Azapirone: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

added and MEDMOS |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

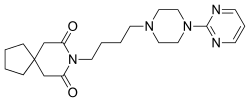

[[File:Buspirone.svg|thumb|right|250px|[[Buspirone]], the prototypical azapirone anxiolytic, which contains [[azaspirodecanedione]] and [[pyrimidinylpiperazine]] bound via a [[butyl]] chain.]] |

[[File:Buspirone.svg|thumb|right|250px|[[Buspirone]], the prototypical azapirone anxiolytic, which contains [[azaspirodecanedione]] and [[pyrimidinylpiperazine]] bound via a [[butyl]] chain.]] |

||

'''Azapirones''' are a class of [[drug]]s used as [[anxiolytic]]s and [[antipsychotic]]s.<ref name="pmid1973936">{{cite journal | author = Eison AS | title = Azapirones: history of development | journal = Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology | volume = 10 | issue = 3 Suppl | pages = 2S–5S |date=June 1990 | pmid = 1973936 | doi = 10.1097/00004714-199006001-00002| url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid8638511">{{cite journal | author = Cadieux RJ | title = Azapirones: an alternative to benzodiazepines for anxiety | journal = American Family Physician | volume = 53 | issue = 7 | pages = 2349–53 |date=May 1996 | pmid = 8638511 | doi = | url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid16856115">{{cite journal | author = Chessick CA, Allen MH, Thase M, ''et al.'' | title = Azapirones for generalized anxiety disorder | journal = Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) | volume = 3 | issue = | pages = CD006115 | year = 2006 | pmid = 16856115 | editor1-last = Chessick | editor1-first = Cheryl A | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD006115}}</ref><ref name="pmid2567039">{{cite journal | author = Feighner JP, Boyer WF | title = Serotonin-1A anxiolytics: an overview | journal = Psychopathology | volume = 22 Suppl 1 | issue = | pages = 21–6 | year = 1989 | pmid = 2567039 | doi = 10.1159/000284623| url = }}</ref> They are commonly employed to [[Augmentation (psychiatry)| |

'''Azapirones''' are a class of [[drug]]s used as [[anxiolytic]]s and [[antipsychotic]]s.<ref name="pmid1973936">{{cite journal | author = Eison AS | title = Azapirones: history of development | journal = Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology | volume = 10 | issue = 3 Suppl | pages = 2S–5S |date=June 1990 | pmid = 1973936 | doi = 10.1097/00004714-199006001-00002| url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid8638511">{{cite journal | author = Cadieux RJ | title = Azapirones: an alternative to benzodiazepines for anxiety | journal = American Family Physician | volume = 53 | issue = 7 | pages = 2349–53 |date=May 1996 | pmid = 8638511 | doi = | url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid16856115">{{cite journal | author = Chessick CA, Allen MH, Thase M, ''et al.'' | title = Azapirones for generalized anxiety disorder | journal = Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) | volume = 3 | issue = | pages = CD006115 | year = 2006 | pmid = 16856115 | editor1-last = Chessick | editor1-first = Cheryl A | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD006115}}</ref><ref name="pmid2567039">{{cite journal | author = Feighner JP, Boyer WF | title = Serotonin-1A anxiolytics: an overview | journal = Psychopathology | volume = 22 Suppl 1 | issue = | pages = 21–6 | year = 1989 | pmid = 2567039 | doi = 10.1159/000284623| url = }}</ref> They are commonly employed to [[Augmentation (psychiatry)|add on]] [[antidepressant]]s, such as [[selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor]]s (SSRIs).<ref name="pmid8827420">{{cite journal | author = Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Wilson C | title = Buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in social phobia | journal = Journal of Affective Disorders | volume = 39 | issue = 2 | pages = 115–21 |date=July 1996 | pmid = 8827420 | doi = 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00030-4| url = http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0165-0327(96)00030-4}}</ref><ref name="pmid9180827">{{cite journal | author = Bouwer C, Stein DJ | title = Buspirone is an effective augmenting agent of serotonin selective re-uptake inhibitors in severe treatment-refractory depression | journal = South African Medical Journal | volume = 87 | issue = 4 Suppl | pages = 534–7, 540 |date=April 1997 | pmid = 9180827 | doi = | url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid9864079">{{cite journal | author = Dimitriou EC, Dimitriou CE | title = Buspirone augmentation of antidepressant therapy | journal = Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology | volume = 18 | issue = 6 | pages = 465–9 |date=December 1998 | pmid = 9864079 | doi = 10.1097/00004714-199812000-00009| url = http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0271-0749&volume=18&issue=6&spage=465}}</ref><ref name="pmid11465522">{{cite journal | author = Appelberg BG, Syvälahti EK, Koskinen TE, Mehtonen OP, Muhonen TT, Naukkarinen HH | title = Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study | journal = The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry | volume = 62 | issue = 6 | pages = 448–52 |date=June 2001 | pmid = 11465522 | doi = 10.4088/JCP.v62n0608| url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid12667165">{{cite journal | author = Yamada K, Yagi G, Kanba S | title = Clinical efficacy of tandospirone augmentation in patients with major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial | journal = Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences | volume = 57 | issue = 2 | pages = 183–7 |date=April 2003 | pmid = 12667165 | doi = 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01099.x| url = http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1323-1316&date=2003&volume=57&issue=2&spage=183}}</ref> |

||

==Medical uses== |

|||

For [[panic disorder]] the benefit is not clear as evidence is insufficient.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Imai|first1=H|last2=Tajika|first2=A|last3=Chen|first3=P|last4=Pompoli|first4=A|last5=Guaiana|first5=G|last6=Castellazzi|first6=M|last7=Bighelli|first7=I|last8=Girlanda|first8=F|last9=Barbui|first9=C|last10=Koesters|first10=M|last11=Cipriani|first11=A|last12=Furukawa|first12=TA|title=Azapirones versus placebo for panic disorder in adults.|journal=The Cochrane database of systematic reviews|date=2014 Sep 30|volume=9|pages=CD010828|pmid=25268297}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Side effects of azapirones may include [[dizziness]], [[headache]]s, [[Psychomotor agitation|restlessness]], [[nausea]], and [[diarrhea]].<ref name="pmid2567039"/><ref name="pmid2870641">{{cite journal | author = Newton RE, Marunycz JD, Alderdice MT, Napoliello MJ | title = Review of the side-effect profile of buspirone | journal = The American Journal of Medicine | volume = 80 | issue = 3B | pages = 17–21 |date=March 1986 | pmid = 2870641 | doi = 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90327-X| url = }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Azapirones have more tolerable adverse effects than many other available anxiolytics like the [[benzodiazepine]]s. Unlike benzodiazepines, azapirones lack [[abuse potential]] and are not [[Substance use disorder|addictive]], do not cause [[cognitive deficit|cognitive/memory impairment]] or [[sedation]], and do not appear to induce appreciable [[Drug tolerance|tolerance]] or [[physical dependence]]. However, azapirones are considered less effective in controlling symptoms in comparison and also require several weeks for their therapeutic benefits to come to prominence.{{Citation needed|date=September 2012}} |

||

== List of azapirones == |

== List of azapirones == |

||

| Line 56: | Line 64: | ||

[[Metabolism]] of azapirones occurs in the [[liver]] and they are [[excretion|excreted]] in [[urine]] and [[feces]]. A common [[metabolite]] of several azapirones including [[buspirone]], [[gepirone]], [[ipsapirone]], [[revospirone]], and [[tandospirone]] is [[1-(2-pyrimidinyl)piperazine]] (1-PP).<ref name="pmid8750726">{{cite journal | author = Manahan-Vaughan D, Anwyl R, Rowan MJ | title = The azapirone metabolite 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)piperazine depresses excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus of the alert rat via 5-HT1A receptors | journal = European Journal of Pharmacology | volume = 294 | issue = 2–3 | pages = 617–24 |date=December 1995 | pmid = 8750726 | doi = 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00605-2| url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid1681447">{{cite journal | author = Blier P, Curet O, Chaput Y, de Montigny C | title = Tandospirone and its metabolite, 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)-piperazine--II. Effects of acute administration of 1-PP and long-term administration of tandospirone on noradrenergic neurotransmission | journal = Neuropharmacology | volume = 30 | issue = 7 | pages = 691–701 |date=July 1991 | pmid = 1681447 | doi = 10.1016/0028-3908(91)90176-C| url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid2149168">{{cite journal | author = Löscher W, Witte U, Fredow G, Traber J, Glaser T | title = The behavioural responses to 8-OH-DPAT, ipsapirone and the novel 5-HT1A receptor agonist Bay Vq 7813 in the pig | journal = Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology | volume = 342 | issue = 3 | pages = 271–7 |date=September 1990 | pmid = 2149168 | doi = 10.1007/bf00169437| url = }}</ref> 1-PP possesses 5-HT<sub>1A</sub> partial agonist and α<sub>2</sub>-adrenergic antagonist actions and likely contributes overall mostly to side effects.<ref name="pmid8750726"/><ref name="pmid1681447"/><ref name="pmid12438536">{{cite journal | author = Zuideveld KP, Rusiç-Pavletiç J, Maas HJ, Peletier LA, Van der Graaf PH, Danhof M | title = Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of buspirone and its metabolite 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)-piperazine in rats | journal = The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics | volume = 303 | issue = 3 | pages = 1130–7 |date=December 2002 | pmid = 12438536 | doi = 10.1124/jpet.102.036798 | url = http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12438536}}</ref> |

[[Metabolism]] of azapirones occurs in the [[liver]] and they are [[excretion|excreted]] in [[urine]] and [[feces]]. A common [[metabolite]] of several azapirones including [[buspirone]], [[gepirone]], [[ipsapirone]], [[revospirone]], and [[tandospirone]] is [[1-(2-pyrimidinyl)piperazine]] (1-PP).<ref name="pmid8750726">{{cite journal | author = Manahan-Vaughan D, Anwyl R, Rowan MJ | title = The azapirone metabolite 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)piperazine depresses excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus of the alert rat via 5-HT1A receptors | journal = European Journal of Pharmacology | volume = 294 | issue = 2–3 | pages = 617–24 |date=December 1995 | pmid = 8750726 | doi = 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00605-2| url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid1681447">{{cite journal | author = Blier P, Curet O, Chaput Y, de Montigny C | title = Tandospirone and its metabolite, 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)-piperazine--II. Effects of acute administration of 1-PP and long-term administration of tandospirone on noradrenergic neurotransmission | journal = Neuropharmacology | volume = 30 | issue = 7 | pages = 691–701 |date=July 1991 | pmid = 1681447 | doi = 10.1016/0028-3908(91)90176-C| url = }}</ref><ref name="pmid2149168">{{cite journal | author = Löscher W, Witte U, Fredow G, Traber J, Glaser T | title = The behavioural responses to 8-OH-DPAT, ipsapirone and the novel 5-HT1A receptor agonist Bay Vq 7813 in the pig | journal = Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology | volume = 342 | issue = 3 | pages = 271–7 |date=September 1990 | pmid = 2149168 | doi = 10.1007/bf00169437| url = }}</ref> 1-PP possesses 5-HT<sub>1A</sub> partial agonist and α<sub>2</sub>-adrenergic antagonist actions and likely contributes overall mostly to side effects.<ref name="pmid8750726"/><ref name="pmid1681447"/><ref name="pmid12438536">{{cite journal | author = Zuideveld KP, Rusiç-Pavletiç J, Maas HJ, Peletier LA, Van der Graaf PH, Danhof M | title = Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of buspirone and its metabolite 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)-piperazine in rats | journal = The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics | volume = 303 | issue = 3 | pages = 1130–7 |date=December 2002 | pmid = 12438536 | doi = 10.1124/jpet.102.036798 | url = http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12438536}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Side effects of azapirones may include [[dizziness]], [[headache]]s, [[Psychomotor agitation|restlessness]], [[nausea]], and [[diarrhea]].<ref name="pmid2567039"/><ref name="pmid2870641">{{cite journal | author = Newton RE, Marunycz JD, Alderdice MT, Napoliello MJ | title = Review of the side-effect profile of buspirone | journal = The American Journal of Medicine | volume = 80 | issue = 3B | pages = 17–21 |date=March 1986 | pmid = 2870641 | doi = 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90327-X| url = }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Azapirones have more tolerable adverse effects than many other available anxiolytics like the [[benzodiazepine]]s. Unlike benzodiazepines, azapirones lack [[abuse potential]] and are not [[Substance use disorder|addictive]], do not cause [[cognitive deficit|cognitive/memory impairment]] or [[sedation]], and do not appear to induce appreciable [[Drug tolerance|tolerance]] or [[physical dependence]]. However, azapirones are considered less effective in controlling symptoms in comparison and also require several weeks for their therapeutic benefits to come to prominence.{{Citation needed|date=September 2012}} |

||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 23:40, 4 October 2014

Azapirones are a class of drugs used as anxiolytics and antipsychotics.[1][2][3][4] They are commonly employed to add on antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).[5][6][7][8][9]

Medical uses

For panic disorder the benefit is not clear as evidence is insufficient.[10]

Side effects

Side effects of azapirones may include dizziness, headaches, restlessness, nausea, and diarrhea.[4][11]

Azapirones have more tolerable adverse effects than many other available anxiolytics like the benzodiazepines. Unlike benzodiazepines, azapirones lack abuse potential and are not addictive, do not cause cognitive/memory impairment or sedation, and do not appear to induce appreciable tolerance or physical dependence. However, azapirones are considered less effective in controlling symptoms in comparison and also require several weeks for their therapeutic benefits to come to prominence.[citation needed]

List of azapirones

The azapirones include the following agents:[12]

- Anxiolytics

- Alnespirone (S-20,499)

- Binospirone (MDL-73,005)

- Buspirone (Buspar)

- Enilospirone (CERM-3,726)

- Eptapirone (F-11,440)

- Gepirone (Ariza, Variza)

- Ipsapirone (TVX-Q-7,821)

- Revospirone (BAY-VQ-7,813)

- Tandospirone (Sediel)

- Zalospirone (WY-47,846)

- Antipsychotics

- Perospirone (Lullan)

- Tiospirone (BMY-13,859)

- Umespirone (KC-9,172)

Tandospirone has also been used to augment antipsychotics in Japan as it improves cognitive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia.[13] Buspirone is being investigated for this purpose as well.[14][15]

Chemistry

Buspirone was originally classified as an azaspirodecanedione, shortened to azapirone or azaspirone due to the fact that its chemical structure contained this moiety, and other drugs with similar structures were labeled as such as well. However, despite all being called azapirones, not all of them actually contain the azapirodecanedione component, and most in fact do not or contain a variation of it. Additionally, many azapirones are also pyrimidinylpiperazines, though again this does not apply to them all.

Drugs classed as azapirones can be identified by their -spirone or -pirone suffix.[16]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

On a pharmacological level, azapirones varyingly possess activity at the following receptors:[17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]

- 5-HT1A receptor (as partial or full agonists)

- 5-HT2A receptor (as inverse agonists)

- D2 receptor (as antagonists or partial agonists)

- α1-adrenergic receptor (as antagonists)

- α2-adrenergic receptor (as antagonists)

Actions at D4, 5-HT2C, 5-HT7, and sigma receptors have also been shown for some azapirones.[25][26][27][28]

While some of the listed properties such as 5-HT2A and D2 blockade may be useful in certain indications such as in the treatment of schizophrenia (as with perospirone and tiospirone), all of them except 5-HT1A agonism are generally undesirable in anxiolytics and only contribute to side effects. As a result, further development has commenced to bring more selective of anxiolytic agents to the market. An example of this initiative is gepirone, which is currently in clinical trials in the United States for the treatment of major depression and generalized anxiety disorder. Another example is tandospirone which has been licensed in Japan for the treatment of anxiety and as an augmentation to antidepressants for depression.

5-HT1A receptor partial agonists have demonstrated efficacy against depression in rodent studies and human clinical trials.[29][30][31][32] Unfortunately, however, their efficacy is limited and they are only relatively mild antidepressants. Instead of being used as monotherapy treatments, they are more commonly employed as augmentations to serotonergic antidepressants like the SSRIs.[5][6][7][8][9] It has been proposed that high intrinsic activity at 5-HT1A postsynaptic receptors is necessary for maximal therapeutic benefits to come to prominence, and as a result, investigation has commenced in azapirones which act as 5-HT1A receptor full agonists such as alnespirone and eptapirone.[33][34][35][36] Indeed, in preclinical studies, eptapirone produces robust antidepressant effects which surpass those of even high doses of imipramine and paroxetine.[33][34][35][36]

Pharmacokinetics

Azapirones are poorly but nonetheless appreciably absorbed and have a rapid onset of action, but have only very short half-lives ranging from 1–3 hours. As a result, they must be administered 2-3 times a day. The only exception to this rule is umespirone, which has a very long duration with a single dose lasting as long as 23 hours.[37] Unfortunately, umespirone has not been commercialized. Although never commercially produced, Bristol-Myers Squibb applied for a patent on Oct 28, 1993 and received the patent on Jul 11, 1995 for an extended release formulation of buspirone.[38] An extended release formulation of gepirone is currently under development and if approved, should help to improve this issue.

Metabolism of azapirones occurs in the liver and they are excreted in urine and feces. A common metabolite of several azapirones including buspirone, gepirone, ipsapirone, revospirone, and tandospirone is 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)piperazine (1-PP).[39][40][41] 1-PP possesses 5-HT1A partial agonist and α2-adrenergic antagonist actions and likely contributes overall mostly to side effects.[39][40][42]

References

- ^ Eison AS (June 1990). "Azapirones: history of development". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 10 (3 Suppl): 2S–5S. doi:10.1097/00004714-199006001-00002. PMID 1973936.

- ^ Cadieux RJ (May 1996). "Azapirones: an alternative to benzodiazepines for anxiety". American Family Physician. 53 (7): 2349–53. PMID 8638511.

- ^ Chessick CA, Allen MH, Thase M; et al. (2006). Chessick, Cheryl A (ed.). "Azapirones for generalized anxiety disorder". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online). 3: CD006115. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006115. PMID 16856115.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Feighner JP, Boyer WF (1989). "Serotonin-1A anxiolytics: an overview". Psychopathology. 22 Suppl 1: 21–6. doi:10.1159/000284623. PMID 2567039.

- ^ a b Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Wilson C (July 1996). "Buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in social phobia". Journal of Affective Disorders. 39 (2): 115–21. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(96)00030-4. PMID 8827420.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bouwer C, Stein DJ (April 1997). "Buspirone is an effective augmenting agent of serotonin selective re-uptake inhibitors in severe treatment-refractory depression". South African Medical Journal. 87 (4 Suppl): 534–7, 540. PMID 9180827.

- ^ a b Dimitriou EC, Dimitriou CE (December 1998). "Buspirone augmentation of antidepressant therapy". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 18 (6): 465–9. doi:10.1097/00004714-199812000-00009. PMID 9864079.

- ^ a b Appelberg BG, Syvälahti EK, Koskinen TE, Mehtonen OP, Muhonen TT, Naukkarinen HH (June 2001). "Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 62 (6): 448–52. doi:10.4088/JCP.v62n0608. PMID 11465522.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Yamada K, Yagi G, Kanba S (April 2003). "Clinical efficacy of tandospirone augmentation in patients with major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 57 (2): 183–7. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01099.x. PMID 12667165.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Imai, H; Tajika, A; Chen, P; Pompoli, A; Guaiana, G; Castellazzi, M; Bighelli, I; Girlanda, F; Barbui, C; Koesters, M; Cipriani, A; Furukawa, TA (2014 Sep 30). "Azapirones versus placebo for panic disorder in adults". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 9: CD010828. PMID 25268297.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Newton RE, Marunycz JD, Alderdice MT, Napoliello MJ (March 1986). "Review of the side-effect profile of buspirone". The American Journal of Medicine. 80 (3B): 17–21. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(86)90327-X. PMID 2870641.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Use of Common Stems in the Selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for Pharmaceutical Substances: Alphabetical list of stems together with corresponding INNs".

- ^ Sumiyoshi T, Matsui M, Nohara S; et al. (October 2001). "Enhancement of cognitive performance in schizophrenia by addition of tandospirone to neuroleptic treatment". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 158 (10): 1722–5. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1722. PMID 11579010.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sumiyoshi T, Park S, Jayathilake K, Roy A, Ertugrul A, Meltzer HY (September 2007). "Effect of buspirone, a serotonin1A partial agonist, on cognitive function in schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Schizophrenia Research. 95 (1–3): 158–68. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2007.06.008. PMID 17628435.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Piskulić D, Olver JS, Maruff P, Norman TR (August 2009). "Treatment of cognitive dysfunction in chronic schizophrenia by augmentation of atypical antipsychotics with buspirone, a partial 5-HT(1A) receptor agonist". Human Psychopharmacology. 24 (6): 437–46. doi:10.1002/hup.1046. PMID 19637398.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances" (PDF). 2004. Retrieved April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Hamik; Oksenberg, D; Fischette, C; Peroutka, SJ (1990). "Analysis of tandospirone (SM-3997) interactions with neurotransmitter receptor binding sites". Biological Psychiatry. 28 (2): 99–109. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(90)90627-E. PMID 1974152.

- ^ Barnes NM, Costall B, Domeney AM; et al. (September 1991). "The effects of umespirone as a potential anxiolytic and antipsychotic agent". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 40 (1): 89–96. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(91)90326-W. PMID 1685786.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ahlenius S, Wijkström A (November 1992). "Mixed agonist-antagonist properties of umespirone at neostriatal dopamine receptors in relation to its behavioral effects in the rat". European Journal of Pharmacology. 222 (1): 69–74. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(92)90464-F. PMID 1361441.

- ^ Sumiyoshi T, Suzuki K, Sakamoto H; et al. (February 1995). "Atypicality of several antipsychotics on the basis of in vivo dopamine-D2 and serotonin-5HT2 receptor occupancy". Neuropsychopharmacology. 12 (1): 57–64. doi:10.1016/0893-133X(94)00064-7. PMID 7766287.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weiner DM, Burstein ES, Nash N; et al. (October 2001). "5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptor inverse agonists as antipsychotics". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 299 (1): 268–76. PMID 11561089.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hirose A, Kato T, Ohno Y; et al. (July 1990). "Pharmacological actions of SM-9018, a new neuroleptic drug with both potent 5-hydroxytryptamine2 and dopamine2 antagonistic actions". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 53 (3): 321–9. doi:10.1254/jjp.53.321. PMID 1975278.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kato T, Hirose A, Ohno Y, Shimizu H, Tanaka H, Nakamura M (December 1990). "Binding profile of SM-9018, a novel antipsychotic candidate". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 54 (4): 478–81. doi:10.1254/jjp.54.478. PMID 1982326.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Odagaki Y, Toyoshima R (2007). "5-HT1A receptor agonist properties of antipsychotics determined by [35S]GTPgammaS binding in rat hippocampal membranes". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 34 (5–6): 462–6. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04595.x. PMID 17439416.

- ^ Roth BL, Tandra S, Burgess LH, Sibley DR, Meltzer HY (August 1995). "D4 dopamine receptor binding affinity does not distinguish between typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs". Psychopharmacology. 120 (3): 365–8. doi:10.1007/BF02311185. PMID 8524985.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Herrick-Davis K, Grinde E, Teitler M (October 2000). "Inverse agonist activity of atypical antipsychotic drugs at human 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptors". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 295 (1): 226–32. PMID 10991983.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rauly-Lestienne I, Boutet-Robinet E, Ailhaud MC, Newman-Tancredi A, Cussac D (October 2007). "Differential profile of typical, atypical and third generation antipsychotics at human 5-HT7a receptors coupled to adenylyl cyclase: detection of agonist and inverse agonist properties". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 376 (1–2): 93–105. doi:10.1007/s00210-007-0182-6. PMID 17786406.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Itzhak Y, Ruhland M, Krähling H (February 1990). "Binding of umespirone to the sigma receptor: evidence for multiple affinity states". Neuropharmacology. 29 (2): 181–4. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(90)90058-Y. PMID 1970425.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kennett GA, Dourish CT, Curzon G (February 1987). "Antidepressant-like action of 5-HT1A agonists and conventional antidepressants in an animal model of depression". European Journal of Pharmacology. 134 (3): 265–74. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(87)90357-8. PMID 2883013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Blier P, Ward NM (February 2003). "Is there a role for 5-HT1A agonists in the treatment of depression?". Biological Psychiatry. 53 (3): 193–203. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01643-8. PMID 12559651.

- ^ Robinson DS, Rickels K, Feighner J; et al. (June 1990). "Clinical effects of the 5-HT1A partial agonists in depression: a composite analysis of buspirone in the treatment of depression". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 10 (3 Suppl): 67S–76S. doi:10.1097/00004714-199006001-00013. PMID 2198303.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bielski RJ, Cunningham L, Horrigan JP, Londborg PD, Smith WT, Weiss K (April 2008). "Gepirone extended-release in the treatment of adult outpatients with major depressive disorder: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 69 (4): 571–7. doi:10.4088/jcp.v69n0408. PMID 18373383.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Koek W, Patoiseau JF, Assié MB; et al. (October 1998). "F 11440, a potent, selective, high efficacy 5-HT1A receptor agonist with marked anxiolytic and antidepressant potential". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 287 (1): 266–83. PMID 9765347.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Koek W, Vacher B, Cosi C; et al. (May 2001). "5-HT1A receptor activation and antidepressant-like effects: F 13714 has high efficacy and marked antidepressant potential". European Journal of Pharmacology. 420 (2–3): 103–12. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01011-1. PMID 11408031.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Prinssen EP, Colpaert FC, Koek W (October 2002). "5-HT1A receptor activation and anti-cataleptic effects: high-efficacy agonists maximally inhibit haloperidol-induced catalepsy". European Journal of Pharmacology. 453 (2–3): 217–21. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(02)02430-5. PMID 12398907.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Maurel JL, Autin JM, Funes P, Newman-Tancredi A, Colpaert F, Vacher B (October 2007). "High-efficacy 5-HT1A agonists for antidepressant treatment: a renewed opportunity". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 50 (20): 5024–33. doi:10.1021/jm070714l. PMID 17803293.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Holland RL, Wesnes K, Dietrich B (1994). "Single dose human pharmacology of umespirone". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 46 (5): 461–8. doi:10.1007/bf00191912. PMID 7957544.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ US patent 5431922, Nicklasson AGM, "Method for administration of buspirone", issued 1995-07-11, assigned to Bristol-Myers Squibb Company url=http://www.google.com/patents/US5431922

- ^ a b Manahan-Vaughan D, Anwyl R, Rowan MJ (December 1995). "The azapirone metabolite 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)piperazine depresses excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus of the alert rat via 5-HT1A receptors". European Journal of Pharmacology. 294 (2–3): 617–24. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(95)00605-2. PMID 8750726.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Blier P, Curet O, Chaput Y, de Montigny C (July 1991). "Tandospirone and its metabolite, 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)-piperazine--II. Effects of acute administration of 1-PP and long-term administration of tandospirone on noradrenergic neurotransmission". Neuropharmacology. 30 (7): 691–701. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(91)90176-C. PMID 1681447.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Löscher W, Witte U, Fredow G, Traber J, Glaser T (September 1990). "The behavioural responses to 8-OH-DPAT, ipsapirone and the novel 5-HT1A receptor agonist Bay Vq 7813 in the pig". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 342 (3): 271–7. doi:10.1007/bf00169437. PMID 2149168.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zuideveld KP, Rusiç-Pavletiç J, Maas HJ, Peletier LA, Van der Graaf PH, Danhof M (December 2002). "Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of buspirone and its metabolite 1-(2-pyrimidinyl)-piperazine in rats". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 303 (3): 1130–7. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.036798. PMID 12438536.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)