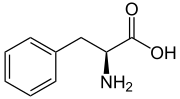

Phenylalanine

L-Phenylalanine

| |

L-Phenylalanine

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Phenylalanine

| |

| Other names

2-Amino-3-phenylpropanoic acid

| |

| Identifiers | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.517 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

| C9H11NO2 | |

| Molar mass | 165.192 g·mol−1 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 1.83 (carboxyl), 9.13 (amino)[1] |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Phenylalanine (data page) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

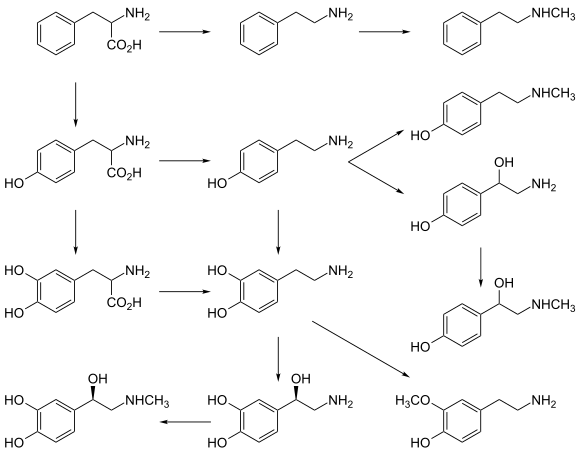

Phenylalanine /ˌfɛn[invalid input: 'ᵊ']lˈæləˌniːn/ (abbreviated as Phe or F)[2] is an α-amino acid with the formula C6H5CH2CH(NH2)COOH. This essential amino acid is classified as nonpolar because of the hydrophobic nature of the benzyl side chain. L-Phenylalanine (LPA) is an electrically neutral amino acid used to biochemically form proteins, coded for by DNA. The codons for L-phenylalanine are UUU and UUC. Phenylalanine is a precursor for tyrosine, the monoamine signaling molecules dopamine, norepinephrine (noradrenaline), and epinephrine (adrenaline), and the skin pigment melanin.

Phenylalanine is found naturally in the breast milk of mammals. It is used in the manufacture of food and drink products and sold as a nutritional supplement for its reputed analgesic and antidepressant effects. It is a direct precursor to the neuromodulator phenethylamine, a commonly used dietary supplement.

History

The first description of phenylalanine was made in 1879, when Schulze and Barbieri identified a compound with the empirical formula, C9H11NO2, in yellow lupine (Lupinus luteus) seedlings. In 1882, Erlenmeyer and Lipp first synthesized phenylalanine from phenylacetaldehyde, hydrogen cyanide, and ammonia.[3][4]

The genetic codon for phenylalanine was first discovered by J. Heinrich Matthaei and Marshall W. Nirenberg in 1961. They showed that by using m-RNA to insert multiple uracil repeats into the genome of the bacterium E. coli, they could cause the bacterium to produce a polypeptide consisting solely of repeated phenylalanine amino acids. This discovery helped to establish the nature of the coding relationship that links information stored in genomic nucleic acid with protein expression in the living cell.

=Dietary Sources

Phenylalanine is found in a large array of foods, herbs and some condiments. By in large the foods containing the highest amounts of phenylalanine in general are meat products such such as beef, ham, poultry, fish and other carnivorous. There are some other sources outside of meat, such as spinach and leafy greens, tofu, amaranth leaves and lupin seeds. All contain significant amounts of the amino acid and are also supplemented in some condiments like salad dressing and fast foods.

Other biological roles

L-Phenylalanine is biologically converted into L-tyrosine, another one of the DNA-encoded amino acids. L-tyrosine in turn is converted into L-DOPA, which is further converted into dopamine, norepinephrine (noradrenaline), and epinephrine (adrenaline). The latter three are known as the catecholamines.

Phenylalanine uses the same active transport channel as tryptophan to cross the blood–brain barrier. In excessive quantities, supplementation can interfere with the production of serotonin and other aromatic amino acids as well as nitric oxide due to the overuse (eventually, limited availability) of the associated cofactors, iron or tetrahydrobiopterin. The corresponding enzymes in for those compounds are the aromatic amino acid hydroxylase family and nitric oxide synthase.

In plants

Phenylalanine is the starting compound used in the flavonoid biosynthesis. Lignan is derived from phenylalanine and from tyrosine. Phenylalanine is converted to cinnamic acid by the enzyme phenylalanine ammonia-lyase.[8]

Phenylketonuria

The genetic disorder phenylketonuria (PKU) is the inability to metabolize phenylalanine. Individuals with this disorder are known as "phenylketonurics" and must regulate their intake of phenylalanine. A (rare) "variant form" of phenylketonuria called hyperphenylalaninemia is caused by the inability to synthesize a cofactor called tetrahydrobiopterin, which can be supplemented. Pregnant women with hyperphenylalaninemia may show similar symptoms of the disorder (high levels of phenylalanine in blood) but these indicators will usually disappear at the end of gestation. Individuals who cannot metabolize phenylalanine must monitor their intake of protein to control the buildup of phenylalanine as their bodies convert protein into its component amino acids.

Phenylketonurics often use blood tests to monitor the amount of phenylalanine in their blood. Lab results may report phenylalanine levels in different units, including mg/dL and μmol/L. One mg/dL of phenylalanine is approximately equivalent to 60 μmol/L.

A non-food source of phenylalanine is the artificial sweetener aspartame. This compound, sold under the trade names Equal and NutraSweet, is metabolized by the body into several chemical byproducts including phenylalanine. The breakdown problems phenylketonurics have with protein and the attendant buildup of phenylalanine in the body also occurs with the ingestion of aspartame, although to a lesser degree. Accordingly, all products in Australia, the U.S. and Canada that contain aspartame must be labeled: "Phenylketonurics: Contains phenylalanine." In the UK, foods containing aspartame must carry ingredient panels that refer to the presence of "aspartame or E951"[9] and they must be labeled with a warning "Contains a source of phenylalanine." In Brazil, the label "Contém Fenilalanina" (Portuguese for "Contains Phenylalanine") is also mandatory in products which contain it. These warnings are placed to aid individuals who have been diagnosed with PKU so that they can avoid such foods.

Geneticists have recently sequenced the genome of macaques. Their investigations have found "some instances where the normal form of the macaque protein looks like the diseased human protein" including markers for PKU.[10]

D-, L- and DL-phenylalanine

The stereoisomer D-phenylalanine (DPA) can be produced by conventional organic synthesis, either as a single enantiomer or as a component of the racemic mixture. It does not participate in protein biosynthesis although it is found in proteins in small amounts - particularly aged proteins and food proteins that have been processed. The biological functions of D-amino acids remain unclear, although D-phenylalanine has pharmacological activity at niacin receptor 2.[11]

DL-Phenylalanine (DLPA) is marketed as a nutritional supplement for its supposed analgesic and antidepressant activities. DL-Phenylalanine is a mixture of D-phenylalanine and L-phenylalanine. The reputed analgesic activity of DL-phenylalanine may be explained by the possible blockage by D-phenylalanine of enkephalin degradation by the enzyme carboxypeptidase A.[12] The mechanism of DL-phenylalanine's supposed antidepressant activity may be accounted for by the precursor role of L-phenylalanine in the synthesis of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and dopamine. Elevated brain levels of norepinephrine and dopamine are thought to have an antidepressant effect. D-Phenylalanine is absorbed from the small intestine and transported to the liver via the portal circulation. A small amount of D-phenylalanine appears to be converted to L-phenylalanine. D-Phenylalanine is distributed to the various tissues of the body via the systemic circulation. It appears to cross the blood–brain barrier less efficiently than L-phenylalanine, and so a small amount of an ingested dose of D-phenylalanine is excreted in the urine without penetrating the central nervous system.[citation needed]

L-Phenylalanine is an antagonist at α2δ Ca2+ calcium channels with a Ki of 980 nM.[13] At higher doses, this may play a role in its analgesic and antidepressant properties.

In the brain, L-phenylalanine is a competitive antagonist at the glycine binding site of NMDA receptor[14] and at the glutamate binding site of AMPA receptor.[15] At the glycine binding site of NMDA receptor L-phenylalanine has an apparent equilibrium dissociation constant (KB) of 573 µM estimated by Schild regression[16] which is considerably lower than brain L-phenylalanine concentration observed in untreated human phenylketonuria.[17] L-Phenylalanine also inhibits neurotransmitter release at glutamatergic synapses in hippocampus and cortex with IC50 of 980 µM, a brain concentration seen in classical phenylketonuria, whereas D-phenylalanine has a significantly smaller effect.[15]

Commercial synthesis

L-Phenylalanine is produced for medical, feed, and nutritional applications, such as aspartame, in large quantities by utilizing the bacterium Escherichia coli, which naturally produces aromatic amino acids like phenylalanine. The quantity of L-phenylalanine produced commercially has been increased by genetically engineering E. coli, such as by altering the regulatory promoters or amplifying the number of genes controlling enzymes responsible for the synthesis of the amino acid.[18]

See also

References

- ^ Dawson, R. M. C.; et al. (1959). Data for Biochemical Research. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ IUPAC-IUBMB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (1983). "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". Recommendations on Organic & Biochemical Nomenclature, Symbols & Terminology etc. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ^ Thorpe, T. E. (1913). A Dictionary of Applied Chemistry. Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. 191–193. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- ^ Plimmer, R. H. A. (1912) [1908]. Plimmer, R. H. A.; Hopkins, F. G. (ed.). The Chemical Composition of the Proteins. Monographs on Biochemistry. Vol. Part I. Analysis (2nd ed.). London: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 93–97. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- ^ Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- ^ Wang X, Li J, Dong G, Yue J (February 2014). "The endogenous substrates of brain CYP2D". European Journal of Pharmacology. 724: 211–218. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.025. PMID 24374199.

- ^ Nelson, D. L.; Cox, M. M. (2000). Lehninger, Principles of Biochemistry (3rd ed.). New York: Worth Publishing. ISBN 1-57259-153-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Aspartame". UK: Food Standards Agency.

- ^ Gibbs, R. A.; et al. (2007). "Evolutionary and Biomedical Insights from the Rhesus Macaque Genome" (pdf). Science. 316 (5822): 222–234. doi:10.1126/science.1139247. PMID 17431167.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "D-phenylalanine". IUPHAR. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ Christianson, D. W.; Mangani, S.; Shoham, G.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1989). "Binding of D-Phenylalanine and D-Tyrosine to Carboxypeptidase A" (pdf). Journal of Biological Chemistry. 264 (22): 12849–12853. PMID 2568989.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mortell KH, Anderson DJ, Lynch JJ; et al. (March 2006). "Structure-activity relationships of alpha-amino acid ligands for the alpha2delta subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 16 (5): 1138–41. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.11.108. PMID 16380257.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Glushakov, AV; Dennis, DM; Morey, TE; Sumners, C; Cucchiara, RF; Seubert, CN; Martynyuk, AE (2002). "Specific inhibition of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor function in rat hippocampal neurons by L-phenylalanine at concentrations observed during phenylketonuria". Molecular psychiatry. 7 (4): 359–67. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000976. PMID 11986979.

- ^ a b Glushakov, AV; Dennis, DM; Sumners, C; Seubert, CN; Martynyuk, AE (Apr 1, 2003). "L-phenylalanine selectively depresses currents at glutamatergic excitatory synapses". Journal of neuroscience research. 72 (1): 116–24. doi:10.1002/jnr.10569. PMID 12645085.

- ^ Glushakov, AV (February 2005). "Long-term changes in glutamatergic synaptic transmission in phenylketonuria". Brain : a journal of neurology. 128 (Pt 2): 300–7. doi:10.1093/brain/awh354. PMID 15634735.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Möller, HE; Weglage, J; Bick, U; Wiedermann, D; Feldmann, R; Ullrich, K (December 2003). "Brain imaging and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in patients with phenylketonuria". Pediatrics. 112 (6 Pt 2): 1580–3. PMID 14654669.

- ^ Sprenger, G. A. (2007). "Aromatic Amino Acids". Amino Acid Biosynthesis: Pathways, Regulation and Metabolic Engineering (1st ed.). Springer. pp. 106–113. ISBN 978-3-540-48595-7.Template:Inconsistent citations