Seljuk Empire: Difference between revisions

rmv as the protection has expired |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

{{History of Turkey}} |

{{History of Turkey}} |

||

The '''Seljuk Empire''' was a [[medieval]] [[ |

The '''Seljuk Empire''' was a [[medieval]] [[Seljuk Empire|Turkish empire]]<ref> |

||

* "Aḥmad of Niǧde's ''al-Walad al-Shafīq'' and the Seljuk Past", A. C. S. Peacock, ''Anatolian Studies'', Vol. 54, (2004), 97; "With the growth of Seljuk power in Rum, a more highly developed Muslim cultural life, based on the ''Persianate culture'' of the Great Seljuk court, was able to take root in Anatolia." |

* "Aḥmad of Niǧde's ''al-Walad al-Shafīq'' and the Seljuk Past", A. C. S. Peacock, ''Anatolian Studies'', Vol. 54, (2004), 97; "With the growth of Seljuk power in Rum, a more highly developed Muslim cultural life, based on the ''Persianate culture'' of the Great Seljuk court, was able to take root in Anatolia." |

||

* Meisami, Julie Scott, ''Persian Historiography to the End of the Twelfth Century'', (Edinburgh University Press, 1999), 143; "Nizam al-Mulk also attempted to organise the Saljuq administration according to the Persianate Ghaznavid model..." |

* Meisami, Julie Scott, ''Persian Historiography to the End of the Twelfth Century'', (Edinburgh University Press, 1999), 143; "Nizam al-Mulk also attempted to organise the Saljuq administration according to the Persianate Ghaznavid model..." |

||

| Line 114: | Line 114: | ||

* Jonathan Dewald, ''Europe 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World'', Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004, p. 24: "Turcoman armies coming from the East had driven the Byzantines out of much of Asia Minor and established the Persianized sultanate of the Seljuks." |

* Jonathan Dewald, ''Europe 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World'', Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004, p. 24: "Turcoman armies coming from the East had driven the Byzantines out of much of Asia Minor and established the Persianized sultanate of the Seljuks." |

||

* [[Grousset, Rene]], ''The Empire of the Steppes'', (Rutgers University Press, 1991), 161, 164; "renewed the Seljuk attempt to found a great Turko-Persian empire in eastern Iran." "It is to be noted that the Seljuks, those Turkomans who became sultans of Persia, did not Turkify Persia-no doubt because they did not wish to do so. On the contrary, it was they who voluntarily became Persians and who, in the manner of the great old Sassanid kings, strove to protect the Iranian populations from the plundering of Ghuzz bands and save Iranian culture from the Turkoman menace." |

* [[Grousset, Rene]], ''The Empire of the Steppes'', (Rutgers University Press, 1991), 161, 164; "renewed the Seljuk attempt to found a great Turko-Persian empire in eastern Iran." "It is to be noted that the Seljuks, those Turkomans who became sultans of Persia, did not Turkify Persia-no doubt because they did not wish to do so. On the contrary, it was they who voluntarily became Persians and who, in the manner of the great old Sassanid kings, strove to protect the Iranian populations from the plundering of Ghuzz bands and save Iranian culture from the Turkoman menace." |

||

* Possessors and possessed: museums, archaeology, and the visualization of history in the late Ottoman Empire; By Wendy M. K. Shaw; Published by University of California Press, 2003, ISBN 0520233352, ISBN 9780520233355; p. 5.</ref> |

* Possessors and possessed: museums, archaeology, and the visualization of history in the late Ottoman Empire; By Wendy M. K. Shaw; Published by University of California Press, 2003, ISBN 0520233352, ISBN 9780520233355; p. 5.</ref> originating from the [[Qynyq]] branch of [[Oghuz Turks]].<ref> |

||

* {{cite journal |last=Jackson |first=P. |year=2002 |title=Review: The History of the Seljuq Turkmens: The History of the Seljuq Turkmens |journal=Journal of Islamic Studies |volume=13 |issue=1 |pages=75–76 |doi=10.1093/jis/13.1.75 |publisher=[[Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies]] }} |

* {{cite journal |last=Jackson |first=P. |year=2002 |title=Review: The History of the Seljuq Turkmens: The History of the Seljuq Turkmens |journal=Journal of Islamic Studies |volume=13 |issue=1 |pages=75–76 |doi=10.1093/jis/13.1.75 |publisher=[[Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies]] }} |

||

* Bosworth, C. E. (2001). Notes on Some Turkish Names in Abu 'l-Fadl Bayhaqi's Tarikh-i Mas'udi. Oriens, Vol. 36, 2001 (2001), pp. 299–313. |

* Bosworth, C. E. (2001). Notes on Some Turkish Names in Abu 'l-Fadl Bayhaqi's Tarikh-i Mas'udi. Oriens, Vol. 36, 2001 (2001), pp. 299–313. |

||

Revision as of 14:04, 23 December 2015

Seljuk Empire

| |

|---|---|

| 1037–1194 | |

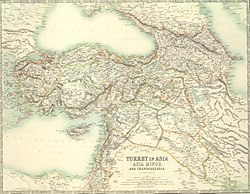

Great Seljuq Empire in its zenith in 1092, upon the death of Malik Shah I | |

| Status | Empire |

| Capital | Nishapur (1037–1043) Rey (1043–1051) Isfahan (1051–1118) Hamadan, Western capital (1118–1194) Merv, Eastern capital (1118–1153) |

| Common languages | |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Sultan | |

• 1037–1063 | Toghrul I (first) |

• 1174–1194 | Toghrul III (last)[5][6] |

| History | |

• Tughril formed the state system | 1037 |

• Replaced by the Khwarezmian Empire[7] | 1194 |

| Area | |

| 1080 est. | 3,900,000 km2 (1,500,000 sq mi) |

| Today part of | |

| History of the Turkic peoples pre–14th century |

|---|

|

|

| History of Greater Iran |

|---|

| History of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Seljuk Empire was a medieval Turkish empire[8] originating from the Qynyq branch of Oghuz Turks.[9] The Seljuq Empire controlled a vast area stretching from the Hindu Kush to eastern Anatolia and from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf. From their homelands near the Aral sea, the Seljuqs advanced first into Khorasan and then into mainland Persia before eventually conquering eastern Anatolia.

The Seljuq/Seljuk empire was founded by Tughril Beg (1016–63) in 1037. Tughril was raised by his grandfather, Seljuk-Beg, who was in a high position in the Oghuz Yabgu State. Seljuk gave his name to both the Seljuk empire and the Seljuk dynasty. The Seljuqs united the fractured political scene of the eastern Islamic world and played a key role in the first and second crusades. Highly Persianized[10] in culture[11] and language,[12] the Seljuqs also played an important role in the development of the Turko-Persian tradition,[13] even exporting Persian culture to Anatolia.[14][15] The settlement of Turkic tribes in the northwestern peripheral parts of the empire, for the strategic military purpose of fending off invasions from neighboring states, led to the progressive Turkicization of those areas.[16]

Founder of the Dynasty

The apical ancestor of the Seljuqs was their beg, Seljuq, who was reputed to have served in the Khazar army, under whom, circa 950, they migrated to Khwarezm, near the city of Jend, where they converted to Islam.[17]

Expansion of the Empire

The Seljuqs were allied with the Persian Samanid shahs against the Qarakhanids. The Samanid fell to the Qarakhanids in Transoxania (992–999), however, whereafter the Ghaznavids arose. The Seljuqs became involved in this power struggle in the region before establishing their own independent base.

Tughril and Chaghri

Tughril was the grandson of Seljuq and brother of Chaghri, under whom the Seljuks wrested an empire from the Ghaznavids. Initially the Seljuqs were repulsed by Mahmud and retired to Khwarezm, but Tughril and Chaghri led them to capture Merv and Nishapur (1037).[18] Later they repeatedly raided and traded territory with his successors across Khorasan and Balkh and even sacked Ghazni in 1037.[19] In 1040 at the Battle of Dandanaqan, they decisively defeated Mas'ud I of the Ghaznavids, forcing him to abandon most of his western territories to the Seljuqs. In 1055, Tughril captured Baghdad from the Shi'a Buyids under a commission from the Abbasids.

Alp Arslan

Alp Arslan, the son of Chaghri Beg, expanded significantly upon Tughril's holdings by adding Armenia and Georgia in 1064 and invading the Byzantine Empire in 1068, from which he annexed almost all of Anatolia. Arslan's decisive victory at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 effectively neutralized the Byzantine resistance to the Turkish invasion of Anatolia.[20] He authorized his Turkmen generals to carve their own principalities out of formerly Byzantine Anatolia, as atabegs loyal to him. Within two years the Turkmens had established control as far as the Aegean Sea under numerous beghliks (modern Turkish beyliks): the Saltukids in Northeastern Anatolia, Mengujekids in Eastern Anatolia, Artuqids in Southeastern Anatolia, Danishmendis in Central Anatolia, Rum Seljuqs (Beghlik of Suleyman, which later moved to Central Anatolia) in Western Anatolia, and the Beylik of Tzachas of Smyrna in İzmir (Smyrna).

Malik Shah I

Under Alp Arslan's successor, Malik Shah, and his two Persian viziers,[21] Nizām al-Mulk and Tāj al-Mulk, the Seljuq state expanded in various directions, to the former Iranian border of the days before the Arab invasion, so that it soon bordered China in the east and the Byzantines in the west. Malikshāh moved the capital from Rey to Isfahan. The Iqta military system and the Nizāmīyyah University at Baghdad were established by Nizām al-Mulk, and the reign of Malikshāh was reckoned the golden age of "Great Seljuq". The Abbasid Caliph titled him "The Sultan of the East and West" in 1087. The Assassins (Hashshashin) of Hassan-i Sabāh started to become a force during his era, however, and they assassinated many leading figures in his administration; according to many sources these victims included Nizām al-Mulk.

Governance

The Seljuq power was at its zenith under Malikshāh I, and both the Qarakhanids and Ghaznavids had to acknowledge the overlordship of the Seljuqs.[22] The Seljuq dominion was established over the ancient Sasanian domains, in Iran and Iraq, and included Anatolia as well as parts of Central Asia and modern Afghanistan.[22] The Seljuk rule was modelled after the tribal organization common in Turkic and Mongol nomads and resembled a 'family federation' or 'appanage state'.[22] Under this organization, the leading member of the paramount family assigned family members portions of his domains as autonomous appanages.[22]

Division of empire

When Malikshāh I died in 1092, the empire split as his brother and four sons quarrelled over the apportioning of the empire among themselves. Malikshāh I was succeeded in Anatolia by Kilij Arslan I, who founded the Sultanate of Rum, and in Syria by his brother Tutush I. In Persia he was succeeded by his son Mahmud I, whose reign was contested by his other three brothers Barkiyaruq in Iraq, Muhammad I in Baghdad, and Ahmad Sanjar in Khorasan. When Tutush I died, his sons Radwan and Duqaq inherited Aleppo and Damascus respectively and contested with each other as well, further dividing Syria amongst emirs antagonistic towards each other.

In 1118, the third son Ahmad Sanjar took over the empire. His nephew, the son of Muhammad I, did not recognize his claim to the throne, and Mahmud II proclaimed himself Sultan and established a capital in Baghdad, until 1131 when he was finally officially deposed by Ahmad Sanjar.

Elsewhere in nominal Seljuq territory were the Artuqids in northeastern Syria and northern Mesopotamia; they controlled Jerusalem until 1098. The Dānišmand dynasty founded a state in eastern Anatolia and northern Syria and contested land with the Sultanate of Rum, and Kerbogha exercised independence as the atabeg of Mosul.

First Crusade

During the First Crusade, the fractured states of the Seljuqs were generally more concerned with consolidating their own territories and gaining control of their neighbours than with cooperating against the crusaders. The Seljuqs easily defeated the untrained People's Crusade arriving in 1096, but they could not stop the progress of the army of the subsequent Princes' Crusade, which took important cities such as Nicaea (İznik), Iconium (Konya), Caesarea Mazaca (Kayseri), and Antioch (Antakya) on its march to Jerusalem (Al-Quds). In 1099 the crusaders finally captured the Holy Land and set up the first Crusader states. The Seljuqs had already lost Palestine to the Fatimids, who had recaptured it just before its capture by the crusaders.

Second Crusade

During this time conflict with the Crusader states was also intermittent, and after the First Crusade increasingly independent atabegs would frequently ally with the Crusader states against other atabegs as they vied with each other for territory. At Mosul, Zengi succeeded Kerbogha as atabeg and successfully began the process of consolidating the atabegs of Syria. In 1144 Zengi captured Edessa, as the County of Edessa had allied itself with the Artuqids against him. This event triggered the launch of the Second Crusade. Nur ad-Din, one of Zengi's sons who succeeded him as atabeg of Aleppo, created an alliance in the region to oppose the Second Crusade, which landed in 1147.

Decline

Ahmad Sanjar had to contend with the revolts of Qarakhanids in Transoxiana, Ghorids in Afghanistan and Qarluks in modern Kyrghyzstan, as well as the nomadic Kara-Khitais who invaded the East and captured the Eastern Qarakhanid state. The Kara-Khitais then defeated the Western Qarakhanids, a vassal of the Seljuqs at Khujand. The Qarakhanids turned to their overlord the Seljuqs for help, but at the Battle of Qatwan in 1141, Sanjar was decisively defeated. The Seljuq army suffered great losses and Sanjar barely escaped with his life. The prestige of the Seljuqs became greatly diminished, and they lost all his eastern provinces up to the Syr Darya, with the vassalage of Western Kara-Khanid taken by the Kara-Khitan.[23]

Conquest by Khwarezm and the Ayyubids

In 1153, the Ghuzz (Oghuz Turks) rebelled and captured Sanjar. He managed to escape after three years but died a year later. The atabegs, such as Zengids and Artuqids, were only nominally under the Seljuk Sultan, and generally controlled Syria independently. When Ahmed Sanjar died in 1156, it fractured the empire even further and rendered the atabegs effectively independent.

- Khorasani Seljuqs in Khorasan and Transoxiana. Capital: Merv

- Kermani Seljuqs

- Sultanate of Rum (or Seljuqs of Turkey). Capital: Iznik (Nicaea), later Konya (Iconium)

- Atabeghlik of the Salghurids in Iran

- Atabeghlik of Eldiguzids in Iraq and Azerbaijan. Capital Hamadan

- Atabeghlik of Bori in Syria. Capital: Damascus

- Atabeghlik of Zangi in Al Jazira (Northern Mesopotamia). Capital: Mosul

- Turcoman Beghliks: Danishmendis, Artuqids, Saltuqids and Mengujekids in Asia Minor

- Khwarezmshahs in Transoxiana, Khwarezm. Capital: Urganch

After the Second Crusade, Nur ad-Din's general Shirkuh, who had established himself in Egypt on Fatimid land, was succeeded by Saladin. In time, Saladin rebelled against Nur ad-Din, and, upon his death, Saladin married his widow and captured most of Syria and created the Ayyubid dynasty.

On other fronts, the Kingdom of Georgia began to become a regional power and extended its borders at the expense of Great Seljuk. The same was true during the revival of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia under Leo II of Armenia in Anatolia. The Abbassid caliph An-Nasir also began to reassert the authority of the caliph and allied himself with the Khwarezmshah Takash.

For a brief period, Togrul III was the Sultan of all Seljuq except for Anatolia. In 1194, however, Togrul was defeated by Takash, the Shah of Khwarezmid Empire, and the Seljuq Empire finally collapsed. Of the former Seljuq Empire, only the Sultanate of Rûm in Anatolia remained. As the dynasty declined in the middle of the thirteenth century, the Mongols invaded Anatolia in the 1260s and divided it into small emirates called the Anatolian beyliks. Eventually one of these, the Ottoman, would rise to power and conquer the rest.

Legacy

The Seljuqs were educated in the service of Muslim courts as slaves or mercenaries. The dynasty brought revival, energy, and reunion to the Islamic civilization hitherto dominated by Arabs and Persians.

The Seljuqs founded universities and were also patrons of art and literature. Their reign is characterized by Persian astronomers such as Omar Khayyám, and the Persian philosopher al-Ghazali. Under the Seljuqs, New Persian became the language for historical recording, while the center of Arabic language culture shifted from Baghdad to Cairo.[24]

List of sultans of the Great Seljuq Empire

| # | Laqab | Throne name | Reign | Marriages | Succession right |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din رکن الدنیا والدین, |

Toghrul-Beg | 1037-1063 | 1) Altun Jan Khatun (2) Aka Khatun (3) Fulana Khatun (daughter of Abu Kalijar) (4) Seyyidah Khatun (daughter of Al-Qa'im, Abbasid caliph) (5) Fulana Khatun (widow of Chaghri Beg) |

son of Mikail (grandson of Seljuq) |

| 2 | Diya ad-Dunya wa ad-Din Adud ad-Dawlah ضياء الدنيا و الدين عضد الدولة |

Alp Arslan | 1063–1072 | 1) Aka Khatun (widow of Toghrul I) (2) Safariyya Khatun (daughter of Yusuf Qadir Khan, Khagan of Kara-Khanid) (3) Fulana Khatun (daughter of Smbat Lorhi) (4) Fulana Khatun (daughter of Kurtchu bin Yunus bin Seljuk) (5) Saljan Khatun |

son of Chaghri |

| 3 | Muizz ad-Dunya wa ad-Din Jalal ad-Dawlah معز الدین جلال الدولہ |

Malik-Shah I | 1072–1092 | 1) Turkan Khatun (daughter of Ibrahim Tamghach Khan, Khagan of Western Kara-Khanid) (2) Zubeida Khatun (daughter of Yaquti ibn Chaghri) (3) Safariyya Khatun (daughter of Isa Khan, Sultan of Samarkand) (4) Fulana Khatun (daughter of Romanos IV Diogenes) (5) Fulana Khatun (daughter of Emir Argun) |

son of Alp Arslan |

| 4 | Nasir ad-Dunya wa ad-Din ناصر الدنیا والدین |

Mahmud I | 1092–1094 | son of Malik-Shah I | |

| 5 | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din رکن الدنیا والدین |

Barkiyaruq | 1094-1105 | son of Malik-Shah I | |

| 6 | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din Jalal ad-Dawlah رکن الدنیا والدین جلال الدولہ |

Malik-Shah II | 1105 | son of Barkiyaruq | |

| 7 | Ghiyath ad-Dunya wa ad-Din غیاث الدنیا والدین |

Tapar | 1105–1118 | 1) Nisandar Jihan Khatun (2) Gouhar Khatun (daughter of Isma'il bin Yaquti) (3) Fulana Khatun (daughter of Aksungur Beg) |

son of Malik-Shah I |

| 8 | Mughith ad-Dunya wa ad-Din Jalal ad-Dawlah مُغيث الدنيا و الدين جلال الدولة |

Mahmud II | 1118–1131 | 1) Mah-i Mulk Khatun (died 1130) (daughter of Sanjar) (2) Amir Siti Khatun (daughter of Sanjar) (3) Ata Khatun (daughter of Ali bin Faramarz) |

son of Muhammad I |

| 9 | Muizz ad-Dunya wa ad-Din Adud ad-Dawlah مُعز الدنيا و الدين جلال الدولة |

Sanjar | 1118–1153 | 1) Turkan Khatun (daughter of Muhammad Arslan Khan, Khagan of Western Kara-Khanid) (2) Rusudan Khatun (daughter of Demetrius I of Georgia) (3) Gouhar Khatun (daughter of Isma'il bin Yaquti, widow of Tapar) (4) Fulana Khatun (daughter of Arslan Khan, a Qara Khitai prisoner) |

son of Malik-Shah I |

| 10 | Ghiyath ad-Dunya wa ad-Din غیاث الدنیا والدین |

Dawud | 1131–1132 | Gouhar Khatun (daughter of Masud) |

son of Mahmud II |

| 11 | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din رکن الدنیا والدین |

Toghrul II | 1132–1135 | 1) Mumine Khatun (mother of Arslan-Shah) (2) Zubeida Khatun (daughter of Barkiyaruq) |

son of Muhammad I |

| 12 | Ghiyath ad-Dunya wa ad-Din غیاث الدنیا والدین |

Masud | 1135–1152 | 1) Gouhar Khatun (daughter of Sanjar) (2) Zubeida Khatun (daughter of Barkiyaruq, widow of Toghrul II) (3) Mustazhiriyya Khatun (daughter of Qawurd) (4) Sufra Khatun (daughter of Dubais) (5) Arab Khatun (daughter of Al-Muqtafi) (6) Ummiha Khatun (daughter of Amid ud-Deula bin Juhair) (7) Abkhaziyya Khatun (daughter of David IV of Georgia) (8) Sultan Khatun (mother of Malik-Shah III) |

son of Muhammad I |

| 13 | Muin ad-Dunya wa ad-Din مُعين الدنيا و الدين |

Malik-Shah III | 1152–1153 | son of Mahmud II | |

| 14 | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din رکن الدنیا والدین |

Muhammad | 1153–1159 | 1) Mahd Rafi Khatun (daughter of Kirman-Shah) (2) Gouhar Khatun (daughter of Masud, widow of Dawud) (3) Kerman Khatun (daughter of Al-Muqtafi) (4) Kirmaniyya Khatun (daughter of Tughrul Shah, ruler of Kerman) |

son of Mahmud II |

| 15 | Ghiyath ad-Dunya wa ad-Din غیاث الدنیا والدین |

Suleiman-Shah | 1159–1160 | 1) Khwarazmi Khatun (daughter of Muhammad Khwarazm Shah) (2) Abkhaziyya Khatun (daughter of David IV of Georgia, widow of Masud) |

son of Muhammad I |

| 16 | Muizz ad-Dunya wa ad-Din معز الدنیا والدین |

Arslan-Shah | 1160–1176 | 1) Kerman Khatun (daughter of Al-Muqtafi, widow of Muhammad) (2) Sitti Fatima Khatun (daughter of Ala ad-Daulah) (3) Kirmaniyya Khatun (daughter of Tughrul Shah, ruler of Kerman, widow of Muhammad) (4) Fulana Khatun (sister of Izz al-Din Hasan Qipchaq) |

son of Toghrul II |

| 17 | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din رکن الدنیا والدین |

Toghrul III | 1176–1191 1st reign |

Inanj Khatun (daughter of Sunqur-Inanj, ruler of Rey, widow of Toghrul III) |

son of Arslan-Shah |

| 18 | Muzaffar ad-Dunya wa ad-Din مظفر الدنیا والدین |

Qizil Arslan | 1191 | Inanj Khatun (daughter of Sunqur-Inanj, ruler of Rey, widow of Muhammad ibn Ildeniz) |

son of Ildeniz (stepbrother of Arslan-Shah) |

| — | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din رکن الدنیا والدین |

Toghrul III | 1192–1194 2nd reign |

son of Arslan-Shah |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

-

Seljuq-era art: Ewer from Herat, Afghanistan, dated 1180–1210CE. Brass worked in repousse and inlaid with silver and bitumen. British Museum.

-

Head of male royal figure, 12–13th century, found in Iran.

-

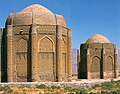

The Kharāghān twin towers, built in 1053 in Iran, is the burial of Seljuq princes.

See also

- Artuqid

- Assassins

- Atabeg

- Anatolian Seljuks family tree

- Danishmend

- Ghaznavid Empire

- Rahat al-sudur

- Seljuq

- Seljuq architecture

- Seljuq dynasty

- Sultanate of Rûm

- History of the Turks

- List of Turkic dynasties and countries

- Timeline of the Sultanate of Rûm

- Timeline of the Turks (500–1300)

- Seldschuken-Fürsten, list of Seljuq rulers in the German Wikipedia

- Turkic migrations

References

- ^ a b Savory, R. M., ed. (1976). Introduction to Islamic Civilisation. Cambridge University Press. p. 82. ISBN 0-521-20777-0.

- ^ Black, Edwin (2004). Banking on Baghdad: Inside Iraq's 7,000-year History of War, Profit and Conflict. John Wiley and Sons. p. 38. ISBN 0-471-67186-X.

- ^ a b c C.E. Bosworth, "Turkish Expansion towards the west" in UNESCO History of Humanity, Volume IV, titled "From the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century", UNESCO Publishing / Routledge, p. 391: "While the Arabic language retained its primacy in such spheres as law, theology and science, the culture of the Seljuk court and secular literature within the sultanate became largely Persianized; this is seen in the early adoption of Persian epic names by the Seljuk rulers (Qubād, Kay Khusraw and so on) and in the use of Persian as a literary language (Turkish must have been essentially a vehicle for everyday speech at this time)."

- ^ Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, Ed. Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie, (Elsevier Ltd., 2009), 1110; "Oghuz Turkic is first represented by Old Anatolian Turkish which was a subordinate written medium until the end of the Seljuk rule."

- ^ A New General Biographical Dictionary, Vol.2, Ed. Hugh James Rose, (London, 1853), 214.

- ^ Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1988), 167.

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1988). The Empire of the Steppes. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. pp. 159, 161. ISBN 0-8135-0627-1.

In 1194, Togrul III would succumb to the onslaught of the Khwarizmian Turks, who were destined at last to succeed the Seljuks to the empire of the Middle East.

- ^

- "Aḥmad of Niǧde's al-Walad al-Shafīq and the Seljuk Past", A. C. S. Peacock, Anatolian Studies, Vol. 54, (2004), 97; "With the growth of Seljuk power in Rum, a more highly developed Muslim cultural life, based on the Persianate culture of the Great Seljuk court, was able to take root in Anatolia."

- Meisami, Julie Scott, Persian Historiography to the End of the Twelfth Century, (Edinburgh University Press, 1999), 143; "Nizam al-Mulk also attempted to organise the Saljuq administration according to the Persianate Ghaznavid model..."

- Encyclopaedia Iranica, "Šahrbānu", Online Edition: "... here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkmen heroes or Muslim saints ..."

- Josef W. Meri, Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, 2005, p. 399

- Michael Mandelbaum, Central Asia and the World, Council on Foreign Relations (May 1994), p. 79

- Jonathan Dewald, Europe 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World, Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004, p. 24: "Turcoman armies coming from the East had driven the Byzantines out of much of Asia Minor and established the Persianized sultanate of the Seljuks."

- Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (Rutgers University Press, 1991), 161, 164; "renewed the Seljuk attempt to found a great Turko-Persian empire in eastern Iran." "It is to be noted that the Seljuks, those Turkomans who became sultans of Persia, did not Turkify Persia-no doubt because they did not wish to do so. On the contrary, it was they who voluntarily became Persians and who, in the manner of the great old Sassanid kings, strove to protect the Iranian populations from the plundering of Ghuzz bands and save Iranian culture from the Turkoman menace."

- Possessors and possessed: museums, archaeology, and the visualization of history in the late Ottoman Empire; By Wendy M. K. Shaw; Published by University of California Press, 2003, ISBN 0520233352, ISBN 9780520233355; p. 5.

- ^

- Jackson, P. (2002). "Review: The History of the Seljuq Turkmens: The History of the Seljuq Turkmens". Journal of Islamic Studies. 13 (1). Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies: 75–76. doi:10.1093/jis/13.1.75.

- Bosworth, C. E. (2001). Notes on Some Turkish Names in Abu 'l-Fadl Bayhaqi's Tarikh-i Mas'udi. Oriens, Vol. 36, 2001 (2001), pp. 299–313.

- Dani, A. H., Masson, V. M. (Eds), Asimova, M. S. (Eds), Litvinsky, B. A. (Eds), Boaworth, C. E. (Eds). (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (Pvt. Ltd).

- Hancock, I. (2006). ON ROMANI ORIGINS AND IDENTITY. The Romani Archives and Documentation Center. The University of Texas at Austin.

- Asimov, M. S., Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). (1998). History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. IV: The Age of Achievement: AD 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century, Part One: The Historical, Social and Economic Setting. Multiple History Series. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- Dani, A. H., Masson, V. M. (Eds), Asimova, M. S. (Eds), Litvinsky, B. A. (Eds), Boaworth, C. E. (Eds). (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (Pvt. Ltd).

- ^

- Encyclopaedia Iranica, "Šahrbānu", Online Edition: "... here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkmen heroes or Muslim saints ..."

- Josef W. Meri, "Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia", Routledge, 2005, p. 399

- Michael Mandelbaum, "Central Asia and the World", Council on Foreign Relations (May 1994), p. 79

- Jonathan Dewald, "Europe 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World", Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004, p. 24: "Turcoman armies coming from the East had driven the Byzantines out of much of Asia Minor and established the Persianized sultanate of the Seljuks."

- ^

- C.E. Bosworth, "Turkmen Expansion towards the west" in UNESCO History of Humanity, Volume IV, titled "From the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century", UNESCO Publishing / Routledge, p. 391: "While the Arabic language retained its primacy in such spheres as law, theology and science, the culture of the Seljuk court and secular literature within the sultanate became largely Persianized; this is seen in the early adoption of Persian epic names by the Seljuk rulers (Qubād, Kay Khusraw and so on) and in the use of Persian as a literary language (Turkmen must have been essentially a vehicle for everyday speech at this time). The process of Persianization accelerated in the thirteenth century with the presence in Konya of two of the most distinguished refugees fleeing before the Mongols, Bahā' al-Dīn Walad and his son Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, whose Mathnawī, composed in Konya, constitutes one of the crowning glories of classical Persian literature."

- Mehmed Fuad Köprülü, "Early Mystics in Turkish Literature", Translated by Gary Leiser and Robert Dankoff, Routledge, 2006, pg 149: "If we wish to sketch, in broad outline, the civilization created by the Seljuks of Anatolia, we must recognize that the local—i.e., non-Muslim, element was fairly insignificant compared to the Turkish and Arab-Persian elements, and that the Persian element was paramount. The Seljuk rulers, to be sure, who were in contact with not only Muslim Persian civilization, but also with the Arab civilizations in al-jazlra and Syria—indeed, with all Muslim peoples as far as India—also had connections with {various} Byzantine courts. Some of these rulers, like the great 'Ala' al-Dln Kai-Qubad I himself, who married Byzantine princesses and thus strengthened relations with their neighbors to the west, lived for many years in Byzantium and became very familiar with the customs and ceremonial at the Byzantine court. Still, this close contact with the ancient Greco-Roman and Christian traditions only resulted in their adoption of a policy of tolerance toward art, aesthetic life, painting, music, independent thought—in short, toward those things that were frowned upon by the narrow and piously ascetic views {of their subjects}. The contact of the common people with the Greeks and Armenians had basically the same result. {Before coming to Anatolia,} the Turkmens had been in contact with many nations and had long shown their ability to synthesize the artistic elements that thev had adopted from these nations. When they settled in Anatolia, they encountered peoples with whom they had not yet been in contact and immediately established relations with them as well. Ala al-Din Kai-Qubad I established ties with the Genoese and, especially, the Venetians at the ports of Sinop and Antalya, which belonged to him, and granted them commercial and legal concessions. Meanwhile, the Mongol invasion, which caused a great number of scholars and artisans to flee from Turkmenistan, Iran, and Khwarazm and settle within the Empire of the Seljuks of Anatolia, resulted in a reinforcing of Persian influence on the Anatolian Turks. Indeed, despite all claims to the contrary, there is no question that Persian influence was paramount among the Seljuks of Anatolia. This is clearly revealed by the fact that the sultans who ascended the throne after Ghiyath al-Din Kai-Khusraw I assumed titles taken from ancient Persian mythology, like Kai-Khusraw, Kai-Ka us, and Kai-Qubad; and that. Ala' al-Din Kai-Qubad I had some passages from the Shahname inscribed on the walls of Konya and Sivas. When we take into consideration domestic life in the Konya courts and the sincerity of the favor and attachment of the rulers to Persian poets and Persian literature, then this fact {i.e., the importance of Persian influence} is undeniable. With- regard to the private lives of the rulers, their amusements, and palace ceremonial, the most definite influence was also that of Iran, mixed with the early Turkish traditions, and not that of Byzantium."

- Stephen P. Blake, Shahjahanabad: The Sovereign City in Mughal India, 1639–1739. Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 123: "For the Seljuks and Il-Khanids in Iran it was the rulers rather than the conquered who were "Persianized and Islamicized"

- ^

- Encyclopaedia Iranica, "Šahrbānu", Online Edition: "... here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkmen heroes or Muslim saints ..."

- O.Özgündenli, "Persian Manuscripts in Ottoman and Modern Turkish Libraries", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, "Seljuq", Online Edition: "... Because the Turkish Seljuqs had no Islamic tradition or strong literary heritage of their own, they adopted the cultural language of their Persian instructors in Islam. Literary Persian thus spread to the whole of Iran, and the Arabic language disappeared in that country except in works of religious scholarship ..."

- M. Ravandi, "The Seljuq court at Konya and the Persianisation of Anatolian Cities", in Mesogeios (Mediterranean Studies), vol. 25-6 (2005), pp. 157–69

- F. Daftary, "Sectarian and National Movements in Iran, Khorasan, and Trasoxania during Umayyad and Early Abbasid Times", in History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol 4, pt. 1; edited by M.S. Asimov and C.E. Bosworth; UNESCO Publishing, Institute of Ismaili Studies: "... Not only did the inhabitants of Khurasan not succumb to the language of the nomadic invaders, but they imposed their own tongue on them. The region could even assimilate the Turkic Ghaznavids and Seljuks (eleventh and twelfth centuries), the Timurids (fourteenth–fifteenth centuries), and the Qajars (nineteenth–twentieth centuries) ..."

- ^ "The Turko-Persian tradition features Persian culture patronized by Turkic rulers." See Daniel Pipes: "The Event of Our Era: Former Soviet Muslim Republics Change the Middle East" in Michael Mandelbaum, "Central Asia and the World: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkemenistan and the World", Council on Foreign Relations, p. 79. Exact statement: "In Short, the Turko-Persian tradition featured Persian culture patronized by Turcophone rulers."

- ^ Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (Rutgers University Press, 1991), 574.

- ^ Bingham, Woodbridge, Hilary Conroy and Frank William Iklé, History of Asia, Vol.1, (Allyn and Bacon, 1964), 98.

- ^

- Professor Peter Golden has written one of the most comprehensive books on Turkic people, called An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples (Peter B. Golden. Otto Harrasowitz, 1992). pg 386:

- John Perry:

- According to C.E. Bosworth:

- According to Fridrik Thordarson:

- ^ Wink, Andre, Al Hind the Making of the Indo Islamic World, Brill Academic Publishers, Jan 1, 1996, ISBN 90-04-09249-8 pg.9

- ^ Andre Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, Vol.2, (Brill, 2002), 9. – via Questia (subscription required)

- ^ Iran, The Columbia World Dictionary of Islamism, ed. Antoine Sfeir and John King, transl. John King, (Columbia University Press, 2007), 141.

- ^ "Dhu'l Qa'da 463/ August 1071 The Battle of Malazkirt (Manzikert)". Retrieved 2007-09-08.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, "Nizam al-Mulk", Online Edition

- ^ a b c d Wink, Andre, Al Hind the Making of the Indo Islamic World, Brill Academic Publishers, Jan 1, 1996, ISBN 90-04-09249-8 pg 9–10

- ^ Biran, Michel, The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History, (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 44.

- ^ Andre Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, Vol.2, 16. – via Questia (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2002). "KAVURD BEY" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 25 (Kasti̇lya – Ki̇le) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-975-389-403-6.

- ^ Zahîrüddîn-i Nîsâbûrî, Selcûḳnâme, (Muhammed Ramazânî Publications), Tahran 1332, p. 10.

- ^ Reşîdüddin Fazlullāh-ı Hemedânî, Câmiʿu’t-tevârîḫ, (Ahmed Ateş Publications), Ankara 1960, vol. II/5, p. 5.

- ^ Râvendî, Muhammed b. Ali, Râhatü’s-sudûr, (Ateş Publications), vol. I, p. 85.

- ^ Müstevfî, Târîḫ-i Güzîde, (Nevâî Publications), p. 426.

- ^ a b c Osman Gazi Özgüdenli (2016). "MÛSÂ YABGU". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Supplement 2 (Kâfûr, Ebü'l-Misk – Züreyk, Kostantin) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 324–325. ISBN 978-975-389-889-8.

- ^ a b Sevim, Ali (1991). "ATSIZ b. UVAK" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 4 (Âşik Ömer – Bâlâ Külli̇yesi̇) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. p. 92-93. ISBN 978-975-389-431-9.

- ^ a b c Sümer, Faruk (2002). "KUTALMIŞ" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 26 (Ki̇li̇ – Kütahya) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 480–481. ISBN 978-975-389-406-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Sevim, Ali (1993). "ÇAĞRI BEY" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 8 (Ci̇lve – Dârünnedve) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 183–186. ISBN 978-975-389-435-7.

- ^ Beyhakī, Târîḫ, (Behmenyâr), p. 71.

- ^ Alptekin, Coşkun (1989). "AKSUNGUR" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 2 (Ahlâk – Amari̇) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. p. 196. ISBN 978-975-389-429-6.

- ^ a b c Sümer, Faruk (2009). "SELÇUKLULAR" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 36 (Sakal – Sevm) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 365–371. ISBN 978-975-389-566-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Sümer, Faruk (2009). "KİRMAN SELÇUKLULARI" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 36 (Sakal – Sevm) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. p. 377-379. ISBN 978-975-389-566-8.

- ^ Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2012). "TUTUŞ" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 41 (Tevekkül – Tüsterî) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 446–449. ISBN 978-975-389-713-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Sümer, Faruk (2009). "SELÇUKS of Syria" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 36 (Sakal – Sevm) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 385–386. ISBN 978-975-389-566-8.

- ^ a b c d Bezer, Gülay Öğün (2011). "TERKEN HATUN, the mother of MAHMÛD I" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 40 (Tanzi̇mat – Teveccüh) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. p. 510. ISBN 978-975-389-652-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2004). "MELİKŞAH" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 29 (Mekteb – Misir Mevlevîhânesi̇) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-975-389-415-9.

- ^ Sümer, Faruk (1991). "ARSLAN ARGUN" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 3 (Amasya – Âşik Mûsi̇ki̇si̇) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. p. 399-400. ISBN 978-975-389-430-2.

- ^ a b c Özaydın, Abdülkerim (1992). "BERKYARUK" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 5 (Balaban – Beşi̇r Ağa) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 514–516. ISBN 978-975-389-432-6.

- ^ Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2005). "MUHAMMED TAPAR" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 30 (Misra – Muhammedi̇yye) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 579–581. ISBN 978-975-389-402-9.

- ^ Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2009). "AHMED SENCER" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 36 (Sakal – Sevm) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 507–511. ISBN 978-975-389-566-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sümer, Faruk (2009). "Irak Selçuklulari" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 36 (Sakal – Sevm) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. p. 387. ISBN 978-975-389-566-8.

- ^ Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2003). "MAHMÛD b. MUHAMMED TAPAR" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 27 (Kütahya Mevlevîhânesi̇ – Mani̇sa) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 371–372. ISBN 978-975-389-408-1.

- ^ Sümer, Faruk (2012). "TUĞRUL I" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 41 (Tevekkül – Tüsterî) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 341–342. ISBN 978-975-389-713-6.

- ^ Sümer, Faruk (2004). "MES'ÛD b. MUHAMMED TAPAR" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 29 (Mekteb – Misir Mevlevîhânesi̇) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 349–351. ISBN 978-975-389-415-9.

- ^ Sümer, Faruk (1991). "ARSLANŞAH b. TUĞRUL" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 3 (Amasya – Âşik Mûsi̇ki̇si̇) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 404–406. ISBN 978-975-389-430-2.

- ^ Sümer, Faruk (2012). "Ebû Tâlib TUĞRUL b. ARSLANŞAH b. TUĞRUL" (PDF). TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 41 (Tevekkül – Tüsterî) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 342–344. ISBN 978-975-389-713-6.

Further reading

- Previté-Orton, C. W. (1971). The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tetley, G. E. (2008). The Ghaznavid and Seljuk Turks: Poetry as a Source for Iranian History. Abingdon. ISBN 9780415431194.