Dublin

Dublin

Baile Átha Cliath | |

|---|---|

City | |

| Samuel Beckett Bridge, Convention Centre, Trinity College, O'Connell Bridge, The Custom House, Dublin Castle. | |

| Nickname: The Fair City | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Leinster |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Council |

| • Headquarters | Dublin City Hall |

| • Lord Mayor | Críona Ní Dhálaigh (SF) |

| • Dáil Éireann | Dublin Central Dublin Bay North Dublin North–West Dublin South–Central Dublin Bay South |

| • European Parliament | Dublin constituency |

| Area | |

• City | 114.99 km2 (44.40 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 318 km2 (123 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• City | 527,612[6] |

| • Density | 4,588/km2 (11,880/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,110,627[5] |

| • Metro | 1,801,040[4] |

| • Demonym | Dubliner Dub |

| • Ethnicity (2011 Census) | Ethnic groups |

| Time zone | UTC0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

| Eircode | D01 to D18, D20, D22, D24 & D6W |

| Area code | 01 (+3531) |

| GDP | US$ 90.1 billion[7] |

| GDP per capita | US$ 51,319[7] |

| Website | www |

Dublin (/ˈdʌbl[invalid input: 'i-']n/, Irish: Baile Átha Cliath [blʲaːˈklʲiəh]) is the capital and largest city of Ireland.[8][9] Dublin is in the province of Leinster on Ireland's east coast, at the mouth of the River Liffey. The city has an urban area population of 1,273,069.[10] The population of the Greater Dublin Area, as of 2011[update], was 1,801,040 persons.

Founded as a Viking settlement, the Kingdom of Dublin became Ireland's principal city following the Norman invasion. The city expanded rapidly from the 17th century and was briefly the second largest city in the British Empire before the Acts of Union in 1800. Following the partition of Ireland in 1922, Dublin became the capital of the Irish Free State, later renamed Ireland.

Dublin is administered by a City Council. The city is listed by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network (GaWC) as a global city, with a ranking of "Alpha-", placing it among the top thirty cities in the world.[11][12] It is a historical and contemporary centre for education, the arts, administration, economy and industry.

History

Toponymy

Although the area of Dublin Bay has been inhabited by humans since prehistoric times, the writings of Ptolemy (the Greco-Roman astronomer and cartographer) in about 140 AD provide possibly the earliest reference to a settlement there. He called the settlement Eblana polis (‹See Tfd›Greek: Ἔβλανα πόλις).[13]

Dublin celebrated its 'official' millennium in 1988 AD, meaning that the Irish government recognised 988 AD as the year in which the city was settled and that this first settlement would later become the city of Dublin.

The name Dublin comes from the Gaelic word Dublind, early Classical Irish Dubhlind/Duibhlind, dubh /d̪uβ/, alt. /d̪uw/, alt /d̪u:/ meaning "black, dark", and lind /lʲiɲ[d̪ʲ] "pool", referring to a dark tidal pool where the River Poddle entered the Liffey on the site of the Castle Gardens at the rear of Dublin Castle. In Modern Irish the name is Duibhlinn, and Irish rhymes from Dublin County show that in Dublin Leinster Irish it was pronounced Duílinn /d̪ˠi:lʲiɲ/. The original pronunciation is preserved in the names for the city in other languages such as Old English Difelin, Old Norse Dyflin, modern Icelandic Dyflinn and modern Manx Divlyn as well as Welsh Dulyn. Other localities in Ireland also bear the name Duibhlinn, variously anglicized as Devlin,[14] Divlin[15] and Difflin.[16] Historically, scribes using the Gaelic script wrote bh with a dot over the b, rendering Duḃlinn or Duiḃlinn. Those without knowledge of Irish omitted the dot, spelling the name as Dublin. Variations on the name are also found in traditionally Gaelic-speaking areas (the Gàidhealtachd, cognate with Irish Gaeltacht) of Scotland, such as An Linne Dhubh ("the black pool"), which is part of Loch Linnhe.

It is now thought that the Viking settlement was preceded by a Christian ecclesiastical settlement known as Duibhlinn, from which Dyflin took its name. Beginning in the 9th and 10th century, there were two settlements where the modern city stands. The Viking settlement of about 841 was known as Dyflin, from the Irish Duibhlinn, and a Gaelic settlement, Áth Cliath ("ford of hurdles") was further up river, at the present day Father Mathew Bridge (also known as Dublin Bridge), at the bottom of Church Street. Baile Átha Cliath, meaning "town of the hurdled ford", is the common name for the city in modern Irish. Áth Cliath is a place name referring to a fording point of the River Liffey near Father Mathew Bridge. Baile Átha Cliath was an early Christian monastery, believed to have been in the area of Aungier Street, currently occupied by Whitefriar Street Carmelite Church. There are other towns of the same name, such as Àth Cliath in East Ayrshire, Scotland, which is Anglicised as Hurlford.

The subsequent Scandinavian settlement centred on the River Poddle, a tributary of the Liffey in an area now known as Wood Quay. The Dubhlinn was a small lake used to moor ships; the Poddle connected the lake with the Liffey. This lake was covered during the early 18th century as the city grew. The Dubhlinn lay where the Castle Garden is now located, opposite the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin Castle. Táin Bó Cuailgne ("The Cattle Raid of Cooley") refers to Dublind rissa ratter Áth Cliath, meaning "Dublin, which is called Ath Cliath".

Middle Ages

Dublin was established as a Viking settlement in the 10th century and, despite a number of rebellions by the native Irish, it remained largely under Viking control until the Norman invasion of Ireland was launched from Wales in 1169.[17] The King of Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, enlisted the help of Strongbow, the Earl of Pembroke, to conquer Dublin. Following Mac Murrough's death, Strongbow declared himself King of Leinster after gaining control of the city. In response to Strongbow's successful invasion, King Henry II of England reaffirmed his sovereignty by mounting a larger invasion in 1171 and pronounced himself Lord of Ireland.[18] Around this time, the county of the City of Dublin was established along with certain liberties adjacent to the city proper. This continued down to 1840 when the barony of Dublin City was separated from the barony of Dublin. Since 2001, both baronies have been redesignated the City of Dublin.

Dublin Castle, which became the centre of Norman power in Ireland, was founded in 1204 as a major defensive work on the orders of King John of England.[19] Following the appointment of the first Lord Mayor of Dublin in 1229, the city expanded and had a population of 8,000 by the end of the 13th century. Dublin prospered as a trade centre, despite an attempt by King Robert I of Scotland to capture the city in 1317.[18] It remained a relatively small walled medieval town during the 14th century and was under constant threat from the surrounding native clans. In 1348, the Black Death, a lethal plague which had ravaged Europe, took hold in Dublin and killed thousands over the following decade.[20][21]

Dublin was incorporated into the English Crown as the Pale, which was a narrow strip of English settlement along the eastern seaboard. The Tudor conquest of Ireland in the 16th century spelt a new era for Dublin, with the city enjoying a renewed prominence as the centre of administrative rule in Ireland. Determined to make Dublin a Protestant city, Queen Elizabeth I of England established Trinity College in 1592 as a solely Protestant university and ordered that the Catholic St. Patrick's and Christ Church cathedrals be converted to Protestant.[22]

The city had a population of 21,000 in 1640 before a plague in 1649–51 wiped out almost half of the city's inhabitants. However, the city prospered again soon after as a result of the wool and linen trade with England, reaching a population of over 50,000 in 1700.[23]

Early modern

As the city continued to prosper during the 18th century, Georgian Dublin became, for a short period, the second largest city of the British Empire and the fifth largest city in Europe, with the population exceeding 130,000. The vast majority of Dublin's most notable architecture dates from this period, such as the Four Courts and the Custom House. Temple Bar and Grafton Street are two of the few remaining areas that were not affected by the wave of Georgian reconstruction and maintained their medieval character.[22]

Dublin grew even more dramatically during the 18th century, with the construction of many famous districts and buildings, such as Merrion Square, Parliament House and the Royal Exchange.[22] The Wide Streets Commission was established in 1757 at the request of Dublin Corporation to govern architectural standards on the layout of streets, bridges and buildings. In 1759, the founding of the Guinness brewery resulted in a considerable economic gain for the city.[citation needed] For much of the time since its foundation, the brewery was Dublin's largest employer.[citation needed]

Late modern and contemporary

Dublin suffered a period of political and economic decline during the 19th century following the Act of Union of 1800, under which the seat of government was transferred to the Westminster Parliament in London. The city played no major role in the Industrial Revolution, but remained the centre of administration and a transport hub for most of the island. Ireland had no significant sources of coal, the fuel of the time, and Dublin was not a centre of ship manufacturing, the other main driver of industrial development in Britain and Ireland.[17] Belfast developed faster than Dublin during this period on a mixture of international trade, factory-based linen cloth production and shipbuilding.[24]

The Easter Rising of 1916, the Irish War of Independence, and the subsequent Irish Civil War resulted in a significant amount of physical destruction in central Dublin. The Government of the Irish Free State rebuilt the city centre and located the new parliament, the Oireachtas, in Leinster House. Since the beginning of Norman rule in the 12th century, the city has functioned as the capital in varying geopolitical entities: Lordship of Ireland (1171–1541), Kingdom of Ireland (1541–1800), island as part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1801–1922), and the Irish Republic (1919–1922). Following the partition of Ireland in 1922, it became the capital of the Irish Free State (1922–1937) and now is the capital of Ireland. One of the memorials to commemorate that time is the Garden of Remembrance.

Dublin was also victim to the Northern Irish Troubles. While during this 30 year conflict, violence mainly engulfed Northern Ireland. However, the Provisional IRA drew a lot of support from the Republic, specifically Dublin. This caused a Loyalist paramilitary group the Ulster Volunteer Force to bomb the city. The most notable of atrocities carried out by loyalists during this time was the Dublin and Monaghan bombings in which 34 people died, mainly in Dublin itself.

Since 1997, the landscape of Dublin has changed immensely. The city was at the forefront of Ireland's rapid economic expansion during the Celtic Tiger period, with enormous private sector and state development of housing, transport and business.

Government

Local

From 1842, the boundaries of the city were comprehended by the baronies of Dublin City and the Barony of Dublin. In 1930, the boundaries were extended by the Local Government (Dublin) Act.[25] Later, in 1953, the boundaries were again extended by the Local Government Provisional Order Confirmation Act.[26]

Dublin City Council is a unicameral assembly of 63[27] members elected every five years from Local Election Areas. It is presided over by the Lord Mayor, who is elected for a yearly term and resides in Mansion House. Council meetings occur at Dublin City Hall, while most of its administrative activities are based in the Civic Offices on Wood Quay. The party or coalition of parties, with the majority of seats adjudicates committee members, introduces policies, and appoints the Lord Mayor. The Council passes an annual budget for spending on areas such as housing, traffic management, refuse, drainage, and planning. The Dublin City Manager is responsible for implementing City Council decisions.

National

As the capital city, Dublin seats the national parliament of Ireland, the Oireachtas. It is composed of the President of Ireland, Seanad Éireann as the upper house, and Dáil Éireann as the lower house. The President resides in Áras an Uachtaráin in the Phoenix Park, while both houses of the Oireachtas meet in Leinster House, a former ducal palace on Kildare Street. It has been the home of the Irish parliament since the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922. The old Irish Houses of Parliament of the Kingdom of Ireland are located in College Green.

Government Buildings house the Department of the Taoiseach, the Council Chamber, the Department of Finance and the Office of the Attorney General. It consists of a main building (completed 1911) with two wings (completed 1921). It was designed by Thomas Manley Dean and Sir Aston Webb as the Royal College of Science. The First Dáil originally met in the Mansion House in 1919. The Irish Free State government took over the two wings of the building to serve as a temporary home for some ministries, while the central building became the College of Technology until 1989.[28] Although both it and Leinster House were intended to be temporary, they became the permanent homes of parliament from then on.

For elections to Dáil Éireann the city is divided into five constituencies: Dublin Central (3 seats), Dublin Bay North (5 seats), Dublin North–West (3 seats), Dublin South–Central (4 seats) and Dublin Bay South (4 seats). Nineteen TD's are elected in total.[29]

Politics

In the past Dublin city was regarded as a stronghold for Fianna Fáil,[citation needed] however following the Irish local elections, 2004 the party was eclipsed by the centre-left Labour Party.[30] In the 2011 general election the Dublin Region elected 18 Labour Party, 17 Fine Gael, 4 Sinn Féin, 2 Socialist Party, 2 People Before Profit Alliance and 3 Independent TDs. Fianna Fáil lost all but one of its sitting TDs in the region.[31]

Geography

Landscape

Dublin is situated at the mouth of the River Liffey and encompasses a land area of approximately 44 sq mi, or 115 km2, in east-central Ireland. It is bordered by a low mountain range to the south and surrounded by flat farmland to the north and west.[32] The Liffey divides the city in two between the Northside and the Southside. Each of these is further divided by two lesser rivers – the River Tolka running southeast into Dubin Bay, and the River Dodder running northeast to the mouth of the Liffey. Two further water bodies – the Grand Canal on the southside and the Royal Canal on the northside – ring the inner city on their way from the west and the River Shannon.

The River Liffey bends at Leixlip from a northeasterly route to a predominantly eastward direction, and this point also marks the transition to urban development from more agricultural land usage.[33]

Cultural divide

A north-south division did traditionally exist, with the River Liffey as the divider. The Northside was generally seen as working class, while the Southside was seen as middle to upper-middle class. The divide was punctuated by examples of Dublin "sub-culture" stereotypes, with upper-middle class constituents seen as tending towards an accent and demeanour synonymous with the Southside, and working-class Dubliners seen as tending towards characteristics associated with Northside and inner-city areas. Dublin's economic divide was also previously an east-west as well as a north-south. There were also social divisions evident between the coastal suburbs in the east of the city, including those on the Northside, and the newer developments further to the west.[34]

Climate

| Dublin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Similar to much of the rest of northwestern Europe, Dublin experiences a maritime climate (Cfb) with cool summers, mild winters, and a lack of temperature extremes. The average maximum January temperature is 8.8 °C (48 °F), while the average maximum July temperature is 20.2 °C (68 °F). On average, the sunniest months are May and June, while the wettest month is October with 76 mm (3 in) of rain, and the driest month is February with 46 mm (2 in). Rainfall is evenly distributed throughout the year.

Ringsend in the south of the city records the least amount of rainfall in Ireland, with an average annual precipitation of 683 mm (27 in),[36] with the average annual precipitation in the city centre being 714 mm (28 in). The main precipitation in winter is rain; however snow showers do occur between November and March. Hail is more common than snow. The city experiences long summer days and short winter days. Strong Atlantic winds are most common in autumn. These winds can affect Dublin, but due to its easterly location it is least affected compared to other parts of the country. However, in winter, easterly winds render the city colder and more prone to snow showers.

| Climate data for Merrion Square, Dublin, (1981–2010 averages); extremes from all Dublin stations. | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.5 (65.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.8 (80.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.0 (87.8) |

27.6 (81.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

20.0 (68.0) |

18.1 (64.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.6 (67.3) |

17.3 (63.1) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.4 (43.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

16.9 (62.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

8.6 (47.5) |

6.9 (44.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.9 (39.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.2 (41.4) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

13.3 (55.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

8.8 (47.8) |

6.2 (43.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.2 (46.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.6 (3.9) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

1.8 (35.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−15.7 (3.7) |

−15.7 (3.7) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 62.6 (2.46) |

46.1 (1.81) |

51.8 (2.04) |

50.2 (1.98) |

57.9 (2.28) |

59.2 (2.33) |

50.5 (1.99) |

65.3 (2.57) |

56.7 (2.23) |

76.0 (2.99) |

69.4 (2.73) |

68.7 (2.70) |

714.6 (28.13) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 12 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 128 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 58.9 | 75.3 | 108.9 | 160.0 | 194.5 | 179.2 | 164.3 | 156.8 | 128.8 | 103.3 | 70.6 | 52.6 | 1,453.2 |

| Source 1: Met Éireann[37] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: European Climate Assessment & Dataset,[38] | |||||||||||||

Quarters

Dublin city is divided into several quarters or districts.

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (April 2016) |

Medieval Quarter

This is the oldest part of the city, which includes Dublin Castle, Christ Church and St Patrick's Cathedral along with the old city walls. It was part of the Dubh Linn settlement, this area became the home for the Vikings in Dublin.

Georgian Quarter

Dublin is renowned for its Georgian architecture. It boasts some of the world's finest Georgian buildings. It starts at St Stephen's Green and Trinity College up to the canal. Merrion Square, Saint Stephen's Green and Fitzwilliam Square are examples of this style of architecture.

Docklands Quarter

This area is Dublin Docklands which includes "Silicon Docks", Dublin's Tech Quarter located in the Grand Canal Dock area. Global giants such as Google, Facebook, Accenture and Twitter are based there. It used to be a derelict part of the city, but has undergone revitalisation with the development of offices and apartments.

Cultural Quarter

Temple Bar is at the heart of Dublin's social and cultural life. It was once derelict but was then revitalized in the 1990s. [39]

Creative Quarter

It is the newest district, created in 2012. It covers the area from South William Street to George's Street, and from Lower Stephen's Street to Exchequer Street. Its a hub of design, creativity and innovation. [40]

Places of interest

Landmarks

Dublin has many landmarks and monuments dating back hundreds of years. One of the oldest is Dublin Castle, which was first founded as a major defensive work on the orders of King John of England in 1204, shortly after the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169, when it was commanded that a castle be built with strong walls and good ditches for the defence of the city, the administration of justice, and the protection of the King's treasure.[41] Largely complete by 1230, the castle was of typical Norman courtyard design, with a central square without a keep, bounded on all sides by tall defensive walls and protected at each corner by a circular tower. Sited to the south-east of Norman Dublin, the castle formed one corner of the outer perimeter of the city, using the River Poddle as a natural means of defence.

One of Dublin's newest monuments is the Spire of Dublin, or officially titled "Monument of Light".[42] It is a 121.2-metre (398 ft) conical spire made of stainless steel and is located on O'Connell Street. It replaces Nelson's Pillar and is intended to mark Dublin's place in the 21st century. The spire was designed by Ian Ritchie Architects,[43] who sought an "Elegant and dynamic simplicity bridging art and technology". During the day it maintains its steel look, but at dusk the monument appears to merge into the sky. The base of the monument is lit and the top is illuminated to provide a beacon in the night sky across the city.

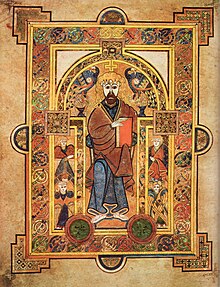

Many people visit Trinity College, Dublin to see the Book of Kells in the library there. The Book of Kells is an illustrated manuscript created by Irish monks circa. 800 AD. The Ha'penny Bridge; an old iron footbridge over the River Liffey is one of the most photographed sights in Dublin and is considered to be one of Dublin's most iconic landmarks.[44]

Other popular landmarks and monuments include the Mansion House, the Anna Livia monument, the Molly Malone statue, Christ Church Cathedral, St Patrick's Cathedral, Saint Francis Xavier Church on Upper Gardiner Street near Mountjoy Square, The Custom House, and Áras an Uachtaráin. The Poolbeg Towers are also iconic features of Dublin and are visible in many spots around the city.

Parks

Dublin has more green spaces per square kilometre than any other European capital city, with 97% of city residents living within 300 metres of a park area.[citation needed] The city council provides 2.96 hectares (7.3 acres) of public green space per 1,000 people and 255 playing fields.[citation needed] The council also plants approximately 5,000 trees annually[citation needed] and manages over 1,500 hectares (3,700 acres) of parks.[45]

There are many park areas around the city, including the Phoenix Park, Herbert Park and St Stephen's Green. The Phoenix Park is about 3 km (2 miles) west of the city centre, north of the River Liffey. Its 16-kilometre (10 mi) perimeter wall encloses 707 hectares (1,750 acres), making it one of the largest walled city parks in Europe.[46] It includes large areas of grassland and tree-lined avenues, and since the 17th century has been home to a herd of wild Fallow deer. The residence of the President of Ireland (Áras an Uachtaráin), which was built in 1751,[47] is located in the park. The park is also home to Dublin Zoo, the official residence of the United States Ambassador, and Ashtown Castle. Music concerts have also been performed in the park by many singers and musicians.

St Stephen's Green is adjacent to one of Dublin's main shopping streets, Grafton Street, and to a shopping centre named for it, while on its surrounding streets are the offices of a number of public bodies and the city terminus of one of Dublin's Luas tram lines. Saint Anne's Park is a public park and recreational facility, shared between Raheny and Clontarf, both suburbs on the North Side of Dublin. The park, the second largest municipal park in Dublin, is part of a former 2-square-kilometre (0.8 sq mi; 500-acre) estate assembled by members of the Guinness family, beginning with Benjamin Lee Guinness in 1835 (the largest municipal park is nearby (North) Bull Island, also shared between Clontarf and Raheny).

Economy

The Dublin region is the economic centre of Ireland, and was at the forefront of the country's rapid economic expansion during the Celtic Tiger period. In 2009, Dublin was listed as the fourth richest city in the world by purchasing power and 10th richest by personal income.[48][49] According to Mercer's 2011 Worldwide Cost of Living Survey, Dublin is the 13th most expensive city in the European Union (down from 10th in 2010) and the 58th most expensive place to live in the world (down from 42nd in 2010).[50] As of 2005[update], approximately 800,000 people were employed in the Greater Dublin Area, of whom around 600,000 were employed in the services sector and 200,000 in the industrial sector.[51][needs update]

Many of Dublin's traditional industries, such as food processing, textile manufacturing, brewing, and distilling have gradually declined, although Guinness has been brewed at the St. James's Gate Brewery since 1759. Economic improvements in the 1990s have attracted a large number of global pharmaceutical, information and communications technology companies to the city and Greater Dublin Area. Companies such as Microsoft, Google, Amazon, eBay, PayPal, Yahoo!, Facebook, Twitter, Accenture and Pfizer now have European headquarters and/or operational bases in the city.

Financial services have also become important to the city since the establishment of Dublin's International Financial Services Centre in 1987, which is globally recognised as a leading location for a range of internationally traded financial services. More than 500 operations are approved to trade in under the IFSC programme. The centre is host to half of the world's top 50 banks and to half of the top 20 insurance companies.[52] Many international firms have established major headquarters in the city, such as Citibank and Commerzbank. The Irish Stock Exchange (ISEQ), Internet Neutral Exchange (INEX) and Irish Enterprise Exchange (IEX) are also located in Dublin. The economic boom led to a sharp increase in construction, with large redevelopment projects in the Dublin Docklands and Spencer Dock. Completed projects include the Convention Centre, the 3Arena, and the Bord Gáis Energy Theatre and Silicon Docks.

Transport

Road

The road network in Ireland is primarily focused on Dublin. The M50 motorway, a semi-ring road which runs around the south, west and north of the city, connects important national primary routes to the rest of the country. In 2008, the West-Link toll bridge was replaced by the eFlow barrier-free tolling system, with a three-tiered charge system based on electronic tags and car pre-registration. The toll is currently €2.10 for vehicles with a pre-paid tag, €2.60 for vehicles whose number plates have been registered with eFlow, and €3.10 for unregistered vehicles.[53]

The first phase of a proposed eastern bypass for the city is the Dublin Port Tunnel, which officially opened in 2006 to mainly cater for heavy vehicles. The tunnel connects Dublin Port and the M1 motorway close to Dublin Airport. The city is also surrounded by an inner and outer orbital route. The inner orbital route runs approximately around the heart of the Georgian city and the outer orbital route runs primarily along the natural circle formed by Dublin's two canals, the Grand Canal and the Royal Canal, as well as the North and South Circular Roads.

Dublin is served by an extensive network of nearly 200 bus routes which serve all areas of the city and suburbs. The majority of these are controlled by Dublin Bus, but a number of smaller companies also operate. Fares are generally calculated on a stage system based on distance travelled. There are several different levels of fares, which apply on most services. A "Real Time Passenger Information" system was introduced at Dublin Bus bus stops in 2012. Electronically displayed signs relay information about the time of the next bus' arrival based on its GPS determined position. The National Transport Authority is responsible for integration of bus and rail services in Dublin and has been involved in introducing a pre-paid smart card, called a Leap card, which can be used on Dublin's public transport services.

Rail and tram

Heuston and Connolly stations are the two main railway stations in Dublin. Operated by Iarnród Éireann, the Dublin Suburban Rail network consists of five railway lines serving the Greater Dublin Area and commuter towns such as Drogheda and Dundalk in County Louth. One of these lines is the electrified Dublin Area Rapid Transit (DART) line, which runs primarily along the coast of Dublin, comprising a total of 31 stations, from Malahide and Howth southwards as far as Greystones in County Wicklow.[54] Commuter rail operates on the other four lines using Irish Rail diesel multiple units. In 2013, passengers for DART and Dublin Suburban lines were 16 million and 11.7 million, respectively (around 75% of all Irish Rail passengers).[55]

The Luas is a light rail system, run by Veolia Transport, has been operating since 2004 and now carries over 30 million passengers annually.[56] The network consists of two tram lines; the Red Line links the Docklands and city centre with the south-western suburbs, while the Green Line connects the city centre with suburbs to the south of the city and together comprise a total 54 stations and 38.2 kilometres (23.7 mi) of track.[57] Construction of a 6 km extension to the Green Line, bringing it to the north of the city, commenced in June 2013.[58]

Proposed multibillion-euro projects such as the Dublin Metro and the DART Underground will also be considered.

Rail and ferry

Dublin Connolly is connected by bus to Dublin Port and ferries run by Irish Ferries and Stena Line to Holyhead for connecting trains on the North Wales Coast Line to Chester, Crewe and London Euston.

Dublin Connolly to Dublin Port can be reached by walking beside the tram lines around the corner from Amiens Street, Dublin into Store Street or by Luas one stop to Busáras where Dublin Bus operates a service to the Ferry Terminal, or Dublin Bus route 53[59] or to take a taxi.

Airport

Dublin Airport is operated by the Dublin Airport Authority and is located north of Dublin City in the administrative county of Fingal. It is the headquarters of Ireland's flag carrier Aer Lingus, low-cost carrier Ryanair, and regional airlines Stobart Air and CityJet. The airport offers an extensive short and medium haul network, as well as domestic services to many regional airports in Ireland. There are also extensive Long Haul services to the United States, Canada and the Middle East. Dublin Airport is the busiest airport in Ireland, followed by Cork and Shannon. Construction of a second terminal began in 2007 and was officially opened on 19 November 2010.[60]

Dublin Airport currently ranks as the 18th busiest airport in Europe recording over 25 million passengers during 2015, and has been showing a very strong growth in passenger numbers in recent years, particularly in long haul routes. Dublin is now ranked 6th in Europe as a hub for transatlantic passengers, with 158 flights a week to the US, ahead of much bigger airports such as Istanbul and Rome.[citation needed]

Cycling

Dublin City Council began installing cycle lanes and tracks throughout the city in the 1990s, and as of 2012[update] the city has over 200 kilometres (120 miles) of specific on- and off-road tracks for cyclists.[61] In 2011, the city was ranked 9th of major world cities on the Copenhagenize Index of Bicycle-Friendly Cities.[62]

Dublinbikes is a self-service bicycle rental scheme which has been in operation in Dublin since 2009. Sponsored by JCDecaux, the scheme consists of 550 French-made unisex bicycles stationed at 44 terminals throughout the city centre. Users must make a subscription for either an annual Long Term Hire Card costing €20 or a 3 Day Ticket costing €2. The first 30 minutes of use is free, but after that a service charge depending on the extra length of use applies.[63] Dublinbikes now has over 58,000 subscribers and there are plans to dramatically expand the service across the city and its suburbs to provide for up to 5,000 bicycles and approximately 300 terminals.[64]

The 2011 Census revealed that 5.9 percent of commuters in Dublin cycled. A 2013 report by Dublin City Council on traffic flows crossing the canals in and out of the city found that just under 10% of all traffic was made up of cyclists, representing an increase of 14.1% over 2012 and a 87.2% increase over 2006 levels and is attributed to measures, such as, the Dublinbikes bike rental scheme, the provision of cycle lanes, public awareness campaigns to promote cycling and the introduction of the 30kph city centre speed limit.[65]

Higher education

Dublin is the primary centre of education in Ireland, it is home to three universities, Dublin Institute of Technology and many other higher education institutions. There are 20 third-level institutes in the city and in surrounding towns and suburbs. Dublin was European Capital of Science in 2012.[66][67] The University of Dublin is the oldest university in Ireland dating from the 16th century, and is located in the city centre. Its sole constituent college, Trinity College, was established by Royal Charter in 1592 under Elizabeth I and was closed to Roman Catholics until Catholic Emancipation. The Catholic hierarchy then banned Roman Catholics from attending it until 1970. It is situated in the city centre, on College Green, and has 15,000 students.

The National University of Ireland (NUI) has its seat in Dublin, which is also the location of the associated constituent university of University College Dublin (UCD), has over 30,000 students. UCD's main campus is at Belfield, about 5 km (3 mi) from the city centre in the southeastern suburbs.

With a continuous history dating back to 1887, Dublin's principal institution for technological education and research Dublin Institute of Technology (DIT) with over 23,000 students. Dublin Institute of Technology specialises in engineering, architecture, sciences, health, digital media, hospitality and business but also offers many art, design, music and humanities programmes. DIT currently has campuses, buildings and research facilities at multiple locations in central Dublin, it has commenced consolidation to a new city-centre campus in Grangegorman.

Dublin City University (DCU), formerly known as the National Institute for Higher Education (NIHE), specialises in business, engineering, science, communication courses, languages and primary education. It has around 16,000 students, and its main campus, the Glasnevin Campus, is located about 7 km (4 mi) from the city centre in the northern suburbs. It has two campuses on the Northside of the river, the DCU Glasnevin Campus and the DCU Drumcondra Campus. The Drumcondra campus includes students formally of the Glasnevin Campus, St Patrick's College of Education, the nearby Mater Dei Institute and from the beginning of the 2016/17 academic year students from the Church of Ireland College of Education. These colleges will be fully incorporated into DCU at the beginning of the 2016/17 academic year. [68]

The Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) is a medical school which is a recognised college of the NUI, it is situated at St. Stephen's Green in the city centre. The National University of Ireland, Maynooth, another constituent of the NUI, is in neighbouring Co. Kildare, about 25 km (16 mi) from the city centre. The Institute of European Affairs is also in Dublin. Portobello College has its degrees conferred through the University of Wales.[according to whom?] Dublin Business School (DBS) is Ireland's largest private third level institution with over 9,000 students located on Aungier Street. The National College of Art and Design (NCAD) supports training and research in art, design and media. The National College of Ireland (NCI) is also based in Dublin. The Economic and Social Research Institute, a social science research institute, is based on Sir John Rogerson's Quay, Dublin 2.

The Irish public administration and management training centre has its base in Dublin, the Institute of Public Administration provides a range of undergraduate and post graduate awards via the National University of Ireland and in some instances, Queen's University Belfast. There are also smaller specialised colleges, including Griffith College Dublin, The Gaiety School of Acting and the New Media Technology College.

Outside of the city, the towns of Tallaght in South Dublin and Dún Laoghaire in Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown have regional colleges: The Institute of Technology, Tallaght has full and part-time courses in a wide range of technical subjects and the Dún Laoghaire Institute of Art, Design and Technology (IADT) supports training and research in art, design, business, psychology and media technology. The western suburb of Blanchardstown offers childcare and sports management courses along with languages and technical subjects at the Institute of Technology, Blanchardstown.

Demographics

The City of Dublin is the area administered by Dublin City Council, but the term "Dublin" normally refers to the contiguous urban area which includes parts of the adjacent local authority areas of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Fingal and South Dublin. Together, the four areas form the traditional County Dublin. This area is sometimes known as the Dublin Region. The population of the administrative area controlled by the City Council was 525,383 in the 2011 census, while the population of the urban area was 1,110,627. The County Dublin population was 1,273,069 and that of the Greater Dublin Area 1,804,156. The area's population is expanding rapidly, and it is estimated by the Central Statistics Office that it will reach 2.1 million by 2020.[69]

Since the late 1990s, Dublin has experienced a significant level of net immigration, with the greatest numbers coming from the European Union, especially the United Kingdom, Poland and Lithuania.[70] There is also a considerable number of immigrants from outside Europe, particularly from India, Pakistan, China and Nigeria. Dublin is home to a greater proportion of new arrivals than any other part of the country. Sixty percent of Ireland's Asian population lives in Dublin.[71] Over 15% of Dublin's population was foreign-born in 2006.[72]

The capital attracts the largest proportion of non-Catholic migrants from other countries. Increased secularization in Ireland has prompted a drop in regular Catholic church attendance in Dublin from over 90 percent in the mid-1970s down to 14 percent according to a 2011 survey.[73]

Culture

The arts

Dublin has a world-famous literary history, having produced many prominent literary figures, including Nobel laureates William Butler Yeats, George Bernard Shaw and Samuel Beckett. Other influential writers and playwrights include Oscar Wilde, Jonathan Swift and the creator of Dracula, Bram Stoker. It is arguably most famous as the location of the greatest works of James Joyce, including Ulysses, which is set in Dublin and full of topical detail. Dubliners is a collection of short stories by Joyce about incidents and typical characters of the city during the early 20th century. Other renowned writers include J. M. Synge, Seán O'Casey, Brendan Behan, Maeve Binchy, and Roddy Doyle. Ireland's biggest libraries and literary museums are found in Dublin, including the National Print Museum of Ireland and National Library of Ireland. In July 2010, Dublin was named as a UNESCO City of Literature, joining Edinburgh, Melbourne and Iowa City with the permanent title.[74]

There are several theatres within the city centre, and various world famous actors have emerged from the Dublin theatrical scene, including Noel Purcell, Sir Michael Gambon, Brendan Gleeson, Stephen Rea, Colin Farrell, Colm Meaney and Gabriel Byrne. The best known theatres include the Gaiety, Abbey, Olympia, Gate, and Grand Canal. The Gaiety specialises in musical and operatic productions, and is popular for opening its doors after the evening theatre production to host a variety of live music, dancing, and films. The Abbey was founded in 1904 by a group that included Yeats with the aim of promoting indigenous literary talent. It went on to provide a breakthrough for some of the city's most famous writers, such as Synge, Yeats himself and George Bernard Shaw. The Gate was founded in 1928 to promote European and American Avant Garde works. The Grand Canal Theatre is a new 2,111 capacity theatre which opened in March 2010 in the Grand Canal Dock.

Apart from being the focus of the country's literature and theatre, Dublin is also the focal point for much of Irish art and the Irish artistic scene. The Book of Kells, a world-famous manuscript produced by Celtic Monks in AD 800 and an example of Insular art, is on display in Trinity College. The Chester Beatty Library houses the famous collection of manuscripts, miniature paintings, prints, drawings, rare books and decorative arts assembled by American mining millionaire (and honorary Irish citizen) Sir Alfred Chester Beatty (1875–1968). The collections date from 2700 BC onwards and are drawn from Asia, the Middle East, North Africa and Europe.

In addition public art galleries are found across the city, including the Irish Museum of Modern Art, the National Gallery, the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery, the Douglas Hyde Gallery, the Project Arts Centre and the Royal Hibernian Academy. In recent years Dublin has become host to a thriving contemporary art scene. Some of the leading private galleries include Green on Red Gallery, Kerlin Gallery, Kevin Kavangh Gallery and Mother's Tankstation, each of which focuses on facilitating innovative, challenging and engaging contemporary visual art practice.

Three branches of the National Museum of Ireland are located in Dublin: Archaeology in Kildare Street, Decorative Arts and History in Collins Barracks and Natural History in Merrion Street.[75] The same area is also home to many smaller museums such as Number 29 on Fitzwilliam Street and the Little Museum of Dublin on St. Stephen's Green. Dublin is home to the National College of Art and Design, which dates from 1746, and Dublin Institute of Design, founded in 1991. Dublinia is a living history attraction showcasing the Viking and Medieval history of the city.

Dublin has long been a city with a strong underground arts scene. Temple Bar was the home of many artists in the 1980s, and spaces such as the Project Arts Centre were hubs for collectives and new exhibitions. The Guardian noted that Dublin's independent and underground arts flourished during the economic recession of 2010.[76] Dublin also has many acclaimed dramatic, musical and operatic companies, including Festival Productions, Lyric Opera Productions, the Pioneers' Musical & Dramatic Society, the Glasnevin Musical Society, Second Age Theatre Company, Opera Theatre Company and Opera Ireland. Ireland is well known for its love of baroque music, which is highly acclaimed at Trinity College.[77]

Dublin was shortlisted to be World Design Capital 2014.[78] Taoiseach Enda Kenny was quoted to say that Dublin "would be an ideal candidate to host the World Design Capital in 2014".[79]

Entertainment

Dublin has a vibrant nightlife and is reputedly one of Europe's most youthful cities, with an estimate of 50% of citizens being younger than 25.[80][81] There are many pubs across the city centre, with the area around St. Stephen's Green and Grafton Street, especially Harcourt Street, Camden Street, Wexford Street and Leeson Street, having the most popular nightclubs and pubs.

The best known area for nightlife is Temple Bar, south of the River Liffey. The area has become popular among tourists, including stag and hen parties from Britain.[82] It was developed as Dublin's cultural quarter and does retain this spirit as a centre for small arts productions, photographic and artists' studios, and in the form of street performers and small music venues. However, it has been criticised as overpriced, false and dirty by Lonely Planet.[83] In 2014, Temple Bar was listed by the Huffington Post as one of the ten most disappointing destinations in the world.[84] The areas around Leeson Street, Harcourt Street, South William Street and Camden/George's Street are popular nightlife spots for locals.

Live music is popularly played on streets and at venues throughout Dublin, and the city has produced several musicians and groups of international success, including The Dubliners, Thin Lizzy, The Boomtown Rats, U2, Sinéad O'Connor, Boyzone, Westlife and Jedward. The two best known cinemas in the city centre are the Savoy Cinema and the Cineworld Cinema, both north of the Liffey. Alternative and special-interest cinema can be found in the Irish Film Institute in Temple Bar, in the Screen Cinema on D'Olier Street and in the Lighthouse Cinema in Smithfield. Large modern multiscreen cinemas are located across suburban Dublin. The 3Arena venue in the Dublin Docklands has played host to many world-renowned performers.

Shopping

Dublin is a popular shopping destination for both locals and tourists. The city has numerous shopping districts, particularly around Grafton Street and Henry Street. The city centre is also the location of large department stores, most notably Arnotts, Brown Thomas and Clerys (until June 2015 when it closed down).

The city retains a thriving market culture, despite new shopping developments and the loss of some traditional market sites. Amongst several historic locations, Moore Street remains one of the city's oldest trading districts.[85] There has also been a significant growth in local farmers' markets and other markets.[86][87] In 2007, Dublin Food Co-op relocated to a larger warehouse in The Liberties area, where it is home to many market and community events.[88][89] Suburban Dublin has several modern retail centres, including Dundrum Town Centre, Blanchardstown Centre, the Square in Tallaght, Liffey Valley Shopping Centre in Clondalkin, Omni Shopping Centre in Santry, Nutgrove Shopping Centre in Rathfarnham, and Pavilions Shopping Centre in Swords.

Media

Dublin is the centre of both media and communications in Ireland, with many newspapers, radio stations, television stations and telephone companies based there. RTÉ is Ireland's national state broadcaster, and is based in Donnybrook. Fair City is RTÉ's soap opera, located in the fictional Dublin suburb of Carraigstown. TV3 Media, UTV Ireland, Setanta Sports, MTV Ireland and Sky News are also based in the city. The headquarters of An Post and telecommunications companies such as Eircom, as well as mobile operators Meteor, Vodafone and 3 are all located there. Dublin is also the headquarters of important national newspapers such as The Irish Times and Irish Independent, as well as local newspapers such as The Evening Herald.

As well as being home to RTÉ Radio, Dublin also hosts the national radio networks Today FM and Newstalk, and numerous local stations. Commercial radio stations based in the city include 4fm (94.9 MHz), Dublin's 98FM (98.1 MHz), Radio Nova 100FM (100.3 MHz), Q102 (102.2 MHz), SPIN 1038 (103.8 MHz), FM104 (104.4 MHz), TXFM (105.2 MHz) and Sunshine 106.8 (106.8 MHz). There are also numerous community and special interest stations, including Dublin City FM (103.2 MHz), Dublin South FM (93.9 MHz), Liffey Sound FM (96.4 MHz), Near FM (90.3 MHz), Phoenix FM (92.5 MHz), Raidió na Life (106.4 MHz) and West Dublin Access Radio (96.0 MHz).

Sport

GAA

Croke Park is the largest sport stadium in Ireland. The headquarters of the Gaelic Athletic Association, it has a capacity of 84,500. It is the fourth largest stadium in Europe after Nou Camp in Barcelona, Wembley Stadium in London and Santiago Bernabéu Stadium in Madrid.[90] It hosts the premier Gaelic football and hurling games, international rules football and irregularly other sporting and non-sporting events including concerts. During the redevelopment of Lansdowne Road it played host to the Irish Rugby Union Team and Republic of Ireland national football team as well as hosting the Heineken Cup rugby 2008–09 semi-final between Munster and Leinster which set a world record attendance for a club rugby match.[91] The Dublin GAA team plays most of their home league hurling games at Parnell Park.

Rugby

I.R.F.U. Stadium Lansdowne Road was laid out in 1874. This was the venue for home games of both the Irish Rugby Union Team and the Republic of Ireland national football team. A joint venture between the Irish Rugby Football Union, the FAI and the Government, saw it redeveloped into a new state-of-the-art 50,000 seat Aviva Stadium, which opened in May 2010.[92] Aviva Stadium hosted the 2011 UEFA Europa League Final.[93] Rugby union team Leinster Rugby play their competitive home games in the RDS Arena & the Aviva Stadium while Donnybrook Stadium hosts their friendlies and A games, Ireland A and Women, Leinster Schools and Youths and the home club games of All Ireland League clubs Old Wesley and Bective Rangers. County Dublin is home for 13 of the senior rugby union clubs in Ireland including 5 of the 10 sides in the top division 1A.[94]

Football

County Dublin is home to six League of Ireland association clubs; Bohemian F.C., Shamrock Rovers, St Patrick's Athletic, University College Dublin, Shelbourne and newly elected side Cabinteely. Current FAI Cup Champions are St Patrick's Athletic.[95] The first Irish side to reach the group stages of a European competition (2011–12 UEFA Europa League group stage) are Shamrock Rovers[96] who play at Tallaght Stadium in South Dublin. Bohemian F.C play at Dalymount Park which is the oldest football stadium in the country, having played host to the Ireland football team from 1904 to 1990. St Patrick's Athletic play at Richmond Park, University College Dublin play their home games at the UCD Bowl in Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, while Shelbourne is based at Tolka Park.Cabinteely will play at Stradbrook Road. Tolka Park, Dalymount Park, UCD Bowl and Tallaght Stadium, along with the Carlisle Grounds in Bray, hosted all Group 3 games in the intermediary round of the 2011 UEFA Regions' Cup.[97]

Other

The Dublin Marathon has been run since 1980 on the last Monday in October. The Women's Mini Marathon has been run since 1983 on the first Monday in June, which is also a bank holiday in Ireland. It is said to be the largest all female event of its kind in the world.[98]

The Dublin area has several race courses including Shelbourne Park and Leopardstown. The Dublin Horse Show takes place at the RDS, which hosted the Show Jumping World Championships in 1982. The national boxing arena is located in The National Stadium on the South Circular Road. The National Basketball Arena is located in Tallaght, is the home of the Irish basketball team, is the venue for the basketball league finals and has also hosted boxing and wrestling events. The National Aquatic Centre in Blanchardstown is Ireland's largest indoor water leisure facility. Dublin has two ODI Cricket grounds in Castle Avenue, Clontarf and Malahide Cricket Club and College Park has Test status and played host to Ireland's only Test cricket match to date, a women's match against Pakistan in 2000.[99] There are also Gaelic Handball, hockey and athletics stadia, most notably Morton Stadium in Santry, which held the athletics events of the 2003 Special Olympics.

Irish language

There are 10,469 students in the Dublin region attending the 31 gaelscoileanna (Irish-language primary schools) and 8 gaelcholáistí (Irish-language secondary schools).[100] Dublin has the highest number of Irish-medium schools in the country. There may be also up to another 10,000 Gaeltacht speakers living in Dublin. Two Irish language radio stations Raidió Na Life and RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta both have studios in the city, and the online and DAB station Raidió Rí-Rá broadcasts from studios in the city. Many other radio stations in the city broadcast at least an hour of Irish language programming per week. Many Irish language agencies are also located in the capital. Conradh na Gaeilge offers language classes, has a book shop and is a regular meeting place for different groups. The closest Gaeltacht to Dublin is the County Meath Gaeltacht of Ráth Cairn and Baile Ghib which is 55 km (34 mi) away.

Twin cities

Dublin is twinned with the following places:[32][101]

| City | Nation | Since |

|---|---|---|

| San Jose | United States[102] | 1986 |

| Liverpool | United Kingdom[103] | 1986 |

| Barcelona | Spain[104][105] | 1998 |

| Beijing | China[106][107] | 2011 |

| Emmetsburg, Iowa | United States | 1961 |

The city is also in talks to twin with Rio de Janeiro,[108] and Mexican city Guadalajara.[109]

See also

References

- ^ "Dublin City Council, Dublin City Coat of Arms". Dublincity.ie. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "Census of Population 2011" (PDF). Preliminary Results. Central Statistics Office. 30 June 2011. p. 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Census of Population 2011". Population Density and Area Size by Towns by Size, Census Year and Statistic. Central Statistics Office. April 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ Greater Dublin Area

- ^ "Census of Population 2011" (PDF). Profile 1 - Town and Country. Central Statistics Office. 26 April 2012. p. 11. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Population of each Province, County and City, 2011". Central Statistics Office. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Global city GDP 2014". Brookings Institution. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ "The Growth and Development of Dublin". Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Primate City Definition and Examples". Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ^ "Dublin Region Facts - Dublin Chamber of Commerce". dubchamber.ie.

- ^ "Global Financial Centres Index 8" (PDF). Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ "The World According to GaWC 2008". Globalization and World Cities Research Network: Loughborough University. 3 June 2009. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ^ Holder, Alfred (1896). Alt-celtischer sprachschatz (in German). Leipzig: B. G. Teubner. col.1393. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "Placenames Database of Ireland: Duibhlinn/Devlin". Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "Placenames Database of Ireland: Béal Duibhlinne/Ballydivlin". Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "Placenames Database of Ireland: Duibhlinn/Difflin". Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ a b Davies, Norman (1999). The Isles: a history. London: Macmillan. p. 1222. ISBN 0-333-76370-X.

- ^ a b "A Brief History of Dublin, Ireland". Dublin.info. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ "The Story of Ireland". Brian Igoe (2009). p.49.

- ^ "Black Death". Joseph Patrick Byrne (2004). p.58. ISBN 0-313-32492-1

- ^ a b c "A Brief History of Dublin" (PDF). visitingdublin. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Dublin: a cultural history". Siobhán Marie Kilfeather (2005). Oxford University Press US. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-19-518201-4

- ^ Lyons, F.S.L. (1973). Ireland since the famine. Suffolk: Collins / Fontana. p. 880. ISBN 0-00-633200-5.

- ^ Irish Statute Book. Local Government (Dublin) Act

- ^ "Irish statute book, Local Government Provisional Order Confirmation Act, 1953". Irishstatutebook.ie. 28 March 1953. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "Local Elections 2014". Dublin City Council. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Department of the Taoiseach: Guide to Government Buildings (2005)

- ^ "Constituency Commission Report 2012". Constituency Commission. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "2004 Local Elections — Electoral Area Details". Elections Ireland. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "2011 General Election". Elections Ireland. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Dublin City Council: Facts about Dublin City". Dublin City Council. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ "Final Characterisation Report" (PDF). Eastern River Basin District. Sec. 7: Characterisation of the Liffey Catchment Area. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ "Northside vs Southside". Wn.com. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "Temperature – Climate – Met Éireann – The Irish Meteorological Service Online". Met.ie. 2 January 1979. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ^ "Climatology details for station DUBLIN (RINGSEND), IRELAND and index RR: Precipitation sum". European Climate Assessment & Dataset. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ^ Met Éireann - Irish Weather Extremes

- ^ "Climatological Information for Merrion Square, Ireland". European Climate Assessment & Dataset.

- ^ "Dublin Insider Tips - Get Off the Beaten Track with These Local Tips - Visit Dublin".

- ^ "Dublin Town - Creative Quarter - DublinTown - What's On, Shopping & Events in Dublin City - Dublin Town". What's On, Shopping & Events in Dublin City - Dublin Town.

- ^ McCarthy, Denis; Benton, David (2004). Dublin Castle: at the heart of Irish History. Dublin: Irish Government Stationery Office. pp. 12–18. ISBN 0-7557-1975-1.

- ^ "Spire cleaners get prime view of city". Irish Independent. 5 June 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

- ^ "The Dublin Spire". Archiseek. 2003. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "Some Famous Landmarks of Dublin – Dublin Hotels & Travel Guide". Traveldir.org. 8 March 1966. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "Dublin City Parks". Dublin City Council. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ It is over twice the size of New York's Central Park. "About – Phoenix Park". Office of Public Works. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ "Outline History of Áras an Uachtaráin". Áras an Uachtaráin. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ "Richest cities in the world by purchasing power in 2009". City Mayors. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ "Richest cities in the world by personal earnings in 2009". Citymayors.com. 22 August 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ "Dublin falls in city-cost rankings". Irish Times. 12 July 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ Dublin employment at the Internet Archive PDF (256 KB) Archived 2013-03-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "I.F.S.C". I.F.S.C.ie. 21 June 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ "E-Flow Website". eFlow. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "DART (Dublin Area Rapid Transit)". Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ "Passenger Journeys by Rail by Type of Journey and Year - StatBank - data and statistics". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ "Luas - Frequently Asked Questions". luas.ie.

- ^ "Luas – Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Luas Cross City". Projects & Investment. Irish Rail. August 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ "53 - Dublin Bus". dublinbus.ie.

- ^ "Opening date for Terminal 2 set". RTÉ. 21 October 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Cycling Maps". Dublincitycycling.ie. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "Copenhagenize Consulting – ''Copenhagenize Index of Bicycle-Friendly Cities 2011''". Copenhagenize.eu. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "Dublinbikes – How does it work?". Dublinbikes. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Dublinbikes Strategic Planning Framework 2011–2016" (PDF). Dublin City Council. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Report on trends in mode share of vehicles and people crossing the Canal Cordon 2006 to 2013" (PDF). Dublin City Council & National Transport Authority. 2013. pp. 4, 8, 16. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "ESOF Dublin". EuroScience. 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Walshe, John; Reigel, Ralph (25 November 2008). "Celebrations and hard work begin after capital lands science 'Olympics' for 2012". Irish Independent. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ "DCU incorporation of CICE, St Pats and Mater Dei". DCU. 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Call for improved infrastructure for Dublin 2 April 2007

- ^ "Dublin heralds a new era in publishing for immigrants". The Guardian 12 March 2006.

- ^ Foreign nationals now 10% of Irish population 26 July 2007

- ^ "Dublin". OPENCities, a British Council project. Archived 2013-03-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Catholic Church’s Hold on Schools at Issue in Changing Ireland The New York Times, January 21, 2016

- ^ Irish Independent – Delight at City of Literature accolade for Dublin. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ "National Museum of Ireland". Museum.ie. 8 June 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ Conway, Richard (22 November 2010). "Dublin's independent arts scene is a silver lining in the recession-hit city". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Baroque Music in Dublin, Ireland".

- ^ "RTÉ report on World Design Capital shortlist". RTÉ News. 21 June 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ McDonald, Frank (22 June 2011). "Dublin on shortlist to be 'World Design Capital'". Irish Times. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ "The Irish Experience". The Irish Experience. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ "Dublin Guide, Tourist Information, Travel Planning, Tours, Sightseeing, Attractions, Things to Do". TalkingCities.co.uk. 6 October 2009. Archived from the original on 29 August 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 6 October 2009 suggested (help) - ^ Article on stag/hen parties in Edinburgh, Scotland (which mentions their popularity in Dublin), mentioning Dublin. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ "New Lonely Planet guide slams Ireland for being too modern, Ireland Vacations". IrishCentral. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ Morse, Caroline (4 April 2014). "10 Most Disappointing Destinations in the World". Huffington Post. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ Doyle, Kevin (17 December 2009). "Let us open up for Sunday shoppers says Moore Street". The Herald. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ^ McKenna, John (7 July 2007). "Public appetite for real food". The Irish Times. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ^ Van Kampen, Sinead (21 September 2009). "Miss Thrifty: Death to the shopping centre!". The Irish Independent. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ^ Mooney, Sinead (7 July 2007). "Food Shorts". The Irish Times. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ^ Dublin Food Co-op website ref. Markets / News and Events / Recent Events / Events Archive

- ^ "Main site – Facts and figures". Crokepark.ie. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "World record crowd watches Harlequins sink Saracens". The Sydney Morning Herald. 1 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "Taoiseach Officially Opens Aviva Stadium". IrishRugby.ie. 14 May 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "Homepage of Lansdowne Road Development Company (IRFU and FAI JV)". Lrsdc.Ie. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ |url=http://www.irishrugby.ie/ulsterbankleague/tables.php |date=20130804012925 |df=y Irish Rugby : Club & Community : Ulster Bank League : Ulster Bank League Tables Error in Webarchive template: Empty url.

- ^ "Irish Daily Mail FAI Senior Cup". fai.ie.

- ^ Shamrock Rovers F.C.#European record

- ^ 2011 UEFA Regions' Cup#Group 3

- ^ "History". VHI Women's Mini Marathon. 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "Ireland Women v Pakistan Women, 2000, Only Test". CricketArchive. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ "Oideachas Trí Mheán na Gaeilge in Éirinn sa Ghalltacht 2010–2011" (PDF) (in Irish). gaelscoileanna.ie. 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ "Dublin City Council: International Relations Unit". Dublin City Council. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ "Sister City Program". City of San José. 19 June 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ "Liverpool City Council twinning". Liverpool.gov.uk. 17 November 2008. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 6 July 2010 suggested (help) - ^ "Ciutats agermanades, Relacions bilaterals, L'acció exterior". CIty of Barcelona. 18 June 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ "Barcelona City Council signs cooperation agreements with Dublin, Seoul, Buenos Aires and Hong Kong". Ajuntament de Barcelona. 26 November 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ "Dublin signs twinning agreement with Beijing". Dublin City Council. 2 June 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ Coonan, Clifford (3 June 2011). "Dublin officially twinned with Beijing". Irish Times. Retrieved 8 July 2014.(subscription required)

- ^ Coonan, Clifford (21 May 2011). "Dublin was also in talks with Rio de Janeiro in Brazil about twinning with that city". irishtimes.com. Retrieved 1 June 2011.(subscription required)

- ^ "Mexican city to be twinned with Dublin, says Lord Mayor". irishtimes.com. 21 March 2013. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)(subscription required)

Further reading

- John Flynn and Jerry Kelleher, Dublin Journeys in America (High Table Publishing, 2003) ISBN 0-9544694-1-0

- Hanne Hem, Dubliners, An Anthropologist's Account, Oslo, 1994

- Pat Liddy, Dublin A Celebration – From the 1st to the 21st century (Dublin City Council, 2000) ISBN 0-946841-50-0

- Maurice Craig, The Architecture of Ireland from the Earliest Times to 1880 (Batsford, Paperback edition 1989) ISBN 0-7134-2587-3

- Frank McDonald, Saving the City: How to Halt the Destruction of Dublin (Tomar Publishing, 1989) ISBN 1-871793-03-3

- Edward McParland, Public Architecture in Ireland 1680–1760 (Yale University Press, 2001) ISBN 0-300-09064-1

External links

- Dublin City Council – Official website of the local authority for Dublin

- Dublin Tourist Board – Official tourism site

- Transport for Ireland – Public transport website

- Sampling Dublin's Theater Scene – slideshow by The New York Times

- Alternative Dublin Guide Hidden-Dublin Guide

- Dublin UNESCO City of Literature official site

- Irish Video Website Dublin & National

- Gaelscoil stats

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- Dublin (city)

- 841 establishments

- Capitals in Europe

- Cities in the Republic of Ireland

- County towns in the Republic of Ireland

- Leinster

- Local administrative units of the Republic of Ireland

- Populated coastal places in the Republic of Ireland

- Port cities and towns of the Irish Sea

- Staple ports

- University towns in Ireland

- Viking Age populated places

- Populated places established in the 9th century