Travancore

Kingdom of Travancore | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1729–1949 | |||||||||

| Anthem: Vanchishamangalam (Hail the Lord of Vanchi!) | |||||||||

Kingdom of Travancore in India | |||||||||

| Status | Princely State of British India | ||||||||

| Capital | Padmanabhapuram (1729–1795) Trivandrum (1795–1949) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Malayalam, Tamil | ||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||

• 1729–1758 (first) | Marthanda Varma | ||||||||

• 1829–1846 (peak) | Swathi Thirunal | ||||||||

• 1931–1949 (last) | Chithira Thirunal | ||||||||

| Resident | |||||||||

• 1788–1800 (first) | George Powney | ||||||||

• 1800–1810 | Colin Macaulay | ||||||||

• 1840–1860 (peak) | William Cullen | ||||||||

• 1947 (last) | Cosmo Grant Niven Edwards | ||||||||

| Historical era | Age of Imperialism | ||||||||

• Established | 1729 | ||||||||

• vassal under British Raj | 1795 | ||||||||

• vassal under independent India | 1947 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1949 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1941 | 19,844 km2 (7,662 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1941 | 6,070,018 | ||||||||

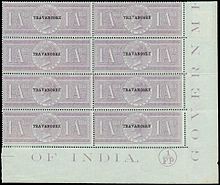

| Currency | Travancore rupee | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||

The Kingdom of Travancore (/ˈtrævənkɔːr/ Malayalam: തിരുവിതാംകൂർ/ Tamil: திருவிதாங்கூர்) was an Indian kingdom from c. 1729 until 1949. It was ruled by the Travancore Royal Family from Padmanabhapuram, and later Thiruvananthapuram. At its zenith, the kingdom covered most of modern-day southern Kerala, parts of central Kerala, and the southernmost part of modern-day Tamil Nadu (Kanyakumari district) with the Thachudaya Kaimal's enclave of Irinjalakuda Koodalmanikyam temple in the neighbouring Kingdom of Cochin.[1]

Flag: The official flag of the state was red with a dextrally-coiled silver conch shell (Turbinella pyrum) at its center.

Coat of arms: The coat of arms had two elephants standing on the left and right with the conch shell (Turibinella pyrum) in the center. The ribbon (white) with black Devanagari script.

King Marthanda Varma inherited the small feudal state of Venad in 1723 and built it into Travancore, one of the most powerful kingdoms in southern India. Marthanda Varma led the Travancore forces during the Travancore-Dutch War of 1739–46, which culminated in the Battle of Colachel. The defeat of the Dutch by Travancore is considered the earliest example of an organised power from Asia overcoming European military technology and tactics.[2] Marthanda Varma went on to conquer most of the petty principalities of the native rulers .

In the early 19th century, the kingdom became a princely state of the British Empire. The Travancore Government took many progressive steps on the socio-economic front and during the reign of Maharajah Sri Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma, Travancore became a prosperous modern princely state in British India, with reputed achievements in education, political administration, public work, and social reforms.[3][4] In 1903–1904 the total revenue of the state was Rs.1,02,01,900.[5]

Etymology

The regions had many small independent kingdoms. Later, during the peak time of Chera-Chola-Pandya, this region became a part of the Chera Kingdom (except for the Ay kingdom which always remained independent). During that era, when the region was part of the Chera empire, it was still known as Thiruvazhumkode. It was contracted to Thiruvankode, and anglicised by the English to Travancore.[6][7][8]

In course of time, the Ay kingdom, part of the Chera empire, which ruled the Thiruvazhumkode area, became independent, and the land was called Aayi Desam or Aayi Rajyam, meaning 'Aayi territory'. The Aayis controlled the land from present-day Kollam district in the north, through Thiruvananthapuram district, all in Kerala, to the Kanyakumari district. There were two capitals, the major one at Kollam (Venad Swaroopam or Desinganadu) and a subsidiary one at Thrippapur (Thrippapur Swaroopam or Nanjinad). The kingdom was thus also called Venad. Kings of Venad had, at various times, travelled from Kollam and built residential palaces in Thiruvithamcode and Kalkulam. Thiruvithamcode became the capital of the Thrippapur Swaroopam, and the country was referred to as Thiruvithamcode by Europeans even after the capital had been moved in 1601 to Padmanabhapuram, near Kalkulam.[9]

The Chera empire had dissolved by around 1100 and thereafter the territory comprised numerous small kingdoms until the time of Marthanda Varma who, as king of Venad from 1729, employed brutal methods to unify them.[10] During his reign, Thiruvithamcode or Travancore became the official name.[citation needed]

Geography

-

Map of Travancore in 1871.

-

A Canal scene in Travancore.

The Kingdom of Travancore was located at the extreme southern tip of the Indian subcontinent. Geographically, Travancore was divided into three climatically distinct regions: the eastern highlands (rugged and cool mountainous terrain), the central midlands (rolling hills), and the western lowlands (coastal plains).[citation needed]

History

Venad Swaroopam

Venad was a former state at the tip of the Indian Subcontinent, traditionally ruled by rajas known as the Venattadis. Till the end of the 11th century AD, it was a small principality in the Ay Kingdom. The Ays were the earliest ruling dynasty in southern Kerala, who, at their zenith, ruled over a region from Nagercoil in the south to Trivandrum in the north. Their capital during the first Sangam age was in Aykudi and later, towards the end of the 8th century AD, was at Quilon(Kollam). Though a series of attacks by the resurgent Pandyas between the 7th and 8th centuries caused the decline of the Ays, the dynasty was powerful till the beginning of the 10th century.[11]

When the Ay power diminished, Venad became the southernmost principality of the Second Chera Kingdom.[12] An invasion of the Cholas into Venad caused the destruction of Kollam in 1096. However, the Chera capital, Mahodayapuram, also fell in the subsequent Chola attack, which compelled the Chera king, Rama Varma Kulasekara, to shift his capital to Kollam.[13] Thus, Rama Varma Kulasekara, the last emperor of the Chera dynasty, is probably the founder of the Venad royal house, and the title of the Chera kings, Kulasekara, was thenceforth kept by the rulers of Venad. Thus the end of the Second Chera dynasty in the 12th century marks the independence of Venad.[14]

In the second half of the 12th century, two branches of the Ay Dynasty, Thrippappur and Chirava, merged in the Venad family, which set up the tradition of designating the ruler of Venad as Chirava Moopan and the heir-apparent as Thrippappur Moopan. While the Chrirava Moopan had his residence at Kollam, the Thrippappur Moopan resided at his palace in Thrippappur, 9 miles north of Thiruvananthapuram, and was vested with the authority over the temples of Venad kingdom, especially the Sri Padmanabhaswamy temple.[12]

Formation and development of Travancore

The history of Travancore began with Marthanda Varma, who inherited the kingdom of Venad (Thrippappur), and expanded it into Travancore during his reign (1729–1758). After defeating a union of feudal lords and establishing internal peace, he expanded the kingdom of Venad through a series of military campaigns from Kanyakumari in the south to the borders of Kochi in the north during his 29-year rule.[15] This rule also included Travancore-Dutch War (1739–1753) between the Dutch East India Company who had been allied to some of these kingdoms and Travancore.[citation needed]

In 1741, Travancore won the Battle of Colachel against the Dutch East India Company, resulting in the complete eclipse of Dutch power in the region. In this battle, the Dutch Captain, Eustachius De Lannoy, was captured. He later defected to Travancore.[16]

De Lannoy was appointed as Captain of His Highness' Body-guard[16] and later Senior Admiral ("Valiya kappittan")[17] and he modernised the Travancore army by introducing firearms and artillery.[16] From 1741 to 1758, De Lannoy remained in command of the Travancore Forces and was involved in annexation of small principalities.[18]

Travancore became the most dominant state in the Kerala region by defeating the powerful Zamorin of Kozhikode in the battle of Purakkad in 1755.[17] Ramayyan Dalawa, the Prime Minister (1737–1756) of Marthanda Varma, also played an important role in this consolidation and expansion.

On 3 January 1750, (5 Makaram, 925 Kollavarsham), Marthanda Varma virtually "dedicated" Travancore to his tutelary deity Padmanabha, one of the aspects of the Hindu God Vishnu with a lotus issuing from his navel on which Brahma sits. From then on the rulers of Travancore ruled as the "servants of Padmanabha" (the Padmnabha-dasar).[19]

At the Battle of Ambalapuzha, Marthanda Varma defeated the union of the kings who had been deposed and the king of the Cochin kingdom.[citation needed]

The Mysore invasion

Marthanda Varma's successor Karthika Thirunal Rama Varma (1758–1798), who was popularly known as Dharma Raja, shifted the capital in 1795 from Padmanabhapuram to Thiruvananthapuram. Dharma Raja's period is considered as a Golden Age in the history of Travancore. He not only retained the territorial gains of his predecessor Marthanda Varma, but also improved and encouraged social development. He was greatly assisted by a very efficient administrator, Raja Kesavadas, who was the Diwan of Travancore. [citation needed]

Travancore often allied with the English East India Company in military conflicts.[3] During Dharma Raja's reign, Tipu Sultan, the de facto ruler of Mysore and the son of Hyder Ali, attacked Travancore in 1789 as a part of the Mysore invasion of Kerala. Dharma Raja had earlier refused to hand over the Hindu political refugees from the Mysore occupation of Malabar, who had been given asylum in Travancore. The Mysore army entered the Cochin kingdom from Coimbatore in November 1789 and reached Trichur in December. On 28 December 1789 Tipu Sultan attacked the Nedunkotta (Northern Lines) from the north, causing the Battle of the Nedumkotta (1789), resulting in the defeat of Mysore army. In the battle, the bravery of 20 Travancore soldiers is very much appreciable. Tipu lost many soldiers and also one of his commanders in the battle. [citation needed]

Velu Thampi Dalawa's rebellion

On Dharma Raja's death in 1798, Balarama Varma (1798–1810), the weakest ruler of the dynasty, took over crown at the age of sixteen. A treaty brought Travancore under East India Company protection in 1795.[3]

The Prime Ministers (Dalawas or Dewans) started taking control of the kingdom beginning with Velu Thampi Dalawa (Velayudhan Chempakaraman Thampi) (1799–1809) who was appointed as the divan following the dismissal of Jayanthan Sankaran Nampoothiri (1798–1799). Initially, Velayudhan Chempakaraman Thampi and the English East India Company got along very well. When a section of the Travancore army mutinied in 1805 against Velu Thampi Dalawa, he sought refuge with the British Resident and later used English East India Company troops to crush the mutiny. Velu Thampi also played a key role in renegotiating a new treaty between Travancore and the English East India Company. However, the demands by the East India Company for the payment of compensation for their involvement in the Travancore-Mysore War (1791) on behalf of Travancore, led to tension between the Diwan and the East India Company Resident. Velu Thampi and the diwan of Cochin kingdom, Paliath Achan Govindan Menon, who was unhappy with the Resident for granting asylum to his enemy Kunhi Krishna Menon, declared "war" on the East India Company. [citation needed]

The East India Company army defeated Paliath Achan's army in Cochin on 27 February 1809. Paliath Achan surrendered to the East India Company and was exiled to Madras and later to Benaras. The Company defeated forces under Velu Thampi Dalawa at battles near Nagercoil and Kollam and inflicted heavy casualties on the rebels, following which many of his supporters deserted and went back to their homes. The Maharajah of Travancore, who hitherto had not taken any part in the rebellion openly, now allied with the British and appointed one of Thampi's enemies as his Prime Minister. The allied East India Company army and the Travancore soldiers camped in Pappanamcode, just outside Trivandrum. Velu Thampi Dalawa now organised a guerrilla struggle against the Company, but committed suicide to avoid capture by the Travancore army. After the mutiny of 1805 against Velu Thampi Dalawa, most of the Nair army battalions of Travancore had been disbanded, and after Velu Thampi Dalawa's uprising, almost all of the remaining Travancore forces were also disbanded, with the East India Company undertaking to serve the king in cases of external and internal aggression. [citation needed]

Cessation of mahādanams

The kings of Travancore had been conditionally promoted to Kshatryahood with periodic performance of 16 mahādānams (great gifts in charity) such as Hiranya-garbhā, Hiranya-Kāmdhenu, and Hiranyāswaratā in which each of which thousands of Brahmins had been given costly gifts apart from each getting a minimum of 1 kazhanch (78.65 gm) of gold.[20] In 1848 the Marquess of Dalhousie, then Governor-General of British India, was apprised that the depressed condition of the finances in Travancore was due to the mahādanams by the rulers.[21] Lord Dalhousie instructed Lord Harris, Governor of the Madras Presidency, to warn the then King of Travancore, Martanda Varma (Uttram Tirunal 1847–60), that if he did not put a stop to this practice, the Madras Presidency would take over his Kingdom's administration. This led to the cessation of the practice of mahādanams. [citation needed]

All Travancore kings including Sree Moolam Thirunal conducted the Hiranyagarbham and Tulapurushadaanam ceremonies. Maharajah Chithira Thirunal was the only King of Travancore not to have conducted these rituals as he considered them extremely costly.[22]

19th and early 20th centuries

In Travancore, the caste system was more rigorously enforced than in many other parts of India up to the mid-1800s. The rule of discriminative hierarchical caste order was deeply entrenched in the social system and was supported by the government, which had transformed this caste-based social system into a religious institution.[23] In such a context, the belief in Ayyavazhi, apart from being a religious system, served also as a reform movement in uplifting the downtrodden section of the society, both socially and as well religiously. The rituals of Ayyavazhi constituted a social discourse. Its beliefs, mode of worship, and religious organisation seem to have enabled the Ayyavazhi group to negotiate and cope with, and resist the imposition of authority.[24] The hard tone of Vaikundar towards this was perceived as a revolution against the government.[25] So the King Swathi Thirunal Rama Varma initially imprisoned Vaikundar in the Singarathoppu jail, where the jailor Appaguru ended up as a disciple of Vaikundar. Vaikundar was later set at liberty by the King.[26]

-

Travancore's postal service adopted a standard cast iron pillar box, made by Massey & Co in Madras, and similar to the British Penfold model that was introduced in 1866. This Anchal post box is in Perumbavoor.

-

Ayilyam Thirunal of Travancore (centre) with the first prince (left) and Dewan Rajah Sir T. Madhava Rao (right).

-

The last King of Travancore, Sree Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma.

-

Travancore Nair Brigade in 1861.

After the death of Sree Moolam Thirunal in 1924, Sethu Lakshmi Bayi became the regent (1924–1931), as the Heir Apparent Sree Chithira Thirunal was then a minor (12 years old).[27]

In 1935, Travancore joined the Indian State Forces Scheme and a Travancore unit was named 1st Travancore Nair Infantry, Travancore State Forces. The unit was reorganised as an Indian State Infantry Battalion by Lieutenant Colonel H S Steward who was appointed Commandant of the Travancore State Forces.[28]

The last ruling king of Travancore was Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma, who reigned from 1931 to 1949. "His reign marked revolutionary progress in the fields of education, defence, economy and society as a whole."[29] He made the famous Temple Entry Proclamation on 12 November 1936, which opened all the Kshetrams (Hindu temples in Kerala) in Travancore to all Hindus, a privilege reserved to only upper-caste Hindus till then. This act won him praise from across India, most notably from Mahatma Gandhi. The first public transport system (Thiruvananthapuram–Mavelikkara) and telecommunication system (Thiruvananthapuram Palace–Mavelikkara Palace) were launched during the reign of Sree Chithira Thirunal. He also started the industrialisation of the state, enhancing the role of the public sector. He introduced heavy industry in the State and established giant public sector undertakings. As many as twenty industries were established, mostly for utilizing the local raw materials such as rubber, ceramics, and minerals. A majority of the premier industries running in Kerala even today, were established by Sree Chithira Thirunal. He patronized musicians, artists, dancers, and Vedic scholars. Sree Chithira Thirunal appointed, for the first time, an Art Advisor to the Government, Dr. G. H. Cousins. He also established a new form of University Training Corps, viz. Labour Corps, preceding the N.C.C, in the educational institutions. The expenses of the University were to be met fully by the Government. Sree Chithira Thirunal also built a beautiful palace named Kowdiar Palace, finished in 1934, which was previously an old Naluektu, given by Sree Moolam Thirunal to his mother Sethu Parvathi Bayi in 1915.[30][31][32]

However, his Prime Minister, Sir C. P. Ramaswami Iyer, was unpopular among the communists of Travancore. The tension between the Communists and Sir C.P. Ramaswami Iyer led to minor riots in various places of the country. In one such riot in Punnapra-Vayalar in 1946, the Communist rioters established their own government in the area. This was put down by the Travancore Army and Navy. The Prime Minister issued a statement in June 1947 that Travancore would remain as an independent country instead of joining the Indian Union; subsequently, an attempt was made on the life of Sir C.P. Ramaswamy Iyer, following which he resigned and left for Madras, to be succeeded by Sri P.G.N. Unnithan. According to witnesses such as K.Aiyappan Pillai, constitutional adviser to the Maharaja and historians like A. Sreedhara Menon, the rioters and mob-attacks had no bearing on the decision of the Maharaja.[33][34] After several rounds of discussions and negotiations between Sree Chithira Thirunal and V.P. Menon, the King agreed that the Kingdom should accede to the Indian Union in 1949. On 1 July 1949 the Kingdom of Travancore was merged with the Kingdom of Cochin and the short-lived state of Travancore-Kochi was formed.[citation needed]

On 11 July 1991, Sree Chithira Thirunal suffered a stroke and was admitted to Sree Chithira Thirunal hospital, where he died on 20 July. He had ruled Travancore for 67 years and at his death was one of the few surviving rulers of a first-class princely state in the old British Raj. He was also the last surviving Knight Grand Commander of both the Order of the Star of India and of the Order of the Indian Empire. He was succeeded as head of the Royal House as well as the Titular Maharajah of Travancore by his brother, Uthradom Thirunal Marthanda Varma. The Government of India issued a stamp on Nov 6, 1991, commemorating the reforms that marked the reign of Maharajah Sree Chithira Thirunal in Travancore.[35]

Formation of Kerala

The State of Kerala came into existence on 1 November 1956, with a Governor appointed by the President of India as the head of the State instead of the King. [citation needed] The King was stripped of all his political powers and the right to receive privy purses, according to the twenty-sixth amendment of the Indian constitution act of 31 July 1971. He died on 20 July 1991.[36]

Politics

Under the direct control of the king, Travancore's administration was headed by a Dewan assisted by the Neetezhutthu Pillay or secretary, Rayasom Pillay (assistant or under-secretary) and a number of Rayasoms or clerks along with Kanakku Pillamars (accountants). Individual districts were run by Sarvadhikaris under supervision of the Diwan, while dealings with neighbouring states and Europeans was under the purview of the Valia Sarvahi, who signed treaties and agreements.[37]

Rulers of Travancore

- Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma 1729–1758[38]

- Karthika Thirunal Rama Varma (Dharma Raja) 1758–1798

- Balarama Varma I 1798–1810

- Gowri Lakshmi Bayi 1810–1815 (Queen from 1810 to 1813 and Regent Queen from 1813 to 1815)

- Gowri Parvati Bayi (Regent) 1815–1829

- Swathi Thirunal Rama Varma II 1813–1846

- Uthradom Thirunal Marthanda Varma II 1846–1860

- Ayilyam Thirunal Rama Varma III 1860–1880

- Visakham Thirunal Rama Varma IV 1880–1885

- Sree Moolam Thirunal Rama Varma VI 1885–1924

- Sethu Lakshmi Bayi (Regent) 1924–1931

- Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma II 1924–1949

Prime Ministers of Travancore

Dalawas

- Arumukham Pillai 1729–1736[citation needed]

- Thanu Pillai 1736–1737

- Ramayyan Dalawa 1737–1756

- Martanda Pillai 1756–1763

- Warkala Subbayyan 1763–1768

- Krishna Gopalayyan 1768–1776

- Vadiswaran Subbrahmanya Iyer 1776–1780

- Mullen Chempakaraman Pillai 1780–1782

- Nagercoil Ramayyan 1782–1788

- Krishnan Chempakaraman 1788–1789

- Raja Kesavadas 1789–1798

- Odiery Jayanthan Sankaran Nampoothiri 1798–1799

- Velu Thampi Dalawa 1799–1809

- Oommini Thampi 1809–1811

Dewans

- Col. John Munro 1811–1814[citation needed]

- Devan Padmanabhan Menon 1814–1814

- Bappu Rao (acting) 1814–1815

- Sanku Annavi Pillai 1815–1815

- Raman Menon 1815–1817

- Reddy Rao 1817–1821

- T. Venkata Rao 1821–1830

- Thanjavur Subha Rao 1830–1837

- T. Ranga Rao (acting) 1837–1838

- T. Venkata Rao (Again) 1838–1839

- Thanjavur Subha Rao (again) 1839–1842

- Krishna Rao (acting) 1842–1843

- Reddy Rao (again) 1843–1845

- Srinivasa Rao (acting) 1845–1846

- Krishna Rao 1846–1858

| Name | Portrait | Took office | Left office | Term[39] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. Madhava Rao |

|

1857 | 1872 | 1 |

| A. Seshayya Sastri |

|

1872 | 1877 | 1 |

| Nanoo Pillai | 1877 | 1880 | 1 | |

| V. Ramiengar |

|

1880 | 1887 | 1 |

| T. Rama Rao |

|

1887 | 1892 | 1 |

| S. Shungrasoobyer | 1892 | 1898 | 1 | |

| V. Nagam Aiya |

|

1901 | 1904 | 1 |

| K. Krishnaswamy Rao |

|

1898 | 1904 | 1 |

| V. P. Madhava Rao |

|

1904 | 1906 | 1 |

| S. Gopalachari | 1906 | 1907 | 1 | |

| P. Rajagopalachari | 1907 | 1914 | 1 | |

| M. Krishnan Nair | 1914 | 1920 | 1 | |

| T. Raghavaiah | 1920 | 1925 | 1 | |

| M. E. Watts | 1925 | 1929 | 1 | |

| V. S. Subramanya Iyer | 1929 | 1932 | 1 | |

| T. Austin | 1932 | 1934 | 1 | |

| Sir Muhammad Habibullah |

|

1934 | 1936 | 1 |

| Sir C. P. Ramaswami Iyer |

|

1936 | 1947 | 1 |

| P.G.N.Unnithan | 1947 | 1947 | 1 |

Administrative divisions

In 1856, the princely state was sub-divided into three divisions, each of which was administered by a Divan Peishkar, with a rank equivalent to a District Collector in British India.[40] These were the:

- Northern (Kottayam) comprising the talukas of Sharetalay, Vycome, Yetmanoor, Cottayam, Chunginacherry, Meenachil, Thodupolay, Moovatupolay, Kunnathnaud, Alangaud and Paravoor;

- Quilon (Central), comprising the talukas of Ambalapuzha, Chengannur, Pandalam, Kunnattur, Karungapalli, Karthikapally Harippad, Mavelikkara, Quilon; and

- Southern (Padmanabhapuram) comprising the talukas of Thovalay, Auguteeswarom, Kalculam, Eraneel, and Velavencode.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1816 | 906,587 | — |

| 1836 | 1,280,668 | +1.74% |

| 1854 | 1,262,647 | −0.08% |

| 1875 | 2,311,379 | +2.92% |

| 1881 | 2,401,158 | +0.64% |

| 1891 | 2,557,736 | +0.63% |

| 1901 | 2,952,157 | +1.44% |

| 1911 | 3,428,975 | +1.51% |

| 1921 | 4,006,062 | +1.57% |

| 1931 | 5,095,973 | +2.44% |

| 1941 | 6,070,018 | +1.76% |

| Source:[41][42][43] | ||

Travancore had a population of 6,070,018 at the time of the 1941 Census of India.[45]

Religions

| Census year | Total population | Hindus | Christians | Muslims | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1816 - 1820 | 906,587[46] | 752,371[46] | 82.99% | 112,158[46] | 12.37% | 42,058[46] | 4.64% |

| 1881 | 2,401,158[47] | 1,755,610[47] | 73.12% | 498,542[47] | 20.76% | 146,909[47] | 6.12% |

| 1891 | 2,557,736[48] | 1,871,864[48] | 73.18% | 526,911[48] | 20.60% | 158,823[48] | 6.21% |

| 1901 | 2,952,157[46] | 2,063,798[46] | 69.91% | 697,387[46] | 23.62% | 190,566[46] | 6.46% |

| 1911 | 3,428,975[46] | 2,298,390[46] | 67.03% | 903,868[46] | 26.36% | 226,617[46] | 6.61% |

| 1921 | 4,006,062[46] | 2,562,301[46] | 63.96% | 1,172,934[46] | 29.27% | 270,478[46] | 6.75% |

| 1931 | 5,095,973[46] | 3,137,795[46] | 61.57% | 1,604,475[46] | 31.46% | 353,274[46] | 6.93% |

| 1941 | 6,070,018[44] | 3,671,480[44] | 60.49% | 1,963,808[44] | 32.35% | 434,150[44] | 7.15% |

Languages

| Census year | Total population | Malayalam | Tamil | Others | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1875 | 2,311,379[47] | 1,902,533[47] | 82.32% | 387,909[47] | 16.78% | 20,937[47] | 0.91% |

| 1881 | 2,401,158[47] | 1,937,454[47] | 80.69% | 439,565[47] | 18.31% | 24,139[47] | 1.01% |

| 1891 | 2,557,736[48] | 2,079,271[48] | 81.29% | 448,322[48] | 17.53% | 30,143[48] | 1.18% |

| 1901 | 2,952,157[49] | 2,420,049[49] | 81.98% | 492,273[49] | 16.68% | 39,835[49] | 1.35% |

| 1911 | 3,428,975[50] | 2,836,728[50] | 82.73% | 554,618[50] | 16.17% | 37,629[50] | 1.10% |

| 1921 | 4,006,062[51] | 3,349,776[51] | 83.62% | 624,917[51] | 15.60% | 31,369[51] | 0.78% |

| 1931 | 5,095,973[46] | 4,260,860[46] | 83.61% | 788,455[46] | 15.47% | 46,658[46] | 0.92% |

Culture

Travancore was characterised by the popularity of its rulers among their subjects.[52] The kings of Travancore, unlike their counterparts in the other princely states of India, spent only a small portion of their state's resources for personal use. This was in sharp contrast with some of the northern Indian kings. Since they spent most of the state's revenue for the benefit of the public, they were naturally much loved by their subjects.[53]

Just like many British Indian states, violence rooted in religion or caste was common in Travancore. Tamil Brahmins and Nairs alone dominated the bureaucracy until 20th century. Many political ideologies (such as communism) and social reforms were not welcomed in Travancore, and in Punnapra, communist protesters were fired at. Travancore royal family were devout Hindus. Some kings practiced untouchablity with British officers, European aristocrats and diplomats (for instance, Richard Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville, 3rd Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, has reported that Maharaja Visakham Thirunal had to take bath after touching Richard's Mrs., to remove ritual pollution, when they visited in 1880).

Unlike most of India, just like in Dakshina Kannada, in Travancore (and the rest of Kerala), the social status and freedom of women were relatively high. In some communities, the daughters inherited the property (though property was exclusively administered by men, their brothers) (until 1925), were educated, and had the right to divorce and remarry, but due to laws passed starting from 1925, by regent queen Sethu Lakshmi Bayi proper patriarchy was established and now women have relatively little rights. [54]

See also

- Madras Presidency

- Kingdom of Cochin

- Malabar District

- Travancore-Cochin

- Thachudaya Kaimal Family

- Travancore–Dutch War

- Travancore War

- Travancore rupee

- Nedumkotta

- Cochin - Travancore Alliance (1761)

- Cochin Travancore War (1755–1756)

- Kingdom of Mysore

- Upper cloth revolt

- Vaikom Satyagraha

- Temple Entry Proclamation

- Marthandavarma (novel)

- The Years of Rice and Salt, an acclaimed novel that features an alternate history Travancore

References

Citations

- ^ British Archives http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/rd/d3e53001-d49e-4d4d-bcb2-9f8daaffe2e0

- ^ Sanjeev Sanyal (10 August 2016). The Ocean of Churn: How the Indian Ocean Shaped Human History. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 183–. ISBN 978-93-86057-61-7.

- ^ a b c "Travancore." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2011. Web. 11 November 2011.

- ^ Chandra Mallampalli, Christians and Public Life in Colonial South India, 1863–1937: Contending with Marginality, RoutledgeCurzon, 2004, p. 30

- ^ https://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/gazetteer/pager.html?objectid=DS405.1.I34_V24_023.gif

- ^ P. Shungunny Menon (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times. Thiruvananthapuram: Higginbotham's.

- ^ R. Narayana Panikkar (18 April 1933). Travancore History (in Malayalam). Nagar Kovil.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Database: HANDBOOK FOR INDIA PART 1. - MADRAS., Page vii". 1 August 2008. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "തിരുവിതാംകൂര്" (in Malayalam). The State Institute of Encyclopaedic Publications. 4 July 2008. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ^ Ramusack, Barbara N. (2004). The Indian Princes and their States. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-13944-908-3.

- ^ A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ a b A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. p. 139. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. p. 140. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. p. 141. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ C. J. Fuller (30 December 1976). The Nayars Today. CUP Archive. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-521-29091-3. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ a b c Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times (pdf). Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. pp. 136–140. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ a b Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times (pdf). Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. pp. 162–164. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ "9 Madras : A Tale of 'Terrors'". Sainik Samachar. The journal of India's Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2007.

- ^ Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times (pdf). Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. p. 171. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ A Social History of India – (Ashish Publishing House: ISBN 81-7648-170-X / ISBN 81-7648-170-X, Jan 2000).

- ^ Sadasivan, S.N., 1988, Administration and social development in Kerala: A study in administrative sociology, New Delhi, Indian Institute of Public Administration

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) MATHRUBHUMI Paramparyam ഹിരണ്യഗര്ഭച്ചടങ്ങിന് ഡച്ചുകാരോട് ചോദിച്ചത് 10,000 കഴിഞ്ച് സ്വര്ണം - "ശ്രീമൂലംതിരുനാള് വരെയുള്ള രാജാക്കന്മാര് ഹിരണ്യഗര്ഭം നടത്തിയിട്ടുണ്ടെന്നാണ് അറിയുന്നത്. ഭാരിച്ച ചെലവ് കണക്കിലെടുത്ത് ശ്രീചിത്തിരതിരുനാള് ബാലരാമവര്മ്മ മഹാരാജാവ് ഈ ചടങ്ങ് നടത്തിയില്ല." - ^ Cf. Ward & Conner, Geographical and Statistical Memoir, page 133; V. Nagam Aiya, The Travancore State Manual, Volume-2, Madras:AES, 1989 (1906), page 72.

- ^ G. Patrick, Religion and Subaltern Agency, University of Madras, 2003, The Subaltern Agency in Ayyavali, Page 174.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)Towards Modern Kerala, 10th Standard Text Book, Chapter 9, Page 101. See this Pdf - ^ C.f. Rev.Samuel Zechariah, The London Missionary Society in South Travancore, Page 201.

- ^ A. Sreedhara, Menon. A Survey Of Kerala History. pp. 271–273.

- ^ "Travancore State Forces". 13 April 2020. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "During his rule, the revenues of the State were nearly quadrupled from a little over Rs 21/2 crore to over Rs 91/2 crore." - 'THE STORY OF THE INTEGRATION OF THE INDIAN STATES' by V. P. MENON

- ^ Supreme Court, Of India. "GOOD GOVERNANCE: JUDICIARY AND THE RULE OF LAW" (PDF). Sree Chithira Thirunal Memorial Lecture, 29 December 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ Gauri Lakshmi Bai, Aswathy Thirunal (1998). Sree Padmanabhaswamy Kshetram. Thiruvananthapuram: The State Institute Of Languages, Kerala. pp. 242–243. ISBN 978-81-7638-028-7.

- ^ Menon, A. Sreedhara (1967). A Survey Of Kerala History. Kottayam: D C Books. p. 273. ISBN 81-264-1578-9.

- ^ Sreedhara Menon in Triumph & Tragedy in Travancore Annals of Sir C. P.'s Sixteen Years, DC Books publication

- ^ Aiyappan Pillai Interview to Asianet news Accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iIMS_6Z_WRE

- ^ Gauri Lakshmi Bai, Aswathy Thirunal (July 1998). Sree Padmanabha Swamy Kshetram. Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala: The State Institute Of Languages. pp. 278–282, 242–243, 250–251. ISBN 978-81-7638-028-7.

- ^ THE CONSTITUTION (TWENTY-SIXTH AMENDMENT) ACT, 1971 Archived 6 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Aiya 1906, p. 329-30.

- ^ de Vries, Hubert (26 October 2009). "Travancore". Hubert Herald. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012.

- ^ The ordinal number of the term being served by the person specified in the row in the corresponding period

- ^ Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times (pdf). Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. p. 486. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Travancore, Part I, Vol-XXV (1941) (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore. 1942. p. 13.

- ^ Report on the Census of Travancore (1891) (PDF). Chennai: Government of India. 1894. p. 631.

- ^ Report on the Census of Travancore (1881) (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of India. 1884. p. 87.

- ^ a b c d e Travancore, Part I, Vol-XXV (1941) (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore. 1942. pp. 124–125.

- ^ "Table 1 - Area, houses and population". 1941 Census of India. Government of India. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Census of India, 1931, VOLUME XXVIII, Travancore, Part-I Report (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore. 1932. pp. 327, 331.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Report on the Census of Travancore (1881) (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of India. 1884. pp. 135, 258.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Report on the Census of Travancore (1891) (PDF). Chennai: Government of India. 1894. pp. 10–11, 683.

- ^ a b c d Iyer, N. Subrahmanya (1903). Census of India-1901, Volume-XXVI, Travancore (Part-I). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore. pp. 224–225.

- ^ a b c d Iyer, N. Subramhanya (1912). Census of India - 1911, Volume-XXIII, Travancore (Part-I) (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore. p. 176.

- ^ a b c d Iyer, S. Krishnamoorthi (1922). Census of India, 1921, Volume-XXV, Travancore. Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore. p. 91.

- ^ THE HINDU by STAFF REPORTER, May 14, 2013, ‘Simplicity hallmark of Travancore royal family’- National seminar on the last phase of monarchy in Travancore inaugurated: "History is replete with instances where the Travancore royal family functioned more as servants of the State than rulers who exploited the masses. The simplicity that the family consistently upheld in all aspects of governance distinguished it from other contemporary monarchies, said Governor of West Bengal M.K. Narayanan"

- ^ "Sree Chithira Thirunal, was a noble model of humility, simplicity, piety and total dedication to the welfare of the people. In the late 19th and early 20th century when many native rulers were callously squandering the resources Of their, states, this young Maharaja was able to shine like a solitary star in the firmament, with his royal dignity, transparent sincerity, commendable intelligence and a strong sense of duty."- 'A Magna Carta of Religious Freedom' Speech By His Excellency V.Rachaiya, Governor of Kerala, delivered at Kanakakkunnu Palace on 25.10.1992

- ^ Santhanam, Kausalya (30 March 2003). "Royal vignettes: Travancore - Simplicity graces this House". The Hindu (magazine section). Retrieved 14 February 2014.

Bibliography

- Aiya, V. Nagam (1906). Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government Press. (Digital book format)

Further reading

- Hatch, Emily Gilchriest (1934). Pictures of Travancore. Oxford University Press. p. 64.

- Hatch, Emily Gilchriest (1933). Travancore: A guide book for the visitor with thirty-two illustrations and two maps. Calcutta: Oxford University Press. p. 270. (a second revision was published in 1939)

- Menon, P. Shungoonny (1879). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times. Higginbotham & Co., Madras.