Neoconservatism: Difference between revisions

one toss-off sentence from a blog --with zero evidence--is not a RS per BLP guidelines |

Reverted to revision 644941877 by Ubikwit (talk): Not a blog Consortium for Independent Journalism, and Robert Parry is notable. (TW) |

||

| Line 285: | Line 285: | ||

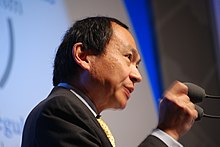

[[File:Francis Fukuyama.jpg|thumb|Francis Fukuyama]] |

[[File:Francis Fukuyama.jpg|thumb|Francis Fukuyama]] |

||

* [[Robert Kagan]] – Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, Historian, founder of the ''[[The Politic|Yale Political Monthly]]'', adviser to Republican political campaigns.<ref name=nytimes-kagan>{{citation |title=Events in Iraq Open Door for Interventionist Revival, Historian Says |first=Jason |last=Horowitz |work=New York Times |date=15 June 2014 |accessdate=9 October 2014 |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/16/us/politics/historians-critique-of-obama-foreign-policy-is-brought-alive-by-events-in-iraq.html}}</ref> |

* [[Robert Kagan]] – Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, Historian, founder of the ''[[The Politic|Yale Political Monthly]]'', adviser to Republican political campaigns.<ref name=nytimes-kagan>{{citation |title=Events in Iraq Open Door for Interventionist Revival, Historian Says |first=Jason |last=Horowitz |work=New York Times |date=15 June 2014 |accessdate=9 October 2014 |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/16/us/politics/historians-critique-of-obama-foreign-policy-is-brought-alive-by-events-in-iraq.html}}</ref> |

||

* [[Frederick Kagan]] Assistant professor of military history at West Point from 1995–2001 and as an Associate professor of military history from 2001–2005 <ref>[https://consortiumnews.com/2014/02/23/neocons-and-the-ukraine-coup/ Neocons and the Ukraine Coup, Robert Parry,February 23, 2014]</ref> |

|||

* [[Francis Fukuyama]] (former neoconservative) – Senior Fellow at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at Stanford, former-neoconservative, political scientist, political economist, and author. |

* [[Francis Fukuyama]] (former neoconservative) – Senior Fellow at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at Stanford, former-neoconservative, political scientist, political economist, and author. |

||

* [[Victor Davis Hanson]] – Martin and Illie Anderson Senior Fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, columnist and author. |

* [[Victor Davis Hanson]] – Martin and Illie Anderson Senior Fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, columnist and author. |

||

Revision as of 06:18, 31 January 2015

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Neoconservatism is a political movement born in the United States during the 1960s. Many of its adherents rose to political fame during the Republican presidential administrations of the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. Neoconservatives peaked in influence during the presidency of George W. Bush, when they played a major role in promoting and planning the invasion of Iraq.[1] Prominent neoconservatives in the Bush administration included Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz, John Bolton, Elliott Abrams, Richard Perle, and Paul Bremer.

The term "neoconservative" refers to those who made the ideological journey from the anti-Stalinist left to the camp of American conservatism.[2] Neoconservatives frequently advocate the "assertive" promotion of democracy and promotion of "American national interest" in international affairs including by means of military force.[3][4] The movement had its intellectual roots in the Jewish[5] monthly review magazine Commentary.[6][7] C. Bradley Thompson, a professor at Clemson University, claims that most influential neoconservatives refer explicitly to the theoretical ideas in the philosophy of Leo Strauss (1899–1973).[8]

Terminology

The term "neoconservative" was popularized in the United States during 1973 by Socialist leader Michael Harrington, who used the term to define Daniel Bell, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and Irving Kristol, whose ideologies differed from Harrington's.[9]

The "neoconservative" label was used by Irving Kristol in his 1979 article "Confessions of a True, Self-Confessed 'Neoconservative.'"[10] His ideas have been influential since the 1950s, when he co-founded and edited the magazine Encounter.[11] Another source was Norman Podhoretz, editor of the magazine Commentary from 1960 to 1995. By 1982 Podhoretz was terming himself a neoconservative, in a New York Times Magazine article titled "The Neoconservative Anguish over Reagan's Foreign Policy".[12][13] During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the neoconservatives considered that liberalism had failed and "no longer knew what it was talking about," according to E. J. Dionne.[14]

The term "neoconservative", which was used originally by a socialist to criticize the politics of Social Democrats, USA,[15] has since 1980 been used as a criticism against proponents of American modern liberalism who had become slightly more conservative.[10][16]

The term "neoconservative" was the subject of increased media coverage during the presidency of George W. Bush,[17][18] with particular emphasis on a perceived neoconservative influence on American foreign policy, as part of the Bush Doctrine.[19]

History

Through the 1950s and early 1960s, the future neoconservatives had endorsed the American Civil Rights Movement, racial integration, and Martin Luther King, Jr.[20] From the 1950s to the 1960s, there was general endorsement among liberals for military action to prevent a communist victory in Vietnam.[21]

Neoconservatism was initiated by the repudiation of coalition politics by the American New Left: Black Power, which denounced coalition-politics and racial integration as "selling out" and "Uncle Tomism" and which frequently generated anti-semitic slogans; "anti-anticommunism", which seemed indifferent to the fate of South Vietnam, and which during the late 1960s included substantial endorsement of Marxist-Leninist politics; and the "new politics" of the New left, which considered students and alienated minorities as the main agents of social change (replacing the majority of the population and labor activists, who nevertheless established close personal links with anti-Imperialist guerrillas and revolutionary organizations throughout the colonized world).[22] Irving Kristol edited the journal The Public Interest (1965–2005), featuring economists and political scientists, which emphasized ways that government planning in the liberal state had produced unintended harmful consequences.[23] Interestingly enough, many early Neoconservative political figures were disillusioned Democratic politicians and intellectuals, such as Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who served in the Nixon Administration, and Jeane Kirkpatrick, who served as President Ronald Reagan's UN Ambassador.

Norman Podhoretz's magazine Commentary of the American Jewish Committee, originally a journal of liberalism, became a major publication for neoconservatives during the 1970s. Commentary published an article by Jeane Kirkpatrick, an early and prototypical neoconservative, albeit not a New Yorker.

Jeane Kirkpatrick

A theory of neoconservative foreign policy during the final years of the Cold War was articulated by Jeane Kirkpatrick, in "Dictatorships and Double Standards,"[24] published in Commentary Magazine during November 1979. Kirkpatrick criticized the foreign policy of Jimmy Carter, which endorsed detente with the USSR. She later served the Reagan Administration as Ambassador to the United Nations.[25]

Skepticism towards democracy promotion

In "Dictatorships and Double Standards," Kirkpatrick distinguished between authoritarian regimes and the totalitarian regimes such as the Soviet Union; she suggested that in some countries democracy was not tenable and the U.S. had a choice between endorsing authoritarian governments, which might evolve into democracies, or Marxist–Leninist regimes, which she argued had never been ended once they achieved totalitarian control. In such tragic circumstances, she argued that allying with authoritarian governments might be prudent. Kirkpatrick argued that by demanding rapid liberalization in traditionally autocratic countries, the Carter administration had delivered those countries to Marxist-Leninists that were even more repressive. She further accused the Carter administration of a "double standard," of never having applied its rhetoric on the necessity of liberalization to communist governments. The essay compares traditional autocracies and Communist regimes:

[Traditional autocrats] do not disturb the habitual rhythms of work and leisure, habitual places of residence, habitual patterns of family and personal relations. Because the miseries of traditional life are familiar, they are bearable to ordinary people who, growing up in the society, learn to cope ...

[Revolutionary Communist regimes] claim jurisdiction over the whole life of the society and make demands for change that so violate internalized values and habits that inhabitants flee by the tens of thousands ...

Kirkpatrick concluded that while the United States should encourage liberalization and democracy in autocratic countries, it should not do so when the government risks violent overthrow, and should expect gradual change rather than immediate transformation.[26] She wrote: “No idea holds greater sway in the mind of educated Americans than the belief that it is possible to democratize governments, anytime and anywhere, under any circumstances... Decades, if not centuries, are normally required for people to acquire the necessary disciplines and habits. In Britain, the road [to democratic government] took seven centuries to traverse. ... The speed with which armies collapse, bureaucracies abdicate, and social structures dissolve once the autocrat is removed frequently surprises American policymakers."[27]

- Poland

Before 1982, neoconservatives were skeptical about democracy promotion and criticized the prudence of the Carter administrations policies on human rights. Kirkpatrick and Norman Podhoretz before 1982 argued that communism could not be overthrown and that the Polish labor-union Solidarity was doomed. Podhoretz and Kirkpatrick were originally skeptical about the AFL-CIO's endorsement of Solidarity and about the use of U.S. economic aid to promote liberalization and democratization in Poland.[28][29]

New York Intellectuals

Many neoconservatives had been leftist during the 1930s and 1940s, when they opposed Stalinism. After World War II, they continued to oppose Stalinism and to endorse democracy during the Cold War. Of these, many were from the Jewish[30] intellectual milieu of New York City.[31]

Rejecting the American New Left and McGovern's New Politics

As the policies of the New Left made the Democrats increasingly leftist, these intellectuals became disillusioned with President Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society domestic programs. The influential 1970 bestseller The Real Majority by Ben Wattenberg expressed that the "real majority" of the electorate endorsed economic liberalism but also social conservatism, and warned Democrats it could be disastrous to adopt liberal positions on certain social and crime issues.[32]

The neoconservatives rejected the counterculture New Left, and what they considered anti-Americanism in the non-interventionism of the activism against the Vietnam War. After the anti-war faction took control of the party during 1972 and nominated George McGovern, the Democrats among them endorsed Washington Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson instead for his unsuccessful 1972 and 1976 campaigns for president. Among those who worked for Jackson were future neoconservatives Paul Wolfowitz, Doug Feith, and Richard Perle.[33] During the late 1970s, neoconservatives tended to endorse Ronald Reagan, the Republican who promised to confront Soviet expansionism. Neocons organized in the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation to counter the liberal establishment.[34]

In another (2004) article, Michael Lind also wrote [35]

Neoconservatism... originated in the 1970s as a movement of anti-Soviet liberals and social democrats in the tradition of Truman, Kennedy, Johnson, Humphrey and Henry ('Scoop') Jackson, many of whom preferred to call themselves 'paleoliberals.' [After the end of the Cold War]... many 'paleoliberals' drifted back to the Democratic center... Today's neocons are a shrunken remnant of the original broad neocon coalition. Nevertheless, the origins of their ideology on the left are still apparent. The fact that most of the younger neocons were never on the left is irrelevant; they are the intellectual (and, in the case of William Kristol and John Podhoretz, the literal) heirs of older ex-leftists.

Leo Strauss and his students

Neoconservatism draws on several intellectual traditions. The students of political science Professor Leo Strauss (1899–1973) comprised one major group. Eugene Sheppard notes that, "Much scholarship tends to understand Strauss as an inspirational founder of American neoconservatism."[36] Strauss was a refugee from Nazi Germany who taught at the New School for Social Research in New York (1939–49) and the University of Chicago (1949–1958).[37]

Strauss asserted that "the crisis of the West consists in the West's having become uncertain of its purpose." His solution was a restoration of the vital ideas and faith that in the past had sustained the moral purpose of the West.[dubious ] Classical Greek political philosophy and the Judeo-Christian heritage are the essentials of the Great Tradition in Strauss's work.[38] Strauss emphasized the spirit of the Greek classics, and West (1991) argues that for Strauss the American "Founding Fathers" were correct in their understanding of the classics in their principles of justice. For Strauss, political community is defined by convictions about justice and happiness rather than by sovereignty and force. He repudiated the philosophy of John Locke as a bridge to 20th-century historicism and nihilism, and defended liberal democracy as closer to the spirit of the classics than other modern regimes.[citation needed] For Strauss, the American awareness of ineradicable evil in human nature, and hence the need for morality, was a beneficial outgrowth of the premodern Western tradition.[39] O'Neill (2009) notes that Strauss wrote little about American topics but his students wrote a great deal, and that Strauss's influence caused his students to reject historicism and positivism. Instead they promoted a so-called Aristotelian perspective on America that produced a qualified defense of its liberal constitutionalism.[40] Strauss influenced Weekly Standard editor William Kristol, editor John Podhoretz, and military strategist Paul Wolfowitz.[41][42]

1990s

During the 1990s, neoconservatives were once again opposed to the foreign policy establishment, both during the Republican Administration of President George H. W. Bush and that of his Democratic successor, President William Clinton. Many critics charged that the neoconservatives lost their influence as a result of the end of the USSR.[43]

After the decision of George H. W. Bush to leave Saddam Hussein in power after the first Iraq War during 1991, many neoconservatives considered this policy, and the decision not to endorse indigenous dissident groups such as the Kurds and Shiites in their 1991-1992 resistance to Hussein, as a betrayal of democratic principles.[44][45][46][47][48]

Ironically, some of those same targets of criticism would later become fierce advocates of neoconservative policies. During 1992, referring to the first Iraq War, then United States Secretary of Defense and future Vice President Richard Cheney said:

I would guess if we had gone in there, I would still have forces in Baghdad today. We'd be running the country. We would not have been able to get everybody out and bring everybody home.... And the question in my mind is how many additional American casualties is Saddam [Hussein] worth? And the answer is not that damned many. So, I think we got it right, both when we decided to expel him from Kuwait, but also when the president made the decision that we'd achieved our objectives and we were not going to go get bogged down in the problems of trying to take over and govern Iraq.[49]

Within a few years of the Gulf War in Iraq, many neoconservatives were endorsing the ouster of Saddam Hussein. On February 19, 1998, an open letter to President Clinton was published, signed by dozens of pundits, many identified with neoconservatism and, later, related groups such as the PNAC, urging decisive action to remove Saddam from power.[50]

Neoconservatives were also members of the so-called "blue team", which argued for a confrontational policy toward the People's Republic of China and strong military and diplomatic endorsement for the Republic of China (also known as Formosa or Taiwan).

During the late 1990s, Irving Kristol and other writers in neoconservative magazines began touting anti-Darwinist views, as an endorsement of intelligent design. Since these neoconservatives were largely of secular origin, a few commentators have speculated that this – along with endorsement of religion generally – may have been a case of a "noble lie", intended to protect public morality, or even tactical politics, to attract religious endorsers.[51]

2000s

Administration of George W. Bush

The Bush campaign and the early Bush administration did not exhibit strong endorsement of neoconservative principles. As a presidential candidate, Bush had argued for a restrained foreign policy, stating his opposition to the idea of nation-building[52] and an early foreign policy confrontation with China was managed without the vociferousness suggested by some neoconservatives.[53] Also early in the administration, some neoconservatives criticized Bush's administration as insufficiently supportive of Israel, and suggested Bush's foreign policies were not substantially different from those of President Clinton.[54]

Bush's policies changed dramatically immediately after the September 11, 2001, attacks.

During Bush's State of the Union speech of January 2002, he named Iraq, Iran, and North Korea as states that "constitute an axis of evil" and "pose a grave and growing danger". Bush suggested the possibility of preemptive war: "I will not wait on events, while dangers gather. I will not stand by, as peril draws closer and closer. The United States of America will not permit the world's most dangerous regimes to threaten us with the world's most destructive weapons."[56][57]

Some major defense and national-security persons have been quite critical of what they believed was neoconservative influence in getting the United States to war with Iraq.[58]

Former Nebraska Republican U.S. senator and incumbent Secretary of Defense, Chuck Hagel, who has been critical of the Bush administration's adoption of neoconservative ideology, in his book America: Our Next Chapter wrote:

So why did we invade Iraq? I believe it was the triumph of the so-called neo-conservative ideology, as well as Bush administration arrogance and incompetence that took America into this war of choice. . . . They obviously made a convincing case to a president with very limited national security and foreign policy experience, who keenly felt the burden of leading the nation in the wake of the deadliest terrorist attack ever on American soil.

Bush Doctrine

The Bush Doctrine of preemptive war was stated explicitly in the National Security Council text "National Security Strategy of the United States," published September 20, 2002: "We must deter and defend against the threat before it is unleashed ... even if uncertainty remains as to the time and place of the enemy's attack. ... The United States will, if necessary, act preemptively."[59]

The choice not to use the word 'preventive' in the 2002 National Security Strategy, and instead use the word 'preemptive' was largely in anticipation of the widely perceived illegality of preventive attacks in international law, via both Charter Law and Customary Law.[60]

Policy analysts noted that the Bush Doctrine as stated in the 2002 NSC document had a strong resemblance to recommendations presented originally in a controversial Defense Planning Guidance draft written during 1992 by Paul Wolfowitz, during the first Bush administration.[61]

The Bush Doctrine was greeted with accolades by many neoconservatives. When asked whether he agreed with the Bush Doctrine, Max Boot said he did, and that "I think [Bush is] exactly right to say we can't sit back and wait for the next terrorist strike on Manhattan. We have to go out and stop the terrorists overseas. We have to play the role of the global policeman. ... But I also argue that we ought to go further."[62] Discussing the significance of the Bush Doctrine, neoconservative writer William Kristol claimed: "The world is a mess. And, I think, it's very much to Bush's credit that he's gotten serious about dealing with it. ... The danger is not that we're going to do too much. The danger is that we're going to do too little."[63]

2008 Presidential election and aftermath

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2008) |

John McCain, who was the Republican candidate for the 2008 United States Presidential election, endorsed continuing the second Iraq War, "the issue that is most clearly identified with the neoconservatives". The New York Times reported further that his foreign policy views combined elements of neoconservatism and the main competing conservative opinion, pragmatism, also known as realism:[64]

Among [McCain's advisers] are several prominent neoconservatives, including Robert Kagan ... Max Boot ... John R. Bolton ... [and] Randy Scheunemann. 'It may be too strong a term to say a fight is going on over John McCain’s soul,' said Lawrence Eagleburger ... who is a member of the pragmatist camp, ... [but he] said, "there is no question that a lot of my far right friends have now decided that since you can't beat him, let's persuade him to slide over as best we can on these critical issues.

Barack Obama campaigned for the Democratic nomination during 2008 by attacking his opponents, especially Hillary Clinton, for originally endorsing Bush's Iraq-war policies. He gave the impression he would reverse such policies. However, Obama adopted the main parts of the Bush policy for Iraq, naming Clinton to the State Department and keeping Robert Gates (Bush's Defense Secretary), and David Petraeus (Bush's ranking general in Iraq), as well as implementing the "surge" of military force. By 2010, U.S. forces had switched from combat to a training role in Iraq and they left in 2011.[65]

Evolution of opinions

Usage and general views

During the early 1970s, Socialist Michael Harrington was one of the first to use "neoconservative" in its modern meaning. He characterized neoconservatives as former leftists – whom he derided as "socialists for Nixon" – who had become more conservative.[9] These people tended to remain endorsers of social democracy, but distinguished themselves by allying with the Nixon administration with respect to foreign policy, especially by their endorsement of the Vietnam War and opposition to the USSR. They still endorsed the welfare state, but not necessarily in its contemporary form.

Irving Kristol remarked that a neoconservative is a "liberal mugged by reality", one who became more conservative after seeing the results of liberal policies. Kristol also distinguished three specific aspects of neoconservatism from previous types of conservatism: neo-conservatives had a forward-looking attitude from their liberal heritage, rather than the reactionary and dour attitude of previous conservatives; they had a meliorative attitude, proposing alternate reforms rather than simply attacking social liberal reforms; they took philosophical ideas and ideologies very seriously.[66]

During January 2009, at the end of President George W. Bush's second term in office, Jonathan Clarke, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, proposed the following as the "main characteristics of neoconservatism": "a tendency to see the world in binary good/evil terms", a "low tolerance for diplomacy", a "readiness to use military force", an "emphasis on US unilateral action", a "disdain for multilateral organizations" and a "focus on the Middle East".[67]

Opinions concerning foreign policy

| International relations theory |

|---|

|

|

In foreign policy, the neoconservatives' main concern is to prevent the development of a new rival. Defense Planning Guidance, a document prepared during 1992 by Under Secretary for Defense for Policy Paul Wolfowitz, is regarded by Distinguished Professor of the Humanities John McGowan at the University of North Carolina as the "quintessential statement of neoconservative thought". The report says:[68]

"Our first objective is to prevent the re-emergence of a new rival, either on the territory of the former Soviet Union or elsewhere, that poses a threat on the order of that posed formerly by the Soviet Union. This is a dominant consideration underlying the new regional defense strategy and requires that we endeavor to prevent any hostile power from dominating a region whose resources would, under consolidated control, be sufficient to generate global power."

According to Lead Editor of e-International Relations, Stephen McGlinchey, "Neo-conservatism is something of a chimera in modern politics. For its opponents it is a distinct political ideology that emphasizes the blending of military power with Wilsonian idealism, yet for its supporters it is more of a 'persuasion' that individuals of many types drift into and out of. Regardless of which is more correct, it is now widely accepted that the neo-conservative impulse has been visible in modern American foreign policy and that it has left a distinct impact".[69]

Neoconservatives claim the "conviction that communism was a monstrous evil and a potent danger."[70] They endorse social welfare programs that were rejected by libertarians and paleoconservatives.[citation needed]

Neoconservatism first developed during the late 1960s as an effort to oppose the radical cultural changes occurring within the United States. Irving Kristol wrote: "If there is any one thing that neoconservatives are unanimous about, it is their dislike of the counterculture."[71] Norman Podhoretz agreed: "Revulsion against the counterculture accounted for more converts to neoconservatism than any other single factor."[72] Neoconservatives began to emphasize foreign issues during the mid-1970s.[73]

During 1979 an early study by liberal Peter Steinfels concentrated on the ideas of Irving Kristol, Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Daniel Bell. He noted that the stress on foreign affairs "emerged after the New Left and the counterculture had dissolved as convincing foils for neoconservatism .... The essential source of their anxiety is not military or geopolitical or to be found overseas at all; it is domestic and cultural and ideological."[74]

Neoconservative foreign policy is a descendant of so-called Wilsonian idealism. Neoconservatives endorse democracy promotion by the U.S. and other democracies, based on the claim that they think that human rights belong to everyone. They criticized the United Nations and detente with the USSR. On domestic policy, they endorse a welfare state, like European and Canadian conservatives and unlike American conservatives. According to Norman Podhoretz,

"the neo-conservatives dissociated themselves from the wholesale opposition to the welfare state which had marked American conservatism since the days of the New Deal" and . . . while neoconservatives supported "setting certain limits" to the welfare state, those limits did not involve "issues of principle, such as the legitimate size and role of the central government in the American constitutional order" but were to be "determined by practical considerations."[75]

Democracy promotion is allegedly derived from a belief that freedom is a universal human right and by opinion polls showing majority support for democracy in countries with authoritarian regimes. Democracy promotion is said to have another benefit, in that democracy and responsive government are expected to reduce the appeal of Islamism. Neoconservatives have cited political scientists[citation needed] who have argued that democratic regimes are less likely to start wars. Further, they argue that the lack of freedoms, lack of economic opportunities, and the lack of secular general education in authoritarian regimes promotes radicalism and extremism. Consequently, neoconservatives advocate democracy promotion to regions of the world where it currently does not prevail, notably the Arab nations, Iran, communist China and North Korea.

During April 2006 Robert Kagan wrote in The Washington Post that Russia and China may be the greatest "challenge liberalism faces today":

"The main protagonists on the side of autocracy will not be the petty dictatorships of the Middle East theoretically targeted by the Bush doctrine. They will be the two great autocratic powers, China and Russia, which pose an old challenge not envisioned within the new "war on terror" paradigm. ... Their reactions to the "color revolutions" in Ukraine, Georgia and Kyrgyzstan were hostile and suspicious, and understandably so. ... Might not the successful liberalization of Ukraine, urged and supported by the Western democracies, be but the prelude to the incorporation of that nation into NATO and the European Union—in short, the expansion of Western liberal hegemony?"[76][77]

During July 2008 Joe Klein wrote in Time that today's neoconservatives are more interested in confronting enemies than in cultivating friends. He questioned the sincerity of neoconservative interest in exporting democracy and freedom, saying, "Neoconservatism in foreign policy is best described as unilateral bellicosity cloaked in the utopian rhetoric of freedom and democracy."[78]

During February 2009 Andrew Sullivan wrote he no longer took neoconservatism seriously because its basic tenet was defense of Israel:[79]

The closer you examine it, the clearer it is that neoconservatism, in large part, is simply about enabling the most irredentist elements in Israel and sustaining a permanent war against anyone or any country who disagrees with the Israeli right. That's the conclusion I've been forced to these last few years. And to insist that America adopt exactly the same constant-war-as-survival that Israelis have been slowly forced into... But America is not Israel. And once that distinction is made, much of the neoconservative ideology collapses.

Neoconservatives respond to charges of merely rationalizing aid for Israel by noting that their "position on the Middle East conflict was exactly congruous with the neoconservative position on conflicts everywhere else in the world, including places where neither Jews nor Israeli interests could be found—not to mention the fact that non-Jewish neoconservatives took the same stands on all of the issues as did their Jewish confrères."[80]

Views on economics

While neoconservatism is concerned primarily with foreign policy, there is also some discussion of internal economic policies. Neoconservatism generally endorses free markets and capitalism, favoring supply-side economics, but it has several disagreements with classical liberalism and fiscal conservatism: Irving Kristol states that neocons are more relaxed about budget deficits and tend to reject the Hayekian notion that the growth of government influence on society and public welfare is "the road to serfdom."[81] Indeed, to safeguard democracy, government intervention and budget deficits may sometimes be necessary, Kristol argues.

Further, neoconservative ideology stresses that while free markets do provide material goods in an efficient way, they lack the moral guidance human beings need to fulfill their needs. Morality can be found only in tradition, they say and, contrary to libertarianism, markets do pose questions that cannot be solved solely by economics. "So, as the economy only makes up part of our lives, it must not be allowed to take over and entirely dictate to our society."[82] Critics consider neoconservatism a bellicose and "heroic" ideology opposed to "mercantile" and "bourgeois" virtues and therefore "a variant of anti-economic thought."[83] Political scientist Zeev Sternhell states, "Neoconservatism has succeeded in convincing the great majority of Americans that the main questions that concern a society are not economic, and that social questions are really moral questions."[84]

Distinctions from other conservatives

Some influential members of early neoconservatism, such as Elliot Abrams, were originally members of the Democratic Party, and as such advocated for "cold war liberalism".[85][86] But since the election of Ronald Reagan during 1980—in some cases even before that—they have been in electoral alignment with the Republican Party and have served in the same presidential administrations. While they have often ignored ideological differences in alliance against relative leftists, neoconservatives differ from paleoconservatives. In particular, they disagree with nativism, protectionism, and non-interventionism in foreign policy, ideologies that are traditionally American but have been strongly disfavored by the elite and intellectuals since World War II [dubious ]. Compared with traditionalist conservatism and libertarianism, which may be non-interventionist, neoconservatism emphasizes confrontation, challenging regimes hostile to the alleged values and interests of the United States.[citation needed] Neoconservatives also believe in democratic peace theory, the proposition that democracies never or almost never war with one another.

Criticism of terminology

Some of those identified as neoconservative reject the term, arguing that it lacks a coherent definition, or that it was coherent only in the context of the Cold War. For example, conservative writer David Horowitz argues that the increasing use of the term neoconservative since the 2003 start of the Iraq War has made it irrelevant:[citation needed]

Neo-conservatism is a term almost exclusively used by the enemies of America's liberation of Iraq. There is no 'neo-conservative' movement in the United States. When there was one, it was made up of former Democrats who embraced the welfare state but supported Ronald Reagan's Cold War policies against the Soviet bloc. Today 'neo-conservatism' identifies those who believe in an aggressive policy against radical Islam and the global terrorists.

The term may have lost meaning due to excessive and inconsistent usage. For example, Richard Cheney, Condoleezza Rice, and Donald Rumsfeld have been identified[by whom?] as neoconservatives despite the fact that they have been lifelong Republicans (though Cheney and Rice have endorsed Irving Kristol's ideas) and differ from most neoconservatives on some issues.[citation needed]

Some critics reject the idea that there is a neoconservatism separate from traditional American conservatism; some traditional conservatives are skeptical of the contemporary usage of the term and dislike being associated with its stereotypes or supposed agendas. For example, columnist David Harsanyi wrote, "These days, it seems that even temperate support for military action against dictators and terrorists qualifies you a neocon."[87] Jonah Goldberg rejected the term as trite and over-used, arguing, "There's nothing 'neo' about me: I was never anything other than conservative."[citation needed]

Allegations of antisemitism

Some writers and intellectuals have argued that criticism of neoconservatism is often a euphemism for criticism of Jews, and that the term has been adopted by independents and the political left to stigmatize endorsement of Israel. In The Chronicle of Higher Education, Robert J. Lieber wrote that writers such as Michael Lind, Eric Alterman and Pat Buchanan have created a theory that identified neoconservative Paul Wolfowitz as the center of a conspiracy involving the manipulation of the Presidency of George W. Bush to gain control of the US military and make war on Iraq in the interest of Israel rather than the US.[88]

Joe Klein, in Time magazine, has suggested it is legitimate to examine the religion of neoconservatives. He does not say there was a conspiracy but says there is a case to be made for disproportionate influence of Jewish neoconservatives on US foreign policy, and that several of them endorsed the Iraq war because of Israel's interests, though sometimes in an unconscious contradiction to American interests:

I do believe that there is a group of people who got involved and had a disproportionate influence on U.S. foreign policy. There were people out there in the Jewish community who saw this as a way to create a benign domino theory and eliminate all of Israel's enemies.... I think it represents a really dangerous anachronistic neocolonial sensibility. And I think it is a very, very dangerous form of extremism. I think it's bad for Israel and it's bad for America. And these guys have been getting a free ride. And now these people are backing the notion of a war with Iran and not all of them, but some of them, are doing it because they believe that Iran is an existential threat to Israel.[89]

David Brooks derided the "fantasies" of "full-mooners fixated on a... sort of Yiddish Trilateral Commission", beliefs which had "hardened into common knowledge... In truth, people labeled neocons (con is short for 'conservative' and neo is short for 'Jewish') travel in widely different circles..."[90] Barry Rubin argued that the neoconservative label is used as an antisemitic pejorative:[91]

First, 'neo-conservative' is a codeword for Jewish. As antisemites did with big business moguls in the nineteenth century and Communist leaders in the twentieth, the trick here is to take all those involved in some aspect of public life and single out those who are Jewish. The implication made is that this is a Jewish-led movement conducted not in the interests of all the, in this case, American people, but to the benefit of Jews, and in this case Israel.

Trotskyism allegation

Trotskyism is the type of communism advocated by Leon Trotsky and his followers, emphasizing orthodox Marxist concepts of workers' power in opposition to state bureaucracy, and international proletarian revolution, while critical of Stalinism and the USSR. Critics of neo-conservatism have charged that neo-conservatism is descended from Trotskyism, and that Trotskyist traits continue to characterize ideologies and practices of neo-conservatism. During the Reagan Administration, the charge was made that the foreign policy of the Reagan administration was being managed by Trotskyists.[citation needed] This claim was called a "myth" by Lipset (1988, p. 34):[92] This "Trotskyist" charge has been repeated and even widened by journalist Michael Lind during 2003 to assert a takeover of the foreign policy of the George W. Bush administration by former Trotskyists;[93] Lind's "amalgamation of the defense intellectuals with the traditions and theories of 'the largely Jewish-American Trotskyist movement' [in Lind's words]" was criticized during 2003 by University of Michigan professor Alan M. Wald,[94] who had discussed Trotskyism in his history of "the New York intellectuals".[95][96]

The charge that neoconservativism is related to Leninism has been made, also. Francis Fukuyama identified neoconservatism with Leninism during 2006.[18] He wrote that neoconservatives:

…believed that history can be pushed along with the right application of power and will. Leninism was a tragedy in its Bolshevik version, and it has returned as farce when practiced by the United States. Neoconservatism, as both a political symbol and a body of thought, has evolved into something I can no longer support.[18]

Criticisms

The term neoconservative may be used pejoratively by self-described paleoconservatives, Democrats, liberals, progressives, or libertarians.

Critics take issue with neoconservatives' support for aggressive foreign policy. Critics from the left take issue with what they characterize as unilateralism and lack of concern with international consensus through organizations such as the United Nations.[97][98][99]

Neoconservatives respond by describing their shared opinion as a belief that national security is best attained by actively promoting freedom and democracy abroad as in the democratic peace theory through the endorsement of democracy, foreign aid and in certain cases military intervention. This is different from the traditional conservative tendency to endorse friendly regimes in matters of trade and anti-communism even at the expense of undermining existing democratic systems.

Republican Congressman Ron Paul has been a longtime critic of neoconservativism as an attack on freedom and the U.S. Constitution, including an extensive speech on the House floor addressing neoconservative beginnings and how neoconservatism is neither new nor conservative.

Paul Krugman in a column named 'Years Of Shame' commemorating the tenth anniversary of 9/11 attacks, criticized the Neoconservatives for causing a war unrelated to 9/11 attacks and fought for wrong reasons.[100]

Imperialism and secrecy

John McGowan, professor of humanities at the University of North Carolina, states, after an extensive review of neoconservative literature and theory, that neoconservatives are attempting to build an American Empire, seen as successor to the British Empire, its goal being to perpetuate a Pax Americana. As imperialism is largely considered unacceptable by the American media, neoconservatives do not articulate their ideas and goals in a frank manner in public discourse. McGowan states,[68]

Frank neoconservatives like Robert Kaplan and Niall Ferguson recognize that they are proposing imperialism as the alternative to liberal internationalism. Yet both Kaplan and Ferguson also understand that imperialism runs so counter to American's liberal tradition that it must... remain a foreign policy that dare not speak its name... While Ferguson, the Brit, laments that Americans cannot just openly shoulder the white man's burden, Kaplan the American, tells us that "only through stealth and anxious foresight" can the United States continue to pursue the "imperial reality [that] already dominates our foreign policy", but must be disavowed in light of "our anti-imperial traditions, and... the fact that imperialism is delegitimized in public discourse"... The Bush administration, justifying all of its actions by an appeal to "national security", has kept as many of those actions as it can secret and has scorned all limitations to executive power by other branches of government or international law.

Friction with moderate conservatives

Many moderate conservatives oppose neoconservative policies and have sharply negative views on it. For example, Stefan Halper and Jonathan Clarke (a libertarian based at CATO), in their 2004 book on neoconservatism, “America Alone: The Neo-Conservatives and the Global Order",[101] characterized the neoconservatives, at that time, as uniting:

… around three common themes:

- A belief deriving from religious conviction that the human condition is defined as a choice between good and evil and that the true measure of political character is to be found in the willingness by the former (themselves) to confront the latter.

- An assertion that the fundamental determinant of the relationship between states rests on military power and the willingness to use it.

- A primary focus on the Middle East and global Islam as the principal theater for American overseas interests.

In putting these themes into practice, neo-conservatives:

- Analyze international issues in black-and-white, absolute moral categories. They are fortified by a conviction that they alone hold the moral high ground and argue that disagreement is tantamount to defeatism.

- Focus on the "unipolar" power of the United States, seeing the use of military force as the first, not the last, option of foreign policy. They repudiate the "lessons of Vietnam," which they interpret as undermining American will toward the use of force, and embrace the "lessons of Munich," interpreted as establishing the virtues of preemptive military action.

- Disdain conventional diplomatic agencies such as the State Department and conventional country-specific, realist, and pragmatic, analysis. They are hostile toward nonmilitary multilateral institutions and instinctively antagonistic toward international treaties and agreements. "Global unilateralism" is their watchword. They are fortified by international criticism, believing that it confirms American virtue.

- Look to the Reagan administration as the exemplar of all these virtues and seek to establish their version of Reagan's legacy as the Republican and national orthodoxy.[101]: 10–11

Friction with paleoconservatism

Starting during the 1980s, disputes concerning Israel and public policy contributed to a conflict with paleoconservatives, who argue that neoconservatives are an illegitimate addition to conservatism. For example, Pat Buchanan terms neoconservatism "a globalist, interventionist, open borders ideology."[102] The dispute is often traced back to a 1981 disagreement over Ronald Reagan's nomination of Mel Bradford, a Southerner, to manage the National Endowment for the Humanities. Bradford withdrew after neoconservatives complained that he had criticized Abraham Lincoln; the paleoconservatives had endorsed Bradford.

Neoconservatism in other countries

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2011) |

Neoconservatism has been influential in other countries. Variants of it can be found in the United Kingdom, the Czech Republic, Azerbaijan[103] and Japan

Notable people associated with neoconservatism

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

The list includes public people identified as personally neoconservative at an important time or a high official with numerous neoconservative advisers, such as George W. Bush and Richard Cheney. Some are dead, or are ex-neoconservatives.

Politicians

Government officials

Academics

Public intellectuals

|

Related publications and institutions

See also

- Factions in the Republican Party (United States)

- Globalization

- Neoconservatism and paleoconservatism

- Neoconservatism in Japan

- New Right

- Paleoconservatism

- Project for a New American Century

- Trotskyism

Notes

- ^ Jeffrey Record (2010). Wanting War: Why the Bush Administration Invaded Iraq. Potomac Books, Inc. pp. 47–50.

- ^ Gertrude Himmelfarb (2011). The Neoconservative Persuasion: Selected Essays, 1942-2009. p. 140, last line and p 141.

- ^ [1] Britannica – Academic Edition. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ [2]www.merriam-webster.com/. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ New York Times Adding More Jewish Voices to the Discussion "The Jewish monthly Commentary..."

- ^ Gal Beckerman, in « The Neoconservatism Persuasion », The Forward, January 6th, 2006.

- ^ Friedman, Murray (2005). The Neoconservative Revolution Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Neoconservatism Unmasked". Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Harrington, Michael (Fall 1973). "The Welfare State and Its Neoconservative Critics". Dissent. 20.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Cited in: Isserman, Maurice (2000). The Other American: the life of Michael Harrington. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-891620-30-4....reprinted as chapter 11 in Harrington's 1976 book The Twilight of Capitalism, pp. 165–272. Earlier during 1973 he had described some of the same ideas in a brief contribution to a symposium on welfare sponsored by Commentary, "Nixon, the Great Society, and the Future of Social Policy", Commentary 55 (May 1973), p. 39

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ^ a b Goldberg, Jonah (20 May 2003). "The Neoconservative Invention". National Review. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Kristol, Irving (1999). Neoconservatism: The Autobiography of an Idea. Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1-56663-228-5.

- ^ Gerson, Mark (Fall 1995). "Norman's Conquest,". Policy Review. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Podhoretz, Norman (2 May 1982). "The Neoconservative Anguish over Reagan's Foreign Policy". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ Dionne, E.J. (1991). Why Americans Hate Politics. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 55–61. ISBN 0-671-68255-5.

- ^ Lipset (1988, p. 39)

- ^ Kinsley, Michael (17 April 2005). "The Neocons' Unabashed Reversal". The Washington Post. p. B07. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ Marshall, J.M. "Remaking the World: Bush and the Neoconservatives". From Foreign Affairs, November/December 2003. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ a b c Fukuyama, F. (February 19, 2006). After Neoconservatism. New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ see "Administration of George W. Bush".

- ^ Nuechterlein, James (May 1996). "The End of Neoconservatism". First Things. 63: 14–15. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

Neoconservatives differed with traditional conservatives on a number of issues, of which the three most important, in my view, were the New Deal, civil rights, and the nature of the Communist threat... On civil rights, all neocons were enthusiastic supporters of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965."

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Robert R. Tomes, Apocalypse Then: American Intellectuals and the Vietnam War, 1954-1975 (2000) p. 112.

- ^ Benjamin Balint, Running Commentary: The Contentious Magazine That Transformed the Jewish Left Into the Neoconservative Right (2010).

- ^ Irving Kristol, "Forty good years," Public Interest, Spring 2005, Issue 159, pp. 5-11 is Kristol's retrospective in the final issue.

- ^ Jeane Kirkpatrick, J (November 1979). "Dictatorships and Double Standards," Commentary Magazine Volume 68, No. 5.

- ^ Noah, T. (Dec. 8, 200). Jeane Kirkpatrick, Realist. Slate Magazine. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Jeane Kirkpatrick and the Cold War (audio)". NPR. 8 December 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ "Jeane Kirkpatrick". The Economist. 19 December 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ * Chenoweth, 1992 & 11-15: Chenoweth, Eric (Summer 1992). "The gallant warrior: In memoriam Tom Kahn" (pdf). Uncaptive minds: A journal of information and opinion on Eastern Europe. 5 (20, number 2). 1718 M Street, NW, No. 147, Washington DC 20036, USA: Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe (IDEE): 5–16. ISSN 0897-9669.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location (link)- Domber (2008, pp. 9, 35, 54–55, 79, 93, 95, 180, 446): Domber, Gregory F. (2008). Supporting the revolution: America, democracy, and the end of the Cold War in Poland, 1981–1989 (Ph.D. dissertation (12 September 2007), George Washington University). ProQuest. pp. 1–506. ISBN 0-549-38516-9. Winner of the "2009 Betty M. Unterberger Prize for Best Dissertation on United States Foreign Policy from the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations".

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Horowitz (2007, pp. 236–237): Horowitz, Rachelle (2007) [2005]. "Tom Kahn and the fight for democracy: A political portrait and personal recollection" (PDF). Democratiya (merged with Dissent in 2009). 11 (Summer): 204–251.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|origyear=|ref=harv(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - Kahn, Tom; Podhoretz, Norman (2008). "How to support Solidarnosc: A debate" (PDF). Democratiya (merged with Dissent in 2009). 13 (Summer). sponsored by the Committee for the Free World and the League for Industrial Democracy, with introduction by Midge Decter and moderation by Carl Gershman, and held at the Polish Institute for Arts and Sciences, New York City in March 1981: 230–261.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - Puddington, Arch (July 1992). "A hero of the cold war". The American Spectator. 25 (7) (The Nation's Pulse ed.): 42–44. Payment required.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Domber (2008, pp. 9, 35, 54–55, 79, 93, 95, 180, 446): Domber, Gregory F. (2008). Supporting the revolution: America, democracy, and the end of the Cold War in Poland, 1981–1989 (Ph.D. dissertation (12 September 2007), George Washington University). ProQuest. pp. 1–506. ISBN 0-549-38516-9. Winner of the "2009 Betty M. Unterberger Prize for Best Dissertation on United States Foreign Policy from the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations".

- ^

- Kahn, Tom (3 March 1982). "Moral duty". Transaction: Social Science and Modern SOCIETY. 19 (3). New York: Transactions Publishers (purchased by Springer Verlag): 51. doi:10.1007/BF02698967. ISSN 0147-2011.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kahn, Tom (July 1985), "Beyond the double standard: A social democratic view of the authoritarianism versus totalitarianism debate" (pdf), New America, January 1985 speech to the ‘Democratic Solidarity Conference’ organized by the Young Social Democrats (YSD) under the auspices of the Foundation for Democratic Education, Social Democrats, USA

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)- Reprinted: Kahn, Tom (2008) [1985]. "Beyond the double standard: A social democratic view of the authoritarianism versus totalitarianism debate" (pdf). Democratiya (merged into Dissent in 2009). 12 (Spring): 152–160.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help)

- Reprinted: Kahn, Tom (2008) [1985]. "Beyond the double standard: A social democratic view of the authoritarianism versus totalitarianism debate" (pdf). Democratiya (merged into Dissent in 2009). 12 (Spring): 152–160.

- Kahn, Tom (3 March 1982). "Moral duty". Transaction: Social Science and Modern SOCIETY. 19 (3). New York: Transactions Publishers (purchased by Springer Verlag): 51. doi:10.1007/BF02698967. ISSN 0147-2011.

- ^ Oxford University Press about the Prodigal Sons book: "...that it's easy to forget that most grew up on the edge of American society-- poor, Jewish, the children of immigrants. Prodigal Sons retraces their common past..."

- ^ Alexander Bloom, Prodigal sons: the New York intellectuals and their world (1986) p. 372.

- ^ Mason, Robert (2004). Richard Nixon and the Quest for a New Majority. UNC Press. pp. 81–88. ISBN 0-8078-2905-6.

- ^ Justin Vaïsse, Neoconservatism: The Biography of a Movement (2010) ch 3.

- ^ Arin, Kubilay Yado: Think Tanks, the Brain Trusts of US Foreign Policy. Wiesbaden: VS Springer 2013.

- ^ Lind, Michael (23 February 2004). "A Tragedy of Errors". The Nation. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ Eugene R. Sheppard, Leo Strauss and the politics of exile: the making of a political philosopher (2005) p. 1.

- ^ Allan Bloom, "Leo Strauss: September 20, 1899-October 18, 1973," Political Theory, November 1974, Vol. 2 Issue 4, pp. 372-392, an obituary and appreciation by one of his prominent students.

- ^ John P. East, "Leo Strauss and American Conservatism," Modern Age, Winter 1977, Vol. 21 Issue 1, pp. 2-19 online.

- ^ Thomas G. West, "Leo Strauss and the American Founding," Review of Politics, Winter 1991, Vol. 53 Issue 1, pp. 157-172.

- ^ Johnathan O'Neill, "Straussian constitutional history and the Straussian political project," Rethinking History, December 2009, Vol. 13 Issue 4, pp. 459-478.

- ^ Barry F. Seidman and Neil J. Murphy, eds. Toward a new political humanism (2004) p. 197.

- ^ Sheppard, Leo Strauss and the politics of exile: the making of a political philosopher (2005) pp. 1-2.

- ^ Jaques, Martin (16 November 2006). "America faces a future of managing imperial decline". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ^ Schwarz, Jonathan (14 February 2008). "The Lost Kristol Tapes: What the New York Times Bought". Tom Dispatch. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer; Pierpaoli, Paul G., ed. (2009). U.S. Leadership in Wartime: Clashes, Controversy, and Compromise, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 947. ISBN 978-1-59884-173-2. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Hirsh, Michael (November 2004). "Bernard Lewis Revisited:What if Islam isn't an obstacle to democracy in the Middle East but the secret to achieving it?". Washington Monthly. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Wing, Joel (17 April 2012). "What Role Did Neoconservatives Play In American Political Thought And The Invasion Of Iraq?". Musings on Iraq. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Podhoretz, Norman (September 2006). "Is the Bush Doctrine Dead?". Commentary. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Pope, Charles (29 September 2008). "Cheney changed his view on Iraq". Seattle Post Intelligencer. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Solarz, Stephen, et al. "Open Letter to the President", February 19, 1998, online at IraqWatch.org. Retrieved September 16, 2006.

- ^ Bailey, Ronald (July 1997). "Origin of the Specious". Reason. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Bush Begins Nation Building". WCVB TV. 16 April 2003. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012.

- ^ Vernon, Wes (7 April 2001). "China Plane Incident Sparks Re-election Drives of Security-minded Senators". Newsmax. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ Harnden, Toby; Philps, Alan (26 June 2001). "Bush accused of adopting Clinton policy on Israel". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ "Bush: Mubarak wanted me to invade Iraq", Mohammad Sagha. Foreign Policy. November 12, 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2011

- ^ "The President's State of the Union Speech." White House press release, January 29, 2002.

- ^ "Bush Speechwriter's Revealing Memoir Is Nerd's Revenge". The New York Observer, January 19, 2003

- ^ Douglas Porch, "Writing History in the "End of History" Era-- Reflections on Historians and the GWOT," Journal of Military History, October 2006, Vol. 70 Issue 4, pp. 1065-1079.

- ^ "National Security Strategy of the United States". National Security Council. 20 September 2002.

- ^ "International Law and the Bush Doctrine". Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The evolution of the Bush doctrine", in "The war behind closed doors". Frontline, PBS. February 20, 2003.

- ^ "The Bush Doctrine." Think Tank, PBS. July 11, 2002.

- ^ "Assessing the Bush Doctrine", in "The war behind closed doors." Frontline, PBS. February 20, 2003.

- ^ Bumiller, Elisabeth; Larry Rohter (10 April 2008). "2 Camps Trying to Influence McCain on Foreign Policy". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ Stephen McGlinchey, "Neoconservatism and American Foreign Policy", Politikon: The IAPSS Journal of Political Science, Vol 16, 1 (October 2010).

- ^ Kristol, Irving. "American conservatism 1945-1995". Public Interest, Fall 1995.

- ^ "Viewpoint: The end of the neocons?", Jonathan Clarke, British Broadcasting Corporation, January 13, 2009.

- ^ a b McGowan, J. (2007). "Neoconservatism". American Liberalism: An Interpretation for Our Time. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 124–133. ISBN 0-8078-3171-9.

- ^ "Neoconservatism and American Foreign Policy". Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Muravchik, Joshua (19 November 2006). "Can the Neocons Get Their Groove Back?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 November 2006.

- ^ Kristol, What Is a Neoconservative? 87.

- ^ Podhoretz, 275.

- ^ Vaisse, Neoconservatism (2010) p. 110.

- ^ Steinfels, 69.

- ^ Francis, Samuel (2004-06-07) Idol With Clay Feet, The American Conservative.

- ^ "League of Dictators?". The Washington Post. April 30, 2006.

- ^ "US: Hawks Looking for New and Bigger Enemies?". IPS. May 5, 2006.

- ^ Klein, Joe "McCain's Foreign Policy Frustration" Time, July 23, 2008.

- ^ Andrew Sullivan (5 February 2009). "A False Premise". Sullivan's Daily Dish. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Joshua Muravchik, "The Past, Present, and Future of Neoconservatism" Commentary October 2007.

- ^ Irving Kristol (25 August 2003). "The Neoconservative Persuasion". Weekly Standard. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Murray, p. 40.

- ^ William Coleman. "Heroes or Heroics? Neoconservatism, Capitalism, and Bourgeois Ethics". Social Affairs Unit. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Zeev Sternhell: The Anti-Enlightenment Tradition. New Haven, Yale University Press, 2010 ISBN 978-0-300-13554-1 p. 436.

- ^ Novak, Robert D (2007). "The prince of darkness: 50 years reporting in Washington". ISBN 978-1-4000-5199-1.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Heilbrunn, Jacob (6 January 2009). "They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons". ISBN 978-1-4000-7620-8.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Harsanyi, David (13 August 2002). "Beware the Neocons". FrontPage Magazine. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ^ Lieber, Robert J. (29 April 2003). "The Left's Neocon Conspiracy Theory". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- ^ Jeffrey Goldberg: Joe Klein on Neoconservatives and Iran The Atlantic blog, July 29, 2008.

- ^ Brooks, David (2004). "The Neocon Cabal and Other Fantasies". In Irwin Stelzer (ed.). The NeoCon Reader. Grove. ISBN 0-8021-4193-5.

- ^ Rubin, Barry (6 April 2003). "Letter from Washington". h-antisemitism. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "A 1987 article in The New Republic described these developments as a Trotskyist takeover of the Reagan administration", wrote Lipset (1988, p. 34).

- ^ Lind, Michael (7 April 2003). "The weird men behind George W. Bush's war". New Statesman. London.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Wald, Alan (2003). "Are Trotskyites Running the Pentagon?". History News Network.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wald, Alan M. (1987). The New York intellectuals: The rise and decline of the anti-Stalinist left from the 1930s to the 1980s'. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4169-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ King, William (2004). "Neoconservatives and 'Trotskyism'". American Communist History. 3 (2). Taylor and Francis: 247–266. doi:10.1080/1474389042000309817. ISSN 1474-3892.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)King, Bill (22 March 2004). "Neoconservatives and Trotskyism". Enter Stage Right: Politics, Culture, Economics (3): 1 2. ISSN 1488-1756.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Kinsley, Michael (17 April 2005). "The Neocons' Unabashed Reversal". The Washington Post. p. B07. Retrieved 25 December 2006. Kinsley quotes Rich Lowry, whom he describes as "a conservative of the non-neo variety", as criticizing the neoconservatives "messianic vision" and "excessive optimism"; Kinsley contrasts the present-day neoconservative foreign policy to earlier neoconservative Jeane Kirkpatrick's "tough-minded pragmatism".

- ^ Martin Jacques, "The neocon revolution", The Guardian, March 31, 2005. Retrieved 25 December 2006. (Cited for "unilateralism".)

- ^ Rodrigue Tremblay, "The Neo-Conservative Agenda: Humanism vs. Imperialism", presented at the Conference at the American Humanist Association annual meeting Las Vegas, May 9, 2004. Retrieved 25 December 2006 on the site of the Mouvement laïque québécois.

- ^ Paul Krugman (12 September 2011). "More About the 9/11 Anniversary". New York Times. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) (Cited for "criticism by a significant source".) - ^ a b say that neocons "propose an untenable model for our nation's future" (p 8) and then outline what they think is the inner logic of the movement:Halper, Stefan; Clarke, Johnathan (2004). America Alone: The Neo-Conservatives and the Global Order. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83834-4.

- ^ Tolson 2003.

- ^ Neoconservatism is the only answering ideology to national needs of Azerbaijan. - Hikmet Babaoglu, chief editor of ruling party New Azerbaijan Party funded newspaper New Azerbaijan. There is no country without ideology (in Azeri)

- ^ http://www.theamericanconservative.com/if-neocons-love-lieberman-why-not-crist/

- ^ http://www.msnbc.com/politicsnation/charlie-crist-racism-why-he-left-gop

- ^ "Newt Gingrich sees major Mideast mistakes, rethinks his neocon views on intervention". Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://reason.com/blog/2007/07/10/rudy-the-neo-con

- ^ http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/03/05/why-neocons-love-the-strongman.html

- ^ Horowitz, Jason (15 June 2014), "Events in Iraq Open Door for Interventionist Revival, Historian Says", New York Times, retrieved 9 October 2014

- ^ Neocons and the Ukraine Coup, Robert Parry,February 23, 2014

- ^ Mann, James (September 2004). Rise of the Vulcans (1st paperback ed.). Penguin Books. p. 318. ISBN 0-14-303489-8.

- ^ John Feffer (2003). Power Trip: Unilateralism and Global Strategy After September 11. Seven Stories Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-60980-025-3.

- ^ K. Dodds, K. and S. Elden, "Thinking Ahead: David Cameron, the Henry Jackson Society and BritishNeoConservatism," British Journal of Politics and International Relations (2008), 10(3): 347–63.

- ^ a b Danny Cooper (2011). Neoconservatism and American Foreign Policy: A Critical Analysis. Taylor & Francis. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-203-84052-8.

- ^ Matthew Christopher Rhoades (2008). Neoconservatism: Beliefs, the Bush Administration, and the Future. ProQuest. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-549-62046-4.

- ^ Matthew Christopher Rhoades (2008). Neoconservatism: Beliefs, the Bush Administration, and the Future. ProQuest. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-549-62046-4.

References

- Albanese, Matteo. "The Concept of War in Neoconservative Thinking", IPOC, Milan, 2012.Translated by Nicolas Lewkowicz. ISBN 978-8867720002

- Auster, Lawrence. "Buchanan's White Whale", FrontPageMag, March 19, 2004. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- Buchanan, Patrick J.. "Whose War", The American Conservative, March 24, 2003. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- Bush, George W., Gerhard Schroeder, et al., "Transcript: Bush, Schroeder Roundtable With German Professionals", The Washington Post, February 23, 2005. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- Critchlow, Donald T. The conservative ascendancy: how the GOP right made political history (2nd ed. 2011)

- Dean, John. Worse Than Watergate: The Secret Presidency of George W. Bush, Little, Brown, 2004. ISBN 0-316-00023-X (hardback). Critical account of neo-conservatism in the administration of George W. Bush.

- Frum, David. "Unpatriotic Conservatives", National Review, April 7, 2003. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- Gerson, Mark, ed. The Essential Neo-Conservative Reader, Perseus, 1997. ISBN 0-201-15488-9 (paperback), ISBN 0-201-47968-0 (hardback).

- Gerson, Mark. "Norman's Conquest: A Commentary on the Podhoretz Legacy", Policy Review, Fall 1995, Number 74. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- Gray, John. Black Mass, Allen Lane, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7139-9915-0.

- Hanson, Jim The Decline of the American Empire, Praeger, 1993. ISBN 0-275-94480-8.

- Halper, Stefan and Jonathan Clarke. America Alone: The Neo-Conservatives and the Global Order, Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-521-83834-7.

- Kagan, Robert, et al., Present Dangers: Crisis and Opportunity in American Foreign and Defense Policy. Encounter Books, 2000. ISBN 1-893554-16-3.

- Kristol, Irving. Neo-Conservatism: The Autobiography of an Idea: Selected Essays 1949-1995, New York: The Free Press, 1995. ISBN 0-02-874021-1 (10). ISBN 978-0-02-874021-8 (13). (Hardcover ed.) Reprinted as Neoconservatism: The Autobiography of an Idea, New York: Ivan R. Dee, 1999. ISBN 1-56663-228-5 (10). (Paperback ed.)

- – . "What Is a Neoconservative?", Newsweek, January 19, 1976.

- Lara Amat y León, Joan y Antón Mellón, Joan, “Las persuasiones neoconservadoras: F. Fukuyama, S. P. Huntington, W. Kristol y R. Kagan”, en Máiz, Ramón (comp.), Teorías políticas contemporáneas, (2ªed.rev. y ampl.) Tirant lo Blanch, Valencia, 2009. ISBN 978-84-9876-463-5. Ficha del libro

- Lara Amat y León, Joan, “Cosmopolitismo y anticosmoplitismo en el neoconservadurismo: Fukuyama y Huntington”, en Nuñez, Paloma y Espinosa, Javier (eds.), Filosofía y política en el siglo XXI. Europa y el nuevo orden cosmopolita, Akal, Madrid, 2009. ISBN 978-84-460-2875-8. Ficha del libro

- Lasn, Kalle. "Why won't anyone say they are Jewish?", Adbusters, March/April 2004. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- Lewkowicz, Nicolas. "Neoconservatism and the Propagation of Democracy", Democracy Chronicles, February 11, 2013.

- Lipset, Seymour (4 July 1988). "Neoconservatism: Myth and reality". Society. 25 (5). New York: Transactions (purchased by Springer): 29–37. doi:10.1007/BF02695739. ISSN 0147-2011.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mann, James. Rise of the Vulcans: The History of Bush's War Cabinet, Viking, 2004. ISBN 0-670-03299-9 (cloth).

- Massing, Michael (1987). "Trotsky's orphans: From Bolshevism to Reaganism". The New Republic: 18–22.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mascolo, Georg. ""A Leaderless, Directionless Superpower: interview with Ex-Powell aide Wilkerson", Spiegel Online, December 6, 2005. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- Muravchik, Joshua. "Renegades", Commentary, October 1, 2002. Bibliographical information is available online, the article itself is not.

- Muravchik, Joshua. "The Neoconservative Cabal", Commentary, September 2003. Bibliographical information is available online, the article itself is not.

- Prueher, Joseph. U.S. apology to China over spy plane incident, April 11, 2001. Reproduced on sinomania.com. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- Podoretz, Norman. The Norman Podhoretz Reader. New York: Free Press, 2004. ISBN 0-7432-3661-0.

- Roucaute Yves. Le Neoconservatisme est un humanisme. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2005.ISBN 2-13-055016-9.

- Roucaute Yves. La Puissance de la Liberté. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2004.ISBN 2-13-054293-X.

- Ruppert, Michael C.. Crossing the Rubicon: The Decline of the American Empire at the End of the Age of Oil, New Society, 2004. ISBN 0-86571-540-8.

- Ryn, Claes G., America the Virtuous: The Crisis of Democracy and the Quest for Empire, Transaction, 2003. ISBN 0-7658-0219-8 (cloth).

- Stelzer, Irwin, ed. Neoconservatism, Atlantic Books, 2004.

- Smith, Grant F. Deadly Dogma: How Neoconservatives Broke the Law to Deceive America. ISBN 0-9764437-4-0.

- Solarz, Stephen, et al. "Open Letter to the President", February 19, 1998, online at IraqWatch.org. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- Steinfels, Peter (1979). The neoconservatives: The men who are changing America's politics. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22665-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Strauss, Leo. Natural Right and History, University of Chicago Press, 1999. ISBN 0-226-77694-8.

- Strauss, Leo. The Rebirth of Classical Political Rationalism, University of Chicago Press, 1989. ISBN 0-226-77715-4.

- Tolson, Jay. "The New American Empire?", U.S. News and World Report, January 13, 2003. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- Wilson, Joseph. The Politics of Truth. Carroll & Graf, 2004. ISBN 0-7867-1378-X.

- Woodward, Bob. Plan of Attack, Simon and Schuster, 2004. ISBN 0-7432-5547-X.

Further reading

- Arin, Kubilay Yado: Think Tanks, the Brain Trusts of US Foreign Policy. Wiesbaden: VS Springer 2013.

- Balint, Benjamin V. Running Commentary: The Contentious Magazine that Transformed the Jewish Left into the Neoconservative Right (2010)

- Dorrien, Gary. The Neoconservative Mind. ISBN 1-56639-019-2, n attack from the Left

- Ehrman, John. The Rise of Neoconservatism: Intellectual and Foreign Affairs 1945 – 1994, Yale University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-300-06870-0, friendly analysis

- Friedman, Murray. The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-521-54501-3.

- Heilbrunn, Jacob. They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons, Doubleday (2008) ISBN 0-385-51181-7

- Heilbrunn, Jacob. "5 Myths About Those Nefarious Neocons," Washington Post, Feb. 10, 2008

- Kristol, Irving. "The Neoconservative Persuasion".

- Lind, Michael. "How Neoconservatives Conquered Washington", Salon, April 9, 2003.

- Vaïsse, Justin. Neoconservatism: The Biography of a Movement (Harvard U.P. 2010), translated from the French

Identity

- "Neoconservatism: Key Figures",The Christian Science Monitor.

- Steigerwald, Bill. "So, what is a 'neocon'?"

- Stelzer, Irwin. "Nailing the neocon myth". The Times (London)

- Selden, Zachary, "Neoconservatives and the American Mainstream". Selden is director of the Defence and Security Committee of the NATO Parliamentary Assembly.

Critiques

- Fukuyama, Francis. "After Neoconservatism". Archived copy of original New York Times article. Also available in .pdf

- Thompson, Bradley C. (with Yaron Brook). Neoconservatism. An Obituary for an Idea. Boulder/London: Paradigm Publishers, 2010. ISBN 978-1-59451-831-7.