Chinese Civil War

| Chinese Civil War 國共內戰 / 国共内战 (Kuomintang-Communist Civil War) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War (from 1947) and the Cross-Strait conflict (from 1949) | |||||||||

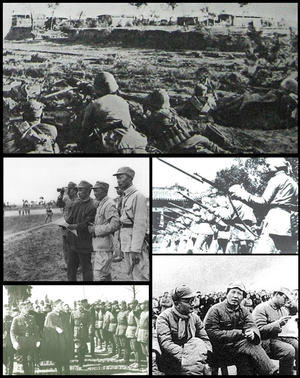

Clockwise from the top: communist troops at the Battle of Siping; Muslim soldiers of the NRA; Mao Zedong in the 1930s; Chiang Kai-shek inspecting soldiers; CCP general Su Yu investigating the troops shortly before the Menglianggu campaign | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

1927–1937 |

1927–1937

| ||||||||

|

1946–1949 |

1946–1949

| ||||||||

|

1949–1961

|

1949–1961 | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

Other leaders | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| c. 1.5 million (1948–1949)[6] | c. 250,000 (1948–1949)[6] | ||||||||

| Chinese Civil War | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 國共內戰 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 国共内战 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Kuomintang-Communist Civil War | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Political revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

The Chinese Civil War was a civil war in China fought between the Kuomintang (KMT)-led government of the Republic of China (ROC) and the Communist Party of China (CPC) lasting intermittently between 1927 and 1949. The war is generally divided into two phases with an interlude: from August 1927 to 1937, the KMT-CPC Alliance collapsed during the Northern Expedition, and the Nationalists controlled most of China. From 1937 to 1945, hostilities were put on hold, and the Second United Front fought the Japanese invasion of China with eventual help from the Allies of World War II. The civil war resumed with the Japanese defeat, and the CPC gained the upper hand in the final phase of the war from 1945–1949, generally referred to as the Chinese Communist Revolution.

The Communists gained control of mainland China and established the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, forcing the leadership of the Republic of China to retreat to the island of Taiwan.[9] A lasting political and military standoff between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait ensued, with the ROC in Taiwan and the PRC in mainland China both officially claiming to be the legitimate government of all China. No armistice or peace treaty has ever been signed and debate continues as to whether the civil war has legally ended.[10]

Background

| History of the Republic of China |

|---|

|

|

|

Following the collapse of the Qing dynasty in the aftermath of the Xinhai Revolution, China fell into a brief period of civil war before Yuan Shikai assumed the presidency of the newly formed Republic of China.[11][page needed] The administration became known as the Beiyang Government, with its capital in Peking. Yuan Shikai was frustrated in a short-lived attempt to restore monarchy in China, with himself as the Hongxian Emperor. After the death of Yuan Shikai in 1916, the following years were characterized by the power struggle between different cliques in the former Beiyang Army. In the meantime, the Kuomintang, led by Sun Yat-sen, created a new government in Guangzhou to resist the rule of Beiyang Government through a series of movements.

Sun's efforts to obtain aid from the several countries were ignored, thus he turned to the Soviet Union in 1921. For political expediency, the Soviet leadership initiated a dual policy of support for both Sun and the newly established Communist Party of China, which would eventually found the People's Republic of China. Thus the struggle for power in China began between the KMT and the CPC.

In 1923, a joint statement by Sun and Soviet representative Adolph Joffe in Shanghai pledged Soviet assistance to China's unification.[12] The Sun-Joffe Manifesto was a declaration of cooperation among the Comintern, KMT and CPC.[12] Comintern agent Mikhail Borodin arrived in China in 1923 to aid in the reorganization and consolidation of the KMT along the lines of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The CPC joined the KMT to form the First United Front.[5]

In 1923, Sun sent Chiang Kai-shek, one of his lieutenants from his Tongmenghui days, for several months of military and political study in the Soviet capital Moscow.[13] By 1924, Chiang became the head of the Whampoa Military Academy, and rose to prominence as Sun's successor as head of the KMT.[13]

The Soviets provided the academy with much educational material, organization and equipment, including munitions.[13] They also provided education in many of the techniques for mass mobilization. With this aid, Sun was able to raise a dedicated "army of the party," with which he hoped to defeat the warlords militarily. CPC members were also present in the academy, and many of them became instructors, including Zhou Enlai, who was made a political instructor.[14]

Communist members were allowed to join the KMT on an individual basis.[12] The CPC itself was still small at the time, having a membership of 300 in 1922 and only 1,500 by 1925.[15] As of 1923, the KMT had 50,000 members.[15]

However, after Sun died in 1925, the KMT split into left- and right-wing movements. KMT members worried that the Soviets were trying to destroy the KMT from inside using the CPC. The CPC then began movements in opposition of the Northern Expedition, passing a resolution against it at a party meeting.

Then, in March 1927, the KMT held its second party meeting where the Soviets helped pass resolutions against the Expedition and curbing Chiang's power. Soon, the KMT would be clearly divided.

Throughout this time the Soviet Union had a large impact on the Communist Party of China. They sent money and spies to support the Chinese Communist Party. Without their support, the communist party likely would have failed. There are documents showing of other communist parties in China at the time, one with as many as 10,000 members, but they all failed without support from the Soviet Union.[16]

Northern Expedition and KMT-CPC split

In early 1927, the KMT-CPC rivalry led to a split in the revolutionary ranks. The CPC and the left wing of the KMT had decided to move the seat of the KMT government from Guangzhou to Wuhan, where communist influence was strong.[15] However, Chiang and Li Zongren, whose armies defeated warlord Sun Chuanfang, moved eastward toward Jiangxi. The leftists rejected Chiang's demand to eliminate Communist influence within KMT and Chiang denounced them for betraying Sun Yat-sen's Three Principles of the People by taking orders from the Soviet Union. According to Mao Zedong, Chiang's tolerance of the CPC in the KMT camp decreased as his power increased.[17]

On April 7, Chiang and several other KMT leaders held a meeting, during which they proposed that Communist activities were socially and economically disruptive and had to be undone for the Nationalist revolution to proceed. On April 12, in Shanghai, many Communist members in the KMT were purged through hundreds of arrests and executions[18] on the orders of General Bai Chongxi. The CPC referred to this as the April 12 Incident or Shanghai Massacre.[19] This incident widened the rift between Chiang and Wang Jingwei, the leader of the left wing faction of the KMT who controlled the city of Wuhan.

Eventually, the left wing of the KMT also expelled CPC members from the Wuhan government, which in turn was toppled by Chiang Kai-shek. The KMT resumed its campaign against warlords and captured Beijing in June 1928.[20] Soon, most of eastern China was under the control of the Nanjing central government, which received prompt international recognition as the sole legitimate government of China. The KMT government announced, in conformity with Sun Yat-sen, the formula for the three stages of revolution: military unification, political tutelage, and constitutional democracy.[21]

Communist insurgency (1927–1937)

| Second National Revolutionary War (Mainland China) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 第二次國內革命戰爭 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 第二次国内革命战争 | ||||||

| |||||||

On 1 August 1927, the Communist Party launched an uprising in Nanchang against the Nationalist government in Wuhan. This conflict led to the creation of the Red Army.[1][22] On August 4, the main forces of the Red Army left Nanchang and headed southwards for an assault on Guangdong. Nationalist forces quickly reoccupied Nanchang while the remaining members of the CPC in Nanchang went into hiding.[1] A CPC meeting on August 7 confirmed the objective of the party was to seize the political power by force, but the CPC was quickly suppressed the next day on August 8 by the Nationalist government in Wuhan led by Wang Jingwei. On August 14, Chiang Kai-shek announced his temporary retirement, as the Wuhan faction and Nanjing faction of the Kuomintang were allied once again with common goal of suppressing the Communist Party after the earlier split.[citation needed]

Attempts were later made by the CPC to take the cities of Changsha, Shantou and Guangzhou. The Red Army consisting of mutinous former National Revolutionary Army (NRA) soldiers as well as armed peasants established control over several areas in southern China.[22] KMT forces continued to attempt to suppress the rebellions.[22] Then, in September, Wang Jingwei was forced out of Wuhan. September also saw an unsuccessful armed rural insurrection, known as the Autumn Harvest Uprising, led by Mao Zedong.[23] Borodin then returned to the USSR in October via Mongolia. In November, Chiang Kai-shek went to Shanghai and invited Wang to join him. On December 11, the CPC started the Guangzhou Uprising, establishing a soviet there the next day, but lost the city by December 13 to a counter-attack under the orders of General Zhang Fakui. On December 16, Wang Jingwei fled to France. There were now three capitals in China: the internationally recognized republic capital in Beijing, the CPC and left-wing KMT at Wuhan and the right-wing KMT regime at Nanjing, which would remain the KMT capital for the next decade.[24][25]

This marked the beginning of a ten-year armed struggle, known in mainland China as the "Ten-Year Civil War" (十年内战) which ended with the Xi'an Incident when Chiang Kai-shek was forced to form the Second United Front against invading forces from the Empire of Japan. In 1930 the Central Plains War broke out as an internal conflict of the KMT. It was launched by Feng Yuxiang, Yan Xishan and Wang Jingwei. The attention was turned to root out remaining pockets of Communist activity in a series of five encirclement campaigns.[26] The first and second campaigns failed and the third was aborted due to the Mukden Incident. The fourth campaign (1932–1933) achieved some early successes, but Chiang's armies were badly mauled when they tried to penetrate into the heart of Mao's Soviet Chinese Republic. During these campaigns, KMT columns struck swiftly into Communist areas, but were easily engulfed by the vast countryside and were not able to consolidate their foothold.

Finally, in late 1934, Chiang launched a fifth campaign that involved the systematic encirclement of the Jiangxi Soviet region with fortified blockhouses.[27] Unlike previous campaigns in which they penetrated deeply in a single strike, this time the KMT troops patiently built blockhouses, each separated by about five miles, to surround the Communist areas and cut off their supplies and food sources.[27]

In October 1934 the CPC took advantage of gaps in the ring of blockhouses (manned by the forces of a warlord ally of Chiang Kai-shek's, rather than regular KMT troops) and broke out of the encirclement. The warlord armies were reluctant to challenge Communist forces for fear of losing their own men and did not pursue the CPC with much fervor. In addition, the main KMT forces were preoccupied with annihilating Zhang Guotao's army, which was much larger than Mao's. The massive military retreat of Communist forces lasted a year and covered what Mao estimated as 12,500 km (25,000 Li); it became known as the Long March.[28] The Long March was a military retreat taken on by the Communist Party of China, led by Mao Zedong to evade the pursuit or attack of the Kuomintang army. It consisted of a series of marches, during which numerous Communist armies in the south escaped to the north and west. Over the course of the march from Jiangxi the First Front Army, led by an inexperienced military commission, was on the brink of annihilation by Chiang Kai Shek's troops as their stronghold was in Jiangxi. The Communists, under the command of Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, "escaped in a circling retreat to the west and north, which reportedly traversed over 9,000 kilometers over 370 days." The route passed through some of the most difficult terrain of western China by traveling west, and then northwards towards Shaanxi. "In November 1935, shortly after settling in northern Shaanxi, Mao officially took over Zhou Enlai's leading position in the Red Army. Following a major reshuffling of official roles, Mao became the chairman of the Military Commission, with Zhou and Deng Xiaoping as vice-chairmen." This marked Mao's position as the pre-eminent leader of the Party, with Zhou in second position to him.[citation needed]

The march ended when the CPC reached the interior of Shaanxi. Zhang Guotao's army, which took a different route through northwest China, was largely destroyed by the forces of Chiang Kai-shek and his Chinese Muslim allies, the Ma clique. Along the way, the Communist army confiscated property and weapons from local warlords and landlords, while recruiting peasants and the poor, solidifying its appeal to the masses. Of the 90,000–100,000 people who began the Long March from the Soviet Chinese Republic, only around 7,000–8,000 made it to Shaanxi.[29] The remnants of Zhang's forces eventually joined Mao in Shaanxi, but with his army destroyed, Zhang, even as a founding member of the CPC, was never able to challenge Mao's authority. Essentially, the great retreat made Mao the undisputed leader of the Communist Party of China.

The Kuomintang used Khampa troops—who were former bandits—to battle the Communist Red Army as it advanced and to undermine local warlords who often refused to fight Communist forces to conserve their own strength. The KMT enlisted 300 "Khampa bandits" into its Consolatory Commission military in Sichuan, where they were part of the effort of the central government to penetrate and destabilize local Han warlords such as Liu Wenhui. The government was seeking to exert full control over frontier areas against the warlords. Liu had refused to battle the Communists in order to conserve his army. The Consolatory Commission forces were used to battle the Red Army, but they were defeated when their religious leader was captured by the Communists.[30]

In 1936, Zhou Enlai and Zhang Xueliang grew closer, with Zhang even suggesting that he join the CPC. However, this was turned down by the Comintern in the USSR. Later on, Zhou persuaded Zhang and Yang Hucheng, another warlord, to instigate the Xi'an Incident. Chiang was placed under house arrest and forced to stop his attacks on the Red Army, instead focusing on the Japanese threat.

-

The situation in China in 1929: After the Northern Expedition, the KMT had direct control over east and central China, while the rest of China proper as well as Manchuria was under the control of warlords loyal to the Nationalist government.

-

Map showing the communist-controlled Soviet Zones of China during and after the encirclement campaigns

-

Route(s) taken by Communist forces during the Long March

-

A Communist leader addressing survivors of the Long March

Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945)

During Japan's invasion and occupation of Manchuria Chiang Kai-shek, who saw the CPC as a greater threat, refused to ally with them to fight against the Imperial Japanese Army. Chiang preferred to unite China by eliminating the warlords and CPC forces first. He believed that he was still too weak to launch an offensive to chase out Japan and that China needed time for a military build-up. Only after unification would it be possible for the KMT to mobilize a war against Japan. So he would rather ignore the discontent and anger among Chinese people at his policy of compromise with the Japanese, and ordered KMT generals Zhang Xueliang and Yang Hucheng to carry out suppression of the CPC; however, their provincial forces suffered significant casualties in battles with the Red Army.ref

On 12 December 1936, the disgruntled Zhang Xueliang and Yang Hucheng conspired to kidnap Chiang and force him into a truce with the CPC. The incident became known as the Xi'an Incident.[31] Both parties suspended fighting to form a Second United Front to focus their energies and fighting against the Japanese.[31] In 1937 Japan launched its full-scale invasion of China and its well-equipped troops overran KMT defenders in northern and coastal China.

The alliance of CPC and KMT was in name only.[32] Unlike the KMT forces, CPC troops shunned conventional warfare and instead engaged in guerrilla warfare against the Japanese. The level of actual cooperation and coordination between the CPC and KMT during World War II was at best minimal.[32] In the midst of the Second United Front, the CPC and the KMT were still vying for territorial advantage in "Free China" (i.e., areas not occupied by the Japanese or ruled by Japanese puppet governments such as Manchukuo and the Reorganized National Government of China).[32]

The situation came to a head in late 1940 and early 1941 when clashes between Communist and KMT forces intensified. Chiang demanded in December 1940 that the CPC's New Fourth Army evacuate Anhui and Jiangsu Provinces, due to its provocation and harassment of KMT forces in this area. Under intense pressure, the New Fourth Army commanders complied. The following year they were ambushed by KMT forces during their evacuation, which led to several thousand deaths.[33] It also ended the Second United Front, which had been formed earlier to fight the Japanese.[33]

As clashes between the CPC and KMT intensified, countries such as the United States and the Soviet Union attempted to prevent a disastrous civil war. After the New Fourth Army incident, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent special envoy Lauchlin Currie to talk with Chiang Kai-shek and KMT party leaders to express their concern regarding the hostility between the two parties, with Currie stating that the only ones to benefit from a civil war would be the Japanese. The Soviet Union, allied more closely with the CPC, sent an imperative telegram to Mao in 1941, warning that civil war would also make the situation easier for the Japanese military. Due to the international community's efforts, there was a temporary and superficial peace. Chiang attacked the CPC in 1943 with the propaganda piece China's Destiny, which questioned the CPC's power after the war, while the CPC strongly opposed Chiang's leadership and referred to his regime as fascist in an attempt to generate a negative public image. Both leaders knew that a deadly battle had begun between themselves.[34]

In general, developments in the Second Sino-Japanese War were to the advantage of the CPC, as its guerrilla war tactics had won them popular support within the Japanese-occupied areas. However, the KMT had to defend the country against the main Japanese campaigns, since it was the legal Chinese government, and this proved costly to Chiang Kai-shek and his troops. Japan launched its last major offensive against the KMT, Operation Ichi-Go, in 1944; this resulted in the severe weakening of Chiang's forces.[35] The CPC also suffered fewer losses through its guerrilla tactics. By the end of the war, the Red Army had grown to more than 1.3 million members, with a separate militia of over 2.6 million members. About one hundred million people lived in CPC-controlled zones.

Immediate post-war clashes (1945–1946)

Under the terms of the Japanese unconditional surrender dictated by the United States, Japanese troops were ordered to surrender to KMT troops and not to the CPC, which was present in some of the occupied areas.[36] In Manchuria, however, where the KMT had no forces, the Japanese surrendered to the Soviet Union. Chiang Kai-shek ordered the Japanese troops to remain at their post to receive the Kuomintang and not surrender their arms to the Communists.[36]

The first post-war peace negotiation, attended by both Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong, was in Chongqing from 28 August to 10 October 1945. It concluded with the signing of the Double Tenth Agreement.[37] Both sides stressed the importance of a peaceful reconstruction, but the conference did not produce any concrete results.[37] Battles between the two sides continued even as peace negotiations were in progress, until the agreement was reached in January 1946. However, large campaigns and full-scale confrontations between the CPC and Chiang's troops were temporarily avoided.

In the last month of World War II in East Asia, Soviet forces launched the huge Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation against the Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchuria and along the Chinese-Mongolian border.[38] This operation destroyed the Kwantung Army in just three weeks and left the USSR occupying all of Manchuria by the end of the war in a total power vacuum of local Chinese forces. Consequently, the 700,000 Japanese troops stationed in the region surrendered. Later in the year Chiang Kai-shek realized that he lacked the resources to prevent a CPC takeover of Manchuria following the scheduled Soviet departure.[39] He therefore made a deal with the Soviets to delay their withdrawal until he had moved enough of his best-trained men and modern material into the region. However, the Soviets refused permission for the Nationalist troops to traverse its territory. KMT troops were then airlifted by the US to occupy key cities in North China, while the countryside was already dominated by the CPC. On 15 November 1945, the ROC began a campaign to prevent the CPC from strengthening its already strong base.[40] The Soviets spent the extra time systematically dismantling the extensive Manchurian industrial base (worth up to $2 billion) and shipping it back to their war-ravaged country.[39]

In 1945–46, during the Soviet Red Army Manchurian campaign, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin commanded Marshal Rodion Malinovsky to give Mao Zedong most Imperial Japanese Army weapons that were captured.[41]

Chiang Kai-shek's forces pushed as far as Chinchow (Jinzhou) by 26 November 1945, meeting with little resistance. This was followed by a Communist offensive on the Shandong Peninsula that was largely successful, as all of the peninsula, except what was controlled by the US, fell to the Communists.[40] The truce fell apart in June 1946 when full-scale war between CPC and KMT forces broke out on 26 June 1946. China then entered a state of civil war that lasted more than three years.[42]

Resumed fighting (1946–1949)

Background and disposition of forces

| Third National Revolutionary War (Mainland China) | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 第三次國內革命戰爭 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 第三次国内革命战争 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| War of Liberation (mainland China) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 解放戰爭 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 解放战争 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Anti-Communist Counter-insurgency War (Taiwan) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 反共戡亂戰爭 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 反共戡乱战争 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese People's Liberation War (mainland China) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國人民解放戰爭 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国人民解放战争 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

By the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the power of the Communist Party grew considerably. Their main force grew to 1.2 million troops, backed with additional militia of 2 million, totalling 3.2 million troops. Their "Liberated Zone" in 1945 contained 19 base areas, including one-quarter of the country's territory and one-third of its population; this included many important towns and cities. Moreover, the Soviet Union turned over all of its captured Japanese weapons and a substantial amount of their own supplies to the Communists, who received Northeastern China from the Soviets as well.[43]

In March 1946, despite repeated requests from Chiang, the Soviet Red Army under the command of Marshal Rodion Malinovsky continued to delay pulling out of Manchuria, while Malinovsky secretly told the CPC forces to move in behind them, which led to full-scale war for the control of the Northeast. These favorable conditions also facilitated many changes inside the Communist leadership: the more radical hard-line faction who wanted full military bloodshed and warfare to take-over China finally gained the upper hand and defeated the careful opportunists.[44] Prior to giving control to Communist leaders, on March 27 Soviet diplomats requested a joint venture of industrial development with the Nationalist Party in Manchuria.[45]

Although General Marshall stated that he knew of no evidence that the CPC was being supplied by the Soviet Union, the CPC was able to utilize a large number of weapons abandoned by the Japanese, including some tanks, but it was not until large numbers of well-trained KMT troops began surrendering and joining the Communist forces that the CPC was finally able to master the hardware.[46][47] However, despite the disadvantage in military hardware, the CPC's ultimate trump card was its land reform policy. The CPC continued to make the irresistible promise in the countryside to the massive number of landless and starving peasants that by fighting for the CPC they would be given their own land to grow crops once the victory was won.[48]

This strategy enabled the CPC to access an almost unlimited supply of manpower for both combat and logistical purposes; despite suffering heavy casualties throughout many of the war's campaigns, man power continued to pour in massively. For example, during the Huaihai Campaign alone the CPC was able to mobilize 5,430,000 peasants to fight against the KMT forces.[49]

After the war with the Japanese ended, Chiang Kai-shek quickly moved KMT troops to newly liberated areas to prevent Communist forces from receiving the Japanese surrender.[43] The US airlifted many KMT troops from central China to the Northeast (Manchuria). President Harry S. Truman was very clear about what he described as "using the Japanese to hold off the Communists." In his memoirs he writes:

It was perfectly clear to us that if we told the Japanese to lay down their arms immediately and march to the seaboard, the entire country would be taken over by the Communists. We therefore had to take the unusual step of using the enemy as a garrison until we could airlift Chinese National troops to South China and send Marines to guard the seaports.

— President Truman[50]

Using the pretext of "receiving the Japanese surrender," business interests within the KMT government occupied most of the banks, factories and commercial properties, which had previously been seized by the Imperial Japanese Army.[43] They also conscripted troops at an accelerated pace from the civilian population and hoarded supplies, preparing for a resumption of war with the Communists. These hasty and harsh preparations caused great hardship for the residents of cities such as Shanghai, where the unemployment rate rose dramatically to 37.5%.[43]

The US strongly supported the Kuomintang forces. About 50,000 US soldiers were sent to guard strategic sites in Hupeh and Shandong in Operation Beleaguer. The US equipped and trained KMT troops, and transported Japanese and Koreans back to help KMT forces to occupy liberated zones as well as to contain Communist-controlled areas.[43] According to William Blum, American aid included substantial amounts of mostly surplus military supplies, and loans were made to the KMT.[51] Within less than two years after the Sino-Japanese War, the KMT had received $4.43 billion from the US—most of which was military aid.[43]

Outbreak of war

-

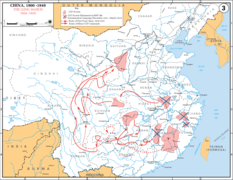

Situation in 1947

-

Situation in the fall of 1948

-

Situation in the winter of 1948 and 1949

-

Situation in April to October 1949

As postwar negotiations between the Nationalist government in Nanjing and the Communist Party failed, the civil war between these two parties resumed. This stage of war is referred to in mainland China and Communist historiography as the "War of Liberation" (Chinese: 解放战争; pinyin: Jiěfàng Zhànzhēng). On 20 July 1946, Chiang Kai-shek launched a large-scale assault on Communist territory in North China with 113 brigades (a total of 1.6 million troops).[43] This marked the first stage of the final phase in the Chinese Civil War.

Knowing their disadvantages in manpower and equipment, the CPC executed a "passive defense" strategy. It avoided the strong points of the KMT army and was prepared to abandon territory in order to preserve its forces. In most cases the surrounding countryside and small towns had come under Communist influence long before the cities. The CPC also attempted to wear out the KMT forces as much as possible. This tactic seemed to be successful; after a year, the power balance became more favorable to the CPC. They wiped out 1.12 million KMT troops, while their strength grew to about two million men.[43]

In March 1947 the KMT achieved a symbolic victory by seizing the CPC capital of Yan'an.[52] The Communists counterattacked soon afterwards; on 30 June 1947 CPC troops crossed the Yellow River and moved to the Dabie Mountains area, restored and developed the Central Plain. At the same time, Communist forces also began to counterattack in Northeastern China, North China and East China.[43]

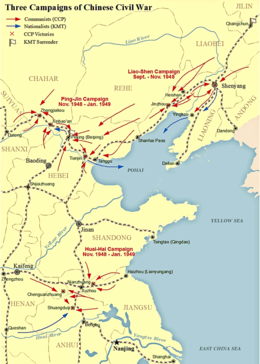

By late 1948, the CPC eventually captured the northern cities of Shenyang and Changchun and seized control of the Northeast after suffering numerous setbacks while trying to take the cities, with the decisive Liaoshen Campaign.[53] The New 1st Army, regarded as the best KMT army, was forced to surrender after the CPC conducted a brutal six-month siege of Changchun that resulted in more than 150,000 civilian deaths from starvation.[54]

The capture of large KMT units provided the CPC with the tanks, heavy artillery and other combined-arms assets needed to execute offensive operations south of the Great Wall. By April 1948 the city of Luoyang fell, cutting the KMT army off from Xi'an.[55] Following a fierce battle, the CPC captured Jinan and Shandong province on 24 September 1948. The Huaihai Campaign of late 1948 and early 1949 secured east-central China for the CPC.[53] The outcome of these encounters were decisive for the military outcome of the civil war.[53]

The Pingjin Campaign resulted in the Communist conquest of northern China. It lasted 64 days, from 21 November 1948 to 31 January 1949.[56] The PLA suffered heavy casualties while securing Zhangjiakou, Tianjin along with its port and garrison at Dagu and Beiping.[56] The CPC brought 890,000 troops from the northeast to oppose some 600,000 KMT troops.[55] There were 40,000 CPC casualties at Zhangjiakou alone. They in turn killed, wounded or captured some 520,000 KMT during the campaign.[56]

After achieving decisive victory at Liaoshen, Huaihai and Pingjin campaigns, the CPC wiped out 144 regular and 29 irregular KMT divisions, including 1.54 million veteran KMT troops, which significantly reduced the strength of Nationalist forces.[43] Stalin initially favored a coalition government in postwar China, and tried to persuade Mao to stop the CPC from crossing the Yangtze and attacking the KMT positions south of the river.[57] Mao rejected Stalin's position and on 21 April, and began the Yangtze River Crossing Campaign. On 23 April they captured the KMT's capital, Nanjing.[28] The KMT government retreated to Canton (Guangzhou) until October 15, Chongqing until November 25, and then Chengdu before retreating to Taiwan on December 10. By late 1949 the People's Liberation Army was pursuing remnants of KMT forces southwards in southern China, and only Tibet was left. In addition, the Ili Rebellion was a Soviet-backed revolt by the Second East Turkestan Republic against the KMT from 1944–49, as the Mongolians in the People's Republic were in a border dispute with the Republic of China. A Chinese Muslim Hui cavalry regiment, the 14th Tungan Cavalry, was sent by the Chinese government to attack Mongol and Soviet positions along the border during the Pei-ta-shan Incident.[58][59]

The Kuomintang made several last-ditch attempts to use Khampa troops against the Communists in southwest China. The Kuomintang formulated a plan in which three Khampa divisions would be assisted by the Panchen Lama to oppose the Communists.[60] Kuomintang intelligence reported that some Tibetan tusi chiefs and the Khampa Su Yonghe controlled 80,000 troops in Sichuan, Qinghai and Tibet. They hoped to use them against the Communist army.[61]

Fighting subsides

On 1 October 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People's Republic of China with its capital at Beiping, which was returned to the former name Beijing. Chiang Kai-shek and approximately two million Nationalist soldiers retreated from mainland China to the island of Taiwan in December after the PLA advanced into the Sichuan province. Isolated Nationalist pockets of resistance remained in the area, but the majority of the resistance collapsed after the fall of Chengdu on 10 December 1949, with some resistance continuing in the far south.[62]

A PRC attempt to take the ROC-controlled island of Quemoy was thwarted in the Battle of Kuningtou, halting the PLA advance towards Taiwan.[63] In December 1949, Chiang proclaimed Taipei the temporary capital of the Republic of China and continued to assert his government as the sole legitimate authority in China.

The Communists' other amphibious operations of 1950 were more successful: they led to the Communist conquest of Hainan Island in April 1950, capture of Wanshan Islands off the Guangdong coast (May–August 1950), Zhoushan Island off Zhejiang (May 1950).[64]

Aftermath

The Communist military forces suffered 1.3 million combat casualties in the 1945–1949 phase of the war: 260,000 killed, 190,000 missing, and 850,000 wounded, discounting irregulars. Nationalist casualties in the same phase were recorded after the war by the PRC 5,452,700 regulars and 2,258,800 irregulars.[65]

Most observers expected Chiang's government to eventually fall to the imminent invasion of Taiwan by the People's Liberation Army, and the US was initially reluctant in offering full support for Chiang in their final stand. US President Harry S. Truman announced on 5 January 1950 that the United States would not engage in any dispute involving the Taiwan Strait, and that he would not intervene in the event of an attack by the PRC.[66] The situation quickly changed after the onset of the Korean War in June 1950. This led to changing political climate in the US, and President Truman ordered the United States Seventh Fleet to sail to the Taiwan Strait as part of the containment policy against potential Communist advance.[67]

In June 1949 the ROC declared a "closure" of all mainland China ports and its navy attempted to intercept all foreign ships. The closure was from a point north of the mouth of Min River in Fujian to the mouth of the Liao River in Liaoning.[68] Since mainland China's railroad network was underdeveloped, north-south trade depended heavily on sea lanes. ROC naval activity also caused severe hardship for mainland China fishermen.

After losing mainland China, a group of approximately 3,000 KMT Central soldiers retreated to Burma and continued launching guerrilla attacks into south China during the Kuomintang Islamic Insurgency in China (1950–1958) and Campaign at the China–Burma Border. Their leader, Gen. Li Mi, was paid a salary by the ROC government and given the nominal title of Governor of Yunnan. Initially, the US supported these remnants and the Central Intelligence Agency provided them with military aid. After the Burmese government appealed to the United Nations in 1953, the US began pressuring the ROC to withdraw its loyalists. By the end of 1954 nearly 6,000 soldiers had left Burma and General Li declared his army disbanded. However, thousands remained, and the ROC continued to supply and command them, even secretly supplying reinforcements at times to maintain a base close to China.

After the ROC complained to the United Nations against the Soviet Union for violating the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance to support the CPC, the UN General Assembly Resolution 505 was adopted on 1 February 1952, condemning the Soviet Union.

Though viewed as a military liability by the US, the ROC viewed its remaining islands in Fujian as vital for any future campaign to defeat the PRC and retake mainland China. On 3 September 1954, the First Taiwan Strait Crisis began when the PLA started shelling Kinmen and threatened to take the Dachen Islands in Zhejiang.[68] On 20 January 1955, the PLA took nearby Yijiangshan Island, with the entire ROC garrison of 720 troops killed or wounded defending the island. On January 24 of the same year, the United States Congress passed the Formosa Resolution authorizing the President to defend the ROC's offshore islands.[68] The First Taiwan Straits crisis ended in March 1955 when the PLA ceased its bombardment. The crisis was brought to a close during the Bandung conference.[68]

The Second Taiwan Strait Crisis began on 23 August 1958 with air and naval engagements between PRC and ROC forces, leading to intense artillery bombardment of Quemoy (by the PRC) and Amoy (by the ROC), and ended on November of the same year.[68] PLA patrol boats blockaded the islands from ROC supply ships. Though the US rejected Chiang Kai-shek's proposal to bomb mainland China artillery batteries, it quickly moved to supply fighter jets and anti-aircraft missiles to the ROC. It also provided amphibious assault ships to land supplies, as a sunken ROC naval vessel was blocking the harbor. On September 7 the US escorted a convoy of ROC supply ships and the PRC refrained from firing.

The Third Taiwan Strait Crisis in 1995–96 escalated tensions between both sides when the PRC tested a series of missiles not far from Taiwan, although, arguably, Beijing ran the test to shift the 1996 presidential election vote in favor of the KMT, already facing a challenge from the opposition Democratic Progressive Party which did not agree with the "One China Policy" shared by the CPC and KMT.[69]

Political fallout

On 25 October 1971, the United Nations General Assembly admitted the PRC and expelled the ROC, which had been a founding member of the United Nations and was one of the five permanent members of the Security Council. Representatives of Chiang Kai-shek refused to recognise their accreditations as representatives of China and left the assembly. Recognition for the People's Republic of China soon followed from most other member nations, including the United States.[70]

By 1984 PRC and ROC began to de-escalate their diplomatic relations with each other, and cross-straits trade and investment has been growing ever since. The state of war was officially declared over by the ROC in 1991.[71] Despite the end of the hostilities, the two sides have never signed any agreement or treaty to officially end the war. According to Mao Zedong, there were three ways of "staving off imperialist intervention in the short term" during the continuation of the Chinese Revolution. The first was through a rapid completion of the military takeover of the country, and through showing determination and strength against "foreign attempts at challenging the new regime along its borders." The second was by "formalising a comprehensive military alliance with the Soviet Union," which would dedicate Soviet power to directly defending China against its enemies; this aspect became extensively significant given the backdrop of the start of the Cold War. And finally the regime had to "root out its domestic opponents : the heads of secret societies, religious sects, independent unions, or tribal and ethnic organisations." By destroying the basis of domestic reaction, Mao believed a safer world for the Chinese revolution to spread in would come into existence.[72]

Under the new ROC president Lee Teng-hui, the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion was renounced in May 1991, thus ending the chances of the Kuomintang's conquest to retake the mainland.

With the election in 2000 of Democratic Progressive Party candidate Chen Shui-bian, a party other than the KMT gained the presidency for the first time in Taiwan. The new president did not share the Chinese nationalist ideology of the KMT and CPC. This led to tension between the two sides, although trade and other ties such as the 2005 Pan-Blue visit continued to increase.

With the election of President Ma Ying-jeou (KMT) in 2008, significant warming of relations resumed between Taipei and Beijing, with high-level exchanges between the semi-official diplomatic organizations of both states such as the Chen-Chiang summit series. Although the Taiwan Strait remains a potential flash point, regular direct air links were established in 2009.[11][page needed]

Reasons for the Communist victory

Historian Odd Arne Westad says the Communists won the Civil War because they made fewer military mistakes than Chiang Kai-shek and also because in his search for a powerful centralized government, Chiang antagonized too many interest groups in China. Furthermore, his party was weakened in the war against the Japanese. Meanwhile, the Communists targeted different groups, such as peasants, and brought them to its corner.[73]

Chiang wrote in his diary in June 1948: "After the fall of Kaifeng our conditions worsened and became more serious. I now realized that the main reason our nation has collapsed, time after time throughout our history, was not because of superior power used by our external enemies, but because of disintegration and rot from within."[74]

The USSR generally supported Chiang's forces. Stalin distrusted Mao, tried to block him from leadership as late as 1942, and worried that Mao would become an independent rival force in world communism.[75]

Strong American support for the Nationalists was hedged with the failure of the Marshall Mission, and then stopped completely mainly because of KMT corruption[76] (such as the notorious Yangtze Development Corporation controlled by H.H. Kung and T. V. Soong's family)[77][78] and KMT's military setback in Northeast China.

Communist land reform policy promised poor peasants farmland from their landlords, ensuring popular support for the PLA.

The main advantage of the Chinese Communist Party was the "extraordinary cohesion" within the top level of its leadership. These skills were not only secured from defections that came about during difficult times but also coupled with "communications and top level debates over tactics." The charismatic style of leadership of Mao Zedong created a "unity of purpose" and a "unity of command" which the KMT lacked. Apart from that the CPC had mastered the manipulation of local politics to their benefit; this was also derived from their propaganda skills that had also been decentralised successfully. By "portraying their opponents as enemies of all groups of Chinese" and itself as "defenders of the nation" and people (given the backdrop of the war with Japan).[79]

In the Chinese Civil War after 1945, the economy in the ROC areas collapsed because of hyperinflation and the failure of price controls by the ROC government and financial reforms; the Gold Yuan devaluated sharply in late 1948[80] and resulted in the ROC government losing the support of the cities' middle classes. In the meantime, the Communists continued their relentless land reform (land redistribution) programs to win the support of the population in the countryside.

Course of the war

Chinese Civil War (first phase, 1927–1937)

|

Second Sino-Japanese War, 1931–45

Chinese Civil War (second phase, 1945–49) and aftermath

Conflicts in the Chinese Civil War in the post-World War II era are listed chronologically by the starting dates.

1945

- July 21 – August 8 – Yetaishan Campaign

- August 13–19 – Southern Jiangsu Campaign

- August 13–16 – Counteroffensive in Eastern Hubei

- August 15–23 – Battle of Baoying

- August 16–19 – Battle of Yongjiazhen

- August 17–27 – Battle of Tianmen

- August 17–25 – Pingyu Campaign

- August 17 – September 11 – Linyi Campaign

- August 24 – Battle of Wuhe

- August 26–27 – Battle of Yinji

- August 26 – September 22 – Huaiyin-Huai'an Campaign

- August 29 – September 1 – Xinghua Campaign

- September 1–13 – Battle of Dazhongji

- September 4–5 – Battle of Lingbi

- September 5–8 – Zhucheng Campaign

- September 5–22 – Shanghe Campaign

- September 6–9 – Battle of Lishi

- September 7–10 – Pingdu Campaign

- September 8–12 – Taixing Campaign

- September 10 – October 12 – Shangdang Campaign

- September 13–17 – Wuli Campaign

- September 18 – Battle of Xiangshuikou

- September 21 – Battle of Rugao

- September 29 – November 2 – Weixian-Guangling-Nuanquan Campaign

- October – Battle of Shicun

- October 3 – November 10 – Yancheng Campaign

- October 17 – December 14 – Tongbai Campaign

- October 18 – Battle of Houmajia

- October 22 – November 2 – Handan Campaign

- October 25 – November 16 – Battle of Shanhai Pass

- October 26–30 – Campaign along the Datong-Puzhou Railway

- November – April, 1947 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Northeast China

- November 3–4 – Battle of Jiehezhen

- December 19–21 – Battle of Shaobo

- December 19–26 – Gaoyou-Shaobo Campaign

- December 21–30 – Battle of Tangtou-Guocun

1946

- January 19–26 – Houma Campaign

- March 15–17 – Battle of Siping

- April 10–15 – Jinjiatun Campaign

- April 17 – May 19 – Campaign to Defend Siping

- June 22 – August 31 – Campaign of the North China Plain Pocket

- June 12 – September 1 – Campaign along the Southern Section of Datong-Puzhou Railway

- July 31 – September 16 – Datong-Jining Campaign

- August 10–22 – Longhai Campaign

- August 14 – September 1 – Datong-Puzhou Campaign

- August 21 – September 22 – Battle of Huaiyin-Huai'an

- August 25 – August – Battle of Rugao-Huangqiao

- September 2–8 – Dingtao Campaign

- September 22–24 – Linfen-Fushan Campaign

- October 10–20 – Battle of Kalgan

- November 10–11 – Battle of Nanluo-Beiluo

- November 22 – January 1, 1947 – Lüliang Campaign

- December 17 – April 1, 1947 – Linjiang Campaign

- December 31 – January 30, 1947 – Battle of Guanzhong

- Pei-ta-shan Incident

1947

- January 21–28 – Campaign to the South of Baoding

- April 24–25 – Battle of Niangziguan

- April 27–28 – Battle of Tang'erli

- May 13–16 – Menglianggu Campaign

- May 13 – July 1 – Summer Offensive of 1947 in Northeast China

- May 28–31 – Heshui Campaign

- June 11 – March 13, 1948 – Siping Campaign

- June 26 – July 6 – Campaign to the North of Baoding

- July 17–29 – Nanma-Linqu Campaign

- August 13–18 – Meridian Ridge Campaign

- September 2–12 – Campaign to the North of Daqing River

- September 14 – November 5 – Autumn Offensive of 1947 in Northeast China

- October 2–10 – Sahe Mountain Campaign

- October 29 – November 25 – Campaign in the Eastern Foothills of the Funiu Mountains

- December 15 – March 15, 1948 – Winter Offensive of 1947 in Northeast China

- December 7–9 – Battle of Phoenix Peak

- December 9 – June 15, 1948 – Western Tai'an Campaign

- December 11 – January, 1948 – Counter-Eradication Campaign in Dabieshan

- December 20 – June 1948 – Jing Shan-Zhongxiang Campaign

1948

- January 2–7 – Gongzhutun Campaign

- March 7 – May 18 – Linfen Campaign

- March 11–21 – Zhoucun-Zhangdian Campaign

- May 12 – June 25 – Hebei-Rehe-Chahar Campaign

- May 23 – October 19 – Siege of Changchun

- May 29 – July 18 – Yanzhou Campaign

- June 17–19 – Battle of Shangcai

- September 12 – November 12 – Liaoshen Campaign

- October 5 – April 24, 1949 – Taiyuan Campaign

- October 7–15 – Battle of Jinzhou

- October 10–15 – Battle of Tashan

- November 6 – January 10, 1949 – Huaihai Campaign

- November 15 – January 11, 1949 – Battle of Jiulianshan

- November 22 – December 15 – Shuangduiji Campaign

- November 29 – January 31, 1949 – Pingjin Campaign

- 1946–1948 – Battle of Baitag Bogd

1949

- January 3–15 – Tianjin Campaign

- April – June, 1950 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Northern China

- April – June, 1953 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Central and Southern China

- May 12 – June 2 – Shanghai Campaign

- May 17 – June 16 – Xianyang Campaign

- August 9–27 – Lanzhou Campaign

- August 9 – December, 1953 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Eastern China

- August 24 – September, 1951 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Fujian

- September 5–24 – Ningxia Campaign

- September 5 – March, 1950 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Dabieshan

- October 25–27 – Battle of Guningtou

- November–July, 1953 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Northwestern China

- November 1–28 – Campaign to the North of Nanchuan County

- November 3–5 – Battle of Dengbu Island

- November 17 – December 1 – Bobai Campaign

- December 3–26 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Lianyang

- December 6–7 – Battle of Liangjiashui

- December 7–14 – Battle of Lianyang

- December 17–18 – Battle of Jianmenguan

1950

- January – June, 1955 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Wuping

- January 15 – May 1951 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Guangxi

- January 19–31 – Battle of Bamianshan

- February – December 1953 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Southwestern China

- February 4 – December – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Longquan

- February 14–20 – Battle of Tianquan

- March 3 – Battle of Nan'ao Island

- March 5 – May 1 – Landing Operation on Hainan Island

- March 29 – May 7 – Battle of Yiwu

- May 11 – Battle of Dongshan Island

- May 25– August 7 – Wanshan Archipelago Campaign

- August 9 – Battle of Nanpéng Island

- September – January, 1951 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Northern Guangdong

- September 22 – November 29 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in northeastern Guizhou

- October 15 – November – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in the Border Region of Hunan–Hubei–Sichuan

- October 15 – December – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Western Hunan

- December 13 – February, 1951 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Shiwandashan

- December 20 – February, 1951 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Liuwandashan

1950–58

1951

- January 8 – February – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Yaoshan

- April 15 – September – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Western Guangxi

1952

- April 11–15 – Battle of Nanri Island

- June 13 – September 20 – Campaign to Suppress Bandits in Heishui

- September 20 – October 20 – Battle of Nanpēng Archipelago

1953

- May 29 – Battle of Dalushan Islands

- July 16–18 – Dongshan Island Campaign

1955

- January 18–20 – Battle of Yijiangshan Islands

- January 19 – February 26 – Battle of Dachen Archipelago

1960

- November 14 – February 9, 1961 – Campaign at the China-Burma Border

Atrocities

During the war both the Nationalists and Communists carried out mass atrocities, with millions of non-combatants deliberately killed by both sides.[81] Benjamin Valentino has estimated atrocities in the Chinese Civil War resulted in the death of between 1.8 million and 3.5 million people between 1927 and 1949.[82][better source needed]

Communist atrocities

During the Siege of Changchun the People's Liberation Army implemented a military blockade on the neutral[83] city of Changung and prevented civilians from leaving the city during the blockade;[84] this blockade caused the starvation of tens[84] to 150[85] thousand civilians. The PLA continued to use siege tactics throughout Northeast China.[83]

At the outbreak of the Chinese Civil War in 1946, Mao Zedong began to push for a return to radical policies to mobilize China against the Landlord class, but protected the rights of middle peasants and specified that rich peasants were not landlords.[86] The July 7 Directive of 1946 set off eighteen months of fierce conflict in which all rich peasant and landlord property of all types was to be confiscated and redistributed to poor peasants. Party work teams went quickly from village to village and divided the population into landlords, rich, middle, poor, and landless peasants. Because the work teams did not involve villagers in the process, however, rich and middle peasants quickly returned to power. [87] The Outline Land Law of October 1947 increased the pressure.[88] Those condemned as landlords were buried alive, dismembered, strangled and shot.[89]

Kuomintang atrocities

In response to the aforementioned Land reform campaign; the Kuomintang helped establish the "Huanxiang Tuan" (還鄉團), or Homecoming Legion, which was composed of landlords who sought the return of their redistributed land and property from peasants and CCP guerrillas, as well as forcibly conscripted peasants and communist POWs.[90] The Homecoming legion conducted its guerrilla warfare campaign against CCP forces and purported collaborators up until the end of the civil war in 1949.[90] The Kuomintang killed 1,131,000[91] soldiers before entering combat during its conscription campaigns. In addition, the Kuomintang faction massacred 1 million civilians.[91]

See also

Notes

- ^ The conflict did not have an official end date. However, historians generally agree that the war subsided after the People's Republic of China took the Mosquito Tail Islet, the last island held by the Republic of China in the Wanshan Archipelago.[3]

References

- ^ a b c China at War: An Encyclopedia. 2012. p. 295.

- ^ "China". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 15 November 2012.

- ^ Westad, Odd (2003). Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946–1950. Stanford University Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-8047-4484-3.

- ^ Èëãñèõ±¨

- ^ a b c Hsiung, James C. (1992). China's Bitter Victory: The War With Japan, 1937–1945. New York: M. E. Sharpe publishing. ISBN 1-56324-246-X.

- ^ a b c Lynch, Michael (2010). The Chinese Civil War 1945–49. Osprey Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-84176-671-3.

- ^ http://necrometrics.com/20c1m.htm#Nationalist

- ^ http://necrometrics.com/20c1m.htm#Chinese

- ^ Lew, Christopher R.; Leung, Pak-Wah, eds. (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Civil War. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 3. ISBN 978-0810878730.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Green, Leslie C. The Contemporary Law of Armed Conflict. p. 79.

- ^ a b So, Alvin Y.; Lin, Nan; Poston, Dudley, eds. (July 2001). The Chinese Triangle of Mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong: Comparative Institutional Analyses. Contributions in Sociology. Vol. 133. Westport, CT; London: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30869-7. ISSN 0084-9278. OCLC 45248282.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|subscription=,|registration=, and|last-author-amp=(help) - ^ a b c March, G. Patrick. Eastern Destiny: Russia in Asia and the North Pacific. [1996] (1996). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-95566-4. p. 205.

- ^ a b c H.H. Chang, Chiang Kai Shek – Asia's Man of Destiny (Doubleday, 1944; reprint 2007 ISBN 1-4067-5818-3. p. 126.

- ^ Ho, Alfred K. Ho, Alfred Kuo-liang. [2004] (2004). China's Reforms and Reformers. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-96080-3. pg 7.

- ^ a b c Fairbank, John King. [1994] (1994). China: A New History. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-11673-9.

- ^ Kuhn, Robert (2005). The man who changed China: the life and legacy of Jiang Zemin. Crown Publishers.

- ^ Zedong, Mao. Thompson, Roger R. [1990] (1990). Report from Xunwu. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2182-3.

- ^ Brune, Lester H. Dean Burns, Richard Dean Burns. [2003] (2003). Chronological History of U.S. Foreign Relations. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93914-3.

- ^ Zhao, Suisheng. [2004] (2004). A Nation-state by Construction: Dynamics of Modern Chinese Nationalism. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-5001-7.

- ^ Guo, Xuezhi. [2002] (2002). The Ideal Chinese Political Leader: A Historical and Cultural Perspective. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-97259-3.

- ^ Theodore De Bary, William. Bloom, Irene. Chan, Wing-tsit. Adler, Joseph. Lufrano Richard. Lufrano, John. [1999] (1999). Sources of Chinese Tradition. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10938-5. p. 328.

- ^ a b c Lee, Lai to. Trade Unions in China: 1949 To the Present. [1986] (1986). National University of Singapore Press. ISBN 9971-69-093-4.

- ^ Blasko, Dennis J. [2006] (2006). The Chinese Army Today: Tradition and Transformation for the 21st Century. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-77003-3.

- ^ Esherick, Joseph. (2000). Remaking the Chinese City: Modernity and National Identity, 1900–1950. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2518-7.

- ^ Clark, Anne, Klein, Donald. eds. (1971). Biographic Dictionary of Chinese Communism (Harvard University Press), p. 134.

- ^ Lynch, Michael Lynch. Clausen, Søren. [2003] (2003). Mao. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21577-3.

- ^ a b Manwaring, Max G. Joes, Anthony James. [2000] (2000). Beyond Declaring Victory and Coming Home: The Challenges of Peace and Stability operations. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-96768-9. p. 58.

- ^ a b Zhang, Chunhou. Vaughan, C. Edwin. [2002] (2002). Mao Zedong as Poet and Revolutionary Leader: Social and Historical Perspectives. Lexington books. ISBN 0-7391-0406-3. pp. 58, 65.

- ^ Bianco, Lucien. Bell, Muriel. [1971] (1971). Origins of the Chinese Revolution, 1915–1949. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0827-4. p. 68.

- ^ Lin, Hsiao-ting (2010). Modern China's Ethnic Frontiers: A Kourney to the West. Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia. Vol. Volume 67 (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 52. ISBN 0-415-58264-4. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

A force of about 300 soldiers was organized and augmented by recruiting local Khampa bandits into the army. The relationship between the Consolatory Commission and Liu Wenhui seriously deteriorated in early 1936, when the Norla Hutuktu

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Ye, Zhaoyan Ye, Berry, Michael. [2003] (2003). Nanjing 1937: A Love Story. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12754-5.

- ^ a b c Buss, Claude Albert. [1972] (1972). Stanford Alumni Association. The People's Republic of China and Richard Nixon. United States.

- ^ a b Schoppa, R. Keith. [2000] (2000). The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11276-9.

- ^ Chen, Jian. [2001] (2001). Mao's China and the Cold War. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-807-84932-4.

- ^ Lary, Diana. [2007] (2007). China's Republic. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84256-5.

- ^ a b Zarrow, Peter Gue. (2005). China in War and Revolution, 1895–1949. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36447-7. p. 338.

- ^ a b Xu, Guangqiu. [2001] (2001). War Wings: The United States and Chinese Military Aviation, 1929–1949. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32004-7. p. 201.

- ^ Bright, Richard Carl. [2007] (2007). Pain and Purpose in the Pacific: True Reports of War. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-4251-2544-1.

- ^ a b Lilley, James. China hands: nine decades of adventure, espionage, and diplomacy in Asia. PublicAffairs, New York, 2004

- ^ a b Jessup, John E. (1989). A Chronology of Conflict and Resolution, 1945–1985. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-24308-5.

- ^ Yang Kuisong (2011-11-24). 杨奎松《读史求实》:苏联给了林彪东北野战军多少现代武器. Sina Books. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved May 17, 2013.

- ^ Hu, Jubin. (2003). Projecting a Nation: Chinese National Cinema Before 1949. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-610-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Nguyễn Anh Thái (chief author); Nguyễn Quốc Hùng; Vũ Ngọc Oanh; Trần Thị Vinh; Đặng Thanh Toán; Đỗ Thanh Bình (2002). Lịch sử thế giới hiện đại (in Vietnamese). Ho Chi Minh City: Giáo Dục Publisher. pp. 320–322. 8934980082317.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Michael M Sheng, Battling Western Imperialism, Princeton University Press, 1997, p.132 – 135

- ^ Liu, Shiao Tang (1978). Min Kuo Ta Shih Jih Chih. Vol. 2. Taipei: Zhuan Chi Wen Shuan. p. 735.

- ^ New York Times, 12 January 1947, p44.

- ^ Zeng Kelin, Zeng Kelin jianjun zishu (General Zeng Kelin Tells his story), Liaoning renmin chubanshe, Shenyang, 1997. pp. 112–113

- ^ Ray Huang, cong dalishi jiaodu du Jiang Jieshi riji (Reading Chiang Kai-shek's diary from a macro-history perspective), China Times Publishing Press, Taipei, 1994, pp. 441–443

- ^ Lung Ying-tai, dajiang dahai 1949, Commonwealth Publishing Press, Taipei, 2009, p.184

- ^ Harry S.Truman, Memoirs, Vol. Two: Years of Trial and Hope, 1946–1953 (Great Britain 1956), p.66

- ^ p23, U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II, William Blum, Zed Books 2004 London.

- ^ Lilley, James R. China Hands: Nine Decades of Adventure, Espionage, and Diplomacy in Asia. ISBN 1-58648-136-3.

- ^ a b c Westad, Odd Arne. [2003] (2003). Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946–1950. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4484-X. pp. 192–193.

- ^ Pomfret, John. Red Army Starved 150,000 Chinese Civilians, Books Says. Associated Press; The Seattle Times. 2009-10-02. URL:http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19901122&slug=1105487. Accessed: 2009-10-02. (Archived by WebCite at https://www.webcitation.org/5kEN5bTlE?url=http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date%3D19901122%26slug%3D1105487

- ^ a b Elleman, Bruce A. Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795–1989. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21473-4.

- ^ a b c Finkelstein, David Michael. Ryan, Mark A. McDevitt, Michael. [2003] (2003). Chinese Warfighting: The PLA Experience Since 1949. M.E. Sharpe. China. ISBN 0-7656-1088-4. p. 63.

- ^ Donggil Kim, "Stalin and the Chinese Civil War." Cold War History 10.2 (2010): 185–202.

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 215. ISBN 0-521-25514-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 225. ISBN 0-521-25514-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Hsiao-ting Lin (2010). Modern China's ethnic frontiers: a journey to the west. Vol. Volume 67 of Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 117. ISBN 0-415-58264-4. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

China's far northwest.23 A simultaneous proposal suggested that, with the support of the new Panchen Lama and his entourage, at least three army divisions of anti-Communist Khampa Tibetans could be mustered in southwest China.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Hsiao-ting Lin (2010). Modern China's ethnic frontiers: a journey to the west. Vol. Volume 67 of Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. xxi. ISBN 0-415-58264-4. Retrieved 2011-12-27.

(tusi) from the Sichuan-Qinghai border; and Su Yonghe, a Khampa native-chieftain from Nagchuka on the Qinghai- Tibetan border. According to Nationalist intelligence reports, these leaders altogether commanded about 80000 irregulars.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Cook, Chris Cook. Stevenson, John. [2005] (2005). The Routledge Companion to World History Since 1914. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-34584-7. p. 376.

- ^ Qi, Bangyuan. Wang, Dewei. Wang, David Der-wei. [2003] (2003). The Last of the Whampoa Breed: Stories of the Chinese Diaspora. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13002-3. p. 2.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Roderick. Fairbank, John K. Twitchett, Denis C. [1991] (1991). The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24337-8. p. 820.

- ^ "The History of the Chinese People's Liberation Army." Beijing: People's Liberation Army Press. 1983.

- ^ "Harry S Truman, "Statement on Formosa," January 5, 1950". University of Southern California. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ Bush, Richard C. (2005). Untying the Knot: Making Peace in the Taiwan Strait. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-1288-X

- ^ a b c d e Tsang, Steve Yui-Sang Tsang. The Cold War's Odd Couple: The Unintended Partnership Between the Republic of China and the UK, 1950–1958. (2006). I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-842-0. pp. 155, 115–120, 139–145

- ^ Alison Behnke (1 January 2007). Taiwan in Pictures. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-7148-3.

- ^ "People's Republic of China In, Taiwan Out, at U.N." The Learning Network. 2011-10-25. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- ^ "Taiwan flashpoint". BBC News. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Decisive Encounters By Westad, Odd Arne. Stanford University Press, 21 Mar. pp. 292–297 2003 (Google Books).

- ^ Odd Arne Westad, Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750 (2012) p. 291.

- ^ Trei, Lisa (2005-03-09). "Hoover's new archival acquisitions shed light on Chinese history". Stanford University. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- ^ Rappaport, Helen (1999). Joseph Stalin: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. p. 36.

- ^ Sun, Tung-hsun (1982). "Some Recent American Interpretations of Sino-American Relations of the Late 1940s: An Assessment" (PDF). Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

- ^ T.V. Soong – A Register of His Papers in the Hoover Institution Archives media.hoover.org

- ^ 轉載: 杜月笙的1931 (6) – 五湖煙景的日誌 – 倍可親. big5.backchina.com (in Traditional Chinese). Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- ^ For quotes see Odd Arne Westad (2003). Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946–1950. Stanford University Press. pp. 9–11.

- ^ http://www.mof.gov.tw/museum/ct.asp?xItem=3682&ctNode=34

- ^ Rummel, Rudolph (1994), Death by Government.

- ^ Valentino, Benjamin A. Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the Twentieth Century. Cornell University Press. December 8, 2005. p88

- ^ a b Lary, Diana (2015). China's Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1107054672.

- ^ a b Koga, Yukiko (2016). Inheritance of Loss: China, Japan, and the Political Economy of Redemption After Empire. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 022641213X.

- ^ "Pomfret, John (October 2, 2009). "Red Army Starved 150,000 Chinese Civilians, Books Says". Associated Press. The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved October 2, 2009".

- ^ DeMare, Brian James (2019). Land Wars: The Story of China's Agrarian Revolution. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1503609525.

- ^ Tanner (2015), pp. 134–135.

- ^ Saich The Rise to Power of the Chinese Communist Party Outline Land Law of 1947

- ^ Scheidel, Walter (2017). The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-691-16502-8.

- ^ a b Liu, Zaiyu (2002). 第二次國共戰爭時期的還鄉團 (PDF). Hong Kong: Twenty First Century Bimonthly.

- ^ a b R.J.Rummel. "China's Bloody CENTURY".

Further reading

- Cheng, Victor Shiu Chiang. "Imagining China’s Madrid in Manchuria: The Communist Military Strategy at the Onset of the Chinese Civil War, 1945–1946." Modern China 31.1 (2005): 72–114.

- Chesneaux, Jean, Francoise Le Barbier, and Claire Bergere. China from the 1911 Revolution to Liberation. (1977).

- Chi, Hsi-sheng. Nationalist China at War: Military Defeats and Political Collapse, 1937–45 (U of Michigan Press, 1982).

- Dreyer, Edward L. China at War 1901–1949 (Routledge, 2014).

- Dupuy, Trevor N. The Military History of the Chinese Civil War (Franklin Watts, Inc., 1969).

- Eastman, Lloyd E. "Who lost China? Chiang Kai-shek testifies." China Quarterly 88 (1981): 658–668.

- Eastman, Lloyd E., et al. The Nationalist Era in China, 1927–1949 (Cambridge UP, 1991).

- Fenby, Jonathan. Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the China He Lost (2003).

- Ferlanti, Federica. "The New Life Movement at War: Wartime Mobilisation and State Control in Chongqing and Chengdu, 1938—1942" European Journal of East Asian Studies 11#2 (2012), pp. 187–212 online how Nationalist forces mobilized society

- Jian, Chen. "The Myth of America's “Lost Chance” in China: A Chinese Perspective in Light of New Evidence." Diplomatic History 21.1 (1997): 77–86.

- Lary, Diana. China's Civil War: A Social History, 1945–1949 (Cambridge UP, 2015). excerpt

- Levine, Steven I. "A new look at American mediation in the Chinese civil war: the Marshall mission and Manchuria." Diplomatic History 3.4 (1979): 349–376.

- Lew, Christopher R. The Third Chinese Revolutionary Civil War, 1945–49: An Analysis of Communist Strategy and Leadership (Routledge, 2009).

- Li, Xiaobing. China at War: An Encyclopedia (ABC-CLIO, 2012).

- Lynch, Michael. The Chinese Civil War 1945–49 (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014).

- Mitter, Rana. "Research Note Changed by War: The Changing Historiography Of Wartime China and New Interpretations Of Modern Chinese History." Chinese Historical Review 17.1 (2010): 85–95.

- Nasca, David S. Western Influence on the Chinese National Revolutionary Army from 1925 to 1937. (Marine Corps Command And Staff Coll Quantico Va, 2013). online

- Pepper, Suzanne. Civil war in China: the political struggle 1945–1949 (Rowman & Littlefield, 1999).

- Reilly, Major Thomas P. Mao Tse-Tung And Operational Art During The Chinese Civil War (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2015) online.

- Shen, Zhihua, and Yafeng Xia. Mao and the Sino–Soviet Partnership, 1945–1959: A New History. (Lexington Books, 2015).

- Tanner, Harold M. Where Chiang Kai-shek Lost China: The Liao-Shen Campaign, 1948 (2015) excerpt, advanced military history

- Taylor, Jeremy E., and Grace C. Huang. "'Deep changes in interpretive currents'? Chiang Kai-shek studies in the post-cold war era." International Journal of Asian Studies 9.1 (2012): 99–121.

- Taylor, Jay. The Generalissimo (Harvard University Press, 2009). biography of Chiang Kai-shek

- Van de Ven, Hans. War and nationalism in China: 1925–1945 (Routledge, 2003).

- Westad, Odd Arne (2003). Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946–1950. Stanford University Press.

- Wilson, Dick. Chou: the story of Zhou Enlai, 1898–1976 (Hutchinson Radius, 1984).

- Yick, Joseph K.S. Making Urban Revolution in China: The CCP-GMD Struggle for Beiping-Tianjin, 1945–49 (Routledge, 2015).

External links

- Summary of Chinese Civil War 1946–1949

- Chinese Civil War 1945–1950

- "Armored Car Like Oil Tanker Used by Chinese" Popular Mechanics, March 1930 article and photo of armoured train of Chinese Civil War

- Topographic maps of China Series L500, U.S. Army Map Service, 1954–

- Operational Art in the Chinese PLA’s Huai Hai Campaign

- Postal Stamps of the Chinese Post-Civil War Era

- Chinese Civil War

- Revolutions in China

- Wars involving the Republic of China

- Wars involving the People's Republic of China

- Interwar period

- Revolution-based civil wars

- Communism-based civil wars

- Wars of independence

- Aftermath of World War II

- Military history of the Republic of China

- Republic of China (1912–1949)

- Proxy wars

- 20th-century conflicts

- Cross-Strait conflict