'Akbara

'Akbara

عكبرة | |

|---|---|

Village | |

Modern village of Akbara | |

| Etymology: possibly from male jerboa[1] | |

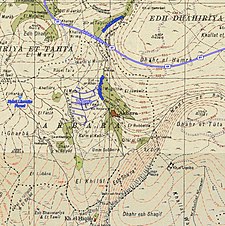

A series of historical maps of the area around 'Akbara (click the buttons) | |

Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 32°56′22″N 35°29′58″E / 32.93944°N 35.49944°E | |

| Palestine grid | 197/260 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Safad |

| Date of depopulation | 10 May 1948[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,224 dunams (3.224 km2 or 1.245 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 390 |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

'Akbara (Template:Lang-ar) is an Arab village in the Israeli municipality of Safed, which included in 2010 more than 200 families.[5] It is 2.5 km south of Safed City. The village was rebuilt in 1977, close to the old village destroyed in 1948 during the 1947–1949 Palestine war.

Location

The village of 'Akbara was situated 2.5 km south of Safad, along the two sides of a deep wadi that ran north–south. Southeast of the village lay Khirbet al-'Uqeiba, identified as the Roman village Achabare, or Acchabaron. This khirba was a populated village as late as 1904.[6]

History

The first 'Akbara mention is during Second Temple period by Josephus Flavius, he noted the rock of Acchabaron (Ακχαβαρων πετραν) among the places in the Upper Galilee he fortified as a preparation for the First Jewish Revolt, while leading rebel forces against the Romans in Galilee.[7][8] This site is identified with caves situated along the cliffs south of 'Akbara.[9]

The nearby Khirbet al-'Uqeiba was first excavated during the Mandate period, and was shown to contain remains such as building foundations, hewn stones, and wine presses.[10] Cisterns,[11] tombs, oil press and walls of ancient synagogue have also been found.[12] Foerster identifies the ruins as the "early Galilean type" synagogue.[13] According to Liebner, a 1965 letter in the IAA composed by antiquities inspector N. Tfilinski notes a Hebrew inscription on a building stone found at the site. The current location of the stone is unknown.[14]

Above the settlement, a 135 m high vertical cliff is located. There are one hundred and twenty-nine natural and man-made caves interconnected by passages in the cliff. According to tradition, those caves were used for shelter by Jews during their war with Romans. During archeological excavations, coins from Dor and Sepphoris were found in the caves, dating to the Roman emperor Trajan period.[15]

Akbara/Akbari/Akbora/Akborin is mentioned several times in Rabbinic literature as early as second half of the third century CE. According to some traditions Rabbi Yannai disciplines lived in 'Akbara forming an agricultural community; R. Yannai established a bet midrash there.[16][17][18] The earliest mention of this bet midrash is in the context of discussions between Rabbi Yohanan and sages of 'Akbara.[19] According to Talmud school of Rabbi Jose bar Abin was also in Akbara.[20] Several of the rabbis mentioned in Pirkei Avot lived in 'Akbara.[21] Akbara is mentioned as the burial place of several Talmudic sages: Rabbi Nehurai also Rabbi Yannai and Rabbi Dostai his son are buried "in the gardens" "by the spring".[20] According to tradition, the body of Rabbi Elazar ben Simeon was laying for twenty two years in his widow's garret in Akbara since he told her not to allow his colleagues to bury him. Rabbi Elazar ben Simeon feared to be dishonoured due to his aid to the Romans.[22][23][24]

The local Jewish community is attested during Fatimid rule of 969 to 1099 by the Cairo Geniza.[25] Samuel ben Samson visited 'Akbara during his 1210 Palestine pilgrimage, he described the tomb of Rabbi Meir he had found there.[26] In 1258 Jacob of Paris visited Akbara and found there, according to Pirkei Avot, tombs of Rabbi Nehurai.[20]

Ottoman era

'Akbara, was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517. Moshe Basola visited the village in 1522 and said that he had found there "destroyed synagogue, 3 cubits high remaining on two sides". Later in 1968 the remains of the synagogue were identified by Foester.[27] In the census of 1596, the village was part of the nahiya ("subdistrict") of Jira, part of Liwa Safad, with a population of 36 households and 1 bachelor, all Muslims. It paid taxes on a number of crops and produce, including wheat, barley, summer crops, olives, occasional revenues, goats, beehives, and a press which was either used for processing grapes or olives; a total of 6,115 akçe. 6/24 of the revenue went to a waqf.[28][29]

In 1648 a Turkish traveler Evliya Tshelebi visited Galilee and reflected on history of Akbara cliff caves, which according to tradition were used as a shelter by Jews:

"The children of Israel escaped the plague and hid in these caves. Then Allah sent them a bad spirit which caused them to perish within the caves. Their skeletons, heaped together, can be seen there to this day."[15]

In 1838, it was noted as a village in the Safad district,[30] while in 1875 Victor Guérin visited, and described it thus:

"The ruins of Akbara cover a hillock whose slopes were formerly sustained by walls forming terraces; the threshing floors of an Arab village occupy the summit. Round these are grouped the remains of ancient constructions now overthrown." "The village lies on the east of the wady. It is dominated by a platform on which foundations can be traced of a rectangular enclosure called el Kuneiseh, measuring thirty paces in length by twenty-three in breadth. It stands east and west, and was firmly constructed of good cut stones. The interior is at present given up to cultivation. This enclosure seems to have been once a Christian church."[31]

In 1881, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described Akbara as a village built of stone and adobe with about 90 inhabitants who cultivated olive and fig trees.[32]

A population list from about 1887 showed Akbara to have about 335 inhabitants, all Muslims.[33]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Akbara had a population of 147; all Muslims,[34] increasing in the 1931 census to 275, still all Muslims, in a total of 49 houses.[35]

During this period the village houses were made of masonry.[36] In the 1945 statistics the population was 390 Muslims,[4] and the total land area was 3,224 dunums;[3] 2,222 dunums was used for cereals, 199 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards,[37] while 6 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[38]

Israeli era

During the siege of Safad 'Akbara was targeted for occupation in line with Plan Dalet.[39] The Hagana attack was launched on 9 May and completed by the Palmach first battalion. It was found that many of the villagers had fled due to news of Deir Yassin and 'Ein al Zeitun, the village was then blown up and destroyed.[2]

On 25 May 1948, during Operation Yiftah, under the command of Yigal Allon, Galilee was cleared of its Palestinian Arab population.[40] The Palmach's First Battalion.[41] Following the 25 May exodus of al-Khisas the last 55 villagers who had remained in their homes for just over a year were 'transferred' by Israeli forces despite having good relations and collaborating with Jewish settlements in the area.[42] During the night of 5/6 June 1949, the village of al-Khisas was surrounded by trucks and the villagers were forced into the trucks ’with kicks, curses and maltreatment,’ in the words of a Mapam Knesset member, Elizer Peri, quoted by Morris:

"The remaining villagers said that they had been ’forced with their hands to destroy their dwellings,’ and had been treated like ’cattle.’ They were then dumped on a bare, sun-scorched hillside near the village of ’Akbara [by then an abandoned Palestinian Arab village] where they were left ’wandering in the wilderness, thirsty and hungry.’ They lived there under inhuman conditions for years afterwards," along with the inhabitants of at least two other villages (Qaddita and al-Ja'una) expelled in similar circumstances.[43]

The expellees remained at ’Akbara for eighteen years until agreeing to resettlement in Wadi Hamam.[42]

Salman Abu-Sitta, author of the Atlas of Palestine,[44] estimated that the number of Palestinian refugees from 'Akbara in 1998 was 1,852 people.[45]

Of what remains of 'Akbara's built structures, Walid Khalidi wrote in 1992 that "The original inhabitants of the village were replaced by 'internal' refugees from Qaddita villages several kilometers north of Safad. Since 1980, however, these internal refugees have been gradually relocated to the nearby, planned village of 'Akbara, 0.5 km west of the old village site. As a precondition of the relocation, each family was required to demolish its home in the former village. Today, fifteen of the old houses still stand on the site, in addition to the school. The new village of 'Akbara was placed under the administration of the city of Safad in 1977.[45][46] It is now a neighbourhood of the city of Safed.[clarification needed]

See also

References

- ^ Palmer, 1881, pp. 61, 66

- ^ a b Morris, 2004, p. 224

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 69

- ^ a b Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 9

- ^ Ashkenazi, Eli (2010-11-04). "Safed, a Model for Coexistence or Sectarian Tinderbox?".

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 430.

- ^ Leibner, 2009, p. 108

- ^ Bohstrom, Philippe (2016-09-29). "Caves in Which Jewish Rebels Hid From Romans 2,000 Years Ago Found in Galilee".

- ^ Rogers, Guy MacLean (2021). For the Freedom of Zion: the Great Revolt of Jews against Romans, 66-74 CE. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 532. ISBN 978-0-300-24813-5.

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 431

- ^ Dauphin, 1998, pp. 658-9

- ^ Tsafrir, Di Segni and Green, 1994, p. 56

- ^ Marilyn Joyce Segal Chiat (1 January 1982). Handbook of Synagogue Architecture. Scholars Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-89130-524-8.

- ^ "LXIII. Acchabaron (mod. ʿAkbara)", Volume 5/Part 1 Galilaea and Northern Regions: 5876-6924, De Gruyter, pp. 311–311, 2023-03-20, doi:10.1515/9783110715774-071/html, ISBN 978-3-11-071577-4, retrieved 2024-02-07

- ^ a b Shivtiel, Yinon; Frumkin, Amos (2014). "The use of caves as security measures in the Early Roman Period in the Galilee: Cliff Settlements and Shelter Caves". Caderno de Geografia. 24 (41): 79–81, 85–87. ISSN 2318-2962.

- ^ A'haron Oppenheimer (2005). Between Rome and Babylon: Studies in Jewish Leadership and Society. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-3-16-148514-5.

- ^ Stuart S. Miller (2006). Sages and Commoners in Late Antique ʼEreẓ Israel: A Philological Inquiry Into Local Traditions in Talmud Yerushalmi. Mohr Siebeck. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-16-148567-1.

- ^ Ben Tsiyon Rozenfeld (2010). Torah Centers and Rabbinic Activity in Palestine, 70-400 CE: History and Geographic Distribution. BRILL. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-90-04-17838-0.

- ^ Leibner, 2009, p. 109

- ^ a b c Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 205

- ^ Albert Victor (duke of Clarence and Avondale); George V (King of Great Britain) (1886). The Cruise of Her Majesty's Ship "Bacchante", 1879-1882: The East. Macmillan and co. p. 695.

- ^ Dov Aryeh B. Leib Friedman (1896). Rabbis of Ancient Times: Biographical Sketches of the Talmudic Period (300 B.C.E. to 500 C.E.). Supplemented with Maxims and Proverbs of the Talmud. Rochester Volksblatt. pp. 19–20.

- ^ Benjamin De Tudèle (1841). The Itinerary of Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela. A. Asher. p. 427.

- ^ Heinrich Graetz (1873). History of the Jews from the Downfall of the Jewish State to the Conclusion of the Talmud. American Jewish Publication Society. pp. 167–168.

- ^ Leibner, 2009, p. 106

- ^ Elkan Nathan Adler (4 April 2014). Jewish Travellers. Routledge. pp. 103–110. ISBN 978-1-134-28606-5.

- ^ Leibner, 2009, p. 107

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 176. Note that there is a typo in the grid numbers; they give grid numbers 197/200 for Akbar al-Hattab, however, on their maps it is placed in the correct position, around 197/260. Rhode, 1979, p. 69 Archived 2019-04-20 at the Wayback Machine correctly places Akbarat al-Hiqab at 197/260

- ^ Rhode, 1979, p. 6 Archived 2019-04-20 at the Wayback Machine writes that the register that Hütteroth and Abdulfattah studied was not from 1595/6, but from 1548/9

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, 2nd appendix, p. 134

- ^ Guérin, 1880, pp. 351–353, as given by Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 219

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 196. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 430.

- ^ Schumacher, 1888, p. 188

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Safad, p. 41

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 105

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, pp. 430–431

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 118

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 168

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 223

- ^ Morris 2004, p. 248

- ^ Morris 2004, p. 250

- ^ a b Benvenisti, 2002, pp. 206-207

- ^ Morris, 2004, pp. 511–512

- ^ Bibliography and References, Palestine Remembered, 25 June 2007, archived from the original on 9 January 2009, retrieved 20 December 2007

- ^ a b Welcome to 'Akbara, Palestine Remembered, archived from the original on 2008-07-04, retrieved 2007-12-20

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p xix

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benvenisti, M. (2002). Sacred Landscape: The Buried History of the Holy Land Since 1948. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23422-2.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (p. 205)

- Dauphin, C. (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). Vol. III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0860549054.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Gelber, Y. (2006). Palestine 1948: War, Escape And The Emergence Of The Palestinian Refugee Problem. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1-84519-075-0.

- Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 3: Galilee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains:The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Leibner, Uzi (2009). Settlement and History in Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine Galilee: An Archaeological Survey of the Eastern Galilee. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-149871-8.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Moore, Dahlia; Aweiss, Salem (2004). Bridges Over Troubled Water: A Comparative Study Of Jews, Arabs, and Palestinians. Praeger/Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-98060-X.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Nazzal, Nafez (1978). The Palestinian Exodus from Galilee 1948. Beirut: The Institute for Palestine Studies. pp. 43–45. ISBN 9780887281280.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Rhode, H. (1979). Administration and Population of the Sancak of Safed in the Sixteenth Century (PhD). Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Rogan, E.; Shlaim, A. (2007). The War for Palestine: Rewriting the History of 1948. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87598-1.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Tsafrir, Y.; Leah Di Segni; Judith Green (1994). (TIR): Tabula Imperii Romani: Judaea, Palaestina. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. ISBN 965-208-107-8.

External links

- Welcome to Akbara

- 'Akbara, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 4: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- 'Akbara, at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- Akbara, Dr. Khalil Rizk.

- 3akbara from Dr. Moslih Kanaaneh