Methadone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Dolophine, Methadose, Methatab,[3] others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682134 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Addiction liability | High[4] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous, insufflation, sublingual, rectal |

| Drug class | Opioid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 15–20% subcutaneous[6] 100% intravenous[6] |

| Protein binding | 85–90%[6] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A4, CYP2B6 and CYP2D6-mediated)[6][8] |

| Onset of action | Rapid[7] |

| Elimination half-life | 15 to 55 hours[8] |

| Duration of action | Single dose: 4–8 h Prolonged use: • Withdrawal prevention: 1–2 days[7] • Pain relief: 8–12 hours[7][9] |

| Excretion | Urine, faeces[8] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.907 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H27NO |

| Molar mass | 309.453 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| | |

Methadone, sold under the brand names Dolophine and Methadose among others, is a synthetic opioid used medically to treat chronic pain and opioid use disorder.[7] Prescribed for daily use, the medicine relieves cravings and opioid withdrawal symptoms.[10] Withdrawal management using methadone can be accomplished in less than a month,[11] or it may be done gradually over a longer period of time, or simply maintained for the rest of the patient's life.[7] While a single dose has a rapid effect, maximum effect can take up to five days of use.[7][12] After long-term use, in people with normal liver function, effects last 8 to 36 hours.[7][9] Methadone is usually taken by mouth and rarely by injection into a muscle or vein.[7]

Side effects are similar to those of other opioids.[7] These frequently include dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, vomiting, and sweating.[7][13] Serious risks include opioid abuse and respiratory depression.[7] Abnormal heart rhythms may also occur due to a prolonged QT interval.[7] The number of deaths in the United States involving methadone poisoning declined from 4,418 in 2011[14] to 3,300 in 2015.[15] Risks are greater with higher doses.[16] Methadone is made by chemical synthesis and acts on opioid receptors.[7]

Methadone was developed in Germany in the late 1930s by Gustav Ehrhart and Max Bockmühl.[17][18] It was approved for use as an analgesic in the United States in 1947, and has been used in the treatment of addiction since the 1960s.[7][19] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[20]

Medical uses

[edit]Opioid addiction

[edit]Methadone is used for the treatment of opioid use disorder.[21] It may be used as maintenance therapy or in shorter periods to manage opioid withdrawal symptoms. Its use for the treatment of addiction is usually strictly regulated. In the US, outpatient treatment programs must be certified by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and registered by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in order to prescribe methadone for opioid addiction.

A 2009 Cochrane review found methadone was effective in retaining people in treatment and in the reduction or cessation of heroin use as measured by self-report and urine/hair analysis, and did not affect criminal activity or risk of death.[22]

Treatment of opioid-dependent persons with methadone follows one of two routes: maintenance or withdrawal management.[23] Methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) usually takes place in outpatient settings. It is usually prescribed as a single daily dose medication for those who wish to abstain from illicit opioid use. Treatment models for MMT differ. It is not uncommon for treatment recipients to be administered methadone in a specialized clinic, where they are observed for around 15–20 minutes post-dosing, to reduce the risk of diversion of medication.[24]

The duration of methadone treatment programs ranges from a few months to years. Given opioid dependence is characteristically a chronic relapsing/remitting disorder, MMT may be lifelong. The length of time a person remains in treatment depends on a number of factors. While starting doses may be adjusted based on the amount of opioids reportedly used, most clinical guidelines suggest doses start low (e.g., at doses not exceeding 40 mg daily) and are incremented gradually.[10][25] It has been found that doses of 40 mg per day were sufficient to help control the withdrawal symptoms but not enough to curb the cravings for the drug. Doses of 80 to 100 mg per day have shown higher rates of success in patients and less illicit heroin use during the maintenance therapy.[26] However, higher doses do put a patient more at risk for overdose than a moderately low dose (e.g. 20 mg/day).[12]

Methadone maintenance has been shown to reduce the transmission of bloodborne viruses associated with opioid injection, such as hepatitis B and C, and/or HIV.[10] The principal goals of methadone maintenance are to relieve opioid cravings, suppress the abstinence syndrome, and block the euphoric effects associated with opioids.

Chronic methadone dosing will eventually lead to neuroadaptation, characterised by tolerance and dependence. However, when used correctly in treatment, maintenance therapy has been found to be medically safe, non-sedating, and can provide a slow recovery from opioid addiction.[10] Methadone has been widely used for pregnant women addicted to opioids.[10]

Pain

[edit]Methadone is used as an analgesic in chronic pain, often in rotation with other opioids.[27][28] Due to its activity at the NMDA receptor, it may be more effective against neuropathic pain; for the same reason, tolerance to the analgesic effects may be less than that of other opioids.[29][30]

Adverse effects

[edit]

Adverse effects of methadone include:[33]

- Sedation

- Constipation[34][35]

- Flushing[35]

- Perspiration[35]

- Heat intolerance

- Dizziness or fainting[34][36][37]

- Weakness[35]

- Fatigue[35]

- Drowsiness[34]

- Constricted pupils

- Dry mouth[34][35]

- Nausea and vomiting[34][35]

- Low blood pressure

- Headache[35]

- Heart problems such as chest pain[34][36] or fast heartbeat[34][36][37]

- Abnormal heart rhythms[37][38]

- Respiratory problems such as trouble breathing,[34][36] slow or shallow breathing (hypoventilation),[34][36] lightheadedness,[34][36][37] or fainting[34][36]

- Weight gain[35]

- Memory loss

- Itching

- Difficulty urinating[35]

- Swelling of the hands, arms, feet, and legs[35]

- Mood changes,[35] (e.g, euphoria, disorientation)

- Blurred vision[35]

- Decreased libido,[34][35] difficulty in reaching orgasm,[34] or impotence[34][35]

- Missed menstrual periods[35]

- Skin rash

- Central sleep apnea

Withdrawal symptoms

[edit]Methadone withdrawal symptoms are reported as being significantly more protracted than withdrawal from opioids with shorter half-lives.

When used for opioid maintenance therapy, Methadone is generally administered as an oral liquid. Methadone has been implicated in contributing to significant tooth decay. Methadone causes dry mouth, reducing the protective role of saliva in preventing decay. Other putative mechanisms of methadone-related tooth decay include craving for carbohydrates related to opioids, poor dental care, and general decrease in personal hygiene. These factors, combined with sedation, have been linked to the causation of extensive dental damage.[39][40]

Physical symptoms

[edit]- Lightheadedness[41]

- Tearing of the eyes[41][42]

- Mydriasis (dilated pupils)[41]

- Photophobia (sensitivity to light)

- Hyperventilation (breathing that is too fast/deep)

- Runny nose[42]

- Yawning

- Sneezing[42]

- Nausea,[41][42] vomiting,[41][42] and diarrhea[41]

- Fever[42]

- Sweating[41]

- Chills[42]

- Tremors[41][42]

- Akathisia (restlessness)

- Tachycardia (fast heartbeat)[42]

- Aches[41] and pains, often in the joints or legs

- Elevated pain sensitivity

- Blood pressure that is too high (hypertension, may cause a stroke)

Cognitive symptoms

[edit]- Suicidal ideation

- Susceptibility to cravings[41]

- Depression[41]

- Spontaneous orgasm

- Prolonged insomnia

- Delirium

- Auditory hallucinations

- Visual hallucinations

- Increased perception of odors (olfaction), real or imagined

- Marked increase in sex drive

- Agitation

- Anxiety[41]

- Panic disorder

- Nervousness[41]

- Paranoia

- Delusions

- Apathy

- Anorexia (symptom)

Black box warning

[edit]Methadone has the following U.S. FDA black box warning:[43]

- Risk of addiction and abuse

- Potentially fatal respiratory depression

- Lethal overdose in accidental ingestion

- QT prolongation[44]

- Neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome in children of pregnant women

- CYP450 drug interactions

- Risks when used with alcohol, benzodiazepines, and other CNS depressants.

- A certified opioid treatment program is required under federal law (42 CFR 8.12) when dispensing methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction.

Overdose

[edit]Most people who overdose on methadone show some of the following symptoms:

- Miosis (constricted pupils)[45]

- Vomiting[46]

- Spasms of the stomach and intestines[47]

- Hypoventilation (breathing that is too slow/shallow)[45]

- Drowsiness,[45] sleepiness, disorientation, sedation, unresponsiveness

- Skin that is cool, clammy (damp), and pale[45]

- Blue fingernails and lips[47]

- Limp muscles,[45] trouble staying awake, nausea

- Unconsciousness[45] and coma[45]

The respiratory depression of an overdose can be treated with naloxone.[42] Naloxone is preferred to the newer, longer-acting antagonist naltrexone. Despite methadone's much longer duration of action compared to either heroin and other shorter-acting agonists and the need for repeat doses of the antagonist naloxone, it is still used for overdose therapy. As naltrexone has a longer half-life, it is more difficult to titrate. If too large a dose of the opioid antagonist is given to a dependent person, it will result in withdrawal symptoms (possibly severe). When using naloxone, the naloxone will be quickly eliminated and the withdrawal will be short-lived. Doses of naltrexone take longer to be eliminated from the person's system. A common problem in treating methadone overdoses is that, given the short action of naloxone (versus the extremely longer-acting methadone), a dosage of naloxone given to a methadone-overdosed person will initially work to bring the person out of overdose, but once the naloxone wears off, if no further naloxone is administered, the person can go right back into overdose (based upon time and dosage of the methadone ingested).

Tolerance and dependence

[edit]As with other opioid medications, tolerance and dependence usually develop with repeated doses. There is some clinical evidence that tolerance to analgesia is less with methadone compared to other opioids; this may be due to its activity at the NMDA receptor. Tolerance to the different physiological effects of methadone varies; tolerance to analgesic properties may or may not develop quickly, but tolerance to euphoria usually develops rapidly, whereas tolerance to constipation, sedation, and respiratory depression develops slowly (if ever).[48]

Driving

[edit]Methadone treatment may impair driving ability.[49] Drug abusers had significantly more involvement in serious crashes than non-abusers in a study by the University of Queensland. In the study of a group of 220 drug abusers, most of them poly-drug abusers, 17 were involved in crashes killing people, compared with a control group of other people randomly selected having no involvement in fatal crashes.[50] However, there have been multiple studies verifying the ability of methadone maintenance patients to drive.[51] In the UK, persons who are prescribed oral methadone can continue to drive after they have satisfactorily completed an independent medical examination which will include a urine screen for drugs. The license will be issued for 12 months at a time and even then, only following a favourable assessment from their own doctor.[52] Individuals who are prescribed methadone for either IV or IM administration cannot drive in the UK, mainly due to the increased sedation effects that this route of use can cause.

Mortality

[edit]In the United States, deaths linked to methadone more than quadrupled in the five-year period between 1999 and 2004. According to the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics,[53] as well as a 2006 series in the Charleston Gazette (West Virginia),[54] medical examiners listed methadone as contributing to 3,849 deaths in 2004. That number was up from 790 in 1999. Approximately 82 percent of those deaths were listed as accidental, and most deaths involved combinations of methadone with other drugs (especially benzodiazepines).

Although deaths from methadone are on the rise[needs update], methadone-associated deaths are not being caused primarily by methadone intended for methadone treatment programs, according to a panel of experts convened by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which released a report titled "Methadone-Associated Mortality, Report of a National Assessment". The consensus report concludes that "although the data remains incomplete, National Assessment meeting participants concurred that methadone tablets or Diskets distributed through channels other than opioid treatment programs most likely are the central factors in methadone-associated mortality."[55]

In 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a caution about methadone, titled "Methadone Use for Pain Control May Result in Death." The FDA also revised the drug's package insert. The change deleted previous information about the usual adult dosage. The Charleston Gazette reported, "The old language about the 'usual adult dose' was potentially deadly, according to pain specialists."[56]

Pharmacology

[edit]| Compound | Affinities (Ki, in nM) | Ratios | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOR | DOR | KOR | SERT | NET | NMDAR | M:D:K | SERT:NET | |

| Racemic methadone | 1.7 | 435 | 405 | 1,400 | 259 | 2,500–8,300 | 1:256:238 | 1:5 |

| Dextromethadone | 19.7 | 960 | 1,370 | 992 | 12,700 | 2,600–7,400 | 1:49:70 | 1:13 |

| Levomethadone | 0.945 | 371 | 1,860 | 14.1 | 702 | 2,800–3,400 | 1:393:1968 | 1:50 |

Methadone acts by binding to the μ-opioid receptor, but also has some affinity for the NMDA receptor, an ionotropic glutamate receptor. Methadone is metabolized by CYP3A4, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, and is a substrate, or in this case target, for the P-glycoprotein efflux protein, a protein which helps pump foreign substances out of cells, in the intestines and brain. The bioavailability and elimination half-life of methadone are subject to substantial interindividual variability. Its main route of administration is oral. Adverse effects include sedation, hypoventilation, constipation and miosis, in addition to tolerance, dependence and withdrawal difficulties. The withdrawal period can be much more prolonged than with other opioids, spanning anywhere from two weeks to several months.

The metabolic half-life of methadone differs from its duration of action. The metabolic half-life is 8 to 59 hours (approximately 24 hours for opioid-tolerant people, and 55 hours in opioid-naive people), as opposed to a half-life of 1 to 5 hours for morphine.[12] The length of the half-life of methadone allows for exhibition of respiratory depressant effects for an extended duration of time in opioid-naive people.[12]

Methadone at therapeutic concentrations is known to prolong the QTc interval, which indicates that the heart muscle repolarizes more slowly. This QTc prolongation tends to increase the risk of torsades de pointes (TdP), a heart rhythm disturbance that can lead to syncope or sudden death. In a large observational study in Sweden, methadone was associated with a particularly high incidence of TdP, especially in younger patients. The incidence of TdP was 41.9 cases per 100,000 users of methadone in the 18-64 year old age group.[59] In this study of TdP, methadone was the highest-risk drug in the 18-64 year-old group, with the sole exception of the antiarrhythmic drug amiodarone, which was associated with 66.5 cases of TdP per 100,000 amiodarone users.[59] The high incidence of TdP in amiodarone-treated patients may indicate correlation and not causation, because amiodarone is often prescribed to patients with preexisting heart conditions that independently increase the risk of TdP. Methadone likely causes cardiac arrhythmias (such as TdP) via two mechanisms.[60] Like many other cardiotoxic drugs, methadone blocks the hERG K+ channel. The two enantiomers of methadone inhibit hERG channels with different potency. Dextromethadone, which is less potent as an opioid, is more potent at blocking the hERG channel with an IC50 of ~12 μM. Levomethadone has a lower affinity, with an IC50 of ~29 μM at the hERG channel.[60] Methadone is also known to block the Nav1.5 voltage-gated Na+ channel (SCN5A) with an IC50 of ~10 μM, which is similar to the local anesthetic bupivacaine. Both enantiomers of methadone block the Nav1.5 channel with similar affinities.[60] Bupivacaine is especially cardiotoxic among local anesthetics, and it is believed to act via this same sodium channel. Plasma concentrations of methadone in recovering addicts can reach 4 μM during therapy, so the actions of methadone at both the hERG potassium channel and the Nav1.5 sodium channel are possibly clinically relevant in producing cardiac side effects.[60] This also suggests that levomethadone is not completely free of cardiac toxicity.

Mechanism of action

[edit]Levomethadone (the R-(–)-methadone enantiomer) is a μ-opioid receptor agonist with higher intrinsic activity than morphine, but lower affinity.[61] Dextromethadone (the S-(+)-methadone enantiomer) has a much lower affinity to the μ-opioid receptor than levomethadone. Both enantiomers bind to the glutamatergic NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor, acting as noncompetitive antagonists. Methadone has been shown to reduce neuropathic pain in rat models, primarily through NMDA receptor antagonism.[citation needed] NMDA antagonists such as dextromethorphan, ketamine, tiletamine and ibogaine are being studied for their role in decreasing the development of tolerance to opioids and as possible for eliminating addiction/tolerance/withdrawal,[citation needed] possibly by disrupting memory circuitry. Acting as an NMDA antagonist may be one mechanism by which methadone decreases craving for opioids and tolerance, and has been proposed as a possible mechanism for its distinguished efficacy regarding the treatment of neuropathic pain.[citation needed] Methadone also acted as a potent, noncompetitive α3β4 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist in rat receptors, expressed in human embryonic kidney cell lines.[62]

Metabolism

[edit]Methadone has a slow metabolism and very high fat solubility, making it longer lasting than morphine-based drugs. Methadone has a typical elimination half-life of 15 to 60 hours with a mean of around 22. However, metabolism rates vary greatly between individuals, up to a factor of 100,[63][64] ranging from as few as 4 hours to as many as 130 hours,[65] or even 190 hours.[66] This variability is apparently due to genetic variability in the production of the associated cytochrome enzymes CYP3A4, CYP2B6 and CYP2D6. Many substances can also induce, inhibit or compete with these enzymes further affecting (sometimes dangerously) methadone half-life. A longer half-life frequently allows for administration only once a day in opioid withdrawal management and maintenance programs. People who metabolize methadone rapidly, on the other hand, may require twice daily dosing to obtain sufficient symptom alleviation while avoiding excessive peaks and troughs in their blood concentrations and associated effects.[65] This can also allow lower total doses in some such people. The analgesic activity is shorter than the pharmacological half-life; dosing for pain control usually requires multiple doses per day normally dividing daily dosage for administration at 8 hour intervals.[67]

The main metabolic pathway involves N-demethylation by CYP3A4 in the liver and intestine to give 2-ethylidene-1,5-dimethyl-3,3-diphenylpyrrolidine (EDDP).[6][68] This inactive product, as well as the inactive 2-ethyl-5-methyl-3,3-diphenyl-1-pyrroline (EMDP), produced by a second N-demethylation, are detectable in the urine of those taking methadone.

- Methadone and its two main metabolites

-

Methadone

-

EDDP

-

EDMP

Route of administration

[edit]The most common route of administration at a methadone clinic is in a racemic oral solution, though in Germany, only the R enantiomer (the L optical isomer) has traditionally been used, as it is responsible for most of the desired opioid effects.[65] The single-isomer form is becoming less common due to the higher production costs.

Methadone is available in traditional pill, sublingual tablet, and two different formulations designed for the person to drink. Drinkable forms include ready-to-dispense liquid (sold in the United States as Methadose), and Diskets (known on the street as "wafers" or "biscuits") tablets which are dispersible in water for oral administration, used in a similar fashion to Alka-Seltzer. The liquid form is the most common as it allows for smaller dose changes. Methadone is almost as effective when administered orally as by injection. Oral medication is usually preferable because it offers safety, simplicity and represents a step away from injection-based drug abuse in those recovering from addiction. U.S. federal regulations require the oral form in addiction treatment programs.[69] Injecting methadone pills can cause collapsed veins, bruising, swelling, and possibly other harmful effects. Methadone pills often contain talc that, when injected, produces a swarm of tiny solid particles in the blood, causing numerous minor blood clots.[70][71] These particles cannot be filtered out before injection, and will accumulate in the body over time, especially in the lungs and eyes, producing various complications such as pulmonary hypertension, an irreversible and progressive disease.[72][73][74] The formulation sold under the brand name Methadose (flavored liquid suspension for oral dosing, commonly used for maintenance purposes) should not be injected either.[75]

Information leaflets included in packs of UK methadone tablets state that the tablets are for oral use only and that use by any other route can cause serious harm. In addition to this warning, additives have now been included in the tablet formulation to make the use of them by the IV route more difficult.[76]

Methadone is also available in ampoules with strength of 50mg/ml & 10mg/ml for IV/IM/SC use in the UK. [77] Prescribing the injectable formulation was more common in the 90s with prescribers reporting that up to 9-10% of all methadone prescription were for ampoules. This practice is much less common nowadays [78]

Chemistry

[edit]Detection in biological fluids

[edit]Methadone and its major metabolite, 2-ethylidene-1,5-dimethyl-3,3-diphenylpyrrolidine (EDDP), are often measured in urine as part of a drug abuse testing program, in plasma or serum to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized victims, or in whole blood to assist in a forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal violation or a case of sudden death. Methadone usage history is considered in interpreting the results as a chronic user can develop tolerance to doses that would incapacitate an opioid-naïve individual. Chronic users often have high methadone and EDDP baseline values.[79]

Conformation

[edit]The protonated form of methadone takes on an extended conformation, while the free base is more compact. In particular, it was found that there is an interaction between the tertiary amine and the carbonyl carbon of the ketone function (R3N ••• >C=O) that limits the molecule's conformation freedom, though the distance (291 pm by X-ray) is far too long to represent a true chemical bond. However, it does represent the initial trajectory of attack of an amine on a carbonyl group and was an important piece of experimental evidence for the proposal of the Bürgi–Dunitz angle for carbonyl addition reactions.[80]

History

[edit]

Methadone was developed in 1937 in Germany by scientists working for I.G. Farbenindustrie AG at the Farbwerke Hoechst who were looking for a synthetic opioid that could be created with readily available precursors, to solve Germany's opium and morphine shortage problem.[81][82] On 11 September 1941 Bockmühl and Ehrhart filed an application for a patent for a synthetic substance they called Hoechst 10820 or Polamidon (a name still in regular use in Germany)[83] and whose structure had little relation to morphine or other "true opiates" such as diamorphine (Heroin), desomorphine (Permonid), nicomorphine (Vilan), codeine, dihydrocodeine, oxymorphone (Opana), hydromorphone (Dilaudid), oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Dicodid), and other closely related opium alkaloid derivatives and analogues.[84] It was brought to market in 1943 and was widely used by the German army during WWII as a substitute for morphine.[81]

In the 1930s, pethidine (meperidine) went into production in Germany; however, production of methadone, then being developed under the designation Hoechst 10820, was not carried forward because of side effects discovered in the early research.[85] After the war, all German patents, trade names and research records were requisitioned and expropriated by the Allies. The records on the research work of the I.G. Farbenkonzern at the Farbwerke Hoechst were confiscated by the U.S. Department of Commerce Intelligence, investigated by a Technical Industrial Committee of the U.S. Department of State and then brought to the US.[81] The report published by the committee noted that while methadone itself was potentially addictive, it produced "considerably" less euphoria, sedation, and respiratory depression than morphine at equianalgesic doses and was thus interesting as a commercial drug. The same report also compared methadone to pethidine. German researchers reported that methadone was capable of producing strong morphine-like physical dependence, which is characterized by opioid withdrawal symptoms which are lesser in severity and intensity compared to morphine, but methadone was associated with a considerably prolonged or protracted withdrawal syndrome when compared to morphine.[48][81] Morphine produced higher rates of self-administration and reinforcing behaviour in both human and animal subjects when compared to both methadone and pethidine. In comparison to equianalgesic doses of pethidine (Demerol), methadone was shown to produce less euphoria, but higher rates of constipation, and roughly equal levels of respiratory depression and sedation.[81]

In the early 1950s, methadone (most times the racemic HCl salts mixture) was also investigated for use as an antitussive.[86]

Isomethadone, noracymethadol, LAAM, and normethadone were first developed in Germany, United Kingdom, Belgium, Austria, Canada, and the United States in the thirty or so years after the 1937 discovery of pethidine, the first synthetic opioid used in medicine. These synthetic opioids have increased length and depth of satiating any opiate cravings and generate very strong analgesic effects due to their long metabolic half-life and strong receptor affinity at the mu-opioid receptor sites. Therefore, they impart much of the satiating and anti-addictive effects of methadone by means of suppressing drug cravings.[87]

It was only in 1947 that the drug was given the generic name "methadone" by the Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry of the American Medical Association. Since the patent rights of the I.G. Farbenkonzern and Farbwerke Hoechst were no longer protected, each pharmaceutical company interested in the formula could buy the rights for the commercial production of methadone for just one dollar (MOLL 1990).

Methadone was introduced into the United States in 1947 by Eli Lilly and Company as an analgesic under the trade name Dolophine.[81] An urban myth later arose that Nazi leader Adolf Hitler ordered the manufacture of methadone or that the brand name 'Dolophine' was named after him, probably based on the similarity of "doloph" with "Adolph". (The pejorative term "adolphine" would appear in the early 1970s.[88][89]) However, the name "Dolophine" was a contraction of "Dolo" from the Latin word dolor (pain), and finis, the Latin word for "end". Therefore, Dolophine literally means "pain end".[90]

Methadone was studied as a treatment for opioid addiction at the Addiction Research Center of the Narcotics Farm in Lexington, Kentucky in the 1950s, and by Rockefeller University physicians Robert Dole and Marie Nyswander in the 1960s in New York City.[91] By 1976, methadone clinics had opened in cities including Chicago, New York, and New Haven, with some 38,000 patients treated in New York City alone.[91][92]

Society and culture

[edit]Brand names

[edit]Brand names include Dolophine, Symoron, Amidone, Methadose, Physeptone, Metadon, Metadol, Metadol-D, Heptanon and Heptadon among others.

Economics

[edit]In the US, generic methadone tablets are inexpensive, with retail prices ranging from $0.25 to $2.50 per defined daily dose.[93]

Methadone maintenance clinics in the US may be covered by private insurances, Medicaid, or Medicare.[94] Medicare covers methadone under the prescription drug benefit, Medicare Part D, when it is prescribed for pain, but not when it is used for opioid dependence treatment because it cannot be dispensed in a retail pharmacy for this purpose.[95] In California methadone maintenance treatment is covered under the medical benefit. Patients' eligibility for methadone maintenance treatment is most often contingent on them being enrolled in substance abuse counseling. People on methadone maintenance in the US either have to pay cash or if covered by insurance must complete a pre-determined number of hours per month in therapeutic groups or counseling.[96] The United States Department of Veteran's Affairs (VA) Alcohol and Drug Dependence Rehabilitation Program offers methadone services to eligible veterans enrolled in the VA health care system.[97]

Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) cost analyses often compare the cost of clinic visits versus the overall societal costs of illicit opioid use.[98][99] A preliminary cost analysis conducted in 2016 by the US Department of Defense determined that methadone treatment, which includes psychosocial and support services, may cost an average of $126.00 per week or $6,552.00 per year.[100] The average cost for one full year of methadone maintenance treatment is approximately $4,700 per patient, whereas one full year of imprisonment costs approximately $24,000 per person.[101]

Regulation

[edit]United States and Canada

[edit]Methadone is a Schedule I controlled substance in Canada and Schedule II in the United States, with an ACSCN of 9250 and a 2014 annual aggregate manufacturing quota of 31,875 kilos for sale. Methadone intermediate is also controlled, under ACSCN 9226 also under Schedule II, with a quota of 38,875 kilos. In most countries of the world, methadone is similarly restricted. The salts of methadone in use are the hydrobromide (free base conversion ratio 0.793), hydrochloride (0.894), and HCl monohydrate (0.850).[102] Methadone is also regulated internationally as a Schedule I controlled substance under the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961.[103][104]

Methadone clinics

[edit]In the United States, prescription of methadone requires intensive monitoring and must be obtained in-person from an Opioid Treatment Program—colloquially known as a 'methadone clinic'—when prescribed for opioid use disorder (OUD).[26] According to federal laws, methadone cannot be prescribed by a doctor and obtained from a pharmacy in order to treat addiction. Because of its long half-life, methadone is almost invariably prescribed to be taken in a single daily dose. At nearly all methadone clinics in the US, patients must visit a clinic to receive and take their dose under the supervision of a nurse. Both patients who are new to methadone treatment and high-risk patients—such as those who are using drugs and alcohol, including cannabis in some states—must visit the clinic daily.[105][106]

Other countries

[edit]In Russia, methadone treatment is illegal. In 2008, Chief Sanitary Inspector of Russia Gennadiy Onishchenko, claimed that Russian health officials are not convinced of the methadone's efficacy in treating heroin and/or opioid addicts. Instead of replacement therapy and gradual reduction of illicit drug abuse, Russian doctors encourage immediate cessation and withdrawal. Addicts are generally given sedatives and non-opioid analgesics in order to cope with withdrawal symptoms.[107] Brazilian footballer assistant Robson Oliveira was arrested in 2019 upon arriving in Russia with methadone tablets sold legally in other countries for what was considered drug trafficking under Russian law.[108]

As of 2015, China had the largest methadone maintenance treatment program with over 250,000 people in over 650 clinics in 27 provinces.[109]

References

[edit]- ^ "CSD Entry METHAD01: (6R)-Dimethylamino-4,4-diphenyl-3-heptanone, L-Methadone". Cambridge Structural Database: Access Structures. Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Bye E (1974). "Crystal Structures of Synthetic Analgetics. II. l-Methadone". Acta Chem. Scand. 28b: 5–12. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.28b-0005.

- ^ https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/consumers/cmi/m/Methatabs.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Bonewit-West K, Hunt SA, Applegate E (2012). Today's Medical Assistant: Clinical and Administrative Procedures. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 571. ISBN 9781455701506.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Fredheim OM, Moksnes K, Borchgrevink PC, Kaasa S, Dale O (August 2008). "Clinical pharmacology of methadone for pain". Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 52 (7): 879–889. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01597.x. PMID 18331375. S2CID 25626479.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Methadone Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ a b c Brown R, Kraus C, Fleming M, Reddy S (November 2004). "Methadone: applied pharmacology and use as adjunctive treatment in chronic pain" (PDF). Postgraduate Medical Journal. 80 (949): 654–659. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.022988. PMC 1743125. PMID 15537850. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 May 2014.

- ^ a b Toombs JD, Kral LA (April 2005). "Methadone treatment for pain states". American Family Physician. 71 (7): 1353–1358. PMID 15832538. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Joseph H, Stancliff S, Langrod J (2000). "Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT): a review of historical and clinical issues". The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, New York. 67 (5–6): 347–364. PMID 11064485.

- ^ World Health Organization (2009). Clinical Guidelines for Withdrawal Management and Treatment of Drug Dependence in Closed Settings. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- ^ a b c d Grissinger M (August 2011). "Keeping patients safe from methadone overdoses". P & T. 36 (8): 462–466. PMC 3171821. PMID 21935293.

- ^ "Methadone". The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ "Data table for Figure 1. Age-adjusted drug-poisoning and opioid-analgesic poisoning death rates: United States, 1999–2011" (PDF). CDC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L (December 2016). "Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2010-2015". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (50–51): 1445–1452. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1. PMID 28033313.

- ^ Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, Hansen RN, Sullivan SD, Blazina I, et al. (February 2015). "The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (4): 276–286. doi:10.7326/M14-2559. PMID 25581257. S2CID 207538295.

- ^ Methadone Matters: Evolving Community Methadone Treatment of Opiate Addiction. CRC Press. 2003. p. 13. ISBN 9780203633090. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015.

- ^ Kleiman MA, Hawdon JE (2011). "Diphenypropylamine Derivatives". Encyclopedia of Drug Policy. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781506338248. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015.

- ^ Kuehn, B. M. (2005). Methadone Treatment Marks 40 Years. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 294(8), 887–889. doi:10.1001/jama.294.8.887

- ^ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ "Opioid Use Disorder". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M (July 2009). Mattick RP (ed.). "Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (3): CD002209. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002209.pub2. PMC 7097731. PMID 19588333.

- ^ Stotts AL, Dodrill CL, Kosten TR (August 2009). "Opioid dependence treatment: options in pharmacotherapy". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 10 (11): 1727–1740. doi:10.1517/14656560903037168. PMC 2874458. PMID 19538000.

- ^ World Health Organization (2009). "Methadone maintenance treatment". Clinical guidelines for withdrawal management and treatment of drug dependence in closed settings. Manila : WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. hdl:10665/207032. ISBN 9789290614302.

- ^ Connock M, Juarez-Garcia A, Jowett S, Frew E, Liu Z, Taylor RJ, et al. (March 2007). "Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence: a systematic review and economic evaluation". Health Technology Assessment. 11 (9): 1–171, iii–iv. doi:10.3310/hta11090. PMID 17313907.

- ^ a b Anderson IB, Kearney TE (January 2000). "Use of methadone". The Western Journal of Medicine. 172 (1): 43–46. doi:10.1136/ewjm.172.1.43. PMC 1070723. PMID 10695444.

- ^ Kraychete DC, Sakata RK (July 2012). "Use and rotation of opioids in chronic non-oncologic pain". Revista Brasileira de Anestesiologia. 62 (4): 554–562. doi:10.1016/S0034-7094(12)70155-1. PMID 22793972.

- ^ Mercadante S, Bruera E (March 2016). "Opioid switching in cancer pain: From the beginning to nowadays". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 99: 241–248. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.12.011. PMID 26806145.

- ^ Leppert W (July 2009). "The role of methadone in cancer pain treatment--a review". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 63 (7): 1095–1109. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01990.x. PMID 19570126. S2CID 205875314.

- ^ Nicholson AB, Watson GR, Derry S, Wiffen PJ (February 2017). "Methadone for cancer pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (3): CD003971. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003971.pub4. PMC 6464101. PMID 28177515.

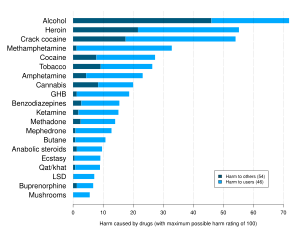

- ^ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ^ "Methadone Oral: Side Effects". WebMD. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Methadone". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Methadone". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 27 February 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Dolophine: Drug Description". RxList. Archived from the original on 3 September 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Methadone". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ John J, Amley X, Bombino G, Gitelis C, Topi B, Hollander G, et al. (December 2010). "Torsade de Pointes due to Methadone Use in a Patient with HIV and Hepatitis C Coinfection". Cardiology Research and Practice. 2010: 524764. doi:10.4061/2010/524764. PMC 3021856. PMID 21253542.

- ^ Brondani M, Park PE (16 May 2011). "Methadone and oral health--a brief review". Journal of Dental Hygiene. 85 (2): 92–98. PMID 21619737.

- ^ Graham CH, Meechan JG (October 2005). "Dental management of patients taking methadone". Dental Update. 32 (8): 477–8, 481–2, 485. doi:10.12968/denu.2005.32.8.477. PMID 16262036.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Methadone. Drugs and Human Performance Fact Sheets" (PDF). NHTSA.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sadovsky R (15 July 2000). "Tips from Other Journals – Public Health Issue: Methadone Maintenance Therapy". American Family Physician. 62 (2): 428–432. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015.

- ^ "Methadone Black Box Warnings - Drugs.com". drugs.com. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ Tran PN, Sheng J, Randolph AL, Baron CA, Thiebaud N, Ren M, et al. (2020). "Mechanisms of QT prolongation by buprenorphine cannot be explained by direct hERG channel block". PLOS ONE. 15 (11): e0241362. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1541362T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0241362. PMC 7647070. PMID 33157550.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Methadone (meth' a done)". MedlinePlus. National Institutes of Health. 1 February 2009. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ "Methadone overdose". MedlinePlus. 3 October 2017.

- ^ a b "Methadone overdose: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ a b Leavitt SB (September 2003). "Methadone Dosing & Safety in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction" (PDF). Addiction Treatment Forum.

- ^ Giacomuzzi SM, Ertl M, Vigl A, Riemer Y, Günther V, Kopp M, et al. (July 2005). "Driving capacity of patients treated with methadone and slow-release oral morphine". Addiction. 100 (7): 1027. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01148.x. PMID 15955021.

- ^ Reece AS (May 2008). "Experience of road and other trauma by the opiate dependent patient: a survey report". Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 3: 10. doi:10.1186/1747-597X-3-10. PMC 2396610. PMID 18454868.

- ^ "Methadone and Driving Article Abstracts: Brief Literature Review". Institute for Metropolitan Affairs, Roosevelt University. 14 February 2008. Archived from the original (DOC) on 3 November 2011.

- ^ Ford C, Barnard J, Bury J, Carnwath T, Gerada C, Joyce A, et al. (2005). Guidance for the use of methadone for the treatment of opioid dependence in primary care (PDF) (1st ed.). London: Royal College of General Practitioners. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2012.

- ^ "Increases in Methadone-Related Deaths:1999–2004". 4 September 2018. Archived from the original on 11 April 2010.

- ^ "The Killer Cure" Archived 18 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine The Charleston Gazette 2006

- ^ "Methadone-Associated Mortality, Report of a National Assessment". Archived from the original on 1 January 2016.

- ^ Finn S, Tuckwiller T (28 November 2006). "New warning issued on methadone". Charleston Gazette. Archived from the original on 13 February 2010.

- ^ Codd EE, Shank RP, Schupsky JJ, Raffa RB (1995). "Serotonin and norepinephrine uptake inhibiting activity of centrally acting analgesics: structural determinants and role in antinociception". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 274 (3): 1263–70. PMID 7562497.

- ^ Gorman AL, Elliott KJ, Inturrisi CE (February 1997). "The d- and l-isomers of methadone bind to the non-competitive site on the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor in rat forebrain and spinal cord". Neurosci. Lett. 223 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(97)13391-2. PMID 9058409.

- ^ a b Bengt Danielsson, Julius Collin, Anastasia Nyman, Annica Bergendal, Natalia Borg, Maria State, et al. (12 March 2020). "Drug use and torsades de pointes cardiac arrhythmias in Sweden: a nationwide register-based cohort study". BMJ Open. 10 (3): e034560. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034560. PMC 7069257. PMID 32169926.

- ^ a b c d Schulze V, Stoetzer C, O'Reilly AO, Eberhardt E, Foadi N, Ahrens J, et al. (January 2014). "The opioid methadone induces a local anaesthetic-like inhibition of the cardiac Na+ channel, Na(v)1.5". British Journal of Pharmacology. 171 (2): 427–437. doi:10.1111/bph.12465. PMC 3904262. PMID 24117196.

the clinical relevance of a Na+ channel blocker is probably better estimated from recordings on inactivated channels (IC50 ~10 μM in our study).

- ^ Davis MP, Glare P, Hardy JR, Columba Q, eds. (2009). Opioids in Cancer Pain (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-0-19-923664-0.

- ^ Xiao Y, Smith RD, Caruso FS, Kellar KJ (October 2001). "Blockade of rat alpha3beta4 nicotinic receptor function by methadone, its metabolites, and structural analogs". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 299 (1): 366–371. PMID 11561100. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ Kell MJ (1994). "Utilization of plasma and urine methadone concentrations to optimize treatment in maintenance clinics: I. Measurement techniques for a clinical setting". Journal of Addictive Diseases. 13 (1): 5–26. doi:10.1300/J069v13n01_02. PMID 8018740.

- ^ Eap CB, Déglon JJ, Baumann P (1999). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics of methadone: Clinical relevance" (PDF). Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems. 1 (1): 19–34.

- ^ a b c Eap CB, Buclin T, Baumann P (2002). "Interindividual variability of the clinical pharmacokinetics of methadone: implications for the treatment of opioid dependence". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 41 (14): 1153–1193. doi:10.2165/00003088-200241140-00003. PMID 12405865. S2CID 1396257.

- ^ Manfredonia JF (March 2005). "Prescribing methadone for pain management in end-of-life care". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 105 (3 Suppl 1): S18–S21. PMID 18154194. Archived from the original on 20 May 2007.

- ^ Medscape Methadone Dosage. [1].

- ^ Preston KL, Epstein DH, Davoudzadeh D, Huestis MA (September 2003). "Methadone and metabolite urine concentrations in patients maintained on methadone". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 27 (6): 332–341. doi:10.1093/jat/27.6.332. PMID 14516485.

- ^ Code of Federal Regulations, Title 42, Sec 8.

- ^ "Methadone Hydrochloride Tablets, USP" (PDF). VistaPharm. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013.

- ^ Murphy SB, Jackson WB, Pare JA (July 1978). "Talc retinopathy". Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. Journal Canadien d'Ophtalmologie. 13 (3): 152–156. PMID 698886.

- ^ Hill AD, Toner ME, FitzGerald MX (May 1990). "Talc lung in a drug abuser". Irish Journal of Medical Science. 159 (5): 147–148. doi:10.1007/BF02937408. PMID 2397985. S2CID 41611298.

- ^ Cappola TP, Felker GM, Kao WH, Hare JM, Baughman KL, Kasper EK (April 2002). "Pulmonary hypertension and risk of death in cardiomyopathy: patients with myocarditis are at higher risk". Circulation. 105 (14): 1663–1668. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000013771.30198.82. PMID 11940544. S2CID 298931.

- ^ Humbert M (February 2005). "Improving survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension". The European Respiratory Journal. 25 (2): 218–220. doi:10.1183/09031936.05.00129604. PMID 15684283.

- ^ Lintzeris N, Lenné M, Ritter A (August 1999). "Methadone injecting in Australia: a tale of two cities". Addiction. 94 (8): 1175–1178. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94811757.x. PMID 10615732.

- ^ Dales pharmaceuticals patients information leaflet revision 09/10[verification needed]

- ^ "BNF". NICE.

- ^ Strang J, Sheridan J, Hunt C, Kerr B, Gerada C, Pringle M (June 2005). "The prescribing of methadone and other opioids to addicts: national survey of GPs in England and Wales". The British Journal of General Practice. 55 (515): 444–451. PMC 1472740. PMID 15970068.

- ^ Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 941–5.

- ^ Bürgi HB, Dunitz JD, Shefter E (August 1973). "Pharmacological implications of the conformation of the methadone base". Nature. 244 (136): 186–187. doi:10.1038/newbio244186b0. PMID 4516455.

- ^ a b c d e f López-Muñoz F, Alamo C (April 2009). "The consolidation of neuroleptic therapy: Janssen, the discovery of haloperidol and its introduction into clinical practice". Brain Research Bulletin. 79 (2): 130–141. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.01.005. PMID 19186209. S2CID 7720401.

- ^ Bockmühl M, Ehrhart G (1949). "Über eine neue Klasse von spasmolytisch und analgetisch wirkenden Verbindungen, I" [On a new class of spasmolytic and analgesic compounds, I]. Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie (in German). 561 (1): 52–86. doi:10.1002/jlac.19495610107.

- ^ "Polamidon: Wirkung, Legalität, Substitution, Erfolgschancen & Entzug". My Way Betty Ford Klinik (in German). Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ Bockmühl M, Ehrhart G, Schaumann O (1948). Über eine neue Klasse von spasmolytisch und analgetisch wirkenden (About a new class of compounds with a spasmolytic and analgesic effect). Vol. 561. Justus Liebigs Ann. pp. 561, 52–85.

- ^ Defalque RJ, Wright AJ (October 2007). "The early history of methadone. Myths and facts". Bulletin of Anesthesia History. 25 (3): 13–16. doi:10.1016/S1522-8649(07)50035-1. PMID 20506765.

- ^ Overton DA, Batta SK (November 1979). "Investigation of narcotics and antitussives using drug discrimination techniques". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 211 (2): 401–408. PMC 8331839. PMID 41087.

- ^ Morphine & Allied Drugs, Reynolds et al 1957 Ch 8

- ^ "Methadone Briefing". Archived from the original on 20 November 2003. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ^ Indro-Online.de Archived 13 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine (PDF format)

- ^ Preston A, Bennett G (2003). "The History of Methadone and Methadone Prescribing.". In Tober G, Strang E (eds.). In: Methadone Matters. Evolving Community Methadone Treatment of Opiate Addiction. Taylor and Francis Group.

- ^ a b Browne-Miller A (2009). The Praeger International Collection on Addictions. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-275-99605-5.

- ^ Dole VP, Nyswander ME (May 1976). "Methadone maintenance treatment. A ten-year perspective". JAMA. 235 (19): 2117–2119. doi:10.1001/jama.1976.03260450029025. PMID 946538.

- ^ Based on:

- "Methadone Prices and Methadone Coupons » 5 mg". GoodRx, Inc. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.[unreliable source?]

- "Methadone Prices and Methadone Coupons » 40 mg". GoodRx, Inc. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.[unreliable source?]

- "WHOCC – ATC/DDD Index". WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ Walsh L (16 June 2015). "Insurance and Payments". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "Medicare Coverage of Substance Abuse Services" (PDF).

- ^ "Medicaid Coverage of Medications for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder" (PDF).

- ^ "Veterans Alcohol and Drug Dependence Rehabilitation Program". 1 November 2018.

- ^ "Methadone Maintenance Treatment". Drug Policy Alliance Lindesmith Library. Archived from the original on 11 May 2003.

- ^ "Methadone Research Web Guide". NIDA. Archived from the original on 15 February 2010.

- ^ National Institute on Drug Abuse. "How Much Does Opioid Treatment Cost?". Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "Is drug addiction treatment worth its cost?". Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ "DEA Diversion Control Division". Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ "DEA Diversion Control Division". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Nordegren T (1 March 2002). The A-Z Encyclopedia of Alcohol and Drug Abuse. Universal-Publishers. p. 366. ISBN 978-1-58112-404-0. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ "Methadone". www.samhsa.gov. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "42 CFR § 8.12 – Federal opioid treatment standards". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Schwirtz M (22 July 2008). "Russia Scorns Methadone for Heroin Addiction". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016.

- ^ "Caso Robson: Campanha pede justiça a ex-funcionário de Fernando preso há 562 dias na Rússia" [Robson case: Campaign calls for justice for former Fernando employee imprisoned 562 days in Russia]. ESPN Caso Robson (in Portuguese). 30 September 2020.

- ^ Sullivan SG, Wu Z, Rou K, Pang L, Luo W, Wang C, et al. (January 2015). "Who uses methadone services in China? Monitoring the world's largest methadone programme". Addiction. 110 (Suppl 1): 29–39. doi:10.1111/add.12781. PMID 25533862.

External links

[edit]- Methadone, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- Tapering off of methadone maintenance

- DE patent 711069, Dr Max Bockmuehl & Dr Gustav Ehrhart, "Verfahren zur Darstellung von basischen Estern", published 1941-09-25, issued 1941-09-25, assigned to IG Farbenindustrie AG

- 1937 in biology

- 1937 in Germany

- Benzhydryl compounds

- CYP2D6 inhibitors

- Dimethylamino compounds

- Drug rehabilitation

- Drugs developed by Eli Lilly and Company

- Euphoriants

- HERG blocker

- German inventions of the Nazi period

- German inventions

- Ketones

- Mu-opioid receptor agonists

- Synthetic opioids

- World Health Organization essential medicines