Jesus

Jesus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7–2 BC/BCE[1] |

| Died | 30–36 AD/CE[3] Judea, Roman Empire |

| Cause of death | Crucifixion[4] |

| Part of a series on |

|

Jesus (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈdʒiːzəs/; Greek: Ἰησοῦς, translit. Iēsous; 7–2 BC/BCE to 30–36 AD/CE), also referred to as Jesus of Nazareth, is the central figure of Christianity, whom the teachings of most Christian denominations hold to be the Son of God.[6] Christians hold Jesus to be the awaited Messiah of the Old Testament and refer to him as Jesus Christ or simply Christ,[7] a name that is also used by non-Christians. Jesus is also considered to be a prophet in Islam.

Virtually all modern scholars of antiquity agree that a historical Jesus existed,[8] although there is little agreement on the reliability of the gospel narratives and their theological assertions of his divinity.[9] Most scholars agree that Jesus was a Jewish teacher from Galilee, was baptized by John the Baptist, and was crucified in Jerusalem on the orders of the Roman prefect, Pontius Pilate.[10][11] Scholars have offered various portraits of the historical Jesus, which at times share a number of overlapping attributes, such as the leader of an apocalyptic movement, Messiah, a charismatic healer, a sage and philosopher, or a social reformer who preached of the "Kingdom of God" as a means for personal and egalitarian social transformation.[12][13] Scholars have correlated the New Testament accounts with non-Christian historical records to arrive at an estimated chronology of Jesus' life.[14][15]

Most Christians believe that Jesus was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of a virgin, performed miracles, founded the Church, died sacrificially by crucifixion to achieve atonement, rose from the dead, and ascended into heaven, from which he will return.[16] The majority of Christians worship Jesus as the incarnation of God the Son, who is the Second Person of the Holy Trinity.[17] A few Christian groups reject Trinitarianism, wholly or partly, as non-scriptural.[17][18]

In Islam, Jesus (commonly transliterated as Isa) is considered one of God's important prophets.[19] To Muslims, Jesus is a bringer of scripture, and the product of a virgin birth, but not the victim of crucifixion. Judaism rejects the belief that Jesus was the awaited Messiah, arguing that he did not fulfill the Messianic prophecies in the Tanakh.[20] Bahá'í scripture almost never refers to Jesus as the Messiah, but calls him a Manifestation of God.[21]

Etymology of names

In the Christian Bible, Jesus is referred to as "Jesus from Nazareth" (Matthew 21:11), "Joseph's son" (Luke 4:12), and "Jesus son of Joseph from Nazareth" (John 1:45). Paul the Apostle most often referred to Jesus as "Jesus Christ", "Christ Jesus", or "Christ".[22] In the Quran, the central religious text of Islam, he is referred to as Template:Rtl-lang (‘Īsa).[23][24]

"Jesus" is a Latin transliteration, occurring in a number of languages and based on the Greek Ἰησοῦς (Iēsoûs).[25] The Greek form is a hellenization of the Aramaic/Hebrew Template:Rtl-lang (Yēšūă‘) which is a post-Exilic modification of the Hebrew Template:Rtl-lang (Yĕhōšuă‘, Joshua) under influence from Aramaic.[26] The etymology of the name Jesus in the context of the New Testament is generally expressed as "Yahweh saves"[27] or "Yahweh is salvation".[28] The name Jesus appears to have been in use in Judea at the time of the birth of Jesus.[29] The first century works of historian Flavius Josephus refer to at least twenty different people with the name Jesus.[30] Philo's reference in Mutatione Nominum item 121 indicates that the etymology of the name Joshua was known outside Judea at the time.[31]

"Christ" (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈkraɪst/) is derived from the Greek Χριστός (Khrīstos), meaning "the anointed" or "the anointed one", a translation of the Hebrew מָשִׁיחַ (Māšîaḥ), usually transliterated into English as "Messiah" (/[invalid input: 'icon']m[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈsaɪ.ə/).[32] In the Septuagint version of the Hebrew Bible (written well over a century before the time of Jesus), the word "Christ" (Χριστός) was used to translate the Hebrew word "Messiah" (מָשִׁיחַ) into Greek.[33] In Matthew 16:16, the apostle Peter's profession "You are the Christ" identifies Jesus as the Messiah.[34] In postbiblical usage, "Christ" became viewed as a name, one part of "Jesus Christ", but originally it was a title ("Jesus the Anointed").[35]

Chronology

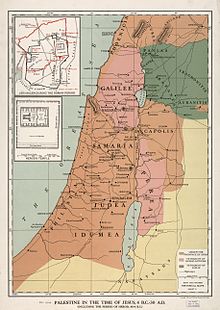

Most scholars agree that Jesus was a Galilean Jew who was born around the beginning of the first century and died 30–36 AD/CE in Judea.[36] Amy-Jill Levine states that the general scholarly consensus is that Jesus was a contemporary of John the Baptist and was crucified by Roman governor Pontius Pilate who reigned 26–36 AD/CE.[37] Most scholars hold that Jesus lived in Galilee and Judea, and did not preach or study elsewhere.[38][39][40]

The general scholarly agreement on the historicity of the interaction of Jesus with John the Baptist and Pontius Pilate shapes the approximate chronological picture. In the Antiquities of the Jews, first century historian Josephus places the execution of the Baptist before the defeat of Herod Antipas by Aretas IV which took place in 36 AD/CE;[41][42] and the dates for the reign of Pontius Pilate are well established by Roman sources.[43]

Two independent approaches have been used to estimate the year of the birth of Jesus; one combines the Nativity accounts in the Gospels with other historical data, the other works backwards from the estimation of the start of the his ministry.[44] The first approach uses Matthew 2:1's association of the birth of Jesus with the reign of Herod the Great, who died around 4 BC/BCE and Luke 1:5's mention of the reign of Herod shortly before the birth of Jesus.[45] However, Luke's gospel also associates the birth with the first census, which was in 6 AD/CE.[46] The second approach ignores the Nativity accounts, and correlates John 2:13–20's statement about the Jerusalem Temple being in its 46th year of construction, with Josephus' dating of the death of John the Baptist to work backwards from the statement in Luke 3:23 that Jesus was "about 30 years of age" at the start of his ministry.[47] This approach indicates that around 27–29 AD/CE, Jesus was "about thirty years of age".[48] Elsewhere, John 8:57 states that Jesus was less than fifty years old. Some scholars thus estimate the year 28 AD/CE to be roughly the 32nd birthday of Jesus.[49][50] Most scholars assume a date of birth between 6 and 4 BC/BCE,[51] but some say it's between 7 and 2 BC/BCE.[52]

The years of ministry of Jesus have been estimated with three different approaches.[53][48][54] The first approach uses the dates for Tiberius' reign and combines them with Luke 3:1–2's reference to its 15th year as the start of the ministry of John the Baptist and Acts 10:37–38's reference to John's ministry preceding that of Jesus to arrive at a date around 28–29 AD/CE.[55][48][56] The second approach uses John 2:13–20's statement about the Temple, Josephus' statement that the temple's reconstruction was started by Herod in the 18th year of his reign to estimate a date around 27–29 AD/CE.[14] A third method uses the date of the death of John the Baptist and the marriage of Herod Antipas to Herodias based on the writings of Josephus, and correlates it with Matthew 14:4 and Mark 6:18.[41] Given that most scholars date the marriage of Herod and Herodias as AD/CE 28–35 this yields a date about 28–29 AD/CE.[53][57][50][58]

A number of approaches have been used to estimate the date of the crucifixion of Jesus, scholars generally agreeing that he died between 30–36 AD/CE.[3] One approach relies on the dates of the prefecture of Pontius Pilate who was the Roman governor of Judea from 26 AD/CE until 36 AD/CE, after which he was replaced by Marcellus, 36–37 AD.[59][60][61] Another approach which provides an upper bound for the year of death of Jesus is working backwards from the chronology of Apostle Paul, which can be historically pegged to his trial in Achaea, Greece, by Roman proconsul Gallio, the date of whose reign is confirmed in the Delphi Inscription discovered in the 20th century at the Temple of Apollo.[62][63] The estimation of the date of the conversion of Paul places the death of Jesus before this conversion, which is estimated at around 33–36 AD/CE.[62][63][64] Isaac Newton was one of the first astronomers to estimate the date of the crucifixion and suggested Friday, April 3, 34 AD/CE.[65][66] In 1990 astronomer Bradley E. Schaefer computed the date as Friday, April 3, 33 AD/CE.[67] In 1991, John Pratt stated that Newton's method was sound, but included a minor error at the end. Pratt suggested the year 33 AD/CE as the answer.[65] Using the different approach of a lunar eclipse model, Humphreys and Waddington arrived at the conclusion that Friday, April 3, 33 AD/CE was the date of the crucifixion.[68][69][70]

Life and teachings in the New Testament

Although the four canonical gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, are the main sources for the biography of Jesus' life, other parts of the New Testament, such as the Pauline epistles which were likely written decades before them, also include references to key episodes in his life, such as the Last Supper in 1 Corinthians 11:23–26.[71][72][73] The Acts of the Apostles (10:37–38 and 19:4) refers to the early ministry of Jesus and its anticipation by John the Baptist.[74][75] Acts 1:1–11 says more about the Ascension episode (also mentioned in 1 Timothy 3:16) than the canonical gospels.[76]

According to the majority viewpoint, the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) are the primary sources of historical information about Jesus,[77][78] and of the religious movement he founded, but not everything contained in the gospels is considered to be historically reliable.[9] Elements whose historical authenticity are disputed include the two accounts of the Nativity of Jesus, as well as the resurrection and certain details about the crucifixion.[79][80][81] Views on the gospels range from the accounts being inerrant descriptions of the life of Jesus[82] to the accounts providing no historical information about his life.[83]

Canonical gospel accounts

Three of the four canonical gospels, namely Matthew, Mark, and Luke, are known as the synoptic Gospels, from the Greek σύν (syn "together") and ὄψις (opsis "view"), given that they display a high degree of similarity in content, narrative arrangement, language and paragraph structure.[84][85][86] The presentation in the fourth canonical gospel, John, differs from these three in that it has more of a thematic nature rather than a narrative format.[87][88] Scholars generally agree that it is impossible to find any direct literary relationship between the synoptic gospels and the Gospel of John.[87]

However, in general, the authors of the New Testament showed little interest in an absolute chronology of Jesus or in synchronizing the episodes of his life with the secular history of the age.[89] The gospels were primarily written as theological documents in the context of early Christianity with the chronological timelines as a secondary consideration.[90] One manifestation of the gospels being theological documents rather than historical chronicles is that they devote about one third of their text to just seven days, namely the last week of the life of Jesus in Jerusalem, referred to as Passion Week.[91]

Although the gospels do not provide enough details to satisfy the demands of modern historians regarding exact dates, it is possible to draw from them a general picture of the life story of Jesus.[89][90][92] However, as stated in John 21:25 the gospels do not claim to provide an exhaustive list of the events in the life of Jesus.[93] Since the 2nd century attempts have been made to harmonize the gospel accounts into a single narrative; Tatian's Diatesseron perhaps being the first.[94] There are differences in specific temporal sequences in the gospel accounts, in the parables and miracles listed in each gospel, and while the flow of the some events such as Baptism, Transfiguration and Crucifixion and interactions with people such as the Apostles are shared among the synoptic gospel narratives, events such as the Transfiguration do not appear in John's Gospel which also differs on other issues such as the Cleansing of the Temple.[89][90][95][96]

Key elements and the five major milestones

The five major milestones in the gospel narrative of the life of Jesus are his Baptism, Transfiguration, Crucifixion, Resurrection and Ascension.[97][98][99] These are usually bracketed by two other episodes: his Nativity at the beginning and the sending of the Holy Spirit at the end.[97][99] The gospel accounts of the teachings of Jesus are often presented in terms of specific categories involving his "works and words", e.g. his ministry, parables and miracles.[100][101]

The gospels include a number of discourses by Jesus on specific occasions, such as the Sermon on the Mount or the Farewell Discourse. They also include over 30 parables, spread throughout the narrative, often with themes that relate to the sermons.[102] John 14:10 stresses the importance of the words of Jesus, and attributes them to the authority of God the Father.[103][104] The gospel episodes that include descriptions of the miracle of Jesus also often include teachings, providing an intertwining of his "words and works" in the gospels.[101][105]

Genealogy and Nativity

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

The accounts of the genealogy and Nativity of Jesus in the New Testament appear only in the Gospel of Luke and the Gospel of Matthew. While there are documents outside of the New Testament which are more or less contemporary with Jesus and the gospels, many shed no light on the more biographical aspects of his life and these two gospel accounts remain the main sources of information on the genealogy and Nativity.[92]

Matthew begins his gospel in 1:1 with the genealogy of Jesus, and presents it before the account of the birth of Jesus, while Luke discusses the genealogy in chapter 3, after the Baptism of Jesus in Luke 3:22 when the voice from Heaven addresses Jesus and identifies him as the Son of God.[106] At that point Luke traces Jesus' ancestry through Adam to God.[106]

The Nativity is a prominent element in the Gospel of Luke. It comprises over 10 percent of the text, and is three times the length of the nativity text in Matthew.[107] Luke's account takes place mostly before the birth of Jesus and centers on Mary, while Matthew's takes place mostly after the birth of Jesus and centers on Joseph.[108][109][110] According to Luke and Matthew, Jesus was born to Joseph and Mary, his betrothed, in Bethlehem. Both support the doctrine of the Virgin Birth in which Jesus was miraculously conceived in his mother's womb by the Holy Spirit, when his mother was still a virgin.[111][112]

In Luke 1:31–38 Mary learns from the angel Gabriel that she will conceive and bear a child called Jesus through the action of the Holy Spirit.[109][111] Following his betrothal to Mary, Joseph is troubled in Matthew 1:19–20 because Mary is pregnant, but in the first of Joseph's three dreams an angel assures him not be afraid to take Mary as his wife, because her child was conceived by the Holy Spirit.[113] When Mary is due to give birth, she and Joseph travel from Nazareth to Joseph's ancestral home in Bethlehem to register in the census of Quirinius. In Luke 2:1–7. Mary gives birth to Jesus and, having found no room for themselves in the inn, places the newborn in a manger. An angel visits the shepherds and sends them to adore the child in Luke 2:22. After presenting Jesus at the Temple, Joseph and Mary return home to Nazareth.[109][111] In Matthew 1:1–12, the Wise Men or Magi bring gifts to the young Jesus as the King of the Jews. King Herod hears of Jesus' birth, but before the Massacre of the Innocents Joseph is warned by an angel in his dream and the family flees to Egypt, after which they return and settle in Nazareth.[113][114][115]

Early life and profession

In the Gospels of Luke and Matthew, Jesus' childhood home is identified as the town of Nazareth in Galilee. Joseph, husband of Mary, appears in descriptions of Jesus' childhood and no mention is made of him thereafter.[116] The New Testament books of Matthew, Mark, and Galatians mention Jesus' brothers and sisters, but the Greek word adelphos in these verses, has also been translated as brother or kinsman.[117]

In Mark 6:3 Jesus is called a tekton (τέκτων in Greek), usually understood to mean carpenter. Matthew 13:55 says he was the son of a tekton.[32]: 170 Tekton has been traditionally translated into English as "carpenter", but it is a rather general word (from the same root that leads to "technical" and "technology") that could cover makers of objects in various materials, even builders.[118][119] Beyond the New Testament accounts, the specific association of the profession of Jesus with woodworking is a constant in the traditions of the 1st and 2nd centuries and Justin Martyr (d. ca. 165) wrote that Jesus made yokes and ploughs.[120]

Baptism and temptation

In the gospels, the accounts of the Baptism of Jesus are always preceded by information about John the Baptist and his ministry.[95][122][123] In these accounts, John was preaching for penance and repentance for the remission of sins and encouraged the giving of alms to the poor (Luke 3:11) as he baptized people in the area of the River Jordan around Perea about the time of the commencement of the ministry of Jesus. The Gospel of John (1:28) specifies "Bethany beyond the Jordan", that is Bethabara in Perea, when it initially refers to it and later John 3:23 refers to further baptisms in Ænon "because there was much water there".[124][125]

The four gospels are not the only references to John's ministry around the River Jordan. In Acts 10:37–38, Peter refers to how the ministry of Jesus followed "the baptism which John preached".[75] In the Antiquities of the Jews (18.5.2) 1st century historian Josephus also wrote about John the Baptist and his eventual death in Perea.[126][127]

In the gospels, John had been foretelling (Luke 3:16) of the arrival of a someone "mightier than I".[128][129] Apostle Paul also refers to this anticipation by John in Acts 19:4.[74] In Matthew 3:14, upon meeting Jesus, the Baptist states: "I need to be baptized by you." However, Jesus persuades John to baptize him nonetheless.[130] In the baptismal scene, after Jesus emerges from the water, the sky opens and a voice from Heaven states: "This is my beloved Son with whom I am well pleased". The Holy Spirit then descends upon Jesus as a dove in Matthew 3:13–17, Mark 1:9–11, Luke 3:21–23.[128][129][130] In John 1:29–33 rather than a direct narrative, the Baptist bears witness to the episode.[129][131] This is one of two cases in the gospels where a voice from Heaven calls Jesus "Son", the other being in the Transfiguration of Jesus episode.[132][133]

After the baptism, the synoptic gospels proceed to describe the Temptation of Jesus, but John 1:35–37 narrates the first encounter between Jesus and two of his future disciples, who were then disciples of John the Baptist.[134][135] In this narrative, the next day the Baptist sees Jesus again and calls him the Lamb of God and the "two disciples heard him speak, and they followed Jesus".[131][134][136]

Ministry

Luke 3:23 states that Jesus was "about 30 years of age" at the start of his ministry.[53][55] The date of the start of his ministry has been estimated at around 27–29 AD/CE, based on independent approaches which combine separate gospel accounts with other historical data.[53][55][48][56] The end of his ministry is estimated to be in the range 30–36 AD/CE.[53][62][55][137]

The gospel accounts place the beginning of Jesus' ministry in the countryside of Judea, near the River Jordan.[123] Jesus' ministry begins with his Baptism by John the Baptist (Matthew 3, Luke 3), and ends with the Last Supper with his disciples (Matthew 26, Luke 22) in Jerusalem.[122][123] The gospels present John the Baptist's ministry as the precursor to that of Jesus and the Baptism as marking the beginning of Jesus' ministry, after which Jesus travels, preaches and performs miracles.[95][122][123]

The Early Galilean ministry begins when Jesus goes back to Galilee from the Judaean Desert after rebuffing the temptation of Satan.[138] In this early period Jesus preaches around Galilee and in Matthew 4:18–20 his first disciples encounter him, begin to travel with him and eventually form the core of the early Church.[123][139] This period includes the Sermon on the Mount, one of the major discourses of Jesus.[139][140]

The Major Galilean ministry which begins in Matthew 8 refers to activities up to the death of John the Baptist. It includes the Calming the storm and a number of other miracles and parables.[141][142] The Final Galilean ministry includes the Feeding the 5000 and Walking on water episodes, both in Matthew 14.[143][144] The end of this period (as Matthew 16 and Mark 8 end) establishes a turning point in the ministry of Jesus with the dual episodes of Confession of Peter and the Transfiguration.[145][146][147][148]

As Jesus travels towards Jerusalem, in the Later Perean ministry, about one-third the way down from the Sea of Galilee along the Jordan, he returns to the area where he was baptized, and in John 10:40–42.[149][150] The Final ministry in Jerusalem is sometimes called the Passion Week and begins with the Jesus' triumphal entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday.[151] In that week in the synoptic gospels Jesus drives the money changers from the Temple, and Judas bargains to betray him. John's Gospel places the Temple incident during the early part of Jesus' ministry, and scholars differ on whether these are one or two separate incidents.[152] This period culminates in the Last Supper, and the Farewell discourse. The accounts of the ministry of Jesus generally end with the Last Supper.[95][151][153]

Teachings and preachings

In the New Testament the teachings of Jesus are presented in terms of his "words and works".[100][101] The words of Jesus include a number of sermons, as well as parables that appear throughout the narrative of the synoptic gospels (the Gospel of John includes no parables). The works include the miracles and other acts performed during his ministry.[101] Although the canonical gospels are the major source of the teachings of Jesus, the Pauline epistles, which were likely written decades before the gospels, provide some of the earliest written accounts of the teachings of Jesus.[71]

The New Testament does not present the teachings of Jesus as merely his own preachings, but equates the words of Jesus with divine revelation, with John the Baptist stating in John 3:34: "For the one whom God has sent speaks the words of God, for God gives the Spirit without limit"; and in John 7:16: "Jesus answered, 'My teaching is not my own. It comes from the one who sent me.'" Again he re-asserted that in John 14:10: "Don't you believe that I am in the Father, and that the Father is in me? The words I say to you I do not speak on my own authority. Rather, it is the Father, living in me, who is doing his work."[104][154] In Matthew 11:27 Jesus claims divine knowledge, stating: "No one knows the Son except the Father and no one knows the Father except the Son", asserting the mutual knowledge he has with the Father.[155][156]

Parables represent a major component of the teachings of Jesus in the gospels, the approximately thirty parables forming about one third of his recorded teachings.[102][103] The parables may appear within longer sermons, as well as other places within the narrative.[157] Jesus' parables are seemingly simple and memorable stories, often with imagery, and each conveys a teaching which usually relates the physical world to the spiritual world.[158][159]

The gospel episodes that include descriptions of the miracle of Jesus also often include teachings, providing an intertwining of his "words and works" in the gospels.[101][105] Many of the miracles in the gospels teach the importance of faith, for instance in Cleansing ten lepers and Daughter of Jairus the beneficiaries are told that they were healed due to their faith.[160][161]

Proclamation as Christ and Transfiguration

At about the middle of each of the three synoptic gospels, two related episodes mark a turning point in the narrative: the Confession of Peter and the Transfiguration of Jesus.[145][146] These episodes begin in Caesarea Philippi just north of the Sea of Galilee at the beginning of the final journey to Jerusalem which ends in the Passion and Resurrection of Jesus.[162] These episodes mark the beginnings of the gradual disclosure of the identity of Jesus to his disciples; and his prediction of his own suffering and death.[132][133][145][146][162]

Peter's Confession begins as a dialogue between Jesus and his disciples in Matthew 16:13, Mark 8:27 and Luke 9:18. Jesus asks his disciples: "But who do you say that I am?" Simon Peter answers him: "You are the Christ, the Son of the living God."[162][163][164] In Matthew 16:17 Jesus replied, "Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah, for this was not revealed to you by flesh and blood, but by my Father in heaven". In blessing Peter, Jesus not only accepts the titles "Christ" and "Son of God" which Peter attributes to him, but declares the proclamation a divine revelation by stating that his Father in Heaven had revealed it to Peter.[165] In this assertion, by endorsing both titles as divine revelation, Jesus unequivocally declares himself to be both Christ and the Son of God.[165][166]

The account of the Transfiguration of Jesus appears in Matthew 17:1–9, Mark 9:2–8, and Luke 9:28–36.[132][133][145] Jesus takes Peter and two other apostles with him and goes up to a mountain, which is not named. Once on the mountain, Matthew (17:2) states that Jesus "was transfigured before them; his face shining as the sun, and his garments became white as the light".[167] A bright cloud appears around them, and a voice from the cloud states: "This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him".[132] The Transfiguration not only supports the identity of Jesus as the Son of God (as in his Baptism), but the statement "listen to him" identifies him as the messenger and mouth-piece of God.[168]

Final week: betrayal, arrest, trial, and death

The description of the last week of the life of Jesus (often called the Passion week) occupies about one third of the narrative in the canonical gospels.[91] The narrative for that week starts by a description of the final entry into Jerusalem, and ends with his crucifixion.[95][151]

The last week in Jerusalem is the conclusion of the journey which Jesus had started in Galilee through Perea and Judea.[151] Just before the account of the final entry of Jesus into Jerusalem, the Gospel of John includes the Raising of Lazarus episode, which builds the tension between Jesus and the authorities.[151]

Final entry into Jerusalem

In the four canonical gospels, Jesus' Triumphal entry into Jerusalem takes place at the beginning of the last week of his life, a few days before the Last Supper, marking the beginning of the Passion narrative.[170][171][172][173][174] After leaving Bethany Jesus rides a donkey into Jerusalem, with Mark and John specifying Sunday, Matthew Monday, and Luke not mentioning the day.[170][171][172] As Jesus rode into Jerusalem the people there laid down their cloaks in front of him, and also lay down small branches of trees and sang part of Psalm 118: 25–26.[170][175][171][172] The cheering crowds who greeted Jesus he entered Jerusalem added to the tension between him and the authorities.[151]

In the three synoptic gospels, entry into Jerusalem is followed by the Cleansing of the Temple episode, in which Jesus expels the money changers from the Temple, accusing them of turning the Temple to a den of thieves through their commercial activities. This is the only account of Jesus using physical force in any of the gospels.[155][152][176] John 2:13–16 includes a similar narrative much earlier, and scholars debate if these refer to the same episode.[155][152][176] The synoptics include a number of well known parables and sermons such as the Widow's mite and the Second Coming Prophecy during the week that follows.[171][172]

In that week, the synoptics also narrate conflicts between Jesus and the elders of the Jews, in episodes such as the Authority of Jesus Questioned and the Woes of the Pharisees in which Jesus criticizes their hypocrisy.[171][172] Judas Iscariot, one of the twelve apostles approaches the Jewish elders and performs the "Bargain of Judas" in which he accepts to betray Jesus and hand him over to the elders.[177][178][179] Matthew specifies the price as thirty silver coins.[178]

Last Supper

In the New Testament, the Last Supper is the final meal that Jesus shares with his twelve apostles in Jerusalem before his crucifixion. The Last Supper is mentioned in all four canonical gospels, and Paul's First Epistle to the Corinthians (11:23–26), which was likely written before the gospels, also refers to it.[72][73][180][181]

In all four gospels, during the meal, Jesus predicts that one of his Apostles will betray him.[182] Jesus is described as reiterating, despite each Apostle's assertion that he would not betray Jesus, that the betrayer would be one of those who were present. In Matthew 26:23–25 and John 13:26–27 Judas is specifically singled out as the traitor.[72][73][182]

In Matthew 26:26–29, Mark 14:22–25, Luke 22:19–20 Jesus takes bread, breaks it and gives it to the disciples, saying: "This is my body which is given for you".[72][183] Although the Gospel of John does not include a description of the bread and wine ritual during the Last Supper, most scholars agree that John 6:58–59 (the Bread of Life Discourse) has a Eucharistic nature and resonates with the "words of institution" used in the synoptic gospels and the Pauline writings on the Last Supper.[184]

In all four gospels Jesus predicts that Peter will deny knowledge of him, stating that Peter will disown him three times before the rooster crows the next morning. The synoptics mention that after the arrest of Jesus Peter denied knowing him three times, but after the third denial, heard the rooster crow and recalled the prediction as Jesus turned to look at him. Peter then began to cry bitterly.[185][186]

The Gospel of John provides the only account of Jesus washing his disciples' feet before the meal.[114] John's Gospel also includes a long sermon by Jesus, preparing his disciples (now without Judas) for his departure. Chapters 14–17 of the Gospel of John are known as the Farewell discourse given by Jesus, and are a significant source of Christological content.[187][188]

Agony in the Garden, betrayal and arrest

In Matthew 26:36–46, Mark 14:32–42, Luke 22:39–46 and John 18:1, immediately after the Last Supper, Jesus takes a walk to pray, Matthew and Mark identifying this place of prayer as Garden of Gethsemane.[189][190] While in the Garden, Judas appears, accompanied by a crowd that includes the Jewish priests and elders and people with weapons. Judas gives Jesus a kiss to identify him to the crowd who then arrests Jesus.[190][191] One of Jesus' disciples tries to stop them and uses a sword to cut off the ear of one of the men in the crowd.[190][191] Luke states that Jesus miraculously healed the wound and John and Matthew state that Jesus criticized the violent act, insisting that his disciples should not resist his arrest. In Matthew 26:52 Jesus makes the well known statement: all who live by the sword, shall die by the sword.[190][191] Prior to the arrest, in Matthew 26:31 Jesus tells the disciples: "All ye shall be offended in me this night" and in 32 that: "But after I am raised up, I will go before you into Galilee." After his arrest, Jesus' disciples go into hiding.[190]

Trials by the Sanhedrin, Herod and Pilate

In the narrative of the four canonical gospels after the betrayal and arrest of Jesus, he is taken to the Sanhedrin, a Jewish judicial body.[192] Jesus is tried by the Sanhedrin, mocked and beaten and is condemned for making claims of being the Son of God.[191][193][194] He is then taken to Pontius Pilate, and the Jewish elders ask Pilate to judge and condemn Jesus—accusing him of claiming to be the King of the Jews.[194] After questioning, with few replies provided by Jesus, Pilate publicly declares that he finds Jesus innocent, but the crowd insists on punishment. Pilate then orders Jesus' crucifixion.[191][193][194][195]

The gospel accounts differ on various elements of the trials.[195] In, Matthew 26:57, Mark 14:53 and Luke 22:54 Jesus was taken to the high priest's house where he was mocked and beaten that night. The next day, early in the morning, the chief priests and scribes lead Jesus away into their council.[191][193][194][197] In John 18:12–14, however, Jesus is first taken to Annas, the father-in-law of Caiaphas, and then to Caiaphas.[191][193][194] All four gospels include the Denial of Peter narrative, where Peter denies knowing Jesus three times, at which point the rooster crows as predicted by Jesus.[193][198]

In the gospel accounts Jesus speaks very little, mounts no defense and gives very infrequent and indirect answers to the questions of the priests, prompting an officer to slap him. In Matthew 26:62 the lack of response from Jesus prompts the high priest to ask him: "Answerest thou nothing?"[191][193][194][199] In Mark 14:61 the high priest then asked Jesus: "Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed?" And Jesus said, "I am"—at which point the high priest tore his own robe in anger and accused Jesus of blasphemy. In Luke 22:70 when asked: "Are you then the Son of God?" Jesus answers: "You say that I am" affirming the title Son of God.[191][193][194][200]

Taking Jesus to Pilate's Court, the Jewish elders ask Pontius Pilate to judge and condemn Jesus—accusing him of claiming to be the King of the Jews.[194] In Luke 23:7–15 Pilate realizes that Jesus is a Galilean, and is thus under the jurisdiction of Herod Antipas.[201][202] [203] Pilate sends Jesus to Herod to be tried.[204] However, Jesus says almost nothing in response to Herod's questions. Herod and his soldiers mock Jesus, put a gorgeous robe on him, as the King of the Jews, and send him back to Pilate.[201] Pilate then calls together the Jewish elders, and says that he has "found no fault in this man."[204]

The use of the term king is central in the discussion between Jesus and Pilate. In John 18:36 Jesus states: "My kingdom is not of this world", but does not directly deny being the King of the Jews.[205][206] Pilate then writes "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews" as a sign (abbreviated as INRI in depictions) to be affixed to the cross of Jesus.[207]

The trial by Pilate is followed by the flagellation episode, the soldiers mock Jesus as the King of Jews by putting a purple robe (that signifies royal status) on him, place a Crown of Thorns on his head, and beat and mistreat him in Matthew 27:29–30, Mark 15:17–19 and John 19:2–3.[208] Jesus is then sent to Calvary for crucifixion.[191][193][194]

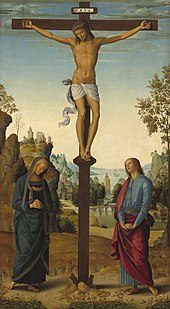

Crucifixion and burial

Jesus' crucifixion is described in all four canonical gospels, is attested to by other sources of that age, including Josephus and Tacitus, and is regarded as an historical event.[81][209][210]

After the trials, Jesus made his way to Calvary (the path is traditionally called via Dolorosa) and the three synoptic gospels indicate that he was assisted by Simon of Cyrene, the Romans compelling him to do so.[211][212] In Luke 23:27–28 Jesus tells the women in the multitude of people following him not to cry for him but for themselves and their children.[211] Once at Calvary (Golgotha), Jesus was offered wine mixed with gall to drink – usually offered as a form of painkiller. Matthew's and Mark's gospels state that he refused this.[211][212]

The soldiers then crucified Jesus and cast lots for his clothes. Above Jesus' head on the cross was the inscription King of the Jews, and the soldiers and those passing by mocked him about the title. Jesus was crucified between two convicted thieves, one of whom rebuked Jesus, while the other defended him.[211][213]

The Roman soldiers did not break Jesus' legs, as they did to the other two men crucified (breaking the legs hastened the crucifixion process), as Jesus was dead already. One of the soldiers traditionally known as Saint Longinus, pierced the side of Jesus with a lance and water flowed out.[213] In Mark 15:39, impressed by the events, the Roman centurion calls Jesus the Son of God.[211][212][214][215]

Following Jesus' death on Friday, Joseph of Arimathea asked the permission of Pilate to remove the body. The body was removed from the cross, was wrapped in a clean cloth and buried in a new rock-hewn tomb, with the assistance of Nicodemus.[211] In Matthew 27:62–66 the Jews go to Pilate the day after the crucifixion and ask for guards for the tomb and also seal the tomb with a stone as well as the guard, to be sure the body remains there.[211][216]

Resurrection and ascension

The New Testament accounts of the resurrection and ascension of Jesus, state that the first day of the week after the crucifixion (typically interpreted as a Sunday), his followers encounter him risen from the dead, after his tomb is discovered to be empty.[76][217][218] The resurrected Jesus appears to them that day and a number of times thereafter, delivers sermons and commissions them, before ascending to Heaven.[76][218] When the tomb is discovered empty (Matthew 28:5, Mark 16:5, Luke 24:4 and John 20:12) his followers arrive there early in the morning meet either one or two beings (either men or angels) dressed in bright robes who appear in or near the tomb.[76][218] Mark 16:9 and John 20:15 indicate that Jesus appeared to Mary Magdalene first, and Luke 16:9 states that she was among the Myrrhbearers.[76][218]

After the discovery of the empty tomb, the gospels indicate that Jesus made a series of appearances to the disciples.[76] These include the well known Doubting Thomas episode and the Road to Emmaus appearance where Jesus meets two disciples. The catch of 153 fish appearance includes a miracle at the Sea of Galilee, and thereafter Jesus encourages Peter to serve his followers.[76][218] The final post-resurrection appearance in the gospel accounts is when Jesus ascends to Heaven.[76] Luke 24:51 states that Jesus "was carried up into heaven". The ascension account is elaborated in Acts 1:1–11 and mentioned 1 Timothy 3:16. In Acts 1:1–9, forty days after the resurrection, as the disciples look on, "he was taken up; and a cloud received him out of their sight." 1 Peter 3:22 describes Jesus as being on "the right hand of God, having gone into heaven".[76]

The Acts of the Apostles also contain "post-ascension" appearances by Jesus. These include the vision by Stephen just before his death in Acts 7:55,[219] and the road to Damascus episode in which Apostle Paul is converted to Christianity.[220][221] The instruction given to Ananias in Damascus in Acts 9:10–18 to heal Paul is the last reported conversation with Jesus in the Bible until the Book of Revelation was written.[220][221]

Historical views

Existence

The Christian gospels were written primarily as theological documents rather than historical chronicles.[90][91][224] However, the question of the existence of Jesus as a historical figure should be distinguished from discussions about the historicity of specific episodes in the gospels, the chronology they present, or theological issues regarding his divinity.[225] A number of historical non-Christian documents, such as Jewish and Greco-Roman sources, have been used in historical analyses of the existence of Jesus.[222]

Virtually all scholars of antiquity agree that Jesus existed and regard events such as his baptism and his crucifixion as historical.[226][8][227][228][229] Robert E. Van Voorst states that the idea of the non-historicity of the existence of Jesus has always been controversial, and has consistently failed to convince scholars of many disciplines, and that classical historians, as well as biblical scholars now regard it as effectively refuted.[230] Referring to the theories of non-existence of Jesus, Richard A. Burridge states: "I have to say that I do not know any respectable critical scholar who says that any more."[231]

Separate non-Christian sources used to establish the historical existence of Jesus include the works of 1st century Roman historians Josephus and Tacitus.[222][232] Josephus scholar Louis H. Feldman has stated that "few have doubted the genuineness" of Josephus' reference to Jesus in Antiquities 20, 9, 1 and it is only disputed by a small number of scholars.[223][233] Bart D. Ehrman states that the existence of Jesus and his crucifixion by the Romans is attested to by a wide range of sources, including Josephus and Tacitus.[234]

The historical existence of Jesus as a person is a separate issue from any religious discussions about his divinity, or the theological issues relating to his nature as man or God.[235] Leading scientific atheist Richard Dawkins does not deny the existence of Jesus, although he dismisses the reliability of the gospel accounts.[236] This position is also held by leading critic G. A. Wells, who used to argue that Jesus never existed, but has since changed his views and no longer rejects it.[237][238]

In antiquity, the existence of Jesus was never denied by those who opposed Christianity, and neither pagans nor Jews questioned his existence.[89][239] Although in Dialogue with Trypho, the second century Christian writer Justin Martyr wrote of a discussion about "Christ" with Trypho, most scholars agree that Trypho is a fictional character invented by Justin for his literary apologetic goals.[240][241][242] While theological differences existed among early Christians regarding the nature of Jesus (e.g. monophysitism, miaphysitism, Docetism, Nestorianism, etc.) these were debates in Christian theology, not about the historical existence of Jesus.[243][244] The Christ myth theory appeared in the 18th and 19th centuries, and was debated during the 20th century.[245] Supporters of the Christ myth theory point to the lack of any known written references to Jesus during his lifetime and the relative scarcity of non-Christian references to him in the 1st century, and dispute the veracity of the existing accounts of him.[246]

Since the 20th century scholars such as G. A. Wells, Robert M. Price and Thomas Brodie have presented various (and at times differing) arguments to support the Christ myth theory; the most thorough analysis being by G. A. Wells.[247] But Wells' book Did Jesus Exist? was criticized by James D.G. Dunn in his book The Evidence for Jesus.[248] Wells then changed his stance on issue and accepted that the Q source refers to "a preacher who existed", but still maintains that the New Testament accounts of the preacher's life are mostly fiction.[249][237][250][251] Robert Van Voorst and separately Michael Grant state that biblical scholars and classical historians now regard theories of non-existence of Jesus as effectively refuted.[230][252][253]

Ancient sources and archeology

Professor Bart Ehrman states that "Jesus almost certainly did exist", and the arguments from ignorance that there is no physical or archeological evidence of Jesus nor any writings from him are "not very good arguments, even though they sound good, as there is no such evidence of "nearly anyone who lived in the first century".[254][255] Professor Teresa Okure states that in a global cultural context the existence of historical figures are established by the analysis of later references to them rather than by contemporary relics and remnants.[256] Ehrman states that the view that Jesus had an immense impact on the society of his day, and hence one might have expected contemporary accounts of his deeds is not even close to correct and although Jesus had a large impact on future generations, his impact on the society of his time was "practically nil".[257]

In responding to G. A. Wells' previous arguments from silence that the lack of the contemporary references implies that Jesus did not exist (Wells no longer adheres to the non-existence hypothesis[249]), Robert Van Voorst stated that such arguments are "specially perilous" as every good student of history knows.[250] An example of such argument is that although Philo criticized the brutality of Pontius Pilate in Embassy to Gaius (c. 40 AD), he did not name Jesus as an example of Pilate's cruelty.[258] He adds that a possible explanation is that Philo never mentions Christians at all, so he had no need to mention their founder, given that Jewish literature (like early Roman references) only saw Jesus through Christianity and did not treat him independently.[258] Philo was also silent on the reaction of the Jewish Zealots to the death of Gaius, perhaps because the theme of Embassy to Gaius was providence for Israel.[259] Bernard Green states that Philo's silence on some comparative aspects of the Jewish communities in Rome and Alexandria (e.g. levels of autonomy and turbulence) was deliberate, given the conciliatory nature of his mission to Gauis.[260] According to Eusebius (Hist Eccl II.17) Philo may have become familiar with Christian practices on a subsequent visit to Rome during the reign of Claudius (41 to 54 AD/CE).[261][262]

In a broad context, arguments from silence fail unless a fact is known to the author and is important enough and relevant enough to be mentioned in the context of a document.[263][264] Van Voorst states that the historical interpretation of events was not an "instant analysis" as in modern society but involved time lags and Roman sources came to consider Jesus only when the growth of Christianity came to be seen as a threat to Rome, and given that they viewed Christianity as a "superstition" they had little interest in its origins.[265] Timothy Barnes states that at the turn of the first century, there was only a low level of interest in and awareness of Christians within the Roman Empire, resulting in the lack of any discernible mention of them by Roman authors such as Martial and Juvenal.[266] Louis Feldman states that one reason first century historian Josephus refers to Jesus in the Antiquities of the Jews (written c. 93 AD) but not in the Jewish Wars (written c. 75 AD) may be that in the twenty-year gap between the two works the growth of Christianity had made it a more important topic.[267]

In the broad historical context, a number of scholars caution against the use of arguments from ignorance and consider them generally inconclusive or fallacious, given their reliance on "negative evidence".[268][269][270] Douglas Walton states that arguments from ignorance can only lead to sound conclusions in cases where we can assume that our "knowledge-base is complete".[271] Despite the lack of specific archaeological remnants directly attributed to Jesus, the 21st century has witnessed an increase in scholarly interest in the integrated use of archaeology as an additional research component in arriving at a better understanding of the historical background of Jesus by illuminating the socio-economic and political background of his age.[272][273][274] James Charlesworth states that few modern scholars now want to overlook the archaeological discoveries that clarify the nature of life in Galilee and Judea during the time of Jesus.[273] Jonathan Reed states that chief contribution of archaeology to the study of the historical Jesus is the reconstruction of his social world.[275]

Historicity of events

Modern scholars consider the baptism of Jesus and his crucifixion to be the two historically certain facts about him, James Dunn stating that these "two facts in the life of Jesus command almost universal assent".[226] Dunn states that these two facts "rank so high on the 'almost impossible to doubt or deny' scale of historical facts" that they are often the starting points for the study of the historical Jesus.[226] Bart Ehrman states that the crucifixion of Jesus on the orders of Pontius Pilate is the most certain element about him.[276] John Dominic Crossan states that the crucifixion of Jesus is as certain as any historical fact can be.[209]

Craig Blomberg states that most scholars in the third quest for the historical Jesus consider the crucifixion indisputable.[277] Although scholars agree on the historicity of the crucifixion, they differ on the reason and context for it. Both E.P. Sanders and Paula Fredriksen support the historicity of the crucifixion, but contend that Jesus did not foretell of his own crucifixion, and that his prediction of the crucifixion is a Christian story.[278] Geza Vermes also views the crucifixion a historical event but provides his own explanation and background for it.[278] John P. Meier views the crucifixion of Jesus as historical fact and states that based on the criterion of embarrassment Christians would not have invented the painful death of their leader.[279] Meier states that a number of other criteria, such as the criterion of multiple attestation (confirmation by more than one source), the criterion of coherence (that it fits with other historical elements) and the criterion of rejection (that it is not disputed by ancient sources) help establish the crucifixion of Jesus as a historical event.[280]

Portraits of Jesus

Although scholars agree on basic historical facts such as the crucifixion of Jesus, the various "portraits of Jesus" they construct often differ from each other, and from the descriptions found in the gospels.[281][282]

Since the 18th century, three separate scholarly quests for the historical Jesus have taken place, each with distinct characteristics and based on different research criteria, which were often developed during that phase.[283][284] The second quest which started in 1953 reached a plateau in the 1970s and by 1992 the term third quest had been coined to characterize the new research approaches.[285]

In the third quest, research on the historical Jesus entered a new phase, and although a new emphasis on methods emerged, Gerd Theissen and Dagmar Winter stated that by early 21st century due to the fragmentation of the portraits of Jesus no unified picture of Jesus could be attained at all.[286] Echoing the same scenario, Ben Witherington states that "there are now as many portraits of the historical Jesus as there are scholarly painters".[287]

Thus while there is widespread scholarly agreement on the existence of Jesus, the portraits of Jesus constructed in these quests often differ from each other, and from the image portrayed in the gospel accounts.[286][288] The mainstream profiles in the third quest may be grouped together based on their primary theme as apocalyptic prophet, charismatic healer, Cynic philosopher, Jewish Messiah and an egalitarian prophet of social change.[289][290] There are, however, overlapping attributes among the portraits and pairs of scholars which may differ on some attributes may agree on others.[289][290][291]

There are a number of variants to each of these portraits of Jesus, and some scholars reject the basic elements of some portraits, e.g. regarding the "Messiah portrait" scholars such as Larry Hurtado suggest that Jesus may have never claimed to be the Messiah or the Son of God, and the titles may be later applications.[292][293] Other scholars such as N. T. Wright, Markus Bockmuehl and Peter Stuhlmacher argue that Jesus had a Messianic mission.[294][295] Other scholars contend that although Jesus saw himself as the Messiah, he ordered his followers to silence on his Messianic secret.[296] Although scholars generally agree that Jesus had "followers", subtle differences exist regarding whether he called and selected his apostles/disciples (as John P. Meier and N. T. Wright contend), or if he imposed no hierarchy and preached to all in equal terms, as suggested by John Dominic Crossan.[297]

Amy-Jill Levine states that there is, however, "a consensus of sorts" on the basic outline of Jesus' life in that most scholars agree that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist, debated Jewish authorities on the subject of God, performed some healings, gathered followers, and was crucified by Roman prefect Pontius Pilate.[37]

Donald Akenson has argued that, with very few exceptions, the historians of Yeshua have not followed sound historical practices. He has stated that there is an unhealthy reliance on consensus, for propositions which should otherwise be based on primary sources, or rigorous interpretation. He also holds that some of the criteria being used are faulty.[298]

Language, ethnicity and appearance

Jesus grew up in Galilee and much of his ministry took place there.[38] The languages spoken in Galilee and Judea during the 1st century AD/CE include the Semitic Aramaic and Hebrew languages as well as Greek, with Aramaic being the predominant language.[301][302] Most scholars agree that during the early part of 1st century AD/CE Aramaic was the mother tongue of virtually all women in Galilee and Judae.[303] Most scholars support the theory that Jesus spoke Aramaic and that he may have also spoken Hebrew and Greek.[301][302][304] James D. G. Dunn states that there is "substantial consensus" that Jesus gave most of his teachings in Aramaic.[305]

In a review of the state of modern scholarship, Amy-Jill Levine writes that the entire category of ethnicity is fraught with difficulty. Beyond recognizing that "Jesus was Jewish", rarely does the scholarship address what being "Jewish" means.[306] In the New Testament, written in Koine Greek, Jesus was referred to as an Ioudaios (i.e. "Judean") on three occasions, although he did not refer to himself as such. These three occasions are (1) by the Biblical Magi in Matthew 2 who referred to Jesus as "basileus ton ioudaion"; (2) by the Samaritan woman at the well in John 4 when Jesus was travelling out of Judea; and (3) by the Romans in all four gospels during the Passion who also used the phrase "basileus ton ioudaion".[307] According to Amy-Jill Levine, in light of the Holocaust, the Jewishness of Jesus increasingly has been highlighted.

The New Testament includes no description of the physical appearance of Jesus before his death and its narrative is generally indifferent to racial appearances and does not refer to the features of the people it discusses.[308][309][310] The synoptic gospels include the account of the Transfiguration of Jesus during which he was glorified with "his face shining as the sun" but do not provide details of his everyday appearance.[133][145] The Book of Revelation describes the features of a glorified Jesus in a vision (1:13–16), but the vision refers to Jesus in heavenly form, after his death and resurrection.[311][312]

By the 19th century theories that Jesus was of Aryan descent, in particular European, were developed and later appealed to those (such as Nazi theologians) who rejected the Jewishness of Jesus.[310][313] These theories usually also include the reasoning that Jesus was Aryan, but have not gained scholarly acceptance.[310][314] By the 20th century, theories had also been proposed that Jesus was of black African descent, some of them based on the argument that Mary his mother was a descendant of black Jews.[315]

Depictions

Despite the lack of biblical references or historical records, for two millennia a wide range of depictions of Jesus have appeared, often influenced by cultural settings, political circumstances and theological contexts.[299][300][309] As in other Christian art, the earliest depictions date to the late 2nd or early 3rd century, and surviving images are primarily found in the Catacombs of Rome.[316]

The Byzantine Iconoclasm acted as a barrier to developments in the East, but by the 9th century art was permitted again.[299] The Transfiguration of Jesus was a major theme in the East, and every Eastern Orthodox monk who had trained in icon painting had to prove his craft by painting an icon of the Transfiguration.[317] The Renaissance brought forth a number of artists who focused on the depictions of Jesus, and after Giotto, Fra Angelico and others systematically developed uncluttered images.[299] The Protestant Reformation brought a revival of aniconism in Christianity, but total prohibition was atypical, and Protestant objections to images have tended to reduce since the 16th century. Although large images are generally avoided, few Protestants now object to book illustrations depicting Jesus.[318][319] On the other hand, the use of depictions of Jesus is advocated by the leaders of denominations such as Anglicans and Catholics[320][321][322] and is a key element of the doxology of the Eastern Orthodox tradition.[323][324]

Relics associated with Jesus

A number of relics associated with Jesus have been claimed and displayed throughout the history of Christianity. Some people believe in the authenticity of some relics; others doubt the authenticity of various items. For instance, the sixteenth century Catholic theologian Erasmus wrote sarcastically about the proliferation of relics, and the number of buildings that could have been constructed from the wood claimed to be from the cross used in the Crucifixion of Christ.[325] Similarly, while experts debate whether Christ was crucified with three or with four nails, at least thirty Holy Nails continue to be venerated as relics across Europe.[326]

Some relics, such as purported remnants of the Crown of Thorns, receive only a modest number of pilgrims, others such as the Shroud of Turin (which is associated with an approved Catholic devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus) receive millions of pilgrims, which in recent years have included Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI.[327]

Religious perspectives

Apart from his own disciples and followers, the Jews of Jesus' day generally rejected him as the Messiah, as do Jews today. For their part, Christian Church Fathers, Ecumenical Councils, Reformers, and others have written extensively about Jesus over the centuries. Christian sects and schisms have often been defined or characterized by competing descriptions of Jesus. Meanwhile, Manichaeans, Gnostics, Muslims, Baha'is, and others have found prominent places for Jesus in their own religious accounts.[328]

Christian views

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Although Christian views of Jesus vary, it is possible to summarize key elements of the shared beliefs among major denominations based on their catechetical or confessional texts.[329] Christian views of Jesus are derived from various sources, but especially from the canonical Gospels, and New Testament letters, such as the Letters of Paul and Johannine writings. These documents outline the key beliefs held by Christians about Jesus, including his divinity, humanity, and earthly life. Generally speaking, adhering to the Christian faith requires a belief that Jesus is the Christ and the Son of God. In the New Testament Jesus indicates that he is the Son of God by calling God his father.[165] However, not all Christian denominations agree on all doctrines, and both major and minor differences on teachings and beliefs have persisted throughout Christianity for centuries.[330]

Christians consider Jesus the Christ and believe that through his death and resurrection, humans can be reconciled to God and thereby are offered salvation and the promise of eternal life.[331] These teachings emphasize that as the willing Lamb of God, Jesus chose to suffer in Calvary as a sign of his full obedience to the will of the Eternal Father, as an "agent and servant of God".[332] The choice Jesus made thus counter-positions him as a the new and last Adam, new man of morality and obedience, in contrast to Adam's disobedience.[333]

Most Christians believe that Jesus was both human and the Son of God. While there has been theological debate over the nature of Jesus, Trinitarian Christians generally believe that Jesus is the Logos, God incarnate, God the Son, and "true God and true man" (or both fully divine and fully human). Nontrinitarian Christians reject the notion of the Holy Trinity, do not adhere to the ecumenical councils and believe that their interpretations of the Bible take precedence over the Christian creeds.[334]

Christians not only attach theological significance to the works of Jesus, but also to his name. Devotions to the Holy Name of Jesus go back to the earliest days of Christianity.[335][336] These devotions and feasts exist both in Eastern and Western Christianity.[336]

Jewish views

Judaism rejects the idea of Jesus being God, or a person of a Trinity, or a mediator to God. Judaism also holds that Jesus is not the Messiah, arguing that he had not fulfilled the Messianic prophecies in the Tanakh nor embodied the personal qualifications of the Messiah. According to Jewish tradition, there were no prophets after Malachi, who delivered his prophesies about 420 BC/BCE.[337]

The New Testament states that Jesus was criticized by the Jewish authorities of his time. The Pharisees and scribes criticized Jesus and his disciples for not observing the Mosaic Law, not washing their hands before eating (Mark 7:1–23, Matthew 15:1–20), and gathering grain on the Sabbath (Mark 2:23–3:6). Jesus continued to be criticized by Judaism, and in the early 12th century, the Mishneh Torah (the last established consensus of the Jewish community) called Jesus a "stumbling block" who makes "the majority of the world err to serve a divinity besides God".

The Talmud includes stories which some consider accounts of Jesus in the Talmud, although there is a spectrum[338] from scholars, such as Maier (1978), who considers that only the accounts with the name Yeshu יֵשׁוּ refer to the Christian Jesus, and that these are late redactions, to scholars such as Klausner (1925), who suggested that accounts related to Jesus in the Talmud may contain traces of the historical Jesus. However the majority of contemporary historians disregard this material as providing information on the historical Jesus.[339] Many contemporary Talmud scholars view these as comments on the relationship between Judaism and Christianity or other sects, rather than comments on the historical Jesus.[340][341]

The Mishneh Torah, an authoritative work of Jewish law, provides the last established consensus view of the Jewish community, in Hilkhot Melakhim 11:10–12 that Jesus is a "stumbling block" who makes "the majority of the world err to serve a divinity besides God".[342] According to Conservative Judaism, Jews who believe Jesus is the Messiah have "crossed the line out of the Jewish community".[343] Reform Judaism, the modern progressive movement, states "For us in the Jewish community anyone who claims that Jesus is their savior is no longer a Jew and is an apostate".[344]

Islamic views

In Islam, Jesus (Arabic: عيسى ʿĪsā) is considered to be a Messenger of God and the Masih (Messiah) who was sent to guide the Children of Israel (banī isrā'īl) with a new scripture, the Injīl or Gospel.[345] The belief in Jesus (and all other messengers of God) is required in Islam, and a requirement of being a Muslim. The Qur'an mentions Jesus twenty-five times, more often, by name, than Muhammad.[346][347]

There is no mention of Joseph in the Quran, but it includes the annunciation to Mary (Arabic: Maryam) by an angel that she is to give birth to Jesus while remaining a virgin, a miraculous event which occurred by the will of God (Arabic: Allah).[348][349][350] The details of Mary's conception are not discussed during the angelic visit, but elsewhere the Quran (21:91 and 66:12) states that God breathed "His Spirit" into Mary while she was chaste.[348][349][350][351] In Islam, Jesus is called the "Spirit of God" because he was born through the action of the spirit, but that belief does not include the doctrine of his pre-existence, as it does in Christianity.[348]

Numerous other titles are given to Jesus in Islamic literature, the most common being al-Masīḥ ("the messiah"). Jesus is also, at times, called "Seal of the Israelite Prophets", because, in general Muslim belief, Jesus was the last prophet sent by God to guide the Children of Israel. Jesus is seen in Islam as a precursor to Muhammad, and is believed by Muslims to have foretold the latter's coming.[352][353] To aid in his ministry to the Jewish people, Jesus was given the ability to perform miracles, all by the permission of God rather than of his own power.

The Qur'an emphasizes that Jesus was a mortal human being who, like all other prophets, had been divinely chosen to spread God's message. Islamic texts forbid the association of partners with God (shirk), emphasizing a strict notion of monotheism (tawhīd). Like all prophets in Islam, Jesus is considered to have been a Muslim as he preached that his followers should adopt the "straight path" as commanded by God.[352][354]

Islam rejects the Christian view that Jesus was God incarnate or the Son of God, that he was ever crucified or resurrected, or that he ever atoned for the sins of mankind. The Qur'an says that Jesus himself never claimed any of these things, and it furthermore indicates that Jesus will deny having ever claimed divinity at the Last Judgment, and God will vindicate him (Quran 5:116). According to Muslim traditions, Jesus was not crucified but instead, he was raised up by God unto the heavens. This "raising" is understood to mean through bodily ascension. Muslims believe that Jesus will return to earth near the day of judgment to restore justice.[352][354]

Ahmadiyya views

The Ahmadiyya Movement believes that Jesus was a mortal man who survived his crucifixion and then died a natural death at the age 120 in Kashmir.[355][356][357][358] According to Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the 19th century founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement, Jesus did not die on the cross but fell into a comatose state and later regained consciousness after being nursed back to health by the application of Aloe and Myrrh.[355][356][357] Mainstream Muslims reject Jesus being nursed back after crucifixion and various other Ahmadiyya beliefs; and in some cases (e.g. in Pakistan) consider Ahmadiyya not Muslim.[359]

The Ahmadiyyas believe that after this apparent death and resurrection, Jesus then fled Judea and migrated eastwards to further teach the gospels and is presently buried at Roza Bal in Kashmir.[358][360] The Ahmadi reject the notion that Jesus traveled to India before his crucifixion.[361] Mirza Ghulam Ahmad declared himself to be the second coming of Jesus for the Christians and the Mujaddid (renewer of faith) for the Muslims.[356][357]

Bahá'í views

In the teachings of the Bahá'í Faith, Jesus is considered to be a Manifestation of God, a concept in the Bahá'í Faith that refers to what are commonly called prophets.[362] In Bahá'í thought, Manifestations of God are the intermediary between God and humanity, serving as messengers and reflecting God's qualities and attributes.[21] The Bahá'í concept also emphasizes the simultaneously existing qualities of humanity and divinity. In the station of divinity, they show forth the will, knowledge and attributes of God; in the station of humanity, they show the physical qualities of common man.[21] This concept is most similar to the Christian concept of incarnation.[362] In Bahá'í thought, Jesus incarnated God's attributes as they were perfectly reflected and expressed, however Bahá'í teachings reject the Christian belief that Divinity was contained with a single human body because the Bahá'í teachings state that the essence of God is transcendent above the physical reality.[362]

Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, wrote that since each Manifestation of God has the same divine attributes they can be seen as the spiritual "return" of all the previous Manifestations of God, and the appearance of each new Manifestation of God inaugurates a religion that supersedes the former ones, a sequence known as progressive revelation.[21] Through this process Bahá'í's believe God's plan unfolds gradually as mankind matures and some of the Manifestations arrive in specific fulfillment of the missions of previous ones. Bahá'í's believe that in this sense, Bahá'u'lláh is the promised return of Christ.[363]

Bahá'í teachings confirm many, but not all, aspects of the historical Jesus as portrayed in the Gospels. They believe in the Virgin Birth,[364] and the crucifixion, but see the resurrection and the miracles he performed as symbolic.[365] Bahá'í thought also accepts Jesus' Sonship.[365]

Buddhist views

Buddhist views of Jesus differ. Some Buddhist views on Jesus including Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama[366] regard Jesus as a bodhisattva who dedicated his life to the welfare of human beings. It was recorded in 101 Zen Stories that the 14th century Zen master Gasan Jōseki, on hearing some of the sayings of Jesus in the Gospels, remarked that he was "an enlightened man", and "not far from Buddhahood".[367] On the other hand, Buddhist scholars such as Masao Abe and D. T. Suzuki have stated that the centrality of the crucifixion of Jesus to the Christian view of his life is totally irreconcilable with the foundations of Buddhism.[368][369][370]

In a letter to his daughter Indira Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru wrote, "All over Central Asia, in Kashmir and Ladakh and Tibet and even farther north, there is a strong belief that Jesus or Isa traveled about there."[371] The theory that an adult Jesus traveled to India first appeared in 1887 and generated other stories, but the author later confessed to fabricating it.[372] Robert Van Voorst states that modern scholarship has "almost unanimously agreed" that claims of the travels of Jesus to Tibet, Kashmir or India contain "nothing of value".[373] Marcus Borg states that the suggestions that an adult Jesus traveled to Egypt or India and came into contact with Buddhism are "without historical foundation".[39] Although modern parallels between the teachings of Jesus and Buddha have been drawn, these comparisons emerged after missionary contacts in the 19th century, and there is no historically reliable evidence of contacts between Buddhism and Jesus during his life.[374] John Dominic Crossan states that none of the theories presented to fill the 15–18 year gap between the early life of Jesus and the start of his ministry have been supported by modern scholarship.[40]

Other views

Manichaeism (which at one point included Augustine of Hippo as a follower, who later opposed it) accepted Jesus as a prophet, along with Gautama Buddha and Zoroaster.[375][376] More recently, the New Age movement entertains a wide variety of views on Jesus. The New Age movement generally teaches that Christhood is something that all may attain. Theosophists, from whom many New Age teachings originated, refer to Jesus as the Master Jesus and believe the Christ, after various incarnations occupied the body of Jesus.[377] U.S. President Thomas Jefferson, a deist, created the Jefferson Bible, an early (but not complete) gospel harmony that included only Jesus' ethical teachings because he did not believe in Jesus' divinity or any of the other supernatural aspects of the Bible.[378][379]

Critics of Jesus included Celsus in the 2nd century and Porphyry who wrote a 15-volume attack on Christianity as a whole.[380][381] Criticism of Jesus continued into the 19th century, with Nietzsche being highly critical of Jesus. For instance, Nietzsche considered Jesus' teachings anti-natural in their treatment of topics such as sexuality.[382] In the 20th century Bertrand Russell was also critical of Jesus and in Why I Am Not a Christian stated that Jesus was "not so wise as some other people have been, and He was certainly not superlatively wise."[383]

See also

- Views on Jesus

- Related lists

Notes

- ^ Rahner states that the consensus among historians is c. 4 BC/BCE. Sanders supports c. 4 BC/BCE. Vermes supports c. 6/5 BC/BCE. Finegan supports c. 3/2 BC/BCE. Sanders refers to the general consensus, Vermes a common 'early' date, Finegan defends comprehensively the date according to early Christian traditions.

- Rahner 2004, p. 732

- Sanders 1993, pp. 10–11

- Vermes 2006, p. 22

- Finegan, Jack (1998). Handbook of Biblical Chronology, rev. ed. Hendrickson Publishers. p. 319. ISBN 978-1-56563-143-4.

If we remember the prevailing tradition represented by the majority of the early Christian scholars dated the birth of Jesus in 3/2 B.C., and if we accept the time of Herod's death as between the [lunar] eclipse of Jan 9/10 and the Passover of April 8 in the year 1 B.C., then we will probably date the nativity of Jesus in 3/2 B.C., perhaps in mid-January in 2 B.C.

- ^ Brown 1977, p. 513.

- ^ a b Köstenberger, Kellum & Quarles 2009, p. 114; Barnett 2002, pp. 19–21; Maier 1989, pp. 113–129; Sanders 1993, p. 54; Vermes 2004, p. 371.

- ^ James Dunn states that the baptism and crucifixion of Jesus "command almost universal assent" and "rank so high on the 'almost impossible to doubt or deny' scale of historical facts" that they are often the starting points for the study of the historical Jesus (Dunn 2003, p. 339).

- Bart Ehrman states that the crucifixion of Jesus on the orders of Pontius Pilate is the most certain element about him (Ehrman 1999, p. 101 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFEhrman1999 (help)).

- John Dominic Crossan states that the crucifixion of Jesus is as certain as any historical fact can be (Crossan & Watts 1999, p. 96).

- Eddy and Boyd state that it is now "firmly established" that there is non-Christian confirmation of the crucifixion of Jesus (Eddy & Boyd 2007, p. 173).

- ^ Theissen & Merz 1998: "Our conclusion must be that Jesus came from Nazareth."

- ^ Placher, William C. (1988). Readings in the History of Christian Theology. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-664-24057-7. The first sentence of the Gospel of Mark (Mk 1:1) includes Son of God and the term is also part of the Nicene Creed, the most widely used Christian creed.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Brown 1977, p. 9

- Strobel, Lee (2007). The case for the real Jesus: a journalist investigates current attacks on the identity of Christ. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-310-24061-7.

- ^ a b In a 2011 review of the state of modern scholarship, Bart Ehrman (who is a secular agnostic) wrote: "He certainly existed, as virtually every competent scholar of antiquity, Christian or non-Christian, agrees" (Ehrman 2011, p. 285).

- Richard A. Burridge states: "There are those who argue that Jesus is a figment of the Church's imagination, that there never was a Jesus at all. I have to say that I do not know any respectable critical scholar who says that any more" (Burridge & Gould 2004, p. 34).

- Robert M. Price (an atheist who denies existence) agrees that this perspective runs against the views of the majority of scholars (Price 2009, p. 61).

- James D. G. Dunn states that the theories of non-existence of Jesus are "a thoroughly dead thesis" (Sykes 2007, pp. 35–36).

- Michael Grant (a classicist) states that "In recent years, 'no serious scholar has ventured to postulate the non historicity of Jesus' or at any rate very few, and they have not succeeded in disposing of the much stronger, indeed very abundant, evidence to the contrary" (Grant 1977, p. 200).

- Robert E. Van Voorst states that biblical scholars and classical historians regard theories of non-existence of Jesus as effectively refuted (Van Voorst 2000, p. 16).

- ^ a b Evans, Craig (1993). "Life-of-Jesus Research and the Eclipse of Mythology" (PDF). Theological Studies. 54: 5.

- Talbert, Charles H. (1977). What Is a Gospel? The Genre of Canonical Gospels. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. p. 42.

- Sanders 1993, p. 3.

- Powell 1998, pp. 168–173

- ^ Brown 1994, p. 964; Carson, Moo & Morris, pp. 50–56; 1992 & Crossan, pp. xi–xiii; 1993 & Fredriksen, pp. 6–7, 105–110, 232–234, 266; 1999 & Maier, pp. 1, 99, 121, 171; 1991 & Meier, pp. 68, 146, 199, 278, 386; 1991.

- ^ Dunn 2003, p. 339; Meier 1994, pp. 12–13; Vermes 1973, p. 37; Wright 1998, pp. 32, 83, 100–102, 222; Witherington 1998, pp. 12–20.

- ^ Fredriksen, pp. 6–7, 105–110, 232–234, 266; Theissen, pp. 1–16; Dunn, pp. 47–49; Köstenberger, Kellum & Quarles, pp. 117–125; 2000 1998; 2003 2009.

- ^ For further information, see the Portraits of Jesus section.

- ^ a b Köstenberger, Kellum & Quarles 2009, p. 114; Maier 1989, pp. 113–129; Van Voorst, pp. 39–42; Niswonger 1992, pp. 121–124; 3y2000.

- ^ The methodology for constructing the historical portraits has been criticized by Akenson (Akenson 1998, pp. 539–555).

- ^ Grudem 1994, pp. 568–603.

- ^ a b Kevin Knight (ed.). "The dogma of the Trinity". Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ^ Friedmann, Robert (1953). "Antitrinitarianism". Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ^ Houlden 2006, p. 184; Düzgün 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Norman, Asher (2007). Twenty-six reasons why Jews don't believe in Jesus. Nanuet, NY: Feldheim Publishers. pp. 16–18, 89–96. ISBN 978-0-9771937-0-7.

- ^ a b c d Cole, Juan (1982). "The Concept of Manifestation in the Bahá'í Writings". Bahá'í Studies. monograph 9: 1–38.

- ^ "Saint Paul, the Apostle". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ^ Briggs, Brown Driver (1996). Hebrew and English Lexicon. Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 1-56563-206-0.

- ^ Liddell & Scott 1889, p. 824.

- ^ "The Name of Jesus Christ". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ Perkins, Larry (2010). "What's in a Name – Proper Names in Greek Exodus". Journal for the Study of Judaism. 41 (4–5): 454. doi:10.1163/157006310X503630.

- ^ Hurtado, Larry W. (2005). Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-8028-3167-5.

- Green 1997, p. 88

- Garland, David E. (1999). Reading Matthew: a literary and theological commentary. p. 23. ISBN 1-57312-274-2.

- ^ France, by R. T. (2007). The Gospel of Matthew. p. 78. ISBN 0-8028-2501-X.

- Davies & Allison 2004, p. 155

- ^ Hare, Douglas (2009). Matthew. p. 11. ISBN 0-664-23433-X.

- ^ Eddy & Boyd 2007, p. 129.

- ^ Davies & Allison 2004, p. 209.