, will initially produce 50 units of the EC 725 and up to 1,300 new helicopters for the Brazilian military. Helibras will now also produce Eurocopter's full line of products, with the first units to be operational in 2010.[175] The Department of Defense of Brazil, in 2009 also asked the Brazilian Navy to develop a plan for the next 30 years. To carry out the plans of power projection that Brazil wants to run, the expenditure will cost more than $138 billion US dollars, within the Navy alone. The program is called PEAMB.[176] The strategy is to buy or build 2 aircraft carriers (40 000 tonnes), 4 Amphibious assault ships (20 000 tonnes), 30 escort ships, 15 submarines, 5 nuclear submarines and 62 (patrol ships).[177] In July 2009, the minister of defense, Nelson Jobim, said that Brazil will expend about 0.7% ($13 billion USD) of the GDP per year to modernize the forces in addition to the 2.6% yearly defense budget. He stated, "We are raising a study to make the financial schedule of the entire project. It will be a 20 year plan, including modernization and expansion of the elements for defense of the Brazilian territory.[178]

Subdivisions

According to the Brazilian Constitution of 1988, Brazil is a federation of 26 states, one federal district and also the municipalities. None of these units has the right to secede from the Federation.[13]

States

States (estados) are based on historical, conventional borders and have developed throughout the centuries, though some boundaries are arbitrary. The states can be split or joined together in new states if their people express a desire to do so in a plebiscite. States have autonomous administrations, collect their own taxes and receive a share of taxes collected by the Federal government. They have a governor and a unicameral legislative body (Assembleia Legislativa) elected directly by their voters. They also have independent Courts of Law for common justice. Despite that, in Brazil states have much less autonomy to create their own laws than in the United States. For example, criminal and civil laws can only be voted by the federal bicameral Congress and are uniform throughout the country.[13]

In 1977, Mato Grosso state was split into two. The northern new state retained the name Mato Grosso and the old capital, Cuiabá, while the southern area became the new state of Mato Grosso do Sul, with Campo Grande as its capital. In 1988, the northern portion of Goiás state became the new state of Tocantins. Initially, the capital of Tocantins was the small city of Miracema do Norte (now called Miracema do Tocantins), but it was later moved to the new city of Palmas.

The equator cuts through the states of Amapá, Pará, Roraima and Amazonas in the North, and the Tropic of Capricorn cuts through the states of São Paulo, northern Paraná and southern Mato Grosso do Sul.[179] Acre is in the far west side of the country, covered by the Amazonian forest. Paraíba is the easternmost state of Brazil; Ponta do Seixas, in the city of João Pessoa, is the easternmost point of continental Brazil and of the Americas. In contrast to the tropical climate of most of Brazil, the southern states of Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul, and Santa Catarina all have a temperate subtropical climate.

The state of Amazonas is the largest in area, comparable in size to Alaska. The state of São Paulo has the largest population and is the economic center of Brazil. Its agriculture, industry, commerce, and services are the most diversified in the nation. Although a large part of its production is exported to other states and other countries, the consumer market of the state is also the biggest in Brazil. In contrast to most of the Brazilian states, the economy of São Paulo is strong even in noncoastal cities.