Bosnia and Herzegovina: Difference between revisions

FkpCascais (talk | contribs) Reverted some very contrversial claims |

Undid revision 649249982 by FkpCascais (talk) Sorry but given your self-declared Serb ethnicity, I can't agree to any edit you make - see Talk:Boris_Kalamanos, and stick to soccer. |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

|native_name = Bosna i Hercegovina<br/>Босна и Херцеговина |

|native_name = Bosna i Hercegovina<br/>Босна и Херцеговина |

||

|common_name = Bosnia and Herzegovina |

|common_name = Bosnia and Herzegovina |

||

|status = |

|status = [[Cultural hegemony]] |

||

|image_flag = Flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina.svg |

|image_flag = Flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina.svg |

||

|image_coat = Coat of arms of Bosnia and Herzegovina.svg |

|image_coat = Coat of arms of Bosnia and Herzegovina.svg |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

|upper_house = [[House of Peoples (Bosnia and Herzegovina)|House of Peoples]] |

|upper_house = [[House of Peoples (Bosnia and Herzegovina)|House of Peoples]] |

||

|lower_house = [[House of Representatives (Bosnia and Herzegovina)|House of Representatives]] |

|lower_house = [[House of Representatives (Bosnia and Herzegovina)|House of Representatives]] |

||

|sovereignty_type = |

|sovereignty_type = [[Usurped]] [[monarchy]] |

||

|sovereignty_note = Sovereignty notes: following occupation by Turkey in 1527, sovereignty usurpation transferred amongst foreign powers in deals made on foreign soil |

|||

|sovereignty_note = |

|||

|established_event1 = [[King]] [[Géza II of Hungary]] to Hungarian prince [[Boris Kalamanos]] who ruled as [[Ban Borić]] of [[Banate of Bosnia|Bosnia]] |

|||

|established_event1 = |

|||

|established_date1 = 1141 |

|established_date1 = 1141 |

||

|established_event2 = as kingdom under King [[Tvrtko I of Bosnia]], [[House of Kotromanić]] |

|established_event2 = as kingdom under King [[Tvrtko I of Bosnia]], [[House of Kotromanić]] |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

|established_event3 = as principality under [[Berislavići Grabarski|House of Berislavić]] |

|established_event3 = as principality under [[Berislavići Grabarski|House of Berislavić]] |

||

|established_date3 = 1463 |

|established_date3 = 1463 |

||

|established_event4 = [[Ottoman conquest of Bosnia and Herzegovina|conquest]] by [[House of Ottoman]] |

|established_event4 = [[Ottoman conquest of Bosnia and Herzegovina|conquest]] with [[regicide]] by [[House of Ottoman]] |

||

|established_date4 = 1527 |

|established_date4 = 1527 |

||

|established_event5 = transfer at [[Treaty of Berlin (1878)|Treaty of Berlin]] to [[House of Hapsburg]] |

|established_event5 = usurpation transfer at [[Treaty of Berlin (1878)|Treaty of Berlin]] to [[House of Hapsburg]] |

||

|established_date5 = 1878 |

|established_date5 = 1878 |

||

|established_event6 = transfer at [[Paris Peace Conference, 1919|Paris Peace Conference]] to [[House of Windsor]] for [[House of Karađorđević]] |

|established_event6 = usurpation transfer at [[Paris Peace Conference, 1919|Paris Peace Conference]] to [[House of Windsor]] for [[House of Karađorđević]] |

||

|established_date6 = 1919 |

|established_date6 = 1919 |

||

|established_event7 = transfer by force to [[House of Savoy]] |

|established_event7 = usurpation transfer by force to [[House of Savoy]] |

||

|established_date7 = 1941 |

|established_date7 = 1941 |

||

|established_event8 = transfer at [[Tehran Conference]] to [[House of Windsor]] |

|established_event8 = usurpation transfer at [[Tehran Conference]] to [[House of Windsor]] |

||

|established_date8 = 1943 |

|established_date8 = 1943 |

||

|established_event9 = |

|established_event9 = usurpation transfer at [[Dayton-Paris Agreement|Dayton-Paris Peace Conferences]] to [[Holy See]] |

||

|established_date9 = |

|established_date9 = 1995 |

||

|established_event10 = transfer at [[Dayton-Paris Agreement|Dayton-Paris Peace Conferences]] |

|||

|established_date10 = 1995 |

|||

|area_rank = 127th |

|area_rank = 127th |

||

|area_km2 = 51,197 |

|area_km2 = 51,197 |

||

| Line 111: | Line 109: | ||

|footnote_e = Current presidency member ([[Bosniak]]). |

|footnote_e = Current presidency member ([[Bosniak]]). |

||

}} |

}} |

||

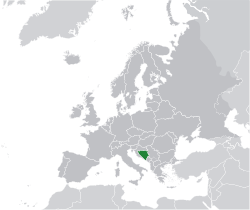

'''Bosnia and Herzegovina''' ({{IPAc-en|audio=En-us-Bosnia and Herzegovina.ogg|'|b|ɒ|z|n|i|ə|_|æ|n|d|_|h|ɛər|t|s|ə|g|ɵ|'|v|iː|n|ə}}; [[Bosnian language|Bosnian]], [[Croatian language|Croatian]] and [[Serbian language|Serbian]] ''Bosna i Hercegovina'', {{IPA-sh|bôsna i xěrt͡seɡoʋina|pron}}; [[Serbian Cyrillic|Cyrillic script]]: Боснa и Херцеговина), sometimes called '''Bosnia-Herzegovina''', abbreviated '''BiH''', and in short often known informally as '''Bosnia''', is a country in [[Southeastern Europe]] located on the [[Balkan Peninsula]]. [[Sarajevo]] is the capital and largest city.<ref name='CIA'/> Bordered by [[Croatia]] to the north, west and south, [[Serbia]] to the east, and [[Montenegro]] to the southeast, Bosnia and Herzegovina is almost [[landlocked]], except for {{convert|20|km|abbr=off}} of coastline on the [[Adriatic Sea]] surrounding the city of [[Neum]].<ref name="coastline">[https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2060.html Field Listing – Coastline], ''[[The World Factbook]]'', 2006-08-22</ref><ref>[http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761563626/Bosnia_and_Herzegovina.html Bosnia and Herzegovina: I: Introduction]{{dead link|date=January 2011}}, ''[[Encarta]]'', 2006. [http://www.webcitation.org/5kwQDsIKK Archived] 2009-10-31.</ref> In the central and eastern interior of the country the geography is mountainous, in the northwest it is moderately hilly, and the northeast is predominantly flatland. The inland is a geographically larger region and has a moderate [[continental climate]], bookended by hot summers and cold and snowy winters. The southern tip of the country has a [[Mediterranean climate]] and plain topography. |

'''Bosnia and Herzegovina''' ({{IPAc-en|audio=En-us-Bosnia and Herzegovina.ogg|'|b|ɒ|z|n|i|ə|_|æ|n|d|_|h|ɛər|t|s|ə|g|ɵ|'|v|iː|n|ə}}; [[Bosnian language|Bosnian]], [[Croatian language|Croatian]] and [[Serbian language|Serbian]] ''Bosna i Hercegovina'', {{IPA-sh|bôsna i xěrt͡seɡoʋina|pron}}; [[Serbian Cyrillic|Cyrillic script]]: ''Боснa и Херцеговина''), sometimes called '''Bosnia-Herzegovina''', abbreviated '''BiH''', and in short often known informally as '''Bosnia''', is a country in [[Southeastern Europe]] located on the [[Balkan Peninsula]]. [[Sarajevo]] is the capital and largest city.<ref name='CIA'/> Bordered by [[Croatia]] to the north, west and south, [[Serbia]] to the east, and [[Montenegro]] to the southeast, Bosnia and Herzegovina is almost [[landlocked]], except for {{convert|20|km|abbr=off}} of coastline on the [[Adriatic Sea]] surrounding the city of [[Neum]].<ref name="coastline">[https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2060.html Field Listing – Coastline], ''[[The World Factbook]]'', 2006-08-22</ref><ref>[http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761563626/Bosnia_and_Herzegovina.html Bosnia and Herzegovina: I: Introduction]{{dead link|date=January 2011}}, ''[[Encarta]]'', 2006. [http://www.webcitation.org/5kwQDsIKK Archived] 2009-10-31.</ref> In the central and eastern interior of the country the geography is mountainous, in the northwest it is moderately hilly, and the northeast is predominantly flatland. The inland is a geographically larger region and has a moderate [[continental climate]], bookended by hot summers and cold and snowy winters. The southern tip of the country has a [[Mediterranean climate]] and plain topography. |

||

Today, the country maintains high [[List of countries by Human Development Index|literacy, life expectancy and education]] levels and is one of the [[Tourism in Bosnia and Herzegovina|most frequently visited countries in the region]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lonelyplanet.com/bosnia-and-hercegovina |title=Lonely Planet's Bosnia and Herzegovina Tourism Profile |publisher=Lonely Planet}}</ref> projected to have the third highest tourism growth rate in the world between 1995 and 2020.<ref name="Newfound">[http://features.us.reuters.com/destinations/news/L20239376.html Bosnia's newfound tourism], [[Reuters]].</ref> Bosnia and Herzegovina is regionally and internationally renowned for its natural beauty and [[Culture of Bosnia and Herzegovina|cultural heritage]] inherited from six historical civilizations, its [[Bosnia and Herzegovina cuisine|cuisine]], [[Tourism in Bosnia and Herzegovina#Winter sports|winter sports]], its eclectic and unique [[Music of Bosnia and Herzegovina|music]], [[Architecture of Bosnia and Herzegovina|architecture]] and its [[Sarajevo#Festivals|festivals]], some of which are the largest and most prominent of their kind in Southeastern Europe.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sff.ba/content.php/en/festival?set_culture=en |title=About the Sarajevo Film Festival |publisher=Sarajevo Film Festival Official Website}}{{dead link|date=January 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.insidefilm.com/europe.html |title=Inside Film's Guide to Film Festivals in |publisher=Inside Film}}</ref> The country is home to three ethnic groups or, officially, [[Ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina|constituent peoples]], a term unique for Bosnia and Herzegovina. [[Bosniaks]] are the largest group of the three, with [[Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina|Serbs]] second and [[Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina|Croats]] third. Regardless of ethnicity, a citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina is often identified in English as a [[Bosnians|Bosnian]]. The terms [[Herzegovina|Herzegovinian]] and [[Bosnia (region)|Bosnia]]n are maintained as a regional rather than ethnic distinction, and the region of Herzegovina has no precisely defined borders of its own. Moreover, the country was simply called "Bosnia" until the Austro-Hungarian occupation at the end of the 19th century.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.utoronto.ca/tsq/03/vinko.shtml |title=The Language Situation in Post-Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina |publisher=Toronto Slavic Quarterly}}</ref> |

Today, the country maintains high [[List of countries by Human Development Index|literacy, life expectancy and education]] levels and is one of the [[Tourism in Bosnia and Herzegovina|most frequently visited countries in the region]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lonelyplanet.com/bosnia-and-hercegovina |title=Lonely Planet's Bosnia and Herzegovina Tourism Profile |publisher=Lonely Planet}}</ref> projected to have the third highest tourism growth rate in the world between 1995 and 2020.<ref name="Newfound">[http://features.us.reuters.com/destinations/news/L20239376.html Bosnia's newfound tourism], [[Reuters]].</ref> Bosnia and Herzegovina is regionally and internationally renowned for its natural beauty and [[Culture of Bosnia and Herzegovina|cultural heritage]] inherited from six historical civilizations, its [[Bosnia and Herzegovina cuisine|cuisine]], [[Tourism in Bosnia and Herzegovina#Winter sports|winter sports]], its eclectic and unique [[Music of Bosnia and Herzegovina|music]], [[Architecture of Bosnia and Herzegovina|architecture]] and its [[Sarajevo#Festivals|festivals]], some of which are the largest and most prominent of their kind in Southeastern Europe.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sff.ba/content.php/en/festival?set_culture=en |title=About the Sarajevo Film Festival |publisher=Sarajevo Film Festival Official Website}}{{dead link|date=January 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.insidefilm.com/europe.html |title=Inside Film's Guide to Film Festivals in |publisher=Inside Film}}</ref> The country is home to three ethnic groups or, officially, [[Ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina|constituent peoples]], a term unique for Bosnia and Herzegovina. [[Bosniaks]] are the largest group of the three, with [[Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina|Serbs]] second and [[Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina|Croats]] third. Regardless of ethnicity, a citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina is often identified in English as a [[Bosnians|Bosnian]]. The terms [[Herzegovina|Herzegovinian]] and [[Bosnia (region)|Bosnia]]n are maintained as a regional rather than ethnic distinction, and the region of Herzegovina has no precisely defined borders of its own. Moreover, the country was simply called "Bosnia" until the Austro-Hungarian occupation at the end of the 19th century.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.utoronto.ca/tsq/03/vinko.shtml |title=The Language Situation in Post-Dayton Bosnia and Herzegovina |publisher=Toronto Slavic Quarterly}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:03, 28 February 2015

Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosna i Hercegovina Босна и Херцеговина | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Državna himna Bosne i Hercegovine National Anthem of Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| |

| Status | Cultural hegemony |

| Capital and largest city | |

| Official languages | Bosnian (official), Croatian (official), Serbian (official)[1]a |

| Ethnic groups (2000 est.[1]) | |

| Religion | [1] |

| Demonym(s) | [1] |

| Government | International protectorate |

| Valentin Inzkob | |

| Dragan Čovićd Bakir Izetbegoviće | |

| Denis Zvizdić | |

| Legislature | Parliamentary Assembly |

| House of Peoples | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Usurped monarchy Sovereignty notes: following occupation by Turkey in 1527, sovereignty usurpation transferred amongst foreign powers in deals made on foreign soil | |

| 1141 | |

• as kingdom under King Tvrtko I of Bosnia, House of Kotromanić | 1377 |

• as principality under House of Berislavić | 1463 |

| 1527 | |

• usurpation transfer at Treaty of Berlin to House of Hapsburg | 1878 |

| 1919 | |

• usurpation transfer by force to House of Savoy | 1941 |

• usurpation transfer at Tehran Conference to House of Windsor | 1943 |

• usurpation transfer at Dayton-Paris Peace Conferences to Holy See | 1995 |

| Area | |

• Total | 51,197 km2 (19,767 sq mi) (127th) |

• Water (%) | 0.8% |

| Population | |

• 2014 census | 3,871,643[1] |

| GDP (PPP) | 2014 estimate |

• Total | $33.251 billion[2] (500) |

• Per capita | $9,225[2] (500) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2014 estimate |

• Total | $19.122 billion[2] (500) |

• Per capita | $3,000[2] |

| Gini (2013) | 36.2[3] medium |

| HDI (2013) | high (68th) |

| Currency | Convertible mark (BAM) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Antipodes | New Zealand seas |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | 387 |

| ISO 3166 code | BA |

| Internet TLD | .ba |

| |

Bosnia and Herzegovina (/ˈbɒzniə ænd hɛərtsəɡ[invalid input: 'ɵ']ˈviːnə/ ; Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian Bosna i Hercegovina, pronounced [bôsna i xěrt͡seɡoʋina]; Cyrillic script: Боснa и Херцеговина), sometimes called Bosnia-Herzegovina, abbreviated BiH, and in short often known informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeastern Europe located on the Balkan Peninsula. Sarajevo is the capital and largest city.[1] Bordered by Croatia to the north, west and south, Serbia to the east, and Montenegro to the southeast, Bosnia and Herzegovina is almost landlocked, except for 20 kilometres (12 miles) of coastline on the Adriatic Sea surrounding the city of Neum.[6][7] In the central and eastern interior of the country the geography is mountainous, in the northwest it is moderately hilly, and the northeast is predominantly flatland. The inland is a geographically larger region and has a moderate continental climate, bookended by hot summers and cold and snowy winters. The southern tip of the country has a Mediterranean climate and plain topography.

Today, the country maintains high literacy, life expectancy and education levels and is one of the most frequently visited countries in the region,[8] projected to have the third highest tourism growth rate in the world between 1995 and 2020.[9] Bosnia and Herzegovina is regionally and internationally renowned for its natural beauty and cultural heritage inherited from six historical civilizations, its cuisine, winter sports, its eclectic and unique music, architecture and its festivals, some of which are the largest and most prominent of their kind in Southeastern Europe.[10][11] The country is home to three ethnic groups or, officially, constituent peoples, a term unique for Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bosniaks are the largest group of the three, with Serbs second and Croats third. Regardless of ethnicity, a citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina is often identified in English as a Bosnian. The terms Herzegovinian and Bosnian are maintained as a regional rather than ethnic distinction, and the region of Herzegovina has no precisely defined borders of its own. Moreover, the country was simply called "Bosnia" until the Austro-Hungarian occupation at the end of the 19th century.[12]

Etymology

The first preserved mention of the name "Bosnia" is in De Administrando Imperio, a politico-geographical handbook written by the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII in the mid-10th century (between 948 and 952) describing the "small country" (χωρίον in Greek) of "Bosona" (Βοσώνα).[13] The Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja from 1172–96 of Bar's Roman Catholic Christian Archbishop names Bosnia, and references an earlier source from the year of 753 – the De Regno Sclavorum (Of the Realm of Slavs). The name "Bosnia" is probably derived from the name of the Bosna river, possibly mentioned for the first time during the 1st century AD by Roman historian Marcus Velleius Paterculus under the name Bathinus flumen.[14] Some scholars[15] also connect the Roman road station Ad Basante, first attested in the 5th century Tabula Peutingeriana, where also the proposed hydronym Bathinus is placed, as referring to Bosnia.[16] According to philologist Anton Mayer the name Bosna could be derived from Illyrian "Bass-an-as" which would be a diversion of the Proto-Indo-European root "bos" or "bogh", meaning "the running water".[17] Other theories involve the rare Latin term Bosina, meaning boundary, and possible Slavic and Thracian origins.[18][19]

The origins of the name Herzegovina may be identified with greater precision. In the Early Middle Ages the corresponding region was known as Zahumlje (Hum), after the Zachlumoi tribe of southern Slavs which inhabited it. In the 1440s, the region – adjoined to medieval Bosnia since the early 1300s – was ruled by the powerful Bosnian nobleman Stephen Vukčić Kosača. In 1448, Kosača dropped the title "Voivode of Bosnia" and instead assumed the title "Herceg (Herzog) of Hum and the Coast";[20] Herzog being the German word for "duke", and so the lands he controlled would later be known as Herzegovina ("Dukedom", from the addition of -ovina, "land").[21] The region was administered by the Ottomans as the Sanjak of Herzegovina (Hersek) within the Eyalet of Bosnia up until the formation of the short-lived Herzegovina Eyalet in the 1830s. Following the death of its founder and ruler vizier Ali-paša Rizvanbegović in the 1850s, the two eyalets were merged, and the new joint-entity was thereafter commonly referred to as Bosnia and Herzegovina.

On initial proclamation of independence in 1992 the country's official name was the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina but following the 1995 Dayton Agreement and the new constitution that accompanied it the name was officially changed to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

History

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a region that traces permanent human settlement back to the Neolithic age, during and after which it was populated by several Illyrian and Celtic civilizations. Culturally, politically, and socially, the country has one of the richest histories in the region, having been first settled by the Slavic peoples that populate the area today from the 6th through to the 9th centuries CE. They then established the first independent banate in the region, known as the Banate of Bosnia,[22] in the early 12th century upon the arrival and convergence of peoples that would eventually come to call themselves Dobri Bošnjani ("Good Bosnians").[23][24] This evolved into the Kingdom of Bosnia in the 14th century, after which it was annexed into the Ottoman Empire, under whose rule it would remain from the mid-15th to the late 19th centuries. The Ottomans brought Islam to the region, and altered much of the cultural and social outlook of the country. This was followed by annexation into the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, which lasted up until World War I. In the interwar period, Bosnia was part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and after World War II, the country was granted full republic status in the newly formed Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Following the dissolution of Yugoslavia, the country proclaimed independence in 1992, which was followed by the Bosnian War, lasting until late 1995.

Early history

Bosnia has been inhabited since at latest the Neolithic age. The earliest Neolithic population became known in the Antiquity as the Illyrians. Celtic migrations in the 4th century BC were also notable. Concrete historical evidence for this period is scarce, but overall it appears that the region was populated by a number of different peoples speaking distinct languages. Conflict between the Illyrians and Romans started in 229 BC, but Rome did not complete its annexation of the region until AD 9.

It was precisely in what is now Bosnia and Herzegovina that Rome fought one of the most difficult battles in its history since the Punic Wars, as described by the Roman historian Suetonius.[25] This was the Roman campaign against the revolt of indigenous communities from Illyricum, known in history as the Great Illyrian Revolt, and also as the Pannonian revolt, or Bellum Batonianum, the latter named after two leaders of the rebellious Illyrian communities, Bato of the Daesitiates, and Bato of the Breuci.[26]

The Great Illyrian revolt was a rising up of Illyrians against the Romans, more specifically a revolt against Tiberius' attempt to recruit them for his war against the Germans. The Illyrians put up a fierce resistance to the most powerful army on earth at the time (the Roman Army) for four years (AD 6 to AD 9), but they were finally subdued by Rome in AD 9.

The last Illyrian stronghold, of which their defence won the admiration of Roman historians, is said to have been Arduba.[27] Bato was captured and taken to Italy. It is alleged that when Tiberius asked Bato and the Daesitiates why they had rebelled, Baton was reputed to have answered: "You Romans are to blame for this; for you send as guardians of your flocks, not dogs or shepherds, but wolves." Bato spent the rest of his life in the Italian town of Ravenna.[28]

In the Roman period, Latin-speaking settlers from the entire Roman Empire settled among the Illyrians, and Roman soldiers were encouraged to retire in the region.[29]

The land was originally part of Illyria up until the Roman occupation. Following the split of the Roman Empire between 337 and 395 AD, Dalmatia and Pannonia became parts of the Western Roman Empire. Some claim that the region was conquered by the Ostrogoths in 455 AD. It subsequently changed hands between the Alans and the Huns. By the 6th century, Emperor Justinian had reconquered the area for the Byzantine Empire. The Illyrians were conquered by the Avars in the 6th century.

However, the Illyrians did not entirely vanish from Bosnia and Herzegovina with the arrival of new cultures. A large part of the remaining Illyrian culture intermingled with those of new settlers, some of it is believed to have been adopted by the latter, and some survived up to date, such as architectural remains (e.g. Daorson near Stolac), certain customs and traditions (e.g.tattooing, the 'gluha kola' dances, the 'ganga' singing, zig-zag and concentric circles in traditional decorations), place names (e.g. Čapljina, from 'čaplja', a south Slavic word for 'heron', coincides with 'Ardea', a Latin word for 'heron', and 'Ardea', in turn, bears striking similarity with the name of Ardiaei, the native Illyrian people of the wider Neretva valley region, where the town of Čapljina is situated), etc.[30]

Medieval Bosnia

Modern knowledge of the political situation in the west Balkans into the region in the late 9th century is scarce. The Early Slavic tribes also brought their mythology and pagan system of beliefs, the Rodovjerje. In particular, Perun, the highest god of the pantheon and the god of thunder and lightning is also commonly found in Bosnian toponymy, for instance in the name of the mountain Perun, near Vareš. Along with the Slavic settlers, the native Romanized population were already Christianized. Bosnia and Herzegovina, because of its geographic position and terrain, was probably one of the last areas to go through this process, which presumably originated from the urban centers along the Dalmatian coast. Thus, Slavic Bosnian tribes remained pagans for a longer time.

The principalities of Serbia and Croatia split control of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the 9th and 10th centuries, but by the High Middle Ages political circumstance led to the area being contested between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Byzantine Empire. Following another shift of power between the two in the early 12th century, Bosnia found itself outside the control of both and emerged as an independent state under the rule of local bans.[21]

The first Bosnian monarch was Ban Borić. The second was Ban Kulin whose rule marked the start of a controversy involving the Bosnian Church - considered heretical by the Roman Catholic Church. In response to Hungarian attempts to use church politics regarding the issue as a way to reclaim sovereignty over Bosnia, Kulin held a council of local church leaders to renounce the heresy and embraced Catholicism in 1203. Despite this, Hungarian ambitions remained unchanged long after Kulin's death in 1204, waning only after an unsuccessful invasion in 1254.

Bosnian history from then until the early 14th century was marked by a power struggle between the Šubić and Kotromanić families. This conflict came to an end in 1322, when Stephen II Kotromanić became Ban. By the time of his death in 1353, he was successful in annexing territories to the north and west, as well as Zahumlje and parts of Dalmatia. He was succeeded by his ambitious nephew Tvrtko who, following a prolonged struggle with nobility and inter-family strife, gained full control of the country in 1367. By the year 1377, Bosnia was elevated into a kingdom with the coronation of Tvrtko as the first Bosnian King in Mile near Visoko in the Bosnian heartland.[31][32][33]

Following his death in 1391 however, Bosnia fell into a long period of decline. The Ottoman Empire had already started its conquest of Europe and posed a major threat to the Balkans throughout the first half of the 15th century. Finally, after decades of political and social instability, the Kingdom of Bosnia ceased to exist in 1463 after its conquest by the Ottoman Empire.

Bosnia continued legally as a princedom under princes from the Berislavićs royal bloodline who helped keep the north and the west free for over a century (so that the westernmost Bihać fell only in 1593) while also holding the nation's capital Jajce, until 1527.[34] Two of the princes Berislavićs, Ivaniš and his son Stjepan, held also the title of Despot of Serbia. Berislavićs were deposed in 1534 when the Ottoman governor of Bosnia Gazi Husrev-beg had prince Stjepan Berislavić executed for refusing to abdicate to the Ottomans.[35]

Ottoman Bosnia (1527–1878)

Bosnia legally fell with the fall of capital Jajce, in 1527. The first occupation administration was established that same year. The Ottoman conquest of Bosnia marked a new era in the country's history and introduced drastic changes in the political and cultural landscape. The Ottomans allowed for the preservation of Bosnia's identity by incorporating it as an integral province of the Ottoman Empire with its historical name and territorial integrity — a unique case among subjugated states in the Balkans.[36]

Within Bosnia the Ottomans introduced a number of key changes in the territory's socio-political administration; including a new landholding system, a reorganization of administrative units, and a complex system of social differentiation by class and religious affiliation.[21]

The four centuries of Ottoman rule also had a drastic impact on Bosnia's population make-up, which changed several times as a result of the empire's conquests, frequent wars with European powers, forced and economic migrations, and epidemics. A native Slavic-speaking Muslim community emerged and eventually became the largest of the ethno-religious groups due to lack of strong Christian church organizations and continuous rivalry between the Orthodox and Catholic churches, while the indigenous Bosnian Church disappeared altogether (ostensibly by conversion of its members to Islam). The Ottomans referred to them as kristianlar while the Orthodox and Catholics were called gebir or kafir, meaning "unbeliever".[37] The Bosnian Franciscans (and the Catholic population as a whole) were to a minor extent protected by official imperial decree.[21]

As the Ottoman Empire continued their rule in the Balkans (Rumelia), Bosnia was somewhat relieved of the pressures of being a frontier province, and experienced a period of general welfare. A number of cities, such as Sarajevo and Mostar, were established and grew into regional centers of trade and urban culture and were then visited by Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi in 1648. Within these cities, various Ottoman Sultans financed the construction of many works of Bosnian architecture such as the country's first library in Sarajevo, madrassas, a school of Sufi philosophy, and a clock tower (Sahat Kula)[citation needed], bridges such as the Stari Most, the Tsar's Mosque and the Gazi Husrev-beg's Mosque.

Furthermore, several Bosnian Muslims played influential roles in the Ottoman Empire's cultural and political history during this time.[36] Bosnian recruits formed a large component of the Ottoman ranks in the battles of Mohács and Krbava field, while numerous other Bosnians rose through the ranks of the Ottoman military to occupy the highest positions of power in the Empire, including admirals such as Matrakçı Nasuh; generals such as Isa-Beg Isaković, Gazi Husrev-beg and Hasan Predojević and Sarı Süleyman Paşa; administrators such as Ferhat-paša Sokolović and Osman Gradaščević; and Grand Viziers such as the influential Mehmed Paša Sokolović and Damad Ibrahim Pasha. Some Bosnians emerged as Sufi mystics, scholars such as Muhamed Hevaji Uskufi Bosnevi, Ali Džabič; and poets in the Turkish, Albanian, Arabic, and Persian languages.[18]

However, by the late 17th century the Empire's military misfortunes caught up with the country, and the conclusion of the Great Turkish War with the treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 once again made Bosnia the Empire's westernmost province. The following century was marked by further military failures, numerous revolts within Bosnia, and several outbursts of plague[citation needed]. The Porte's efforts at modernizing the Ottoman state were met with distrust growing to hostility in Bosnia, where local aristocrats stood to lose much through the proposed reforms[clarification needed][citation needed].

This, combined with frustrations over territorial, political concessions in the north-east, and the plight of Slavic Muslim refugees arriving from the Sanjak of Smederevo into Bosnia Eyalet, culminated in a partially unsuccessful revolt by Husein Gradaščević, who endorsed a multicultural Bosnia Eyalet autonomous from the authoritarian rule of the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II, who persecuted, executed and abolished the Janissaries and reduced the role of autonomous Pasha's in Rumelia. Mahmud II sent his Grand Vizier to subdue Bosnia Eyalet and succeeded only with the reluctant assistance of Ali-paša Rizvanbegović.[18] Related rebellions would be extinguished by 1850, but the situation continued to deteriorate. Later agrarian unrest eventually sparked the Herzegovinian rebellion, a widespread peasant uprising, in 1875. The conflict rapidly spread and came to involve several Balkan states and Great Powers, a situation which eventually led to the Congress of Berlin and the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.[21]

Austro-Hungarian rule (1878–1918)

At the Congress of Berlin in 1878, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Gyula Andrássy obtained the occupation and administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and he also obtained the right to station garrisons in the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, which remained under Ottoman administration. The Sanjak preserved the separation of Serbia and Montenegro, and the Austro-Hungarian garrisons there would open the way for a dash to Salonika that "would bring the western half of the Balkans under permanent Austrian influence."[38] "High [Austro-Hungarian] military authorities desired [an...] immediate major expedition with Salonika as its objective."[39]

On 28 September 1878 the Finance Minister, Koloman von Zell, threatened to resign if the army, backed by the Archduke Albert, were allowed to advance to Salonika. In the session of the Hungarian Parliament of 5 November 1878 the Opposition proposed that the Foreign Minister should be impeached for violating the constitution with his policy during the Near East Crisis and by the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The motion lost 179 to 95. The gravest accusations were raised by the opposition rank and file against Andrassy.[39]

Although an Austro-Hungarian side quickly came to an agreement with Bosnians, tensions remained in certain parts of the country (particularly the south) and a mass emigration of predominantly Slavic dissidents occurred.[21] However, a state of relative stability was reached soon enough and Austro-Hungarian authorities were able to embark on a number of social and administrative reforms which intended to make Bosnia and Herzegovina into a "model colony".

With the aim of establishing the province as a stable political model that would help dissipate rising South Slav nationalism, Habsburg rule did much to codify laws, to introduce new political practices, and to provide for modernisation. The Austro-Hungarian Empire built the three Roman Catholic churches in Sarajevo and these three churches are among only 20 Catholic churches in the state of Bosnia.[dubious – discuss][citation needed]

In 1881, within three years of formal occupation of Bosnia Herzegovina, Austria-Hungary obtained German and the more important Russian approval of the annexation of these provinces at a time that suited Vienna. This mandate was formally ratified by the Dreikaiserbund (Three Emperor's Treaty) on 18 June of that year.[40] Upon the accession of Czar Nicholas II, however, the Russians reneged on the agreement, asserting in 1897 the need for special scrutiny of the Bosnian Annexation issue at an unspecified future date.[41]

External matters began to affect the Bosnian Protectorate, however, and its relationship with Austria-Hungary. A bloody coup occurred in Serbia, on 10 June 1903, which brought a radical anti-Austrian government into power in Belgrade.[42] Also, the revolt in the Ottoman Empire in 1908, raised concerns that the Istanbul government might seek the outright return of Bosnia Herzegovina. These factors caused the Austrian-Hungarian government to seek a permanent resolution of the Bosnian question sooner, rather than later.

On 2 July 1908, in response to the pressing of the Austrian-Hungarian claim, the Russian Imperial Foreign Minister Alexander Izvolsky offered to support the Bosnian annexation in return for Vienna's support for Russia's bid for naval access through the Dardanelles Straits into the Mediterranean.[45] With the Russians being, at least, provisionally willing to keep their word over Bosnia Herzegovina for the first time in 11 years, Austria-Hungary waited and then published the annexation proclamation on 6 October 1908. The international furor over the annexation announcement caused Izvolsky to drop the Dardanelles Straits question, altogether, in an effort to obtain a European conference over the Bosnian Annexation.[46] This conference never materialized and without British or French support, the Russians and their client state, Serbia, were compelled to accept the Austrian-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia Herzegovina in March 1909.

Political tensions culminated on 28 June 1914, when a Bosnian Serb nationalist youth named Gavrilo Princip, a member of the secret Serbian-supported movement, Young Bosnia, assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo—an event that proved to be the spark that set off World War I. At the end of the war, the Bosniaks had lost more men per capita than any other ethnic group in the Habsburg Empire whilst serving in the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Infantry of the Austro-Hungarian Army.[44] Nonetheless, Bosnia and Herzegovina as a whole managed to escape the conflict relatively unscathed.[36]

The Austro-Hungarian authorities established an auxiliary militia known as the Schutzkorps with a moot role in the empire's policy of anti-Serb repression.[47] Schutzkorps, predominantly recruited among the Muslim (Bosniak) population, were tasked with hunting down rebel Serbs (the Chetniks and Komiti)[48] and became known for their persecution of Serbs particularly in Serb populated areas of eastern Bosnia, where they partly retaliated against Serbian Chetniks who in fall 1914 had carried out attacks against the Muslim population in the area.[49][50] The proceedings of the Austro-Hungarian authorities led to around 5,500 citizens of Serb ethnicity in Bosnia and Herzegovina being arrested, and between 700 and 2,200 died in prison while 460 were executed.[48] Around 5,200 Serb families were forcibly expelled from Bosnia and Herzegovina.[48]

Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918–1941)

Following World War I, Bosnia and Herzegovina joined the South Slav Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (soon renamed Yugoslavia). Political life in Bosnia at this time was marked by two major trends: social and economic unrest over property redistribution, and formation of several political parties that frequently changed coalitions and alliances with parties in other Yugoslav regions.[36] The dominant ideological conflict of the Yugoslav state, between Croatian regionalism and Serbian centralization, was approached differently by Bosnia's major ethnic groups and was dependent on the overall political atmosphere.[21] The political reforms brought about in the newly established Yugoslavian kingdom saw few benefits for the Bosniaks; according to the 1910 final census of land ownership and population according to religious affiliation conducted in Austro-Hungary, Muslims (Bosniaks) owned 91.1%, Orthodox Serbians owned 6.0%, Croatian Catholics owned 2.6% and others, 0.3% of the property. Following the reforms Bosnian Muslims had a total of 1,175,305 hectares of agricultural and forest land taken away from them.[51]

Although the initial split of the country into 33 oblasts erased the presence of traditional geographic entities from the map, the efforts of Bosnian politicians such as Mehmed Spaho ensured that the six oblasts carved up from Bosnia and Herzegovina corresponded to the six sanjaks from Ottoman times and, thus, matched the country's traditional boundary as a whole.[21]

The establishment of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929, however, brought the redrawing of administrative regions into banates or banovinas that purposely avoided all historical and ethnic lines, removing any trace of a Bosnian entity.[21] Serbo-Croat tensions over the structuring of the Yugoslav state continued, with the concept of a separate Bosnian division receiving little or no consideration.

The Cvetković-Maček Agreement that created the Croatian banate in 1939 encouraged what was essentially a partition of Bosnia between Croatia and Serbia.[18] However the rising threat of Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany forced Yugoslav politicians to shift their attention. Following a period that saw attempts at appeasement, the signing of the Tripartite Treaty, and a coup d'état, Yugoslavia was finally invaded by Germany on 6 April 1941.[21]

World War II (1941–45)

Once the kingdom of Yugoslavia was conquered by Nazi forces in World War II, all of Bosnia was ceded to the Nazi puppet regime, Independent State of Croatia (NDH). The NDH leaders embarked on a campaign of extermination of Serbs, Jews, Romani, Croats who opposed the regime, communists and large numbers of Josip Broz Tito's Partisans by setting up a number of death camps.[52] The Ustaše recognized both Roman Catholicism and Islam as the national religions, but held the position that Eastern Orthodoxy, as a symbol of Serbian identity, was their greatest foe.[53] Between 197,000 and 580,000 Serbs were killed.[54] The United States Holocaust Museum puts the figure at 320,000–340,000 Serb victims in Croatia and Bosnia,[55] while the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum and Research Center concludes that "More than 500,000 Serbs were murdered in horribly sadistic ways, 250,000 were expelled, and another 200,000 were forced to convert".[56] Although Croatians were by far the largest ethnic group to constitute the Ustaše, the Vice President of the NDH and leader of the Yugoslav Muslim Organization Džafer Kulenović was a Muslim, and Muslims (Bosniaks) in total comprised nearly 12% of the Ustaše military and civil service authority.[57]

Many Serbs themselves took up arms and joined the Chetniks, a Serb nationalist movement with the aim of establishing an ethnically homogeneous 'Greater Serbian' state.[58] The Chetniks were responsible for widespread persecution and murder of non-Serbs and communist sympathizers, with the Muslim population of Bosnia, Herzegovina and Sandžak being a primary target.[59] Once captured, Muslim villages were systematically massacred by the Chetniks.[60] The total estimate of Muslims killed by Chetniks is between 80,000 and 100,000, most likely about 86,000 or 6.7 percent of their population (8.1 percent in Bosnia and Herzegovina alone).[61][62] Later, a number of Bosnian Muslims served in the Nazi Waffen-SS units.[63]

On 12 October 1941 a group of 108 notable Muslim citizens of Sarajevo signed the Resolution of Sarajevo Muslims by which they condemned the persecution of Serbs organized by Ustaše, made distinction between Muslims who participated in such persecutions and whole Muslim population, presented information about the persecutions of Muslims by Serbs and requested security for all citizens of the country, regardless of their identity.[64]

Starting in 1941, Yugoslav communists under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito organized their own multi-ethnic resistance group, the partisans, who fought against both Axis and Chetnik forces. On 29 November 1943 the Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation of Yugoslavia with Tito at its helm held a founding conference in Jajce where Bosnia and Herzegovina was reestablished as a republic within the Yugoslavian federation in its Habsburg borders.

Military success eventually prompted the Allies to support the Partisans, but Tito declined their offer to help and relied on his own forces instead. All the major military offensives by the antifascist movement of Yugoslavia against Nazis and their local supporters were conducted in Bosnia-Herzegovina and its peoples bore the brunt of fighting. More than 300,000 people died in Bosnia and Herzegovina in World War II.[65] At the end of the war the establishment of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, with the constitution of 1946, officially made Bosnia and Herzegovina one of six constituent republics in the new state.[21]

Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia (1945–1992)

Due to its central geographic position within the Yugoslavian federation, post-war Bosnia was selected as a base for the development of the military defense industry. This contributed to a large concentration of arms and military personnel in Bosnia; a significant factor in the war that followed the break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.[21] However, Bosnia's existence within Yugoslavia, for the large part, was a peaceful and very prosperous country, with high employment, a strong industrial and export oriented economy, good education system and social and medical security for every citizen of S. R. Bosnia and Herzegovina. Cooperation with World Brand names like Volkswagen, car factory Sarajevo, from 1972, Coca Cola from 1975, SKF Sweden from 1967, Marlboro, (U.S.) with a Tobacco factory in Sarajevo, Holiday Inn hotels, and after all, organisation of Olympic Winter Games 1984 in Sarajevo. Though considered a political backwater of the federation for much of the 1950s and 1960s, in the 1970s a strong Bosnian political elite arose, fueled in part by Tito's regime in the Non-Aligned Movement and Bosnians serving in Yugoslavia's diplomatic corps.

While working within the Socialist system, politicians such as Džemal Bijedić, Branko Mikulić and Hamdija Pozderac reinforced and protected the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina[66] Their efforts proved key during the turbulent period following Tito's death in 1980, and are today considered some of the early steps towards Bosnian independence. However, the republic did not escape the increasingly nationalistic climate of the time. With the fall of the Soviet Union and the start of the break-up of Yugoslavia, doctrine of tolerance began to lose its potency, creating an opportunity for nationalist elements in the society to spread their influence.

Bosnian War (1992–1995)

On 18 November 1990, the first multi-party parliamentary elections were held. A second round followed on 25 November, resulting in a national assembly where communist power was replaced by a coalition of three ethnically based parties.[67] Croatia and Slovenia's subsequent declarations of independence and the warfare that ensued placed Bosnia and Herzegovina and its three constituent peoples in an awkward position. A significant split soon developed on the issue of whether to stay with the Yugoslav federation (overwhelmingly favored among Serbs) or seek independence (overwhelmingly favored among Bosniaks and Croats).

The Serb members of parliament, consisting mainly of the Serb Democratic Party members, abandoned the central parliament in Sarajevo, and formed the Assembly of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 24 October 1991, which marked the end of the tri-ethnic coalition that governed after the elections in 1990. This Assembly established the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 9 January 1992, which became Republika Srpska in August 1992.

On 18 November 1991, the party branch in Bosnia and Herzegovina of the ruling party in the Republic of Croatia, the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), proclaimed the existence of the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia, as a separate "political, cultural, economic, and territorial whole", on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with Croat Defence Council (HVO) as its military part.[68] The Bosnian government did not recognize it. The Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina declared Herzeg-Bosnia illegal, first on 14 September 1992 and again on 20 January 1994.[69][70]

A declaration of the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 15 October 1991 was followed by a referendum for independence from Yugoslavia on 29 February and 1 March 1992 which was boycotted by the great majority of the Serbs. The turnout in the independence referendum was 63.4 percent and 99.7 percent of voters voted for independence.[71] Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence on 3 March 1992 and received international recognition the following month on April 6, 1992.[72] The Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was subsequently admitted as a member State of the United Nations on 22 May 1992.[73]

In the meantime, following a period of escalating tensions, the opening shots in the incipient Bosnian conflict were fired when Serb paramilitary forces attacked Bosnian Croat villages around Capljina on 7 March 1992 and Bosanski Brod and the Bosniak-majority town, Gorazde, on 15 March. These minor attacks were followed by much more serious Serb artillery attacks on Neum on 19 March and on Bosanski Brod on 24 March. It is disputed between Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs who the first casualties of the war were. Bosniaks regard the attack on the peace rally that was organized in Sarajevo on 5 April 1992 as marking the start of warfare between the three major communities. As the largest section of demonstrators moved towards the parliament building, Serb forces opened fire on the crowd from across the "Holiday Inn" hotel, killing two women, Suada Dilberović, a Bosniak, and Olga Sučić, a Croat.[67][74][75][76] The Vrbanja bridge where they perished has since then been renamed in their honour. Serbs consider the attack on a Serb wedding procession in downtown Sarajevo on 1 March 1992 to be the catalyst for the war. Nikola Gardović, the groom's father, was the only person killed.[77] The attacker was reportedly Ramiz Delalić, a Bosniak small-time gangster,[78] and it is alleged that the attack was provoked when the wedding guests brandished Serbian flags as the wedding procession moved through the old Muslim neighbourhood of Baščaršija.[79]

Discussions between Franjo Tuđman and Slobodan Milošević at the March 1991 Karađorđevo meeting are believed to have involved a plan to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina between Serbia and Croatia.[80] Following the declaration of independence of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Serbs attacked different parts of the country. The state administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina effectively ceased to function having lost control over the entire territory. The Serbs wanted control of large parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Milošević was widely accused of being the mastermind of a plan to build a "Greater Serbia", the RAM Plan. At the same time, the policies of the Republic of Croatia and its leader Franjo Tuđman towards Bosnia and Herzegovina were never totally transparent and always included Franjo Tuđman's ultimate aim of expanding Croatia's borders. Bosnian Muslims were an easy target, because the Bosnian government forces were poorly equipped and unprepared for the war.[81]

International recognition of Bosnia and Herzegovina increased diplomatic pressure for the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) to withdraw from the republic's territory which they officially did. However, in fact, the Bosnian Serb members of JNA simply changed insignia, formed the Army of Republika Srpska, and continued fighting. Armed and equipped from JNA stockpiles in Bosnia, supported by volunteers and various paramilitary forces from Serbia, and receiving extensive humanitarian, logistical and financial support from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Republika Srpska's offensives in 1992 managed to place much of the country under its control.[21]

(Photograph courtesy of the ICTY)

Initially, the Serb forces attacked the non-Serb civilian population in Eastern Bosnia. Once towns and villages were securely in their hands, the Serb forces—military, police, the paramilitaries and, sometimes, even Serb villagers—applied the same pattern: Bosniak houses and apartments were systematically ransacked or burnt down, Bosniak civilians were rounded up or captured, and sometimes beaten or killed in the process. 2.2 million refugees were displaced by the end of the war (of all three nationalities).[82]

Able-bodied men were separated from their families and interned in camps under a brutal regimen of abuse, murder, and sporadic group executions, whereas women and children were kept in unsanitary detention centers, deprived of food and water. Rape by Serb soldiers or policemen was commonplace at the detention centers, and victims included women and minors as young as 12 years old.[83]

Though on a significantly smaller scale, war crimes would later also be committed by Bosniaks and Croats as their military campaigns gained momentum, including the establishment of prison camps in which torture, murder and rape took place.[84][85][86][87]

In June 1992, the focus switched to Novi Travnik and Gornji Vakuf where the Croat Defence Council (HVO) efforts to gain control were resisted. On 18 June 1992 the Bosnian Territorial Defence in Novi Travnik received an ultimatum from the HVO which included demands to abolish existing Bosnia and Herzegovina institutions, establish the authority of the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia and pledge allegiance to it, subordinate the Territorial Defense to the HVO and expel Muslim refugees, all within 24 hours. The attack was launched on 19 June. The elementary school and the Post Office were attacked and damaged.[88]

Gornji Vakuf was initially attacked by Croats on 20 June 1992, but the attack failed. The Graz agreement caused deep division inside the Croat community and strengthened the separation group, which led to the conflict with Bosniaks. One of the primary pro-union Croat leaders, Blaž Kraljević (leader of the Croatian Defence Forces (HOS) armed group) was killed by HVO soldiers in August 1992, which severely weakened the moderate group who hoped to keep the Bosnian Croat alliance alive.[89]

The situation became more serious in October 1992 when Croat forces attacked the Bosniak population in Prozor. According to Jadranko Prlić indictment, HVO forces cleansed most of the Muslims from the town of Prozor and several surrounding villages.[68]

By 1993 when an armed conflict erupted between the predominantly Bosniak government in Sarajevo and the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia, about 70% of the country was controlled by Republika Srpska. Ethnic cleansing and civil rights violations against non-Serbs were rampant in these areas. DNA teams have been used to collect evidence of the atrocities committed by Serbian forces during these campaigns.[90] The single most prominent example was the Srebrenica massacre, ruled a genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. An estimated 8,372 Bosnians were killed by the Serbian political authorities.[91] The Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) ran active military intelligence program during the Bosnian War which started in 1992 lasting until 1995. Executed and supervised by General Javed Nasir, the program distributed and coordinated the systematic supply of arms to various groups of Bosnian fighters in their fight against the Serbian war missions.[92]

In March 1994, the signing of the Washington Accords between the leaders of the republican government and Herzeg-Bosnia led to the creation of a joint Bosniak-Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which absorbed the territory of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia and that held by the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Federation soon liberated the small Autonomous Province of Western Bosnia.

Following the Srebrenica genocide, a NATO bombing campaign began in August 1995 against the Army of Republika Srpska. Meanwhile, a ground offensive by the allied forces of Croatia and Bosnia, based on the Split Agreement signed by Tudjman and Izetbegović, pushed the Serbs away from territories held in western Bosnia which paved the way to negotiations. In December 1995, the signing of the Dayton Agreement in Dayton, Ohio, by the Chairman of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Alija Izetbegović), Croatia (Franjo Tuđman) and Serbia (Slobodan Milošević) brought a halt to the fighting, roughly establishing the basic structure of the present-day state. A NATO-led peacekeeping force was immediately dispatched to Bosnia to enforce the agreement.

The number of identified victims is currently at 97,207 (civilian and military casualties). These include 64,341 Bosniaks, 24,726 Serbs, and 7,602 Croats.[93] Recent research estimates the total number to be no more than 110,000 killed (civilians and military),[94][95][96] and 1.8 million displaced. Those declared missing are being investigated by International Commission on Missing Persons.

According to numerous International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) judgements, the conflict involved Bosnia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (subsequently Serbia and Montenegro)[97] as well as Croatia.[98]

At the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the Bosnian government charged Serbia of complicity in genocide in Bosnia during the war. The ICJ ruling of 26 February 2007 effectively determined the war's nature to be international, though exonerating Serbia of direct responsibility for the genocide committed by Serb forces of Republika Srpska. The ICJ concluded, however, that Serbia failed to prevent genocide committed by Serb forces and failed to punish those who carried out the genocide<aside>in particular, General Ratko Mladić</aside>and bring them to justice.[99] Mladić was arrested in a village in northern Serbia on 26 May 2011 and, among other genocide and war crime charges, accused of directly orchestrating and overseeing the slaughter of 8,000 Bosniak men and boys.[100]

The judges ruled that the criteria for genocide with the specific intent (dolus specialis) to destroy Bosnian Muslims were met only in Srebrenica or Eastern Bosnia in 1995.[101] The court concluded that the crimes committed during the 1992–1995 war may, according to international law, amount to crimes against humanity, but that these acts did not in themselves constitute genocide.[102] The Court further decided that Serbia was the only respondent party in the case after Montenegro's declaration of independence in June 2006, but that "any responsibility for past events involved, at the relevant time, the composite State of Serbia and Montenegro".[103]

High-ranking Croat and Bosniak officials have been convicted or indicted for war crimes as well on charges related to the murder, rape, torture, and imprisonment of civilians.[104] Serbs have accused Sarajevo authorities of practicing selective justice by actively prosecuting Serbs while ignoring or downplaying Bosniak war crimes.[105] Bodies of victims are still being unearthed two decades later. In July 2014 the remains of 284 victims, unearthed from the Tomasica mass grave near the town of Prijedor, were laid to rest in a mass ceremony with thousands of relatives from Bosnia and across Europe participating.[106]

Anti-government protests (2014)

On 4 February 2014, the anti-government protests dubbed the Bosnian Spring, name taken from the Arab Spring, began in the northern town of Tuzla. Workers from several factories which were privatised and which have now gone bankrupt united to demand action over jobs, unpaid salaries and pensions.[107] Soon protests spread to the rest of the country with violent clashes reported in close to 20 towns, biggest of which were in Sarajevo, Zenica, Mostar, Bihać, Brčko and Tuzla. [108] The Bosnian news media reported that hundreds had been injured during the protests, including dozens of police officers, with bursts of violence in Sarajevo, in the northern city of Tuzla, in Mostar in the south, and in Zenica in central Bosnia. Hundreds of people also gathered in support of anti-government protests in the town of Banja Luka.[109][110][111]

The protests mark the largest outbreak of public anger over high unemployment and two decades of political inertia in the country since the end of the Bosnian War in 1995.[112]

Geography

Bosnia is located in the western Balkans, bordering Croatia (932 km or 579 mi) to the north and south-west, Serbia (302 km or 188 mi) to the east, and Montenegro (225 km or 140 mi) to the southeast. It lies between latitudes 42° and 46° N, and longitudes 15° and 20° E.

The country's name comes from the two regions Bosnia and Herzegovina, which have a very vaguely defined border between them. Bosnia occupies the northern areas which are roughly four-fifths of the entire country, while Herzegovina occupies the rest in the southern part of the country.

The country is mostly mountainous, encompassing the central Dinaric Alps. The northeastern parts reach into the Pannonian basin, while in the south it borders the Adriatic. The Dinaric Alps generally run in an east-west direction, and get higher towards the south. The highest point of the country is peak Maglić at 2,386 m, at the Montenegrin border. Major mountains include Kozara, Grmeč, Vlašić, Čvrsnica, Prenj, Romanija, Jahorina, Bjelašnica and Treskavica.

Overall, close to 50% of Bosnia and Herzegovina is forested. Most forest areas are in Central, Eastern and Western parts of Bosnia. Herzegovina has drier Mediterranean climate, with dominant karst topography. Northern Bosnia (Posavina) contains very fertile agricultural land along the river Sava and the corresponding area is heavily farmed. This farmland is a part of the Parapannonian Plain stretching into neighboring Croatia and Serbia. The country has only 20 kilometres (12 miles) of coastline,[6] around the town of Neum in the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton. Although the city is surrounded by Croatian peninsulas, by the international law, Bosnia and Herzegovina has a right of passage to the outer sea.

The major cities are Sarajevo, Banja Luka in the northwest region known as Bosanska Krajina, Bijeljina and Tuzla in the northeast, Zenica and Doboj in the central part of Bosnia and Mostar, the largest city in Herzegovina.

There are seven major rivers in Bosnia and Herzegovina[113]

- The Sava is the largest river of the country, but it only forms its northern natural border with Croatia. It drains 76%[113] of the country's territory into the Danube and the Black Sea. Bosnia and Herzegovina is therefore also a member of the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR).

- The Una, Sana and Vrbas are right tributaries of Sava river. They are located in the northwestern region of Bosanska Krajina.

- The Bosna river gave its name to the country, and is the longest river fully contained within it. It stretches through central Bosnia, from its source near Sarajevo to Sava in the north.

- The Drina flows through the eastern part of Bosnia, and for the most part it forms a natural border with Serbia.

- The Neretva is the major river of Herzegovina and the only major river that flows south, into the Adriatic Sea.

Phytogeographically, Bosnia and Herzegovina belongs to the Boreal Kingdom and is shared between the Illyrian province of the Circumboreal Region and Adriatic province of the Mediterranean Region. According to the WWF, the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina can be subdivided into three ecoregions: the Pannonian mixed forests, Dinaric Mountains mixed forests and Illyrian deciduous forests.

Bosnian Pyramids

The Bosnian pyramids are a pseudo-archaeological[114] claim promoted by author Semir Osmanagić, that a cluster of natural hills in central Bosnia and Herzegovina are the largest human-made ancient pyramids on Earth. The hills are located near the town of Visoko, northwest of Sarajevo. Visočica hill, where the Old town of Visoki was once sited, became the focus of international attention in October 2005, following a news-media campaign by Osmanagić and his supporters.

Government and politics

Bosnia and Herzegovina is an international protectorate under absolutist rule by the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina. It has a bicameral legislature and a three-member Presidency composed of a member of each major ethnic group. However, the central government's power is highly limited, as the country is largely decentralized and comprises two autonomous entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska, with a third region, the Brčko District, governed under local government. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is itself complex and consists of 10 federal units – cantons. The country is a potential candidate for membership to the European Union and has been a candidate for North Atlantic Treaty Organisation membership since April 2010, when it received a Membership Action Plan at a summit in Tallinn[which?]. Additionally, the country has been a member of the Council of Europe since April 2002 and a founding member of the Mediterranean Union upon its establishment in July 2008.

Administrative division

Bosnia and Herzegovina has several levels of political structuring, according to the Dayton accord. The most important of these levels is the division of the country into two entities: Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina covers 51% of Bosnia and Herzegovina's total area, while Republika Srpska covers 49%. The entities, based largely on the territories held by the two warring sides at the time, were formally established by the Dayton peace agreement in 1995 because of the tremendous changes in Bosnia and Herzegovina's ethnic structure. Since 1996 the power of the entities relative to the State government has decreased significantly. Nonetheless, entities still have numerous powers to themselves. The Brčko District in the north of the country was created in 2000 out of land from both entities. It officially belongs to both, but is governed by neither, and functions under a decentralized system of local government. For election purposes, Brčko District voters can choose to participate in either the Federation or Republika Srpska elections. The Brčko District has been praised for maintaining a multiethnic population and a level of prosperity significantly above the national average.[115]

The third level of Bosnia and Herzegovina's political subdivision is manifested in cantons. They are unique to the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina entity, which consists of ten of them. All of them have their own cantonal government, which is under the law of the Federation as a whole. Some cantons are ethnically mixed and have special laws implemented to ensure the equality of all constituent people.

The fourth level of political division in Bosnia and Herzegovina is the municipalities. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is divided in 74 municipalities, and Republika Srpska in 63. Municipalities also have their own local government, and are typically based on the most significant city or place in their territory. As such, many municipalities have a long tradition and history with their present boundaries. Some others, however, were only created following the recent war after traditional municipalities were split by the Inter-Entity Boundary Line. Each canton in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina consists of several municipalities, which are divided into local communities.

Besides entities, cantons, and municipalities, Bosnia and Herzegovina also has four "official" cities. These are: Banja Luka, Mostar, Sarajevo, and East Sarajevo. The territory and government of the cities of Banja Luka and Mostar corresponds to the municipalities of the same name, while the cities of Sarajevo and East Sarajevo officially consist of several municipalities. Cities have their own city government whose power is in between that of the municipalities and cantons (or the entity, in the case of Republika Srpska).

Protectorate

As a result of the Dayton Accords, the civilian peace implementation is supervised by the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina selected by the Peace Implementation Council. The High Representative has many governmental and legislative powers, including the dismissal of elected and non-elected officials. More recently, several central institutions have been established (such as defense ministry, security ministry, state court, indirect taxation service and so on) in the process of transferring part of the jurisdiction from the entities to the state.

The Parliamentary Assembly is a parallel lawmaking body in Bosnia and Herzegovina, in addition to the High Representative who can enact laws at will. It consists of two houses: the House of Peoples and the House of Representatives. The House of Peoples has 15 delegates chosen by parliaments of the entities, two-thirds of which come from the Federation (5 Croat and 5 Bosniaks) and one-third from the Republika Srpska (5 Serbs). The House of Representatives is composed of 42 Members elected by the people under a form of proportional representation (PR), two-thirds elected from the Federation and one-third elected from the Republika Srpska.

Societal repercussions

The representation of the government of Bosnia and Herzegovina is by elites who represent the country's three major groups, with each having a guaranteed share of power. This makes the country a cultural hegemony.

The Chair of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina rotates among three members (Bosniak, Serb, Croat), each elected as the Chair for an eight-month term within their four-year term as a member. The three members of the Presidency are elected directly by the people with Federation voters voting for the Bosniak and the Croat, and the Republika Srpska voters for the Serb.

The Chair of the Council of Ministers is nominated by the Presidency and approved by the House of Representatives. He or she is then responsible for appointing a Foreign Minister, Minister of Foreign Trade, and others as appropriate.

Judiciary

The Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina is the supreme, final arbiter of legal matters. It is composed of nine members: four members are selected by the House of Representatives of the Federation, two by the Assembly of the Republika Srpska, and three by the President of the European Court of Human Rights after consultation with the Presidency, but cannot be Bosnian citizens.

However, the highest political authority in the country is the High Representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the chief executive officer for the international civilian presence in the country. Since 1995, the High Representative has been able to bypass the elected parliamentary assembly, and since 1997 has been able to remove elected officials. The methods selected by the High Representative have been criticized as undemocratic.[116] International supervision is to end when the country is deemed politically and democratically stable and self-sustaining.

Military

The Armed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina were unified into a single entity in 2005, with the merger of the Army of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Army of Republika Srpska, which had defended their respective regions. The Ministry of Defense had been founded in 2004. The Bosnian military consists of the Bosnian Ground Forces and Air Force and Air Defense. The Ground Forces number 16,500 active and 5,000 reserve personnel. They are armed with a mix of American, Yugoslavian, Soviet, and European-made weaponry, vehicles, and military equipment. The Air Force and Air Defense Forces has 3,000 personnel and about 62 aircraft. The Air Defense Forces operate MANPAD hand-held missiles, surface-to-air missile (SAM) batteries, anti-aircraft cannons, and radar. Almost all of its anti-aircraft equipment is of Soviet origin, though it also operates some U.S. and Swedish hardware.

The Ministry of Defence of Bosnia and Herzegovina cooperated on their first ever mission to enlist the military to ISAF peace missions to Afghanistan, Iraq and Democratic Republic of Congo in 2007. From 5 officers, consuming the rank as officers/advisors DROC. 45 soldiers, consuming the rank as base cooperatives, protecting areas and assisting needed medical help, but commonly security AFG. 85 soldiers, possessing the ranks as guard of national bases and rare patrols around near areas of the sector IRQ. All three deployed groups were pronounced the highest motivation and awards, as well as the Ministry of Defence of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This procedure is still on-going.

Foreign relations

EU integration is one of the main political objectives of Bosnia and Herzegovina; it initiated the Stabilisation and Association Process in 2007. Countries participating in the SAP have been offered the possibility to become, once they fulfill the necessary conditions, Member States of the EU. Bosnia and Herzegovina is therefore a potential candidate country for EU accession.[117] The implementation of the Dayton Accords of 1995 has focused the efforts of policymakers in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as the international community, on regional stabilization in the countries-successors of the former Yugoslavia. Within Bosnia and Herzegovina, relations with its neighbors of Croatia, Serbia and Montenegro have been fairly stable since the signing of the Dayton Agreement in 1995.

On 23 April 2010, Bosnia and Herzegovina received the Membership Action Plan from NATO, which is the last step before full membership in the alliance. Bosnia and Herzegovina is also a member of the Group of 77.

Royal claim

Head of the deposed Bosnian royal family Omerbašić Berislavić Nemanjić has claimed the country's sovereignty since 2010.[118] The claim has been maintained for prescription by actively protesting sovereignty usurpation.[119][120][121]

Demographics

Bosnia and Herzegovina is home to three ethnic "constituent peoples": Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats. According to the 1991 census, Bosnia and Herzegovina had a population of 4,377,000, while the 1996 UNHCR unofficial census showed a decrease to 3,920,000.[citation needed] Large population migrations during the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s have caused demographic shifts in the country. Between 1991 and 2013, political disagreements made it impossible to organize a census. A census has been planned for 2012.,[122] but that date has been delayed until 2013; this was delayed until October 2013. The 2013 census found a total population of 3,791,622 people in 1.16 million households; this is 585,411 fewer people than the 1991 census.[123]

Ethnically, according to data from 2000 cited by the Central Intelligence Agency, Bosniaks constitute 48% of the population, Serbs 37.1%, Croats 14.3%, and others form 0.6%.[1] According to unofficial estimates from the Bosnian State Statistics Agency cited by the US Department of State in 2008, 45 percent of the population identify religiously as Muslim, 36 percent as Serb Orthodox, 15 percent as Roman Catholic, 1 percent as Protestant, and 3 percent other (mostly atheists, Jews, and others).[124] Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian are official languages, but all three are mutually intelligible. 54% of Muslims are non-denominational Muslims.[125]

Sarajevo is home to 438,443 inhabitants in its urban area.[126] Due to its population and its importance in South East Europe, Sarajevo is a metropolis and the wealthiest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[citation needed]

Economy

Bosnia faces the dual-problem of rebuilding a war-torn country and introducing transitional liberal market reforms to its formerly mixed economy. One legacy of the previous era is a strong industry; under former republic president Džemal Bijedić and SFRY President Josip Broz Tito, metal industries were promoted in the republic, resulting in the development of a large share of Yugoslavia's plants; S.R. Bosnia and Herzegovina had a very strong industrial export oriented economy in the 1970s and 1980s, with large scale exports worth millions of US$.

For most of Bosnia's history, agriculture has been conducted on privately owned farms; Fresh food has traditionally been exported from the republic.[128]

The war in the 1990s caused a dramatic change in the Bosnian economy.[129] GDP fell by 75% and the destruction of physical infrastructure devastated the economy.[130] With much of the production capacity unrestored, the Bosnian economy still faces considerable difficulties. Figures show GDP and per capita income increased 10% from 2003 to 2004; this and Bosnia's shrinking national debt being negative trends,and high unemployment 44.6% and a large trade deficit remain cause for concern.

The national currency is the (Euro-pegged) Convertible Mark (KM), controlled by the currency board. Annual inflation is the lowest relative to other countries in the region at 1.9% in 2004.[131] The international debt was $3.1 billion (2005 est) – the smallest amount of debt owed of all the former Yugoslav republics. Real GDP growth rate was 5% for 2004 according to the Bosnian Central Bank of BiH and Statistical Office of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Bosnia and Herzegovina has one of the lowest income equality rankings in the world, ranking eighth out of 193 nations.[132]

According to Eurostat data, Bosnia and Herzegovina's PPS GDP per capita stood at 29 per cent of the EU average in 2010.[133]

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced a loan to Bosnia worth $500 million to be delivered by Stand-By Arrangement. This is scheduled to be approved in September 2012.[134]

Overall value of foreign direct investment (1999–2013):[135]

- 1999: €166 million

- 2000: €159 million

- 2001: €133 million

- 2002: €282 million

- 2003: €338 million

- 2004: €534 million

- 2005: €421 million

- 2006: €556 million

- 2007: €1.329 billion

- 2008: €684 billion

- 2009: €180 billion

- 2010: €307 billion

- 2011: €357 billion

- 2012: €273 billion

- 2013: €214 billion

- 2014 (January–September): €284 billion

The top investor countries (May 1994 – December 2013)

- Austria (€1.329 billion)

- Serbia (€1.002 million)

- Croatia (€733 million)

- Slovenia (€499 million)

- Russia (€343 million)

- Germany (€333 million)

- Switzerland (€273 million)

- Netherlands (€206 million)

Foreign investments by sector for (May 1994 – December 2013):

- 32% Manufacturing

- 22% Banking

- 15% Telecommunication

- 11% Trade

- 5% Estate

- 4% Services

- 11% Other

The United States Embassy in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina produces the Country Commercial Guide – an annual report that delivers a comprehensive look at Bosnia and Herzegovina’s commercial and economic environment, using economic, political, and market analysis. It can be viewed on Embassy Sarajevo’s website.

Before 1990s and consequences of the Bosnian war 1992-95