Serotonin transporter

Template:PBB The serotonin transporter (SERT) is a monoamine transporter protein.

This protein integral membrane protein that transports the neurotransmitter serotonin from synaptic spaces into presynaptic neurons. This transport of serotonin by the SERT protein terminates the action of serotonin and recycles it in a sodium-dependent manner. This protein is the target of many antidepressant medications, including those of the SSRI class.[1] It is a member of the sodium:neurotransmitter symporter family. A repeat length polymorphism in the promoter of this gene has been shown to affect the rate of serotonin uptake and may play a role in sudden infant death syndrome, aggressive behavior in Alzheimer disease patients, post-traumatic stress disorder and depression-susceptibility in people experiencing emotional trauma.[2]

Function

The serotonin transporter removes serotonin from the synaptic cleft back into the synaptic boutons. Thus, it terminates the effects of serotonin and simultaneously enables its reuse by the presynaptic neuron.[1]

Neurons communicate by using chemical messages like serotonin between cells. The transporter protein, by recycling serotonin, regulates its concentration in a gap, or synapse, and thus its effects on a receiving neuron’s receptors.

Medical studies have shown that changes in serotonin transporter metabolism appear to be associated with many different phenomena, including alcoholism, clinical depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), romantic love,[3] hypertension and generalized social phobia.[4]

The serotonin transporter is also present in platelets; there, serotonin functions as a vasoconstrictive substance.

Pharmacology

SERT spans the plasma membrane 12 times. It belongs to NE, DA, SERT monoamine transporter family. Transporters are important sites for agents that treat psychiatric disorders. Both drugs that reduce the binding of serotonin to transporters (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs) and, less often, that increase it (selective serotonin reuptake enhancers, or SSREs) are used to treat mental disorders. About half of patients with OCD are treated with SSRIs. Fluoxetine is an example of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and tianeptine is an example of a selective serotonin reuptake enhancer.

Ligands

- compound (+)-12a: Ki = 180 pM at hSERT; >1000-fold selective over hDAT, hNET, 5-HT1A, and 5-HT6.[5] Isosteres[6]

- compound 4b: Ki = 17 pM; 710-fold and 11,100-fold selective over DAT and NET[7]

- 3-cis-(3-Aminocyclopentyl)indole 8a: 220pM[8]

Genetics

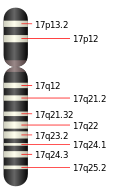

The gene that encodes the serotonin transporter is called solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, serotonin), member 4 (SLC6A4, see Solute carrier family). In humans the gene is found on chromosome 17 on location 17q11.1–q12.[9]

Mutations associated with the gene may result in changes in serotonin transporter function, and experiments with mice have identified more the 50 different phenotypic changes as a result of genetic variation. These phenotypic changes may, e.g., be increased anxiety and gut dysfunction.[10] Some of the human genetic variations associated with the gene are:[10]

- Length variation in the serotonin-transporter-gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR)

- rs25531 — a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the 5-HTTLPR

- rs25532 — another SNP in the 5-HTTLPR

- STin2 — a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) in the functional intron 2

- G56A on the second exon

- I425V on the ninth exon

Length variation in 5-HTTLPR

The promotor region of the SLC6A4 gene contains a polymorphism with "short" and "long" repeats in a region: 5-HTT-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR or SERTPR).[11] The short variation has 14 repeats of a sequence while the long variation has 16 repeats.[9] The short variation leads to less transcription for SLC6A4, and it has been found that it can partly account for anxiety-related personality traits.[12] This polymorphism has been extensively investigated in over 300 scientific studies (as of 2006).[13] The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism may be subdivided further: One study published in 2000 found 14 allelic variants (14-A, 14-B, 14-C, 14-D, 15, 16-A, 16-B, 16-C, 16-D, 16-E, 16-F, 19, 20 and 22) in a group of around 200 Japanese and Caucasian people.[9]

In addition to altering the expression of SERT protein and concentrations of extracellular serotonin in the brain, the 5-HTTLPR variation is associated with changes in brain structure. One study found less grey matter in perigenual anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala for short allele carriers of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism compared to subjects with the long/long genotype.[14]

In contrast, a 2008 meta-analysis found no significant overall association between the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and autism.[15] A hypothesized gene-environment interaction between the short/short allele of the 5-HTTLPR and life stress as predictor for major depression has suffered a similar fate: after an influential[16] initial report[17] there were mixed results in replication,[18] and a 2009 meta-analysis was negative.[19] See 5-HTTLPR for more information.

rs25532

rs25532 is a SNP (C>T) close to the site of 5-HTTLPR. It has been examined in connection with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).[20]

I425V

I425V is a rare mutation on the ninth exon. Researchers have found this genetic variation in unrelated families with OCD, and that it leads to faulty transporter function and regulation. A second variant in the same gene of some patients with this mutation suggests a genetic "double hit", resulting in greater biochemical effects and more severe symptoms.[21][22][23]

VNTR in STin2

Another noncoding polymorphism is a VNTR in the second intron (STin2). It is found with three alleles: 9, 10 and 12 repeats. A meta-analysis has found that the 12 repeat allele of the STin2 VNTR polymorphism had some minor (with odds ratio 1.24) but statistically significant association with schizophrenia.[24] A 2008 meta-analysis found no significant overall association between the STin2 VNTR polymorphism and autism.[15] Furthermore a 2003 meta-analysis of affective disorders, major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder, found a little association to the intron 2 VNTR polymorphism, but the results of the meta-analysis depended on a large effect from one individual study.[25]

The polymorphism has also been related to personality traits with a Russian study from 2008 finding individuals with the STin2.10 allele having lower neuroticism score as measured with the Eysenck Personality Inventory.[26]

Neuroimaging

The distribution of the serotonin transporter in the brain may be imaged with positron emission tomography using radioligands called DASB and DAPP, and the first studies on the human brain were reported in 2000.[27] DASB and DAPP are not the only radioligands for the serotonin transporter. There are numerous others, with the most popular probably being the β-CIT radioligand with an iodine-123 isotope that is used for brain scanning with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).[28] The radioligands have been used to examine whether variables such as age, gender or genotype are associated with differential serotonin transporter binding.[29] Healthy subjects that have a high score of neuroticism — a personality trait in the Revised NEO Personality Inventory — have been found to have more serotonin transporter binding in the thalamus.[30]

Neuroimaging and genetics

Studies on the serotonin transporter have combined neuroimaging and genetics methods, e.g., a voxel-based morphometry study found less grey matter in perigenual anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala for short allele carriers of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism compared to subjects with the long/long genotype.[14]

References

- ^ a b Squire, edited by Larry; et al. (2008). Fundamental neuroscience (3rd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier / Academic Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-12-374019-9.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ^ "Entrez Gene: SLC6A4 solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, serotonin), member 4".

- ^ Marazziti D, Akiskal HS, Rossi A, Cassano GB (1999). "Alteration of the platelet serotonin transporter in romantic love". Psychological Medicine. 29 (3): 741–745. doi:10.1017/S0033291798007946. PMID 10405096.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ van der Wee NJ, van Veen JF, Stevens H, van Vliet IM, van Rijk PP, Westenberg HG (2008). "Increased Serotonin and Dopamine Transporter Binding in Psychotropic Medication–Naïve Patients with Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder Shown by 123I-β-(4-Iodophenyl)-Tropane SPECT". The Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 49 (5): 757–763. doi:10.2967/jnumed.107.045518. PMID 18413401.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mattson RJ, Catt JD, Denhart DJ; et al. (2005). "Conformationally restricted homotryptamines. 2. Indole cyclopropylmethylamines as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors". J. Med. Chem. 48 (19): 6023–34. doi:10.1021/jm0503291. PMID 16162005.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dalton King H, Denhart DJ, Deskus JA; et al. (2007). "Conformationally restricted homotryptamines. Part 4: Heterocyclic and naphthyl analogs of a potent selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor". Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 17 (20): 5647–51. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.07.083. PMID 17766113.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tamagnan G, Alagille D, Fu X; et al. (2005). "Synthesis and monoamine transporter affinity of new 2beta-carbomethoxy-3beta-[4-(substituted thiophenyl)]phenyltropanes: discovery of a selective SERT antagonist with picomolar potency". Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 15 (4): 1131–3. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.014. PMID 15686927.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ King HD, Meng Z, Deskus JA; et al. (2010). "Conformationally restricted homotryptamines. Part 7: 3-cis-(3-aminocyclopentyl)indoles as potent selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors". J. Med. Chem. 53 (21): 7564–72. doi:10.1021/jm100515z. PMID 20949929.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c M. Nakamura, S. Ueno, A. Sano & H. Tanabe (2000). "The human serotonin transporter gene linked polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) shows ten novel allelic variants". Molecular Psychiatry. 5 (1): 32–38. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000698. PMID 10673766.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Murphy DL, Lesch KP (2008). "Targeting the murine serotonin transporter: insights into human neurobiology". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 9 (2): 85–96. doi:10.1038/nrn2284. PMID 18209729.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Heils A, Teufel A, Petri S, Stöber G, Riederer P, Bengel D, Lesch KP (1996). "Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression". Journal of Neurochemistry. 66 (6): 2621–2624. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66062621.x. PMID 8632190.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Benjamin J, Müller CR,Hamer DH, Murphy DL (1996). "Association of Anxiety-Related Traits with a Polymorphism in the Serotonin Transporter Gene Regulatory Region". Science. 274 (5292): 1527–31. doi:10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. PMID 8929413.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wendland JR, Martin BJ, Kruse MR, Lesch KP, Murphy DL (2006). "Simultaneous genotyping of four functional loci of human SLC6A4, with a reappraisal of 5-HTTLPR and rs255531". Molecular Psychiatry. 274 (3): 1–3. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001789. PMID 16402131.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Pezawas L, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Drabant EM, Verchinski BA, Munoz KE, Kolachana BS, Egan MF, Mattay VS, Hariri AR, Weinberger DR (2005). "5-HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate-amygdala interactions: a genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression". Nature Neuroscience. 8 (6): 828–34. doi:10.1038/nn1463. PMID 15880108.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Huang CH, Santangelo SL (2008). "Autism and serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 147B (6): 903–13. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.30720. PMID 18286633.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19890228, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19890228instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.1083968, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.1083968instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4002067, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/sj.mp.4002067instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1001/jama.2009.878, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1001/jama.2009.878instead. - ^ Wendland JR, Moya PR, Kruse MR, Ren-Patterson RF, Jensen CL, Timpano KR, Murphy DL (2008). "A novel, putative gain-of-function haplotype at SLC6A4 associates with obsessive-compulsive disorder". Human Molecular Genetics. 17 (5): 717–713. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddm343. PMID 18055562.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ozaki N, Goldman D, Kaye WH, Plotnicov K, Greenberg BD, Lappalainen J, Rudnick G,Murphy DL (2003). "Serotonin transporter missense mutation associated with a complex neuropsychiatric phenotype". Molecular Psychiatry. 8 (11): 933–936. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001365. PMID 14593431.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) News article:- Reuters (2003-10-27). "Gene Found for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder". Mental Health E-News. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help)

- Reuters (2003-10-27). "Gene Found for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder". Mental Health E-News. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ^

Delorme R, Betancur C, Wagner M, Krebs MO, Gorwood P, Pearl P, Nygren G, Durand CM, Buhtz F, Pickering P, Melke J, Ruhrmann S, Anckarsäter H, Chabane N, Kipman A,Reck C, Millet B, Roy I, Mouren-Simeoni MC, Maier W, Råstam M, Gillberg C, Leboyer M, Bourgeron T (2005). "Support for the association between the rare functional variant I425V of the serotonin transporter gene and susceptibility to obsessive compulsive disorder". Molecular Psychiatry. 10 (12): 1059–1061. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001728. PMC 2547479. PMID 16088327.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stephen Wheless. ""The OCD Gene" Popular Press v. Scientific Literature: Is SERT Responsible for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder?". Davidson College. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ^ Fan JB, Sklar P (2005). "Meta-analysis reveals association between serotonin transporter gene STin2 VNTR polymorphism and schizophrenia". Molecular Psychiatry. 10 (10): 928–938. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001690. PMID 15940296.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Anguelova M, Benkelfat C, Turecki G (2003). "A systematic review of association studies investigating genes coding for serotonin receptors and the serotonin transporter: I. Affective disorders". Molecular Psychiatry. 8 (6): 574–591. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001328. PMID 12851635.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kazantseva AV, Gaysina DA, Faskhutdinova GG, Noskova T, Malykh SB,Khusnutdinova EK (2008). "Polymorphisms of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR, A/G SNP in 5-HTTLPR, and STin2 VNTR) and their relation to personality traits in healthy individuals from Russia". Psychiatric Genetics. 18 (4): 167–166. doi:10.1097/YPG.0b013e328304deb8. PMID 18628678.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Houle S, Ginovart N, Hussey D, Meyer JH, Wilson AA (2000). "Imaging the serotonin transporter with positron emission tomography: initial human studies with [11C]DAPP and [11C]DASB". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 27 (11): 1719–22. doi:10.1007/s002590000365. PMID 11105830.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ T. Brücke, J. Kornhuber, P. Angelberger, S. Asenbaum, H. Frassine, I. Podreka (1993). "SPECT imaging of dopamine and serotonin transporters with [123I]β-CIT. Binding kinetics in the human brain". Journal of Neural Transmission. 94 (2): 137–146. doi:10.1007/BF01245007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brust P, Hess S, Müller U, Szabo Z (2006). "Neuroimaging of the Serotonin Transporter — Possibilities and Pitfalls" (PDF). Current Psychiatry Reviews. 2 (1): 111–149. doi:10.2174/157340006775101508.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Takano A, Arakawa R, Hayashi M, Takahashi H, Ito H, Suhara T (2007). "Relationship between neuroticism personality trait and serotonin transporter binding". Biological Psychiatry. 62 (6): 588–592. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.007. PMID 17336939.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- NIH press release: Serotonin Transporter Gene Shown to Influence College Drinking Habits

- Roiser JP, Cook LJ, Cooper JD, Rubinsztein DC, Sahakian BJ (2005). "Association of a Functional Polymorphism in the Serotonin Transporter Gene With Abnormal Emotional Processing in Ecstasy Users". American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (3): 609–612. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.609. PMC 2631647. PMID 15741482.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)