The Holocaust: Difference between revisions

→Trials: Actually 1 June Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 518: | Line 518: | ||

In 1988, West Germany allocated another $125 million for reparations. Companies such as [[BMW]], [[Deutsche Bank]], [[Ford]], [[Opel]], [[Siemens]], and [[Volkswagen]] faced lawsuits for their use of [[Forced labour under German rule during World War II|forced labor during the war]].<ref name=YVReparations/> In response, Germany set up the [[Foundation "Remembrance, Responsibility and Future"|"Remembrance, Responsibility and Future" Foundation]] in 2000, which paid €4.45 billion to former slave laborers (up to €7,670 each).<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/leistungen/direktleistungen/leistungsprogramm/index.html.en |title=Payment Programme of the Foundation EVZ |publisher=[[German Federal Archives|Bundesarchiv]] |accessdate=5 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181005014933/http://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/leistungen/direktleistungen/leistungsprogramm/index.html.en |archive-date=5 October 2018 |dead-url=no |df=dmy-all }}</ref> In 2013, Germany agreed to provide €772 million to fund nursing care, social services, and medication for 56,000 Holocaust survivors around the world.<ref>{{cite news |author=Staff |title=Holocaust Reparations: Germany to Pay 772 Million Euros to Survivors |date=29 May 2013 |newspaper=Spiegel Online International |url=http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/germany-to-pay-772-million-euros-in-reparations-to-holocaust-survivors-a-902528.html |access-date=7 December 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141213061723/http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/germany-to-pay-772-million-euros-in-reparations-to-holocaust-survivors-a-902528.html |archive-date=13 December 2014 |dead-url=no |df=dmy-all }}</ref> The French state-owned railway company, the [[SNCF]], agreed in 2014 to pay $60 million to Jewish-American survivors, around $100,000 each, for its role in the [[Timeline of deportations of French Jews to death camps|transport of 76,000 Jews from France]] to extermination camps between 1942 and 1944.<ref>{{cite news |author=Staff |title=Pour le rôle de la SNCF dans la Shoah, Paris va verser 100 000 euros à chaque déporté américain |newspaper=Le Monde |language=fr |url=http://www.lemonde.fr/ameriques/article/2014/12/05/etats-unis-paris-va-indemniser-les-victimes-de-la-shoah-transportees-par-la-sncf_4535530_3222.html |date=5 December 2014 |access-date=7 December 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141205193821/http://www.lemonde.fr/ameriques/article/2014/12/05/etats-unis-paris-va-indemniser-les-victimes-de-la-shoah-transportees-par-la-sncf_4535530_3222.html |archive-date=5 December 2014 |dead-url=no |df=dmy-all }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |author=Davies, Lizzie |date=17 February 2009 |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/feb/17/france-admits-deporting-jews |title=France responsible for sending Jews to concentration camps, says court |newspaper=The Guardian |access-date=9 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171010004913/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/feb/17/france-admits-deporting-jews |archive-date=10 October 2017 |dead-url=no |df=dmy-all }}</ref>{{sfn|Bazyler|2005|p=173}} |

In 1988, West Germany allocated another $125 million for reparations. Companies such as [[BMW]], [[Deutsche Bank]], [[Ford]], [[Opel]], [[Siemens]], and [[Volkswagen]] faced lawsuits for their use of [[Forced labour under German rule during World War II|forced labor during the war]].<ref name=YVReparations/> In response, Germany set up the [[Foundation "Remembrance, Responsibility and Future"|"Remembrance, Responsibility and Future" Foundation]] in 2000, which paid €4.45 billion to former slave laborers (up to €7,670 each).<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/leistungen/direktleistungen/leistungsprogramm/index.html.en |title=Payment Programme of the Foundation EVZ |publisher=[[German Federal Archives|Bundesarchiv]] |accessdate=5 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181005014933/http://www.bundesarchiv.de/zwangsarbeit/leistungen/direktleistungen/leistungsprogramm/index.html.en |archive-date=5 October 2018 |dead-url=no |df=dmy-all }}</ref> In 2013, Germany agreed to provide €772 million to fund nursing care, social services, and medication for 56,000 Holocaust survivors around the world.<ref>{{cite news |author=Staff |title=Holocaust Reparations: Germany to Pay 772 Million Euros to Survivors |date=29 May 2013 |newspaper=Spiegel Online International |url=http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/germany-to-pay-772-million-euros-in-reparations-to-holocaust-survivors-a-902528.html |access-date=7 December 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141213061723/http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/germany-to-pay-772-million-euros-in-reparations-to-holocaust-survivors-a-902528.html |archive-date=13 December 2014 |dead-url=no |df=dmy-all }}</ref> The French state-owned railway company, the [[SNCF]], agreed in 2014 to pay $60 million to Jewish-American survivors, around $100,000 each, for its role in the [[Timeline of deportations of French Jews to death camps|transport of 76,000 Jews from France]] to extermination camps between 1942 and 1944.<ref>{{cite news |author=Staff |title=Pour le rôle de la SNCF dans la Shoah, Paris va verser 100 000 euros à chaque déporté américain |newspaper=Le Monde |language=fr |url=http://www.lemonde.fr/ameriques/article/2014/12/05/etats-unis-paris-va-indemniser-les-victimes-de-la-shoah-transportees-par-la-sncf_4535530_3222.html |date=5 December 2014 |access-date=7 December 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141205193821/http://www.lemonde.fr/ameriques/article/2014/12/05/etats-unis-paris-va-indemniser-les-victimes-de-la-shoah-transportees-par-la-sncf_4535530_3222.html |archive-date=5 December 2014 |dead-url=no |df=dmy-all }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |author=Davies, Lizzie |date=17 February 2009 |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/feb/17/france-admits-deporting-jews |title=France responsible for sending Jews to concentration camps, says court |newspaper=The Guardian |access-date=9 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171010004913/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/feb/17/france-admits-deporting-jews |archive-date=10 October 2017 |dead-url=no |df=dmy-all }}</ref>{{sfn|Bazyler|2005|p=173}} |

||

Germany also paid over $500 million in subsidies for Israel's purchases of [[Dolphin-class submarine|''Dolphin''-class submarines]] since the 1990s, in part as reparations for the Holocaust and its weapons' sales to Iraqi dictator [[Saddam Hussein]] which were [[Gulf War#Iraqi Scud missile strikes on Israel and Saudi Arabia|used against Israeli civilians]],<ref>https://m.jpost.com/Defense/Germany-willing-to-fund-6th-Dolphin-class-sub-for-Israel</ref><ref name="iraqwatch.org">{{cite web |url=http://www.iraqwatch.org/profiles/missile.html |title=Iraq's Missiles" a Brief History |publisher=IraqWatch.org |accessdate=25 December 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150218050214/http://www.iraqwatch.org/profiles/missile.html |archive-date=18 February 2015 |dead-url=yes |df=dmy-all }}</ref> and in part to boost the German manufacturing industry.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://dspace.cigilibrary.org/jspui/bitstream/123456789/24800/1/European%20defense%20industry.pdf?1 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131111193710/http://dspace.cigilibrary.org/jspui/bitstream/123456789/24800/1/European%20defense%20industry.pdf?1 |dead-url=yes |archive-date=2013-11-11 |title=The European Defense Industry: Prospects for Consolidation |publisher=UNISCI Discussion Papers |last=Guay |first=Terrence |date=October 2005 |accessdate=25 December 2014 }}</ref><ref name="globalsec">{{cite web|url=http://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/world/israel/sub.htm |title=Israel: Submarines |accessdate=25 July 2011 |website=[[GlobalSecurity.org]] |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110604012228/http://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/world/israel/sub.htm |archivedate=June 4, 2011 }}</ref> |

|||

===Uniqueness question=== |

===Uniqueness question=== |

||

Revision as of 20:45, 21 February 2019

| The Holocaust | |

|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |

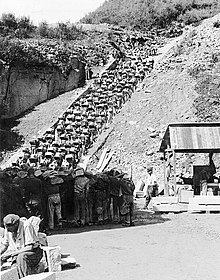

Hungarian Jews arriving at Auschwitz II-Birkenau in German-occupied Poland, May 1944. Most were "selected" to go straight to the gas chambers.[1] (from the Auschwitz Album) | |

| Location | Nazi Germany and German-occupied Europe |

| Date | 1941–1945[2] |

Attack type | Genocide, ethnic cleansing |

| Deaths | Around 6 million European Jews;[a] using broadest definition, 17 million victims[b] |

| Perpetrators | Nazi Germany and its allies |

| Motive | Antisemitism |

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah,[c] was a genocide in which Nazi Germany, aided by its collaborators, systematically murdered some six million European Jews—around two-thirds of the Jewish population of Europe—between 1941 and 1945, during World War II.[a][d] Jews were targeted for extermination as part of a larger event during the Holocaust era, in which Germany and its collaborators persecuted and murdered other groups, including Slavs (chiefly ethnic Poles, Soviet prisoners of war, and Soviet citizens); the Roma; the "incurably sick"; political and religious dissenters such as communists and Jehovah's Witnesses; and gay men, resulting in up to 17 million deaths overall.[b]

Germany implemented the persecution in stages. Following Adolf Hitler's rise to power in 1933, the government took steps to exclude Jews from civil society, which included organizing a boycott of Jewish businesses and passing the Nuremberg Laws in 1935. Starting in 1933, the Nazis built a network of concentration camps in Germany for political opponents and people deemed "undesirable". After the invasion of Poland in 1939, the regime set up ghettos to segregate Jews. Over 42,000 camps, ghettos, and other detention sites were established across occupied Europe.[6]

The deportation of Jews to the ghettos culminated in the policy of extermination the Nazis called the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question", discussed by senior Nazi officials at the Wannsee Conference in Berlin in January 1942. As German forces captured territories in the East, all anti-Jewish measures were radicalized. Under the coordination of the SS, with directions from the highest leadership of the Nazi Party, killings were committed within Germany itself, throughout occupied Europe, and across all territories controlled by the Axis powers. Paramilitary death squads called Einsatzgruppen, in cooperation with Wehrmacht police battalions and local collaborators, murdered around 1.3 million Jews in mass shootings between 1941 and 1945. By mid-1942, victims were being deported from the ghettos in sealed freight trains to extermination camps where, if they survived the journey, they were killed in gas chambers. The killing continued until the end of World War II in Europe in May 1945.

| Part of a series on |

| The Holocaust |

|---|

|

Terminology and scope

Terminology

The term holocaust, first used in 1895 to describe the massacre of Armenians,[7] comes from the Template:Lang-el; ὅλος hólos, "whole" + καυστός kaustós, "burnt offering".[8][e] The Century Dictionary defined it in 1904 as "a sacrifice or offering entirely consumed by fire, in use among the Jews and some pagan nations".[f]

The biblical term shoah (Template:Lang-he-n), meaning "destruction", became the standard Hebrew term for the murder of the European Jews, first used in a pamphlet in 1940, Sho'at Yehudei Polin ("Sho'ah of Polish Jews"), published by the United Aid Committee for the Jews in Poland.[11][12][7] In October 1941 the magazine The American Hebrew used the phrase "before the Holocaust", apparently to refer to the situation in Europe,[13] and in May 1943 The New York Times, discussing the Bermuda Conference, referred to the "hundreds of thousands of European Jews still surviving the Nazi Holocaust".[14] In 1968 the Library of Congress created a new category, "Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)";[15] the term was popularized in the United States by the NBC mini-series Holocaust (1978), about a fictional family of German Jews.[16] As non-Jewish groups began to count themselves as victims of the Holocaust too, many Jews chose to use the terms Shoah or Churban instead.[13][g] The Nazis used the phrase "Final Solution to the Jewish Question" (Template:Lang-de).[18]

Definition

Most Holocaust historians define the Holocaust as the enactment, between 1941 and 1945, of the German state policy to exterminate the European Jews.[a] In Teaching the Holocaust (2015), Michael Gray, a specialist in Holocaust education in high schools, offers three definitions: (a) "the persecution and murder of Jews by the Nazis and their collaborators between 1933 and 1945", which views the events of Kristallnacht in Germany in 1938 as an early phase of the Holocaust; (b) "the systematic mass murder of the Jews by the Nazi regime and its collaborators between 1941 and 1945", which acknowledges the shift in German policy in 1941 toward the extermination of the Jewish people in Europe; and (c) "the persecution and murder of various groups by the Nazi regime and its collaborators between 1933 and 1945", which includes all the Nazis' victims. The third definition fails, Gray writes, to acknowledge that only the Jewish people were singled out for annihilation.[26]

Hitler came to see the Jews as "uniquely dangerous to Germany", according to Peter Hayes, "and therefore uniquely destined to disappear completely from the Reich and all territories subordinate to it". The persecution and murder of other groups was much less consistent. For example, he writes, the Nazis regarded the Slavs as "sub-human", but their treatment consisted of "enslavement and gradual attrition", while "some Slavs—Slovaks, Croats, Bulgarians, some Ukrainians—[were] allotted a favored place in Hitler's New Order".[20]

Dan Stone, a specialist in the historiography of the Holocaust, lists ethnic Poles, Ukrainians, Soviet prisoners of war, Jehovah's Witnesses, black Germans, and homosexuals as among the groups persecuted by the Nazis; he writes that the occupation of eastern Europe can also be viewed as genocidal.[h] But the German attitude toward the Jews was different in kind, he argues. The Nazis regarded the Jews not as racially inferior, deviant, or enemy nationals, as they did other groups,[i] but as a Gegenrasse: "a 'counter-race', that is to say, not really human at all". The Holocaust, for Stone, is therefore defined as the genocide of the Jews, although he argues that it cannot be "properly historically situated without understanding the 'Nazi empire' with its grandiose demographic plans".[24] Donald Niewyk and Francis Nicosia, in The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust (2000), favour a definition that focuses on the Jews, Roma, and Aktion T4 victims: "The Holocaust—that is, Nazi genocide—was the systematic, state-sponsored murder of entire groups determined by heredity. This applied to Jews, Gypsies, and the handicapped."[5]

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum defines the Holocaust as the "systematic, bureaucratic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its collaborators",[28] distinguishing between the Holocaust and the targeting of other groups during "the era of the Holocaust". The latter include those persecuted because they were viewed as inferior, including for reasons of race or ethnicity (such as the Roma, ethnic Poles, Russians, and the disabled); and those targeted because of their beliefs or behavior (such as Jehovah's Witnesses, communists, and homosexuals).[29] In the UK, the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust, a British government charity, similarly defines the Holocaust as the systematic attempt, between 1941 and 1945, to annihilate the European Jews.[30] Yad Vashem, Israel's Holocaust memorial, defines it as "the murder of approximately six million Jews by the Nazis and their collaborators" between the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 and the end of the war in Europe in May 1945.[31] According to Yad Vashem, most historians regard January 1933, when Hitler was named chancellor of Germany, as the start of the "Holocaust era".[32]

Distinctive features

Genocidal state

The logistics of the mass murder turned the country into what Michael Berenbaum called a "genocidal state". Bureaucrats identified who was a Jew, confiscated property, and scheduled trains to deport them. Companies fired Jews and later used them as slave labor. Universities dismissed Jewish faculty and students. German pharmaceutical companies tested drugs on camp prisoners; other companies built the crematoria.[33] As prisoners entered the death camps, they were ordered to surrender all personal property, which was catalogued and tagged before being sent to Germany for reuse or recycling.[34] Through a concealed account, the German National Bank helped launder valuables stolen from the victims.[35]

The industrialization and scale of the murder was unprecedented. The killings were systematically conducted in virtually all areas of occupied Europe—more than 20 occupied countries.[36] Close to three million Jews in occupied Poland and between 700,000 and 2.5 million Jews in the Soviet Union were killed. Hundreds of thousands more died in the rest of Europe.[37] Victims were transported in sealed freight trains from all over Europe to extermination camps equipped with gas chambers.[38] The stationary facilities grew out of Nazi experiments with poison gas during the Aktion T4 mass murder ("euthanasia") programme against the disabled and mentally ill, which began in 1939.[39] The Germans set up six extermination camps in Poland: Auschwitz II-Birkenau (established October 1941); Majdanek (October 1941); Chełmno (December 1941); and in 1942 the three Operation Reinhard camps at Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka.[40][41]

Eberhard Jäckel writes that it was the first time a state had thrown its power behind the idea that an entire people should be wiped out.[j] Anyone with three or four Jewish grandparents was to be exterminated,[43] and complex rules were devised to deal with Mischlinge (half and quarter Jews, or "mixed breeds").[44] Without the help of local collaborators, the Germans would not have been able to extend the Holocaust across most of Europe;[45] over 200,000 people are estimated to have been Holocaust perpetrators.[46] Saul Friedländer writes: "Not one social group, not one religious community, not one scholarly institution or professional association in Germany and throughout Europe declared its solidarity with the Jews." Some Christian churches declared, according to Friedländer, "that converted Jews should be regarded as part of the flock, but even then only up to a point".[47] Discussions at the Wannsee Conference in January 1942 make it clear that the German "final solution of the Jewish question" was intended eventually to include Britain and all the neutral states in Europe, including Ireland, Switzerland, Turkey, Sweden, Portugal, and Spain.[48]

Medical experiments

Medical experiments conducted on camp inmates by the SS were another distinctive feature.[49] At least 7,000 prisoners were subjected to experiments; most died as a result, during the experiments or later.[50] Twenty-three senior physicians and other medical personnel were charged at Nuremberg, after the war, with crimes against humanity. They included the head of the German Red Cross, tenured professors, clinic directors, and biomedical researchers.[51] Experiments took place at Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Dachau, Natzweiler-Struthof, Neuengamme, Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen, and elsewhere. Some dealt with sterilization of men and women, the treatment of war wounds, ways to counteract chemical weapons, research into new vaccines and drugs, and the survival of harsh conditions.[50]

The most notorious physician was Josef Mengele, an SS officer who became the Auschwitz camp doctor on 30 May 1943.[52] Interested in genetics[52] and keen to experiment on twins, he would pick out subjects from the new arrivals during "selection" on the ramp, shouting "Zwillinge heraus!" (twins step forward!).[53] They would be measured, killed, and dissected. One of Mengele's assistants said in 1946 that he was told to send organs of interest to the directors of the "Anthropological Institute in Berlin-Dahlem". This is thought to refer to Mengele's academic supervisor, Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer , director from October 1942 of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics in Berlin-Dahlem.[54][53][k] Mengele's experiments included placing subjects in pressure chambers, testing drugs on them, freezing them, attempting to change their eye color by injecting chemicals into children's eyes, and amputations and other surgeries.[57]

Origins

Antisemitism and the völkisch movement

Throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, Jews were subjected to antisemitism based on Christian theology, which blamed them for killing Jesus. Even after the Reformation, Catholicism and Lutheranism continued to persecute Jews, accusing them of blood libels and subjecting them to pogroms and expulsions.[58][59] The second half of the 19th century saw the emergence in the German empire and Austria-Hungary of the völkisch movement, which was developed by such thinkers as Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Paul de Lagarde. The movement embraced a pseudo-scientific racism that viewed Jews as a race whose members were locked in mortal combat with the Aryan race for world domination.[60] These ideas became commonplace throughout Germany,[61] with the professional classes adopting an ideology that did not see humans as racial equals with equal hereditary value.[62] Although the völkisch parties had support in elections at first, by 1914 they were no longer influential. This did not mean that antisemitism had disappeared; instead it was incorporated into the platforms of several mainstream political parties.[61]

Germany after World War I, Hitler's world view

The political situation in Germany and elsewhere in Europe after World War I (1914–1918) contributed to the rise of virulent antisemitism. Many Germans did not accept that their country had been defeated, which gave birth to the stab-in-the-back myth. This insinuated that it was disloyal politicians, chiefly Jews and communists, who had orchestrated Germany's surrender. Inflaming the anti-Jewish sentiment was the apparent over-representation of Jews in the leadership of communist revolutionary governments in Europe, such as Ernst Toller, head of a short-lived revolutionary government in Bavaria. This perception contributed to the canard of Jewish Bolshevism.[63]

The economic strains of the Great Depression led some in the German medical establishment to advocate murder (euphemistically called "euthanasia") of the "incurable" mentally and physically disabled as a cost-saving measure to free up funds for the curable.[64] By the time the National Socialist German Workers' Party, or Nazi Party,[l] came to power in 1933, there was already a tendency to seek to save the racially "valuable", while ridding society of the racially "undesirable".[66] The party had originated in 1920[65] as an offshoot of the völkisch movement, and it adopted that movement's antisemitism.[67] Early antisemites in the party included Dietrich Eckart, publisher of the Völkischer Beobachter, the party's newspaper, and Alfred Rosenberg, who wrote antisemitic articles for it in the 1920s. Rosenberg's vision of a secretive Jewish conspiracy ruling the world would influence Hitler's views of Jews by making them the driving force behind communism.[68] The origin and first expression of Hitler's antisemitism remain a matter of debate.[69] Central to his world view was the idea of expansion and lebensraum (living space) for Germany. Open about his hatred of Jews, he subscribed to the common antisemitic stereotypes.[70] From the early 1920s onwards, he compared the Jews to germs and said they should be dealt with in the same way. He viewed Marxism as a Jewish doctrine, said he was fighting against "Jewish Marxism", and believed that Jews had created communism as part of a conspiracy to destroy Germany.[71]

Rise of Nazi Germany

Dictatorship and repression (1933–1939)

With the establishment of the Third Reich in 1933, German leaders proclaimed the rebirth of the Volksgemeinschaft ("people's community").[73] Nazi policies divided the population into two groups: the Volksgenossen ("national comrades") who belonged to the Volksgemeinschaft, and the Gemeinschaftsfremde ("community aliens") who did not. Enemies were divided into three groups: the "racial" or "blood" enemies, such as the Jews and Roma; political opponents of Nazism, such as Marxists, liberals, Christians, and the "reactionaries" viewed as wayward "national comrades"; and moral opponents, such as gay men, the "work-shy", and habitual criminals. The latter two groups were to be sent to concentration camps for "re-education", with the aim of eventual absorption into the Volksgemeinschaft. "Racial" enemies could never belong to the Volksgemeinschaft; they were to be removed from society.[74]

Before and after the March 1933 Reichstag elections, the Nazis intensified their campaign of violence against opponents.[75] They set up concentration camps for extrajudicial imprisonment.[76] One of the first, at Dachau, opened on 9 March 1933.[77] Initially the camp contained mostly Communists and Social Democrats.[78] Other early prisons were consolidated by mid-1934 into purpose-built camps outside the cities, run exclusively by the SS.[79] The initial purpose of the camps was to serve as a deterrent by terrorizing Germans who did not conform.[80]

Throughout the 1930s, the legal, economic, and social rights of Jews were steadily restricted.[81] On 1 April 1933, there was a boycott of Jewish businesses.[82] On 7 April 1933, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service was passed, which excluded Jews and other "non-Aryans" from the civil service.[83] Jews were disbarred from practising law, being editors or proprietors of newspapers, or joining the Journalists' Association. Jews were not allowed to own farms.[84] In Silesia, in March 1933, a group of men entered the courthouse and beat up Jewish lawyers; Friedländer writes that, in Dresden, Jewish lawyers and judges were dragged out of courtrooms during trials.[85] Jewish students were restricted by quotas from attending schools and universities.[83] Jewish businesses were targeted for closure or "Aryanization", the forcible sale to Germans; of the approximately 50,000 Jewish-owned businesses in Germany in 1933, about 7,000 were still Jewish-owned in April 1939. Works by Jewish composers,[86] authors, and artists were excluded from publications, performances, and exhibitions.[87] Jewish doctors were dismissed or urged to resign. The Deutsches Ärzteblatt (a medical journal) reported on 6 April 1933: "Germans are to be treated by Germans only."[88]

Sterilization Law, Aktion T4

The Nazis used the phrase Lebensunwertes Leben (life unworthy of life) in reference to the disabled and mentally ill.[90] On 14 July 1933, the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring (Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses), the Sterilization Law, was passed, allowing for compulsory sterilization.[91][92] The New York Times reported on 21 December that year: "400,000 Germans to be sterilized".[93] There were 84,525 applications from doctors in the first year. The courts reached a decision in 64,499 of those cases; 56,244 were in favor of sterilization.[94] Estimates for the number of involuntary sterilizations during the whole of the Third Reich range from 300,000 to 400,000.[95]

In October 1939 Hitler signed a "euthanasia decree" backdated to 1 September 1939 that authorized Reichsleiter Philipp Bouhler, the chief of Hitler's Chancellery, and Karl Brandt, Hitler's personal physician, to carry out a program of involuntary "euthanasia"; after the war this program was named Aktion T4.[96] It was named after Tiergartenstraße 4, the address of a villa in the Berlin borough of Tiergarten, where the various organizations involved were headquartered.[97] T4 was mainly directed at adults, but the "euthanasia" of children was also carried out.[98] Between 1939 and 1941, 80,000 to 100,000 mentally ill adults in institutions were killed, as were 5,000 children and 1,000 Jews, also in institutions. In addition there were specialized killing centres, where the deaths were estimated at 20,000, according to Georg Renno, the deputy director of Schloss Hartheim, one of the "euthanasia" centers, or 400,000, according to Frank Zeireis, the commandant of the Mauthausen concentration camp.[99] Overall, the number of mentally and physically handicapped murdered was about 150,000.[100]

Although not ordered to take part, psychiatrists and many psychiatric institutions were involved in the planning and carrying out of Aktion T4 at every stage.[101] After protests from the German Catholic and Protestant churches, Hitler ordered the cancellation of the T4 program in August 1941,[102] although the disabled and mentally ill continued to be killed until the end of the war.[100] The medical community regularly received bodies and body parts for research. Eberhard Karl University received 1,077 bodies from executions between 1933 and 1945. The neuroscientist Julius Hallervorden received 697 brains from one hospital between 1940 and 1944: "I accepted these brains of course. Where they came from and how they came to me was really none of my business."[103]

Nuremberg Laws, Jewish emigration

On 15 September 1935, the Reichstag passed the Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, known as the Nuremberg Laws. The former said that only those of "German or kindred blood" could be citizens. Anyone with three or more Jewish grandparents was classified as a Jew.[104] The second law said: "Marriages between Jews and subjects of the state of German or related blood are forbidden." Sexual relationships between them were also criminalized; Jews were not allowed to employ German women under the age of 45 in their homes.[105] The laws referred to Jews but applied equally to the Roma and black Germans.[104]

Nazi racial policy aimed at forcing Jews to emigrate.[106] Fifty thousand German Jews had left Germany by the end of 1934,[107] and by the end of 1938, approximately half the German Jewish population had left the country.[106] Among the prominent Jews who left was the conductor Bruno Walter, who fled after being told that the hall of the Berlin Philharmonic would be burned down if he conducted a concert there.[108] Albert Einstein, who was abroad when Hitler came to power, never returned to Germany. He was expelled from the Kaiser Wilhelm Society and the Prussian Academy of Sciences, and his citizenship was revoked.[109] Other Jewish scientists, including Gustav Hertz, lost their teaching positions and left the country.[110] In March 1938 Germany annexed Austria. Austrian Nazis broke into Jewish shops, stole from Jewish homes and businesses, and forced Jews to perform humiliating acts such as scrubbing the streets or cleaning toilets.[111] Jewish businesses were "Aryanized", and all the legal restrictions on Jews in Germany were imposed.[112] In August, Adolf Eichmann was put in charge of the Central Agency for Jewish Emigration. About 100,000 Austrian Jews had left the country by May 1939, including Sigmund Freud and his family.[113]

The Évian Conference was held in July 1938 by 32 countries as an attempt to help the increased refugees from Germany, but aside from establishing the largely ineffectual Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, little was accomplished and most countries participating did not increase the number of refugees they would accept.[114]

Kristallnacht

On 7 November 1938, Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish Jew, shot the German diplomat Ernst vom Rath in the German Embassy in Paris, in retaliation for the expulsion of his parents and siblings from Germany.[115][m] When vom Rath died on 9 November, the government used his death as a pretext to instigate a pogrom against the Jews throughout the Third Reich. The government claimed it was spontaneous, but in fact it had been ordered and planned by Hitler and Goebbels, although with no clear goals, according to David Cesarani; the result, he writes, was "murder, rape, looting, destruction of property, and terror on an unprecedented scale".[117][118]

Known as Kristallnacht (or "Night of Broken Glass"), the attacks were partly carried out by the SS and SA,[119] but ordinary Germans joined in; in some areas, the violence began before the SS or SA arrived.[120] Over 7,500 Jewish shops (out of 9,000) were looted and attacked, and over 1,000 synagogues damaged or destroyed. Groups of Jews were forced by the crowd to watch their synagogues burn; in Bensheim they were forced to dance around it, and in Laupheim to kneel before it.[121] At least 90 Jews died. The damage was estimated at 39 million Reichmarks.[122] Cesarani writes that "[t]he extent of the desolation stunned the population and rocked the regime."[117] Thirty-thousand Jews were sent to the Dachau, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen concentration camps.[123] Many were released within weeks; by early 1939, 2,000 remained in the camps.[124] German Jewry was held collectively responsible for restitution of the damage; they also had to pay an "atonement tax" of over a billion Reichmarks. Insurance payments for damage to their property were confiscated by the government. A decree on 12 November 1938 barred Jews from most of the remaining occupations they had been allowed to hold.[125] Kristallnacht marked the end of any sort of public Jewish activity and culture, and Jews stepped up their efforts to leave the country.[126]

Territorial solution and resettlement

Before World War II, Germany considered mass deportation from Europe of German, and later European, Jewry.[127] Among the areas considered for possible resettlement were British Palestine[128] and French Madagascar.[129] After the war began, German leaders considered deporting Europe's Jews to Siberia.[130][131] Palestine was the only location to which any German relocation plan produced results, via the Haavara Agreement between the Zionist Federation of Germany and the German government.[132] This resulted in the transfer of about 60,000 German Jews and $100 million from Germany to Palestine, but it ended with the outbreak of World War II.[133] In May 1940 Madagascar became the focus of new deportation efforts[129] because it had unfavorable living conditions that would hasten deaths.[134] Several German leaders had discussed the idea in 1938, and Adolf Eichmann's office was ordered to carry out resettlement planning, but no evidence of planning exists until after the fall of France in June 1940.[135] But the inability to defeat Britain prevented the movement of Jews across the seas,[136] and the end of the Madagascar Plan was announced on 10 February 1942.[137]

World War II

German-occupied Poland

When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, it gained control of about 2 million Jews in the occupied territory. The rest of Poland was occupied by the Soviet Union, which had control of the rest of Poland's pre-war population of 3.3–3.5 million Jews.[138] German plans for Poland included expelling gentile Poles from large areas, confining Jews, and settling Germans on the emptied lands. To help the process along, Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Security Main Office, ordered that the "leadership class" in Poland be killed and the Jews expelled from the Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany.[139]

The Germans initiated a policy of sending Jews from all territories they had recently annexed (Austria, Czechoslovakia, and western Poland) to the central section of Poland, which they called the General Government. There, the Jews were concentrated in ghettos in major cities,[140] chosen for their railway lines to facilitate later deportation.[141] Food supplies were restricted, public hygiene was difficult, and the inhabitants were often subjected to forced labor.[142] In the work camps and ghettos, at least half a million Jews died of starvation, disease, and poor living conditions.[143] Jeremy Black writes that the ghettos were not intended, in 1939, as a step towards the extermination of the Jews. Instead, they were viewed as part of a policy of creating a territorial reservation to contain them.[144][n]

Other occupied countries

Germany invaded Norway in April 1940. The country was completely occupied by June.[154] There were about 1,800 Jews in Norway, persecuted by the Norwegian Nazis. In late 1940, the Jews were banned from some occupations, and in 1941, all Jews had to register their property with the government.[155] Also in 1940, Germany invaded Denmark, [154] overrunning the country so quickly that there was no chance of organizing resistance. Consequently, the Danish government stayed in power and the Germans found it easier to work through it. Because of this, few measures were taken against the Danish Jews before 1942.[156]

The Germans invaded the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, and France in May 1940. In the Netherlands, the Germans installed Arthur Seyss-Inquart as Reichskommissar, who quickly began to persecute the approximately 140,000 Dutch Jews. Jews were forced out of their jobs and had to register with the government. Non-Jewish Dutch citizens protested these measures and in February 1941, staged a strike that was quickly crushed.[157] After Belgium's surrender at the end of May 1940, it was ruled by a German military governor, Alexander von Falkenhausen, who enacted anti-Jewish measures against the country's approximately 90,000 Jews, many of whom were refugees from Germany or Eastern Europe.[158] France had approximately 300,000 Jews, divided between the German-occupied northern part of France, and the unoccupied collaborationist southern areas under the Vichy regime. The occupied regions were under the control of a military governor, and there, anti-Jewish measures were not enacted as quickly as they were in the Vichy-controlled areas.[159] In July 1940, the Jews in the parts of Alsace-Lorraine that had been annexed to Germany were expelled into Vichy France.[160]

Yugoslavia and Greece were invaded in April 1941, and both countries surrendered before the end of the month. Germany and Italy divided Greece into occupation zones but did not eliminate it as a country. Yugoslavia was dismembered, with regions in the north being annexed by Germany, and regions along the coast made part of Italy. The rest of the country was divided into a puppet state of Croatia, which was nominally an ally of Germany, and Serbia, which was governed by a combination of military and police administrators. There were approximately 80,000 Jews in Yugoslavia when it was invaded. The ruling party in Croatia, the Ustashe, not only killed Jews but murdered and expelled Orthodox Christian Serbs and Muslims.[161]. By 1945, between 300,000 to 500,000 Serbs were killed at the hands of the Ustashe.[162][163] Anti-Serb sentiment and Catholic fanaticism motivated the murder and expulsion of the Serbs from the puppet state of Croatia and in many cases, Serbs were killed after refusing to convert to Catholicism.[164] Serbia was declared free of Jews in August 1942.[165]

Germany's allies

Italy introduced some antisemitic measures, but there was less antisemitism there than in Germany, and Italian-occupied countries were generally safer for Jews than German-occupied territories. In some areas, the Italian authorities even tried to protect Jews, such as in the Croatian areas of the Balkans. But while Italian forces in Russia were not as vicious towards Jews as the Germans, they did not try to stop German atrocities either. There were no deportations of Italian Jews to Germany while Italy remained an ally.[166] Several forced labor camps for Jews were established in Italian-controlled Libya. Almost 2,600 Libyan Jews were sent to camps, where 562 died.[167]

Vichy France's government implemented anti-Jewish measures in French Algeria and the two French Protectorates of Tunisia and Morocco.[168] Tunisia had 85,000 Jews when the Germans and Italians arrived in November 1942. An estimated 5,000 Jews were subjected to forced labor.[169] Finland was pressured in 1942 to hand over its 150–200 non-Finnish Jews to Germany. After opposition from the government and public, eight non-Finnish Jews were deported in late 1942; only one survived the war.[170] Japan had little antisemitism in its society and did not persecute Jews in most of the territories it controlled. Jews in Shanghai were confined, but despite German pressure they were not killed.[171]

Romania implemented anti-Jewish measures in May and June 1940 as part of its efforts towards an alliance with Germany. Jews were forced from government service, pogroms were carried out, and by March 1941 all Jews had lost their jobs and had their property confiscated.[172] After Romania joined the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, at least 13,266 Jews were killed in the Iași pogrom,[173] and Romanian troops carried out massacres in Romanian-controlled territory, including the Odessa massacre of 20,000 Jews in Odessa in late 1941. Romania also set up concentration camps under its control in Transnistria, where 154,000–170,000 Jews were deported from 1941 to 1943.[172]

Anti-Jewish measures were introduced in Slovakia, which would later deport its Jews to German concentration and extermination camps.[174] Bulgaria introduced anti-Jewish measures in 1940 and 1941, including the requirement to wear a yellow star, the banning of mixed marriages, and the loss of property. Bulgaria annexed Thrace and Macedonia, and in February 1943 agreed to deport 20,000 Jews to Treblinka. All 11,000 Jews from the annexed territories were sent to their deaths, and plans were made to deport an additional 6,000–8,000 Bulgarian Jews from Sofia to meet the quota.[175] When the plans became public, the Orthodox Church and many Bulgarians protested, and King Boris III canceled the deportation of Jews native to Bulgaria.[176] Instead, they were expelled to the interior, pending further decision.[175] Although Hungary expelled Jews who were not citizens from its newly annexed lands in 1941, it did not deport most of its Jews[177] until the German invasion of Hungary in March 1944. Between 15 May and 9 July 1944, 440,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz.[178] In Budapest, nearly 80,000 Jews were killed by the Hungarian Arrow Cross battalions in late 1944.[179]

Concentration and labor camps

The Third Reich first used concentration camps as places of unlawful incarceration of political opponents and other "enemies of the state". Large numbers of Jews were not sent there until after Kristallnacht in November 1938.[181] Although death rates were high, the camps were not designed as killing centers.[182] After war broke out in 1939, new camps were established, some outside Germany in occupied Europe.[183] In January 1945, the SS reports had over 700,000 prisoners in their control, of which close to half had died by the end of May 1945 according to most historians.[184] Most wartime prisoners of the camps were not Germans but belonged to countries under German occupation.[185] It is estimated that the Germans established over 42,000 detention sites throughout Europe, including ghettos, concentration camps, prisoner-of-war camps, work camps, and extermination camps.[186]

After 1942, the economic functions of the camps, previously secondary to their penal and terror functions, came to the fore. Forced labor of camp prisoners became commonplace.[181] The guards became much more brutal, and the death rate increased as the guards not only beat and starved prisoners, but killed them more frequently.[185] Vernichtung durch Arbeit ("extermination through labor") was a policy—camp inmates would literally be worked to death, or to physical exhaustion, at which point they would be gassed or shot.[187] The Germans estimated the average prisoner's lifespan in a concentration camp at three months, due to lack of food and clothing, constant epidemics, and frequent punishments for the most minor transgressions.[188] The shifts were long and often involved exposure to dangerous materials.[189]

Transportation between camps was often carried out in freight cars with prisoners packed tightly. Long delays would take place; prisoners might be confined in the cars on sidings for days.[190] In mid-1942 work camps began requiring newly arrived prisoners to be placed in quarantine for four weeks.[191] Prisoners wore colored triangles on their uniforms, the color of the triangle denoting the reason for their incarceration. Red signified a political prisoner, Jehovah's Witnesses had purple triangles, "asocials" and criminals wore black and green. Badges were pink for gay men and yellow for Jews.[192] Jews had a second yellow triangle worn with their original triangle, the two forming a six-pointed star.[193][194] In Auschwitz, prisoners were tattooed with an identification number on arrival.[195]

Ghettos

After invading Poland, the Germans established ghettos in the incorporated territories and General Government to confine Jews.[140] The ghettos were formed and closed off from the outside world at different times and for different reasons.[196][197] For example, the Łódź ghetto was closed in April 1940,[140] to force the Jews inside to give up money and valuables;[198] the Warsaw ghetto was closed for health considerations (for the people outside, not inside, the ghetto),[199] but this did not happen until November 1940;[140] and the Kraków ghetto was not established until March 1941.[200] The Warsaw Ghetto contained 380,000 people[140] and was the largest ghetto in Poland; the Łódź Ghetto was the second largest,[201] holding between 160,000[202] to 223,000.[203] Because of the long drawn-out process of establishing ghettos, it is unlikely that they were originally considered part of a systematic attempt to eliminate Jews completely.[204]

The Germans required each ghetto to be run by a Judenrat, or Jewish council.[205] Councils were responsible for a ghetto's day-to-day operations, including distributing food, water, heat, medical care, and shelter. The Germans also required councils to confiscate property, organize forced labor, and, finally, facilitate deportations to extermination camps.[206] The councils' basic strategy was one of trying to minimize losses, by cooperating with German authorities, bribing officials, and petitioning for better conditions or clemency.[207]

Eventually, the Germans ordered the councils to compile lists of names of deportees to be sent for "resettlement".[208] Although most ghetto councils complied with these orders,[209] many councils tried to send the least useful workers or those unable to work.[210] Leaders who refused these orders were shot. Some individuals or even complete councils committed suicide rather than cooperate with the deportations.[211] Others, like Chaim Rumkowski, who became the "dedicated autocrat" of Łódź,[212] argued that their responsibility was to save the Jews who could be saved and that therefore others had to be sacrificed.[213] The councils' actions in facilitating Germany's persecution and murder of ghetto inhabitants was important to the Germans.[214] When cooperation crumbled, as happened in the Warsaw ghetto after the Jewish Combat Organisation displaced the council's authority, the Germans lost control.[215]

Ghettos were intended to be temporary until the Jews were deported to other locations, which never happened. Instead, the inhabitants were sent to extermination camps. The ghettos were, in effect, immensely crowded prisons serving as instruments of "slow, passive murder."[216] Though the Warsaw Ghetto contained 30% of Warsaw's population, it occupied only 2.5% of the city's area, averaging over 9 people per room.[217] Between 1940 and 1942, starvation and disease, especially typhoid, killed many in the ghettos.[218] Over 43,000 Warsaw ghetto residents, or one in ten of the total population, died in 1941;[219] in Theresienstadt, more than half the residents died in 1942.[216]

Himmler ordered the closing of ghettos in Poland in mid-July 1942, with most inhabitants going to extermination camps. Those Jews needed for war production would be confined at concentration camps.[220] The deportations from the Warsaw Ghetto began on 22 July; over the almost two months of the Aktion, until 12 September, the Warsaw ghetto went from approximately 350,000 inhabitants to about 65,000. Those deported were transported in freight trains to the Treblinka extermination camp.[221] Similar deportations happened in other ghettos, with many ghettos totally emptied.[222]

The first ghetto uprisings occurred in mid-1942 in small community ghettos.[223] Although there were armed resistance attempts in both the larger and smaller ghettos in 1943, in every case they failed against the overwhelming German military force, and the remaining Jews were either killed or deported to the death camps.[224]

Pogroms

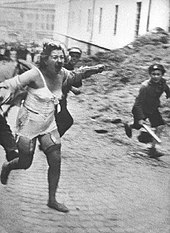

A number of deadly pogroms occurred during the Holocaust.[225] The Germans encouraged some, and others were spontaneous.[226] Some, such as the Iaşi pogrom, were in lands controlled by Germany's allies.[227] In the series of Lviv pogroms committed in occupied Poland,[o] some 6,000 Polish Jews were murdered in the streets in July 1941, on top of 3,000 arrests and mass shootings by Einsatzgruppe C.[229] During the Jedwabne pogrom of July 1941, in the presence of the German officers, several hundred Jews were murdered by some local Poles, with some being burned alive in a barn.[230][p]

Death squads

Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941.[231] German propaganda portrayed the war against the Soviet Union as both an ideological war between German National Socialism and Jewish Bolshevism and a racial war between the Germans and the Jewish, Romani and Slavic Untermenschen ("sub-humans").[232]

Local populations in some occupied Soviet territories actively participated in the killings of Jews and others. Besides participating in killings and pogroms, they helped identify Jews for persecution and rounded up Jews for German actions.[233] German involvement ranged from active instigation and involvement to more generalized guidance.[234] In Lithuania, Latvia, and western Ukraine locals were deeply involved in the murder of Jews from the beginning of the German occupation. Some of these Latvian and Lithuanian units also participated in the murder of Jews in Belarus. In the south, Ukrainians killed about 24,000 Jews and some went to Poland to serve as concentration and death-camp guards.[233] Military units from some countries allied to Germany also killed Jews. Romanian units were given orders to exterminate and wipe out Jews in areas they controlled.[235] Ustaše militia in Croatia persecuted and murdered Jews, among others.[165] Many of the killings were carried out in public, a change from previous practice.[236]

The mass killings of Jews in the occupied Soviet territories were assigned to four SS formations called Einsatzgruppen ("task groups"), which were under Heydrich's overall command. Similar formations had been used to a limited extent in Poland in 1939, but the ones operating in the Soviet territories were much larger.[237] The Einsatzgruppen's commanders were ordinary citizens: the great majority were professionals and most were intellectuals.[238] By the winter of 1941–1942, the four Einsatzgruppen and their helpers had killed almost 500,000 people.[239]

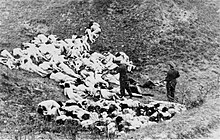

The largest massacre of Jews by the mobile killing squads in the Soviet Union was at a ravine called Babi Yar outside Kiev,[240] where 33,771 Jews were killed in a single operation on 29–30 September 1941.[241][q] A mixture of SS and Security Police, assisted by Ukrainian police, carried out the killings.[243] Although they did not actively participate in the killings, men of the German 6th Army helped round up the Jews of Kiev and transport them to be shot.[244] By the end of the war, around two million are thought to have been victims of the Einsatzgruppen and their helpers in the local population and the German Army. Of those, about 1.3 million were Jews and up to a quarter of a million Roma.[245]

Gas vans

As the mass shootings continued in Russia, the Germans began to search for new methods of mass murder. This was driven by a need to have a more efficient method than simply shooting millions of victims. Himmler also feared that the mass shootings were causing psychological problems in the SS. His concerns were shared by his subordinates in the field.[246] In December 1939 and January 1940, another method besides shooting was tried. Experimental gas vans equipped with gas cylinders and a sealed compartment were used to kill the disabled and mentally-ill in occupied Poland.[247] Similar vans, but using the exhaust fumes rather than bottled gas, were introduced to the Chełmno extermination camp in December 1941,[248] and some were used in the occupied Soviet Union, for example in smaller clearing actions in the Minsk ghetto.[249] They also were used for murder in Yugoslavia.[250]

Final Solution

Wannsee Conference

SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Main Security Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA), convened what became known as the Wannsee Conference on 20 January 1942 at a villa, am Grossen Wannsee No. 56/58, in Berlin's Wannsee suburb.[251][252][253] The meeting had been scheduled for 9 December 1941, and invitations had been sent on 29 November, but it had been postponed.[254] Christian Gerlach argues that Hitler announced his decision to annihilate the Jews on or around 12 December 1941, probably on 12 December during a speech to Nazi Party leaders. This was one day after he declared war on the United States and five days after the attack on Pearl Harbour by Japan. Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, noted of Hitler's speech: "He warned the Jews that if they were to cause another world war, it would lead to their destruction. ... Now the world war has come. The destruction of the Jews must be its necessary consequence."[255][r]

The 15 men present at Wannsee included Adolf Eichmann (head of Jewish affairs for the RSHA and the man who organized the deportation of Jews), Heinrich Müller (head of the Gestapo), and other party leaders and department heads.[252] Thirty copies of the minutes were made. Copy no. 16 was found by American prosecutors in March 1947 in a German Foreign Office folder.[257] Written by Eichmann and stamped "Top Secret", the minutes were written in "euphemistic language" on Heydrich's instructions, according to Eichmann's later testimony.[258] The conference had several purposes. Discussing plans for a "final solution to the Jewish question" ("Endlösung der Judenfrage"), and a "final solution to the Jewish question in Europe" ("Endlösung der europäischen Judenfrage"),[252] it was intended to share information and responsibility, coordinate efforts and policies ("Parallelisierung der Linienführung"), and ensure that authority rested with Heydrich. There was also discussion about whether to include the German Mischlinge (half-Jews).[259] Heydrich told the meeting: "Another possible solution of the problem has now taken the place of emigration, i.e. the evacuation of the Jews to the East, provided that the Fuehrer gives the appropriate approval in advance."[252] He continued:

Under proper guidance, in the course of the final solution the Jews are to be allocated for appropriate labor in the East. Able-bodied Jews, separated according to sex, will be taken in large work columns to these areas for work on roads, in the course of which action doubtless a large portion will be eliminated by natural causes.

The possible final remnant will, since it will undoubtedly consist of the most resistant portion, have to be treated accordingly because it is the product of natural selection and would, if released, act as the seed of a new Jewish revival (see the experience of history.) In the course of the practical execution of the final solution, Europe will be combed through from west to east. Germany proper, including the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, will have to be handled first due to the housing problem and additional social and political necessities. The evacuated Jews will first be sent, group by group, to so-called transit ghettos, from which they will be transported to the East.[252]

These evacuations were regarded as provisional or "temporary solutions" ("Ausweichmöglichkeiten").[260][s] The final solution would encompass the 11 million Jews living not only in territories controlled by Germany, but elsewhere in Europe and adjacent territories, such as Britain, Ireland, Switzerland, Turkey, Sweden, Portugal, Spain, and Hungary, "dependent on military developments".[260] There was little doubt what the final solution was, writes Peter Longerich: "the Jews were to be annihilated by a combination of forced labour and mass murder".[262]

Extermination camps, gas chambers

Killing on a mass scale using gas chambers or gas vans was the main difference between the extermination and concentration camps.[263] From the end of 1941, the Germans built six extermination camps in occupied Poland: Auschwitz II-Birkenau, Majdanek, Chełmno, and the three Operation Reinhard camps at Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka II.[40][264][265] Maly Trostenets, a concentration camp in the Reichskommissariat Ostland, became a killing centre in 1942.[40] Gerlach writes that over three million Jews were murdered in 1942, the year that "marked the peak" of the mass murder of Jews.[266] At least 1.4 million of these were in the General Government area of Poland.[267]

Using gas vans, Chełmno had its roots in the Aktion T4 euthanasia program.[268] Majdanek began as a POW camp, but in August 1942 it had gas chambers installed.[269] A few other camps are occasionally named as extermination camps, but there is no scholarly agreement on the additional camps; commonly mentioned are Mauthausen in Austria[270] and Stutthof.[271] There may also have been plans for camps at Mogilev and Lvov.[272]

Victims usually arrived at the camps by train.[273] Almost all arrivals at the Operation Reinhard camps of Treblinka, Sobibór, and Bełżec were sent directly to the gas chambers,[274] with individuals occasionally selected to replace dead workers.[275][276] At Auschwitz, camp officials usually subjected individuals to selections;[277] about 25%[278] of the new arrivals were selected to work.[277] Those selected for death at all camps were told to undress and hand their valuables to camp workers.[279] They were then herded naked into the gas chambers. To prevent panic, they were told the gas chambers were showers or delousing chambers.[280] The procedure at Chełmno was slightly different. Victims there were placed in a mobile gas van and asphyxiated, while being driven to prepared burial pits in the nearby forests. There the corpses were unloaded and buried.[281]

| Camp name | Killed | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Auschwitz II | 1,100,000 | [282] |

| Bełżec | 600,000 | [283] |

| Chełmno | 320,000 | [284] |

| Majdanek | 78,000 | [285] |

| Maly Trostinets | 65,000 | [286] |

| Sobibór | 250,000 | [287] |

| Treblinka | 870,000 | [288] |

At Auschwitz, after the chambers were filled, the doors were shut and pellets of Zyklon-B were dropped into the chambers through vents,[289] releasing toxic prussic acid, or hydrogen cyanide.[290] Those inside died within 20 minutes; the speed of death depended on how close the inmate was standing to a gas vent, according to the commandant Rudolf Höss, who estimated that about one-third of the victims died immediately.[291] Johann Kremer, an SS doctor who oversaw the gassings, testified that: "Shouting and screaming of the victims could be heard through the opening and it was clear that they fought for their lives."[292] The gas was then pumped out, the bodies were removed, gold fillings in their teeth were extracted, and women's hair was cut.[293] The work was done by the Sonderkommando, work groups of mostly Jewish prisoners.[294] At Auschwitz, the bodies were at first buried in deep pits and covered with lime, but between September and November 1942, on the orders of Himmler, they were dug up and burned. In early 1943, new gas chambers and crematoria were built to accommodate the numbers.[295]

At the three Reinhard camps the victims were killed by the exhaust fumes of stationary diesel engines.[274] Gold fillings were pulled from the corpses before burial, but the women's hair was cut before death. At Treblinka, to calm the victims, the arrival platform was made to look like a train station, complete with fake clock.[296] Majdanek used Zyklon-B gas in its gas chambers.[297] In contrast to Auschwitz, the three Reinhard camps were quite small.[298] Most of the victims at these camps were buried in pits at first. Sobibór and Bełżec began exhuming and burning bodies in late 1942, to hide the evidence, as did Treblinka in March 1943. The bodies were burned in open fireplaces and the remaining bones crushed into powder.[299]

Jewish resistance

Peter Longerich observes that in ghettos in Poland by the end of 1942, "there was practically no resistance".[300] Raul Hilberg accounts for this compliant attitude by evoking the history of Jewish persecution: as had been the case before, appealing to their oppressors and complying with orders might avoid inflaming the situation until the onslaught abated.[301][t] Timothy Snyder notes that it was only during the three months after the deportations of July–September 1942 that agreement on the need for armed resistance was reached.[304][305]

Several groups were formed, such as the Jewish Combat Organization in the Warsaw Ghetto and the United Partisan Organization in Vilna.[306] Over 100 revolts and uprisings occurred in at least 19 ghettos and elsewhere in Eastern Europe. The best known is the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943, when around 1,000 poorly armed Jewish fighters held the SS at bay for four weeks.[307][v] During a revolt in Treblinka on 2 August 1943, inmates killed five or six guards and set fire to camp buildings; several managed to escape.[312][313]

In the Białystok Ghetto on 16 August 1943, Jewish insurgents revolted when the Germans announced mass deportations. The fighting lasted five days.[314] On 14 October 1943, Jews in Sobibór, including Jewish-Soviet prisoners of war, attempted an escape,[315] killing 11 SS officers and a couple of Ukrainian camp guards.[316] Around 300 prisoners escaped, but 100 were recaptured and shot.[317][315] In October 1944, Jewish members of the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz attacked their guards and blew up Crematorium IV with explosives that had been smuggled in. Three German guards were killed, one of whom was stuffed into an oven. The Sonderkommando attempted a mass breakout, but all were killed.[318]

Estimates of Jewish participation in partisan units throughout Europe range from 20,000 to 100,000.[319] In the occupied Polish and Soviet territories, thousands of Jews fled into the swamps or forests and joined the partisans,[320] although the partisan movements did not always welcome them.[321] An estimated 20,000 to 30,000 joined the Soviet partisan movement.[322] One of the famous Jewish groups was the Bielski partisans in Belarus, led by the Bielski brothers.[320] Jews also joined Polish forces, including the Home Army. According to Timothy Snyder, "more Jews fought in the Warsaw Uprising of August 1944 than in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of April 1943".[323][w]

Flow of information about the mass murder

The Polish government-in-exile in London learned about the extermination camps from the Polish leadership in Warsaw, who from 1940 "received a continual flow of information about Auschwitz", according to historian Michael Fleming.[329] On 6 January 1942, the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, Vyacheslav Molotov, sent out diplomatic notes about German atrocities. The notes were based on reports about bodies surfacing from poorly covered graves in pits and quarries, as well as mass graves found in areas the Red Army had liberated, and on witness reports from German-occupied areas.[330]

Escapes from the camps were few, but not unknown.[331] In February 1942, Szlama Ber Winer escaped from the Chełmno concentration camp in Poland, and passed detailed information about it to the Oneg Shabbat group in the Warsaw Ghetto. His report, known by his pseudonym as the Grojanowski Report, had reached London by June 1942.[284][332] Also in 1942, Jan Karski reported to the Allies on the plight of Jews after being smuggled into the Warsaw Ghetto twice.[333][334][x] On 27 April 1942, Vyacheslav Molotov sent out another note about atrocities.[330] In late July or early August 1942, Polish leaders learned about the mass killings taking place inside Auschwitz. The Polish Interior Ministry prepared a report, Sprawozdanie 6/42,[329][336] which said at the end:

There are different methods of execution. People are shot by firing squads, killed by an "air hammer", and poisoned by gas in special gas chambers. Prisoners condemned to death by the Gestapo are murdered by the first two methods. The third method, the gas chamber, is employed for those who are ill or incapable of work and those who have been brought in transports especially for the purpose/Soviet prisoners of war, and, recently Jews.[329]

The report was sent to Polish officials in London by courier and had reached them by 12 November 1942, when it was translated into English and added to another report, "Report on Conditions in Poland". Dated 27 November, this was forwarded to the Polish Embassy in the United States.[337] On 10 December 1942, the Polish Foreign Affairs Minister, Edward Raczyński, addressed the fledgling United Nations on the killings; the address was distributed with the title The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland. He told them about the use of poison gas; about Treblinka, Bełżec and Sobibor; that the Polish underground had referred to them as extermination camps; and that tens of thousands of Jews had been killed in Bełżec in March and April 1942.[338] One in three Jews in Poland were already dead, he estimated, from a population of 3,130,000.[339] Raczyński's address was covered by the New York Times and The Times of London. Winston Churchill received it, and Anthony Eden presented it to the British cabinet. On 17 December 1942, 11 Allies issued the Joint Declaration by Members of the United Nations condemning the "bestial policy of cold-blooded extermination".[340][341]

The British and American governments were reluctant to publicize the intelligence they had received. Although the information was felt to be correct, the stories were so extreme that they feared the public would discount them as exaggerations and that the credibility of both governments would be undermined.[342] A BBC Hungarian Service memo, written by Carlile Macartney, a BBC broadcaster and senior Foreign Office adviser on Hungary, stated in 1942: "We shouldn't mention the Jews at all." The British government's view was that the Hungarian people's antisemitism would make them distrust the Allies if Allied broadcasts focused on the Jews.[343] The US government also hesitated to emphasize the atrocities for fear of turning the war into a war about the Jews. Antisemitism and isolationism were common in the US before its entry into the war, and the government wanted to avoid too great a focus on Jewish suffering to keep isolationism from gaining ground.[344]

Climax, Holocaust in Hungary

Most of the Jewish ghettos of General Government were liquidated in 1942–1943, and their populations shipped to the camps for extermination.[345][346][y] About 42,000 Jews were shot during the Operation Harvest Festival on 3–4 November 1943.[347] At the same time, rail shipments arrived regularly from western and southern Europe at the extermination camps.[348] Few Jews were shipped from the occupied Soviet territories to the camps: the killing of Jews in this zone was mostly left in the hands of the SS, aided by locally recruited auxiliaries.[349][z]

Shipments of Jews to the camps had priority over anything but the army's needs on the German railways, and continued even in the face of the increasingly dire military situation at the end of 1942.[351] Army leaders and economic managers complained about this diversion of resources and the killing of skilled Jewish workers,[352] but Nazi leaders rated ideological imperatives above economic considerations.[353]

By 1943 it was evident to the armed forces leadership that Germany was losing the war.[354] The mass murder continued nevertheless, reaching a "frenetic" pace in 1944.[355] Auschwitz was gassing up to 6,000 Jews a day by spring that year.[356] On 19 March 1944, Hitler ordered the military occupation of Hungary and dispatched Eichmann to Budapest to supervise the deportation of the country's Jews.[357] From 22 March, Jews were required to wear the yellow star; forbidden from owning cars, bicycles, radios or telephones; then forced into ghettos.[358] From 15 May to 9 July, 440,000 Jews were deported from Hungary to Auschwitz-Birkenau, almost all to the gas chambers.[aa] A month before the deportations began, Eichmann offered to exchange one million Jews for 10,000 trucks and other goods from the Allies, the so-called "blood for goods" proposal.[361] The Times called it "a new level of fantasy and self-deception".[362]

Death marches

By mid-1944 those Jewish communities within easy reach of the Nazi regime had been largely exterminated,[363] in proportions ranging from about 25 percent in France[364] to more than 90 percent in Poland.[365] On 5 May Himmler claimed in a speech that "the Jewish question has in general been solved in Germany and in the countries occupied by Germany".[366]

As the Soviet armed forces advanced, the camps in eastern Poland were closed down, with surviving inmates shipped to camps closer to Germany.[367] Efforts were made to conceal evidence of what had happened. The gas chambers were dismantled, the crematoria dynamited, and the mass graves dug up and the corpses cremated.[368] Local commanders continued to kill Jews, and to shuttle them from camp to camp by forced "death marches".[369] Already sick after months or years of violence and starvation, some were marched to train stations and transported for days at a time without food or shelter in open freight cars, then forced to march again at the other end to the new camp. Others were marched the entire distance to the new camp. Those who lagged behind or fell were shot. Around 250,000 Jews died during these marches.[370]

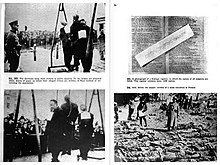

Liberation

The first major camp to be encountered by Allied troops, Majdanek, was discovered by the advancing Soviets on 25 July 1944.[371] Treblinka, Sobibór, and Bełżec were never liberated, but were destroyed by the Germans in 1943.[372] Auschwitz was liberated, also by the Soviets, on 27 January 1945;[373] Buchenwald by the Americans on 11 April;[374] Bergen-Belsen by the British on 15 April;[375] Dachau by the Americans on 29 April;[376] Ravensbrück by the Soviets on 30 April;[377] and Mauthausen by the Americans on 5 May.[378] The Red Cross took control of Theresienstadt on 4 May, days before the Soviets arrived.[379][380]

The Soviets found 7,600 inmates in Auschwitz.[381] Some 60,000 prisoners were discovered at Bergen-Belsen by the British 11th Armoured Division;[382] 13,000 corpses lay unburied, and another 10,000 people died from typhus or malnutrition over the following weeks.[383] The BBC's war correspondent, Richard Dimbleby, described the scenes that greeted him and the British Army at Belsen, in a report so graphic that the BBC declined to broadcast it for four days and did so, on 19 April, only after Dimbleby had threatened to resign:[384]

Here over an acre of ground lay dead and dying people. You could not see which was which. ... The living lay with their heads against the corpses and around them moved the awful, ghostly procession of emaciated, aimless people, with nothing to do and with no hope of life, unable to move out of your way, unable to look at the terrible sights around them ... Babies had been born here, tiny wizened things that could not live. ... A mother, driven mad, screamed at a British sentry to give her milk for her child, and thrust the tiny mite into his arms. ... He opened the bundle and found the baby had been dead for days. This day at Belsen was the most horrible of my life.

— Richard Dimbleby, 15 April 1945[385]

Victims and death toll

Overview

| Victims | Estimated Killed | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Jews | 5.9 million | Hayes[386] |

| Soviet civilians (including 1.3 million Soviet Jews) | 7 million | USHMM[387] |

| Soviet POWs | 2–3 million | Berenbaum[388] |

| Ethnic Poles | 1.8–1.9 million | Piotrowski[389] |

| Roma | 196,000–220,000 | USHMM[387] |

| Disabled | Up to 250,000 | USHMM[387] |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 1,400–2,500 | USHMM[390] Milton[391] |

| Gay men | Unknown | USHMM[392] |

Most historians define the Holocaust as the German genocide of the European Jews, carried out between 1941 and 1945.[a] Donald Niewyk and Francis Nicosia, writing in The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust (2000), favour a definition that focuses on the Jews, Roma and handicapped (Aktion T4 victims), because they were targets of Nazi efforts to destroy entire groups based on heredity.[5]

The broadest definition of the Holocaust would include ethnic Poles, Soviet citizens, Soviet prisoners of war, gay men, and political opponents, and would raise the death toll to 17 million.[393] A research project started in 2000, led by Geoffrey Megargee and Martin Dean for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, estimated in 2013 that 15–20 million people had died or been imprisoned in the sites they have identified to date.[394]

Jews

| Country (1945) |

Death toll of Jews |

|---|---|

| Albania | 591 |

| Austria | 65,459 |

| Baltic states | 272,000 |

| Belgium | 28,518 |

| Bulgaria | 11,393 |

| Croatia | 32,000 |

| Czechoslovakia | 143,000 |

| Denmark | 116 |

| France | 76,134 |

| Germany | 165,000 |

| Greece | 59,195 |

| Hungary | 502,000 |

| Italy | 6,513 |

| Luxembourg | 1,200 |

| Netherlands | 102,000 |

| Norway | 758 |

| Poland | 2,100,000 |

| Romania | 220,000 |

| Serbia | 10,700 |

| Soviet Union | 2,100,000 |

| Total | 5,896,577 |

According to the Yad Vashem Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem, "[a]ll the serious research" confirms that between five and six million Jews died.[395] Early postwar calculations were 4.2 to 4.5 million from Gerald Reitlinger;[396] 5.1 million from Raul Hilberg; and 5.95 million from Jacob Lestschinsky.[397] In 1986 Lucy S. Dawidowicz used the pre-war census figures to estimate 5.934 million.[398] Yehuda Bauer and Robert Rozett in the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust (1990) estimate 5.59–5.86 million.[399] A 1996 study led by Wolfgang Benz suggested 5.29 to 6.2 million, based on comparing pre- and post-war census records and surviving German documentation on deportations and killings.[395] Martin Gilbert arrived at a minimum of 5.75 million.[400] The figures include over one million children.[401]

The Jews killed represented around one third of the world population of Jews,[402] and about two-thirds of European Jewry, based on an estimate of 9.7 million Jews in Europe at the start of the war.[403][399] Much of the uncertainty stems from the lack of a reliable figure for the number of Jews in Europe in 1939, numerous border changes that make avoiding double-counting of victims difficult, lack of accurate records from the perpetrators, and uncertainty about whether deaths occurring months after liberation, but caused by the persecution, should be counted.[396]

Almost all Jews within areas occupied by the Germans were killed. There were 3,020,000 Jews in the Soviet Union in 1939, and the losses were 1–1.1 million.[404] Around one million Jews were killed by the Einsatzgruppen in the occupied Soviet territories.[405][406] Of Poland's 3.3 million Jews, about 90 percent were killed.[365] Many more died in the ghettos of Poland before they could be deported.[407] The death camps accounted for half the number of Jews killed; 80–90 percent of death-camp victims are estimated to have been Jews.[398] At Auschwitz-Birkenau the Jewish death toll was 1.1 million;[282][408] Treblinka 870,000–925,000;[409] Bełżec 434,000–600,000;[410][283] Chełmno 152,000–320,000;[411][284] Sobibór 170,000–250,000;[412][287] and Majdanek 79,000.[285]

Roma

Because the Roma are traditionally a private people with a culture based on oral history, less is known about their experience during the Holocaust than that of any other group.[413] Bauer writes that this can be attributed to the Roma's distrust and suspicion, and to their humiliation because some of the taboos in Romani culture regarding hygiene and sex were violated at Auschwitz.[414]

The Roma were subject to discrimination under the Nuremberg racial laws.[415] The Germans saw them as hereditary criminals and "asocials", and this was reflected in their classification in the concentration camps, where they were usually counted among the asocials and given black triangles to wear.[416] According to Niewyk and Nicosia, at least 130,000 died, out of nearly one million in German-occupied Europe.[413] The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum calculates at least 220,000.[417] Ian Hancock, who specializes in Romani history and culture, argues for between 500,000 and 1,500,000.[418] The Roma refer to the genocide as the Pořajmos.[419]