Bupropion

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Wellbutrin, Zyban |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a695033 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | very low |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 5 to 20% in animals; no studies in humans |

| Protein binding | 84% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic—important CYP2B6 and 2D6 involvement |

| Elimination half-life | 11 hours [2] |

| Excretion | Renal (87%), fecal (10%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

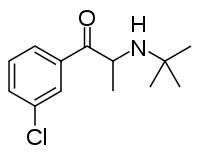

| Formula | C13H18ClNO |

| Molar mass | 239.74 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Bupropion (/bjuːˈproʊpi.ɒn/ bew-PROH-pee-on;[3]) is a drug primarily used as an atypical antidepressant and smoking cessation aid. Marketed as Wellbutrin, Budeprion, Prexaton, Elontril, Aplenzin, or other trade names, it is one of the most frequently prescribed antidepressants in the United States. Marketed in lower-dose formulations as Zyban, Voxra, or other names, it is also widely used to reduce nicotine cravings by people who are trying to quit smoking. It is taken in the form of pills, and in the United States is available only by prescription.

Medically, bupropion serves as a non-tricyclic antidepressant fundamentally different from most commonly prescribed antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). It is an effective antidepressant on its own, but is also popular as an add-on medication in cases of incomplete response to first-line SSRI antidepressants. In contrast to many other antidepressants, it does not cause weight gain or sexual dysfunction. The most important side effect is an increase in risk for epileptic seizures, which caused the drug to be withdrawn from the market for some time and then caused the recommended dosage to be reduced. 300mg a day (for average body weight) has been shown to maintain the same 0.1% unprovoked seizure rate of the general population.

Bupropion affects a number of neurotransmitter systems, and its mechanisms of action are only partly understood. The primary pharmacological action of the drug is as a mild dopamine reuptake inhibitor and also a much weaker norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor as well as a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist. Chemically, bupropion belongs to the class of aminoketones and is similar in structure to stimulants such as cathinone and amfepramone, and to phenethylamines in general.

Bupropion was patented in 1969 by Burroughs Wellcome, which later became part of what is now GlaxoSmithKline. It was originally called amfebutamone, before being renamed in 2000.[4] Its chemical name is 3-chloro-N-tert-butyl-β-ketoamphetamine. It is a substituted cathinone (β-ketoamphetamine), as well as a substituted amphetamine.

Medical uses

Depression

The most common use for bupropion is in the treatment of depression, where it is marketed by GlaxoSmithKline under the trade name Wellbutrin, or as a generic version under a variety of other names.

Bupropion is one of the most widely prescribed antidepressants, and the available evidence indicates that it is effective in clinical depression[5] — as effective as several other widely prescribed drugs, including sertraline (Zoloft), fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil)[6] and escitalopram (Lexapro).[7] It has several features that distinguish it from other antidepressants. Unlike the majority of antidepressants, bupropion does not usually cause sexual dysfunction.[8] Bupropion treatment also is not associated with the somnolence or weight gain that may be produced by other antidepressants.[9]

The majority of depressed people suffer from insomnia, but there are some who instead experience constant sleepiness and fatigue. In this subgroup, bupropion has been found to be more effective than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) at alleviating the symptoms.[10] There appears to be a modest advantage for the SSRIs compared to bupropion in the treatment of anxious depression.[11]

According to surveys, the augmentation of a prescribed SSRI with bupropion is a common strategy among clinicians when the patient does not respond to the SSRI, even though this is not an officially approved indication for prescription.[12] The addition of bupropion to an SSRI (most commonly fluoxetine or sertraline) results in a significant improvement in the majority of patients who have an incomplete response to the first-line antidepressant.[12]

Smoking cessation

The next most common use is as an aid for smoking cessation, where it is marketed by GlaxoSmithKline under the trade name Zyban, or by other makers as a generic equivalent.

Numerous studies have provided evidence that bupropion substantially reduces the severity of nicotine cravings and withdrawal symptoms.[13] For example, in one large-scale study, after a seven-week treatment, 27% of subjects who received bupropion reported that an urge to smoke was a problem, versus 56% of those who received placebo. In the same study, 21% of the bupropion group reported mood swings, versus 32% of the placebo group.[14] A typical bupropion treatment course lasts for seven to twelve weeks, with the patient halting the use of tobacco about ten days into the course. Bupropion approximately doubles the chance of quitting smoking successfully after three months. One year after treatment, the odds of sustaining smoking cessation are still 1.5 times higher in the bupropion group than in the placebo group.[13]

The evidence is clear that bupropion is effective at reducing nicotine cravings. Whether it is more effective than other treatments is not as clear, due to a limited number of studies. The evidence that is available suggests that bupropion is comparable to nicotine replacement therapy, but somewhat less effective than varenicline (Chantix).[13]

Seasonal Affective Disorder

Bupropion was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in 2006, for the prevention of seasonal affective disorder.[15]It was the first drug approved specifically for this condition.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

There have been numerous reports of positive results for bupropion as a treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), both in minors and adults.[16] However, in the largest to date double-blind study of children, which was conducted by GlaxoSmithKline, the results were inconclusive. Aggression and hyperactivity as rated by the children's teachers were significantly improved in comparison to placebo; in contrast, parents and clinicians could not distinguish between the effects of bupropion and placebo.[16] The 2007 guideline on the ADHD treatment from American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry notes that the evidence for bupropion is "far weaker" than for the FDA-approved treatments. Its effect may also be "considerably less than of the approved agents... Thus it may be prudent for the clinician to recommend a trial of behavior therapy at this point, before moving to these second-line agents."[17] Similarly, the Texas Department of State Health Services guideline recommends considering bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant as a fourth-line treatment after trying two different stimulants and atomoxetine.[18]

Sexual dysfunction

Bupropion is one of few antidepressants that do not cause sexual dysfunction.[19] A range of studies demonstrate that bupropion not only produces fewer sexual side effects than other antidepressants, but can actually help to alleviate sexual dysfunction.[20] According to a survey of psychiatrists, it is the drug of choice for the treatment of SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, although this is not an indication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 36% of psychiatrists preferred switching patients with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction to bupropion, and 43% favored the augmentation of the current medication with bupropion.[21] There have also been a few studies suggesting that bupropion can improve sexual function in women who are not depressed, if they have hypoactive sexual desire disorder.[22]

Obesity

A recent meta-analysis of anti-obesity medications pooled the results of three double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of bupropion. It confirmed the efficacy of bupropion given at 400 mg per day for treating obesity. Over a period of 6 to 12 months, weight loss in the bupropion group (4.4 kg) was significantly greater than in the placebo group (1.7 kg). It was not, however, significantly different from the weight loss produced by several other established medications, such as sibutramine, orlistat and amfepramone.[23]

Other uses

There has been controversy about whether it is useful to add an antidepressant such as bupropion to a mood stabilizer in patients with bipolar depression, but recent reviews have concluded that bupropion in this situation does no significant harm and may sometimes give significant benefit.[24][25]

Bupropion has shown no effectiveness in the treatment of cocaine dependence, but there is weak evidence that it may be useful in treating methamphetamine dependence.[26]

Based on studies indicating that bupropion lowers the level of the inflammatory mediator TNF-alpha, there have been suggestions that it might be useful in treating inflammatory bowel disease or other autoimmune conditions, but very little clinical evidence is available.[27]

Bupropion—like other antidepressants, with the exception of duloxetine (Cymbalta)[28]—is not effective in treating chronic low back pain.[29] It does, however, show some promise in the treatment of neuropathic pain.[30]

Contraindications

GlaxoSmithKline advises that bupropion should not be prescribed to individuals with epilepsy or other conditions that lower the seizure threshold, such as alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or active brain tumors. It should be avoided in individuals who are also taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). When switching from MAOIs to bupropion, it is important to include a washout period of about two weeks between the medications.[31] The prescribing information approved by the FDA recommends that caution should be exercised when treating patients with liver damage, severe kidney disease, and severe hypertension, as well as in pediatric patients, adolescents and young adults due to the increased risk of suicidal ideation.[31]

Adverse effects

Epileptic seizures are the most important adverse effect of bupropion. A high incidence of seizures was responsible for the temporary withdrawal of the drug from the market between 1986 and 1989. The risk of seizure is strongly dose-dependent, but also dependent on the preparation. The sustained-release preparation is associated with a seizure incidence of 0.1% at daily dosages of less than 300 mg of bupropion and 0.4% at 300–400 mg.[32] The immediate release preparation is associated with a seizure incidence of 0.4% for dosages below 450 mg; the incidence climbs to 5% for dosages between 450–600 mg per day.[32] For comparison, the incidence of unprovoked seizure in the general population is 0.07 to 0.09%, and the risk of seizure for a variety of other antidepressants is generally between 0 and 0.6% at recommended dosage levels.[33] Given that clinical depression itself has been reported to increase the occurrence of seizures, it has been suggested that low to moderate doses of antidepressants may not actually increase seizure risk at all.[34] However, this same study found that bupropion and clomipramine were unique among antidepressants in that they were associated with increased incidence of seizures.[34]

The prescribing information notes that hypertension, sometimes severe, was observed in some patients, both with and without pre-existing hypertension. The frequency of this adverse effect was under 1% and not significantly higher than found with placebo.[31] A review of the available data carried out in 2008 indicated that bupropion is safe to use in patients with a variety of serious cardiac conditions.[35]

In the UK, more than 7,600 reports of suspected adverse reactions were collected in the first two years after bupropion's approval by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency as part of the Yellow Card Scheme, which monitored side effects. Approximately 540,000 people were treated with bupropion for smoking cessation during that period. The MHRA received 60 reports of "suspected [emphasis MHRA's] adverse reactions to Zyban which had a fatal outcome". The agency concluded that "in the majority of cases the individual's underlying condition may provide an alternative explanation."[36] This is consistent with a large, 9,300-patient safety study that showed that the mortality of smokers taking bupropion is not higher than the natural mortality of smokers of the same age.[37]

The most common adverse effects associated with 12-hour sustained-release bupropion are reported to be dry mouth, nausea, insomnia, tremor, excessive sweating and tinnitus. Those that most often resulted in interruption of the treatment were rash (2.4%) and nausea (0.8%).[31]

Psychiatric

Suicidal thought and behavior are rare in clinical trials, but the FDA requires all antidepressants, including bupropion, to carry a boxed warning stating that antidepressants may increase the risk of suicide in persons younger than 25. This warning is based on a statistical analysis conducted by the FDA which found a 2-fold increase in suicidal thought and behavior in children and adolescents, and 1.5-fold increase in the 18–24 age group.[38] For this analysis the FDA combined the results of 295 trials of 11 antidepressants in order to obtain statistically significant results. Considered in isolation, bupropion was not statistically different from placebo.[38]

Suicidal behavior is less of a concern when bupropion is prescribed for smoking cessation. According to a 2007 Cochrane Database review, there have been four suicides per one million prescriptions and one case of suicidal ideation per ten thousand prescriptions of bupropion for smoking cessation in the UK. The review concludes, "Although some suicides and deaths while taking bupropion have been reported, thus far there is insufficient evidence to suggest they were caused by bupropion."[39]

In 2009 the FDA issued a health advisory warning that the prescription of bupropion for smoking cessation has been associated with reports about unusual behavior changes, agitation and hostility. Some patients, according to the advisory, have become depressed or have had their depression worsen, have had thoughts about suicide or dying, or have attempted suicide.[40] This advisory was based on a review of anti-smoking products that identified 75 reports of "suicidal adverse events" for bupropion over ten years.[41]

Psychotic symptoms associated with bupropion are rare. They may include delusions, hallucinations, paranoia, and confusion. In most cases these symptoms can be reduced or eliminated by decreasing the dose or ceasing treatment.[31][42] In many of these case reports, psychotic symptoms are associated with risk factors such as old age, a history of bipolar disorder or psychosis, and concomitant medications, for example, lithium or benzodiazepines.[43]

According to several case reports, stopping bupropion abruptly may result in a "discontinuation syndrome" expressed as dystonia, irritability, anxiety, mania, headache, aches and pains.[44] The prescribing information recommends dose tapering after bupropion has been used for seasonal affective disorder;[31] however it states that dose tapering is not required when discontinuing treatment for smoking cessation.[45]

Overdose

Bupropion is considered relatively safe in overdose. The most commonly reported symptom is epileptic seizures; other common symptoms include heart rhythm abnormalities, increased blood pressure, agitation, and hallucinations.[22][46]

In the majority of childhood exploratory ingestions involving one or two tablets, children show no apparent symptoms.[47] In teenagers and adults seizures are more commonly observed, with the seizure rate increasing tenfold with doses of 600 mg daily.[48]

Bupropion overdose rarely results in death, although some cases have been reported.[49] Fatalities are typically associated with large overdosage and related to metabolic acidosis and hypoxia as complications of status epilepticus with associated cardiac arrest.

Interactions

Since bupropion is metabolized to hydroxybupropion by the CYP2B6 enzyme, drug interactions with CYP2B6 inhibitors are possible: this includes medications like paroxetine, sertraline, fluoxetine, diazepam, clopidogrel, and orphenadrine. The expected result is the increase of bupropion and decrease of hydroxybupropion blood concentration. The reverse effect (decrease of bupropion and increase of hydroxybupropion) can be expected with CYP2B6 inducers, such as carbamazepine, clotrimazole, rifampicin, ritonavir, St John's wort, phenobarbital, phenytoin and others.[50] Conversely, because bupropion is itself an inhibitor of CYP2D6,[51] it can slow the clearance of other drugs metabolized by that enzyme.[50]

Bupropion lowers the threshold for epileptic seizures, and therefore can potentially interact with other medications that also lower it, such as theophylline, steroids, and some tricyclic antidepressants.[31] The prescribing information recommends minimizing the use of alcohol, since in rare cases bupropion reduces alcohol tolerance, and because the excessive use of alcohol may lower the seizure threshold.[31]

Pharmacology

As bupropion is rapidly converted in the body into several metabolites with differing activity, its action cannot be understood without reference to its metabolism. The occupancy of dopamine transporter (DAT) sites by bupropion and its metabolites in the human brain as measured by positron emission tomography was 6–22% in an independent study[52] and 12–35% according to GlaxoSmithKline researchers.[53] Based on analogy with serotonin reuptake inhibitors, higher than 50% inhibition of DAT would be needed for the dopamine reuptake mechanism to be a major mechanism of the drug's action. By contrast, approximately 65% occupancy or greater of DAT is required to achieve euphoria and reach abuse potential.[54] However recent research indicates that dopamine is inactivated by norepinephrine reuptake in the frontal cortex, which largely lacks dopamine transporters, therefore bupropion can increase dopamine neurotransmission in this part of the brain, and this may be one possible explanation for any additional dopaminergic effects.[55]

Bupropion has also been shown to act as a noncompetitive nicotinic antagonist.[56]

Outside the nervous system, both bupropion and its primary metabolite hydrobupropion act in the liver as potent inhibitors of the enzyme CYP2D6, which metabolizes not only bupropion itself but also a variety of other drugs and biologically active substances.[51] This mechanism creates the potential for a variety of drug interactions.

Pharmacokinetics

Bupropion is metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CYP2B6.[32] It has several active metabolites: R,R-hydroxybupropion, S,S-hydroxybupropion, threo-hydrobupropion and erythro-hydrobupropion, which are further metabolized to inactive metabolites and eliminated through excretion into the urine. Pharmacological data on bupropion and its metabolites are shown in the table. Bupropion is known to weakly inhibit the α1 adrenergic receptor, with a 14% potency of its dopamine uptake inhibition, and the H1 receptor, with a 9% potency.[57]

| Exposure (concentration over time; bupropion exposure = 100%) and half-life | |||||

| Bupropion | R,R- Hydroxy bupropion |

S,S- Hydroxy bupropion |

Threo- hydro bupropion |

Erythro- hydro bupropion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | 100% | 800% | 160% | 310% | 90% |

| Half-life | 10 h (IR) 17 h (SR) |

21 h | 25 h | 26 h | 26 h |

| Inhibition potency (potency of DA uptake inhibition by bupropion = 100%) | |||||

| DA uptake | 100% | 0% (rat) | 70% (rat) | 4% (rat) | No data |

| NE uptake | 27% | 0% (rat) | 106% (rat) | 16% (rat) | No data |

| 5HT uptake | 2% | 0% (rat) | 4%(rat) | 3% (rat) | No data |

| α3β4 nicotinic | 53% | 15% | 10% | 7% (rat) | No data |

| α4β2 nicotinic | 8% | 3% | 29% | No data | No data |

| α1* nicotinic | 12% | 13% | 13% | No data | No data |

| DA = dopamine; NE = norepinephrine; 5HT = serotonin. | |||||

The biological activity of bupropion can be attributed to a significant degree to its active metabolites, in particular to S,S-hydroxybupropion. GlaxoSmithKline developed this metabolite as a separate drug called radafaxine,[62] but discontinued development in 2006 due to "an unfavourable risk/benefit assessment".[63]

Bupropion is metabolized to hydroxybupropion by CYP2B6, an isozyme of the cytochrome P450 system. Alcohol causes an increase of CYP2B6 in the liver, and persons with a history of alcohol use metabolize bupropion faster. The mechanism of formation of erythro-hydrobupropion and threo-hydrobupropion has not been studied but is probably mediated by one of the carbonyl reductase enzymes. The metabolism of bupropion is highly variable: the effective doses of bupropion received by persons who ingest the same amount of the drug may differ by as much as 5.5 times (and the half-life from 3 to 16 hours), and of hydroxybupropion by as much as 7.5 times (and the half-life from 12 to 38 hours).[64] Based on this, some researchers have advocated monitoring of the blood level of bupropion and hydroxybupropion.[65]

There are significant interspecies differences in the metabolism of bupropion, with the metabolism in humans being more similar to guinea pigs than to mice and rats.[66] In fact hydroxybupropion, the main metabolite of bupropion in humans, is absent in rats.[67]

There have been two reported cases of false-positive urine amphetamine tests in persons taking bupropion. More specific follow-up tests were negative.[68][69]

Synthesis

Bupropion is a substituted cathinone. It is synthesized in two chemical steps starting from 3'-chloro-propiophenone. The alpha position adjacent to the ketone is first brominated followed by nucleophilic displacement of the resulting alpha-bromoketone with t-butylamine and treated with hydrochloric acid to give bupropion as the hydrochloride salt in 75–85% overall yield.[70][71]

Regulatory history

Bupropion was invented by Nariman Mehta of Burroughs Wellcome (now GlaxoSmithKline) in 1969, and the US patent for it was granted in 1974.[70] It was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an antidepressant on December 30, 1985, and marketed under the name Wellbutrin.[72] However, a significant incidence of epileptic seizures at the originally recommended dosage caused the withdrawal of the drug in 1986. Subsequently, the risk of seizures was found to be highly dose-dependent, and bupropion was re-introduced to the market in 1989 with a lower maximum recommended daily dose.[73]

In 1996, the FDA approved a sustained-release formulation of bupropion called Wellbutrin SR, intended to be taken twice a day (as compared with three times a day for immediate-release Wellbutrin).[74] In 2003, the FDA approved another sustained-release formulation called Wellbutrin XL, intended for once-daily dosing. Wellbutrin SR and XL are available in generic form in the United States, while in Canada, only the SR formulation is available in generic form. In 1997, bupropion was approved by the FDA for use as a smoking cessation aid under the name Zyban.[74] In 2006, Wellbutrin XL was similarly approved as a treatment for seasonal affective disorder.[75]

In April 2008, the FDA approved a formulation of bupropion as a hydrobromide salt instead of a hydrochloride salt, to be sold under the name Aplenzin by Sanofi-Aventis.[76]

On October 11, 2007, two providers of consumer information on nutritional products and supplements, ConsumerLab.com and The People's Pharmacy, released the results of comparative tests of different brands of bupropion.[77] The People's Pharmacy received multiple reports of increased side effects and decreased efficacy of generic bupropion, which prompted it to ask ConsumerLab.com to test the products in question. The tests showed that "one of a few generic versions of Wellbutrin XL 300 mg, sold as Budeprion XL 300 mg, didn't perform the same as the brand-name pill in the lab."[78] The FDA investigated these complaints and concluded that Budeprion XL is equivalent to Wellbutrin XL in regard to bioavailability of bupropion and its main active metabolite hydroxybupropion. The FDA also said that coincidental natural mood variation is the most likely explanation for the apparent worsening of depression after the switch from Wellbutrin XL to Budeprion XL.[79] On October 3, 2012, however, the FDA reversed this opinion, announcing that "Budeprion XL 300 mg fails to demonstrate therapeutic equivalence to Wellbutrin XL 300 mg."[80] The FDA did not test the bioequivalence of any of the other generic versions of Wellbutrin XL 300 mg, but requested that the four manufacturers submit data on this question to the FDA by March 2013.[80]

In 2012, the U.S. Justice Department announced that GlaxoSmithKline had agreed to plead guilty and pay a $3-billion fine, in part for promoting the unapproved use of Wellbutrin for weight loss and sexual dysfunction.[81]

In France, marketing authorization was granted for Zyban on August 3, 2001, with a maximum daily dose of 300 mg;[82] only sustained-release bupropion is available, and only as a smoking cessation aid. Bupropion was granted a licence for use in adults with major depression in the Netherlands in early 2007, with GlaxoSmithKline expecting subsequent approval in other European countries.[83]

Recreational use

According to the US government classification of psychiatric medications, bupropion is "non-abusable".[84] In animal studies, squirrel monkeys and rats could be induced to self-administer bupropion, which is often taken as a sign of addiction potential; however, there are significant interspecies differences in bupropion metabolism.[51] There have been a number of anecdotal and case-study reports of bupropion abuse, but the bulk of evidence indicates that the subjective effects of bupropion are markedly different from those of addictive stimulants such as cocaine or amphetamine.[85]

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, Twelfth Edition. McGraw Hill Professional; 2010.

- ^ "Bupropion (By mouth)" at PubMed health, retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ^ The INN originally assigned in 1974 by the World Health Organization was "amfebutamone". In 2000, the INN was reassigned as bupropion. See World Health Organization (2000). "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN). Proposed INN: List 83" (PDF). WHO Drug Information. 14 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2009.

- ^ Moreira R (2011). "The efficacy and tolerability of bupropion in the treatment of major depressive disorder". Clin Drug Investig. 31 Suppl 1: 5–17. doi:10.2165/1159616-S0-000000000-00000. PMID 22015858.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Thase ME, Haight BR, Richard N, Rockett CB, Mitton M, Modell JG, VanMeter S, Harriett AE, Wang Y (2005). "Remission rates following antidepressant therapy with bupropion or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of original data from 7 randomized controlled trials". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 (8): 974–81. doi:10.4088/JCP.v66n0803. PMID 16086611.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clayton AH, Croft HA, Horrigan JP, Wightman DS, Krishen A, Richard NE, Modell JG (2006). "Bupropion extended release compared with escitalopram: effects on sexual functioning and antidepressant efficacy in 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies". J Clin Psychiatry. 67 (5): 736–46. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0507. PMID 16841623.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clayton AH (2003). "Antidepressant-Associated Sexual Dysfunction: A Potentially Avoidable Therapeutic Challenge". Primary Psychiatry. 10 (1): 55–61.

- ^ Dhillon S, Yang LP, Curran MP (2008). "Bupropion: a review of its use in the management of major depressive disorder". Drugs. 68 (5): 653–89. doi:10.2165/00003495-200868050-00011. PMID 18370448.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baldwin DS, Papakostas GI (2006). "Symptoms of fatigue and sleepiness in major depressive disorder". J Clin Psychiatry. 67 Suppl 6 (Suppl 6): 9–15. PMID 16848671.

- ^ Papakostas GI, Stahl SM, Krishen A, Seifert CA, Tucker VL, Goodale EP, Fava M (2008). "Efficacy of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of major depressive disorder with high levels of anxiety (anxious depression): a pooled analysis of 10 studies". J Clin Psychiatry. 69 (8): 1287–92. doi:10.4088/JCP.v69n0812. PMID 18605812.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Zisook S, Rush AJ, Haight BR, Clines DC, Rockett CB (2006). "Use of bupropion in combination with serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Biol. Psychiatry. 59 (3): 203–10. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.027. PMID 16165100.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Wu P, Wilson K, Dimoulas P, Mills EJ (2006). "Effectiveness of smoking cessation therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Public Health. 6: 300. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-300. PMC 1764891. PMID 17156479.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Tønnesen P, Tonstad S, Hjalmarson A, Lebargy F, Van Spiegel PI, Hider A, Sweet R, Townsend J (2003). "A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 1-year study of bupropion SR for smoking cessation". J. Intern. Med. 254 (2): 184–92. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01185.x. PMID 12859700.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "First drug for seasonal depression". FDA Consum. 40 (5): 7. 2006. PMID 17328102.

- ^ a b Cantwell DP (1998). "ADHD through the life span: the role of bupropion in treatment". J Clin Psychiatry. 59 Suppl 4: 92–4. PMID 9554326.

- ^ Pliszka S; AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues (2007). "Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 46 (7): 894–921. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e318054e724. PMID 17581453.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pliszka SR, Crismon ML, Hughes CW, Corners CK, Emslie GJ, Jensen PS, McCracken JT, Swanson JM, Lopez M (2006). "The Texas Children's Medication Algorithm Project: revision of the algorithm for pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 45 (6): 642–57. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000215326.51175.eb. PMID 16721314.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Serretti A, Chiesa A (2009). "Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysis". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 29 (3): 259–66. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181a5233f. PMID 19440080.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Stahl SM, Pradko JF, Haight BR, Modell JG, Rockett CB, Learned-Coughlin S (2004). "A review of the neuropharmacology of bupropion, a dual norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor". Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 6 (4): 159–166. doi:10.4088/PCC.v06n0403. PMC 514842. PMID 15361919.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dording CM, Mischoulon D, Petersen TJ, Kornbluh R, Gordon J, Nierenberg AA, Rosenbaum JE, Fava M (2002). "The pharmacologic management of SSRI-induced side effects: a survey of psychiatrists". Ann Clin Psychiatry. 14 (3): 143–7. doi:10.3109/10401230209147450. PMID 12585563.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Foley KF, DeSanty KP, Kast RE (2006). "Bupropion: pharmacology and therapeutic applications". Expert Rev Neurother. 6 (9): 1249–65. doi:10.1586/14737175.6.9.1249. PMID 17009913.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Li Z, Maglione M, Tu W, Mojica W, Arterburn D, Shugarman LR, Hilton L, Suttorp M, Solomon V, Shekelle PG, Morton SC (2005). "Meta-analysis: pharmacologic treatment of obesity". Ann. Intern. Med. 142 (7): 532–46. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00012. PMID 15809465.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gijsman HJ, Geddes JR, Rendell JM, Nolen WA, Goodwin GM (2004). "Antidepressants for bipolar depression: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials". Am J Psychiatry. 161 (9): 1537–47. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1537. PMID 15337640.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O'Donovan C, Parikh SV, MacQueen G, McIntyre RS, Sharma V, Beaulieu S (2006). "Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007". Bipolar Disord. 8 (6): 721–39. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00432.x. PMID 17156158.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kampman KM (2008). "The search for medications to treat stimulant dependence". Addict Sci Clin Pract. 4 (2): 28–35. doi:10.1151/ascp084228. PMC 2797110. PMID 18497715.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Andrews JM, Holtmann GJ (2006). "Antidepressants and inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review". Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2: 24. doi:10.1186/1745-0179-2-24. PMC 1599716. PMID 16984660.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "FDA clears Cymbalta to treat chronic musculoskeletal pain". FDA Press Announcements. Food and Drug Administration. November 4, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration ... approved Cymbalta (duloxetine hydrochloride) to treat chronic musculoskeletal pain, including discomfort from osteoarthritis and chronic lower back pain.

- ^ Urquhart DM, Hoving JL, Assendelft WW, Roland M, van Tulder MW (2008). Urquhart DM (ed.). "Antidepressants for non-specific low back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001703. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001703.pub3. PMID 18253994.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shah TH, Moradimehr A (2010). "Bupropion for the treatment of neuropathic pain". Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 27 (5): 333–6. doi:10.1177/1049909110361229. PMID 20185402.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h "Wellbutrin XL Prescribing Information" (PDF). GlaxoSmithKline. 2008. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. 2003.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Pisani F, Oteri G, Costa C, Di Raimondo G, Di Perri R (2002). "Effects of psychotropic drugs on seizure threshold". Drug Saf. 25 (2): 91–110. doi:10.2165/00002018-200225020-00004. PMID 11888352.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Alper K, Schwartz KA, Kolts RL, Khan A (2007). "Seizure incidence in psychopharmacological clinical trials: an analysis of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) summary basis of approval reports". Biol. Psychiatry. 62 (4): 345–54. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.023. PMID 17223086.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Taylor D (2008). "Antidepressant drugs and cardiovascular pathology: a clinical overview of effectiveness and safety". Acta Psychiatr Scand. 118 (6): 434–42. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01260.x. PMID 18785947.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Zyban (bupropion hydrochloride) – safety update". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. July 24, 2002. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved October 7, 2006.

- ^ Hubbard R, Lewis S, West J, Smith C, Godfrey C, Smeeth L, Farrington P, Britton J (2005). "Bupropion and the risk of sudden death: a self-controlled case-series analysis using The Health Improvement Network". Thorax. 60 (10): 848–50. doi:10.1136/thx.2005.041798. PMC 1747199. PMID 16055620.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Levenson M, Holland C. "Antidepressants and suicidality in adults: statistical evaluation. (Presentation at Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee; December 13, 2006)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ^ Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T (2007). Hughes JR (ed.). "Antidepressants for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD000031. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub3. PMID 17253443.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Public Health Advisory: FDA requires new boxed warnings for the smoking cessation drugs Chantix and Zyban". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). July 1, 2009. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- ^ "The smoking cessation aids varenicline (marketed as Chantix) and bupropion (marketed as Zyban and generics) suicidal ideation and behavior" (PDF). Drug Safety Newsletter. 2 (1). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): 1–4. 2009.

- ^ Howard WT, Warnock JK (1999). "Bupropion-induced psychosis". Am J Psychiatry. 156 (12): 2017–8. PMID 10588428.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nemeroff CB, Schatzberg AF (2006). Essentials of clinical psychopharmacology. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 146. ISBN 1-58562-243-5.

- ^ Berigan TR (2002). "Bupropion-associated withdrawal symptoms revisited: a case report". Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 4 (2): 78. doi:10.4088/PCC.v04n0208a. PMC 181231. PMID 15014751.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Prescribing information – Zyban (bupropion hydrochloride) sustained-release tablets" (PDF). Glaxo Smith-Kline. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ^ Shepherd G, Velez LI, Keyes DC (2004). "Intentional bupropion overdoses". J Emerg Med. 27 (2): 147–51. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.02.017. PMID 15261357.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Beuhler MC, Spiller HA, Sasser HC (2010). "The outcome of unintentional pediatric bupropion ingestions: a NPDS database review". J Med Toxicol. 6 (1): 4–8. doi:10.1007/s13181-010-0027-4. PMC 3550434. PMID 20213217.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnston JA, Lineberry CG, Ascher JA, Davidson J, Khayrallah MA, Feighner JP, Stark P (1991). "A 102-center prospective study of seizure in association with bupropion". J Clin Psychiatry. 52 (11): 450–6. PMID 1744061.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Spiller HA, Bottei E, Kalin L (2008). "Fatal bupropion overdose with post mortem blood concentrations". Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 4 (1): 47–50. doi:10.1007/s12024-007-0030-5. PMID 19291469.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Jefferson JW, Pradko JF, Muir KT (2005). "Bupropion for major depressive disorder: Pharmacokinetic and formulation considerations". Clin Ther. 27 (11): 1685–95. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.11.011. PMID 16368442.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Dwoskin LP, Rauhut AS, King-Pospisil KA, Bardo MT (2006). "Review of the pharmacology and clinical profile of bupropion, an antidepressant and tobacco use cessation agent". CNS Drug Rev. 12 (3–4): 178–207. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00178.x. PMID 17227286.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meyer JH, Goulding VS, Wilson AA, Hussey D, Christensen BK, Houle S (2002). "Bupropion occupancy of the dopamine transporter is low during clinical treatment". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 163 (1): 102–5. doi:10.1007/s00213-002-1166-3. PMID 12185406.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Learned-Coughlin SM, Bergström M, Savitcheva I, Ascher J, Schmith VD, Långstrom B (2003). "In vivo activity of bupropion at the human dopamine transporter as measured by positron emission tomography". Biol. Psychiatry. 54 (8): 800–5. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01834-6. PMID 14550679.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Howell LL, Wilcox KM (2001). "The dopamine transporter and cocaine medication development: drug self-administration in nonhuman primates". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 298 (1): 1–6. PMID 11408518.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Bupropion". Stahlonline.cambridge.org. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ Arias HR (2009). "Is the inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by bupropion involved in its clinical actions?". Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41 (11): 2098–108. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2009.05.015. PMID 19497387.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Horst WD, Preskorn SH (1998). "Mechanisms of action and clinical characteristics of three atypical antidepressants: venlafaxine, nefazodone, bupropion". J Affect Disord. 51 (3): 237–54. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00222-5. PMID 10333980.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Johnston AJ, Ascher J, Leadbetter R, Schmith VD, Patel DK, Durcan M, Bentley B (2002). "Pharmacokinetic optimisation of sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation". Drugs. 62 Suppl 2: 11–24. doi:10.2165/00003495-200262002-00002. PMID 12109932.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Xu H, Loboz KK, Gross AS, McLachlan AJ (2007). "Stereoselective analysis of hydroxybupropion and application to drug interaction studies". Chirality. 19 (3): 163–70. doi:10.1002/chir.20356. PMID 17167747.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bondarev ML, Bondareva TS, Young R, Glennon RA (2003). "Behavioral and biochemical investigations of bupropion metabolites". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 474 (1): 85–93. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(03)02010-7. PMID 12909199.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Damaj MI, Carroll FI, Eaton JB, Navarro HA, Blough BE, Mirza S, Lukas RJ, Martin BR (2004). "Enantioselective effects of hydroxy metabolites of bupropion on behavior and on function of monoamine transporters and nicotinic receptors". Mol. Pharmacol. 66 (3): 675–82. doi:10.1124/mol.104.001313. PMID 15322260.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Reviews Novel Therapeutics For CNS Disorders And Confirms Strong Pipeline Momentum" (Press release). PRNewswire. November 23, 2004. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ GlaxoSmithKline (July 26, 2006) Template:PDFlink. Press release. Retrieved on August 18, 2007.

- ^ Hesse LM, He P, Krishnaswamy S, Hao Q, Hogan K, von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ, Court MH (2004). "Pharmacogenetic determinants of interindividual variability in bupropion hydroxylation by cytochrome P450 2B6 in human liver microsomes". Pharmacogenetics. 14 (4): 225–38. doi:10.1097/00008571-200404000-00002. PMID 15083067.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Preskorn SH (1991). "Should bupropion dosage be adjusted based upon therapeutic drug monitoring?". Psychopharmacol Bull. 27 (4): 637–43. PMID 1813908.

- ^ Suckow RF, Smith TM, Perumal AS, Cooper TB (1986). "Pharmacokinetics of bupropion and metabolites in plasma and brain of rats, mice, and guinea pigs". Drug Metab. Dispos. 14 (6): 692–7. PMID 2877828.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Welch RM, Lai AA, Schroeder DH (1987). "Pharmacological significance of the species differences in bupropion metabolism". Xenobiotica. 17 (3): 287–98. doi:10.3109/00498258709043939. PMID 3107223.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weintraub D, Linder MW (2000). "Amphetamine positive toxicology screen secondary to bupropion". Depress Anxiety. 12 (1): 53–4. doi:10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1<53::AID-DA8>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 10999247.

- ^ Nixon AL, Long WH, Puopolo PR, Flood JG (1995). "Bupropion metabolites produce false-positive urine amphetamine results". Clin. Chem. 41 (6 Pt 1): 955–6. PMID 7768026.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mehta NB (June 25, 1974). "United States Patent 3,819,706: Meta-chloro substituted α-butylamino-propiophenones". USPTO. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ^ Perrine DM, Ross JT, Nervi SJ, Zimmerman RH (2000). "A Short, One-Pot Synthesis of Bupropion (Zyban, Wellbutrin)". Journal of Chemical Education. 77 (11): 1479. Bibcode:2000JChEd..77.1479P. doi:10.1021/ed077p1479.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Wellbutrin label and approval history". U.S. Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ "Bupropion (Wellbutrin)". eMedExpert.com. March 31, 2008. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Whitten L (April 2006). "Bupropion helps people with schizophrenia quit smoking". National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Findings. 20 (5). Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ "Seasonal affective disorder drug Wellbutrin XL wins approval". CNN. June 14, 2006. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ^ Waknine, Yael (May 8, 2008). "FDA Approvals: Advair, Relistor, Aplenzin". Medscape. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ "Generic drug equality questioned". Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- ^ Jacqueline Stenson (October 12, 2007). "Report questions generic antidepressant". msnbc.com. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- ^ "Review of therapeutic equivalence: generic bupropion XL 300 mg and Wellbutrin XL 300 mg". Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ^ a b "Budeprion XL 300 mg not therapeutically equivalent to Wellbutrin XL 300 mg" (Press release). FDA. October 3, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ Thomas K, Schmidt MS (July 2, 2012). "Glaxo agrees to pay $3 billion in fraud settlement". The New York Times.

- ^ "Zyban : sevrage tabagique et sécurité d'emploi" (Press release) (in French). Agence française de sécurité sanitaire des produits de santé. January 18, 2002. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ GlaxoSmithKline (January 16, 2007). "GlaxoSmithKline receives first European approval for Wellbutrin XR" (Press release). GlaxoSmithKline. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ "Abuse potential of common psychiatric medications". Substance abuse treatment for persons with HIV/AIDS. Treatment Improvement Protocol. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. pp. 83–4.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Lile JA, Nader MA (2003). "The abuse liability and therapeutic potential of drugs evaluated for cocaine addiction as predicted by animal models". Current Neuropharmacology. 1: 21–46. doi:10.2174/1570159033360566.

External links

- Official Wellbutrin website

- List of international brand names for bupropion

- Bupropion at Curlie

- Wellbutrin Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics, Studies, Metabolism – Bupropion – RxList Monographs

- NAMI Wellbutrin

- Bupropion article from mentalhealth.com