Harran: Difference between revisions

Show where it's called "Harran": http://scripturetext.com/genesis/11-31.htm. / As for the scholarly ID, someone challenged it. Me? I'll accept "often", the longstanding word. *You* prove it's always. |

rv - please do not waste valuable time with this facetiousness / ignorance of facts. NOBODY identifies Abraham's Haran as anywhere else; don't forget to check Acts 7:2, also the LXX spelling |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

'''Harran''' ({{lang-akk|''Harrânu''}}; {{unicode|{{lang-grc|Κάῤῥαι}}}}; {{lang-la|Carrhae}}) is a district of [[Şanlıurfa Province]] in the southeast of [[Turkey]]. |

'''Harran''' ({{lang-akk|''Harrânu''}}; {{unicode|{{lang-grc|Κάῤῥαι}}}}; {{lang-la|Carrhae}}) is a district of [[Şanlıurfa Province]] in the southeast of [[Turkey]]. |

||

A very ancient city which was a major [[Assyria]]n commercial, cultural, and religious center, Harran is a valuable archaeological site. It is |

A very ancient city which was a major [[Assyria]]n commercial, cultural, and religious center, Harran is a valuable archaeological site. It is identified with [[Haran]], the place in which [[Abraham]] lived before he reached [[Canaan]], and with the Haran of [[Book of Ezekiel|Ezekiel]] 27:23, a city which traded with [[Tyre (Lebanon)|Tyre]]. One of Harran's specialties was the odoriferous gum derived from the ''[[stobrum]]'' tree.<ref>([[Pliny the Elder|Pliny]], N.H. xii. 40)</ref><ref>''Thuya'' spp., also perhaps ''Juniperus''. See commentary in '''The Natural History of Pliny''' vol. III annotated by Bostock and Riley, Bell & Sons London 1892</ref> The city was the chief home of the Mesopotamian [[Lunar deity|moon god]] [[Sin (mythology)|Sin]], under the Assyrians and [[Neo-Babylonian Empire|Neo-Babylonians/Chaldeans]] and even into [[Roman Empire|Roman]] times. |

||

Carrhae is a defunct ancient town on the site, and gave its name to the [[Battle of Carrhae]] (53 BC), fought between the [[Roman Republic]] and the [[Parthian Empire]]. Harran's ruins date from Assyrian, [[Roman Empire|Roman]], [[Mandeans|Mandean]]/[[Sabian]], and [[Caliphate|Arab Islamic Caliphate]] times. [[T. E. Lawrence]] surveyed the site. |

Carrhae is a defunct ancient town on the site, and gave its name to the [[Battle of Carrhae]] (53 BC), fought between the [[Roman Republic]] and the [[Parthian Empire]]. Harran's ruins date from Assyrian, [[Roman Empire|Roman]], [[Mandeans|Mandean]]/[[Sabian]], and [[Caliphate|Arab Islamic Caliphate]] times. [[T. E. Lawrence]] surveyed the site. |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

===Harran in scriptures=== |

===Harran in scriptures=== |

||

The [[Hebrew Bible]]'s [[Book of Genesis]] (Genesis 11:31, 12:4-5) identifies |

The [[Hebrew Bible]]'s [[Book of Genesis]] (Genesis 11:31, 12:4-5) identifies Harran (also written ''Haran'', ''Charan'', and ''Charran''; {{lang-he|חָרָן}}), where [[Terah]] and his son Abram ([[Abraham]]), grandson [[Lot (Bible)|Lot]], and Abram's wife [[Sarah|Sarai]] halted on their way from [[Ur Kaśdim|Ur of the Chaldees]] to Canaan (Genesis 11:26–32). The region of this Haran is referred to variously as ''[[Paddan Aram]]'' and ''[[Aram Naharaim]]''. [[Book of Genesis|Genesis]] 27:43 makes Haran the home of [[Laban (Bible)|Laban]] and connects it with [[Isaac]] and [[Jacob]]: it was the home of Isaac's wife Rebekah, and their son Jacob spent twenty years in Haran working for his uncle Laban (cf. Genesis 31:38&41). The place-name should not be confused with the name of [[Haran]] (Hebrew: הָרָן), Abraham's brother and Lot's father — note that the two names are spelled differently in the original Hebrew. Islamic tradition does link Harran to ''Aran'', the brother of Abraham. |

||

Prior to [[Sennacherib]]'s reign (704–681 BCE), Harran rebelled from the Assyrians, who reconquered the city (see [[Books of Kings|2 Kings]] 19:12 and [[Book of Isaiah|Isaiah]] 37:12) and deprived it of many privileges – which King [[Sargon II]] later restored. |

Prior to [[Sennacherib]]'s reign (704–681 BCE), Harran rebelled from the Assyrians, who reconquered the city (see [[Books of Kings|2 Kings]] 19:12 and [[Book of Isaiah|Isaiah]] 37:12) and deprived it of many privileges – which King [[Sargon II]] later restored. |

||

Revision as of 11:22, 2 September 2010

Harran ([Harrânu] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help); Ancient Greek: Κάῤῥαι; Latin: Carrhae) is a district of Şanlıurfa Province in the southeast of Turkey.

A very ancient city which was a major Assyrian commercial, cultural, and religious center, Harran is a valuable archaeological site. It is identified with Haran, the place in which Abraham lived before he reached Canaan, and with the Haran of Ezekiel 27:23, a city which traded with Tyre. One of Harran's specialties was the odoriferous gum derived from the stobrum tree.[1][2] The city was the chief home of the Mesopotamian moon god Sin, under the Assyrians and Neo-Babylonians/Chaldeans and even into Roman times.

Carrhae is a defunct ancient town on the site, and gave its name to the Battle of Carrhae (53 BC), fought between the Roman Republic and the Parthian Empire. Harran's ruins date from Assyrian, Roman, Mandean/Sabian, and Arab Islamic Caliphate times. T. E. Lawrence surveyed the site. In 1950 Seton Lloyd conducted a 3 week archaeological survey at Harran. [3] An Anglo–Turkish excavation was begun in 1951, ending in 1956 with the death of D. S. Rice. [4]

Ancient Harran

The district is near the border with Syria, 24 miles (44 kilometers) southeast of the city of Şanlıurfa, the former Edessa, at the end of a long straight road across the hot plain of Harran.

The earliest records of Harran come from the Ebla tablets (c. 2300 BC). From these, it is known that an early king or mayor of Harran had married an Eblaite princess, Zugalum, who then became "queen of Harran", and whose name appears in a number of documents. It appears that Harran remained a part of the regional Eblaite kingdom for some time thereafter.

After the Suppiluliuma I–Shattiwaza treaty (14th century BC) between the Hittite Empire and Mitanni, Harran was burned by a Hittite army under Piyashshili in the course of the conquest of Mitanni.

In its prime Harran was a major Assyrian city which controlled the point where the road from Damascus joins the highway between Nineveh and Carchemish. This location gave Harran strategic value from an early date. It is frequently mentioned in Assyrian inscriptions as early as the time of Tiglath-Pileser I, about 1100 BC, under the name Harranu (Akkadian harrānu, "road, path; campaign, journey").

Sacked in 763 BCE, Harran was restored under the Assyrian ruler Sargon II. It served for four years as the headquarters for the then-crumbling Neo-Assyrian Empire after the fall of its capital Nineveh in 612 BCE, before being sacked in 608 BCE.

Sin's temple was rebuilt by several kings, among them the Assyrian Assur-bani-pal (7th century BCE) and the Neo-Babylonian Nabonidus (6th century BCE). [5] [6] Herodian (iv. 13, 7) mentions the town as possessing in his day a temple of the moon.

Harran in scriptures

The Hebrew Bible's Book of Genesis (Genesis 11:31, 12:4-5) identifies Harran (also written Haran, Charan, and Charran; Hebrew: חָרָן), where Terah and his son Abram (Abraham), grandson Lot, and Abram's wife Sarai halted on their way from Ur of the Chaldees to Canaan (Genesis 11:26–32). The region of this Haran is referred to variously as Paddan Aram and Aram Naharaim. Genesis 27:43 makes Haran the home of Laban and connects it with Isaac and Jacob: it was the home of Isaac's wife Rebekah, and their son Jacob spent twenty years in Haran working for his uncle Laban (cf. Genesis 31:38&41). The place-name should not be confused with the name of Haran (Hebrew: הָרָן), Abraham's brother and Lot's father — note that the two names are spelled differently in the original Hebrew. Islamic tradition does link Harran to Aran, the brother of Abraham.

Prior to Sennacherib's reign (704–681 BCE), Harran rebelled from the Assyrians, who reconquered the city (see 2 Kings 19:12 and Isaiah 37:12) and deprived it of many privileges – which King Sargon II later restored.

According to an early Arabic work known as Kitab al-Magall or the Book of Rolls (part of Clementine literature), Harran was one of the cities built by Nimrod, when Peleg was 50 years old. The Syriac Cave of Treasures (ca. 350) contains a similar account of Nimrod's building Harran and the other cities, but places the event when Reu was 50 years old.

Medes, Persians, Greeks, and Romans

During the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Harran became the stronghold of its last king, Ashur-uballit II, who used Harran as a base for a failed attempt to retake Nineveh. Harran was besieged and conquered by Nabopolassar of Babylon and his Median and Scythian allies in 608 BC. Harran became part of the Babylonian Empire after the fall of Assyria, and subsequently passed to the Persian Achaemenid dynasty in the 6th century BCE. It became part of the Persian province of Athura, the Persian word for Assyria. The city remained in Persian hands until 331 BC, when the soldiers of the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great entered the city.

After the death of Alexander on June 11, 323 BC, the city was contested by his successors: Perdiccas, Antigonus Monophthalmus, and Eumenes visited the city, but eventually it became part of the realm of Seleucus I Nicator, of the Seleucid Empire, and capital of a province called Osrhoene (the Greek rendering of the old name Urhai). For one and a half centuries the town flourished, and became independent when the Parthian dynasty of Persia occupied Babylonia. The Parthian and Seleucid kings were both happy with a buffer state, and the dynasty of the Arabian Abgarides, technically a vassal of the Parthian "king of kings", was to rule Osrhoene for centuries. The main language spoken in Oshroene was Aramaic, and the majority of people were Christian Assyrians.

In Roman times, Harran was known as Carrhae, and was the location of the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, in which the Parthians, commanded by general Surena, defeated a large Roman army under the command of Crassus, who was killed.

Centuries later, the emperor Caracalla was murdered here at the instigation of Macrinus (217). The emperor Galerius was defeated nearby by the Parthians' successors, the Sassanid dynasty of Persia, in 296 AD. The city remained under Persian control until the fall of the Sassanids to the Arabs in 651 AD.

Christianity and Sabianism/Mandaeism

Harran was a centre of Assyrian Christianity from early on, and was the first place where purpose-built churches were constructed openly. However, although a bishop resided in the city, many people of Harran retained their ancient pagan faith during the Christian period, and ancient Mesopotamian/Assyrian gods such as Sin and Ashur were still worshipped for a time. In addition the Mandean religion, a form of Gnosticism, was born in Harran.

Islamic Harran

At the beginning of the Islamic period Harran was located in the land of the Mudar tribe (Diyar Mudar), the western part of northern Mesopotamia (Jazira). Along with ar-Ruha' (Şanlıurfa) and Ar-Raqqah it was one of the main cities in the region. During the reign of the Umayyad caliph Marwan II Harran became the seat of the caliphal government of the Islamic empire stretching from Spain to Central Asia.

It was allegedly the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun who, while passing through Harran on his way to a campaign against the Byzantine Empire, forced the Harranians to convert to one of the 'religions of the book', meaning Judaism, Christianity, or Islam. The pagan people of Harran identified themselves with the Sabians in order to fall under the protection of Islam. Aramaean and Assyrian Christians remained Christian. Sabians were mentioned in the Qur'an, but those were a group of Gnostic Mandaeans living in southern Mesopotamia. The relationship of the Harranian Sabians to the ones mentioned in the Qur'an is a matter of dispute.

Islam's first university

During the late 8th and 9th centuries Harran was a centre for translating works of astronomy, philosophy, natural sciences, and medicine from Greek to Syriac by Assyrians, and thence to Arabic, bringing the knowledge of the classical world to the emerging Arabic-speaking civilization in the south. Baghdad came to this work later than Harran. Many important scholars of natural science, astronomy, and medicine originate from Harran; they were non-Arab and non-Islamic ethnic Assyrians, including possibly the alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān.[7]

The end of the Mandaeans

In 1032 or 1033 the temple of the Sabians was destroyed and the urban community extinguished by an uprising of the rural, starving 'Alid-Shiite population and impoverished urban Muslim militias. In 1059-60 the temple was rebuilt into a fortified residence of the Numayrids, an Arab tribe assuming power in the Diyar Mudar (western Jazira) during the 11th century. The Zangid ruler Nur al-Din Mahmud transformed the residence into a strong fortress.

The Crusades

During the Crusades, on May 7, 1104 a decisive battle was fought in the Balikh river valley, commonly known as the Battle of Harran. However, according to Matthew of Edessa the actual location of the battle lies two days away from Harran. Albert of Aachen and Fulcher of Chartres locate the battleground in the plain opposite to the city of ar-Raqqah. During the battle, Baldwin of Bourcq, Count of Edessa, was captured by troops of the Great Seljuq Empire. After his release Baldwin became King of Jerusalem.

At the end of 12th century Harran served together with ar-Raqqah as a residence of Kurdish Ayyubid princes. The Ayyubid ruler of the Jazira, Al-Adil I, again strengthened the fortifications of the castle. In the 1260s the city was completely destroyed and abandoned during the Mongol invasions of Syria. The father of the famous Hanbalite scholar Ibn Taymiyyah was a refugee from Harran, settling in Damascus. The 13th century Arab historian Abu al-Fida describes the city as being in ruins.

Modern Harran

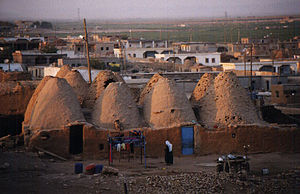

Harran is famous for its traditional 'beehive' adobe houses, constructed entirely without wood. The design of these makes them cool inside (essential in this part of the world) and is thought to have been unchanged for at least 3,000 years. Some were still in use as dwellings until the 1980s. However, those remaining today are strictly tourist exhibits, while most of Harran's population lives in a newly built small village about 2 kilometres away from the main site.

At the historical site the ruins of the city walls and fortifications are still in place, with one city gate standing, along with some other structures. Excavations of a nearby 4th century BC burial mound continue under archaeologist Dr Nurettin Yardımcı.

The new village is poor and life is hard in the hot weather on this plain. The people here are now ethnic Arabs and live by long-established traditions. It is believed that these Arabs were settled here during the 18th century by the Ottoman Empire. The women of the village are tattooed and dressed in traditional Bedouin clothes. The Assyrians who once occupied the area for thousands of years have moved to other areas, although there are some Assyrian villages in the general area.

By the late 1980s the large plain of Harran had fallen into disuse as the streams of Cüllab and Deysan, its original water-supply had dried up. But the plain is irrigated by the recent Southeastern Anatolia Project and is becoming green again. Cotton and rice can now be grown.

Politics

Sanliurfa is represented by 11 congressmen in Turkey's Parliament. Following the elections in 2007, the names of the legislators are: Abdulkadir Emin Önen, Abdurrahman Müfit Yetkin, Çağla Aktemur Özyavuz, Eyyüp Cenap Gülpınar, Mustafa Kuş, Ramazan Başak, Sabahattin Cevheri, Yahya Akman, Zülfükar İzol, İbrahim Binici, and Seyit Eyyüpoğlu.

Notables

- Ibn Taymiyyah, Islamic scholar

- Nabonidus, the last Neo-Babylonian king

- Belshazzar, Nabonidus's son and regent

See also

Notes

- ^ (Pliny, N.H. xii. 40)

- ^ Thuya spp., also perhaps Juniperus. See commentary in The Natural History of Pliny vol. III annotated by Bostock and Riley, Bell & Sons London 1892

- ^ Seton Lloyd and William Brice, Harran, Anatolian Studies, vol. 1, pp. 77-111, 1951

- ^ David Storm Rice, Medieval Harran. Studies on Its Topography and Monuments I, Anatolian Studies, vol. 2, pp. 36–84, 1952

- ^ H. W. F. Saggs, Neo-Babylonian Fragments from Harran, Iraq, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 166-169, 1969

- ^ C. J. Gadd, The Harran Inscriptions of Nabonidus, Anatolian Studies, vol. 8, pp. 35-92, 1958

- ^ "Geber - LoveToKnow 1911".

References

- Chwolsohn, Daniil Abramovic, Die Ssabier und der Ssabismus, 2 vols. St. Petersburg, 1856. [Still a valuable reference and collection of sources]

- Green, Tamara, The City of the Moon God: Religious Traditions of Harran. Leiden, 1992.

- Heidemann, Stefan, Die Renaissance der Städte in Nordsyrien und Nordmesopotamien: Städtische Entwicklung und wirtschaftliche Bedingungen in ar-Raqqa und Harran von der beduinischen Vorherrschaft bis zu den Seldschuken (Islamic History and Civilization. Studies and Texts 40). Leiden, 2002 .