Hyderabad State: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→See also: Link |

||

| Line 296: | Line 296: | ||

* [[Dakhini]] |

* [[Dakhini]] |

||

* [[Hyderabadi Urdu]] |

* [[Hyderabadi Urdu]] |

||

* [[Handley Page Hyderabad]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 21:48, 15 September 2016

State of Hyderabad حیدرآباد دکن/ریاست حیدرآباد హైదరాబాద్ రాష్ట్రం हैदराबाद राज्य ಹೈದರಾಬಾದ್ ಪ್ರಾಂತ್ಯ | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1724–1948 | |||||||||||

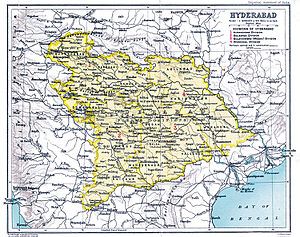

Hyderabad (dark green) and Berar Province not a part of Hyderabad State but also the Nizam's Dominion between 1853 and 1903 (light green). | |||||||||||

| Status | Independent/Mughal Successor State (1724–1798) Princely state of British India (1798–1947) Unrecognised state (1947–1948) State of India (1948–1956) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Aurangabad (1724–1763) Hyderabad (1763–1948) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Urdu (10.3%, Official) Persian (Historical) Telugu (48%) Marathi (26%) Kannada (12%)[1] | ||||||||||

| Religion | Islam (13%)(State Religion) Hinduism (81%) Christianity and others (6%)[2] | ||||||||||

| Government | Independent/Mughal Successor State (1724–1798)[3][4] Princely State (1798–1948) Province of the Dominion of India (1948–1950) State of the Republic of India (1950–1956) | ||||||||||

| Nizam | |||||||||||

• 1720–48 | Qamaruddin Khan (first) | ||||||||||

• 1911–48 | Osman Ali Khan (last) | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

• 1724–1730 | Iwaz Khan (first) | ||||||||||

• 1947–1948 | Mir Laiq Ali (last) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 1724 | ||||||||||

| 1946 | |||||||||||

| 18 September 1948 | |||||||||||

| 1 November 1956 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 215,339 km2 (83,143 sq mi) | |||||||||||

| Currency | Hyderabadi rupee | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Princely state |

|---|

| Individual residencies |

| Agencies |

|

| Lists |

Hyderābād State (), also known as Hyderabad Deccan,[6] was an Indian princely state located in the south-central region of India, and was ruled, from 1724 until 1948, by a hereditary Nizam. The capital city was Hyderabad.

The Asaf Jahi Dynasty was a dynasty of Turkic origin from the region around Samarkand in modern-day Uzbekistan, who came to India in the late 17th century, and became employees of the Mughal Empire. The region became part of the Mughal Empire in the 1680s. When the empire began to weaken in the 18th century, Asif Jah defeated a rival Mughal governor's attempt to seize control of the empire's southern provinces, declaring himself Nizam-al-Mulk of Hyderabad in 1724. The Mughal emperor, under renewed attack from the Marathas, was unable to prevent it.

Following the decline of the Mughal power, India saw the rise of Maratha Empire, Nizam himself saw many invasions by the Marathas. Some of the major battles fought between Marathas and Nizam include the Battle of Rakshasbhuvan, the Battle of Palkhed and the Battle of Kharda, through which the Nizam was compelled to pay the tributes agreed by the Mughal Empire.[7][8][9]

In 1798 Hyderabad became a princely state under the British East India Company's suzerainty. By a subsidiary alliance it had ceded to the British East India company the control of its external affairs. In 1903 the Berar region of the state was separated and merged into the Central Provinces of British India, to form the Central Provinces and Berar.

In 1947, at the time of the partition of India, the British offered the various princely states in the sub-continent the option of acceding to either India or Pakistan, or remaining as independent states.[citation needed]

Hyderabad State was the largest princely state in India. It covered 82,698 square miles (214,190 km2) of fairly homogenous territory and comprised a population of roughly 16.34 million people (as per the 1941 census), of which a majority (81%) was Hindu. Hyderabad State had its own army, airline, telecommunication system, railway network, postal system, currency, and radio broadcasting service.

The Nizam, Osman Ali Khan, decided to keep Hyderabad independent. The leaders of the new Union of India however, were wary of having an independent – and possibly hostile – state in the heart of their new country. Most of the other 565 princely states voluntarily acceded to the new India within a few months.

In September 1948, India launched Operation Polo, led by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, then Minister of Home Affairs and Deputy Prime Minister of India. The Indian Armed Forces invaded Hyderabad State and took control of the state. The Nizam subsequently signed an Instrument of Accession, joining the state to India.[10][11][12]

Seven Nizams had ruled Hyderabad State for two centuries until the Indian invasion of Hyderabad in 1948 brought about the end of the dynasty. The Asaf Jahi rulers were great patrons of literature, art, architecture, culture, jewellery, and rich food. The Nizams patronised aspects of a Persianate society from their Turco-Mongol Mughal overlords, and which became central[citation needed] to the Hyderabadi Muslim identity.[citation needed] They also introduced electricity, developed the railways and the roads, air communications, irrigation and reservoirs. The last Nizam was well known for his huge wealth and jewellery collection; he had been the richest man in the world until the end of his reign.[13] Indeed, all major public buildings in Hyderabad City were built during his reign, while the British Raj was supreme. He pushed education, science, and the establishment of Osmania University.

Early history

The Asaf Jahi was a dynasty of Turkic origin from the region around Samarkand in modern-day Uzbekistan, who came to India in the late 17th century, and became employees of the Mughal Empire. As the Turco-Mongol Mughals were great patrons of Persian culture, language, literature, the family found a ready patronage.

The Nizam of Hyderabad was earlier the Mughal Viceroy of the Deccan. However, with the decline of the Mughals the Deccan attained independence, though the first Nizam continued to owe allegiance to the Mughal Emperor. The Deccan territories were thus the last survivors of the Mughal empire, along with the Princely state of Awadh (in North India). These territories soon came to be known as the 'Nizam's Dominions', which (in the year 1760) included areas from south of Maharashtra to the southern end of Andhra Pradesh, encompassing vast territories in Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana. However, Hyder Ali administered the regions in and around Mysore and did not owe any allegiance to the Nizam.

With the Mughal empire in disarray, this was a time when the French and British were competing for supremacy in the Indian sub-continent. The French exercised considerable influence in the Deccan from their stronghold of Pondicherry. In fact, the Nizam had a French regent stationed at Hyderabad in the later years of the 18th century as an important adviser, and there remains to this day a street of Hyderabad city named Troop Bazaar, which recalls where the French originally had their military barracks. The Nizam's dominions were at their greatest territorial extent at the time of the first Nizam, Nizam-ul-mulk, Asaf Jah-I. However, after his death there arose a succession struggle, with the British and French supporting competing factions. This resulted in a period of internal instability as two Nizams (Nasir Jung and Muzaffar Jung) ruled in rapid succession, each being assassinated by a rival faction. The combined duration of their rule was just four years. The fourth Nizam, Mir Ali Salabat Jung, came to the throne on French instigation and his rule prevailed for 12 years. This period marked the height of French influence in the Nizam's dominions.

Mir Ali Salabat Jung's successor was Nizam Ali Khan Asaf Jah II, who gained the territories of Aurangabad, Bidar and Sholapur in various battles with the Marathas. Though Asaf Jah-II ruled for over 50 years, the Nizam's dominions lost considerable power and more importantly, land to both the British and the French due to infighting and debts owed to the foreign powers. He ceded the territory of Northern Circars (present day Coastal Andhra region of the state of Andhra Pradesh) to the French as a gift 'for perpetuity', while British, French and Hyder Ali annexed the Carnatic regions. The Nizam was criticised for failing to form an alliance with Hyder Ali of the Kingdom of Mysore, a move which could have countered the increasing influence of the British in the Deccan. In this time, with the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte at Waterloo, the British also replaced the French as the supreme colonial power in the Indian sub-continent. The British also fought a war with Mysore, which increased its clout in the Deccan and, by 1800, the Nizam's dominions came into a state of near-suzerainty under the British.

During the British Raj

By 1801, the Nizam's dominion assumed the shape it is now remembered for: that of a landlocked princely state with territories in central Deccan, bounded on all sides by British India, whereas 150 years earlier it had considerable coastline on the Bay of Bengal.

During the Mutiny of 1857, Salar Jung chose to side with the British, thereby earning the title of 'Faithful Ally' for Hyderabad. This action causes some regret among modern patriots, because had the Nizam's dominions sided with the rebel forces, the British would have been greatly weakened. Hyderabad was as important to the South of India as Delhi was to the North. However, this did not happen and Hyderabad was one of several independent kingdoms of India to side with the British. In 1857, when the rule of the East India Company came to an end and British India came under the direct rule of the Crown, Hyderabad continued to be one of the most important of the princely states. Twenty years later, Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India.

The senior-most (23-gun) salute state during the period of British India, Hyderabad was an 82,000 square mile (212,000 km²) region in the Deccan, ruled by the head of the Asif Jahi dynasty, who had the title of Nizam and on whom was bestowed the style of "His Exalted Highness" by the British. Development within the state of Hyderabad grew as Salar Jung and the Nizams founded schools, colleges, madrasas and a university that imparted education in Urdu. Inspired by the elite and prestigious Indian Civil Service, the Nizam founded the Hyderabad Civil Service. The pace with which the last Nizam, Osman Ali Khan, amassed wealth made him one of the world's richest men in the 1930s.[14] Carrying a gift, called Nazrana, in accordance with one's net worth while meeting the Nizam, was a de facto necessity.

Government

Wilfred Cantwell Smith states that Hyderabad was an area where the political and social structure from medieval Muslim rule had been preserved more or less intact into the modern times.[15] At the head of the social order was the Nizam, who owned 5 million acres (10% of the land area) of the state, earning him Rs. 25 million a year. Another Rs. 5 million was granted to him from the state treasury. He was reputed to be the wealthiest man in the world.[16] He was supported by an aristocracy of 1,100 feudal lords who owned a further 30% of the state's land, with some 4 million tenant farmers. The state also owned 50% or more of the capital in all the major enterprises, allowing the Nizam to earn further profits and control their affairs. All of these were almost 100% Muslim.[17]

Next in the social structure were the administrative and official class, comprising about 1,500 officials, who were also chiefly Muslim. A number of them were recruited from outside the state. The lower level governmentment employees were also predominantly Muslim. Effectively, the Muslims of the Hyderabad represented an `upper caste' of the social structure. They dominated the state's extensive Hindu population, who resented their dominance.[18]

All power was vested in the Nizam. He ruled with the help of an Executive Council or Cabinet, established in 1893, whose members he was free to appoint and dismiss. The Prime Minister was always a Muslim, often from outside the state. There was also an Assembly, whose role was mostly advisory. More than half its members were appointed by the Nizam and the rest elected from a carefully limited franchise. There were representatives of Hindus, Parsis, Christians and Depressed Classes in the Assembly. Their influence was however limited due to their small numbers.[19][20]

The state government also had a large number of outsiders (called non-mulkis) — 46,800 of them in 1933, including all the members of the Nizam's Executive Council. Hindus and Muslims united in protesting against the practice which robbed the locals of government employment. The movement however fizzled out after the Hindu members raised the issue of `responsible government', which was of no interest to the Muslim members and led to their resignation.[21]

Political movements

Upto 1920, there was no political organisation of any kind in Hyderabad. In that year, following British pressure, the Nizam issued a firman appointing a special officer to investigate constitutional reforms. It was welcomed enthusiastically by a section of the populace, who formed the Hyderabad State Reforms Association. However, the Nizam and the Special Officer ignored all their demands for consultation. Meanwhile the Nizam banned the Khilafat movement in the State as well as all political meetings and the entry of "political outsiders." Nevertheless, some political activity did take place and witnessed co-operation between Hindus and Muslims. The abolition of the Sultanate in Turkey and Gandhi's suspension of the Non-co-operation movement in British India ended this period of co-operation.[20]

An organisation called Andhra Jana Sangham (later renamed Andhra Mahasabha) was formed in November 1921, and focused on educating the masses of Telangana in political awareness. With leading members such as Madapati Hanumantha Rao, Burgula Ramakrishna Rao and M. Narsing Rao, its activities included urging merchants to resist offering freebies to government officials and encouraging labourers to resist the system of begar (free labour requested at the behest of state). Alarmed by its activities, the Nizam passed a powerful gagging order in 1929, requiring all public meetings to obtain prior permission. But the organisation persisted by mobilising on social issues such as the protection of ryots, women's rights, abolition of the devadasi system and purdah, uplifting of Dalits etc. It turned to politics again in 1937, passing a resolution calling for responsible government. Soon afterwards, it split along the moderate–extremist lines. The Andhra Mahasabha's move towards politics also inspired similar movements in Marathwada and Karnataka in 1937, giving rise to the Maharashtra Parishad and Karnataka Parishad respectively.[20]

The Arya Samaj, a pan-Indian Hindu reformist movement that engaged in a forceful religious conversion programme, established itself in the state in the 1890s, first in the Bhir and Bidar districts. By 1923, it opened a branch in the Hyderabad city. Its mass conversion programme in 1924 gave rise to tensions, and the first clashes occurred between Hindus and Muslims.[20] The Arya Samaj was allied to the Hindu Mahasabha, another pan-Indian Hindu communal organisation, which also had branches in the state. The anti-Muslim sentiments represented by the two organisations was particularly strong in Marathwada.[22]

In 1927, the first Muslim political organisation, Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (Council for the Unity of Muslims, Ittehad for short) was formed. Its political activity was meagre during the initial decade other than stating the objectives of uniting the Muslims and expressing loyalty to the ruler. However, it functioned as a 'watchdog' of Muslim interests and defended the privileged position of Muslims in the government and administration.[20]

1938 Satyagraha

1937 was a watershed year in the Indian independence movement. The Government of India Act, 1935 introduced major constitutional reforms, with a loose federal structure for India and provincial autonomy. In the provincial elections of February 1937, the Indian National Congress emerged with clear majority in most provinces of British India and formed provincial governments.

On the other hand, there was no move towards constitutional reforms in the Hyderabad state despite the initial announcement in 1920. The Andhra Mahasabha passed a resolution in favour of responsible government and the parallel organisations of Maharastrha Parishad and Karnataka Parishad were formed in their respective regions. The Nizam appointed a fresh Constitutional Reforms Committee in September 1937. However, the gagging orders of the 1920s remained curtailing the freedom of press and restrictions on public speeches and meetings. In response, a 'Hyderabad People's Convention' was created, with a working committee of 23 leading Hindus and 5 Muslims. The convention ratified a report, which was submitted to the Constitutional Reforms Committee in January 1938. However, four of the five Muslim members of the working committee refused to sign the report, reducing its potential impact.[23]

In February 1938, the Indian National Congress passed the Haripura resolution declaring that the princely states are "an integral part of India," and that it stood for "the same political, social and economic freedom in the States as in the rest of India." Encouraged by this, the standing committee of the People's Convention proposed to form a Hyderabad State Congress and an enthusiastic drive to enroll members was begun. By July 1938, the committee claimed to have enrolled 1200 primary members and declared that elections would soon be held for the office-bearers. It called upon both Hindus and Muslims of the state to "shed mutual distrust" and join the "cause of responsible government under the aegis of the Ashaf Jahi dynasty." The Nizam responded by passing a new Public Safety Act on 6 September 1938, three days before the scheduled elections, and issued an order that the Hyderabad State Congress would be deemed unlawful.[23]

Negotiations with the Nizam's government to lift the ban ended in failure. The Hyderabad issue was widely discussed in the newspapers in British India. P. M. Bapat, a leader of the Indian National Congress from Pune, declared that he would launch a satyagraha (civil disobedience movement) in Hyderbad starting 1 November. The Arya Samaj and Hindu Mahasabha also planned to launch satyagrahas on the matter of Hindu civil rights. The Hindu communal pot had been boiling since early 1938 when an Arya Samaj member in Osmanabad district was said to have been murdered for refusing to convert to Islam. In April, there was communal riot in Hyderabad between Hindus and Muslims, which raised the allegation of 'oppression of Hindus' in the press in British India. The Arya Samaj leaders hoped to capitalise on these tensions. Perhaps in a bid not to be outdone, the activists of the Hyderabad State Congress formed a 'Committee of Action' and initiated a satyagraha on 24 October 1938. The members of the organisation were fielded, who openly declared they belong to the Hyderabad State Congress and courted arrest. The Arya Samaj-Hindu Mahasabha combine also launched their own satyagraha on the same day.[23]

The Indian National Congress refused to back the satyagraha of the State Congress. The Haripura resolution had in fact been a compromise between the moderates and the radicals. Gandhi had been wary of direct involvement in the states lest the agitations degenerate into violence. The Congress high command was also keen on a firmer collaboration between Hindus and Muslims, which the State Congress lacked. Padmaja Naidu wrote a lengthy report to Gandhi where she castigated the State Congress for lacking unity and cohesion and for being 'communal in [her] sense of the word'. On 24 December, the State Congress suspended the agitation after 300 activists had courted arrest. These activists remained in jail till the invasion by India in 1948.[23][24]

The Arya Samaj-Hindu Mahasabha combine continued their agitation and intensified it in March 1949. However, the response from the state's Hindus was lacklustre. Of the 8,000 activists that courted arrest by June, about 20% were estimated to be state's residents; the rest were mobilised from British India. The surrounding British Indian provinces of Bombay and Central Provinces and, to limited extent, Madras, all governed by Indian National Congress, facilitated the mobilisation, with town such as Ahmednagar, Sholapur, Vijayawada, Pusad and Manmad used as staging posts. Increasingly strident anti-Hyderabad propaganda continued in British India. By July–August, the tensions had eased. The Hindu Mahasabha dispatched the Shankaracharya of Jyotirmath on a peace mission, who testified that there was no religious persecution of Hindus in the state. The Nizam government set up a Religious Affairs Committee and announced constitutional reforms by 20 July. Subsequently, the Hindu Mahasabha suspended its campaign on 30 July and the Arya Samaj on 8 August. All the imprisoned activists of the two organisations were released.[23]

Telangana movement

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2016) |

Industries in Hyderabad under the Nizams

Various major industries emerged in various parts of the State of Hyderabad before its incorporation into the Union of India, especially during the first half of the twentieth century. Hyderabad city had a separate powerplant for electricity. However, the Nizams focused industrial development on the region of Sanathnagar, housing a number of industries there with transportation facilities by both road and rail.[25]

| Company | Year |

|---|---|

| Karkhana Zinda Tilismat | 1920 |

| Singareni Collieries | 1921 |

| Vazir Sultan Tobacco Company, Charminar cigarette factory | 1930 |

| Azam Jahi Mills Warangal | 1934 |

| Nizam Sugar Factory | 1937 |

| Allwyn Metal Works | 1942 |

| Praga Tools | 1943 |

| Deccan Airways Limited | 1945 |

| Hyderabad Asbestos | 1946 |

| Sirsilk | 1946 |

Banking

The Imperial Bank of India opened a branch in Hyderabad in 1868, and a second branch in Secunderabad in 1906. Central Bank of India opened its branch in Hyderabad in 1918 and a second branch in Secunderabad in 1925.

Until 1948, Gulbarga district, now part of Karnataka state, was part of Hyderabad state. Saraswati Bank, established in Gulbarga in 1918, had a branch in Hyderabad. The Gulbarga Banking Company, established in 1930, however, did not.

In 1935 Raja Pannalal Pitti founded the Mercantile Bank of Hyderabad.

In 1942 the Nizam established Hyderabad State Bank to conduct treasury operations for the state government, and other banking. In 1947 there was a proposal that Hyderabad State Bank would be allowed to establish a branch in Karachi, and that as a quid-pro-quo Habib Bank would be allowed to establish a branch in Hyderabad. Partition and Operation Polo, the Indian invasion of Hyderabad that annexed Hyderabad to India, put an end to this idea. Then in 1952–53, Hyderabad State Bank acquired Mercantile Bank. Next, in 1956 State Bank of India took over Hyderabad State Bank, which in 1959 became State Bank of Hyderabad, a subsidiary bank of State Bank of India.

After Indian Independence (1947–48)

In 1947 India gained independence and Pakistan came into existence; the British left the local rulers of the princely states the choice of whether to join one or the other, or to remain independent. On 11 June 1947, the Nizam issued a declaration to the effect that he had decided not to participate in the Constituent Assembly of either Pakistan or India. India insisted that the great majority of residents wanted to join India.[26]

On 9 July 1947, in a letter to the Crown Representative, the Nizam requested that Hyderabad be accorded dominion status. This was, however, problematical. Given the Nizam's determination not to join India, this would leave Hyderabad as an independent country entirely surrounded by the new Union of India. The Nizam was a Muslim but the Hindus outnumbered the Muslims by about eight to one in the State.

Keeping in mind Hyderabad's geographical position and the existence of a Hindu majority in his state, and countering India's insistence on accession, pending a settlement the Nizam signed a Stand-still Agreement with India on 29 November 1947. The Agreement was to remain in force for a period of one year. The Agreement provided that disputes arising out of it could be referred to the arbitration of two arbitrators, one appointed by each of the parties, and an umpire appointed by those arbitrators.

The Nizam was in a weak position as his army numbered only 24,000 men, of whom only some 6,000 were fully trained and equipped.[27] The Indian government refused to accept Hyderabad's independence and prepared to carry out a so-called "Hyderabad Police Action" against the Nizam.

On 21 August 1948, the Secretary-General of the Hyderabad Department of External Affairs requested the President of the United Nations's Security Council, under Article 35(2) of the United Nations Charter, to consider the "grave dispute, which, unless settled in accordance with international law and justice, is likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and security."[28]

On 4 September the Prime Minister of Hyderabad Mir Laiq Ali announced to the Hyderabad Assembly that a delegation was about to leave for Lake Success, headed by Moin Nawaz Jung.[29] The Nizam also appealed, without success, to the British Labour Government and to the King for assistance, to fulfil their obligations and promises to Hyderabad by "immediate intervention". Hyderabad only had the support of Winston Churchill and the British Conservatives.[30]

At 4 a.m. on 13 September 1948, India's Hyderabad Campaign, code-named "Operation Polo" by the Indian Army, began. Indian troops invaded Hyderabad from all points of the compass. On 13 September 1948, the Secretary-General of the Hyderabad Department of External Affairs in a cablegram informed the United Nations Security Council that Hyderabad was being invaded by Indian forces and that hostilities had broken out. The Security Council took notice of it on 16 September in Paris. The representative of Hyderabad called for immediate action by the Security Council under chapter VII of the United Nations Charter. The Hyderabad representative responded to India's excuse for the intervention by pointing out that the Stand-still Agreement between the two countries had expressly provided that nothing in it should give India the right to send in troops to assist in the maintenance of internal order.[31]

At 5 p.m. on 17 September the Nizam surrendered. India then incorporated the state of Hyderabad into the Union of India and ended the rule of the Nizams.[32] The annexation of Hyderabad was generally welcomed by many Hindus in the state, but Muslims emphasised the unlawfulness of the invasion. Some Muslims migrated to Pakistan, mainly to Karachi, which has a sizeable Hyderabadi muhajir community.

On 6 October 1948, Pakistan's Foreign Minister Sir Muhammad Zafarullah Khan, requested the President of the United Nations' Security Council that Pakistan be permitted to participate in the discussion of the Hyderabad question in accordance with Article 31 of the United Nations' Charter.[33]

Hyderabad became a state of India.

Communal violence

Prior to the operation

In the 1936–37 Indian elections, the Muslim League under Muhammad Ali Jinnah had sought to harness Muslim aspirations and had won the adherence of MIM leader Nawab Bahadur Yar Jung, who campaigned for an Islamic State centred on the Nizam as the Sultan dismissing all claims for democracy. The Arya Samaj, a Hindu revivalist movement, had been demanding greater access to power for the Hindu majority since the late 1930s and was curbed by the Nizam in 1938. The Hyderabad State Congress joined forces with the Arya Samaj as well as the Hindu Mahasabha in the State.[34]

Noorani regards the MIM under Nawab Bahadur Yar Jung as explicitly committed to safeguarding the rights of religious and linguistic minorities. However, this changed with the ascent of Qasim Razvi after the Nawab died in 1944.[35]

Even as India and Hyderabad negotiated, most of the sub-continent had been thrown into chaos as a result of communal Hindu-Muslim riots pending the imminent partition of India. Fearing a Hindu civil uprising in his kingdom, the Nizam allowed Razvi to set up a voluntary militia of Muslims called the 'Razakars'. The Razakars – who numbered up to 200,000 at the height of the conflict – swore to uphold Islamic domination in Hyderabad and the Deccan plateau[36]: 8 in the face of growing public opinion amongst the majority Hindu population favouring the accession of Hyderabad into the Indian Union.

According to an account by Mohammed Hyder, a civil servant in Osmanabad district, a variety of armed militant groups, including Razakars and Deendars and ethnic militias of Pathans and Arabs claimed to be defending the Islamic faith and made claims on the land. "From the beginning of 1948, the Razakars had extended their activities from Hyderabad city into the towns and rural areas, murdering Hindus, abducting women, pillaging houses and fields, and looting non-Muslim property in a widespread reign of terror."[37][38] "Some women became victims of rape and kidnapping by Razakars. Thousands went to jail and braved the cruelties perpetuated by the oppressive administration. Due to the activities of the Razakars, thousands of Hindus had to flee from the state and take shelter in various camps".[38] Precise numbers are not known, but 40,000 refugees were received by the Central Provinces.[36]: 8 This led to terrorising of the Hindu community, some of whom went across the border into independent India and organised raids into Nizam's territory, which further escalated the violence. Many of these raiders were controlled by the Congress leadership in India and had links with extremist religious elements in the Hindutva fold.[39] In all, more than 150 villages (of which 70 were in Indian territory outside Hyderabad State) were pushed into violence.

Hyder mediated some efforts to minimise the influence of the Razakars.[citation needed] Razvi, while generally receptive, vetoed the option of disarming them, saying that with the Hyderabad state army ineffective, the Razakars were the only means of self-defence available. By the end of August 1948, a full-blown invasion by India was imminent.[40]

Hyderabadi military preparations

The Nizam was in a weak position as his army numbered only 24,000 men, of whom only some 6,000 were fully trained and equipped.[41] These included Arabs, Rohillas, North Indian Muslims and Pathans. The State Army consisted of three armoured regiments, a horse cavalry regiment, 11 infantry battalions and artillery. These were supplemented by irregular units with horse cavalry, four infantry battalions (termed as the Saraf-e-khas, paigah, Arab and Refugee) and a garrison battalion.[citation needed] This army was commanded by Major General El Edroos, an Arab.[42] 55 per cent of the Hyderabadi army was composed of Muslims, with 1,268 Muslims in a total of 1,765 officers as of 1941.[43][44]

In addition to these, there were about 200,000 irregular militia called the Razakars under the command of a civilian leader Kasim Razvi. A quarter of these were armed with modern small firearms, while the rest were predominantly armed with muzzle-loaders and swords.[42]

Skirmish at Kodad

On 6 September an Indian police post near Chillakallu village came under heavy fire from Razakar units. The Indian Army command sent a squadron of The Poona Horse led by Abhey Singh and a company of 2/5 Gurkha Rifles to investigate who was also fired upon by the Razakars. The tanks of the Poona Horse then chased the Razakars to Kodad, in Hyderabad territory. Here they were opposed by the armoured cars of 1 Hyderabad Lancers. In a brief action, the Poona Horse destroyed one armoured car and forced the surrender of the state garrison at Kodad.

Indian military preparations

On receiving directions from the government to seize and annex Hyderabad,[45] the Indian army came up with the Goddard Plan (laid out by Lt. Gen. E. N. Goddard, the Commander-in-Chief of the Southern Command). The plan envisaged two main thrusts – from Vijayawada in the East and Solapur in the West – while smaller units pinned down the Hyderabadi army along the border. Overall command was placed in the hands of Lt. Gen. Rajendrasinghji, DSO.

The attack from Solapur was led by Major General Jayanto Nath Chaudhuri and was composed of four task forces:

- Strike Force comprising a mix of fast-moving infantry, cavalry and light artillery,

- Smash Force consisting of predominantly armoured units and artillery,

- Kill Force composed of infantry and engineering units,

- Vir Force which comprised infantry, anti-tank and engineering units.

The attack from Vijayawada was led by Major General Ajit Rudra and comprised the 2/5 Gurkha Rifles, one squadron of the 17th (Poona) Horse, and a troop from the 19th Field Battery along with engineering and ancillary units. In addition, four infantry battalions were to neutralise and protect lines of communication. Two squadrons of Hawker Tempest aircraft were prepared for air support from the Pune base.

Nehru, in a letter to V. K. Krishna Menon dated to 29 August 1948, wrote that "I am convinced that it is impossible to arrive at any solution of the Hyderabad problem by settlement or peaceful negotiation. Military action becomes essential, we call it as you have called it Police Action."[46][47] It was also believed that there could be a possible military response by Pakistan.[48][36] The Time magazine pointed out that if India invaded Hyderabad, Razakars would massacre Hindus, which would lead to retaliatory massacres of Muslims across India.[49]

During and after the operation

There were reports of looting, mass murder and rape of Muslims in reprisals by Hyderabadi Hindus.[50][38] Jawaharlal Nehru appointed a mixed-faith committee led by Pandit Sunder Lal to investigate the situation. The findings of the report (Pandit Sunderlal Committee Report) were not made public until 2013 when it was accessed from the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library in New Delhi.[50][51]

The Committee concluded that while Muslim villagers were disarmed by the Indian Army, Hindus were often left with their weapons.[50] The violence was carried out by Hindu residents, with the army sometimes indifferent, and sometimes participating in the atrocities.[36]: 11 The Committee stated that large-scale violence against Muslims occurred in Marathwada and Telangana areas. It also concluded: "At several places, members of the armed forces brought out Muslim adult males from villages and towns and massacred them in cold blood."[50] The Committee generally credited the military officers with good conduct but stated that soldiers acted out of bigotry.[36]: 11 The official "very conservative estimate" was that 27,000 to 40,000 died "during and after the police action."[50] Other scholars have put the figure at 200,000, or even higher.[52] Among Muslims some estimates were even higher and Smith says that the military government's private low estimates [of Muslim casualties] were at least ten times the number of murders with which the Razakars were officially accused.[53]

Patel reacted angrily to the report and disowned its conclusions. He stated that the terms of reference were flawed because they only covered the part during and after the operation. He also cast aspersions on the motives and standing of the committee. These objections are regarded by Noorani as disingenuous because the commission was an official one, and it was critical of the Razakars as well.[52][54]

According to Mohammed Hyder, the tragic consequences of the Indian operation were largely preventable. He faulted the Indian army for neither restoring local administration nor setting up their military administration. As a result, the anarchy led to several thousand "thugs", from the camps set up across the border, filling the vacuum. He stated "Thousands of families were broken up, children separated from their parents and wives, from their husbands. Women and girls were hunted down and raped."[55]

Hyderabad after integration

Detentions and release of people involved

The Indian military detained thousands of people during the operation, including Razakars, Hindu militants, and communists. This was largely done based on local informants, who used this opportunity to settle scores. The estimated number of people detained was close to 18,000, which resulted in overcrowded jails and a paralysed criminal system.[36]: 11–12

The Indian government set up Special Tribunals to prosecute these. These strongly resembled the colonial governments earlier, and there were many legal irregularities, including denial or inability to access lawyers and delayed trials – about which the Red Cross was pressuring Nehru.[36]: 13–14

The viewpoint of the government was: "In political physics, Razakar action and Hindu reaction have been almost equal and opposite." A quiet decision was taken to release all Hindus and for a review of all Muslim cases, aiming to let many of them out. Regarding atrocities by Muslims, Nehru considered the actions during the operation as "madness" seizing "decent people", analogous to experience elsewhere during the partition of India. Nehru was also concerned that disenfranchised Muslims would join the communists.[36]: 15–16

The government was under pressure to not prosecute participants in communal violence, which often made communal relations worse. Patel had also died in 1950. Thus, by 1953 the Indian government released all but a few persons.[36]: 16

Overhaul of bureaucracy

Junior officers from neighbouring Bombay, CP and Madras regions were appointed to replace the vacancies. They were unable to speak the language and were unfamiliar with local conditions. Nehru objected to this "communal chauvinism" and called them "incompetent outsiders", and tried to impose Hyderabadi residency requirements: however, this was circumvented by using forged documents.[36]: 17–18

See also

References

- ^ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 20.

- ^ Smith 1950, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, Chapter 1.

- ^ Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (2004), Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy (Second ed.), Routledge, p. 42, ISBN 978-0-415-30787-1

- ^ Ram Narayan Kuma 1997.

- ^ Ali, Cherágh (1 January 1886). Hyderabad (Deccan) Under Sir Salar Jung. Printed at the Education Society's Press.

- ^ Tony Jaques (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33538-9.

- ^ Pradeep Barua (2005). The State at War in South Asia. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1344-1.

- ^ Faruqui 2013, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Rai, Raghunath, History — Class XII, FK Publications, p. 244, ISBN 978-81-87139-69-0

- ^ Menon 1956, p. 267.

- ^ Chandra, Bipan (2008), India Since Independence, Penguin Books Limited, ISBN 978-81-8475-053-9,

Finally, on 13 September 1948, the Indian army moved into Hyderabad. The Nizam surrendered after three days and acceded to the Indian Union in November. The Government of India decided to be generous and not punish the Nizam. He was retained as formal ruler of the state or its Rajpramukh, was given a privy purse of Rs 5 million, and permitted to keep most of his immense wealth.

- ^ "Top ten richest men of all time". inStash. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ Time dated 22 February 1937, cover story

- ^ Smith 1950, p. 28.

- ^ Guha 2008, p. 51.

- ^ Smith 1950, p. 29.

- ^ Smith 1950, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Smith 1950, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b c d e Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, Chapter 2.

- ^ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Smith 1950, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, Chapter 3.

- ^ Smith 1950, pp. 32, 42.

- ^ "Kaleidoscopic view of Deccan". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 25 August 2009.

- ^ Purushotham, Sunil (2015). "Internal Violence: The "Police Action" in Hyderabad". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 57 (2): 435–466. doi:10.1017/s0010417515000092.

- ^ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 229.

- ^ "The Hyderabad Question" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 230.

- ^ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 231.

- ^ United Nations Document S/986

- ^ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 232.

- ^ United Nations Security Council Document S/1031

- ^ Noorani 2014, pp. 51–61.

- ^ Muralidharan 2014, pp. 128–129.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sherman, Taylor C. (2007). "The integration of the princely state of Hyderabad and the making of the postcolonial state in India, 1948 – 56" (PDF). Indian Economic & Social History Review. 44 (4): 489–516. doi:10.1177/001946460704400404. S2CID 145000228.

- ^ By Frank Moraes, Jawaharlal Nehru, Mumbai: Jaico.2007, p.394

- ^ a b c Kate, P. V., Marathwada Under the Nizams, 1724–1948, Delhi: Mittal Publications, 1987, p.84

- ^ Muralidharan 2014, p. 132.

- ^ Muralidharan 2014, p. 134.

- ^ Benichou, From Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 229.

- ^ a b "Bharat Rakshak-MONITOR". Bharat-rakshak.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2005. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

mohanGuruswamywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ [1] Archived 26 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Osmania Journal of Historical Research. Department of History, Osmania University. 2006. p. 82.

- ^ Hangloo, Rattan Lal; Murali, A. (2007). New Themes in Indian History: Art, Politics, Gender, Environment, and Culture. Black & White. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-81-89320-15-7.

- ^ Joseph, T.U. (2006). Accession of Hyderabad: The Inside Story. Sundeep Prakashan. p. 176. ISBN 978-81-7574-171-3.

- ^ Nayar, K. (2012). Beyond The Lines: An Autobiography. Roli Books. p. 146. ISBN 978-81-7436-821-8.

- ^ Lubar, Robert (30 August 1948). "Hyderabad: The Holdout". Time. p. 26. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

If the Indian army invaded Hyderabad, Razvi's Razakars would kill Hyderabad Hindus. Throughout India, Hindus would retaliate against Muslims.

- ^ a b c d e Thomson, Mike (24 September 2013). "Hyderabad 1948: India's hidden massacre". BBC. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Lessons to learn from Hyderabad's past", The Times of India, 16 December 2013, ProQuest 1468149022

- ^ a b Noorani, A.G. (3–16 March 2001), "Of a massacre untold", Frontline, 18 (5), retrieved 8 September 2014,

The lowest estimates, even those offered privately by apologists of the military government, came to at least ten times the number of murders with which previously the Razakars were officially accused...

- ^ Benichou, From Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 238.

- ^ Muralidharan 2014, p. 136.

- ^ Muralidharan 2014, p. 135.

Bibliography

- Benichou, Lucien D. (2000), From Autocracy to Integration: Political Developments in Hyderabad State, 1938–1948, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-81-250-1847-6

- Chandra, Bipan; Mukherjee, Aditya; Mukherjee, Mridula (2008) [first published 1999], India Since Independence, Penguin Books India, ISBN 978-0-14-310409-4

- Hyder, Mohammed (2012), October Coup, A Memoir of the Struggle for Hyderabad, Roli Books, ISBN 978-8174368508

- Hodson, H. V. (1969), The Great Divide: Britain, India, Pakistan, London: Hutchinson, ISBN 978-0090971503

- Menon, V. P. (1956), The Story of Integration of the Indian States (PDF), Orient Longman

- Muralidharan, Sukumar (2014). "Alternate Histories: Hyderabad 1948 Compels a Fresh Evaluation of the Theology of India's Independence and Partition". History and Sociology of South Asia. 8 (2): 119–138. doi:10.1177/2230807514524091. S2CID 153722788.

- Noorani, A. G. (2014), The Destruction of Hyderabad, Hurst & Co, ISBN 978-1-84904-439-4

- Raghavan, Srinath (2010), War and Peace in Modern India, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-137-00737-7

- Smith, Wilfred Cantwell (January 1950), "Hyderabad: Muslim Tragedy", Middle East Journal, 4 (1): 27–51, JSTOR 4322137

- Zubrzycki, John (2006), The Last Nizam: An Indian Prince in the Australian Outback, Australia: Pan Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-330-42321-2

External links

- Police Action in Hyderabad, 1948 September 13–18 : Should We Celebrate It?

- From the Sundarlal Report, Frontline, 3–16 March 2001

- Exclusive Sundar Lal report on Hyderabad police action, Deccan Chronicle, 30 November 2013.

- In the Nizam's dominion, by Bret Wallach, University of Oklahoma

- A Blog by Narendra Luther on Operation Polo

- Armchair Historian – Operation Polo (Monday, 18 September 2006) – Contributed by Sidin Sunny Vadukut – Last Updated (Monday, 18 September 2006)

Districts of Hyderabad State

Administratively, Hyderabad State was made up of sixteen districts, grouped into four divisions:

- Aurangabad Division included Aurangabad, Beed, Nanded, and Parbhani districts;

- Gulbarga Division included Bidar District, Gulbarga, Osmanabad, and Raichur District;

- Gulshanabad Division or Medak Division included Atraf-i-Baldah (Hyderabad), Mahbubnagar district, Medak district, Nalgonda district (Nalgundah), and Nizamabad districts, and

- Warangal Division included Adilabad, Karimnagar, and Warangal districts (present Khammam district was part of warangal district).

1948–56

After the incorporation of Hyderabad State into India, M. K. Vellodi was appointed as Chief Minister of the state on 26 January 1950. He was a Senior Civil servant in the Government of India. He administered the state with the help of bureaucrats from Madras state and Bombay state.

In the 1952 Legislative Assembly election, Dr. Burgula Ramakrishna Rao was elected Chief minister of Hyderabad State. During this time there were violent agitations by some Telanganites to send back bureaucrats from Madras state, and to strictly implement 'Mulki-rules'(Local jobs for locals only), which was part of Hyderabad state law since 1919.[1]

Chief Ministers of Hyderabad State

Hyderabad State included nine Telugu districts of Telangana, four Kannada districts in Gulbarga division and four Marathi districts in Aurangabad division.

| No | Name | Term of office | Party[a] | Days in office | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M. K. Vellodi | 26 January 1950 | 6 March 1952 | Indian National Congress | rowspan=2 width=4px style="background-color: Template:Indian National Congress/meta/color" | | 770 |

| 2 | Burgula Ramakrishna Rao | 6 March 1952 | 31 October 1956 | 1701 | ||

Rajpramukhs

Hyderabad State had its last Nizam, HEH Mir Osman Ali Khan (b. 1886 -d. 1967) as Rajpramukh from 26 January 1950 to 31 October 1956.

Dissolution

In 1956 during the Reorganisation of the Indian States based along linguistic lines, the state of Hyderabad was split up among Andhra Pradesh, Bombay state (later divided into states of Maharashtra and Gujarat in 1960 with the original portions of Hyderabad becoming part of the state of Maharashtra) and Karnataka.

In December 1953, the States Reorganisation Commission was appointed to prepare for the creation of states on linguistic lines.[2] The commission, due to public demand, recommended disintegration of Hyderabad state and to merge Marathi speaking region, Maratwada, with Bombay state and Kannada speaking region with Mysore state. The Telugu speaking Telangana region of Hyderabad state with Andhra state.

Andhra state and Telangana were merged to form Andhra Pradesh state on 1 November 1956 after providing safeguards to Telangana in the form of Gentlemen's agreement Gulshanabad Division or Medak Division and Warangal Division were considered as area of Hyderabad's Telangana. However, when Hyderabad was merged in Andhra Pradesh state, substantial area of Adilabad (the area between Godavari and Penganga/Wardha/Pranahita rivers) was transferred to Maharashtra state. On 2 June 2014, the state of Telangana was formed splitting from the rest of Andhra Pradesh state and formed the 29th state of India, with Hyderabad as its capital.

State institutions

- Hyderabad Civil Service

- Jamia Nizamia

- Nizam College

- City College Hyderabad

- Nizam's Guaranteed State Railway

- Hyderabadi rupee

- State Bank of Hyderabad

- Nizamia observatory

- Osmania University

- Government Polytechnic College, Masab Tank

Palaces of Hyderabad State era

- Asman Garh Palace

- Basheer Bagh Palace

- Bella Vista, Hyderabad

- Chowmahalla Palace

- Errum Manzil

- Falaknuma Palace

- Hill Fort Palace

- Jubilee Hall

- King Kothi Palace

- Malwala palace

- Purani Haveli

- Vikhar Manzil

- Khilwat Palace

- Chowmohalla Palace

See also

Notes

- ^ This column only names the chief minister's party. The state government he headed may have been a complex coalition of several parties and independents; these are not listed here.

References

- ^ "Mulki agitation in Hyderabad state". Hinduonnet.com. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ^ "SRC submits report". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 1 October 2005. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

Bibliography

- Benichou, Lucien D. (2000), From Autocracy to Integration: Political Developments in Hyderabad State, 1938–1948, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-81-250-1847-6

- Chandra, Bipan; Mukherjee, Aditya; Mukherjee, Mridula (2008) [first published 1999], India Since Independence, Penguin Books India, ISBN 978-0-14-310409-4

- Hyder, Mohammed (2012), October Coup, A Memoir of the Struggle for Hyderabad, Roli Books, ISBN 978-8174368508

- Hodson, H. V. (1969), The Great Divide: Britain, India, Pakistan, London: Hutchinson, ISBN 978-0090971503

- Menon, V. P. (1956), The Story of Integration of the Indian States (PDF), Orient Longman

- Muralidharan, Sukumar (2014). "Alternate Histories: Hyderabad 1948 Compels a Fresh Evaluation of the Theology of India's Independence and Partition". History and Sociology of South Asia. 8 (2): 119–138. doi:10.1177/2230807514524091. S2CID 153722788.

- Noorani, A. G. (2014), The Destruction of Hyderabad, Hurst & Co, ISBN 978-1-84904-439-4

- Raghavan, Srinath (2010), War and Peace in Modern India, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-137-00737-7

- Smith, Wilfred Cantwell (January 1950), "Hyderabad: Muslim Tragedy", Middle East Journal, 4 (1): 27–51, JSTOR 4322137

- Zubrzycki, John (2006), The Last Nizam: An Indian Prince in the Australian Outback, Australia: Pan Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-330-42321-2

- Benichou, Lucien D. (2000), From Autocracy to Integration: Political Developments in Hyderabad State, 1938–1948, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-81-250-1847-6

- Faruqi, Munis D. (2013), "At Empire's End: The Nizam, Hyderabad and Eighteenth-century India", in Richard M. Eaton; Munis D. Faruqui; David Gilmartin; Sunil Kumar (eds.), Expanding Frontiers in South Asian and World History: Essays in Honour of John F. Richards, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–38, ISBN 978-1-107-03428-0

- Guha, Ramachandra (2008), India after Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy, Pab Macmillian, ISBN 0330396110

- Smith, Wilfred Cantwell (January 1950), "Hyderabad: Muslim Tragedy", Middle East Journal, 4 (1): 27–51, JSTOR 4322137

- Ram Narayan Kumar (1 April 1997), The Sikh unrest and the Indian state: politics, personalities, and historical retrospective, The University of Michigan, p. 99, ISBN 978-8-12-020453-9

- Jayanta Kumar Ray (2007), Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World, Pearson Education India, p. 206, ISBN 978-8-13-170834-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Further reading

- Beverley, Eric Lewis. Hyderabad, British India, and the World: Muslim Networks and Minor Sovereignty, c. 1850–1950 (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

- Faruqi, Munis D. (2013), "At Empire's End: The Nizam, Hyderabad and Eighteenth-century India", in Richard M. Eaton; Munis D. Faruqui; David Gilmartin; Sunil Kumar (eds.), Expanding Frontiers in South Asian and World History: Essays in Honour of John F. Richards, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–38, ISBN 978-1-107-03428-0

- Hyderabad State. Imperial Gazetteer of India Provincial Series. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers. 1989.

- Iyengar, Kesava (2007). Economic Investigations in the Hyderabad State 1939-1930. Vol. 1. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-6435-2.

- Leonard, Karen (1971). "The Hyderabad Political System and its Participants". Journal of Asian Studies. 30 (3): 569–582. doi:10.1017/s0021911800154841. JSTOR 2052461.

- Pernau, Margrit (2000). The Passing of Patrimonialism: Politics and Political Culture in Hyderabad, 1911–1948. Delhi: Manohar. ISBN 81-7304-362-0.

- Purushotham, Sunil (2015). "Internal Violence: The "Police Action" in Hyderabad". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 57 (2): 435–466. doi:10.1017/S0010417515000092.

- Sherman, Taylor C. "Migration, citizenship and belonging in Hyderabad (Deccan), 1946–1956." Modern Asian Studies 45#1 (2011): 81–107.

- Sherman, Taylor C. "The integration of the princely state of Hyderabad and the making of the postcolonial state in India, 1948–56." Indian Economic & Social History Review 44#4 (2007): 489–516.

- Various (2007). Hyderabad State List of Leading Officials, Nobles and Personages. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-3137-8.

- Zubrzycki, John (2006). The Last Nizam: An Indian Prince in the Australian Outback. Australia: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-42321-2.

External links

- Hyderabad City Information Portal

- Hyderabad: A Qur'anic Paradise in Architectural Metaphors

- From the Sundarlal Report – Muslim Genocide in 1948

- Manolya's legal fight

- About Razakars and Islamic ambitions

- Hyderabad

- Genealogy of the Nizams of Hyderabad

- Renaming villages by the Nizam

- Use dmy dates from July 2013

- Conflicts in 1948

- Wars involving India

- Political integration of India

- 1948 in India

- Military history of Hyderabad State

- Nehru administration

- History of Telangana

- History of Andhra Pradesh (1947–2014)

- Operations involving Indian special forces

- Religiously motivated violence in India

- Anti-Muslim violence in India

- History of Marathwada

- Annexation

- September 1948 events in Asia

- Invasions by India

- Historical Indian regions

- Princely states of India

- Empires and kingdoms of India

- Hyderabad State

- Former countries in South Asia

- Former polities of the Cold War

- Muslim princely states of India

- 1948 disestablishments in India

- 1724 establishments in India