Poland

Republic of Poland Rzeczpospolita Polska | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Mazurek Dąbrowskiego (Dąbrowski's Mazurka) | |

![Location of Poland (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) – in the European Union (green) – [Legend]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/EU-Poland.svg/250px-EU-Poland.svg.png) Location of Poland (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Warsaw |

| Ethnic groups (2002) | 96.7% Poles, 3.3% others and unspecified |

| Demonym(s) | Pole/Polish |

| Government | Parliamentary republic |

| Bronisław Komorowski | |

| Donald Tusk | |

| Formation | |

| April 14, 966 | |

| July 1, 1569 | |

| November 11, 1918 | |

| December 31, 1944 | |

• Third Republic | January 30, 1990 |

| Area | |

• Total | 312,685 km2 (120,728 sq mi)[d] (69th) |

• Water (%) | 3.07 |

| Population | |

• 2010 estimate | 38,186,860[1] (34th) |

• 2002 census | 38,231,000 |

• Density | 120/km2 (310.8/sq mi) (83rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $754,097 billion[2] (20th) |

• Per capita | $19,752[3] (40th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $468.539 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $12,300[4] |

| Gini (2002) | 34.5 Error: Invalid Gini value |

| HDI (2010) | Error: Invalid HDI value (41st) |

| Currency | Złoty (PLN) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | 48 |

| ISO 3166 code | PL |

| Internet TLD | .pl |

| |

Poland (/[invalid input: 'en-us-Poland.ogg']ˈpoʊlənd/; Template:Lang-pl), officially the Republic of Poland (Template:Lang-pl; Template:Lang-csb; Template:Lang-szl), is a country in Eastern Europe[7][8] bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north. The total area of Poland is 312,679 square kilometres (120,726 sq mi),[6] making it the 69th largest country in the world and the 9th largest in Europe. Poland has a population of over 38 million people,[6] which makes it the 34th most populous country in the world[9] and the sixth most populous member of the European Union, being its most populous post-communist member. Poland is a unitary state made up of sixteen voivodeships. Poland is a member of the European Union, NATO, the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), European Economic Area, International Energy Agency, Council of Europe, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, International Atomic Energy Agency and G6.

On 1 July 2011, Poland replaced Hungary as the holder of the rotating Presidency of the Council of the European Union.

The establishment of a Polish state is often identified with the adoption of Christianity by its ruler Mieszko I in 966, over the territory similar to that of present-day Poland. The Kingdom of Poland was formed in 1025, and in 1569 it cemented a long association with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania by signing the Union of Lublin, forming the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Commonwealth ceased to exist in 1795 as the Polish lands were partitioned among the Kingdom of Prussia, the Russian Empire, and Austria. Poland regained its independence as the Second Polish Republic in 1918. Two decades later, in September 1939, it was invaded by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, triggering World War II. Over six million Polish citizens died in the war. Poland reemerged several years later within the Soviet sphere of influence as the People's Republic in existence until 1989. During the Revolutions of 1989, communist rule was overthrown and soon after, Poland became what is constitutionally known as the "Third Polish Republic".

Despite the vast destruction the country experienced in World War II, Poland managed to preserve much of its cultural wealth. Since the end of the communist period, Poland has achieved a "very high" ranking in terms of human development[10] and standard of living.[11]

History

Etymology

The source of the name Poland[12] and the ethnonyms for the Poles[13] include endonyms (the way Polish people refer to themselves and their country) and exonyms (the way other peoples refer to the Poles and their country). Endonyms and most exonyms for Poles and Poland derive from the name of the West Slavic tribe of the Polans (Polish Polanie). The origin of the name Polanie itself is uncertain. It may derive from such Polish words as pole (field).[14] The early tribal inhabitants denominated it from the nature of the country. Lowlands and low hills predominate throughout the vast region from the Baltic shores to the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains. Inter Alpes Huniae et Oceanum est Polonia, sic dicta in eorum idiomate quasi Campania is the description by Gervase of Tilbury in his Otia imperialia (Recreation for the emperor, 1211). In some languages the exonyms for Poland derive from another tribal name, Lechites (Lechici).

Prehistory

Historians have postulated that throughout Late Antiquity, many distinct ethnic groups populated the regions of what is now known as Poland. The ethnicity and linguistic affiliation of these groups have been hotly debated; the time and route of the original settlement of Slavic peoples in these regions have been the particular subjects of much controversy.

The most famous archeological find from the prehistory and protohistory of Poland is the Biskupin fortified settlement (now reconstructed as a museum), dating from the Lusatian culture of the early Iron Age, around 700 B.C. Before adopting Christianity in 960 A.D., the people of Poland believed in Svetovid, the Slavic god of war, fertility, and abundance. Many other Slavic nations had the same belief.

Piast dynasty

Poland began to form into a recognizable unitary and territorial entity around the middle of the 10th century under the Piast dynasty. Poland's first historically documented ruler, Mieszko I, was baptized in 966, adopting Catholic Christianity as the nation's new official religion, to which the bulk of the population converted in the course of the next centuries. In the 12th century, Poland fragmented into several smaller states when Bolesław divided the nation amongst his sons. In 1226 Konrad I of Masovia, one of the regional Piast dukes, invited the Teutonic Knights to help him fight the Baltic Prussian pagans; a decision which would ultimately lead to centuries of Poland's warfare with the Knights. In 1320, after a number of earlier unsuccessful attempts by regional rulers at uniting the Polish dukedoms, Władysław I consolidated his power, took the throne and became the first King of a reunified Poland. His son, Casimir III, is remembered as one of the greatest Polish kings and is particularly famous for extending royal protection to Jews and providing the original impetus for the establishment of Poland's first university. The Golden Liberty of the nobles began to develop under Casimir's rule, when in return for their military support, the king made serious concessions to the aristocrats, finally establishing their status as superior to that of the townsmen, and aiding their rise to power. When Casimir died in 1370 he left no legitimate male heir and, considering his other male descendants either too young or unsuitable, was laid to rest as the last of the nation's Piast rulers.

Poland was also a centre of migration of peoples. The Jewish community began to settle and flourish in Poland during this era (see History of the Jews in Poland). The Black Death which affected most parts of Europe from 1347 to 1351 did not reach Poland.[15]

Jagiellon dynasty

The rule of the Jagiellon dynasty, spanned the late Middle Ages and early Modern Era of Polish history. Beginning with the Lithuanian Grand Duke Jogaila (Władysław II Jagiełło), the Jagiellon dynasty (1386–1572) formed the Polish–Lithuanian union. The partnership brought vast Lithuania-controlled Rus' areas into Poland's sphere of influence and proved beneficial for the Poles and Lithuanians, who coexisted and cooperated in one of the largest political entities in Europe for the next four centuries. In the Baltic Sea region Poland's struggle with the Teutonic Knights continued and included the Battle of Grunwald (1410), where a Polish-Lithuanian army inflicted a decisive defeat on the Teutonic Knights, both countries' main adversary, allowing Poland's and Lithuania's territorial expansion into the far north region of Livonia.[16] In 1466, after the Thirteen Years' War, King Casimir IV Jagiellon gave royal consent to the milestone Peace of Thorn, which created the future Duchy of Prussia, a Polish vassal. The Jagiellons at one point also established dynastic control over the kingdoms of Bohemia (1471 onwards) and Hungary.[17] [18] In the south Poland confronted the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean Tatars (by whom they were attacked on 75 separate occasions between 1474–1569),[19] and in the east helped Lithuania fight the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Some historians estimate that Crimean Tatar slave-raiding cost Poland one million of its population from 1494 to 1694.[20]

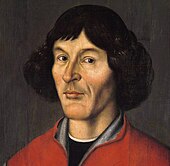

Poland was developing as a feudal state, with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly powerful landed nobility. The Nihil novi act adopted by the Polish Sejm (parliament) in 1505, transferred most of the legislative power from the monarch to the Sejm, an event which marked the beginning of the period known as "Golden Liberty", when the state was ruled by the "free and equal" Polish nobility. Protestant Reformation movements made deep inroads into Polish Christianity, which resulted in the establishment of policies promoting religious tolerance, unique in Europe at that time. It is believed that this tolerance allowed the country to avoid the religious turmoil that spread over Western Europe during the late Middle Ages. The European Renaissance evoked in late Jagiellon Poland (kings Sigismund I the Old and Sigismund II Augustus) a sense of urgency in the need to promote a cultural awakening, and resultantly during this period Polish culture and the nation's economy flourished. In 1543 the Pole, Nicolaus Copernicus, an astronomer from Toruń, published his epochal works, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), and thus became the first proponent of a predictive mathematical model confirming heliocentric theory which ultimately became the accepted basic model for the practice of modern astronomy. Another major figure associated with the era is classicist poet Jan Kochanowski.[21]

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The 1569 Union of Lublin established the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a more closely unified federal state with an elective monarchy, but which was governed largely by the nobility, through a system of local assemblies with a central parliament. The establishment of the Commonwealth coincided with a period of great stability and prosperity in Poland, with the union soon thereafter becoming a great European power and a major cultural entity, occupying approximately one million square kilometres of central Europe, as well as an agent for the expansion of Western culture to the east. Unfortunately it suffered from a number of dynastic crises during the reigns of the Vasa kings Sigismund III and Władysław IV and found itself engaged in a major conflicts with Russia, Sweden and the Ottoman Empire, as well as a series of minor Cossack uprisings.[22]

Beginning in the middle of the 17th century, the nobles' democracy, suffering from internal disorder, gradually declined, thus leaving the once powerful Commonwealth extremely vulnerable to foreign intervention. From 1648, the Cossack Khmelnytsky Uprising engulfed the south and east eventually leaving the Ukraine divided, with the eastern part, lost by the Commonwealth, becoming a dependency of the Russian Tsar. This was soon followed by a Swedish invasion, which raged through the Polish heartlands and caused unprecedented damage to infrastructure. Famines and epidemics followed hostilities, and the population dropped from roughly 11 to 7 million.[23] However, under John III Sobieski the Commonwealth's military prowess was re-established, and in 1683 Polish forces played a major part in relieving Vienna of a major Turkish siege which was being conducted by Kara Mustafa in hope of eventually marching his troops further into Europe to spread Islam. Unfortunately, Sobieski's reign was to mark the end of the nation's golden-era, and soon, finding itself subjected to almost constant warfare and suffering enormous population losses as well as massive damage to its economy, the Commonwealth fell into decline. The government became ineffective as a result of large scale internal conflicts (e.g. Lubomirski's Rokosz against John II Casimir and rebellious confederations) and corrupted legislative processes. The nobility fell under the control of a handful of magnates, and this, compounded with two relatively weak kings of the Saxon Wettin dynasty, Augustus II and Augustus III, as well as the rise of Russia and Prussia after the Great Northern War only served to worsen the Commonwealth's plight. Despite this The Commonwealth-Saxony personal union gave rise to the emergence of the Commonwealth's first reform movement, and laid the foundations for the Polish Enlightenment.[24]

During the later part of the 18th century, the Commonwealth made attempts to implement fundamental internal reforms; with the second half of the century bringing a much improved economy, significant population growth and far-reaching progress in the areas of education, intellectual life, art, and especially toward the end of the period, evolution of the social and political system. The most populous capital city of Warsaw replaced Gdańsk (Danzig) as the leading centre of commerce, and the role of the more prosperous townsfolk soon increased. The royal election of 1764 resulted in the elevation of Stanisław August Poniatowski, a refined and worldly aristocrat connected to a major magnate faction, to the monarchy. However, a one-time lover of Empress Catherine II of Russia, the new King spent much of his reign torn between his desire to implement reforms necessary to save his nation, and his perceived necessity to remain in a relationship with his Russian sponsor. This ultimately led to the formation of the 1768 Bar Confederation; a szlachta rebellion directed against Russia and the Polish king which fought to preserve Poland's independence and the szlachta's traditional privileges. Unfortunately, attempts at reform provoked the union's neighbours, and in 1772 the First Partition of the Commonwealth by Russia, Austria and Prussia took place; an act which the "Partition Sejm", under considerable duress, eventually "ratified" fait accompli.[25] Disregarding this loss, in 1773 the king established the Commission of National Education, the first government education authority in Europe.

The long-lasting Great Sejm convened by Stanisław August in 1788 successfully adopted the May 3 Constitution, the first set of modern supreme national laws in Europe. However, this document, accused by detractors of harbouring revolutionary sympathies, soon generated strong opposition from the Commonwealth's nobles and conservatives as well as from Catherine II, who, determined to prevent the rebirth of a strong Commonwealth set about planning the final dismemberment of the Polish-Lithuanian state. Russia was greatly aided in achieving its goal when the Targowica Confederation, an organisation of Polish nobles, appealed to the Empress for help, and in May 1792 Russian forces crossed the Commonwealth's frontier, thus beginning the Polish-Russian War. The defensive war fought by the Poles and Lithuanians ended prematurely when the King, convinced of the futility of resistance, capitulated and joined the Targowica Confederation. The Confederation then took over the government; but Russia and Prussia, fearing the mere existence of a Polish state, arranged for, and subsequently in 1793, executed the Second Partition of the Commonwealth, which left the country deprived of so much territory that it was practically incapable of independent existence. Eventually, in 1795, following the failed Kościuszko Uprising, the Commonwealth was partitioned one last time by all three of its more powerful neighbours, and with this, effectively ceased to exist.[26]

The Age of Partitions

Poles rebelled several times against the partitioners, particularly near the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. One of the most famous and successful attempts at securing renewed Polish independence took place in 1794, during the Kościuszko Uprising, at the Racławice where Tadeusz Kosciuszko, a popular and distinguished general who had served under Washington in America, led peasants and some Polish regulars into battle against numerically superior Russian forces. In 1807, Napoleon I of France recreated a Polish state, the Duchy of Warsaw, but after the Napoleonic Wars, Poland was again divided by the victorious Allies at the Congress of Vienna of 1815. The eastern portion was ruled by the Russian tsar as a Congress Kingdom which possessed a very liberal constitution. However, the tsars soon reduced Polish freedoms, and Russia annexed the country in all but name. Thus in the latter half of the 19th century, only Austrian-ruled Galicia, and particularly the Free City of Kraków, was able to become a centre for Polish cultural life.

Throughout the period of the partitions, political and cultural repression of the Polish nation led to the organisation of a number of uprisings against the authorities of the occupying Russian, Prussian and Austrian governments. Notable amongst these are the November Uprising of 1830 and January Uprising of 1863, both of which were attempts to free Poland from the rule of tsarist Russia. The November uprising began on 29 November 1830 in Warsaw when, led by Lieutenant Piotr Wysocki, young non-commissioned officers at the Imperial Russian Army's military academy in that city revolted. They were soon joined by large segments of Polish society, and together forced Warsaw's Russian garrison to withdraw north of the city.

Over the course of the next seven months, Polish forces successfully defeated the Russian armies of Field Marshal Hans Karl von Diebitsch and a number of other Russian commanders; however, finding themselves in a position unsupported by any other foreign powers, save distant France and the new-born United States, and with Prussia and Austria refusing to allow the import of military supplies through their territories, the Poles accepted that the uprising was doomed to failure. Upon the surrender of Warsaw to General Ivan Paskievich, many Polish troops, feeling they could not go on, withdrew into Germany and there laid down their arms. Poles would have to wait another 32 years for another opportunity to free their homeland.

When in January 1863 a new Polish uprising against Russian rule began, it did so as a spontaneous protest by young Poles against conscription into the Imperial Russian Army. However, the insurrectionists, despite being joined by high-ranking Polish-Lithuanian officers and numerous politicians were still severely outnumbered and lacking in foreign support. They were forced to resort to guerrilla warfare tactics and ultimately failed to win any major military victories. Afterwards no major uprising was witnessed in the Russian controlled Congress Poland and Poles resorted instead to fostering economic and cultural self-improvement.

Despite the political unrest experienced during the partitions, Poland did benefit from large scale industrialisation and modernisation programs, instituted by the occupying powers, which helped it develop into a more economically coherent and viable entity. This was particularly true in the western provinces annexed by Prussia (later becoming part of the German Empire); an area which eventually, thanks largely to the Greater Poland Uprising was reconstituted as part of the Second Polish Republic and became one of its most productive regions.

Reconstitution of Poland

During World War I, all the Allies agreed on the reconstitution of Poland that United States President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed in Point 13 of his Fourteen Points. A total of 2 million Polish troops fought with the armies of the three occupying powers, and 450,000 died.[27] Shortly after the armistice with Germany in November 1918, Poland regained its independence as the Second Polish Republic (II Rzeczpospolita Polska). It reaffirmed its independence after a series of military conflicts, the most notable being the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921) when Poland inflicted a crushing defeat on the Red Army at the Battle of Warsaw, an event which is considered to have ultimately halted the advance of Communism into Europe and forced Lenin to rethink his objective of achieving global socialism. Nowadays the event is often referred to as the 'Miracle at the Vistula'.[28]

During this period, Poland successfully managed to fuse the territories of the three former partitioning powers into a cohesive nation state. Railways were restructured to direct traffic towards Warsaw instead of the former imperial capitals, a new network of national roads was gradually built up and a major seaport was opened on the Baltic Coast, so as to allow Polish exports and imports to bypass the politically charged Free City of Danzig.

The inter-war period heralded in a new era of Polish politics. Whilst Polish political activists had faced heavy censorship in the decades up until the First World War, the country now found itself trying to establish a new political tradition. For this reason, many exiled Polish activists, such as Jan Paderewski (who would later become Prime Minister) returned home to help; a great number of them then went on to take key positions in the newly formed political and governmental structures. Tragedy struck in 1922 when Gabriel Narutowicz, inaugural holder of the Presidency, was assassinated at the Zachęta Gallery in Warsaw by painter and right-wing nationalist Eligiusz Niewiadomski.[29]

The 1926 May Coup of Józef Piłsudski turned rule of the Second Polish Republic over to the Sanacja movement. By the 1930s Poland had become increasingly authoritarian; a number of 'undesirable' political parties, such as the Polish Communists, had been banned and following Piłsudski's death, the regime, unable to appoint a new leader, began to show its inherent internal weaknesses and unwillingness to cooperate in any way with other political parties.

World War II

The Sanacja movement controlled Poland until the start of World War II in 1939, when Nazi Germany invaded on 1 September and the Soviet invasion of Poland followed by breaking the Soviet–Polish Non-Aggression Pact on 17 September. Warsaw capitulated on 28 September 1939. As agreed in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Poland was split into two zones, one occupied by Germany while the eastern provinces fell under the control of the Soviet Union. By 1941 the Soviets had moved hundreds of thousands of Poles into labor camps all over the Soviet Union, and the Soviet secret police, NKVD, had executed thousands of Polish prisoners of war.[30]

Poland made the fourth-largest troop contribution to the Allied war effort, after the Soviets, the British and the Americans.[a] Polish troops fought under the command of both the command of the Polish Government in Exile in the western theatre of war and under Soviet leadership in the East European theatre. The Polish expeditionary corps, which was controlled from by the exiled pre-war government based in London, played an important role in the Italian and North African Campaigns,[31][32] they are particularly well remembered for their conduct at the Battle of Monte Cassino, a conflict which culminated in the raising of a Polish flag over the ruins of the mountain-top abbey by the 12th Podolian Uhlans. The Polish forces in the West were commanded by Lieutenant General Władysław Anders who had received his command from Prime Minister of the exiled government Władysław Sikorski. On the eastern front, the Soviet-backed Polish 1st Army distinguished itself in the battles for Berlin and Warsaw, although its actions in support of the latter have often been criticised.

Polish servicemen were also active in the theatres of naval and air warfare; during the Battle of Britain Polish squadrons such as the No. 303 "Kościuszko" fighter squadron [33] achieved great success, and by the end of the war the exiled Polish Air Forces could claim 769 confirmed kills. Meanwhile, the navy was active in the protection of convoys in the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean.[34]

In addition to the organised units of the 1st Army and the Forces in the West, the domestic underground resistance movement, the Armia Krajowa (Home Army), fought to free Poland from German occupation and establish an independent Polish state. The wartime resistance movement in Poland was one of the three largest resistance movements of the entire war[b] and encompassed a uniquely large range of clandestine activities, essentially functioning as an underground state complete with underground universities and courts.[35] The resistance was however, largely loyal to the exiled government and generally resented the idea of a communist Poland; for this reason, on 1st August 1944 they initiated Operation Tempest and thus began the Warsaw Uprising.[36][37] The objective of the uprising was to drive the German occupiers from the city and help with the larger fight against Germany and the Axis powers, however secondary motives for the uprising sought to see Warsaw liberated before the Soviets could reach the capital, so as to underscore Polish sovereignty by empowering the Polish Underground State before the Soviet-backed Polish Committee of National Liberation could assume control. However, a lack of available allied military aid and Stalin's reluctance to allow the 1st Army to help their fellow countrymen take the city, ultimately led to the uprising's failure and subsequent planned destruction of the city.

During the war, German forces, under direct order from Adolf Hitler, set up six major extermination camps, all of which were established on Polish territory; these included both the notorious Treblinka and Auschwitz camps. This allowed the Nazis to transport German Jews outside of 'German' territory, as well as import Jews and other 'undesirables' from across occupied Europe to be 'liquidated' in the concentration camps set up in the General Government. Other undesirables included Polish intelligentsia, Communists, Roma peoples and Soviet Prisoners of War. However, since millions of Jews lived in pre-war Poland, Jewish victims make up the largest percentage of all victims of the Nazis' extermination program. It is estimated that around 90% (or about 3 million members) of pre-war Poland's Jewry were put to death by the Nazis during the Second World War. Throughout the occupation, many members of the Armia Krajowa, supported by the Polish government in exile, and millions of ordinary Poles — at great risk to themselves and their families — engaged in rescuing Jews from the Nazis. Grouped by nationality, Poles represent the largest number of people who rescued Jews during the Holocaust.[38][39] To date, 6,135 Poles have been awarded the title of Righteous among the Nations by the State of Israel – more than any other nation.[38] Some estimates put the number of Poles involved in rescue at up to 3 million, and credit Poles with saving up to around 450,000 Jews from certain death.[39]

At the war's conclusion, Poland's borders were shifted westwards, pushing the eastern border to the Curzon Line. Meanwhile, the western border was moved to the Oder-Neisse line. The new Poland emerged 20% smaller by 77,500 square kilometres (29,900 sq mi). The shift forced the migration of millions of people, most of whom were Poles, Germans, Ukrainians, and Jews.[40] Of all the countries involved in the war, Poland lost the highest percentage of its citizens: over 6 million perished — nearly one-fifth of Poland's population — half of them Polish Jews. Over 90% of the death toll came through non-military losses. Only in the 1970s did Poland again approach its prewar population level.[41] An estimated 600,000 Soviet soldiers died in conquering Poland from German rule.[42]

Postwar communist Poland

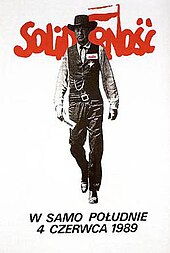

"The 4th of June, 1989 marked a decisive victory for democracy in Poland and, ultimately, across Eastern Europe."

At the insistence of Joseph Stalin, the Yalta Conference sanctioned the formation of a new Polish provisional and pro-Communist coalition government in Moscow, which ignored the Polish government-in-exile based in London; a move which angered many Poles who considered it a betrayal by the Western Allies. In 1944, Stalin had made guarantees to Churchill and Roosevelt that he would maintain Poland's sovereignty and allow democratic elections to take place; however, upon achieving victory in 1945, the occupying Soviet authorities organised an election which constituted nothing more than a sham and was ultimately used to claim the 'legitimacy' of Soviet hegemony over Polish affairs. The Soviet Union instituted a new communist government in Poland, analogous to much of the rest of the Eastern Bloc. As elsewhere in Eastern Europe the Soviet occupation of Poland met with armed resistance from the outset which continued into the fifties.

Despite widespread objections, the new Polish government accepted the Soviet annexation of the pre-war Eastern regions of Poland[44] (in particular the cities of Wilno and Lwów) and agreed to the permanent garrisoning of Red Army units on Poland's territory. Military alignment within the Warsaw Pact throughout the Cold War came about as a direct result of this change in Poland's political culture and in Western eyes came to characterise the fully-fledged integration of Poland into the brotherhood of communist nations.

The People's Republic of Poland (Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa) was officially proclaimed in 1952. In 1956, the régime of Władysław Gomułka became temporarily more liberal, freeing many people from prison and expanding some personal freedoms. A similar situation repeated itself in the 1970s under Edward Gierek, but most of the time persecution of anti-communist opposition groups persisted. Despite this, Poland was at the time considered to be one of the least repressive Eastern Bloc states.[45]

Labour turmoil in 1980 led to the formation of the independent trade union "Solidarity" ("Solidarność"), which over time became a political force. Despite persecution and imposition of martial law in 1981, it eroded the dominance of the Communist Party and by 1989 had triumphed in Poland's first free and democratic parliamentary elections since the end of the Second World War. Lech Wałęsa, a Solidarity candidate, eventually won the presidency in 1990. The Solidarity movement heralded the collapse of communism across Eastern Europe.

Present day Poland

A shock therapy programme, initiated by Leszek Balcerowicz in the early 1990s enabled the country to transform its socialist-style planned economy into a market economy. As with all other post-communist countries, Poland suffered temporary slumps in social and economic standards, but it became the first post-communist country to reach its pre-1989 GDP levels, which it achieved by 1995 largely thanks to its booming economy.[46][47]

Most visibly, there were numerous improvements in human rights, such as the freedom of speech. In 1991, Poland became a member of the Visegrád Group and joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance in 1999 along with the Czech Republic and Hungary. Poles then voted to join the European Union in a referendum in June 2003, with Poland becoming a full member on 1 May 2004. Subsequently Poland joined the Schengen Area in 2007, as a result of which, the country's borders with other member states of the European Union have been dismantled, allowing for full freedom of movement within most of the EU.[48] In contrast to this, the section of Poland's eastern border now comprising the external EU border with Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, has become increasingly well protected, and has led in part to the coining of the phrase 'Fortress Europe', in reference to the seeming 'impossibility' of gaining entry to the EU for citizens of the former Soviet Union.

On April 10, 2010, the President of the Republic of Poland, Lech Kaczyński, along with 89 other high-ranking Polish officials died in a plane crash near Smolensk, Russia. The president's party were on their way to attend an annual service of commemoration for the victims of the Katyń massacre when the tragedy took place.

Geography

Poland's territory extends across several geographical regions, between latitudes 49° and 55° N, and longitudes 14° and 25° E. In the northwest is the Baltic seacoast, which extends from the Bay of Pomerania to the Gulf of Gdańsk. This coast is marked by several spits, coastal lakes (former bays that have been cut off from the sea), and dunes. The largely straight coastline is indented by the Szczecin Lagoon, the Bay of Puck, and the Vistula Lagoon. The centre and parts of the north lie within the North European Plain.

Rising gently above these lowlands is a geographical region comprising the four hilly districts of moraines and moraine-dammed lakes formed during and after the Pleistocene ice age. These lake districts are the Pomeranian Lake District, the Greater Polish Lake District, the Kashubian Lake District, and the Masurian Lake District. The Masurian Lake District is the largest of the four and covers much of northeastern Poland. The lake districts form part of the Baltic Ridge, a series of moraine belts along the southern shore of the Baltic Sea.

South of the Northern European Lowlands lie the regions of Silesia and Masovia, which are marked by broad ice-age river valleys. Farther south lies the Polish mountain region, including the Sudetes, the Cracow-Częstochowa Upland, the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, and the Carpathian Mountains, including the Beskids. The highest part of the Carpathians is the Tatra Mountains, along Poland's southern border.

Geology

The geological structure of Poland has been shaped by the continental collision of Europe and Africa over the past 60 million years, on the one hand, and the Quaternary glaciations of northern Europe, on the other. Both processes shaped the Sudetes and the Carpathian Mountains. The moraine landscape of northern Poland contains soils made up mostly of sand or loam, while the ice age river valleys of the south often contain loess. The Cracow-Częstochowa Upland, the Pieniny, and the Western Tatras consist of limestone, while the High Tatras, the Beskids, and the Karkonosze are made up mainly of granite and basalts. The Polish Jura Chain is one of the oldest mountain ranges on earth.

Poland has 70 mountains over 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) in elevation, all in the Tatras. The Polish Tatras, which consist of the High Tatras and the Western Tatras, is the highest mountain group of Poland and of the entire Carpathian range. In the High Tatras lies Poland’s highest point, the northwestern peak of Rysy, 2,499 metres (8,199 ft) in elevation. At its foot lies the mountain lakes Czarny Staw pod Rysami and Morskie Oko.

The second highest mountain group in Poland is the Beskids, whose highest peak is Babia Góra, at 1,725 metres (5,659 ft). The next highest mountain group is the Karkonosze in the Sudetes, whose highest point is Sněžka, at 1,602 metres (5,256 ft). Among the most beautiful mountains of Poland are the Bieszczady Mountains in the far southeast of Poland, whose highest point in Poland is Tarnica, with an elevation of 1,346 metres (4,416 ft).

Tourists also frequent the Gorce Mountains in Gorce National Park, with elevations around 1,310 metres (4,298 ft), and the Pieniny in Pieniny National Park, with elevations around 1,050 metres (3,445 ft). The lowest point in Poland—at 2 metres (6.6 ft) below sea level—is at Raczki Elbląskie, near Elbląg in the Vistula Delta.

Błędów Desert is a desert located in southern Poland in the Silesian Voivodeship and stretches over the Zagłębie Dąbrowskie region. It has a total area of 32 square kilometres (12 sq mi). It is the only desert located in Poland. It is one of only five natural deserts in Europe. It is the warmest desert that appears at this latitude.

It was created thousands of years ago by a melting glacier. The specific geological structure has been of big importance. The average thickness of the sand layer is about 40 metres (131 ft), with a maximum of 70 metres (230 ft), which made the fast and deep drainage very easy.

The sea’s activity in Słowiński National Park created sand dunes which in the course of time separated the bay from the Baltic Sea. As waves and wind carry sand inland the dunes slowly move, at a speed of 3 to 10 metres (9.8 to 32.8 ft) meters per year. Some dunes are quite high – up to 30 metres (98 ft). The highest peak of the park — Rowokol (115 metres (377 ft)* above sea level) — is also an excellent observation point.

Waters

The longest rivers are the Vistula (Template:Lang-pl), 1,047 kilometres (651 mi) long; the Oder (Template:Lang-pl) which forms part of Poland’s western border, 854 kilometres (531 mi) long; its tributary, the Warta, 808 kilometres (502 mi) long; and the Bug, a tributary of the Vistula, 772 kilometres (480 mi) long. The Vistula and the Oder flow into the Baltic Sea, as do numerous smaller rivers in Pomerania.

The Łyna and the Angrapa flow by way of the Pregolya to the Baltic, and the Czarna Hańcza flows into the Baltic through the Neman. While the great majority of Poland’s rivers drain into the Baltic Sea, Poland’s Beskids are the source of some of the upper tributaries of the Orava, which flows via the Váh and the Danube to the Black Sea. The eastern Beskids are also the source of some streams that drain through the Dniester to the Black Sea.

Poland’s rivers have been used since early times for navigation. The Vikings, for example, traveled up the Vistula and the Oder in their longships. In the Middle Ages and in early modern times, when the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was the breadbasket of Europe; the shipment of grain and other agricultural products down the Vistula toward Gdańsk and onward to Western Europe took on great importance.

With almost ten thousand closed bodies of water covering more than 1 hectare (2.47 acres) each, Poland has one of the highest number of lakes in the world. In Europe, only Finland has a greater density of lakes. The largest lakes, covering more than 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi), are Lake Śniardwy and Lake Mamry in Masuria, and Lake Łebsko and Lake Drawsko in Pomerania.

In addition to the lake districts in the north (in Masuria, Pomerania, Kashubia, Lubuskie, and Greater Poland), there is also a large number of mountain lakes in the Tatras, of which the Morskie Oko is the largest in area. The lake with the greatest depth—of more than 100 metres (328 ft)—is Lake Hańcza in the Wigry Lake District, east of Masuria in Podlaskie Voivodeship.

Among the first lakes whose shores were settled are those in the Greater Polish Lake District. The stilt house settlement of Biskupin, occupied by more than one thousand residents, was founded before the 7th century BC by people of the Lusatian culture.

Lakes have always played an important role in Polish history and continue to be of great importance to today's modern Polish society. The ancestors of today’s Poles, the Polanie, built their first fortresses on islands in these lakes. The legendary Prince Popiel is supposed to have ruled from Kruszwica on Lake Gopło. The first historically documented ruler of Poland, Duke Mieszko I, had his palace on an island in the Warta River in Poznań. Nowadays the Polish lakes provide an invaluable location for the pursuit of water sports such as yachting and wind-surfing.

The Polish Baltic coast is approximately 528 kilometres (328 mi) long and extends from Świnoujście on the islands of Usedom and Wolin in the west to Krynica Morska on the Vistula Spit in the east. For the most part, Poland has a smooth coastline, which has been shaped by the continual movement of sand by currents and winds from west to east. This continual erosion and deposition has formed cliffs, dunes, and spits, many of which have migrated landwards to close off former lagoons, such as Łebsko Lake in Słowiński National Park.

Prior to the end of the Second World War and subsequent change in national borders, Poland had only a very small coastline; this was situated at the end of the 'Polish Corridor', the only internationally recognised Polish territory which afforded the country access to the sea. However after World War II, the redrawing of Poland's borders and resulting 'shift' of the country to the West left it with a greatly expanded coastline, thus allowing for far greater access to the sea than was ever previously possible. The significance of this event, and importance of it to Poland's future as a major industrialised nation, was allured to by the 1945 Wedding to the Sea.

The largest spits are Hel Peninsula and the Vistula Spit. The largest Polish Baltic island is Wolin. The largest port cities are Gdynia, Gdańsk, Szczecin, and Świnoujście. The main coastal resorts are Sopot, Międzyzdroje, Kołobrzeg, Łeba, Władysławowo, and the Hel Peninsula.

Land use

Forests cover 28.8% of Poland’s land area. More than half of the land is devoted to agriculture. While the total area under cultivation is declining, the remaining farmland is more intensively cultivated.

More than 1% of Poland’s territory, 3,145 square kilometres (1,214 sq mi), is protected within 23 Polish national parks. Three more national parks are projected for Masuria, the Cracow-Częstochowa Upland, and the eastern Beskids. In addition, wetlands along lakes and rivers in central Poland are legally protected, as are coastal areas in the north. There are over 120 areas designated as landscape parks, along with numerous nature reserves and other protected areas.

Present day Poland is a country with great agricultural prospects; there are over two million private farms in the country, and Poland is the leading producer in Europe of potatoes and rye and is one of the world's largest producers of sugar beets and triticale. This has led Poland to be described on occasion as the future 'bread basket of the European Union'. However, despite employing around 16% of the workforce, agricultural output in Poland remains low and the industry is characterised as largely inefficient due to the large number of small, independent farms. This situation is likely to soon change for the better with the government debating agricultural reform and currently pursuing the option of auctioning off large tracts of state-owned agricultural land.

Biodiversity

Phytogeographically, Poland belongs to the Central European province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature, the territory of Poland can be subdivided into three ecoregions: the Baltic mixed forests, Central European mixed forests and Carpathian montane conifer forests.

Many animals that have since died out in other parts of Europe still survive in Poland, such as the wisent in the ancient woodland of the Białowieża Forest and in Podlaskie. Other such species include the brown bear in Białowieża, in the Tatras, and in the Beskids, the gray wolf and the Eurasian Lynx in various forests, the moose in northern Poland, and the beaver in Masuria, Pomerania, and Podlaskie.

In the forests, one also encounters game animals, such as Red Deer, Roe Deer and Wild Boars. In eastern Poland there are a number of ancient woodlands, like Białowieża, that have never been cleared by people. There are also large forested areas in the mountains, Masuria, Pomerania, Lubusz Land and Lower Silesia.

Poland is the most important breeding ground for European migratory birds. Out of all of the migratory birds who come to Europe for the summer, one quarter breed in Poland, particularly in the lake districts and the wetlands along the Biebrza, the Narew, and the Warta, which are part of nature reserves or national parks.

Climate

The climate is mostly temperate throughout the country. The climate is oceanic in the north and west and becomes gradually warmer and continental towards the south and east. Summers are generally warm, with average temperatures between 17 °C (63 °F) and 20 °C (68.0 °F). Winters are cold, with average temperatures around 3 °C (37.4 °F) in the northwest and −6 °C (21 °F) in the northeast. Precipitation falls throughout the year, although, especially in the east; winter is drier than summer.

The warmest region in Poland is Lower Silesian located in south-western Poland where temperatures in the summer average between 22 °C (71.6 °F) and 30 °C (86 °F) but can go as high as 32 °C (89.6 °F) to 38 °C (100.4 °F) on some days in the warmest month of July and August. The warmest cities in Poland are Tarnów, which is situated in Lesser Poland and Wrocław, which is located in Lower Silesian. The average temperatures in Wrocław being 20 °C (68 °F) in the summer and 0 °C (32.0 °F) in the winter, but Tarnów has the longest summer in whole Poland, which lasts for 115 days, from mid-May to mid-September. The coldest region of Poland is in the northeast in the Podlaskie Voivodeship near the border of Belarus. Usually the coldest city is Suwałki. The climate is affected by cold fronts which come from Scandinavia and Siberia. The average temperature in the winter in Podlaskie ranges from −6 °C (21 °F) to −4 °C (25 °F).

Politics

Poland is a democracy, with a president as a head of state, whose current constitution dates from 1997. The government structure centers on the Council of Ministers, led by a prime minister. The president appoints the cabinet according to the proposals of the prime minister, typically from the majority coalition in the Sejm. The president is elected by popular vote every five years. The current president is Bronisław Komorowski. Komorowski replaced President Lech Kaczynski following an April 10, 2010 air crash which claimed the life of President Kaczynski, his wife, and 94 other people, during a visit to western Russia for events marking the 70th anniversary of the Katyn massacre. The current prime minister, Donald Tusk, was appointed in 2007 after his party made significant gains in that year's parliamentary elections.

Polish voters elect a bicameral parliament consisting of a 460-member lower house (Sejm) and a 100-member Senate (Senat). The Sejm is elected under proportional representation according to the d'Hondt method, a method similar to that used in many parliamentary political systems. The Senat, on the other hand, is elected under a rare plurality bloc voting method where several candidates with the highest support are elected from each constituency.

With the exception of ethnic minority parties, only candidates of political parties receiving at least 5% of the total national vote can enter the Sejm. When sitting in joint session, members of the Sejm and Senat form the National Assembly (the Zgromadzenie Narodowe). The National Assembly is formed on three occasions: when a new President takes the oath of office; when an indictment against the President of the Republic is brought to the State Tribunal (Trybunał Stanu); and when a president's permanent incapacity to exercise his duties because of the state of his health is declared. To date only the first instance has occurred.

The judicial branch plays an important role in decision-making. Its major institutions include the Supreme Court of the Republic of Poland (Sąd Najwyższy); the Supreme Administrative Court of the Republic of Poland (Naczelny Sąd Administracyjny); the Constitutional Tribunal of the Republic of Poland (Trybunał Konstytucyjny); and the State Tribunal of the Republic of Poland (Trybunał Stanu). On the approval of the Senat, the Sejm also appoints the ombudsman or the Commissioner for Civil Rights Protection (Rzecznik Praw Obywatelskich) for a five-year term. The ombudsman has the duty of guarding the observance and implementation of the rights and liberties of Polish citizens and residents, of the law and of principles of community life and social justice.

Law

Constitution of Poland is the supreme law in contemporary Poland, and the Polish legal system is based on the principle of civil rights, governed by the code of Civil Law. Historically, the most famous Polish legal act is the Constitution of May 3, 1791. Historian Norman Davies describes it as the first of its kind in Europe.[51] The Constitution was instituted as a Government Act (Template:Lang-pl) and then adopted on May 3, 1791 by the Sejm of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Primarily, it was designed to redress long-standing political defects of the federative Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and its Golden Liberty. Previously only the Henrican articles signed by each of Poland's elected kings could perform the function of a set of basic laws. The new Constitution introduced political equality between townspeople and the nobility (szlachta), and placed the peasants under the protection of the government, thus mitigating the worst abuses of serfdom. The Constitution abolished pernicious parliamentary institutions such as the liberum veto, which at one time had placed the sejm at the mercy of any deputy who might choose, or be bribed by an interest or foreign power, to have rescinded all the legislation that had been passed by that sejm. The May 3rd Constitution sought to supplant the existing anarchy fostered by some of the country's reactionary magnates, with a more egalitarian and democratic constitutional monarchy.

Unfortunately, the adoption of such a liberal constitution was treated as a grave threat by Poland's more autocratic neighbours. In response Prussia, Austria and Russia formed an anti-Polish alliance and over the next decade collaborated with one another to partition their weaker neighbour and ultimately destroy the Polish state. In the words of two of its co-authors, Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj, the constitution represented "the last will and testament of the expiring Fatherland." Despite this, its text influenced many later democratic movements across the globe.

Poland's current constitution was adopted by the National Assembly of Poland on 2 April 1997, approved by a national referendum on 25 May 1997, and came into effect on 17 October 1997. It guarantees a multi-party state, the freedoms of religion, speech and assembly, and specifically casts off many Communist ideals to create a 'free market economic system'. It requires public officials to pursue ecologically sound public policy and acknowledges the inviolability of the home, the right to form trade unions, and to strike, whilst at the same time prohibiting the practices of forced medical experimentation, torture and corporal punishment.

Foreign Relations

In recent years, Poland has extended its responsibilities and position in European and international affairs, supporting and establishing friendly relations with many 'Western' nations and a large number of 'developing' countries.

In 1994, Poland became an associate member of the European Union (EU) and its defensive arm, the Western European Union (WEU), having subimtted preliminary documentation for full membership in 1996, it formally joined the European Union in May 2004, along with the other members of the Visegrád group. In 1996, Poland achieved full OECD membership, and at the 1997 Madrid Summit was invited to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation in the first wave of policy enlargement finally becoming a full member of NATO in March 1999.

As changes since the fall of Communism in 1989 have redrawn the map of central Europe, Poland has tried to forge strong and mutually-beneficial relationships with its seven new neighbours, this has notably included signing 'friendship treaties' to replace links severed by the collapse of the Warsaw Pact. The Poles have forged special relationships with Lithuania and particularly Ukraine,[52] with whom they will co-host the UEFA Euro 2012 football tournament, in an effort to firmly anchor these states to the 'West' and provide them with an alternative to aligning themselves with the Russian Federation. Despite many positive developments in the region, Poland has found itself in a position where it must seek to defend the rights of ethnic Poles living in the former Soviet Union; this is particularly true of Belarus, where in 2005 the Lukashenko regime launched a campaign against the Polish ethnic minority.[53]

Poland is the sixth most populous member state of the European Union and, ever since joining in 2004, has pursued policies to increase its role in European affairs. Poland has a grand total of 51 representatives in the European Parliament and in addition to this, since 14 July 2009, former Prime Minister of Poland Jerzy Buzek, has been President of the European Parliament.[54]

Administrative divisions

Poland's current voivodeships (provinces) are largely based on the country's historic regions, whereas those of the past two decades (to 1998) had been centred on and named for individual cities. The new units range in area from less than 10,000 square kilometres (3,900 sq mi) for Opole Voivodeship to more than 35,000 square kilometres (14,000 sq mi) for Masovian Voivodeship. Administrative authority at voivodeship level is shared between a government-appointed voivode (governor), an elected regional assembly (sejmik) and an executive elected by that assembly.

The voivodeships are subdivided into powiats (often referred to in English as counties), and these are further divided into gminas (also known as communes or municipalities). Major cities normally have the status of both gmina and powiat. Poland currently has 16 voivodeships, 379 powiats (including 65 cities with powiat status), and 2,478 gminas.

Military The Polish armed forces are composed of four branches: Land Forces (Wojska Lądowe), Navy (Marynarka Wojenna), Air Force (Siły Powietrzne) and Special Forces (Wojska Specjalne). The military is subordinate to the Minister for National Defence, however its sole commander in chief is the President of the Republic. The Polish army currently consists of 65,000 active personnel, whilst the navy and air force respectively employ 14,300 and 26,126 servicemen and women. The Polish Navy is one of the bigger navies on the Baltic Sea and is mostly involved in Baltic Sea operations such as search and rescue provision for the section of the Baltic under Polish command, as well as hydrographic measurements and research; recently however, the Polish Navy played a more international role as part of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, providing logistical support for the United States Navy. The current position of the Polish Air Force is much the same; it has routinely taken part in Baltic Air Policing assignments, but otherwise, with the exception of a number of units serving in Afghanistan, has seen no active combat since the end of the Second World War. In 2003, the F-16C Block 52 was chosen as the new general multi-role fighter for the air force, the first deliveries taking place in November 2006; it is expected (2010) that the Polish Air Force will create three squadrons of F-16s, which will all be fully operational by 2012.  The most important mission of the armed forces is the defence of Polish territorial integrity and Polish interests abroad.[55] Poland's national security goal is to further integrate with NATO and European defence, economic, and political institutions through the modernisation and reorganisation of its military.[55] Currently the armed forces is being re-organised according to NATO standards, and as of 1 January 2010, the transition to an entirely contract-based military has been completed. Previously male citizens were expected to complete a period of active service with the military; since 2007 up until the amendment of the law on conscription, the obligatory term of service was nine months.[56] Polish military doctrine reflects the same defensive nature as that of its NATO partners. Poland is also playing an increasing role as a peacekeeping power through various United Nations peacekeeping missions.[55] The Polish Armed Forces took part in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, deploying 2,500 soldiers in the south of that country and commanding the 17-nation Multinational force in Iraq. In addition to this, Polish soldiers are currently deployed in five separate UN Peacekeeping Operations (UNDOF, UNIFIL, EUFOR and KFOR). The total international deployment of the Polish military is currently over 4,800 troops. The military was temporarily, but severely, affected by the loss of many of its top commanders in the wake the 2010 Polish Air Force Tu-154 crash near Smolensk, Russia, which killed all 96 passengers and crew, including, amongst others, the Chief of the Polish Army's General Staff Franciszek Gągor and Polish Air Force commanding general Andrzej Błasik. They were en route from Warsaw to attend an event to mark the 70th anniversary of the Katyn massacre, whose site is commemorated approximately 19 km west of Smolensk.[57][58] Law enforcement and emergency services Poland has a highly developed system of law enforcement with a long history of effective policing by the State Police Service. The structure of law enforcement agencies within Poland is a multi-tier one, with the State Police providing criminal-investigative services, Municipal Police serving to maintain public order and a number of other specialised agencies, such as the Polish Border Guard, acting to fulfil their assigned missions. In addition to these state services, private security companies are also common, although they possess no powers assigned to state agencies, such as, for example, the power to make an arrest or detain a suspect. Emergency services in Poland consist of the Emergency Medical Services, Search and Rescue units of the Polish Armed Forces and State Fire Service. Emergency medical services in Poland are, unlike other services, provided for by local and regional government. Since joining the European Union all of Poland's emergency services have been undergoing major restructuring and have, in the process, acquired large amounts of new equipment and staff.[59] All emergency services personnel are now uniformed and can be easily recognised thanks to a number of innovative design features, such as reflective paint and printing, present throughout their service dress and vehicle liveries. In addition to this, in an effort to comply with EU standards and safety regulations, the police and other agencies have been steadily replacing and modernising their fleets of vehicles; this has left them with thousands of new auto-mobiles, as well as many new aircraft, boats and helicopters.[60] Economy Poland's high-income economy[61] is considered to be one of the healthiest of the post-Communist countries and is currently one of the fastest growing within the EU. Since the fall of the communist government, Poland has steadfastly pursued a policy of liberalising the economy and today stands out as a successful example of the transition from a centrally planned economy to a primarily market-based economy. Poland is the only member of the European Union to have avoided a decline in GDP during the late 2000s recession. In 2009 Poland had the highest GDP growth in the EU. As of November 2009, the Polish economy has not entered the global recession of the late 2000s nor has it even contracted.[62][63] The privatization of small and medium state-owned companies and a liberal law on establishing new firms have allowed the development of an aggressive private sector. As a consequence, consumer rights organizations have also appeared. Restructuring and privatisation of "sensitive sectors" such as coal, steel, rail transport and energy has been continuing since 1990. Between 2007 and 2010, the government plans to float twenty public companies on the Warsaw Stock Exchange, including parts of the coal industry. The biggest privatisations have been the sale of the national telecoms firm Telekomunikacja Polska to France Télécom in 2000, and an issue of 30% of the shares in Poland's largest bank, PKO Bank Polski, on the Polish stockmarket in 2004.  Poland has a large number of private farms in its agricultural sector, with the potential to become a leading producer of food in the European Union. Structural reforms in health care, education, the pension system, and state administration have resulted in larger-than-expected fiscal pressures. Warsaw leads Central Europe in foreign investment.[64] GDP growth had been strong and steady from 1993 to 2000 with only a short slowdown from 2001 to 2002. The economy had growth of 3.7% annually in 2003, a rise from 1.4% annually in 2002. In 2004, GDP growth equaled 5.4%, in 2005 3.3% and in 2006 6.2%.[65] According to Eurostat data, Polish PPS GDP per capita stood at 61% of the EU average in 2009.[66]  Although the Polish economy is currently undergoing economic development, there are many challenges ahead. The most notable task on the horizon is the preparation of the economy (through continuing deep structural reforms) to allow Poland to meet the strict economic criteria for entry into the Eurozone. According to the minister of finance Jacek Rostowski, Poland is likely to adopt the euro in 2012[67] or 2013.[68][69] Some businesses may already accept the euro as payment. In addition, the ability to establish and conduct business easily has been cause for economic hardship as the World Economic Forum recently ranked Poland near the bottom of OECD countries in terms of the clarity, efficiency and neutrality of its legal framework for firm to settle disputes.[70] A report concluded that on-going foreign business disputes issues may “have damaged Poland’s reputation as an attractive location for FDI” by reinforcing the impression of “Poland’s substandard reputation for maintaining an efficient and neutral framework to settle business disputes involving multinational foreign investors.”[71] Ernst & Young's 2010 European attractiveness survey reported that Poland saw a 52% decrease in FDI job creation and a 42% decrease in number of FDI projects since 2008.[72] Average salaries in the enterprise sector in December 2010 were 3,848 PLN (1,012 euro or 1,374 US dollars)[73] and growing sharply.[74] Salaries vary between the regions: the median wage in the capital city Warsaw was 4,603 PLN (1,177 euro or 1,680 US dollars) while in Kielce it was only 3,083 PLN (788 euro or 1125 US dollars). Differences in salaries in various districts of Poland is even higher and range from 2,020 PLN (517 euro or 737 US dollars) in Kępno County, which is located in Greater Poland Voivodeship to 5,616 (1,436 euro or 2,050 US dollars) in Lubin County, which lies in Lower Silesian Voivodeship.[75] According to a Credit Suisse report, Poles are the second wealthiest (after Czechs) of the Central European peoples.[76][77] This makes Poland an attractive destination for many guest workers from Asia and Eastern Europe. Even though Poland is rather an ethnically homogeneous country, the number of foreigners is growing every year.[78] Since the United Kingdom, Ireland and some other European countries opened their job markets for Poles, many workers, especially from rural regions, have left the country to seek a better wages abroad. However, there is a rapid growth of the salaries, booming economy, strong value of Polish currency, and quickly decreasing unemployment (from 14.2% in May 2006 to 6.7% in August 2008).[79] Commodities produced in Poland include: electronics, cars (including the luxurious Leopard car), buses (Autosan, Solaris, Solbus), helicopters (PZL Świdnik), transport equipment, locomotives, planes (PZL Mielec), ships, military engineering (including tanks, SPAAG systems), medicines (Polpharma, Polfa), food, clothes, glass, pottery (Bolesławiec), chemical products and others. Corporations  Poland is recognised as a regional economic power within Central Europe, possessing nearly 40 percent of the 500 biggest companies in the region (by revenues).[80] Poland was the only member of the EU to avoid the recession of the late 2000s, a testament to the Polish economy's stability.[81] The country's most competitive firms are components of the WIG20 which is traded on the Warsaw Stock Exchange. Well known Polish brands include, amongst others, Tyskie, LOT Polish Airlines, PKN Orlen, E. Wedel, Empik, Poczta Polska, PKO Bank, PKP, Mostostal, PZU Insurance, and TVP.[82] Poland is recognised as having an economy with significant development potential, overtaking the Netherlands in mid-2010 to become Europe's sixth largest economy.[83] Foreign Direct Investment in Poland has remained strong ever since the country's re-democratisation following the Round Table Agreement in 1989. Despite this, problems do exist, and further progress in achieving success depends largely on the government's privatisation of Poland's remaining state industries and continuing development and modernisation of the economy. The list includes the largest companies by turnover in 2009, but does not include major banks or insurance companies: