Naringenin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(2S)-4′,5,7-Trihydroxyflavan-4-one

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2S)-5,7-Dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one | |

| Other names

Naringetol; Salipurol; Salipurpol

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.865 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H12O5 | |

| Molar mass | 272.256 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 251 °C (484 °F; 524 K)[1] |

| 475 mg/L[1] | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Naringenin is a flavorless,[2] colorless[3] flavanone, a type of flavonoid. It is the predominant flavanone in grapefruit,[4] and is found in a variety of fruits and herbs.[5]

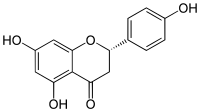

Structure

Naringenin has the skeleton structure of a flavanone with three hydroxy groups at the 4', 5, and 7 carbons. It may be found both in the aglycol form, naringenin, or in its glycosidic form, naringin, which has the addition of the disaccharide neohesperidose attached via a glycosidic linkage at carbon 7.

Like the majority of flavanones, naringenin has a single chiral center at carbon 2, although the optical purity is variable.[5][6] Racemization of (S)-(-)-naringenin has been shown to occur fairly quickly.[7]

Sources and bioavailability

Naringenin and its glycoside has been found in a variety of herbs and fruits, including grapefruit,[8] bergamot,[9] sour orange,[10] tart cherries,[11] tomatoes,[12][13] cocoa,[14] Greek oregano,[15] water mint,[16] as well as in beans.[17] Ratios of naringenin to naringin vary among sources,[12] as do enantiomeric ratios.[6]

The naringenin-7-glucoside form seems less bioavailable than the aglycol form.[18]

Grapefruit juice can provide much higher plasma concentrations of naringenin than orange juice.[19] Also found in grapefruit is the related compound kaempferol, which has a hydroxyl group next to the ketone group.

Naringenin can be absorbed from cooked tomato paste. There are 3.8 mg of naringenin in 150 grams of tomato paste.[20]

Biosynthesis and metabolism

It is derived from malonyl CoA and 4-coumaroyl CoA. The latter is derived from phenylalanine. The resulting tetraketide is acted on by chalcone synthase to give the chalcone that then undergoes ring-closure to naringenin.[21]

The enzyme naringenin 8-dimethylallyltransferase uses dimethylallyl diphosphate and (−)-(2S)-naringenin to produce diphosphate and 8-prenylnaringenin. Cunninghamella elegans, a fungal model organism of the mammalian metabolism, can be used to study the naringenin sulfation.[22]

Potential biological effects

This section needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (June 2017) |  |

Alzheimer's disease

Naringenin is being researched as a potential treatment for Alzheimer's disease. Naringenin has been demonstrated to improve memory and reduce amyloid and tau proteins in a study using a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease.[23][24] The effect is believed to be due to a protein present in neurons known as CRMP2 that naringenin binds to.[25]

Antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral

Naringenin has an antimicrobial effect on S. epidermidis, as well as Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Micrococcus luteus, and Escherichia coli.[26] Further research has added evidence for antimicrobial effects against Lactococcus lactis,[27] lactobacillus acidophilus, Actinomyces naeslundii, Prevotella oralis, Prevotella melaninogencia, Porphyromonas gingivalis,[28] as well as yeasts such as Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, and Candida krusei.[29] There is also evidence of antibacterial effects on H. pylori, though naringenin has not been shown to have any inhibition on urease activity of the microbe.[30]

Naringenin has also been shown to reduce hepatitis C virus production by infected hepatocytes (liver cells) in cell culture. This seems to be secondary to naringenin's ability to inhibit the secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein by the cells.[31] The antiviral effects of naringenin are currently under clinical investigation.[32] Reports of antiviral effects on polioviruses, HSV-1 and HSV-2 have also been made, though replication of the viruses has not been inhibited.[33][34] In in vitro experiments Naringenin also showed a strong antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2. [35]

Anti-inflammatory

Despite evidence of anti-inflammatory activity of naringin,[36] the anti-inflammatory activity of naringenin has been observed to be poor to nonexistent.[37][38]

Antioxidant

Naringenin has been shown to have significant antioxidant properties.[39][40] It has been shown to reduce oxidative damage to DNA in vitro and in animal studies.[41][42]

Anticancer

Cytotoxicity has been induced reportedly by naringenin in cancer cells from breast, stomach, liver, cervix, pancreas, and colon tissues, along with leukaemia cells.[43][44] The mechanisms behind inhibition of human breast carcinoma growth have been examined, and two theories have been proposed.[45] The first theory is that naringenin inhibits aromatase, thus reducing growth of the tumor.[46] The second mechanism proposes that interactions with estrogen receptors is the cause behind the modulation of growth.[47] New derivatives of naringenin were found to be active against multidrug-resistant cancer.[48]

Additional reading

- inhibitory effect on the human cytochrome P450 isoform CYP1A2 resulting in delayed clearance of substances and protective effect against P4501A2-activated protoxicants.Fuhr U, Klittich K, Staib AH (April 1993). "Inhibitory effect of grapefruit juice and its bitter principal, naringenin, on CYP1A2 dependent metabolism of caffeine in man". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 35 (4): 431–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb04162.x. PMC 1381556. PMID 8485024.Ueng YF, Chang YL, Oda Y, Park SS, Liao JF, Lin MF, Chen CF (1999). "In vitro and in vivo effects of naringin on cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase in mouse liver". Life Sci. 65 (24): 2591–602. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00528-7. PMID 10619367.

- Wistuba, Dorothee; Trapp, Oliver; Gel-Moreto, Nuria; Galensa, Rudolf; Schurig, Volker (2006-05-01). "Stereoisomeric Separation of Flavanones and Flavanone-7-O-glycosides by Capillary Electrophoresis and Determination of Interconversion Barriers". Analytical Chemistry. 78 (10): 3424–3433. doi:10.1021/ac0600499. ISSN 0003-2700. PMID 16689546.

- Krause, Martin; Galensa, Rudolf (1991). "High-performance liquid chromatography of diastereomeric flavanone glycosides in Citrus on a β-cyclodextrin-bonded stationary phase (Cyclobond I)". Journal of Chromatography A. 588 (1–2): 41–45. doi:10.1016/0021-9673(91)85005-z.

- Gaggeri, Raffaella; Rossi, Daniela; Collina, Simona; Mannucci, Barbara; Baierl, Marcel; Juza, Markus (2011-08-12). "Quick development of an analytical enantioselective high performance liquid chromatography separation and preparative scale-up for the flavonoid Naringenin". Journal of Chromatography A. 1218 (32): 5414–5422. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2011.02.038. PMID 21397238.

- Wan, Lili; Sun, Xipeng; Li, Yan; Yu, Qi; Guo, Cheng; Wang, Xiangwei (2011-04-01). "A Stereospecific HPLC Method and Its Application in Determination of Pharmacokinetics Profile of Two Enantiomers of Naringenin in Rats". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 49 (4): 316–320. doi:10.1093/chrsci/49.4.316. ISSN 0021-9665. PMID 21439124.

- Naringenin also produces BDNF-dependent antidepressant-like effects in mice.Yi LT, Liu BB, Li J, Luo L, Liu Q, Geng D, Tang Y, Xia Y, Wu D (October 2013). "BDNF signaling is necessary for the antidepressant-like effect of naringenin". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 48C: 135–141. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.10.002. PMID 24121063. S2CID 24620048.

- Gao, K; Henning, S; Niu, Y; Youssefian, A; Seeram, N; Xu, A; Heber, D (2006). "The citrus flavonoid naringenin stimulates DNA repair in prostate cancer cells". The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 17 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.05.009. PMID 16111881.

- Katavic PL, Lamb K, Navarro H, Prisinzano TE (August 2007). "Flavonoids as opioid receptor ligands: identification and preliminary structure-activity relationships". J. Nat. Prod. 70 (8): 1278–82. doi:10.1021/np070194x. PMC 2265593. PMID 17685652.

- Naringenin has been reported to induce apoptosis in preadipocytes.Hsu, Chin-Lin; Huang, Shih-Li; Yen, Gow-Chin (2006-06-01). "Inhibitory Effect of Phenolic Acids on the Proliferation of 3T3-L1 Preadipocytes in Relation to Their Antioxidant Activity". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54 (12): 4191–4197. doi:10.1021/jf0609882. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 16756346.

- Naringenin seems to protect LDLR-deficient mice from the obesity effects of a high-fat diet.Mulvihill EE, Allister EM, Sutherland BG, Telford DE, Sawyez CG, Edwards JY, Markle JM, Hegele RA, Huff MW (October 2009). "Naringenin prevents dyslipidemia, apolipoprotein B overproduction, and hyperinsulinemia in LDL receptor-null mice with diet-induced insulin resistance". Diabetes. 58 (10): 2198–210. doi:10.2337/db09-0634. PMC 2750228. PMID 19592617.

- Naringenin lowers the plasma and hepatic cholesterol concentrations by suppressing HMG-CoA reductase and ACAT in rats fed a high-cholesterol diet.Lee SH, Park YB, Bae KH, Bok SH, Kwon YK, Lee ES, Choi MS (1999). "Cholesterol-lowering activity of naringenin via inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase and acyl coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase in rats". Ann. Nutr. Metab. 43 (3): 173–80. doi:10.1159/000012783. PMID 10545673. S2CID 5685548.

- Naringenin has been demonstrated to improve memory and reduce amyloid and tau proteins in a study using a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease.Ghofraniab, Saeed; Joghataei, Mohammad-Taghi; Mohsenia, Simin; Baluchnejadmojaradd, Tourandokht; Bagheriac, Maryam; Khamsee, Safoura; Roghani, Mehrdad (5 October 2015). "Naringenin improves learning and memory in an Alzheimer's disease rat model: Insights into the underlying mechanisms". European Journal of Pharmacology. 764: 195–201. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.07.001. PMID 26148826.Yang, Zhiyou; Kuboyama, Tomoharu; Tohda, Chihiro (2019-02-15). "Naringenin promotes microglial M2 polarization and Aβ degradation enzyme expression". Phytotherapy Research. 33 (4): 1114–1121. doi:10.1002/ptr.6305. ISSN 1099-1573. PMID 30768735. S2CID 73449033.Yang, Zhiyou; Kuboyama, Tomoharu; Tohda, Chihiro (19 June 2017). "A Systematic Strategy for Discovering a Therapeutic Drug for Alzheimer's Disease and Its Target Molecule". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 8: 340. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00340. PMC 5474478. PMID 28674493.

References

- ^ a b "Naringenin". ChemIDplus. Archived from the original on 2015-12-20.

- ^ Esaki, Sachiko; Nishiyama, Kiyotoshi; Sugiyama, Naoko; Nakajima, Ryuta; Takao, Yoshihiro; Kamiya, Shintaro (1994-01-01). "Preparation and Taste of Certain Glycosides of Flavanones and of Dihydrochalcones". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 58 (8): 1479–1485. doi:10.1271/bbb.58.1479. ISSN 0916-8451. PMID 7765281.

- ^ Shin, W.; Kim, S.; Chun, K. S. (1987-10-15). "Structure of (R,S)-hesperetin monohydrate". Acta Crystallographica Section C. 43 (10): 1946–1949. doi:10.1107/s0108270187089510. ISSN 0108-2701.

- ^ Felgines C, Texier O, Morand C, Manach C, Scalbert A, Régerat F, Rémésy C (December 2000). "Bioavailability of the flavanone naringenin and its glycosides in rats" (PDF). Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 279 (6): G1148–54. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.6.G1148. PMID 11093936. S2CID 27540043.

- ^ a b Yáñez, Jaime A.; Andrews, Preston K.; Davies, Neal M. (2007-04-01). "Methods of analysis and separation of chiral flavonoids". Journal of Chromatography B. 848 (2): 159–181. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.052. PMID 17113835.

- ^ a b Yáñez, Jaime A.; Remsberg, Connie M.; Miranda, Nicole D.; Vega-Villa, Karina R.; Andrews, Preston K.; Davies, Neal M. (2008-01-01). "Pharmacokinetics of selected chiral flavonoids: hesperetin, naringenin and eriodictyol in rats and their content in fruit juices". Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition. 29 (2): 63–82. doi:10.1002/bdd.588. ISSN 1099-081X. PMID 18058792. S2CID 24051610.

- ^ Krause, M.; Galensa, R. (1991-07-01). "Analysis of enantiomeric flavanones in plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography on a cellulose triacetate based chiral stationary phase". Chromatographia. 32 (1–2): 69–72. doi:10.1007/BF02262470. ISSN 0009-5893. S2CID 95215634.

- ^ Ho, Ping C; Saville, Dorothy J; Coville, Peter F; Wanwimolruk, Sompon (2000-04-01). "Content of CYP3A4 inhibitors, naringin, naringenin and bergapten in grapefruit and grapefruit juice products". Pharmaceutica Acta Helvetiae. 74 (4): 379–385. doi:10.1016/S0031-6865(99)00062-X. PMID 10812937.

- ^ Gattuso, Giuseppe; Barreca, Davide; Gargiulli, Claudia; Leuzzi, Ugo; Caristi, Corrado (2007-08-03). "Flavonoid Composition of Citrus Juices". Molecules. 12 (8): 1641–1673. doi:10.3390/12081641. PMC 6149096. PMID 17960080.

- ^ Gel-Moreto, Nuria; Streich, René; Galensa, Rudolf (2003-08-01). "Chiral separation of diastereomeric flavanone-7-O-glycosides in citrus by capillary electrophoresis". Electrophoresis. 24 (15): 2716–2722. doi:10.1002/elps.200305486. ISSN 0173-0835. PMID 12900888. S2CID 40261445.

- ^ Wang, H.; Nair, M. G.; Strasburg, G. M.; Booren, A. M.; Gray, J. I. (1999-03-01). "Antioxidant polyphenols from tart cherries (Prunus cerasus)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 47 (3): 840–844. doi:10.1021/jf980936f. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 10552377.

- ^ a b Minoggio, M.; Bramati, L.; Simonetti, P.; Gardana, C.; Iemoli, L.; Santangelo, E.; Mauri, P. L.; Spigno, P.; Soressi, G. P. (2003-01-01). "Polyphenol pattern and antioxidant activity of different tomato lines and cultivars". Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism. 47 (2): 64–69. doi:10.1159/000069277. ISSN 0250-6807. PMID 12652057. S2CID 26333030.

- ^ Vallverdú-Queralt, A; Odriozola-Serrano, I; Oms-Oliu, G; Lamuela-Raventós, RM; Elez-Martínez, P; Martín-Belloso, O (2012). "Changes in the polyphenol profile of tomato juices processed by pulsed electric fields". J Agric Food Chem. 60 (38): 9667–9672. doi:10.1021/jf302791k. PMID 22957841.

- ^ Sánchez-Rabaneda, Ferran; Jáuregui, Olga; Casals, Isidre; Andrés-Lacueva, Cristina; Izquierdo-Pulido, Maria; Lamuela-Raventós, Rosa M. (2003-01-01). "Liquid chromatographic/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometric study of the phenolic composition of cocoa (Theobroma cacao)". Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 38 (1): 35–42. Bibcode:2003JMSp...38...35S. doi:10.1002/jms.395. ISSN 1076-5174. PMID 12526004.

- ^ Exarchou, Vassiliki; Godejohann, Markus; van Beek, Teris A.; Gerothanassis, Ioannis P.; Vervoort, Jacques (2003-11-01). "LC-UV-Solid-Phase Extraction-NMR-MS Combined with a Cryogenic Flow Probe and Its Application to the Identification of Compounds Present in Greek Oregano". Analytical Chemistry. 75 (22): 6288–6294. doi:10.1021/ac0347819. ISSN 0003-2700. PMID 14616013.

- ^ Olsen, Helle T.; Stafford, Gary I.; van Staden, Johannes; Christensen, Søren B.; Jäger, Anna K. (2008-05-22). "Isolation of the MAO-inhibitor naringenin from Mentha aquatica L.". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 117 (3): 500–502. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2008.02.015. PMID 18372132.

- ^ Hungria, M.; Johnston, A. W.; Phillips, D. A. (1992-05-01). "Effects of flavonoids released naturally from bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) on nodD-regulated gene transcription in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. phaseoli". Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 5 (3): 199–203. doi:10.1094/mpmi-5-199. ISSN 0894-0282. PMID 1421508.

- ^ Choudhury R, Chowrimootoo G, Srai K, Debnam E, Rice-Evans CA (November 1999). "Interactions of the flavonoid naringenin in the gastrointestinal tract and the influence of glycosylation". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 265 (2): 410–5. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.1695. PMID 10558881.

- ^ Erlund I, Meririnne E, Alfthan G, Aro A (February 2001). "Plasma kinetics and urinary excretion of the flavanones naringenin and hesperetin in humans after ingestion of orange juice and grapefruit juice". J. Nutr. 131 (2): 235–41. doi:10.1093/jn/131.2.235. PMID 11160539.

- ^ Bugianesi R, Catasta G, Spigno P, D'Uva A, Maiani G (November 2002). "Naringenin from cooked tomato paste is bioavailable in men". J. Nutr. 132 (11): 3349–52. doi:10.1093/jn/132.11.3349. PMID 12421849.

- ^ Wang, Chuanhong; Zhi, Shuang; Liu, Changying; Xu, Fengxiang; Zhao, Aichun; Wang, Xiling; Ren, Yanhong; Li, Zhengang; Yu, Maode (2017). "Characterization of Stilbene Synthase Genes in Mulberry (Morus atropurpurea) and Metabolic Engineering for the Production of Resveratrol in Escherichia coli". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 65 (8): 1659–1668. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.6b05212. PMID 28168876.

- ^ Ibrahim AR (January 2000). "Sulfation of naringenin by Cunninghamella elegans". Phytochemistry. 53 (2): 209–12. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00487-2. PMID 10680173.

- ^ Ghofraniab, Saeed; Joghataei, Mohammad-Taghi; Mohsenia, Simin; Baluchnejadmojaradd, Tourandokht; Bagheriac, Maryam; Khamsee, Safoura; Roghani, Mehrdad (5 October 2015). "Naringenin improves learning and memory in an Alzheimer's disease rat model: Insights into the underlying mechanisms". European Journal of Pharmacology. 764: 195–201. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.07.001. PMID 26148826.

- ^ Yang, Zhiyou; Kuboyama, Tomoharu; Tohda, Chihiro (2019-02-15). "Naringenin promotes microglial M2 polarization and Aβ degradation enzyme expression". Phytotherapy Research. 33 (4): 1114–1121. doi:10.1002/ptr.6305. ISSN 1099-1573. PMID 30768735. S2CID 73449033.

- ^ Yang, Zhiyou; Kuboyama, Tomoharu; Tohda, Chihiro (19 June 2017). "A Systematic Strategy for Discovering a Therapeutic Drug for Alzheimer's Disease and Its Target Molecule". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 8: 340. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00340. PMC 5474478. PMID 28674493.

- ^ Rauha, Jussi-Pekka; Remes, Susanna; Heinonen, Marina; Hopia, Anu; Kähkönen, Marja; Kujala, Tytti; Pihlaja, Kalevi; Vuorela, Heikki; Vuorela, Pia (2000-05-25). "Antimicrobial effects of Finnish plant extracts containing flavonoids and other phenolic compounds". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 56 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00218-X. PMID 10857921.

- ^ Mandalari, G.; Bennett, R. N.; Bisignano, G.; Trombetta, D.; Saija, A.; Faulds, C. B.; Gasson, M. J.; Narbad, A. (2007-12-01). "Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids extracted from bergamot (Citrus bergamia Risso) peel, a byproduct of the essential oil industry". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 103 (6): 2056–2064. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03456.x. ISSN 1364-5072. PMID 18045389.

- ^ Koru, Ozgur; Toksoy, Fulya; Acikel, Cengiz Han; Tunca, Yasar Meric; Baysallar, Mehmet; Uskudar Guclu, Aylin; Akca, Eralp; Ozkok Tuylu, Asli; Sorkun, Kadriye (2007-06-01). "In vitro antimicrobial activity of propolis samples from different geographical origins against certain oral pathogens". Anaerobe. 13 (3–4): 140–145. doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2007.02.001. ISSN 1075-9964. PMID 17475517.

- ^ Uzel, Ataç; Sorkun, Kadri˙ye; Önçağ, Özant; Çoğulu, Dilşah; Gençay, Ömür; Sali˙h, Beki˙r (2005-04-25). "Chemical compositions and antimicrobial activities of four different Anatolian propolis samples". Microbiological Research. 160 (2): 189–195. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2005.01.002. hdl:11655/19951. PMID 15881836.

- ^ Bae, Eun-Ah; Han, Myung; Kim, Dong-Hyun (1999). "In vitroAnti-Helicobacter pylori Activity of Some Flavonoids and Their Metabolites". Planta Medica. 65 (5): 442–443. doi:10.1055/s-2006-960805. PMID 10454900.

- ^ Nahmias Y, Goldwasser J, Casali M, van Poll D, Wakita T, Chung RT, Yarmush ML (May 2008). "Apolipoprotein B-dependent hepatitis C virus secretion is inhibited by the grapefruit flavonoid naringenin". Hepatology. 47 (5): 1437–45. doi:10.1002/hep.22197. PMC 4500072. PMID 18393287.

- ^ "A Pilot Study of the Grapefruit Flavonoid Naringenin for HCV Infection - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-10-01.

- ^ Mucsi, I.; Prágai, B. M. (1985-07-01). "Inhibition of virus multiplication and alteration of cyclic AMP level in cell cultures by flavonoids". Experientia. 41 (7): 930–931. doi:10.1007/BF01970018. ISSN 0014-4754. PMID 2989000. S2CID 6174141.

- ^ Lyu, Su-Yun; Rhim, Jee-Young; Park, Won-Bong (2005-11-01). "Antiherpetic activities of flavonoids against herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2)in vitro". Archives of Pharmacal Research. 28 (11): 1293–1301. doi:10.1007/BF02978215. ISSN 0253-6269. PMID 16350858. S2CID 34495208.

- ^ Nicola, Clementi; Carolina, Scagnolari; Elena, Criscuolo (2020-10-20). "Naringenin is a powerful inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro". Pharmacol Research. 105255: 105255. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105255. ISSN 1043-6618. PMC 7574776. PMID 33096221.

- ^ Kawaguchi, K.; Kikuchi, S.; Hasunuma, R.; Maruyama, H.; Ryll, R.; Kumazawa, Y. (2004). "Suppression of Infection-Induced Endotoxin Shock in Mice by aCitrusFlavanone Naringin". Planta Medica. 70 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1055/s-2004-815449. PMID 14765287.

- ^ Gutiérrez-Venegas, Gloria; Kawasaki-Cárdenas, Perla; Rita Arroyo-Cruz, Santa; Maldonado-Frías, Silvia (2006-07-10). "Luteolin inhibits lipopolysaccharide actions on human gingival fibroblasts". European Journal of Pharmacology. 541 (1–2): 95–105. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.069. PMID 16762341.

- ^ Olszanecki, R.; Gebska, A.; Kozlovski, V. I.; Gryglewski, R. J. (2002-12-01). "Flavonoids and nitric oxide synthase". Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 53 (4 Pt 1): 571–584. ISSN 0867-5910. PMID 12512693.

- ^ Gorinstein, Shela; Leontowicz, Hanna; Leontowicz, Maria; Krzeminski, Ryszard; Gralak, Mikolaj; Delgado-Licon, Efren; Martinez Ayala, Alma Leticia; Katrich, Elena; Trakhtenberg, Simon (2005-04-01). "Changes in Plasma Lipid and Antioxidant Activity in Rats as a Result of Naringin and Red Grapefruit Supplementation". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (8): 3223–3228. doi:10.1021/jf058014h. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 15826081.

- ^ Yu, Jun; Wang, Limin; Walzem, Rosemary L.; Miller, Edward G.; Pike, Leonard M.; Patil, Bhimanagouda S. (2005-03-01). "Antioxidant Activity of Citrus Limonoids, Flavonoids, and Coumarins". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (6): 2009–2014. doi:10.1021/jf0484632. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 15769128.

- ^ Sumit Kumar & Ashu Bhan Tiku (2016). "Biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms of Radioprotective Effects of Naringenin, a Phytochemical from Citrus Fruits". J. Agric. Food Chem. 64 (8): 1676–1685. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05067. PMID 26881453.

- ^ Chandra Jagetia, Ganesh; Koti Reddy, Tiyyagura; Venkatesha, V. A; Kedlaya, Rajendra (2004-09-01). "Influence of naringin on ferric iron induced oxidative damage in vitro". Clinica Chimica Acta. 347 (1–2): 189–197. doi:10.1016/j.cccn.2004.04.022. PMID 15313158.

- ^ Kanno, Syu-ichi; Tomizawa, Ayako; Hiura, Takako; Osanai, Yuu; Shouji, Ai; Ujibe, Mayuko; Ohtake, Takaharu; Kimura, Katsuhiko; Ishikawa, Masaaki (2005-01-01). "Inhibitory Effects of Naringenin on Tumor Growth in Human Cancer Cell Lines and Sarcoma S-180-Implanted Mice". Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 28 (3): 527–530. doi:10.1248/bpb.28.527. PMID 15744083.

- ^ Hermawan A, Ikawati M, Jenie RI, Khumaira A, Putri H, Nurhayati IP, Angraini SM, Muflikhasari HA (January 2021). "Identification of potential therapeutic target of naringenin in breast cancer stem cells inhibition by bioinformatics and in vitro studies". Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 29 (1): 12–26. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2020.12.002. PMC 7873751. PMID 33603536.

- ^ So, Felicia V.; Guthrie, Najla; Chambers, Ann F.; Moussa, Madeleine; Carroll, Kenneth K. (1996-01-01). "Inhibition of human breast cancer cell proliferation and delay of mammary tumorigenesis by flavonoids and citrus juices". Nutrition and Cancer. 26 (2): 167–181. doi:10.1080/01635589609514473. ISSN 0163-5581. PMID 8875554.

- ^ van Meeuwen, J. A.; Korthagen, N.; de Jong, P. C.; Piersma, A. H.; van den Berg, M. (2007-06-15). "(Anti)estrogenic effects of phytochemicals on human primary mammary fibroblasts, MCF-7 cells and their co-culture". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 221 (3): 372–383. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2007.03.016. PMID 17482226.

- ^ Harmon, Anne W.; Patel, Yashomati M. (2004-05-01). "Naringenin Inhibits Glucose Uptake in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells: A Mechanism for Impaired Cellular Proliferation". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 85 (2): 103–110. doi:10.1023/B:BREA.0000025397.56192.e2. ISSN 0167-6806. PMID 15111768. S2CID 24436665.

- ^ Ferreira, Ricardo J; Baptista, Rafael; Moreno, Alexis; Madeira, Patricia G; Khonkarn, Ruttiros; Baubichon-Cortay, Hélène; Santos, Daniel JVA dos; Falson, Pierre; Ferreira, Maria-José U (2018-03-23). "Optimizing the flavanone core toward new selective nitrogen-containing modulators of ABC transporters". Future Medicinal Chemistry. 10 (7): 725–741. doi:10.4155/fmc-2017-0228. PMID 29570361.