Nicotine: Difference between revisions

m →Dependence and withdrawal: minor edit |

→Cite journal with Wikipedia template filling, tweak cites |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Nicotine''' is an [[alkaloid]] found in the [[nightshade]] family of plants (''[[Solanaceae]]''); [[biosynthesis]] takes place in the roots and accumulation occurs in the leaves. |

'''Nicotine''' is an [[alkaloid]] found in the [[nightshade]] family of plants (''[[Solanaceae]]''); [[biosynthesis]] takes place in the roots and accumulation occurs in the leaves. |

||

It constitutes approximately 0.6–3.0% of the dry weight of [[tobacco]]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://dccps.nci.nih.gov/tcrb/monographs/9/m9_3.PDF |format=PDF|title=Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9}}</ref> and is present in the range of 2-7 µg/kg of various edible plants.<ref name="acs">{{cite web |url=http://pubs.acs.org/cgi-bin/abstract.cgi/jafcau/1999/47/i08/abs/jf990089w.html |title=Determination of the Nicotine Content of Various Edible Nightshades (Solanaceae) and Their Products and Estimation of the Associated Dietary Nicotine Intake |

It constitutes approximately 0.6–3.0% of the dry weight of [[tobacco]]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://dccps.nci.nih.gov/tcrb/monographs/9/m9_3.PDF |format=PDF|title=Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9}}</ref> and is present in the range of 2-7 µg/kg of various edible plants.<ref name="acs">{{cite web |url=http://pubs.acs.org/cgi-bin/abstract.cgi/jafcau/1999/47/i08/abs/jf990089w.html |title=Determination of the Nicotine Content of Various Edible Nightshades (Solanaceae) and Their Products and Estimation of the Associated Dietary Nicotine Intake |accessdate=2008-10-05}}</ref> |

||

It functions as an [[Plant defense against herbivory|antiherbivore chemical]]; therefore, nicotine was widely used as an [[insecticide]] in the past<ref>{{Cite book |

It functions as an [[Plant defense against herbivory|antiherbivore chemical]]; therefore, nicotine was widely used as an [[insecticide]] in the past<ref>{{Cite book |

||

| last = Rodgman |

| last = Rodgman |

||

| Line 99: | Line 99: | ||

| pmc = 2598548}}</ref> |

| pmc = 2598548}}</ref> |

||

Research in 2011 has found that nicotine inhibits chromatin-modifying enzymes (class I and II histone deacetylases) which increases the ability of [[cocaine]] to cause an [[addiction]].<ref> |

Research in 2011 has found that nicotine inhibits chromatin-modifying enzymes (class I and II histone deacetylases) which increases the ability of [[cocaine]] to cause an [[addiction]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Volkow ND |title=Epigenetics of nicotine: another nail in the coughing |journal=Sci Transl Med |volume=3 |issue=107 |pages=107ps43 |year=2011 |month=November |pmid=22049068 |doi=10.1126/scitranslmed.3003278 |url=http://stm.sciencemag.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=short&pmid=22049068}}</ref> |

||

== History and name == |

== History and name == |

||

Nicotine is named after the tobacco plant ''[[Nicotiana tabacum]],'' which in turn is named after [[Jean Nicot|Jean Nicot de Villemain]], [[France|French]] ambassador in [[Portugal]], who sent tobacco and seeds brought from [[Brazil]] by the Portuguese colonist in [[São Paulo]], Luís de Góis (also a future jesuit in India), to [[Paris]] in 1560, and promoted their medicinal use. Nicotine was first isolated from the tobacco plant in 1828 by physician Wilhelm Heinrich Posselt and chemist Karl Ludwig Reimann of [[Germany]], who considered it a poison.<ref> |

Nicotine is named after the tobacco plant ''[[Nicotiana tabacum]],'' which in turn is named after [[Jean Nicot|Jean Nicot de Villemain]], [[France|French]] ambassador in [[Portugal]], who sent tobacco and seeds brought from [[Brazil]] by the Portuguese colonist in [[São Paulo]], Luís de Góis (also a future jesuit in India), to [[Paris]] in 1560, and promoted their medicinal use. Nicotine was first isolated from the tobacco plant in 1828 by physician Wilhelm Heinrich Posselt and chemist Karl Ludwig Reimann of [[Germany]], who considered it a poison.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Posselt, W.; Reimann, L. |title=Chemische Untersuchung des Tabaks und Darstellung eines eigenthümlich wirksamen Prinzips dieser Pflanze |trans_title=Chemical investigation of tobacco and preparation of a characteristically active constituent of this plant |language=German |journal=Magazin für Pharmacie |volume=6 |issue=24 |pages=138–161 |year=1828 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=cgkCAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA1-PA138}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |

||

| title = "Nicotine psychopharmacology", research contributions to United States and global tobacco regulation: A look back and a look forward |

| title = "Nicotine psychopharmacology", research contributions to United States and global tobacco regulation: A look back and a look forward |

||

| journal = Psychopharmacology |

| journal = Psychopharmacology |

||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

| last2 = Zeller |

| last2 = Zeller |

||

| first2 = M |

| first2 = M |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| author1 = Henningfield, Jack E |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| title = Über das Nicotin |

| title = Über das Nicotin |

||

| author = Melsens |

| author = Melsens |

||

| journal = |

| journal = Journal für Praktische Chemie |

||

| volume = 32 |

| volume = 32 |

||

| issue = 1 |

| issue = 1 |

||

| pages = |

| pages = 372–7 |

||

| year = 1844 |

| year = 1844 |

||

| url = |

| url = |

||

| Line 149: | Line 148: | ||

The amount of nicotine absorbed by the body from smoking depends on many factors, including the types of tobacco, whether the smoke is inhaled, and whether a filter is used. For [[chewing tobacco]], [[dipping tobacco]], [[snus]] and [[Snuff (tobacco)|snuff]], which are held in the mouth between the lip and gum, or taken in the nose, the amount released into the body tends to be much greater than smoked tobacco.{{Clarify|Say how much for each?|date=July 2011}}{{Citation needed|date=October 2011}} Nicotine is [[metabolized]] in the [[liver]] by [[cytochrome P450]] enzymes (mostly [[CYP2A6]], and also by [[CYP2B6]]). A major metabolite is [[cotinine]]. |

The amount of nicotine absorbed by the body from smoking depends on many factors, including the types of tobacco, whether the smoke is inhaled, and whether a filter is used. For [[chewing tobacco]], [[dipping tobacco]], [[snus]] and [[Snuff (tobacco)|snuff]], which are held in the mouth between the lip and gum, or taken in the nose, the amount released into the body tends to be much greater than smoked tobacco.{{Clarify|Say how much for each?|date=July 2011}}{{Citation needed|date=October 2011}} Nicotine is [[metabolized]] in the [[liver]] by [[cytochrome P450]] enzymes (mostly [[CYP2A6]], and also by [[CYP2B6]]). A major metabolite is [[cotinine]]. |

||

Other primary metabolites include nicotine ''N'''-oxide, nornicotine, nicotine isomethonium ion, 2-hydroxynicotine and nicotine glucuronide.<ref name=hukkanen2005>{{cite journal|last=Hukkanen J, Jacob P 3rd, Benowitz NL. |title=Metabolism and Disposition Kinetics of Nicotine|journal=Pharmacol Rev. |year= 2005 |month= March |volume=57|issue=1|pages=79–115|pmid=15734728|url=http://pharmrev.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/full/57/1/79|doi=10.1124/pr.57.1.3|first1=J|last2=Jacob P|first2=3rd|last3=Benowitz|first3=NL}}</ref> Under some conditions, other substances may be formed such as [[myosmine]].<ref>http://chromatographyonline.findanalytichem.com/lcgc/News/The-danger-of-third-hand-smoke/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/713385</ref> |

Other primary metabolites include nicotine ''N'''-oxide, nornicotine, nicotine isomethonium ion, 2-hydroxynicotine and nicotine glucuronide.<ref name=hukkanen2005>{{cite journal|last=Hukkanen J, Jacob P 3rd, Benowitz NL. |title=Metabolism and Disposition Kinetics of Nicotine|journal=Pharmacol Rev. |year= 2005 |month= March |volume=57|issue=1|pages=79–115|pmid=15734728|url=http://pharmrev.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/full/57/1/79|doi=10.1124/pr.57.1.3|first1=J|last2=Jacob P|first2=3rd|last3=Benowitz|first3=NL}}</ref> Under some conditions, other substances may be formed such as [[myosmine]].<ref>{{cite journal |title=The danger of third-hand smoke |journal=Chromatography Online |volume=7 |issue=3 |date=22 February 2011 |url=http://chromatographyonline.findanalytichem.com/lcgc/News/The-danger-of-third-hand-smoke/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/713385}}</ref> |

||

[[Glucuronidation]] and oxidative metabolism of nicotine to cotinine are both inhibited by [[menthol]], an additive to [[Menthol cigarettes|mentholated cigarettes]], thus increasing the half-life of nicotine ''in vivo''.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Benowitz NL, Herrera B, Jacob P 3rd.|year=2004|title=Mentholated Cigarette Smoking Inhibits Nicotine Metabolism |journal=J Pharmacol Exp Ther|volume=310|issue=3|pages=1208–15|pmid=15084646|url=http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/310/3/1208|doi=10.1124/jpet.104.066902|first1=NL|last2=Herrera|first2=B|last3=Jacob P|first3=3rd}}</ref> |

[[Glucuronidation]] and oxidative metabolism of nicotine to cotinine are both inhibited by [[menthol]], an additive to [[Menthol cigarettes|mentholated cigarettes]], thus increasing the half-life of nicotine ''in vivo''.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Benowitz NL, Herrera B, Jacob P 3rd.|year=2004|title=Mentholated Cigarette Smoking Inhibits Nicotine Metabolism |journal=J Pharmacol Exp Ther|volume=310|issue=3|pages=1208–15|pmid=15084646|url=http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/310/3/1208|doi=10.1124/jpet.104.066902|first1=NL|last2=Herrera|first2=B|last3=Jacob P|first3=3rd}}</ref> |

||

| Line 156: | Line 155: | ||

==== Medical detection ==== |

==== Medical detection ==== |

||

Nicotine can be quantified in blood, plasma, or urine to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning or to facilitate a medicolegal death investigation. Urinary or salivary cotinine concentrations are frequently measured for the purposes of pre-employment and health insurance medical screening programs. Careful interpretation of results is important, since passive exposure to cigarette smoke can result in significant accumulation of nicotine, followed by the appearance of its metabolites in various body fluids.<ref>Benowitz NL, Hukkanen J, Jacob P |

Nicotine can be quantified in blood, plasma, or urine to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning or to facilitate a medicolegal death investigation. Urinary or salivary cotinine concentrations are frequently measured for the purposes of pre-employment and health insurance medical screening programs. Careful interpretation of results is important, since passive exposure to cigarette smoke can result in significant accumulation of nicotine, followed by the appearance of its metabolites in various body fluids.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Benowitz NL, Hukkanen J, Jacob P |title=Nicotine chemistry, metabolism, kinetics and biomarkers |journal=Handb Exp Pharmacol |issue=192 |pages=29–60 |year=2009 |pmid=19184645 |pmc=2953858 |doi=10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_2 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |first=Randall Clint |last=Baselt |title=Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man |year=2008 |publisher=Biomedical Publications |isbn=978-0-9626523-7-0 |edition=8th |pages=1103–7}}</ref> Nicotine use is not regulated in competitive sports programs, yet the drug has been shown to have a significant beneficial effect on athletic endurance in subjects who have not used nicotine before.<ref>{{cite journal |author = Mündel, T. and Jones, D. A.|title = Effect of transdermal nicotine administration on exercise endurance in men|journal = Exp Physiol|year = 2006|volume = 91 |pmid = 16627574 |issue = 4| pages = 705–713 |doi = 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.033373 }}</ref> |

||

===Pharmacodynamics=== |

===Pharmacodynamics=== |

||

| Line 164: | Line 163: | ||

[[File:NicotineDopaminergic WP1602.png|thumb|right|Effect of nicotine on dopaminergic neurons.]] |

[[File:NicotineDopaminergic WP1602.png|thumb|right|Effect of nicotine on dopaminergic neurons.]] |

||

By binding to [[nicotinic acetylcholine receptor]]s, nicotine increases the levels of several [[neurotransmitter]]s - acting as a sort of "volume control". It is thought that increased levels of [[dopamine]] in the [[reward circuit]]s of the [[Human brain|brain]] are responsible for the apparent [[euphoria (emotion)|euphoria]] and [[Relaxation (psychology)|relaxation]], and addiction caused by nicotine consumption. Nicotine has a higher affinity for [[acetylcholine]] receptors in the brain than those in [[skeletal muscle]], though at toxic doses it can induce contractions and respiratory paralysis.<ref>Katzung, Bertram G. |

By binding to [[nicotinic acetylcholine receptor]]s, nicotine increases the levels of several [[neurotransmitter]]s - acting as a sort of "volume control". It is thought that increased levels of [[dopamine]] in the [[reward circuit]]s of the [[Human brain|brain]] are responsible for the apparent [[euphoria (emotion)|euphoria]] and [[Relaxation (psychology)|relaxation]], and addiction caused by nicotine consumption. Nicotine has a higher affinity for [[acetylcholine]] receptors in the brain than those in [[skeletal muscle]], though at toxic doses it can induce contractions and respiratory paralysis.<ref>{{cite book |author=Katzung, Bertram G. |title=Basic and Clinical Pharmacology |publisher=McGraw-Hill Medical |location=New York |year=2006 |pages=99–105 }}</ref> Nicotine's selectivity is thought to be due to a particular amino acid difference on these receptor subtypes.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Xiu | first1 = Xinan | last2 = Puskar | first2 = Nyssa L. | last3 = Shanata | first3 = Jai A. P. | last4 = Lester | first4 = Henry A. | last5 = Dougherty | first5 = Dennis A. | year = 2009 | title = Nicotine Binding to Brain Receptors Requires a Strong Cation-π Interaction | journal = Nature | volume = 458 | issue = 7237| pages = 534–7 | pmid = 19252481 | pmc = 2755585 | doi=10.1038/nature07768}}</ref> |

||

Tobacco smoke contains [[anabasine]], [[anatabine]], and [[nornicotine]].{{Citation needed|date=January 2012}} It also contains the [[monoamine oxidase inhibitor]]s [[Harmala alkaloid|harman]] and norharman.<ref name=pmid15582589>{{cite journal |author=Herraiz T, Chaparro C |title=Human monoamine oxidase is inhibited by tobacco smoke: beta-carboline alkaloids act as potent and reversible inhibitors |journal=Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. |volume=326 |issue=2 |pages=378–86 |year=2005 |pmid=15582589 |doi=10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.033 }}</ref> These [[beta-carboline]] compounds significantly decrease [[MAO]] activity in smokers.<ref name="pmid15582589"/><ref name="pmid9549600">{{cite journal |author=Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, ''et al.'' |title=Neuropharmacological actions of cigarette smoke: brain monoamine oxidase B (MAO B) inhibition |journal=J Addict Dis |volume=17 |issue=1 |pages=23–34 |year=1998 |pmid=9549600 |doi= 10.1300/J069v17n01_03 }}</ref> MAO [[enzyme]]s break down [[monoamine|monoaminergic neurotransmitters]] such as [[dopamine]], [[norepinephrine]], and [[serotonin]]. It is thought that the powerful interaction between the MAOI's and the nicotine is responsible for most of the addictive properties of tobacco smoking.<ref name="pmid14592678">{{cite journal |author=Villégier AS, Blanc G, Glowinski J, Tassin JP |title=Transient behavioral sensitization to nicotine becomes long-lasting with monoamine oxidases inhibitors |journal=Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. |volume=76 |issue=2 |pages=267–74 |year=2003 |month=September |pmid=14592678 |doi= 10.1016/S0091-3057(03)00223-5 |

Tobacco smoke contains [[anabasine]], [[anatabine]], and [[nornicotine]].{{Citation needed|date=January 2012}} It also contains the [[monoamine oxidase inhibitor]]s [[Harmala alkaloid|harman]] and norharman.<ref name=pmid15582589>{{cite journal |author=Herraiz T, Chaparro C |title=Human monoamine oxidase is inhibited by tobacco smoke: beta-carboline alkaloids act as potent and reversible inhibitors |journal=Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. |volume=326 |issue=2 |pages=378–86 |year=2005 |pmid=15582589 |doi=10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.033 }}</ref> These [[beta-carboline]] compounds significantly decrease [[MAO]] activity in smokers.<ref name="pmid15582589"/><ref name="pmid9549600">{{cite journal |author=Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, ''et al.'' |title=Neuropharmacological actions of cigarette smoke: brain monoamine oxidase B (MAO B) inhibition |journal=J Addict Dis |volume=17 |issue=1 |pages=23–34 |year=1998 |pmid=9549600 |doi= 10.1300/J069v17n01_03 }}</ref> MAO [[enzyme]]s break down [[monoamine|monoaminergic neurotransmitters]] such as [[dopamine]], [[norepinephrine]], and [[serotonin]]. It is thought that the powerful interaction between the MAOI's and the nicotine is responsible for most of the addictive properties of tobacco smoking.<ref name="pmid14592678">{{cite journal |author=Villégier AS, Blanc G, Glowinski J, Tassin JP |title=Transient behavioral sensitization to nicotine becomes long-lasting with monoamine oxidases inhibitors |journal=Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. |volume=76 |issue=2 |pages=267–74 |year=2003 |month=September |pmid=14592678 |doi= 10.1016/S0091-3057(03)00223-5}}</ref> The addition of five minor tobacco alkaloids increases nicotine-induced hyperactivity, sensitization and intravenous self-administration in rats.<ref>{{cite journal | year = 2006| title = Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors Allow Locomotor and Rewarding Responses to Nicotine | url =http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=6382912 | journal = Nature | doi=10.1038/sj.npp.1300987 | volume=31 | issue=8 | last1 = Villégier | first1 = Anne-Sophie | last2 = Salomon | first2 = Lucas | last3 = Granon | first3 = Sylvie | last4 = Changeux | first4 = Jean-Pierre | last5 = Belluzzi | first5 = James D | last6 = Leslie | first6 = Frances M | last7 = Tassin | first7 = Jean-Pol | pages = 1704}}</ref> |

||

Chronic nicotine exposure via tobacco smoking [[up-regulation|up-regulates]] [[Alpha-4 beta-2 nicotinic receptor|alpha4beta2]]* nAChR in [[cerebellum]] and [[brainstem]] regions<ref name="pmid17997038">{{cite journal |author=Wüllner U, Gündisch D, Herzog H, ''et al.'' |title=Smoking upregulates alpha4beta2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the human brain |journal=Neurosci. Lett. |volume=430 |issue=1 |pages=34–7 |year=2008 |pmid=17997038 |doi=10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.011 |

Chronic nicotine exposure via tobacco smoking [[up-regulation|up-regulates]] [[Alpha-4 beta-2 nicotinic receptor|alpha4beta2]]* nAChR in [[cerebellum]] and [[brainstem]] regions<ref name="pmid17997038">{{cite journal |author=Wüllner U, Gündisch D, Herzog H, ''et al.'' |title=Smoking upregulates alpha4beta2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the human brain |journal=Neurosci. Lett. |volume=430 |issue=1 |pages=34–7 |year=2008 |pmid=17997038 |doi=10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.011 |last12=Schmaljohann |first12=J}}</ref><ref name="pmid18174175">{{cite journal |author=Walsh H, Govind AP, Mastro R, ''et al.'' |title=Up-regulation of nicotinic receptors by nicotine varies with receptor subtype |journal=J. Biol. Chem. |volume=283 |issue=10 |pages=6022–32 |year=2008 |pmid=18174175 |doi=10.1074/jbc.M703432200 }}</ref> but not [[Habenula|habenulopeduncular]] structures.<ref name="pmid14560040">{{cite journal |author=Nguyen HN, Rasmussen BA, Perry DC |title=Subtype-selective up-regulation by chronic nicotine of high-affinity nicotinic receptors in rat brain demonstrated by receptor autoradiography |journal=J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. |volume=307 |issue=3 |pages=1090–7 |year=2003 |pmid=14560040 |doi=10.1124/jpet.103.056408 }}</ref> Alpha4beta2 and alpha6beta2 receptors, present in the [[ventral tegmental area]], play a crucial role in mediating the reinforcement effects of nicotine.<ref name="pmid19020025">{{cite journal |author=Pons S, Fattore L, Cossu G, ''et al.'' |title=Crucial role of α4 and α6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits from ventral tegmental area in systemic nicotine self-administration |journal=J. Neurosci. |volume=28 |issue=47 |pages=12318–27 |year=2008 |month=November |pmid=19020025 |doi=10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3918-08.2008 |pmc=2819191}}</ref> |

||

==== In the sympathetic nervous system ==== |

==== In the sympathetic nervous system ==== |

||

Nicotine also activates the [[sympathetic nervous system]],<ref>{{cite journal |author=Yoshida T, Sakane N, Umekawa T, Kondo M |title=Effect of nicotine on sympathetic nervous system activity of mice subjected to immobilization stress |journal=Physiol Behav. |volume=55 |issue=1 |pages=53–7 |year=1994 |month=Jan |pmid=8140174 |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0031-9384(94)90009-4 |doi=10.1016/0031-9384(94)90009-4}}</ref> acting via [[splanchnic nerves]] to the adrenal medulla, stimulates the release of epinephrine. Acetylcholine released by preganglionic sympathetic fibers of these nerves acts on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, causing the release of epinephrine (and norepinephrine) into the [[bloodstream]]. Nicotine also has an affinity for [[melanin]]-containing tissues due to its precursor function in melanin synthesis or due to the irreversible binding of melanin and nicotine. This has been suggested to underlie the increased [[nicotine dependence]] and lower [[smoking cessation]] rates in darker pigmented individuals. However, further research is warranted before a definite conclusive link can be inferred.<ref>King G, Yerger VB, Whembolua GL, Bendel RB, Kittles R, Moolchan ET |

Nicotine also activates the [[sympathetic nervous system]],<ref>{{cite journal |author=Yoshida T, Sakane N, Umekawa T, Kondo M |title=Effect of nicotine on sympathetic nervous system activity of mice subjected to immobilization stress |journal=Physiol Behav. |volume=55 |issue=1 |pages=53–7 |year=1994 |month=Jan |pmid=8140174 |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0031-9384(94)90009-4 |doi=10.1016/0031-9384(94)90009-4}}</ref> acting via [[splanchnic nerves]] to the adrenal medulla, stimulates the release of epinephrine. Acetylcholine released by preganglionic sympathetic fibers of these nerves acts on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, causing the release of epinephrine (and norepinephrine) into the [[bloodstream]]. Nicotine also has an affinity for [[melanin]]-containing tissues due to its precursor function in melanin synthesis or due to the irreversible binding of melanin and nicotine. This has been suggested to underlie the increased [[nicotine dependence]] and lower [[smoking cessation]] rates in darker pigmented individuals. However, further research is warranted before a definite conclusive link can be inferred.<ref>{{cite journal |author=King G, Yerger VB, Whembolua GL, Bendel RB, Kittles R, Moolchan ET |title=Link between facultative melanin and tobacco use among African Americans |journal=Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. |volume=92 |issue=4 |pages=589–96 |year=2009 |month=June |pmid=19268687 |doi=10.1016/j.pbb.2009.02.011 |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0091-3057(09)00076-8}}</ref> |

||

[[File:NicotineChromaffinCells WP1603.png|thumb|right|Effect of nicotine on chromaffin cells.]] |

[[File:NicotineChromaffinCells WP1603.png|thumb|right|Effect of nicotine on chromaffin cells.]] |

||

| Line 178: | Line 177: | ||

By binding to [[ganglion type nicotinic receptor]]s in the adrenal medulla nicotine increases flow of [[adrenaline]] (epinephrine), a stimulating [[hormone]] and neurotransmitter. By binding to the receptors, it causes cell depolarization and an influx of [[calcium]] through voltage-gated calcium channels. Calcium triggers the [[exocytosis]] of [[Chromaffin cell|chromaffin granules]] and thus the release of [[epinephrine]] (and norepinephrine) into the [[bloodstream]]. The release of [[epinephrine]] (adrenaline) causes an increase in [[heart rate]], [[blood pressure]] and [[breathing|respiration]], as well as higher [[blood glucose]] levels.<ref name="Marieb" >{{cite book | author = Elaine N. Marieb and Katja Hoehn | title = Human Anatomy & Physiology (7th Ed.) | publisher = Pearson | pages = ? | year = 2007 | isbn = 0-8053-5909-5}}</ref> |

By binding to [[ganglion type nicotinic receptor]]s in the adrenal medulla nicotine increases flow of [[adrenaline]] (epinephrine), a stimulating [[hormone]] and neurotransmitter. By binding to the receptors, it causes cell depolarization and an influx of [[calcium]] through voltage-gated calcium channels. Calcium triggers the [[exocytosis]] of [[Chromaffin cell|chromaffin granules]] and thus the release of [[epinephrine]] (and norepinephrine) into the [[bloodstream]]. The release of [[epinephrine]] (adrenaline) causes an increase in [[heart rate]], [[blood pressure]] and [[breathing|respiration]], as well as higher [[blood glucose]] levels.<ref name="Marieb" >{{cite book | author = Elaine N. Marieb and Katja Hoehn | title = Human Anatomy & Physiology (7th Ed.) | publisher = Pearson | pages = ? | year = 2007 | isbn = 0-8053-5909-5}}</ref> |

||

Nicotine is the natural product of tobacco, having a half-life of 1 to 2 hours. [[Cotinine]] is an active metabolite of nicotine that remains in the blood for 18 to 20 hours, making it easier to analyze due to its longer half-life.<ref> |

Nicotine is the natural product of tobacco, having a half-life of 1 to 2 hours. [[Cotinine]] is an active metabolite of nicotine that remains in the blood for 18 to 20 hours, making it easier to analyze due to its longer half-life.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Detection of Cotinine in Blood Plasma by HPLC MS/MS |journal=MIT Undergraduate Research Journal |volume=8 |date=Spring 2003 |publisher=Massachusetts Institute of Technology |url=http://web.mit.edu/murj/www/v08/v08-Reports/v08-r2.pdf |format=PDF}}</ref> |

||

==Psychoactive effects== |

==Psychoactive effects== |

||

Nicotine's [[Mood (psychology)|mood]]-altering effects are different by report: in particular it is both a stimulant and a relaxant.<ref>[http://www.ti.ubc.ca/pages/letter21.htm ''Effective Clinical Tobacco Intervention''], Therapeutics Letter, issue 21, September–October 1997, University of British Columbia</ref> First causing a release of [[glucose]] from the liver and [[epinephrine]] (adrenaline) from the [[adrenal medulla]], it causes [[stimulation]]. Users report feelings of [[Relaxation (psychology)|relaxation]], sharpness, [[calmness]], and [[alertness]].<ref> |

Nicotine's [[Mood (psychology)|mood]]-altering effects are different by report: in particular it is both a stimulant and a relaxant.<ref>[http://www.ti.ubc.ca/pages/letter21.htm ''Effective Clinical Tobacco Intervention''], Therapeutics Letter, issue 21, September–October 1997, University of British Columbia</ref> First causing a release of [[glucose]] from the liver and [[epinephrine]] (adrenaline) from the [[adrenal medulla]], it causes [[stimulation]]. Users report feelings of [[Relaxation (psychology)|relaxation]], sharpness, [[calmness]], and [[alertness]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Lagrue, Gilbert; Lebargy, François; Cormier, Anne |title=From nicotinic receptors to smoking dependence: therapeutic prospects |journal=Alcoologie et Addictologie |volume=23 |issue=2S |pages=39S–42 |date=Juin 2001 }}</ref> Like any stimulant, it may very rarely cause the often catastrophically uncomfortable [[neuropsychiatric]] effect of [[akathisia]]. By reducing the [[appetite]] and raising the [[metabolism]], some smokers may [[weight loss|lose weight]] as a consequence.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Orsini, Jean-Claude |title=Dependence on tobacco smoking and brain systems controlling glycemia and appetite |journal=Alcoologie et Addictologie |volume=23 |issue=2S |pages=28S–36S |date=Juin 2001 }}</ref><ref>[http://uninews.unimelb.edu.au/articleid_1898.html Smokers lose their appetite : Media Releases : News : The University of Melbourne<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

When a [[cigarette]] is smoked, nicotine-rich blood passes from the [[Human lung|lung]]s to the [[Human brain|brain]] within seven seconds and immediately stimulates the release of many chemical messengers including [[acetylcholine]], [[norepinephrine]], [[epinephrine]], [[vasopressin]], [[arginine]], [[dopamine]], [[autocrine agents]], and [[beta-endorphin]].<ref>''[http://www.bodybuilding.com/fun/par16.htm Chemically Correct: Nicotine]'', Andrew Novick</ref> This release of neurotransmitters and hormones is responsible for most of nicotine's effects. Nicotine appears to enhance [[attention|concentration]]<ref name="rusted">{{cite journal| |

When a [[cigarette]] is smoked, nicotine-rich blood passes from the [[Human lung|lung]]s to the [[Human brain|brain]] within seven seconds and immediately stimulates the release of many chemical messengers including [[acetylcholine]], [[norepinephrine]], [[epinephrine]], [[vasopressin]], [[arginine]], [[dopamine]], [[autocrine agents]], and [[beta-endorphin]].<ref>''[http://www.bodybuilding.com/fun/par16.htm Chemically Correct: Nicotine]'', Andrew Novick</ref> This release of neurotransmitters and hormones is responsible for most of nicotine's effects. Nicotine appears to enhance [[attention|concentration]]<ref name="rusted">{{cite journal |author=Rusted J, Graupner L, O'Connell N, Nicholls C |title=Does nicotine improve cognitive function? |journal=Psychopharmacology (Berl.) |volume=115 |issue=4 |pages=547–9 |year=1994 |month=August |pmid=7871101 |url=http://www.springerlink.com/content/75034q53031260j8/?p=afde608485604678839ab0e950be77f9&pi=0}}</ref> and memory due to the increase of [[acetylcholine]]. It also appears to enhance [[alertness]] due to the increases of [[acetylcholine]] and [[norepinephrine]]. [[Arousal]] is increased by the increase of [[norepinephrine]]. [[Pain]] is reduced by the increases of [[acetylcholine]] and beta-endorphin. [[Anxiety]] is reduced by the increase of [[beta-endorphin]]. Nicotine also extends the duration of positive effects of dopamine<ref>{{cite journal |author=Easton, John |title=Nicotine extends duration of pleasant effects of dopamine |journal=The University of Chicago Chronicle |volume=21 |issue=12 |date=March 28, 2002 |url=http://chronicle.uchicago.edu/020328/nicotine.shtml}}</ref> and increases sensitivity in brain reward systems.<ref name=Kenny>{{cite journal |author=Kenny PJ, Markou A |title=Nicotine self-administration acutely activates brain reward systems and induces a long-lasting increase in reward sensitivity |journal=Neuropsychopharmacology |volume=31 |issue=6 |pages=1203–11 |year=2006 |month=Jun |pmid=16192981 |doi=10.1038/sj.npp.1300905 |url=http://www.nature.com/npp/journal/v31/n6/full/1300905a.html}}</ref> Most cigarettes (in the smoke inhaled) contain 1 to 3 milligrams of nicotine.<ref>[http://www.erowid.org/chemicals/nicotine/nicotine_dose.shtml Erowid Nicotine Vault : Dosage<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

Research suggests that, when smokers wish to achieve a stimulating effect, they take short quick puffs, which produce a low level of blood nicotine.<ref>{{cite book |

Research suggests that, when smokers wish to achieve a stimulating effect, they take short quick puffs, which produce a low level of blood nicotine.<ref>{{cite book |

||

| Line 196: | Line 195: | ||

}}</ref> This stimulates [[action potential|nerve transmission]]. When they wish to relax, they take deep puffs, which produce a high level of blood nicotine, which depresses the passage of [[nerve impulses]], producing a mild sedative effect. At low doses, nicotine potently enhances the actions of [[norepinephrine]] and [[dopamine]] in the brain, causing a drug effect typical of those of [[psychostimulants]]. At higher doses, nicotine enhances the effect of [[serotonin]] and [[opiate]] activity, producing a calming, [[analgesic|pain-killing]] effect. Nicotine is unique in comparison to most [[drug]]s, as its profile changes from [[stimulant]] to [[sedative]]/[[pain killer]] in increasing [[Dose (biochemistry)|dosage]]s and use. |

}}</ref> This stimulates [[action potential|nerve transmission]]. When they wish to relax, they take deep puffs, which produce a high level of blood nicotine, which depresses the passage of [[nerve impulses]], producing a mild sedative effect. At low doses, nicotine potently enhances the actions of [[norepinephrine]] and [[dopamine]] in the brain, causing a drug effect typical of those of [[psychostimulants]]. At higher doses, nicotine enhances the effect of [[serotonin]] and [[opiate]] activity, producing a calming, [[analgesic|pain-killing]] effect. Nicotine is unique in comparison to most [[drug]]s, as its profile changes from [[stimulant]] to [[sedative]]/[[pain killer]] in increasing [[Dose (biochemistry)|dosage]]s and use. |

||

Technically, nicotine is not significantly addictive, as nicotine administered alone does not produce significant reinforcing properties.<ref name="pmid16177026">{{cite journal |author=Guillem K, Vouillac C, Azar MR, ''et al.'' |title=Monoamine oxidase inhibition dramatically increases the motivation to self-administer nicotine in rats |journal=J. Neurosci. |volume=25 |issue=38 |pages=8593–600 |year=2005 |month=September |pmid=16177026 |doi=10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2139-05.2005 |

Technically, nicotine is not significantly addictive, as nicotine administered alone does not produce significant reinforcing properties.<ref name="pmid16177026">{{cite journal |author=Guillem K, Vouillac C, Azar MR, ''et al.'' |title=Monoamine oxidase inhibition dramatically increases the motivation to self-administer nicotine in rats |journal=J. Neurosci. |volume=25 |issue=38 |pages=8593–600 |year=2005 |month=September |pmid=16177026 |doi=10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2139-05.2005 }}</ref> However, after coadministration with an [[MAOI]], such as those found in tobacco, nicotine produces significant behavioral sensitization, a measure of addiction potential. This is similar in effect to [[amphetamine]].<ref name="pmid14592678"/> |

||

[[Nicotine gum]], usually in 2-mg or 4-mg doses, and [[nicotine patches]] are available, as well as [[smokeless tobacco]], nicotine lozenges and [[electronic cigarettes]]. |

[[Nicotine gum]], usually in 2-mg or 4-mg doses, and [[nicotine patches]] are available, as well as [[smokeless tobacco]], nicotine lozenges and [[electronic cigarettes]]. |

||

[[Image:Nicoderm.JPG||thumb|right|A 21 mg patch applied to the left arm. The [[Cochrane Collaboration]] finds that NRT increases a quitter's chance of success by 50 to 70%.<ref name=CD000146>{{cite |

[[Image:Nicoderm.JPG||thumb|right|A 21 mg patch applied to the left arm. The [[Cochrane Collaboration]] finds that NRT increases a quitter's chance of success by 50 to 70%.<ref name=CD000146>{{cite journal |author=Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, Mant D, Lancaster T |title=Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation |journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |issue=1 |pages=CD000146 |year=2008 |pmid=18253970 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub3 |url=http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab000146.html}}</ref> But in 1990, researchers found that 93% of users returned to smoking within six months.<ref>{{cite news|author=Millstone, Ken|title=Nixing the patch: Smokers quit cold turkey|url=http://jscms.jrn.columbia.edu/cns/2007-02-13/millstone-coldturkeyquitters.html|date=February 13, 2007|publisher=Columbia.edu News Service|accessdate=May 23, 2010}}</ref>]] |

||

==Dependence and withdrawal== |

==Dependence and withdrawal== |

||

{{refimprove|date=April 2012}} |

{{refimprove|date=April 2012}} |

||

{{See also|Smoking cessation}} |

{{See also|Smoking cessation}} |

||

Modern [[research]] shows that nicotine acts on the brain to produce a number of effects. Specifically, research examining its addictive nature has been found to show that nicotine activates the [[mesolimbic pathway]] ("reward system") —the circuitry within the brain that regulates feelings of pleasure and euphoria.<ref> |

Modern [[research]] shows that nicotine acts on the brain to produce a number of effects. Specifically, research examining its addictive nature has been found to show that nicotine activates the [[mesolimbic pathway]] ("reward system") —the circuitry within the brain that regulates feelings of pleasure and euphoria.<ref>{{cite book |author=National Institute on Drug Abuse |chapter=Extent, Impact, Delivery, and Addictiveness |chapterurl=http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/tobacco-addiction/what-are-extent-impact-tobacco-use |title=Tobacco Addiction |publisher=National Institutes of Health |location=Bethesda MA |year=June 2009 |series=NIDA Report Research Series |id=09-4342 |url=http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/tobacco-addiction}}</ref> |

||

[[Dopamine]] is one of the key [[neurotransmitters]] actively involved in the brain. Research shows that by increasing the levels of dopamine within the reward circuits in the brain, nicotine acts as a chemical with intense addictive qualities. In many studies it has been shown to be more addictive than [[cocaine]] and [[heroin]].<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.nytimes.com/1994/08/02/science/is-nicotine-addictive-it-depends-on-whose-criteria-you-use.html | work=The New York Times | first=Philip J. | last=Hilts | title=Is Nicotine Addictive? It Depends on Whose Criteria You Use | date=1994-08-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.nytimes.com/1987/03/29/magazine/nicotine-harder-to-kickthan-heroin.html | work=The New York Times | first=Sandra | last=Blakeslee | title= |

[[Dopamine]] is one of the key [[neurotransmitters]] actively involved in the brain. Research shows that by increasing the levels of dopamine within the reward circuits in the brain, nicotine acts as a chemical with intense addictive qualities. In many studies it has been shown to be more addictive than [[cocaine]] and [[heroin]].<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.nytimes.com/1994/08/02/science/is-nicotine-addictive-it-depends-on-whose-criteria-you-use.html | work=The New York Times | first=Philip J. | last=Hilts | title=Is Nicotine Addictive? It Depends on Whose Criteria You Use | date=1994-08-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.nytimes.com/1987/03/29/magazine/nicotine-harder-to-kickthan-heroin.html | work=The New York Times | first=Sandra | last=Blakeslee | title=Nicotine: Harder to Kick...Than Heroin | date=1987-03-29}}</ref><ref>http://www1.umn.edu/perio/tobacco/nicaddct.html</ref> Like other physically addictive drugs, [[nicotine withdrawal]] causes down-regulation of the production of dopamine and other stimulatory neurotransmitters as the brain attempts to compensate for artificial stimulation. As dopamine regulates the sensitivity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors decreases. To compensate for this compensatory mechanism, the brain in turn upregulates the number of receptors, [[convoluting]] its regulatory effects with compensatory mechanisms meant to counteract other compensatory mechanisms. An example is the increase in [[norepinephrine]], one of the successors to dopamine, which inhibit reuptake of the [[glutamate receptors]],<ref>{{cite journal |author=Yoshida T, Nishioka H, Nakamura Y, Kondo M |title=Reduced norepinephrine turnover in mice with monosodium glutamate-induced obesity |journal=Metab. Clin. Exp. |volume=33 |issue=11 |pages=1060–3 |year=1984 |month=November |pmid=6493048 |doi=10.1016/0026-0495(84)90238-5 |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0026-0495(84)90238-5}}</ref> in charge of memory and cognition. The net effect is an increase in reward pathway sensitivity, the opposite of other addictive drugs such as cocaine and heroin, which reduce reward pathway sensitivity.<ref name=Kenny/> This neuronal brain alteration can persist for months after administration ceases. |

||

A study found that nicotine exposure in adolescent mice retards the growth of the dopamine system, thus increasing the risk of substance abuse during adolescence.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Nolley EP, Kelley BM |title=Adolescent reward system perseveration due to nicotine: studies with methylphenidate |journal=Neurotoxicol Teratol |volume=29 |issue=1 |pages=47–56 |year=2007 |pmid=17129706 |doi=10.1016/j.ntt.2006.09.026 }}</ref> |

A study found that nicotine exposure in adolescent mice retards the growth of the dopamine system, thus increasing the risk of substance abuse during adolescence.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Nolley EP, Kelley BM |title=Adolescent reward system perseveration due to nicotine: studies with methylphenidate |journal=Neurotoxicol Teratol |volume=29 |issue=1 |pages=47–56 |year=2007 |pmid=17129706 |doi=10.1016/j.ntt.2006.09.026 }}</ref> |

||

| Line 216: | Line 215: | ||

These include attaching the nicotine molecule to a [[hapten]] such as [[Keyhole limpet hemocyanin]] or a safe modified bacterial toxin to elicit an active immune response. Often it is added with [[bovine serum albumin]]. |

These include attaching the nicotine molecule to a [[hapten]] such as [[Keyhole limpet hemocyanin]] or a safe modified bacterial toxin to elicit an active immune response. Often it is added with [[bovine serum albumin]]. |

||

Additionally, because of concerns with the unique immune systems of individuals being liable to produce antibodies against endogenous hormones and over the counter drugs, [[monoclonal antibodies]] have been developed for short term passive immune protection. They have half-lives varying from hours to weeks. Their half-lives depend on their ability to resist degradation from [[pinocytosis]] by [[epithelial cells]].<ref> |

Additionally, because of concerns with the unique immune systems of individuals being liable to produce antibodies against endogenous hormones and over the counter drugs, [[monoclonal antibodies]] have been developed for short term passive immune protection. They have half-lives varying from hours to weeks. Their half-lives depend on their ability to resist degradation from [[pinocytosis]] by [[epithelial cells]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Peterson EC, Owens SM |title=Designing immunotherapies to thwart drug abuse |journal=Mol. Interv. |volume=9 |issue=3 |pages=119–24 |year=2009 |month=June |pmid=19592672 |pmc=2743871 |doi=10.1124/mi.9.3.5 }}</ref> {{Citation needed|date=October 2011}} |

||

==Toxicology== |

==Toxicology== |

||

| Line 228: | Line 227: | ||

The {{LD50}} of nicotine is 50 mg/kg for [[rat]]s and 3 mg/kg for [[mouse|mice]]. 30–60 mg (0.5-1.0 mg/kg) can be a lethal dosage for adult humans.<ref name=inchem /><ref>{{cite journal |author=Okamoto M, Kita T, Okuda H, Tanaka T, Nakashima T |title=Effects of aging on acute toxicity of nicotine in rats |journal=Pharmacol Toxicol. |volume=75 |issue=1 |pages=1–6 |year=1994 |month=Jul |pmid=7971729 |doi=10.1111/j.1600-0773.1994.tb00316.x}}</ref> Nicotine therefore has a high [[toxicity]] in comparison to many other alkaloids such as [[cocaine]], which has an LD<sub>50</sub> of 95.1 mg/kg when administered to mice. It is unlikely that a person would overdose on nicotine through smoking alone, although overdose can occur through combined use of nicotine patches or nicotine gum and cigarettes at the same time.<ref name=overdose /> Spilling a high concentration of nicotine onto the skin can cause intoxication or even death, since nicotine readily passes into the bloodstream following dermal contact.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Lockhart LP |title=Nicotine poisoning |journal=Br Med J |volume=1 |issue= 3762|pages=246–7 |year=1933 |doi=10.1136/bmj.1.3762.246-c}}</ref> |

The {{LD50}} of nicotine is 50 mg/kg for [[rat]]s and 3 mg/kg for [[mouse|mice]]. 30–60 mg (0.5-1.0 mg/kg) can be a lethal dosage for adult humans.<ref name=inchem /><ref>{{cite journal |author=Okamoto M, Kita T, Okuda H, Tanaka T, Nakashima T |title=Effects of aging on acute toxicity of nicotine in rats |journal=Pharmacol Toxicol. |volume=75 |issue=1 |pages=1–6 |year=1994 |month=Jul |pmid=7971729 |doi=10.1111/j.1600-0773.1994.tb00316.x}}</ref> Nicotine therefore has a high [[toxicity]] in comparison to many other alkaloids such as [[cocaine]], which has an LD<sub>50</sub> of 95.1 mg/kg when administered to mice. It is unlikely that a person would overdose on nicotine through smoking alone, although overdose can occur through combined use of nicotine patches or nicotine gum and cigarettes at the same time.<ref name=overdose /> Spilling a high concentration of nicotine onto the skin can cause intoxication or even death, since nicotine readily passes into the bloodstream following dermal contact.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Lockhart LP |title=Nicotine poisoning |journal=Br Med J |volume=1 |issue= 3762|pages=246–7 |year=1933 |doi=10.1136/bmj.1.3762.246-c}}</ref> |

||

Historically, nicotine has not been regarded as a [[carcinogen]] and the [[International Agency for Research on Cancer|IARC]] has not evaluated nicotine in its standalone form and assigned it to an official carcinogen group. While no epidemiological evidence supports that nicotine alone acts as a carcinogen in the formation of human cancer, research over the last decade has identified nicotine's [[carcinogenic]] potential in animal models and cell culture.<ref>Hecht SS |

Historically, nicotine has not been regarded as a [[carcinogen]] and the [[International Agency for Research on Cancer|IARC]] has not evaluated nicotine in its standalone form and assigned it to an official carcinogen group. While no epidemiological evidence supports that nicotine alone acts as a carcinogen in the formation of human cancer, research over the last decade has identified nicotine's [[carcinogenic]] potential in animal models and cell culture.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Hecht SS |title=Tobacco smoke carcinogens and lung cancer |journal=J. Natl. Cancer Inst. |volume=91 |issue=14 |pages=1194–210 |year=1999 |month=July |pmid=10413421 |url=http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10413421}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Wu WK, Cho CH |title=The pharmacological actions of nicotine on the gastrointestinal tract |journal=J. Pharmacol. Sci. |volume=94 |issue=4 |pages=348–58 |year=2004 |month=April |pmid=15107574 |url=http://joi.jlc.jst.go.jp/JST.JSTAGE/jphs/94.348?from=PubMed}}</ref> Nicotine has been noted to directly cause cancer through a number of different mechanisms such as the activation of [[MAP Kinases]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Chowdhury P, Udupa KB |title=Nicotine as a mitogenic stimulus for pancreatic acinar cell proliferation |journal=World J. Gastroenterol. |volume=12 |issue=46 |pages=7428–32 |year=2006 |month=December |pmid=17167829 |url=http://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i46/7428.htm}}</ref> Indirectly, nicotine increases [[Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor|cholinergic]] signalling (and [[adrenergic signalling]] in the case of colon cancer<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wong HP, Yu L, Lam EK, Tai EK, Wu WK, Cho CH |title=Nicotine promotes colon tumor growth and angiogenesis through beta-adrenergic activation |journal=Toxicol. Sci. |volume=97 |issue=2 |pages=279–87 |year=2007 |month=June |pmid=17369603 |doi=10.1093/toxsci/kfm060 |url=http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17369603}}</ref>), thereby impeding apoptosis ([[programmed cell death]]), promoting tumor growth, and activating [[growth factors]] and cellular [[mitogenic]] factors such as [[5-LOX]], and [[EGF]]. Nicotine also promotes cancer growth by stimulating [[angiogenesis]] and [[neovascularization]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Natori T, Sata M, Washida M, Hirata Y, Nagai R, Makuuchi M |title=Nicotine enhances neovascularization and promotes tumor growth |journal=Mol. Cells |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=143–6 |year=2003 |month=October |pmid=14651253 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Ye YN, Liu ES, Shin VY, Wu WK, Luo JC, Cho CH |title=Nicotine promoted colon cancer growth via epidermal growth factor receptor, c-Src, and 5-lipoxygenase-mediated signal pathway |journal=J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. |volume=308 |issue=1 |pages=66–72 |year=2004 |month=January |pmid=14569062 |doi=10.1124/jpet.103.058321 |url=http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14569062}}</ref> In one study, nicotine administered to mice with tumors caused increases in tumor size (twofold increase), [[metastasis]] (nine-fold increase), and tumor recurrence (threefold increase).<ref name="plosone.org">{{cite journal |author=Davis R, Rizwani W, Banerjee S, ''et al.'' |title=Nicotine promotes tumor growth and metastasis in mouse models of lung cancer |journal=PLoS ONE |volume=4 |issue=10 |pages=e7524 |year=2009 |pmid=19841737 |pmc=2759510 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0007524 |url=http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007524}}</ref> |

||

Though the [[Teratogenesis|teratogenic]] properties of nicotine may or may not yet have been adequately researched, women who use [[nicotine gum]] and patches during the early stages of pregnancy face an increased risk of having babies with birth defects, according to a study of around 77,000 pregnant women in Denmark. The study found that women who use nicotine-replacement therapy in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy have a 60% greater risk of having babies with birth defects, compared to women who are non-smokers.{{citation needed|date=November 2011}} |

Though the [[Teratogenesis|teratogenic]] properties of nicotine may or may not yet have been adequately researched, women who use [[nicotine gum]] and patches during the early stages of pregnancy face an increased risk of having babies with birth defects, according to a study of around 77,000 pregnant women in Denmark. The study found that women who use nicotine-replacement therapy in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy have a 60% greater risk of having babies with birth defects, compared to women who are non-smokers.{{citation needed|date=November 2011}} |

||

| Line 259: | Line 258: | ||

For instance, recent studies suggest that smokers require less frequent repeated [[revascularization]] after [[percutaneous coronary intervention]] (PCI).<ref name="cohen"/> Risk of [[ulcerative colitis]] has been frequently shown to be reduced by smokers on a dose-dependent basis; the effect is eliminated if the individual stops smoking.<ref name="ohcm">Longmore, M., Wilkinson, I., Torok, E. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine (Fifth Edition) p. 232</ref><ref> |

For instance, recent studies suggest that smokers require less frequent repeated [[revascularization]] after [[percutaneous coronary intervention]] (PCI).<ref name="cohen"/> Risk of [[ulcerative colitis]] has been frequently shown to be reduced by smokers on a dose-dependent basis; the effect is eliminated if the individual stops smoking.<ref name="ohcm">Longmore, M., Wilkinson, I., Torok, E. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine (Fifth Edition) p. 232</ref><ref> |

||

{{cite journal |author=Green JT, Richardson C, Marshall RW, ''et al.'' |title=Nitric oxide mediates a therapeutic effect of nicotine in ulcerative colitis |journal=Aliment Pharmacol Ther. |volume=14 |issue=11 |pages=1429–34 |year=2000 |month=Nov |pmid=11069313 |url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0269-2813&date=2000&volume=14&issue=11&spage=1429 |doi=10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00847.x}}</ref> |

{{cite journal |author=Green JT, Richardson C, Marshall RW, ''et al.'' |title=Nitric oxide mediates a therapeutic effect of nicotine in ulcerative colitis |journal=Aliment Pharmacol Ther. |volume=14 |issue=11 |pages=1429–34 |year=2000 |month=Nov |pmid=11069313 |url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0269-2813&date=2000&volume=14&issue=11&spage=1429 |doi=10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00847.x}}</ref> |

||

Smoking also appears to interfere with development of [[Kaposi's sarcoma]] in patients with HIV, |

Smoking also appears to interfere with development of [[Kaposi's sarcoma]] in patients with HIV.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Goedert JJ, Vitale F, Lauria C, ''et al.'' |title=Risk factors for classical Kaposi's sarcoma |journal=J. Natl. Cancer Inst. |volume=94 |issue=22 |pages=1712–8 |year=2002 |month=November |pmid=12441327 |url=http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/content/94/22/1712.full}}<br/> |

||

{{cite news |

{{cite news |

||

| title = Smoking Cuts Risk of Rare Cancer |

| title = Smoking Cuts Risk of Rare Cancer |

||

| Line 312: | Line 311: | ||

| pmid = 11422156 |

| pmid = 11422156 |

||

| accessdate = 2006-11-06}}</ref> |

| accessdate = 2006-11-06}}</ref> |

||

A plausible mechanism of action in these cases may be nicotine acting as an [[Inflammation|anti-inflammatory agent]], and interfering with the inflammation-related disease process, as nicotine has vasoconstrictive effects.<ref name=sciam>{{cite journal | |

A plausible mechanism of action in these cases may be nicotine acting as an [[Inflammation|anti-inflammatory agent]], and interfering with the inflammation-related disease process, as nicotine has vasoconstrictive effects.<ref name=sciam>{{cite journal |first=Lisa |last=Melton | title=Body Blazes | journal=Scientific American | month=June | year=2006 | page=24 | url=http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?chanID=sa006&colID=5&articleID=00080902-A2CF-146C-9D1E83414B7F0000 |pmid=16711354 }}</ref> |

||

Tobacco smoke has been shown to contain compounds capable of inhibiting [[monoamine oxidase]], which is responsible for the degradation of dopamine in the human brain. When dopamine is broken down by MAO-B, neurotoxic by-products are formed, possibly contributing to Parkinson's and Alzheimers disease.<ref> |

Tobacco smoke has been shown to contain compounds capable of inhibiting [[monoamine oxidase]], which is responsible for the degradation of dopamine in the human brain. When dopamine is broken down by MAO-B, neurotoxic by-products are formed, possibly contributing to Parkinson's and Alzheimers disease.<ref> |

||

| Line 345: | Line 344: | ||

| accessdate =2006-11-06}} |

| accessdate =2006-11-06}} |

||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

have been published. While tobacco smoking is associated with an increased risk of alzheimer's disease,<ref name="pmid19105840">{{cite journal |author=Peters R, Poulter R, Warner J, Beckett N, Burch L, Bulpitt C |title=Smoking, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly, a systematic review |journal=BMC Geriatr |volume=8 |

have been published. While tobacco smoking is associated with an increased risk of alzheimer's disease,<ref name="pmid19105840">{{cite journal |author=Peters R, Poulter R, Warner J, Beckett N, Burch L, Bulpitt C |title=Smoking, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly, a systematic review |journal=BMC Geriatr |volume=8 |pages=36 |year=2008 |pmid=19105840 |pmc=2642819 |doi=10.1186/1471-2318-8-36 }}</ref> there is evidence that nicotine itself has the potential to prevent and treat alzheimer's disease.<ref name="pmid19184661">{{cite journal |author=Henningfield JE, Zeller M |title=Nicotine psychopharmacology: policy and regulatory |journal=Handb Exp Pharmacol |issue=192 |pages=511–34 |year=2009 |pmid=19184661 |doi=10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_18 }}</ref> |

||

Nicotine has been shown to delay the onset of Parkinson's disease in studies involving monkeys and humans.<ref> |

Nicotine has been shown to delay the onset of Parkinson's disease in studies involving monkeys and humans.<ref> |

||

{{cite web |

{{cite web |

||

| Line 371: | Line 370: | ||

| accessdate = 2009-12-27 |

| accessdate = 2009-12-27 |

||

| work=Reuters}} |

| work=Reuters}} |

||

</ref> A study has shown a protective effect of nicotine itself on neurons due to nicotine activation of α7-nAChR and the PI3K/Akt pathway which inhibits [[apoptosis-inducing factor]] release and mitochondrial translocation, [[cytochrome c]] release and [[caspase 3]] activation.<ref>J Neurochem. 2011 |

</ref> A study has shown a protective effect of nicotine itself on neurons due to nicotine activation of α7-nAChR and the PI3K/Akt pathway which inhibits [[apoptosis-inducing factor]] release and mitochondrial translocation, [[cytochrome c]] release and [[caspase 3]] activation.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Yu W, Mechawar N, Krantic S, Quirion R |title=α7 Nicotinic receptor activation reduces β-amyloid-induced apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-independent death through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling |journal=J. Neurochem. |volume=119 |issue=4 |pages=848–58 |year=2011 |month=November |pmid=21884524 |doi=10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07466.x }}</ref> |

||

Recent studies have indicated that nicotine can be used to help adults suffering from [[autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy]]. The same areas that cause seizures in that form of [[epilepsy]] are responsible for processing nicotine in the brain.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cnsforum.com/commenteditem/3c5dccdc-27fb-4b80-9516-ab81e3e4ea6c/default.aspx |title=Nicotine as an antiepileptic agent in ADNFLE: An n-of-one study}}</ref> |

Recent studies have indicated that nicotine can be used to help adults suffering from [[autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy]]. The same areas that cause seizures in that form of [[epilepsy]] are responsible for processing nicotine in the brain.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cnsforum.com/commenteditem/3c5dccdc-27fb-4b80-9516-ab81e3e4ea6c/default.aspx |title=Nicotine as an antiepileptic agent in ADNFLE: An n-of-one study}}</ref> |

||

| Line 379: | Line 378: | ||

Nicotine appears to improve [[ADHD]] symptoms. Some studies are focusing on benefits of nicotine therapy in adults with ADHD.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://adam.about.com/reports/000030_1.htm|title=Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder|accessdate=21 September 2009}}</ref> |

Nicotine appears to improve [[ADHD]] symptoms. Some studies are focusing on benefits of nicotine therapy in adults with ADHD.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://adam.about.com/reports/000030_1.htm|title=Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder|accessdate=21 September 2009}}</ref> |

||

While acute/initial nicotine intake causes activation of nicotine receptors, chronic low doses of nicotine use leads to desensitisation of nicotine receptors (due to the development of tolerance) and results in an antidepressant effect, with research showing low dose nicotine patches being an effective treatment of [[major depressive disorder]] in non-smokers.<ref name="pmid20965579">{{cite journal |author=Mineur YS, Picciotto MR |title=Nicotine receptors and depression: revisiting and revising the cholinergic hypothesis |journal=Trends Pharmacol. Sci. |volume=31 |issue=12 |pages=580–6 |year=2010 |month=December |pmid=20965579 |pmc=2991594 |doi=10.1016/j.tips.2010.09.004 |

While acute/initial nicotine intake causes activation of nicotine receptors, chronic low doses of nicotine use leads to desensitisation of nicotine receptors (due to the development of tolerance) and results in an antidepressant effect, with research showing low dose nicotine patches being an effective treatment of [[major depressive disorder]] in non-smokers.<ref name="pmid20965579">{{cite journal |author=Mineur YS, Picciotto MR |title=Nicotine receptors and depression: revisiting and revising the cholinergic hypothesis |journal=Trends Pharmacol. Sci. |volume=31 |issue=12 |pages=580–6 |year=2010 |month=December |pmid=20965579 |pmc=2991594 |doi=10.1016/j.tips.2010.09.004 }}</ref> |

||

Nicotine (in the form of chewing gum or a transdermal patch) is being explored as an experimental treatment for [[OCD]]. Small studies show some success, even in otherwise treatment-refractory cases.<ref name="pmid15610960">{{cite journal |author=Pasquini M, Garavini A, Biondi M |title=Nicotine augmentation for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. A case report |journal=Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry |volume=29 |issue=1 |pages=157–9 |year=2005 |month=January |pmid=15610960 |doi=10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.08.011 |

Nicotine (in the form of chewing gum or a transdermal patch) is being explored as an experimental treatment for [[OCD]]. Small studies show some success, even in otherwise treatment-refractory cases.<ref name="pmid15610960">{{cite journal |author=Pasquini M, Garavini A, Biondi M |title=Nicotine augmentation for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. A case report |journal=Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry |volume=29 |issue=1 |pages=157–9 |year=2005 |month=January |pmid=15610960 |doi=10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.08.011 }}</ref><ref name="pmid15610934">{{cite journal |author=Lundberg S, Carlsson A, Norfeldt P, Carlsson ML |title=Nicotine treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder |journal=Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry |volume=28 |issue=7 |pages=1195–9 |year=2004 |month=November |pmid=15610934 |doi=10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.06.014 }}</ref><ref name="pmid11822995">{{cite journal |author=Tizabi Y, Louis VA, Taylor CT, Waxman D, Culver KE, Szechtman H |title=Effect of nicotine on quinpirole-induced checking behavior in rats: implications for obsessive-compulsive disorder |journal=Biol. Psychiatry |volume=51 |issue=2 |pages=164–71 |year=2002 |month=January |pmid=11822995 |doi= 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01207-0|url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006322301012070}}</ref> |

||

The relationship between smoking and inflammatory bowel disease is now firmly established but remains a source of confusion among both patients and doctors. It is negatively associated with ulcerative colitis but positively associated with Crohn's disease. In addition, it has opposite influences on the clinical course of the two conditions with benefit in ulcerative colitis but a detrimental effect in Crohn's disease.<ref>Thomas GA |

The relationship between smoking and inflammatory bowel disease is now firmly established but remains a source of confusion among both patients and doctors. It is negatively associated with ulcerative colitis but positively associated with Crohn's disease. In addition, it has opposite influences on the clinical course of the two conditions with benefit in ulcerative colitis but a detrimental effect in Crohn's disease.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Thomas GA, Rhodes J, Green JT, Richardson C |title=Role of smoking in inflammatory bowel disease: implications for therapy |journal=Postgrad Med J |volume=76 |issue=895 |pages=273–9 |year=2000 |month=May |pmid=10775279 |pmc=1741576 |url=http://pmj.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10775279}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Rubin DT, Hanauer SB |title=Smoking and inflammatory bowel disease |journal=Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol |volume=12 |issue=8 |pages=855–62 |year=2000 |month=August |pmid=10958212 }}</ref> |

||

==Research as a potential basis for an antipsychotic agent== |

==Research as a potential basis for an antipsychotic agent== |

||

When the metabolites of nicotine were isolated and their effect on first the animal brain and then the human brain in people with schizophrenia were studied, it was shown that the effects helped with cognitive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Therefore, the nicotinergic agents, as antipsychotics which do not contain nicotine but act on the same receptors in the brain are showing promise as adjunct antipsychotics in early stages of FDA studies on schizophrenia. |

When the metabolites of nicotine were isolated and their effect on first the animal brain and then the human brain in people with schizophrenia were studied, it was shown that the effects helped with cognitive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Therefore, the nicotinergic agents, as antipsychotics which do not contain nicotine but act on the same receptors in the brain are showing promise as adjunct antipsychotics in early stages of FDA studies on schizophrenia. |

||

The [[prepulse inhibition]] (PPI) is a phenomenon in which a weak prepulse attenuates the response to a subsequent startling stimulus. Therefore, PPI is believed to have face, construct, and predictive validity for the PPI disruption in schizophrenia, and it is widely used as a model to study the neurobiology of this disorder and for screening antipsychotics.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Suemaru K, Kohnomi S, Umeda K, Araki H.|year=2008|title=Alpha7 nicotinic receptor agonists have reported to reverse the PPI disruption|journal=Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi|volume=28|issue=3|pages=121–6|pmid=18646597|language=Japanese|first1=K|last2=Kohnomi|first2=S|last3=Umeda|first3=K|last4=Araki|first4=H}}</ref> There are genes that may predispose people with schizophrenia to nicotine use.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = De Luca | first1 = V | last2 = Wong | first2 = AH | last3 = Muller | first3 = DJ | last4 = Wong | first4 = GW | last5 = Tyndale | first5 = RF | last6 = Kennedy | first6 = JL. | author-separator =, |

The [[prepulse inhibition]] (PPI) is a phenomenon in which a weak prepulse attenuates the response to a subsequent startling stimulus. Therefore, PPI is believed to have face, construct, and predictive validity for the PPI disruption in schizophrenia, and it is widely used as a model to study the neurobiology of this disorder and for screening antipsychotics.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Suemaru K, Kohnomi S, Umeda K, Araki H.|year=2008|title=Alpha7 nicotinic receptor agonists have reported to reverse the PPI disruption|journal=Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi|volume=28|issue=3|pages=121–6|pmid=18646597|language=Japanese|first1=K|last2=Kohnomi|first2=S|last3=Umeda|first3=K|last4=Araki|first4=H}}</ref> There are genes that may predispose people with schizophrenia to nicotine use.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = De Luca | first1 = V | last2 = Wong | first2 = AH | last3 = Muller | first3 = DJ | last4 = Wong | first4 = GW | last5 = Tyndale | first5 = RF | last6 = Kennedy | first6 = JL. | author-separator =, | year = 2004 | title = Evidence of association between smoking and alpha7 nicotinic receptor subunit gene in schizophrenia patients | journal = Neuropsychopharmacology | volume = 29 | issue = 8| pages = 1522–6 | pmid = 15100704 | doi=10.1038/sj.npp.1300466}}</ref> |

||

Therefore with these factors taken together the heavy usage of cigarettes and other nicotine related products among people with schizophrenia may be explained and novel antipsychotic agents developed that have these effects in a manner that is not harmful and controlled and is a promising arena of research for schizophrenia. |

Therefore with these factors taken together the heavy usage of cigarettes and other nicotine related products among people with schizophrenia may be explained and novel antipsychotic agents developed that have these effects in a manner that is not harmful and controlled and is a promising arena of research for schizophrenia. |

||

| Line 413: | Line 412: | ||

**[[Snus]] |

**[[Snus]] |

||

**[[Electronic Cigarette]] |

**[[Electronic Cigarette]] |

||

*[[Psychoactive drug]] |

*[[Psychoactive drug]] |

||

*[[Drug Discovery and Development: Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Agonists]] |

*[[Drug Discovery and Development: Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Agonists]] |

||

Revision as of 11:06, 19 May 2012

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Nicorette, Nicotrol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Dependence liability | Medium to high |

| Routes of administration | smoked (as smoking tobacco, mapacho, etc.), insufflated (as tobacco snuff or nicotine nasal spray), chewed (as nicotine gum, tobacco gum or chewing tobacco), transdermal (as nicotine patch, nicogel or topical tobacco paste), intrabuccal (as dipping tobacco, snuffs, dissolvable tobacco or creamy snuff), vaporized (as electronic cigarette, etc.), directly inhaled (as nicotine inhaler), oral (as nicotini), buccal (as snus) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 20 to 45% (oral) |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 2 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.177 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H14N2 |

| Molar mass | 162.26 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.01 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | −79 °C (−110 °F) |

| Boiling point | 247 °C (477 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Nicotine is an alkaloid found in the nightshade family of plants (Solanaceae); biosynthesis takes place in the roots and accumulation occurs in the leaves. It constitutes approximately 0.6–3.0% of the dry weight of tobacco[2] and is present in the range of 2-7 µg/kg of various edible plants.[3] It functions as an antiherbivore chemical; therefore, nicotine was widely used as an insecticide in the past[4][5][6] and nicotine analogs such as imidacloprid are currently widely used.

In low concentrations (an average cigarette yields about 1 mg of absorbed nicotine), the substance acts as a stimulant in mammals, while high concentrations (30-60 mg[7]) can be fatal.[8] This stimulant effect is the main factor responsible for the dependence-forming properties of tobacco smoking. According to the American Heart Association, nicotine addiction has historically been one of the hardest addictions to break, while the pharmacological and behavioral characteristics that determine tobacco addiction are similar to those determining addiction to heroin and cocaine. The nicotine content of popular American-brand cigarettes has slowly increased over the years, and one study found that there was an average increase of 1.6% per year between the years of 1998 and 2005. This was found for all major market categories of cigarettes.[9]

Research in 2011 has found that nicotine inhibits chromatin-modifying enzymes (class I and II histone deacetylases) which increases the ability of cocaine to cause an addiction.[10]

History and name

Nicotine is named after the tobacco plant Nicotiana tabacum, which in turn is named after Jean Nicot de Villemain, French ambassador in Portugal, who sent tobacco and seeds brought from Brazil by the Portuguese colonist in São Paulo, Luís de Góis (also a future jesuit in India), to Paris in 1560, and promoted their medicinal use. Nicotine was first isolated from the tobacco plant in 1828 by physician Wilhelm Heinrich Posselt and chemist Karl Ludwig Reimann of Germany, who considered it a poison.[11][12] Its chemical empirical formula was described by Melsens in 1843,[13] its structure was discovered by Adolf Pinner and Richard Wolffenstein in 1893, and it was first synthesized by A. Pictet and Crepieux in 1904.[14]

Historical use of nicotine as an insecticide

Tobacco was introduced to Europe in 1559, and by the late 17th century, it was used not only for smoking but also as an insecticide. After World War II, over 2,500 tons of nicotine insecticide (waste from the tobacco industry) were used worldwide, but by the 1980s the use of nicotine insecticide had declined below 200 tons. This was due to the availability of other insecticides that are cheaper and less harmful to mammals.[5]

Currently, nicotine is a permitted pesticide for organic farming because it is derived from a botanical source. Nicotine sulfate sold for use as a pesticide is labeled "DANGER," indicating that it is highly toxic.[6] However, in 2008, the EPA received a request to cancel the registration of the last nicotine pesticide registered in the United States.[15] This request was granted, and after 1 January 2014, this pesticide will not be available for sale.[16]

Chemistry

Nicotine is a hygroscopic, oily liquid that is miscible with water in its base form. As a nitrogenous base, nicotine forms salts with acids that are usually solid and water soluble. Nicotine easily penetrates the skin. As shown by the physical data, free base nicotine will burn at a temperature below its boiling point, and its vapors will combust at 308 K (35 °C; 95 °F) in air despite a low vapor pressure. Because of this, most of the nicotine is burned when a cigarette is smoked; however, enough is inhaled to cause pharmacological effects.

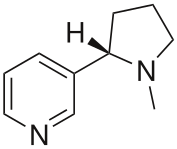

Optical activity

Nicotine is optically active, having two enantiomeric forms. The naturally occurring form of nicotine is levorotatory with a specific rotation of [α]D = –166.4° ((−)-nicotine). The dextrorotatory form, (+)-nicotine is physiologically less active than (–)-nicotine. (−)-nicotine is more toxic than (+)-nicotine.[17] The salts of (+)-nicotine are usually dextrorotatory.

Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetics

As nicotine enters the body, it is distributed quickly through the bloodstream and crosses the blood-brain barrier reaching the brain within 10–20 seconds after inhalation.[19] The elimination half-life of nicotine in the body is around two hours.[20]

The amount of nicotine absorbed by the body from smoking depends on many factors, including the types of tobacco, whether the smoke is inhaled, and whether a filter is used. For chewing tobacco, dipping tobacco, snus and snuff, which are held in the mouth between the lip and gum, or taken in the nose, the amount released into the body tends to be much greater than smoked tobacco.[clarification needed][citation needed] Nicotine is metabolized in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes (mostly CYP2A6, and also by CYP2B6). A major metabolite is cotinine.

Other primary metabolites include nicotine N'-oxide, nornicotine, nicotine isomethonium ion, 2-hydroxynicotine and nicotine glucuronide.[21] Under some conditions, other substances may be formed such as myosmine.[22]

Glucuronidation and oxidative metabolism of nicotine to cotinine are both inhibited by menthol, an additive to mentholated cigarettes, thus increasing the half-life of nicotine in vivo.[23]

Detection of use

Medical detection

Nicotine can be quantified in blood, plasma, or urine to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning or to facilitate a medicolegal death investigation. Urinary or salivary cotinine concentrations are frequently measured for the purposes of pre-employment and health insurance medical screening programs. Careful interpretation of results is important, since passive exposure to cigarette smoke can result in significant accumulation of nicotine, followed by the appearance of its metabolites in various body fluids.[24][25] Nicotine use is not regulated in competitive sports programs, yet the drug has been shown to have a significant beneficial effect on athletic endurance in subjects who have not used nicotine before.[26]

Pharmacodynamics

Nicotine acts on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, specifically the ganglion type nicotinic receptor and one CNS nicotinic receptor. The former is present in the adrenal medulla and elsewhere, while the latter is present in the central nervous system (CNS). In small concentrations, nicotine increases the activity of these receptors. Nicotine also has effects on a variety of other neurotransmitters through less direct mechanisms.

In the central nervous system

By binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, nicotine increases the levels of several neurotransmitters - acting as a sort of "volume control". It is thought that increased levels of dopamine in the reward circuits of the brain are responsible for the apparent euphoria and relaxation, and addiction caused by nicotine consumption. Nicotine has a higher affinity for acetylcholine receptors in the brain than those in skeletal muscle, though at toxic doses it can induce contractions and respiratory paralysis.[27] Nicotine's selectivity is thought to be due to a particular amino acid difference on these receptor subtypes.[28]

Tobacco smoke contains anabasine, anatabine, and nornicotine.[citation needed] It also contains the monoamine oxidase inhibitors harman and norharman.[29] These beta-carboline compounds significantly decrease MAO activity in smokers.[29][30] MAO enzymes break down monoaminergic neurotransmitters such as dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. It is thought that the powerful interaction between the MAOI's and the nicotine is responsible for most of the addictive properties of tobacco smoking.[31] The addition of five minor tobacco alkaloids increases nicotine-induced hyperactivity, sensitization and intravenous self-administration in rats.[32]

Chronic nicotine exposure via tobacco smoking up-regulates alpha4beta2* nAChR in cerebellum and brainstem regions[33][34] but not habenulopeduncular structures.[35] Alpha4beta2 and alpha6beta2 receptors, present in the ventral tegmental area, play a crucial role in mediating the reinforcement effects of nicotine.[36]

In the sympathetic nervous system

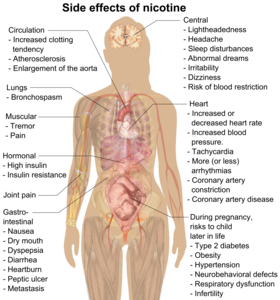

Nicotine also activates the sympathetic nervous system,[37] acting via splanchnic nerves to the adrenal medulla, stimulates the release of epinephrine. Acetylcholine released by preganglionic sympathetic fibers of these nerves acts on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, causing the release of epinephrine (and norepinephrine) into the bloodstream. Nicotine also has an affinity for melanin-containing tissues due to its precursor function in melanin synthesis or due to the irreversible binding of melanin and nicotine. This has been suggested to underlie the increased nicotine dependence and lower smoking cessation rates in darker pigmented individuals. However, further research is warranted before a definite conclusive link can be inferred.[38]

In adrenal medulla

By binding to ganglion type nicotinic receptors in the adrenal medulla nicotine increases flow of adrenaline (epinephrine), a stimulating hormone and neurotransmitter. By binding to the receptors, it causes cell depolarization and an influx of calcium through voltage-gated calcium channels. Calcium triggers the exocytosis of chromaffin granules and thus the release of epinephrine (and norepinephrine) into the bloodstream. The release of epinephrine (adrenaline) causes an increase in heart rate, blood pressure and respiration, as well as higher blood glucose levels.[39]

Nicotine is the natural product of tobacco, having a half-life of 1 to 2 hours. Cotinine is an active metabolite of nicotine that remains in the blood for 18 to 20 hours, making it easier to analyze due to its longer half-life.[40]

Psychoactive effects