Economy of China

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (July 2010) |

| |

| Currency | Renminbi (RMB); Unit: Yuan (CNY) |

|---|---|

| USD = 6.3900 RMB (25 August 2011) [1] | |

| Calendar year 01 January to 31 December | |

Trade organisations | WTO, APEC, G-20 and others |

| Statistics | |

| GDP | $5.88 trillion (nominal: 2nd; 2010) $10.08 trillion (PPP: 2nd; 2010) |

GDP growth | 10.46% (major economies: 1st; 2010) |

GDP per capita | $4,283 (nominal: 95th; 2010) $7,518 (PPP: 93rd; 2010) |

GDP by sector | industry (46.8%), services (43.6%), agriculture (9.6%) (2010 est.) |

| 4.9% (January 2011)[2] | |

| 41.5 | |

Labour force | 780 million (1st; 2010) |

Labour force by occupation | agriculture (39.5%), industry (27.2%), services (33.2%) (2008) |

| Unemployment | 4.2% (July 2010)[3] |

Main industries | mining and ore processing, iron, steel, aluminum, and other metals, coal; machine building; armaments; textiles and apparel; petroleum; cement; chemicals; fertilizers; consumer products, including footwear, toys, and electronics; food processing; transportation equipment, including automobiles, rail cars and locomotives, ships, and aircraft; telecommunications equipment, commercial space launch vehicles, satellites |

| External | |

| Exports | US$1.506 trillion (2010) |

Export goods | electrical and other machinery, including data processing equipment, apparel, textiles, iron and steel, optical and medical equipment |

Main export partners | US 20.03%, Hong Kong 12.03%, Japan 8.32%, South Korea 4.55%, Germany 4.27% (2009) |

| Imports | US$1.307 trillion (2010) |

Import goods | electrical and other machinery, oil and mineral fuels, optical and medical equipment, metal ores, plastics, organic chemicals |

Main import partners | Japan 12.27%, Hong Kong 10.06%, South Korea 9.04%, US 7.66%, Taiwan 6.84%, Germany 5.54% (2009) |

FDI stock | $100 billion (2010) |

Gross external debt | $406.6 billion (22nd; 2010) |

| Public finances | |

| 17.5% of GDP (112th; 2010) | |

| Revenues | $1.149 trillion (2010) |

| Expenses | $1.27 trillion (2010) |

| Economic aid | recipient: $1.12 per capita (2008)[4] |

| AA- (Domestic) AA- (Foreign) AA- (T&C Assessment) (Standard & Poor's)[5] | |

| $3.05 trillion (1st; 2011) | |

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The People's Republic of China (PRC) ranks since 2010 as the world's second largest economy after the United States. It is one of the world's fastest-growing major economies, with consistent growth rates of 5% - 15% over the past 30 years. China is also the largest exporter and second largest importer of goods in the world. China became the world's top manufacturer in 2011, surpassing the United States . The country's per capita GDP (PPP) was $7,518 (International Monetary Fund, 93rd in the world) in 2010 and poverty, especially in rural areas, is still prevalent. The provinces in the coastal regions of China[6] tend to be more industrialized, while regions in the hinterland are less developed. As China's economic importance has grown, so has attention to the structure and health of that economy.[7][8]. China is still a recipient of foreign aid.

Overview

In the modern era, China's influence in the world economy was minimal until the late 1980s. At that time, economic reforms initiated after 1978 began to generate significant and steady growth in investment, consumption and standards of living. China now participates extensively in the world market and mostly state owned but also some private sector companies play a major role in the economy. Since 1978 hundreds of millions have been lifted out of poverty - yet hundred of millions of rural population as well as millions of migrant workers remain unattended: According to China's official statistics, the poverty rate fell from 53% in 1981[9] to 2.5% in 2005. However, in 2009, as many as 150 million Chinese were living on less than $1.25 a day [10] The infant mortality rate fell by 39.5% between 1990 and 2005,[11] and maternal mortality by 41.1%.[12] Access to telephones during the period rose more than 94-fold, to 57.1%.[13] as did in many development countries such as Peru or Nigeria.

In the 1949 revolution, China's economic system was officially made into a communist system. Since the wide-ranging reforms of the 1980s and afterwards, many scholars assert that China can be defined as one of the leading examples of state capitalism today.[14][15]

China has generally implemented reforms in a gradualist fashion. As its role in world trade has steadily grown, its importance to the international economy has also increased apace. China's foreign trade has grown faster than its GDP for the past 25 years.[16] China's growth comes both from huge state investment in infrastructure and heavy industry and from private sector expansion in light industry instead of just exports, whose role in the economy appears to have been significantly overestimated.[17] The smaller but highly concentrated public sector, dominated by 159 large SOEs, provided key inputs from utilities, heavy industries, and energy resources that facilitated private sector growth and drove investment, the foundation of national growth. In 2008 thousands of private companies closed down and the government announced plans to expand the public sector to take up the slack caused by the global financial crisis.[18] In 2010, there were approximately 10 million small businesses in China.[19]

The PRC government's decision to permit China to be used by multinational corporations as an export platform has made the country a major competitor to other Asian export-led economies, such as South Korea, Singapore, and Malaysia.[20] China has emphasized raising personal income and consumption and introducing new management systems to help increase productivity. The government has also focused on foreign trade as a major vehicle for economic growth. The restructuring of the economy and resulting efficiency gains have contributed to a more than tenfold increase in GDP since 1978. Some economists believe that Chinese economic growth has been in fact understated during much of the 1990s and early 2000s, failing to fully factor in the growth driven by the private sector and that the extent at which China is dependent on exports is exaggerated despite the lack of full convertibility of the RMB.[21] Nevertheless, key bottlenecks continue to constrain growth. Available energy is insufficient to run at fully installed industrial capacity,[22] and the transport system is inadequate to move sufficient quantities of such critical items as coal.[23]

The two most important sectors of the economy have traditionally been agriculture and industry, which together employ more than 70 percent of the labor force and produce more than 60 percent of GDP. The two sectors have differed in many respects. Technology, labor productivity, and incomes have advanced much more rapidly in industry than in agriculture. Agricultural output has been vulnerable to the effects of weather, while industry has been more directly influenced by the government. The disparities between the two sectors have combined to form an economic-cultural-social gap between the rural and urban areas, which is a major division in Chinese society. China is the world's largest producer of rice and is among the principal sources of wheat, corn (maize), tobacco, soybeans, peanuts (groundnuts), and cotton. The country is one of the world's largest producers of a number of industrial and mineral products, including cotton cloth, tungsten, and antimony, and is an important producer of cotton yarn, coal, crude oil, and a number of other products. Its mineral resources are probably among the richest in the world but are only partially developed.

China has acquired highly sophisticated foreign production facilities and through "localization policies" also built a number of advanced engineering plants capable of manufacturing an increasing range of sophisticated equipment, including nuclear weapons and satellites, but most of its industrial output still comes from relatively ill-equipped factories. The technological level and quality standards of its industry as a whole are still disastrous,[24] notwithstanding a marked change since 2000, spurred in part by foreign investment. A report by UBS in 2009 concluded that China has experienced total factor productivity growth of 4 per cent per year since 1990, one of the fastest improvements in world economic history.[25]

China's increasing integration with the international economy and its growing efforts to use market forces to govern the domestic allocation of goods have exacerbated this problem. Over the years, large subsidies were built into the price structure, and these subsidies grew substantially in the late 1970s and 1980s.[26] By the early 1990s these subsidies began to be eliminated, in large part due to China's admission into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, which carried with it requirements for further economic liberalization and deregulation. China's ongoing economic transformation has had a profound impact not only on China but on the world. The market-oriented reforms China has implemented over the past two decades have unleashed individual initiative and entrepreneurship, whilst retaining state domination of the economy.

Wayne M. Morrison of the Congressional Research Service wrote in 2009 that "Despite the relatively positive outlook for its economy, China faces a number of difficult challenges that, if not addressed, could undermine its future economic growth and stability. These include pervasive government corruption, an inefficient banking system, over-dependence on exports and fixed investment for growth, the lack of rule of law, severe pollution, and widening income disparities."[27] Economic consultant David Smick adds that the recent actions by the Chinese government to stimulate their economy have only added to a huge industrial overcapacity and commercial real estate vacancy problems.[28]

China is one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, together with other emerging economies such as (Botswana) it has also sustained a healthy average growth rates of over 6% per annum for several decades, China's rapid-fire growth is as longer-lived as the Japanese counterpart in the 1960s to 1980s and is not showing signs of slowing. In China, as in other developing countries and emerging economies, growth has occurred across a vast population (nearly 1.3 billion), thus, liberating millions of people from poverty and unlocking massive segments of demand. In 2010, China was largest consumer of energy and accounted for 20.3%% of the global total.[29]. China also consumed 48% of the world's coal in 2010. As of 2011, China consumed 54% of the world's production of cement[30]

History

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Economic history of the People's Republic of China. (Discuss) (December 2010) |

Background: the rise and decline of the Middle Kingdom

Chinese civilization first arose in the valley of the Yellow River around 2200 BC. Because the soil of the valley was rich but the river treacherous, the people of the region developed sophisticated techniques of "permanent agriculture" that allowed them to control the volatile waters and cultivate high-yielding strains of rice. On these agricultural foundations China's population boomed, and a unique and durable social structure evolved. The core of society was the extended family, several generations of sons who together farmed the family plot. Daughters traditionally moved into their husband's families and were subservient to their mothers-in-law. Above the family level, peasant farmers grouped themselves into villages, which existed as nearly self-sufficient units.

By 1120 BC the people of the Yellow River valley had gathered under the loose authority of the Zhou Dynasty, a family of warrior priests who collected taxes and raised armies but otherwise stayed aloof from the life of the villages. Instead, the emperors and their bureaucrats devoted themselves to artistic and scholarly pursuits, nurturing a civilization that produced classic works of art and literature. as well as the great philosophers Confucius, Mencius, Han Fei Zi and Lao Zi.

Throughout this period, the core of China remained remarkably stable. It was largely an agricultural society, bound and nearly defined by Confucianism, a body of political and moral philosophy that taught the supreme importance of social stability. Starting at the level of the individual, it described a complex hierarchy of obedience, linking the child to its parent, the family to its ancestors, and the subject to his or her ruler. In all these relations, the patriarchal father was the center of authority, and filial piety was the most admired virtue. Because patterns of authority were repeated throughout the hierarchy, the emperor and his officials simply assumed the role of the father writ large. On a daily basis, meanwhile, order was maintained by the imperial bureaucrats, civil servants who were simultaneously a manifestation of the Confucian order and the physical means by which this order was preserved.

The Mongols conquered China in 1280, and so did the Manchus in 1644. Both of these cultures ruled and advanced China with a centralized hierarchy, an imperial bureaucracy, and a decided penchant for focusing their energies inward. For all practical purposes, therefore, China became a multicultural civilization before the middle of the 19th century, when the Westerns came to stay.

1949–1978

In 1949, China followed a socialist heavy industry development strategy, or the "Big Push" strategy. Consumption was reduced while rapid industrialization was given high priority. The government took control of a large part of the economy and redirected resources into building new factories. Entire new industries were arbitrarly created. An ill effort of creating economic growth was started. Tight control of budget and money supply reduced inflation by the end of 1950. Though most of it was done at the expense of suppressing the private sector of small to big businesses by the Three-anti/five-anti campaigns between 1951 to 1952. The campaigns were notorious for being anti-capitalist, and imposed charges that allowed the government to punish capitalists with severe fines.[31] In the beginning of the Communist party's rule, the leaders of the party had agreed that for a nation such as China, which does not have any heavy industry and minimal secondary production, capitalism is to be utilized to help the building of the "New China" and finally merged into communism.[32]

The proclamations of the PRC instantly transformed Mao Zedong and his followers from revolutionaries to administrators. With little experience in peacetime government or economic management, they faced two overwhelming tasks to organize and administer the world's largest society and to rebuild an economy devastated by decades of war. Both tasks failed within the first five years of communist rule.

Membership in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) grew rapidly during this time, and, in a structure reminiscent of the old imperial bureaucracy, a hierarchy of party organs was extended from the top echelons of CCP down to more than one million branch committee established in every village and township, factory, school, and government agency. The new government nationalized the country's banking system and brought all currency and credit under centralized control. It regulated prices by establishing trade associations and boosted government revenues by collecting agricultural taxes. By the mid-1950s, the communists had ruined the country's railroad and highway systems, barely brought the agricultural and industrial production to their prewar levels, by bringing the bulk of China's industry and commerce under the direct control of the state.

Meanwhile, in fulfillment of their revolutionary promise, China's communist leaders completed land reform within two years of coming to power. Party cadres visited local villages and incited the peasants in public "struggle meetings" to eliminate their landlords and redistribute their land and other possessions to peasant households. Shortly thereafter, the CCP encouraged rural households to form mutual aid teams, and then the agricultural producers' cooperatives which the government saw as the best means for increasing agricultural productivity. The devastating result was massive famine and death.

Mao Zedong tried in 1958 to push China's economy to new heights. Under his highly touted "Great Leap Forward", agricultural collectives were reorganized into enormous communes where men and women were assigned in military fashion to specific tasks. Peasants were told to stop relying on the family, and instead adopted a system of communal kitchens, mess halls, and nurseries. Wages were calculated along the communist principle of "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need", and sideline production was banned as incipient capitalism. All Chinese citizens were urged to boost the country's steel production by establishing "backyard steel furnaces" to help overtake the West. But while Mao believed that the politically directed outpouring of effort by China's vast population would result in economic development and miraculous production increases, the Great Leap Forward quickly revealed itself as a giant step backwards. Over-ambitious targets were set, falsified production figures were duly reported, and Chinese officials lived in an unreal world of miraculous production increases. Steel output did rise dramatically, but most of the steel was virtually useless. Even worse, it quickly became apparent that the peasants had made their steel by melting whatever metal they could find. By 1960, agricultural production in the countryside had slowed dangerously, and GNP declined by about one-third. The people were exhausted, and large areas of China were gripped by a devastating famine. By 1960, the situation had become so grave that not even Mao could ignore it. Quietly and without fanfare, Mao stepped to the sidelines, and pragmatists within the CCP, including Deng Xiaoping, began to do what was necessary to restore incentives and productions.

For the next several years, China experienced a period of relative stability. Agricultural and industrial production returned to normal levels, and labor productivity began to rise. Then, in 1966, Mao reasserted his power and again launched a scheme that nearly brought China to its knees. Worried lest Deng and other bureaucrats pull China too far from the spirit of its socialist revolution, Mao proclaimed a Cultural Revolution to "put China back on track". Under orders to "Destroy the Four Olds" (old thoughts, culture, customs and habits), universities and schools closed their doors, and students, who became Mao's "Red Guards", were sent throughout the country to make revolution, beating and torturing anyone whose rank or political thinking offended. Intellectuals were cursed as the "stinking ninth class", aand any sign of "capitalism", such as wearing a necktie, was enough to condemn someone as a foe of the Communist Party. Deng himself was purged as a "capitalist roader" and sent to work in a tractor factory.

By 1969 the country had descended into anarchy, and factions of the Red Guards had begun to fight among themselves. Finally, Mao called upon the army to restore order and sent his young guards to the countryside, where many became an embittered, uneducated, "lost" generation. In 1973, Mao quietly recalled Deng Xiaoping a Beijing.

1978–1990

After Mao's death in 1976, power passed quickly to the reform fraction of the CCP, led by Deng Xiaoping. Unlike Mao, Deng was a pragmatic leader, known less of his ideological commitment than his slogan: "Who cares if a cat is black or white, as long as it catches the mice." Once he consolidated his power, he began to put his pragmatic policies to work, determined to bring China back from the devastation that the Cultural Revolution had wrought.

Since 1978, China began to make major reforms to its economy. The Chinese leadership adopted a pragmatic perspective on many political and socioeconomic problems, and quickly began to introduce aspects of a capitalist economic system. Political and social stability, economic productivity, and public and consumer welfare were considered paramount and indivisible. In these years, the government emphasized raising personal income and consumption and introducing new management systems to help increase productivity. The government also had focused on foreign trade as a major vehicle for economic growth. In the 1980s, China tried to combine central planning with market-oriented reforms to increase productivity, living standards, and technological quality without exacerbating inflation, unemployment, and budget deficits. Reforms began in the agricultural, industrial, fiscal, financial, banking, price setting, and labor systems.[33]

A decision was made in 1978 to permit foreign direct investment in several small "special economic zones" along the coast.[34] The country lacked the legal infrastructure and knowledge of international practices to make this prospect attractive for many foreign businesses, however.[34] In the early 1980s steps were taken to expand the number of areas that could accept foreign investment with a minimum of red tape, and related efforts were made to develop the legal and other infrastructures necessary to make this work well.[35] This additional effort resulted in making 14 coastal cities and three coastal regions "open areas" for foreign investment. All of these places provide favored tax treatment and other advantages for foreign investment. Laws on contracts, patents, and other matters of concern to foreign businesses were also passed in an effort to attract international capital to spur China's development.[36] The largely bureaucratic nature of China's economy, however, posed a number of inherent problems for foreign firms that wanted to operate in the Chinese environment, and China gradually had to add more incentives to attract foreign capital.[37]

Phase One: reform in the countryside

When Deng came into power, China's vast peasantry was still organized in communes, work brigades, and production teams. Procurement prices were too low to cover even production costs, and ceilings were set on the amount of grain that producers could keep for consumption. Deng changed all that. He allowed farmers to produce on their own and sanctioned the sale of surplus production and other cash crops in newly freed markets. State procurement prices were raised, and prices for many agricultural goods were left to the dictates of the market. Beginning with the poor mountain areas of Anhui and then spreading across the country, Deng and his officials broke up the communes established by Mao and replaced them with a complicated system of leases that eventually brought effective land tenure back to the household level (even though ownership of land remained collective). The Household Responsibility System allowed peasants to lease land for a fixed period from the collective, provided they delivered to the collective a minimum quota of produce, usually basic grain. They could then sell any surplus they produced, either to the state at government procurement prices or on the newly free market. They were also free to retain any profits they might earn. Within a decade, grain production had grown by roughly 30%, and production of cotton, sugarcane, tobacco, and fruit had doubled.

Phase Two: rural industrialization and enterprise reform

As the reforms fueled production increases that surprised even the reformers, the scale of change grew bolder, and by the mid-1980s, the party leadership had begun the more complicated and politically delicate task of transforming the country's cumbersome system of central planning and state-owned enterprise. Prior to 1978, enterprises were almost all owned by the state in one form or another. At the top of each sector were the State-owned Enterprises (SOEs), answerable to the national government. Below these were other enterprises reporting to provincial, municipal, or county authorities. Private enterprises, meaning family-run shops, were not allowed until after 1978, and even then they were limited to seven employees.

China's SOEs were typical of large industrial firms in a centrally planned economy. Inefficient, overstaffed, and with outdated technology, they functioned not only as industrial units but also as social agencies, providing housing, daycare, education, and health care for the workers and their families. The largest enterprises included hundreds of thousands of employees, only a small proportion of whom were directly engaged in production.

The update of this system was that Chinese workers could expect both lifetime employment and an extensive, firm-based welfare system-the so-called "iron rice bowl". All welfare entitlements in this system were accounted for as costs of production and were deducted from revenues before the calculation of the profits that were to be remitted to the state. There was no national social security system because none was needed.

1990–2000

In the 1990s, the Chinese economy continued to grow at a rapid pace, at about 9.5%, accompanied by low inflation. The Asian financial crisis affected China at the margin, mainly through decreased foreign direct investment and a sharp drop in the growth of its exports. However, China had huge reserves, a currency that was not freely convertible, and capital inflows that consisted overwhelmingly of long-term investment. For these reasons it remained largely insulated from the regional crisis and its commitment not to devalue had been a major stabilizing factor for the region. However, China faced slowing growth and rising unemployment based on internal problems, including a financial system burdened by huge amounts of bad loans, and massive layoffs stemming from aggressive efforts to reform state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Despite China's impressive economic development during the past two decades, reforming the state sector and modernizing the banking system remained major hurdles. Over half of China's state-owned enterprises were inefficient and reporting losses. During the 15th National Communist Party Congress that met in September 1997, President Jiang Zemin announced plans to sell, merge, or close the vast majority of SOEs in his call for increased "non-public ownership" (feigongyou or privatization in euphemistic terms). The 9th National People's Congress endorsed the plans at its March 1998 session. In 2000, China claimed success in its three year effort to make the majority of large state owned enterprises (SOEs) profitable.

2000–2010

Following the Chinese Communist Party's Third Plenum, held in October 2003, Chinese legislators unveiled several proposed amendments to the state constitution. One of the most significant was a proposal to provide protection for private property rights. Legislators also indicated there would be a new emphasis on certain aspects of overall government economic policy, including efforts to reduce unemployment (now in the 8–10% range in urban areas), to rebalance income distribution between urban and rural regions, and to maintain economic growth while protecting the environment and improving social equity. The National People's Congress approved the amendments when it met in March 2004.[38]

The Fifth Plenum in October 2005 approved the 11th Five-Year Economic Program (2006–2010) aimed at building a "harmonious society" through more balanced wealth distribution and improved education, medical care, and social security. On March 2006, the National People's Congress approved the 11th Five-Year Program. The plan called for a relatively conservative 45% increase in GDP and a 20% reduction in energy intensity (energy consumption per unit of GDP) by 2010.

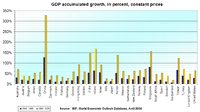

China's economy grew at an average rate of 10% per year during the period 1990–2004, the highest growth rate in the world. China's GDP grew 10.0% in 2003, 10.1%, in 2004, and even faster 10.4% in 2005 despite attempts by the government to cool the economy. China's total trade in 2010 surpassed $2.97 trillion, making China the world's second-largest trading nation after the U.S. Such high growth is necessary if China is to generate the 15 million jobs needed annually—roughly the size of Ecuador or Cambodia—to employ new entrants into the national job market.

On January 14, 2009, as confirmed by the World Bank[39] the NBS published the revised figures for 2007 fiscal year in which growth happened at 13 percent instead of 11.9 percent (provisional figures). China's gross domestic product stood at US$3.38 trillion while Germany's GDP was USD $3.32 trillion for 2007. This made China the world's third largest economy by gross domestic product.[40] Based on these figures, in 2007 China recorded its fastest growth since 1994 when the GDP grew by 13.1 percent.[41]

China launched its Economic Stimulus Plan to specifically deal with the Global financial crisis of 2008–2009. It has primarily focused on increasing affordable housing, easing credit restrictions for mortgage and SMEs, lower taxes such as those on real estate sales and commodities, pumping more public investment into infrastructure development, such as the rail network, roads and ports. By the end of 2009 it appeared that the Chinese economy was showing signs of recovery. At the 2009 Economic Work Conference in December 'managing inflation expectations' was added to the list of economic objectives, suggesting a strong economic upturn and a desire to take steps to manage it.[42]

2010–present

see also : Economy of the PRC: Noopolitik and the Knowledge Economy

By 2010 it was evident to outside observers such as The New York Times that China was poised to move from export dependency to development of an internal market. Wages were rapidly rising in all areas of the country and Chinese leaders were calling for an increased standard of living.[43]

In 2010, China's GDP was valued at $5.87 trillion, surpassed Japan's $5.47 trillion, and became the world's second largest economy after the U.S.[44] China could become the world's largest economy (by nominal GDP) sometime as early as 2020.[45]

China is the largest creditor nation in the world[citation needed] and owns approximately 20.8% of all foreign-owned US Treasury securities.[46]

It has also appeared that Noopolitik and the knowledge economy had become salient interests of the PRC's economic policy across the 2000s, through which the country made clear its move from "Made in China" to "Innovated in China" as notes Adam Segal.[47] Idriss Aberkane thus argued "With China’s cosmopolitan and highly educated diaspora, it is no surprise that as of 2010, five of the top twenty most visited websites in the world are indexed in Mandarin. They include PRC-born behemoths such as Baidu.com, Taobao.com, and Sina.com.cn, and video sharing Tudou.com, which has gained users in both North America and Europe." [48]

Government role

Since 1949 the government, under socialist political and economic system, has been responsible for planning and managing the national economy.[49] In the early 1950s, the foreign trade system was monopolized by the state. Nearly all the domestic enterprises were state-owned and the government had set the prices for key commodities, controlled the level and general distribution of investment funds, determined output targets for major enterprises and branches, allocated energy resources, set wage levels and employment targets, operated the wholesale and retail networks, and steered the financial policy and banking system. In the countryside from the mid-1950s, the government established cropping patterns, set the level of prices, and fixed output targets for all major crops.

Since 1978 when economic reforms were instituted, the government's role in the economy has lessened by a great degree. Industrial output by state enterprises slowly declined, although a few strategic industries, such as the aerospace industry have today remained predominantly state-owned. While the role of the government in managing the economy has been reduced and the role of both private enterprise and market forces increased, the government maintains a major role in the urban economy. With its policies on such issues as agricultural procurement the government also retains a major influence on rural sector performance. The State Constitution of 1982 specified that the state is to guide the country's economic development by making broad decisions on economic priorities and policies, and that the State Council, which exercises executive control, was to direct its subordinate bodies in preparing and implementing the national economic plan and the state budget. A major portion of the government system (bureaucracy) is devoted to managing the economy in a top-down chain of command with all but a few of the more than 100 ministries, commissions, administrations, bureaus, academies, and corporations under the State Council are concerned with economic matters.

Each significant economic sector is supervised by one or more of these organizations, which includes the People's Bank of China, National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Finance, and the ministries of agriculture; coal industry; commerce; communications; education; light industry; metallurgical industry; petroleum industry; railways; textile industry; and water resources and electric power. Several aspects of the economy are administered by specialized departments under the State Council, including the National Bureau of Statistics, Civil Aviation Administration of China, and the tourism bureau. Each of the economic organizations under the State Council directs the units under its jurisdiction through subordinate offices at the provincial and local levels.

The whole policy-making process involves extensive consultation and negotiation.[50] Economic policies and decisions adopted by the National People's Congress and the State Council are to be passed on to the economic organizations under the State Council, which incorporates them into the plans for the various sectors of the economy. Economic plans and policies are implemented by a variety of direct and indirect control mechanisms. Direct control is exercised by designating specific physical output quotas and supply allocations for some goods and services. Indirect instruments—also called "economic levers"—operate by affecting market incentives. These included levying taxes, setting prices for products and supplies, allocating investment funds, monitoring and controlling financial transactions by the banking system, and controlling the allocation of key resources, such as skilled labor, electric power, transportation, steel, and chemicals (including fertilizers). The main advantage of including a project in an annual plan is that the raw materials, labor, financial resources, and markets are guaranteed by directives that have the weight of the law behind them. In reality, however, a great deal of economic activity goes on outside the scope of the detailed plan, and the tendency has been for the plan to become narrower rather than broader in scope. A major objective of the reform program was to reduce the use of direct controls and to increase the role of indirect economic levers. Major state-owned enterprises still receive detailed plans specifying physical quantities of key inputs and products from their ministries. These corporations, however, have been increasingly affected by prices and allocations that were determined through market interaction and only indirectly influenced by the central plan.

Total economic enterprise in China is apportioned along lines of directive planning (mandatory), indicative planning (indirect implementation of central directives), and those left to market forces. In the early 1980s during the initial reforms enterprises began to have increasing discretion over the quantities of inputs purchased, the sources of inputs, the variety of products manufactured, and the production process. Operational supervision over economic projects has devolved primarily to provincial, municipal, and county governments. The majority of state-owned industrial enterprises, which were managed at the provincial level or below, were partially regulated by a combination of specific allocations and indirect controls, but they also produced goods outside the plan for sale in the market. Important, scarce resources—for example, engineers or finished steel—may have been assigned to this kind of unit in exact numbers. Less critical assignments of personnel and materials would have been authorized in a general way by the plan, but with procurement arrangements left up to the enterprise management.

In addition, enterprises themselves are gaining increased independence in a range of activity. While strategically important industry and services and most of large-scale construction have remained under directive planning, the market economy has gained rapidly in scale every year as it subsumes more and more sectors.[51] Overall, the Chinese industrial system contains a complex mixture of relationships. The State Council generally administers relatively strict control over resources deemed to be of vital concern for the performance and health of the entire economy. Less vital aspects of the economy have been transferred to lower levels for detailed decisions and management. Furthermore, the need to coordinate entities that are in different organizational hierarchies generally causes a great deal of informal bargaining and consensus building.[51]

Consumer spending has been subject to a limited degree of direct government influence but is primarily determined by the basic market forces of income levels and commodity prices. Before the reform period, key goods were rationed when they were in short supply, but by the mid-1980s availability had increased to the point that rationing was discontinued for everything except grain, which could also be purchased in the free markets. Collectively owned units and the agricultural sector were regulated primarily by indirect instruments. Each collective unit was "responsible for its own profit and loss," and the prices of its inputs and products provided the major production incentives.

Vast changes were made in relaxing the state control of the agricultural sector from the late 1970s. The structural mechanisms for implementing state objectives—the people's communes and their subordinate teams and brigades—have been either entirely eliminated or greatly diminished.[52] Farm incentives have been boosted both by price increases for state-purchased agricultural products, and it was permitted to sell excess production on a free market. There was more room in the choice of what crops to grow, and peasants are allowed to contract for land that they will work, rather than simply working most of the land collectively. The system of procurement quotas (fixed in the form of contracts) has been being phased out, although the state can still buy farm products and control surpluses in order to affect market conditions.[53]

Foreign trade is supervised by the Ministry of Commerce, customs, and the Bank of China, the foreign exchange arm of the Chinese banking system, which controls access to the foreign currency required for imports. Ever since restrictions on foreign trade were reduced, there have been broad opportunities for individual enterprises to engage in exchanges with foreign firms without much intervention from official agencies.

Though private sector companies still dominate small and medium sized businesses, the government still plays a large part in the bigger industries. The fact that government accounts for a third of the GDP shows this. Foreign owned companies hold significant stakes. The public sector is mainly made up of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs).

Purely on economic grounds, therefore, China has become a phenomenon. It is the second-largest economy in the world and has frequently been described as likely, within a decade, to surpass both the European Union and the United States in total GDP. Under the leadership of President Hu Jintao, the Chinese Communist Party has retained full control of the country's affairs and remained firmly committed to many of socialism's key tenets. All of the country's major banks, for example, remained tightly linked to the state, as do key sectors such as oil, petrochemicals, and steel. State agencies have provided most of the country's still-limited financial services, and state-owned enterprises produced more than one-third of total output. Indeed, the state-and the Party-were central players in nearly all aspects of China's economy, guiding a development trajectory often labeled as "socialism with Chinese characteristics".

Regional economies

China's unequal transportation system—combined with important differences in the availability of natural and human resources and in industrial infrastructure—has produced significant variations in the regional economies of China.

Economic development has generally been more rapid in coastal provinces than in the interior, and there are large disparities in per capita income between regions. The three wealthiest regions are along the southeast coast, centred on the Pearl River Delta; along the east coast, centred on the Lower Yangtze River; and near the Bohai Gulf, in the Beijing–Tianjin–Liaoning region. It is the rapid development of these areas that is expected to have the most significant effect on the Asian regional economy as a whole, and Chinese government policy is designed to remove the obstacles to accelerated growth in these wealthier regions.

- See also: List of administrative regions by GDP, List of administrative regions by GDP per capita, and List of cities by GDP per capita.

Development

- See also: List of administrative divisions by Human Development Index (HDI).

China, economically frail before 1978, has again become one of the world's major economic powers with the greatest potential. In the 22 years following reform and opening-up in 1979 in particular, China's economy developed at an unprecedented rate, and that momentum has been held steady into the 21st century.

China adopts the "five-year-plan" strategy for economic development. The Twelfth Five-Year Plan (2011–2015) is currently being implemented.

It was not an obvious path to growth. But for nearly 30 years China had indeed been growing, thrusting its citizens into prosperity and its goods across the world. Between 1978 and 2005, China's per capita GDP had grown from $153 to $1284, while its current account surplus had increased over twelve-fold between 1982 and 2004, from $5.7 billion to $71 billion. During this time, China had also become an industrial powerhouse, moving beyond initial successes in low-wage sectors like clothing and footwear to the increasingly sophisticated production of computers, pharmaceuticals, and automobiles.

Just how long the trajectory could continue, however, remained unclear. According to the 11th five-year plan, China needed to sustain an annual growth rates of 8% for the foreseeable future. Only with such levels of growth, the leadership argued, could China continue to develop its industrial prowess, raise its citizen's standard of living, and redress the inequalities that were cropping up across the country. Yet no country had ever before maintained the kind of growth that China was predicting. Moreover, China had to some extent already undergone the easier parts of development. In the 1980s, it had transformed its vast and inefficient agricultural sector, freeing its peasants from the confines of central planning and winning them to the cause of reform. In the 1990s, it had likewise started to restructure its stagnant industrial sector, wooing foreign investors for the first time. These policies had catalysed the country's phenomenal growth. Instead, China had to take what many regarded as the final step toward the market, liberalizing the banking sector and launching the beginnings of a real capital market.

This step, however, would not be easy. As of 2004, China's state-owned enterprises were still only partially reorganized, and its banks were dealing with the burden of over $205 billion (1.7 trillion RMB) in non-performing loans, monies that had little chance of ever being repaid. The country had a floating exchange rate, and strict controls on both the current and capital accounts.

Regional development

| ||

| The East Coast (w/ existing development programmes) | ||

| "Rise of Central China" | ||

| "Revitalize Northeast China" | ||

| "China Western Development" | ||

These strategies are aimed at the relatively poorer regions in China in an attempt to prevent widening inequalities:

- China Western Development, designed to increase the economic situation of the western provinces through capital investment and development of natural resources.

- Revitalize Northeast China, to rejuvenate the industrial bases in Northeast China. It covers the three provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning, as well as the five eastern prefectures of Inner Mongolia.

- Rise of Central China Plan, to accelerate the development of its central regions. It covers six provinces: Shanxi, Henan, Anhui, Hubei, Hunan, and Jiangxi.

- Third Front, focused on the southwestern provinces.

Foreign investment abroad:

- Go Global, to encourage its enterprises to invest overseas.

Key national projects

The "West-to-East Electricity Transmission," the "West-to-East Gas Transmission," and the "South–North Water Transfer Project" are the government's three key strategic projects, aimed at realigning overall economic development and achieving rational distribution of national resources across China. The "West-to-East Electricity Transmission" project is in full swing, involving hydropower and coal resources in western China and the construction of new power transmission channels to deliver electricity to the east. The southern power grid line, transmitting three million kW from Guizhou to Guangdong, was completed in September 2004. The "West-to-East Gas Transmission" project includes a 4,000 km trunk pipeline running through 10 provinces, autonomous regions or municipalities, conveying natural gas to cities in northern and eastern China. This was finished in October 2004 and has a design capacity of 12 billion cu m per year. Construction of the "South-to-North Water Diversion" project was officially launched on 27 December 2002 and completion of Phase I is scheduled for 2010; this will relieve serious water shortfall in northern China and realize a rational distribution of the water resources of the Yangtze, Yellow, Huaihe, and Haihe river valleys.

Hong Kong and Macau

In accordance with the One Country, Two Systems policy, the economies of the former European colonies, Hong Kong and Macao, are separate from the rest of the PRC, and each other. Both Hong Kong and Macau are free to conduct and engage in economic negotiations with foreign countries, as well as participating as full members in various international economic organizations such as the World Customs Organization, the World Trade Organization and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, often under the names "Hong Kong, China" and "Macao, China".

- See also: Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement with Hong Kong and Macau.

Macroeconomic trends

In January 1985, the State Council of China approved to establish a SNA (System of National Accounting), use the gross domestic product (GDP) to measure the national economy. China started the study of theoretical foundation, guiding, and accounting model etc., for establishing a new system of national economic accounting. In 1986, as the first citizen of the People's Republic of China to receive a Ph.D. in economics from an overseas country, Dr. Fengbo Zhang headed Chinese Macroeconomic Research - the key research project of the seventh Five-Year Plan of China, as well as completing and publishing the China GDP data by China's own research. The summary of the above has been included in the book Chinese Macroeconomic Structure and Policy (1988) Editor: Fengbo Zhang, collectively authored by the Research Center of the State Council of China. This is the first GDP data which was published by China. The State Council of China issued “The notice regarding implementation of System of National Accounting” in August 1992, the SNA system officially is introduced to China, replaced Soviet Union's MPS system, Western economic indicator GDP became China’s most important economic indicator (WikiChina: China GDP, The First China GDP).

The table below shows the trend of the GDP of China at market prices estimated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) with figures in millions (Chinese yuan).[54][55] See also.[56] For purchasing power parity comparisons, the US dollar is exchanged at 2.05 CNY only.

| Year | Gross domestic product | US dollar exchange | Inflation index (2000=100) |

Nominal Per Capita GDP (as % of USA) |

PPP Per Capita GDP (as % of USA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1955 | 91,000 | 2.46 | 19.2 | 2.43 | - |

| 1960 | 145,700 | 2.46 | 20.0 | 3.04 | - |

| 1965 | 171,600 | 2.46 | 21.6 | 2.63 | - |

| 1970 | 225,300 | 2.46 | 21.3 | 2.20 | - |

| 1975 | 299,700 | 1.86 | 22.4 | 2.32 | - |

| 1980 | 460,906 | 1.49 | 25.0 | 2.52 | 2.04 |

| 1985 | 896,440 | 2.93 | 30.0 | 1.65 | 2.84 |

| 1990 | 1,854,790 | 4.78 | 49.0 | 1.48 | 3.43 |

| 1995 | 6,079,400 | 8.35 | 91.0 | 2.17 | 5.44 |

| 2000 | 9,921,500 | 8.27 | 100.0 | 2.69 | 6.75 |

| 2005 | 18,308,500 | 8.19 | 106.0 | 4.05 | 9.61 |

| 2010 | 25,506,956 | 6.97 | 112.0 | 6.23 | 15.90 |

Systemic problems

The government has in recent years struggled to contain the social strife and environmental damage related to the economy's rapid transformation; collect public receipts due from provinces, businesses, and individuals; reduce corruption and other economic crimes; sustain adequate job growth for tens of millions of workers laid off from state-owned enterprises, migrants, and new entrants to the work force; and keep afloat the large state-owned enterprises, most of which had not participated in the vigorous expansion of the economy and many of which had been losing the ability to pay full wages and pensions. From 50 to 100 million surplus rural workers were adrift between the villages and the cities, many subsisting through part-time low-paying jobs. Popular resistance, changes in central policy, and loss of authority by rural cadres have weakened China's population control program. Another long-term threat to continued rapid economic growth has been the deterioration in the environment, notably air and water pollution, soil erosion, growing desertification and the steady fall of the water table especially in the north. China also has continued to lose arable land because of erosion and infrastructure development.

Other major problems concern the labor force and the pricing system. There is large-scale underemployment in both urban and rural areas, and the fear of the disruptive effects of major, explicit unemployment is strong. The prices of certain key commodities, especially of industrial raw materials and major industrial products, are determined by the state. In most cases, basic price ratios were set in the 1950s and are often irrational in terms of current production capabilities and demands. Over the years, large subsidies were built into the price structure, and these subsidies grew substantially in the late 1970s and 1980s.[26] By the early 1990s these subsidies began to be eliminated, in large part due to China's admission into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, which carried with it requirements for further economic liberalization and deregulation. China's ongoing economic transformation has had a profound impact not only on China but on the world. The market-oriented reforms China has implemented over the past two decades have unleashed individual initiative and entrepreneurship.

By 2010, rapidly rising wages and a general increase in the standard of living had put increased energy use on a collision course with the need to reduce carbon emissions in order to control global warming. There were diligent efforts to increase energy efficiency and increase use of renewable sources; over 1,000 inefficient power plants had been closed, but projections continued to show a dramatic rise in carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels.[57]

Regulatory environment

Though China's economy has expanded rapidly, its regulatory environment has not kept pace. Since Deng Xiaoping's open market reforms, the growth of new businesses has outpaced the government's ability to regulate them. This has created a situation where businesses, faced with mounting competition and poor oversight, take drastic measures to increase profit margins, often at the expense of consumer safety. This issue became more prominent in 2007, with a number of restrictions being placed on problematic Chinese exports by the United States.[58]

Inflation

During the winter of 2007–2008, inflation ran about 7% on an annual basis, rising to 8.7% in statistics for February 2008, released in March 2008.[59][60][61]

Shortages of gasoline and diesel fuel developed in the fall of 2007 due to reluctance of refineries to produce fuel at low prices set by the state. These prices were slightly increased in November 2007 with fuel selling for $2.65 a gallon, still slightly below world prices. Price controls were in effect on numerous basic products and services, but were ineffective with food, prices of which were rising at an annual rate of 18.2% in November 2007.[62][63] The problem of inflation has caused concern at the highest levels of the Chinese government. On January 9, 2008, the government of China issued the following statement on its official website: "The Chinese government decided on Wednesday to take further measures to stabilize market prices and increase the severity of punishments for those guilty of driving up prices through hoarding or cheating."[64][65]

Pork is an important part of the Chinese economy with a per capita consumption of a fifth of a pound per day. The worldwide rise in the price of animal feed associated with increased production of ethanol from corn resulted in steep rises in pork prices in China in 2007. Increased cost of production interacted badly with increased demand resulting from rapidly rising wages. The state responded by subsidizing pork prices for students and the urban poor and called for increased production. Release of pork from the nation's strategic pork reserve was considered.[66]

By January 2008, the inflation rate rose to 7.1%, which BBC News described as the highest inflation rate since 1997, due to the winter storms that month.[67] China's inflation rate jumped to a new decade high of 8.7 percent in February 2008 after severe winter storms disrupted the economy and worsened food shortages, the government said March 11, 2008.[68]

Throughout the summer and fall, however, inflation fell again to a low of 6.6% in October 2008.[69]

By November 2010, the inflation rate rose up to 5.1%, driven by a 11.7% increase in food prices year on year. According to the bureau, industrial output went up 13.3 percent. As supplies have run short, prices for fuel and other commodities have risen up.[70]

Labor shortages and rising export costs

- See also: Labor section below.

By 2005, there were signs of stronger demand for workers being able to choose employment that offered higher wages and better working conditions, enabling some to move away from the restrictive dormitory life and boring marige work that have characterized export industries in provinces such as Guangdong and Fujian. Minimum wages began rising toward the equivalent of 100 U.S. dollars a month as companies scrambled for employees, with some paying as much as $150 a month on average. The labor shortage was partially driven by the demographic trends, as the proportion of people of working age fell as the result of strict family planning.[71]

It was reported in The New York Times in April 2006 that labor costs continued to increase and a shortage of unskilled labor had developed with a million or more employees being sought. Operations that relied on cheap labor were contemplating relocations to cities in the interior or to other low-cost countries such as Vietnam or Bangladesh. Many young people were attending college rather than opting for minimum-wage factory work. The demographic shift resulting from the one-child policy continued to reduce the supply of young entry-level workers. Also, government efforts to advance economic development in the interior of the country were beginning to be effective at creating better opportunities there.[72] A follow-up article in The New York Times in late August 2007 reported acceleration of this trend. The minimum wage a young unskilled factory worker could be hired at had increased to $200 with experienced workers commanding more. There was strong demand for young workers willing to work long hours and live in dormitory conditions, while older workers, over forty, were considered unsuitable.

Rising wages were being, to a certain extent, offset by increases in productivity, but in 2007, a slight rise in the cost of imports from China was recorded by the United States government: "After falling since its inception in December 2003, the price index for imports from China rose 0.4 percent in July 2007, the largest monthly increase since the index was first published in December 2003. The July increase was the third consecutive monthly advance. Over the past year, import prices from China increased 0.9 percent."[73][74] By February 2008, concerns were being raised that rising wages and inflation in China were beginning to create inflationary pressure in the United States and Europe, which had depended on cheap prices for consumer goods from China exerting downward pressure on prices.[75]

On January 1, 2008, China introduced a new Labor Law, increasing the rights of the workforce, this caused many foreign and private companies, whose operations in China were based on low wages, to move to countries with lower labor costs, like Thailand, Vietnam or Bangladesh. In the summer of 2008 the growth in export orders began to fall sharply as the sub-prime crisis in export markets reduced demand in Guangdong province, particularly in toy and textile manufacture. According to Chinese Government sources 20 million jobs in 67,000 factories were reported to have been lost.[76] The government initially was happy to see factories close down in labour intensive low wage factories, and the Labor law was seen as a means of helping to eradicate them, but the global financial crisis led to a far more rapid process of private sector collapse in Guangdong than was expected, raising fears of a contagious spread of social unrest.

In early 2010 a labor shortage developed in coastal areas with many migrant workers not returning after the new year holiday. Wages rose rapidly with temp agencies charging over $1.00 US per hour for factory workers in Guangzhou.[77] Following the strikes in 2010 at Japanese auto plants, the shortage continued with many factories unable to fully staff their factories.[78]

According to Fan Gang, professor of economics at Beijing University and director of China’s National Economic Research Institute, due to the large volume of workers engaged in relatively unremunerative agricultural work there is considerable room for increased nominal wages in China without changing the competitive position of the Chinese export industry for the next few decades. Lower wages in other countries may not represent productivity comparable to the increasing productivity of Chinese workers.[79]

Financial and banking system

Most of China's financial institutions are state owned and governed and 98% of banking assets are state owned.[80] The chief instruments of financial and fiscal control are the People's Bank of China (PBC) and the Ministry of Finance, both under the authority of the State Council. The People's Bank of China replaced the Central Bank of China in 1950 and gradually took over private banks. It fulfills many of the functions of other central and commercial banks. It issues the currency, controls circulation, and plays an important role in disbursing budgetary expenditures. Additionally, it administers the accounts, payments, and receipts of government organizations and other bodies, which enables it to exert thorough supervision over their financial and general performances in consideration to the government's economic plans. The PBC is also responsible for international trade and other overseas transactions. Remittances by overseas Chinese are managed by the Bank of China (BOC), which has a number of branch offices in several countries.

Other financial institutions that are crucial, include the China Development Bank (CDB), which funds economic development and directs foreign investment; the Agricultural Bank of China (ABC), which provides for the agricultural sector; the China Construction Bank (CCB), which is responsible for capitalizing a portion of overall investment and for providing capital funds for certain industrial and construction enterprises; and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), which conducts ordinary commercial transactions and acts as a savings bank for the public.

China's economic reforms greatly increased the economic role of the banking system. In theory any enterprises or individuals can go to the banks to obtain loans outside the state plan, in practice 75% of state bank loans go to State Owned Enterprises. (SOEs)[81] Even though nearly all investment capital was previously provided on a grant basis according to the state plan, policy has since the start of the reform shifted to a loan basis through the various state-directed financial institutions. Increasing amounts of funds are made available through the banks for economic and commercial purposes. Foreign sources of capital have also increased. China has received loans from the World Bank and several United Nations programs, as well as from countries (particularly Japan) and, to a lesser extent, commercial banks. Hong Kong has been a major conduit of this investment, as well as a source itself.

With two stock exchanges (Shanghai Stock Exchange and Shenzhen Stock Exchange), mainland China's stock market had a market value of $1 trillion by January 2007, which became the third largest stock market in Asia, after Japan and Hong Kong.[82] It is estimated to be the world's third largest by 2016.[83]

Currency system

The renminbi ("people's currency") is the currency of China, denominated as the yuan, subdivided into 10 jiao or 100 fen. The renminbi is issued by the People's Bank of China, the monetary authority of the PRC. The ISO 4217 abbreviation is CNY, although also commonly abbreviated as "RMB". The Latinised symbol is ¥. The yuan is generally considered by outside observers to be undervalued by about 30-40%.[84][85]

The renminbi is held in a floating exchange-rate system managed primarily against the US dollar. On July 21, 2005, China revalued its currency by 2.1% against the US dollar and, since then has moved to an exchange rate system that references a basket of currencies and has allowed the renminbi to fluctuate at a daily rate of up to half a percent.

The rate of exchange (Chinese yuan per US$1) on July 31, 2008, was RMB 6.846, in mid-2007 was RMB 7.45, while in early 2006 was RMB 8.07:US $1=8.2793 yuan (January 2000), 8.2783 (1999), 8.2790 (1998), 8.2898 (1997), 8.3142 (1996), 8.3514 (1995).

There is a complex relationship between China's balance of trade, inflation, measured by the consumer price index and the value of its currency. Despite allowing the value of the yuan to "float", China's central bank has decisive ability to control its value with relationship to other currencies. Inflation in 2007, reflecting sharply rising prices for meat and fuel, is probably related to the worldwide rise in commodities used as animal feed or as fuel. Thus rapid rises in the value of the yuan permitted in December 2007 are possibly related to efforts to mitigate inflation by permitting the renminbi to be worth more.[86] 222

Tax system

From the 1950s to the 1980s, the central government's revenues derived chiefly from the profits of the state enterprises, which were remitted to the state. Some government revenues also came from taxes, of which the most important was the general industrial and commercial tax.

The trend, however, has been for remitted profits of the state enterprises to be replaced with taxes on those profits. Initially, this tax system was adjusted so as to allow for differences in the capitalization and pricing situations of various firms, but more-uniform tax schedules were introduced in the early 1990s. In addition, personal income and value-added taxes were implemented at that time.

Agriculture

China is the world's largest producer and consumer of agricultural products – and some 300 million Chinese farm workers are in the industry, mostly laboring on pieces of land about the size of U.S farms. Virtually all arable land is used for food crops. China is the world's largest producer of rice and is among the principal sources of wheat, corn (maize), tobacco, soybeans, potatoes, sorghum, peanuts, tea, millet, barley, oilseed, pork, and fish. Major non-food crops, including cotton, other fibers, and oilseeds, furnish China with a small proportion of its foreign trade revenue. Agricultural exports, such as vegetables and fruits, fish and shellfish, grain and meat products, are exported to Hong Kong. Yields are high because of intensive cultivation, for example, China's cropland area is only 75% of the U.S. total, but China still produces about 30% more crops and livestock than the United States. China hopes to further increase agricultural production through improved plant stocks, fertilizers, and technology.

According to the government statistics issued in 2005,[87] after a drop in the yield of farm crops in 2000, output has been increasing annually.

According to the United Nations World Food Program, in 2003, China fed 20 percent of the world's population with only 7 percent of the world's arable land.[88] China ranks first worldwide in farm output, and, as a result of topographic and climatic factors, only about 10–15 percent of the total land area is suitable for cultivation. Of this, slightly more than half is unirrigated, and the remainder is divided roughly equally between paddy fields and irrigated areas. Nevertheless, about 60 percent of the population lives in the rural areas, and until the 1980s a high percentage of them made their living directly from farming. Since then, many have been encouraged to leave the fields and pursue other activities, such as light manufacturing, commerce, and transportation; and by the mid-1980s farming accounted for less than half of the value of rural output. Today, agriculture contributes only 13% of China's GDP.

Animal husbandry constitutes the second most important component of agricultural production. China is the world's leading producer of pigs, chickens, and eggs, and it also has sizable herds of sheep and cattle. Since the mid-1970s, greater emphasis has been placed on increasing the livestock output. China has a long tradition of ocean and freshwater fishing and of aquaculture. Pond raising has always been important and has been increasingly emphasized to supplement coastal and inland fisheries threatened by overfishing and to provide such valuable export commodities as prawns.

Environmental problems such as floods, drought, and erosion pose serious threats to farming in many parts of the country. The wholesale destruction of [[fores gave way to an energetic reforestation program that proved inadequate, and forest resources are still fairly meagre.[89] The principal forests are found in the Qinling Mountains and the central mountains and on the Sichuan–Yunnan plateau. Because they are inaccessible, the Qinling forests are not worked extensively, and much of the country's timber comes from Heilongjiang, Jilin, Sichuan, and Yunnan.

Western China, comprising Tibet, Xinjiang, and Qinghai, has little agricultural significance except for areas of floriculture and cattle raising. Rice, China's most important crop, is dominant in the southern provinces and many of the farms here yield two harvests a year. In the north, wheat is of the greatest importance, while in central China wheat and rice vie with each other for the top place. Millet and kaoliang (a variety of grain sorghum) are grown mainly in the northeast and some central provinces, which, together with some northern areas, also provide considerable quantities of barley. Most of the soybean crop is derived from the north and the northeast; corn (maize) is grown in the center and the north, while tea comes mainly from the warm and humid hilly areas of the south. Cotton is grown extensively in the central provinces, but it is also found to a lesser extent in the southeast and in the north. Tobacco comes from the center and parts of the south. Other important crops are potatoes, sugar beets, and oilseeds.

There is still a relative lack of agricultural machinery, particularly advanced machinery. For the most part the Chinese peasant or farmer depends on simple, nonmechanized farming implements. Good progress has been made in increasing water conservancy, and about half the cultivated land is under irrigation.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, economic reforms were introduced. First of all this began with the shift of farming work to a system of household responsibility and a phasing out of collectivized agriculture. Later this expanded to include a gradual liberalization of price controls; fiscal decentralization; massive privatization of state enterprises, thereby allowing a wide variety of private enterprises in the services and light manufacturing; the foundation of a diversified banking system (but with large amounts of state control); the development of a stock market; and the opening of the economy to increased foreign trade and foreign investment.

Energy and mineral resources

Energy

Electricity:

- production: 2.8344 trillion kWh (2006)

- consumption: 2.8248 trillion kWh (2006)

- exports: 11.19 billion kWh (2005)

- imports: 5.011 billion kWh (2005)

Electricity – production by source:

- thermal: 77.8% (68.7% from coal) (2006)

- hydro: 20.7% (2006)

- other: 0.4% (2006)

- nuclear: 1.1% (2006)

Oil:

- production: 3,631,000 bbl/d (577,300 m3/d) (2005)

- consumption: 6,534,000 bbl/d (1,038,800 m3/d) (2005) and expected 9,300,000 bbl/d (1,480,000 m3/d) in 2030

- exports: 443,300 bbl/d (70,480 m3/d) (2005)

- imports: 3,181,000 bbl/d (505,700 m3/d) (2005)

- net imports: 2,740,000 barrels per day (436,000 m3/d) (2005)

- proved reserves: 16.3 Gbbl (2.59×109 m3) (1 January 2006)

Natural gas:

- production: 47.88 km3 (2005 est.)

- consumption: 44.93 km3 (2005 est.)

- exports: 2.944 km3 (2005)

- imports: 0 m3 (2005)

- proved reserves: 1,448k m3 (1 January 2006 est.)

Since 1980, China's energy production has grown dramatically, as has the proportion allocated to domestic consumption. Some 80 percent of all power generated from fossil fuel at thermal plants, with about 17 percent at hydroelectric installations; only about two percent is from nuclear energy, mainly from plants located in Guangdong and Zhejiang.[90] Though China has rich overall energy potential, most have yet to be developed. In addition, the geographical distribution of energy puts most of these resources relatively far from their major industrial users. Basically the northeast is rich in coal and oil, the central part of north China has abundant coal, and the southwest has immense hydroelectric potential. But the industrialized regions around Guangzhou and the Lower Yangtze region around Shanghai have too little energy, while there is relatively little heavy industry located near major energy resource areas other than in the southern part of the northeast.

Although electric-generating capacity has grown rapidly, it has continued to fall considerably short of demand. This has been partly because energy prices were long fixed so low that industries had few incentives to conserve. In addition, it has often been necessary to transport fuels (notably coal) great distances from points of production to consumption. Coal provides about 70–75 percent of China's energy consumption, although its proportion has been gradually declining. Petroleum production, which grew rapidly from an extremely low base in the early 1960s, has increased much more gradually from 1980. Natural gas production still constitutes only a small (though increasing) fraction of overall energy production, but gas is supplanting coal as a domestic fuel in the major cities.

In the 1990s, energy demand rocketed in response to the rapid expansion of the economy but energy production was constrained by limited capital. As in other sectors of the state-owned economy, the energy sector suffered from low utilization and inefficiencies in production, transport, conversion, consumption, and conservation. Other problems included declining real prices, rising taxes and production costs, spiraling losses, high debt burden, insufficient investment, low productivity, poor management structure, environmental pollution, and inadequate technological development. To keep pace with demand, China sought to increase electric generating capacity to a target level of 290 gigawatts by 2000.

According to Chinese statistics, China managed to keep its energy growth rate at just half the rate of GDP growth throughout the 1990s. Though these numbers are not reliable, there has been agreement that China had improved its energy efficiency significantly over this period. In the late 1990s, an estimated 10,000 megawatts of generating capacity was added each year, at an annual cost of about $15 billion. China imported new power plants from the West to increase its generation capacity, and these units then accounted for approximately 20% of total generating capacity. More power generating capacity came on line in the mid-2000s as large scale investments were completed. In 2001, China's total energy consumption was projected to double by 2020. Energy consumption grew at nearly 10 percent per year between 2000 and 2005, more than twice the yearly rate of the previous two decades.[91]

In 2003, China surpassed Japan to become the second-largest consumer of primary energy, after the United States. China is the world's second-largest consumer of oil, after the United States, and for 2006, China's increase in oil demand represented 38% of the world total increase in oil demand. China is also the third-largest energy producer in the world, after the United States and Russia. China's electricity consumption is expected to grow by over 4% a year through 2030, which will require more than $2 trillion in electricity infrastructure investment to meet the demand. China expects to add approximately 15,000 megawatts of generating capacity a year, with 20% of that coming from foreign suppliers.

China, due in large part to environmental concerns, has wanted to shift China's current energy mix from a heavy reliance on coal, which accounts for 70–75% of China's energy, toward greater reliance on oil, natural gas, renewable energy, and nuclear power. China has closed thousands of coal mines over the past five to ten years to cut overproduction. According to Chinese statistics, this has reduced coal production by over 25%.

Only one-fifth of the new coal power plant capacity installed from 1995 to 2000 included desulfurization equipment. Interest in renewable sources of energy is growing, but except for hydropower, their contribution to the overall energy mix is unlikely to rise above 1–2% in the near future. China's energy sector continues to be hampered by difficulties in obtaining funding, including long-term financing, and by market balkanization due to local protectionism that prevents more efficient large plants from achieving economies of scale.

Since 1993, China has been a net importer of oil, a large portion of which comes from the Middle East. Imported oil accounts for 20% of the processed crude in China. Net imports are expected to rise to 3.5 million barrels (560,000 m3) per day by 2010. China is interested in diversifying the sources of its oil imports and has invested in oil fields around the world. China is developing oil imports from Central Asia and has invested in Kazakhstani oil fields. Beijing also plans to increase China's natural gas production, which currently accounts for only 3% of China's total energy consumption and incorporated a natural gas strategy in its 10th Five-Year Plan (2001–2005), with the goal of expanding gas use from a 2% share of total energy production to 4% by 2005 (gas accounts for 25% of U.S. energy production). Analysts expect China's consumption of natural gas to more than double by 2010.

The 11th Five-Year Program (2006–10), announced in 2005 and approved by the National People's Congress in March 2006, called for greater energy conservation measures, including development of renewable energy sources and increased attention to environmental protection. Guidelines called for a 20% reduction in energy consumption per unit of GDP by 2010. Moving away from coal towards cleaner energy sources including oil, natural gas, renewable energy, and nuclear power is an important component of China's development program. Beijing also intends to continue to improve energy efficiency and promote the use of clean coal technology. China has abundant hydroelectric resources; the Three Gorges Dam, for example, will have a total capacity of 18 gigawatts when fully on-line (projected for 2009). In addition, the share of electricity generated by nuclear power is projected to grow from 1% in 2000 to 5% in 2030. China's renewable energy law, which went into effect in 2006, calls for 10% of its energy to come from renewable energy sources by 2020.