Same-sex marriage

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ topics |

|---|

|

|

| Part of the LGBT rights series |

|

|

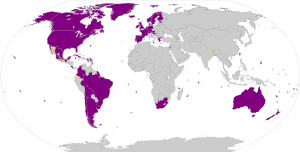

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is marriage between people of the same sex, either as a secular civil ceremony or in a religious setting. The term marriage equality refers to a political status in which same-sex marriage and opposite-sex marriage are considered legally equal.

In the late 20th century, rites of marriage for same-sex couples without legal recognition became increasingly common. The first law providing for marriage of people of the same sex in modern times was enacted in 2001 in the Netherlands. As of 9 December 2017[update], same-sex marriage is legally recognized (nationwide or in some parts) in the following countries: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico,[nb 1] the Netherlands,[nb 2] New Zealand,[nb 3] Norway, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom,[nb 4] the United States[nb 5] and Uruguay. It is also likely to soon become legal in Taiwan and Austria, after court rulings on the subject in May and December 2017 respectively.[1][2] Polls show rising support for legally recognizing same-sex marriage in the Americas and most of Europe.[3][4][5] However, as of 2017, South Africa is the only African country where same-sex marriage is recognized. Taiwan would become the first country in Asia to legalize same-sex marriage if the Civil Code is amended. Two other Asian countries, namely Israel and Armenia recognise same-sex marriages performed outside the country for some purposes.[6][7] Since 2015, the United States is the most populous country to have legalized same-sex marriage.

Introduction of same-sex marriage laws has varied by jurisdiction, being variously accomplished through legislative change to marriage laws, a court ruling based on constitutional guarantees of equality, or by direct popular vote (via ballot initiative or referendum). The recognition of same-sex marriage is a political and social issue, and also a religious issue in many countries, and debates continue to arise over whether people in same-sex relationships should be allowed marriage or some similar status (a civil union).[8][9][10]

Same-sex marriage can provide those in same-sex relationships who pay their taxes with government services and make financial demands on them comparable to those afforded to and required of those in opposite-sex marriages. Same-sex marriage also gives them legal protections such as inheritance and hospital visitation rights.[11] Various faith communities around the world support allowing those of the same sex to marry, while many major religions oppose same-sex marriage. Opponents of same-sex marriages have argued that recognition of same-sex marriages would erode religious freedoms,[12] undermine a right of children to be raised by their biological mother and father[13] or erode the institution of marriage itself.[14]

Some analysts state that financial, psychological and physical well-being are enhanced by marriage, and that children of same-sex parents or carers benefit from being raised by two parents within a legally recognized union supported by society's institutions.[15][16][17][18][19][20] A court document filed by an American scientific association stated that reversing enacted SSM legislation served to single out gay men and women as ineligible for marriage, thereby both stigmatizing and inviting public discrimination against them.[21]

The American Anthropological Association asserts that social science research does not support the view that either civilization or viable social orders depend upon marriage as an exclusively heterosexual institution.[22]

Terminology

Alternative terms

Some proponents of legal recognition of same-sex marriage, such as Freedom to Marry and Canadians for Equal Marriage, use the terms marriage equality and equal marriage to indicate that they seek equal benefit of marriage laws as opposed to special rights.[23][24][25][26][27][28][29]

Opponents of the legalization of same-sex marriage sometimes characterize it as redefining marriage or redefined marriage, especially in the United States.[30][31] The term homosexual marriage is generally used by organisations opposed to same-sex marriage such as the Family Research Council in the United States;[32] that term is rarely used in the mainstream press.[33]

Associated Press style recommends the usages marriage for gays and lesbians or in space-limited headlines gay marriage with no hyphen and no scare quotes. The Associated Press warns that the construct gay marriage can imply that marriages of same-sex couples are somehow legally different from those of mixed-sex couples.[34][35]

Use of the term marriage

Anthropologists have struggled to determine a definition of marriage that absorbs commonalities of the social construct across cultures around the world.[36][37] Many proposed definitions have been criticized for failing to recognize the existence of same-sex marriage in some cultures, including in more than 30 African cultures, such as the Kikuyu and Nuer.[37][38][39]

With several countries revising their marriage laws to recognize same-sex couples in the 21st century, all major English dictionaries have revised their definition of the word marriage to either drop gender specifications or supplement them with secondary definitions to include gender-neutral language or explicit recognition of same-sex unions.[40][41] The Oxford English Dictionary has recognized same-sex marriage since 2000.[42]

Alan Dershowitz and others have suggested reserving the word marriage for religious contexts as part of privatizing marriage, and in civil and legal contexts using a uniform concept of civil unions, in part to strengthen the separation between church and state.[43] Jennifer Roback Morse, the president of the anti-same-sex marriage group National Organization for Marriage's Ruth Institute project,[44] claims that the conflation of marriage with contractual agreements is a threat to marriage.[45]

Some publications that oppose same-sex marriage, such as WorldNetDaily and Baptist Press, have an editorial style policy of placing the word marriage in scare quotes ("marriage") when it is used in reference to same-sex couples.[citation needed] In the United States, the mainstream press has generally abandoned this practice.[33] Cliff Kincaid of the conservative Accuracy in Media argued for use of quotation marks on the grounds that marriage was a legal status denied same-sex couples by most U.S. state governments.[46] Same-sex marriage supporters argue that the use of scare quotes is an editorialization that implies illegitimacy.[47]

Opponents of same-sex marriage such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, and the Southern Baptist Convention use the term traditional marriage to mean marriages between one man and one woman.[48][49][50]

Studies

The American Anthropological Association stated on February 26, 2004:[22]

The results of more than a century of anthropological research on households, kinship relationships, and families, across cultures and through time, provide no support whatsoever for the view that either civilization or viable social orders depend upon marriage as an exclusively heterosexual institution. Rather, anthropological research supports the conclusion that a vast array of family types, including families built upon same-sex partnerships, can contribute to stable and humane societies.

Research findings from 1998–2015 from the University of Virginia, Michigan State University, Florida State University, the University of Amsterdam, the New York State Psychiatric Institute, Stanford University, the University of California-San Francisco, the University of California-Los Angeles, Tufts University, Boston Medical Center, the Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health and independent researchers also support the findings of this study.[51]

Health

In 2010, a Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health study examining the effects of institutional discrimination on the psychiatric health of lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) individuals found an increase in psychiatric disorders, including a more than doubling of anxiety disorders, among the LGB population living in states that instituted bans on same-sex marriage. According to the author, the study highlighted the importance of abolishing institutional forms of discrimination, including those leading to disparities in the mental health and well-being of LGB individuals. Institutional discrimination is characterized by societal-level conditions that limit the opportunities and access to resources by socially disadvantaged groups.[52][53]

Gay activist Jonathan Rauch has argued that marriage is good for all men, whether homosexual or heterosexual, because engaging in its social roles reduces men's aggression and promiscuity.[54][55] The data of current psychological and other social science studies on same-sex marriage in comparison to mixed-sex marriage indicate that same-sex and mixed-sex relationships do not differ in their essential psychosocial dimensions; that a parent's sexual orientation is unrelated to their ability to provide a healthy and nurturing family environment; and that marriage bestows substantial psychological, social, and health benefits. Same-sex parents and carers and their children are likely to benefit in numerous ways from legal recognition of their families, and providing such recognition through marriage will bestow greater benefit than civil unions or domestic partnerships.[56][57]

The American Psychological Association stated in 2004: "...Denial of access to marriage to same-sex couples may especially harm people who also experience discrimination based on age, race, ethnicity, disability, gender and gender identity, religion, socioeconomic status and so on." It has also averred that same-sex couples who may only enter into a civil union, as opposed to a marriage, "are denied equal access to all the benefits, rights, and privileges provided by federal law to those of married couples," which has adverse effects on the well-being of same-sex partners.[15]

In 2009, a pair of economists at Emory University tied the passage of state bans on same-sex marriage in the US to an increase in the rates of HIV infection.[58][59] The study linked the passage of a same-sex marriage ban in a state to an increase in the annual HIV rate within that state of roughly 4 cases per 100,000 population.[60]

Parenting

Many psychologist organizations have concluded that children stand to benefit from the well-being that results when their parents' relationship is recognized and supported by society's institutions, e.g. civil marriage. For example, the Canadian Psychological Association stated in 2006 that "parents' financial, psychological and physical well-being is enhanced by marriage and that children benefit from being raised by two parents within a legally-recognized union."[18] The CPA stated in 2003 the stressors encountered by gay and lesbian parents and their children are more likely the result of the way society treats them than because of any deficiencies in fitness to parent.[18]

The American Academy of Pediatrics concluded in 2006, in an analysis published in the journal Pediatrics:[56]

There is ample evidence to show that children raised by same-gender parents fare as well as those raised by heterosexual parents. More than 25 years of research have documented that there is no relationship between parents' sexual orientation and any measure of a child's emotional, psychosocial, and behavioral adjustment. These data have demonstrated no risk to children as a result of growing up in a family with 1 or more gay parents. Conscientious and nurturing adults, whether they are men or women, heterosexual or homosexual, can be excellent parents. The rights, benefits, and protections of civil marriage can further strengthen these families.

Opinion polling

Numerous polls and studies on the issue have been conducted, including those that were completed throughout the first decade of the 21st century. A consistent trend of increasing support for same-sex marriage has been revealed across the world. Much of the research that was conducted in developed countries in the first decade of the 21st century shows a majority of people in support of same-sex marriage. Support for legal same-sex marriage has increased across every age group, political ideology, religion, gender, race and region of various developed countries in the world.[61][62][63][64][65]

Recent polling in the United States has shown a further increase in public support for same-sex marriage. When adults were asked in 2005 if they thought "marriages between homosexuals should or should not be recognized by the law as valid, with the same rights as traditional marriages", 28 percent replied in the affirmative, while 68 percent replied in the negative (the remaining 4 percent stated that they were unsure). When adults were asked in March 2013 if they supported or opposed same-sex marriage, 50 percent said they supported same-sex marriage, while 41 percent were opposed, and the remaining 9 percent stated that they were unsure.[66] Various detailed polls and studies on same-sex marriage that were conducted in several countries show that support for same-sex marriage generally increases with higher levels of education and decreases with age.[67][68][69][70][71]

- Opinion polls for same-sex marriage by country

| Country | Pollster | Year | For[a] | Against[a] | Neither[b] | Margin of error |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPSOS | 2023 | 26% |

73% (74%) |

1% | [72] | ||

| Institut d'Estudis Andorrans | 2013 | 70% (79%) |

19% (21%) |

11% | [73] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 12% | – | – | [74] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 69% (81%) |

16% [9% support some rights] (19%) |

15% not sure | ±5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 67% (72%) |

26% (28%) |

7% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2015 | 3% (3%) |

96% (97%) |

1% | ±3% | [77] [78] | |

| 2021 | 46% |

[79] | |||||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 64% (73%) |

25% [13% support some rights] (28%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 75% (77%) |

23% | 2% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 65% (68%) |

30% (32%) |

5% | [80] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2015 | 11% | – | – | [81] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2015 | 16% (16%) |

81% (84%) |

3% | ±4% | [77] [78] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 69% (78%) |

19% [9% support some rights] (22%) |

12% not sure | ±5% | [75] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 79% | 19% | 2% not sure | [80] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 8% | – | – | [81] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 35% | 65% | – | ±1.0% | [74] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 26% (27%) |

71% (73%) |

3% | [72] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 51% (62%) |

31% [17% support some rights] (38%) |

18% not sure | ±3.5% [c] | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 52% (57%) |

40% (43%) |

8% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 17% (18%) |

75% (82%) |

8% | [80] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 57% (58%) |

42% | 1% | [76] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 65% (75%) |

22% [10% support some rights] (25%) |

13% not sure | ±3.5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 79% (84%) |

15% (16%) |

6% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Cadem | 2024 | 77% (82%) |

22% (18%) |

2% | ±3.6% | [82] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2021 | 43% (52%) |

39% [20% support some rights] (48%) |

18% not sure | ±3.5% [c] | [83] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 46% (58%) |

33% [19% support some rights] (42%) |

21% | ±5% [c] | [75] | |

| CIEP | 2018 | 35% | 64% | 1% | [84] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 42% (45%) |

51% (55%) |

7% | [80] | ||

| Apretaste | 2019 | 63% | 37% | – | [85] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 50% (53%) |

44% (47%) |

6% | [80] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 60% | 34% | 6% | [80] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 93% | 5 | 2% | [80] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 10% | 90% | – | ±1.1% | [74] | |

| CDN 37 | 2018 | 45% | 55% | - | [86] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2019 | 23% (31%) |

51% (69%) |

26% | [87] | ||

| Universidad Francisco Gavidia | 2021 | 82.5% | – | [88] | |||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 41% (45%) |

51% (55%) |

8% | [80] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 76% (81%) |

18% (19%) |

6% | [80] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 62% (70%) |

26% [16% support some rights] (30%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 82% (85%) |

14% (15%) |

4% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 79% (85%) |

14 (%) (15%) |

7% | [80] | ||

| Women's Initiatives Supporting Group | 2021 | 10% (12%) |

75% (88%) |

15% | [89] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 73% (83%) |

18% [10% support some rights] (20%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 80% (82%) |

18% | 2% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 84% (87%) |

13%< | 3% | [80] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 48% (49%) |

49% (51%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 57% (59%) |

40% (41%) |

3% | [80] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 12% | 88% | – | ±1.4%c | [74] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 23% | 77% | – | ±1.1% | [74] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 21% | 79% | – | ±1.3% | [81] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 5% | 95% | – | ±0.3% | [74] | |

| CID Gallup | 2018 | 17% (18%) |

75% (82%) |

8% | [90] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 58% (59%) |

40% (41%) |

2% | [76] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 44% (56%) |

35% [18% support some rights] (44%) |

21% not sure | ±5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 31% (33%) |

64% (67%) |

5% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 42% (45%) |

52% (55%) |

6% | [80] | ||

| Gallup | 2006 | 89% | 11% | – | [91] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 53% (55%) |

43% (45%) |

4% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 5% | 92% (95%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 68% (76%) |

21% [8% support some rights] (23%) |

10% | ±5%[c] | [75] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 86% (91%) |

9% | 5% | [80] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 36% (39%) |

56% (61%) |

8% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 58% (66%) |

29% [19% support some rights] (33%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 73% (75%) |

25% | 2% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 69% (72%) |

27% (28%) |

4% | [80] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 16% | 84% | – | ±1.0% | [74] | |

| Kyodo News | 2023 | 64% (72%) |

25% (28%) |

11% | [92] | ||

| Asahi Shimbun | 2023 | 72% (80%) |

18% (20%) |

10% | [93] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 42% (54%) |

31% [25% support some rights] (40%) |

22% not sure | ±3.5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 68% (72%) |

26% (28%) |

6% | ±2.75% | [76] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2016 | 7% (7%) |

89% (93%) |

4% | [77] [78] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 9% | 90% (91%) |

1% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 20% (21%) |

77% (79%) |

3% | [72] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 36% | 59% | 5% | [80] | ||

| Liechtenstein Institut | 2021 | 72% | 28% | 0% | [94] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 39% | 55% | 6% | [80] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 84% | 13% | 3% | [80] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 17% | 82% (83%) |

1% | [76] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 74% | 24% | 2% | [80] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 55% | 29% [16% support some rights] | 17% not sure | ±3.5%[c] | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 63% (66%) |

32% (34%) |

5% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Europa Libera Moldova | 2022 | 14% | 86% | [95] | |||

| IPSOS | 2023 | 36% (37%) |

61% (63%) |

3% | [72] | ||

| Lambda | 2017 | 28% (32%) |

60% (68%) |

12% | [96] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 77% | 15% [8% support some rights] | 8% not sure | ±5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 89% (90%) |

10% | 1% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 94% | 5% | 2% | [80] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 70% (78%) |

20% [11% support some rights] (22%) |

9% | ±3.5% | [97] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 25% | 75% | – | ±1.0% | [74] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 2% | 97% (98%) |

1% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 20% (21%) |

78% (80%) |

2% | [72] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2017 | 72% (79%) |

19% (21%) |

9% | [77] [78] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 22% | 78% | – | ±1.1% | [74] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 26% | 74% | – | ±0.9% | [74] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 36% |

44% [30% support some rights] | 20% | ±5% [c] | [75] | |

| SWS | 2018 | 22% (26%) |

61% (73%) |

16% | [98] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 51% (54%) |

43% (46%) |

6% | [99] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 41% (43%) |

54% (57%) |

5% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| United Surveys by IBRiS | 2024 | 50% (55%) |

41% (45%) |

9% | [100] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 50% | 45% | 5% | [80] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 80% (84%) |

15% [11% support some rights] (16%) |

5% | [97] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 81% | 14% | 5% | [80] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 25% (30%) |

59% [26% support some rights] (70%) |

17% | ±3.5% | [97] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 25% | 69% | 6% | [80] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2021 | 17% (21%) |

64% [12% support some rights] (79%) |

20% not sure | ±4.8% [c] | [83] | |

| FOM | 2019 | 7% (8%) |

85% (92%) |

8% | ±3.6% | [101] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 9% | 91% | – | ±1.0% | [74] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 11% | 89% | – | ±0.9% | [74] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 4% | 96% | – | ±0.6% | [74] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 24% (25%) |

73% (75%) |

3% | [72] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 33% | 46% [21% support some rights] | 21% | ±5% [c] | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 45% (47%) |

51% (53%) |

4% | [76] | ||

| Focus | 2024 | 36% (38%) |

60% (62%) |

4% | [102] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 37% | 56% | 7% | [80] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 62% (64%) |

37% (36%) |

2% | [80] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 53% | 32% [14% support some rights] | 13% | ±5% [c] | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 38% (39%) |

59% (61%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 36% | 37% [16% support some rights] | 27% not sure | ±5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 41% (42%) |

56% (58%) |

3% | [76] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 73% (80%) |

19% [13% support some rights] (21%) |

9% not sure | ±3.5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 87% (90%) |

10% | 3% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 88% (91%) |

9% (10%) |

3% | [80] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 23% (25%) |

69% (75%) |

8% | [76] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 18% | – | – | [81] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 78% (84%) |

15% [8% support some rights] (16%) |

7% not sure | ±5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 92% (94%) |

6% | 2% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 94% | 5% | 1% | [80] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 54% (61%) |

34% [16% support some rights] (39%) |

13% not sure | ±3.5% | [97] | |

| CNA | 2023 | 63% | 37% | [103] | |||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 45% (51%) |

43% (49%) |

12% | [76] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 58% | 29% [20% support some rights] | 12% not sure | ±5%[c] | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 60% (65%) |

32% (35%) |

8% | [76] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 16% | – | – | [81] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 18% (26%) |

52% [19% support some rights] (74%) |

30% not sure | ±5% [c] | [75] | |

| Rating | 2023 | 37% (47%) |

42% (53%) |

22% | ±1.5% | [104] | |

| YouGov | 2023 | 77% (84%) |

15% (16%) |

8% | [105] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 66% (73%) |

24% [11% support some rights] (27%) |

10% not sure | ±3.5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 74% (77%) |

22% (23%) |

4% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 51% (62%) |

32% [14% support some rights] (39%) |

18% not sure | ±3.5% | [75] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 63% (65%) |

34% (35%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [76] | |

| LatinoBarómetro | 2023 | 78% (80%) |

20% | 2% | [106] | ||

| Equilibrium Cende | 2023 | 55% (63%) |

32% (37%) |

13% | [107] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 65% (68%) |

30% (32%) |

5% | [97] |

History

Ancient

A reference to same-sex marriage (by the Egyptians and Canaanites) exists in the Talmud. The Old Testament prohibited homosexual relations (Lev. 18:22, 20:13), and the Jewish sages provide the reason for this as being that the Hebrews were warned not to "follow the acts of the land of Egypt or the acts of the land of Canaan." The sages explicitly state: "what did [the Egyptians and Canaanites] do? A man would marry a man and a woman [marry] a woman."[108]

What is arguably the first historical mention of the performance of same-sex marriages occurred during the early Roman Empire according to controversial[109] historian John Boswell.[110] These were usually reported in a critical or satirical manner.[111]

Child emperor Elagabalus referred to his chariot driver, a blond slave from Caria named Hierocles, as his husband.[112] He also married an athlete named Zoticus in a lavish public ceremony in Rome amidst the rejoicings of the citizens.[113][114][115]

The first Roman emperor to have married a man was Nero, who is reported to have married two other males on different occasions. The first was with one of Nero's own freedmen, Pythagoras, with whom Nero took the role of the bride.[116] Later, as a groom, Nero married Sporus, a young boy, to replace the adolescent female concubine he had killed[117][118] and married him in a very public ceremony with all the solemnities of matrimony, after which Sporus was forced to pretend to be the female concubine that Nero had killed and act as though they were really married.[117] A friend gave the "bride" away as required by law. The marriage was celebrated in both Greece and Rome in extravagant public ceremonies.[119]

It should be noted, however, that conubium existed only between a civis Romanus and a civis Romana (that is, between a male Roman citizen and a female Roman citizen), so that a marriage between two Roman males (or with a slave) would have no legal standing in Roman law (apart, presumably, from the arbitrary will of the emperor in the two aforementioned cases).[120] Furthermore, according to Susan Treggiari, "matrimonium was then an institution involving a mother, mater. The idea implicit in the word is that a man took a woman in marriage, in matrimonium ducere, so that he might have children by her."[121]

In 342 AD, Christian emperors Constantius II and Constans issued a law in the Theodosian Code (C. Th. 9.7.3) prohibiting same-sex marriage in Rome and ordering execution for those so married.[122]

Contemporary

Writing in Harvard Magazine in 2013, legal historian Michael Klarman wrote that while there was a growth of gay rights activism in the 1970s United States, "Marriage equality was not then a priority." He argued that many gay people were not initially interested in marriage, deeming it to be a traditionalist institution, and that the search for legal recognition of same-sex relationships began in the late 1980s.[123] Others, such as Faramerz Dabhoiwala writing for The Guardian, say that the modern movement began in the 1990s.[124]

Denmark was the first country to recognize a legal relationship for same-sex couples, establishing "registered partnerships" in 1989. This gave those in same-sex relationships "most rights of married heterosexuals, but not the right to adopt or obtain joint custody of a child".[125] In 2001, the Netherlands[nb 2] became the first country to permit same-sex marriages.[126] Since then same-sex marriages have been permitted and mutually recognized by Belgium (2003), Spain (2005), Canada (2005), South Africa (2006), Norway (2009), Sweden (2009), Portugal (2010), Iceland (2010), Argentina (2010), Denmark (2012), Brazil (2013), France (2013), Uruguay (2013), New Zealand[nb 3] (2013), Luxembourg (2015), the United States[nb 5] (2015), Ireland (2015), Colombia (2016), Finland (2017), Malta (2017), Germany (2017) and Australia (2017). In Mexico, same-sex marriages are performed in a number of states and recognised in all thirty-one states. In Nepal and Taiwan, their recognition has been judicially mandated but not yet legislated.[127] Furthermore, most jurisdictions of the United Kingdom[nb 4] have also legalised same-sex marriage, with the first being England and Wales in March 2014, followed by Scotland in December of the same year. Same-sex marriage is however not legal in Northern Ireland.

In December 2017 the Constitutional Court of Austria ruled in a discrimination case that same-sex marriage will become legal in that nation on 1 January 2019 if Parliament does not legalize it before that date.[128]

Timeline

International organisations

European Court of Human Rights

In 2010, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled in Schalk and Kopf v Austria, a case involving an Austrian same-sex couple who were denied the right to marry.[129] The court found, by a vote of 4 to 3, that their human rights had not been violated.[130]

British Judge Sir Nicolas Bratza, then head of the European Court of Human Rights, delivered a speech in 2012 that signaled the court was ready to declare same-sex marriage a "human right", as soon as enough countries fell into line.[131][132][133]

Article 12 of the European Convention on Human Rights states that: "Men and women of marriageable age have the right to marry and to found a family, according to the national laws governing the exercise of this right",[134] not limiting marriage to those in a heterosexual relationship. However, the ECHR stated in Schalk and Kopf v Austria that this provision was intended to limit marriage to heterosexual relationships, as it used the term "men and women" instead of "everyone".[129]

European Union

On 12 March 2015, the European Parliament passed a non-binding resolution recognising the right to marry for those of the same sex as a human and civil rights issue.[135][136][137]

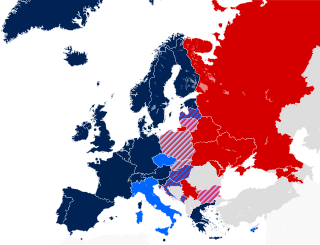

Same-sex marriage around the world

Same-sex marriage has been legalized (nationwide or in some parts) in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico,[nb 1] the Netherlands,[nb 2] New Zealand,[nb 3] Norway, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom[nb 4], the United States,[nb 5] and Uruguay.

The status of same-sex marriage is a complicated matter in a number of other nations. In Mexico marriages are recognized by all sub-national jurisdictions and by the federal government.[138] On 3 June 2015, Mexico's Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation released a "jurisprudential thesis" declaring the current purpose of marriage, which is procreation, as unconstitutional and discriminatory towards same-sex relationships. Courts nationwide must now authorize marriages between people of the same-sex through injunctions, a process slower and more expensive than opposite-sex marriage.[139] Israel does not recognize same-sex marriages performed in its territory, but same-sex marriages performed in foreign jurisdictions are recorded strictly "for statistical purposes", thereby avoiding official recognition of same-sex marriages by the state.[140]

Legal recognition

Argentina

On 15 July 2010, the Argentine Senate approved a bill extending marriage rights to same-sex couples. It was supported by the Government of President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and opposed by the Catholic Church.[141] Polls showed that nearly 70% of Argentines supported giving gay people the same marital rights as heterosexuals.[142] The law came into effect on 22 July 2010 upon promulgation by the Argentine President.[143]

Australia

The Australian Parliament passed a bill legalising same-sex marriage on 7 December 2017.[144] The bill received royal assent on 8 December, and took effect on 9 December 2017.[145][146] The law removed the ban on same-sex marriage which previously existed and followed a voluntary postal survey held from September to November 2017, which returned a 61.6% "Yes" vote in favour of same-sex marriage.[147]

Belgium

Belgium became the second country in the world to legally recognize same-sex marriages when a bill passed by the Belgian Federal Parliament took effect on 1 June 2003.[148] Originally, Belgium allowed the marriages of foreign same-sex couples only if their country of origin also allowed these unions, however legislation enacted in October 2004 permits any couple to marry if at least one of the spouses has lived in the country for a minimum of three months. A 2006 statute legalized adoption by same-sex spouses.[149]

Brazil

Brazil's Supreme Court ruled in May 2011 that same-sex couples are legally entitled to legal recognition of cohabitation (known as [união estável] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), one of the two possible family entities in Brazilian legislation, it includes all family and married couple rights in Brazil – besides automatic opt-in for one of four systems of property share and automatic right to inheritance – and was available for all same-sex couples since the same date), turning same-sex marriage legally possible as a consequence, and just stopping short of equalization of same-sex marriage (potentially confusing, a civil marriage or [casamento civil] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is often rendered as [união civil] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in legal Brazilian Portuguese; a same-sex marriage is a [casamento civil homoafetivo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or an [união civil homoafetiva] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)).[150]

Between mid-2011 and May 2013, same-sex couples had their cohabitation issues converted into marriages in several Brazil states with the approval of a state judge. All legal Brazilian marriages were always recognized all over Brazil.[151]

In November 2012, the Court of Bahia equalized marriage in the state of Bahia.[152][153]

In December 2012, the state of São Paulo likewise had same-sex marriage allowed in demand by court order.[154] Same-sex marriages also became equalized in relation to opposite-sex ones between January 2012 and April 2013 by court order in Alagoas, Ceará, Espírito Santo, the Federal District, Mato Grosso do Sul, Paraíba, Paraná, Piauí, Rondônia, Santa Catarina and Sergipe, and in Santa Rita do Sapucaí, a municipality in Minas Gerais; in Rio de Janeiro, the State Court facilitated its realization by district judges in agreement with the equalization (instead of ordering notaries to accept same-sex marriages in demand as all others).[155]

On 14 May 2013, the Justice's National Council of Brazil issued a ruling requiring all civil registers of the country to perform same-sex marriages by a 14–1 vote, thus legalizing same-sex marriage in the entire country.[156][157][158] The resolution came into effect on 16 May 2013.[159][160]

In March 2013, polls suggested that 47% of Brazilians supported marriage equalization and 57% supported adoption equalization for same-sex couples.[161]

Polls in June 2013 also supported the conclusion that the division of opinion between acceptance and rejection of same-sex marriage is in about equal halves. When the distinction between same-sex unions that are not termed marriages in relation to same-sex marriage is made, the difference in the numbers of approval and disapproval is still insignificant, below 1%; the most frequent reason for disapproval is a supposed 'unnaturalness' of same-sex relationships, followed by religious beliefs.[162][163]

Canada

Legal recognition of same-sex marriage in Canada followed a series of constitutional challenges based on the equality provisions of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In the first such case, Halpern v. Canada (Attorney General), same-sex marriage ceremonies performed in Ontario on 14 January 2001 were subsequently validated when the common law, mixed-sex definition of marriage was held to be unconstitutional. Similar rulings had legalized same-sex marriage in eight provinces and one territory when the 2005 Civil Marriage Act defined marriage throughout Canada as "the lawful union of two persons to the exclusion of all others."

Colombia

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Colombia since April 2016. The country's Constitutional Court ruled, on 28 April 2016 that same-sex couples are allowed to enter into civil marriages in the country and that judges and notaries are barred from refusing to perform same-sex weddings.[164][165][166] On 7 April 2016, the Court ruled that marriage doesn't only apply to opposite-sex couples.[167][168][169][170] Almost all advances in relationship recognition rights for same-sex couples has come from sweeping rulings of the Court. A series of rulings by the court that started in February 2007 meant that same-sex couples could apply for all the rights that heterosexual couples have in de facto unions (uniones de hecho).[171][172]

On 26 July 2011, the Constitutional Court of Colombia ordered the Congress to pass the legislation giving same-sex couples similar rights to marriage by 20 June 2013. If such a law were not passed by then, same-sex couples would be granted these rights automatically.[173][174]

In October 2012, Senator Armando Benedetti introduced a bill legalizing same-sex marriage. It initially only allowed for civil unions, but he amended the text.[175] The Senate's First Committee approved the bill on 4 December 2012.[176][177] On 24 April 2013, the bill was defeated in the full Senate on a 51–17 vote.[178]

On 24 July 2013, a civil court judge in Bogotá declared a male same-sex couple legally married, after a ruling on 11 July 2013 accepting the petition. This was the first same-sex couple married in Colombia.[179][180]

In September 2013, two civil court judges married two same-sex couples.[181] The first marriage was challenged by a conservative group, and it was initially annulled. Nevertheless, in October a High Court (Tribunal Supremo de Bogotá) maintained the validity of that marriage.[182][183]

Denmark

On 7 June 2012, the Folketing (Danish Parliament) approved new laws regarding same-sex civil and religious marriage. These laws permit same-sex couples to get married in the Church of Denmark. The bills received royal assent on 12 June and took effect on 15 June 2012.[184] Denmark was previously the first country in the world to legally recognize same-sex couples through registered partnerships in 1989.[185][186]

On 26 May 2015, Greenland, one of Denmark's two other constituent countries in the Realm of Denmark, unanimously passed a law legalising same-sex marriage.[187][188] The first same-sex couple to marry in Greenland married on 1 April 2016, the day the law went into effect.[189]

On 17 November 2015, in the Faroe Islands (the realm's other constituent country), a same-sex marriage bill entered Parliament (Løgting). The bill passed its second reading on 26 April and was approved at its third reading on 29 April 2016 by 19 votes to 14.[190] The law required ratification in the Danish Parliament, which provided it on 25 April 2017.[191] The Faroese law allows civil marriages for same-sex couples and exempts the Church of the Faroe Islands from being required to officiate same-sex weddings. The law took effect on 1 July 2017.[192]

Finland

Registered partnerships have been legal in Finland since 2002.[193] In 2010, Minister of Justice Tuija Brax said her Ministry was preparing to amend the Marriage Act to allow same-sex marriage by 2012.[194] On 27 February 2013, the bill was rejected by the Legal Affairs Committee of the Finnish Parliament on a vote of 9–8. A citizens' initiative was launched to put the issue before the Parliament of Finland.[195] The initiative gathered the required 50,000 signatures of Finnish citizens in one day and exceeded 107,000 signatures by the time the media reported the figures.[196] The campaign collected 166,000 signatures and the initiative was presented to the Parliament in December 2013.[197] The initiative went to introductory debate on 20 February 2014 and was sent again to the Legal Affairs Committee.[198][199] On 25 June, the bill was rejected by the Legal Affairs Committee on a vote of 10–6 and the third time on 20 November 2014, by 9–8.[200] It faced the first vote in full session on 28 November 2014,[201] which passed the bill 105–92. The bill passed the second and final vote by 101–90 on 12 December 2014,[202] and was signed by the President on 20 February 2015.

The law took effect on 1 March 2017.[203] It was the first time a citizens' initiative has been approved by the Finnish Parliament.[193]

France

Since November 1999, France has a civil union law that is open to both opposite-sex and same-sex couples. Following the election of François Hollande as President of France in May 2012 and the subsequent legislative election in which the Socialist Party took a majority of seats in the French National Assembly, the new Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault stated that a same-sex marriage bill had been drafted and would be passed.[204]

The French Government introduced a bill to legalize same-sex marriage, Bill 344, in the National Assembly on 17 November 2012. Article 1 of the bill defining marriage as an agreement between two people was passed on 2 February 2013 in its first reading by a 249–97 vote. On 12 February 2013, the National Assembly approved the entire bill in a 329–229 vote.[205]

On 12 April 2013, the upper house of the French Parliament voted to legalise same-sex marriage.[206] On 23 April 2013, the law was approved by the National Assembly in a 331–225 vote.[207] Law No.2013-404 grants same-sex couples living in France, including foreigners provided at least one of the partners has their domicile or residence in France, the legal right to get married. The law also allows the recognition in France of same-sex couples' marriages that occurred abroad before the bill's enactment.[208]

Following the announcement of the French Parliament's vote results, those in opposition to the legalisation of same-sex marriage in France participated in public protests. In both Paris and Lyon, violence erupted as protesters clashed with police; the issue has mobilised right-wing forces in the country, including neo-Nazis.[209]

The main right-wing opposition party UMP challenged the law in the Constitutional Council, which had one month to rule on whether the law conformed to the Constitution. The Constitutional Council had previously ruled that the issue of same-sex marriage was one for the Parliament to decide and there was only little hope for UMP to overturn the Parliament's vote.[210]

On 17 May 2013, the Constitutional Council declared the bill legal in its entire redaction. President Hollande signed it into law on 18 May 2013.[211]

Germany

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Germany since 1 October 2017. A bill recognising marriages and adoption rights for same-sex couples passed the Bundestag on 30 June 2017 after the ruling CDU/CSU Coalition Government, led by Chancellor Angela Merkel, allowed parliamentarians a conscience vote on the legislation.[212] Previous attempts by smaller parties to introduce same-sex marriage were blocked by the CDU/CSU over several years. The bill was signed into law by German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier on 20 July and came into effect on 1 October 2017.[213]

Prior to the legalisation of same-sex marriage, Germany was one of the first countries to legislate registered partnerships (Eingetragene Lebenspartnerschaft) for same-sex couples, which provided most though not all the rights of marriage. The law came into effect on 1 August 2001, and the act was progressively amended on subsequent occasions to reflect court rulings expanding the rights of registered partners.

Iceland

Same-sex marriage was introduced in Iceland through legislation establishing a gender-neutral definition of marriage introduced by the Coalition Government of the Social Democratic Alliance and Left-Green Movement. The legislation was passed unanimously by the Icelandic Althing on 11 June 2010, and took effect on 27 June 2010, replacing an earlier system of registered partnerships for same-sex couples.[214][215] Prime Minister Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir and her partner were among the first married same-sex couples in the country.[216]

Ireland

Ireland held a referendum on 22 May 2015. The referendum proposed to add to the Irish Constitution: "marriage may be contracted in accordance with law by two persons without distinction as to their sex". The proposal approved; with 62% of voters supporting same-sex marriage. On 29 August 2015, the Irish President, Michael D. Higgins, signed the result of the May referendum into law,[217] which made Ireland the first country in the world to approve same-sex marriage at a nationwide referendum.[218] Same-sex marriage became formally legally recognised in Ireland on 16 November 2015.[219] Prior to this, the Civil Partnership and Certain Rights and Obligations of Cohabitants Act 2010 allowed same sex couples to enter civil partnerships. The Act came into force on 1 January 2011 and gave same-sex couples rights and responsibilities similar to, but not equal to, those of civil marriage.[220]

Luxembourg

The Parliament approved a bill to legalise same-sex marriage on 18 June 2014.[221] The law was published in the official gazette on 17 July and took effect on 1 January 2015.[222][223][224] On 15 May 2015, Luxembourg became the first country in the European Union to have a prime minister who is in a same sex marriage, and the second one in Europe. Prime Minister Xavier Bettel married Gauthier Destenay, with whom he had been in a civil partnership since 2010.

Malta

Malta has recognized same-sex unions since April 2014, following the enactment of the Civil Unions Act, first introduced in September 2013. It established civil unions with same rights, responsibilities, and obligations as marriage, including the right of joint adoption and recognition of foreign same sex marriage.[225] The Maltese Parliament gave final approval to the legislation on 14 April 2014 by a vote of 37 in favour and 30 abstentions. President Marie Louise Coleiro Preca signed it into law on 16 April. The first foreign same sex marriage was registered on 29 April 2014 and the first civil union was performed on 14 June 2014.[225]

On 21 February 2017, Minister for Social Dialogue, Consumer Affairs and Civil Liberties Helena Dalli said that she is preparing a bill to legalise same-sex marriage.[226] The bill was presented to Parliament on 5 July 2017, with no alteration.[227] The bill's last reading took place in Parliament on 12 July 2017, where it was approved 66-1. It was signed into law and published in the Government Gazette on 1 August 2017.[228] Malta became the 14th country in Europe to legalise same-sex marriage.[229][230]

Mexico

Same-sex couples can marry in Mexico City and in the states of Baja California, Campeche, Chiapas, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Colima, Jalisco, Michoacán, Morelos, Nayarit, Puebla and Quintana Roo as well as in some municipalities in Querétaro. In individual cases, same-sex couples have been given judicial approval to marry in all other states. Since August 2010, same-sex marriages performed within Mexico are recognized by the 31 states without exception.

On 21 December 2009, the Federal District's Legislative Assembly legalized same-sex marriages and adoption by same-sex couples. The law was enacted eight days later and became effective in early March 2010.[231] On 10 August 2010, the Mexican Supreme Court ruled that while not every state must grant same-sex marriages, they must all recognize those performed where they are legal.[232]

On 28 November 2011, the first two same-sex marriages occurred in Quintana Roo after it was discovered that Quintana Roo's Civil Code did not explicitly prohibit same-sex marriage,[233] but these marriages were later annulled by the Governor of Quintana Roo in April 2012.[234] In May 2012, the Secretary of State of Quintana Roo reversed the annulments and allowed for future same-sex marriages to be performed in the state.[235]

On 11 February 2014, the Congress of Coahuila approved adoptions by same-sex couples and a bill legalizing same-sex marriages passed on 1 September 2014 making Coahuila the second state to reform its Civil Code to allow for legal same-sex marriages.[236] It took effect on 17 September, and the first couple married on 20 September.[237]

On 12 June 2015, the Governor of Chihuahua announced that his administration would no longer oppose same-sex marriages within the state. The order was effective immediately, thus making Chihuahua the third state to legalize such unions.[238][239]

On 3 June 2015, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation released a "jurisprudential thesis" which deems the state-laws defining marriage as a union between a man and a woman unconstitutional. The ruling standardized court procedures across Mexico to authorize same-sex marriages. However, the process is still lengthy and more expensive than that for an opposite-sex marriage, as[139] the ruling did not invalidate any state laws, meaning gay couples will be denied the right to wed and will have to turn to the courts for individual injunctions. However, given the nature of the ruling, judges and courts throughout Mexico must approve any application for a same-sex marriage.[240] The official release of the thesis was on 19 June 2015, which took effect on 22 June 2015.[241]

On 25 June 2015, following the Supreme Court's ruling striking down district same-sex marriage bans, the Civil Registry of Guerrero announced that they had planned a collective same-sex marriage ceremony for 10 July 2015 and indicated that there would have to be a change to the law to allow gender-neutral marriage, passed through the state Legislature before the official commencement.[242] The registry announced more details of their plan, advising that only select registration offices in the state would be able to participate in the collective marriage event.[243]

The state Governor instructed civil agencies to approve same-sex marriage licenses. On 10 July 2015, 20 same-sex couples were married by Governor Rogelio Ortega in Acapulco.[244] On 13 January 2016, the head of the Civil Registry of Acapulco announced that all marriages that took place on 10 July 2015 by the Governor and his wife were void and not legal as same-sex marriage is not legal in Guerrero, unless couples are granted amparo beforehand.[245] On 13 February 2016, however, the head of Guerrero's State Civil Registry department announced that same-sex couples could marry in any of the jurisdictions that want to marry the couples and criticised Acapulco's Civil Registry and other civil registries throughout the state for not allowing these kinds of weddings.[246]

On 17 December 2015, the Congress of Nayarit approved a bill legalizing same-sex marriage.[247] In January 2016, the Mexican Supreme Court declared Jalisco's Civil Code unconstitutional for limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples, effectively legalizing same-sex marriage in the state.[248] On 10 May 2016, the Congress of Campeche passed a same-sex marriage bill.[249] On 18 May 2016, both Michoacán and Morelos passed bills allowing for same-sex marriage to be legal.[250][251] On 25 May 2016, a bill to legalize same-sex marriage in Colima was approved by the state Congress.[252] In July and August 2017, respectively, the Mexican Supreme Court invalidated same-sex marriage bans in the states of Chiapas and Puebla.[253][254]

On 17 May 2016, the President of Mexico, Enrique Peña Nieto, signed an initiative to change the country's Constitution, which would legalize same-sex marriage throughout Mexico.[255] On 9 November 2016, the Committee on Constitutional Issues of the Chamber of Deputies rejected the initiative 19 votes to 8.[256]

Netherlands

The Netherlands was the first country to extend marriage laws to include same-sex couples, following the recommendation of a special commission appointed to investigate the issue in 1995. A same-sex marriage bill passed the House of Representatives and the Senate in 2000, taking effect on 1 April 2001.[257]

In the Dutch Caribbean special municipalities of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba, marriage is open to same-sex couples. A law enabling same-sex couples to marry in these municipalities passed and came into effect on 10 October 2012.[258] The Caribbean countries Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten, forming the remainder of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, do not perform same-sex marriages, but must recognize those performed in the Netherlands proper.

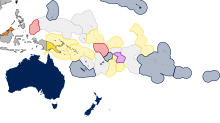

New Zealand

On 14 May 2012, Labour Party MP Louisa Wall stated that she would introduce a private member's bill, the Marriage (Definition of Marriage) Amendment Bill, allowing same-sex couples to marry.[259] The bill was submitted to the members' bill ballot on 30 May 2012.[260] It was drawn from the ballot and passed the first and second readings on 29 August 2012 and 13 March 2013, respectively.[261][262] The final reading passed on 17 April 2013 by 77 votes to 44.[263][264] The bill received royal assent from the Governor-General on 19 April and took effect on 19 August 2013.[265][266]

New Zealand marriage law only applies to New Zealand proper and the Ross Dependency in Antarctica. Other New Zealand territories, including Cook Islands, Niue and Tokelau, have their own marriage law and do not perform or recognise same-sex marriage.[267]

Norway

Same-sex marriage became legal in Norway on 1 January 2009 when a gender-neutral marriage bill was enacted after being passed by the Norwegian Parliament in June 2008.[268][269] Norway became the first Scandinavian country and the sixth country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage. Gender-neutral marriage replaced Norway's previous system of registered partnerships for same-sex couples. Couples in registered partnerships are able to retain that status or convert their registered partnership to a marriage. No new registered partnerships may be created.[270]

Portugal

Portugal created de facto unions ([união de facto] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in legal European Portuguese) similar to common-law marriage for cohabiting opposite-sex partners in 1999, and extended these unions to same-sex couples in 2001. However, the 2001 extension did not allow for same-sex adoption, either jointly or of stepchildren.[271]

On 11 February 2010, Parliament approved a bill legalizing same-sex marriage. The Portuguese President promulgated the law on 8 April 2010 and the law was effective on 5 June 2010, making Portugal the eighth country to legalize nationwide same-sex marriage; however, adoption was still denied for same-sex couples.[272]

On 24 February 2012, Parliament rejected two bills allowing same-sex couples to adopt children.[273] On 17 May 2013, the Portuguese Parliament approved a bill to recognise some adoption rights for same-sex couples in its first reading,[274][275][276] though it was later rejected. A bill granting adoption rights to same-sex parents and carers, as well as in-vitro fertilisation for lesbian relationships, was introduced in Parliament by then opposition Socialist and Left Block parties on 16 January 2015.[277] On 22 January, Parliament rejected the proposals.[278]

In December 2015, the Portuguese Parliament approved a bill to recognise adoptions rights for same-sex couples.[279][280][281] It came into effect in March 2016.

South Africa

Legal recognition of same-sex marriages in South Africa came about as a result of the Constitutional Court's decision in the case of Minister of Home Affairs v Fourie. The court ruled on 1 December 2005 that the existing marriage laws violated the equality clause of the Bill of Rights because they discriminated on the basis of sexual orientation. The court gave Parliament one year to rectify the inequality.

The Civil Union Act was passed by the National Assembly on 14 November 2006, by a vote of 230 to 41. It became law on 30 November 2006. South Africa is the fifth country, the first in Africa, and the second outside Europe, to legalize same-sex marriage.

Spain

Spain was the third country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage, which has been legal since 3 July 2005, and was supported by the majority of the Spanish people.[282][283]

In 2004, the nation's newly elected Socialist Government, led by President José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, began a campaign for its legalization, including the right of adoption by same-sex couples.[284] After much debate, the law permitting same-sex marriage was passed by the Cortes Generales (Spain's bicameral Parliament) on 30 June 2005. King Juan Carlos, who by law has up to 30 days to decide whether to grant royal assent to laws, indirectly showed his approval by signing it on 1 July 2005, the same day it reached his desk. The law was published on 2 July 2005.[285] In 2013, Pew Research Center declared Spain the most tolerant country of the world with homosexuality.[286][287] However, the studies did not include the Benelux or Scandinavian countries.

Sweden

Same-sex marriage in Sweden has been legal since 1 May 2009, following the adoption of a new gender-neutral law on marriage by the Swedish Parliament on 1 April 2009, making Sweden the seventh country in the world to open marriage to same-sex couples nationwide. Marriage replaced Sweden's registered partnerships for same-sex couples. Existing registered partnerships between same-sex couples remained in force with an option to convert them into marriages.[288][289] Same-sex marriages have been performed by the Church of Sweden since 2009.[290]

United Kingdom

Since 2005, same-sex couples have been allowed to enter into civil partnerships, a separate union providing the legal consequences of marriage. In 2006, the High Court rejected a legal bid by a British lesbian couple who had married in Canada to have their union recognised as a marriage in the UK rather than a civil partnership. In September 2011, the Coalition Government announced its intention to introduce same-sex civil marriage in England and Wales by the May 2015 general election.[291] However, unlike the Scottish Government's consultation, the UK Government's consultation for England and Wales did not include provision for religious ceremonies. In May 2012, three religious groups (Quakers, Liberal Judaism and Unitarians) sent a letter to David Cameron, asking that they be allowed to solemnise same-sex weddings.[292]

In June 2012, the UK Government completed the consultation to allow civil marriage for same-sex couples in England and Wales.[293] In its response to the consultation, the Government said that it also intended "...to enable those religious organisations that wish to conduct same-sex marriage ceremonies to do so, on a permissive basis only."[294] In December 2012, the Prime Minister, David Cameron, announced that, whilst he favoured allowing same-sex marriage within a religious context, provision would be made guaranteeing no religious institution would be required to perform such ceremonies.[295] On 5 February 2013, the House of Commons debated the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Bill, approving it in a 400–175 vote at the second reading.[296] The third reading took place on 21 May 2013, and was approved by 366 votes to 161.[297]

On 4 June 2013, the bill received its second reading in the House of Lords, after a blocking amendment was defeated by 390 votes to 148.[298] On 15 July 2013, the bill was given a third reading by the House of Lords, meaning that it had been passed, and so it was then returned to Commons for the consideration of the Lords' amendments. On 16 July 2013, the Commons accepted all of the Lords' amendments.[299] On 17 July 2013, the bill received royal assent becoming the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013, which came into force on 13 March 2014.[299] The first same-sex marriages took place on 29 March 2014.[300]

The Scottish Government conducted a three-month-long consultation which ended on 9 December 2011 and the analysis was published in July 2012.[301] Unlike the consultation held in England and Wales, Scotland considered both civil and religious same-sex marriage. Whilst the Scottish Government is in favour of same-sex marriage, it stated that no religious body would be forced to hold such ceremonies once legislation is enacted.[302] The Scottish consultation received more than 77,000 responses, and on 27 June 2013 the Government published the bill.[303] In order to preserve the freedom of both religious groups and individual clergy, the Scottish Government believed it necessary for changes to be made to the Equality Act 2010 and communicated with the UK Government on this matter; thus, the first same-sex marriages in Scotland did not occur until this had taken place.[304] Although the Scottish bill concerning same-sex marriage had been published, The Australian reported that LGBT rights campaigners, celebrating outside the UK Parliament on 15 July 2013 for the clearance of the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Bill in the House of Lords, declared that they would continue the campaign to extend same-sex marriage rights to both Scotland and Northern Ireland,[305] rather than solely Northern Ireland, where there are no plans to introduce such legislation. On 4 February 2014, the Scottish Parliament overwhelmingly passed legislation legalising same-sex marriage.[306] The bill received royal assent as the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Act 2014 on 12 March 2014.[307][308] The law took effect on 16 December 2014, with the first same-sex weddings occurring for those converting their civil partnerships into marriage.[309][310] Malcolm Brown and Joe Schofield from Tullibody were scheduled to be the first to be declared husband and husband just after midnight on 31 December, following a Humanist ceremony, but they were superseded by couples marrying on 16 December. Nonetheless, Brown and Schofield were married on Hogmanay.[311]

The Northern Ireland Executive has stated that it does not intend to introduce legislation allowing for same-sex marriage in Northern Ireland. Same-sex marriages from other jurisdictions are treated as civil partnerships.[312]

Of the fourteen British Overseas Territories, same-sex marriage has been legal in Akrotiri and Dhekelia and the British Indian Ocean Territory (for UK military personnel) since 3 June 2014, the Pitcairn Islands since 14 May 2015, the British Antarctic Territory since 13 October 2016, Gibraltar since 15 December 2016, Ascension Island since 1 January 2017, the Falkland Islands since 29 April 2017, Bermuda since 5 May 2017, and Tristan da Cunha since 4 August 2017. Of the three Crown dependencies, same-sex marriage has been legal in the Isle of Man since 22 July 2016 and in Guernsey since 2 May 2017.[313][314]

United States

The movement to obtain civil marriage rights and benefits for same-sex couples in the United States began in the 1970s.[315] and in 1971 the United States Supreme Court dismissed a case, Baker v. Nelson claiming such right on appeal, establishing it as a precedent as it came from mandatory appellate review. The issue did not become prominent in U.S. politics until the 1993 Hawaii Supreme Court decision in Baehr v. Lewin that declared that state's prohibition to be unconstitutional.[316] During the 21st century, public support for same-sex marriage has grown considerably,[317][318] and national polls conducted since 2011 show that a majority of Americans support legalizing it. On 17 May 2004, Massachusetts became the first U.S. state and the sixth jurisdiction in the world to legalize same-sex marriage following the Supreme Judicial Court's decision in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health six months earlier.[319]

Before the legalization of same-sex marriage in any U.S. jurisdiction, the U.S. Congress passed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in 1996, attempting to define marriage for the first time solely as a union between a man and a woman for all federal purposes, and allowing states to refuse to recognize such marriages created in other states.[320]

President Barack Obama announced on 9 May 2012, that "I think same-sex couples should be able to get married".[321][322][323] Obama also supported the full repeal of DOMA,[324] and called the state constitutional bans on same-sex marriage in California (2008)[325] and North Carolina (2012) unnecessary.[326] In 2011, the Obama Administration concluded that DOMA was unconstitutional and directed the U.S. Justice Department (DOJ) to stop defending the law in court.[327] Subsequently, Eric Cantor, Republican majority leader in the U.S. House of Representatives, announced that the House would defend DOMA. The law firm hired to represent the House soon withdrew from defending the law, requiring the House to retain replacement counsel.[328]

In the past two decades, public support for same-sex marriage has steadily increased,[61] and polls indicate that more than half of Americans support same-sex marriage.[61][329][330] Voters in Maine, Maryland and Washington approved same-sex marriage by referendum on 6 November 2012.[331]

On 26 June 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Windsor Section 3 of DOMA was unconstitutional for allowing the Federal Government of the United States to deny federal recognition of same-sex marriage licenses, if it is recognized or performed in a state that allows same-sex marriage.[332] Two years later on the same day, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that state level bans on same-sex marriage to be unconstitutional as well, legalizing same-sex marriage throughout the entire U.S. proper and all incorporated territories.[333]

On 6 October 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court denied review of five writ petitions from decisions of appellate courts finding constitutional right to same-sex marriage.[334] The immediate effect was to increase to 25 the number of states allowing same-sex marriage.[335]

On 26 June 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5–4 in Obergefell v. Hodges that states cannot prohibit the issuing of marriage licenses to same-sex couples, or deny recognition of lawfully performed out-of-state marriage licenses to same-sex couples. This ruling invalidated same-sex marriage bans in any U.S. State and certain territories.[336][337] Prior to this ruling, same-sex marriages were legally performed in 37 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, Guam as well as some Native American tribes.[338][339][340]

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg officiated at a same-sex wedding during the 2013 Labor Day weekend in what is believed to be a first for a member of the Supreme Court.[341][342]

A poll conducted in 2014 showed 59% of the American people supporting legal recognition for same-sex marriage.[343] This increased to 60% in 2015, and 61% in 2016: a record high.[344]

Uruguay

Uruguay's Chamber of Deputies passed a bill on 12 December 2012, to extend marriage rights to same-sex couples.[345] The Senate passed the bill on 2 April 2013, but with minor amendments. On 10 April 2013, the Chamber of Deputies passed the amended bill by a two-thirds majority (71–22). The president promulgated the law on 3 May 2013 and it took effect on 5 August.[346]

National debates

Armenia

Armenia has historically had few protections or recognition in law of same-sex couples. This changed in July 2017, when the Ministry of Justice revealed that all marriages performed abroad are valid in Armenia, including marriages between people of the same sex.[347] That makes Armenia the second country of the former Soviet Union, after Estonia, to recognise same-sex marriages performed abroad.

Austria

On 20 November 2013, the Greens introduced a bill in Parliament that would legalise same-sex marriage.[348] It was sent to the Judiciary Committee on 17 December 2013.[349] The bill was supposed to be debated in Autumn 2014,[350] but was delayed by the ruling coalition.

In December 2015, the Vienna Administrative Court dismissed a case challenging the same-sex marriage ban. The plaintiffs appealed to the Constitutional Court.[351] On 12 October 2017, the Constitutional Court agreed to consider one of the cases challenging the law barring same-sex marriage.[352][353][354] On 5 December 2017, the Constitutional Court struck down the ban on same-sex marriage as unconstitutional. If the Austrian Parliament does not amend the law, same-sex couples will be allowed to marry automatically by 1 January 2019.[355][356][357][358]

Chile

Michelle Bachelet, the President of Chile, who was elected to a second term in March 2014, has promised to work for the implementation of same-sex marriage and has a majority in both houses of Congress. Previously, she said, "Marriage equality, I believe we have to make it happen."[359] Polling shows majority support for same-sex marriage among Chileans.[360]

On 10 December 2014, a group of senators, from various parties, joined LGBT rights group MOVILH (Homosexual Movement of Integration and Liberation) in presenting a bill to allow same-sex marriage and adoption to Congress. MOVILH has been in talks with the Chilean Government to seek an amiable solution to the pending marriage lawsuit brought against the state before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. MOVILH has suggested that they would drop the case if Bachelet's Congress keeps their promise to legislate same-sex marriage.[361]

President Bachelet stated before a United Nations General Assembly panel in September 2016 that the Chilean Government would submit a same-sex marriage bill to Congress in the first half of 2017.[362] A same-sex marriage bill was finally submitted in September 2017.[363] On 28 January 2015, the National Congress approved a bill recognizing civil unions for same-sex and opposite-sex couples offering some of the rights of marriage. Bachelet signed the bill on 14 April, and it came into effect on 22 October.[364][365]

A poll carried out during September 2015 by the pollster Cadem Plaza Pública found that 60% of Chileans support same-sex marriage, whilst 36% are against it.[366]

China

The Marriage Law of the People's Republic of China explicitly defines marriage as the union between one man and one woman. No other form of civil union is recognized. The attitude of the Chinese Government towards homosexuality is believed to be "three nos": "No approval; no disapproval; no promotion." The Ministry of Health officially removed homosexuality from its list of mental illnesses in 2001.

Li Yinhe, a sociologist and sexologist well known in the Chinese gay community, has tried to legalize same-sex marriage several times, including during the National People's Congress in 2000 and 2004 (Legalization for Same-Sex Marriage 《中国同性婚姻合法化》 in 2000 and the Same-Sex Marriage Bill 《中国同性婚姻提案》 in 2004). According to Chinese law, 35 delegates' signatures are needed to make an issue a bill to be discussed in the Congress. Her efforts failed due to lack of support from the delegates. CPPCC National Committee spokesman Wu Jianmin when asked about Li Yinhe's proposal, said that same-sex marriage was still too "ahead of its time" for China. He argued that same-sex marriage was not recognized even in many Western countries, which are considered much more liberal in social issues than China.[367] This statement is understood as an implication that the Government may consider recognition of same-sex marriage in the long run, but not in the near future.

On 5 January 2016, a court in Changsha, southern Hunan Province, agreed to hear the lawsuit of 26-year-old Sun Wenlin filed in December 2015 against the Bureau of Civil Affairs of Furong District for its June 2015 refusal to let him marry his 36-year-old male partner, Hu Mingliang. On 13 April 2016, with hundreds of same-sex marriage supporters outside, the Changsha court ruled against Sun, who vowed to appeal, citing the importance of his case for LGBT progress in China.[368]

Costa Rica

On 19 March 2015, a bill to legalize same-sex marriage was introduced to the Legislative Assembly by Deputy Ligia Elena Fallas Rodríguez from the Broad Front.[369] On 10 December 2015, the organization Front for Equal Rights (Frente Por los Derechos Igualitarios) and a group of deputies presented another bill.[370][371][372]

On 10 February 2016, the Constitutional Court of Costa Rica announced it would hear a case seeking to legalize same-sex marriage in Costa Rica and declare the country's same-sex marriage ban unconstitutional.[373]

El Salvador

In August 2016, a lawyer in El Salvador filed a lawsuit before the country's Supreme Court asking for the nullification of Article 11 of the Family Code which defines marriage as a heterosexual union. Labeling the law as discriminatory and explaining the lack of gendered terms used in Article 34 of the Constitution’s summary of a marriage, the lawsuit seeks to allow same-sex couples the right to wed.[374] The Court dismissed the lawsuit in December 2016.[375] A second lawsuit was filed in November 2016.

Estonia

In October 2014, the Estonian Parliament approved a civil union law open to both opposite-sex and same-sex couples.[376]

In December 2016, the Tallinn Circuit Court ruled that same-sex marriages concluded in another country must be recognised as such in Estonia.[377]

Georgia

In 2016, a man filed a challenge against Georgia's same-sex marriage ban, arguing that while the Civil Code of Georgia states that marriage is explicitly between a man and a woman; the Constitution does not reference gender in its section on marriage.[378]

India

Same-sex marriage is not explicitly prohibited under Indian law and at least one couple has had their marriage recognised by the courts.[379]

In April 2014, Medha Patkar of the Aam Aadmi Party stated that her party supports the legalisation of same-sex marriage.[380]

Israel

Israel's High Court of Justice ruled to recognize foreign same-sex marriages for the limited purpose of registration with the Administration of Border Crossings, Population and Immigration, however this is merely for statistical purposes and grants no state-level rights; Israel does not recognize civil marriages performed under its own jurisdiction. A bill was raised in the Knesset (parliament) to rescind the High Court's ruling, but the Knesset has not advanced the bill since December 2006. A bill to legalize same-sex and interfaith civil marriages was defeated in the Knesset, 39–11, on 16 May 2012.[381]

In November 2015, the National LGBT Taskforce of Israel petitioned the Supreme Court of Israel to allow same-sex marriage in the country, arguing that the refusal of the rabbinical court to recognise same-sex marriage should not prevent civil courts from performing same-sex marriages. The court did not immediately rule against the validity of the petition.[382]

Italy

The cities of Bologna, Naples and Fano began recognizing same-sex marriages from other jurisdictions in July 2014,[383][384] followed by Empoli, Pordenone, Udine and Trieste in September,[385][386][387] and Florence, Piombino, Milan and Rome in October,[388][389] and by Bagheria in November.[390] Other cities that are considering similar laws include Cagliari, Livorno, Syracuse, Pompei and Treviso.[391]

A January 2013 Datamonitor poll found that 54.1% of respondents were in favour of same-sex marriage.[392] A May 2013 Ipsos poll found that 42% of Italians supported allowing same-sex couples to marry and adopt children.[393] An October 2014 Demos poll found that 55% of respondents were in favour of same-sex marriage, with 42% against.[394]

On 25 February 2016, the Italian Senate passed a bill allowing civil unions with 173 senators in favour and 73 against. That same bill was approved by the Chamber of Deputies on 11 May 2016 with 372 deputies in favour and 51 against.[395] The President of Italy signed the bill into law on 22 May 2016 and the law went into effect on 5 June 2016.

On 31 January 2017, the Italian Supreme Court of Cassation ruled that same-sex marriages performed abroad can be fully recognized by court order, when at least one of the two spouses is a citizen of a European Union country where same-sex marriage is legal,[396] thus making same-sex marriage de facto legal under certain circumstances.

Japan