Urdu: Difference between revisions

m Outdated and inaccurate considering Urdu is national language of Pakistan and language of the Muslims in India |

|||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

|date = 2010 |

|date = 2010 |

||

|ref = ne2007 |

|ref = ne2007 |

||

|speakers2= |

|||

|speakers2= Second language: 94 million in Pakistan (1999)<ref>{{e18|urd}}</ref> |

|||

|familycolor=Indo-European |

|familycolor=Indo-European |

||

|fam2=[[Indo-Iranian languages|Indo-Iranian]] |

|fam2=[[Indo-Iranian languages|Indo-Iranian]] |

||

Revision as of 23:10, 10 May 2015

| Urdu | |

|---|---|

| اُردُو | |

Urdu in Perso-Arabic script (Nastaliq style) | |

| Pronunciation | IPA: [ˈʊrd̪u] |

| Native to | Pakistan and India[1] |

Native speakers | 65 million (2010)[2] |

| Arabic (Urdu alphabet) Devanagari Indian Urdu Braille (Bharati) Pakistani Urdu Braille | |

| Indian Signing System (ISS)[4] Signed Urdu[5] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ur |

| ISO 639-2 | urd |

| ISO 639-3 | urd |

| Glottolog | urdu1245 |

| Linguasphere | 59-AAF-q (with Hindi, including 58 varieties: 59-AAF-qaa to 59-AAF-qil) |

Areas where Urdu is official or co-official with local language

(Other) areas where only a regional language is official | |

Urdu (/ˈʊərduː/; Template:Lang-ur ALA-LC: [Urdū] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: urdu (help); IPA: [ˈʊrd̪uː] ), or more precisely Modern Standard Urdu, is a standardized register of the Hindustani language. Urdu is historically associated with the Muslims of the region of Hindustan. It is the national language and lingua franca of Pakistan, and an official language of six Indian states and one of the 22 scheduled languages in the Constitution of India. Apart from specialized vocabulary, Urdu is mutually intelligible with Standard Hindi, which is associated with the Hindu community. The Urdu language received recognition and patronage under the British Raj when the British replaced the Persian and local official languages of North Indian states with the Urdu and English language in 1837.[7]

Origin

Urdu formed from Khariboli—a Prakrit spoken in North India—by adding Persian and Arabic words to it.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

But the word Urdu is derived from the same Turkic word ordu (army) that has given English horde.[14] However, Turkish borrowings in Urdu are minimal.[15] The words that Urdu has borrowed from Turkish and Arabic have been borrowed through Farsi and hence are a Persianized version of the original word, for instance the Arabic 'teh marbuta ( ة ) changes to heh ( ه ) or teh ( ت ).[16] [note 1]

The Mughal Empire's official language was Persian [1]. With the advent of the British Raj Persian language was replaced by the Hindustani written in the Persian script and this script was used by both Hindus and Muslims. The name Urdu was first used by the poet Ghulam Hamadani Mushafi around 1780.[17][18]: 18 From the 13th century until the end of the 18th century Urdu was commonly known as Hindi.[18]: 1 The language was also known by various other names such as Hindavi and Dehlavi.[18]: 21–22 The communal nature of the language lasted until it replaced Persian as the official language in 1837 and was made co-official, along with English. Urdu was promoted in British India by British policies to counter the previous emphasis on Persian.[19] This triggered a Hindu backlash in northwestern India, which argued that the language should be written in the native Devanagari script. Thus a new literary register, called "Hindi", replaced traditional Hindustani as the official language of Bihar in 1881, establishing a sectarian divide of "Urdu" for Muslims and "Hindi" for Hindus, a divide that was formalized with the division of India and Pakistan after independence (though there are Hindu poets who continue to write in Urdu to this day, with post-independence examples including Gopi Chand Narang and Gulzar). At independence, Pakistan established a highly Persianized literary form of Urdu as its national language.

There have been attempts to "purify" Urdu and Hindi, by purging Urdu of Sanskrit loan words, and Hindi of Persian loan words, and new vocabulary draws primarily from Persian and Arabic for Urdu and from Sanskrit for Hindi. This has primarily affected academic and literary vocabulary, and both national standards remain heavily influenced by both Persian and Sanskrit.[20] English has exerted a heavy influence on both as a co-official language.[21]

Speakers and geographic distribution

There are between 60 and 70 million native speakers of Urdu: there were 52 million in India per the 2001 census, some 6% of the population;[22] approximately 10 million in Pakistan or 7.57% per the 1998 census;[23] and several hundred thousand in the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, United States, and Bangladesh (where it is called "Bihari").[24] However, a knowledge of Urdu allows one to speak with far more people than that, because Hindustani, of which Urdu is one variety, is the fourth most commonly spoken language in the world, after Mandarin, English, and Spanish.[25][26] Because of the difficulty in distinguishing between Urdu and Hindi speakers in India and Pakistan, as well as estimating the number of people for whom Urdu is a second language, the estimated number of speakers is uncertain and controversial.

Owing to interaction with other languages, Urdu has become localized wherever it is spoken, including in Pakistan itself. Urdu in Pakistan has undergone changes and has lately incorporated and borrowed many words from regional languages like Pashto, Punjabi, Sindhi and Balti as well as former East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) Bengali language, thus allowing speakers of the language in Pakistan to distinguish themselves more easily and giving the language a decidedly Pakistani flavour. Similarly, the Urdu spoken in India can also be distinguished into many dialects like Dakhni (Deccan) of South India, and Khariboli of the Punjab region since recent times. Because of Urdu's similarity to Hindi, speakers of the two languages can easily understand one another if both sides refrain from using specialized vocabulary. The syntax (grammar), morphology, and the core vocabulary are essentially identical. Thus linguists usually count them as one single language and contend that they are considered as two different languages for socio-political reasons.[27]

In Pakistan Urdu is mostly learned as a second or a third language as nearly 93% of Pakistan's population has a native language other than Urdu. Despite this, Urdu was chosen as a token of unity and as a lingua franca so as not to give any native Pakistani language preference over the other. Urdu is therefore spoken and understood by the vast majority in some form or another, including a majority of urban dwellers in such cities as Karachi, Lahore, Sialkot, Rawalpindi, Islamabad, Multan, Faisalabad, Hyderabad, Peshawar, Quetta, Jhang, Sargodha and Skardu. It is written, spoken and used in all provinces/territories of Pakistan despite the fact that the people from differing provinces may have different indigenous languages, as from the fact that it is the "base language" of the country. For this reason, it is also taught as a compulsory subject up to higher secondary school in both English and Urdu medium school systems. This has produced millions of Urdu speakers from people whose native language is one of the State languages of Pakistan such as Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi, Balochi, Potwari, Hindko, Pahari, Saraiki, Balti, and Brahui who can read and write only Urdu. It is absorbing many words from the regional languages of Pakistan. This variation of Urdu is sometimes referred to as Pakistani Urdu.

So although most of the population is conversant in Urdu, it is the first language of only an estimated 7% of the population who are mainly Muslim immigrants (known as Muhajir in Pakistan) from different parts of South Asia. The regional languages are also being influenced by Urdu vocabulary. There are millions of Pakistanis whose native language is not Urdu, but because they have studied in Urdu medium schools, they can read and write Urdu along with their native language. Most of the nearly five million Afghan refugees of different ethnic origins (such as Pashtun, Tajik, Uzbek, Hazarvi, and Turkmen) who stayed in Pakistan for over twenty-five years have also become fluent in Urdu. With such a large number of people(s) speaking Urdu, the language has in recent years acquired a peculiar Pakistani flavour further distinguishing it from the Urdu spoken by native speakers and diversifying the language even further.

A great number of newspapers are published in Urdu in Pakistan, including the Daily Jang, Nawa-i-Waqt, Millat, among many others (see List of newspapers in Pakistan#Urdu language Newspapers).

In India, Urdu is spoken in places where there are large Muslim minorities or cities that were bases for Muslim Empires in the past. These include parts of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra (Marathwada), Karnataka and cities such as Lucknow, Delhi, Bareilly, Meerut, Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Roorkee, Deoband, Moradabad, Azamgarh, Bijnor, Najibabad, Rampur, Aligarh, Allahabad, Gorakhpur, Agra, Kanpur, Badaun, Bhopal, Hyderabad, Aurangabad, Bengaluru, Kolkata, Mysore, Patna, Gulbarga, Nanded, Malegaon, Bidar, Ajmer, and Ahmedabad.[28] Some Indian schools teach Urdu as a first language and have their own syllabus and exams. Indian madrasahs also teach Arabic as well as Urdu. India has more than 3,000 Urdu publications including 405 daily Urdu newspapers. Newspapers such as Neshat News Urdu, Sahara Urdu, Daily Salar, Hindustan Express, Daily Pasban, Siasat Daily, The Munsif Daily and Inqilab are published and distributed in Bengaluru, Malegaon, Mysore, Hyderabad, and Mumbai (see List of newspapers in India).

Outside South Asia, it is spoken by large numbers of migrant South Asian workers in the major urban centres of the Persian Gulf countries and Saudi Arabia. Urdu is also spoken by large numbers of immigrants and their children in the major urban centres of the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Germany, Norway, and Australia. Along with Arabic, Urdu is among the immigrant languages with the most speakers in Catalonia, leading to fears of linguistic ghettos.[29]

Official status

Urdu is the national and one of the two official languages of Pakistan, along with English, and is spoken and understood throughout the country, whereas the state-by-state languages (languages spoken throughout various regions) are the provincial languages. Only 7.57% of Pakistanis have Urdu as their mother language,[30] but Urdu is understood all over Pakistan. It is used in education, literature, office and court business.[31] It holds in itself a repository of the cultural and social heritage of the country.[32] Although English is used in most elite circles, and Punjabi has a plurality of native speakers, Urdu is the lingua franca and national language of Pakistan. In practice English is used instead of Urdu in the higher echelons of government.[33]

Urdu is also one of the officially recognized languages in India and has official language status in the Indian states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar,[34] Telangana, Jammu and Kashmir and the national capital, New Delhi.

In Jammu and Kashmir, section 145 of the Kashmir Constitution provides: "The official language of the State shall be Urdu but the English language shall unless the Legislature by law otherwise provides, continue to be used for all the official purposes of the State for which it was being used immediately before the commencement of the Constitution."[35]

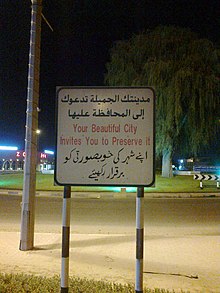

The importance of Urdu in the Muslim world is visible in the Islamic Holy cities of Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia, where most informational signage is written in Arabic, English and Urdu, and sometimes in other languages.[36]

Dialects

Urdu has a few recognised dialects, including Dakhni, Rekhta, and Modern Vernacular Urdu (based on the Khariboli dialect of the Delhi region). Dakhni (also known as Dakani, Deccani, Desia, Mirgan) is spoken in Deccan region of southern India. It is distinct by its mixture of vocabulary from Marathi and Konkani, as well as some vocabulary from Arabic, Persian and Turkish that are not found in the standard dialect of Urdu. Dakhini is widely spoken in all parts of Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. Urdu is read and written as in other parts of India. A number of daily newspapers and several monthly magazines in Urdu are published in these states. In terms of pronunciation, the easiest way to recognize a native speaker is their pronunciation of the letter "qāf" (ق) as "k̲h̲e" (خ).

Urdu spoken in Indian state of Odisha is different from Urdu spoken in other areas; it is a mixture of Oriya and Bihari.[citation needed]

Comparison with Modern Standard Hindi

Standard Urdu is often contrasted with Standard Hindi. Apart from religious associations, the differences are largely restricted to the standard forms: Standard Urdu is conventionally written in the Nastaliq style of the Persian alphabet and relies heavily on Persian and Arabic as a source for technical and literary vocabulary,[37] whereas Standard Hindi is conventionally written in Devanāgarī and draws on Sanskrit.[38] However, both have large numbers of Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit words, and most linguists consider them to be two standardized forms of the same language,[39][40] and consider the differences to be sociolinguistic,[41] though a few classify them separately.[42] Old Urdu dictionaries also contain most of the Sanskrit words now present in Hindi.[43][44] Mutual intelligibility decreases in literary and specialized contexts that rely on educated vocabulary. Further, it is quite easy in a longer conversation to distinguish differences in vocabulary and pronunciation of some Urdu phonemes. Due to religious nationalism since the partition of British India and continued communal tensions, native speakers of both Hindi and Urdu frequently assert them to be distinct languages, despite the numerous similarities between the two in a colloquial setting.

The barrier created between the Hindi and Urdu is eroding: Hindi-speakers are comfortable with using Persian-Arabic borrowed words[45] and Urdu-speakers are also comfortable with using Sanskrit terminology.[46][47]

Vocabulary

The language's Indo-Aryan base has been enriched by borrowing from Persian and Arabic. There are also a smaller number of borrowings from Chagatai, Portuguese, and more recently English. Many of the words of Arabic origin have been adopted through Persian and have different pronunciations and nuances of meaning and usage than they do in Arabic.

Levels of formality

Urdu in its less formalised register has been referred to as a rek̤h̤tah (ریختہ, [reːxt̪aː]), meaning "rough mixture". The more formal register of Urdu is sometimes referred to as zabān-i Urdū-yi muʿallá (زبانِ اُردُوئے معلّٰى [zəbaːn eː ʊrd̪u eː moəllaː]), the "Language of the Exalted Camp", referring to the Imperial army.[48]

The etymology of the word used in the Urdu language for the most part decides how polite or refined one's speech is. For example, Urdu speakers would distinguish between پانی pānī and آب āb, both meaning "water"; the former is used colloquially and has older Indic origins, whereas the latter is used formally and poetically, being of Persian origin.

If a word is of Persian or Arabic origin, the level of speech is considered to be more formal and grand. Similarly, if Persian or Arabic grammar constructs, such as the izafat, are used in Urdu, the level of speech is also considered more formal and grand. If a word is inherited from Sanskrit, the level of speech is considered more colloquial and personal.[49] This distinction is similar to the division in English between words of Latin, French and Old English origins.[citation needed]

Politeness

Urdu syntax and vocabulary reflect a three tiered system of politeness called ādāb. Due to its emphasis on politeness and propriety, Urdu has always been considered an elevated, somewhat aristocratic, language in South Asia. It continues to conjure a subtle, polished affect in South Asian linguistic and literary sensibilities and thus continues to be preferred for song-writing and poetry, even by non-native speakers.

Any verb can be conjugated as per three or four different tiers of politeness. For example, the verb to speak in Urdu is bolnā (بولنا) and the verb to sit is baiṭhnā (بیٹھنا). The imperatives "speak!" and "sit!" can thus be conjugated five different ways, each marking subtle variation in politeness and propriety. These permutations exclude a host of auxiliary verbs and expressions that can be added to these verbs to add even greater degree of subtle variation. For extremely polite, formal or ceremonial situations, nearly all commonly used verbs have equivalent Persian/Arabic synonyms (last row below).

| Disparaging/Extremely casual | [tū] bol! | !تُو] بول] | [tū] baiṭh! | !تُو] بیٹھ] |

| Casual and intimate | [tum] bolo. | تُم] بولو۔] | [tum] baiṭho. | تُم] بیٹھو۔] |

| Polite and intimate[note 2] | [āp] bolo. | آپ] بولو۔] | [āp] baiṭho. | آپ] بیٹھو۔] |

| Formal yet intimate | [āp] boleṉ. | آپ] بولیں۔] | [āp] baiṭheṉ. | آپ] بیٹھیں۔] |

| Polite and formal | [āp] boli'e. | آپ] بولئے۔] | [āp] baiṭhi'e. | آپ] بیٹھئے۔] |

| Ceremonial / Extremely formal | [āp] farmā'iye. | آپ] فرمائیے۔] | [āp] tas̱ẖrīf rakhi'e. | [آپ] تشریف رکھئے۔ |

Similarly, nouns are also marked for politeness and formality. For example, us kī wālidah, "his mother" is a politer way of saying us kī ammī. Us kī wālidah-yi muḥtarmah is an even more polite reference, whereas saying us kī māṉ would be construed as derogatory. None of these forms are slang or shortenings, and all are encountered in writing.

Expressions are also marked for politeness. For example, the expression "no" could be nah, nahīṉ, nahīṉ jī or jī nahīṉ in order of politeness. Similarly, "yes" can be hāṉ, jī, hāṉ jī or jī hāṉ in order of politeness.

Non-secular feature of Urdu in Pakistan

In the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, use of certain Urdu words is reserved for Muslims only. Shaheed (شہید) is essentially meant to be used for Muslim martyrs and marḥūm (مرحوم) "late" (literally "in position of mercy") is only used before Muslim names. In contrast, the word for "late" used with a non-Muslim is ānjahānī (آنجہانی), a Persian coinage that means the deceased person belongs to the other world. If someone refers to a deceased Muslim as ānjahānī, that person is likely to be rebuked. [citation needed]

There are no such taboos in secular India. Shaheed (شہید) is used to refer to all honourable martyrs regardless of religion or cause.[50][51] Similarly, marḥūm is used freely in the Urdu press to refer to any deceased person. The neologism ānjahānī has no communal or religious connotations.

Writing system

Urdu script

Urdu is written right-to left in an extension of the Persian alphabet, which is itself an extension of the Arabic alphabet. Urdu is associated with the Nastaʿlīq style of Persian calligraphy, whereas Arabic is generally written in the Naskh or Ruq'ah styles. Nasta’liq is notoriously difficult to typeset, so Urdu newspapers were hand-written by masters of calligraphy, known as katib or khush-navees, until the late 1980s.[citation needed] One handwritten Urdu newspaper, The Musalman, is still published daily in Chennai.[52]

Kaithi script

Urdu was also written in the Kaithi script. A highly Persianized and technical form of Urdu was the lingua franca of the law courts of the British administration in Bengal, Bihar, and the North-West Provinces & Oudh. Until the late 19th century, all proceedings and court transactions in this register of Urdu were written officially in the Persian script. In 1880, Sir Ashley Eden, the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal abolished the use of the Persian alphabet in the law courts of Bengal and Bihar and ordered the exclusive use of Kaithi, a popular script used for both Urdu and Hindi.[53] Kaithi's association with Urdu and Hindi was ultimately eliminated by the political contest between these languages and their scripts, in which the Persian script was definitively linked to Urdu.

Devanagari script

More recently in India, Urdu speakers have adopted Devanagari for publishing Urdu periodicals and have innovated new strategies to mark Urdū in Devanagari as distinct from Hindi in Devanagari. Such publishers have introduced new orthographic features into Devanagari for the purpose of representing the Perso-Arabic etymology of Urdu words. One example is the use of अ (Devanagari a) with vowel signs to mimic contexts of ع (‘ain), in violation of Hindi orthographic rules. For Urdu publishers, the use of Devanagari gives them a greater audience, whereas the orthographic changes help them preserve a distinct identity of Urdu.[54]

Roman script

Urdu is occasionally written in the Roman script. Roman Urdu has been used since the days of the British Raj, partly as a result of the availability and low cost of Roman movable type for printing presses. The use of Roman Urdu was common in contexts such as product labels. Today it is regaining popularity among users of text-messaging and Internet services and is developing its own style and conventions. Habib R. Sulemani says,

"The younger generation of Urdu-speaking people around the world, especially Pakistan, are using Romanised Urdu on the Internet and it has become essential for them, because they use the Internet and English is its language. Typically, in that sense, a person from Islamabad in Pakistan may chat with another in Delhi in India on the Internet only in Roman Urdū. They both speak the same language but would have different scripts. Moreover, the younger generation of those who are from the English medium schools or settled in the west, can speak Urdu but can’t write it in the traditional Arabic script and thus Roman Urdu is a blessing for such a population."[55]

Roman Urdu holds significance among the Christians of Pakistan and North India. Urdū was the dominant native language among Christians of Karachi and Lahore in present-day Pakistan and Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh Rajasthan in India, during the early part of the 19th and 20th century, and is still used by Christians in these places. Pakistani and Indian Christians often used the Roman script for writing Urdū. Thus Roman Urdū was a common way of writing among Pakistani and Indian Christians in these areas up to the 1960s. The Bible Society of India publishes Roman Urdū Bibles that enjoyed sale late into the 1960s (though they are still published today). Church songbooks are also common in Roman Urdū. However, the usage of Roman Urdū is declining with the wider use of Hindi and English in these states.

Uddin and Begum Urdu-Hindustani romanization

Uddin and Begum Urdu-Hindustani Romanization is another system for Hindustani. It was proposed by Syed Fasih Uddin (late) and Quader Unissa Begum (late). As such is adopted by The First International Urdu Conference (Chicago) 1992, as "The Modern International Standard Letters of Alphabet for URDU-(HINDUSTANI) - The INDIAN Language script for the purposes of hand written communication, dictionary references, published material and Computerized Linguistic Communications (CLC)".

There are significant advantages to this transcription system:

- It provides a standard that is based on the original works undertaken at the Fort William College, Calcutta, India (established 1800), under John Borthwick Gilchrist (1789–1841), which has become the de facto standard for Hindustani during the late 1800.

- There is a one-to-one representation for each of the original Urdu-Hindustani characters.

- Vowel sounds are written rather than being assumed as they are in the Urdu alphabet.

- Unlike Gilchrist’s alphabet, which used many special non-ASCII characters, the proposed alphabet only utilizes ASCII.

- Because it is ASCII based, more resources and tools are available.

- Liberate Urdu–Hindustani language to be written and communicated utilizing all of the available standards and free us from Unicode conversion drudgery.

- Urdu–Hindustani with this character set fully utilizes paper and electronic print media.

Differences with Persian alphabet

The Persian alphabet has been extended for Urdu with additional letters ٹ ,ڈ ,ڑ (ṫ, ḋ, ṙ). In order to make the language suitable for the people of South Asia (mainly Pakistan & North India), two letters ه (h) and ی (y) were split into two letters each, to add dimensions in use. ه (h) is used independently, as any other letter, in words such as ہم (ham—we) and باہم (bāham—mutual). As an extended use, a variant of ه (h), ھ (ḣ) is used to denote uniquely defined phonetics of South Asian origin: here it is referred to as dō-čašmī hē (two-eyed h). Examples of such words are دهڑکن (dḣaṙkan—heartbeat) and بھارت (Bḣārat—India). Similarly, ی is used in two vowel forms: Čōṫī yē (ی—small y) and Baṙī yē (ے—big y). "Small y" denotes the vowel sound similar to "ea" in the English word "heat", as in the word ساتھی (sātḣī—companion) and is also used for the Urdu semi-vowel "y", as in word یار (yār—friend). "Big y" gives the sound similar to "a" in the word "late" (full vowel sound—not like a diphthong), as in the word کے (kē—of). However, in the written form, both "big y" and "small y" are the same when the vowel falls in the middle of a word and the letters need to be joined according to the rules of Urdu grammar. "Big y" is also used for the sound "a" as in the English word "apple", as in the word مے (mẹ̱—wine). Similarly the letter و is used to denote the vowel sound "oo" as in the word "food", as in لوٹ (lūṫ—loot); "o" similar to the sound in the word "vote", as in دو (dō—two), and is also used as a consonant "w" similar to that in the word "war", as in وظیفہ (waẓīfah—stipend). It is also used to represent the "au" sound as in the word "caught", as in کون (kọ̱—who). و is silent in many words of Persian origin such as خواب (dream) and خواہش (desire). It has a diminutive sound similar to "ou" in "would" and "could", as in the words خود (self) and خوش (happy). The vowel/accent marks (اعراب) mainly support the core Arabic vowels. Non-Arabic vowels such as -o- in mor مور- (peacock) and the -e- as in Estonia (ایسٹونیا) are referred as مجہول (alien/ignorant phonetics) and hence are not supported by the vowel/accent marks (اعراب). A description of these vowel marks and the word formation in Urdu can be found at the ukindia.com website.[56]

Encoding Urdu in Unicode

Like other writing systems derived from the Arabic script, Urdu uses the 0600–06FF Unicode range.[57] Certain glyphs in this range appear visually similar (or identical when presented using particular fonts) even though the underlying encoding is different. This presents problems for information storage and retrieval. For example, the University of Chicago's electronic copy of John Shakespear's "A Dictionary, Hindustani, and English"[58] includes the word 'بهارت' (India). Searching for the string "بھارت" returns no results, whereas querying with the (identical-looking in many fonts) string "بهارت" returns the correct entry.[59] This is because the medial form of the Urdu letter do chashmi he (U+06BE)—used to form aspirate digraphs in Urdu—is visually identical in its medial form to the Arabic letter hāʾ (U+0647; phonetic value /h/). In Urdu, the /h/ phoneme is represented by the character U+06C1, called gol he (round he), or chhoti he (small he).

| Characters in Urdu | Characters in Arabic |

|---|---|

| ہ (U+06C1), ھ (U+06BE) | ه (U+0647) |

| ی (U+06CC) | ى (U+0649), ي (U+064A) |

| ک (U+06A9) | ك (U+0643) |

In 2003, the Center for Research in Urdu Language Processing (CRULP)[60]—a research organization affiliated with Pakistan's National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences—produced a proposal for mapping from the 1-byte UZT encoding of Urdu characters to the Unicode standard.[61] This proposal suggests a preferred Unicode glyph for each character in the Urdu alphabet.

Sample text

The following is a sample text in Urdu, of the Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (by the United Nations):

Urdu text

- دفعہ ۱: تمام انسان آزاد اور حقوق و عزت کے اعتبار سے برابر پیدا ہوئے ہیں۔ انہیں ضمیر اور عقل ودیعت ہوئی ہے۔ اس لئے انہیں ایک دوسرے کے ساتھ بھائی چارے کا سلوک کرنا چاہئے۔

Transliteration (ALA-LC)

- Dafʿah 1: Tamām insān āzād aur ḥuqūq o ʿizzat ke iʿtibār se barābar paidā hūʾe haiṉ. Unheṉ ẓamīr aur ʿaql wadīʿat hūʾī hai. Is liʾe unheṉ ek dūsre ke sāth bhāʾī cāre kā sulūk karnā cāhiʾe.

IPA transcription

- d̪əfɑː eːk: t̪əmɑːm ɪnsɑːn ɑːzɑːd̪ ɔːr hʊquːq oː ɪzzət̪ keː et̪ɪbɑːr seː bərɑːbər pɛːd̪ɑː ɦuːeː ɦɛ̃ː. ʊnɦẽː zəmiːr ɔːr əql ʋəd̪iːət̪ huːiː hɛː. ɪs lieː ʊnɦẽː eːk d̪uːsreː keː sɑːt̪ʰ bʱaːiː t͡ʃɑːreː kɑː sʊluːk kərnɑː t͡ʃɑːɦieː.

Gloss (word-for-word)

- Article 1: All humans free[,] and rights and dignity *('s) consideration from equal born are. Them to conscience and intellect endowed is. This for, they one another *('s) with brotherhood *('s) treatment do should.

Translation (grammatical)

- Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience. Therefore, they should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Note: *('s) represents a possessive case that, when written, is preceded by the possessor and followed by the possessed, unlike the English "of".

Literature

Urdu has become a literary language only in recent centuries, as Persian was formerly the idiom of choice for the Muslim courts of North India. However, despite its relatively late development, Urdu literature boasts of some world-recognised artists and a considerable corpus.

Prose

Urdu afsana is a kind of Urdu prose in which much experiments have been done by the short story writers from Munshi Prem Chand to Naeem Baig.

Religious

Urdu holds the largest collection of works on Islamic literature and Sharia. These include translations and interpretation of the Qur'an as well as commentary on Hadith, Fiqh, history, spirituality, Sufism and metaphysics. A great number of classical texts from Arabic and Persian have also been translated into Urdu. Relatively inexpensive publishing, combined with the use of Urdu as a lingua franca among Muslims of South Asia, has meant that Islam-related works in Urdu far outnumber such works in any other South Asian language. Popular Islamic books are also written in Urdu.

It is interesting to note that a treatise on Astrology was penned in Urdu by Pandit Roop Chand Joshi in the eighteenth century. The book, known as Lal Kitab, is widely popular in North India among astrologers and was written at a time when Urdu was very much spoken in the Brahmin families of that region.

Literary

Secular prose includes all categories of widely known fiction and non-fiction work, separable into genres. The dāstān, or tale, a traditional story that may have many characters and complex plotting. This has now fallen into disuse.

The afsāna or short story is probably the best-known genre of Urdu fiction. The best-known afsāna writers, or afsāna nigār, in Urdu are Munshi Premchand, Saadat Hasan Manto, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Krishan Chander, Qurratulain Hyder (Qurat-ul-Ain Haider), Ismat Chughtai, Ghulam Abbas, and Ahmad Nadeem Qasimi. Towards the end of last century Paigham Afaqui's novel Makaan appeared with a reviving force for Urdu novel resulting into writing of novels getting a boost in Urdu literature and a number of writers like Ghazanfer, Abdus Samad, Sarwat Khan and Musharraf Alam Zauqi have taken the move forward. Munshi Premchand, became known as a pioneer in the afsāna, though some contend that his were not technically the first as Sir Ross Masood had already written many short stories in Urdu. Novels form a genre of their own, in the tradition of the English novel. Other genres include saférnāma (travel story), mazmoon (essay), sarguzisht (account/narrative), inshaeya (satirical essay), murasela (editorial), and khud navvisht (autobiography).

Poetry

Urdu has been one of the premier languages of poetry in South Asia for two centuries, and has developed a rich tradition in a variety of poetic genres. The Ghazal in Urdu represents the most popular form of subjective music and poetry, whereas the Nazm exemplifies the objective kind, often reserved for narrative, descriptive, didactic or satirical purposes. Under the broad head of the Nazm we may also include the classical forms of poems known by specific names such as Masnavi (a long narrative poem in rhyming couplets on any theme: romantic, religious, or didactic), Marsia (an elegy traditionally meant to commemorate the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of Muhammad, and his comrades of the Karbala fame), or Qasida (a panegyric written in praise of a king or a nobleman), for all these poems have a single presiding subject, logically developed and concluded. {However, these poetic species have an old world aura about their subject and style, and are different from the modern Nazm, supposed to have come into vogue in the later part of the nineteenth century. Probably the most widely recited, and memorised genre of contemporary Urdu poetry is nāt—panegyric poetry written in praise of Muhammad. Nāt can be of any formal category, but is most commonly in the ghazal form. The language used in Urdu nāt ranges from the intensely colloquial to a highly Persified formal language. The great early 20th century scholar Ala Hazrat, Ahmed Raza Khan Barelvi, who wrote many of the most well known nāts in Urdu (the collection of his poetic work is Hadaiq-e-Baqhshish), epitomised this range in a ghazal of nine stanzas (bayt) in which every stanza contains half a line each of Arabic, Persian, formal Urdu, and colloquial Hindi.

Another important genre of Urdu prose are the poems commemorating the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali at the Battle of Karbala, called noha (نوحہ) and marsia. Anees and Dabeer are famous in this regard.

Terminology

[As̱ẖʿār] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: urdu (help) (اشعار, verse, couplets): It consists of two hemistiches (lines) called [Miṣraʿ] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: urdu (help) (مصرع); first hemistich (line) is called مصرعِ اولٰى ([Miṣraʿ-i ūlá] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: urdu (help)) and the second is called (مصرعِ ثانی) ([Miṣraʿ-i s̱ānī] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: urdu (help)). Each verse embodies a single thought or subject (singular) شِعر [[Sher (poem)|[s̱ẖiʿr] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: urdu (help)]].

In the Urdu poetic tradition, most poets use a pen name called the [taḵẖalluṣ] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: urdu (help). This can be either a part of a poet's given name or something else adopted as an identity. The traditional convention in identifying Urdu poets is to mention the [taḵẖalluṣ] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: urdu (help) at the end of the name. Thus Ghalib, whose official name and title was Mirza Asadullah Beg Khan, is referred to formally as Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, or in common parlance as just Mirza Ghalib. Because the [taḵẖalluṣ] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: urdu (help) can be a part of their actual name, some poets end up having that part of their name repeated, such as Faiz Ahmad Faiz.

The word [taḵẖalluṣ] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: urdu (help) is derived from Arabic, meaning "ending". This is because in the ghazal form, the poet would usually incorporate his or her pen name into the final couplet ([maqt̤aʿ] Error: {{Transliteration}}: unrecognized language / script code: urdu (help)) of each poem as a type of "signature".

Urdu poetry example

This is Ghalib's famous couplet in which he compares himself to his great predecessor, the master poet Mir:[62]

ریختہ کے تمہی استاد نہیں ہو غاؔلب |

؎

| ||

کہتے ہیں اگلے زمانہ میں کوئی میرؔ بهی تها |

Transliteration

- Reḵẖtah ke tumhī ustād nahīṉ ho G̱ẖālib

- Kahte haiṉ agle zamānih meṉ ko'ī Mīr bhī thā

Translation

- You are not the only master of Rekhta,[note 3] Ghalib

- (They) say that in the past there also was someone (named) Mir.

Phrases

| English | Urdu | Transliteration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Hello) Peace be upon you. | السلامُ علیکم۔ | as-Salāmu ʿalaikum. | lit. "Peace be upon you." (from Arabic). Often shortened to 'Salām'. |

| (Reply to Salam) Peace be upon you, too. | وعلیکم السلام۔ | Wa ʿalaikum as-salām. | lit. "And upon you, peace." Response to assalāmu alaikum. |

| Hello. | آداب (عرض ہے)۔ | ādāb (arẓ hai). | lit. "Regards (are expressed).", a very formal secular greeting. |

| Goodbye. | خدا حافظ، اللّٰہ حافظ۔ | Khuda Hāfiz, Allah Hāfiz. | lit. "May God be your Guardian". "Khuda" from Persian for "God", "Allah" from Arabic for "God". |

| Yes. | ہاں۔ | hān. | casual. |

| Yes | جی۔ | jī. | formal. |

| Yes. | جی ہاں۔ | jī hāⁿ. | confident formal. |

| No. | نَہ۔ | nā. | rare. |

| No. | نَہیں | nahīⁿ | informal. |

| No. | نَہیں، جی نَہیں۔ | nahīⁿ, jī nahīⁿ. | casual; jī nahīⁿ is formal. |

| Please | آپ کی) مَہَربانی۔) | (āp kī) maharbānī. | lit. "(Your) kindness" Also used for "thank you". |

| Thank you. | شُکرِیَہ۔ | shukriyā. | from Arabic shukran. |

| Please, come in. | تَشریف لائیے۔ | tashrīf la'iyē. | lit. "(Please) bring your honour". |

| Please, have a seat. | تَشریف رکهِئے۔ | tashrīf rakhi'ē. | lit. "(Please) place your honour". |

| I am happy to meet you. | آپ سے مِل کر خوشی ہوئی۔ | āp sē mil kar khushī hū'ī. | lit. "(I) felt happiness (after) meeting you". |

| Do you speak English? | کیا آپ انگریزی بولتے/بولتی ہیں؟ | kyā āp angrēzī bōltē/boltī haiⁿ? | "bōltē" is for a male addressee, "bōltī" is for female. |

| I do not speak Urdu. | میں اردو نہیں بولتا/بولتی۔ | maiⁿ urdū nahīⁿ boltā/boltī. | boltā is for masculine speaker, boltī is for feminine. |

| My name is __ . | میرا نام ۔۔۔ ہے۔ | merā nām __ hai. | |

| Which way to Karachi? | کراچی کس طرف/ اور ہے؟ | Karachi kis taraf/ōr hai?[note 4] | lit. "Which direction is Karachi (in)?" |

| Where is Lucknow? | لکھنؤ کہاں ہے؟ | lakhnau kahāⁿ hai? | |

| Urdu is a good language. | اردو اچّهی زبان ہے۔ | urdū achhī zabān hai. |

Software

The Daily Jang was the first Urdu newspaper to be typeset digitally in Nasta’liq by computer. There are efforts underway to develop more sophisticated and user-friendly Urdu support on computers and the Internet. Nowadays, nearly all Urdu newspapers, magazines, journals, and periodicals are composed on computers via various Urdu software programmes, the most widespread of which is InPage Desktop Publishing package. Microsoft has included Urdu language support in all new versions of Windows and both Windows Vista and Microsoft Office 2007 are available in Urdu through Language Interface Pack[63] support. Most Linux Desktop distributions allow the easy installation of Urdu support and translations as well.[64] Apple implemented the Urdu language keyboard across Mobile devices in its iOS 8 update in September 2014.[65]

See also

- Hindi–Urdu controversy

- List of Urdu-language poets

- List of Urdu-language writers

- National Translation Mission (NTM)

- Persian and Urdu

- States of India by Urdu speakers

- Urdu in the United Kingdom

- Uddin and Begum Urdu-Hindustani Romanization

- Urdu Digest

- Urdu in Aurangabad

- Urdu Informatics

- Urdu keyboard

- Glossary of the British Raj

Notes

- ^ An example can be seen in the word "need" in Urdu. Urdu uses the Farsi version ضرورت rather than the original Arabic ضرورة. See: John T. Platts "A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English" (1884) Page 749. Urdu also use Farsi pronunciation - for instance rather than pronouncing ض as "ḍ" an emphatic consonant, the original sound in Arabic, Urdu uses the Farsi promonunction "z". See: John T. Platts "A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English" (1884) Page 748

- ^ The phrase category ‘[āp] bolo’, is associated with the Punjabi usage ‘tusī bolo’ and is not used in Urdu. It is considered grammatically incorrect, particularly in the Gangetic Plain, where the influence of Punjabi on Urdu is minimal.

- ^ Rekhta was the name for the Urdu language in Ghalib’s days.

- ^ اور is commonly used in Uttar Pradesh and certain parts of Punjab when speaking Urdu; it is not common in mainstream Pakistani media. It is synonymous with طرف. Reference A New-Hindustani Dictionary

References

- ^ "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Seventeenth edition, Urdu". Ethnologue. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

- ^ a b Hindustani (2005). Keith Brown (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- ^ Gaurav Takkar. "Short Term Programmes". punarbhava.in. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "Indo-Pakistani Sign Language", Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics

- ^ "National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language". Urducouncil.nic.in. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Brass, Paul R. (2005). Language, religion and politics in North India. Lincoln, NE: IUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-34394-2.

- ^ Rauf Parekh. "Literary Notes: Common misconceptions about Urdu". dawn.com. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "Two Languages or One?". hindiurduflagship.org. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ Hamari History, Hamari Boli

- ^ Dua, Hans R. (1992). Hindi-Urdu as a pluricentric language. In M. G. Clyne (Ed.), Pluricentric languages: Differing norms in different nations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-012855-1.

- ^ Salimuddin S et al. (2013). "Oxford Urdu-English Dictionary ". Pakistan: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-597994-7 (Introduction Chapter)

- ^ Kachru, Yamuna (2008), Braj Kachru; Yamuna Kachru; S. N. Sridhar (eds.), Hindi-Urdu-Hindustani, Language in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 82, ISBN 978-0-521-78653-9

- ^ Peter Austin (1 September 2008). One thousand languages: living, endangered, and lost. University of California Press. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-0-520-25560-9. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ InpaperMagazine. "Language: Urdu and the borrowed words". dawn.com. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ John R. Perry, "Lexical Areas and Semantic Fields of Arabic" in Éva Ágnes Csató, Eva Agnes Csato, Bo Isaksson, Carina Jahani, Linguistic convergence and areal diffusion: case studies from Iranian, Semitic and Turkic, Routledge, 2005. pg 97: "It is generally understood that the bulk of the Arabic vocabulary in the central, contiguous Iranian, Turkic and Indic languages was originally borrowed into literary Persian between the ninth and thirteenth centuries"

- ^ Faruqi, Shamsur Rahman (2003), Sheldon Pollock (ed.), A Long History of Urdu Literary Culture Part 1, Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions From South Asia, University of California Press, p. 806, ISBN 0-520-22821-9

- ^ a b c Rahman, Tariq (2001). From Hindi to Urdu: A Social and Political History (PDF). Oxford University Press. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-19-906313-0.

- ^ Rahman, Tariq (2000). "The Teaching of Urdu in British India" (PDF). The Annual of Urdu Studies. 15: 55.

- ^ "The Urdu Language". The Urdu Language. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Rahman, Tariq (2014), Pakistani English (PDF), Quaid-i-Azam University=Islamabad, p. 9

- ^ "Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues – 2001". Government of India. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- ^ Government of Pakistan: Population by Mother Tongue Pakistan Bureau of Statistics

- ^ "Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version". Ethnologue.org. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ "Ethnologue: Statistical Summaries". SIL. 1999. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ^ "The World's 10 most influential Languages". Language Today. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ e.g. Gumperz (1982:20)

- ^ Top Communications. "Holy Places — Ajmer". India Travelite. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ "Árabe y urdu aparecen entre las lenguas habituales de Catalunya, creando peligro de guetos". Europapress.es. 29 June 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Government of Pakistan: Population by Mother Tongue Pakistan Bureau of Statistics

- ^ In the lower courts in Pakistan, despite the proceedings taking place in Urdu, the documents are in English, whereas in the higher courts, i.e. the High Courts and the Supreme Court, both documents and proceedings are in English.

- ^ Zia, Khaver (1999), "A Survey of Standardisation in Urdu". 4th Symposium on Multilingual Information Processing, (MLIT-4), Yangon, Myanmar. CICC, Japan

- ^ Rahman, Tariq (2010). Language Policy, Identity and Religion (PDF). Islamabad: Quaid-i-Azam University. p. 59.

- ^ "Urdu in Bihar". Language in India. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- ^ http://jkgad.nic.in/statutory/Rules-Costitution-of-J&K.pdf

- ^ "Importance Of Urdu". GeoTauAisay.com. Retrieved 8 August 2010. [dead link]

- ^ "Bringing Order to Linguistic Diversity: Language Planning in the British Raj". Language in India. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ "A Brief Hindi — Urdu FAQ". sikmirza. Archived from the original on 2 December 2007. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ "Hindi/Urdu Language Instruction". University of California, Davis. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Ethnologue Report for Hindi". Ethnologue. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ "Urdu and its Contribution to Secular Values". South Asian Voice. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ The Annual of Urdu studies, number 11, 1996, “Some notes on Hindi and Urdu”, pp. 203–208.

- ^ Shakespear, John (1834), A dictionary, Hindustani and English (PDF), Black, Kingsbury, Parbury and Allen

- ^ Fallon, S. W. (1879), A new Hindustani-English dictionary, with illustrations from Hindustani literature and folk-lore, Banāras: Printed at the Medical Hall Press

- ^ "Urdu: Language of the Aam Aadmi". The Times of India. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "'Vishvas': A word that threatens Pakistan". The Express Tribune. 18 September 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "Kids have it right: boundaries of Urdu and Hindi are blurred". Firstpost. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ Colin P. Masica, The Indo-Aryan languages. Cambridge Language Surveys (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993). 466.

- ^ "About Urdu". Afroz Taj (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ "Kargil Shaheed Smriti Vatika ready to pay homage to Kargil martyrs". The Times of India. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "Kargil War Heroes". ikashmir.net. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ India: The Last Handwritten Newspaper in the World · Global Voices. Globalvoicesonline.org (2012-03-26). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ^ King, 1994.

- ^ Ahmad, R., 2006.

- ^ The News, Karachi, Pakistan: Roman Urdu by Habib R Sulemani

- ^ "Ukindia Learn Urdu Page". ukindia.com. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0600.pdf

- ^ "A dictionary, Hindustani and English". Dsal.uchicago.edu. 29 September 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "A dictionary, Hindustani and English". Dsal.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "Center for Research in Urdu Language Processing". Crulp.org. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ http://www.tremu.gov.pk/tremu1/workingroups/pdfpresentations/UZT%20UNICODE%20MAPPING.pdf

- ^ "Columbia University: Ghazal 36, Verse 11". Columbia.edu. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ ":مائِیکروسافٹ ڈاؤُن لوڈ مَرکَزWindows". Microsoft.com. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "ubuntu in urdu « Aasim's Web Corner". Aasims.wordpress.com. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "E-Urdu: How one man's plea for Nastaleeq was heard by Apple". The Express Tribune. 16 October 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

Further reading

- Henry Blochmann (1877). English and Urdu dictionary, romanized (8 ed.). CALCUTTA: Printed at the Baptist mission press for the Calcutta school-book society. p. 215. Retrieved 6 July 2011.the University of Michigan

- John Dowson (1908). A grammar of the Urdū or Hindūstānī language (3 ed.). LONDON: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., ltd. p. 264. Retrieved 6 July 2011.the University of Michigan

- John Dowson (1872). A grammar of the Urdū or Hindūstānī language. LONDON: Trübner & Co. p. 264. Retrieved 6 July 2011.Oxford University

- John Thompson Platts (1874). A grammar of the Hindūstānī or Urdū language. Vol. Volume 6423 of Harvard College Library preservation microfilm program. LONDON: W.H. Allen. p. 399. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)Oxford University - John Thompson Platts (1892). A grammar of the Hindūstānī or Urdū language. LONDON: W.H. Allen. p. 399. Retrieved 6 July 2011.the New York Public Library

- John Thompson Platts (1884). A dictionary of Urdū, classical Hindī, and English (reprint ed.). LONDON: H. Milford. p. 1259. Retrieved 6 July 2011.Oxford University

- Ahmad, Rizwan. 2006. "Voices people write: Examining Urdu in Devanagari"

- Alam, Muzaffar. 1998. "The Pursuit of Persian: Language in Mughal Politics." In Modern Asian Studies, vol. 32, no. 2. (May, 1998), pp. 317–349.

- Asher, R. E. (Ed.). 1994. The Encyclopedia of language and linguistics. Oxford: Pergamon Press. ISBN 0-08-035943-4.

- Azad, Muhammad Husain. 2001 [1907]. Aab-e hayat (Lahore: Naval Kishor Gais Printing Works) 1907 [in Urdu]; (Delhi: Oxford University Press) 2001. [In English translation]

- Azim, Anwar. 1975. Urdu a victim of cultural genocide. In Z. Imam (Ed.), Muslims in India (p. 259).

- Bhatia, Tej K. 1996. Colloquial Hindi: The Complete Course for Beginners. London, UK & New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11087-4 (Book), 0415110882 (Cassettes), 0415110890 (Book & Cassette Course)

- Bhatia, Tej K. and Koul Ashok. 2000. "Colloquial Urdu: The Complete Course for Beginners." London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13540-0 (Book); ISBN 0-415-13541-9 (cassette); ISBN 0-415-13542-7 (book and casseettes course)

- Chatterji, Suniti K. 1960. Indo-Aryan and Hindi (rev. 2nd ed.). Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay.

- Dua, Hans R. 1992. "Hindi-Urdu as a pluricentric language". In M. G. Clyne (Ed.), Pluricentric languages: Differing norms in different nations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-012855-1.

- Dua, Hans R. 1994a. Hindustani. In Asher, 1994; pp. 1554.

- Dua, Hans R. 1994b. Urdu. In Asher, 1994; pp. 4863–4864.

- Durrani, Attash, Dr. 2008. Pakistani Urdu.Islamabad: National Language Authority, Pakistan.

- Gumperz, J.J. (1982). "Discourse Strategies". Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hassan, Nazir and Omkar N. Koul 1980. Urdu Phonetic Reader. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages.

- Syed Maqsud Jamil (16 June 2006). "The Literary Heritage of Urdu". Daily Star.

- Kelkar, A. R. 1968. Studies in Hindi-Urdu: Introduction and word phonology. Poona: Deccan College.

- Khan, M. H. 1969. Urdu. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), Current trends in linguistics (Vol. 5). The Hague: Mouton.

- King, Christopher R. 1994. One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India. Bombay: Oxford University Press.

- Koul, Ashok K. 2008. Urdu Script and Vocabulary. Delhi: Indian Institute of Language Studies.

- Koul, Omkar N. 1994. Hindi Phonetic Reader. Delhi: Indian Institute of Language Studies.

- Koul, Omkar N. 2008. Modern Hindi Grammar. Springfield: Dunwoody Press.

- Narang, G. C. and D. A. Becker. 1971. Aspiration and nasalization in the generative phonology of Hindi-Urdu. Language, 47, 646–767.

- Ohala, M. 1972. Topics in Hindi-Urdu phonology. (PhD dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles).

- "A Desertful of Roses", a site about Ghalib's Urdu ghazals by Dr. Frances W. Pritchett, Professor of Modern Indic Languages at Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

- Phukan, S. 2000. The Rustic Beloved: Ecology of Hindi in a Persianate World, The Annual of Urdu Studies, vol 15, issue 5, pp. 1–30

- The Comparative study of Urdu and Khowar. Badshah Munir Bukhari National Language Authority Pakistan 2003.

- Rai, Amrit. 1984. A house divided: The origin and development of Hindi-Hindustani. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-561643-X.

- Snell, Rupert Teach yourself Hindi: A complete guide for beginners. Lincolnwood, IL: NTC

- Pimsleur, Dr. Paul, "Free Urdu Audio Lesson"

- The poisonous potency of script: Hindi and Urdu, ROBERT D. KING

External links

- Directory of Urdu websites.

- History of Urdu (Urdu site)