User:Robin Mathew Rajan

| Vishnu | |

|---|---|

God of Preservation[1]

| |

| Member of Trimurti[6] | |

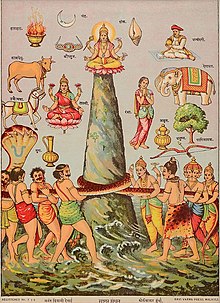

Painting depicting Vishnu, c. 1730 | |

| Other names | |

| Affiliation | |

| Abode | |

| Mantra | |

| Weapon | |

| Symbols | |

| Day | Thursday |

| Mount | |

| Festivals | |

| Genealogy | |

| Siblings | Durga as Yogamaya (ceremonial sister)[11][12] |

| Consort | Lakshmi and her forms |

| Children | |

Vishnu (/ˈvɪʃnuː/; Sanskrit: विष्णु, lit. 'All Pervasive', IAST: Viṣṇu, pronounced [ʋɪʂɳʊ]), also known as Narayana and Hari, is one of the principal deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme being within Vaishnavism, one of the major traditions within contemporary Hinduism.[13][14]

Vishnu is known as The Preserver within the Trimurti, the triple deity of supreme divinity that includes Brahma and Shiva.[15][16] In Vaishnavism, Vishnu is the supreme Lord who creates, protects, and transforms the universe. Tridevi is stated to be the energy and creative power (Shakti) of each, with Lakshmi being the equal complementary partner of Vishnu.[17] He is one of the five equivalent deities in Panchayatana puja of the Smarta tradition of Hinduism.[16]

According to Vaishnavism, the supreme being is with qualities (Saguna), and has definite form, but is limitless, transcendent and unchanging absolute Brahman, and the primal Atman (Self) of the universe.[18] There are both benevolent and fearsome depictions of Vishnu. In benevolent aspects, he is depicted as an omniscient being sleeping on the coils of the serpent Shesha (who represents time) floating in the primeval ocean of milk called Kshira Sagara with his consort, Lakshmi.[19]

Whenever the world is threatened with evil, chaos, and destructive forces, Vishnu descends in the form of an avatar (incarnation) to restore the cosmic order and protect dharma. The Dashavatara are the ten primary avatars of Vishnu. Out of these ten, Rama and Krishna are the most important.[20]

Nomenclature

[edit]Vishnu (also spelled Viṣṇu, Sanskrit: विष्णु) means 'all pervasive'[21] and, according to Medhātith (c. 1000 CE), 'one who is everything and inside everything'.[22] Vedanga scholar Yaska (4th century BCE) in the Nirukta defines Vishnu as viṣṇur viṣvater vā vyaśnoter vā ('one who enters everywhere'); also adding atha yad viṣito bhavati tad viṣnurbhavati ('that which is free from fetters and bondage is Vishnu').[23]

In the tenth part of the Padma Purana (4-15th century CE), Danta (Son of Bhīma and King of Vidarbha) lists 108 names of Vishnu (17.98–102).[24] These include the ten primary avatars (see Dashavarara, below) and descriptions of the qualities, attributes, or aspects of God.

The Garuda Purana (chapter XV)[25] and the "Anushasana Parva" of the Mahabharata both list over 1000 names for Vishnu, each name describing a quality, attribute, or aspect of God. Known as the Vishnu Sahasranama, Vishnu here is defined as 'the omnipresent'.

Other notable names in this list include :

- Hari

- Lakshmikanta

- Jagannatha

- Janardana

- Govinda

- Hrishikesha

- Padmanabha

- Mukunda

- Narayana

Iconography

[edit]Vishnu iconography shows him with dark blue, blue-grey or black coloured skin, and as a well-dressed jewelled man. He is typically shown with four arms, but two-armed representations are also found in Hindu texts on artworks.[26][27]

The historic identifiers of his icon include his image holding a conch shell (shankha named Panchajanya) between the first two fingers of one hand (left back), a war discus (chakra named Sudarshana) in another (right back). The conch shell is spiral and symbolizes all of interconnected spiraling cyclic existence, while the discus symbolizes him as that which restores dharma with war if necessary when cosmic equilibrium is overwhelmed by evil.[26] One of his arms sometimes carries a club or mace (gada named Kaumodaki) which symbolizes authority and power of knowledge.[26] In the fourth arm, he holds a lotus flower (padma) which symbolizes purity and transcendence.[26][27][28] The items he holds in various hands vary, giving rise to twenty four combinations of iconography, each combination representing a special form of Vishnu. Each of these special forms is given a special name in texts such as the Agni Purana and the Padma Purana. These texts, however, are inconsistent.[29] Rarely, Vishnu is depicted bearing the bow Sharanga or the sword Nandaka. He is depicted with the Kaustubha gem in a necklace and wearing Vaijayanti, a garland of forest flowers. The shrivatsa mark is depicted on his chest in the form of a curl of hair. He generally wears yellow garments. He wears a crown called the Kiritamukuta.[30]

Vishnu iconography shows him either in standing pose, seated in a yoga pose, or reclining.[27] A traditional depiction of Vishnu is as Narayana, showing him reclining on the coils of the serpent Shesha floating over the divine ocean Kshira Sagara, accompanied by his consort Lakshmi, as he "dreams the universe into reality."[31] His abode is described as Vaikuntha and his mount (vahana) is the bird king Garuda.[32]

Vishnu was associated with the sun because he used to be "a minor solar deity but rose in importance in the following centuries."[33]

The Trimurti

[edit]

Particularly in Vaishnavism, the Trimurti (also known as the Hindu Triad or Great Trinity)[34][35] represents the three fundamental forces (guṇas) through which the universe is created, maintained, and destroyed in cyclic succession. Each of these forces is represented by a Hindu deity:[36][37]

- Brahma: presiding deity of Rajas (passion, creation)

- Vishnu: presiding deity of Sattva (goodness, preservation)

- Shiva: presiding deity of Tamas (darkness, destruction)

The trimurti themselves are beyond three gunas and are not affected by it.[38]

In Hindu tradition, the trio is often referred to as Brahma-Vishnu-Mahesh. All have the same meaning of three in one; different forms or manifestations of One person the Supreme Being.[39]

Avatars

[edit]The concept of the avatar (or incarnation) within Hinduism is most often associated with Vishnu, the preserver or sustainer aspect of God within the Hindu Trimurti. The avatars of Vishnu descend to empower the good and to destroy evil, thereby restoring Dharma and relieving the burden of the Earth. An oft-quoted passage from the Bhagavad Gita describes the typical role of an avatar of Vishnu:

Whenever righteousness wanes and unrighteousness increases I send myself forth.

For the protection of the good and for the destruction of evil,

and for the establishment of righteousness,

I come into being age after age.— Bhagavad Gita 4.7–8

Vedic literature, in particular the Puranas (ancient; similar to encyclopedias) and Itihasa (chronicle, history, legend), narrate numerous avatars of Vishnu. The most well-known of these avatars are Krishna (most notably in the Vishnu Purana, Bhagavata Purana, and Mahabharata; the latter encompassing the Bhagavad Gita), and Rama (most notably in the Ramayana). Krishna in particular is venerated in Vaishnavism as the ultimate, primeval, transcendental source of all existence, including all the other demigods and gods, such as Vishnu.

The Mahabharata

[edit]In the Mahabharata, Vishnu (as Narayana) states to Narada that He will appear in the following ten incarnations:

Appearing in the forms of a swan [Hamsa], a tortoise [Kurma], a fish [Matsya], O foremost of regenerate ones, I shall then display myself as a boar [Varaha], then as a Man-lion (Nrisingha), then as a dwarf [Vamana], then as Rama of Bhrigu's race, then as Rama, the son of Dasaratha, then as Krishna the scion of the Sattwata race, and lastly as Kalki.

— Book 12, Santi Parva, Chapter CCCXL (340), translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, 1883–1896[40]

The Puranas

[edit]Specified avatars of Vishnu are listed against some of the Puranas in the table below. However, this is a complicated process, and the lists are unlikely to be exhaustive because:

- Not all Puranas provide lists per se (e.g. the Agni Purana dedicates entire chapters to avatars, and some of these chapters mention other avatars within them)

- A list may be given in one place but additional avatars may be mentioned elsewhere (e.g. the Bhagavata Purana lists 22 avatars in Canto 1, but mentions others elsewhere)

- Manava Purana, the only Upa Purana lists 42 avatars of Vishnu.

- A personality in one Purana may be considered an avatar in another (e.g. Narada is not specified as an avatar in the Matsya Purana but is in the Bhagavata Purana)

- Some avatars consist of two or more people considered as different aspects of a single incarnation (e.g. Nara-Narayana, Rama and his three brothers)

| Purana | Avatars | Names / Descriptions (with chapters and verses) – Dashavatara lists are in bold |

|---|---|---|

| Agni[41] | 12[a] | Matsya (2), Kurma (3), Dhanvantari (3.11), Mohini (3.12), Varaha (4), Narasimha (4.3–4), Vamana (4.5–11), Parasurama (4.12–20), Rama (5–11; one of the 'four forms' of Vishnu, including his brothers Bharata, Laksmana and Satrughna), Krishna (12), Buddha (16), Kalki (16) |

| 10[a] | Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, Vamana, Parasurama, Rama, Buddha, and Kalki (Chapter 49) | |

| Bhagavata | 22[b][42] | Kumaras, Varaha, Narada, Nara-Narayana, Kapila, Dattatreya, Yajna, Rsabha, Prthu, Matsya, Kurma, Dhanvantari, Mohini, Nrsimha, Vamana, Parashurama, Vyasadeva, Rama, Balarama and Krishna, Buddha, and Kalki (Canto 1, Chapter 3). |

| 20[b][43] | Varaha, Suyajna (Hari), Kapila, Dattātreya, Four Kumaras, Nara-Narayana, Prthu, Rsabha, Hayagriva, Matsya, Kurma, Nṛsiṁha, Vamana, Manu, Dhanvantari, Parashurama, Rama, Krishna, Buddha, and Kalki (Canto 2, Chapter 7) | |

| Brahma[44] | 15 | Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, Vamana, Hayagriva, Buddha, Rama, Kalki, Ananta, Acyuta, Jamadagnya (Parashurama), Varuna, Indra, and Yama (Volume 4: 52.68–73) |

| Garuda[45] | 20[c] | Kumara, Varaha, Narada, Nara-Narayana, Kapila, Datta (Dattatreya), Yajna, Urukrama, Prthu, Matsya, Kurma, Dhanavantari, Mohini, Narasimha, Vamana, Parasurama, Vyasadeva, Balarama, Krishna, and Kalki (Volume 1: Chapter 1) |

| 10[c] | Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Nrsimha, Vamana, Parasurama, Rama, Krishna, Buddha, and Kalki (Volume 1, Chapter 86, Verses 10–11) | |

| 10[c][46] | Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Nrsimha, Rama, Parasurama, Krishna, Balarama, Buddha, and Kalki (Volume 3, Chapter 30, Verse 37) | |

| Linga[47] | 10[d] | Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Nrsimha, Vamana, Rama, Parasurama, Krishna, Buddha, and Kalki (Part 2, Chapter 48, Verses 31–32) |

| Matsya[48] | 10[e] | 3 celestial incarnations of Dharma, Nrishimha, and Vamana; and 7 human incarnations of Dattatreya, Mandhitri, Parasurama, Rama, Vedavyasa (Vyasa), Buddha, and Kalki (Volume 1: Chapter XLVII / 47) |

| Narada[49] | 10 | Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, Trivikrama (Vamana), Parasurama, Sri-Rama, Krisna, Buddha, Kalki (Part 4, Chapter 119, Verses 14–19), and Kapila[50] |

| Padma[51][52] | 10 | Part 7: Yama (66.44–54) and Brahma (71.23–29) name 'Matsya, Kurma, and Varaha. Narasimha and Vamana, (Parasu-)rama, Rama, Krsna, Buddha, and Kalki'; Part 9: this list is repeated by Shiva (229.40–44); Kapila[50] |

| Shiva[53] | 10 | Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Nrsimha, Vamana, 'Rama trio' [Rama, Parasurama, Balarama], Krishna, Kalki (Part 4: Vayaviya Samhita: Chapter 30, Verses 56–58 and Chapter 31, verses 134–136) |

| Skanda | 14[54] | Varaha, Matsya, Kurma, Nrsimha, Vamana, Kapila, Datta, Rsabha, Bhargava Rama (Parashurama), Dasarathi Rama, Krsna, Krsna Dvaipayana (Vyasa), Buddha, and Kalki (Part 7: Vasudeva-Mamatmya: Chapter 18) |

| 10[55] | Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, Trivikrama (Vamana), Parasurama, Sri-Rama, Krisna, Buddha, and Kalki (Part 15: Reva Khanda: Chapter 151, Verses 1–7) | |

| Manavā | 42 | Adi Purusha, Kumaras, Narada, Kapila, Yajna, Dattatreya, Nara-Narayana, Vibhu, Satyasena, Hari, Vaikunta, Ajita, Shaligram, Sarvabhauma, Vrishbha, Visvaksena, Sudhama(not krishna's friend Sudama), Dharmasetu, Yogeshwara, Brihadbhanu, Hamsa, Hayagriva, Vyasa, Prithu, Vrishbha deva, Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Vamana, Parashurama, Rama, Balrama, Krishna, Buddha, Venkateswara, Dnyaneshwar, Chaitanya, Kalki |

| Varaha[56][57] | 10 | Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Nrsimha, Vamana, Parasurama, Rama, Krishna, Buddha, and Kalki (Chapter 4, Verses 2–3; Chapter 48, Verses 17–22; and Chapter 211, Verse 69) |

| ||

Dashavatara

[edit]

The Dashavatara is a list of the so-called Vibhavas, or '10 [primary] Avatars' of Vishnu. The Agni Purana, Varaha Purana, Padma Purana, Linga Purana, Narada Purana, Garuda Purana, and Skanda Purana all provide matching lists. The same Vibhavas are also found in the Garuda Purana Saroddhara, a commentary or 'extracted essence' written by Navanidhirama about the Garuda Purana (i.e. not the Purana itself, with which it seems to be confused):

The Fish, the Tortoise, the Boar, the Man-Lion, the Dwarf, Parasurama, Rama, Krisna, Buddha, and also Kalki: These ten names should always be meditated upon by the wise. Those who recite them near the diseased are called relatives.

Apparent disagreements concerning the placement of either the Buddha or Balarama in the Dashavarara seems to occur from the Dashavarara list in the Shiva Purana (the only other list with ten avatars including Balarama in the Garuda Purana substitutes Vamana, not Buddha). Regardless, both versions of the Dashavarara have a scriptural basis in the canon of authentic Vedic literature (but not from the Garuda Purana Saroddhara).

Perumal

[edit]Perumal (Tamil: பெருமாள்)—also known as Thirumal (Tamil: திருமால்), or Mayon (as described in the Tamil scriptures)— was accepted as a manifestation of Vishnu during the process of the syncretism of South Indian deities into mainstream Hinduism. Mayon is indicated to be the deity associated with the mullai tiṇai (pastoral landscape) in the Tolkappiyam.[60][61] Tamil Sangam literature (200 BCE to 500 CE) mentions Mayon or the "dark one" and as the Supreme deity who creates, sustains, and destroys the universe and was worshipped in the plains and mountains of Tamilakam.[62] The verses of Paripadal describe the glory of Perumal in the most poetic of terms. Many Poems of the Paripadal consider Perumal as the Supreme god of Tamils.[62] He is a popular Hindu deity among Tamilians in Tamil Nadu, as well among the Tamil diaspora.[63][64] Revered by the Sri Vaishnava denomination of Hinduism, Perumal is venerated in popular tradition as Venkateshwara at Tirupati,[65] and Sri Ranganathaswamy at Srirangam.[66]

Literature

[edit]

The iconography of Hindu god Vishnu has been widespread in history. | |||||||

Vedas

[edit]Vishnu is a Rigvedic deity, but not a prominent one when compared to Indra, Agni and others.[67] Just 5 out of 1028 hymns of the Rigveda are dedicated to Vishnu, although he is mentioned in other hymns.[22] Vishnu is mentioned in the Brahmana layer of text in the Vedas, thereafter his profile rises and over the history of Indian scriptures, states Jan Gonda, Vishnu becomes a divinity of the highest rank, one equivalent to the Supreme Being.[67][68]

Though a minor mention and with overlapping attributes in the Vedas, he has important characteristics in various hymns of the Rig Veda, such as 1.154.5, 1.56.3 and 10.15.3.[67] In these hymns, the Vedic scriptures assert that Vishnu resides in that highest home where departed Atman (Self) reside, an assertion that may have been the reason for his increasing emphasis and popularity in Hindu soteriology.[67][69] He is also described in the Vedic literature as the one who supports heaven and earth.[22]

तदस्य प्रियमभि पाथो अश्यां नरो यत्र देवयवो मदन्ति । उरुक्रमस्य स हि बन्धुरित्था विष्णोः पदे परमे मध्व उत्सः ॥५॥ ऋग्वेद १-१५४-५ |

5. Might I reach that dear cattle-pen of his, where men seeking the gods find elation, for exactly that is the bond to the wide-striding one: the wellspring of honey in the highest step of Viṣṇu. |

| —RV. 1.154.5[70] | —translated by Stephanie Jamison, 2020[71] |

आहं पितॄन्सुविदत्राँ अवित्सि नपातं च विक्रमणं च विष्णोः । |

3. I have found here the forefathers good to find and the grandson and the wide stride of Viṣṇu. |

| —RV 10.15.13[70] | —translated by Stephanie Jamison, 2020[71] |

In the Vedic hymns, Vishnu is invoked alongside other deities, especially Indra, whom he helps kill the symbol of evil named Vritra.[22][72] His distinguishing characteristic in the Vedas is his association with light. Two Rigvedic hymns in Mandala 7 refer to Vishnu. In section 7.99 of the Rigveda, Vishnu is addressed as the god who separates heaven and earth, a characteristic he shares with Indra. In the Vedic texts, the deity or god referred to as Vishnu is Surya or Savitr (Sun god), who also bears the name Suryanarayana. Again, this link to Surya is a characteristic Vishnu shares with fellow Vedic deities named Mitra and Agni, wherein in different hymns, they too "bring men together" and cause all living beings to rise up and impel them to go about their daily activities.[73]

In hymn 7.99 of Rigveda, Indra-Vishnu is equivalent and produce the sun, with the verses asserting that this sun is the source of all energy and light for all.[73] In other hymns of the Rigveda, Vishnu is a close friend of Indra.[74] Elsewhere in Rigveda, Atharvaveda and Upanishadic texts, Vishnu is equivalent to Prajapati, both are described as the protector and preparer of the womb, and according to Klaus Klostermaier, this may be the root behind the post-Vedic fusion of all the attributes of the Vedic Prajapati unto the avatars of Vishnu.[22]

In the Yajurveda, Taittiriya Aranyaka (10.13.1), "Narayana sukta", Narayana is mentioned as the supreme being. The first verse of "Narayana Suktam" mentions the words paramam padam, which literally mean 'highest post' and may be understood as the 'supreme abode for all Selfs'. This is also known as Param Dhama, Paramapadam, or Vaikuntha. Rigveda 1.22.20 also mentions the same paramam padam.[75]

In the Atharvaveda, the mythology of a boar who raises goddess earth from the depths of cosmic ocean appears, but without the word Vishnu or his alternate avatar names. In post-Vedic mythology, this legend becomes one of the basis of many cosmogonic myth called the Varaha legend, with Varaha as an avatar of Vishnu.[72]

Trivikrama: The Three Steps of Vishnu

[edit]Several hymns of the Rigveda repeat the mighty deed of Vishnu called the Trivikrama, which is one of the lasting mythologies in Hinduism since the Vedic times.[76] It is an inspiration for ancient artwork in numerous Hindu temples such as at the Ellora Caves, which depict the Trivikrama legend through the Vamana avatar of Vishnu.[77][78] Trivikrama refers to the celebrated three steps or "three strides" of Vishnu. Starting as a small insignificant looking being, Vishnu undertakes a herculean task of establishing his reach and form, then with his first step covers the earth, with second the ether, and the third entire heaven.[76][79]

विष्णोर्नु कं वीर्याणि प्र वोचं यः पार्थिवानि विममे रजांसि ।

यो अस्कभायदुत्तरं सधस्थं विचक्रमाणस्त्रेधोरुगायः ॥१॥…

viṣṇōrnu kaṃ vīryāṇi pra vōcaṃ yaḥ pārthivāni vimamē rajāṃsi |

yō askabhāyaduttaraṃ sadhasthaṃ vicakramāṇastrēdhōrugāyaḥ ||1||

I will now proclaim the heroic deeds of Visnu, who has measured out the terrestrial regions,

who established the upper abode having, wide-paced, strode out triply…

The Vishnu Sukta 1.154 of Rigveda says that the first and second of Vishnu's strides (those encompassing the earth and air) are visible to the mortals and the third is the realm of the immortals. The Trivikrama describing hymns integrate salvific themes, stating Vishnu to symbolize that which is freedom and life.[76] The Shatapatha Brahmana elaborates this theme of Vishnu, as his herculean effort and sacrifice to create and gain powers that help others, one who realizes and defeats the evil symbolized by the Asuras after they had usurped the three worlds, and thus Vishnu is the saviour of the mortals and the immortals (Devas).[76]

Brahmanas

[edit]To what is One

Seven germs unripened yet are heaven's prolific seed:

their functions they maintain by Vishnu's ordinance.

Endued with wisdom through intelligence and thought,

they compass us about present on every side.

What thing I truly am I know not clearly:

mysterious, fettered in my mind I wonder.

When the first-born of holy Law approached me,

then of this speech, I first obtain a portion.

(...)

They call him Indra, Mitra, Varuna, Agni,

and he is heavenly-winged Garutman.

To what is One, sages give many a title.

The Shatapatha Brahmana contains ideas which Vaishnavism tradition of Hinduism has long mapped to a pantheistic vision of Vishnu as supreme, he as the essence in every being and everything in the empirically perceived universe. In this Brahmana, states Klaus Klostermaier, Purusha Narayana (Vishnu) asserts, "all the worlds have I placed within mine own self, and my own self has I placed within all the worlds."[83] The text equates Vishnu to all knowledge there is (Vedas), calling the essence of everything as imperishable, all Vedas and principles of universe as imperishable, and that this imperishable which is Vishnu is the all.[83]

Vishnu is described to be permeating all object and life forms, states S. Giora Shoham, where he is "ever-present within all things as the intrinsic principle of all", and the eternal, transcendental self in every being.[84] The Vedic literature, including its Brahmanas layer, while praising Vishnu do not subjugate others gods and goddesses. They present an inclusive pluralistic henotheism. According to Max Muller, "Although the gods are sometimes distinctly invoked as the great and the small, the young and the old (Rig Veda 1:27:13), this is only an attempt to find the most comprehensive expression for the divine powers and nowhere is any of the gods represented as the subordinate to others. It would be easy to find, in the numerous hymns of the Veda, passages in which almost every single god is represented as supreme and absolute."[85]

Upanishads

[edit]The Vaishnava Upanishads are minor Upanishads of Hinduism, related to Vishnu theology. There are 14 Vaishnava Upanishads in the Muktika anthology of 108 Upanishads.[86] It is unclear when these texts were composed, and estimates vary from the 1st-century BCE to 17th-century CE for the texts.[87][88]

These Upanishads highlight Vishnu, Narayana, Rama or one of his avatars as the supreme metaphysical reality called Brahman in Hinduism.[89][90] They discuss a diverse range of topics, from ethics to the methods of worship.[91]

Puranas

[edit]

Vishnu is the primary focus of the Vaishnavism-focused Puranas genre of Hindu texts. Of these, according to Ludo Rocher, the most important texts are the Bhagavata Purana, Vishnu Purana, Nāradeya Purana, Garuda Purana and Vayu Purana.[92] The Purana texts include many versions of cosmologies, mythologies, encyclopedic entries about various aspects of life, and chapters that were medieval era regional Vishnu temples-related tourist guides called mahatmyas.[93]

One version of the cosmology, for example, states that Vishnu's eye is at the Southern Celestial Pole from where he watches the cosmos.[94] In another version found in section 4.80 of the Vayu Purana, he is the Hiranyagarbha, or the golden egg from which were simultaneously born all feminine and masculine beings of the universe.[95]

Vishnu Purana

[edit]The Vishnu Purana presents Vishnu as the central element of its cosmology, unlike some other Puranas where Shiva or Brahma or goddess Shakti are. The reverence and the worship of Vishnu is described in 22 chapters of the first part of Vishnu Purana, along with the profuse use of the synonymous names of Vishnu such as Hari, Janardana, Madhava, Achyuta, Hrishikesha and others.[96]

The Vishnu Purana also discusses the Hindu concept of supreme reality called Brahman in the context of the Upanishads; a discussion that the theistic Vedanta scholar Ramanuja interprets to be about the equivalence of the Brahman with Vishnu, a foundational theology in the Sri Vaishnavism tradition.[97]

Bhagavata Purana

[edit]Vishnu is equated with Brahman in the Bhagavata Purana, such as in verse 1.2.11, as "learned transcendentalists who know the Absolute Truth call this non-dual substance as Brahman, Paramatma and Bhagavan."[98]

The Bhagavata Purana has been the most popular and widely read Purana texts relating to Vishnu avatar Krishna, it has been translated and available in almost all Indian languages.[99] Like other Puranas, it discusses a wide range of topics including cosmology, genealogy, geography, mythology, legend, music, dance, yoga and culture.[100][101] As it begins, the forces of evil have won a war between the benevolent devas (deities) and evil asuras (demons) and now rule the universe. Truth re-emerges as the Vishnu avatar first makes peace with the demons, understands them and then creatively defeats them, bringing back hope, justice, freedom and good – a cyclic theme that appears in many legends.[102] The Bhagavata Purana is a revered text in Vaishnavism.[103] The Puranic legends of Vishnu have inspired plays and dramatic arts that are acted out over festivals, particularly through performance arts such as the Sattriya, Manipuri dance, Odissi, Kuchipudi, Kathakali, Kathak, Bharatanatyam, Bhagavata Mela and Mohiniyattam.[104][105][106]

Other Puranas

[edit]Some versions of the Purana texts, unlike the Vedic and Upanishadic texts, emphasize Vishnu as supreme and on whom other gods depend. Vishnu, for example, is the source of creator deity Brahma in the Vaishnavism-focussed Purana texts. Vishnu's iconography and a Hindu myth typically shows Brahma being born in a lotus emerging from his navel, who then is described as creating the world[107] or all the forms in the universe, but not the primordial universe itself.[108] In contrast, the Shiva-focussed Puranas describe Brahma and Vishnu to have been created by Ardhanarishvara, that is half Shiva and half Parvati; or alternatively, Brahma was born from Rudra, or Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma creating each other cyclically in different aeons (kalpa).[109]

In some Vaishnava Puranas, Vishnu takes the form of Rudra or commands Rudra to destroy the world, thereafter the entire universe dissolves and along with time, everything is reabsorbed back into Vishnu. The universe is then recreated from Vishnu all over again, starting a new Kalpa.[110] For this the Bhagavata Purana employs the metaphor of Vishnu as a spider and the universe as his web. Other texts offer alternate cosmogenic theories, such as one where the universe and time are absorbed into Shiva.[110][111]

Agama

[edit]The Agama scripture called the Pancharatra describes a mode of worship of Vishnu.

Sangam and Post-Sangam literature

[edit]The Sangam literature refers to an extensive regional collection in the Tamil language, mostly from the early centuries of the common era. These Tamil texts revere Vishnu and his avatars such as Krishna and Rama, as well as other pan-Indian deities such as Shiva, Muruga, Durga, Indra and others.[112] Vishnu is described in these texts as Mayon, or "one who is dark or black in color" (in north India, the equivalent word is Krishna).[112] Other terms found for Vishnu in these ancient Tamil genre of literature include mayavan, mamiyon, netiyon, mal and mayan.[113]

Krishna as Vishnu avatar is the primary subject of two post-Sangam Tamil epics Silappadikaram and Manimekalai, each of which was probably composed about the 5th century CE.[114][115] These Tamil epics share many aspects of the story found in other parts of India, such as those related to baby Krishna such as stealing butter, and teenage Krishna such as teasing girls who went to bathe in a river by hiding their clothes.[114][116]

Bhakti movement

[edit]Ideas about Vishnu in the mid 1st millennium CE were important to the Bhakti movement theology that ultimately swept India after the 12th century. The Alvars, which literally means "those immersed in God", were Tamil Vaishnava poet-saints who sang praises of Vishnu as they traveled from one place to another.[117] They established temple sites such as Srirangam, and spread ideas about Vaishnavism. Their poems, compiled as Alwar Arulicheyalgal or Divya Prabhandham, developed into an influential scripture for the Vaishnavas. The Bhagavata Purana's references to the South Indian Alvar saints, along with its emphasis on bhakti, have led many scholars to give it South Indian origins, though some scholars question whether this evidence excludes the possibility that bhakti movement had parallel developments in other parts of India.[118][119]

Vaishnava theology

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

The Bhagavata Purana summarizes the Vaishnava theology, wherein it frequently discusses the merging of the individual Self with the Absolute Brahman (Ultimate Reality, Supreme Truth), or "the return of Brahman into His own true nature", a distinctly Advaitic or non-dualistic philosophy of Shankara.[100][120][121] The concept of moksha is explained as Ekatva ('Oneness') and Sayujya ('Absorption, intimate union'), wherein one is completely lost in Brahman (Self, Supreme Being, one's true nature).[122] This, states Rukmini (1993), is proclamation of "return of the individual Self to the Absolute and its merging into the Absolute", which is unmistakably Advaitic in its trend.[122] In the same passages, the Bhagavata includes a mention of Bhagavan as the object of concentration, thereby presenting the Bhakti path from the three major paths of Hindu spirituality discussed in the Bhagavad Gita.[122][123]

Vaishnava thought holds Vishnu to exist in the alternate guise of "Isvara, the Lord of All Being" and the universe to be his breath that he will "assimilate" into him again, by breathing and causing the end of the world, which has happened before.[33] Afterwards, he will "exhale again and re-create the world."[33]

The theology in the Bhagavad Gita discusses both the sentient and the non-sentient, the Self and the matter of existence. It envisions the universe as the body of Vishnu (Krishna), state Harold Coward and Daniel Maguire. Vishnu in Gita's theology pervades all selves, all matter, and time,[124] and is associated with Brahman.[33] In Sri Vaishnavism sub-tradition, Vishnu and Sri (goddess Lakshmi) are described as inseparable, that they pervade everything together. Both together are the creators, who also pervade and transcend their creation.[124]

The Bhagavata Purana, in many passages, parallels the ideas of Nirguna Brahman and non-duality of Adi Shankara. [121] For example:

The aim of life is an inquiry into the Truth, and not the desire for enjoyment in heaven by performing religious rites,

Those who possess the knowledge of the Truth, call the knowledge of non-duality as the Truth,

It is called Brahman, the Highest Self, and Bhagavan.— Sūta, Bhagavata Purana 1.2.10–11, translated by Daniel Sheridan[125]

Scholars describe the Vaishnava theology as built on the foundation of non-dualism speculations in Upanishads, and term it as "Advaitic Theism."[121][126] The Bhagavata Purana suggests that Vishnu and the Self (Atman) in all beings is one.[120] Bryant states that the monism discussed in Bhagavata Purana is certainly built on the Vedanta foundations, but not exactly the same as the monism of Adi Shankara.[127] The Bhagavata asserts, according to Bryant, that the empirical and the spiritual universe are both metaphysical realities, and manifestations of the same Oneness, just like heat and light are "real but different" manifestations of sunlight.[127]

In the Bhakti tradition of Vaishnavism, Vishnu is attributed with numerous qualities such as omniscience, energy, strength, lordship, vigour, and splendour.[128] The Vaishnava tradition started by Madhvacharya considers Vishnu in the form of Krishna to be the supreme creator, personal God, all-pervading, all devouring, one whose knowledge and grace leads to "moksha".[129] In Madhvacharya Vaishnava theology, the supreme Vishnu and the Selfs of living beings are two different realities and nature (dualism), while in Ramanuja's Sri Vaishnavism, they are different but share the same essential nature (qualified non-dualism).[130][131][132]

Associated deities

[edit]Lakshmi

[edit]

Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of wealth, fortune and prosperity (both material and spiritual), is the wife and active energy of Vishnu.[133][134] She is also called Sri.[135][136] When Vishnu incarnated on earth as the avatars Rama and Krishna, Lakshmi incarnated as his respective consorts: Sita and Radha or Rukmini.[137][138]

Various regional beliefs consider Lakshmi to be manifested as various goddesses, who are considered Vishnu's wives. In South India, Lakshmi is worshipped in two forms – Sridevi and Bhudevi.[139] In Tirupati, Venkateshwara (identified as a form of Vishnu) is depicted with consorts, Lakshmi and Padmavathi.[140]

Garuda

[edit]Among Vishnu's primary mounts (vahana) is Garuda, the demigod eagle. Vishnu is commonly depicted as riding on his shoulders. Garuda is also considered as Vedas on which Vishnu travels. Garuda is a sacred bird in Vaishnavism. In the Garuda Purana, Garuda carries Vishnu to save the elephant Gajendra.[141][142]

Shesha

[edit]

One of the primordial beings of creation, Shesha, or Adishesha, is the king of the serpents in Hindu mythology.[143] Residing in Vaikuntha, Vishnu sleeps upon Adishesha in a perpetual slumber in his form of Narayana.[144]

Vishvaksena

[edit]Vishvaksena, also known as Senadhipathi (both meaning 'army-chief'), is the commander-in-chief of the army of Vishnu.

Harihara

[edit]

Shiva and Vishnu are both viewed as the ultimate form of god in different Hindu denominations. Harihara is a composite of half Vishnu and half Shiva, mentioned in literature such as the Vamana Purana (chapter 36),[145] and in artwork found from mid 1st millennium CE, such as in the cave 1 and cave 3 of the 6th-century Badami cave temples.[146][147] Another half Vishnu half Shiva form, which is also called Harirudra, is mentioned in Mahabharata.[148]

Beyond Hinduism

[edit]Sikhism

[edit]Vishnu is referred to as Gorakh in the scriptures of Sikhism.[149] For example, in verse 5 of Japji Sahib, the Guru ('teacher') is praised as who gives the word and shows the wisdom, and through whom the awareness of immanence is gained. Guru Nanak, according to Shackle and Mandair (2013), teaches that the Guru are "Shiva (isar), Vishnu (gorakh), Brahma (barma) and mother Parvati (parbati)," yet the one who is all and true cannot be described.[150]

The Chaubis Avtar lists the 24 avatars of Vishnu, including Krishna, Rama, and Buddha. Similarly, the Dasam Granth includes Vishnu mythology that mirrors that found in the Vaishnav tradition.[151] The latter is of particular importance to Sanatan Sikhs, including Udasis, Nirmalas, Nanakpanthis, Sahajdhari, and Keshdhari/Khalsa sects of Sikhism; however, the Khalsa Sikhs disagree with the Sanatan Sikhs.[151][152] According to Sanatan Sikh writers, the Gurus of Sikhism were avatars of Vishnu, because the Gurus brought light in the age of darkness and saved people in a time of evil Mughal-era persecution.[153][154][155]

Buddhism

[edit]Theravada Buddhism

[edit]

While some Hindus consider Buddha as an incarnation of Vishnu, Buddhists in Sri Lanka venerate Vishnu as the custodian deity of Sri Lanka and protector of Buddhism.[156]

Vishnu is also known as Upulvan or Upalavarṇā, meaning 'Blue Lotus coloured'. Some postulate that Uthpala varna was a local deity who later merged with Vishnu while another belief is that Utpalavarṇā was an early form of Vishnu before he became a supreme deity in Puranic Hinduism. According to the chronicles of Mahāvaṃsa, Cūḷavaṃsa, and folklore in Sri Lanka, Buddha himself handed over the custodianship to Vishnu. Others believe that Buddha entrusted this task to Sakra (Indra), who delegated this task of custodianship to Vishnu.[157] Many Buddhist and Hindu shrines are dedicated to Vishnu in Sri Lanka. In addition to specific Vishnu Kovils or Devalayas, all Buddhist temples necessarily house shrine rooms (Devalayas) closer to the main Buddhist shrine dedicated to Vishnu.[158]

John Holt states that Vishnu was one of the several Hindu gods and goddesses who were integrated into the Sinhala Buddhist religious culture, such as the 14th and 15th-century Lankatilaka and Gadaladeniya Buddhist temples.[159] He states that the medieval Sinhala tradition encouraged Visnu worship (puja) as a part of Theravada Buddhism just like Hindu tradition incorporated the Buddha as an avatar of Vishnu, but contemporary Theravada monks are attempting to purge the Vishnu worship practice from Buddhist temples.[160] According to Holt, the veneration of Vishnu in Sri Lanka is evidence of a remarkable ability over many centuries, to reiterate and reinvent culture as other ethnicities have been absorbed into their own. Though the Vishnu cult in Ceylon was formally endorsed by Kandyan kings in the early 1700s, Holt states that Vishnu images and shrines are among conspicuous ruins in the medieval capital Polonnaruwa.

Vishnu iconography such as statues and etchings have been found in archaeological sites of Southeast Asia, now predominantly of the Theravada Buddhist tradition. In Thailand, for example, statues of four-armed Vishnu have been found in provinces near Malaysia and dated to be from the 4th to 9th-century, and this mirror those found in ancient India.[161] Similarly, Vishnu statues have been discovered from the 6th to 8th century eastern Prachinburi Province and central Phetchabun Province of Thailand and southern Đồng Tháp Province and An Giang Province of Vietnam.[162] Krishna statues dated to the early 7th century to 9th century have been discovered in Takéo Province and other provinces of Cambodia.[163]

Mahayana Buddhism

[edit]

In Mahayana Buddhism sources, Vishnu (along with other deities) was adopted into the vast pantheon of Buddhist deities. These deities are often associated with the multiform Avalokiteśvara. Mahayana Buddhism holds that Avalokiteśvara is able to manifest in different forms according to the needs of different beings (a doctrine called "skillful means" - upaya). The Lotus Sūtra states that Avalokiteśvara can take many different forms, including Īśvara and Maheśvara - to teach the Dharma to various classes of beings.[164]

Another Mahayana sutra, the Kāraṇḍavyūhasūtra, names Vishnu (along with Shiva, Brahma and Saraswati), as emanations of Avalokiteśvara, now seen as a transcendent deity out of which the entire world emanates.[165] The Karandavyuha states that Narayana was emanated from Avalokiteshvara's heart (hṛdayānnārāyaṇaḥ), as a skillful means (upaya) for the benefit of all beings. In a similar manner, Harihara is called a bodhisattva in the popular Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī, which states: "O Effulgence, World-Transcendent, come, oh Hari, the great bodhisattva."[166]

Furthermore, the Ratnamalastotra states:

In order to teach the Vaishnavas and convert then to the Dharma, he (Vishnu) emanated from the heart of the lotus holder (Avalokitesvara). He is truly Narayana indeed, the lord of the world. Thus, you are indeed the greatest being (puṁsāṁ paramottama), without equal.[167]

These Indian Buddhist sources depict a stage of the development of Indian Mahayana in which Vishnu (along with Shiva) was being assimilated into a supreme universal form of Avalokiteśvara which is similar to the Hindu concept of Viśvarūpa.[168]

Later Vajrayana sources continue to refer to Vishnu as a form of Avalokiteśvara. For example, the Sadhanamala contains a spiritual practice in which one meditates on a form of Vishnu called Harihariharivāhana or Harihariharivāhanalokeśvara.[169] This form includes Avalokiteśvara riding on Vishnu who in turn rides on Garuda, who also rides a lion.[170] This form of Lokeśvara might be Nepalese in origin and its source myth might be found in the Buddhist Swayambhu Purana.[171]

Archeological studies have uncovered Vishnu statues on the islands of Indonesia, which was once a great stronghold of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. These statues have been dated to the 5th century and thereafter.[172] In addition to statues, inscriptions and carvings of Vishnu, such as those related to the "three steps of Vishnu" (Trivikrama) have been found in many parts of Buddhist southeast Asia.[173] In some iconography, the symbolism of Surya, Vishnu and Buddha are fused.[174]

In Japanese Buddhist pantheon, Vishnu is known as Bichū-ten (毘紐天), and he appears in Japanese texts such as the 13th century compositions of Nichiren.[175]

In science

[edit]4034 Vishnu is an asteroid discovered by Eleanor F. Helin.[176] Vishnu rocks are a type of volcanic sediment found in the Grand Canyon, Arizona, USA. Consequently, mass formations are known as Vishnu's temples.[177]

Outside the Indian subcontinent

[edit]Indonesia

[edit]In Indonesia, Vishnu or Wisnu (Indonesian spelling) is a well-known figure in the world of wayang (Indonesian puppetry), Wisnu is often referred to as the title Sanghyang Batara Wisnu. Wisnu is the god of justice or welfare, Wisnu was the fifth son of Batara Guru and Batari Uma. He is the most powerful son of all the sons of Batara Guru.

Wisnu is described as a god who has bluish black or dark blue skin, has four arms, each of which holds a weapon, namely a mace, a lotus, a trumpet and a Cakra. He can also do tiwikrama, become an infinitely large giant.

According to Javanese mythology, Wisnu first came down to the world and became a king with the title Srimaharaja Suman. The country is called Medangpura, located in the present-day Central Java region. Then changed its name to Sri Maharaja Matsyapati. In addition, according to the Javanese wayang puppet version, Batara Wisnu also incarnates Srimaharaja Kanwa, Resi Wisnungkara, Prabu Arjunasasrabahu, Sri Ramawijaya, Sri Batara Kresna, Prabu Airlangga, Prabu Jayabaya, Prabu Anglingdarma.

In Javanese mythology, Wisnu also incarnated as a matsya (fish) to kill the giant Hargragiwa who stole the Veda. Become Narasingha (human with a tiger head) to destroy King Hiranyakashipu. He once intended to become a Wimana (dwarf) to defeat Ditya Bali. Batara Wisnu also incarnated in Ramaparasu to destroy gandarwa. Incarnated as Arjunasasra or Arjunawijaya to defeat King Rahwana. The last one was for King Krishna to become the great Pandavas parampara or advisor to get rid of greed and evil committed by the Kauravas.

Sang Hyang Wisnu has a mount in the form of a giant garuda named Bhirawan. Because of his affection for the garuda he rode, Bhirawan was then adopted as son-in-law, married to one of his daughters named Dewi Kastapi.[178]

Temples

[edit]

Some of the earliest surviving grand Vishnu temples in India have been dated to the Gupta Empire period. The Sarvatobhadra temple in Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh, for example, is dated to the early 6th century and features the ten avatars of Vishnu.[180][181] Its design based on a square layout and Vishnu iconography broadly follows the 1st millennium Hindu texts on architecture and construction such as the Brihat Samhita and Visnudharmottarapurana.[182]

Archaeological evidence suggest that Vishnu temples and iconography probably were already in existence by the 1st century BCE.[183] The most significant Vishnu-related epigraphy and archaeological remains are the two 1st century BCE inscriptions in Rajasthan which refer to temples of Sankarshana and Vasudeva, the Besnagar Garuda column of 100 BCE which mentions a Bhagavata temple, another inscription in Naneghat cave in Maharashtra by a Queen Naganika that also mentions Sankarshana, Vasudeva along with other major Hindu deities and several discoveries in Mathura relating to Vishnu, all dated to about the start of the common era.[183][184][185]

The Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, is dedicated to Vishnu. The temple has attracted huge donations in gold and precious stones over its long history.[186][187][188][189]

List of temples

[edit]

- 108 Divya Desams

- 108 Abhimana Kshethram

- Padmanabhaswamy Temple

- Ranganathaswamy Temple, Srirangam

- Venkateswara Temple

- Jagannath Temple, Puri

- Badrinath Temple

- Swaminarayan temples

- Candi Wisnu, Prambanan, Java, Indonesia

- Angkor Wat, Cambodia

- Birla Mandir

- Dashavatara Temple, Deogarh

- Pundarikakshan Perumal Temple

- Kallalagar temple, Madurai

- Guruvayur Temple, Thrissur

- Ananthapura Lake Temple, Kasaragod

Gallery

[edit]-

5th-century Vishnu at Udayagiri Caves.

-

9th-century Vishnu murti at Prambanan, Java, Indonesia.

-

11th-century Vishnu sculpture the goddesses Lakshmi and Sarasvati. The edges show reliefs of Vishnu avatars Varaha, Narasimha, Balarama, Rama, and others. Also shown is Brahma. (Brooklyn Museum)[191]

-

14th-century Vishnu, Thailand.

-

A statue in Bangkok depicting Vishnu on his vahana Garuda, the eagle. One of the oldest discovered Hindu-style statues of Vishnu in Thailand is from Wat Sala Tung in Surat Thani Province and has been dated to ~400 CE.[161]

-

16th century Vishnu bronze metal sculpture from Dibrugarh, Assam

References

[edit]- ^ Encyclopedia of World Religions. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 2008. pp. 445–448. ISBN 978-1-59339-491-2.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 1134. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- ^ Soifer 1991, p. 85.

- ^ Doniger, Wendy; O'Flaherty, Wendy Doniger (1 January 1980). Karma and Rebirth in Classical Indian Traditions. University of California Press. Retrieved 26 January 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Indian Civilization and Culture. M.D. Publications Pvt. 1998. ISBN 9788175330832. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ For the Trimurti system having Brahma as the creator, Vishnu as the maintainer or preserver, and Shiva as the destroyer. see Zimmer (1972) p. 124.

- ^ a b Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. pp. 491–492. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ "Shesha, Sesa, Śeṣa, Śeṣā: 34 definitions". 23 August 2009. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Muriel Marion Underhill (1991). The Hindu Religious Year. Asian Educational Services. pp. 75–91. ISBN 978-81-206-0523-7.

- ^ Debroy, Bibek (2005). The History of Puranas. Bharatiya Kala Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-8090-062-4.

- ^ Williams, George M. (27 March 2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- ^ "Śb 10.4.12". vedabase.io/en/. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Kedar Nath Tiwari (1987). Comparative Religion. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 38. ISBN 9788120802933.

- ^ Pratapaditya Pal (1986). Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 BCE- 700 CE. University of California Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-520-05991-7.

- ^ Orlando O. Espín; James B. Nickoloff (2007). An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies. Liturgical Press. p. 539. ISBN 978-0-8146-5856-7.

- ^ a b Gavin Flood, An Introduction to Hinduism (Archived 23 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine) (1996), p. 17.

- ^ David Leeming (17 November 2005). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0190288884.

- ^ Edwin Bryant; Maria Ekstrand (23 June 2004). The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant. Columbia University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0231508438. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ Vanamali (20 March 2018). In the Lost City of Sri Krishna: The Story of Ancient Dwaraka. Simon and Schuster. p. 737. ISBN 978-1620556825.

- ^ Zimmer, Heinrich Robert (1972). Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization. Princeton University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-691-01778-5.

- ^ Vishnu Sahasranāma, translated by Swami Chinmayananda. Central Chinmaya Mission Trust. pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b c d e Klaus K. Klostermaier (2000). Hinduism: A Short History. Oneworld. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-1-85168-213-3.

- ^ Adluri, Vishwa; Joydeep Bagchee (February 2012). "From Poetic Immortality to Salvation: Ruru and Orpheus in Indic and Greek Myth". History of Religions. 51 (3): 245–246. doi:10.1086/662191. JSTOR 10.1086/662191. S2CID 56331632.

- ^ N.A. (1956). THE PADMA-PURANA PART.10. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. DELHI. pp. 3471–3473.

- ^ N.A. (1957). THE GARUDA-PURANA PART. 1. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. DELHI. pp. 44–71.

- ^ a b c d Steven Kossak; Edith Whitney Watts (2001). The Art of South and Southeast Asia: A Resource for Educators. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 30–31, 16, 25, 40–41, 74–78, 106–108. ISBN 978-0-87099-992-5.

- ^ a b c T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 73–115. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 137, 231 (Vol. 1), 624 (Vol. 2).

• James g. Lochtefeld, PhD (15 December 2001). Vol. 1. Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2017 – via Google Books.

• Lochtefeld, James G. (2002). Vol. 2. Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8239-2287-1 – via Internet Archive. - ^ P.B.B. Bidyabinod, Varieties of the Vishnu Image, Memoirs of Archaeological Survey of India, No. 2, Calcutta, pages 23–33

- ^ Blurton, T. Richard (1993). Hindu Art. Harvard University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-674-39189-5. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Fred S. Kleiner (2007). Gardner's Art through the Ages: Non-Western Perspectives. Cengage Learning. p. 22. ISBN 978-0495573678.

- ^ "Vishnu | Hindu deity | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 31 May 2024. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Stevenson 2000, p. 57.

- ^ See Apte, p. 485, for a definition of Trimurti as 'the unified form' of Brahmā, Viṣṇu and Śiva, as well as the use of phrase "Hindu triad."

- ^ See: Jansen, p. 83, for the term "Great Trinity" in relation to the Trimurti.

- ^ For quotation defining the Trimurti see: Matchett, Freda. 2003. "'The Purāṇas'." In Flood, p. 139.

- ^ For the Trimurti system having Brahma as the creator, Vishnu as the maintainer or preserver, and Shiva as the transformer or destroyer see Zimmer (1972) p. 124.

- ^ "Shiva: The Auspicious One". ISKCON News. 6 March 2008. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ "Srimad Bhagavatam Canto 1 Chapter 2 Verse 23". Vedabase.net. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 12: Santi Parva: Section CCCXL". sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ J. L. Shastri, G. P. Bhatt (1 January 1998). Agni Purana Unabridged English Motilal (vol 1.). pp. 1–38.

- ^ "CHAPTER THREE". vedabase.io. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "CHAPTER SEVEN". vedabase.io. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ N.A. (1957). BRAHMA PURANA PART. 4. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. DELHI. pp. 970.

- ^ N.A. (1957). THE GARUDA-PURANA PART. 1. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. DELHI. pp. 1–6.

- ^ N.A (1957). THE GARUDA-PURANA PART. 3. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. LTD, DELHI.

- ^ J.L.Shastri (1951). Linga Purana – English Translation – Part 2 of 2. pp. 774.

- ^ Basu, B. D. (1916). The Matsya Puranam. pp. 137–138.

- ^ N.A (1952). The Narada-Purana Part. 4. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. LTD, DELHI. pp. 1486.

- ^ a b Jacobsen, Knut A. (2008). Kapila, Founder of Sāṃkhya and Avatāra of Viṣṇu: With a Translation of Kapilāsurisaṃvāda. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 9–25. ISBN 978-81-215-1194-0.

- ^ N.A (1952). THE PADMA-PURANA PART. 7. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. LTD, DELHI.

- ^ N.A (1956). THE PADMA-PURANA PART. 9. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. LTD, DELHI.

- ^ J.L.Shastri (1950). Siva Purana – English Translation – Part 4 of 4.

- ^ N.A (1951). THE SKANDA-PURANA PART. 7. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. LTD, DELHI. pp. 285–288.

- ^ N.A. (1957). THE SKANDA-PURANA PART.15. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS PVT. DELHI.

- ^ N.A (1960). THE VARAHA PURANA PART. 1. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS, DELHI. pp. 13.

- ^ N.A (1960). THE VARAHA PURANA PART. 2. MOTILAL BANARSIDASS, DELHI. pp. 652.

- ^ Subrahmanyam, S. V. (1911). The Garuda Purana. pp. 62.

- ^ "The Garuda Purana: Chapter VIII. An Account of the Gifts for the Dying". sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Hardy, Friedhelm (1 January 2015). Viraha Bhakti: The Early History of Krsna Devotion. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 156. ISBN 978-81-208-3816-1. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ Clothey, Fred W. (20 May 2019). The Many Faces of Murukan: The History and Meaning of a South Indian God. With the Poem Prayers to Lord Murukan. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 34. ISBN 978-3-11-080410-2. Archived from the original on 19 July 2023. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ^ a b "In praise of Vishnu". The Hindu. 24 July 2014. Archived from the original on 5 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023 – via www.thehindu.com.

- ^ "Devotion to Mal (Mayon)". University of Cumbria, Division of Religion and Philosophy. Archived from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Sykes, Egerton (4 February 2014). Who's who in non-classical mythology. Kendall, Alan, 1939– (2nd ed.). London. ISBN 9781136414442. OCLC 872991268.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Krishna, Nanditha (2000). Balaji-Venkateshwara, Lord of Tirumala-Tirupati: An Introduction. Vakils, Feffer, and Simons. p. 56. ISBN 978-81-87111-46-7.

- ^ Ayyar, P. V. Jagadisa (1982). South Indian Shrines: Illustrated. Asian Educational Services. p. 453. ISBN 978-81-206-0151-2.

- ^ a b c d Jan Gonda (1969). Aspects of Early Viṣṇuism. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-81-208-1087-7.

- ^ Arthur Anthony Macdonell (1898). Vedic Mythology. Motilal Banarsidass (1996 Reprint). pp. 167–169. ISBN 978-81-208-1113-3. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ Arthur Anthony Macdonell (1898). Vedic Mythology. Motilal Banarsidass (1996 Reprint). pp. 9–11, 167–169. ISBN 978-81-208-1113-3. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ a b "ऋग्वेदः सूक्तं १.१५४ – विकिस्रोतः Archived 17 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine". sa.wikisource.org. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ a b Jamison, Stephanie (2020). The Rigveda. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0190633395.

- ^ a b Arthur Anthony Macdonell (1898). Vedic Mythology. Motilal Banarsidass (1996 Reprint). pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-81-208-1113-3. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ a b Arthur Anthony Macdonell (1898). Vedic Mythology. Motilal Banarsidass (1996 Reprint). pp. 29–32. ISBN 978-81-208-1113-3. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. (1980). Advanced History of India, Allied Publishers, New Delhi.

- ^ Renate Söhnen-Thieme; Renate Söhnen; Peter Schreiner (1989). Brahmapurāṇa. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 106. ISBN 9783447029605.

- ^ a b c d Klaus K. Klostermaier (2000). Hinduism: A Short History. Oneworld. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-1-85168-213-3.

- ^ Alice Boner (1990). Principles of Composition in Hindu Sculpture: Cave Temple Period. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 96–99. ISBN 978-81-208-0705-1.

- ^ Bettina Bäumer; Kapila Vatsyayan (1988). Kalātattvakośa: A Lexicon of Fundamental Concepts of the Indian Arts. Motilal Banarsidas. p. 251. ISBN 978-81-208-1044-0.

- ^ J. Hackin (1994). Asiatic Mythology: A Detailed Description and Explanation of the Mythologies of All the Great Nations of Asia. Asian Educational Services. pp. 130–132. ISBN 978-81-206-0920-4.

- ^ Jan Gonda (1970). Viṣṇuism and Śivaism: a comparison. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-1474280808.

- ^ Klaus K. Klostermaier (2010). A Survey of Hinduism: Third Edition. State University of New York Press. pp. 103 with footnote 10 on page 529. ISBN 978-0-7914-8011-3.

- ^ See also, Griffith's Rigveda translation: Wikisource Archived 6 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Klaus K. Klostermaier (2000). Hinduism: A Short History. Oneworld. pp. 85–87. ISBN 978-1-85168-213-3.

- ^ S. Giora Shoham (2010). To Test the Limits of Our Endurance. Cambridge Scholars. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-4438-2068-4.

- ^ Müller, Max. History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature. London: Spottiswoode and Co. p. 533

- ^ Deussen 1997, p. 556.

- ^ Mahony 1998, p. 290.

- ^ Lamb 2002, p. 191.

- ^ William K. Mahony (1998). The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination. State University of New York Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-7914-3579-3.

- ^ Moriz Winternitz; V. Srinivasa Sarma (1996). A History of Indian Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 217–224 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-208-0264-3. Archived from the original on 26 December 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ Sen 1937, p. 26.

- ^ Rocher 1986, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Glucklich 2008, p. 146, Quote: The earliest promotional works aimed at tourists from that era were called mahatmyas..

- ^ White, David Gordon (15 July 2010). Sinister Yogis. University of Chicago Press. p. 273 with footnote 47. ISBN 978-0-226-89515-4.

- ^ J.M Masson (2012). The Oceanic Feeling: The Origins of Religious Sentiment in Ancient India. Springer Science. pp. 63 with footnote 4. ISBN 978-94-009-8969-6.

- ^ Rocher 1986, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Sucharita Adluri (2015), Textual Authority in Classical Indian Thought: Ramanuja and the Visnu Purana, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415695756, pages 1–11, 18–26

- ^ Bhagavata Purana. "1.2.11". Bhaktivedanta VedaBase. Archived from the original on 23 May 2006.

vadanti tat tattva-vidas tattvam yaj jnanam advayam brahmeti paramatmeti bhagavan iti sabdyate

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 112.

- ^ a b Kumar Das 2006, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Rocher 1986, pp. 138–151.

- ^ Ravi Gupta and Kenneth Valpey (2013), The Bhagavata Purana, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149990, pages 3–19

- ^ Constance Jones and James Ryan (2007), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Infobase, ISBN 978-0816054589, page 474

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 118.

- ^ Varadpande 1987, pp. 92–97.

- ^ Graham Schweig (2007), Encyclopedia of Love in World Religions (Editor: Yudit Kornberg Greenberg), Volume 1, ISBN 978-1851099801, pages 247–249

- ^ Stevenson 2000, p. 164.

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 18.

- ^ Stella Kramrisch (1994), The Presence of Siva, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691019307, pages 205–206

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger (1988). Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism. University of Chicago Press. pp. 71–73. ISBN 978-0-226-61847-0.

- ^ Stella Kramrisch (1993). The Presence of Siva. Princeton University Press. pp. 274–276. ISBN 978-0-691-01930-7. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ a b T. Padmaja (2002). Temples of Kr̥ṣṇa in South India: History, Art, and Traditions in Tamilnāḍu. Abhinav Publications. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-7017-398-4.

- ^ T. Padmaja (2002). Temples of Kr̥ṣṇa in South India: History, Art, and Traditions in Tamilnāḍu. Abhinav Publications. p. 28. ISBN 978-81-7017-398-4.

- ^ a b T. Padmaja (2002). Temples of Kr̥ṣṇa in South India: History, Art, and Traditions in Tamilnāḍu. Abhinav Publications. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-81-7017-398-4.

- ^ John Stratton Hawley; Donna Marie Wulff (1982). The Divine Consort: Rādhā and the Goddesses of India. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 238–244. ISBN 978-0-89581-102-8.

- ^ Guy L. Beck (2012). Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity. State University of New York Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-7914-8341-1.

- ^ Olson, Carl (2007). The many colors of Hinduism: a thematic-historical introduction. Rutgers University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-8135-4068-9.

- ^ Sheridan 1986, p. [page needed].

- ^ J. A. B. van Buitenen (1996). "The Archaism of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa". In S.S Shashi (ed.). Encyclopedia Indica. pp. 28–45. ISBN 978-81-7041-859-7.

- ^ a b Brown 1983, pp. 553–557

- ^ a b c Sheridan 1986, pp. 1–2, 17–25.

- ^ a b c Rukmani 1993, pp. 217–218

- ^ Murray Milner Jr. (1994). Status and Sacredness: A General Theory of Status Relations and an Analysis of Indian Culture. Oxford University Press. pp. 191–203. ISBN 978-0-19-535912-1.

- ^ a b Harold Coward; Daniel C. Maguire (2000). Visions of a New Earth: Religious Perspectives on Population, Consumption, and Ecology. State University of New York Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-7914-4458-0.

- ^ Sheridan 1986, p. 23 with footnote 17;

Sanskrit: कामस्य नेन्द्रियप्रीतिर्लाभो जीवेत यावता | जीवस्य तत्त्वजिज्ञासा नार्थो यश्चेह कर्मभिः ||

वदन्ति तत्तत्त्वविदस्तत्त्वं यज्ज्ञानमद्वयम् | ब्रह्मेति परमात्मेति भगवानिति शब्द्यते || Source: Bhagavata Purana Archived 8 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine Archive - ^ Brown 1998, p. 17.

- ^ a b Edwin Bryant (2004), Krishna: The Beautiful Legend of God: Srimad Bhagavata Purana Book X, Penguin, ISBN 978-0140447996, pages 43–48

- ^ Tapasyananda (1991). Bhakti Schools of Vedānta. Madras: Sri Ramakrishna Math. ISBN 978-81-7120-226-3.

- ^ Deepak Sarma (2007). Edwin F. Bryant (ed.). Krishna: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press. pp. 358–360. ISBN 978-0-19-972431-4.

- ^ Sharma, Chandradhar (1994). A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 373. ISBN 978-81-208-0365-7.

- ^ Stoker, Valerie (2011). "Madhva (1238-1317)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ Stafford Betty (2010), Dvaita, Advaita, and Viśiṣṭādvaita: Contrasting Views of Mokṣa, Asian Philosophy: An International Journal of the Philosophical Traditions of the East, Volume 20, Issue 2, pages 215–224

- ^ Anand Rao (2004). Soteriologies of India. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 167. ISBN 978-3-8258-7205-2.

- ^ A Parasarthy (1983), Symbolism in Hinduism, Chinmaya Mission Publication, ISBN 978-8175971493, pages 91-92, 160-162

- ^ Monier-Williams, Monier (1899). "lakṣmī". A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 685239912.

- ^ John Muir, Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of the People of India – Their Religions and Institutions at Google Books, Volume 5, pp. 348–362 with footnotes

- ^ Monaghan, Patricia (31 December 2010). Goddesses in World Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35465-6. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ Rosen, Steven J. (1 January 2006). Essential Hinduism. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-275-99006-0.

- ^ Knapp, Stephen (1 January 2009). Spiritual India Handbook. Jaico Publishing House. p. 378. ISBN 978-81-8495-024-3. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ^ Edward Quinn (2014). Critical Companion to George Orwell. Infobase Publishing. p. 491. ISBN 9781438108735.

- ^ Gajendra Moksha (in Hindi). Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Wendy Doniger (1993). Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts. SUNY Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780791413814.

- ^ Hāṇḍā, Omacanda (2004). Naga cults and traditions in the western Himalaya. New Delhi: Indus Pub. Co. ISBN 81-7387-161-2. OCLC 55617010. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Achuthananda, Swami (27 August 2018). The Ascent of Vishnu and the Fall of Brahma. Relianz Communications Pty Ltd. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-9757883-3-2.

- ^ Gupta, anand Swarup (1968). The Vamana Purana With English Translation. p. 326.

- ^ Alice Boner (1990), Principles of Composition in Hindu Sculpture: Cave Temple Period, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120807051, pages 89–95, 115–124, 174–184

- ^ TA Gopinatha Rao (1993), Elements of Hindu iconography, Vol 2, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120808775, pages 334–335

- ^ For Harirudra citation to Mahabharata 3:39:76f see Hopkins (1969), p. 221.

- ^ Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (2011). Sikhism: An Introduction. I.B. Tauris. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-84885-321-8.

- ^ Christopher Shackle; Arvind Mandair (2013). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. Routledge. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-1-136-45101-0. Archived from the original on 8 March 2024. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ a b Harjot Oberoi (1994). The Construction of Religious Boundaries: Culture, Identity, and Diversity in the Sikh Tradition. University of Chicago Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-0-226-61593-6. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ Sanatan Singh Sabha Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Overview of World Religions, Division of Religion and Philosophy, University of Cumbria

- ^ Harjot Oberoi (1994). The Construction of Religious Boundaries: Culture, Identity, and Diversity in the Sikh Tradition. University of Chicago Press. pp. 102–105. ISBN 978-0-226-61593-6. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsburg Academic. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-4411-0231-7.

- ^ Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 48, 238. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1. Archived from the original on 17 August 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ Swarna Wickremeratne (2012). Buddha in Sri Lanka: Remembered Yesterdays. State University of New York Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0791468814.

- ^ Wilhelm Geiger. Mahawamsa: English Translation (1908).

- ^ Swarna Wickremeratne (2012). Buddha in Sri Lanka: Remembered Yesterdays. State University of New York Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0791468814.

- ^ John C Holt (2004). The Buddhist Vishnu: Religious transformation, politics and culture. Columbia University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0231133234.

- ^ John C Holt (2004). The Buddhist Vishnu: Religious transformation, politics and culture. Columbia University Press. pp. 5–7, 13–27. ISBN 978-0231133234.

- ^ a b Jacq-Hergoualc'h, Michel (2002). The Malay Peninsula: Crossroads of the Maritime Silk-Road (100 BC-1300 AD). Translated by Hobson, Victoria. BRILL Academic. p. xxiii, 116–128. ISBN 978-90-04-11973-4.

- ^ Guy 2014, pp. 131–135, 145.

- ^ Guy 2014, pp. 146–148, 154–155.

- ^ Chandra, Lokesh (1988). The Thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, p, 15. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. ISBN 81-7017-247-0.

- ^ Studholme, Alexander (2002). The Origins of Om Manipadme Hum: A Study of the Karandavyuha Sutra. State University of New York Press. p. 39-40.

- ^ Chandra, Lokesh (1988). The Thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara, pp. 130-133. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. ISBN 81-7017-247-0.

- ^ "Digital Sanskrit Buddhist Canon - Books". www.dsbcproject.org. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ Keyworth, George A. (2011). "Avalokiteśvara". In Orzech, Charles; Sørensen, Henrik; Payne, Richard (eds.). Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. Brill. pp. 525–526. ISBN 978-9004184916.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, B. (1924). The Indian Buddhist Iconography Mainly Based on The Sādhanamālā and Other Cognate Tāntric Texts of Rituals. H. Milford, Oxford University Press.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (15 June 2020). "Harihariharivahana, Harihariharivāhana, Hariharihari-vahana: 1 definition". www.wisdomlib.org. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ Sakya, M. B. (1994). The Iconography of Nepalese Buddhism Archived 7 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine, p. 111.

- ^ Guy 2014, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Guy 2014, pp. 11–12, 118–129.

- ^ Guy 2014, pp. 221–225.

- ^ Nichiren (1987). The Major Writings of Nichiren Daishonin. Nichiren Shoshu International Center. p. 1107. ISBN 978-4-88872-012-0., Alternate site: Archive Archived 17 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Vishnu & 4034 Vishnu Asteroid – Pasadena, CA – Extraterrestrial Locations on Waymarking.com". waymarking.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ Young, Matt (27 August 2012). "Vishnu Temple at the Grand Canyon". The Panda's Thumb. Archived from the original on 23 October 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ Layang kandha kelir Jawa Timuran: seri Mahabharata. Surwedi. 2007. ISBN 9789791596923. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ Tia Ghose (31 October 2012). "Mystery of Angkor Wat Temple's Huge Stones Solved". livescience.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ Alexander Lubotsky (1996), The Iconography of the Viṣṇu Temple at Deogarh and the Viṣṇudharmottarapurāṇa Archived 1 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Ars Orientalis, Vol. 26 (1996), page 65

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 7.

- ^ Alexander Lubotsky (1996), The Iconography of the Viṣṇu Temple at Deogarh and the Viṣṇudharmottarapurāṇa Archived 1 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Ars Orientalis, Vol. 26 (1996), pages 66–80

- ^ a b Bryant 2007, p. 18 with footnote 19.

- ^ Doris Srinivasan (1997). Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art. BRILL Academic. pp. 211–220, 240–259. ISBN 978-90-04-10758-8. Archived from the original on 20 January 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ [a] Doris Srinivasan (1989). Mathurā: The Cultural Heritage. Manohar. pp. 389–392. ISBN 978-81-85054-37-7.;

[b] Doris Srinivasan (1981). "Early Krishan Icons: the case at Mathura". In Joanna Gottfried Williams (ed.). Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India. BRILL Academic. pp. 127–136. ISBN 978-90-04-06498-0. Archived from the original on 16 January 2024. Retrieved 9 October 2016. - ^ "Keralas Sree Padmanabha Swamy temple may reveal more riches". India Today. 7 July 2011. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ Pomfret, James (19 August 2011). "Kerala temple treasure brings riches, challenges". Reuters. India. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ Blitzer, Jonathan (23 April 2012). "The Secret of the Temple". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ "A One Trillion Dollar Hidden Treasure Chamber is Discovered at India's Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple". Forbes.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Mittal & Thursby 2005, p. 456.

- ^ Stele with Vishnu, His Consorts, His Avatars, and Other Dieties Archived 5 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Brooklyn Museum, Item 1991.244, Gift of David Nalin

Works cited

[edit]- Brown, C. Mackenzie (1983). "The Origin and Transmission of the Two "Bhāgavata Purāṇas": A Canonical and Theological Dilemma". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 51 (4). Oxford University Press: 551–567. doi:10.1093/jaarel/li.4.551. JSTOR 1462581.

- Brown, Cheever Mackenzie (1998). The Devī Gītā: the song of the Goddess; a translation, annotation, and commentary. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3940-1. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- Bryant, Edwin F., ed. (2007). Krishna: A Sourcebook. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514891-6. [Via Google Books Archived 31 March 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- Deussen, Paul (1997). Sixty Upanishads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1467-7.

- Glucklich, Ariel (2008). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-971825-2. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Soifer, Deborah A. (1991). The Myths of Narasimha and Vamana: Two Avatars in Cosmological Perspective. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791407998.

- Guy, John (2014). Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-524-5. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Kumar Das, Sisir (2006). A history of Indian literature, 500–1399. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-2171-0. Archived from the original on 16 January 2024. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- Lamb, Ramdas (2002). Rapt in the Name: The Ramnamis, Ramnam, and Untouchable Religion in Central India. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-5386-5.

- Mahony, William K. (1998). The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3579-3.

- Rocher, Ludo (1986). The Puranas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447025225.

- Mittal, Sushil; Thursby, G. R. (2005). The Hindu World. New York: Routelge. ISBN 978-0-203-67414-7. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- Sen, S.C. (1937). The Mystical Philosophy of the Upanishads. Cosmo Publications. ISBN 978-81-307-0660-3.

- Rukmani, T. S. (1993). "Siddhis in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa and in the Yogasutras of Patanjali – a Comparison". In Wayman, Alex (ed.). Researches in Indian and Buddhist philosophy: essays in honour of Professor Alex Wayman. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 217–226. ISBN 978-81-208-0994-9. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- Sheridan, Daniel (1986). The Advaitic Theism of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa. Columbia, MO: South Asia Books. ISBN 978-81-208-0179-0. Archived from the original on 16 January 2024. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- Stevenson, Jay (2000). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Eastern Philosophy. Indianapolis: Alpha Books. ISBN 9780028638201.

- Varadpande, Manohar Laxman (1987). History of Indian theatre, Vol. 3. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-221-5. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

External links

[edit]- Robin Mathew Rajan at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- "BBC Religion & Ethics – Who is Vishnu". BBC News.

- Machek, Vaclav (1960). "Origin of the God Vishnu". Archiv Orientální: 103–126 – via ProQuest.

- Peyton, Allysa B. (2012). "Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior". Brooklyn Museum, June 24 – October 2, 2011. 19 (1): 145–150. doi:10.1086/665691. ISSN 2153-5531. JSTOR 10.1086/665691. S2CID 192592953.

| Lakshmi | |

|---|---|

Mother Goddess Goddess of Wealth, Prosperity, Fortune, Fertility, Royal Power, Abundance and Beauty[1][2] Supreme Goddess in Vaishnavism[3] | |

| Member of Tridevi and Pancha Prakriti | |

Sri Gaja Lakshmi by Raja Ravi Varma (1896) | |

| Other names |

|

| Devanagari | लक्ष्मी |

| Affiliation | |

| Abode | Vaikuntha, Manidvipa |

| Mantra |

|

| Symbols | |

| Tree | Tulasi |

| Day | Friday |

| Mount | |

| Festivals | |

| Genealogy | |

| Siblings | Alakshmi |

| Consort | Vishnu[7] |

| Children | |

Lakshmi (/ˈlʌkʃmi/;[8][nb 1] Sanskrit: लक्ष्मी, IAST: Lakṣmī, sometimes spelled Laxmi or Lakxmi, lit. 'she who leads to one's goal'), also known as Shri (Sanskrit: श्री, IAST: Śrī, lit. 'Noble'),[10] is one of the principal goddesses in Hinduism, revered as the goddess of wealth, fortune, prosperity, beauty, fertility, royal power, and abundance.[11][12] She along with Parvati and Sarasvati, form the trinity of goddesses called the Tridevi.[13][14]

Lakshmi has been a central figure in Hindu tradition since pre-Buddhist times (1500 to 500 BCE) and remains one of the most widely worshipped goddesses in the Hindu pantheon. Although she does not appear in the earliest Vedic literature, the personification of the term shri—auspiciousness, glory, and high rank, often associated with kingship—eventually led to the development of Sri-Lakshmi as a goddess in later Vedic texts, particularly the Shri Suktam.[11] Her importance grew significantly during the late epic period (around 400 CE), when she became particularly associated with the preserver god Vishnu as his consort. In this role, Lakshmi is seen as the ideal Hindu wife, exemplifying loyalty and devotion to her husband.[11] Whenever Vishnu descended on the earth as an avatar, Lakshmi accompanied him as consort, for example, as Sita and Radha or Rukmini as consorts of Vishnu's avatars Rama and Krishna, respectively.[10][15][16]

Lakshmi holds a prominent place in the Vishnu-centric sect Vaishnavism, where she is not only regarded as the consort of Vishnu, the Supreme Being, but also as his divine energy (shakti).[11] she is also the Supreme Goddess in the sect and assists Vishnu to create, protect, and transform the universe.[7][15][17][18] She is an especially prominent figure in Sri Vaishnavism tradition, in which devotion to Lakshmi is deemed to be crucial to reach Vishnu.[19] Within the goddess-oriented Shaktism, Lakshmi is venerated as the prosperity aspect of the Supreme goddess.[20][15] The eight prominent manifestations of Lakshmi, the Ashtalakshmi, symbolise the eight sources of wealth.[21]