California

California | |

|---|---|

| Nickname: The Golden State[1] | |

| Motto: | |

| Anthem: "I Love You, California" | |

Map of the United States with California highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Mexican Cession unorganized territory |

| Admitted to the Union | September 9, 1850 (31st) |

| Capital | Sacramento |

| Largest city | Los Angeles |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Greater Los Angeles |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Gavin Newsom (D) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Eleni Kounalakis (D) |

| Legislature | State Legislature |

| • Upper house | State Senate |

| • Lower house | State Assembly |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court of California |

| U.S. senators | Alex Padilla (D) Laphonza Butler (D) |

| U.S. House delegation |

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 163,696 sq mi (423,970 km2) |

| • Land | 155,959 sq mi (403,932 km2) |

| • Water | 7,737 sq mi (20,047 km2) 4.7% |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 760 mi (1,220 km) |

| • Width | 250 mi (400 km) |

| Elevation | 2,900 ft (880 m) |

| Highest elevation | 14,505 ft (4,421.0 m) |

| Lowest elevation | −279 ft (−85.0 m) |

| Population (2023) | |

| • Total | |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Density | 251.3/sq mi (97/km2) |

| • Rank | 11th |

| • Median household income | $78,700[7] |

| • Income rank | 5th |

| Demonym(s) | Californian Californio (archaic Spanish) Californiano (Spanish) |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| • Spoken language | |

| Time zone | UTC−08:00 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−07:00 (PDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | CA |

| ISO 3166 code | US-CA |

| Traditional abbreviation | Calif., Cal., Cali. |

| Latitude | 32°32′ N to 42° N |

| Longitude | 114°8′ W to 124°26′ W |

| Website | ca |

California is a state in the Western United States, lying on the American Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and an international border with the Mexican state of Baja California to the south. With nearly 39 million residents across an area of 163,696 square miles (423,970 km2),[11] it is the most populous U.S. state, the third-largest by area, and most populated subnational entity in North America.

Prior to European colonization, California was one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse areas in pre-Columbian North America. European exploration in the 16th and 17th centuries led to the colonization by the Spanish Empire. The area became a part of Mexico in 1821, following its successful war for independence, but was ceded to the United States in 1848 after the Mexican–American War. The California gold rush started in 1848 and led to social and demographic changes, including depopulation of Indigenous peoples in the California genocide. The western portion of Alta California was then organized and admitted as the 31st state in 1850, as a free state, following the Compromise of 1850.

The Greater Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay areas are the nation's second- and fifth-most populous urban regions, with 19 million and 10 million residents respectively.[12] Los Angeles is the state's most populous city and the nation's second-most; California's capital is Sacramento. The state's diverse geography ranges from the Pacific Coast and metropolitan areas in the west to the Sierra Nevada mountains in the east, and from the redwood and Douglas fir forests in the northwest to the Mojave Desert in the southeast. Two-thirds of the nation's earthquake risk lies in California.[13] The Central Valley, a fertile agricultural area, dominates the state's center. The large size of the state results in climates that vary from moist temperate rainforest in the north to arid desert in the interior, as well as snowy alpine in the mountains. Droughts and wildfires are an ongoing issue.[14]

California's economy is the largest of any U.S. state, with a $4.0 trillion gross state product as of 2024[update].[15] It is the largest sub-national economy in the world. California's agricultural industry has the highest output of any U.S. state,[16][17][18] and is led by its dairy, almonds, and grapes.[19] With the busiest port in the country (Los Angeles), California plays a pivotal role in the global supply chain, hauling in about 40% of goods imported to the US.[20] Notable contributions to popular culture, ranging from entertainment, sports, music, and fashion, have their origins in California. California is the home of Hollywood, the oldest and one of the largest film industries in the world, profoundly influencing global entertainment. The San Francisco Bay and the Greater Los Angeles areas are seen as the centers of the global technology and U.S. film industries, respectively.[21]

Etymology

The Spaniards gave the name Las Californias to the peninsula of Baja California (in modern-day Mexico). As Spanish explorers and settlers moved north and inland, the region known as California, or Las Californias, grew. Eventually it included lands north of the peninsula, Alta California, part of which became the present-day U.S. state of California.

A 2017 state legislative document states, "Numerous theories exist as to the origin and meaning of the word 'California,'" and that all anyone knows is the name was added to a map by 1541 "presumably by a Spanish navigator."[22]

The name most likely derived from the mythical island of California in the fictional story of Queen Calafia, as recorded in a 1510 work The Adventures of Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo.[23] Queen Calafia's kingdom was said to be a remote land rich in gold and pearls, inhabited by beautiful Black women who wore gold armor and lived like Amazons, as well as griffins and other strange beasts.[23][24][25]

Abbreviations of the state's name include CA, Cal., Calif., Califas, and US-CA.

History

Indigenous

California was one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse areas in pre-Columbian North America.[26] Historians generally agree that there were at least 300,000 people living in California prior to European colonization.[27] The Indigenous peoples of California included more than 70 distinct ethnic groups, inhabiting environments ranging from mountains and deserts to islands and redwood forests.[28]

Living in these diverse geographic areas, the indigenous peoples developed complex forms of ecosystem management, including forest gardening to ensure the regular availability of food and medicinal plants.[29][30] This was a form of sustainable agriculture.[31] To mitigate destructive large wildfires from ravaging the natural environment, indigenous peoples developed a practice of controlled burning.[32] This practice was recognized for its benefits by the California government in 2022.[33]

These groups were also diverse in their political organization, with bands, tribes, villages, and, on the resource-rich coasts, large chiefdoms, such as the Chumash, Pomo and Salinan. Trade, intermarriage, craft specialists, and military alliances fostered social and economic relationships between many groups. Although nations would sometimes war, most armed conflicts were between groups of men for vengeance. Acquiring territory was not usually the purpose of these small-scale battles.[34]

Men and women generally had different roles in society. Women were often responsible for weaving, harvesting, processing, and preparing food, while men for hunting and other forms of physical labor. Most societies also had roles for people whom the Spanish referred to as joyas,[35] who they saw as "men who dressed as women".[36] Joyas were responsible for death, burial, and mourning rituals, and they performed women's social roles.[36] Indigenous societies had terms such as two-spirit to refer to them. The Chumash referred to them as 'aqi.[36] The early Spanish settlers detested and sought to eliminate them.[37]

Spanish period

The first Europeans to explore the coast of California were the members of a Spanish maritime expedition led by Portuguese captain Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542. Cabrillo was commissioned by Antonio de Mendoza, the Viceroy of New Spain, to lead an expedition up the Pacific coast in search of trade opportunities; they entered San Diego Bay on September 28, 1542, and reached at least as far north as San Miguel Island.[38] Privateer and explorer Francis Drake explored and claimed an undefined portion of the California coast in 1579, landing north of the future city of San Francisco. The first Asians to set foot on what would be the United States occurred in 1587, when Filipino sailors arrived in Spanish ships at Morro Bay.[39][40] Coincidentally the descendants of the Muslim Caliph Hasan ibn Ali in formerly Islamic Manila and had converted, then mixed Christianity with Islam, upon Spanish conquest, transited through California (Named after a Caliph) on their way to Guerrero, Mexico[41] where they played a future role in the wars of independence. Sebastián Vizcaíno explored and mapped the coast of California in 1602 for New Spain, putting ashore in Monterey.[42] Despite the on-the-ground explorations of California in the 16th century, Rodríguez's idea of California as an island persisted. Such depictions appeared on many European maps well into the 18th century.[43]

The Portolá expedition of 1769–70 was a pivotal event in the Spanish colonization of California, resulting in the establishment of numerous missions, presidios, and pueblos. The military and civil contingent of the expedition was led by Gaspar de Portolá, who traveled over land from Sonora into California, while the religious component was headed by Junípero Serra, who came by sea from Baja California. In 1769, Portolá and Serra established Mission San Diego de Alcalá and the Presidio of San Diego, the first religious and military settlements founded by the Spanish in California. By the end of the expedition in 1770, they would establish the Presidio of Monterey and Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo on Monterey Bay.

After the Portolà expedition, Spanish missionaries led by Father-President Serra set out to establish 21 Spanish missions of California along El Camino Real ("The Royal Road") and along the California coast, 16 sites of which having been chosen during the Portolá expedition. Numerous major cities in California grew out of missions, including San Francisco (Mission San Francisco de Asís), San Diego (Mission San Diego de Alcalá), Ventura (Mission San Buenaventura), or Santa Barbara (Mission Santa Barbara), among others.

Juan Bautista de Anza led a similarly important expedition throughout California in 1775–76, which would extend deeper into the interior and north of California. The Anza expedition selected numerous sites for missions, presidios, and pueblos, which subsequently would be established by settlers. Gabriel Moraga, a member of the expedition, would also christen many of California's prominent rivers with their names in 1775–1776, such as the Sacramento River and the San Joaquin River. After the expedition, Gabriel's son, José Joaquín Moraga, would found the pueblo of San Jose in 1777, making it the first civilian-established city in California.

During this same period, sailors from the Russian Empire explored along the northern coast of California. In 1812, the Russian-American Company established a trading post and small fortification at Fort Ross on the North Coast.[44][45] Fort Ross was primarily used to supply Russia's Alaskan colonies with food supplies. The settlement did not meet much success, failing to attract settlers or establish long term trade viability, and was abandoned by 1841.

During the War of Mexican Independence, Alta California was largely unaffected and uninvolved in the revolution,[46] though many Californios supported independence from Spain, which many believed had neglected California and limited its development.[47] Spain's trade monopoly on California had limited local trade prospects. Following Mexican independence, California ports were freely able to trade with foreign merchants. Governor Pablo Vicente de Solá presided over the transition from Spanish colonial rule to independent Mexican rule.

Mexican period

In 1821, the Mexican War of Independence gave the Mexican Empire (which included California) independence from Spain. For the next 25 years, Alta California remained a remote, sparsely populated, northwestern administrative district of the newly independent country of Mexico, which shortly after independence became a republic. The missions, which controlled most of the best land in the state, were secularized by 1834 and became the property of the Mexican government.[48] The governor granted many square leagues of land to others with political influence. These huge ranchos or cattle ranches emerged as the dominant institutions of Mexican California. The ranchos developed under ownership by Californios (Hispanics native of California) who traded cowhides and tallow with Boston merchants. Beef did not become a commodity until the 1849 California Gold Rush.

From the 1820s, trappers and settlers from the United States and Canada began to arrive in Northern California. These new arrivals used the Siskiyou Trail, California Trail, Oregon Trail and Old Spanish Trail to cross the rugged mountains and harsh deserts in and surrounding California. The early government of the newly independent Mexico was highly unstable, and in a reflection of this, from 1831 onwards, California also experienced a series of armed disputes, both internal and with the central Mexican government.[49] During this tumultuous political period Juan Bautista Alvarado was able to secure the governorship during 1836–1842.[50] The military action which first brought Alvarado to power had momentarily declared California to be an independent state, and had been aided by Anglo-American residents of California,[51] including Isaac Graham.[52] In 1840, one hundred of those residents who did not have passports were arrested, leading to the Graham Affair, which was resolved in part with the intercession of Royal Navy officials.[51]

One of the largest ranchers in California was John Marsh. After failing to obtain justice against squatters on his land from the Mexican courts, he determined that California should become part of the United States. Marsh conducted a letter-writing campaign espousing the California climate, the soil, and other reasons to settle there, as well as the best route to follow, which became known as "Marsh's route". His letters were read, reread, passed around, and printed in newspapers throughout the country, and started the first wagon trains rolling to California.[53] After ushering in the period of organized emigration to California, Marsh became involved in a military battle between the much-hated Mexican general, Manuel Micheltorena and the California governor he had replaced, Juan Bautista Alvarado. At the Battle of Providencia near Los Angeles, he convinced each side that they had no reason to be fighting each other. As a result of Marsh's actions, they abandoned the fight, Micheltorena was defeated, and California-born Pio Pico was returned to the governorship. This paved the way to California's ultimate acquisition by the United States.[54][55][56][57][58]

U.S. conquest and the California Republic

In 1846, a group of American settlers in and around Sonoma rebelled against Mexican rule during the Bear Flag Revolt. Afterward, rebels raised the Bear Flag (featuring a bear, a star, a red stripe and the words "California Republic") at Sonoma. The Republic's only president was William B. Ide,[59] who played a pivotal role during the Bear Flag Revolt. This revolt by American settlers served as a prelude to the later American military invasion of California and was closely coordinated with nearby American military commanders.

The California Republic was short-lived;[60] the same year marked the outbreak of the Mexican–American War (1846–1848).[61]

Commodore John D. Sloat of the United States Navy sailed into Monterey Bay in 1846 and began the U.S. military invasion of California, with Northern California capitulating in less than a month to the United States forces.[62] In Southern California, Californios continued to resist American forces. Notable military engagements of the conquest include the Battle of San Pasqual and the Battle of Dominguez Rancho in Southern California, as well as the Battle of Olómpali and the Battle of Santa Clara in Northern California. After a series of defensive battles in the south, the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed by the Californios on January 13, 1847, securing a censure and establishing de facto American control in California.[63]

Early American period

Following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (February 2, 1848) that ended the war, the westernmost portion of the annexed Mexican territory of Alta California soon became the American state of California, and the remainder of the old territory was then subdivided into the new American Territories of Arizona, Nevada, Colorado and Utah. The even more lightly populated and arid lower region of old Baja California remained as a part of Mexico. In 1846, the total settler population of the western part of the old Alta California had been estimated to be no more than 8,000, plus about 100,000 Native Americans, down from about 300,000 before Hispanic settlement in 1769.[64]

In 1848, only one week before the official American annexation of the area, gold was discovered in California, this being an event which was to forever alter both the state's demographics and its finances. Soon afterward, a massive influx of immigration into the area resulted, as prospectors and miners arrived by the thousands. The population burgeoned with United States citizens, Europeans, Middle Easterns, Chinese and other immigrants during the great California gold rush. By the time of California's application for statehood in 1850, the settler population of California had multiplied to 100,000. By 1854, more than 300,000 settlers had come.[65] Between 1847 and 1870, the population of San Francisco increased from 500 to 150,000.[66]

The seat of government for California under Spanish and later Mexican rule had been located in Monterey from 1777 until 1845.[48] Pio Pico, the last Mexican governor of Alta California, had briefly moved the capital to Los Angeles in 1845. The United States consulate had also been located in Monterey, under consul Thomas O. Larkin.

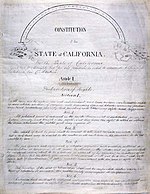

In 1849, a state Constitutional Convention was first held in Monterey. Among the first tasks of the convention was a decision on a location for the new state capital. The first full legislative sessions were held in San Jose (1850–1851). Subsequent locations included Vallejo (1852–1853), and nearby Benicia (1853–1854); these locations eventually proved to be inadequate as well. The capital has been located in Sacramento since 1854[67] with only a short break in 1862 when legislative sessions were held in San Francisco due to flooding in Sacramento. Once the state's Constitutional Convention had finalized its state constitution, it applied to the U.S. Congress for admission to statehood. On September 9, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850, California became a free state and September 9 a state holiday.

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), California sent gold shipments eastward to Washington in support of the Union.[68] However, due to the existence of a large contingent of pro-South sympathizers within the state, the state was not able to muster any full military regiments to send eastwards to officially serve in the Union war effort. Still, several smaller military units within the Union army, such as the "California 100 Company", were unofficially associated with the state of California due to a majority of their members being from California.

At the time of California's admission into the Union, travel between California and the rest of the continental United States had been a time-consuming and dangerous feat. Nineteen years later, and seven years after it was greenlighted by President Lincoln, the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. California was then reachable from the eastern States in a week's time.

Much of the state was extremely well suited to fruit cultivation and agriculture in general. Vast expanses of wheat, other cereal crops, vegetable crops, cotton, and nut and fruit trees were grown (including oranges in Southern California), and the foundation was laid for the state's prodigious agricultural production in the Central Valley and elsewhere.

In the nineteenth century, a large number of migrants from China traveled to the state as part of the Gold Rush or to seek work.[69] Even though the Chinese proved indispensable in building the transcontinental railroad from California to Utah, perceived job competition with the Chinese led to anti-Chinese riots in the state, and eventually the US ended migration from China partially as a response to pressure from California with the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.[70]

California genocide

Under earlier Spanish and Mexican rule, California's original native population had precipitously declined, above all, from Eurasian diseases to which the Indigenous people of California had not yet developed a natural immunity.[73] Under its new American administration, California's first governor Peter Hardeman Burnett instituted policies that have been described as a state-sanctioned policy of elimination of California's indigenous people.[74] Burnett announced in 1851 in his Second Annual Message to the Legislature: "That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected. While we cannot anticipate the result with but painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power and wisdom of man to avert."[75]

As in other American states, indigenous peoples were forcibly removed from their lands by American settlers, like miners, ranchers, and farmers. Although California had entered the American union as a free state, the "loitering or orphaned Indians", were de facto enslaved by their new Anglo-American masters under the 1850 Act for the Government and Protection of Indians.[76] One of these de facto slave auctions was approved by the Los Angeles City Council and occurred for nearly twenty years.[77] There were many massacres in which hundreds of indigenous people were killed by settlers for their land.[78]

Between 1850 and 1860, the California state government paid around 1.5 million dollars (some 250,000 of which was reimbursed by the federal government)[79] to hire militias with the stated purpose of protecting settlers, however these militias perpetrated numerous massacres of indigenous people.[72][78] Indigenous people were also forcibly moved to reservations and rancherias, which were often small and isolated and without enough natural resources or funding from the government to adequately sustain the populations living on them.[72] As a result, settler colonialism was a calamity for indigenous people. Several scholars and Native American activists, including Benjamin Madley and Ed Castillo, have described the actions of the California government as a genocide,[72][71] as well as the 40th governor of California Gavin Newsom.[80] Benjamin Madley estimates that from 1846 to 1873, between 9,492 and 16,092 indigenous people were killed, including between 1,680 and 3,741 killed by the U.S. Army.[71]

1900–present

In the 20th century, thousands of Japanese people migrated to California. The state in 1913 passed the Alien Land Act, excluding Asian immigrants from owning land.[81] During World War II, Japanese Americans in California were interned in concentration camps;[82] in 2020, California apologized.[83]

Migration to California accelerated during the early 20th century with the completion of transcontinental highways like the Route 66. From 1900 to 1965, the population grew from fewer than one million to the greatest in the Union. In 1940, the Census Bureau reported California's population as 6% Hispanic, 2.4% Asian, and 90% non-Hispanic white.[84]

To meet the population's needs, engineering feats like the California and Los Angeles Aqueducts; the Oroville and Shasta Dams; and the Bay and Golden Gate Bridges were built. The state government adopted the California Master Plan for Higher Education in 1960 to develop an efficient system of public education.

Meanwhile, attracted to the mild Mediterranean climate, cheap land, and the state's variety of geography, filmmakers established the studio system in Hollywood in the 1920s. California manufactured 9% of US armaments produced during World War II, ranking third behind New York and Michigan.[85] California easily ranked first in production of military ships at drydock facilities in San Diego, Los Angeles, and the San Francisco Bay Area.[86][87][88][89] Due to the hiring opportunities California offered during the conflict, the population multiplied from the immigration it received due to the work in its war factories, military bases, and training facilities.[90] After World War II, California's economy expanded due to strong aerospace and defense industries,[91] whose size decreased following the end of the Cold War.[91][92] Stanford University began encouraging faculty and graduates to stay instead of leaving the state, and develop a high-tech region, now known as Silicon Valley.[93] As a result of this, California is a world center of the entertainment and music industries, of technology, engineering, and the aerospace industry, and as the US center of agricultural production.[94] Just before the Dot Com Bust, California had the fifth-largest economy in the world.[95]

In the mid and late twentieth century, race-related incidents occurred. Tensions between police and African Americans, combined with unemployment and poverty in inner cities, led to riots, such as the 1992 Rodney King riots.[96][97] California was the hub of the Black Panther Party, known for arming African Americans to defend against racial injustice.[98][99] Mexican, Filipino, and other migrant farm workers rallied in the state around Cesar Chavez for better pay in the 1960s and 70s.[100]

During the 20th century, two great disasters happened: the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and 1928 St. Francis Dam flood remain the deadliest in U.S. history.[101]

Although air pollution has been reduced, health problems associated with pollution continue. Brown haze known as "smog" has been substantially abated after federal and state restrictions on automobile exhaust.[102][103] An energy crisis in 2001 led to rolling blackouts, soaring power rates, and the importation of electricity from neighboring states. Southern California Edison and Pacific Gas and Electric Company came under heavy criticism.[104]

Housing prices in urban areas continued to increase; a modest home which in the 1960s cost $25,000 would cost half a million dollars or more in urban areas by 2005. More people commuted longer hours to afford a home in more rural areas while earning larger salaries in the urban areas. Speculators bought houses, expecting to make a huge profit in months, then rolling it over by buying more properties. Mortgage companies were compliant, as people assumed prices would keep rising. The bubble burst in 2007–8 as prices began to crash. Hundreds of billions in property values vanished and foreclosures soared, as financial institutions and investors were badly hurt.[105][106]

In the 21st century, droughts and frequent wildfires attributed to climate change have occurred.[107][108] From 2011 to 2017, a persistent drought was the worst in its recorded history.[109] The 2018 wildfire season was the state's deadliest and most destructive.[110]

One of the first confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United States occurred in California on January 26, 2020.[111][112] A state of emergency was declared in the state on March 4, 2020, and remained in effect until Governor Gavin Newsom ended it in February 2023.[113] A mandatory statewide stay-at-home order was issued on March 19, 2020, which was ended in January 2021.[114]

Cultural and language revitalization efforts among indigenous Californians have progressed among tribes as of 2022.[115][116] Some land returns to indigenous stewardship have occurred.[117][118][119] In 2022, the largest dam removal and river restoration project in US history was announced for the Klamath River, as a win for California tribes.[120][121]

Geography

Covering an area of 163,696 sq mi (423,970 km2), California is the third-largest state in the United States in area, after Alaska and Texas.[122] California is one of the most geographically diverse states in the union and is often geographically bisected into two regions, Southern California, comprising the ten southernmost counties,[123][124] and Northern California, comprising the 48 northernmost counties.[125][126] It is bordered by Oregon to the north, Nevada to the east and northeast, Arizona to the southeast, the Pacific Ocean to the west and shares an international border with the Mexican state of Baja California to the south (with which it makes up part of The Californias region of North America, alongside Baja California Sur).

In the middle of the state lies the California Central Valley, bounded by the Sierra Nevada in the east, the coastal mountain ranges in the west, the Cascade Range to the north and by the Tehachapi Mountains in the south. The Central Valley is California's productive agricultural heartland.

Divided in two by the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, the northern portion, the Sacramento Valley serves as the watershed of the Sacramento River, while the southern portion, the San Joaquin Valley is the watershed for the San Joaquin River. Both valleys derive their names from the rivers that flow through them. With dredging, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin Rivers have remained deep enough for several inland cities to be seaports.

The Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta is a critical water supply hub for the state. Water is diverted from the delta and through an extensive network of pumps and canals that traverse nearly the length of the state, to the Central Valley and the State Water Projects and other needs. Water from the Delta provides drinking water for nearly 23 million people, almost two-thirds of the state's population as well as water for farmers on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley.

Suisun Bay lies at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. The water is drained by the Carquinez Strait, which flows into San Pablo Bay, a northern extension of San Francisco Bay, which then connects to the Pacific Ocean via the Golden Gate strait.

The Channel Islands are located off the Southern coast, while the Farallon Islands lie west of San Francisco.

The Sierra Nevada (Spanish for "snowy range") includes the highest peak in the contiguous 48 states, Mount Whitney, at 14,505 feet (4,421 m).[3][4][note 1] The range embraces Yosemite Valley, famous for its glacially carved domes, and Sequoia National Park, home to the giant sequoia trees, the largest living organisms on Earth, and the deep freshwater lake, Lake Tahoe, the largest lake in the state by volume.

To the east of the Sierra Nevada are Owens Valley and Mono Lake, an essential migratory bird habitat. In the western part of the state is Clear Lake, the largest freshwater lake by area entirely in California. Although Lake Tahoe is larger, it is divided by the California/Nevada border. The Sierra Nevada falls to Arctic temperatures in winter and has several dozen small glaciers, including Palisade Glacier, the southernmost glacier in the United States.

The Tulare Lake was the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River. A remnant of Pleistocene-era Lake Corcoran, Tulare Lake dried up by the early 20th century after its tributary rivers were diverted for agricultural irrigation and municipal water uses.[127]

About 45 percent of the state's total surface area is covered by forests,[128] and California's diversity of pine species is unmatched by any other state. California contains more forestland than any other state except Alaska. Many of the trees in the California White Mountains are the oldest in the world; an individual bristlecone pine is over 5,000 years old.[129][130]

In the south is a large inland salt lake, the Salton Sea. The south-central desert is called the Mojave; to the northeast of the Mojave lies Death Valley, which contains the lowest and hottest place in North America, the Badwater Basin at −279 feet (−85 m).[5] The horizontal distance from the bottom of Death Valley to the top of Mount Whitney is less than 90 miles (140 km). Indeed, almost all of southeastern California is arid, hot desert, with routine extreme high temperatures during the summer. The southeastern border of California with Arizona is entirely formed by the Colorado River, from which the southern part of the state gets about half of its water.

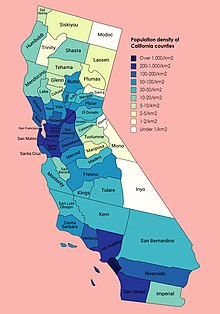

A majority of California's cities are located in either the San Francisco Bay Area or the Sacramento metropolitan area in Northern California; or the Los Angeles area, the Inland Empire, or the San Diego metropolitan area in Southern California. The Los Angeles Area, the Bay Area, and the San Diego metropolitan area are among several major metropolitan areas along the California coast.

As part of the Ring of Fire, California is subject to tsunamis, floods, droughts, Santa Ana winds, wildfires, and landslides on steep terrain; California also has several volcanoes. It has many earthquakes due to several faults running through the state, the largest being the San Andreas Fault. About 37,000 earthquakes are recorded each year; most are too small to be felt.[131] Among Americans at risk of serious harm from a major earthquake, two-thirds of that population are residents of California.[13]

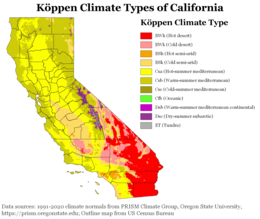

Climate

Most of the state has a Mediterranean climate. The cool California Current offshore often creates summer fog near the coast. Farther inland, there are colder winters and hotter summers. The maritime moderation results in the shoreline summertime temperatures of Los Angeles and San Francisco being the coolest of all major metropolitan areas of the United States and uniquely cool compared to areas on the same latitude in the interior and on the east coast of the North American continent. Even the San Diego shoreline bordering Mexico is cooler in summer than most areas in the contiguous United States. Just a few miles inland, summer temperature extremes are significantly higher, with downtown Los Angeles being several degrees warmer than at the coast. The same microclimate phenomenon is seen in the climate of the Bay Area, where areas sheltered from the ocean experience significantly hotter summers and colder winters in contrast with nearby areas closer to the ocean.[132][133][134]

Northern parts of the state have more rain than the south. California's mountain ranges also influence the climate: some of the rainiest parts of the state are west-facing mountain slopes. Coastal northwestern California has a temperate climate, and the Central Valley has a Mediterranean climate but with greater temperature extremes than the coast. The high mountains, including the Sierra Nevada, have an alpine climate with snow in winter and mild to moderate heat in summer.

California's mountains produce rain shadows on the eastern side, creating extensive deserts. The higher elevation deserts of eastern California have hot summers and cold winters, while the low deserts east of the Southern California mountains have hot summers and nearly frostless mild winters. Death Valley, a desert with large expanses below sea level, is considered the hottest location in the world; the highest temperature in the world,[135][136] 134 °F (56.7 °C), was recorded there on July 10, 1913. The lowest temperature in California was −45 °F (−43 °C) on January 20, 1937, in Boca.[137]

The table below lists average temperatures for January and August in a selection of places throughout the state; some highly populated and some not. This includes the relatively cool summers of the Humboldt Bay region around Eureka, the extreme heat of Death Valley, and the mountain climate of Mammoth in the Sierra Nevada.

| Location | August (°F) |

August (°C) |

January (°F) |

January (°C) |

Annual precipitation (mm/in) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles | 83/64 | 29/18 | 66/48 | 20/8 | 377/15 |

| LAX/LA Beaches | 75/64 | 23/18 | 65/49 | 18/9 | 326/13 |

| San Diego | 76/67 | 24/19 | 65/49 | 18/9 | 262/10 |

| San Jose | 82/58 | 27/14 | 58/42 | 14/5 | 401/16 |

| San Francisco | 67/54 | 20/12 | 56/46 | 14/8 | 538/21 |

| Fresno | 97/66 | 34/19 | 55/38 | 12/3 | 292/11 |

| Sacramento | 91/58 | 33/14 | 54/39 | 12/3 | 469/18 |

| Oakland | 73/58 | 23/14 | 58/44 | 14/7 | 588/23 |

| Bakersfield | 96/69 | 36/21 | 56/39 | 13/3 | 165/7 |

| Riverside | 94/60 | 35/18 | 67/39 | 19/4 | 260/10 |

| Eureka | 62/53 | 16/11 | 54/41 | 12/5 | 960/38 |

| Death Valley | 115/86 | 46/30 | 67/40 | 19/4 | 60/2 |

| Mammoth Lakes | 77/45 | 25/7 | 40/15 | 4/ −9 | 583/23 |

The wide range of climates leads to a high demand for water. Over time, droughts have been increasing due to climate change and overextraction,[139] becoming less seasonal and more year-round, further straining California's electricity supply[140] and water security[141][142] and having an impact on California business, industry, and agriculture.[143]

In 2022, a new state program was created in collaboration with indigenous peoples of California to revive the practice of controlled burns as a way of clearing excessive forest debris and making landscapes more resilient to wildfires. Native American use of fire in ecosystem management was outlawed in 1911, yet has now been recognized.[14]

Ecology

California is one of the ecologically richest and most diverse parts of the world, and includes some of the most endangered ecological communities. California is part of the Nearctic realm and spans a number of terrestrial ecoregions.[144]

California's large number of endemic species includes relict species, which have died out elsewhere, such as the Catalina ironwood (Lyonothamnus floribundus). Many other endemics originated through differentiation or adaptive radiation, whereby multiple species develop from a common ancestor to take advantage of diverse ecological conditions such as the California lilac (Ceanothus).[citation needed] Many California endemics have become endangered, as urbanization, logging, overgrazing, and the introduction of exotic species have encroached on their habitat.

Flora and fauna

California boasts several superlatives in its collection of flora: the largest trees, the tallest trees, and the oldest trees. California's native grasses are perennial plants,[145] and there are close to hundred succulent species native to the state.[citation needed] After European contact, these were generally replaced by invasive species of European annual grasses; and, in modern times, California's hills turn a characteristic golden-brown in summer.[146]

Because California has the greatest diversity of climate and terrain, the state has six life zones which are the lower Sonoran Desert; upper Sonoran (foothill regions and some coastal lands), transition (coastal areas and moist northeastern counties); and the Canadian, Hudsonian, and Arctic Zones, comprising the state's highest elevations.[147]

Plant life in the dry climate of the lower Sonoran zone contains a diversity of native cactus, mesquite, and paloverde. The Joshua tree is found in the Mojave Desert. Flowering plants include the dwarf desert poppy and a variety of asters. Fremont cottonwood and valley oak thrive in the Central Valley. The upper Sonoran zone includes the chaparral belt, characterized by forests of small shrubs, stunted trees, and herbaceous plants. Nemophila, mint, Phacelia, Viola, and the California poppy (Eschscholzia californica, the state flower) also flourish in this zone, along with the lupine, more species of which occur here than anywhere else in the world.[147]

The transition zone includes most of California's forests with the redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and the "big tree" or giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum), among the oldest living things on earth (some are said to have lived at least 4,000 years). Tanbark oak, California laurel, sugar pine, madrona, broad-leaved maple, and Douglas-fir also grow here. Forest floors are covered with swordfern, alumnroot, barrenwort, and trillium, and there are thickets of huckleberry, azalea, elder, and wild currant. Characteristic wild flowers include varieties of mariposa, tulip, and tiger and leopard lilies.[148]

The high elevations of the Canadian zone allow the Jeffrey pine, red fir, and lodgepole pine to thrive. Brushy areas are abundant with dwarf manzanita and ceanothus; the unique Sierra puffball is also found here. Right below the timberline, in the Hudsonian zone, the whitebark, foxtail, and silver pines grow. At about 10,500 feet (3,200 m), begins the Arctic zone, a treeless region whose flora include a number of wildflowers, including Sierra primrose, yellow columbine, alpine buttercup, and alpine shooting star.[147][149]

Palm trees are a well-known feature of California, particularly in Southern California and Los Angeles; many species have been imported, though the Washington filifera (commonly known as the California fan palm) is native to the state, mainly growing in the Colorado Desert oases.[150] Other common plants that have been introduced to the state include the eucalyptus, acacia, pepper tree, geranium, and Scotch broom. The species that are federally classified as endangered are the Contra Costa wallflower, Antioch Dunes evening primrose, Solano grass, San Clemente Island larkspur, salt marsh bird's beak, McDonald's rock-cress, and Santa Barbara Island liveforever. As of December 1997[update], 85 plant species were listed as threatened or endangered.[147]

In the deserts of the lower Sonoran zone, the mammals include the jackrabbit, kangaroo rat, squirrel, and opossum. Common birds include the owl, roadrunner, cactus wren, and various species of hawk. The area's reptilian life include the sidewinder viper, desert tortoise, and horned toad. The upper Sonoran zone boasts mammals such as the antelope, brown-footed woodrat, and ring-tailed cat. Birds unique to this zone are the California thrasher, bushtit, and California condor.[147][151][152][153]

In the transition zone, there are Colombian black-tailed deer, black bears, gray foxes, cougars, bobcats, and Roosevelt elk. Reptiles such as the garter snakes and rattlesnakes inhabit the zone. In addition, amphibians such as the water puppy and redwood salamander are common too. Birds such as the kingfisher, chickadee, towhee, and hummingbird thrive here as well.[147][154]

The Canadian zone mammals include the mountain weasel, snowshoe hare, and several species of chipmunks. Conspicuous birds include the blue-fronted jay, mountain chickadee, hermit thrush, American dipper, and Townsend's solitaire. As one ascends into the Hudsonian zone, birds become scarcer. While the gray-crowned rosy finch is the only bird native to the high Arctic region, other bird species such as Anna's hummingbird and Clark's nutcracker. Principal mammals found in this region include the Sierra coney, white-tailed jackrabbit, and the bighorn sheep. As of April 2003[update], the bighorn sheep was listed as endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The fauna found throughout several zones are the mule deer, coyote, mountain lion, northern flicker, and several species of hawk and sparrow.[147]

Aquatic life in California thrives, from the state's mountain lakes and streams to the rocky Pacific coastline. Numerous trout species are found, among them rainbow, golden, and cutthroat. Migratory species of salmon are common as well. Deep-sea life forms include sea bass, yellowfin tuna, barracuda, and several types of whale. Native to the cliffs of northern California are seals, sea lions, and many types of shorebirds, including migratory species.[147]

As of April 2003[update], 118 California animals were on the federal endangered list; 181 plants were listed as endangered or threatened. Endangered animals include the San Joaquin kitfox, Point Arena mountain beaver, Pacific pocket mouse, salt marsh harvest mouse, Morro Bay kangaroo rat (and five other species of kangaroo rat), Amargosa vole, California least tern, California condor, loggerhead shrike, San Clemente sage sparrow, San Francisco garter snake, five species of salamander, three species of chub, and two species of pupfish. Eleven butterflies are also endangered[155] and two that are threatened are on the federal list.[156][157] Among threatened animals are the coastal California gnatcatcher, Paiute cutthroat trout, southern sea otter, and northern spotted owl. California has a total of 290,821 acres (1,176.91 km2) of National Wildlife Refuges.[147] As of September 2010[update], 123 California animals were listed as either endangered or threatened on the federal list.[158] Also, as of the same year[update], 178 species of California plants were listed either as endangered or threatened on this federal list.[158]

Rivers

The most prominent river system within California is formed by the Sacramento River and San Joaquin River, which are fed mostly by snowmelt from the west slope of the Sierra Nevada, and respectively drain the north and south halves of the Central Valley. The two rivers join in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, flowing into the Pacific Ocean through San Francisco Bay. Many major tributaries feed into the Sacramento–San Joaquin system, including the Pit River, Feather River and Tuolumne River.

The Klamath and Trinity Rivers drain a large area in far northwestern California. The Eel River and Salinas River each drain portions of the California coast, north and south of San Francisco Bay, respectively. The Mojave River is the primary watercourse in the Mojave Desert, and the Santa Ana River drains much of the Transverse Ranges as it bisects Southern California. The Colorado River forms the state's southeast border with Arizona.

Most of California's major rivers are dammed as part of two massive water projects: the Central Valley Project, providing water for agriculture in the Central Valley, and the California State Water Project diverting water from Northern to Southern California. The state's coasts, rivers, and other bodies of water are regulated by the California Coastal Commission.

Regions

California is traditionally separated into Northern California and Southern California, divided by a straight border which runs across the state, separating the northern 48 counties from the southern 10 counties. Despite the persistence of the northern-southern divide, California is more precisely divided into many regions, multiple of which stretch across the northern-southern divide.

- Major divisions

- Regions

Cities and towns

The state has 483 incorporated cities and towns,[159] of which 461 are cities and 22 are towns. Under California law, the terms "city" and "town" are explicitly interchangeable; the name of an incorporated municipality in the state can either be "City of (Name)" or "Town of (Name)".[160]

Sacramento became California's first incorporated city on February 27, 1850.[161] San Jose, San Diego, and Benicia tied for California's second incorporated city, each receiving incorporation on March 27, 1850.[162][163][164] Mountain House became the state's most recent and 483rd incorporated municipality on July 1, 2024.[159] The majority of these cities and towns are within one of five metropolitan areas: the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area, the San Francisco Bay Area, the Riverside-San Bernardino Area, the San Diego metropolitan area, or the Sacramento metropolitan area.

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Los Angeles  San Diego |

1 | Los Angeles | Los Angeles | 3,898,747 | 11 | Stockton | San Joaquin | 320,804 | San Jose  San Francisco |

| 2 | San Diego | San Diego | 1,386,932 | 12 | Riverside | Riverside | 314,998 | ||

| 3 | San Jose | Santa Clara | 1,013,240 | 13 | Santa Ana | Orange | 310,227 | ||

| 4 | San Francisco | San Francisco | 873,965 | 14 | Irvine | Orange | 307,670 | ||

| 5 | Fresno | Fresno | 542,107 | 15 | Chula Vista | San Diego | 275,487 | ||

| 6 | Sacramento | Sacramento | 524,943 | 16 | Fremont | Alameda | 230,504 | ||

| 7 | Long Beach | Los Angeles | 466,742 | 17 | Santa Clarita | Los Angeles | 228,673 | ||

| 8 | Oakland | Alameda | 440,646 | 18 | San Bernardino | San Bernardino | 222,101 | ||

| 9 | Bakersfield | Kern | 403,455 | 19 | Modesto | Stanislaus | 218,464 | ||

| 10 | Anaheim | Orange | 346,824 | 20 | Moreno Valley | Riverside | 208,634 | ||

| CA rank | U.S. rank | Metropolitan statistical area[166] | 2020 census[165] | 2010 census[165] | Change | Counties[166] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA MSA | 13,200,998 | 12,828,837 | +2.90% | Los Angeles, Orange |

| 2 | 12 | San Francisco-Oakland-Hayward, CA MSA | 4,749,008 | 4,335,391 | +9.54% | Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Francisco, San Mateo |

| 3 | 13 | Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA MSA | 4,599,839 | 4,224,851 | +8.88% | Riverside, San Bernardino |

| 4 | 17 | San Diego-Carlsbad, CA MSA | 3,298,634 | 3,095,313 | +6.57% | San Diego |

| 5 | 26 | Sacramento–Roseville–Arden-Arcade, CA MSA | 2,397,382 | 2,149,127 | +11.55% | El Dorado, Placer, Sacramento, Yolo |

| 6 | 35 | San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA MSA | 2,000,468 | 1,836,911 | +8.90% | San Benito, Santa Clara |

| 7 | 56 | Fresno, CA MSA | 1,008,654 | 930,450 | +8.40% | Fresno |

| 8 | 62 | Bakersfield, CA MSA | 909,235 | 839,631 | +8.29% | Kern |

| 9 | 70 | Oxnard-Thousand Oaks-Ventura, CA MSA | 843,843 | 823,318 | +2.49% | Ventura |

| 10 | 75 | Stockton-Lodi, CA MSA | 779,233 | 685,306 | +13.71% | San Joaquin |

| CA rank | U.S. rank | Combined statistical area[165] | 2020 census[165] | 2010 census[165] | Change | Counties[166] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Los Angeles-Long Beach, CA Combined Statistical Area | 18,644,680 | 17,877,006 | +4.29% | Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, Ventura |

| 2 | 4 | San Jose-San Francisco-Oakland, CA Combined Statistical Area | 9,714,023 | 8,923,942 | +8.85% | Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Merced, Napa, San Benito, San Francisco, San Joaquin, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, Solano, Sonoma, Stanislaus |

| 3 | 23 | Sacramento-Roseville, CA Combined Statistical Area | 2,680,831 | 2,414,783 | +11.02% | El Dorado, Nevada, Placer, Sacramento, Sutter, Yolo, Yuba |

| 4 | 45 | Fresno-Madera, CA Combined Statistical Area | 1,317,395 | 1,234,297 | +6.73% | Fresno, Kings, Madera |

| 5 | 125 | Redding-Red Bluff, CA Combined Statistical Area | 247,984 | 240,686 | +3.03% | Shasta, Tehama |

Demographics

Population

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 92,597 | — | |

| 1860 | 379,994 | 310.4% | |

| 1870 | 560,247 | 47.4% | |

| 1880 | 864,694 | 54.3% | |

| 1890 | 1,213,398 | 40.3% | |

| 1900 | 1,485,053 | 22.4% | |

| 1910 | 2,377,549 | 60.1% | |

| 1920 | 3,426,861 | 44.1% | |

| 1930 | 5,677,251 | 65.7% | |

| 1940 | 6,907,387 | 21.7% | |

| 1950 | 10,586,223 | 53.3% | |

| 1960 | 15,717,204 | 48.5% | |

| 1970 | 19,953,134 | 27.0% | |

| 1980 | 23,667,902 | 18.6% | |

| 1990 | 29,760,021 | 25.7% | |

| 2000 | 33,871,648 | 13.8% | |

| 2010 | 37,253,956 | 10.0% | |

| 2020 | 39,538,223 | 6.1% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 38,940,231 | −1.5% | |

| Sources: 1790–1990, 2000, 2010, 2020, 2023[167][168][169][6] Chart does not include indigenous population figures. Studies indicate that the Native American population in California in 1850 was close to 150,000 before declining to 15,000 by 1900.[170] | |||

Presently, close to one out of every nine United States residents live in California.[171][172] The United States Census Bureau reported that the population of California was 39.54 million on April 1, 2020, a 6.13% increase since the 2010 census.[169] During that decade, the state's population grew more slowly than the rest of the nation, resulting in the loss of one seat on the US House of Representatives, the first loss in its entire history.[171] The estimated state population in 2023 was 38.94 million.[172] For well over a century (1900–2020), California experienced steady population growth. Even while the rate of growth began to slow by the 1990s, some growth continued into the first two decades of the 21st century; California added an average of around 400,000 people per year to its population during the period 1940–2020.[173][174][175] Then in 2020, the state began to experience population declines continuing every year, attributable mostly to moves out of state but also due to declining birth rates, COVID-19 pandemic deaths, and less internal migration from other states to California.[171][176] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, between 2021 and 2022, 818,000 California residents moved out of state[177] with emigrants listing high cost of living,[178] high taxes,[179][180] and a difficult business environment as the motivation.[180] The net loss of population in California between July 2020 and July 2023 was 433,000.[171]

The Greater Los Angeles Area is the second-largest metropolitan area in the United States (U.S.), while Los Angeles is the second-largest city in the U.S. Conversely, San Francisco is the most densely-populated city in California and one of the most densely populated cities in the U.S.. Also, Los Angeles County has held the title of most populous U.S. county for decades, and it alone is more populous than 42 U.S. states.[181][182] Including Los Angeles, four of the top 20 most populous cities in the U.S. are in California: Los Angeles (2nd), San Diego (8th), San Jose (10th), and San Francisco (17th). The center of population of California is located four miles west-southwest of the city of Shafter, Kern County.[note 3]

As of 2019, California ranked second among states by life expectancy, with a life expectancy of 80.9 years.[184]

Starting in the year 2010, for the first time since the California Gold Rush, California-born residents made up the majority of the state's population.[185] Along with the rest of the United States, California's immigration pattern has also shifted over the course of the late 2000s to early 2010s.[186] Immigration from Latin American countries has dropped significantly with most immigrants now coming from Asia.[187] In total for 2011, there were 277,304 immigrants. Fifty-seven percent came from Asian countries versus 22% from Latin American countries.[187] Net immigration from Mexico, previously the most common country of origin for new immigrants, has dropped to zero / less than zero since more Mexican nationals are departing for their home country than immigrating.[186]

The state's population of undocumented immigrants has been shrinking in recent years, due to increased enforcement and decreased job opportunities for lower-skilled workers.[188] The number of migrants arrested attempting to cross the Mexican border in the Southwest decreased from a high of 1.1 million in 2005 to 367,000 in 2011.[189] Despite these recent trends, illegal aliens constituted an estimated 7.3 percent of the state's population, the third highest percentage of any state in the country,[190][note 4] totaling nearly 2.6 million.[191] In particular, illegal immigrants tended to be concentrated in Los Angeles, Monterey, San Benito, Imperial, and Napa Counties—the latter four of which have significant agricultural industries that depend on manual labor.[192] More than half of illegal immigrants originate from Mexico.[191] The state of California and some California cities, including Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Francisco,[193] have adopted sanctuary policies.[194]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 171,521 homeless people in California.[195][196]

Race and ethnicity

| Race and ethnicity[197] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic or Latino[note 5] | — | 39.4% | ||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 34.7% | 38.3% | ||

| Asian (non-Hispanic) | 15.1% | 17.0% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 5.4% | 6.4% | ||

| Native American (non-Hispanic) | 0.4% | 1.3% | ||

| Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic) | 0.3% | 0.7% | ||

| Other (non-Hispanic) | 0.6% | 1.3% | ||

| Racial composition | 1950[198] | 1960[198] | 1970[198] | 1980[198] | 1990[198] | 2000[199] | 2010[200] | 2020[201] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 93.7% | 92% | 89% | 76.2% | 69% | 59.6% | 57.6% | 41.2% |

| Black | 4.4% | 5.6% | 7% | 7.7% | 7.4% | 6.7% | 6.2% | 5.6% |

| Asian | 1.7% | 2% | 2.8% | 5.3% | 9.6% | 10.9% | 13% | 15.4% |

| Native | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.9% | 0.8% | 1% | 1% | 1.6% |

| Native Hawaiian and | — | — | — | — | — | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| Other race | — | 0.1% | 0.7% | 10% | 13.2% | 16.8% | 17% | 21.2% |

| Two or more races | — | — | — | — | — | 4.8% | 4.9% | 14.6% |

| Hispanic or Latino | — | — | 13.7% | 19.2% | 25.8% | 32.4% | 37.6% | 39.4% |

| Non-Hispanic white | — | — | 76.3% | 66.6% | 57.2% | 46.7% | 40.2% | 34.7% |

According to the United States Census Bureau in 2022 the population self-identified as (alone or in combination): 56.5% White (including Hispanic Whites),[202] 33.7% non-Hispanic white,[203] 18.1% Asian,[204] 7.3% Black or African American,[205] 3.2% Native American and Alaska Native,[206] 0.9% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander,[207] and 34.3% some other race.[208] These numbers add up to more than 100% because respondents can select multiple racial identities. 19% of Californians identified as two or more races in 2022, although excluding respondents who selected "some other race", only 5% identified as two or more races.[209]

By ethnicity, in 2018 the population was 60.7% non-Hispanic (of any race) and 39.3% Hispanic or Latino (of any race). Hispanics are the largest single ethnic group in California.[210] Non-Hispanic whites constituted 36.8% of the state's population.[210] Californios are the Hispanic residents native to California, who make up the Spanish-speaking community that has existed in California since 1542, of varying Mexican American/Chicano, Criollo Spaniard, and Mestizo origin.[211] However, they make up only a small part of California's Hispanic population today, estimated at 500,000. California has the largest Mexican, Salvadoran, and Guatemalan population, together making up over 90% of the state's Latino population.[212]

According to 2022 estimates from the American Community Survey, 32.4% of the population had Mexican ancestry, 6.6% had German ancestry, 6.1% had English ancestry, 5.6% had Irish ancestry, 4.9% had Chinese ancestry, 4.3% had Filipino ancestry, 4% had Central American ancestry (Mostly Salvadoran and Guatemalan), 3.4% had Italian ancestry, 2.8% listed themselves as American, and 2.5% had Indian ancestry.[213][214][215]

As of 2011[update], 75.1% of California's population younger than age 1 were minorities, meaning they had at least one parent who was not non-Hispanic white (white Hispanics are counted as minorities).[216]

In terms of total numbers, California has the largest population of White Americans in the United States, an estimated 22,200,000 residents including people identifying as white in combination with any other race. The state has the 5th largest population of African Americans in the United States, an estimated 2,250,000 residents. California's Asian American population is estimated at 7.1 million, constituting a third of the nation's total. California's Native American population of 504,000 is the most of any state, with 103,030 identifying as Non-Hispanic and belonging mostly to the Indigenous peoples of California.[217][218] Most of the state's Native American population identifies as Hispanic and belongs to Indigenous Mexican or Central American ethnic groups, including 185,200 identifying as Mexican American Indian and 67,904 identifying as Central American Indian.[219]

According to estimates from 2011, California has the largest minority population in the United States by numbers, making up 60% of the state population.[220] Over the past 25 years, the population of non-Hispanic whites has declined, while Hispanic and Asian populations have grown. Between 1970 and 2011, non-Hispanic whites declined from 80% of the state's population to 40%, while Hispanics grew from 32% in 2000 to 38% in 2011.[221] It is currently projected that Hispanics will rise to 49% of the population by 2060, primarily due to domestic births rather than immigration.[222] With the decline of immigration from Latin America, Asian Americans now constitute the fastest growing racial/ethnic group in California; this growth is primarily driven by immigration from China, India, and the Philippines, respectively.[223]

Most of California's immigrant population are born in Mexico (3.9 million), the Philippines (825,200), China (768,400), India (556,500), and Vietnam (502,600).[224]

California has the largest multiracial population in the United States.[225] Mexican is the most common ancestry in California, followed by English, German, and Irish.[226]

Languages

| Language | Population (as of 2021[update])[227] |

% |

|---|---|---|

| English | 20,763,638 | 56.08% |

| Spanish | 10,434,308 | 28.18% |

| Chinese | 1,244,445 | 3.36% |

| Tagalog | 757,488 | 2.05% |

| Vietnamese | 544,046 | 1.47% |

| Korean | 356,901 | 0.96% |

| Arabic | 231,612 | 0.63% |

| Persian | 221,650 | 0.6% |

| Armenian | 211,614 | 0.57% |

| Hindi | 208,148 | 0.56% |

| Russian | 178,176 | 0.48% |

| Punjabi | 156,763 | 0.42% |

| Japanese | 135,992 | 0.37% |

| French | 126,371 | 0.34% |

English serves as California's de jure and de facto official language. According to the 2021 American Community Survey conducted by the United States Census Bureau, 56.08% (20,763,638) of California residents age 5 and older spoke only English at home, while 43.92% spoke another language at home. 60.35% of people who speak a language other than English at home are able to speak English "well" or "very well", with this figure varying significantly across the different linguistic groups.[227] Like most U.S. states (32 out of 50), California law enshrines English as its official language, and has done so since the passage of Proposition 63 by California voters in 1986. Various government agencies do, and are often required to, furnish documents in the various languages needed to reach their intended audiences.[228][229][230]

Spanish is the most commonly spoken language in California, behind English, spoken by 28.18% (10,434,308) of the population (in 2021).[227] The Spanish language has been spoken in California since 1542 and is deeply intertwined with California's cultural landscape and history.[231][232][233] Spanish was the official administrative language of California through the Spanish and Mexican eras, until 1848. Following the U.S. Conquest of California and the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, the U.S. Government guaranteed the rights of Spanish-speaking Californians. The first Constitution of California was written in both languages at the Monterey Constitutional Convention of 1849 and protected the rights of Spanish speakers to use their language in government proceedings and mandating that all government documents be published in both English and Spanish.[234]

Despite the initial recognition of Spanish by early American governments in California, the revised 1879 constitution stripped the rights of Spanish speakers and the official status of Spanish.[235] The growth of the English-only movement by the mid-20th century led to the passage of 1986 California Proposition 63, which enshrined English as the only official language in California and ended Spanish language instruction in schools.[236] 2016 California Proposition 58 reversed the prohibition on bilingual education, though there are still many barriers to the proliferation of Spanish bilingual education, including a shortage of teachers and lack of funding.[237][236][238] The government of California has since made efforts to promote Spanish language access and bilingual education,[239][240] as have private educational institutions in California.[241] Many businesses in California promote the usage of Spanish by their employees, to better serve both California's Hispanic population and the larger Spanish-speaking world.[242][243]

California has historically been one of the most linguistically diverse areas in the world, with more than 70 indigenous languages derived from 64 root languages in six language families.[244][245] A survey conducted between 2007 and 2009 identified 23 different indigenous languages among California farmworkers.[246] All of California's indigenous languages are endangered, although there are now efforts toward language revitalization.[note 6] California has the highest concentration nationwide of Chinese, Vietnamese and Punjabi speakers.

As a result of the state's increasing diversity and migration from other areas across the country and around the globe, linguists began noticing a noteworthy set of emerging characteristics of spoken American English in California since the late 20th century. This variety, known as California English, has a vowel shift and several other phonological processes that are different from varieties of American English used in other regions of the United States.[247]

Religion

Religious self-identification, per Public Religion Research Institute's 2021 American Values Survey[248]

The largest religious denominations by number of adherents as a percentage of California's population in 2014 were the Catholic Church with 28 percent, Evangelical Protestants with 20 percent, and Mainline Protestants with 10 percent. Together, all kinds of Protestants accounted for 32 percent. Those unaffiliated with any religion represented 27 percent of the population. The breakdown of other religions is 1% Muslim, 2% Hindu and 2% Buddhist.[249] This is a change from 2008, when the population identified their religion with the Catholic Church with 31 percent; Evangelical Protestants with 18 percent; and Mainline Protestants with 14 percent. In 2008, those unaffiliated with any religion represented 21 percent of the population. The breakdown of other religions in 2008 was 0.5% Muslim, 1% Hindu and 2% Buddhist.[250] The American Jewish Year Book placed the total Jewish population of California at about 1,194,190 in 2006.[251] According to the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) the largest denominations by adherents in 2010 were the Catholic Church with 10,233,334; The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 763,818; and the Southern Baptist Convention with 489,953.[252]

California has a large Catholic population due to the large numbers of Mexicans and Central Americans living within its borders. California has twelve dioceses and two archdioceses, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and the Archdiocese of San Francisco, the former being the largest archdiocese in the United States.

A Pew Research Center survey revealed that California is somewhat less religious than the rest of the states: 62 percent of Californians say they are "absolutely certain" of their belief in God, while in the nation 71 percent say so. The survey also revealed 48 percent of Californians say religion is "very important", compared to 56 percent nationally.[254]

Culture

The culture of California is a Western culture and has its modern roots in the culture of the United States, but also, historically, many Hispanic Californio and Mexican influences. As a border and coastal state, California culture has been greatly influenced by several large immigrant populations, especially those from Latin America and Asia.[255]

California has long been a subject of interest in the public mind and has often been promoted by its boosters as a kind of paradise. In the early 20th century, fueled by the efforts of state, the building projects during the Great Depression and local boosters, many Americans saw the Golden State as an ideal resort destination, sunny and dry all year round with easy access to the ocean and mountains. In the 1960s, popular music groups such as the Beach Boys promoted the image of Californians as laid-back, tanned beach-goers.

Media and entertainment

Hollywood and the rest of the Los Angeles area is a major global center for entertainment, with the U.S. film industry's "Big Five" major film studios (Columbia, Disney, Paramount, Universal, and Warner Bros.) as well as many minor film studios being based in or around the area. Many animation studios are also headquartered in the state.

The four major American television commercial broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox) as well as other networks all have production facilities and offices in the state. All the four major commercial broadcast networks, plus the two major Spanish-language networks (Telemundo and Univision) each have at least three owned-and-operated TV stations in California, including at least one in Los Angeles and at least one in San Francisco.[note 7]

One of the oldest radio stations in the United States still in existence, KCBS (AM) in the San Francisco Bay Area, was founded in 1909. Universal Music Group, one of the "Big Four" record labels, is based in Santa Monica, while Warner Records is based in Los Angeles. Many independent record labels, such as Mind of a Genius Records, are also headquartered in the state. California is also the birthplace of several international music genres, including the Bakersfield sound, Bay Area thrash metal, alternative rock, g-funk, nu metal, glam metal, thrash metal, psychedelic rock, stoner rock, punk rock, hardcore punk, metalcore, pop punk, surf music, third wave ska, west coast hip hop, west coast jazz, jazz rap, and many other genres. Other genres such as pop rock, indie rock, hard rock, hip hop, pop, rock, rockabilly, country, heavy metal, grunge, new wave and disco were popularized in the state. In addition, many British bands, such as Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Black Sabbath, and the Rolling Stones settled in the state after becoming internationally famous.

As the home of Silicon Valley, the Bay Area is the headquarters of several prominent internet media, social media, and other technology companies. Three of the "Big Five" technology companies (Apple, Meta, and Google) are based in the area as well as other services such as Netflix, Pandora Radio, Twitter, Yahoo!, and YouTube. Other prominent companies that are headquartered here include HP inc. and Intel. Microsoft and Amazon also have offices in the area.

California, particularly Southern California,[256] is considered the birthplace of modern car culture.[257]

Several fast food, fast casual, and casual dining chains were also founded California, including some that have since expanded internationally like California Pizza Kitchen, Denny's, IHOP, McDonald's, Panda Express, and Taco Bell.

Sports

California has nineteen major professional sports league franchises, far more than any other state. The San Francisco Bay Area has six major league teams spread in its three major cities: San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland, while the Greater Los Angeles Area is home to ten major league franchises. San Diego and Sacramento each have one major league team. The NFL Super Bowl has been hosted in California 12 times at five different stadiums: Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, the Rose Bowl, Stanford Stadium, Levi's Stadium, and San Diego Stadium. A thirteenth, Super Bowl LVI, was held at SoFi Stadium in Inglewood on February 13, 2022.[258]

California has long had many respected collegiate sports programs. California is home to the oldest college bowl game, the annual Rose Bowl, among others.

The NFL has three teams in the state: the Los Angeles Rams, Los Angeles Chargers, and San Francisco 49ers.

MLB has five teams in the state: the San Francisco Giants, Oakland Athletics, Los Angeles Dodgers, Los Angeles Angels, and San Diego Padres.[259]

The NBA has four teams in the state: the Golden State Warriors, Los Angeles Clippers, Los Angeles Lakers, and Sacramento Kings. Additionally, the WNBA also has one team in the state: the Los Angeles Sparks.

The NHL has three teams in the state: the Anaheim Ducks, Los Angeles Kings, and San Jose Sharks.

MLS has three teams in the state: the Los Angeles Galaxy, San Jose Earthquakes, and Los Angeles FC.

MLR has one team in the state: the San Diego Legion.

California is the only U.S. state to have hosted both the Summer and Winter Olympics. The 1932 and 1984 summer games were held in Los Angeles. Squaw Valley Ski Resort (now Palisades Tahoe) in the Lake Tahoe region hosted the 1960 Winter Olympics. Los Angeles will host the 2028 Summer Olympics, marking the fourth time that California will have hosted the Olympic Games.[260] Multiple games during the 1994 FIFA World Cup took place in California, with the Rose Bowl hosting eight matches (including the final), while Stanford Stadium hosted six matches.

In addition to the Olympic games, California also hosts the California State Games.

Many sports, such as surfing, snowboarding, and skateboarding, were invented in California, while others like volleyball, beach soccer, and skiing were popularized in the state.

Other sports that are big in the state include golf, rodeo, tennis, mountain climbing, marathon running, horse racing, bowling, mixed martial arts, boxing, and motorsports, especially NASCAR and Formula One.

| Team | Sport | League |

|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles Rams | American football | National Football League (NFL) |

| Los Angeles Chargers | American football | National Football League |

| San Francisco 49ers | American football | National Football League |

| Los Angeles Dodgers | Baseball | Major League Baseball (MLB) |

| Los Angeles Angels | Baseball | Major League Baseball |

| Oakland Athletics | Baseball | Major League Baseball |

| San Diego Padres | Baseball | Major League Baseball |

| San Francisco Giants | Baseball | Major League Baseball |

| Golden State Warriors | Basketball | National Basketball Association (NBA) |

| Los Angeles Clippers | Basketball | National Basketball Association |

| Los Angeles Lakers | Basketball | National Basketball Association |

| Sacramento Kings | Basketball | National Basketball Association |

| Los Angeles Sparks | Basketball | Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA) |

| Anaheim Ducks | Ice hockey | National Hockey League (NHL) |

| Los Angeles Kings | Ice hockey | National Hockey League |

| San Jose Sharks | Ice hockey | National Hockey League |

| Los Angeles Galaxy | Soccer | Major League Soccer (MLS) |

| San Jose Earthquakes | Soccer | Major League Soccer |

| Los Angeles Football Club | Soccer | Major League Soccer |

| Angel City FC | Soccer | National Women's Soccer League (NWSL) |

| San Diego Wave FC | Soccer | National Women's Soccer League |

| San Diego Legion | Rugby union | Major League Rugby |

Education

California has the most school students in the country, with over 6.2 million in the 2005–06 school year, giving California more students in school than 36 states have in total population and one of the highest projected enrollments in the country.[261] Public secondary education consists of high schools that teach elective courses in trades, languages, and liberal arts with tracks for gifted, college-bound and industrial arts students. California's public educational system is supported by a unique constitutional amendment that requires a minimum annual funding level for grades K–12 and community colleges that grows with the economy and student enrollment figures.[262]

In 2016, California's K–12 public school per-pupil spending was ranked 22nd in the nation ($11,500 per student vs. $11,800 for the U.S. average).[263]

For 2012, California's K–12 public schools ranked 48th in the number of employees per student, at 0.102 (the U.S. average was 0.137), while paying the 7th most per employee, $49,000 (the U.S. average was $39,000).[264][265][266]

Higher education

California public postsecondary education is organized into three separate systems:

- The state's public research university system is the University of California (UC). As of fall 2011, the University of California had a combined student body of 234,464 students.[268] There are ten UC campuses; nine are general campuses offering both undergraduate and graduate programs which culminate in the award of bachelor's degrees, master's degrees, and doctorates; there is one specialized campus, UC San Francisco, which is entirely dedicated to graduate education in health care, and is home to the UCSF Medical Center, the highest-ranked hospital in California.[269] The system was originally intended to accept the top one-eighth of California high school students, but several of the campuses have become even more selective.[270][271][272] The UC system historically held exclusive authority to award the doctorate, but this has since changed and CSU now has limited statutory authorization to award a handful of types of doctoral degrees independently of UC.