National anthem of Russia

| English: State Anthem of the Russian Federation | |

|---|---|

| Государственный гимн Российской Федерации | |

Performance of the Hymn of the Russian Federation by the Presidential Orchestra and Kremlin Choir at the inauguration of President Dmitry Medvedev at The Kremlin on 7 May 2008. | |

National anthem of Russia | |

| Lyrics | Sergey Mikhalkov, 2000 |

| Music | Alexander Alexandrov, 1939 |

| Adopted | 25 December 2000 (music)[1] 30 December 2000 (lyrics)[2] |

| Audio sample | |

Hymn of the Russian Federation (Instrumental) | |

The National Anthem of the Russian Federation (Russian: Государственный гимн Российской Федерации, "Gosudarstvenny Gimn Rossiyskoy Federatsii") is the national anthem of Russia. Its musical composition and lyrics were adopted from the anthem of the Soviet Union, composed by Alexander Alexandrov and lyricists Sergey Mikhalkov and Gabriel El-Registan. The Soviet anthem was used from 1944, replacing "The Internationale" with a more Russian-centric song. The anthem was amended in 1956 to remove lyrics that had references to former Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. The anthem was amended again in 1977 to introduce new lyrics written by Mikhalkov.

Russia sought a new anthem in 1990 to start anew after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The lyric-free "Patrioticheskaya Pesnya", composed by Mikhail Glinka, was officially adopted in 1993 by Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR, Boris Yeltsin. The government sponsored contests to create lyrics for the unpopular anthem because of its inability to inspire Russian athletes during international competitions. None of the entries were adopted, resulting in the restoration of the Soviet Union anthem by President Vladimir Putin. The government sponsored a contest to find lyrics lyrics, eventually settling on a composition by Mikhalkov. According to the government, the lyrics were selected to evoke and eulogize the history and traditions of Russia. The new anthem was adopted in late 2000, and become the second anthem used by Russia since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Public perception of the anthem is mixed among Russians. The anthem reminds some of the best days of Russia and past sacrifices, while it reminds others of the violence that occurred under the rule of Joseph Stalin. The Russian government contends that the anthem is a symbol of the unity of the people, and that it respects the past. In a 2009 poll, approximately 50% of respondents felt proud when hearing the anthem, but the other 50% either disliked it or could not recall the lyrics.

Historic anthems

Before "Molitva russkikh" (The Prayer of Russians) was chosen as the national anthem of Imperial Russia, various church hymns and military marches were used to honor the country and the Tsars. Songs used include "Grom pobedy, razdavaysya!" (Let the thunder of victory sound) and "Kol slaven" (How Glorious is Our Lord). "Molitva russkikh" was adopted around 1815, and used lyrics by Vasily Zhukovsky set to the music of the British anthem "God Save the King".[3] Russia's anthem was also influenced by the anthems of France and the Netherlands, and by the British patriotic song "Rule, Britannia!".[4]

In 1833, Zhukovsky was asked to set lyrics to a musical composition by Prince Alexei Lvov called "The Russian People's Prayer". Known more commonly as "God Save The Tsar!", it was well-received by Nicholas I, who chose the song to be the next anthem of Imperial Russia. The song resembled a religious hymn, and its musical style was similar to that of other anthems used by European monarchs. "God Save the Tsar" was performed for the first time on 8 December 1833 at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. It was later played at the Winter Palace on Christmas Day by order of Nicholas I. Public singing of the anthem began at opera houses in 1834, but it was not widely known across the Russian Empire until 1837.[5]

"God Save the Tsar" was used until the February Revolution, when the Russian monarchy was overthrown.[6] Upon the removal of the Tsar and his family in March 1917, the "Worker's Marseillaise", Pyotr Lavrov's modification of the French anthem La Marseillaise, was used as an unofficial anthem by the Russian Provisional Government. The modifications made by Lavrov to "La Marseillaise" included a change in meter from 2/2 to 4/4 and music harmonization to make it more Russian. It was used at government meetings, welcoming ceremonies for diplomats, and state funerals.[7]

After the provisional government had been overthrown by the Bolsheviks in the 1917 October Revolution, the anthem of international revolutionary socialism, "L'Internationale" (usually known as "The Internationale" in English), was adopted as the new anthem. The lyrics were created by Eugène Pottier, and the music was composed by Pierre Degeyter in 1871 to honor the creation of the Second Socialist International organization. The lyrics by Pottier were later translated into Russian by Arkadiy Yakovlevich Kots in 1902. Kots also changed the tense of the song to make it more decisive in nature.[8]

Before Lenin's return to Russia from exile, the Russian people were largely unfamiliar with "The Internationale". The first major use of the song was at the funeral of victims of the February Revolution in Petrograd. Lenin also wanted "The Internationale" to be played more often because it was more socialist, and could not be confused with the French anthem.[7] Other forces in the new Soviet government felt that the Marseillaise was too much of a song for the bourgeoisie.[9] The Internationale was used as the anthem of Soviet Russia from 1918, adopted by the newly-created Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922, and was used until 1944.[10]

The post-1944 Soviet anthem

Music

The music of the national anthem, created by Alexander Alexandrov, had previously been incorporated in several hymns and compositions. The music was first used in the Hymn of the Bolshevik Party, created in 1939. When the Comintern was dissolved in 1943, the government argued that the Internationale, which was historically associated with the Comintern, should be replaced as the National Anthem of the Soviet Union. Alexandrov's music was chosen as the new anthem by the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin after a contest in 1943. Stalin praised the song for fulfilling what a national anthem should be, though he criticized the song's orchestration.[11]

In response, Alexandrov blamed the problems on Viktor Knushevitsky, who was responsible for orchestrating the entries for the final contest rounds.[11][12] When writing the Bolshevik party anthem, Alexandrov incorporated pieces from the song "Zhit' stalo luchshe" ("Life Has Become Better"), a musical comedy that he composed.[13] This comedy was based on a slogan Stalin first used in 1935 after the Ukraine famine and Moscow purges.[14] Over 200 entries were submitted for the anthem contest, including some by famous Soviet composers Dmitri Shostakovich, Aram Khachaturian and Iona Tuskiya.[12] Later, the rejected joint entry by Khachaturian and Shostakovich became Song of the Red Army,[12] and Khachaturian went on to compose the Anthem of the Armenian SSR.[15][16]

During the 2000 anthem debate, Boris Gryzlov, the leader of the Unity faction in the Duma, pointed out that the music Alexandrov created for the Soviet anthem was similar to Vasily Kalinnikov's 1892 overture "Bylina".[17] The supporters of the Soviet anthem used this fact in the various debates that took place in the Duma about the anthem change.[18] There is no evidence that Alexandrov deliberately borrowed or used parts of "Bylina" in his composition.

Lyrics

After selecting the music by Alexandrov for the anthem, Stalin needed new lyrics for it. He thought the anthem was short and, because of the Great Patriotic War, that it needed a statement about the Red Army going on to defeat Fascist Germany. The poets Sergey Mikhalkov and Gabriel El-Registan were called to Moscow by one of Stalin's staffers, and were told to fix the lyrics to Alexandrov's music. They were instructed to keep the verses the same, but to find a way to change the refrains to where the song sings about "a Country of Soviets". Because of issues with singing when talking about the Red Army beating Fascist Germany, that idea was dropped from the version which El-Registan and Mikhalkov completed overnight. After a few minor changes to emphasize the Russian Motherland, Stalin approved the anthem and had it unveiled to the public on 7 November 1943.[19][20] The anthem also included a line where Stalin "inspired us to keep the faith with the people".[21]

The anthem was announced to all of the USSR on 1 January 1944 and became official on 15 March 1944.[22][23] Upon the death of Stalin in 1953, the Soviet government began to examine his legacy, and uncovered the crimes he committed against the Soviet people. They began the De-Stalinization process, which included downplaying the role of Stalin and moving his corpse from Lenin's Mausoleum to the Kremlin Wall Necropolis.[24] In addition, the anthem lyrics composed by Mikhalkov and El-Registan were officially scrapped by the Soviet government in 1956.[25]

The anthem was still used by the Soviet government, but without any official lyrics. In private, this anthem became known the "Song Without Words".[26] Mikhalkov wrote a new set of lyrics in 1970, but they were not submitted to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet until 27 May 1977. The new lyrics, which eliminated any mention of Stalin, were approved on 1 September, and were made official with the printing of the new Soviet Constitution in October 1977.[23] In the credits for the 1977 lyrics, Mikhalkov was mentioned, but references to El-Registan, who died in 1945, were dropped for unknown reasons.[26]

Patrioticheskaya Pesnya

With the impending collapse of the Soviet Union, a new national anthem was needed to redefine the reorganized nation and to reject the Soviet past. The Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR, Boris Yeltsin, was advised to revive "God Save The Tsar" with modifications to the lyrics. However, he instead selected a piece composed by Mikhail Glinka. The piece, known as "Patrioticheskaya Pesnya", was a wordless piano composition discovered after Glinka's death. "Patrioticheskaya Pesnya" was performed in front of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR on 23 November 1990.[27]

Between 1990 and 1993, many votes were called for in the State Duma to make "Patrioticheskaya Pesnya" the official anthem of Russia. However, it faced stiff opposition from members of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, who wanted the Soviet anthem restored.[27] Constitutionally, the state symbols of Russia are an anthem, flag and coat of arms. According to Article 70 of the Constitution, these state symbols required further definition by future legislation..[28] As it was a constitutional matter, it had to be passed by a two-thirds majority in the Duma.[29] Yeltsin, then President of the Russian Federation, eventually issued a decree on 11 December 1993, making "Patrioticheskaya Pesnya" the official anthem for Russia.[23][30]

Call for lyrics

During the entire period that "Patrioticheskaya Pesnya" was used as the national anthem, it never had official lyrics.[31] The anthem struck a positive chord because it did not contain any element from the Soviet past, and because the public saw Glinka as a patriot and a true Russian.[27] However, the lack of lyrics doomed "Patrioticheskaya Pesnya".[32] Various attempts were made to compose lyrics for the anthem, including a contest that allowed any Russian citizen to participate. A committee set up by the government looked at over 6000 entries, and 20 were recorded by an orchestra for a final vote.[33]

The eventual winner was Viktor Radugin's "Be glorious, Russia" (Славься, Россия! ("Slavsya, Rossiya!)).[34] However, none of the lyrics were officially adopted by Yeltsin or the Russian government. One of the reasons that partially explained the lack of lyrics was the original use of Glinka's composition: the praise of the Tsar and of the Russian Orthodox Church.[35] Other complaints raised about the song were that it was hard to remember, uninspiring, and musically complicated.[36] It was one of the few national anthems during this period that lacked official lyrics.[37] The only other wordless national anthems in the period from 1990 to 2000 were My Belarusy of Belarus[38] (until 2002),[39] "Marcha Real" of Spain,[40] and "Intermezzo" of Bosnia and Herzegovina[41] (until 2009).[42]

Modern adoption

The anthem debate intensified in October 2000 when Yeltsin's successor, Vladimir Putin, was approached by Russian athletes who were concerned that they had no words to sing for the anthem during the medal ceremonies at the 2000 Summer Olympic Games. Putin brought public attention to the issue and put it before the State Council.[36]

CNN also reported that members of the Spartak Moscow football club complained that the wordless anthem "affected their morale and performance".[43] Two years earlier, during the 1998 World Cup, members of the Russian team commented that the wordless anthem failed to inspire "great patriotic effort."[31]

In a November session of the Federation Council, Putin stated that establishing the national symbols (flag, anthem and coat of arms) should be a top priority for the country.[44] Putin pressed for the former Soviet anthem to be selected as the new Russian anthem, but strongly suggested that new lyrics be written. He did not say how much of the old Soviet lyrics should be retained for the new anthem.[31] Putin submitted the bill "On the National Anthem of the Russian Federation" to the Duma for their consideration on 4 December.[33] The Duma voted 381–51–1 in favor of adopting Alexandrov's music as the national anthem on 8 December 2000.[45] Following the vote, a committee was formed and tasked with exploring lyrics for the national anthem. After receiving over 6,000 manuscripts from all sectors of Russian society,[46] the committee selected lyrics by Mikhalkov for the anthem.[33]

Before the official adoption of the lyrics, the Kremlin released a section of the anthem, which made a reference to the flag and coat of arms:

Its mighty wings spread above us

The Russian eagle is hovering high

The Motherland’s tricolor symbol

Is leading Russia’s peoples to victory— Kremlin source, [47]

The above lines were omitted from the final version of the lyrics. After the bill was approved by the Federation Council on 20 December,[48] "On the National Anthem of the Russian Federation" was signed into law by President Putin on 25 December, officially making Alexandrov's music the national anthem of Russia. The law was published two days later in the official government journal Rossiyskaya Gazeta.[49] The new anthem was first performed on 30 December, during a ceremony at the Great Kremlin Palace in Moscow at which Mikhalkov's lyrics were officially made part of the national anthem.[50][51]

Not everyone agreed with the adoption of the new anthem. Yeltsin argued that Putin should not have changed the anthem merely to "follow blindly the mood of the people".[52] Yeltsin also felt that the restoration of the Soviet anthem was part of a move to reject post-communist reforms that had taken place since Russian independence and the fall of the Soviet Union.[32] This was one of Yeltsin's few public criticisms of Putin.[53]

The liberal political party Yabloko stated that the re-adoption of the Soviet anthem "deepened the schism in [Russian] society".[52] The Soviet anthem was supported by the Communist Party and by Putin himself. The other national symbols used by Russia in 1990, the white/blue/red tricolor flag and the double-headed eagle coat of arms, were also given legal approval by Putin in December, thus ending the debate over the national symbols.[54] After all of the symbols were adopted, Putin said on television that this move was needed to heal Russia's past and to fuse the short period of the Soviet Union with Russia's long history. He also stated that, while Russia's march towards democracy would not be stopped,[55] the rejection of the Soviet era would have left the lives of their mothers and fathers bereft of meaning.[56] It took some time for the Russian people to familiarize themselves with the anthem's lyrics; athletes were only able to hum along with the anthem during the medal ceremonies at the 2002 Winter Olympics.[32]

Public perception

The Russian national anthem is set to the melody of the Soviet anthem (used since 1944). As a result, there have been several controversies related to its use. For instance, some—including cellist Mstislav Rostropovich—have vowed not to stand during the anthem.[57][58] Russian cultural figures and government officials were also troubled by Putin's restoration of the Soviet anthem. A former adviser to both Yeltsin and Gorbachev stated that, when "Stalin's hymn" was used as the national anthem of the Soviet Union, millions were executed and other horrific crimes took place.[58]

At the 2007 funeral of Boris Yeltsin, the Russian anthem was played as his coffin was laid to rest at the Novodevichy cemetery in Moscow.[53] While it was common to hear the anthem during state funerals for Soviet civil and military officials,[59] honored citizens of the nation,[60] and Soviet leaders, as was the case for Brezhnev,[61] Andropov[62] and Chernenko,[63] some felt that playing the anthem at Yeltsin's funeral "abused the man who brought freedom" to the Russian people.[64] The Russian government's stand is that the "solemn music and poetic work" of the anthem, despite its history, is a symbol of unity for the Russian people. The words by Mikhalkov show "feelings of patriotism, respect for the history of the country and its system of government."[49]

In a 2009 poll conducted by the Russian Public Opinion Research Center and publicized just two days before Russia's flag day (22 August), 56% of respondents stated that they felt proud when hearing the national anthem. However, only 39% could recall the words of the first line of the anthem. This was an increase from 33% in 2007. According to the survey, between 34 and 36% could not identify the anthem's first line. Overall, only 25% of respondents said they liked the anthem.[65] In the previous year, the Russian Public Opinion Research Center found out that 56% of Russians feel pride and admiration at the anthem, even though only 40% (up from 19% in 2004) knew the first words of the anthem. It was also noted in the survey that the younger generation is the most familiar with the words.[66]

In September 2009, a line from the lyrics used during Stalin's rule reappeared at the Moscow Metro station Kurskaya-Koltsevaya: "Stalin reared us on loyalty to the people. He inspired us to labor and heroism." While groups have threatened legal action to stop the addition of this phrase, it was part of the original design of Kurskaya station and had been removed during de-Stalinization. Most of the commentary surrounding this event centered on the Kremlin's attempt to "rehabilitate the image" of Stalin by using symbolism sympathetic to or created by him.[67]

The Communist Party strongly supported the restoration of Alexandrov's melody, but some members proposed other changes to the anthem. In March of 2010, Boris Kashin, a CPRF member of the Duma, advocated for the removal of any reference to God in the anthem. Kashin's suggestion was also supported by Alexander Nikonov, a journalist with SPID-INFO and an avowed atheist. Nikonov's argued that religion should be a private matter and should not be used by the state.[68] Kashin also found out that the cost for making a new anthem recording will be about 120,000 rubles. The Russian Government quickly rejected the request because it lacked statistical data and other findings.[69] Nikonov also asked the Constitutional Court of Russia in 2005 if the lyrics are compatible with Russian law.[70]

Regulations

Regulations for the performance of the national anthem are set forth in the law signed by President Putin on 25 December 2000. While a performance of the anthem may include only music, only words, or a combination of both, the anthem must be performed using the official music and words prescribed by law. Once a performance has been recorded, it may be used for any purpose, such as a radio or television broadcast. The anthem may be played for solemn or celebratory occasions, such as the annual Victory Day parade in Moscow,[71] or the funerals of heads of state and other significant figures. When asked about playing the anthem during the Victory Day parades, Defense Minister Anatoliy Serdyukov stated that due to the acoustics of the Red Square, only an orchestra would be used because voices would be swallowed by the echo.[72]

The anthem is mandatory at the swearing-in of the President of Russia, for opening and closing sessions of the Duma and the Federation Council, and for official state ceremonies. The anthem is also played on television and radio at the beginning and end of the broadcast day. If programming is continuous, the anthem is played once at 0600 hours and again at midnight. It is also played on New Years Eve after a speech by the President. The anthem is played at sporting events both in Russia and abroad, according to the protocol of the organization that is hosting the games. When the anthem is played, all headgear must be removed and all those in attendance must face the Russian flag, if it is present. Those who are in uniform must give a military salute when the anthem plays.[1]

The anthem is performed in 4/4 (common time) or in 2/4 (half time) in the key of C major, and has a tempo of 76. Using either time signature, the anthem must be played in a festive and quick tempo (Торжественно and Распевно in Russian). The government has released different notations for orchestras, brass bands and wind bands.[73][74]

According to Russian copyright law, state symbols and signs are not protected by copyright.[75] As such, the anthem's music and lyrics can be used and modified freely. Although the law calls for the anthem to be performed respectfully and for performers to avoid causing offense, it defines no offensive acts or penalties.[1] Standing for the anthem is required by law but, again, the law gives no penalty for refusing to stand.[76]

On one occasion in the summer of 2004, President Putin chastised the national football team for their behavior during the playing of the anthem. During the opening ceremonies of the 2004 European Football Championship, the team was caught on camera chewing gum during the Russian anthem. Through Leonid Tyagachev, who was then head of the Russian Olympic Committee, Putin told the team to stop chewing gum and to sing the anthem. Gennady Shvets, then the Russian Olympic Committee's press chief, denied any contact from the Kremlin but said he was aware of displeasure in relation to the players' behaviour.[77]

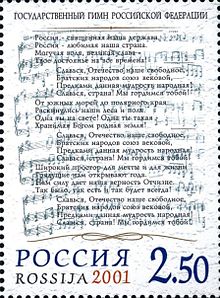

Official lyrics

| Russian[2] | Transliteration | English translation[78] |

|---|---|---|

|

Россия — священная наша держава, Припев:

От южных морей до полярного края Припев Широкий простор для мечты и для жизни Припев |

Rossiya — svyashchennaya nasha derzhava, Pripev:

Ot yuzhnykh morey do polyarnogo kraya Pripev Shirokiy prostor dlya mechty i dlya zhizni. Pripev |

Russia — our holy nation, Chorus:

From the southern seas to the polar lands Chorus Wide spaces for dreams and for living Chorus |

References

- Notes

- ^ a b c Federal Constitutional Law on the National Anthem of the Russian Federation

- ^ a b Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 30.12.2000 N 2110

- ^ Bohlman 2004, pp. 157

- ^ Голованова 2003, pp. 127–130

- ^ Wortman 2006, pp. 158–160

- ^ Studwell 1996, pp. 75

- ^ a b Stites 1991, pp. 87

- ^ Gasparov 2005, pp. 209–210

- ^ Figes 1999, pp. 62–63

- ^ Volkov 2008, pp. 34

- ^ a b Fey 2005, pp. 139

- ^ a b c Shostakovich 2002, pp. 261–262

- ^ Haynes 2003, pp. 70

- ^ Kubik 1994, pp. 48

- ^ "List of Works". Virtual Museum of Aram Khachaturian. “Aram Khachaturian” International Enlightenment-Cultural Association. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ Sandved 1963, pp. 690

- ^ "Гимн СССР написан в XIX веке Василием Калинниковым и Робертом Шуманом". Лента.Ру (in Russian). Rambler Media Group. 2000-12-08. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ Резепов, Олег (2000-12-08). "Выступление Бориса Грызлова при обсуждении законопроекта о государственной символике Российской Федерации" (in Russian). Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ Montefiore 2005, pp. 460–461

- ^ Volkov, Solomon (2000-12-16). "Stalin´s Best Tune". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ Keep, 2004 & 41–42

- ^ "USSR Information Bulletin". Embassy of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. 4: 13. 1944. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ a b c Голованова 2003, pp. 150

- ^ Brackman 2000, pp. 412

- ^ Wesson 1978, pp. 265

- ^ a b Ioffe 1988, pp. 331

- ^ a b c Service 2006, pp. 198–199

- ^ "Constitution of the Russian Federation". Government of the Russian Federation. 1993-12-12. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ^ "Russians to hail their 'holy country'". CNN.com. CNN. 2000-12-30. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 11.12.93 N 2127

- ^ a b c Franklin 2004, pp. 116

- ^ a b c Sakwa 2008, pp. 224

- ^ a b c "National Anthem". Russia's State Symbols. RIA Novosti. 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ Владимирова, Бориса (2002-01-23). "Неудавшийся гимн: Имя страны – Россия!". Московской правде (in Russian). Retrieved 2009-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Graubard 1998, pp. 131

- ^ a b Zolotov, Andrei (2000-12-01). "Russian Orthodox Church Approves as Putin Decides to Sing to a Soviet Tune". Christianity Today Magazine. Christianity Today International. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- ^ Waxman 1998, pp. 170

- ^ Korosteleva 2002, pp. 118

- ^ "Указ № 350 ад 2 лiпеня 2002 г. "Аб Дзяржаўным гімне Рэспублікі Беларусь"". Указу Прэзiдэнта Рэспублiкi Беларусь (in Belarusian). Пресс-служба Президента Республики Беларусь. 2002-07-02. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Spain: National Symbols: National Anthem". Spain Today. Government of Spain. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- ^ "Himna Bosne i Hercegovine" (in Bosnian). Ministarstvo vanjskih poslova Bosne i Hercegovine. 2001. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- ^ "Prijedlog teksta himne BiH utvrdilo Vijeće ministara BiH" (in Croatian). Ministarstvo pravde Bosne i Hercegovine. 2009-06-04. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Duma approves old Soviet anthem". CNN.com. CNN. 2000-12-08. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- ^ Shevtsova 2005, pp. 123

- ^ "Russian Duma Approves National Anthem Bill". People's Daily Online. People's Daily. 2000-12-08. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ "Guide to Russia – National Anthem of the Russian Federation". Russia Today. Strana.ru. 2002-09-18. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ Shukshin, Andrei (2000-11-30). "Putin Sings Praises of Old-New Russian Anthem". ABC News. American Broadcasting Company. p. 2. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ Голованова 2003, pp. 152

- ^ a b "Государственный гимн России" (in Russian). Администрация Приморского края. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ^ "State Insignia -The National Anthem". President of the Russian Federation. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- ^ "Russia Unveils New National Anthem Joining the Old Soviet Tune to the Older, Unsoviet God". The New York Times. 2000-12-31. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ a b "Duma approves Soviet anthem". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 2000-12-08. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- ^ a b Blomfield, Adrian (2007-04-26). "In death, Yeltsin scorns symbols of Soviet era". Telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- ^ Bova 2003, pp. 24

- ^ Nichols 2001, pp. 158

- ^ Hunter 2004, pp. 195

- ^ "Yeltsin "Categorically Against" Restoring Soviet Anthem". Monitor. 6 (228). 2000-12-07.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Banerji 2008, pp. 275–276

- ^ "Last Honors Paid Marshal Shaposhnikov". USSR Information Bulletin. 5: 5. 1945. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Condee 1995, pp. 44

- ^ Scoon 2003, pp. 77

- ^ "Andropov Is Buried at the Kremlin Wall". The Current Digest of the Soviet Press. 36 (7): 9. 1984. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- ^ "Soviets: Ending an Era of Drift". Time. Time Magazine. 1985-03-25. p. 2. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- ^ Berezovsky, Boris (2007-05-15). "Why modern Russia is a state of denial". Telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

- ^ "Most of Russians proud to hear national anthem, few know words – poll". Interfax. 2009-08-20. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ "ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЕ СИМВОЛЫ РОССИИ" (in Russian). Russian Public Opinion Research Center. 2008-06-11. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ^ Osborn, Andrew (2009-09-05). "Josef Stalin 'returns' to Moscow metro". Telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ "Notorious journalist backs up the idea to take out word "God" from Russian anthem". Interfax-Religion. Interfax. 2010-03-30. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ "God Beats Communists in Russian National Anthem". Komsomolskaya Pravda. PRAVDA.Ru. 2010-03-30. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Notorious journalist backs up the idea to take out word "God" from Russian anthem". Interfax-Religion. Interfax. 2010-03-30. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ "Russia marks Victory Day with parade on Red Square". People's Daily. People's Daily Online. 2005-05-09. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ "Defence Minister Commands 'Onwards to Victory!'". Rossiiskaya Gazeta. 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ^ "Гимн Российской Федерации" (in Russian). Official Site of the President of Russia. 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ "Музыкальная редакция: Государственного гимна Российской Федерации" (in Russian). Government of the Russian Federation. 2000. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Part IV of Civil Code No. 230-FZ of the Russian Federation. Article 1259. Objects of Copyright

- ^ Shevtsova 2005, pp. 144

- ^ "Putin: Stop chewing, start singing". Daily Mail Online. Associated Newspapers Ltd. 2004-07-28. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ "State Symbols of the Russian Federation". Consulate-General of the Russian Federation in Montreal, Canada. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- Bibliography

- Banerji, Arup (2008). Writing History in the Soviet Union: Making the Past Work. Berghahn Books. ISBN 8187358378.

- Bohlman, Philip Vilas (2004). The Music of European Nationalism: Cultural Identity and Modern History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-363-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bova, Russell (2003). Russia and Western Civilization. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-0977-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brackman, Roman (2000). The Secret File of Joseph Stalin: A Hidden Life. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-5050-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Condee, Nancy (1995). Soviet Hieroglyphics: Visual Culture in Late Twentieth-Century Russia. Indiana University Press. ISBN 025331402X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fey, Laurel E. (2005). Shostakovich: A Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195182514.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Figes, Orlando (1999). Interpreting the Russian Revolution: the language and symbols of 1917. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300081060.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Franklin, Simon (2004). National identity in Russian culture: an introduction. University of Cambridge Press. ISBN 0521839262.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Gasparov, Boris (2005). Five Operas and a Symphony: Word and Music in Russian Culture. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300106503.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Голованова, М. П. (2003). Государственные символы России (State Symbols of Russia). Росмэн-Пресс. ISBN 5353012860.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Graubard, Stephen (1998). "Ethnic National in the Russian Federation". A New Europe for the Old?. 126 (3). Retrieved 2009-12-19.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Haynes, John (2003). New Soviet Man. Manchester, United Kingdom: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719062381.

- Hunter, Shireen (2004). Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1283-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ioffe, Olimpiad Solomonovich (1988). "Chapter IV: Law of Creative Activity". Soviet Civil Law. 36 (36). Retrieved 2009-12-18.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keep, John (2004). Stalinism: Russian and Western Views at the Turn of the Millennium. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35109-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Korosteleva, Elena (2002). Contemporary Belarus Between Democracy and Dictatorship. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1613-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Kubik, Jan (1994). The Power of Symbols Against the Symbols of Power. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-01084-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Montefiore, Simon (2005). Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-7678-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nichols, Thomas (2001). The Russian presidency: society and politics in the second Russian Republic. Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. ISBN 0312293372.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sandved, Kjell Bloch (1963). The World of Music, Volume 2. Abradale Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sakwa, Richard (2008). Russian Politics and Society. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-41528-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Scoon, Paul (2003). Survival for Service: My Experiences as Governor General of Grenada. Macmillan Caribbean. ISBN 0333970640.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Service, Robert (2006). Russia: Experiment with a People. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674021088.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shevtsova, Lilia (2005). Putin's Russia. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. ISBN 0-87003-213-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shostakovich, Dimitri (2002). Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich. Limelight Editions. ISBN 978-0879109981.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Соболева, Надежда (2006). Символы и святыни Российской державы. ОЛМА Медиа Групп. ISBN 5373006041.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Stites, Richard (1991). Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195055373.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Studwell, William Emmett (1996). The National and Religious Song Reader: Patriotic, Traditional, and Sacred Songs from Around the World. Routledge. ISBN 0789000997.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Volkov, Solomon (2008). The Magical Chorus: A History of Russian Culture from Tolstoy to Solzhenitsyn. Random House. ISBN 9781400042722.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Wesson, Robert (1978). Lenin's Legacy. Hoover Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-6922-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Waxman, Mordecai (1998). Yakar le'Mordecai. KTAV Publishing House. ISBN 0881256323.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Wortman, Richard (2006). Scenarios of Power: Myth and Ceremony in Russian Monarchy from Peter the Great to the Abdication of Nicholas II. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12374-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Legislation

- Правительство Российской Федерации. Указ Президента РФ от 11.12.93 N 2127 "О Государственном гимне Российской Федерации" [Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of 11.12.1993, Number 2127 "On the National Anthem of the Russian Federation"].

- Government of the Russian Federation. Federal Constitutional Law of the Russian Federation – About the National Anthem of the Russian Federation; 2000-12-25 [Retrieved 2009-12-20].

- Kremlin.ru. Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 30.12.2000 N 2110 [Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of 30.12.2000]; 2000-12-30 [Retrieved 2009-12-20]. Russian.

- Правительство Российской Федерации. Part IV of Civil Code No. 230-FZ of the Russian Federation. Article 1259. Objects of Copyright; 2006-12-18 [Retrieved 2009-12-20]. Russian.

External links

- Template:Ru icon Government of Russia's website on the national symbols

- Template:Ru icon President of Russia State Insignia – National Anthem

- Russian Anthems museum – an extensive collection of audio recordings including some 30 recordings of the current anthem and recordings of other works mentioned in this article