John F. Kennedy International Airport

John F. Kennedy International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

John F. Kennedy International Airport in 2018 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner/Operator | Port Authority of New York and New Jersey[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | New York metropolitan area | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Jamaica, Queens, New York City, New York, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | July 1, 1948 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Focus city for | Polar Air Cargo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating base for | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | EST (UTC−05:00) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC−04:00) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 13 ft / 4 m | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 40°38′23″N 73°46′44″W / 40.63972°N 73.77889°W | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | jfkairport.com | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maps | |||||||||||||||||||||||

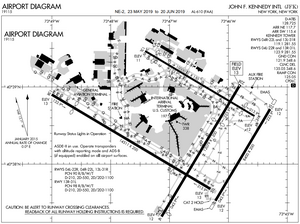

FAA airport diagram as of 2019 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Helipads | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2023) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

John F. Kennedy International Airport[a] (IATA: JFK, ICAO: KJFK, FAA LID: JFK) is a major international airport serving New York City, New York. The airport is the busiest of the seven airports in the New York airport system, the 6th-busiest airport in the United States, and the busiest international air passenger gateway into North America.[5] The facility covers 5,200 acres (2,104 ha) and is the largest and busiest airport in the New York City area.[6]

Over 90 airlines operate from the airport, with nonstop or direct flights to destinations on all six inhabited continents.[7][8]

JFK is located in the Jamaica neighborhood of Queens,[9] 16 miles (26 km) southeast of Midtown Manhattan. The airport features five passenger terminals and four runways. It is primarily accessible via car, bus, shuttle, or other vehicle transit via the JFK Expressway or Interstate 678 (Van Wyck Expressway), or via train. JFK is a hub for American Airlines and Delta Air Lines as well as the primary operating base for JetBlue.[10]

JFK is also a former hub for Braniff, Eastern, Flying Tigers, National, Northeast, Northwest, Pan Am, Seaboard World, Tower Air and TWA.

The facility opened in 1948 as New York International Airport[11][12][13] and was commonly known as Idlewild Airport.[14]

Following the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, the airport was renamed John F. Kennedy International Airport as a tribute to the 35th President of the United States.[15][16][17]

History[edit]

JFK (1),

LaGuardia (2),

Newark (3)

airports

Construction[edit]

John F. Kennedy International Airport was originally called Idlewild Airport (IATA: IDL, ICAO: KIDL, FAA LID: IDL) after the Idlewild Beach Golf Course that it displaced. It was built to relieve LaGuardia Field, which had become overcrowded after its 1939 opening.[18]: 2 In late 1941, mayor Fiorello La Guardia announced that the city had tentatively chosen a large area of marshland on Jamaica Bay, which included the Idlewild Golf Course as well as a summer hotel and a landing strip called the Jamaica Sea-Airport, for a new airfield.[18]: 2 [19] Title to the land was conveyed to the city at the end of December 1941.[20] Construction began in 1943,[21] though the airport's final layout was not yet decided upon.[18]: 2–3

About US$60 million was initially spent with governmental funding, but only 1,000 acres (400 ha) of the Idlewild Golf Course site were earmarked for use.[22] The project was renamed Major General Alexander E. Anderson Airport in 1943 after a Queens resident who had commanded a Federalized National Guard unit in the southern United States and died in late 1942. The renaming was vetoed by Mayor La Guardia and reinstated by the New York City Council; in common usage, the airport was still called "Idlewild".[23] In 1944, the New York City Board of Estimate authorized the condemnation of another 1,350 acres (550 ha) for Idlewild.[24] The Port of New York Authority (now the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey) leased the Idlewild property from the City of New York in 1947[18]: 3 and maintains this lease today.[1] In March 1948, the City Council changed the official name to New York International Airport, Anderson Field, but the common name remained "Idlewild" until December 24, 1963.[16][25] The airport was intended as the world's largest and most efficient, with "no confusion and no congestion".[18]: 3 [26]

Early operations[edit]

The first flight from Idlewild was on July 1, 1948, with the opening ceremony attended by U.S. President Harry S. Truman and Governor of New York Thomas E. Dewey,[22][27] who were both running for president in that year's presidential election. The Port Authority canceled foreign airlines' permits to use LaGuardia, forcing them to move to Idlewild during the next couple of years.[28] Idlewild at the time had a single 79,280-square-foot (7,365 m2) terminal building;[18]: 3 by 1949, the terminal building was being expanded to 215,501 square feet (20,021 m2).[29] Further expansions would come in following years, including a control tower in 1952,[30] as well as new and expanded buildings and taxiways.[31][32]

Idlewild opened with six runways and a seventh under construction;[33] runways 1L and 7L were held in reserve and never came into use as runways. Runway 31R (originally 8,000 ft or 2,438 m) is still in use; runway 31L (originally 9,500 ft or 2,896 m) opened soon after the rest of the airport and is still in use; runway 1R closed in 1957 and runway 7R closed around 1966. Runway 4 (originally 8,000 ft, now runway 4L) opened June 1949 and runway 4R was added ten years later. A smaller runway 14/32 was built after runway 7R closed and was used until 1990[34] by general aviation, STOL, and smaller commuter flights.

The Avro Jetliner was the first jet airliner to land at Idlewild on April 16, 1950. A Sud Aviation Caravelle prototype was the next jet airliner to land at Idlewild, on May 2, 1957. Later in 1957, the USSR sought approval for two jet-powered Tupolev Tu-104 flights carrying diplomats to Idlewild; the Port Authority did not allow them, saying noise tests had to be done first. (The Caravelle had been tested at Paris.)

In 1951, the airport averaged 73 daily airline operations (takeoffs plus landings); the October 1951 Airline Guide shows nine domestic departures a day on National and Northwest. Much of Newark Airport's traffic shifted to Idlewild (which averaged 242 daily airline operations in 1952) when Newark was temporarily closed in February 1952 after a series of three plane crashes in the two preceding months in Elizabeth, all of which had fatalities; flights were shifted to Idlewild and La Guardia, which could have planes takeoff and land over the water, rather than over the densely populated areas surrounding Newark Airport.[35] The airport remained closed in Newark until November 1952, with new flight patterns that took planes away from Elizabeth.[36] L-1049 Constellations and DC-7s appeared between 1951 and 1953 and did not use LaGuardia for their first several years, bringing more traffic to Idlewild. The April 1957 Airline Guide cites a total of 1,283 departures a week, including about 250 from Eastern Air Lines, 150 from National Airlines and 130 from Pan American.[full citation needed]

Separate terminals[edit]

By 1954, Idlewild had the highest volume of international air traffic of any airport globally.[18]: 3 [37] The Port of New York Authority originally planned a single 55-gate terminal, but the major airlines did not agree with this plan, arguing that the terminal would be far too small for future traffic.[38] Architect Wallace Harrison then designed a plan for each major airline at the airport to be given its own space to develop its own terminal.[39] This scheme made construction more practical, made terminals more navigable, and introduced incentives for airlines to compete with each other for the best design.[38] The revised plan met airline approval in 1955, with seven terminals initially planned. Five terminals were for individual airlines, one was for three airlines, and one was for international arrivals (National Airlines and British Airways arrived later).[25] In addition, there would be an 11-story control tower, roadways, parking lots, taxiways, and a reflecting lagoon in the center.[18]: 3 The airport was designed for aircraft up to 300,000-pound (140,000 kg) gross weight[40] The airport had to be modified in the late 1960s to accommodate the Boeing 747's weight.[41]

The International Arrivals Building, or IAB, was the first new terminal at the airport, opening in December 1957.[42] The building was designed by Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill (SOM).[18]: 3 The terminal stretched nearly 2,300 feet (700 meters) and was parallel to runway 7R. The terminal had "finger" piers at right-angles to the main building allowing more aircraft to park, an innovation at the time.[25] The building was expanded in 1970 to accommodate jetways. However, by the 1990s the overcrowded building was showing its age and it did not provide adequate space for security checkpoints. It was demolished in 2000 and replaced with Terminal 4.

United Airlines and Delta Air Lines[43] opened Terminal 7 (later renumbered Terminal 9), a SOM design similar to the IAB,[18]: 3–4 in October 1959.[44] It was demolished in 2008.

Eastern Air Lines opened their Chester L. Churchill-designed Terminal 1[18]: 4 in November 1959.[45] The terminal was demolished in 1995 and replaced with the current Terminal 1.[25][46]

American Airlines opened Terminal 8 in February 1960.[47] It was designed by Kahn and Jacobs[18]: 3 [25] and had a 317-foot (97 m) stained-glass facade designed by Robert Sowers,[48] the largest stained-glass installation in the world until 1979. The facade was removed in 2007 as the terminal was demolished to make room for the new Terminal 8; American cited the prohibitive cost of removing the enormous installation.[49]

Pan American World Airways opened the Worldport (later Terminal 3) in 1960, designed by Tippetts-Abbett-McCarthy-Stratton.[18]: 4 [50] It featured a large, elliptical roof suspended by 32 sets of radial posts and cables; the roof extended 114 feet (35 m) beyond the base of the terminal to cover the passenger loading area. It was one of the first airline terminals in the world to feature jetways that connected to the terminal and that could be moved to provide an easy walkway for passengers from the terminal to a docked aircraft. Jetways replaced the need to have to board the plane outside via airstairs that descend from an aircraft, truck-mounted mobile stairs, or wheeled stairs.[51] The Worldport was demolished in 2013.

Trans World Airlines opened the TWA Flight Center in 1962, designed by Eero Saarinen with a distinctive winged-bird shape.[52][53] With the demise of TWA in 2001, the terminal remained vacant until 2005 when JetBlue and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) financed the construction of a new 26-gate terminal partly encircling the Saarinen building. Called Terminal 5 (Now T5), the new terminal opened October 22, 2008. T5 is connected to the Saarinen central building through the original passenger departure-arrival tubes that connected the building to the outlying gates. The original Saarinen terminal, also known as the head house, has since been converted into the TWA Hotel.[54]

Northwest Orient, Braniff International Airways, and Northeast Airlines opened a joint terminal in November 1962 (later Terminal 2).[51][55]

National Airlines opened the Sundrome (later Terminal 6) in 1969.[56] The terminal was designed by I.M.Pei. It was unique for its use of all-glass mullions dividing the window sections, unprecedented at the time.[57] On October 30, 2000, United Airlines and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey announced plans to redevelop this terminal and the TWA Flight Center as a new United terminal.[58] Terminal 6 was used by JetBlue from 2001 until JetBlue moved to Terminal 5 in 2008. The Sundrome was demolished in 2011.

Later operation[edit]

The airport was renamed John F. Kennedy International Airport on December 24, 1963, a month and two days after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy;[59] Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. proposed the renaming.[60] The IDL and KIDL codes have since been reassigned to Indianola Municipal Airport in Mississippi, and the now-renamed Kennedy Airport was given the codes JFK and KJFK, the fallen president's initials.[61]

Airlines began scheduling jets to Idlewild in 1958–59; LaGuardia did not get jets until 1964, and JFK became New York's busiest airport. It had more airline takeoffs and landings than LaGuardia and Newark combined from 1962 to 1967 and was the second-busiest airport in the country, peaking at 403,981 airline operations in 1967. LaGuardia received a new terminal and longer runways from 1960 to 1966. By the mid-1970s, the two airports had roughly equal airline traffic (by flight count); Newark was in third place until the 1980s, except during LaGuardia's reconstruction. Concorde, operated by Air France and British Airways, made scheduled trans-Atlantic supersonic flights to JFK from November 22, 1977, until its retirement by British Airways on October 24, 2003.[62][63] Air France had retired the aircraft in May 2003.

Construction of the AirTrain JFK people-mover system began in 1998, after decades of planning for a direct rail link to the airport.[64][65] Although the system was originally scheduled to open in 2002,[66] it opened on December 17, 2003, after delays caused by construction and a fatal crash.[67] The rail network links each airport terminal to the New York City Subway and the Long Island Rail Road at Howard Beach and Jamaica.[68][69]

The airport's new Terminal 1 opened on May 28, 1998; Terminal 4, the $1.4 billion replacement for the International Arrivals Building, opened on May 24, 2001.[70][71] JetBlue's Terminal 5 incorporates the TWA Flight Center, and Terminals 8 and 9 were demolished and rebuilt as Terminal 8 for the American Airlines hub. The Port Authority Board of Commissioners approved a $20 million planning study for the redevelopment of Terminals 2 and 3, the Delta Air Lines hub, in 2008.[72]

On March 19, 2007, JFK was the first airport in the United States to receive a passenger Airbus A380 flight. The route, with an over-500-passenger capacity, was operated by Lufthansa and Airbus and arrived at Terminal 1. On August 1, 2008, it received the first regularly scheduled commercial A380 flight to the United States (on Emirates' New York–Dubai route) at Terminal 4.[73] Although the service was suspended in 2009 due to poor demand,[74] the aircraft was reintroduced in November 2010. Airlines operating A380s to JFK include Singapore Airlines (on its New York–Frankfurt–Singapore route),[75] Air France (on its New York–Paris route), Lufthansa (on its New York–Frankfurt route), Korean Air (on its New York–Seoul route), Asiana Airlines (on its New York–Seoul route), Etihad Airways (on its New York–Abu Dhabi route), and Emirates (on its New York–Milan–Dubai and New York–Dubai routes).[76] On December 8, 2015, JFK was the first U.S. airport to receive a commercial Airbus A350 flight when Qatar Airways began using the aircraft on one of its New York–Doha routes.[77]

The airport currently hosts the world's longest flight, Singapore Airlines Flights 23 and 24 (SQ23 and SQ24). The route was launched in 2020 between Singapore and New York JFK, and uses the Airbus A350-900ULR.

Major robberies[edit]

The Air France robbery took place in April 1967 when associates of the Lucchese crime family stole $420,000 (equivalent of approximately $3.8 million in 2023) from the Air France cargo terminal at the airport. It was the largest cash robbery in the United States at the time. It was carried out by Henry Hill, Robert McMahon, Tommy DeSimone and Montague Montemurro, on a tip-off from McMahon. Hill believed it was the Air France robbery that endeared him to the Mafia.[78]

Air France was contracted to transport American currency that had been exchanged in Southeast Asia for deposit in the United States. Their aircraft regularly delivered three or four $60,000 packages at a time. Hill and associates obtained a key to a cement-block strong room where the money was stored. They entered the unsecured cargo terminal and entered the strong room unchallenged. They took seven bags in a large suitcase. The theft was not discovered until the following Monday.[79]

The Lufthansa heist took place on December 11, 1978, at the airport. The robbery netted an estimated US$5.875 million (equivalent to US$27.4 million in 2023), including US$5 million in cash and US$875,000 in jewelry. It was the largest cash robbery committed on American soil at the time.[80][81]

James Burke, an associate of the Lucchese crime family of New York, was believed to be the mastermind behind the robbery, but was never charged with the crime. Burke is also alleged to have either committed or ordered the murders of many in the robbery, both to avoid being implicated in the heist and to keep their shares of the money for himself.[82] The only person convicted in the Lufthansa heist was Louis Werner, an airport worker involved with the planning.[82]

The money and jewelry have never been recovered. The heist's magnitude made it one of the longest-investigated crimes in U.S. history; the latest arrest associated with the robbery was made in 2014, which resulted in acquittal.

Access[edit]

Rail[edit]

All lines of AirTrain JFK, the airport's dedicated rail network, stop at each passenger terminal. The system also serves Federal Circle, the JFK long-term parking lot, and two multimodal rapid transit stations: Howard Beach and Jamaica. While AirTrain travel within airport property is complimentary, external transfers at the latter two locations are paid via OMNY or MetroCard and provide access to the New York City Subway, Long Island Rail Road, and MTA Bus services.

Bus[edit]

As of 2022[update], only the Q3 bus serves Terminal 8. The Q6, Q7 serve JFK's cargo terminals. The Q10 and B15 serve the Lefferts Boulevard station on the AirTrain and it includes a free transfer. The B15, Q3, and Q10 buses will return to Terminal 5 in 2026 due to construction. Bus fares are paid via OMNY or MetroCard, with free transfers provided to New York City Subway services.

Vehicle[edit]

Vehicles primarily access the airport via the Van Wyck Expressway (I-678) or JFK Expressway, both of which are connected to the Belt Parkway and various surface streets in South Ozone Park and Springfield Gardens. The airport operates parking facilities consisting of multi-level terminal garages, surface spaces in the Central Terminal Area, and a long-term parking lot with total accommodation for more than 17,000 vehicles.[83] A travel plaza on airport property also contains a food court, filling station, and originally four Tesla Superchargers.[84] The original 4 Tesla Superchargers were later replaced with a new station with 12 stalls.[85]

Taxis and other for-hire vehicles (FHV) serving JFK are licensed by the New York City Taxi & Limousine Commission. In 2019, PANYNJ approved the implementation of "airport access fee" surcharges on FHV and taxi trips, with the revenue earmarked to support the agency's capital programs.[86]

Terminals[edit]

Overview[edit]

JFK has five active terminals, containing 130 gates in total. The terminals are numbered 1–8 but skipping terminals 2 (demolished in 2023), 3 (demolished in 2013) and 6 (demolished in 2011).

The terminal buildings, except for the former Tower Air terminal, are arranged in a deformed U-shaped wavy pattern around a central area containing parking, a power plant, and other airport facilities. The terminals are connected by the AirTrain system and access roads. Directional signage throughout the terminals was designed by Paul Mijksenaar.[87] A 2006 survey by J.D. Power and Associates in conjunction with Aviation Week found that JFK ranked second in overall traveler satisfaction among large airports in the United States, behind Harry Reid International Airport, which serves the Las Vegas metropolitan area.[88]

Until the early 1990s, each terminal was known by the primary airline that served it, except for Terminal 4, which was known as the International Arrivals Building. In the early 1990s, all terminals were given numbers except for the Tower Air terminal, which sat outside the Central Terminals area and was not numbered. Like the other airports controlled by the Port Authority, JFK's terminals are sometimes managed and maintained by independent terminal operators. At JFK, all terminals are managed by airlines or consortiums of the airlines serving them, except for the Schiphol Group-operated Terminal 4. All terminals can handle international arrivals that are not pre-cleared.

Most inter-terminal connections require passengers to exit security, then walk, use a shuttle bus, or use the AirTrain JFK to get to the other terminal, then re-clear security.

Terminal 1[edit]

Terminal 1 opened in 1998, 50 years after the opening of JFK, at the direction of the Terminal One Group, a consortium of four key operating carriers: Air France, Japan Airlines, Korean Air, and Lufthansa.[89] This partnership was founded after the four airlines reached an agreement that the then-existing international carrier facilities were inadequate for their needs. The Eastern Air Lines terminal was located on the site of present-day Terminal 1.[90]

Terminal 1 is served by SkyTeam carriers Air France, China Eastern Airlines, ITA Airways, Korean Air, and Saudia; Star Alliance carriers Air China, Air New Zealand, Asiana Airlines, Austrian Airlines, Brussels Airlines, Egyptair, EVA Air, Lufthansa, Scandinavian Airlines, Swiss International Air Lines, TAP Air Portugal, and Turkish Airlines; and Oneworld carrier Royal Air Maroc. Other airlines serving Terminal 1 include Air Senegal, Air Serbia, Azores Airlines, Cayman Airways, Flair Airlines, Neos, Philippine Airlines, VivaAerobús, and Volaris.[91]

Terminal 1 was designed by William Nicholas Bodouva + Associates.[92] It and Terminal 4 are the two terminals at JFK Airport with the capability of handling the Airbus A380 aircraft, which Korean Air flies on the route from Seoul–Incheon and Lufthansa from Munich. Air France operated Concorde here until 2003.[93] Terminal 1 has 11 gates.[94]

Terminal 4[edit]

Terminal 4, developed by LCOR, Inc., is managed by JFKIAT (IAT) LLC, a subsidiary of the Schiphol Group and was the first in the United States to be managed by a foreign airport operator. Terminal 4 currently contains 48 gates in two concourses and functions as the hub for Delta Air Lines at JFK.

- Concourse A (gates A2–A12, A14–A17, A19, and A21) serves primarily Asian and some European airlines along with Delta Connection flights.

- Concourse B (gates B20, B22-B55) primarily serves both domestic & international flights of Delta and its SkyTeam partners.

Airlines servicing Terminal 4 include SkyTeam carriers Aeromexico, Air Europa, China Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Kenya Airways, KLM, and Virgin Atlantic; Star Alliance carriers Air India, Avianca, Copa Airlines, and Singapore Airlines; and non-alliance carriers Caribbean Airlines, El Al, Emirates, Etihad Airways, Hawaiian Airlines, JetBlue (late night international arrivals only), LATAM Brasil, LATAM Chile, LATAM Peru, Uzbekistan Airways, and WestJet.[91] Like Terminal 1, the facility is Airbus A380-compatible with service currently provided by Emirates to Dubai; both non-stop and one-stop via Milan and Etihad Airways to Abu Dhabi.

Opened in early 2001 and designed by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill,[95] the 1.5-million-square-foot (140,000 m2) facility was built for $1.4 billion and replaced JFK's old International Arrivals Building (IAB), which opened in 1957 and was designed by the same architectural firm. The new construction incorporated a mezzanine-level AirTrain station, an expansive check-in hall, and a four-block-long retail area.[96]

Terminal 4 has seen multiple expansions over the years. On May 24, 2013, the completion of a $1.4 billion project added mechanized checked-bag screening, a centralized security checkpoint (consolidating two checkpoints into one new fourth-floor location), nine international gates, improved U.S. Customs and Border Protection facilities, and, at the time, the largest Sky Club lounge in Delta's network.[97][98][99][100] Later that year, the expansion also improved passenger connectivity with Terminal 2 by bolstering inter-terminal JFK Jitney shuttle bus service and building a dedicated 8,000 square-foot bus holdroom facility adjacent to gate B20.[101] Also in 2013, Delta, JFKIAT and the Port Authority agreed[102] to a further $175 million Phase II expansion, which called for 11 new regional jet gates to supersede capacity previously provided by the soon-to-be-demolished Terminal 2 hardstands and Terminal 3. Delta sought funding from the New York City Industrial Development Agency,[102] and work on Phase II was completed in January 2015.

By 2017, plans to expand Terminal 4's passenger capacity were being floated in conjunction with a more significant JFK modernization proposal. In early 2020, Governor Cuomo announced that the Port Authority and Delta/IAT had agreed to terms extending Concourse A by 16 domestic gates, renovating the arrival/departure halls, and improving land-side roadways for $3.8 billion.[103] By April 2021, that plan had been scaled-back to $1.5 billion worth of improvements as a result of financial hardships imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The revised plan called for arrival/departure hall modernization and just ten new gates in Concourse A. Consolidation of Delta's operations within T4 occurred in early 2023, along with the new gates opening.[104][105] Delta also opened a new Sky Club in Concourse A. The airline plans to open a lounge exclusive to Delta One customers by June 2024. It would be the largest in the airline's network.[106]

In 2019, American Express began construction of a Centurion lounge that subsequently opened in October 2020.[107] The structural addition extends the headhouse between the control tower and gate A2, and includes 15,000 square-feet of dining, bars, and fitness facilities.

Terminal 5[edit]

Terminal 5 opened in 2008 for JetBlue, the manager and primary tenant of the building, as the base of its large JFK operating base. The terminal is also used by Cape Air.[91] On November 12, 2014, JetBlue opened the International Arrivals Concourse (T5i) at the terminal.[108]

The terminal was redesigned by Gensler and constructed by Turner Construction, and sits behind the preserved Eero Saarinen-designed terminal originally known as the TWA Flight Center, which is now connected to the new structure and is considered part of Terminal 5.[109][110][111] The TWA Flight Center reopened as the TWA Hotel in May 2019. The active Terminal 5 building has 29 gates: 1 through 12 and 14 through 30, with gates 25 through 30 handling international flights that are not pre-cleared (gates 28–30 opened in November 2014).[112]

Aer Lingus opened an airport lounge in 2015.[113] The terminal opened a rooftop lounge open to all passengers in 2015, T5 Rooftop & Wooftop Lounge, located near Gate 28.[114][115] In August 2016, Fraport USA was selected by JetBlue as the concessions developer to help attract and manage concessions tenants that align with JetBlue's vision for Terminal 5.[116] During the summer of 2016, JetBlue renovated Terminal 5, completely overhauling the check-in lobby.[117]

Terminal 7[edit]

Terminal 7 was designed by GMW Architects[118] and built for British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) and Air Canada in 1970. Formerly, the terminal was operated by British Airways, and was also the only airport terminal operated on US soil by a foreign carrier. British Airways operated Concorde here until 2003. Terminal 7 is now operated by a consortium of foreign carriers serving the building.

Airlines operating out of Terminal 7 include Oneworld carrier Alaska Airlines; Star Alliance carriers Air Canada Express, All Nippon Airways, Ethiopian Airlines and LOT Polish Airlines; SkyTeam carrier Aerolíneas Argentinas; and non-alliance carriers Aer Lingus, Condor, Icelandair, Kuwait Airways, Norse Atlantic Airways, and Sun Country Airlines.[91]

Between 1989 and 1991, the terminal was renovated and expanded for $120 million.[119] The expansion was designed by William Nicholas Bodouva + Associates, Architects.[92] In 1997, the Port Authority approved British Airways' plans to renovate and expand the terminal. The $250 million project[120] was designed by Corgan Associates[121] and was completed in 2003.[122] The renovated terminal has 12 gates.[120]

In 2015, British Airways extended its lease on the terminal through 2022, with an option of a further three years.[123] BA also planned to spend $65 million to renovate the terminal.[124] Despite being operated by British Airways, a major A380 operator, Terminal 7 is not currently able to handle the aircraft type. As a result, British Airways could not operate A380s on the lucrative London-Heathrow to New York flights, even though in 2014, there was an advertising campaign that British Airways was going to do so.[124] British Airways planned to join its Oneworld partners in Terminal 8,[125] however, and did not exercise its lease options on Terminal 7. The terminal is now operated by JFK Millennium Partners, a consortium including JetBlue, RXR Realty, and Vantage Airport Group, who will eventually demolish the current terminal. At the same time, a new Terminal 6 will begin to be built to serve as a direct replacement.[126]

In late 2020 United Airlines announced they would return to JFK in February 2021 after a 5-year hiatus. As of March 28, 2021, United operated transcontinental nonstop service from Terminal 7 to its west coast hubs in San Francisco and Los Angeles.[127] On October 29, 2022, however, United suspended service to JFK once again.

Terminal 8[edit]

Terminal 8 is a major Oneworld hub with American operating its hub here. In 1999, American Airlines began an eight-year program to build the largest passenger terminal at JFK, designed by DMJM Aviation to replace both Terminal 8 and Terminal 9. The new terminal was built in four phases, which involved the construction of a new midfield concourse and the demolition of old Terminals 8 and 9. It was built in stages between 2005 and its official opening in August 2007.[128] American Airlines, the third-largest carrier at JFK, manages Terminal 8 and is the largest carrier at the terminal. Other Oneworld airlines that operate out of Terminal 8 include British Airways, Cathay Pacific, Finnair, Iberia, Japan Airlines, Qantas, Qatar Airways, and Royal Jordanian. Non-alliance carrier China Southern Airlines also uses the terminal.[91]

In 2019, it was announced that British Airways and Iberia would move into Terminal 8 preceding the demolition of Terminal 7 and that the terminal would be expanded and changed to accommodate more widebody aircraft that British Airways, Iberia and other Oneworld airlines regularly send to JFK. On January 7, 2020, construction began expanding and improving Terminal 8 with construction completed in 2022. This construction marked the first phase in the airport's expansion; the terminal having the same number of gates as before, plus four hardstands.[129] British Airways began operating some flights out of Terminal 8 on November 17, 2022, while all flights moved from Terminal 7 on December 1, 2022.[130][125][131] Iberia also moved to Terminal 8 on December 1, while Japan Airlines moved to the terminal on May 28, 2023.[132]

The terminal is twice the size of Madison Square Garden. It offers dozens of retail and food outlets, 84 ticket counters, 44 self-service kiosks, ten security checkpoint lanes, and a U.S. Customs and Border Protection facility that can process more than 1,600 people an hour. Terminal 8 has an annual capacity of 12.8M passengers.[133] It has one American Airlines Admirals Club and three lounges for premium class passengers as well as frequent flyers (Greenwich, Soho, and Chelsea lounges).[134]

Terminal 8 has 31 gates: 14 gates in Concourse B (1–8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, and 20) and 17 gates in Concourse C (31–47).[135] Passenger access to and from Concourse C is by a tunnel that includes moving walkways.

Reconstruction[edit]

On January 4, 2017, the office of then-New York governor Andrew Cuomo announced a plan to renovate most of the airport's existing infrastructure for $7 to $10 billion. The Airport Master Plan Advisory Panel had reported that JFK, ranked 59th out of the world's top 100 airports by Skytrax, was expected to experience severe capacity constraints from increased use.[136][137] The airport was expected to serve about 75 million annual passengers in 2020 and 100 million by 2050, up from 60 million when the report was published.[136] The panel had several recommendations, including enlarging the newer terminals; relocating older terminals; reconfiguring highway ramps and increasing the number of lanes on the Van Wyck Expressway; lengthening AirTrain JFK trainsets or connecting the line to the New York City transportation system, and rebuilding the Jamaica station with direct connections to the Long Island Rail Road and the New York City Subway.[138] No start date has yet been proposed for the project;[137] in July 2017, Cuomo's office began accepting proposals for master plans to renovate the airport.[139][140] When all the construction is finished, the airport will have 149 total gates: 145 with jetways and four hardstands. Notably, previous plans included adding cars to AirTrain trainsets; widening connector ramps between the Van Wyck Expressway and Grand Central Parkway in Kew Gardens; and adding another lane in each direction to the Van Wyck, at a combined cost of $1.5 billion.[141][142] It is unclear how many, if any, of those proposals are still being considered.

New Terminal 1[edit]

In October 2018, Cuomo released details of a $13 billion plan to rebuild passenger facilities and approaches to JFK Airport. Two all-new international terminals would be built. One of the terminals, a $7 billion, 2.8-million-square-foot (260-thousand-square-metre), 23-gate structure replacing Terminals 1, 2 and the vacant space of Terminal 3. It will connect to Terminal 4, and it would be financed and built by a partnership between Munich Airport Group, Lufthansa, Air France, Korean Air, and Japan Airlines. Of these 23 gates, all are international gates, 22 are widebody gates (4 can accommodate an Airbus A380), and 1 is a narrowbody gate. This would also require reconfiguring new roads to accommodate the new terminal.[141][143]

On December 13, 2021, New York Governor Kathy Hochul gave a further update on the plans to build a new Terminal 1, which in a further developed form would cost US$9.5 billion. The new facility is inspired by the new Terminal B at LaGuardia Airport. The new terminal will have New York City-inspired art, similar to Terminal B at LGA. The New Terminal 1 began construction on September 8, 2022 and will open in phases with the first 14 gates on its east side along with the departures and arrivals hall scheduled to open in 2026 on the site of the demolished Terminal 2.[144] The current Terminal 1 will then be demolished, and in its place, the next five gates on the west side of the terminal will open in 2028, and the final four gates will open in 2030. An additional extension of the terminal on its west side with a further four gates (with an extra A380 gate) has been proposed in the event of excess traffic.

Expanded Terminal 4[edit]

On February 11, 2020, Cuomo and the Port Authority, along with Delta Air Lines, announced a $3.8 billion plan to add sixteen domestic, regional gates to the 'A' side of Terminal 4, replacing Terminal 2. The main headhouse would have been expanded to accommodate additional passengers and open in 2022. The airport finished construction on a downsized plan in 2023, allowing the demolition of Terminal 2, the consolidation of flights for Delta, and the ability to build the new Terminal 1. An expanded roadway will be completed in 2025. [145] Delta consolidated their operations into Terminal 4 in January 2023, along with opening 10 new gates in Terminal 4's Concourse A. An additional expansion to Concourse B is expected to be completed by Fall 2023.[105]

New Terminal 6[edit]

Construction on a new Terminal 6 began in February 2023.[146][147] The terminal was designed by Corgan and will have ten gates, nine of which will be wide-body gates.[148] The terminal will be opened in multiple phases; the first phase is expected to be completed by 2026 and, as of November 2022[update], is projected to cost $4.2 billion.[149] The full terminal is expected to open in 2028.[149] The new terminal will connect to Terminal 5; Terminal 7 will be demolished after the new Terminal 6's first phase of construction is completed. The construction will be built under a public–private partnership between the Port Authority and a consortium, known as JFK Millennium Partners, comprising JetBlue, RXR Realty, and Vantage Airport Group.

Former terminals[edit]

JFK Airport was originally built with ten terminals, compared to the five it has today. Ten terminals remained until the late 1990s, then nine remained until the early 2000s, followed by eight until 2011, seven until 2013 and six until 2023.

Terminal 1 (1959–1995)[edit]

The original Terminal 1 opened in November 1959, for Eastern Air Lines. It was designed by Chester L. Churchill. Eastern was the primary tenant of this terminal until its collapse on January 19, 1991. Shortly after Eastern's collapse, the terminal became vacant until it was finally demolished in 1995.[150] It was located on the site of today's Terminal 1, which opened in 1998.

Terminal 2 (1962–2023)[edit]

Terminal 2 opened in November 1962 as the home of Northeast Airlines, Braniff International Airways, and Northwest Orient, and was last occupied by Delta Air Lines. The facility contained 11 jetbridge-equipped gates (C60–C70) and one mezzanine-level airline club, and it formerly housed several hardstands for smaller regional airliners. The terminal did not have a U.S. Customs and Border Protection processing facility, and was unable to accept any international flights arriving unless subject to US Customs preclearance. It was designed by the architectural firm White & Mariani.[90]

Delta moved over to Terminal 2 following the merger with Northeast Airlines swapping places with Braniff, Pan Am moved its domestic flights to this terminal in 1986. Upon the completion of Terminal 4, T2's gates were prefaced with the letter 'C', and airside shuttle buses provided passenger connectivity between the terminals. Before 2013, Terminal 2 hosted most of Delta's operations in conjunction with Terminal 3. Still, the 2013–2015 expansion of Terminal 4 allowed the airline to consolidate most of its operations in the new larger facility, including international and transcontinental flights.[151] In mid-2020, following drastic schedule reductions in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Delta suspended all operations from Terminal 2; the terminal re-opened to flights in July 2021.[152] Terminal 2 permanently closed for departures on January 10, 2023, and for arrivals on January 15, 2023. Terminal 2 was demolished to make room for the new Terminal 1.[104][153]

Terminal 3 (1960–2013)[edit]

Terminal 3 opened as the Worldport on May 24, 1960, for Pan American World Airways (Pan Am); it expanded after the introduction of the Boeing 747 in 1971. After Pan Am's demise in 1991, Delta Air Lines took over ownership of the terminal and was its only occupant until its closure on May 23, 2013. It had a connector to Terminal 2, Delta's other terminal, used mainly for domestic flights. Terminal 3 had 16 Jetway-equipped gates: 1–10, 12, 14–18 with two hardstand gates (Gate 11) and a helipad on Taxiway KK.

A $1.2 billion project was completed in 2013, under which Terminal 4 was expanded, and Delta subsequently moved its T3 operations to T4.

On May 23, 2013, the final departure from the terminal, Delta Air Lines Flight 268, a Boeing 747-400 to Tel Aviv Ben Gurion Airport, departed from Gate 6 at 23:25 local time.[154] The terminal ceased operations on May 24, 2013,[154] exactly fifty-three years after its opening.[155] Demolition began soon after that and was completed by Summer 2014. The site where Terminal 3 used to stand is now used for aircraft parking by Delta Air Lines.

There has been a major media outcry, particularly in other countries, over the demolition of the Worldport. Several online petitions requesting the restoration of the original 'flying saucer' gained popularity.[156][157][158][159]

International Arrivals Building[edit]

The International Arrivals Building (IAB) was opened in December 1957 and was replaced with the new Terminal 4 in 2001. It was designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.[90]

TWA Flight Center[edit]

The TWA Flight Center was opened in 1962 and closed in 2001 after its primary tenant, Trans World Airlines, went out of business; the terminal had seen increased capacity issues in the years prior.[160] It was designed by renowned architect Eero Saarinen, with extensions designed by Roche-Dinkeloo opening in 1970.[90][161]

The TWA Flight Center was not demolished after closure,[162] as it had been named a New York City designated landmark in 1994.[163] Instead, it sat abandoned until it was incorporated into the current JetBlue Terminal 5.[164] It was then converted into the Jet Age-themed TWA Hotel, which opened in 2019.[165]

Terminal 6 (1969–2011)[edit]

Terminal 6 opened as the Sundrome on November 30, 1969, for National Airlines. National was the tenant of this terminal until it was fully acquired by Pan American World Airways (Pan Am) on January 7, 1980. Terminal 6 had 14 gates. It was designed by architect I.M. Pei.

Trans World Airlines (TWA) then expanded into the terminal, referring to it as the TWA Terminal Annex, later called TWA Domestic Terminal. It was eventually connected to the TWA Flight Center. Later, after TWA reduced flights at JFK, Terminal 6 was used by United Airlines (SFO and LAX transcontinental flights), ATA Airlines, a reincarnated Pan Am II, Carnival Air Lines, Vanguard Airlines, and America West Airlines.

In 2000, JetBlue began service from Terminal 6, later opening a temporary complex in 2006 that increased its capacity by adding seven gates. Until 2008, JetBlue was the tenant of Terminal 6. It became vacant on October 22, 2008, when JetBlue moved to Terminal 5 and was finally demolished in 2011.[166] The international arrivals annex of Terminal 5 now uses a portion of the site, and the rest of the site is used for aircraft parking by JetBlue, but will be occupied by the new Terminal 6, an annex to Terminal 5, planned to be fully opened by 2027.[126]

Terminal 8 (1960–2008)[edit]

The original Terminal 8 opened in February 1960; its stained-glass façade was the largest at the time. It was always used by American Airlines, and, in later years, it was used by other Oneworld airlines that did not use Terminal 7. This terminal, along with Terminal 9, was demolished in 2008 and replaced with the current Terminal 8.

Terminal 9 (1959–2008)[edit]

Terminal 9 opened in October 1959 as the home of United Airlines[25] and Delta Air Lines.[43] Delta moved to Terminal 2 in 1972 when it fully acquired Northeast Airlines.[167] Braniff International Airways moved from Terminal 2 to Terminal 9 in 1972 after swapping terminals with Delta. It operated out of Terminal 9 until its collapse on May 12, 1982.[168] United used Terminal 9 from its opening in 1959 until it vacated the terminal in 1991 and became a tenant at British Airways' Terminal 7. Northwest Airlines used Terminal 9 from 1986 to 1991.[169][170] Terminal 9 became the home of American Airlines' domestic operations and American Eagle flights for the remainder of its life. This terminal, along with the original Terminal 8, was demolished in 2008 and replaced with the current Terminal 8.[128]

Tower Air terminal[edit]

The Tower Air terminal, unlike other terminals at JFK Airport, sat outside the Central Terminals area in Building 213 in Cargo Area A. Originally used by Pan Am until the expansion of the Worldport (later Terminal 3), it was later used by Tower Air and TWA shuttle until the airline was acquired by American Airlines in 2001. Building 213 has not been used since 2000.

Runways and taxiways[edit]

The airport covers 5,200 acres or 21 square kilometers (8.1 sq mi).[6][171] Over 25 miles (40 km) of paved taxiways allow aircraft to move around the airfield.[citation needed] The standard width of these taxiways is 75 feet (23 m), with 25 feet (7.6 m) heavy-duty shoulders and 25-foot (7.6 m) erosion control pavement on each side. The taxiways are generally of asphalt concrete composition 15 to 18 inches (380 to 460 mm) thick. Painted markings, lighted signage, and embedded pavement lighting, including runway status lights, provide both position and directional information for taxiing aircraft. There are four runways (two pairs of parallel runways) surrounding the airport's central terminal area.[2]

| Number | Length | Width | ILS | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13R/31L | 14,511 feet (4,423 m) | 200 feet (61 m) | Cat. I (31L) | Third-longest commercial runway in North America (the longest is a 16,000-foot (4,900 m) runway at Denver International Airport, and the second longest is a 14,512-foot (4,423 m) runway at Las Vegas Harry Reid International Airport). Adjacent to Terminals 1, 2, and 3. Handled approximately one-half of the airport's scheduled departures. It was a backup runway for Space Shuttle missions.[172] It was closed on March 1, 2010, for four months. The reconstruction of the runway widened it from 150 to 200 feet (46 to 61 m) with a concrete base instead of asphalt. It reopened on June 29, 2010.[173] |

| 13L/31R | 10,000 feet (3,048 m) | 200 feet (61 m) | Cat. II (13L); Cat. I (31R) | Adjacent to Terminals 5 and 7. Equipped at both ends with ILS and ALS systems. Runway 13L has two additional visual aids for landing aircraft, a Precision Approach Path Indicator (PAPI) and a Lead-In Lighting System (LDIN); the LDIN is colloquially known as the Canarsie approach for the CRI VOR beacon, which marks its beginning. The ILS on 13L, along with TDZ lighting, allows landings down to half a mile's visibility. Takeoffs can be made with a visibility of one-eighth of a mile. It closed on April 1, 2019, for almost eight months as part of a significant runway modernization project that replaced the asphalt base with a concrete floor and widened the runway from 150 to 200 feet (46 to 61 m). It reopened on November 16, 2019.[174][175] |

| 4R/22L | 8,400 feet (2,560 m) | 200 feet (61 m) | Cat. III (both directions) | Equipped at both ends with Approach Lighting Systems (ALS) with sequenced flashers and touchdown zone (TDZ) lighting. The first Engineered Materials Arresting System (EMAS) in North America was installed at the northeast end of the runway in 1996. The bed consists of cellular cement material, which can safely decelerate and stop an aircraft that overruns the runway. The arrestor bed concept was originated and developed by the Port Authority and installed at JFK Airport as a joint research and development project with the FAA and industry. |

| 4L/22R | 12,079 feet (3,682 m) | 200 feet (61 m) | Cat. I (both directions) | Adjacent to Terminals 4 and 5. Both ends allow instrument landings down to three-quarters of a mile's visibility. Takeoffs can be conducted with one-eighth of a mile's visibility. It closed on June 1, 2015, for almost four months as part of a significant runway modernization project that replaced the asphalt base with a concrete base and widened the runway from 150 to 200 feet (46 to 61 m). It reopened on September 28, 2015.[176] |

Operational facilities[edit]

[edit]

The air traffic control tower, designed by Pei Cobb Freed & Partners and constructed on the ramp-side of Terminal 4, began full FAA operations in October 1994.[177] An Airport Surface Detection Equipment (ASDE) radar unit sits atop the tower. At the time of its completion, the JFK tower, at 320 feet (98 m), was the world's tallest control tower.[177] It was subsequently displaced from that position by towers at other airports in both the United States and overseas, including those at Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport, currently the tallest tower at any U.S. airport, at 398 feet (121 m) and at KLIA2 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, currently the world's tallest control tower at 438 feet (134 m).[178][unreliable source?]

A VOR-DME station, identified as JFK, is located on the airport property between runways 4R/22L and 4L/22R.[2]

Physical plant[edit]

JFK is supplied with electricity by the Kennedy International Airport Power Plant, owned and operated by Calpine Corporation.[179] The natural gas-fired electric cogeneration facility uses two General Electric LM6000 gas turbine engines to supply a total of 110 megawatts, which is purchased by the Port Authority for airport operations. Excess energy is also sold to the New York Independent System Operator. The 45,000 sq ft (4,200 m2) facility was authorized in 1990,[180] designed by RMJM,[181] and first entered commercial service in February 1995.[182]

Heating and cooling for all of JFK's passenger terminals is provided by a co-located Central Heating and Refrigeration Plant (CHRP) in conjunction with a Thermal Distribution System (TDS) that entered service in August 1994. Waste heat from the power plant powers two heat recovery steam generators and a 25-megawatt steam turbine, which in turn run chillers to generate 28,000 tons of refrigeration, or heat exchangers to create 225 million Btu/hour.[182]

Aviation ground service[edit]

Aircraft service facilities include seven aircraft hangars, an engine overhaul building, a 32-million-US-gallon (120,000 m3) aircraft fuel storage facility, and a truck garage. Fixed-base operation service for general aviation flights is provided by Modern Aviation,[183] which possesses the airport's exclusive helipad.

Other facilities[edit]

The airport hosts an extensive array of administrative, government, and air cargo support buildings. In 2002, the New York metropolitan area accounted for 18 percent of import (and over 24 percent of all) air cargo volume in the nation. At that time, JFK itself was reported to have 4.5 million ft2 (418,064 m2) of warehouse space with another 434,000 sq ft (40,300 m2) under construction.[184]

| Building # | Status | Use | Current Tenant(s) | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Active | Cargo | FedEx Express | |

| 9 | Active | Cargo | Korean Air Cargo | Opened in 2001 on a 188,000 sq ft (17,500 m2) site capable of handling three 747 aircraft. The facility was the first at JFK to utilize a computerized automated storage and retrieval system for cargo handling.[185][186] |

| 14 | Active | Admin. | Port Authority | |

| JFK Medport | ||||

| 15 | Active | Ground Service | Snowlift | |

| 17 | Inactive | Hangar | Former Tower Air hangar and office.[187] Later housed artifacts from September 11 attacks, which were distributed to the 9/11 Museum and other memorials.[188] | |

| 23 | Active | Cargo | Lufthansa Cargo[189] | Previously known as 'Tract 8/9A'. Development of the 434,000 sq ft (40,300 m2) site began in August 2001. Currently capable of handling four 747 aircraft. Previous tenants included Alliance Airlines and Cargo Service Center.[184] |

| Qantas Freight[190] | ||||

| Swissport USA[191] | ||||

| CAL Cargo Air Lines[192] | ||||

| 66 | Active | Cargo | Nippon Cargo Airlines[193] | |

| 77 | Active | Mixed | U.S. Customs and Border Protection[194] | |

| Alliance Ground International[194] | ||||

| 81 | Active | Hangar | JetBlue | 140,000 sq ft (13,000 m2) maintenance facility with 70,000 sq ft (6,500 m2) of hangar space. It broke ground in 2003 and opened in 2005 for $45 million.[195][196] |

| 81A | ||||

| 81B | ||||

| 86 | Active | Cargo | MSN Air Service[194] | |

| 89 | Active | Cargo | DHL Global Forwarding | |

| 139 | Active | Ground Service | LSG Sky Chefs | |

| 141 | Active | Mixed | Aviation High School1 | Originally housed the Port Authority.[197]2 Other tenants included Servisair, the Port Authority Police Department,[198] and North American Airlines. |

| ABM Parking | ||||

| 145 | Active | Ground Service | Sheltair[200] | Previously operated by PANYNJ. It became the first privately operated FBO in JFK's history when it was transferred from PANYNJ on May 21, 2012.[201] |

| 151 | Active | Cargo | Worldwide Freight Services[194] | |

| Swissport | ||||

| 178 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Former Tower Air headquarters[202] |

| 208 | Active | Ground Service | Aerosnow | Former 400,000 sq ft (37,000 m2) Pan Am facility[184] |

| 213 | Inactive | Passenger Terminal | Former Tower Air terminal. | |

| 254 | Active | Public Safety | PAPD | |

| 255 | Active | Public Safety | PAPD | ARFF training facility equipped with two propane-fueled, computer-controlled aircraft fire simulators.[203] |

| 269 | Active | Public Safety | PAPD |

Three chapels, including Our Lady of the Skies Chapel, provide for the religious needs of airline passengers.[204]

In January 2017, the Ark at JFK Airport, a luxury terminal for pets, opened for $65 million. Ark was built ostensibly so that people who were transporting pets and other animals would be able to provide luxurious accommodations for these animals. At the time, it was supposed to be the only such facility in the U.S.[205] In January 2018, Ark's owner sued the Port Authority for violating a clause that would have given Ark the exclusive rights to inspect all animals who arrive at JFK from other countries. In the lawsuit, the owner stated that Ark had incurred significant operational losses because many animals were instead being transported to a United States Department of Agriculture facility in Newburgh.[206]

Airport hotels[edit]

Several hotels are adjacent to JFK Airport, including the Courtyard by Marriott and the Crowne Plaza. The former Ramada Plaza JFK Hotel is Building 144,[207][208] and it was formerly the only on-site hotel at JFK Airport.[209] It was previously a part of Forte Hotels and previously the Travelodge New York JFK.[210] Due to its role in housing friends and relatives of aircraft crash victims in the 1990s and 2000s, the hotel became known as the "Heartbreak Hotel".[211][212] In 2009 the PANYNJ stated in its preliminary 2010 budget that it was closing the hotel due to "declining aviation activity and a need for substantial renovation" and that it expected to save $1 million per month.[213] The hotel closed on December 1, 2009. Almost 200 employees lost their jobs.[214]

On July 27, 2015, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced in a press conference that the TWA Flight Center building would be used by the TWA Hotel, a 505-room hotel with 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2) of conference, event, or meeting space. The new hotel is estimated to have cost $265 million. The hotel has a 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) observation deck with an infinity pool.[215] Groundbreaking for the hotel occurred on December 15, 2016, and it opened on May 15, 2019.[216]

Airlines and destinations[edit]

Passenger[edit]

Cargo[edit]

When ranked by the value of shipments passing through it, JFK is the number three freight gateway in the United States (after the Port of Los Angeles and the Port of New York and New Jersey), and the number one international air freight gateway in the United States.[5] Almost 21% of all U.S. international air freight by value and 9.6% by tonnage moved through JFK in 2008.[314]

The JFK air cargo complex is a Foreign Trade Zone, which legally lies outside the customs area of the United States.[315] JFK is a major hub for air cargo between the United States and Europe. London, Brussels and Frankfurt are JFK's three top trade routes.[316] The European airports are mostly a link in a global supply chain, however. The top destination markets for cargo flying out of JFK in 2003 were Tokyo, Seoul and London. Similarly, the top origin markets for imports at JFK were Seoul, Hong Kong, Taipei and London.[316]

20 cargo airlines operate out of JFK,[316] among them: Air ACT, Air China Cargo, ABX Air, Asiana Cargo, Atlas Air, CAL Cargo Air Lines, Cargolux, Cathay Cargo, China Airlines, EVA Air Cargo, Emirates SkyCargo, Nippon Cargo Airlines, FedEx Express, DHL Aviation, Kalitta Air, Korean Air Cargo, Lufthansa Cargo, UPS Airlines, Southern Air and, formerly, World Airways. Top 5 carriers together transported 33.1% of all revenue freight in 2005: American Airlines (10.9% of the total), FedEx Express (8.8%), Lufthansa Cargo (5.2%), Korean Air Cargo (4.9%), China Airlines (3.8%).[317]

There are also some on-demand cargo charter services to JFK, which is Silk Way West Airlines one of the most active cargo charter airline to this destination.

Most cargo and maintenance facilities at JFK are located north and west of the main terminal area. DHL, FedEx Express, Japan Airlines, Lufthansa, Nippon Cargo Airlines and United Airlines have cargo facilities at JFK.[316][318] In 2000, Korean Air Cargo opened a new $102 million cargo terminal at JFK with total floor area of 81,124 square feet (7,536.7 m2) and capability of handling 200,000 tons annually. In 2007, American Airlines opened a new priority parcel service facility at their Terminal 8, featuring 30-minute drop-offs and pick-ups for priority parcel shipments within the US.[319]

Statistics[edit]

Passenger numbers[edit]

| Year | Passengers |

|---|---|

| 2009 | 45,877,942

|

| 2010 | 46,515,060

|

| 2011 | 47,643,477

|

| 2012 | 49,273,824

|

| 2013 | 50,451,822

|

| 2014 | 53,220,426

|

| 2015 | 56,884,730

|

| 2016 | 59,103,472

|

| 2017 | 59,488,982

|

| 2018 | 61,636,235

|

| 2019 | 62,571,463

|

| 2020 | 16,630,642

|

| 2021 | 30,788,322

|

| 2022 | 55,287,711

|

| 2023 | 62,440,306

|

Top destinations[edit]

| Rank | Airport | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Los Angeles, California | 1,395,000 | American, Delta, JetBlue |

| 2 | San Francisco, California | 971,000 | Alaska, American, Delta, JetBlue |

| 3 | Miami, Florida | 875,000 | American, Delta, JetBlue |

| 4 | Orlando, Florida | 722,000 | Delta, JetBlue |

| 5 | Fort Lauderdale, Florida | 601,000 | Delta, JetBlue |

| 6 | Atlanta, Georgia | 523,000 | Delta, JetBlue |

| 7 | San Juan, Puerto Rico | 517,000 | Delta, JetBlue |

| 8 | Seattle/Tacoma, Washington | 481,000 | Alaska, Delta, JetBlue |

| 9 | Las Vegas, Nevada | 463,000 | Delta, JetBlue |

| 10 | Boston, Massachusetts | 438,000 | American, Delta, JetBlue |

| Rank | Change | Airport | Passengers | Change | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | London–Heathrow, United Kingdom | 2,316,480 | American, British Airways, Delta, JetBlue, Virgin Atlantic | ||

| 2 | Paris–Charles de Gaulle, France | 1,446,607 | Air France, American, Delta, JetBlue, Norse Atlantic | ||

| 3 | Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic | 893,376 | Delta, JetBlue | ||

| 4 | Santo Domingo–Las Américas | 885,562 | Delta, JetBlue | ||

| 5 | Madrid, Spain | 727,206 | Air Europa, American, Delta, Iberia | ||

| 6 | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 720,926 | Delta, JetBlue, KLM | ||

| 7 | Cancún, Mexico | 682,079 | American, Delta, JetBlue | ||

| 8 | Milan–Malpensa, Italy | 659,283 | American, Delta, Emirates, ITA, Neos | ||

| 9 | Tel Aviv, Israel | 648,989 | American, Delta, El AL | ||

| 10 | Rome–Fiumicino, Italy | 621,483 | American, Delta, ITA, Norse Atlantic | ||

| 11 | Frankfurt, Germany | 591,502 | Condor, Delta, Lufthansa, Singapore | ||

| 12 | Mexico City, Mexico | 586,955 | Aeroméxico, American, Delta, VivaAerobus | ||

| 13 | Dubai–International, United Arab Emirates | 574,125 | Emirates | ||

| 14 | Istanbul, Turkey | 562,854 | Turkish | ||

| 15 | Punta Cana, Dominican Republic | 533,624 | American, Delta, JetBlue | ||

| 16 | Doha, Qatar | 517,795 | Qatar | ||

| 17 | Dublin, Ireland | 507,600 | Aer Lingus, Delta | ||

| 18 | Montego Bay, Jamaica | 483,321 | Delta, JetBlue | ||

| 19 | São Paulo–Guarulhos, Brazil | 435,977 | American, Delta, LATAM Brasil | ||

| 20 | Barcelona, Spain | 432,531 | American, Delta, Level |

[edit]

| Rank | Airline | Passengers | Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Delta Air Lines | 18,379,843 | 29.6% |

| 2 | JetBlue | 16,345,561 | 26.3% |

| 3 | American Airlines | 7,960,709 | 12.8% |

| 4 | Alaska Airlines | 1,286,076 | 2.1% |

| 5 | British Airways | 1,267,705 | 2.0% |

| 6 | Air France | 1,042,816 | 1.7% |

| 7 | Virgin Atlantic | 1,018,928 | 1.6% |

| 8 | Avianca | 917,955 | 1.5% |

| 9 | Emirates | 888,446 | 1.4% |

| 10 | Aer Lingus | 634,305 | 1.0% |

Other[edit]

Information services[edit]

In the immediate vicinity of the airport, parking and other information can be obtained by tuning to a highway advisory radio station at 1630 AM.[345] A second station at 1700 AM provides information on traffic concerns for drivers leaving the airport.

Kennedy Airport, along with the other Port Authority airports (LaGuardia and Newark), uses a uniform style of signage throughout the airport properties. Yellow signs direct passengers to airline gates, ticketing and other flight services; green signs direct passengers to ground transportation services and black signs lead to restrooms, telephones and other passenger amenities. In addition, the Port Authority operates "Welcome Centers" and taxi dispatch booths in each airline terminal, where staff provide customers with information on taxis, limousines, other ground transportation and hotels.

Former New York City traffic reporter Bernie Wagenblast provides the voice for the airport's radio stations and the messages heard on board AirTrain JFK and in its stations.[346]

Notable staff[edit]

Stephen Abraham, colloquially known as Kennedy Steve, was an air traffic controller at JFK between 1994 and 2017.[347] Abraham was known for his distinct "informal" tone and controlling-style while handling ground traffic at the airport. Many of his interactions with pilots were recorded and featured on various social media platforms, including various YouTube channels. In 2017, Abraham was awarded the Dale Wright Award by the National Air Traffic Controllers Association (NATCA) for distinguished professionalism and exceptional career service to NATCA and the National Air Space System.[348][349] In 2019, he was hired as Airside Operations and Ramp Manager at JFK's Terminal 1.[350]

Accidents and incidents[edit]

See also[edit]

- List of memorials to John F. Kennedy

- Christopher O. Ward

- List of tallest air traffic control towers in the United States

Notes[edit]

- ^ Colloquially referred to as JFK Airport, Kennedy Airport, New York-JFK, or simply JFK

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Governor Pataki and Mayor Bloomberg Announce Closing of Multi-Billion Dollar Agreement to Extend Airport Leases" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. November 30, 2004. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

The Port Authority has operated Idlewild and LaGuardia for more than 55 years. The original 50-year lease [with the City of New York] was signed in 1947 and extended to 2015 under a 1965 agreement.

- ^ "General Information". The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. May 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ "JFK (KJFK): JOHN F KENNEDY INTL, NEW YORK, NY – UNITED STATES". Aeronautical Information Services. Federal Aviation Administration. February 27, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "Top 25 U.S. Freight Gateways, Ranked by Value of Shipments: 2008". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. United States Department of Transportation. 2009. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ a b FAA Airport Form 5010 for JFK PDF, effective December 30, 2021.

- ^ "Airlines". John F. Kennedy International Airport. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ "Directory: World Airlines". Flight International. April 3, 2007. p. 86.

- ^ "Service Providers – JFK Airport – Air Cargo – Port Authority of New York & New Jersey". Panynj.gov. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Radka, Ricky (December 23, 2021). "Airline Hub Guide: Which U.S. Cities Are Major Hubs and Why it Matters". airfarewatchdog.com. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ James, Nancy (October 3, 2023). "Best New York Airport – A Comparison of JFK, LaGuardia, and Newark". Airlines Policy. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ "Welcome to JFK Airport Guide". JFK Airport Guide. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ "JFK Airport: New York's Kennedy International Airport and Port Authority Flights". January 17, 2024. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ "N.Y. Airport Has Troubles". Reading Eagle. Reading, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. August 4, 1949. p. 31. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "Idlewild becomes Kennedy". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. December 6, 1963. p. 1. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ a b "N.Y. airport takes name of Kennedy". Toledo Blade. Toledo, Ohio. Associated Press. December 25, 1963. p. 2. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ "Idlewild's New Code is JFK". The New York Times. United Press International. January 1, 1964. p. 40.

The FAA code became JFK at the beginning of 1964; the Airline Guide used JFK and it seems the airlines did too; the airlines must print millions of new baggage tags carrying the initials JFK

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Trans World Airlines Flight Center (Now TWA Terminal A) at New York International Airport" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 9, 1994. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "Tentative Site of 1,200-Acre City Airport Is Selected by Mayor at Idlewild, Queens". The New York Times. October 6, 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "New Airport Site Acquired by City; Title to Land for Defense Field in Idlewild Area of Queens Is Conveyed". The New York Times. December 31, 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Groot, Marnix (February 28, 2019). "The History of JFK Airport - Grand Design". Airporthistory.org. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ a b Amon, Rhonda (May 13, 1998). "Major Airports Take Off". Newsday. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Council Overrides Airport Name Veto; Insists by Vote of 19 to 6 on Designating Idlewild Field to Honor Gen. Anderson". The New York Times. June 25, 1943. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Addition to Idlewild Airport Approved; $5,054,000 Is Voted to Make Site Ready". The New York Times. June 21, 1944. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Trans World Airlines Flight Center (now TWA Terminal A) at New York International Airport (PDF). Landmarks Preservation Commission (Report). July 14, 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 18, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Cullman, Howard S. (June 8, 1947). "Tomorrow's Airport – A World Fair; Howard Cullman sets out his plan for a great terminal, a great spectacle (and no red ink)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Idlewild Airport Officially Opened; Six Foreign Flag Carriers and Two Others Will Not Begin Operations for a Week". The New York Times. July 1, 1948. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Aviation: Hub of the World". Time Magazine. July 12, 1948. Archived from the original on September 25, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "IDLEWILD BEING EXPANDED; Will Be Extended From 79,280 Square Feet to 245,501". The New York Times. October 20, 1949. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "New Control Tower for Idlewild". The New York Times. February 20, 1952. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Idlewild Capacity Will Be Enlarged". The New York Times. March 19, 1952. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Expanded Facilities Planned at Idlewild". The New York Times. January 28, 1953. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Aerial Pic Looking WSW". New York State Archives. December 31, 1949. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ "The lost runway of JFK?". NYCaviation.com. July 21, 2007. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ "Newark Airport Stays Closed Pending Results of Inquiries; Safety Group Headed by Rickenbacker Set Up by U. S. and Airlines -- Take-Offs Over Water Pledged at La Guardia, Idlewild; Airport Closed Pending Inquiry", The New York Times, February 13, 1952. Accessed March 27, 2023. "With La Guardia and New York International (Idlewild) Airports in Queens takin over the bulk of Newark's former flights for the time being, it was also agreed to use their runways so as to enable planes to take off over water or over least-settled areas as much as possible.... The agreements were announces at the Commodore Hotel after a closed-door conference of five and a half hours, called by the Port of New York Authority as a result of three airplane crashes in Elizabeth, N.J., which have taken 116 lives in the last two months and which caused closing of Newark Airport early Monday morning."

- ^ Sharkey, John B. "Newark Liberty International Airport, A Postal History", New Jersey Postal History Society, May 2021. Accessed March 27, 2023. "The airport reopened on November 15, 1952, but only after a new runway was built. The runway directed at the city of Elizabeth was closed forever."

- ^ Hudson, Edward (December 6, 1955). "New Structures Rise at Idlewild; Makeshift Buildings Giving Way as Airport Undergoes a Construction Boom". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Gordon, Alastair (2014). Naked Airport: A Cultural History of the World's Most Revolutionary Structure. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-1-4668-6911-0.

- ^ Pearman, Hugh (2004). Airports: A Century of Architecture. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85669-356-1. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ^ Airports and Air Carriers August 1948.

- ^ "Port Authority Prepares John F. Kennedy International Airport for Next Generation of Quieter, More-Efficient Aircraft" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. April 1, 2004. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ Friedman, Paul J. c Friedlandersy (December 8, 1957). "Idlewild Transformed; New Terminal Buildings Give Old Airport Class, Comfort and Style Arrival Center". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b "John F. Kennedy International Airport, United and Delta Airlines Building". CardCow.com.

- ^ "BIG NEW TERMINAL OPEN AT IDLEWILD; United Air Lines Structure Costing $14,500,000 Part of Extensive Project". The New York Times. October 14, 1959. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Hudson, Edward (October 30, 1959). "Eastern Airlines Opens Terminal; Lone Passenger Puts New $20,000,000 Building Into Operation at Idlewild". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Bigger Than Grand Central". Time Magazine. November 9, 1959. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Hudson, Edward (February 10, 1960). "Idlewild to Open Newest Terminal; American Airlines' Offices, With Unusual Facade, to Go Into Use Today". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Knox, Sanka (December 26, 1959). "Airport Window is a Block Long; Stained Glass Art Work is Installed at American's Terminal at Idlewild". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Ford, Ruth (July 23, 2006). "Demolishing a Celebrated Wall of Glass". The New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ^ Knox, Sanka (June 3, 1960). "Idlewild Skyline Gets an Addition; New Pan Am Terminal Looks Like Parasol to Motorists Approaching Airport". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b "Umbrella for Airplanes". Time Magazine. June 13, 1960. Archived from the original on September 25, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Klimek, Chris (August 18, 2008). "Saarinen exhibit at National Building Museum". Washington Examiner. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Risen, Clay (November 7, 2004). "Saarinen rising: A much-maligned modernist finally gets his due". The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "JetBlue – Terminal 5 History". JetBlue Airways. October 22, 2008. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ "Idlewild to Open Terminal Nov. 18; Three Airlines Will Share $10,000,000 Structure Steps Are Saved Waffle Pattern Ceiling". The New York Times. November 9, 1962. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Fowle, Farnsworth (November 29, 1969). "Superjet Terminal Will Open". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "I.M. Pei's JFK". The Architect's Newspaper. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ "Port Authority, United Airlines Launch Major Redevelopment of Terminals 5 and 6 at JFK – Project Pushes Total Cost of Kennedy Airport's Record Redevelopment to $10 Billion Mark" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. October 30, 2000. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006. Retrieved May 1, 2009.

- ^ Benjamin, Philip (December 25, 1963). "Idlewild Is Rededicated as John F. Kennedy Airport". The New York Times. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ^ Morgan, Richard (November 21, 2013). "For JFK, the King of Camelot, an Airport in Queens". The Wall Street Journal. New York. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ FAA Airport Form 5010 for IDL PDF. Federal Aviation Administration. Effective November 15, 2012.

- ^ Witkin, Richard (November 23, 1977). "Concordes From London and Paris Land at Kennedy As 16-Month Trial Passenger Service Is Initiated". The New York Times. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ Kilgannon, Corey (October 25, 2003). "Covering Their Ears One Last Time for Concorde". The New York Times. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ Chan, Sewell (January 12, 2005). "Train to J.F.K. Scores With Fliers, but Not With Airport Workers". The New York Times. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ "Project Profile; USA; New York Airtrain" (PDF). UCL Bartlett School of Planning. September 6, 2011. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Dentch, Courtney (April 18, 2002). "AirTrain system shoots for October start date". Times Ledger. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ Stellin, Susan (December 14, 2003). "TRAVEL ADVISORY; A Train to the Plane, At Long Last". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ "To & From JFK". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "JFK Airport AirTrain". Jfk-airport.net. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (May 22, 1998). "Inside Art". The New York Times. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ "New Terminal 4 Opens at JFK Airport – A Key Element in Port Authorit's $10.3 Billion JFK Redevelopment Program" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. May 24, 2001. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ "Port Authority Takes Important Step in Overhaul of Domestic and International Gateways at Kennedy Airport" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. May 22, 2008. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ "Emirates A380 Lands at JFK New York". Airwise News. Reuters. August 1, 2008. Archived from the original on August 6, 2008. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Emirates Airline A380 Emirates to Stop Flying A380s to NY". eTurboNews. March 18, 2009. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ Gonzalez, Manny (January 17, 2012). "PHOTOS: Singapore Airlines Upgrades New York JFK Service to Airbus A380 Super Jumbo". NYCAviation.com. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- ^ Salvioli, L. (June 23, 2015). "Dentro l'Airbus A380, il gigante dei cieli che vola tra Milano e New York: tra lussi e doccia a bordo". Il Sole 24 Ore (in Italian). Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ^ "Qatar's Airbus A350 takes off for US". The Himalayan Times. Himalayan News Service. December 9, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ Pileggi, Nicholas (1986). Wiseguy: Life in a Mafia Family. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-44734-3.

- ^ "$420,000 Is Missing From Locked Room at Kennedy Airport" (PDF). The New York Times. New York. April 12, 1967. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ "N.Y. theft largest in history". Nashua Telegraph. (New Hampshire). Associated Press. December 12, 1978. p. 2.

- ^ Maitland, Leslie (December 14, 1978). "Airport Cash Loot Was $5 Million; Bandits' Van Is Found in Canarsie". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ a b Janos, Adam. "Lufthansa Heist Murders: How Paranoia Led to the Deaths of 6 Mobsters". A&E. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2021.