IKBKG

NF-kappa-B essential modulator (NEMO) also known as inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit gamma (IKK-γ) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the IKBKG gene. NEMO is a subunit of the IκB kinase complex that activates NF-κB.[5] The human gene for IKBKG is located on the chromosome band Xq28.[6] Multiple transcript variants encoding different isoforms have been found for this gene.

Function

NEMO (IKK-γ) is the regulatory subunit of the inhibitor of IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which activates NF-κB resulting in activation of genes involved in inflammation, immunity, cell survival, and other pathways.

Clinical significance

Mutations in the IKBKG gene results in incontinentia pigmenti,[7] hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia,[8] and several other types of immunodeficiencies.

Incontinentia Pigmenti (IP) is an X-linked dominant disease caused by a mutation in the IKBKG gene. Since IKBKG helps activate NF-κB, which protects cells against TNF-alpha induced apoptosis, a lack of IKBKG (and hence a lack of active NF-κB) makes cells more prone to apoptosis.

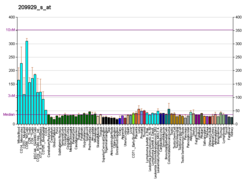

Moreover, NEMO has been shown to play a role in preeclampsia and may offer insights into the genetic etiology of this condition. An increased level of NEMO gene expression was found in the blood of pregnant women with preeclampsia and their children.[9] However, a decrease of the mRNA levels of total NEMO and the transcripts 1A, 1B, and 1C in placentas derived from preeclamptic women may be the main reason for intensified apoptosis.[9] Sanger sequencing has indicated two distinct variations in the 3’ UTR region of the NEMO gene in preeclamptic women (IKBKG:c.*368C>A and IKBKG:c.*402C>T).[10] The occurrence of a maternal TT genotype and either a TT genotype in the daughter or T allele in the son increases the risk of preeclampsia by 2.59 fold. The configuration of those maternal and fetal genotypes (TT mother/TT daughter or TT mother/T son) is also associated with the level of NEMO gene expression.[10]

NEMO deficiency syndrome is a rare genetic condition relating to a fault in IKBKG. It mostly affects males and has a highly variable set of symptoms and prognoses.[11]

As a drug target

A drug called NEMO Binding Domain (NBD) has been designed to inhibit activation of NF-κB.[12] NBD is a peptide that acts by binding to regulatory subunit NEMO (IKK-γ) thereby preventing it from binding subunits IKK-α and IKK-β and activating the IKK complex. In the absence of regulatory subunit IKK-γ the IKK complex is inactive, preventing the downstream signal transduction cascade leading to NF-κB activation. Binding of IKK-γ to IKK-α and IKK-β subunits activates the IKK complex leading to phosphorylation of IκB kinase, IκBα, and release of NF-κB dimers p105 and RELA to translocate to the nucleus and activate transcription of NF-κB responsive genes. In the presence of the NBD peptide, the IKK complex remains inactive and IκBα sequesters NF-κB dimers in the cytoplasm inhibiting transcription of NF-κB responsive genes. While NF-κB inhibitory drugs have previously been attractive to disease such as chronic inflammation and diabetes, specific cancers have been shown to have constitutive NF-κB activity.[13] Advanced B-cell lymphoma (ABC), a subtype of Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) has been shown to have fundamental and upregulated NF-κB activity.[13] ABC lymphoma also has the lowest survival rate compared to DLBCL subtypes, Germinal Center B-cell-like and Undefined Type 3 lymphoma, highlighting the great clinical need to define targets for cancer therapy.[13] Notably, the NBD peptide targets the inflammation induced NF-κB activation pathway sparing the protective functions of basal NF-κB activity allowing for greater therapeutic value and fewer undesired side effects.

The NBD peptide was designed by identifying the amino acid binding sequence on IKK-α and IKK-β to which NEMO binds.[12] A small region on the carboxyl terminus of IKK-α (L738-L743) and IKK-β (L737-L742) is essential for a stable interaction with NEMO and for the assembly of the active IKK complex. Henceforth this region is called the NEMO binding domain (NBD). The NBD peptide consists of the region from T735 to E745 of the IKK-β subunit fused with a sequence derived from the Antennapedia homeodomain that mediates membrane translocation. Furthermore, wild type NBD peptide has been shown to dose-dependently inhibit interaction of IKKB with NEMO compared to mutant controls.[12] Additionally, NF-κB activation was suppressed in HeLa cells after incubation with NBD wild type peptides.[12] Moreover, to better understand the potential efficacy of the NBD peptide in suppressing inflammation, NBD peptide was tested on collagen induced rheumatoid arthritis mouse models. Notably, aberrant NF-κB activity is strongly associated with many aspects of the pathology of rheumatoid arthritis. Mice injected with wild-type NBD peptide showed only slightly visual signs of paw and joint swelling whereas mice injected with PBS or mutant NBD control peptides developed severe joint inflammation.[14] Additionally, analysis of the number of osteoclasts present in the joints of rheumatoid arthritic showed to be more prevalent in mice treated with PBS or the mutant NBD peptide compared to the NBD wild type peptide.[14] Markedly, throughout the mouse model studies neither toxicity or lethality nor damage to kidneys or livers, was observed.

Despite the potential for NBD peptide as a viable NF- κB inhibitory drug, disadvantages arise because of its peptide form. Peptides as drugs lack membrane permeability, are poorly orally viable, and generally have lower metabolic stability than small molecule drugs.[15] Therefore, the NBD peptide is unable to be an orally available compound and must be administered either intravenously or via intraperitoneal injection.

Interactions

IKBKG has been shown to interact with:

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000269335 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000004221 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Rothwarf DM, Zandi E, Natoli G, Karin M (September 1998). "IKK-gamma is an essential regulatory subunit of the IkappaB kinase complex". Nature. 395 (6699): 297–300. Bibcode:1998Natur.395..297R. doi:10.1038/26261. PMID 9751060. S2CID 4421659.

- ^ Jin DY, Jeang KT (1999). "Isolation of full-length cDNA and chromosomal localization of human NF-kappaB modulator NEMO to Xq28". Journal of Biomedical Science. 6 (2): 115–20. doi:10.1159/000025378. PMID 10087442. S2CID 202651606.

- ^ Aradhya S, Woffendin H, Jakins T, Bardaro T, Esposito T, Smahi A, Shaw C, Levy M, Munnich A, D'Urso M, Lewis RA, Kenwrick S, Nelson DL (September 2001). "A recurrent deletion in the ubiquitously expressed NEMO (IKK-gamma) gene accounts for the vast majority of incontinentia pigmenti mutations". Human Molecular Genetics. 10 (19): 2171–9. doi:10.1093/hmg/10.19.2171. PMID 11590134.

- ^ Zonana J, Elder ME, Schneider LC, Orlow SJ, Moss C, Golabi M, Shapira SK, Farndon PA, Wara DW, Emmal SA, Ferguson BM (December 2000). "A novel X-linked disorder of immune deficiency and hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is allelic to incontinentia pigmenti and due to mutations in IKK-gamma (NEMO)". American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (6): 1555–62. doi:10.1086/316914. PMC 1287930. PMID 11047757.

- ^ a b Sakowicz A, Hejduk P, Pietrucha T, et al. (2016). "Finding NEMO in preeclampsia". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 214 (4): 538.e1–538.e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.11.002. PMID 26571191.

- ^ a b http://content.ebscohost.com/ContentServer.asp?T=P&P=AN&K=28654673&S=R&D=mdc&EbscoContent=dGJyMNHX8kSep7I4v%2BbwOLCmr1Cep7VSsq%2B4TLWWxWXS&ContentCustomer=dGJyMPGus0m0q7JQuePfgeyx43zx#page14 [dead link]

- ^ NEMO deficiency syndrome information Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children

- ^ a b c d May MJ, D'Acquisto F, Madge LA, Glöckner J, Pober JS, Ghosh S (September 2000). "Selective inhibition of NF-kappaB activation by a peptide that blocks the interaction of NEMO with the IkappaB kinase complex". Science. 289 (5484): 1550–4. Bibcode:2000Sci...289.1550M. doi:10.1126/science.289.5484.1550. PMID 10968790.

- ^ a b c Nogai H, Wenzel SS, Hailfinger S, Grau M, Kaergel E, Seitz V, Wollert-Wulf B, Pfeifer M, Wolf A, Frick M, Dietze K, Madle H, Tzankov A, Hummel M, Dörken B, Scheidereit C, Janz M, Lenz P, Thome M, Lenz G (September 2013). "IκB-ζ controls the constitutive NF-κB target gene network and survival of ABC DLBCL". Blood. 122 (13): 2242–50. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-06-508028. PMID 23869088. S2CID 18427175.

- ^ a b Strickland I, Ghosh S (November 2006). "Use of cell permeable NBD peptides for suppression of inflammation". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 65 (Suppl 3): iii75–82. doi:10.1136/ard.2006.058438. PMC 1798375. PMID 17038479.

- ^ Craik DJ, Fairlie DP, Liras S, Price D (January 2013). "The future of peptide-based drugs". Chemical Biology & Drug Design. 81 (1): 136–47. doi:10.1111/cbdd.12055. PMID 23253135. S2CID 9546063.

- ^ Wu CJ, Ashwell JD (February 2008). "NEMO recognition of ubiquitinated Bcl10 is required for T cell receptor-mediated NF-kappaB activation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (8): 3023–8. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.3023W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0712313105. PMC 2268578. PMID 18287044.

- ^ Hayden MS, Ghosh S (February 2004). "Keeping cartographers busy". Nature Cell Biology. 6 (2): 87–9. doi:10.1038/ncb0204-87. PMID 14755267. S2CID 32851397.

- ^ a b c Chen G, Cao P, Goeddel DV (February 2002). "TNF-induced recruitment and activation of the IKK complex require Cdc37 and Hsp90". Molecular Cell. 9 (2): 401–10. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00450-1. PMID 11864612.

- ^ Agou F, Ye F, Goffinont S, Courtois G, Yamaoka S, Israël A, Véron M (May 2002). "NEMO trimerizes through its coiled-coil C-terminal domain". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (20): 17464–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M201964200. PMID 11877453.

- ^ a b Deng L, Wang C, Spencer E, Yang L, Braun A, You J, Slaughter C, Pickart C, Chen ZJ (October 2000). "Activation of the IkappaB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain". Cell. 103 (2): 351–61. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00126-4. PMID 11057907. S2CID 18154645.

- ^ a b Shifera AS, Horwitz MS (March 2008). "Mutations in the zinc finger domain of IKK gamma block the activation of NF-kappa B and the induction of IL-2 in stimulated T lymphocytes". Molecular Immunology. 45 (6): 1633–45. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2007.09.036. PMID 18207244.

- ^ a b Chariot A, Leonardi A, Muller J, Bonif M, Brown K, Siebenlist U (October 2002). "Association of the adaptor TANK with the I kappa B kinase (IKK) regulator NEMO connects IKK complexes with IKK epsilon and TBK1 kinases". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (40): 37029–36. doi:10.1074/jbc.M205069200. PMID 12133833.

- ^ a b Wu RC, Qin J, Hashimoto Y, Wong J, Xu J, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW (May 2002). "Regulation of SRC-3 (pCIP/ACTR/AIB-1/RAC-3/TRAM-1) Coactivator activity by I kappa B kinase". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 22 (10): 3549–61. doi:10.1128/mcb.22.10.3549-3561.2002. PMC 133790. PMID 11971985.

- ^ Conze DB, Wu CJ, Thomas JA, Landstrom A, Ashwell JD (May 2008). "Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of IRAK-1 is required for interleukin-1 receptor- and toll-like receptor-mediated NF-kappaB activation". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 28 (10): 3538–47. doi:10.1128/MCB.02098-07. PMC 2423148. PMID 18347055.

- ^ a b Windheim M, Stafford M, Peggie M, Cohen P (March 2008). "Interleukin-1 (IL-1) induces the Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 to facilitate NEMO binding and the activation of IkappaBalpha kinase". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 28 (5): 1783–91. doi:10.1128/MCB.02380-06. PMC 2258775. PMID 18180283.

- ^ Prajapati S, Verma U, Yamamoto Y, Kwak YT, Gaynor RB (January 2004). "Protein phosphatase 2Cbeta association with the IkappaB kinase complex is involved in regulating NF-kappaB activity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (3): 1739–46. doi:10.1074/jbc.M306273200. PMID 14585847.

- ^ Zhang SQ, Kovalenko A, Cantarella G, Wallach D (March 2000). "Recruitment of the IKK signalosome to the p55 TNF receptor: RIP and A20 bind to NEMO (IKKgamma) upon receptor stimulation". Immunity. 12 (3): 301–11. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80183-1. PMID 10755617.

- ^ Leonardi A, Chariot A, Claudio E, Cunningham K, Siebenlist U (September 2000). "CIKS, a connection to Ikappa B kinase and stress-activated protein kinase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (19): 10494–9. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9710494L. doi:10.1073/pnas.190245697. PMC 27052. PMID 10962033.

- ^ Li X, Commane M, Nie H, Hua X, Chatterjee-Kishore M, Wald D, Haag M, Stark GR (September 2000). "Act1, an NF-kappa B-activating protein". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (19): 10489–93. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9710489L. doi:10.1073/pnas.160265197. PMC 27051. PMID 10962024.

- ^ Lamothe B, Campos AD, Webster WK, Gopinathan A, Hur L, Darnay BG (September 2008). "The RING domain and first zinc finger of TRAF6 coordinate signaling by interleukin-1, lipopolysaccharide, and RANKL". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (36): 24871–80. doi:10.1074/jbc.M802749200. PMC 2529010. PMID 18617513.

Further reading

- Rothwarf DM, Zandi E, Natoli G, Karin M (September 1998). "IKK-gamma is an essential regulatory subunit of the IkappaB kinase complex". Nature. 395 (6699): 297–300. Bibcode:1998Natur.395..297R. doi:10.1038/26261. PMID 9751060. S2CID 4421659.

- Mercurio F, Murray BW, Shevchenko A, Bennett BL, Young DB, Li JW, Pascual G, Motiwala A, Zhu H, Mann M, Manning AM (February 1999). "IkappaB kinase (IKK)-associated protein 1, a common component of the heterogeneous IKK complex". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 19 (2): 1526–38. doi:10.1128/mcb.19.2.1526. PMC 116081. PMID 9891086.

- Li Y, Kang J, Friedman J, Tarassishin L, Ye J, Kovalenko A, Wallach D, Horwitz MS (February 1999). "Identification of a cell protein (FIP-3) as a modulator of NF-kappaB activity and as a target of an adenovirus inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (3): 1042–7. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.1042L. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.3.1042. PMC 15347. PMID 9927690.

- Jin DY, Jeang KT (1999). "Isolation of full-length cDNA and chromosomal localization of human NF-kappaB modulator NEMO to Xq28". Journal of Biomedical Science. 6 (2): 115–20. doi:10.1159/000025378. PMID 10087442. S2CID 202651606.

- Jin DY, Giordano V, Kibler KV, Nakano H, Jeang KT (June 1999). "Role of adapter function in oncoprotein-mediated activation of NF-kappaB. Human T-cell leukemia virus type I Tax interacts directly with IkappaB kinase gamma". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (25): 17402–5. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.25.17402. PMID 10364167.

- Zhang SQ, Kovalenko A, Cantarella G, Wallach D (March 2000). "Recruitment of the IKK signalosome to the p55 TNF receptor: RIP and A20 bind to NEMO (IKKgamma) upon receptor stimulation". Immunity. 12 (3): 301–11. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80183-1. PMID 10755617.

- Smahi A, Courtois G, Vabres P, Yamaoka S, Heuertz S, Munnich A, Israël A, Heiss NS, Klauck SM, Kioschis P, Wiemann S, Poustka A, Esposito T, Bardaro T, Gianfrancesco F, Ciccodicola A, D'Urso M, Woffendin H, Jakins T, Donnai D, Stewart H, Kenwrick SJ, Aradhya S, Yamagata T, Levy M, Lewis RA, Nelson DL (May 2000). "Genomic rearrangement in NEMO impairs NF-kappaB activation and is a cause of incontinentia pigmenti. The International Incontinentia Pigmenti (IP) Consortium". Nature. 405 (6785): 466–72. doi:10.1038/35013114. PMID 10839543. S2CID 4416325.

- Inohara N, Koseki T, Lin J, del Peso L, Lucas PC, Chen FF, Ogura Y, Núñez G (September 2000). "An induced proximity model for NF-kappa B activation in the Nod1/RICK and RIP signaling pathways". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (36): 27823–31. doi:10.1074/jbc.M003415200. PMID 10880512.

- Ye Z, Connor JR (August 2000). "cDNA cloning by amplification of circularized first strand cDNAs reveals non-IRE-regulated iron-responsive mRNAs". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 275 (1): 223–7. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2000.3282. PMID 10944468.

- Li X, Commane M, Nie H, Hua X, Chatterjee-Kishore M, Wald D, Haag M, Stark GR (September 2000). "Act1, an NF-kappa B-activating protein". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (19): 10489–93. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9710489L. doi:10.1073/pnas.160265197. PMC 27051. PMID 10962024.

- Leonardi A, Chariot A, Claudio E, Cunningham K, Siebenlist U (September 2000). "CIKS, a connection to Ikappa B kinase and stress-activated protein kinase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (19): 10494–9. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9710494L. doi:10.1073/pnas.190245697. PMC 27052. PMID 10962033.

- May MJ, D'Acquisto F, Madge LA, Glöckner J, Pober JS, Ghosh S (September 2000). "Selective inhibition of NF-kappaB activation by a peptide that blocks the interaction of NEMO with the IkappaB kinase complex". Science. 289 (5484): 1550–4. Bibcode:2000Sci...289.1550M. doi:10.1126/science.289.5484.1550. PMID 10968790.

- Zonana J, Elder ME, Schneider LC, Orlow SJ, Moss C, Golabi M, Shapira SK, Farndon PA, Wara DW, Emmal SA, Ferguson BM (December 2000). "A novel X-linked disorder of immune deficiency and hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is allelic to incontinentia pigmenti and due to mutations in IKK-gamma (NEMO)". American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (6): 1555–62. doi:10.1086/316914. PMC 1287930. PMID 11047757.

- Xiao G, Sun SC (October 2000). "Activation of IKKalpha and IKKbeta through their fusion with HTLV-I tax protein". Oncogene. 19 (45): 5198–203. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203894. PMID 11064457. S2CID 29415593.

- Li XH, Fang X, Gaynor RB (February 2001). "Role of IKKgamma/nemo in assembly of the Ikappa B kinase complex". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (6): 4494–500. doi:10.1074/jbc.M008353200. PMID 11080499.

- Poyet JL, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES (February 2001). "vCLAP, a caspase-recruitment domain-containing protein of equine Herpesvirus-2, persistently activates the Ikappa B kinases through oligomerization of IKKgamma". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (5): 3183–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.C000792200. PMID 11113112.

- Jain A, Ma CA, Liu S, Brown M, Cohen J, Strober W (March 2001). "Specific missense mutations in NEMO result in hyper-IgM syndrome with hypohydrotic ectodermal dysplasia". Nature Immunology. 2 (3): 223–8. doi:10.1038/85277. PMID 11224521. S2CID 9425501.

- Döffinger R, Smahi A, Bessia C, Geissmann F, Feinberg J, Durandy A, Bodemer C, Kenwrick S, Dupuis-Girod S, Blanche S, Wood P, Rabia SH, Headon DJ, Overbeek PA, Le Deist F, Holland SM, Belani K, Kumararatne DS, Fischer A, Shapiro R, Conley ME, Reimund E, Kalhoff H, Abinun M, Munnich A, Israël A, Courtois G, Casanova JL (March 2001). "X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency is caused by impaired NF-kappaB signaling". Nature Genetics. 27 (3): 277–85. doi:10.1038/85837. PMID 11242109. S2CID 24898789.

- Simpson JC, Wellenreuther R, Poustka A, Pepperkok R, Wiemann S (September 2000). "Systematic subcellular localization of novel proteins identified by large-scale cDNA sequencing". EMBO Reports. 1 (3): 287–92. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kvd058. PMC 1083732. PMID 11256614.

- Galgóczy P, Rosenthal A, Platzer M (June 2001). "Human-mouse comparative sequence analysis of the NEMO gene reveals an alternative promoter within the neighboring G6PD gene". Gene. 271 (1): 93–8. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00492-9. PMID 11410370.

External links

- IKBKG+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- GeneReviews/NIH/NCBI/UW entry on Incontinentia Pigmenti

- OMIM IKBKG

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Anophthalmia / Microphthalmia Overview