History of Mumbai

This article's lead section may be too long. (June 2022) |

Indigenous tribals have inhabited Mumbai (Bombay) since the Stone Age.[citation needed] The Kolis and Aagri (a Marathi-Konkani people)[1] were the earliest known settlers of the islands. The Maurya Empire gained control of the islands during the 3rd century BCE and transformed them into a centre of Hindu-Buddhist culture and religion.[citation needed] Later, between the 2nd century BCE and 10th century CE, the islands came under the control of successive indigenous dynasties: the Satavahanas, Abhiras, Vakatakas, Kalachuris, Konkan Mauryas, Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, Silharas& Chollas.[citation needed]

Bhima of Mahikavati established a small kingdom in the area during the late 13th century, and brought settlers.[citation needed] The Delhi Sultanate captured the islands in 1348, and they were later passed to the Sultanate of Guzerat from 1391. The Treaty of Bassein (1534) between the Portuguese viceroy Nuno da Cunha and Bahadur Shah of Gujarat, placed the islands into Portuguese possession in 1534.

The islands suffered the Maratha Invasion of Goa and Bombay, and the Mughal invasions of Konkan (1685) towards the end of 17th century.[citation needed] During the English East India Company's rule in mid-18th century, it emerged as an important port city, having maritime trade contacts with Mecca, Basra etc.[citation needed] Economic development characterised British Bombay in the 19th century, the first-ever Indian railway line commenced operations between Bombay harbour and Taana city in 1853. Since the early 1900s, the city has also the home base of the Bollywood film industry. The city became a strong base for the Indian independence movement during the early 20th century, it was the centre of the Rowlatt Satyagraha of 1919 and Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946.[2] After India's independence in 1947, the territory of Bombay Presidency retained by India was restructured into Bombay State. The area of Bombay State increased, after several erstwhile princely states that joined the Indian union were integrated into Bombay State.

In 1960, following protests from the Samyukta Maharashtra movement, the city was incorporated into the newly created Maharashtra state from Bombay state. The Bombay metro area faced some unfortunate events like the inter-communal riots of 1992–93, while the 1993 Mumbai bombings caused extensive loss of life and property. Bombay was renamed Mumbai on 6 March 1996.[citation needed]

Early history

Prehistoric period

Geologists believe that the coast of western India came into being around 100 to 80 mya, after it broke away from Madagascar. Soon after its detachment, the peninsular region of the Indian plate drifted over the Réunion hotspot, a volcanic hotspot in the Earth's lithosphere near the island of Réunion. An eruption here some 66 mya is thought to have laid down the Deccan Traps, a vast bed of basalt lava that covers parts of central India. This volcanic activity resulted in the formation of basaltic outcrops, such as the Gilbert Hill, that are seen at various locations in the city. Further tectonic activity in the region led to the formation of hilly islands separated by a shallow sea.[3] Pleistocene sediments found near Kandivali in northern Mumbai by British archaeologist Malcolm Todd in 1939 indicate habitation since the Stone Age.[4] The present day city was built on what was originally an archipelago of seven islands of Mumbai Island, Parel, Mazagaon, Mahim, Colaba, Worli, and Old Woman's Island (also known as Little Colaba).[5] The islands were coalesced into a single landmass by the Hornby Vellard engineering project in 1784. By 1000 BCE, the region was heavily involved in seaborne commerce with Egypt and Persia.[6] The Koli fishing community had long inhabited the islands.[7] They were Dravidian in origin and included a large number of scattered tribes along the Vindhya Plateau, Gujarat, and Konkan. In Mumbai, there were three or four of these tribes. Their religious practices could be summed up as animism.[8]

Age of Dynastical Empires

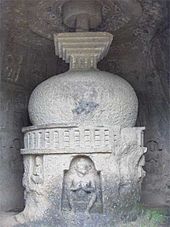

The islands were incorporated into the Maurya Empire under Emperor Ashoka of Magadha in the third century BCE. The empire's patronage made the islands a centre of Buddhist religion and culture.[6] Buddhist monks, scholars, and artists created the artwork, inscriptions, and sculpture of the Kanheri Caves in the mid third century BCE[9] and Mahakali Caves.[10] After the decline of the Maurya Empire around 185 BCE, these islands fell to the Satavahanas.[11] The port of Sopara (present-day Nala Sopara) was an important trading centre during the first century BCE,[12] with trade contacts with Rome.[13] The islands were known as Heptanesia (Ancient Greek: A Cluster of Seven Islands) to the Greek geographer Ptolemy in 150 CE.[14] After the end of the Satavahana rule in 250 CE, the Abhiras of Western Maharashtra and Vakatakas of Vidarbha held dominion over the islands. The Abhiras ruled for 167 years, till around 417 CE.[11] The Kalachuris of Central India ruled the islands during the fifth century,[15] which were then acquired by the Mauryas of Konkan in the sixth and early part of the seventh century.[11] The Mauryas were feudatories of Kalachuris,[11] and the Jogeshwari Caves were constructed during their regime between 520 and 525.[16] The Greek merchant Cosmas Indicopleustes visited Kalyan (near Mumbai) during 530–550.[17] The Elephanta Caves also dates back to the sixth century.[18] Christianity arrived in the islands during the sixth century, when the Nestorian Church made its presence in India.[19] The Mauryan presence ended when the Chalukyas of Badami in Karnataka under Pulakeshin II invaded the islands in 610.[20] Dantidurga of the Rashtrakuta Dynasty of Karnataka conquered the islands during 749–750.[11]

The Silhara dynasty of Konkan ruled the region between 810 and 1260.[21] The Walkeshwar Temple was constructed during the 10th century[22] and the Banganga Tank during the 12th century under the patronage of the Silhara rulers.[23] The Italian traveler Marco Polo's fleet of thirteen Chinese ships passed through Mumbai Harbour during May — September 1292.[17][24] King Bhimdev founded his kingdom in the region in the late 13th century[25] and established his capital in Mahikawati (present day Mahim).[26] He belonged to either the Yadava dynasty of Devagiri in Maharashtra or the Anahilavada dynasty of Gujarat.[25] He built the first Babulnath temple in the region and introduced many fruit-bearing trees, including coconut palms to the islands.[27] The Pathare Prabhus, one of the earliest settlers of the city, were brought to Mahim from Patan and other parts of Saurashtra in Gujarat around 1298 by Bhimdev during his reign.[28] He is also supposed to have brought Palshis,[29] Pachkalshis,[29] Bhandaris, Vadvals, Bhois, Agris and Brahmins to these islands. After his death in 1303, he was succeeded by his son Pratapbimba, who built his capital at Marol in Salsette, which he named Pratappur. The islands were wrested from Pratapbimba's control by Mubarak Khan, a self-proclaimed regent of the Khalji dynasty, who occupied Mahim and Salsette in 1318. Pratapbimba later reconquered the islands which he ruled till 1331. Later, his brother-in-law Nagardev for 17 years till 1348. The islands came under the control of the Muslim rulers of Gujarat in 1348, ending the sovereignty of Hindu rulers over the islands.[11]

Islamic period

The islands were under Muslim rule from 1348 to 1391. After the establishment of the Gujarat Sultanate in 1391, Muzaffar Shah I was appointed viceroy of north Konkan.[30] For the administration of the islands, he appointed a governor for Mahim. During the reign of Ahmad Shah I (1411–1443), Malik-us-Sharq was appointed governor of Mahim, and in addition to instituting a proper survey of the islands, he improved the existing revenue system of the islands. During the early 15th century, the Bhandaris seized the island of Mahim from the Sultanate and ruled it for eight years.[31] It was reconquered by Rai Qutb of the Gujarat Sultanate.[32] Firishta, a Persian historian, recorded that by 1429 the seat of government of the Gujarat Sultanate in north Konkan had transferred from Thane to Mahim.[33] On Rai Qutb's death in 1429–1430, Ahmad Shah I Wali of the Bahmani Sultanate of Deccan captured Salsette and Mahim.[34][35]

Ahmad Shah I retaliated by sending his son Jafar Khan to recapture the lost territory. Jafar emerged victorious in the battle fought with Ahmad Shah I Wali. In 1431, Mahim was recaptured by the Sultanate of Gujarat.[35] The Sultanate's patronage led to the construction of many mosques, prominent being the Haji Ali Dargah in Mahim, built in honour the Muslim saint Haji Ali in 1431.[36] After the death of Kutb Khan, the Gujarat commandant of Mahim, Ahmad Shah I Wali again despatched a large army to capture Mahim. Ahmad Shah I responded with a large army and navy under Jafar Khan leading to the defeat of Ahmad Shah I Wali.[37] During 1491–1494, the islands suffered sea piracies from Bahadur Khan Gilani, a nobleman of the Bahamani Sultanate.[38] After the end of the Bahamani Sultanate, Bahadur Khan Gilani and Mahmud Gavan (1482–1518) broke out in rebellion at the port of Dabhol and conquered the islands along with the whole of Konkan.[32][39][40] Portuguese explorer Francisco de Almeida's ship sailed into the deep natural harbour of the island in 1508, and he called it Bom baía (Good Bay).[41] However, the Portuguese paid their first visit to the islands on 21 January 1509, when they landed at Mahim after capturing a Gujarat barge in the Mahim creek.[5] After a series of attacks by the Gujarat Sultanate, the islands were recaptured by Sultan Bahadur Shah.[32]

In 1526, the Portuguese established their factory at Bassein.[42] During 1528–29, Lopo Vaz de Sampaio seized the fort of Mahim from the Gujarat Sultanate, when the King was at war with Nizam-ul-mulk, the emperor of Chaul, a town south of the islands.[43][44][45] Bahadur Shah had grown apprehensive of the power of the Mughal emperor Humayun and he was obliged to sign the Treaty of Bassein with the Portuguese on 23 December 1534. According to the treaty, the islands of Mumbai and Bassein were offered to the Portuguese.[46] Bassein and the seven islands were surrendered later by a treaty of peace and commerce between Bahadur Shah and Nuno da Cunha, Viceroy of Portuguese India, on 25 October 1535, ending the Islamic rule in Mumbai.[45]

Portuguese period

The Portuguese were actively involved in the foundation and growth of their religious orders in Bombay. The islands were leased to Mestre Diogo in 1534.[47] The San Miguel (St. Michael Church) in Mahim, one of the oldest churches in Bombay, was built by the Portuguese in 1540.[48] Parel, Wadala, Sion, and Worli were granted to Manuel Serrão between 1545 and 1548, during the viceroyalty of João de Castro. Mazagaon was granted to Antonio Pessoa in 1547.[49] Salsette was granted for three years to João Rodrigues Dantas, Cosme Corres, and Manuel Corres. Trombay and Chembur were granted to Dom Roque Tello de Menezes, and the Island of Pory (Elephanta Island) to João Pirez in 1548.[50] Garcia de Orta, a Portuguese physician and botanist, was granted the possession of Bombay in 1554 by viceroy Pedro Mascarenhas.[51]

The Portuguese encouraged intermarriage with the local population, and strongly supported the Roman Catholic Church.[52] In 1560, they started proselytising the local Koli, Kunbi, Kumbhar population in Mahim, Worli, and Bassein.[53] These Christians were referred to by the British as Portuguese Christians, though they were Nestorian Christians who had only recently established ties with the Roman Catholic Church.[54] During this time, Bombay's main trade was coconuts and coir.[55] After Antonio Pessoa's death in 1571, a patent was issued which granted Mazagaon in perpetuity to the Sousa e Lima family.[49] The St. Andrew Church at Bandra was built in 1575.[56]

The annexation of Portugal by Spain in 1580 opened the way for other European powers to follow the spice routes to India. The Dutch arrived first, closely followed by the British.[57] The first English merchants arrived in Bombay in November 1583, and travelled through Bassein, Thane, and Chaul.[58] The Portuguese Franciscans had obtained practical control of Salsette and Mahim by 1585, and built Nossa Senhora de Bom Concelho (Our Lady of Good Counsel) at Sion and Nossa Senhora de Salvação (Our Lady of Salvation) at Dadar in 1596. The Battle of Swally was fought between the British and the Portuguese at Surat in 1612 for the possession of Bombay.[45] Dorabji Nanabhoy, a trader, was the first Parsi to settle in Bombay in 1640. Castella de Aguada (Fort of the Waterpoint) was built by the Portuguese at Bandra in 1640 as a watchtower overlooking the Mahim Bay, the Arabian Sea and the southern island of Mahim.[59] The growing power of the Dutch by the middle of the seventeenth century forced the Surat Council of the British Empire to acquire Bombay from King John IV of Portugal in 1659.[45] The marriage treaty of Charles II of England and Catherine of Portugal on 8 May 1661 placed Bombay in British possession as a part of Catherine's dowry to Charles.[60]

British period

Struggle with native powers

On 19 March 1662, Abraham Shipman was appointed the first Governor and General of the city, and his fleet arrived in Bombay in September and October 1662. On being asked to hand over Bombay and Salsette to the English, the Portuguese Governor contended that the island of Bombay alone had been ceded, and alleging irregularity in the patent, he refused to give up even Bombay. The Portuguese Viceroy declined to interfere and Shipman was prevented from landing in Bombay. He was forced to retire to the island of Anjediva in North Canara and died there in October 1664. In November 1664, Shipman's successor Humphrey Cooke agreed to accept Bombay without its dependencies.[61][62] However, Salsette, Mazagaon, Parel, Worli, Sion, Dharavi, and Wadala still remained under Portuguese possession. Later, Cooke managed to acquire Mahim, Sion, Dharavi, and Wadala for the English.[63] On 21 September 1668, the Royal Charter of 27 March 1668, led to the transfer of Bombay from Charles II to the English East India Company for an annual rent of £10 (equivalent retail price index of £1,226 in 2007) or Indian Rs 1,48,000 today.[64][65] The Company immediately set about the task of opening up the islands by constructing a quay and warehouses.[66] A customs house was also built.[67] Fortifications were built around Bombay Castle. A Judge-Advocate was appointed for the purpose of civil administration.[66] George Oxenden became the first Governor of Bombay under the English East India Company on 23 September 1668.[67] Gerald Aungier, who was appointed Governor of Bombay in July 1669, established the first mint in Bombay in 1670.[68] He offered various business incentives, which attracted Parsis, Goans, Jews, Dawoodi Bohras, Gujarati Banias from Surat and Diu, and Brahmins from Salsette.[69] He also planned extensive fortifications in the city from Dongri in the north to Mendham's Point (near present-day Lion Gate) in the south.[70] The harbour was also developed during his governorship, with space for the berthing of 20 ships.[55] In 1670, the Parsi businessman Bhimjee Parikh imported the first printing press into Bombay.[71] Between 1661 and 1675 there was a sixfold increase in population from 10,000 to 60,000.[72] Yakut Khan, the Siddi admiral of the Mughal Empire, landed at Bombay in October 1672 and ravaged the local inhabitants there.[73] On 20 February 1673, Rickloffe van Goen, the Governor-General of Dutch India attacked Bombay, but the attack was resisted by Aungier.[74] On 10 October 1673, the Siddi admiral Sambal entered Bombay and destroyed the Pen and Nagothana rivers, which were very important for the English and the Maratha King Shivaji.[73] The Treaty of Westminster concluded between England and the Netherlands in 1674, relieved the British settlements in Bombay of further apprehension from the Dutch.[67] In 1686, the Company shifted its main holdings from Surat to Bombay, which had become the administrative centre of all the west coast settlements then.[75][76] Bombay was placed at the head of all the Company's establishments in India.[77]

Yakut Khan landed at Sewri on 14 February 1689,[78] and razed the Mazagon Fort in June 1690.[79] After a payment made by the British to Aurangzeb, the ruler of the Mughal Empire, Yakut evacuated Bombay on 8 June 1690.[80] The arrival of many Indian and British merchants led to the development of Bombay's trade by the end of the seventeenth century. Soon it was trading in salt, rice, ivory, cloth, lead and sword blades with many Indian ports as well as with the Arabian cities of Mecca and Basra.[55] By 1710, the construction of Bombay Castle was finished, which fortified the islands from sea attacks by European pirates and the Marathas.[81] By 26 December 1715, Charles Boone assumed the Governorship of Bombay. He implemented Aungier's plans for the fortification of the island, and had walls built from Dongri in the north to Mendham's point in the south.[55] He established the Marine force,[55] and constructed the St. Thomas Cathedral in 1718, which was the first Anglican Church in Bombay.[82] In 1728, a Mayor's court was established in Bombay and the first reclamation was started which was a temporary work in Mahalaxmi, on the creek separating Bombay from Worli.[55] The shipbuilding industry started in Bombay in 1735[83] and soon the Naval Dockyard was established in the same year.[84]

In 1737, Salsette was captured from the Portuguese by Maratha Baji Rao I and the province of Bassein was ceded in 1739.[85] The Maratha victory forced the British to push settlements within the fort walls of the city. Under new building rules set up in 1748, many houses were demolished and the population was redistributed, partially on newly reclaimed land.[86] Lovji Nusserwanjee Wadia, a member of the Wadia family of shipwrights and naval architects from Surat, built the Bombay Dock in 1750,[87] which was the first dry dock to be commissioned in Asia.[84] By the middle of the eighteenth century, Bombay began to grow into a major trading town and soon Bhandaris from Chaul in Maharashtra, Vanjaris from the Western Ghat mountain ranges of Maharashtra, Africans from Madagascar, Bhatias from Rajasthan, Vaishya Vanis, Goud Saraswat Brahmins, Daivajnas from konkan, ironsmiths and weavers from Gujarat migrated to the islands.[88] In 1769, Fort George was built on the site of the Dongri Fort[89] and in 1770, the Mazagaon docks were built.[90] The British occupied Salsette, Elephanta, Hog Island, and Karanja on 28 December 1774.[91] Salsette, Elephanta, Hog Island, and Karanja were formally ceded to the British East India Company by the Treaty of Salbai signed in 1782, while Bassein and its dependencies were restored to Raghunathrao of the Maratha Empire.[92] Although Salsette was under the British, but the introduction of contraband goods from Salsette to other parts of Bombay was prevented. The goods were subjected to Maratha regulations with respect to taxes and a 30% toll was levied on all goods into the city from Salsette.[93]

In 1782, William Hornby assumed the office of Governor of Bombay, and initiated the Hornby Vellard engineering project of uniting the seven islands into a single landmass. The purpose of this project was to block the Worli creek and prevent the low-lying areas of Bombay from being flooded at high tide.[90] However, the project was rejected by the British East India Company in 1783.[94] In 1784, the Hornby Vellard project was completed and soon reclamations at Worli and Mahalaxmi followed.[95] The history of journalism in Bombay commenced with publication of the Bombay Herald in 1789 and the Bombay Courier in 1790.[96] In 1795, the Maratha army defeated the Nizam of Hyderabad. Following this, many artisans and construction workers from Andhra Pradesh migrated to Bombay and settled into the flats which were constructed by the Hornby Vellard. These workers were called Kamathis, and their enclave was called Kamathipura.[97] The construction of the Sion Causeway (Duncan Causeway) commenced in 1798.[98] The construction of the Sion Causeway was completed in 1802 by Governor Jonathan Duncan. It connected Bombay Island to Kurla in Salsette.[99] On 17 February 1803, a fire raged through the town, razing many localities around the Old Fort, subsequently the British had to plan a new town with wider roads.[100] In May 1804, Bombay was hit by a severe famine, which led to a large-scale emigration.[67] On 5 November 1817, the British East India Company under Mountstuart Elphinstone[101] defeated Bajirao II, the Peshwa of the Maratha Empire, in the Battle of Kirkee which took place on the Deccan Plateau.[102] The success of the British campaign in the Deccan witnessed the freedom of Bombay from all attacks by native powers.[67]

City development

The educational and economic progress of the city began with the Company's military successes in the Deccan. The Wellington Pier (Apollo Bunder) in the north of Colaba was opened for passenger traffic in 1819 and the Elphinstone High School was established in 1822. Bombay was hit by a drought in 1824. The construction of the new mint commenced in 1825.[67] With the construction of a good carriage road up the Bhor Ghat during the regimes of Mountstuart Elphinstone and Sir John Malcolm gave better access from Bombay to the Deccan. This road, which was opened on 10 November 1830, facilitated trade in a large measure.[103] By 1830, regular communication with England started by steamers navigating the Red and Mediterranean Sea.[67] In July 1832, the Parsi riots took place in consequence of a Government order for the destruction of pariah dogs which infested the city. The Asiatic Society of Bombay (Town Hall) was completed in 1833,[67][104] and the Elphinstone College was built in 1835.[105] In 1836, the Chamber of Commerce was established.[67]

In 1838, the islands of Colaba and Little Colaba were connected to Bombay by the Colaba Causeway.[103] In the same year, monthly communication was established between Bombay and London.[67] The Bank of Bombay, the oldest bank in the city, was established in 1840,[106] and the Bank of Western India in 1842.[107] The Cotton Exchange was established in Cotton Green in 1844. Avabai Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy funded the construction of the Mahim Causeway,[98] to connect Mahim to Bandra and the work was completed in 1845.[108] The Commercial Bank of India, established in 1845, issued exotic notes with an interblend of Western and Eastern Motifs.[107] On 3 November 1845, the Grant Medical College and hospital, the third in the country, was founded by Governor Robert Grant.[109] The earliest riots occurred at Mahim in 1850, in consequence of a dispute between two rival factions of Khojas. Riots broke out between Muslims and Parsis in October 1851, in consequence of an article on Muhammad which appeared in the Chitra Gnyan Darpan newspaper.[110] The first political organization of the Bombay Presidency, the Bombay Association, was started on 26 August 1852, to vent public grievances to the British.[111] The first-ever Indian railway line began operations between Bombay and neighbouring Thane over a distance of 21 miles on 16 April 1853.[112] The Bombay Spinning and Weaving Company was the first cotton mill to be established in the city on 7 July 1854 at Tardeo in Central Bombay.[113] The Bombay, Baroda, and Central India Railway (BB&CI) was incorporated in 1855.[114]

The University of Bombay was the first modern institution of higher education to be established in India in 1857.[115] The Commercial Bank, the Chartered Mercantile, the Agra and United Service, the Chartered and the Central Bank of Western India were established in Bombay attracting a considerable industrial population.[116] The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 increased the demand for cotton in the West, and led to an enormous increase in cotton-trade.[117] The Victoria Gardens was opened to the public in 1862.[118] The Bombay Shipping and Iron Shipping Companies were started in 1863 to make Bombay merchants independent of the English.[67] The Bombay Coast and River Steam Navigation Company was established in 1866 for the maintenance of steam ferries between Bombay and the nearby islands;[67] while the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 revolutionized the marine trade of Bombay.[103] The Bombay Municipal Corporation was established in 1872, providing a modern framework of governance for the rapidly growing city.[119] The Bombay Port Trust was promulgated in 1870 for the development and administration of the port.[120] Tramway communication was instituted in 1873.[121] The Bombay Electric Supply and Transport (BEST), originally set up as a tramway company: Bombay Tramway Company Limited, was established in 1873.[122] Violent Parsi-Muslim riots again broke out in February 1874, which were caused by an article on Muhammad published by a Parsi resident.[110] The Bombay Gymkhana was formed in 1875.[123] The Bombay Stock Exchange, the oldest stock exchange in Asia, was established in 1875.[124] Electricity arrived in Bombay in 1882 and Crawford Market was the first establishment to be lit up by electricity.[125] The Bombay Natural History Society was founded in 1883.[126] Bombay Time, one of the two official time zones in British India, was established in 1884[127] during the International Meridian Conference held at Washington, D.C in the United States.[128] Bombay time was set at 4 hours and 51 minutes ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) using the 75th east meridian.[127] The Princess Dock was built in 1885 as part of a scheme for improving the whole foreshore of the Bombay harbour. The first institute in Asia to provide Veterinary Education, the Bombay Veterinary College, was established in Parel in Bombay in the year 1886.

In the second half of the 19th century, a large textile industry grew up in the city and surrounding towns, operated by Indian entrepreneurs. Simultaneously a labour movement was organized. Starting with the Factory Act of 1881, state government played an increasingly important role in regulating the industry. The Bombay presidency set up a factory inspection commission in 1884. There were restrictions on the hours of children and women. An important reformer was Mary Carpenter, who wrote factory laws that exemplified Victorian modernization theory of the modern, regulated factory as vehicle of pedagogy and civilizational uplift. Laws provided for compensation for workplace accidents.[129]

Indian freedom movement

The growth of political consciousness started after the establishment of the Bombay Presidency Association on 31 January 1885.[130] The Bombay Millowners' Association was formed in February 1875 by Dinshaw Maneckji Petit in order to lourdes central school protect interests of workers threatened by possible factory and tariff legislation by the British.[131] The first session of the Indian National Congress was held in Bombay from 28–31 December 1885.[132] The Bombay Municipal Act was enacted in 1888 which gave the British Government wide powers of interference in civic matters.[133] The Victoria Terminus of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway, one of the finest stations in the world, was completed in May 1888.[134] The concept of Dabbawalas (lunch box delivery man) originated in the 1890s when British people who came to Bombay did not like the local food. So the Dabbawala service was set up to bring lunch to these people in their workplace straight from their home.[135] On 11 August 1893, a serious communal riot took place between the Hindus and Muslims, when a Shiva temple was attacked by Muslims in Bombay. 75 people were killed and 350 were injured.[136] In September 1896, Bombay was hit by a bubonic plague epidemic where the death toll was estimated at 1,900 people per week.[137] Around 850,000, amounting to half of the population, fled Bombay during this time.[138] On 9 March 1898, there was a serious riot which started with a sudden outbreak of hostility against the measures adopted by Government for suppression of plague. The riot led to a strike of dock and railway workers which paralysed the city for a few days.[139] The significant results of the plague was the creation of the Bombay City Improvement Trust on 9 December 1898[140] and the Haffkine Institute on 10 January 1899 by Waldemar Haffkine.[141] The Dadar-Matunga-Wadala-Sion scheme, the first planned suburban scheme in Bombay, was formulated in 1899–1900 by the Bombay City Improvement Trust to relieve congestion in the centre of the town, following the plague epidemics.[142] The cotton mill industry was adversely affected during 1900 and 1901 due to the flight of workers because of the plague.[143]

The Partition of Bengal in 1905 initiated the Swadeshi movement, which led to the boycotting of British goods in India.[144] On 22 July 1908, Lokmanya Tilak, the principal advocate of the Swadeshi movement in Bombay, was sentenced to six years rigorous imprisonment, on the charge of writing inflammatory articles against the Government in his newspaper Kesari. The arrest led to huge scale protests across the city.[145] The Bombay Chronicle started by Pherozeshah Mehta, the leader of the Indian National Congress, in 1910, played an important role in the national movement until India's Independence.[146] Lord Willingdon convened the Provincial War Conference at Bombay on 10 June 1918, whose objective was to seek the co-operation of the people in the World War I measures which the British Government thought it necessary to take in the Bombay Presidency. The conference was followed by huge rallies across the city. The worldwide influenza epidemic raged through Bombay from September to December 1918, causing hundreds of deaths per day. The Lord Willingdon Memorial incident of December 1918 saw the handicap of Home Rulers in Bombay. The first important strike in the textile industry in Bombay began in January 1919.[147] Bombay was the main centre of the Rowlatt Satyagraha movement started by Mahatma Gandhi from February — April 1919. The movement was started as a result of the Rowlatt Act, which indefinitely extended emergency measures during World War I in order to control public unrest.[148]

Following World War I, which saw large movement of India troops, supplies, arms and industrial goods to and from Bombay, the city life was shut down many times during the Non-cooperation movement from 1920 to 1922.[149] In 1926, the Back Bay scandal occurred, when the Bombay Development Department under the British reclaimed the Back Bay area in Bombay after the financial crisis incidental to the post-war slump in the city.[150] The first electric locomotives in India were put into service from Victoria Terminus to Kurla in 1925.[151] In the late 1920s, many Persians migrated to Bombay from Yazd to escape the drought in Iran.[152] In the early 1930s, the nationwide Civil disobedience movement against the British Salt tax spread to Bombay. Vile Parle was the headquarters of the movement[153] in Bombay under Jamnalal Bajaj.[154] On 15 October 1932 industrialist and aviator J.R.D. Tata pioneered civil aviation in Bombay by flying a plane from Karachi to Bombay.[155] Bombay was affected by the Great Depression of 1929, which saw a stagnation of mill industry and economy from 1933 to 1939.[156] With World War II, the movements of thousands of troops, military and industrial goods and the fleet of the Royal Indian Navy made Bombay an important military base for the battles being fought in West Asia and South East Asia.[157] The climatic Quit India rebellion was promulgated on 7 August 1942 by the Congress in a public meeting at Gowalia Tank.[158] The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 18 February 1946 in Bombay marked the first and most serious revolt by the Indian sailors of the Royal Indian Navy against British rule.[159] On 15 August 1947, finally India was declared independent. The last British troops to leave India, the First Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry, passed through the arcade of the Gateway of India in Bombay on 28 February 1948,[160] ending the 282-year-long period of the British in Bombay .[161]

Independent India

20th century

After the Partition of India on 15 August 1947, over 100,000 Sindhi refugees from the newly created Pakistan were relocated in the military camps five kilometres from Kalyan in the Maharashta Region. It was converted into a township in 1949, and named Ulhasnagar by the then Governor-General of India, C. Rajagopalachari.[162] In April 1950, Greater Bombay District came into existence with the merger of Bombay Suburbs and Bombay City. It spanned an area of 235.1 km2 (90.77 sq mi) and inhabited 2,339,000 of people in 1951. The Municipal Corporation limits were extended up to Jogeshwari along the Western Railway and Bhandup along the Central Railway. This limit was further extended in February 1957 up to Dahisar along the Western Railway and Mulund on the Central Railway.[163] In the 1955 Lok Sabha discussions, when Bombay State was being re-organised along linguistic lines into the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat.[164] But the States Reorganisation Committee recommended a bi-lingual state for Maharashtra-Gujarat, with Bombay as its capital. However, the Samyukta Maharashtra movement opposed this, and insisted that Bombay native of Marathi be declared the capital of Maharashtra.[165] The Indian Institute of Technology Bombay was established in 1958 at Powai, a northern suburb of Bombay.[166] Following protests by the Samyukta Maharashtra movement in which 105 people were killed by police firing, Maharashtra State was formed with Bombay as its capital on 1 May 1960.[167] Flora Fountain was renamed Hutatma Chowk ("Martyr's Square") as a memorial to the Samyukta Maharashtra movement.[168][169]

In the early 1960s, the Parsi and Marwaris Migrant communities owned majority of the industry and trade enterprises in the city, while the white-collar jobs were mainly sought by the South Indian migrants to the city. The Shiv Sena party was established on 19 June 1966 by Bombay cartoonist Bal Thackeray, out of a feeling of resentment about the relative marginalization of the native Marathi people in their native state Maharashtra. In the 1960s and 1970s, Shiv Sena fought for rights of native Marathis.[170] In the late 1960s, Nariman Point and Cuffe Parade were reclaimed and developed.[171] During the 1970 there were Bombay-Bhiwandi riots.[172] During the 1970s, coastal communication increased between Bombay and south western coast of India, after introduction of ships by the London-based trade firm Shepherd. These ships facilitated the entry of Goan and Mangalorean Catholics to Bombay.[173]

Nehru Centre was established in 1972 at Worli in Bombay.[174] The Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) was set up on 26 January 1975 by the Government of Maharashtra as an apex body for planning and co-ordination of development activities in the Mumbai metropolitan region.[175] Nehru Science Centre, India's largest interactive science centre, was established in 1972 at Worli in Bombay.[176] In August 1979, a sister township of Navi Mumbai was founded by City and Industrial Development Corporation (CIDCO) across Thane and Raigad districts of Maharashtra to help the dispersal and control of Mumbai's population.[177] The Great Bombay Textile Strike was called on 18 January 1982 by trade union leader Dutta Samant, where nearly 250,000 workers and more than 50 textile mills in Bombay went on strike.[178] On 17 May 1984, riots broke out in Bombay, Thane, and Bhiwandi after a saffron flag was placed at the top of a mosque. 278 were killed and 1,118 were wounded.[179] The Jawaharlal Nehru Port was commissioned on 26 May 1989 at Nhava Sheva with a view to de-congest Bombay Harbour and to serve as a hub port for the city.[180] In December 1992 – January 93, over 1,000 people were killed and the city paralyzed by communal riots between the Hindus and the Muslims caused by the destruction of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya.[181] A series of 13 co-ordinated bomb explosions took place in Bombay on 12 March 1993, which resulted in 257 deaths and 700 injuries.[182] The attacks were believed to be orchestrated by mafia don Dawood Ibrahim in retaliation for the Babri Mosque demolition.[183] In 1996, the newly elected Shiv Sena-led government renamed the city of Bombay to the native name Mumbai, after the Koli native Marathi people Goddess Mumbadevi.[184][185] Soon colonial British names were shed to assert or reassert local names,[186] such as Victoria Terminus being renamed to Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus on 4 March 1996, after the 17th century Marathi King Shivaji.[187]

21st century

During the 21st century, the city suffered several bombings. On 6 December 2002, a bomb placed under a seat of an empty BEST (Brihanmumbai Electric Supply and Transport) bus exploded near Ghatkopar station in Mumbai. Around 2 people were killed and 28 were injured.[188] The bombing occurred on the tenth anniversary of the demolition of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya.[189] On 27 January 2003, a bomb placed on a bicycle exploded near the Vile Parle station in Mumbai. The bomb killed 1 and injured 25. The blast occurred a day ahead of the visit of Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the then Prime Minister of India to the city.[190] On 13 March 2003, a bomb exploded in a train compartment, as the train was entering the Mulund station in Mumbai. 10 people were killed and 70 were injured. The blast occurred a day after the tenth anniversary of the 1993 Bombay bombings.[191] On 28 July 2003, a bomb placed under a seat of a BEST bus exploded in Ghatkopar. The bomb killed 4 people and injured 32.[192] On 25 August 2003, two blasts in South Mumbai – one near the Gateway of India and the other at Zaveri Bazaar in Kalbadevi occurred. At least 44 people were killed and 150 injured. No group claimed responsibility for the attack, but it had been hinted that the Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Toiba was behind the attacks.[193]

Mumbai was lashed by torrential rains on 26–27 July 2005, during which the city was brought to a complete standstill. The city received 37 inches (940 millimeters) of rain in 24 hours — the most any Indian city has ever received in a single day. Around 83 people were killed.[194] On 11 July 2006, a series of seven bomb blasts took place over a period of 11 minutes on the Suburban Railway in Mumbai at Khar, Mahim, Matunga, Jogeshwari, Borivali, and one between Khar and Santa Cruz.[195] 209 people were killed[196] and over 700 were injured.[197] According to Mumbai Police, the bombings were carried out by Lashkar-e-Toiba and Students Islamic Movement of India (SIMI).[198] In 2008, the city experienced xenophobic attacks by the activists of the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) under Raj Thackeray on the North Indian migrants in Mumbai.[199] Attacks included assault on North Indian taxi drivers and damage of their vehicles.[200] There were a series of ten coordinated terrorist attacks by 10 armed Pakistani men using automatic weapons and grenades which began on 26 November 2008 and ended on 29 November 2008. The attacks resulted in 164 deaths, 308 injuries, and severe damage to several important buildings.[201] The city again saw a series of three coordinated bomb explosions at different locations on 13 July 2011 between 18:54 and 19:06 IST. The blasts occurred at the Opera House, Zaveri Bazaar, and Dadar,[202] which left 26 killed, and 130 injured.[203][204] The city's Wankhede Stadium was the venue for 2011 Cricket World Cup final, where India emerged as a champion for the second time after the 1983 Cricket World Cup.

See also

- Bombay Before the British

- Growth of Mumbai

- Mumbai bombings

- List of forts in Mumbai

- List of governors of Bombay Presidency

- Timeline of Mumbai events

Notes

- ^ "NIRC". Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ "Bombay: History of a City". British Library. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ Greater Mumbai District Gazetteer 1986, Geology

- ^ Ghosh 1990, p. 25

- ^ a b Greater Mumbai District Gazetteer 1986, Geography

- ^ a b Ring, Salkin & Boda 1994, p. 142

- ^ Shubhangi Khapre (19 May 2008). "Of age-old beliefs and practices". Daily News & Analysis. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 40

- ^ "Kanheri Caves". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ Abhilash Gaur (24 January 2004). "Pay dirt: Treasure amidst Mumbai's trash". The Tribune. India. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Greater Mumbai District Gazetteer 1986, Ancient Period

- ^ Thana — Places of Interest 2000, Sopara

- ^ "Dock around the clock". Time Out Mumbai (6). 14 November 2008. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 23

- ^ David 1973, p. 11

- ^ "The Slum and the Sacred Cave" (PDF). Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory (Columbia University). p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ a b Da Cunha 1993, p. 184

- ^ "World Heritage Sites — Elephanta Caves". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ Lhendup Gyatso Bhutia (14 September 2008). "Message in a bottle". Daily News & Analysis. Archived from the original on 19 September 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ David 1973, p. 12

- ^ Nairne 1988, p. 15

- ^ Dwivedi, Sharada (26 September 2007). "The Legends of Walkeshwar". Mumbai Newsline. Express Group. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ Agarwal, Lekha (2 June 2007). "What about Gateway of India, Banganga Tank?". Mumbai Newsline. Express Group. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ Thana District Gazetteer 1986, Early History

- ^ a b Da Cunha 1993, p. 34

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 36

- ^ O'Brien 2003, p. 3

- ^ Singh et al. 2004, p. 1703

- ^ a b Da Cunha 1993, p. 42

- ^ Prinsep, Thomas & Henry 1858, p. 315

- ^ Edwardes 1902, p. 54

- ^ a b c Greater Mumbai District Gazetteer 1986, Muhammedan Period

- ^ Greater Mumbai District Gazetteer 1986, Mediaeval Period

- ^ Misra 1982, p. 193

- ^ a b Misra 1982, p. 222

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 77

- ^ Edwardes 1902, p. 55

- ^ Edwardes 1902, p. 57

- ^ Subrahmanyam 1997, p. 110

- ^ Subrahmanyam 1997, p. 111

- ^ "The West turns East". Hindustan Times. India. Retrieved 12 August 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Maharashtra State Gazetteer 1977, p. 153

- ^ Edwardes 1993, p. 65

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 74

- ^ a b c d Greater Mumbai District Gazetteer 1986, Portuguese Period

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 88

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 97

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Churches

- ^ a b Burnell 2007, p. 15

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 96

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 100

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 283

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 183

- ^ Baptista 1967, p. 25

- ^ a b c d e f Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 26

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, St. Andrews Church

- ^ Leonard 2006, p. 359

- ^ "The First Englishmen in Bombay". Department of Theoretical Physics (Tata Institute of Fundamental Research). Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ Ball, Iain (19 March 2003). "Local 'army' offers to protect Bombay's 'Castella'". Bombay Newsline. Express Group. Archived from the original on 24 July 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ "Catherine of Bragança (1638–1705)". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 April 2008. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- ^ Thana District Gazetteer 1986, Portuguese (1500–1670)

- ^ Malabari 1910, p. 98

- ^ Malabari 1910, p. 99

- ^ "12-Amazing Facts About Mumbai". Dozenfacts. 26 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Da Cunha 1993, p. 272

- ^ a b Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 20

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, British Period

- ^ David 1973, p. 135

- ^ Murray 2007, p. 79

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 17

- ^ Shroff 2001, p. 169

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 31

- ^ a b Yimene 2004, p. 94

- ^ Colin C.Ganley (2007). "Security, the central component of an early modern institutional matrix; 17th century Bombay's Economic Growth" (PDF). International Society for New Institutional Economics (ISNIE): 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ R. K. Kochhar (25 June 1994). "Shipbuilding at Bombay" (PDF, 297 KB). Current Science. 12. 66. Indian Academy of Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ^ Carsten 1961, p. 427

- ^ Hughes 1863, p. 227

- ^ Anderson 1854, p. 115

- ^ Nandgaonkar, Satish (22 March 2003). "Mazgaon fort was blown to pieces – 313 years ago". The Indian Express. India: Express Group. Archived from the original on 12 April 2003. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ Anderson 1854, p. 116

- ^ "Bombay Castle". Governor of Maharashtra. Archived from the original on 23 September 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, St. Thomas Cathedral

- ^ Mehta 1940, p. 16

- ^ a b "Historical Perspective". Indian Navy. Retrieved 7 November 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Thana District Gazetteer 1986, The Marathas

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 27

- ^ "The Wadias of India: Then and Now". Vohuman. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 32

- ^ "Fortifying colonial legacy". The Indian Express. 15 June 1997. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ a b Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 28

- ^ Calcutta Magazine and Monthly Register 1832, p. 596

- ^ Thana District Gazetteer 1986, Acquisition, Changes, and Staff (Acquisition, 1774–1817

- ^ Kippis et al. 1814, p. 148

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 81

- ^ Segesta 2006, p. 32

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Journalism

- ^ Savant, Renu (4 July 2005). "From Lane 11 with love". Bombay Newsline. Express Group. Retrieved 2 February 2009.[dead link]

- ^ a b Thana District Gazetteer 1984, Roads (Causeways)

- ^ Thana District Gazetteer 1986, English

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 54

- ^ "Battle of Khadki". Centre for Modeling and Simulation (University of Pune). Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ Shona Adhikari (20 February 2000). "A mute testimony to a colourful age". The Tribune. India. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ a b c Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Growth of Bombay

- ^ "About Asiatic Society of Bombay". Asiatic Society of Bombay. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ "History". Elphinstone College. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Kanakalatha Mukund (3 April 2007). "Insight into the progress of banking". The Hindu. India. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ a b "Early Issues". Reserve Bank of India. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "BMC allots Rs 14 cr to upgrade Mahim Causeway". The Times of India. India. 25 October 2008. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "History". Grant Medical College and Sir J.J. Gr.of Hospitals. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ a b Palsetia 2001, p. 189

- ^ Kidambi 2007, p. 163

- ^ "The South's first station". The Hindu. India. 26 February 2003. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "A City emerges". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 128

- ^ "About University". University of Bombay. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Banking

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Stock Exchange

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Jijamata Udyan

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 64

- ^ "Bombay Port Trust is 125". The Indian Express. 26 June 1997. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 131

- ^ "Tram-Car arrives". Brihanmumbai Electric Supply and Transport. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "History". Bombay Gymkhana. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "Introduction". Bombay Stock Exchange. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "Electricity arrives in Bombay". Brihanmumbai Electric Supply and Transport (BEST). Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ "The Society". Bombay Natural History Society. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ a b "India Time Zones (IST)". Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ Sutherland & Shiffer 1884, p. 141

- ^ Aditya Sarkar, Trouble at the Mill: Factory Law and the Emergence of Labour Question in Late Nineteenth-Century Bombay (2017).

- ^ Banerjee 2006, p. 82

- ^ "Sir Dinshaw Manockjee Petit, first Baronet, 1823–1901". Vohuman. Archived from the original on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "Congress foundation day celebrated". The Hindu. India. 29 December 2006. Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "Bombay Municipal Corporation Act, 1888" (PDF, 215 KB). Government of Maharashtra. Retrieved 12 November 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 109

- ^ Dalal & Shah 2002, p. 30

- ^ Dinesh Thite. "From Distrust to Reconciliation (The Making of the Ganesh Utsav in Maharashtra)" (PDF, 124 KB). 139. Manushi: 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 74

- ^ "Rat Trap". Time Out Bombay (6). Time Out. 14 November 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kidambi 2007, p. 118

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Municipal Corporation

- ^ "History". Haffkine Institute. Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, pp. 175–7

- ^ Bagchi 2000, p. 233

- ^ D.D. Pattanaik. "The Swadeshi Movement : Culmination of Cultural Nationalism" (PDF). Orissa Review (August 2005). Government of Orissa. Archived from the original (PDF, 163 KB) on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ Agrawal & Bhatnagar 2005, p. 124

- ^ Dwivedi & Mehrotra 1995, p. 160

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Home Rule Movement

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Dawn of Gandhian Era

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Non Co-operation Movement

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Back Bay Scandal

- ^ Lalitha Sridhar (21 April 2001). "On the right track". The Hindu. India. Archived from the original on 21 January 2005. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Taran N Khan (31 May 2008). "A slice of Persia in Dongri". Daily News & Analysis. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Congress Session (of 1934)

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Businessmen and Civil Disobedience

- ^ Lala 1992, p. 98

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Economic Conditions (1933–1939)

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Outbreak of the War

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Quit India Movement

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Naval Mutiny

- ^ "A New Bombay, A new India". Hindustan Times. India. Archived from the original on 26 March 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ Greater Bombay District Gazetteer 1986, Dawn of Independence

- ^ Alexander 1951, p. 65

- ^ "Administration". Mumbai Suburban District. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ "The battle for Bombay". The Hindu. India. 13 April 2003. Archived from the original on 14 May 2005. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Samyukta Maharashtra". Government of Maharashtra. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "About IIT Bombay". Indian Institute of Technology Bombay. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ "Sons of soil: born, reborn". The Indian Express. 6 February 2008. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ Gangadharan 1970, p. 123

- ^ Geeta Desai (13 May 2008). "BMC will give jobs to kin of Samyukta Maharashtra martyrs". Mumbai Mirror. Archived from the original on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "Sena fate: From roar to meow". The Times of India. India. 29 November 2005. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "To the Present". Hindustan Times. India. Archived from the original on 26 March 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ Banerjee 2005, p. 101

- ^ Heras Institute of Indian History and Culture 1983, p. 113

- ^ "Nehru Centre, Mumbai". Nehru Science Centre. Archived from the original on 3 November 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "About Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA)". Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority. Archived from the original on 19 September 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ "General Information". Nehru Science Centre. Archived from the original on 26 October 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "About Navi Mumbai (History)". Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation (NMMC). Archived from the original on 18 September 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ "The Great Mumbai Textile Strike... 25 Years On". Rediff.com India Limited. 18 January 2007. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ^ Hansen 2001, p. 77

- ^ "Profile of Jawaharlal Nehru Custom House (Nhava Sheva)". Jawaharlal Nehru Custom House. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ Naunidhi Kaur (5–18 July 2003). "Mumbai: A decade after riots". Frontline; the Hindu. 20 (14). India. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "1993: Bombay hit by devastating bombs". BBC. 12 March 1993. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ Monica Chadha (12 September 2006). "Victims await Mumbai 1993 blasts justice". BBC. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "Mumbai Travel Guide". Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ Sheppard 1917, pp. 38, 104–105

- ^ William Safire (6 July 2006). "Mumbai Not Bombay". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ^ Verma, Kalpana (4 November 2005). "Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus chugs towards a new heritage look". Mumbai Newsline. Express Group. Retrieved 6 February 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Blast outside Ghatkopar station in Mumbai, 2 killed". rediff.com India Limited. 6 December 2002. Archived from the original on 11 August 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "1992: Mob rips apart mosque in Ayodhya". BBC. 6 December 1992. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "1 killed, 25 hurt in Vile Parle blast". The Times of India. India. 28 January 2003. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "Fear after Bombay train blast". BBC. 14 March 2003. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ Vijay Singh; Syed Firdaus Ashra (29 July 2003). "Blast in Ghatkopar in Mumbai, 4 killed and 32 injured". rediff.com India Limited. Archived from the original on 8 September 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "2003: Bombay rocked by twin car bombs". BBC. 25 August 2003. Archived from the original on 10 April 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "Maharashtra monsoon 'kills 200'". BBC. 25 July 2005. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ "At least 174 killed in Indian train blasts". CNN. 11 July 2006. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "India: A major terror target". The Times of India. India. 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "Rs 50, 000 not enough for injured". The Indian Express. 21 July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "India police: Pakistan spy agency behind Mumbai bombings". CNN. 1 October 2006. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "Thackeray continues tirade against North Indians". Daily News & Analysis. 16 February 2008. Archived from the original on 3 June 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "North Indian taxi drivers attacked in Mumbai". NDTV. 29 March 2008. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "HM announces measures to enhance security" (Press release). Press Information Bureau (Government of India). 11 December 2008. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- ^ "3 bomb blasts in Mumbai; 8 killed, 70 injured". CNN-IBN. 13 July 2011. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Mumbai-blasts-Death-toll-rises-to-26". Hindustan Times. 13 July 2011. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Death toll in Mumbai terror blasts rises to 19". NDTV. 15 July 2011. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

References

- Alexander, Horace Gundry (1951), New Citizens of India, Indian Branch, Oxford University Press

- Anderson, Philip (1854). The English in Western India. Smith and Taylor. ISBN 978-0-7661-8695-8. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- Bagchi, Amiya Kumar (2000). Private Investment in India, 1900–1939: Evolution of International Business, 1800–1945. Vol. V. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-19012-1. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- Banerjee, Anil Chandra (2006). Indian Constitutional Documents −1757-1939. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-0792-2. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- Banerjee, Sikata (2005). Make Me A Man!: Masculinity, Hinduism, And Nationalism in India. Suny Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6367-3. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- Burnell, John (2007). Bombay in the Days of Queen Anne – Being an Account of the Settlement Also: Being an Account of the Settlement. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-5547-3. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Calcutta Magazine and Monthly Register. Vol. 33–36. S. Smith & Co. 1832. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- Carsten, F. L. (1961). The New Cambridge Modern History (Volume V: The ascendancy of France 1648–88). Vol. V. Cambridge University Press Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-04544-5. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- Da Cunha, J.Gerson (1993). Origin of Bombay. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0815-1. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- Dalal, Shilpa; Aparna Kaji Shah (2002). Bombay!. BPI (India). ISBN 978-81-7693-005-5.

- David, M. D. (1973), History of Bombay, 1661–1708, University of Bombay

- Dwivedi, Sharada; Rahul Mehrotra (1995), Bombay: The Cities Within, Eminence Designs

- Edwardes, Stephen Meredyth (1902). The Rise of Bombay: A Retrospect. Times of India Press.

- Baptista, Elsie Wilhelmina (1967), The East Indians: Catholic Community of Bombay, Salsette and Bassein, Bombay East Indian Association

- Gangadharan, K. K. (1970), Sociology of Revivalism: A Study of Indianization, Sanskritization, and Golwalkarism, Kalamkar Prakashan

- Ghosh, Amalananda (1990). An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09264-8. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- Greater Bombay District Gazetteer, Maharashtra State Gazetteers, vol. 27, Government of Maharashtra, 1960, archived from the original on 6 September 2008, retrieved 13 August 2008

- Greater Bombay District Gazetteer, Maharashtra State Gazetteers, vol. III, Government of Maharashtra, 1986, archived from the original on 9 March 2008, retrieved 15 August 2008

- Hansen, Thomas Blom (2001). Wages of Violence: Naming and Identity in Postcolonial Bombay. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08840-2. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- Heras Institute of Indian History and Culture (1983), Indica, vol. 20, St. Xavier's College (Bombay)

- Hughes, William (1863), The geography of British history, Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, retrieved 15 January 2009

- Sutherland, Joseph Myers; Richard J. Shiffer (1884). "International Conference Held at Washington for the Purpose of Fixing a Prime Meridian and a Universal Day. October, 1884 Protocols of the Proceedings". Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- Kidambi, Prashant (2007). The Making of an Indian Metropolis: Colonial Governance and Public Culture in Bombay, 1890–1920. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-5612-8. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- Kippis, Andrew; William Godwin, George Robinson, G. G. and J. Robinson (1813). The New Annual Register, Or General Repository of History, Politics, and Literature, for the Year 1813. Pater-noster-Row. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lala, R. M (1992). Beyond the Last Blue Mountain: A Life of J.R.D. Tata. Viking. ISBN 9788184753318. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Leonard, Thomas M. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Vol. 1. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-97662-6. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- Malabari, Phiroze B.M. (1910). Bombay in the making : Being mainly a history of the origin and growth of judicial institutions in the Western Presidency, 1661–1726 (PDF). London: T. Fisher Unwin. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- Mehta, Ashok (1940). "Indian Shipping: A Case Study of the Working of Imperialism" (PDF). N.t.Shroff Company Limited. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- "Portuguese Settlements on the Western Coast" (PDF). Maharashtra State Gazetteer. Government of Maharashtra. 1977. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- Misra, Satish Chandra (1982), The Rise of Muslim Power in Gujarat: A History of Gujarat from 1298 to 1442, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers

- Murray, Sarah Elizabeth (2007). Moveable Feasts: From Ancient Rome to the 21st century, the Incredible Journeys of the Food We Eat. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-35535-7. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Nairne, Alexander Kyd (1988). History of the Konkan. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0275-5. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- O'Brien, Derek (2003). The Mumbai Factfile. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-302947-2.

- Palsetia, Jesse S. (2001). The Parsis of India: Preservation of Identity in Bombay City. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12114-0. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- Prinsep, James; Edward Thomas, Henry Thoby Prinsep (1858). Essays on Indian Antiquities, Historic, Numismatic, and Palæographic, of the Late James Prinsep. Vol. 2. J. Murray. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- Ring, Trudy; Robert M. Salkin, Sharon La Boda (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Segesta, Editrice (2006), Abitare

- Singh, K. S.; Bhanu, B. V.; Bhatnagar, B. R.; Bose, D. K.; Kulkarni, V. S.; Sreenath, J., eds. (2004). Maharashtra. Vol. XXX. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7991-102-0. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- Sheppard, Samuel T (1917). Bombay Place-Names and Street-Names:An excursion into the by-ways of the history of Bombay City. Bombay, India: The Times Press. ASIN B0006FF5YU.

- Shroff, Zenobia E. (2001), The Contribution of Parsis to Education in Bombay City, 1820–1920, Himalaya Publishing House

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (1997). The Career and Legend of Vasco Da Gama. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64629-4. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- Thana District Gazetteer, Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency, vol. XIII, Government of Maharashtra, 1984 [1882], archived from the original on 12 August 2007, retrieved 10 November 2008

- Thana District Gazetteer, Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency, vol. XIII, Government of Maharashtra, 1986 [1882], archived from the original on 14 February 2009, retrieved 15 August 2008

- Thana — Places of Interest, Gazetteers of the Bombay Presidency, vol. XIV, Government of Maharashtra, 2000 [1882], archived from the original on 9 August 2008, retrieved 14 August 2008

- Yimene, Ababu Minda (2004). An African Indian Community in Hyderabad: Siddi Identity, Its Maintenance and Change. Cuvillier Verlag. ISBN 3-86537-206-6. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

Bibliography

- Agarwal, Jagdish (1998). Bombay — Mumbai: A Picture Book. Wilco Publishing House. ISBN 81-87288-35-3.

- Chandavarkar, Rajnarayan. "Workers' politics and the mill districts in Bombay between the wars." Modern Asian Studies 15.3 (1981): 603-647 Online.

- Chaudhari, K.K (1987). "History of Bombay". Modern Period Gazetteers Department, Government of Maharashtra.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Contractor, Behram (1998). From Bombay to Mumbai. Oriana Books.

- Cox, Edmund Charles (1887). "Short History of Bombay Presidency". Thacker & Company.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Douglas, James (1900). Glimpses of old Bombay and western India, with other papers. Sampson Low, Marston & Co., London.

- Katiyar, Arun; Namas Bhojani (1996). Bombay, A Contemporary Account. Harper Collins. ISBN 81-7223-216-0.

- Kooiman, Dick. "Jobbers and the emergence of trade unions in Bombay city." International Review of Social History 22.3 (1977): 313–328. online

- MacLean, James Mackenzie (1876). "A Guide to Bombay". Bombay Gazette Steam Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Mehta, Suketu (2004). Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-40372-9.

- Morris, Morris David. The emergence of an industrial labor force in India: A study of the Bombay cotton mills, 1854-1947 (U of California Press, 1965).

- Patel, Sujata; Alice Thorner (1995). Bombay, Metaphor for Modern India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-563688-0.

- Pinki, Virani (1999). Once was Bombay. Viking. ISBN 0-670-88869-9.

- Sarkar, Aditya. Trouble at the Mill: Factory Law and the Emergence of Labour Question in Late Nineteenth-Century Bombay (Oxford UP, 2017) online review

- Sheppard, Samuel T. (1917). Bombay Place-names and Street-names: An excursion into the by-ways of the history of Bombay City. Times Press, Bombay.

- Tindall, Gillian (1992). City of Gold. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 0-14-009500-4.

- Upadhaya, Sashibushan. Existence, Identity, and Mobilization: The Cotton Millworkers of Bombay, 1890-1919 (New Delhi: Manohar, 2004).

- Handbook of the Bombay Presidency: With an account of Bombay city. John Murray, London. 1881.

- Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (Volume XXI). Government Central Press. 1884.

External links

- Portuguese India History: The Northern Province: Bassein, Bombay-Mumbai, Damao, Chaul from Dutch Portuguese Colonial History

- Century City Time Line – Bombay from Tate

- A collection of pages on Mumbai's History from Time Out (Mumbai)

- The Mumbai Project from Hindustan Times