Prayagraj

Allahabad

प्रयाग The City of Prime Ministers | |

|---|---|

Metropolitan City | |

| |

| Country | |

| State | Uttar Pradesh |

| District | Allahabad |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Abhilasha Gupta |

| Area | |

| • Total | 63.07 km2 (24.35 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 98 m (322 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 5,959,798 |

| • Density | 94,000/km2 (240,000/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Hindi |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 211001-05 |

| Telephone code | 91-532 |

| Vehicle registration | UP-70 |

| Sex ratio | 901 ♂/♀ |

Allahabad (; Hindi: इलाहाबाद), is a major city in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh of India. It is the administrative headquarters of the Allahabad District. Allahabad is the seventh most populous city in Uttar Pradesh having an area of 63.07 km2 (24.35 sq mi), with an estimated population of 1.74 million living in the city and district area. Original name of city is Prayaga ("place of sacrifice"), representing the sacred union of the rivers Ganges, Yamuna and Saraswati. It is referred as second-oldest city in India. In 2011, Allahabad has been ranked the world's 130th fastest growing city.

Allahabad is located on in the south-eastern part of Uttar Pradesh. It is bounded by Pratapgarh in the north, Bhadohi in the east, Rewa in the south and Kaushambi in the west. Allahabad themselve consist of a large number of suburbs. While the city area is governed by several municipalities, a large portion of Allahabad District is governed by the Allahabad City Council. The demonym of Allahabad is Allahabadi.

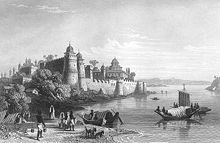

Allahabad was originally founded by Mughal emperor Akbar in 1526 as the administrative centre. The area became a part of the Mauryan and Gupta empires of the east and the Kushan empire of the west before becoming part of the Kannauj empire in 15th century. The city was the scene of Maratha incursions before colonial rule was imposed over India. In 1765, the British established a garrison at [Allahabad fort]]. It is also known as the "Prime minister Capital of the India," the importance of the government to the city has led seven out of fourteen Prime Ministers of India.

As a large and growing city, Allahabad is home to many well-recognized colleges and research institutions in India. Many government offices of both central and state government are lies in the city. Allahabad city plays a central role in the Hindu scriptures. City has a large number of temples and palaces. Furthermore, Allahabad has hosted many large cultural and sporting events, one of them is Kumbh Mela. Although Allahabad's economy was built on the tourism industry, the model of business drives its economy, with the effect that its main revenues are now from real estate, and financial services, similar to that of Western countries.

History

The city was known earlier as Prayāga - a name that is still commonly used.[2] That it is an ancient town, is illustrated by supposed references in the Vedas to Prayag, where Brahma, the Hindu Creator of the Universe, is believed to have attended a sacrificial ritual.[3] Excavations have revealed Northern Black Polished ware objects in Prayag, further corroborating the conjecture that Prayag existed as a town as early as 600 B.C.[3] The Puranas record that Yayati left Prayag and conquered the region of Saptha Sindhu.[4] His five sons Yadu, Druhyu, Puru, Anu and Turvashu became the main tribes of the Rigveda.[5] Lord Rama, the main protagonist in the Ramayana, spent time, at the Ashram of Sage Bharadwaj, before proceeding to nearby Chitrakoot.[6]

When the Aryans first settled in what they termed the Āryāvarta, or Madhyadesha, Prayag or Kaushambi was an important part of their territory.[7] The Vatsa were rulers of Hastinapur (near present day Delhi), and they established the town of Kaushambi near Prayag.[8] They shifted their capital to Kaushambi when [Hastinapur]] was destroyed by floods. The Doaba region, including Prayag was controlled by several empires and dynasties in the ages to come. When the Muslim rule came, Prayag became a part of the Delhi sultanate when the town was annexed by Mohammad Ghori in A.D. 1193.[9] Later, the Mughals took over from the slave rulers of Delhi and under them Prayag rose to prominence.[10] Akbar built a magnificent fort viz. Allahabad fort, on the banks of the holy sangam and rechristened the town as Illahabad in 1575.[10] In 1765, the combined forces of the Nawab of Awadh and the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II lost the battle of Buxar to the British.[11] Although, the British did not take over their states, they established a garrison at the Prayag fort - realising its strategic position as the gateway to the north west.[12] In 1801, the Nawab of Awadh ceded the city to the British East India Company.[13] Gradually the other parts of Doaba and adjoining region in its west (including Delhi and Ajmer-Mewara regions) were won by the British.[11] When these north western areas were made into a new Presidency called the "North Western Provinces of Agra", its capital was Agra. Allahabad remained an important part of this state.[14] In 1834, Allahabad became the seat of the Government of the Agra Province and a High Court was established, but a year later both were relocated to Agra. In 1857,Allahabad was active in the Indian Mutiny. After the mutiny, the British truncated the Delhi region of the state, merging it with Punjab and transferred the capital of North west Provinces to Allahabad, which remained so for the next 20 years. Later, In 1877 the two provinces of Agra (NWPA) and Awadh were merged to form a new state which was called the United Provinces.[14] Allahabad served as the capital of United Provinces until 1920.[15]

During the Mutiny of 1857, Allahabad had a significant presence of European troops.[16] Maulvi Liaquat Ali freedom fighter of 1857, unfurled the banner of revolt.[17] After the Mutiny was quelled, the Brotish established the High Court, the Police Headquarters and the Public Service Commission in the city.[18] This transformed Allahabad into an administrative center. The fourth session of the Indian National Congress was held in the city in 1888.[19] At the turn of the century, Allahabad also became a nodal point for the revolutionaries.[20] The Karmyogi office of Sundar Lal in Chowk sparked patriotism among youth. Nityanand Chatterji became a household name when he hurled the first bomb at the European club.[21] It was at Alfred Park in Allahabad where, in 1931, the revolutionary Chandrashekhar Azad killed himself when surrounded by the British Police. The Nehru family homes Anand Bhavan and Swaraj Bhavan were at the center of the political activities of the Indian National Congress. In the years of the freedom struggle, thousands of satyagrahis, led, inter alia, by Purushottam Das Tandon, Bishambhar Nath Pande and Narayan Dutt Tiwari. The first seeds of the idea of Pakistan were sown in Allahabad. On 29 December 1930, Allama Muhammad Iqbal's presidential address to the All-India Muslim League proposed a separate Muslim state for the Muslim majority regions of India.[22][23]

Geography

Topography

Allahabad is located in the southern part of the state, at 25°27′N 81°50′E / 25.45°N 81.84°E and stands at the confluence of the Ganga and Yamuna rivers.[24][25] The region was known in antiquity as the vats country. To its south west is the Bundelkhand region, to its east and south east is the Baghelkhand region, to its north and north east is the Awadh region and to its west is the (lower) doab of which it itself is a part.[24] The city is divided by the railway line running through it. South of the railway line as Old Chowk area, while the British built Civil lines is situated in north. Allahabad stands at a strategic point both geographically and culturally. A part of the Ganga-Yamuna Doaba region, it is the last point of the Yamuna river. As with most of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, the soil and water are predominantly alluvial in origin. The Indian GMT longitude that is associated with Jabalpur, also passes through Allahabad. According to a United Nations Development Programme report, its wind and cyclone zone is "Low damage risk".[26] according to a United Nations Development Programme report, its wind and cyclone zone is "Low damage risk".[26]

Climate

Allahabad is subject to a humid subtropical climate common to cities in the plains of North India, that is designated Aw under the Köppen climate classification. The annual mean temperature is 26.1 °C (79.0 °F); monthly mean temperatures are 18–29 °C (64–84 °F).[27] Summers (March–June) are hot, with temperatures in the low 30s Celsius; during dry spells, maximum temperatures often exceed 40 °C (104 °F) in May and June.[27] Winter lasts for only about two-and-a-half months, with seasonal lows dipping to 9–11 °C (48–52 °F) in December and January. May is the hottest month, with daily temperatures ranging from 27–37 °C (81–99 °F); January, the coldest month, has temperatures varying from 9–18 °C (48–64 °F). The highest recorded temperature is 48.9 °C (120.0 °F), and the lowest is 2 °C (36 °F).[27][28]

Rains brought either by the Bay of Bengal branch of the south-west summer monsoon or by the Arabian Sea from the Arabian Sea branch[29] lash Allahabad between June and September, supplying it with most of its annual rainfall of 1,027 mm (40 in). The highest monthly rainfall total, 296 mm (12 in), occurs in August. The month with the wettest weather is August when on balance 333 mm (13 in) of rain, sleet, hail or snow falls across 21 days; while driest weather is April when on balance 5 mm (0 in) of rain, sleet, hail or snow falls across 1 days. The city receives 2961 hours of sunshine per year, with maximum sunlight exposure occurring in May.[28]

| Climate data for Allahabad | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 23.6 (74.5) |

27.2 (81.0) |

33.6 (92.5) |

39.4 (102.9) |

42.3 (108.1) |

40.1 (104.2) |

34.1 (93.4) |

32.7 (90.9) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.1 (91.6) |

29.7 (85.5) |

24.8 (76.6) |

32.8 (91.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.7 (76.5) |

20.5 (68.9) |

13.8 (56.8) |

9.3 (48.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 19.2 (0.76) |

15.6 (0.61) |

9.2 (0.36) |

5.7 (0.22) |

9.9 (0.39) |

85.4 (3.36) |

300.1 (11.81) |

307.6 (12.11) |

189.8 (7.47) |

40.1 (1.58) |

11.7 (0.46) |

3.4 (0.13) |

1,017.7 (40.07) |

| Source: IMD | |||||||||||||

Biodiversity

Allahabad's comes under the larger Gangetic Plain region in its north; it includes the Ganges-Yamuna Doab and the Terai which is responsible for the city's unique species of flora and fauna.[30][31] Since human arrival almost half of the country's vertebrate species have become extinct. Others are endangered or have had their range severely reduced. "Allahabad Museum", which is one of the four national museums in the country, has undertaken an exercise to document the existing flora and fauna in the Ganga and Yamuna river belt.[32] The arrival of humans, associated changes to habitat, and the introduction of reptiles, snakes and other mammals led to the extinction of many bird species, including large birds like eagle.[30] large numbers of Siberian birds reported in sangam and nearby wetlands during winter season.[33]

The most common birds which are found in the state are doves, peacocks, junglefowl, black partridge, house sparrows, songbirds, blue jays, parakeets, quails, bulbuls, and comb ducks.[34] Other animals in the state include reptiles such as lizards, cobras, kraits, and gharials.[30]

Demographics

The 2011 census reported 5,959,798 residents in the Allahabad Statistical Division of which male and female were 3,133,479 and 2,826,319 respectively.[36] The initial provisional data suggest a density of 1,087 in 2011 compared to 901 of 2001.[36] Total area under Allahabad is of about 5,481/km2 (14,200/sq mi). Allahabad's literacy rate of 74.41% exceeds the all-India average of 74%.[37] Native people form the majority of Allahabad's population; Bengalis and Biharis compose large minorities. According to the 2001 census, 85.15% of the population is Hindu, 13.77% Muslim, 0.36% Christian, and 0.20% Sikh. The remainder of the population includes Sikhs, Buddhists, and other religions; 0.48% did not state a religion in the census.[1]

According to 2011 census of India reports, Allahabad has recorded the highest literacy rate exceeds the all-India average of 74%.[38] Average literacy rate of Allahabad is 74.41% out of which male literacy rate is 85.00%, while Female literacy rate is 62.67%.[39]

Hindi, the official state language, is the dominant language in Allahabad. English is also used, particularly by the white-collar workforce. Urdu is spoken by a sizable minority.[1] The dialect of Hindi spoken in Allahabad is Awadhi, although Khariboli is most commonly used in the city area. In the eastern non-Doabi part of Allahabad district Bagheli dialect is more common. Bengali and Punjabi are also spoken in some quarters. The 2008 National Crime Records Bureau statistics indicate that Allahabad accounts for 3.5% of the total crimes reported from 35 major cities in India.[40]

Civic administration

Allahabad is administered by several government agencies. The Allahabad Nagar Nigam (ANN) also called Allahabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) oversees and manages the civic infrastructure of the city. The corporation came into existence in 1864, when Lucknow Municipal Act was passed by Government of India.[41] City municipal area is divided in total 80 wards and a member (the Corporator) from each ward is elected to form the Municipal Committee. The Corporators elect the Mayor of city.[41] The chief executive is the Commissioner of Allahabad who is appointed by the state government.Allahabad's rapid growth has created several problems relating to traffic congestion and infrastructural obsolescence that the Allahabad Nagar Nigam has found challenging to address. The unplanned nature of growth in the city resulted in massive traffic gridlocks that the municipality attempted to ease by constructing a flyover system and by imposing one-way traffic systems.[41]

As of 2012, the Samajwadi Party controls the AMC. The city has an apolitical titular ruler post, which presides over various city-related functions and conferences.[42] As the seat of the Government of Uttar Pradesh is home to not only the offices of the local governing agencies, but also the Uttar Pradesh Legislative Assembly; the state secretariat, which is housed in the Allahabad High Court.[42] The Allahabad Police, headed by a police commissioner, is overseen by the Uttar PRadesh Ministry of Home Affairs. The Allahabad district elects two representatives to India's lower house, the Lok Sabha, and 9 representatives to the state legislative assembly.[43]

Administrative divisions

Allahabad has been divided into several blocks under Tehsils. As of 2011, there are 20 blocks under 8 tehsil in the Allahabad city. [44][45][46] The 8 tehsils of Allahabad are as listed below.

Transportation

Allahabad is served by the Allahabad Airport (IATA: IXD, ICAO: VIAL) which started operations from February 1966. The airport is around 12 km from the city centre.[47] The most hassle-free way to commute is by taxi. Meru cabs and Easy cabs have taxis present in the rank at the airport. There are also certain private cab companies. Varanasi, Lucknow and Kanpur are the nearest operational airports found around Allahabad.[48]

Allahabad Junction is one of the main railway junctions of the northern India. It is the headquarters of the North Central Railway Zone.[49] The four prominent railway stations of Allahabad are - Prayag Station, City Station at Rambagh, Daraganj Station and Allahabad Station.[50] It is efficiently connected to most cities in Uttar Praesh as well as all major cities of India such as Kolkata, New Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, Lucknow and Jaipur.[51]

Three-wheeled, yellow and black auto-rickshaws, referred to as autos, are a popular form of transport.[52] They are metered and can accommodate up to three passengers. Taxis, commonly called City Taxis, are usually available only on call. Taxis are metered and are generally more expensive than auto-rickshaws. Tempos are the cheapest mode of travelling in Allahabad.[52]

Buses operated by Uttar Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation (UPSRTC) are an important means of public transport available in the city, and are highly reliable.[53] Besides these, National Highway 2 runs through the middle of the city. India’s biggest cable-stayed bridge called "Allahabad-Naini Bridge", erected in the years 2001 - 2004, is located in Uttar Prahdesh State and connects the cities of Allahabad and Naini next to the banks of the Yamuna River. The old Naini steel-truss-bridge which has to accommodate railway- and car-traffic.[54] A number of road bridges on rivers Ganges and Yamuna have been built to connect Allahabad with its suburburan towns like Naini and Jhusi.[55]

Education

Allahabad's schools are run by the state government or private organisations, many of which are religious. English is the medium of instructions in most private schools while government aided schools and colleges offer both Hindi and English medium education.[56] Urdu is also used. Schools in Allahabad follow the 10+2+3 plan.[57] After completing their secondary education, students typically enroll in schools that have a higher secondary facility and are affiliated with the Uttar Pradesh Board of High School and Intermediate Education, the ICSE, or the CBSE.[56] They usually choose a focus on liberal arts, business, or science. Vocational programs are also available.[58]

Allahabad attracts students and learners from all over country. As of 2010, Allahabad has one central university, three deemed universities, an open university.[59] The colleges are each affiliated with a university or institution based either in Allahabad or elsewhere in India. Allahabad University, founded in 1876, is the oldest modern university in whole state.[59] Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology is is one of the twenty National Institutes of Technology and an Institute of National Importance of India.[60] Allahabad Agricultural Institute is the oldest modern university in South Asia.[61] Nationally renowned professional institutes such as the Motilal Nehru Medical College (MNMI), Uttar Pradesh Rajarshi Tandon Open University (UPRTOU), Harish-Chandra Research Institute (HRI), Govind Ballabh Pant Social Science Institute (GSSI), Institute of Engineering and Rural Technology (IERT), Ewing Christian College, United College of Engineering & Research, Sam Higginbottom Institute of Agriculture, Technology and Sciences and Birla Institute of Technology are located in Allahabad.[62] These research and technical institutions are known for providing higher education in vast range of disciplines.[61]

Industries

The main industries of Allahabad consist of tourism, fishing and agriculture. Allahabad city is largest commercial centers in the state and also the second largest highest per capita income city with third highest GDP rate in state followed by Kanpur.[63] It is also the most prominent industrial towns, with 58 large industrial unit, and more than 3,000 small scale industries.[64] The Third All India Census for Small Scale Industries shows[citation needed] that there are more than 10,000 unregistered small scale industry units in the city.[65][66]

Allahabad has glass, wire based industries. The main industrial area of Allahabad is Naini and Phulpur, where several public and private sector companies have their units, offices and factories.[67] Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited India’s largest oil marketing company, the state-owned petroleum firm is setting up a seven million tonnes per annum (MTPA) capacity refinery with an estimated investment of 62 billion at Lohgara.[63] Allahabad Bank which began operations in 1865, headquartered in the city.[66] The growth of IT has presented the city with unique challenges. Ideological clashes sometimes occur between the city's IT moguls, who demand an improvement in the city's infrastructure, and the state government, whose electoral base is primarily the people in city. Allahabad is also considered as a hub for agricultural related industry in India.[68]

Media

Among Allahabad's widely circulated Hindi-language newspapers are Amar Ujala, Dainik Bhaskar, Nai Dunia, Hindustan Dainik, Aj, Rajasthan Patrika and Dainik Jagran.[69] English-language newspapers published and sold in Allahabad include The Times of India, Hindustan Times, The Hindu, The Indian Express, and the Asian Age. Prominent financial dailies like The Economic Times, Financial Express, Business Line and Business Standard are widely circulated. Vernacular newspapers, such as those in the Urdu, Gujarati and Punjabi lanuages, are read by minorities. All India Radio, the national state-owned radio broadcaster, airs several AM radio stations in the city. Allahabad has 5 local radio stations broadcasting on FM, including two from AIR.[70] Other regional channels are accessible via cable subscription, direct-broadcast satellite services, or internet-based television.

References

- ^ a b c "Provisional Population Totals, Census of India 2011; Urban Agglomerations/Cities having population 1 lakh and above" (PDF). Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. p. 3. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ Pollux Variste Kjeld (2 August 2011). History of Allahabad. International Book Marketing Service Limited. p. 120. ISBN 978-613-5-87853-0. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ a b Shiva Kumar Dubey (2001). Kumbh city Prayag. Centre for Cultural Resources and Training. pp. 31–41. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Koenraad Elst (2002). Who is a Hindu?: Hindu revivalist views of Animism, Buddhism, Sikhism, and other offshoots of Hinduism. Voice of India. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-85990-74-3. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Romila Thapar (1 January 1978). Ancient Indian Social History: Some Interpretations. Orient Blackswan. pp. 298–320. ISBN 978-81-250-0808-8. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ K. Krishnamoorthy (1 January 1991). A Critical Inventory of Rāmāyaṇa Studies in the World: Indian languages and English. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 28–51. ISBN 978-81-7201-100-0. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Vincent Arthur Smith; Stephen Meredyth Edwardes (1928). The Oxford history of India, from the earliest times to the end of 1911. The Clarendon press. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ K-M. Sarup & Sons. p. 247. ISBN 978-81-7625-365-9. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Surinder Kaur; Tapan Kumar Sanyal (1991). The Secular Emperor Babar: A victim of Indian partition. Lokgeet Parkashan. p. 78. ISBN 978-81-85220-07-9. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ a b Stephen Meredyth Edwardes; Herbert Leonard Offley Garrett (1930). Mughal Rule In India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 279–281. ISBN 978-81-7156-551-1. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ a b B. R. Andhare (1984). Bundelkhand under the Marathas, 1720-1818 A.D.: a study of Maratha-Bundela relations. Vol. 1–2. Vishwa Bharati Prakashan. p. 93. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Edward Thompson; Edward T. & G.T. Garratt (1 January 1999). History of British Rule in India. Vol. 2. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 453. ISBN 978-81-7156-804-8. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Harriet Martineau (1857). British rule in India: a historical sketch. Smith, Elder and co. p. 128. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ a b A. L. Basham (30 November 2008). The Wonder That Was India: A Survey of the Culture of the Indian Sub-Continent Before the Coming of the Muslims. ACLS History E-Book Project. p. 699. ISBN 978-1-59740-599-7. Retrieved 3 August 2012. Cite error: The named reference "Basham2008" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Kerry Ward (1 December 2008). Networks of Empire: Forced Migration in the Dutch East India Company. Cambridge University Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-521-88586-7. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Edward John Thompson; Geoffrey Theodore Garratt (1962). Rise and fulfilment of British rule in India. Central Book Depot. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Sugata Bose (18 December 2003). Modern South Asia: History, Culture and Political Economy. Taylor & Francis. pp. 74–77. ISBN 978-0-415-30787-1. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Bhai Nahar Singh; Bhai Kirpal Singh (1 January 1995). Rebels Against the British Rule. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 290. ISBN 978-81-7156-164-3. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Surendra Bhana; Ananda M. Pandiri; E. S. (FRW) Reddy (28 February 2007). A Comprehensive, Annotated Bibliography on Mahatma Gandhi: Books And Pamphlets About Mahatma Gandhi. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 12–18. ISBN 978-0-313-30217-6. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Indian National Congress. All India Congress Committee (1947). The Allahabad conference of the presidents and secretaries of provincial Congress committees. Allahabad. p. 57. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "Besides, locals still pride". Zee News. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Rafiq Zakaria (2004). The Man Who Divided India. Popular Prakashan. pp. 152–158. ISBN 978-81-7991-145-7. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. pp. 4–6. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Location of city". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "Allahabad Location Guide". Weather-forecast. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ a b "Hazard profiles of Indian districts" (PDF). National Capacity Building Project in Disaster Management. UNDP. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2006.

- ^ a b c

"Weatherbase entry for Allahabad". Canty and Associates LLC.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help); Unknown parameter|http://www.weatherbase.com/weather/weather.php3?s=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Allahabad climate". climate Maps India. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Khichar, M. L.; Niwas, R. (14 July 2003). "Know your monsoon". The Tribune. Chandigarh, India. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- ^ a b c Satish Chandra Kala; Allahabad Municipal Museum (2000). Flora and fauna in art: particularly in terracottas. Allahabad Museum. p. 86. Retrieved 4 August 2012. Cite error: The named reference "KalaMuseum2000" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Bal Krishna Misra; Birendra Kumar Verma (1992). Flora of Allahabad District, Uttar Pradesh, India. Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh. p. 530. ISBN 978-81-211-0077-9. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ "Allahabad museum to document flora, fauna of Ganga-Yamuna belt". The Indian Express. 4 August 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help) - ^ Aarti, Aggarwal (2 November 2009). "Siberian birds flock Sangam, other wetlands". The Times of India. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help) - ^ S.k.agarwal. Environment Biotechnology. APH Publishing. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-81-313-0294-1. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ "Census of India – Socio-cultural aspects". Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b "Allahabad : Census 2011". 2011 census of India. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "Population census 2011". Census of India 2011, Government of India. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ "Allahabad has highest literacy rate in region". The Times of India. 15 April 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help) - ^ "Average literacy rate of Allahabad". Census of India. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Snaphhots – 2008" (PDF). National Crime Records Bureau. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ a b c "Nagar Nigam - From the casement of history". Allahabad Nagar Nigam. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "'Urban Reforms Agenda' under JNNURM" (PDF). Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ "Bicameral legislature of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh". Uttar Pradesh Legislative Assembly. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ "Development Blocks under Tehsils". District court of Allahabad. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ Hridai Ram Yadav (2009). Village Development Planning. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 9–13. ISBN 978-81-7268-187-6. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ Pramod Lata Jain (1990). Co-operative Credit in Rural India: A Study of Its Utilisation. Mittal Publications. pp. 61–63. ISBN 978-81-7099-204-2. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ Allahabad Agricultural Institute (1937). The Allahabad aviation. Vol. 11. Allahabad Agricultural Institute. p. 44. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "Profile of UP State Unit". National Informatics Centre. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "North Central Railways present network". North Central Railways. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Railways (India): return to an order from any correspondence ... 1853. pp. 30–44. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ The Railway magazine. Vol. 124. IPC Business Press. 1978. p. 178. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Allahabad Travel". Kumbh Mela. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ "Important Service". UPSRTC. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "India's biggest cable-stayed bridge" (PDF). MAURER Swivel Joist. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ University of Allahabad. Agricultural Institute (1958). The Allahabad transportation. Vol. 32. p. 68. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Allahabad University". Allahabad University. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ "University of Allahabad". Allahabad University. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ "Center of Computer Education and Training". Allahabad University. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ a b "University history". Allahabad University. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ S.L. Goel Aruna Goel (1 January 2009). Educational Administration And Management:An Integrated Approach. Deep & Deep Publications. p. 94. ISBN 978-81-8450-143-8. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Directorate of Distance Education". Allahabad Agricultural Institute. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ Ameeta Gupta; Ashish Kumar; Ashish Kumar (Chartered Accountant.) (1 January 2006). Handbook of Universities. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 377–379. ISBN 978-81-269-0607-9. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ a b "GDP & per capita income of Allahabad". The Times of India. 8 March 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help) - ^ "Industrial units in allahabad" (PDF). U.P Pollution Control Board. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ India. Office of the Development Commissioner (Small Scale Industries); India. Office of the Development Commissioner, Small-Scale Industries (2004). Final results, third all India census of small scale industries, 2001-2002. Development Commissioner, Ministry of Small Scale Industries, Govt. of India. pp. 13–18. ISBN 978-81-88905-17-1. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Summary results of third census". All India Census of Small scale Industries. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ Office of the Development Commissioner, Small-Scale Industries, India (1993). Report on the second all-India census of small scale industrial units. Development Commissioner, Small Scale Industries, Ministry of Industry, Govt. of India. p. 72. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Agricultural industries in Allahabad". Grotal. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ "Hindi Newspapers in city". India Grid. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ "Radio stations in city". Asiawaves. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

External links

- Official website of Allahabad

- Template:Wikitravel

- North Western Provinces

- Allahabad at Wikimapia - Showing places, geography, terrain, routes in and around Allahabad using satellite images

- Use dmy dates from July 2012

- Use dmy dates from October 2010

- Allahabad

- Cities and towns in Allahabad district

- Hindu holy cities

- Yamuna River

- Places of Indian Rebellion of 1857

- Allahabad railway division

- Divisions of Indian Railways

- North Central Railway Zone

- Tourism in Uttar Pradesh

- Former Indian capital cities

- Railway junction stations in India