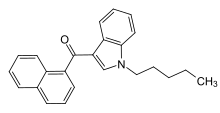

JWH-018

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Smoked, Oral |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.163.574 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C24H23NO |

| Molar mass | 341.454 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Solubility in water | hydrophobic, n/a mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

| | |

JWH-018 (1-pentyl-3-(1-naphthoyl)indole) or AM-678[1] is an analgesic chemical from the naphthoylindole family that acts as a full agonist at both the CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors, with some selectivity for CB2. It produces effects in animals similar to those of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a cannabinoid naturally present in cannabis, leading to its use in synthetic cannabis products that in some countries are sold legally as "incense blends".[2][3][4][5][6]

As a full agonist at both the CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors, this chemical compound is classified as an analgesic medication.[7]

The analgesic effects of cannabinoid ligands, mediated by CB1 receptors are well established in treatment of neuropathic pain, as well as cancer pain and arthritis.[7]

These compounds work by mimicking the body's naturally-produced endocannabinoid hormones such as 2-AG and anandamide (AEA), which are biologically active and can exacerbate or inhibit nerve signaling.[7]

As the cause is poorly understood in chronic pain states, more research and development must be done before we can realize the therapeutic potential of this class of biologic compounds.[7]

History

John W. Huffman, an organic chemist at Clemson University, synthesized a variety of chemical compounds that affect the endocannabinoid system. JWH-018 is one of these compounds, with studies showing an affinity for the cannabinoid (CB1) receptor five times greater than that of THC. Cannabinoid receptors are found in mammalian brain and spleen tissue; however, the structural details of the active sites are currently unknown.[8]

On December 15, 2008, it was reported by German pharmaceutical companies that JWH-018 was found as one of the active components in at least three versions of the grey market drug Spice, which has been sold as an incense in a number of countries around the world since 2002.[9][10][11] An analysis of samples acquired four weeks after the German prohibition of JWH-018 took place found that the manufacturers had shortened the alkyl chain by one carbon to circumvent the ban.[12]

Pharmacology

JWH-018 is a full agonist of both the CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors, with a reported binding affinity of 9.00 ± 5.00 nM at CB1 and 2.94 ± 2.65 nM at CB2.[3] JWH-018 has an EC50 of 102 nM for human CB1 receptors, and 133 nM for human CB2 receptors.[13] JWH-018 produces bradycardia and hypothermia in rats at doses of 0.3–3 mg/kg, suggesting potent cannabinoid-like activity.[13]

Pharmacokinetics

Metabolism of JWH-018 was assessed using Wistar rats which had been administered an ethanolic extract containing JWH-018. Urine was collected for 24 hours, followed by extraction of JWH-018 metabolites using both liquid-liquid extraction and solid-phase extraction. GC-MS was utilized to separate and identify the extracted compounds. JWH-018 and its N-dealkylated metabolite were only detected in small amounts, with hydroxylated N-dealkylated metabolites comprising the primary signal. The observed mass shift indicates that it is likely that hydroxylation occurs in both the naphthalene and indole portions of the molecule.[14] Human metabolites were similar although most metabolism took place on the indole ring and pentyl side chain, and the hydroxylated metabolites were extensively conjugated with glucuronide.[15]

Usage

At least one case of JWH-018 dependence has been reported by the media.[2] The user consumed JWH-018 daily for eight months. Withdrawal symptoms were more severe than those experienced as a result of cannabis dependence. JWH-018 has been shown to cause profound changes in CB1 receptor density following administration, causing desensitization to its effects more rapidly than related cannabinoids.[6]

On October 15, 2011, Anderson County coroner Greg Shore attributed the death of a South Carolina college basketball player to "drug toxicity and organ failure" caused by JWH-018.[16] An email dated Nov 4, 2011 concerning the case was finally released by the city of Anderson S.C. on Dec 16, 2011 under the Freedom of Information Act after multiple requests by media to see the information had been denied.[17]

Compared to THC, which is a partial agonist at CB1 receptors, JWH-018, and many synthetic cannabinoids, are full agonists. THC has been shown to inhibit GABA receptor neurotransmission in the brain via several pathways.[18][19] JWH-018 may cause intense anxiety, agitation, and, in rare cases (generally with non-regular JWH users), has been assumed to have been the cause of seizures and convulsions by inhibiting GABA neurotransmission more effectively than THC. Cannabinoid receptor full agonists may present serious dangers to the user when used to excess.[20]

Various physical and psychological adverse effects have been reported from JWH-018 use. One study reported psychotic relapses and anxiety symptoms in well-treated patients with mental illness following JWH-018 inhalation.[21] Due to concerns about the potential of JWH-018 and other synthetic cannabinoids to cause psychosis in vulnerable individuals, it has been recommended that people with risk factors for psychotic illnesses (like a past or family history of psychosis) not use these substances.[22]

Detection in biological fluids

JWH-018 usage is readily detected in urine using "spice" screening immunoassays from several manufacturers focused on both the parent drug and its omega-hydroxy and carboxyl metabolites.[23] JWH-018 will not be detected by older methods employed for detecting THC and other cannabis terpenoids. Determination of the parent drug in serum or its metabolites in urine has been accomplished by GC-MS or LC-MS. Serum JWH-018 concentrations are generally in the 1–10 μg/L range during the first few hours after recreational usage. The major urinary metabolite is a compound that is monohydroxylated on the omega minus one carbon atom of the alkyl side chain. A lesser metabolite monohydroxylated on the omega (terminal) position was present in the urine of 6 users of the drug at concentrations of 6–50 μg/L, primarily as a glucuronide conjugate.[24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32]

Legal status

| Country | Date of ban | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 18 December 2008 | The Austrian Ministry of Health announced on 18 December 2008 that Spice would be controlled under Paragraph 78 of their drug law on the grounds that it contains an active substance that affects the functions of the body, and the legality of JWH-018 is under review. | |

| 9 September 2011 | JWH-018 is considered a Schedule 9 prohibited substance in Australia under the Poisons Standard (October 2015).[33] A Schedule 9 substance is a substance which may be abused or misused, the manufacture, possession, sale or use of which should be prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval of Commonwealth and/or State or Territory Health Authorities.[33] | |

| 1 January 2010 | ||

| 21 February 2012 | JWH-018 is claimed to be a controlled substance in Canada though it is not listed under schedule 2 synthetic cannabinoids. Health Canada is of the opinion that "similar synthetic preparations" covers jwh-018 though jwh-018 is not similar in chemical structure nor in its action of the CB1 receptor. The issue is currently in debate between the courts and Canada's largest distributor. Note: the most current CDSA can be found here[34] | |

| 1 January 2012 | China has made JWH-018 Illegal for sale. It is illegal to import or export JWH-018. [citation needed] | |

| 24 July 2009 | ||

| 12 March 2012 | [35] | |

| 24 February 2009 | [36][37] | |

| 22 January 2009 | [38] | |

| 11 May 2010 | An immediate ban was announced on 11 May 2010 by Minister for Health Mary Harney.[39] | |

| 2 July 2010 | [40] | |

| 3 August 2012 | [41][42] | |

| 2 September 2014 | The Anti-narcotics department declared synthetic cannabinoids and their analogues illegal after an outbreak of JWH-018 containing product referred to as "Joker" .[43] | |

| 28 November 2009 | [44] | |

| 8 May 2014 | [45] | |

| 21 December 2011 | [46] | |

| [36] | ||

| 15 February 2010 | ||

| 22 January 2010 | ||

| 1 July 2009 | [47] | |

| 30 July 2009 | A bill to ban JWH-018 was accepted on 30 July 2009 and was in effect on 15 September 2009.[48] | |

| 13 February 2011 | Turkish authorities were first informed about JWH-018 through the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). The seizure of 2C-B in blue pill form on 13 October 2010 and the seizure of 0.6 g JWH-018 on 16 April 2010 in Eskisehir was reported through the Early Warning System (EWS). Upon these reports the EWS committee initiated the regulation process by warning the Ministry of Health.[49] In response to the official letter #86106 issued by the Ministry of Health dated 22 December 2010, the Council of Ministers decided on 7 January 2011 to add 14 cannabinoids; namely JWH-018, CP 47,497, JWH-073, HU-210, JWH-200, JWH-250, JWH-398, JWH-081, JWH-073, JWH-015, JWH-122, JWH-203, JWH-210, JWH-019;phenethylamines 2C-B and 2C-P as well as Catha edulis to the list of substances subject to the Law on Control of Narcotic Drugs. The regulation is in effect since 13 February 2011.[50] Upon letter #12099 issued by the Ministry of Health dated 6 February 2012, 4 more cannabinoids (AM-2201, RCS-4, JWH-201 and JWH-302), Salvia divinorum and several other chemicals (complete list here [51]) were added to the list of controlled substances on 17 February 2012 which is effective since 22 March 2012.[52] | |

| 31 May 2010 | ||

| 23 December 2009 | [53] | |

| 1 March 2011 | JWH-018 was temporarily scheduled on 1 March 2011 by 76 FR 11075. It was permanently scheduled on 9 July 2012 by Section 1152 of the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA)[54] |

Synthesis

See also

References

- ^ "Department of Justice :: Drug Enforcement Administration". 2011-03-01. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- ^ a b Zimmermann US, Winkelmann PR, Pilhatsch M, Nees JA, Spanagel R, Schulz K (2009). "Withdrawal Phenomena and Dependence Syndrome After the Consumption of "Spice Gold"". Dtsch Arztebl Int. 106 (27): 464–467. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0464. PMC 2719097. PMID 19652769.

- ^ a b Aung MM, Griffin G, Huffman JW, Wu M, Keel C, Yang B, Showalter VM, Abood ME, Martin BR (2000). "Influence of the N-1 alkyl chain length of cannabimimetic indoles upon CB1 and CB2 receptor binding" (PDF). Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 60 (2): 133–140. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00152-0. PMID 10940540. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-06.

- ^ US patent 6900236, Alexandros Makriyannis, Hongfeng Deng, "Cannabimimetic indole derivatives", issued 2005-05-31

- ^ US patent 7241799, Alexandros Makriyannis, Hongfeng Deng, "Cannabimimetic indole derivatives", issued 2007-07-10

- ^ a b Atwood, B.K.; et al. (2010). "JWH018, a common constituent of 'Spice' herbal blends, is a potent and efficacious cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist". British Journal of Pharmacology. 160 (3): 585–593. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00582.x. PMC 2931559. PMID 20100276. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

- ^ a b c d Rani Sagar D, Burston JJ, Woodhams SG, Chapman V (December 2012). "Dynamic changes to the endocannabinoid system in models of chronic pain". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 367 (1607): 3300–11. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0390. PMC 3481532. PMID 23108548.

- ^ "Clemson University :: Department of Chemistry". Clemson.edu. Archived from the original on August 22, 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ^ Gefährlicher Kick mit Spice Archived 2010-03-16 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- ^ Erstmals Bestandteile der Modedroge "Spice" nachgewiesen Archived 2008-12-18 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- ^ Spice enthält chemischen Wirkstoff (in German)

- ^ Lindigkeit R, Boehme A, Eiserloh I, Luebbecke M, Wiggermann M, Ernst L, Beuerle T (30 October 2009). "Spice: A never ending story?". Forensic Science International. 191 (1): 58–63. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.06.008. PMID 19589652.

- ^ a b Banister SD, Stuart J, Kevin RC, Edington A, Longworth M, Wilkinson SM, et al. (August 2015). "Effects of bioisosteric fluorine in synthetic cannabinoid designer drugs JWH-018, AM-2201, UR-144, XLR-11, PB-22, 5F-PB-22, APICA, and STS-135". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 6 (8): 1445–58. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00107. PMID 25921407.

- ^ Kraemer, T (2008). "Studies on the metabolism of JWH-18, the pharmacologically active ingredient of different misused incenses" (PDF). Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ Sobolevsky T, Prasolov I, Rodchenkov G (July 2010). "Detection of JWH-018 metabolites in smoking mixture post-administration urine". Forensic Science International. 200 (1–3): 141–7. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.04.003. PMID 20430547.

- ^ wyff4.com, Coroner: Synthetic Pot Killed College Athlete, posted 10/14/11, accessed 12/22/11, http://www.wyff4.com/news/29497549/detail.html Archived 2011-10-17 at the Wayback Machine,

- ^ Mayo, Nikie, "City Releases Email in Lamar Jacks Case", independentmail.com, posted Dec 16, 2011, accessed 12/22/11, http://www.independentmail.com/news/2011/dec/16/city-releases-email-lamar-jack-case/

- ^ Laaris N, Good CH, Lupica CR (July–August 2010). "Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol is a full agonist at CB1 receptors on GABA neuron axon terminals in the hippocampus". Neuropharmacology. 59 (1–2): 121–127. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.04.013. PMC 2882293. PMID 20417220.

- ^ Hoffman AF, Lupica CR (2000-04-01). "Mechanisms of cannabinoid inhibition of GABAA synaptic transmission in the hippocampus". The Journal of Neuroscience. 20 (7): 2470–2479. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-07-02470.2000. ISSN 0270-6474. PMID 10729327.

- ^ European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. "Understanding the Spice Phenomenon." 2009. ISBN 978-92-9168-411-3.[1]

- ^ Every-Palmer, S (2011). "Synthetic cannabinoid use and psychosis: an explorative study". Journal of Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 117 (2–3): 152–157. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.012. PMID 21316162.

- ^ Every-Palmer S (2010). "WARNING: LEGAL SYNTHETIC CANNABINOID-RECEPTOR AGONISTS SUCH AS JWH-018 MAY PRECIPITATE PSYCHOSIS IN VULNERABLE INDIVIDUALS". Addiction. 105 (10): 1859–1860. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03119.x. PMID 20840203.

- ^ See Arntson et al. (2013) http://jat.oxfordjournals.org/content/37/5/284.abstract, https://www.caymanchem.com/app/template/Product.vm/catalog/580210; http://www.randoxtoxicology.com/Products/Elisa-p-50, http://tulipbiolabs.com/our-product-areas/synthetic-cannabinoids and others.

- ^ Möller I, et al. Screening for the synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and its major metabolites in human doping controls. Drug Test. Anal. Sep 24, 2010. [Epub ahead of print]

- ^ Teske J, et al. Sensitive and rapid quantification of the cannabinoid receptor agonist naphthalen-1-yl-(1-pentylindol-3-yl)methanone (JWH-018) in human serum by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chrom. B 878: 2659-2663, 2010.

- ^ Auwärter V, Dresen S, Weinmann W, Müller M, Pütz M, Ferreirós N (2009). "'Spice' and other herbal blends: harmless incense or cannabinoid designer drugs?". Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 44 (5): 832–837. doi:10.1002/jms.1558. PMID 19189348. Free version

- ^ Zimmermann US, Winkelmann PR, Pilhatsch M, Nees JA, Spanagel R, Schulz K (2009). "Withdrawal phenomena and dependence syndrome after the consumption of "spice gold"". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 106 (27): 464–467. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0464. PMC 2719097. PMID 19652769.

- ^ Sobolevsky T, Prasolov I, Rodchenkov G (2010). "Detection of JWH-018 metabolites in smoking mixture post-administration urine". Forensic Science International. 200 (1–3): 141–147. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.04.003. PMID 20430547.

- ^ Beuck S, Möller I, Thomas A, Klose A, Schlörer N, Schänzer W, Thevis M (August 2011). "Structure characterisation of urinary metabolites of the cannabimimetic JWH-018 using chemically synthesised reference material for the support of LC-MS/MS-based drug testing". Anal Bioanal Chem. 401 (2): 493–505. doi:10.1007/s00216-011-4931-5. PMID 21455647.

- ^ Moran CL, Le VH, Chimalakonda KC, Smedley AL, Lackey FD, Owen SN, Kennedy PD, Endres GW, Ciske FL, Kramer JB, Kornilov AM, Bratton LD, Dobrowolski PJ, Wessinger WD, Fantegrossi WE, Prather PL, James LP, Radominska-Pandya A, Moran JH (June 2011). "Quantitative measurement of JWH-018 and JWH-073 metabolites excreted in human urine". Anal. Chem. 83 (11): 4228–36. doi:10.1021/ac2005636. PMC 3105467. PMID 21506519.

- ^ Logan BK, et al. Identification of primary JWH-018 and JWH-073 metabolites in human urine. NMS Labs Technical Bulletin, May 25, 2011. http://toxwiki.wikispaces.com/file/view/JWH_metabolites_Technical_Bulletin_Final_v1.1.pdf

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 10th edition, Biomedical Publications, Seal Beach, CA, 2014, p. 1863.

- ^ a b Poisons Standard October 2015 https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2015L01534

- ^ "Controlled Drugs and Substances Act". Laws.justice.gc.ca. 2010-08-16. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ^ *** Tiedote/Valtioneuvoston viestintäyksikkö: VALTIONEUVOSTON YLEISISTUNTO 1.3.2012 *** Archived 2015-11-18 at the Wayback Machine (in Finnish)

- ^ a b "EMCDDA | Drug profile: Synthetic cannabinoids and 'Spice'". Emcdda.europa.eu. 2010-08-17. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ BGBl I Nr. 3 vom 21.01.2009, 22. BtMÄndV vom 19. Januar 2009, S. 49–50.

- ^ Many head shop products banned - Irish Times.

- ^ http://www.politicheantidroga.it/comunicazione/comunicati/2010/luglio/spice,-n-joy-e-mefedrone-da-oggi-stupefacenti.aspx Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Italian)

- ^ 麻薬の新規指定について (in Japanese). MHLW. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- ^ "Japan to Ban New Synthetic Drugs". StoptheDragWar.org. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- ^ <http://www.antinarcotics.psd.gov.jo>

- ^ "Latvian list of prohibited drugs". Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "What they are". Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ http://www.lovdata.no/ltavd1/filer/sf-20111221-1465.html

- ^ 최연희 (2 July 2009). "1일부터 '5-메오-밉트' 등 향정신성의약품 지정". 헬스코리아뉴스. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ "Archived copy" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 2010-09-10. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Illicit Drug Report of Turkey 2010" (PDF) (in Turkish). Department of Anti-smuggling and Organised Crime. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-16. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Decision of the Council of Ministers, Enactment 2011/1310" (in Turkish). General Directorate of Legislation Development and Publication. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Attachment to Enactment 2012/2861" (PDF) (in Turkish). General Directorate of Legislation Development and Publication. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ "Decision of the Council of Ministers, Enactment 2012/2861" (in Turkish). General Directorate of Legislation Development and Publication. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ Ford, Richard (2009-12-23). "Three legal highs banned after deaths linked to the drugs". The Times. London. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Temporary Placement of Four Synthetic Cannabinoids Into Schedule I". DEA Office of Diversion Control. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ Appendino G, Minassi A, Taglialatela-Scafati O (2014). "Recreational drug discovery: natural products as lead structures for the synthesis of smart drugs". Natural Product Reports. 31 (7): 880–904. doi:10.1039/c4np00010b. PMID 24823967.