COVID-19 pandemic: Difference between revisions

SquidHomme (talk | contribs) →United States: fix |

Ozzie10aaaa (talk | contribs) →South America: though it is an excerpt it still needs to be referenced |

||

| Line 498: | Line 498: | ||

{{Main|COVID-19 pandemic in South America}} |

{{Main|COVID-19 pandemic in South America}} |

||

[[File:Capacitação dos profissionais da Saúde que atuarão nos terminais de ônibus - 49667698972.jpg|thumb|Workers being trained to disinfect buses in [[Olinda]], Pernambuco, Brazil, 16 March 2020]] |

[[File:Capacitação dos profissionais da Saúde que atuarão nos terminais de ônibus - 49667698972.jpg|thumb|Workers being trained to disinfect buses in [[Olinda]], Pernambuco, Brazil, 16 March 2020]] |

||

<div class="excerpt>{{#lsth:COVID-19 pandemic in South America}}</div> |

<div class="excerpt>{{#lsth:COVID-19 pandemic in South America}}</div>{{citation needed}} |

||

===Africa=== |

===Africa=== |

||

Revision as of 13:39, 16 May 2020

| COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

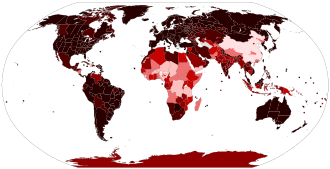

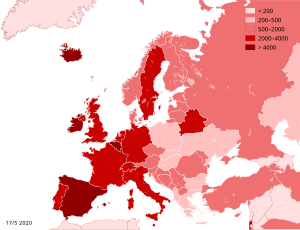

Map of confirmed cases per capita as of 16 May 2020[update]

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

(clockwise from top)

| |||||||||

| Disease | Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) | ||||||||

| Virus strain | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2)[a] | ||||||||

| Source | Probably bats, possibly via pangolins or lepidopteraes[2][3][4] | ||||||||

| Location | Worldwide | ||||||||

| First outbreak | China[5] | ||||||||

| Index case | Wuhan, Hubei, China 30°37′11″N 114°15′28″E / 30.61972°N 114.25778°E | ||||||||

| Date | December 2019[5] – present (4 years, 11 months and 1 week) | ||||||||

| Confirmed cases | 676,609,955[6][b] | ||||||||

| Active cases | [6] | ||||||||

| Recovered | [6] | ||||||||

Deaths | 6,881,955[6] | ||||||||

Territories | [6] | ||||||||

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2).[1] The outbreak was first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019.[5][7] The World Health Organization declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 30 January, and a pandemic on 11 March.[8][9] As of 10 March 2023, more than 676 million cases of COVID-19 have been reported in more than countries and territories, resulting in more than 6.88 million deaths. More than people have recovered.[6]

Common symptoms include fever, cough, fatigue, shortness of breath, and loss of smell.[10][11][12] Complications may include pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome.[13] The time from exposure to onset of symptoms is typically around five days, but may range from two to fourteen days.[14][15] There is no known vaccine or specific antiviral treatment.[10] Primary treatment is symptomatic and supportive therapy.[16]

Recommended preventive measures include hand washing, covering one's mouth when coughing, maintaining distance from other people, wearing a face mask in public settings, and monitoring and self-isolation for people who suspect they are infected.[10][17] Authorities worldwide have responded by implementing travel restrictions, lockdowns, workplace hazard controls, and facility closures. Many places have also worked to increase testing capacity and trace contacts of infected persons.

The pandemic has caused severe global economic disruption,[18] including the largest global recession since the Great Depression.[19] It has led to the postponement or cancellation of sporting, religious, political and cultural events,[20] widespread supply shortages exacerbated by panic buying,[21][22] and decreased emissions of pollutants and greenhouse gases.[23][24] Schools, universities, and colleges have closed either on a nationwide or local basis in 63 countries, affecting approximately 47 per cent of the world's student population.[25] Misinformation about the virus has spread online,[26] and there have been incidents of xenophobia and discrimination against Chinese people and against those perceived as being Chinese, or as being from areas with high infection rates.[27][28][29]

Epidemiology

| Location | Cases | Deaths | |

|---|---|---|---|

| World[c] | 776,753,553 | 7,073,453 | |

| European Union[d] | 186,262,640 | 1,265,282 | |

| United States | 103,436,829 | 1,206,141 | |

| China[e] | 99,381,078 | 122,367 | |

| India | 45,044,196 | 533,653 | |

| France | 39,024,965 | 168,091 | |

| Germany | 38,437,756 | 174,979 | |

| Brazil | 37,511,921 | 702,116 | |

| South Korea | 34,571,873 | 35,934 | |

| Japan | 33,803,572 | 74,694 | |

| Italy | 26,826,486 | 197,542 | |

| United Kingdom | 25,010,212 | 232,112 | |

| Russia | 24,572,846 | 403,557 | |

| Turkey | 17,004,729 | 101,419 | |

| Spain | 13,980,340 | 121,852 | |

| Australia | 11,861,161 | 25,236 | |

| Vietnam | 11,624,000 | 43,206 | |

| Argentina | 10,106,404 | 130,697 | |

| Taiwan | 9,970,937 | 17,672 | |

| Netherlands | 8,644,647 | 22,986 | |

| Iran | 7,627,863 | 146,837 | |

| Mexico | 7,622,283 | 334,783 | |

| Indonesia | 6,829,704 | 162,059 | |

| Poland | 6,758,426 | 120,897 | |

| Colombia | 6,394,361 | 142,727 | |

| Austria | 6,082,860 | 22,534 | |

| Greece | 5,727,906 | 39,639 | |

| Portugal | 5,669,567 | 29,027 | |

| Ukraine | 5,541,305 | 109,923 | |

| Chile | 5,403,559 | 64,482 | |

| Malaysia | 5,318,418 | 37,351 | |

| Belgium | 4,889,242 | 34,339 | |

| Israel | 4,841,558 | 12,707 | |

| Canada | 4,819,055 | 55,282 | |

| Czech Republic | 4,811,887 | 43,687 | |

| Thailand | 4,803,632 | 34,734 | |

| Peru | 4,526,977 | 220,975 | |

| Switzerland | 4,468,044 | 14,170 | |

| Philippines | 4,173,631 | 66,864 | |

| South Africa | 4,072,813 | 102,595 | |

| Romania | 3,566,594 | 68,899 | |

| Denmark | 3,442,484 | 9,919 | |

| Singapore | 3,006,155 | 2,024 | |

| Hong Kong | 2,876,106 | 13,466 | |

| Sweden | 2,765,204 | 28,006 | |

| New Zealand | 2,652,096 | 4,442 | |

| Serbia | 2,583,470 | 18,057 | |

| Iraq | 2,465,545 | 25,375 | |

| Hungary | 2,236,219 | 49,092 | |

| Bangladesh | 2,051,463 | 29,499 | |

| Slovakia | 1,883,895 | 21,249 | |

| Georgia | 1,864,383 | 17,151 | |

| Republic of Ireland | 1,750,138 | 9,900 | |

| Jordan | 1,746,997 | 14,122 | |

| Pakistan | 1,580,631 | 30,656 | |

| Norway | 1,524,523 | 5,732 | |

| Kazakhstan | 1,504,370 | 19,072 | |

| Finland | 1,499,712 | 11,466 | |

| Lithuania | 1,400,088 | 9,848 | |

| Slovenia | 1,359,884 | 9,914 | |

| Croatia | 1,348,642 | 18,775 | |

| Bulgaria | 1,337,733 | 38,751 | |

| Morocco | 1,279,115 | 16,305 | |

| Puerto Rico | 1,252,713 | 5,938 | |

| Guatemala | 1,250,392 | 20,203 | |

| Lebanon | 1,239,904 | 10,947 | |

| Costa Rica | 1,235,724 | 9,374 | |

| Bolivia | 1,212,149 | 22,387 | |

| Tunisia | 1,153,361 | 29,423 | |

| Cuba | 1,113,662 | 8,530 | |

| Ecuador | 1,078,795 | 36,055 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 1,067,030 | 2,349 | |

| Panama | 1,044,987 | 8,756 | |

| Uruguay | 1,041,682 | 7,686 | |

| Mongolia | 1,011,489 | 2,136 | |

| Nepal | 1,003,450 | 12,031 | |

| Belarus | 994,038 | 7,118 | |

| Latvia | 977,765 | 7,475 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 841,469 | 9,646 | |

| Azerbaijan | 836,474 | 10,353 | |

| Paraguay | 735,759 | 19,880 | |

| Cyprus | 708,580 | 1,492 | |

| Palestine | 703,228 | 5,708 | |

| Bahrain | 696,614 | 1,536 | |

| Sri Lanka | 672,809 | 16,907 | |

| Kuwait | 667,290 | 2,570 | |

| Dominican Republic | 661,103 | 4,384 | |

| Moldova | 650,609 | 12,281 | |

| Myanmar | 643,215 | 19,494 | |

| Estonia | 612,467 | 2,998 | |

| Venezuela | 552,695 | 5,856 | |

| Egypt | 516,023 | 24,830 | |

| Qatar | 514,524 | 690 | |

| Libya | 507,269 | 6,437 | |

| Ethiopia | 501,239 | 7,574 | |

| Réunion | 494,595 | 921 | |

| Honduras | 472,909 | 11,114 | |

| Armenia | 453,016 | 8,778 | |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 403,960 | 16,402 | |

| Oman | 399,449 | 4,628 | |

| Luxembourg | 396,017 | 1,000 | |

| North Macedonia | 352,043 | 9,990 | |

| Zambia | 349,892 | 4,078 | |

| Brunei | 349,279 | 181 | |

| Kenya | 344,109 | 5,689 | |

| Albania | 337,195 | 3,608 | |

| Botswana | 330,696 | 2,801 | |

| Mauritius | 329,121 | 1,074 | |

| Kosovo | 274,279 | 3,212 | |

| Algeria | 272,173 | 6,881 | |

| Nigeria | 267,189 | 3,155 | |

| Zimbabwe | 266,396 | 5,740 | |

| Montenegro | 251,280 | 2,654 | |

| Afghanistan | 235,214 | 7,998 | |

| Mozambique | 233,845 | 2,252 | |

| Martinique | 230,354 | 1,104 | |

| Laos | 219,060 | 671 | |

| Iceland | 210,675 | 186 | |

| Guadeloupe | 203,235 | 1,021 | |

| El Salvador | 201,960 | 4,230 | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 191,496 | 4,390 | |

| Maldives | 186,694 | 316 | |

| Uzbekistan | 175,081 | 1,016 | |

| Namibia | 172,556 | 4,110 | |

| Ghana | 172,210 | 1,462 | |

| Uganda | 172,159 | 3,632 | |

| Jamaica | 157,326 | 3,618 | |

| Cambodia | 139,325 | 3,056 | |

| Rwanda | 133,266 | 1,468 | |

| Cameroon | 125,279 | 1,974 | |

| Malta | 123,136 | 925 | |

| Barbados | 108,835 | 593 | |

| Angola | 107,482 | 1,937 | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 100,976 | 1,474 | |

| French Guiana | 98,041 | 413 | |

| Senegal | 89,312 | 1,972 | |

| Malawi | 89,168 | 2,686 | |

| Kyrgyzstan | 88,953 | 1,024 | |

| Ivory Coast | 88,448 | 835 | |

| Suriname | 82,503 | 1,406 | |

| New Caledonia | 80,203 | 314 | |

| French Polynesia | 79,451 | 650 | |

| Eswatini | 75,356 | 1,427 | |

| Guyana | 74,491 | 1,302 | |

| Belize | 71,430 | 688 | |

| Fiji | 69,047 | 885 | |

| Madagascar | 68,575 | 1,428 | |

| Jersey | 66,391 | 161 | |

| Cabo Verde | 64,474 | 417 | |

| Sudan | 63,993 | 5,046 | |

| Mauritania | 63,876 | 997 | |

| Bhutan | 62,697 | 21 | |

| Syria | 57,423 | 3,163 | |

| Burundi | 54,569 | 15 | |

| Guam | 52,287 | 419 | |

| Seychelles | 51,892 | 172 | |

| Gabon | 49,056 | 307 | |

| Andorra | 48,015 | 159 | |

| Papua New Guinea | 46,864 | 670 | |

| Curaçao | 45,883 | 305 | |

| Aruba | 44,224 | 292 | |

| Tanzania | 43,263 | 846 | |

| Mayotte | 42,027 | 187 | |

| Togo | 39,533 | 290 | |

| Bahamas | 39,127 | 849 | |

| Guinea | 38,582 | 468 | |

| Isle of Man | 38,008 | 116 | |

| Lesotho | 36,138 | 709 | |

| Guernsey | 35,326 | 67 | |

| Faroe Islands | 34,658 | 28 | |

| Haiti | 34,556 | 860 | |

| Mali | 33,171 | 743 | |

| Federated States of Micronesia | 31,765 | 65 | |

| Cayman Islands | 31,472 | 37 | |

| Saint Lucia | 30,288 | 410 | |

| Benin | 28,036 | 163 | |

| Somalia | 27,334 | 1,361 | |

| Solomon Islands | 25,954 | 199 | |

| United States Virgin Islands | 25,389 | 132 | |

| San Marino | 25,292 | 126 | |

| Republic of the Congo | 25,234 | 389 | |

| Timor-Leste | 23,460 | 138 | |

| Burkina Faso | 22,146 | 400 | |

| Liechtenstein | 21,605 | 89 | |

| Gibraltar | 20,550 | 113 | |

| Grenada | 19,693 | 238 | |

| Bermuda | 18,860 | 165 | |

| South Sudan | 18,847 | 147 | |

| Tajikistan | 17,786 | 125 | |

| Monaco | 17,181 | 67 | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 17,130 | 183 | |

| Samoa | 17,057 | 31 | |

| Tonga | 16,992 | 13 | |

| Marshall Islands | 16,297 | 17 | |

| Nicaragua | 16,194 | 245 | |

| Dominica | 16,047 | 74 | |

| Djibouti | 15,690 | 189 | |

| Central African Republic | 15,443 | 113 | |

| Northern Mariana Islands | 14,985 | 41 | |

| Gambia | 12,627 | 372 | |

| Collectivity of Saint Martin | 12,324 | 46 | |

| Vanuatu | 12,019 | 14 | |

| Greenland | 11,971 | 21 | |

| Yemen | 11,945 | 2,159 | |

| Caribbean Netherlands | 11,922 | 41 | |

| Sint Maarten | 11,051 | 92 | |

| Eritrea | 10,189 | 103 | |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 9,674 | 124 | |

| Guinea-Bissau | 9,614 | 177 | |

| Niger | 9,528 | 315 | |

| Comoros | 9,109 | 160 | |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 9,106 | 146 | |

| American Samoa | 8,359 | 34 | |

| Liberia | 8,090 | 294 | |

| Sierra Leone | 7,985 | 126 | |

| Chad | 7,702 | 194 | |

| British Virgin Islands | 7,628 | 64 | |

| Cook Islands | 7,375 | 2 | |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | 6,824 | 40 | |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 6,771 | 80 | |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 6,607 | 46 | |

| Palau | 6,372 | 10 | |

| Saint Barthélemy | 5,507 | 5 | |

| Nauru | 5,393 | 1 | |

| Kiribati | 5,085 | 24 | |

| Anguilla | 3,904 | 12 | |

| Wallis and Futuna | 3,760 | 9 | |

| Macau | 3,514 | 121 | |

| Saint Pierre and Miquelon | 3,426 | 2 | |

| Tuvalu | 2,943 | 1 | |

| Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha | 2,166 | 0 | |

| Falkland Islands | 1,923 | 0 | |

| Montserrat | 1,403 | 8 | |

| Niue | 1,092 | 0 | |

| Tokelau | 80 | 0 | |

| Vatican City | 26 | 0 | |

| Pitcairn Islands | 4 | 0 | |

| Turkmenistan | 0 | 0 | |

| North Korea | 0 | 0 | |

| |||

Background

On 31 December 2019, health authorities in China reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) a cluster of viral pneumonia cases of unknown cause in Wuhan, Hubei Province,[31][32] and an investigation was launched in early January 2020.[33] On 30 January, the WHO declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC)—7,818 cases confirmed globally, affecting 19 countries in five WHO regions.[34][35]

Several of the early cases had visited Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market [36]and so the virus is thought to have a zoonotic origin.[37] The virus that caused the outbreak is known as SARS‑CoV‑2, a newly discovered virus closely related to bat coronaviruses,[38] pangolin coronaviruses,[39][40] and SARS-CoV.[41] The scientific consensus is that COVID-19 has a natural origin.[42][43] The probable bat-to-human infection may have been among people processing bat carcasses and guano in the production of traditional Chinese medicines.[44]

The earliest known person with symptoms was later discovered to have fallen ill on 1 December 2019, and that person did not have visible connections with the later wet market cluster.[45][46] Of the early cluster of cases reported that month, two-thirds were found to have a link with the market.[47][48][49] On 13 March 2020, an unverified report from the South China Morning Post suggested a case traced back to 17 November 2019 (a 55-year-old from Hubei) may have been the first person infected.[50][51]

The WHO recognized the spread of COVID-19 as a pandemic on 11 March 2020.[52] Italy, Iran, South Korea, and Japan reported surging cases. The total numbers outside China quickly passed China's.[53]

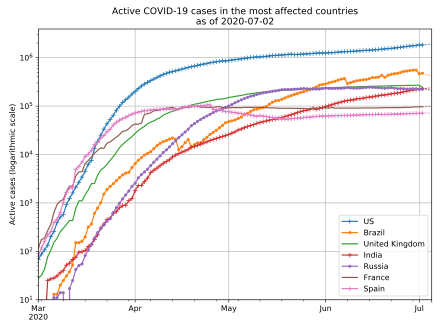

Cases

Cases refer to the number of people who have been tested for COVID-19, and whose test has been confirmed positive according to official protocols.[54] As of 24 May, countries that publicised their testing data have typically performed a number of tests equal to 2.6 per cent of their population, while no country tested samples equal to more than 17.3 per cent of its population.[55] Many countries, early on, had official policies to not test those with only mild symptoms.[56][57] An analysis of the early phase of the outbreak up to 23 January estimated 86 per cent of COVID-19 infections had not been detected, and that these undocumented infections were the source for 79 per cent of documented cases.[58] Several other studies, using a variety of methods, have estimated that numbers of infections in many countries are likely to be considerably greater than the reported cases.[59][60]

On 9 April 2020, preliminary results found that 15 per cent of people tested in Gangelt, the centre of a major infection cluster in Germany, tested positive for antibodies.[61] Screening for COVID-19 in pregnant women in New York City, and blood donors in the Netherlands, has also found rates of positive antibody tests that may indicate more infections than reported.[62][63] However, such antibody surveys can be unreliable due to a selection bias in who volunteers to take the tests, and due to false positives. Some results (such as the Gangelt study) have received substantial press coverage without first passing through peer review.[64]

Analysis by age in China indicates that a relatively low proportion of cases occur in individuals under 20.[65] It is not clear whether this is because young people are actually less likely to be infected, or less likely to develop serious symptoms and seek medical attention and be tested.[66] A retrospective cohort study in China found that children were as likely to be infected as adults.[67] Countries that test more, relative to the number of deaths, have a younger age distributions of cases, relative to the wider population.[68]

Initial estimates of the basic reproduction number (R0) for COVID-19 in January were between 1.4 and 2.5,[69] but a subsequent analysis has concluded that it may be about 5.7 (with a 95 per cent confidence interval of 3.8 to 8.9).[70] R0 can vary across populations, and is not to be confused with the effective reproduction number (commonly just called R), which takes into account effects such as social distancing and herd immunity. As of mid-May 2020, the effective R is close to or below 1.0 in many countries, meaning the spread of the disease in these areas is stable or decreasing.[71]

-

Total confirmed cases of COVID-19 per million people[72]

-

Epidemic curve of COVID-19 by date of report

-

Semi-log plot of daily new cases of COVID-19 (7-day average) in the world and top five countries (mean with deaths)

-

Semi-log plot of cases in some countries with high growth rates (post-China) with three-day projections based on the exponential growth rates

-

7-day rolling average of daily confirmed cases per million by country.[74]

-

Linear plot of worldwide COVID-19 cases, recoveries, and deaths[75]

-

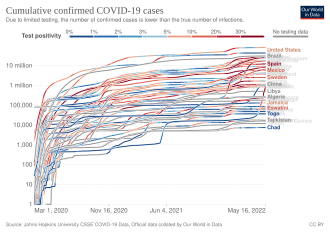

COVID-19 total cases per 100 000 population from selected countries[76]

Deaths

Most people who contract COVID-19 recover. For those who do not, the time between the onset of symptoms and death usually ranges from 6 to 41 days, typically about 14 days.[77] As of 10 March 2023, approximately 6.88 million[6] deaths had been attributed to COVID-19. In China, as of 5 February[update], about 80 per cent of deaths were recorded in those aged over 60, and 75 per cent had pre-existing health conditions including cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.[78]

The first confirmed death was in Wuhan on 9 January 2020.[79] The first death outside China occurred on 1 February in the Philippines,[80] and the first death outside Asia was in France on 14 February.[81]

Official deaths from COVID-19 generally refer to people who died after testing positive according to protocols. This may ignore deaths of people who die without testing, e.g. at home or in nursing homes.[82] Conversely, deaths of people who had underlying conditions may lead to overcounting.[83] Comparison of statistics for deaths for all causes versus the seasonal average indicates excess mortality in many countries.[84][85] In the worst affected areas, mortality has been several times higher than average. In New York City, deaths have been four times higher than average, in Paris twice as high, and in many European countries deaths have been on average 20 to 30 per cent higher than normal.[84] This excess mortality may include deaths due to strained healthcare systems and bans on elective surgery.[86]

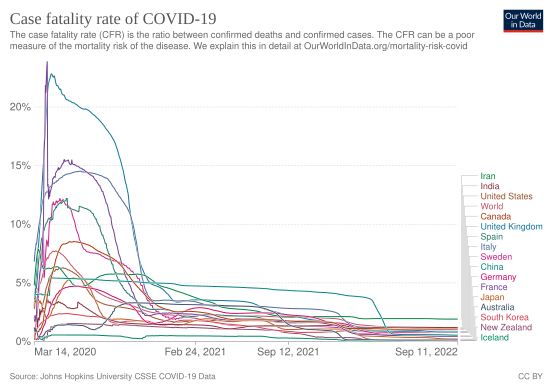

Several measures are used to quantify mortality.[87] These numbers vary by region and over time, influenced by testing volume, healthcare system quality, treatment options, time since initial outbreak, and population characteristics, such as age, sex, and overall health.[88] Some countries (like Belgium) include deaths from suspected cases of COVID-19, regardless of whether the person was tested, resulting in higher numbers compared to countries that include only test-confirmed cases.[89]

The death-to-case ratio reflects the number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 divided by the number of diagnosed cases within a given time interval. Based on Johns Hopkins University statistics, the global death-to-case ratio is 1.02 per cent (6,881,955 deaths for 676,609,955 cases) as of 10 March 2023.[6] The number varies by region.[90]

Other measures include the case fatality rate (CFR), which reflects the percentage of diagnosed people who die from a disease, and the infection fatality rate (IFR), which reflects the percentage of infected (diagnosed and undiagnosed) who die from a disease. These statistics are not timebound and follow a specific population from infection through case resolution. Our World in Data states that as of 25 March 2020 the IFR cannot be accurately calculated as neither the total number of cases nor the total deaths, is known.[91] In February the Institute for Disease Modeling estimated the IFR as 0.94% (95% confidence interval 0.37-2.9), based on data from China.[92][93] The University of Oxford's Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) estimated a global CFR of 0.82 per cent and IFR of 0.1 per cent to 0.41 per cent, acknowledging that this will vary between populations due to differences in demographics.[94]

-

Total confirmed deaths due to COVID-19 per million people[95]

-

Semi-log plot of daily deaths due to COVID-19 (7-day average) in the world and top five countries (mean with cases)

-

Case fatality rate of COVID-19 by country and confirmed cases

-

Ongoing case fatality rate of COVID-19 by country

-

COVID-19 deaths per 100 000 population from selected countries[96]

Duration

The WHO said on 11 March 2020 the pandemic could be controlled.[9] The peak and ultimate duration of the outbreak are uncertain and may differ by location. Maciej Boni of Penn State University said, "Left unchecked, infectious outbreaks typically plateau and then start to decline when the disease runs out of available hosts. But it's almost impossible to make any sensible projection right now about when that will be."[97] The Imperial College study led by Neil Ferguson stated that physical distancing and other measures will be required "until a vaccine becomes available (potentially 18 months or more)".[98] William Schaffner of Vanderbilt University said because the coronavirus is "so readily transmissible", it "might turn into a seasonal disease, making a comeback every year". The virulence of the comeback would depend on herd immunity and the extent of mutation.[99]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of COVID-19 can be relatively non-specific and infected people may be asymptomatic. The two most common symptoms are fever (88 per cent) and dry cough (68 per cent). Less common symptoms include fatigue, respiratory sputum production (phlegm), loss of the sense of smell, loss of taste, shortness of breath, muscle and joint pain, sore throat, headache, chills, vomiting, coughing out blood, and diarrhea.[101][102][103]

Approximately one in five people become seriously ill and has difficulty breathing.[10] Emergency symptoms include difficulty breathing, persistent chest pain or pressure, sudden confusion, difficulty waking, and bluish face or lips; immediate medical attention is advised if these symptoms are present.[12] Further development of the disease can lead to complications including pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, septic shock, and kidney failure.[102]

Some infected people have no symptoms, known as asymptomatic or presymptomatic carriers.[101][104] Transmission from such a carrier can occur.[101][104] Health authorities have issued public notices that people with close contact to confirmed infected people should be quarantined and closely monitored.[101][105][103] Chinese estimates of the asymptomatic ratio range from few to 44 per cent.[106] The usual incubation period (the time between infection and symptom onset) ranges from one to 14 days, and is most commonly five days.[10][107]

Cause

Transmission

Virology

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a novel virus, first isolated from three people with pneumonia connected to the cluster of acute respiratory illness cases in Wuhan.[41] All features of the novel SARS‑CoV‑2 virus occur in related coronaviruses in nature.[108]

SARS‑CoV‑2 is closely related to SARS‑CoV, and is thought to have a zoonotic origin.[38] SARS‑CoV‑2 genetically clusters with the genus Betacoronavirus, and is 96 per cent identical at the whole genome level to other bat coronavirus samples[109] and 92 per cent identical to pangolin coronavirus.[110]

Diagnosis

COVID-19 can be provisionally diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and confirmed using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing of infected secretions or CT imaging of the chest.[111][112]

Viral testing

The standard test for current infection with SARS-CoV-2 uses RNA testing of respiratory secretions collected using a nasopharyngeal swab, though it is possible to test other samples. This test uses real-time rRT-PCR which detects presence of viral RNA fragments.[113]

A number of laboratories and companies have developed serological tests, which detect antibodies produced by the body in response to infection.[114] Several have been evaluated by Public Health England and approved for use in the UK.[115]

Imaging

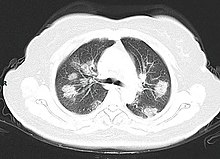

Characteristic imaging features on chest radiographs and computed tomography (CT) of people who are symptomatic include asymmetric peripheral ground-glass opacities without pleural effusions.[116] The Italian Radiological Society is compiling an international online database of imaging findings for confirmed cases.[117] Due to overlap with other infections such as adenovirus, imaging without confirmation by rRT-PCR is of limited specificity in identifying COVID-19.[116] A large study in China compared chest CT results to PCR and demonstrated that though imaging is less specific for the infection, it is faster and more sensitive.[112]

Prevention

Strategies for preventing transmission of the disease include maintaining overall good personal hygiene, washing hands, avoiding touching the eyes, nose, or mouth with unwashed hands, and coughing or sneezing into a tissue, and putting the tissue directly into a waste container. Those who may already have the infection have been advised to wear a surgical mask in public.[118][119] Physical distancing measures are also recommended to prevent transmission.[120][121] Health care providers taking care of someone who may be infected are recommended to use standard precautions, contact precautions, and eye protection.[122]

Many governments have restricted or advised against all non-essential travel to and from countries and areas affected by the outbreak.[123] The virus has already spread within communities in large parts of the world, with many not knowing where or how they were infected.[124]

Misconceptions are circulating about how to prevent infection; for example, rinsing the nose and gargling with mouthwash are not effective.[125] There is no COVID-19 vaccine, though many organisations are working to develop one.[126]

Hand washing

Hand washing is recommended to prevent the spread of the disease. The CDC recommends that people wash hands often with soap and water for at least twenty seconds, especially after going to the toilet or when hands are visibly dirty; before eating; and after blowing one's nose, coughing, or sneezing. This is because outside the human body, the virus is killed by household soap, which bursts its protective bubble.[17] CDC further recommended using an alcohol-based hand sanitiser with at least 60 per cent alcohol by volume when soap and water are not readily available.[118] The WHO advises people to avoid touching the eyes, nose, or mouth with unwashed hands.[119][127] It is not clear if washing hands with ash if soap is not available is effective at reducing the spread of viral infections.[128]

Surface cleaning

Surfaces may be decontaminated with a number of solutions (within one minute of exposure to the disinfectant for a stainless steel surface), including 62–71 per cent ethanol, 50–100 per cent isopropanol, 0.1 per cent sodium hypochlorite, 0.5 per cent hydrogen peroxide, and 0.2–7.5 per cent povidone-iodine. Other solutions, such as benzalkonium chloride and chlorhexidine gluconate, are less effective.[129] The CDC recommends that if a COVID-19 case is suspected or confirmed at a facility such as an office or day care, all areas such as offices, bathrooms, common areas, shared electronic equipment like tablets, touch screens, keyboards, remote controls, and ATM machines used by the ill persons, should be disinfected.[130]

Face masks and respiratory hygiene

Recommendations for wearing masks have been a subject of debate.[131] The WHO has recommended healthy people wear masks only if they are at high risk, such as those who are caring for a person with COVID-19.[132] China and the United States, among other countries, have encouraged the use of face masks or cloth face coverings more generally by members of the public to limit the spread of the virus by asymptomatic individuals as a precautionary principle.[133][134] Several national and local governments have made wearing masks mandatory.[135]

Surgical masks are recommended for those who may be infected, as wearing this type of mask can limit the volume and travel distance of expiratory droplets dispersed when talking, sneezing, and coughing.[132]

Social distancing

Social distancing (also known as physical distancing) includes infection control actions intended to slow the spread of disease by minimising close contact between individuals. Methods include quarantines; travel restrictions; and the closing of schools, workplaces, stadiums, theatres, or shopping centres. Individuals may apply social distancing methods by staying at home, limiting travel, avoiding crowded areas, using no-contact greetings, and physically distancing themselves from others.[119][136][137] Many governments are now mandating or recommending social distancing in regions affected by the outbreak.[138][139] Non-cooperation with distancing measures in some areas has contributed to the further spread of the pandemic.[140]

The maximum gathering size recommended by U.S. government bodies and health organisations was swiftly reduced from 250 people (if there was no known COVID-19 spread in a region) to 50 people, and later to 10.[141] On 22 March 2020, Germany banned public gatherings of more than two people.[142] A Cochrane review found that early quarantine with other public health measures are effective in limiting the pandemic, but the best manner of adopting and relaxing policies are uncertain, as local conditions vary.[137]

Older adults and those with underlying medical conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, respiratory disease, hypertension, and compromised immune systems face increased risk of serious illness and complications and have been advised by the CDC to stay home as much as possible in areas of community outbreak.[143][144]

In late March 2020, the WHO and other health bodies began to replace the use of the term "social distancing" with "physical distancing", to clarify that the aim is to reduce physical contact while maintaining social connections, either virtually or at a distance. The use of the term "social distancing" had led to implications that people should engage in complete social isolation, rather than encouraging them to stay in contact through alternative means.[145][146]

Some authorities have issued sexual health guidelines for use during the pandemic. These include recommendations to have sex only with someone you live with, and who does not have the virus or symptoms of the virus.[147][148]

Self-isolation

Self-isolation at home has been recommended for those diagnosed with COVID-19 and those who suspect they have been infected. Health agencies have issued detailed instructions for proper self-isolation.[149][150]

Many governments have mandated or recommended self-quarantine for entire populations living in affected areas.[151][152] The strongest self-quarantine instructions have been issued to those in high risk groups. Those who may have been exposed to someone with COVID-19 and those who have recently travelled to a country or region with widespread transmission have been advised to self-quarantine for 14 days from the time of last possible exposure.[10][14][153]

Management

Containment and mitigation

Strategies in the control of an outbreak are containment or suppression, and mitigation. Containment is undertaken in the early stages of the outbreak and aims to trace and isolate those infected as well as introduce other measures of infection control and vaccinations to stop the disease from spreading to the rest of the population. When it is no longer possible to contain the spread of the disease, efforts then move to the mitigation stage: measures are taken to slow the spread and mitigate its effects on the healthcare system and society. A combination of both containment and mitigation measures may be undertaken at the same time.[158] Suppression requires more extreme measures so as to reverse the pandemic by reducing the basic reproduction number to less than 1.[98]

Part of managing an infectious disease outbreak is trying to delay and decrease the epidemic peak, known as flattening the epidemic curve.[154] This decreases the risk of health services being overwhelmed and provides more time for vaccines and treatments to be developed.[154] Non-pharmaceutical interventions that may manage the outbreak include personal preventive measures such as hand hygiene, wearing face masks, and self-quarantine; community measures aimed at physical distancing such as closing schools and cancelling mass gathering events; community engagement to encourage acceptance and participation in such interventions; as well as environmental measures such surface cleaning.[159]

More drastic actions aimed at containing the outbreak were taken in China once the severity of the outbreak became apparent, such as quarantining entire cities and imposing strict travel bans.[160] Other countries also adopted a variety of measures aimed at limiting the spread of the virus. South Korea introduced mass screening and localised quarantines, and issued alerts on the movements of infected individuals. Singapore provided financial support for those infected who quarantined themselves and imposed large fines for those who failed to do so. Taiwan increased face mask production and penalised hoarding of medical supplies.[161]

Simulations for Great Britain and the United States show that mitigation (slowing but not stopping epidemic spread) and suppression (reversing epidemic growth) have major challenges. Optimal mitigation policies might reduce peak healthcare demand by two-thirds and deaths by half, but still result in hundreds of thousands of deaths and overwhelmed health systems. Suppression can be preferred but needs to be maintained for as long as the virus is circulating in the human population (or until a vaccine becomes available), as transmission otherwise quickly rebounds when measures are relaxed. Long-term intervention to suppress the pandemic has considerable social and economic costs.[98]

The researchers at Monash Venom Research Group found the peptide inside snakes' venom they were already looking at for Alzheimer’s disease may help in the fight, or future fights, against COVID-19. It binds to an enzyme called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 which plays an important role in the cardiovascular system. Activating the enzyme also causes improvements in vascular function and it makes the blood vessels relax. This enzyme is also the receptor for COVID-19. Very early studies show it can stop the binding of proteins (the “spikes” in commonly seen images of the virus) to the cells. Although it is in very preliminary stage, but it shows a lot of promise.[162]

Contact tracing

Contact tracing is an important method for health authorities to determine the source of an infection and to prevent further transmission.[163] The use of location data from mobile phones by governments for this purpose has prompted privacy concerns, with Amnesty International and more than a hundred other organisations issuing a statement calling for limits on this kind of surveillance.[164]

Several mobile apps have been implemented or proposed for voluntary use, and as of 7 April 2020 more than a dozen expert groups were working on privacy-friendly solutions such as using Bluetooth to log a user's proximity to other cellphones.[164] Users could then receive a message if they've been in close contact with someone who has subsequently tested positive for COVID-19.[164]

On 10 April 2020 Google and Apple jointly announced an initiative for privacy-preserving contact tracing based on Bluetooth technology and cryptography.[165][166] The system is intended to allow governments to create official privacy-preserving coronavirus tracking apps, with the eventual goal of integration of this functionality directly into the iOS and Android mobile platforms.[167] In Europe and in the U.S., Palantir Technologies is also providing COVID-19 tracking services.[168]

Health care

Increasing capacity and adapting healthcare for the needs of COVID-19 patients is described by the WHO as a fundamental outbreak response measure.[169] The ECDC and the European regional office of the WHO have issued guidelines for hospitals and primary healthcare services for shifting of resources at multiple levels, including focusing laboratory services towards COVID-19 testing, cancelling elective procedures whenever possible, separating and isolating COVID-19 positive patients, and increasing intensive care capabilities by training personnel and increasing the number of available ventilators and beds.[169][170]

Due to capacity limitations in the standard supply chains, some manufacturers are 3D printing healthcare material such as nasal swabs and ventilator parts.[171][172] In one example, when an Italian hospital urgently required a ventilator valve, and the supplier was unable to deliver in the timescale required, a local startup received legal threats due to alleged patent infringement and reverse-engineered and printed the required hundred valves overnight.[173][174][175] On 23 April 2020, NASA reported building, in 37 days, a ventilator which is currently undergoing further testing. NASA is seeking fast-track approval.[176][177]

Treatment

Antiviral medications are under investigation for COVID-19, as well as medications targeting the immune response.[178] None has yet been shown to be clearly effective on mortality in published randomised controlled trials.[178] However, remdesivir may have an effect on the time it takes to recover from the virus.[179] Emergency use authorisation for remdesivir was granted in the U.S. on 1 May, for people hospitalised with severe COVID-19. The interim authorisation was granted considering the lack of other specific treatments, and that its potential benefits appear to outweigh the potential risks.[180] Taking over-the-counter cold medications,[181] drinking fluids, and resting may help alleviate symptoms.[118] Depending on the severity, oxygen therapy, intravenous fluids, and breathing support may be required.[182] The use of steroids may worsen outcomes.[183] Several compounds which were previously approved for treatment of other viral diseases are being investigated for use in treating COVID-19.[184]

History

There are several theories about where the very first case (the so-called patient zero) originated.[186] The first known case may trace back to 1 December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei, China.[45] Over the next month, the number of coronavirus cases in Hubei gradually increased. According to official Chinese sources, these were mostly linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, which also sold live animals.[37]

On 24 December, Wuhan Central Hospital sent a bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) sample from an unresolved clinical case to sequencing company Vision Medicals. On 27 and 28 December, Vision Medicals informed the Wuhan Central Hospital and the Chinese CDC of the results of the test, showing a new coronavirus.[187] A pneumonia cluster of unknown cause was observed on 26 December and treated by the doctor Zhang Jixian in Hubei Provincial Hospital, who informed the Wuhan Jianghan CDC on 27 December.[188][189] On 30 December, a test report addressed to Wuhan Central Hospital, from company CapitalBio Medlab, stated an erroneous positive result for SARS, causing a group of doctors at Wuhan Central Hospital to alert their colleagues and relevant hospital authorities of the result. That evening, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission issued a notice to various medical institutions on "the treatment of pneumonia of unknown cause".[190] Eight of these doctors, including Li Wenliang (punished on 3 January),[191] were later admonished by the police for spreading false rumours, and another, Ai Fen, was reprimanded by her superiors for raising the alarm.[192]

The Wuhan Municipal Health Commission made the first public announcement of a pneumonia outbreak of unknown cause on 31 December, confirming 27 cases[31][193][194]—enough to trigger an investigation.[33]

During the early stages of the outbreak, the number of cases doubled approximately every seven and a half days.[195] In early and mid-January 2020, the virus spread to other Chinese provinces, helped by the Chinese New Year migration and Wuhan being a transport hub and major rail interchange.[109] On 20 January, China reported nearly 140 new cases in one day, including two people in Beijing and one in Shenzhen.[196] Later official data shows 6,174 people had already developed symptoms by then,[197] and more may have been infected.[198] A report in The Lancet on 24 January indicated human transmission, strongly recommended personal protective equipment for health workers, and said testing for the virus was essential due to its "pandemic potential".[47][199] On 30 January, the WHO declared the coronavirus a public health emergency of international concern.[198]

On 31 January 2020, Italy had its first confirmed cases, two tourists from China.[200] As of 13 March 2020 the WHO considered Europe the active centre of the pandemic.[201] On 19 March 2020, Italy overtook China as the country with the most deaths.[202] By 26 March, the United States had overtaken China and Italy with the highest number of confirmed cases in the world.[203] Research on coronavirus genomes indicates the majority of COVID-19 cases in New York came from European travellers, rather than directly from China or any other Asian country.[204] Retesting of prior samples found a person in France who had the virus on 27 December 2019[205][206] and a person in the United States who died from the disease on 6 February 2020.[207]

As of 15 May 2020[update], more than 676 million cases have been reported worldwide; more than 6.88 million people have died and more than have recovered.[208][209]

National responses

A total of [6] countries and territories have had at least one case of COVID-19 so far. Due to the pandemic in Europe, many countries in the Schengen Area have restricted free movement and set up border controls.[210] National reactions have included containment measures such as quarantines and curfews (known as stay-at-home orders, shelter-in-place orders, or lockdowns).[211]

By 26 March, 1.7 billion people worldwide were under some form of lockdown,[212] which increased to 3.9 billion people by the first week of April—more than half the world's population.[213][214]

By late April, around 300 million people were under lockdown in nations of Europe, including but not limited to Italy, Spain, France, and the United Kingdom, while around 200 million people were under lockdown in Latin America.[215] Nearly 300 million people, or about 90 per cent of the population, were under some form of lockdown in the United States,[216] around 100 million people in the Philippines,[215] about 59 million people in South Africa,[217] and 1.3 billion people have been under lockdown in India.[218][219]

Asia

As of 30 April 2020[update], cases have been reported in all Asian countries except for Turkmenistan[220] and North Korea,[221] although some suspect these countries also have cases.[citation needed]

China

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 has been traced back to 1 December 2019 in Wuhan;[45] one unconfirmed report suggests the earliest case was on 17 November.[50] Doctor Zhang Jixian observed a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown cause on 26 December, upon which her hospital informed Wuhan Jianghan CDC on 27 December.[222][223] Initial genetic testing of patient samples on 27 December 2019 indicated the presence of a SARS-like coronavirus.[222] A public notice was released by Wuhan Municipal Health Commission on 31 December, confirming 27 cases and suggesting wearing face masks.[194] The WHO was informed on the same day.[31] As these notifications occurred, doctors in Wuhan were warned by police for "spreading rumours" about the outbreak.[224] The Chinese National Health Commission initially said there was no "clear evidence" of human-to-human transmission.[225] In a 14 January conference call, Chinese officials said privately that human-to-human transmission was a possibility, and pandemic preparations were needed.[226] In a briefing posted during the night of 14–15 January, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission said the possibility of limited human-to-human transmission could not be ruled out.[227]

On 20 January, the Chinese National Health Commission announced that human-to-human transmission of the coronavirus had already occurred.[228] That same day, Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping and State Council premier Li Keqiang issued their first public comments about the virus, telling people in infected areas to practice social distancing and avoid travel.[229][230] During the Chinese New Year travel period, authorities instigated a City of Wuhan lockdown.[231] On 10 February, since Wuhan travellers already transported the virus to some Asian countries,[232][233][234] the Chinese government launched a radical campaign described by paramount leader and Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi as a "people's war" to contain the viral spread.[235] In "the largest quarantine in human history",[236] a cordon sanitaire on 23 January stopped travel in and out of Wuhan,[237][238] then extended to fifteen Hubei cities affecting about 57 million people.[239] Private vehicle use was banned in the city.[240] Several Chinese New Year (25 January) celebrations were also cancelled.[241] Authorities announced the construction of a temporary hospital, Huoshenshan Hospital, completed in ten days.[242] Leishenshan Hospital, was later built to handle additional patients.[243] China also converted other facilities in Wuhan, such as convention centres and stadiums, into temporary hospitals.[244]

On 26 January, the government instituted further measures to contain the COVID-19 outbreak, including issuing health declarations for travellers[246] and extending the Spring Festival holiday.[247] Universities and schools around the country were also closed.[248][249][250] The regions of Hong Kong and Macau instituted several measures, particularly in regard to schools and universities.[251] Remote working measures were instituted in several Chinese regions.[252] Travel restrictions were enacted in and outside of Hubei.[252][253] Public transport was modified,[254] and museums throughout China were temporarily closed.[252][255][256] Control of public movement was applied in many cities, and it has been estimated that 760 million people (more than half the population) faced some form of outdoor restriction.[257] In January and February 2020, during the height of the epidemic in Wuhan, about 5 million people lost their jobs.[258] Many of China's nearly 300 million rural migrant workers have been stranded at home in inland provinces or trapped in Hubei province.[259][260]

After the outbreak entered its global phase in March, Chinese authorities took strict measures to prevent the virus re-entering China from other countries. For example, Beijing imposed a 14-day mandatory quarantine for all international travellers entering the city.[261] At the same time, a strong anti-foreigner sentiment quickly took hold,[262] and foreigners experienced harassment by the general public[263] and forced evictions from apartments and hotels.[29][264]

On 23 March 2020, China had only one case transmitted domestically in the five days prior, in this instance via a traveller returning to Guangzhou from Istanbul. On 24 March, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang reported that the spread of domestically transmitted cases has been basically blocked and the outbreak has been controlled in China.[265] The same day travel restrictions were eased in Hubei, apart from Wuhan, two months after the lockdown was imposed.[266]

The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced on 26 March that entry for visa or residence permit holders would be suspended from 28 March onwards, with no specific details on when this policy would end. Those wishing to enter China must to apply for visas in Chinese embassies or consulates.[267][268] The Chinese government encouraged businesses and factories to re-open on 30 March, and provided monetary stimulus packages for firms.[269]

The State Council declared a day of mourning to begin with a national three-minute moment of silence on 4 April, coinciding with Qingming Festival, although the central government asked families to pay their respects online in observance of physical distancing to avoid a renewed COVID-19 outbreak.[270] On 25 April the last patients were discharged in Wuhan.[271] On 13 May the city of Jilin was put on lockdown, sparking fear of a second wave of infection.[272]

Iran

Iran reported its first confirmed cases of SARS‑CoV‑2 infections on 19 February in Qom, where, according to the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, two people died later that day.[274][275] Early measures announced by the government included the cancellation of concerts and other cultural events,[276] sporting events,[277] and Friday prayers,[278] and closures of universities, higher education institutions, and schools.[279] Iran allocated 5 trillion rials (equivalent to US$120,000,000) to combat the virus.[280] President Hassan Rouhani said on 26 February 2020 there were no plans to quarantine areas affected by the outbreak, and only individuals would be quarantined.[281] Plans to limit travel between cities were announced in March,[282] although heavy traffic between cities ahead of the Persian New Year Nowruz continued.[283] Shia shrines in Qom remained open to pilgrims until 16 March.[284][285]

Iran became a centre of the spread of the virus after China during February.[286][287] More than ten countries had traced their cases back to Iran by 28 February, indicating the outbreak may have been more severe than the 388 cases reported by the Iranian government by that date.[287][288] The Iranian Parliament was shut down, with 23 of its 290 members reported to have had tested positive for the virus on 3 March.[289] On 15 March, the Iranian government reported a hundred deaths in a single day, the most recorded in the country since the outbreak began.[290] At least twelve sitting or former Iranian politicians and government officials had died from the disease by 17 March.[291] By 23 March, Iran was experiencing fifty new cases every hour and one new death every ten minutes due to coronavirus.[292] According to a WHO official, there may be five times more cases in Iran than what is being reported. It is also suggested that U.S. sanctions on Iran may be affecting the country's financial ability to respond to the viral outbreak.[293] The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has demanded economic sanctions to be eased for nations most affected by the pandemic, including Iran.[294] On 20 April it was reported that Iran had reopened shopping malls and other shopping areas across the country, though there is fear of a second wave of infection due to this move.[295] In March and again in April, there were reports that Iran was under-reporting COVID-19 cases and deaths.[296][297] On 27 April it was reported that 700 people had died from ingesting methanol, falsely believed to be a cure.[298]

South Korea

COVID-19 was confirmed to have spread to South Korea on 20 January 2020 from China. The nation's health agency reported a significant increase in confirmed cases on 20 February,[299] largely attributed to a gathering in Daegu of the Shincheonji Church of Jesus.[299][300] Shincheonji devotees visiting Daegu from Wuhan were suspected to be the origin of the outbreak.[301][302] As of 22 February[update], among 9,336 followers of the church, 1,261 or about 13 per cent reported symptoms.[303]

South Korea declared the highest level of alert on 23 February 2020.[304] On 28 February, more than 2,000 confirmed cases were reported,[305] rising to 3,150 on 29 February.[306] All South Korean military bases were quarantined after tests showed three soldiers had the virus.[301] Airline schedules were also changed.[307][308]

South Korea introduced what was considered the largest and best-organised programme in the world to screen the population for the virus, isolate any infected people, and trace and quarantine those who contacted them.[309][310] Screening methods included mandatory self-reporting of symptoms by new international arrivals through mobile application,[311] drive-through testing for the virus with the results available the next day,[312] and increasing testing capability to allow up to 20,000 people to be tested every day.[313] South Korea's programme is considered a success in controlling the outbreak without quarantining entire cities.[309][314]

South Korean society was initially polarised on President Moon Jae-in's response to the crisis, many signing petitions either praising it or calling for impeachment.[315] On 23 March, it was reported that South Korea had the lowest one-day case total in four weeks.[313] On 29 March it was reported that beginning 1 April all new overseas arrivals will be quarantined for two weeks.[316] Per media reports on 1 April, South Korea has received requests for virus testing assistance from 121 different countries.[317] On 15 May it was reported that about 2,000 businesses were told to close again when a cluster of 100 COVID-19 infected individuals was discovered, contact tracing is being done on 11,000 people.[318]

Europe

The global COVID-19 pandemic arrived in Europe with its first confirmed case in Bordeaux, France, on 24 January 2020, and subsequently spread widely across the continent. By 17 March 2020, every country in Europe had confirmed a case,[319] and all have reported at least one death, with the exception of Vatican City.

Italy was the first European country to experience a major outbreak in early 2020, becoming the first country worldwide to introduce a national lockdown.[320] By 13 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Europe the epicentre of the pandemic[321][322] and it remained so until the WHO announced it was overtaken by South America on 22 May.[323] By 18 March 2020, lockdowns introduced in Europe affected more than 250 million people.[324] Despite deployment of COVID-19 vaccines, Europe became the pandemic's epicentre once again in late 2021.[325] On 11 January 2022, Dr. Hans Kluge, the WHO Regional Director for Europe said, "more than 50 percent of the population in the region will be infected with Omicron in the next six to eight weeks".[326]

As the outbreak became a major crisis across Europe, national and European Union responses have led to debate over restrictions of civil liberties and the extent of European Union solidarity.

As of 20 May 2022, Europe is the most affected continent in the world. Most affected countries in Europe include France, Germany, the United Kingdom and Russia.Italy

The outbreak was confirmed to have spread to Italy on 31 January, when two Chinese tourists tested positive for SARS‑CoV‑2 in Rome.[200] Cases began to rise sharply, which prompted the Italian government to suspend all flights to and from China and declare a state of emergency.[327] An unassociated cluster of COVID-19 cases was later detected, starting with 16 confirmed cases in Lombardy on 21 February.[328]

On 22 February, the Council of Ministers announced a new decree-law to contain the outbreak, including quarantining more than 50,000 people from eleven different municipalities in northern Italy.[329] Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte said, "In the outbreak areas, entry and exit will not be provided. Suspension of work activities and sports events has already been ordered in those areas."[330][331]

On 4 March, the Italian government ordered the full closure of all schools and universities nationwide as Italy reached a hundred deaths. All major sporting events, including Serie A football matches, were to be held behind closed doors until April,[332] but on 9 March, all sport was suspended completely for at least one month.[333] On 11 March, Prime Minister Conte ordered stoppage of nearly all commercial activity except supermarkets and pharmacies.[334][335]

On 6 March, the Italian College of Anaesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Care (SIAARTI) published medical ethics recommendations regarding triage protocols.[336][337][338] On 19 March, Italy overtook China as the country with the most coronavirus-related deaths in the world after reporting 3,405 fatalities from the pandemic.[339][340] On 22 March, it was reported that Russia had sent nine military planes with medical equipment to Italy.[341] As of 9 May[update], there were 217,185 confirmed cases, 30,201 deaths, and 99,023 recoveries in Italy, with the majority of those cases occurring in the Lombardy region.[342] A CNN report indicated that the combination of Italy's large elderly population and inability to test all who have the virus to date may be contributing to the high fatality rate.[343] On 19 April it was reported that the country had its lowest deaths at 433 in seven days, some businesses after six weeks of lockdown are asking for a loosening of restrictions.[344]

Spain

The COVID-19 pandemic in Spain has resulted in 13,980,340[30] confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 121,852[30] deaths.

The virus was first confirmed to have spread to Spain on 31 January 2020, when a German tourist tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in La Gomera, Canary Islands.[345] Post-hoc genetic analysis has shown that at least 15 strains of the virus had been imported, and community transmission began by mid-February.[346] By 13 March, cases had been confirmed in all 50 provinces of the country.

A partially unconstitutional lockdown was imposed on 14 March 2020.[347][348] On 29 March, it was announced that, beginning the following day, all non-essential workers were ordered to remain at home for the next 14 days.[349] By late March, the Community of Madrid has recorded the most cases and deaths in the country. Medical professionals and those who live in retirement homes have experienced especially high infection rates.[350] On 25 March, the official death toll in Spain surpassed that of mainland China.[351] On 2 April, 950 people died of the virus in a 24-hour period—at the time, the most by any country in a single day.[352] On 17 May, the daily death toll announced by the Spanish government fell below 100 for the first time,[353] and 1 June was the first day without deaths by COVID-19.[354] The state of alarm ended on 21 June.[355] However, the number of cases increased again in July in a number of cities including Barcelona, Zaragoza and Madrid, which led to reimposition of some restrictions but no national lockdown.[356][357][358][359]

Studies have suggested that the number of infections and deaths may have been underestimated due to lack of testing and reporting, and many people with only mild or no symptoms were not tested.[360][361] Reports in May suggested that, based on a sample of more than 63,000 people, the number of infections may be ten times higher than the number of confirmed cases by that date, and Madrid and several provinces of Castilla–La Mancha and Castile and León were the most affected areas with a percentage of infection greater than 10%.[362][363] There may also be as many as 15,815 more deaths according to the Spanish Ministry of Health monitoring system on daily excess mortality (Sistema de Monitorización de la Mortalidad Diaria – MoMo).[364] On 6 July 2020, the results of a Government of Spain nationwide seroprevalence study showed that about two million people, or 5.2% of the population, could have been infected during the pandemic.[365][366] Spain was the second country in Europe (behind Russia) to record half a million cases.[367] On 21 October, Spain passed 1 million COVID-19 cases, with 1,005,295 infections and 34,366 deaths reported, a third of which occurred in Madrid.[368]

As of September 2021, Spain is one of the countries with the highest percentage of its population vaccinated (76% fully vaccinated and 79% with the first dose),[369] while also being one of the countries more in favor of vaccines against COVID-19 (nearly 94% of its population is already vaccinated or wants to be).[370]

As of 4 February 2023, a total of 112,304,453 vaccine doses have been administered.[371]Russia

The COVID-19 pandemic spread to Russia on 31 January 2020, when two Chinese citizens in Tyumen, Siberia and Chita, Russian Far East tested positive for the virus, with both cases being contained. Early prevention measures included restricting the border with China and extensive testing. The infection spread from Italy on 2 March, leading to additional measures such as cancelling events, closing schools, theatres and museums, shutting the border, and declaring a non-working period which lasted up to 11 May, having been extended twice. By the end of March, lockdowns were imposed in the vast majority of federal subjects, including Moscow. By 17 April, cases were confirmed in all federal subjects. On 27 April, the number of confirmed cases surpassed those in China and on 30 April, it surpassed 100,000.

As of 16 May, Russia has 272,043 confirmed cases, 63,166 recoveries, 2,537 deaths, and over 6.6 million tests performed, ranking second in number of confirmed cases.[372][373]The city of Moscow is currently the most affected federal subject, having the majority of confirmed cases.[372][373]

United Kingdom

Before 18 March 2020, the British government did not impose any form of social distancing or mass quarantine measures on its citizens.[374][375] As a result, the government received criticism for the perceived lack of pace and intensity in its response to concerns faced by the public.[376][377]

On 16 March, Prime Minister Boris Johnson made an announcement advising against all non-essential travel and social contact, suggesting people work from home where possible and avoid venues such as pubs, restaurants, and theatres.[378][379] On 20 March, the government announced that all leisure establishments such as pubs and gyms were to close as soon as possible,[380] and promised to pay up to 80 per cent of workers' wages to a limit of £2,500 per month to prevent unemployment during the crisis.[381]

On 23 March, the prime minister announced tougher social distancing measures, banning gatherings of more than two people and restricting travel and outdoor activity to that deemed strictly necessary. Unlike previous measures, these restrictions were enforceable by police through the issuing of fines and the dispersal of gatherings. Most businesses were ordered to close, with exceptions for businesses deemed "essential", including supermarkets, pharmacies, banks, hardware shops, petrol stations, and garages.[382]

On 24 April it was reported that one of the more promising vaccine trials had begun in England; the government has pledged, in total, more than 50 million pounds towards research.[383]

To ensure the UK health services had sufficient capacity to treat people with COVID-19, a number of temporary critical care hospitals were built.[384] The first to be operational was the 4000-bed capacity NHS Nightingale Hospital London, constructed within the ExCeL convention centre over nine days.[385] On 4 May, it was announced that the Nightingale Hospital in London would be placed on standby and remaining patients transferred to other facilities.[386] This comes after reports that NHS Nightingale in London "treated 51 patients" within the first three weeks of opening.[387] On 5 May, official figures revealed that Britain had the worst COVID-19 death toll in Europe, prompting calls for an inquiry into the handling of the pandemic. The death toll in the United Kingdom was nearly 29,427 for those tested positive for the virus. Later, it was calculated at 32,313, after taking the official death count for Scotland and Northern Ireland into account.[388]

France

Although it was originally thought the pandemic reached France on 24 January 2020, when the first COVID-19 case in Europe was confirmed in Bordeaux, it was later discovered that a person near Paris had tested positive for the virus on 27 December 2019 after retesting old samples.[205][206] A key event in the spread of the disease in the country was the annual assembly of the Christian Open Door Church between 17 and 24 February in Mulhouse, which was attended by about 2,500 people, at least half of whom are believed to have contracted the virus.[389][390]

On 13 March, Prime Minister Édouard Philippe ordered the closure of all non-essential public places,[391] and on 16 March, French President Emmanuel Macron announced mandatory home confinement, a policy which has been extended at least until 11 May.[392][393][394] As of 23 April[update], France has reported more than 120,804 confirmed cases, 21,856 deaths, and 42,088 recoveries,[395] ranking fourth in number of confirmed cases.[396] In April, there were riots in some Paris suburbs.[397]

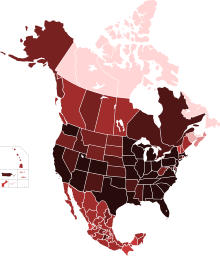

North America

The first cases of the COVID-19 pandemic of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in North America were reported in the United States on 23 January 2020. Cases were reported in all North American countries after Saint Kitts and Nevis confirmed a case on 25 March, and in all North American territories after Bonaire confirmed a case on 16 April.[398]

On 26 March 2020, the United States became the country in North America with the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 infections, at over 82,000 cases.[399] On 11 April 2020, the United States became the country in North America with the highest official death toll for COVID-19, at over 20,000 deaths.[400] As of 10 April 2022, there are about 97 million cases and about 1.4 million deaths in North America; about 88.9 million have recovered from COVID-19, meaning that nearly 11 out of 12 cases have recovered or that the recovery rate is nearly 92%.[401]

As of 10 April 2022, the United States has had the highest number of cases in North America, at about 82 million cases, as well as the highest death toll, at over a million deaths. There have been nearly 75.7 million recoveries in the United States as of 10 April 2022, meaning that nearly 12 out of 13 cases in the country have recovered or that the recovery rate is about 92%. On 20 March 2022, the number of COVID-19 deaths in the United States exceeded a million.

As of 10 April 2022, Canada has reported nearly 3.6 million cases and about 38,000 deaths,[402] while Mexico, which was overtaken in terms of the number of cases on 11 March 2022, the second anniversary of the day when the COVID-19 outbreak became a pandemic, by Japan, the second most affected country in East Asia, has reported about 5.7 million cases and about 320,000 deaths.[403] The state in the United States with the highest number of cases and the highest death toll is California, at about 9.1 million cases and nearly 90,000 deaths as of 10 April 2022.[404]United States

On 20 January, the first known case of COVID-19 was confirmed in the Pacific Northwest state of Washington in a man who had returned from Wuhan on 15 January.[405] On 31 January, the Trump administration declared a public health emergency,[406] and restricted entry for travellers from China who were not U.S. citizens.[407]

On 28 January 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—the leading public health institute of the U.S. government—announced they had developed their own testing kit.[408] Despite this, the United States had a slow start in testing, which obscured the extent of the outbreak.[409][410] Testing was marred by defective test kits produced by the government in February, a lack of federal approval for non-government test kits (by academia, companies, and hospitals) until the end of February, and restrictive criteria for people to qualify for a test.[409][410]

After the first death in the United States was reported in Washington state on 29 February,[411] Governor Jay Inslee declared a state of emergency,[412] an action soon followed by other states.[413][414] By mid-March, schools across the country were shutting down.[415]

On 6 March 2020, the United States was advised of projections for the impact of the new coronavirus on the country by a group of scientists at Imperial College London.[416] On the same day, President Trump signed the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, which provided $8.3 billion in emergency funding for federal agencies to respond to the outbreak.[417] Corporations encouraged employees to work from home.[418] Sports events and seasons were cancelled.[20]

On 11 and 12 March, Trump announced travel restrictions for most of Europe for 30 days,[419] including the United Kingdom and Ireland.[420] On 13 March, he declared a national emergency, which made federal funds available to respond to the crisis.[421] Beginning on 15 March, many businesses closed or reduced hours throughout the U.S. to try to reduce the spread of the virus.[422] By 17 March, the epidemic had been confirmed in all fifty states and in the District of Columbia.[423]On 26 March, the United States had more confirmed cases than any other country.[203] U.S. federal health inspectors surveyed 323 hospitals in late March; reporting "severe shortages" of test supplies, "widespread shortages" of personal protective equipment (PPE), and other strained resources due to extended patient stays while awaiting test results.[424]

As of 24 April[update], 889,309 cases have been confirmed in the United States, and 50,256 people have died.[425] On 30 March, Trump extended social distancing guidelines until 30 April.[426] On the same day, the USNS Comfort, a hospital ship with about a thousand beds, made anchor in New York.[427] On 3 April, the U.S. had a record 884 deaths due to the virus in a 24-hour period.[428] In the state of New York, cases exceeded 100,000 people on 3 April.[429]

The White House has been criticised for downplaying the threat and controlling the messaging by directing health officials and scientists to coordinate public statements and publications related to the virus with the office of Vice-President Mike Pence.[430] Some U.S. officials and commentators criticised U.S. reliance on importation of critical materials, including essential medical supplies, from China.[431][432]

On 14 April, President Trump halted funding to the World Health Organization, saying they had mismanaged the pandemic.[433] In late April, Trump said he would sign an executive order to temporarily suspend immigration to the United States because of the pandemic.[434] On 22 April, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said on Fox News that China had denied U.S. scientists permission to enter the country to ascertain the origin of the current pandemic, but did not give details of any requests for such visits.[435] On 22 April it was reported that two Californians had died from the virus (not, as previously thought, influenza) on 6 and 17 February, three weeks before the first official COVID-19 death in the U.S. had been acknowledged.[207]

South America

On 13 May 2020, it was reported that Latin America and the Caribbean had reported over 400,000 cases of COVID-19 infection with, 23,091 deaths. On 22 May 2020, citing the rapid increase of infections in Brazil, the WHO declared South America the epicentre of the pandemic.[438][439]

As of 12 January 2023, South America had recorded 67,331,547 confirmed cases and 1,344,031 deaths from COVID-19. Due to a shortage of testing and medical facilities, it is believed that the outbreak is far larger than the official numbers show.[440]Africa

The pandemic was confirmed to have spread to Africa on 14 February 2020, with the first confirmed case announced in Egypt.[441][442] The first confirmed case in sub-Saharan Africa was announced in Nigeria at the end of February 2020.[443] Within three months, the virus had spread throughout the continent, as Lesotho, the last African sovereign state to have remained free of the virus, reported a case on 13 May 2020.[444][445] By 26 May, it appeared that most African countries were experiencing community transmission, although testing capacity was limited.[446] Most of the identified imported cases arrived from Europe and the United States rather than from China where the virus originated.[447]

In early June 2021, Africa faced a third wave of COVID infections with cases rising in 14 countries.[448] By 4 July the continent recorded more than 251,000 new Covid cases, a 20% increase from the prior week and a 12% increase from the January peak. More than sixteen African countries, including Malawi and Senegal, recorded an uptick in new cases.[449] The World Health Organization labelled it Africa's 'Worst Pandemic Week Ever'.[450]Oceania

The COVID-19 pandemic was confirmed to have reached Oceania on 25 January 2020 with the first confirmed case reported in Melbourne, Australia.[452] The virus has spread to all sovereign states and territories in the region.[453] Australia and New Zealand were praised for their handling of the pandemic in comparison to other Western nations, with New Zealand and each state in Australia wiping out all community transmission of the virus several times even after re-introduction in the community.[454][455][456]

As a result of the high transmissibility of the Delta variant however, by August 2021, the Australian states of New South Wales and Victoria had conceded defeat in their eradication efforts.[457] In early October 2021, New Zealand also abandoned its elimination strategy.[458][459]International responses

Travel restrictions

As a result of the pandemic, many countries and regions imposed quarantines, entry bans, or other restrictions, either for citizens, recent travellers to affected areas,[460] or for all travellers.[461] Together with a decreased willingness to travel, this had a negative economic and social impact on the travel sector. Concerns have been raised over the effectiveness of travel restrictions to contain the spread of COVID-19.[462] A study in Science found that travel restrictions had only modest effects delaying the initial spread of COVID-19, unless combined with infection prevention and control measures to considerably reduce transmissions.[463] Researchers concluded that "travel restrictions are most useful in the early and late phase of an epidemic" and "restrictions of travel from Wuhan unfortunately came too late".[464]

The European Union rejected the idea of suspending the Schengen free travel zone and introducing border controls with Italy,[465][466] a decision which has been criticised by some European politicians.[467][468]

Evacuation of foreign citizens

Owing to the effective quarantine of public transport in Wuhan and Hubei, several countries evacuated their citizens and diplomatic staff from the area, primarily through chartered flights of the home nation, with Chinese authorities providing clearance. Canada, the United States, Japan, India, Sri Lanka, Australia, France, Argentina, Germany, and Thailand were among the first to plan the evacuation of their citizens.[469] Brazil and New Zealand also evacuated their own nationals and some other people.[470][471] On 14 March, South Africa repatriated 112 South Africans who tested negative for the virus from Wuhan, while four who showed symptoms were left behind to mitigate risk.[472] Pakistan said it would not evacuate citizens from China.[473]

On 15 February, the U.S. announced it would evacuate Americans aboard the cruise ship Diamond Princess,[474] and on 21 February, Canada evacuated 129 Canadian passengers from the ship.[475] In early March, the Indian government began evacuating its citizens from Iran.[476][477] On 20 March, the United States began to partially withdraw its troops from Iraq due to the pandemic.[478]

International aid

Aid to China

On 5 February, the Chinese foreign ministry said 21 countries (including Belarus, Pakistan, Trinidad and Tobago, Egypt, and Iran) had sent aid to China.[479] Some Chinese students at American universities joined together to help send aid to virus-stricken parts of China, with a joint group in the greater Chicago area reportedly managing to send 50,000 N95 masks to hospitals in the Hubei province on 30 January.[480]