Billie Jean King

Billie Jean King | |

|---|---|

King in 2011 | |

| Born | Billie Jean Moffitt November 22, 1943 Long Beach, California, U.S. |

| Height | 5 ft 5 in (1.65 m) |

| Spouses | |

Tennis career | |

| Country (sports) | |

| Turned pro | 1968 |

| Retired | 1990 |

| Plays | Right-handed (one-handed backhand) |

| College | California State University, Los Angeles |

| Prize money | $1,966,487[1] |

| Int. Tennis HoF | 1987 (member page) |

| Official website | billiejeanking.com |

| Singles | |

| Career record | 695–155 (81.76%) |

| Career titles | 129 (67 during open era) |

| Highest ranking | No. 1 (1966, Lance Tingay) |

| Grand Slam singles results | |

| Australian Open | W (1968) |

| French Open | W (1972) |

| Wimbledon | W (1966, 1967, 1968, 1972, 1973, 1975) |

| US Open | W (1967, 1971, 1972, 1974) |

| Doubles | |

| Career record | 87–37 (as shown on WTA website)[1] |

| Highest ranking | No. 1 (1967) |

| Grand Slam doubles results | |

| Australian Open | F (1965, 1969) |

| French Open | W (1972) |

| Wimbledon | W (1961, 1962, 1965, 1967, 1968, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1979) |

| US Open | W (1964, 1967, 1974, 1978, 1980) |

| Other doubles tournaments | |

| Tour Finals | W (1974, 1976, 1978, 1980) |

| Mixed doubles | |

| Career titles | 11 |

| Grand Slam mixed doubles results | |

| Australian Open | W (1968) |

| French Open | W (1967, 1970) |

| Wimbledon | W (1967, 1971, 1973, 1974) |

| US Open | W (1967, 1971, 1973, 1976) |

| Team competitions | |

| Fed Cup | W (1963, 1966, 1967, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979) (as player) W (1976, 1996, 1999, 2000) (as captain) |

| Coaching career | |

Billie Jean King (née Moffitt; born November 22, 1943), also known as BJK, is an American former world No. 1 tennis player. King won 39 Grand Slam titles: 12 in singles, 16 in women's doubles, and 11 in mixed doubles. King was a member of the victorious United States team in seven Federation Cups and nine Wightman Cups. For three years, she was the U.S. captain in the Federation Cup.

King is an advocate of gender equality and has long been a pioneer for equality and social justice.[2] In 1973, at the age of 29, she famously won the "Battle of the Sexes" tennis match against the 55-year-old Bobby Riggs.[3] King was also the founder of the Women's Tennis Association and the Women's Sports Foundation. She was instrumental in persuading cigarette brand Virginia Slims to sponsor women's tennis in the 1970s and went on to serve on the board of their parent company Philip Morris in the 2000s.

Regarded by many as one of the greatest tennis players of all time,[4][5][6][7] King was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1987. The Fed Cup Award of Excellence was bestowed on her in 2010. In 1972, she was the joint winner, with John Wooden, of the Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year award and was one of the Time Persons of the Year in 1975. She has also received the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Sunday Times Sportswoman of the Year lifetime achievement award. She was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1990, and in 2006, the USTA National Tennis Center in New York City was renamed the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. In 2018, she won the BBC Sports Personality of the Year Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2020, the Federation Cup was renamed the Billie Jean King Cup in her honor. In 2022, she was awarded the French Legion of Honour, and in 2024, she received a Congressional Gold Medal. On October 7, 2024, King was named the Grand Marshal of the 2025 Rose Parade and Rose Bowl Game.

Early life

[edit]Billie Jean Moffitt was born in Long Beach, California, into a conservative Methodist family, the daughter of Betty (née Jerman), a housewife, and Bill Moffitt, a firefighter.[8][9] Her family was athletic; her mother excelled at swimming, and her father played basketball, baseball and ran track.[10] Her younger brother, Randy Moffitt, became a Major League Baseball pitcher, pitching for 12 years in the major leagues for the San Francisco Giants, Houston Astros, and Toronto Blue Jays.[11] She also excelled at baseball and softball as a child, playing shortstop at 10 years old on a team with girls 4–5 years older than she.[10] The team went on to win the Long Beach softball championship.[10]

She switched from softball to tennis at the age of 11,[12] because her parents suggested she should find a more 'ladylike' sport.[10] She saved her own money, $8 ($92.40 in 2024[13] terms), to buy her first racket.[10] She went with a school friend to take her first tennis lesson on the many free public courts in Long Beach, taking advantage of the free lessons offered by professional Clyde Walker, who worked for the City of Long Beach.[10] One of the city's tennis facilities has subsequently been named the Billie Jean Moffitt King Tennis Center.[14] As a kid playing in her first tennis tournaments, she was often hindered by her aggressive playing style.[10] Bob Martin, sportswriter for the Long Beach, Press-Telegram wrote about her success in a weekly tennis column.[citation needed] One of King's first conflicts with the tennis establishments and status-quo came in her youth, when she was forbidden from being in a group picture at a tournament because she was wearing tennis shorts (sewn by her mother) instead of the usual white tennis dress.[15]

King's family in Long Beach attended the Church of the Brethren, where the minister was former athlete and two-time Olympic pole-vaulting champion Bob Richards. One day, when King was 13 or 14, Richards asked her, "What are you going to do with your life?" She said: "Reverend, I'm going to be the best tennis player in the world."[16][17][18]

King attended Long Beach Polytechnic High School.[19] After graduating in 1961, she attended Los Angeles State College, now California State University, Los Angeles (Cal State LA).[12] She did not graduate, leaving school in 1964 to focus on tennis.[20] While attending Cal State, she met Larry King in a library in 1963.[10] The pair became engaged while still in school when Billie Jean was 20 and Larry 19 years old and married on September 17, 1965, in Long Beach.[21]

Career

[edit]

King's French Open win in 1972 made her only the fifth woman in tennis history to win the singles titles at all four Grand Slam events, a "career Grand Slam".[a] She also won a career Grand Slam in mixed doubles. In women's doubles, only the Australian Open eluded her.

King won a record 20 career titles at Wimbledon – six in singles, 10 in women's doubles, and four in mixed doubles.[b]

King played 51 Grand Slam singles events from 1959 through 1983, reaching at least the semi-finals in 27 and at least the quarterfinals in 40 of her attempts. King was the runner-up in six Grand Slam singles events. An indicator of her mental toughness in Grand Slam singles tournaments was her 11–2 career record in deuce third sets, i.e., third sets that were tied 5–5 before being resolved.[citation needed]

King won 129 singles titles,[22] 78 of which were WTA titles, and her career prize money totaled US$1,966,487.[23]

In Federation Cup finals, she was on the winning United States team seven times, in 1963, 1966, 1967, and 1976 through 1979. Her career win–loss record was 52–4.[c] She won the last 30 matches she played,[d] including 15 straight wins in both singles and doubles.[24] In Wightman Cup competition, her career win–loss record was 22–4,[e] winning her last nine matches (six in singles and three in doubles). The United States won the cup in ten of the 11 years in which she participated. In singles, King was 6–1 against Ann Haydon-Jones, 4–0 against Virginia Wade, and 1–1 against Christine Truman Janes.[25]

The early years: 1959–1963

[edit]As Billie Jean King began competing in 1959, she began working with new coaches including Frank Brennan[10] and Alice Marble, who had won 18 Grand Slam titles as a player herself.[26] She made her Grand Slam debut at the 1959 U.S. Championships when she was 15.[27] She lost in the first round.[28] She began playing at local, regional, and international tennis championships.[29]: 164 Sports Illustrated already claimed her as "one of the most promising youngsters on the West Coast."[30] She won her first tournament the next year in Philadelphia at the 1960 Philadelphia and District Grass Court Championships.[27][31] At her second attempt at the U.S. Championships, King made it to the third round, losing to Bernice Carr Vukovich of South Africa.[citation needed] Also in 1960, she reached the final of the National Girls' 18 and Under Championships, losing to Karen Hantze Susman.[10] Her national tennis ranking improved from number 19 in 1959 to number 4 in 1960.[32]: 23 Despite the success, Marble terminated her professional relationship with King, for reasons stemming from King's ambition.[32]: 23

King first gained international recognition in 1961 when the Long Beach Tennis Patrons, the Century Club, and Harold Guiver raised $2,000 to send her to Wimbledon.[33] There, she won the women's doubles title in her first attempt while partnering Karen Hantze.[8] King was 17 and Hantze was 18, making them the youngest team to win the Wimbledon Doubles Title.[10] King had less luck that year in the 1961 Wimbledon women's singles, losing to fifth-seeded Yola Ramírez in a two-day match on Centre Court.[34] Despite these performances. she could not get a sports scholarship when later that year she attended Los Angeles State (now California State).[35] For the 1962 singles tournament at Wimbledon, King upset Margaret Court, the World No. 1 and top seed, in a second round match by attacking Court's forehand[36][37] This was the first time in Wimbledon history that the women's top seed had lost her first match.[38] That same year, King and Hantze repeated their doubles victory at Wimbledon.[32]: 24 In 1963, King again faced Margaret Court at Wimbledon.[32]: 24 This time they met in the final, and Court prevailed.[32]: 24

1964

[edit]In 1964, King won four relatively minor titles[citation needed] but lost to Margaret Court in the Wimbledon semi-finals.[39] She defeated Ann Haydon-Jones at both the Wightman Cup and Fed Cup but lost to Court in the final of the Federation Cup. At the U.S. Championships, fifth-seeded Nancy Richey upset third-seeded King in the quarterfinals. Late in the year, King decided to make a full-time commitment to tennis. While a history major at Los Angeles State College, King made the decision to play full-time when businessman Robert Mitchell offered to pay her way to Australia so that she could train under the great Australian coach Mervyn Rose.[40] While in Australia, King played three tournaments that year and lost in the quarterfinals of the Queensland Grass Court Championships, the final of the New South Wales Championships (to Court), and the third round of the Victorian Championships.

1965

[edit]In early 1965, King continued her three-month tour of Australia. She lost in the final of the South Australian Championships and the first round of the Western Australia Championships. At the Fed Cup in Melbourne, she defeated Ann Haydon-Jones to help the United States defeat the United Kingdom in the second round. However, Margaret Court again defeated her in the final. At the Australian Championships two weeks later, she lost to Court in the semi-finals in two sets. At Wimbledon, she again lost in the semi-finals, this time in three sets to Maria Bueno.[10] Her last tournament of the year was the U.S. Championships, where she defeated Jones in the quarterfinals and Bueno in the semi-finals. In the final, King led 5–3 in both sets, was two points from winning the first set, and had two set points in the second set[41] before losing to Court in straight sets. She said that losing while being so close to winning was devastating, but the match proved to her that she was "good enough to be the best in the world. I'm going to win Wimbledon next year."[42] She won six tournaments during the year. For the first time in 81 years, the annual convention of the United States Lawn Tennis Association overruled its ranking committee's recommendation to award her the sole U.S. No. 1 position and voted 59,810 to 40,966 to rank Nancy Richey Gunter and King as co-U.S. No. 1.[43]

Prime competitive years: 1966–1975

[edit]Overview

[edit]Six of King's Grand Slam singles titles were at Wimbledon, four were at the U.S. Championships/Open, one was at the French Open, and one was at the Australian Championships. King reached the final of a Grand Slam singles tournament in 16 out of 25 attempts and had a 12–4 win–loss record in those finals. In the nine tournaments that she failed to reach the final, she was a losing semi-finalist twice and a losing quarter finalist five times. From 1971 through 1975, she won seven of the ten Grand Slam singles tournaments she played. She won the last seven Grand Slam singles finals she contested, six of them in straight sets and four of them against Evonne Goolagong. All but one of her Grand Slam singles titles were on grass.

King's Grand Slam record from 1966 through 1975 was comparable to that of Margaret Court, her primary rival during these years. One or both of these women played 35 of the 40 Grand Slam singles tournaments held during this period, and together they won 24 of them. During this period, Court won 31 of her career 64 Grand Slam titles, including 12 of her 24 Grand Slam singles titles, 11 of her 19 Grand Slam women's doubles titles, and eight of her 21 Grand Slam mixed doubles titles. Court reached the final of a Grand Slam singles tournament in 14 out of 25 attempts and had a 12–2 win–loss record in those finals. Court won seven of the 12 Grand Slam finals she played against King during these years, including 2–1 in singles finals, 4–1 in women's doubles finals, and 1–3 in mixed doubles finals.

King was the year-ending World No. 1 in six of the ten years from 1966 through 1975. She was the year-ending World No. 2 in three of those years and the World No. 3 in the other year.

King won 97 of her career 129 singles titles during this period and was the runner-up in 36 other tournaments.

1966

[edit]

In 1966, King defeated Dorothy "Dodo" Cheney (then 49 years old) for the first time in five career matches, winning their semi-final at the Southern California Championships 6–0, 6–3. King also ended her nine-match losing streak to Margaret Court by defeating her in the final of the South African Tennis Championships. She also won the women's singles in the Ojai Tennis Tournament.[44] At the Wightman Cup just before Wimbledon, King defeated Virginia Wade and Ann Haydon-Jones. After thirteen unsuccessful attempts to win a Grand Slam singles title from 1959 through 1965, King at the age of 22 finally won the first of her six singles titles at Wimbledon and the first of twelve Grand Slam singles titles overall, defeating Court in the semi-finals 6–3, 6–3 and Maria Bueno in the final. King credited her semi-final victory to her forehand down the line, a new shot in her repertoire.[42] She also said that the strategy for playing Court is, "Simple. Just chip the ball back at her feet."[45] At the U.S. Championships, an ill King was upset by Kerry Melville in the second round.[46]

1967

[edit]King successfully defended her title at the South African Tennis Championships in 1967, defeating Maria Bueno in the final. She played the French Championships for the first time in her career,[47] falling in the quarterfinals to Annette Van Zyl of South Africa. At the Federation Cup one week later in West Germany on clay, King won all four of her matches, including victories over DuPlooy, Ann Haydon-Jones, and Helga Niessen. King then successfully switched surfaces and won her second consecutive Wimbledon singles title, defeating Virginia Wade in the quarterfinals 7–5, 6–2 and Jones. At the Wightman Cup, King again defeated Wade and Jones. King won her second Grand Slam singles title of the year when she won the U.S. Championships for the first time and without losing a set, defeating Wade, Van Zyl, Françoise Dürr, and Jones in consecutive matches. Jones pulled her left hamstring muscle early in the final and saved four match points in the second set before King prevailed.[48] King won the singles, women's doubles, and mixed doubles titles at both Wimbledon and the U.S. Championships, the first woman to do that since Alice Marble in 1939.[49] King then returned to the Australian summer tour in December for the first time since 1965, playing seven events there and Judy Tegart in six of those events (winning four of their matches). King lost in the quarterfinals of the New South Wales Championships in Sydney to Tegart after King injured her left knee in the second game of the third set of that match.[50] However, King won the Victorian Championships in Melbourne the following week, defeating Dalton, Reid, and Lesley Turner in the last three rounds. At a team event in Adelaide, King won all three of her singles and doubles matches to help the U.S. defeat Australia 5–1. To finish the year, King lost to Tegart in the final of the South Australian Championships in Adelaide.

1968

[edit]In early 1968, King won three consecutive tournaments to end her Australian tour. In Perth, King won the Western Australia Championships, defeating Margaret Court in the final. In Hobart, King won the Tasmanian Championships by defeating Judy Tegart-Dalton in the final. King then won the Australian Championships for the first time, defeating Dalton in the semi-finals and Court in the final. King continued to win tournaments upon her return to the United States, winning three indoor tournaments before Nancy Richey Gunter defeated King in the semi-finals of the Madison Square Garden Challenge Trophy amateur tournament in New York City before 10,233 spectators.[51] The match started with Gunter taking a 4–2 lead in the first set, before King won 9 of the next 10 games. King served for the match at 5–1 and had a match point at 5–3 in the second set; however, she lost the final 12 games and the match 4–6, 7–5, 6–0.[52] King then won three consecutive tournaments in Europe before losing to Ann Haydon-Jones in the final of a professional tournament at Madison Square Garden. Playing the French Open for only the second time in her career and attempting to win four consecutive Grand Slam singles titles (a "non-calendar year Grand Slam"), King defeated Maria Bueno in a quarterfinal before losing to Gunter in a semi-final 2–6, 6–3, 6–4. King rebounded to win her third consecutive Wimbledon singles title, defeating Jones in the semi-finals and Dalton in the final. At the US Open, King defeated Bueno in a semi-final before being upset in the final by Virginia Wade. On September 24, she had surgery to repair cartilage in her left knee[53] and did not play in tournaments the remainder of the year. King said that it took eight months (May 1969) for her knee to recover completely from the surgery.[54] In 1977, King said that her doctors predicted in 1968 that her left knee would allow her to play competitive tennis for only two more years.[55]

1969

[edit]King participated in the 1969 Australian summer tour for the second consecutive year. Unlike the previous year, King did not win a tournament. She lost in the quarterfinals of the Tasmanian Championships and the semi-finals of the New South Wales Championships. At the Australian Open, King defeated 17-year-old Evonne Goolagong in the second round 6–3, 6–1 and Ann Haydon-Jones in a three-set semi-final before losing to Margaret Court in a straight-sets final. The following week, King lost in the semi-finals of the New Zealand Championships. Upon her return to the United States, King won the Pacific Coast Pro and the Los Angeles Pro. King then won two tournaments in South Africa, including the South African Open. During the European summer clay court season, King lost in the quarterfinals of both the Italian Open and the French Open. On grass at the Wills Open in Bristol, United Kingdom, King defeated Virginia Wade in the semi-finals (6–8, 11–9, 6–2) before losing to Court. At Wimbledon, King lost only 13 points while defeating Rosemary Casals in the semi-finals 6–1, 6–0;[56] however, Jones upset King in the final and prevented King from winning her fourth consecutive singles title there. The week after, King again defeated Wade to win the Irish Open for the second time in her career. In the final Grand Slam tournament of the year, King lost in the quarterfinals of the US Open to Nancy Richey Gunter 6–4, 8–6. This was the first year since 1965 that King did not win at least one Grand Slam singles title. King finished the year with titles at the Pacific Southwest Open in Los Angeles, the Stockholm Indoors, and the Midland (Texas) Pro. She said during the Pacific Southwest Open, "It has been a bad year for me. My left knee has been OK, but I have been bothered by a severe tennis elbow for seven months. I expect to have a real big year in 1970, though, because I really have the motivation now. I feel like a kid again."[57]

1970

[edit]

In 1970, Margaret Court won all four Grand Slam singles tournaments and was clearly the World No. 1. King lost to Court three times in the first four months of the year, in Philadelphia, Dallas, and Johannesburg (at the South African Open). Court, however, was not totally dominant during this period as King defeated her in Sydney and Durban, South Africa. Where Court dominated was at the Grand Slam tournaments. King did not play the Australian Open. King had leg cramps and lost to Helga Niessen Masthoff of West Germany in the quarterfinals of the French Open 2–6, 8–6, 6–1.[58] At Wimbledon, Court needed seven match points[59] to defeat King in the final 14–12, 11–9 in one of the greatest women's finals in the history of the tournament.[60] On July 22,[61] King had right knee surgery, which forced her to miss the US Open. King returned to the tour in September, where she had a first round loss at the Virginia Slims Invitational in Houston and a semi-final loss at the Pacific Coast Championships in Berkeley, California. To close out the year, King in November won the Virginia Slims Invitational in Richmond, Virginia and the Embassy Indoor Tennis Championships in London. During the European clay court season, King warmed-up for the French Open by playing in Monte Carlo (losing in the semi-finals), winning the Italian Open (saving three match points against Virginia Wade in the semi-finals),[62] playing in Bournemouth (losing to Wade in the quarterfinals), and playing in Berlin (losing to Masthoff in the semi-finals). The Italian Open victory was the first important clay court title of King's career. Along the way, she defeated Masthoff in a three-set quarterfinal and Wade in a three-set semi-final, saving two match points at 4–5 in the second set. The twelfth game of that set (with King leading 6–5) had 21 deuces and lasted 22 minutes,[63] with Wade saving seven set points and holding sixteen game points before King won. In Wightman Cup competition two weeks before Wimbledon but played at the All England Club, King defeated both Wade and Ann Haydon-Jones in straight sets. Many things bothered King concerning her advocacy for women's rights in sports. Among these concerns, she sought better pay for female tennis players, given the substantial differences in budgets between male and female players. In September 1970, there was the Pacific Southwest Open which was a tennis tournament. The prize money for men and women varied significantly, with the top prize for men being $12,500 and for women, a mere $1,500. Women's expenses were not covered unless they made the quarterfinals. This had bothered King and was the final straw for her. King and other 8 women did not play because of the budgets which they were willing to take the risk of expulsion from the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association. King and the other women organized the women-only Houston Virginia Slims invitational and this helped launch the series of women-only tournaments.[64]

1971

[edit]Although King won only one Grand Slam singles title in 1971, this was the best year of her career in terms of tournaments won (17). According to the International Tennis Hall of Fame, she played in 31 singles tournaments and compiled a 112–13 win–loss record.[33]

She started the year by winning eight of the first thirteen tournaments she played, defeating Rosemary Casals in seven finals. King's five losses during this period were to Françoise Dürr (twice), Casals (once), Ann Haydon-Jones (once), and Chris Evert (in St. Petersburg). At the time, King said that retiring from the match with Evert after splitting the first two sets was necessary because of leg cramps. But in early 1972, King admitted that cramps associated with an abortion caused the retirement.[65]

At the tournament in early May at Hurlingham, United Kingdom, King lost a second round match to an old rival, Christine Truman Janes (now 30 years old), 6–4, 6–2; but King recovered the next week to win the German Open in Hamburg on clay. Four weeks later at the Queen's Club tournament in London, King played Margaret Court for the first time in 1971, losing their final. At Wimbledon, King defeated Janes in the fourth round (6–2, 7–5) and Durr in the quarterfinals before losing unexpectedly to Evonne Goolagong in the semi-finals 6–4, 6–4. Two weeks after Wimbledon, King won the Rothmans North of England Championships on grass in Hoylake, United Kingdom, beating Virginia Wade, Court, and Casals in the last three rounds. She then played two clay court tournaments in Europe, winning neither, before resuming play in the United States.

In August, King won the indoor Houston tournament and the U.S. Women's Clay Court Championships in Indianapolis. King then switched back to grass and won the US Open without losing a set, defeating Evert in the semi-finals (6–3, 6–2) and Casals in the final. King then won the tournaments in Louisville, Phoenix, and London (Wembley Pro). King and Casals both defaulted at 6–6 in the final of the Pepsi Pacific Southwest Open in Los Angeles in September when their request to remove a lineswoman was denied, eventually resulting in the United States Lawn Tennis Association fining both players US$2,500.[66] To end the year, King played two tournaments in New Zealand but did not win either. She lost in Christchurch to Durr and in Auckland to Kerry Melville Reid. In 1971, King was the first female tennis player to earn $100,000 a year. Being one of her greatest accomplishments, this earned her congratulatory phone call from President Richard M. Nixon.[64]

1972

[edit]King won three Grand Slam singles titles in 1972, electing not to play the Australian Open despite being nearby when she played in New Zealand in late 1971. King said, "I was twenty-eight years old, and I was at the height of my powers. I'm quite sure I could have won the Grand Slam [in] ... 1972, but the Australian was such a minor-league tournament at that time.... More important, I did not want to miss any Virginia Slims winter tournaments. I was playing enough as it was."[67] Her dominance was aided by rival Margaret Court's absence from the tour due to childbirth during most of the 1972 season.

At the beginning of the year, King failed to win eight of the first ten tournaments she played. She won the title in San Francisco in mid-January. But then King lost in Long Beach to Françoise Dürr (although King claimed in her 1982 autobiography that she intentionally lost the match because of an argument with her husband[68]) and in Fort Lauderdale on clay to Chris Evert 6–1, 6–0. The inconsistent results continued through mid-April, in Oklahoma City (losing in the quarterfinals); Washington, D.C. (losing in the second round); and Dallas (losing to Nancy Richey Gunter after defeating Evert in the quarterfinals 6–7(4–5), 6–3, 7–5 and Evonne Goolagong in the semi-finals 1–6, 6–4, 6–1).[69] King won the title in Richmond; however, one week later, King lost in the semi-finals of the tournament in San Juan. This was followed in successive weeks by a loss in the Jacksonville final to Marie Neumannová Pinterová and in a St. Petersburg semi-final to Evert (6–2, 6–3).

King did not lose again until mid-August, winning six consecutive tournaments. She won the tournaments in Tucson and Indianapolis. King then won the French Open without losing a set and completed a career Grand Slam. She defeated Virginia Wade in the quarterfinals, Helga Niessen Masthoff in the semi-finals, and Goolagong in the final.[70] On grass, King then won the Wimbledon warm-up tournaments in Nottingham and Bristol and won Wimbledon itself for the fourth time. She lost only one set during the tournament, to Wade in the quarterfinals. That was followed by straight set wins over Rosemary Casals and Goolagong. When the tour returned to the United States, King did not win any of the three tournaments she played before the US Open, including a straight sets loss to Margaret Court in Newport. At the US Open, however, King won the tournament without losing a set, including a quarterfinal win over Wade, a semi-final defeat of Court, and a final win over Kerry Melville Reid. King finished the year by winning the tournaments in Charlotte and Phoenix (defeating Court in the final of both), a runner-up finish in Oakland (losing to Court), and a semifinal finish at the year-end championships in Boca Raton (losing to Evert).

1973

[edit]

1973 was Margaret Court's turn to win three Grand Slam singles titles, failing to win only Wimbledon, and was the clear world No. 1 for the year; this was her first full season since winning the Grand Slam in 1970, as she had missed significant portions of 1971 and 1972 due to childbirth. As during the previous year, King started 1973 inconsistently. She missed the first three Virginia Slims tournaments in January because of a wrist injury.[71] She then lost in the third round at the Virginia Slims of Miami tournament but won the Virginia Slims of Indianapolis tournament, defeating Court in the semi-finals 6–7, 7–6, 6–3 and Rosemary Casals in the final. The semi-final victory ended Court's 12-tournament and 59-match winning streaks,[72] with King saving at least three match points when down 5–4 (40–0) in the second set. Indianapolis was followed by five tournaments that King failed to win (Detroit, Boston, Chicago, Jacksonville, and the inaugural Family Circle Cup in Hilton Head, South Carolina). King lost to Court in two of those tournaments. After deciding not to defend her French Open singles title, King won four consecutive tournaments, including her fifth Wimbledon singles title when she defeated Kerry Melville Reid in the quarterfinals, Evonne Goolagong in the semi-finals on her eighth match point,[73] and Chris Evert in the final. King lost only nine points in the 6–0 bageling of Evert in the first set of their final.[74]

King also completed the Triple Crown at Wimbledon (winning the singles, women's doubles, and mixed doubles titles in the same year), thus becoming the first, and only, player to do so at Wimbledon in the Open Era. In none of the preceding tournaments, however, did King play Court. Their rivalry resumed in the final of the Virginia Slims of Nashville tournament, where Court won for the third time in four matches against King in 1973. (This was the last ever singles match between those players, with Court winning 21 and King 13 of their 34 matches.) Three weeks later at the US Open, King retired from her fourth-round match with Julie Heldman while ill[75] and suffering from the oppressive heat and humidity. When Heldman complained to the match umpire that King was taking too long between games, King reportedly told Heldman, "If you want the match that badly, you can have it!"[76] The Battle of the Sexes match against Bobby Riggs was held in the middle of the Virginia Slims of Houston tournament. King won her first and second round matches three days before playing Riggs, defeated Riggs, won her quarterfinal match the day after the Riggs match, and then lost the following day to Casals in the semifinals 7–6, 6–1. According to King, "I had nothing left to give."[77] To end the year, King won tournaments in Phoenix, Hawaii, and Tokyo and was the runner-up in Baltimore.

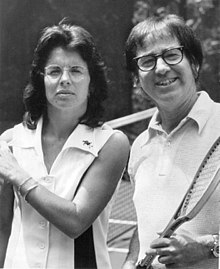

Battle of the Sexes

[edit]

In 1973, King defeated Bobby Riggs in an exhibition match, winning $100,000 ($707,000 in 2024 terms[78]).

Riggs had been a top men's player in the 1930s and 1940s in both the amateur and professional ranks. He won the Wimbledon men's singles title in 1939, and was considered the World No. 1 male tennis player for 1941, 1946, and 1947. He then became a self-described tennis "hustler" who played in promotional challenge matches. Claiming that the women's game was so inferior to the men's game that even a 55-year-old like himself could beat the current top female players, he challenged and defeated Margaret Court 6–2, 6–1. King, who previously had rejected challenges from Riggs, then accepted a lucrative financial offer to play him for $100,000 in a winner-takes-all match.

Dubbed "the Battle of the Sexes", the Riggs–King match took place at the Houston Astrodome in Texas on September 20, 1973. The match garnered huge publicity. In front of 30,492 spectators and a television audience estimated at 50 million people (U.S.), and 90 million in 37 countries, 29-year-old King beat the 55-year-old Riggs 6–4, 6–3, 6–3. The match is considered a significant event in developing greater recognition and respect for women's tennis. as King said to author and photographer Lynn Gilbert in her book Particular Passions: Talks with Women who Have Shaped Our Times, "I thought it would set us back 50 years if I didn't win that match. It would ruin the women's tour and affect all women's self-esteem,"[79] and that "to beat a 55-year-old guy was no thrill for me. The thrill was exposing a lot of new people to tennis."[80]

1974

[edit]King won five of the first seven tournaments she contested in 1974. She won the Virginia Slims of San Francisco, defeating Nancy Richey Gunter in the semi-finals and Chris Evert in the final. The following week in Indian Wells, California, King again defeated Gunter in the semi-finals but lost to Evert in the final. King then won tournaments in Fairfax, Virginia and Detroit before losing a semi-final match to Virginia Wade in Chicago. King won both tournaments she played in March, defeating Gunter in the Akron, Ohio final and Evert at the U.S. Indoor Championships final. Olga Morozova then upset King in her next two tournaments, at Philadelphia in the final and at Wimbledon in a quarterfinal 7–5, 6–2. Afterward, King did not play a tour match until the US Open, where she won her fourth singles title and third in the last four years. She defeated Rosemary Casals in a straight sets quarterfinal, avenged in the semi-finals her previous year's loss to Julie Heldman, and narrowly defeated Evonne Goolagong in the final. King did not reach a tournament final during the remainder of the year, losing to Heldman in an Orlando semi-final, Wade in a Phoenix semi-final, and Goolagong in a semi-final of the tour-ending Virginia Slims Championships in Los Angeles.

1975

[edit]In 1975, King played singles only half the year, as she retired (temporarily, as it turned out) from tournament singles competition immediately after winning her sixth Wimbledon singles title.

She began the year in San Francisco, defeating Françoise Dürr and Virginia Wade before losing to Chris Evert in the final. The following week, King won the Sarasota, Florida tournament, defeating Evert in the final 6–3, 6–2. Evert said immediately after the final, which was her thirteenth career match with King, "I think that's the best that Billie Jean has ever played. I hit some great shots but they just kept coming back at me."[81] Looking back at that match, King said, "I probably played so well because I had to, for the money. Out of frustration comes creativity. Right?"[82] Two months later, Wade defeated King in the semi-finals of the Philadelphia tournament. At the Austin, Texas, tournament in April, King defeated Evonne Goolagong 6–1, 6–3 before losing to Evert in the final. As King was serving for the match at 6–5 in the third set, a disputed line call went in Evert's favor. King said after the match that she was cheated out of the match and that she had never been angrier about a match.[83]

King played only one of the Wimbledon warm-up tournaments, defeating Olga Morozova in the Eastbourne semi-finals before losing to Wade in the final. Seeded third at Wimbledon, King defeated seventh seeded Morozova in the quarterfinals (6–3, 6–3) and then top seeded Evert in the semi-finals (2–6, 6–2, 6–3) after being down 3–0 (40–15) in the final set.[84] Evert blamed her semifinal defeat on a loss of concentration when she saw Jimmy Connors, her former fiancé, escorting Susan George into Centre Court. King, however, believes that the match turned around because King planned for and totally prepared for Wimbledon that year and told herself when she was on the verge of defeat, "Hey, Billie Jean, this is ridiculous. You paid the price. For once, you looked ahead. You're supposed to win. Get your bahoola in gear."[84] King then defeated fourth seeded Goolagong Cawley in the second most lopsided women's final ever at Wimbledon (6–0, 6–1). King called her performance a "near perfect match" and said to the news media, "I'm never coming back."[85]

The later years: 1976–1990

[edit]1976

[edit]Except for five Federation Cup singles matches that she won in straight sets in August, King played only in doubles and mixed doubles events from January through September. She partnered Phil Dent to the mixed doubles title at the US Open. She lost to Dianne Fromholtz Balestrat in both of the singles tournaments she played the remainder of the year. Looking back, King said, "I wasted 1976. After watching Chris Evert and Evonne [Goolagong] Cawley play the final at Wimbledon I asked myself what I was doing. So, despite my age and the operations, the Old Lady came back...."[86] King had knee surgery for the third time on November 9,[87] this time on her right knee,[88] and did not play the remainder of the year.

1977

[edit]King spent the first three months of the year rehabilitating her right knee after surgery in November 1976.[89]

In March 1977, King requested that the Women's Tennis Association (WTA) exercise its right to grant a wild card entry to King for the eight-player Virginia Slims Championships at Madison Square Garden in New York City. Margaret Court, who finished in sixth place on the Virginia Slims points list, had left the tour due to her fourth pregnancy and thus failed to qualify for the tournament because she did not play enough Virginia Slims tournaments leading up to the championships. This left a spot open in the draw, which the WTA filled with Mima Jaušovec. King then decided to play the Lionel Cup tournament in San Antonio, Texas, which the WTA harshly criticized because tournament officials there had allowed Renée Richards, a transgender athlete, to enter.[90] Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova, and Betty Stöve (president of the WTA) criticized King's decision because of Richards's unresolved and highly controversial status on the women's tennis tour. Evert said she was disappointed with King and that until Richards's status was resolved, "all of the women should stick together." Navratilova said, "Billie Jean is a bad girl pouting. She made a bad decision. She's mad because she could not get what she wanted." Stöve said that if King had wanted the competition, "[T]here are plenty of men around here she could've played with. She didn't have to choose a 'disputed' tournament."[91] The draw in San Antonio called for King to play Richards in the semi-finals had form held; however, Richards lost in the quarterfinals. King eventually won the tournament.

At the clay court Family Circle Cup in late March, King played for the last time her long-time rival Nancy Richey Gunter in the first round. King won 0–6, 7–6, 6–2. She defeated another clay court specialist, Virginia Ruzici, in the second round before winning only one game from Evert in the final.

At Wimbledon in the third round, King played Maria Bueno for the last time, with King winning 6–2, 7–5. In the quarterfinals, Evert defeated King for the first time at a Grand Slam singles tournament and for the first time on grass 6–1, 6–2 in just 46 minutes. Evert said it was the best match she had ever played on grass up to that point in her career,[92] and King said, "No excuses. Let's forget knees, ankles, toes, everything else. She just played beautiful tennis. I don't think many players would've beaten her today."[93] King also said after the match, "Maybe I can be happy being number eight instead of number one. At this stage, just playing, that's winning enough for me."[94] But when asked about retirement, King said, "Retire? Quit tournament tennis? You gotta be kidding. It just means I've got a lot more work. I've got to make myself match tough ... mentally as well as physically. I gotta go out and kill myself for the next six months. It's a long, arduous process. I will suffer. But I will be back."[95] There was a small historic note at Wimbledon 1977 in that it was the first time ever that King competed at the championships that she did not reach a final. From her debut in 1961 until 1976, she had played in the final of one of the three championship events for women every year. Perhaps there was irony in this in that as the Wimbledon champion with the most titles in its history, the event was celebrating its centenary in the year King failed to make a final for the first time. The only other years she competed at the championship and did not feature in a final were 1980 and 1982. In her entire Wimbledon career of 22 competitions, King never failed to be a semi-finalist in at least one event every year.[96]

Evert repeated her Wimbledon quarterfinal victory over King at the clay court US Open, winning 6–2, 6–0. This loss prompted King to say, "I better get it together by October or November or that's it. I'll have to make some big decisions. I'm not 20-years-old and I can't just go out and change my game. It's only the last four weeks I haven't been in [knee] pain. [But if] I keep using that as a copout, I shouldn't play."[97]

The remainder of the year, King's win–loss record was 31–3, losing to only Evert, Dianne Fromholtz Balestrat, and Michelle Tyler. King won five of the eight tournaments she entered plus both of her Wightman Cup matches. She defeated Navratilova all four times they played, including three times in three consecutive weeks, and beat Wimbledon champion Virginia Wade twice. Beginning September 26, King played seven consecutive weeks. She lost to Tyler in the second round in Palm Harbor, Florida, and Fromholtz Balestrat in the semi-finals in Atlanta. She then won three hard court tournaments in three consecutive weeks. She defeated Navratilova and Wendy Turnbull to win in Phoenix, losing only four points to Turnbull in the third set of the final.[98] The next week, she defeated Navratilova, Fromholtz Balestrat, and Wimbledon runner-up Stöve to win in São Paulo. The third week, she defeated Ruzici, Stöve, and Janet Newberry Wright to win in San Juan. In November, Evert snapped King's 18-match winning streak in the final of the Colgate Series Championships in Mission Hills, California. King then won her Wightman Cup matches, defeated Navratilova to win the tournament in Japan, and beat Wade to win the Bremar Cup in London. King said, "I have never had a run like this, even in the years when I was Wimbledon champion. At 34, I feel fitter than when I was 24."[99]

1978

[edit]

King played ten singles tournaments during the first half of 1978, limiting herself to doubles after Wimbledon.

To start the year, King was the runner-up in Houston and Kansas City (losing to Martina Navratilova in both) and in Philadelphia (losing to Chris Evert). At the Virginia Slims Championships, King lost her first round robin match to Virginia Wade and defaulted her two remaining round robin matches because of a leg injury sustained during the first match.

At Wimbledon, King played with a painful heel spur in her left foot and lost to Evert in the quarterfinals for the second consecutive year 6–3, 3–6, 6–2. The match was on-serve in the third set with King serving at 2–3 (40–0) before Evert won five consecutive points to break serve. King won a total of only two points during the last two games. King said after the match, "I don't think my mobility is very good and that's what I need to beat her. Physically, she [Evert] tears your guts apart unless you can stay with her. I'm really disappointed. I really wanted to play well. I just couldn't cut it because of my heel."[100] King and her partner Ray Ruffels lost in the final of mixed doubles in straight sets.

King teamed with Navratilova to win the women's doubles title at the US Open, King's fourth women's doubles title at that tournament and fourteenth Grand Slam women's doubles title overall. To end the year, King was undefeated in five doubles matches (four with Evert and one with Rosemary Casals) as the U.S. won the Federation Cup in Melbourne, Australia. She also teamed with Tracy Austin in the 1978 Wightman Cup against Great Britain, beating Anne Hobbs & Sue Mappin in the best of seven rubbers, despite the US losing the Cup 3–4. During the Federation Cup competition, King hinted at retirement from future major singles competitions and said that she was "sick and tired of continued surgery" in trying to get fit enough for those events.[101] Nevertheless, King had foot surgery on December 22 in an attempt to regain mobility for a return to the tennis tour.[102]

1979

[edit]During the first half of 1979, King played only one event – doubles in the Federation Cup tie against Spain – because of major surgery to her left foot during December 1978.

King returned to singles competition at the Wimbledon warm-up tournament in Chichester. She defeated the reigning Wimbledon champion, Martina Navratilova, in a 48-minute quarterfinal 6–1, 6–2[103] before losing to Evonne Goolagong Cawley in the semi-finals 1–6, 6–4, 10–8. Seeded seventh at Wimbledon, King defeated Hana Mandlíková in the fourth round before losing the last six games[104] of the quarterfinal match with fourth-seeded Tracy Austin 6–4, 6–7(5), 6–2. King partnered with Navratilova at Wimbledon to win King's 20th and final Wimbledon title, breaking Elizabeth Ryan's longstanding record of 19 Wimbledon titles just one day after Ryan collapsed and died at Wimbledon.[105]

At the US Open, the ninth-seeded King reached the quarterfinals without dropping a set, where she upset the fourth-seeded Virginia Wade 6–3, 7–6(4). Next up was a semi-final match with the four-time defending champion and top-seeded Chris Evert; however, with King hampered by a neck injury sustained during a bear hug with a friend the day before the match, Evert won 6–1, 6–0, including the last eleven games and 48 of the last 63 points.[106] This was Evert's eighth consecutive win over King, with Evert during those matches losing only one set and 31 games and winning four 6–0 sets.[106] Evert said after the match, "Psychologically, I feel very confident when I ... play her."[106]

The following week in Tokyo, King won her first singles title in almost two years, defeating Goolagong Cawley in the final. In November in Stockholm, King defeated Betty Stöve in the final after Stöve lost her concentration while serving for the match at 5–4 in the third set.[107] Three weeks later in Brighton, King lost a semi-final match with Navratilova 7–5, 0–6, 7–6(3) after King led 6–5 in the third set.[108] She ended the year with a quarterfinal loss in Melbourne (not the Australian Open), a second round loss in Sydney, and a three-set semi-final loss to Austin in Tokyo.

1980–1981

[edit]King won the tournament in Houston that began in February, snapping Martina Navratilova's 28-match winning streak in the straight-sets final.[109]

At the winter series-ending Avon Championships in March, King defeated Virginia Wade in her first round robin match 6–1, 6–3. After Wade held serve at love to open the match, King won nine consecutive games and lost only nine points during those games.[109] King then lost her second round robin match to Navratilova and defeated Wendy Turnbull in an elimination round match, before losing to Tracy Austin in the semi-finals

King played the 1980 French Open, her first time since she won the event in 1972 and completed a career singles Grand Slam.[110][citation needed] She was seeded second but lost in the quarterfinals to fifth-seeded Dianne Fromholtz Balestrat of Australia.[111]

At Wimbledon, King defeated Pam Shriver in a two-hour, forty minute fourth round match after King saved a match point in the second set and recovered from a 4–2 (40–0) deficit in the third set with Shriver serving.[112] In a quarterfinal that took two days to complete, King lost to two-time defending champion and top-seeded Navratilova 7–6, 1–6, 10–8. The beginning of the match was delayed until late afternoon because of rain. Because she wore glasses, King agreed to start the match then on condition that tournament officials immediately suspend the match if the rain resumed. During the first set, drizzle began to fall; however, the chair umpire refused to suspend the match. King led in the tiebreaker 5–1 before Navratilova came back to win the set, whereupon the umpire then agreed to the suspension. When the match resumed the next day, King won 20 of the first 23 points to take a 5–0 lead in the second set and lost a total of seven points while winning the set in just 17 minutes. In the third set, Navratilova broke serve to take a 2–0 lead before King broke back twice and eventually served for the match at 6–5. King then hit four volley errors, enabling Navratilova to break serve at love and even the match. King saved three match points while serving at 6–7 and three more match points while serving at 7–8. During the change-over between games at 8–9, King's glasses broke for the first time in her career. She had a spare pair, but they did not feel the same. King saved two match points before Navratilova broke serve to win the match. King said, "I think that may be the single match in my career that I could have won if I hadn't had bad eyes."[113][114][115]

King teamed with Navratilova to win King's 39th and final Grand Slam title at the US Open. Navratilova then decided she wanted a new doubles partner and started playing with Shriver but refused to discuss the change directly with King. She finally confronted Navratilova during the spring of 1981, reportedly saying to her, "Tell me I'm too old ... but tell me something." Navratilova refused to talk about it.[116]

King had minor knee surgery on November 14 in San Francisco to remove adhesions and cartilage.[117]

1982–1983

[edit]In 1982, King began a comeback, winning the Wimbledon warm-up tournament the 1982 Edgbaston Cup in Birmingham, her first singles title in more than two years. King was 38 years old and the twelfth-seed at Wimbledon. In her third round match with Tanya Harford of South Africa, King was down 7–5, 5–4 (40–0) before Harford's apparent winner was deemed 'not up' by the umpire, something the South African protested vehemently. King then saved the next two match points[118] to win the second set 7–6(2) and then the third set 6–3. King said in her post-match press conference, "I can't recall the previous time I have been so close to defeat and won. When I was down 4–5 and love–40, I told myself, 'You have been here 21 years, so use that experience and hang on.'"[119] In the fourth round, King upset sixth-seeded Australian Wendy Turnbull in straight sets. King then upset third-seeded Tracy Austin in the quarterfinals 3–6, 6–4, 6–2 to become the oldest female semi-finalist at Wimbledon since Dorothea Douglass Lambert Chambers in 1920. This was King's first career victory over Austin after five defeats and reversed the result of their 1979 Wimbledon quarterfinal. King said in her post-match press conference, "Today, I looked at the scoreboard when I was 2–0 in the third set and the '2' seemed to be getting bigger and bigger. In 1979, when I was up 2–0 at the same stage, I was tired and didn't have anything left. But today I felt so much better and was great mentally."[120] Two days later in the semi-finals, which was King's 250th career match at Wimbledon in singles, women's doubles, and mixed doubles,[121] the second-seeded Chris Evert defeated King on her fifth match point 7–6(4), 2–6, 6–3. King was down a set and 2–1 in the second set before winning five consecutive games to even the match.[122] King explained that she actually lost the match in the first set by failing to convert break points at 15–40 in the second and fourth games.[123][124] Having started the year in retirement, King finished 1982 ranked 14 in the world.

In 1983, she reached the semi-finals in her final appearance at Wimbledon, losing to Andrea Jaeger 6–1, 6–1 after beating Kathy Jordan in the quarterfinals, seventh-seeded Wendy Turnbull in the fourth round, and Rosemary Casals, her longtime doubles partner, in the third round. Jaeger claims that she was highly motivated to defeat King because King had defeated Turnbull, a favorite of Jaeger's, and because King refused a towel from an attendant just before her match with Jaeger, explaining, "I'm not going to sweat in this match."

King became the oldest WTA player to win a singles tournament when she won the Edgbaston Cup grass court tournament in Birmingham at 39 years, 7 months and 23 days after a straight-sets victory in the final against Alycia Moulton.[125] Her tally of 20 Wimbledon titles remained when partnered with Steve Denton and the no.1 seeds in the mixed doubles, they lost 6–7(5–7), 7–6(7–5), 7–5 to John Lloyd & Wendy Turnbull in the final, King being the only player to drop her service in the final game. At her final appearance at the US Open later in 1983, King didn't play singles, but partnered Sharon Walsh in the women's doubles, reaching the semi-finals and Trey Waltke in the mixed doubles, losing in the second round. The final official singles match of King's career was a second round loss to Catherine Tanvier at the 1983 Australian Open.

1984 to present

[edit]King played doubles sporadically from 1984 through 1990. She and Vijay Amritraj were seeded sixth for the Wimbledon mixed doubles 1984, but they withdrew before the tournament began. She retired from competitive play in doubles in March 1990. In her last competitive doubles match, King and her partner, Jennifer Capriati, lost a second round match to Brenda Schultz-McCarthy and Andrea Temesvári 6–3, 6–2 at the Virginia Slims of Florida tournament.

King became the captain of the United States Fed Cup team and coach of its women's Olympic tennis squad. She guided the U.S. to the Fed Cup championship in 1996 and helped Lindsay Davenport, Gigi Fernández, and Mary Joe Fernández capture Olympic gold medals.

In 2002, King dismissed Capriati from the Fed Cup team, saying Capriati had violated rules that forbade bringing along and practicing with personal coaches.[126] Opinion was sharply divided, with many supporting King's decision but many feeling the punishment was too harsh, especially in hindsight when Monica Seles and Lisa Raymond were defeated by lower-ranked Austrians Barbara Schett and Barbara Schwartz. The following year, Zina Garrison succeeded King as Fed Cup captain.

Activism within the tennis profession

[edit]Player compensation

[edit]Before the start of the open era in 1968, King earned US$100 a week as a playground instructor and student at California State University, Los Angeles when not playing in major tennis tournaments.[79]

In 1967, King criticized the United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA) in a series of press conferences, denouncing what she called the USLTA's practice of "shamateurism", where top players were paid under the table to guarantee their entry into tournaments. King argued that this was corrupt and kept the game highly elitist. King quickly became a significant force in the opening of tennis to professionalism. King said this about the amateur game:

In America, tennis players are not people. If you are in tennis, you are a cross between a panhandler and a visiting in-law. You're not respected, you're tolerated. In England, you're respected as an artist. In Europe, you're a person of importance. Manuel Santana gets decorated by Franco. The Queen leads the applause. How many times have I been presented at the White House? You work all your life to win Wimbledon and Forest Hills and all the people say is, "That's nice. Now what are you going to do with your life?" They don't ask Mickey Mantle that. Stop 12 people on the street and ask them who Roy Emerson is and they're stuck for an answer, but they know the third-string right guard for the Rams. I'd like to see tennis get out of its "sissy" image and see some guy yell, "Hit it, ya bum" and see it be a game you don't have to have a lorgnette or a sash across your tuxedo to get in to watch.[127]

Push for female equality

[edit]When the open era began, King campaigned for equal prize money in the men's and women's games. In 1971, her husband, Larry King created the idea to form a nine player women's group with the financial backing of World Tennis magazine founder Gladys Heldman and the sponsorship of Virginia Slims chairman Joe Cullman. King became the first woman athlete to earn over US$100,000 in prize money;[128] however, inequalities continued. King won the US Open in 1972 but received US$15,000 less than the men's champion Ilie Năstase. She stated that she would not play the next year if the prize money was not equal. In 1973, the US Open became the first major tournament to offer equal prize money for men and women.

King led player efforts to support the first professional women's tennis tour in the 1970s called the Virginia Slims, founded by Gladys Heldman and funded by Joseph Cullman of Philip Morris.[129] Once the tour took flight, King worked tirelessly to promote it even though many of the other top players were not supportive. "For three years we had two tours and because of their governments [Martina] Navratilova and Olga Morozova had to play the other tour. Chris [Evert], Margaret [Court], Virginia [Wade], they let us do the pioneering work and they weren't very nice to us. If you go back and look at the old quotes; they played for the love of the game, we played for the money. When we got backing and money, we were all playing together – I wonder why? I tried not to get upset with them. Forgiveness is important. Our job was to have one voice and win them over."[130]

In 1973, King became the first president of the women's players union – the Women's Tennis Association. In 1974, she, with husband Larry King and Jim Jorgensen, founded womenSports magazine and started the Women's Sports Foundation.[131] Also in 1974, World TeamTennis began, founded by Larry King, Dennis Murphy, Frank Barman and Jordan Kaiser.[132] She became league commissioner in 1982 and major owner in 1984.

King is a member of the Board of Honorary Trustees for the Sports Museum of America,[133] which opened in 2008. The museum is the home of the Billie Jean King International Women's Sports Center, a comprehensive women's sports hall of fame and exhibit.[134]

Billie Jean King through her various efforts has been said to have started the second wave of feminism. Not just for women in sports, but for women everywhere, Kings triumphs have led to greater opportunities . For example, it is said that “In a single tennis match, Billie Jean King was able to do more for the cause of women than most feminists can achieve in a lifetime” (Paule-Koba). Kings win against Bobby Riggs, one of the greatest male tennis players of their time, was not just a win for herself, but a win for women everywhere. After Riggs sexist comments leading up to the match, King realized she had a lot more to win the match for then a trophy. “Billie Jean King was the rare athlete who brought together sport and feminism, and, in doing so, she put a human face on the ideals of liberal feminism” (Paule-Koba). Since her win against Riggs, King has started her own tour for women to create equal pay for them, influenced and aided the title IX legislation, and helped create the Women's sports foundation known as womenSports and World Team Tennis.[135]

Other activities

[edit]King's husband Larry co-founded World Team Tennis in 1973 with Dennis Murphy, Jordan Kaiser, and Fred Barman and WTT began in 1974.[136] The couple used their savings to put on a team tennis event at the Oakland Coliseum.[136] King remained involved with World Team Tennis for decades, eventually sharing ownership with her ex-husband, her life partner Ilana Kloss and USTA.[136] In 2017, King sold her majority ownership stake of the league to Mark Ein and Fred Luddy. WTT was based on her philosophy for gender equality and it had been running continuously for over 40 years.[137]

In 1999, King was elected to serve on the board of directors of Philip Morris Incorporated, garnering some criticism from anti-tobacco groups.[138] She no longer serves in that capacity.

As of 2012[update] King was involved in the Women's Sports Foundation and the Elton John AIDS Foundation.[139] She also served on the President's Council for Fitness, Sports and Nutrition as a way to encourage young people to stay active.[139]

In 2008, King published the book Pressure is a Privilege: Lessons I've Learned from Life and the Battle of the Sexes.[140]

In December 2013, US President Barack Obama appointed King and openly gay ice hockey player Caitlin Cahow to represent the United States at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia. This has been interpreted as a signal on gay rights, in the context of concerns and controversies at the 2014 Winter Olympics regarding LGBT rights in Russia.[141] King was forced to drop out of the delegation due to her mother's ill health. Betty Moffitt, King's mother, died on February 7, 2014, the day of the 2014 Winter Olympics opening ceremony.[142]

Billie Jean was selected to deliver the Northwestern University commencement address on June 16, 2017, in Evanston, Illinois.[143]

She attended the 75th Golden Globe Awards in 2018 as a guest of Emma Stone.[144]

King and Kloss became minority owners of the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team in September 2018, and the WNBA's Los Angeles Sparks basketball team.[145][146] In October 2020, they became part of the ownership group of Angel City FC, a Los Angeles–based team set to start play in the National Women's Soccer League in 2022.[147]

King is also an investor in Just Women's Sports, an American media platform dedicated to women's sports.[148]

On June 29, 2023, the Mark Walter Group and BJK Enterprises purchased the intellectual property and other key elements of the Premier Hockey Federation (PHF), a professional women's hockey league in the United States and Canada.[149] Headed by Mark Walter and King, respectively, both businesses had entered a partnership with the Professional Women's Hockey Players Association (PWHPA) in May 2022, with the intent to create a new professional women's ice hockey league in North America.[150] The buyout changed the landscape in North American women's professional hockey, as it resulted in a single league with stakeholders from both the PHF and PWHPA. The new league began on January 1, 2024, with the first game played between New York and Toronto in Toronto.[151][152]

Also in 2023, King competed in season ten of The Masked Singer as "Royal Hen". She was the first of Group B to be eliminated on "A Celebration of Elton John".[153]

Awards, honors, and tributes

[edit]Tributes from other players

[edit]

Margaret Court, who won more Grand Slam titles than anyone, has said that King was "the greatest competitor I've ever known".[154]

Chris Evert, winner of 18 Grand Slam singles titles, has said, "She's the wisest human being that I've ever met and has vision people can only dream about. Billie Jean King is my mentor and has given me advice about my tennis and my boyfriends. On dealing with my parents and even how to raise children. And she doesn't have any."[155]

In 1979, several top players were asked who they would pick to help them recover from a hypothetical deficit of 1–5 (15–40) in the third set of a match on Wimbledon's Centre Court. Martina Navratilova, Rosemary Casals, and Françoise Dürr all picked King. Navratilova said, "I would have to pick Billie Jean at her best. Consistently, Chris [Evert] is hardest to beat but for one big occasion, one big match, one crucial point, yes, it would have to be Billie Jean." Casals said, "No matter how far down you got her, you never could be sure of beating her."[156]

Awards and honors

[edit]- King was the Associated Press Female Athlete of the Year in 1967.[157]

- In 1972, King became the first female athlete ever to be named Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year.[158][159]

- In 1975, Seventeen magazine found that King was the most admired woman in the world from a poll of its readers. Golda Meir, who had been Israel's prime minister until the previous year, finished second.[79] In a May 19, 1975, Sports Illustrated article about King, Frank Deford noted that she had become something of a sex symbol.[82]

- King was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1987.[33]

- Life magazine in 1990 named her one of the "100 Most Important Americans of the 20th Century".[79]

- King was the recipient of the 1999 Arthur Ashe Courage Award.[160]

- In 1999 King was inducted into the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame.[161]

- In 2000, King received an award from GLAAD, an organization devoted to reducing discrimination against gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender people, for "furthering the visibility and inclusion of the community in her work".[162]

- In 2003, the International Tennis Federation (ITF) presented her with its highest accolade, the Philippe Chatrier Award, for her contributions to tennis both on and off the court.

- In 2006, the Women's Sports Foundation began to sponsor the Billie Awards, which are named after and hosted by King.[163]

- On August 28, 2006, the USTA National Tennis Center in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park was rededicated as the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center.[164] John McEnroe, Venus Williams, Jimmy Connors, and Chris Evert were among the speakers during the rededication ceremony.

- In 2006, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and his wife Maria Shriver inducted King into the California Hall of Fame located at The California Museum for History, Women, and the Arts.[165][166]

- On November 20, 2007, King was presented with the 2007 Sunday Times Sports Women of the Year Lifetime Achievement award for her contribution to sport both on and off the court.[130]

- She was honored by the Office of the Manhattan Borough President in March 2008 and was included in a map of historical sites related or dedicated to important women.[167]

- On August 12, 2009, President Barack Obama awarded King the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her work advocating for the rights of women and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community.[168][169] This made her the first female athlete to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[170]

- She was inducted into the Southern California Tennis Hall of Fame on August 5, 2011.[171]

- On August 2, 2013, King was among the first class of inductees into the National Gay and Lesbian Sports Hall of Fame.[172]

- In 2014, she was named one of ESPNW's Impact 25.[173]

- King was shown in Marie Claire magazine's "The 8 Greatest Moments for Women in Sports".[174]

- King received the BBC Sports Personality of the Year Lifetime Achievement Award on December 16, 2018. It was presented to by long-time friend and fellow tennis player and broadcaster Sue Barker, making King only the second American (after Michael Phelps) and the first American woman to win the award.[175]

- Cal State LA's more than 11 acres (4.5 ha) athletic facility is named the Billie Jean King Sports Complex. The sports complex—which was approved by the California State University Board of Trustees on September 21—features the Eagle's Nest Arena, the University Stadium, Jesse Owens Track and Field, Reeder Field (baseball), the swimming pool, and tennis and basketball courts.[176]

- On September 21, 2019, her hometown of Long Beach, California held a grand opening of the Long Beach Public Library's new main library, named after King. The Billie Jean King Main Library is located in Downtown Long Beach, and has exhibited King's Presidential Medal of Freedom.

- The Fed Cup, the premier international team competition in women's tennis, was renamed the Billie Jean King Cup in September 2020 in her honor.

- 2020 and 2024 World Series champion as part owner of the Los Angeles Dodgers[177]

- In 2021, King received the Laureus Lifetime Achievement Award, in recognition of her excellence on the tennis court as well as her life's work in pursuit of gender and racial equality.[178][179]

- In June 2022, King was awarded the French Legion of Honour by President Emmanuel Macron, on the 50th anniversary of her French Open victory.[180]

- Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (sports entertainment)[181]

- In 2024, King received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement, presented by Christiane Amanpour.[182]

- King received a Congressional Gold Medal in September 2024 for her "courageous and groundbreaking leadership in advancing equal rights for women in athletics, education, and society."[183]

Playing style and personality

[edit]

King learned to play tennis on the public courts of Long Beach, California, and was coached by tennis teacher Clyde Walker.[10] She furthered her tennis career at the Los Angeles Tennis Club.

She was an aggressive, hard-hitting net-rusher with excellent speed;[79] Chris Evert, however, said about King, "Her weakness is her impatience."[184]

Concerning her motivations in life and tennis, King said,

I'm a perfectionist much more than I'm a super competitor, and there's a big difference there.... I've been painted as a person who only competes. ... But most of all, I get off on hitting a shot correctly. ... Any woman who wants to achieve anything has to be aggressive and tough, but the press never sees us as multidimensional. They don't see the emotions, the downs....[185]

In a 1984 interview, just after she had turned 40, King said,

Sometimes when I'm watching someone like Martina [Navratilova], I remember how nice it was to be No. 1. Believe me, it's the best time in your life. Don't let anyone ever tell you different. ... My only regret is that I had to do too much off the court. Deep down, I wonder how good I really could have been if I [had] concentrated just on tennis.[186]

Julie Heldman, who frequently played King but never felt close to her, said about King's personality,

One of the reasons I've never gotten close to Billie Jean is that I've never felt strong enough to survive against that overwhelming personality of hers. She talks about me being the smart one. Let me tell you, Billie Jean's the smartest one, the cleverest one you'll ever see. She was the one who was able to channel everything into winning, into being the most consummate tennis player.[82]

Kristien Shaw, another frequent opponent of King, said,

For a time, I think I was as close to Billie Jean as anyone ever was. But as soon as I got to the point where I could read her too well, she tried to dissociate the relationship. She doesn't want to risk appearing weak in front of anybody. She told me once that if you want to be the best, you must never let anyone, anyone, know what you really feel. You see, she told me, they can't hurt you if they don't know.[82]

Concerning the qualities of a champion tennis player, King said,

The difference between me at my peak and me in the last few years of my career is that when I was the champion I had the ultimate in confidence. When I decided, under pressure ... that I had to go with my very weakest shot – forehand down the line – I was positive that I could pull it off ... when it mattered the most. Even more than that; going into a match, I knew it was my weakest shot, and I knew in a tight spot my opponent was going to dare me to hit it, and I knew I could hit it those two or three or four times in a match when I absolutely had to. ... The cliché is to say that ... champions play the big points better. Yes, but that's only the half of it. The champions play their weaknesses better....[187]

In popular culture

[edit]- King's friend Elton John wrote the song "Philadelphia Freedom", a nod to her World TeamTennis team, for King. The song was released New Year's Day 1975 and became a number one hit.[33]

- Charles M. Schulz, creator of the Peanuts comic strip, was an admirer and close friend;[188] Schulz referred to King several times in Peanuts and used the comic strip to support the women's sports movement after becoming friends with King.[189]

- Actress Holly Hunter portrayed King in the 2001 ABC television film When Billie Beat Bobby.[190] King played a judge on Law & Order in 2007,[191] and appeared as herself on The Odd Couple in 1973, The L Word in 2006, Ugly Betty in May 2009, Fresh Off The Boat in 2016, and The Bold Type in 2020.[192] King's name appears in the lyrics of the Le Tigre song "Hot Topic."[193]

- Actress Emma Stone portrayed King in the 2017 biographical film Battle of the Sexes.[194][195]

- The Ted Tinling designed dress King wore for the Battle of the Sexes match is part of a Smithsonian Museum collection.[196]

- In 2023, King competed in the tenth season of The Masked Singer as "Royal Hen". She sang "Philadelphia Freedom" and "Don't Go Breaking My Heart" in an episode that was a tribute to Elton John where she was eliminated.[197]

Personal life

[edit]Billie Jean and Larry King were engaged in fall of 1964 and married in Long Beach, California, on September 17, 1965.[10][198] Billie Jean credited Larry with introducing her to feminism and for pushing her to pursue tennis as a career.[21] Billie Jean later said she "was totally in love with Larry" when they married.[130]

By 1968, King realized that she was attracted to women.[199] In 1971, she began an affair with her secretary, Marilyn Barnett (born Marilyn Kathryn McRae on January 28, 1948). Barnett had been living rent-free in the Kings' Malibu house. In 1979, the Kings asked Barnett to leave their house, but she did not want to. Refusing to leave the house, Barnett threatened to leak records and receipts that she had kept over the years. These receipts included letters from Billie Jean to Marilyn, credit card receipts, and paid bills. After a suicide attempt where she jumped off the balcony of the house leaving her a paraplegic, Barnett sued the Kings in a May 1981 palimony lawsuit for half their income and the Malibu house where she had been staying. Billie Jean acknowledged the relationship between her and Marilyn shortly afterward, making Billie Jean the first prominent female professional athlete to come out.[200] Feeling she could not admit to the extent of the relationship, Billie Jean publicly called it a fling and a mistake. The lawsuit caused Billie Jean to lose an estimated $2 million in endorsements and forced her to prolong her tennis career to pay attorneys.[155] In December 1981, a court order stipulated that Barnett leave the house and that her threats to publish private correspondence between her and King in exchange for money came close to extortion. Barnett's palimony suit was thrown out of court in November 1982.[201] But in a bizarre twist of fate, a few months later in March 1983, the house that had been contested was destroyed during a series of freak storms that lashed the southern California coastline.[202]

Also in 1971, King had an abortion that was made public in a Ms. magazine article.[199] Larry had revealed Billie Jean's abortion without consulting her.[199]

Concerning the personal cost of concealing her sexuality for so many years, Billie Jean said:

I wanted to tell the truth but my parents were homophobic and I was in the closet. As well as that, I had people tell me that if I talked about what I was going through, it would be the end of the women's tour. I couldn't get a closet deep enough. One of my big goals was always to be honest with my parents and I couldn't be for a long time. I tried to bring up the subject but felt I couldn't. My mother would say, "We're not talking about things like that", and I was pretty easily stopped because I was reluctant anyway. I ended up with an eating disorder that came from trying to numb myself from my feelings. I needed to surrender far sooner than I did. At the age of 51, I was finally able to talk about it properly with my parents and no longer did I have to measure my words with them. That was a turning point for me as it meant I didn't have regrets anymore.[130]

Billie Jean and Larry remained married through the palimony suit fallout.[21] Their marriage ended in 1987 after Billie Jean fell in love with her doubles partner, Ilana Kloss.[21] Billie Jean and Larry nevertheless remained close, and she is the godmother of Larry's son from his subsequent marriage.[21]

On October 18, 2018, King and Kloss were married by former New York City Mayor David Dinkins in a secret ceremony.[203] King and her wife Kloss have residences in New York City and Chicago.[204][205] King is a vegetarian.[206]

It was announced in March 2021 that King would be an advisor to First Women's Bank in Chicago.[207]

Grand Slam statistics

[edit]Grand Slam single finals

[edit]18 finals (12 titles, 6 runners-up)

| Result | Year | Tournament | Surface | Opponent | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss | 1963 | Wimbledon | Grass | 3–6, 4–6 | |

| Loss | 1965 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 6–8, 5–7 | |

| Win | 1966 | Wimbledon | Grass | 6–3, 3–6, 6–1 | |

| Win | 1967 | Wimbledon (2) | Grass | 6–3, 6–4 | |

| Win | 1967 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 11–9, 6–4 | |

| Win | 1968 | Australian Championships | Grass | 6–1, 6–2 | |

| ↓ Open Era ↓ | |||||