Human overpopulation

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Human overpopulation (or human population overshoot) refers to a human population that is too large to be sustained by its environment in the long term. The idea is usually discussed in the context of world population, though it may also concern regions. Human population growth has in recent centuries become exponential due to changes in technology that reduce mortality. Experts concerned by this trend argue that it results in a level of resource consumption which exceeds the environment's carrying capacity, leading to population overshoot. The subject is often discussed in relation to other population concerns such as demographic push, depopulation, ecological or societal collapse, and human extinction.

Human overpopulation as a scholarly concern was popularized by Paul Ehrlich in his book The Population Bomb. Ehrlich describes overpopulation as a function of overconsumption,[1] arguing that overpopulation should be defined by depletion of non-renewable resources. Under this definition, changes in lifestyle could cause an overpopulated area to no longer be overpopulated without any reduction in population, or vice versa.[2][3][4] Proponents of human overpopulation suggest that contemporary human caused environmental issues (such as global warming and biodiversity loss) are signs that human world population is in a state of overpopulation.

Discussion of overpopulation follow a similar line of inquiry as Malthusianism and its Malthusian catastrophe,[5][6] a hypothetical event where population exceeds agricultural capacity, causing famine or war over resources, resulting in poverty and depopulation. Critics of human overpopulation as an approach to policy or scholarship highlight how attempts to blame environmental issues on overpopulation tend to oversimplify complex social or economic systems, placing blame on developing countries and poor populations rather than developed countries who are responsible for environmental issues like climate change —reinscribing colonial or racist assumptions.[7][6] These issues often lead human overpopulation arguments to be central features of ecofascist ideologies and rhetoric.[8][9] Other critics highlight that proponents rely too much on assumptions of resource scarcity and ignoring other processes such as technological innovation.

History of concept

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2021) |

Concerns about population size or density have a long history: Tertullian, a resident of the city of Carthage in the second century CE, criticized population at the time saying "Our numbers are burdensome to the world, which can hardly support us... In very deed, pestilence, and famine, and wars, and earthquakes have to be regarded as a remedy for nations, as the means of pruning the luxuriance of the human race." Other philosophers also explore the topic, such as Plato and Aristotle .[10] Despite these concerns, scholars have not found historic societies which have collapsed because of overpopulation or overconsumption.[11] This could be because, prior to modern medicine, infectious diseases prevented populations from growing too large.

By the beginning of the 19th century, intellectuals such as Thomas Malthus predicted that humankind would outgrow its available resources because a finite amount of land would be incapable of supporting a population with limitless potential for increase.[12] During the 19th century, Malthus' work was often interpreted in a way that blamed the poor alone for their condition and helping them was said to worsen conditions in the long run.[13] This resulted, for example, in the English poor laws of 1834[13] and a hesitating response to the Irish Great Famine of 1845–52.[14]

As scholars became aware of environmental issues facing humanity during the end of the 20th century, a number of different types of experts have looked to population growth as a root cause. The consensus projections for population growth are that current populations of 7 billion will approach 9 billion and "level off or probably decline."[15] In 2017, more than one-third of 50 Nobel prize-winning scientists surveyed by the Times Higher Education at the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings said that human overpopulation and environmental degradation are the two greatest threats facing humankind.[16] In November that same year, a statement by 15,364 scientists from 184 countries indicated that rapid human population growth is the "primary driver behind many ecological and even societal threats."[17] In 2019, a warning on climate change signed by 11,000 scientists from 153 nations said that human population growth adds 80 million humans annually, and "the world population must be stabilized—and, ideally, gradually reduced—within a framework that ensures social integrity" to reduce the impact of "population growth on GHG emissions and biodiversity loss."[18][19]

Global population dynamics, their history and factors

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. Specifically, This information is already in World Population and other articles unccessary. (January 2021) |

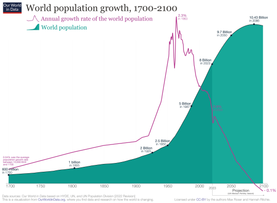

World population has been rising continuously since the end of the Black Death, around the year 1350.[20] The fastest doubling of the world population happened between 1950 and 1986: a doubling from 2.5 to 5 billion people in just 37 years, [21] mainly due to medical advancements and increases in agricultural productivity.[22][23]

Due to its dramatic impact on the human ability to grow food, the Haber process served as the "detonator of the population explosion," enabling the global population to increase from 1.6 billion in 1900 to 7.7 billion by November 2018.[24]

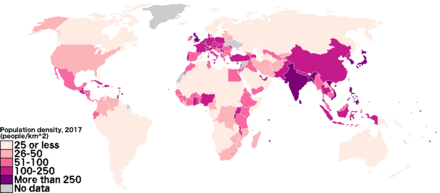

The rate of population growth has been declining since the 1980s, while the absolute total numbers are still increasing. Recent rate increases in several countries[where?] previously enjoying steady declines have apparently been contributing to continued growth in total numbers.[citation needed] The United Nations has expressed concerns on continued population growth in sub-Saharan Africa.[25] Recent research has demonstrated that those concerns are well grounded.[26][27][28]

History of world population

| Population[25] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Billion | ||

| 1804 | 1 | ||

| 1927 | 2 | ||

| 1959 | 3 | ||

| 1974 | 4 | ||

| 1987 | 5 | ||

| 1999 | 6 | ||

| 2011 | 7 | ||

| 2021 | 7.8[29] | ||

World population has gone through a number of periods of growth since the dawn of civilization in the Holocene period, around 10,000 BCE. The beginning of civilization roughly coincides with the receding of glacial ice following the end of the last glacial period.[30]

It is estimated that between 1–5 million people, subsisting on hunting and foraging, inhabited the Earth in the period before the Neolithic Revolution, when human activity shifted away from hunter-gathering and towards very primitive farming.[31]

Farming allowed for the growth of populations in many parts of the world, including Europe, the Americas and China through the 1600s, occasionally disrupted by plagues or other crisis.[32][33] For example, the Black Death is thought to have reduced the world's population, then at an estimated 450 million, to between 350 and 375 million by 1400.[34] The population of Europe stood at over 70 million in 1340;[35] these levels did not return until 200 years later.[36] In other parts of the globe, China's population census at the founding of the Ming dynasty in 1368 indicated that the population stood close to 60 million, (though these figures are debated by some historians) approaching 150 million by the end of the dynasty in 1644.[37][38] The population of the Americas in 1500 may have been between 50 and 100 million.[39] Encounters between European explorers and other populations introduced local epidemics or other violence: for example, 90% of the Native American population of the New World through Old World diseases such as smallpox, measles, and influenza,[40] or the slave trade in Africa greatly damaged populations.[41]

After the start of the Industrial Revolution, during the 18th century, the rate of population growth began to increase. By the end of the century, the world's population was estimated at just under 1 billion.[42] At the turn of the 20th century, the world's population was roughly 1.6 billion.[42] Dramatic growth beginning in 1950 (above 1.8% per year) coincided with greatly increased food production as a result of the industrialization of agriculture brought about by the Green Revolution.[43] The rate of human population growth peaked in 1964, at about 2.1% per year.[44] By 1940, this figure had increased to 2.3 billion.[45] Each subsequent addition of a billion humans took less and less time: 33 years to reach three billion in 1960, 14 years for four billion in 1974, 13 years for five billion in 1987, and 12 years for six billion in 1999.[46]

Causes

| External videos | |

|---|---|

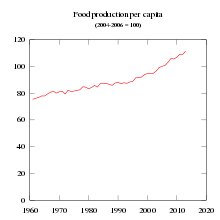

From a historical perspective, technological revolutions have coincided with population expansion. There have been three major technological revolutions—the tool-making revolution, the agricultural revolution, and the industrial revolution—all of which allowed humans more access to food; hence increasing the carrying capacity, resulting in subsequent population explosions.[47][48] For example, the use of tools, such as bow and arrow, allowed primitive hunters greater access to more high energy foods (e.g. animal meat). Similarly, the transition to farming about 10,000 years ago greatly increased the overall food supply, which was used to support more people. Food production further increased with the industrial revolution as machinery, fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides were used to increase land under cultivation as well as crop yields. Today, starvation is caused by economic and political forces rather than a lack of the means to produce food.[49][50]

Significant increases in human population occur whenever the birth rate exceeds the death rate for extended periods of time. Traditionally, the fertility rate is strongly influenced by cultural and social norms that are rather stable and therefore slow to adapt to changes in the social, technological, or environmental conditions. For example, when death rates fell during the 19th and 20th century—as a result of improved sanitation, child immunizations, and other advances in medicine—allowing more newborns to survive, the fertility rate did not adjust downward, resulting in significant population growth. For example, until the 1700s, seven out of ten children died before reaching reproductive age.[51]

Agriculture has sustained human population growth and has been the main driving factor behind it. With more food supply, the population grows with it. This occurs most in regions which are fertile and capable of higher food production in contrast to infertile regions unable to support agricultural productivity on larger or any scales at all. This dates back to prehistoric times, when agricultural methods were first developed, and continues to the present day, with fertilizers, agrochemicals, large-scale mechanization, genetic manipulation, and other technologies.[52][53][54][55]

Humans have historically exploited the environment using the easiest, most accessible resources first. The richest farmland was plowed and the richest mineral ore mined first. Anne Ehrlich, Gerardo Ceballos, and Paul Ehrlich note that overpopulation is demanding the use of ever more creative, expensive and/or environmentally destructive means in order to exploit ever more difficult to access and/or poorer quality natural resources to satisfy consumers.[56]

Population as a function of food availability

Many people from a wide range of academic fields and political backgrounds—including agronomist and insect ecologist David Pimentel,[59] behavioral scientist Russell Hopfenberg,[60] and anthropologist Virginia Abernethy[61] —propose that, like all other animal populations, human populations predictably grow and shrink according to their available food supply, growing during an abundance of food and shrinking in times of scarcity.

Proponents of this theory argue that every time food production is increased, the population grows. Most human populations throughout history validate this theory, as does the overall current global population. Populations of hunter-gatherers fluctuate in accordance with the amount of available food. The world human population began increasing after the Neolithic Revolution and its increased food supply.[62] This was, subsequent to the Green Revolution, followed by even more severely accelerated population growth, which continues today.

Critics of this theory point out that, in the modern era, birth rates are lowest in the developed nations, which also have the highest access to food. In fact, some developed countries have both a diminishing population and an abundant food supply. The United Nations projects that the population of 51 countries or areas, including Germany, Italy, Japan, and most of the states of the former Soviet Union, is expected to be lower in 2050 than in 2005.[63] This shows that, limited to the scope of the population living within a single given political boundary, particular human populations do not always grow to match the available food supply. However, the global population as a whole still grows in accordance with the total food supply and many of these wealthier countries are major exporters of food to poorer populations, so that, "it is through exports from food-rich to food-poor areas (Allaby, 1984; Pimentel et al., 1999) that the population growth in these food-poor areas is further fueled.[59]

Regardless of criticisms against the theory that population is a function of food availability, the human population is, on the global scale, undeniably increasing,[64] as is the net quantity of human food produced—a pattern that has been true for roughly 10,000 years, since the human development of agriculture. The fact that some affluent countries demonstrate negative population growth fails to discredit the theory as a whole, since the world has become a globalized system with food moving across national borders from areas of abundance to areas of scarcity. Hopfenberg and Pimentel's findings support both this[59] and Quinn's direct accusation that "First World farmers are fueling the Third World population explosion."[65]

Current population dynamics

On 14 May 2018 , the United States Census Bureau calculates 7,472,985,269 for that same date[66] and the United Nations estimated over 7 billion.[67][68][69] In 2017, the United Nations increased the medium variant projections[70] to 9.8 billion for 2050 and 11.2 billion for 2100.[71] The UN population forecast of 2017 was predicting "near end of high fertility" globally and anticipating that by 2030 over ⅔ of the world population will be living in countries with fertility below the replacement level[72] and for total world population to stabilize between 10 and 12 billion people by the year 2100.[73]

The rapid increase in world population over the past three centuries has raised concerns among some people that the planet may not be able to sustain the future or even present number of its inhabitants. The InterAcademy Panel Statement on Population Growth, circa 1994, stated that many environmental problems, such as rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, global warming, and pollution, are aggravated by the population expansion.[74]

Dangers and effects

Biologists and sociologists have discussed overpopulation as a serious threat to the quality of human life.[75][76] Some deep ecologists, such as the radical thinker and polemicist Pentti Linkola, see human overpopulation as a threat to the entire biosphere.[77]

The effects of overpopulation are compounded by overconsumption. Overpopulation does not depend only on the size or density of the population, but on the ratio of population to available sustainable resources. It also depends on how resources are managed and distributed throughout the population.[citation needed] According to Paul R. Ehrlich:

Rich western countries are now siphoning up the planet's resources and destroying its ecosystems at an unprecedented rate. We want to build highways across the Serengeti to get more rare earth minerals for our cellphones. We grab all the fish from the sea, wreck the coral reefs and put carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. We have triggered a major extinction event ... A world population of around a billion would have an overall pro-life effect. This could be supported for many millennia and sustain many more human lives in the long term compared with our current uncontrolled growth and prospect of sudden collapse ... If everyone consumed resources at the US level—which is what the world aspires to—you will need another four or five Earths. We are wrecking our planet's life support systems.[78]

However, Ehrlich's earlier predictions were controversial. In 1968 he wrote a book The Population Bomb, in which he famously stated that "[i]n the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now."[79]

Poverty, and infant and child mortality

High rates of infant mortality are associated with poverty. Rich countries with high population densities have low rates of infant mortality.[80][81] However, both global poverty and infant mortality has declined over the last 200 years of population growth.[82][83]

Environmental impacts

Overpopulation has substantially adversely impacted the environment of Earth starting at least as early as the 20th century.[76] According to the Global Footprint Network, "today humanity uses the equivalent of 1.5 planets to provide the resources we use and absorb our waste".[84] There are also economic consequences of this environmental degradation in the form of ecosystem services attrition.[85] Scientists suggest that the overall human impact on the environment during the Great Acceleration, particularly due to human population size and growth, economic growth, overconsumption, pollution, and proliferation of technology, has pushed the planet into a new geological epoch known as the Anthropocene.[86][87]

Further, even in countries which have both large population growth and major ecological problems, it is not necessarily true that curbing the population growth will make a major contribution towards resolving all environmental problems.[88]

Many studies link population growth with emissions and the effect of climate change.[89][90] The global consumption of meat is projected to rise by as much as 76% by 2050 as the global population surges to more than 9 billion, resulting in further biodiversity loss and increased GHG emissions.[91][92]

Biodiversity loss and the Holocene extinction

The Yangtze River dolphin, Atlantic gray whale, West African black rhino, Merriam's elk, California grizzly bear, silver trout, blue pike and dusky seaside sparrow are all victims of human overpopulation.

—Chris Hedges, 2009[93]

Human overpopulation, continued population growth, and overconsumption are the primary drivers of biodiversity loss and the 6th (and ongoing) mass species extinction.[94][95][96][97][98][99] Present extinction rates may be as high as 140,000 species lost per year due to human activity.[100] The Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, released by IPBES in 2019, says that human population growth is a significant factor in biodiversity loss.[101] The report asserts that expanding human land use for agriculture and overfishing are the main causes of this decline.[102] The 2020 World Wildlife Fund's Living Planet Report posits that 68% of vertebrate wildlife has been lost since 1970 due to human actions, including overconsumption, population growth, global trade and intensive farming.[103][104]

Some eminent scientists including Jared Diamond and E. O. Wilson contend that population growth is devastating to biodiversity. Wilson has suggested that when Homo sapiens reached a population of six billion their biomass exceeded that of any other large land dwelling animal species that had ever existed by over 100 times, and that "we and the rest of life cannot afford another 100 years like that."[105]

Potential ecological collapse

Ecological collapse refers to a situation where an ecosystem suffers a drastic, possibly permanent, reduction in carrying capacity for all organisms, often resulting in mass extinction. Usually, an ecological collapse is precipitated by a disastrous event occurring on a short time scale. Ecological collapse can be considered as a consequence of ecosystem collapse on the biotic elements that depended on the original ecosystem.[106][107]

The oceans are in great danger of collapse. In a study of 154 different marine fish species, David Byler came to the conclusion that many factors such as overfishing, climate change, and fast growth of fish populations will cause ecosystem collapse.[108] When humans fish, they usually will fish the populations of the higher trophic levels such as salmon and tuna. The depletion of these trophic levels allow the lower trophic level to overpopulate, or populate very rapidly. For example, when the population of catfish is depleting due to overfishing, plankton will then overpopulate because their natural predator is being killed off. This causes an issue called eutrophication. Since the population all consumes oxygen the dissolved oxygen (DO) levels will plummet. The DO levels dropping will cause all the species in that area to have to leave, or they will suffocate. This along with climate change, and ocean acidification can cause the collapse of an ecosystem.

Depletion and destruction of resources

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (January 2021) |

The resources to be considered when evaluating whether an ecological niche is overpopulated include clean water, clean air, food, shelter, warmth, and other resources necessary to sustain life. If the quality of human life is addressed, there may be additional resources considered, such as medical care, education, proper sewage treatment, waste disposal and energy supplies. Overpopulation places competitive stress on the basic life sustaining resources,[109] leading to a diminished quality of life.[76]

David Pimentel has stated that "With the imbalance growing between population numbers and vital life sustaining resources, humans must actively conserve cropland, freshwater, energy, and biological resources. There is a need to develop renewable energy resources. Humans everywhere must understand that rapid population growth damages the Earth's resources and diminishes human well-being."[110][111]

These reflect the comments also of the United States Geological Survey in their paper "The Future of Planet Earth: Scientific Challenges in the Coming Century": "As the global population continues to grow...people will place greater and greater demands on the resources of our planet, including mineral and energy resources, open space, water, and plant and animal resources." "Earth's natural wealth: an audit" by New Scientist magazine states that many of the minerals that we use for a variety of products are in danger of running out in the near future.[112] A handful of geologists around the world have calculated the costs of new technologies in terms of the materials they use and the implications of their spreading to the developing world. All agree that the planet's booming population and rising standards of living are set to put unprecedented demands on the materials that only Earth itself can provide.[112] Limitations on how much of these materials is available could even mean that some technologies are not worth pursuing long term.... "Virgin stocks of several metals appear inadequate to sustain the modern 'developed world' quality of life for all of Earth's people under contemporary technology".[113]

On the other hand, some cornucopian researchers, such as Julian L. Simon and Bjørn Lomborg believe that resources exist for further population growth. In a 2010 study, they concluded that "there are not (and will never be) too many people for the planet to feed" according to The Independent.[114] Some critics warn, this will be at a high cost to the Earth: "the technological optimists are probably correct in claiming that overall world food production can be increased substantially over the next few decades...[however] the environmental cost of what Paul R. and Anne H. Ehrlich describe as 'turning the Earth into a giant human feedlot' could be severe. A large expansion of agriculture to provide growing populations with improved diets is likely to lead to further deforestation, loss of species, soil erosion, and pollution from pesticides and fertilizer runoff as farming intensifies and new land is brought into production."[115]

According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, a four-year research effort by 1,360 of the world's prominent scientists commissioned to measure the actual value of natural resources to humans and the world, "The structure of the world's ecosystems changed more rapidly in the second half of the twentieth century than at any time in recorded human history, and virtually all of Earth's ecosystems have now been significantly transformed through human actions."[116] "Ecosystem services, particularly food production, timber and fisheries, are important for employment and economic activity. Intensive use of ecosystems often produces the greatest short-term advantage, but excessive and unsustainable use can lead to losses in the long term. A country could cut its forests and deplete its fisheries, and this would show only as a positive gain to GDP, despite the loss of capital assets. If the full economic value of ecosystems were taken into account in decision-making, their degradation could be significantly slowed down or even reversed."[117][118]

Another study was done by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) called the Global Environment Outlook.[119]

Although all resources, whether mineral or other, are limited on the planet, there is a degree of self-correction whenever a scarcity or high-demand for a particular kind is experienced. For example, in 1990 known reserves of many natural resources were higher, and their prices lower, than in 1970, despite higher demand and higher consumption. Whenever a price spike would occur, the market tended to correct itself whether by substituting an equivalent resource or switching to a new technology.[119]

Fresh water

Overpopulation may lead to inadequate fresh water access[120] for drinking as well as sewage treatment and effluent discharge.[citation needed] Fresh water supplies, on which agriculture depends, are running low worldwide.[121][122] Overexploitation of water resources is expected to worsen as the population increases.[123] Most of the 3 billion people projected to be added worldwide by mid-century will be born in countries already experiencing water shortages.Some experts propose desalination a technological solution to the problem of water shortages.[124][125]

Land

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

This article possibly contains original research. (January 2021) |

The World Resources Institute states that "Agricultural conversion to croplands and managed pastures has affected some 3.3 billion [hectares]—roughly 26 percent of the land area. All totaled, agriculture has displaced one-third of temperate and tropical forests and one-quarter of natural grasslands."[126][127] Forty percent of the land area is under conversion and fragmented; less than one quarter, primarily in the Arctic and the deserts, remains intact.[128] Usable land may become less useful through salinization, deforestation, desertification, erosion, and urban sprawl. The development of energy sources may also require large areas, for example, the building of hydroelectric dams. Thus, available useful land may become a limiting factor. By most estimates, at least half of cultivable land is already being farmed, and there are concerns that the remaining reserves are greatly overestimated.[129]

Some countries, such as the United Arab Emirates and particularly the Emirate of Dubai have constructed large artificial islands, or have created large dam and dike systems, like the Netherlands, which reclaim land from the sea to increase their total land area.[130][131] Some scientists have said that in the future, densely populated cities will use vertical farming to grow food inside skyscrapers.[132] The notion that space is limited has been decried by skeptics, who point out that the Earth's population of roughly 6.8 billion people could comfortably be housed an area comparable in size to the state of Texas, in the United States (about 269,000 square miles or 696,706.80 square kilometres).[133]

Food

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

A 2001 United Nations report says population growth is "the main force driving increases in agricultural demand" but "most recent expert assessments are cautiously optimistic about the ability of global food production to keep up with demand for the foreseeable future (that is to say, until approximately 2030 or 2050)", assuming declining population growth rates.[134] However, the observed figures for 2016 show an actual increase in absolute numbers of undernourished people in the world, 815 million in 2016 versus 777 million in 2015.[135] The FAO estimates that these numbers are still far lower than the nearly 900 million registered in 2000.[135]

Although the proportion of "starving" people in sub-Saharan Africa has decreased, the absolute number of starving people has increased due to population growth. The percentage dropped from 38% in 1970 to 33% in 1996 and was expected to be 30% by 2010.[136] But the region's population roughly doubled between 1970 and 1996. To keep the numbers of starving constant, the percentage would have dropped by more than half.[117][137]

Current industrial food and agricultural practices are expected to not be sufficient for future food security.[138] Mismanagement of phosphorus, wild fish stocks, water and topsoil may lead to decline in food system productivity in the near future, especially when combined with changes caused by climate change.[139][140][138] At the same time, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), food supplies will need to be increased by 70% by 2050 to meet projected demands.[141]

Relation to non-human population growth

Human population, its prevailing growth of demands of livestock and other domestic animals, has added overshoot through domestic animal breeding, keeping and consumption, especially with the environmentally destructive industrial livestock production.[144]

Other

- Loss of arable land and increase in desertification.[145] Deforestation and desertification can be reversed by adopting less intensive agricultural practices, and this policy is successful even while the human population continues to grow.[146]

- Increased chance of the emergence of new epidemics and pandemics.[147] For many environmental and social reasons, including overcrowded living conditions, malnutrition and inadequate, inaccessible, or non-existent health care, the poor are more likely to be exposed to infectious diseases.[148]

- Starvation, malnutrition[149] or poor diet with ill health and diet-deficiency diseases (e.g. rickets). However, rich countries with high population densities do not have famine.[150]

- Low life expectancy in countries with fastest growing populations.[151] Overall life expectancy has increased globally despite of population growth, including countries with fast-growing populations.[82]

- Unhygienic living conditions for many based upon water resource depletion, discharge of raw sewage[152] and solid waste disposal. However, this problem can be reduced with the adoption of sewers. For example, after Karachi, Pakistan installed sewers, its infant mortality rate fell substantially.[153]

- Elevated crime rate due to drug cartels and increased theft by people stealing resources to survive.[154]

- Less personal freedom and more restrictive laws. Laws regulate and shape politics, economics, history and society and serve as a mediator of relations and interactions between people. The higher the population density, the more frequent such interactions become, and thus there develops a need for more laws and/or more restrictive laws to regulate these interactions and relations. It was speculated by Aldous Huxley in 1958 that democracy is threatened by overpopulation, and could give rise to totalitarian style governments.[155] Physics professor Albert Allen Bartlett at the University of Colorado Boulder warned in 2000 that overpopulation and the development of technology are the two major causes of the diminution of democracy.[156] However, over the last 200 years of population growth, the actual level of personal freedom has increased rather than declined.[82]

Future dynamics

Projections of population growth

| Continent | Projected 2050 population

by UN in 2017[157] |

|---|---|

| Africa | 2.5 billion |

| Asia | 5.5 billion |

| Europe | 716 million |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 780 million |

| North America | 435 million |

Population projections are attempts to show how the human population statistics might change in the future.[158] These projections are an important input to forecasts of the population's impact on this planet and humanity's future well-being.[159] Models of population growth take trends in human development and apply projections into the future.[160] These models use trend-based-assumptions about how populations will respond to economic, social and technological forces to understand how they will affect fertility and mortality, and thus population growth.[160]

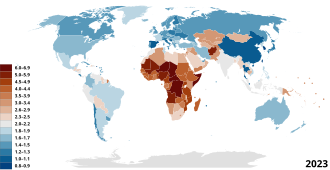

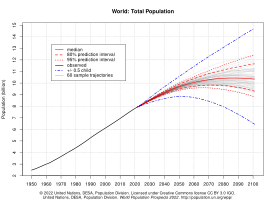

The 2022 projections from the United Nations Population Division (chart #1) show that annual world population growth peaked at 2.3% per year in 1963, has since dropped to 0.9% in 2023, equivalent to about 74 million people each year, and could drop even further to minus 0.1% or rise to between 1 to 2.5% or higher by 2100.[161] Based on this, the UN projected that the world population, 8 billion as of 2023[update], would peak around the year 2086 at about 10.4 billion, and then start a slow decline, assuming a continuing decrease in the global average fertility rate from 2.5 births per woman during the 2015–2020 period to 1.8 by the year 2100 (the medium-variant projection).[162][163]

However, estimates outside of the United Nations have put forward alternative models based on additional downward pressure on fertility (such as successful implementation of education and family planning goals in the UN's Sustainable Development Goals) which could result in peak population during the 2060–2070 period rather than later.[160][164]

According to the UN, all of the predicted growth in world population between 2020 and 2050 will come from less developed countries and more than half will come from sub-Saharan Africa.[165] Half of the growth will come from just eight countries, five of which are in Africa.[162][163] The UN predicts that the population of sub-Saharan Africa will double by 2050.[165] The Pew Research Center observes that 50% of births in the year 2100 will be in Africa.[166] Other organizations project lower levels of population growth in Africa, based particularly on improvement in women's education and successful implementation of family planning.[167]

Even though the global fertility rate continues to fall, chart #2 shows that because of population momentum the global population will continue to grow, although at a steadily slower rate, until the mid 2080s (the median line).

The main driver of long-term future population growth on this planet is projected to be the continuing evolution of fertility and mortality.[160]Overconsumption

Some groups (for example, the World Wide Fund for Nature[169][170] and Global Footprint Network) have stated that the yearly biocapacity of Earth is being exceeded as measured using the ecological footprint. In 2006, WWF's "Living Planet Report" stated that in order for all humans to live with the current consumption patterns of Europeans, we would be spending three times more than what the planet can renew.[171] Humanity as a whole was using, by 2006, 40 percent more than what Earth can regenerate.[172] However, Roger Martin of Population Matters states the view: "the poor want to get rich, and I want them to get rich," with a later addition, "of course we have to change consumption habits,... but we've also got to stabilise our numbers".[173] Another study by the World Wildlife Fund in 2014 found that it would take the equivalent of 1.5 Earths of biocapacity to meet humanity's current levels of consumption.[174]

But critics question the simplifications and statistical methods used in calculating ecological footprints. Therefore, Global Footprint Network and its partner organizations have engaged with national governments and international agencies to test the results—reviews have been produced by France, Germany, the European Commission, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Japan and the United Arab Emirates.[175] Some point out that a more refined method of assessing Ecological Footprint is to designate sustainable versus non-sustainable categories of consumption.[176][177]

Carrying capacity

Many studies have tried to estimate the world's carrying capacity for humans, that is, the maximum population the world can host.[178] A meta-analysis of 69 such studies from 1694 until 2001 found the average predicted maximum number of people the Earth would ever have was 7.7 billion people, with lower and upper meta-bounds at 0.65 and 98 billion people, respectively. They conclude: "recent predictions of stabilized world population levels for 2050 exceed several of our meta-estimates of a world population limit".[179]

Advocates of reduced population, often put forward much lower numbers. For example, Paul R. Ehrlich stated in 2018 that the optimum size of the global human population is between 1.5 and 2 billion.[180] Geographer Chris Tucker estimates that 3 billion is a sustainable number.[181]

Critics of overpopulation criticize the basic assumptions associated with these estimates. For example, Jade Sasser believes that calculating a maximum of number of humanity which may be allowed to live while only some, mostly privileged European former colonial powers, are mostly responsible for unsustainably using up the Earth is wrong.[182]

Proposed solutions and mitigation measures

Several solutions and mitigation measures have the potential to reduce overpopulation. Some solutions are to be applied on a global planetary level (e.g., via UN resolutions), while some on a country or state government organization level, and some on a family or an individual level. Some of the proposed mitigations aim to help implement new social, cultural, behavioral and political norms to replace or significantly modify current norms. For example, in countries like China, the government has put policies in place that regulate the number of children allowed to a couple. Other countries have implemented social marketing strategies in order to educate the public on overpopulation effects. Such prompts work to introduce the problem so that new or modified social norms are easier to implement. Education and empowerment of women and giving access to family planning and contraception have demonstrated positive impacts on reducing birthrates.

Scientists and technologists including e.g. Huesemann and Ehrlich caution that science and technology, as currently practiced, cannot solve the serious problems global human society faces, and that a cultural-social-political shift is needed to reorient science and technology in a more socially responsible and environmentally sustainable direction.[183][184]

Population planning

Education and empowerment

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

One option according to some activists is to focus on education about overpopulation, family planning, and birth control methods, and to make birth-control devices like male and female condoms, contraceptive pills and intrauterine devices easily available. Worldwide, nearly 40% of pregnancies are unintended (some 80 million unintended pregnancies each year).[185] An estimated 350 million women in the poorest countries of the world either did not want their last child, do not want another child or want to space their pregnancies, but they lack access to information, affordable means and services to determine the size and spacing of their families. In the United States, in 2001, almost half of pregnancies were unintended.[186] In the developing world, some 514,000 women die annually of complications from pregnancy and abortion,[187] with 86% of these deaths occurring in the sub-Saharan Africa region and South Asia.[188] Additionally, 8 million infants die, many because of malnutrition or preventable diseases, especially from lack of access to clean drinking water.[189]

Women's rights and their reproductive rights in particular are issues regarded to have vital importance in the debate.[190] This incentive, however, has been questioned by Rosalind Pollack Petchesky. Citing his attendance of the 1994 Cairo conference, he reported that overpopulation and birth control were being diverted by feminists into women's rights issues, mostly downplaying the overpopulation issue as only one minor matter of many others; most of these focusing on women's rights. Upon his observation, he argued this was forging many faults and distractions on the main problem of human overpopulation and how to solve it.[191]

Several scientists (including e.g. Paul and Anne Ehrlich and Gretchen Daily) proposed that humanity should work at stabilizing its absolute numbers, as a starting point towards beginning the process of reducing the total numbers. They suggested the following solutions and policies: following a small-family-size socio-cultural-behavioral norm worldwide (especially one-child-per-family ethos), and providing contraception to all along with proper education on its use and benefits (while providing access to safe, legal abortion as a backup to contraception), combined with a significantly more equitable distribution of resources globally.[192][193] In the book "Evolution Science and Ethics in the Third Millennium", Robert Cliquet and Dragana Avramov also point out that the one (and a half)-child-per-family ethos is certainly a good one and that we should reduce the world population so that it is no larger than 1 to 3 billion.[194]

Population planning that is intended to reduce population size or growth rate may promote or enforce one or more of the following practices, although there are other methods as well:

- Greater and better access to contraception

- Reducing infant mortality so that parents do not need to have many children to ensure at least some survive to adulthood.[195]

- Improving the status of women in order to facilitate a departure from traditional sexual division of labour.

- One-Child and Two-Child policies, and other policies restricting or discouraging births directly.

- Family planning[196]

- Creating small family "role models"[196]

- Tighter immigration restrictions

Birth regulations

Overpopulation can be mitigated by birth control; some nations, like the People's Republic of China, use strict measures to reduce birth rates. Religious and ideological opposition to birth control has been cited as a factor contributing to overpopulation and poverty.[197]

Sanjay Gandhi, son of late Prime Minister of India Indira Gandhi, implemented a forced sterilization programme between 1975 and 1977. Officially, men with two children or more had to submit to sterilization, but there was a greater focus on sterilizing women than sterilizing men. Some unmarried young men and political opponents may also have been sterilized.[citation needed] This program is still remembered and criticized in India, and is blamed for creating a public aversion to family planning, which hampered government programs for decades.[198]

Another choice-based approach is financial compensation or other benefits (free goods and/or services) by the state (or state-owned companies) offered to people who voluntarily undergo sterilization. Such compensation has been offered in the past by the government of India.[199]

In 2014 the United Nations estimated there is an 80% likelihood that the world's population will be between 9.6 billion and 12.3 billion by 2100. Most of the world's expected population increase will be in Africa and southern Asia. Africa's population is expected to rise from the current one billion to four billion by 2100, and Asia could add another billion in the same period.[200]

Extraterrestrial settlement

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

Various scientists and science fiction authors have contemplated that overpopulation on Earth may be remedied in the future by the use of extraterrestrial settlements. In the 1970s, Gerard K. O'Neill suggested building space habitats that could support 30,000 times the carrying capacity of Earth using just the asteroid belt, and that the Solar System as a whole could sustain current population growth rates for a thousand years.[201] Marshall Savage (1992, 1994) has projected a human population of five quintillion (5 × 1018) throughout the Solar System by 3000, with the majority in the asteroid belt.[202] In Mining the Sky, John S. Lewis suggests that the resources of the solar system could support 10 quadrillion (1016) people. In an interview, Stephen Hawking claimed that overpopulation is a threat to human existence and "our only chance of long-term survival is not to remain inward looking on planet Earth but to spread out into space."[203] K. Eric Drexler has suggested in Engines of Creation that settling space will mean breaking the Malthusian limits to growth for the human species.[citation needed]

Many science fiction authors, including Carl Sagan, Arthur C. Clarke,[204] and Isaac Asimov,[205] have argued that shipping any excess population into space is not a viable solution to human overpopulation. According to Clarke, "the population battle must be fought or won here on Earth".[204] The problem for these authors is not the lack of resources in space (as shown in books such as Mining the Sky[206]), but the physical impracticality of shipping vast numbers of people into space to "solve" overpopulation on Earth. However according to calculations by Gerard K. O'Neill all new population growth could be facilitated with a launch services industry about the same size as the current airline industry.[207]

Urbanization

Despite the increase in population density within cities (and the emergence of megacities), UN Habitat states in its reports that urbanization may be the best compromise in the face of global population growth.[208] Cities concentrate human activity within limited areas, limiting the breadth of environmental damage.[209] UN Habitat says this is only possible if urban planning is significantly improved.[210]

Paul Ehrlich pointed out in his book The Population Bomb (1968) argues that rhetoric supporting the increase of city density as a means of avoiding dealing with the actual problem of overpopulation to begin with and rather than treating the increase of city density as a symptom of the root problem, it has been promoted by the same interests that have profited from population increase e.g. property developers, the banking system, which invests in property development, industry, municipal councils etc.[211] Subsequent authors point to growth economics as driving governments seek city growth and expansion at any cost disregarding the impact it might have on the environment.[212]

Criticism

According to libertarian think tank the Fraser Institute, both the idea of overpopulation and the alleged depletion of resources are myths; most resources are now more abundant than a few decades ago, thanks to technological progress.[214] The Institute is also questioning the sincerity of advocates of population control in poor countries who tend to have meetings at expensive high-class hotels in exotic spots.[214]

The "myth of overpopulation" is a popular term used to describe a simple yet often misinformed equation about overpopulation. This equation encompasses the idea that more people equals fewer resources available and leads to a rise in poverty and environmental concerns.[215]

Women's rights

Influential advocates such as Betsy Hartmann consider the "myth of overpopulation" to be destructive as it “prevents constructive thinking and action on reproductive rights”, which acutely effects women and communities of women in poverty.[215] The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) define reproductive rights as “the basic right of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing, and timing of their children and to have the information to do so."[216] This oversimplification of human overpopulation leads individuals to believe there are simple solutions and the creation of population policies that limit reproductive rights.

Scholar Heather Alberro argues to reject the overpopulation argument, stating that the human population growth is rapidly slowing down, the underlying problem is not the number of people, but how resources are distributed and that the idea of overpopulation could fuel a racist backlash against the population of poor countries.[217]

Racism

The argument of overpopulation has been criticized as racist since control and reduction of human population is often focused on the global south, instead of on overconsumption and the global north.[218][219]

By public figures

Elon Musk is a vocal critic of the idea of overpopulation. According to Musk, proponents of the idea are misled by their immediate impressions from living in dense cities.[220] Because of the negative replacement rates in many countries, he expects that by 2039 the biggest issue will be population collapse, not explosion.[221] Jack Ma expressed a similar opinion.[221]

See also

- Demographic trap

- The Limits to Growth

- Global issue

- Human population planning

- Malthusian catastrophe

- Overexploitation

- Overshoot (population)

- Planetary boundaries

- Voluntary Human Extinction Movement

- Antinatalism

- Overpopulation in domestic pets

Lists

- List of organisations campaigning for population stabilisation

- List of population concern organizations

Documentary and art

References

- ^ Paul Ehrlich; Anne H. Ehrlich (4 August 2008). "Too Many People, Too Much Consumption". Yale Environment 360. Yale School of the Environment. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R. Ehrlich & Anne H. (1990). The population explosion. London: Hutchinson. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0091745516. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

When is an area overpopulated? When its population cannot be maintained without rapidly depleting nonrenewable resources [39] (or converting renewable resources into nonrenewable ones) and without decreasing the capacity of the environment to support the population. In short, if the long-term carrying capacity of an area is clearly being degraded by its current human occupants, that area is overpopulated.

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R; Ehrlich, Anne H (2004), One with Nineveh: Politics, Consumption, and the Human Future, Island Press/Shearwater Books, pp. 76–180, 256

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R; Ehrlich, Anne H (1991), Healing the Planet: Strategies for Resolving the Environmental Crisis, Addison-Wesley Books, pp. 6–8, 12, 75, 96, 241

- ^ "Human Overpopulation: Still an Issue of Concern?". Scientific American. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ a b Fletcher, Robert; Breitling, Jan; Puleo, Valerie (9 August 2014). "Barbarian hordes: the overpopulation scapegoat in international development discourse". Third World Quarterly. 35 (7): 1195–1215. doi:10.1080/01436597.2014.926110. ISSN 0143-6597.

- ^ "The spectre of "overpopulation"". Transnational Institute. 7 December 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Dyett, Jordan; Thomas, Cassidy (18 January 2019). "Overpopulation Discourse: Patriarchy, Racism, and the Specter of Ecofascism". Perspectives on Global Development and Technology. 18 (1–2): 205–224. doi:10.1163/15691497-12341514. ISSN 1569-1500.

- ^ Thomas, Cassidy; Gosink, Elhom (25 March 2021). "At the Intersection of Eco-Crises, Eco-Anxiety, and Political Turbulence: A Primer on Twenty-First Century Ecofascism". Perspectives on Global Development and Technology. 20 (1–2): 30–54. doi:10.1163/15691497-12341581. ISSN 1569-1500.

- ^ Roberts, R.E. (1924). The Theology of Tertullian, Chapter 5 (pp. 79–119) Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Tertullian.org (14 July 2001). Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ Joseph A. Tainter (2006). "Archaeology of Overshoot and Collapse". Annual Review of Anthropology. 35: 59–74. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123136.

- ^ "VII, paragraph 10, lines 8–10". An Essay on the Principle of Population. London: J. Johnson. 1798.

The power of population is so superior to the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race

- ^ a b Gregory Claeys: The "Survival of the Fittest" and the Origins of Social Darwinism, in Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 61, No. 2, 2002, p. 223–240

- ^ Cormac Ó Gráda: Famine. A Short History, Princeton University Press 2009, ISBN 978-0-691-12237-3 (pp. 20, 203–206)

- ^ World population to keep growing this century, hit 11 billion by 2100 Archived 4 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. UWToday. 18 September 2014

- ^ Moody, Oliver (31 August 2017). "Overpopulation is the biggest threat to mankind, Nobel laureates say". The Times. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Galetti M, Alamgir M, Crist E, Mahmoud MI, Laurance WF (13 November 2017). "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice" (PDF). BioScience. 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125.

- ^ Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M; Barnard, Phoebe; Moomaw, William R (5 November 2019). "World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency". BioScience. doi:10.1093/biosci/biz088. hdl:1808/30278. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (5 November 2019). "Climate crisis: 11,000 scientists warn of 'untold suffering'". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ "Black death 'discriminated' between victims". 29 January 2008. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ Roser, Max; Ritchie, Hannah; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban (9 May 2013). "World Population Growth". Our World in Data.

- ^ Pimentel, David. "Overpopulation and sustainability." Petroleum Review 59 (2006): 34-36.

- ^ Hayami, Yujiro, and Vernon W. Ruttan. "Population growth and agricultural productivity." Technological Prospects and Population Trends. Routledge, 2020. 11-69.

- ^ Smil, Vaclav (1999). "Detonator of the population explosion" (PDF). Nature. 400 (6743): 415. Bibcode:1999Natur.400..415S. doi:10.1038/22672. S2CID 4301828.

- ^ a b "Population seven billion: UN sets out challenges". BBC. 22 May 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ Cassils, J. Anthony. "Overpopulation, sustainable development, and security: Developing an integrated strategy." Population and Environment 25.3 (2004): 171-194.

- ^ Moseley, William G. "Reflecting on National Geographic Magazine and academic geography: The September 2005 special issue on Africa." African Geographical Review 24.1 (2005): 93-100.

- ^ Asongu, Simplice, and Brian Jingwa. "Population growth and forest sustainability in Africa." International Journal of Green Economics 6.2 (2012): 145-166.

- ^ "Current World Population". Worldometers. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ "A Brief Introduction to the History of Climate". Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ "The Neolithic Agricultural Revolution" (PDF). Council For Economic Education. p. 46. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ "Plague, Plague Information, Black Death Facts, News, Photos". National Geographic. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ "Epidemics and pandemics: their impacts on human history". J. N. Hays (2005). p.46. ISBN 1-85109-658-2

- ^ "Historical Estimates of World Population". Census.gov. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ "History of Europe – Demographic and agricultural growth". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Europe's Black Death is a history lesson in human tragedy – and economic renewal". TIME Europe. 17 July 2000, VOL. 156 NO. 3

- ^ "Ming Dynasty: Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2009". Archived from the original on 26 January 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Qing China's Internal Crisis: Land Shortage, Famine, Rural Poverty". Asia for Educators, Columbia University.

- ^ J. N. Hays (1998). "The burdens of disease: epidemics and human response in western history.". p 72. ISBN 0-8135-2528-4

- ^ "The Story Of... Smallpox – and other Deadly Eurasian Germs". Public Broadcasting Service (PBS).

- ^ Nunn, Nathan (27 February 2017). "Understanding the long-run effects of Africa's slave trades". VoxEU.org. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ a b "International Programs". census.gov. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013.

- ^ "The limits of a Green Revolution?". BBC News. 29 March 2007.

- ^ "United Nations, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2011): World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision". Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "modelling exponential growth" (PDF). esrl.noaa.gov.

- ^ Benatar, David (2008). Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence. Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0199549269.

- ^ Penfound, William T. "The Problems of Overpopulation". Bios, vol. 39, no. 2, 1968, pp. 56–62. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4606831. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Feeney J. Hunter-gatherer land management in the human break from ecological sustainability. The Anthropocene Review. 2019;6(3):223-242. doi:10.1177/2053019619864382

- ^ Huesemann, M.H., and J.A. Huesemann (2011). Technofix: Why Technology Won't Save Us or the Environment, "Unintended Consequences of Industrial Agriculture", New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, Canada, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Techno-Fix: Why Technology Won't Save Us Or the Environment By Michael Huesemann, Joyce Huesemann. New Society Publishers. p. 73.

despite the fact that hunger and starvation may not be due to food shortages but rather the result of various economic and political factors

- ^ McKeown, T. (1988). The Origins of Human Disease, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, UK, pp.60.

- ^ Correction for Zahid et al., Agriculture, population growth, and statistical analysis of the radiocarbon record. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(18):E2546. doi:10.1073/pnas.1605181113

- ^ Cite Warren, Stephen G. "Did agriculture cause the population explosion?." Nature 397.6715 (1999): 101.

- ^ Armelagos, George J.; Goodman, Alan H.; Jacobs, Kenneth H. (1 September 1991). "The origins of agriculture: Population growth during a period of declining health". Population and Environment. 13 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1007/BF01256568. ISSN 1573-7810. S2CID 153470610.

- ^ Taiz, Lincoln. "Agriculture, plant physiology, and human population growth: past, present, and future." Theoretical and Experimental Plant Physiology 25.3 (2013): 167-181.

- ^ Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, A. H.; Ehrlich, P. R. (2015). The Annihilation of Nature: Human Extinction of Birds and Mammals. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 146 ISBN 1421417189

- ^ Kelly, Karina (13 September 1995). "A Chat with Tim Flannery on Population Control". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010. "Well, Australia has by far the world's least fertile soils".

- ^ Grant, Cameron (August 2007). "Damaged Dirt" (PDF). The Advertiser. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

Australia has the oldest, most highly weathered soils on the planet.

- ^ a b c Hopfenberg, Russell and Pimentel, David, "Human Population Numbers as a Function of Food Supply", Environment, Development and Sustainability, vol. 3, no. 1, March 2001, pp. 1–15

- ^ "Human Carrying Capacity is Determined by Food Availability" (PDF). Russel Hopfenberg, Duke University.

- ^ Abernathy, Virginia, Population Politics ISBN 0-7658-0603-7

- ^ GJ Armelagos, AH Goodman, KH Jacobs Population and environment - 1991 link.springer.com

- ^ Rosa, Daniele (2019). "Nel 2050 gli italiani saranno 20 milioni meno secondo l'Onu [Translation: In 2050 the Italians will be 20 million less, according to the UN]". Affaritaliani. Uomini & Affari Srl.

- ^ Daniel Quinn (1996). The Story of B, pp. 304–305, Random House Publishing Group, ISBN 0553379011.

- ^ Quinn, Daniel: "The Question (ID Number 122)". Retrieved October 2014 from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). - ^ "U.S. and World Population Clock". Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ "Population seven billion: UN sets out challenges". BBC. 26 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ Coleman, Jasmine (31 October 2011). "World's 'seven billionth baby' is born". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ "7 billion people is a 'serious challenge'". United Press International.

- ^ United Nations. "Definition of projection variants". United Nation Population Division. United Nations. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ "World population projected to reach 9.8 billion in 2050, and 11.2 billion in 2100". Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. June 2017.

- ^ "The end of high fertility is near" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "World Population Prospects" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "joint statement by fifty-eight of the world's scientific academies". Archived from the original on 10 February 2010.

- ^ Wilson, E.O. (2002). The Future of Life, Vintage ISBN 0-679-76811-4

- ^ a b c Ron Nielsen, The Little Green Handbook: Seven Trends Shaping the Future of Our Planet, Picador, New York (2006) ISBN 978-0-312-42581-4

- ^ Pentti Linkola, "Can Life Prevail?", Arktos Media, 2nd Revised ed. 2011. pp. 120–121. ISBN 1907166637

- ^ McKie, Robin (25 January 2017). "Biologists think 50% of species will be facing extinction by the end of the century". The Observer.

- ^ Leaders from the 1960s: A Biographical Sourcebook of American Activism. Greenwood Press, 1994. 1994. p. 318. ISBN 9780313274145.

- ^ U.S. National Research Council, Commission on the Science of Climate Change, Washington, D.C. (2001)

- ^ Image:Infant mortality vs.jpg

- ^ a b c "The short history of global living conditions and why it matters that we know it". Our World in Data. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ "Does population growth lead to hunger and famine?". Our World in Data. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ Human overpopulation. Animal Welfare Institute. Retrieved 2014/10/25 from "Human Overpopulation". Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Daily, Gretchen C. and Ellison, Katherine (2003) The New Economy of Nature: The Quest to Make Conservation Profitable, Island Press ISBN 1559631546

- ^ Subramanian, Meera (2019). "Anthropocene now: influential panel votes to recognize Earth's new epoch". Nature News. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

Twenty-nine members of the AWG supported the Anthropocene designation and voted in favour of starting the new epoch in the mid-twentieth century, when a rapidly rising human population accelerated the pace of industrial production, the use of agricultural chemicals and other human activities.

- ^ Syvitski, Jaia; Waters, Colin N.; Day, John; et al. (2020). "Extraordinary human energy consumption and resultant geological impacts beginning around 1950 CE initiated the proposed Anthropocene Epoch". Communications Earth & Environment. 1 (32). doi:10.1038/s43247-020-00029-y. S2CID 222415797.

Human population has exceeded historical natural limits, with 1) the development of new energy sources, 2) technological developments in aid of productivity, education and health, and 3) an unchallenged position on top of food webs. Humans remain Earth's only species to employ technology so as to change the sources, uses, and distribution of energy forms, including the release of geologically trapped energy (i.e. coal, petroleum, uranium). In total, humans have altered nature at the planetary scale, given modern levels of human-contributed aerosols and gases, the global distribution of radionuclides, organic pollutants and mercury, and ecosystem disturbances of terrestrial and marine environments. Approximately 17,000 monitored populations of 4005 vertebrate species have suffered a 60% decline between 1970 and 2014, and ~1 million species face extinction, many within decades. Humans' extensive 'technosphere', now reaches ~30 Tt, including waste products from non-renewable resources.

- ^ "UN World Population Report 2001" (PDF). p. 31. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ^ John T. Houghton (2004)."Global warming: the complete briefing Archived 3 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine". Cambridge University Press. p.326. ISBN 0-521-52874-7

- ^ "Once taboo, population enters climate debate". The Independent. London. 5 December 2009. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ Best, Steven (2014). The Politics of Total Liberation: Revolution for the 21st Century. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 160. ISBN 978-1137471116.

By 2050 the human population will top 9 billion, and world meat consumption will likely double.

- ^ Devlin, Hannah (19 July 2018). "Rising global meat consumption 'will devastate environment'". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ We Are Breeding Ourselves to Extinction. Chris Hedges for Truthdig. 8 March 2009

- ^ Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Barnosky, Anthony D.; García, Andrés; Pringle, Robert M.; Palmer, Todd M. (2015). "Accelerated modern human–induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction". Science Advances. 1 (5): e1400253. Bibcode:2015SciA....1E0253C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1400253. PMC 4640606. PMID 26601195.

- ^ Pimm, S. L.; Jenkins, C. N.; Abell, R.; Brooks, T. M.; Gittleman, J. L.; Joppa, L. N.; Raven, P. H.; Roberts, C. M.; Sexton, J. O. (30 May 2014). "The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection" (PDF). Science. 344 (6187): 1246752. doi:10.1126/science.1246752. PMID 24876501. S2CID 206552746. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

The overarching driver of species extinction is human population growth and increasing per capita consumption.

- ^ Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R; Dirzo, Rodolfo (23 May 2017). "Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines". PNAS. 114 (30): E6089–E6096. doi:10.1073/pnas.1704949114. PMC 5544311. PMID 28696295.

Much less frequently mentioned are, however, the ultimate drivers of those immediate causes of biotic destruction, namely, human overpopulation and continued population growth, and overconsumption, especially by the rich. These drivers, all of which trace to the fiction that perpetual growth can occur on a finite planet, are themselves increasing rapidly.

- ^ Andermann, Tobias; Faurby, Søren; Turvey, Samuel T.; Antonelli, Alexandre; Silvestro, Daniele (1 September 2020). "The past and future human impact on mammalian diversity". Science Advances. 6 (36): eabb2313. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb2313. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7473673. PMID 32917612.

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text and images are available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Weston, Phoebe (13 January 2021). "Top scientists warn of 'ghastly future of mass extinction' and climate disruption". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

Large populations and their continued growth drive soil degradation and biodiversity loss, the new paper warns. "More people means that more synthetic compounds and dangerous throwaway plastics are manufactured, many of which add to the growing toxification of the Earth. It also increases the chances of pandemics that fuel ever-more desperate hunts for scarce resources."

- ^ Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Beattie, Andrew; Ceballos, Gerardo; Crist, Eileen; Diamond, Joan; Dirzo, Rodolfo; Ehrlich, Anne H.; Harte, John; Harte, Mary Ellen; Pyke, Graham; Raven, Peter H.; Ripple, William J.; Saltré, Frédérik; Turnbull, Christine; Wackernagel, Mathis; Blumstein, Daniel T. (2021). "Underestimating the Challenges of Avoiding a Ghastly Future". Frontiers in Conservation Science. 1. doi:10.3389/fcosc.2020.615419. S2CID 231589034.

- ^ Pimm, Stuart L.; Russell, Gareth J.; Gittleman, John L.; Brooks, Thomas M. (1995). "The Future of Biodiversity". Science. 269 (5222): 347–350. Bibcode:1995Sci...269..347P. doi:10.1126/science.269.5222.347. PMID 17841251. S2CID 35154695.

- ^ Stokstad, Erik (5 May 2019). "Landmark analysis documents the alarming global decline of nature". Science. AAAS. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

Driving these threats are the growing human population, which has doubled since 1970 to 7.6 billion, and consumption. (Per capita of use of materials is up 15% over the past 5 decades.)

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (6 May 2019). "Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ Greenfield, Patrick (9 September 2020). "Humans exploiting and destroying nature on unprecedented scale – report". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ Lewis, Sophie (9 September 2020). "Animal populations worldwide have declined by almost 70% in just 50 years, new report says". CBS News. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ Crist, Eileen; Cafaro, Philip, eds. (2012). Life on the Brink: Environmentalists Confront Overpopulation. University of Georgia Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0820343853.

- ^ Sato, Chloe F.; Lindenmayer, David B. (2018). "Meeting the Global Ecosystem Collapse Challenge". Conservation Letters. 11 (1): e12348. doi:10.1111/conl.12348.

- ^ Bland, L.; Rowland, J.; Regan, T.; Keith, D.; Murray, N.; Lester, R.; Linn, M.; Rodríguez, J.P.; Nicholson, E. (2018). "Developing a standardized definition of ecosystem collapse for risk assessment". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 16 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1002/fee.1747.

- ^ Pinsky, Malin L.; Byler, David (22 August 2015). "Fishing, fast growth and climate variability increase the risk of collapse". Proc. R. Soc. B. 282 (1813): 20151053. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.1053. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 4632620. PMID 26246548.

- ^ "Another Inconvenient Truth: The World's Growing Population Poses a Malthusian Dilemma Archived 25 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine". Scientific American (2 October 2009).

- ^ David Pimentel, et al. "Will Limits of the Earth's Resources Control Human Numbers?" Archived 10 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Dieoff.org

- ^ Lester R. Brown, Gary Gardner, Brian Halweil (September 1998). Worldwatch Paper #143: Beyond Malthus: Sixteen Dimensions of the Population Problem Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Worldwatch Institute, ISBN 1-878071-45-9

- ^ a b "News". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ "Earth's natural wealth: an audit". New Scientist. 23 May 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Dominic Lawson: The population timebomb is a myth The doom-sayers are becoming more fashionable just as experts are coming to the view it has all been one giant false alarm". The Independent. UK. 18 January 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Misleading Math about the Earth: Scientific American". Sciam.com. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "1. How have ecosystems changed?". Greenfacts.org. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Ecosystem Change: Scientific Facts on Ecosystem Change". Greenfacts.org. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "3. How have ecosystem changes affected human well-being and poverty alleviation?". Greenfacts.org. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ a b "UN World Population Report 2001" (PDF). p. 34. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ^ Shiklomanov, I. A. (2000). "Appraisal and Assessment of World Water Resources". Water International. 25: 11–32. doi:10.1080/02508060008686794. S2CID 4936257.

- ^ Brown, Lester R. and Halweil, Brian (23 September 1999). Population Outrunning Water Supply as World Hits 6 Billion. Worldwatch Institute.

- ^ Fred Pearce (2007). When the Rivers Run Dry: Water—The Defining Crisis of the Twenty-first Century. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-8573-8.

- ^ Worldwatch, The (27 April 2012). Outgrowing the Earth: The Food Security Challenge in an Age of Falling Water Tables and Rising Temperatures: Books: Lester R. Brown. ISBN 978-0393060706.

- ^ "French-run water plant launched in Israel". Ejpress.org. 28 December 2005. Archived from the original on 13 December 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Black & Veatch-Designed Desalination Plant Wins Global Water Distinction". Edie.net. 4 May 2006. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Domesticating the World: Conversion of Natural Ecosystems". World Resources Institute. September 2000. Archived from the original on 19 February 2007.

- ^ "Grasslands in Pieces: Modification and Conversion Take a Toll". World Resources Institute. December 2000. Archived from the original on 19 February 2007.

- ^ "GLOBIO, an initiative of the United Nations Environment Programme (Archive)". 30 June 2007. Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ Young, A. (1999). "Is there Really Spare Land? A Critique of Estimates of Available Cultivable Land in Developing Countries". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 1: 3–18. doi:10.1023/A:1010055012699. S2CID 153970029.

- ^ Tagliabue, John (7 November 2008). "The Dutch seek to claim more land from the sea". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Shepard, Wade (25 August 2015). ""The gift from the sea": through land reclamation, China keeps growing and growing". CityMetric. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Cooke, Jeremy (19 June 2007). "Vertical farming in the big Apple". BBC News. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Overpopulation: The Making of a Myth". Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ "UN World Population Report 2001" (PDF). p. 38. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ^ a b Food and Agriculture Organization Economic and Social Development Department. "The State of Food Insecurity in the World, 2018 : Building resilence for peace and food security. " . Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2018, p. 1.

- ^ Pimm, Stuart; Harvey, Jeff (2001). "No need to worry about the future" (PDF). Nature. 414 (6860): 149. Bibcode:2001Natur.414..149P. doi:10.1038/35102629. S2CID 205022759. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2007.

- ^ "3. How have ecosystem changes affected human well-being and poverty alleviation?". Greenfacts.org. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ a b Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C.; Barioni, L. G.; Benton, T.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Food Security" (PDF). IPCC SRCCL 2019. pp. 437–550.

- ^ "Global threat to food supply as water wells dry up, warns top environment expert Archived 8 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine". The Guardian. 6 July 2013.

- ^ "Do we only have 60 harvests left?". Our World in Data. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ "Global food production will have to increase 70% for additional 2.3 billion people by 2050 Archived 10 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine". Finfacts.com. 24 September 2009.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (21 May 2018). "Humans just 0.01% of all life but have destroyed 83% of wild mammals – study". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Baillie, Jonathan; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2018). "Space for nature". Science. 361 (6407): 1051. Bibcode:2018Sci...361.1051B. doi:10.1126/science.aau1397. PMID 30213888.

- ^ George Monbiot (19 November 2015). "There's a population crisis all right. But probably not the one you think". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ UNEP, Global Environmental Outlook 2000, Earthscan Publications, London, UK (1999)

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (11 February 2007). "Trees and crops reclaim desert in Niger". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ ""Emerging Infectious Diseases" by Mark E.J. Woolhouse and Sonya Gowtage-Sequeria". Cdc.gov. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "WHO Infectious Diseases Report". Who.int. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2001). Food Insecurity: When People Live With Hunger and Fear Starvation. The State of Food insecurity in the World 2001 Archived 1 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. FAO, ISBN 92-5-104628-X

- ^ Williams, Walter (24 February 1999). Population control nonsense Archived 15 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. jewishworldreview.com