Punjabis

پنجابی ਪੰਜਾਬੀ पंजाबी | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. ~121 million[1][a] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 90,512,900[2][3] | |

| 28,200,000[1] | |

| 700,000[4] | |

| 430,705[5] | |

| 250,000[6] | |

| 71,228[7] | |

| 56,400[8] | |

| 54,000[9] | |

| 24,000[10] | |

| 23,700[11] | |

| 19,752[12] | |

| 808[13] | |

| Languages | |

| Pakistan: Western Punjabi and Urdu India: Eastern Punjabi and Hindi | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Islam in Pakistan Sikhism & Hinduism in India Minorities: | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Aryan peoples | |

| Part of a series on |

| Punjabis |

|---|

|

Punjab portal |

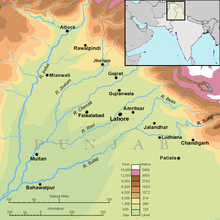

The Punjabis (Punjabi: پنجابی, ਪੰਜਾਬੀ, पंजाबी), or Punjabi people, are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group originating from the Punjab region, found in Pakistan and northern India. Punjab literally means the land of five waters (Persian: panj ("five") āb ("waters").[14] The name of the region was introduced by the Turko-Persian conquerors[15] of India and more formally popularised during the Mughal Empire.[14][16] Punjab is often referred to as the breadbasket in both Pakistan and India.[17][18]

The coalescence of the various tribes, castes and the inhabitants of the Punjab into a broader common "Punjabi" identity initiated from the onset of the 18th century CE. Prior to that the sense and perception of a common "Punjabi" ethno-cultural identity and community did not exist, even though the majority of the various communities of the Punjab had long shared linguistic, cultural and racial commonalities.[19][20][21]

Traditionally, Punjabi identity is primarily linguistic, geographical and cultural. Its identity is independent of historical origin or religion, and refers to those who reside in the Punjab region, or associate with its population, and those who consider the Punjabi language their mother tongue.[22] Integration and assimilation are important parts of Punjabi culture, since Punjabi identity is not based solely on tribal connections. More or less all Punjabis share the same cultural background.[23][24]

Historically, the Punjabi people were a heterogeneous group and were subdivided into a number of clans called biradari (literally meaning "brotherhood") or tribes, with each person bound to a clan. However, Punjabi identity also included those who did not belong to any of the historical tribes. With the passage of time tribal structures are coming to an end and are being replaced with a more cohesive[25] and holistic society, as community building and group cohesiveness[26][27] form the new pillars of Punjabi society.[28]

Geographic distribution

Independence and its aftermath

The 1947 independence of India and Pakistan, and the subsequent partition of Punjab, is considered by historians to be the beginning of the end of the British Empire.[29] The UNHCR estimates 14 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims were displaced during the partition.[30] To date, this is considered the largest mass migration in human history.[31]

Until 1947, the province of Punjab was ruled by a coalition comprising the Indian National Congress, the Sikh-led Shiromani Akali Dal and the Unionist Muslim League. However, the growth of Muslim nationalism led to the All India Muslim League becoming the dominant party in the 1946 elections. As Muslim separatism increased, the opposition from Punjabi Hindus and Sikhs increased substantially. Communal violence on the eve of Indian independence led to the dismissal of the coalition government, although the succeeding League ministry was unable to form a majority. Along with the province of Bengal, Punjab was partitioned on religious lines – the Muslim-majority West becoming part of the new Muslim state of Pakistan, and the Hindu and Sikh East remaining in India. Partition was accompanied by massive violence on both sides, claiming the lives of hundreds of thousands of people.[32] West Punjab was virtually cleansed of its Hindu and Sikh populations, who were forced to leave for India, while East Punjab and Delhi were virtually cleansed of the Muslim population.

By the 1960s, Indian Punjab underwent reorganisation as Sikh demands for an autonomous state increased. The Hindu-majority areas were formed into the states of Himachal Pradesh and Haryana respectively, making Sikhs the majority in the state of Punjab itself. In the 1980s, Sikh separatism combined with popular anger against the Indian Army's counter-insurgency operations (especially Operation Bluestar) led to violence and disorder in Indian Punjab, which only subsided in the 1990s. Political power in Indian Punjab is contested between the secular Congress Party and the Sikh religious party Akali Dal and its allies, the Bharatiya Janata Party. Indian Punjab remains one of the most prosperous of India's states and is considered the "breadbasket of India."

Subsequent to partition, West Punjabis made up a majority of the Pakistani population, and the Punjab province constituted 40% of Pakistan's total land mass. Today, Punjabis continue to be the largest ethnic group in Pakistan, accounting for half of the country's population. They reside predominantly in the province of Punjab, neighbouring Azad Kashmir in the region of Jammu and Kashmir and in Islamabad Capital Territory. Punjabis are also found in large communities in the largest city of Pakistan, Karachi, located in the Sindh province.

Punjabis in India can be found in the states of Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Delhi and the Union Territory of Chandigarh. Large communities of Punjabis are also found in the Jammu region of Jammu and Kashmir and in Rajasthan, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh. In Delhi,

Pakistani Punjabis

Punjabis make up about half of the population of Pakistan. The Punjabis found in Pakistan belong to groups known as biradaris. In addition, Punjabi society is divided into two divisions, the zamindar groups or qoums, traditionally associated with farming and the moeens, who are traditionally artisans. Some zamindars are further divided into groups such as the Mughals, Rajputs, Jats, Shaikhs or (Muslim Khatri), Gujjars, Awans, Arains, Malik, Gakhars, Dogars and Mian Rehmani. People from neighbouring regions, such as Kashmiris, Pashtun and Baluch, also form important elements in the Punjabi population. Major Moeen groups include the Lohar, Khateek, Rawal, Chhimba Darzi, Teli, Qassab, Mallaah, Dhobi, Muslim Sunars, Mirasi, who are associated with a particular crafts or occupation.[33][page needed]

Punjabi people have traditionally and historically been farmers and soldiers,[citation needed] which has transferred into modern times with their dominance of agriculture and military fields in Pakistan. In addition, Punjabis in Pakistan have been quite prominent politically, having had many elected members of parliament. As the most ardent supporters of a Pakistani state, the Punjabis in Pakistan have shown a strong predilection towards the adoption of the Urdu language but nearly all speak Punjabi, and still identify themselves as ethnic Punjabis.[citation needed] Religious homogeneity remains elusive as a predominant Islamic Sunni-Shia population with Ahmadiyya and Christian minority. A variety of related sub-groups exist in Pakistan and are often considered by many Pakistani Punjabis to be simply regional Punjabis including the Seraikis (who overlap and are often considered transitional with the Sindhis).

The recent definition of Punjabi people, in Pakistani Punjab, is not based on racial classification, common ancestry or endogamy,[34] but based on geographical and cultural basis and thus makes it a unique definition. In Pakistani Punjab, there is not a great emphasis on a single dialect of the language and Pakistani Punjabis speak many distinct dialects,[35][36] which include Hindko, Seraiki, Potohari or Pahari and still identify themselves as Punjabis. People from a few provinces of Pakistan have made Punjab their home in recent times and now their consecutive generations identify themselves as Punjabis. The largest community to assimilate in Punjabi culture and now identify themselves as Punjabis are Kashmiris which include noted personalities like Nawaz Sharif, Sheikh Rasheed, Hamid Mir and the most noted poet Muhammad Iqbal, to name a few. The second largest community after Kashmiris are people of India, who identify themselves as Punjabis. The other communities to assimilate in Punjabis include Baloch who can be found throughout Punjab, and Baltis. The welcoming nature of Punjab have led to successful integration of almost all ethnic groups in Punjab over time. The Urdu, Punjabi and other language speakers who arrived in Punjab in 1947[37][38] have now assimilated and their second and third generations identify themselves as Punjabis even though it is not the same in Sindh Pakistan where they form distinct ethnic groups.

Indian Punjabis

The Punjabi-speaking people make 2.83% of India's population as of 2001. The total number of Indian Punjabis is unknown due to the fact that ethnicity is not recorded in the Census of India. The Sikhs are largely concentrated in the modern-day state of Punjab forming 58% of the population with Hindus forming 38%.[39] Ethnic Punjabis are believed to account for at least 35% of Delhi's total population and are predominantly Hindi-speaking Punjabi Hindus.[40][41][42] Muslims in Delhi are 13% of the population. In Chandigarh, 80.78% people of the population are Hindus, 13.11% are Sikhs, 4.87% are Muslims and minorities are Christians, Buddhists and Jains.[43]

Like the Punjabi Muslim society, these various castes are associated with particular occupations or crafts.

Indian Punjab is also home to small groups of Muslims and Christian. Most of the East Punjab's Muslims (in today's states of Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Delhi and Chandigarh) left for West Punjab in 1947. However, a small community still exists today, mainly in Malerkotla and Qadian , the only Muslim princely state among the seven that formed the erstwhile Patiala and East Punjab States Union (PEPSU). The other six (mostly Sikh) states were: Patiala, Nabha, Jind, Faridkot, Kapurthala and Kalsia.

The Indian censuses record the native languages, but not the descent of the citizens. Linguistic data cannot accurately predict ethnicity: for example, Punjabis make up a large portion of Delhi's population but many descendants of the Punjabi Hindu refugees who came to Delhi following the partition of India now speak Hindi as their first language. Thus, there is no concrete official data on the ethnic makeup of Delhi and other Indian states.[42]: 8–10

The Punjab region within India maintains a strong influence on the perceived culture of India towards the rest of the world. Numerous Bollywood film productions use the Punjabi language in their songs and dialogue as well as traditional dances such as bhangra. Bollywood has been dominated by Punjabi artists including actors Prithviraj Kapoor, Raj Kapoor, Dev Anand, Vinod Khanna, Dharmendra, Shammi Kapoor, Rishi Kapoor, Shashi Kapoor, Kabir Bedi, Rajesh Khanna, Angad Singh, Amitabh Bacchan (from his mother's side), Pran, Prem Chopra, Vinod Mehra, Manoj Kumar, Akshay Kumar Sunny Deol, Anil Kapoor, Poonam Dhillon, Juhi Chawla, Hrithik Roshan and Kareena Kapoor, singers Mohammed Rafi, Mahendra Kapoor, and Narendra Chanchal. Punjabi Prime Ministers of India include Gulzarilal Nanda, Inder Kumar Gujral and Dr. Manmohan Singh. There are numerous players in the Indian cricket team both past and present including Bishen Singh Bedi, Kapil Dev, Mohinder Amarnath, Navjot Sidhu, Harbhajan Singh, Yuvraj Singh Virat Kohli, and Yograj Singh.

Emigration and diaspora

The Punjabi people have emigrated in large numbers to many parts of the world. In the early 20th century, many Punjabis began settling in the United States, including independence activists who formed the Ghadar Party. The United Kingdom has a significant number of Punjabis from both Pakistan and India. The most populous areas being London, Birmingham and Glasgow. In Canada (specifically Vancouver and Toronto) and the United States, (specifically California's Central Valley). In the 1970s, a large wave of emigration of Punjabis (predominately from Pakistan) began to the Middle East, in places such as the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. There are also large communities in East Africa including the countries of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. Punjabis have also emigrated to Australia, New Zealand and Southeast Asia including Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore and Hong Kong. Of recent times many Punjabis have also moved to Italy.

History of Punjab

Indigenous population flourished in this region, leading to a developed civilisation in 5th to 4th millennium BC,[44] the ancient Indus Valley Civilization. Also Buddhism remnants have been found like Mankiala which corroborate the Buddhist background of this region as well.

The remains of the ancient Indo-Aryan city of Taxila,[45] and many ornaments that have been found in this region,suggests that,[46] one of the centres of Indus Valley Civilization was established at many parts of Punjab, most notably Taxila and Harappa,[47] Punjab became a centre of early civilisation from around 3300 BC. According to Historians this region was ruled by many small kingdoms and tribes around 4th and 5th BC. The earliest known notable local king of this region was known as King Porus[48][49] and he fought a famous Battle of the Hydaspes[50] against Alexander. His kingdom, known as Pauravas, was situated between Hydaspes (modern Jhelum and Acesines (modern day Chenab).[48] These kings fought local battles to gain more ground.Taxiles or Omphis another local north Indian king, wanted to defeat his eastern adversary Porus in a turf war and he invited Alexander the Great to defeat Porus. This marked the first intrusion of the West in the Indian subcontinent and North India in general. But such was the valor of Porus and his kingdom forces in Punjab, that despite being defeated, he was appreciated by Alexander the Great for his skill and valor and he was granted further territories in the North.[51] The other Indian kings did not like the fact that Porus was now an ally of Western forces. In less than ten years another Indian king Chandragupta Maurya[52] defeated the forces and conquered the Northern Indian regions up to the Kabul river (in modern-day Afghanistan). Alexander mostly ruled this land with the help of local allies like Porus.[53]

Centuries later, areas of the Punjab region were ruled by local kings followed by the Ghaznavids, Ghurids, Mughals, and others. Islam arrived in Punjab when the Muslim Umayyad army led by Muhammad bin Qasim conquered Sindh in 711 AD, by defeating Raja Dahir. Some of the Muslims are said to have settled in the region and adopted the local culture. Centuries later, the Ghaznavids introduced aspects of foreign Persian and Turkic culture in Punjab.

The earliest written Punjabi dates back to the writing of Sufi Muslim poets of the 11th Century. Its literature spread Punjab's unique voice of peace and spirituality to the entire civilisation of the region.

Regions of North India and Punjab were annexed into the Afghan Durrani Empire later on in 1747, being a vulnerable target.[54] But Afghan rule in Punjab was very short lived as many local tribal people like Gakhars fought against Afghan rule and took the lands back. The grandson of Ahmed Shah Durrani (Zaman Shah Durrani), lost it to Ranjit Singh, a Punjabi Sikh. He was born in 1780 to Maha Singh and Raj Kaur in Gujranwala, Punjab. Ranjit took a leading role in organising a Sikh militia and got control of the Punjab region from Zaman Shah Durrani. Ranjit started a Punjabi military expedition to expand his territory.[55] Under his command the Sikh army began invading neighbouring territories outside of Punjab. The Jamrud Fort at the entry of Khyber Pass was built by Ranjit Singh.[56] The Sikh Empire slowly began to weaken after the death of Hari Singh Nalwa at the Battle of Jamrud in 1837. Two years later, in 1839, Ranjit Singh died and his son took over control of the empire. By 1850 the British took over control of the Punjab region after defeating the Sikhs in the Anglo-Sikh wars,[57][58] establishing their rule over the region for around the next 100 years as a part of the British Raj. Many Sikhs and Punjabis later pledged their allegiance to the British, serving as sepoys (native soldiers) within the Raj.

Religions

People of Punjab remained tolerant throughout the history and that is why many different religious ideologies were tolerated there despite some uproar by some religious extremists. The region of Punjab is the birthplace of one monotheistic religion that is known as Sikhism.[59][60] Also many well known followers of Sufism[61] were born in Punjab.[62]

Due to religious tensions, emigration between Punjabi people started far before the partition and dependable records.[64][65] Shortly prior to the Partition of British India, Punjab had a slight majority Muslim population at about 53.2% in 1941, which was an increase from the previous years.[66] With the division of Punjab and the subsequent independence of Pakistan and later India, mass migrations of Muslims from Indian Punjab to Pakistan, and those of Sikhs and Hindus from Pakistan to Indian Punjab occurred. Today, the majority of Pakistani Punjabis follow Islam with a small Christian minority, while the majority of Indian Punjabis are either Sikhs or Hindus with a Muslim minority. Punjab is also the birthplace of Sikhism and the Islamic reform movement Ahmadiyya.[67]

Following the independence of Pakistan and the subsequent partition of British India, a process of population exchange took place in 1947 as Muslims began to leave India and headed to the newly created Pakistan and Hindus and Sikhs left Pakistan[68] for the newly created state of India.[69] As a result of these population exchanges, both parts are now relatively homogeneous, where religion is concerned.

- Population trends for major religious groups in the Punjab Province of British India (1881–1941)[63]

| Religious group |

Population % 1881 |

Population % 1891 |

Population % 1901 |

Population % 1911 |

Population % 1921 |

Population % 1931 |

Population % 1941 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam | 47.6% | 47.8% | 49.6% | 51.1% | 51.1% | 52.4% | 53.2% |

| Hinduism | 43.8% | 43.6% | 41.3% | 35.8% | 35.1% | 30.2% | 29.1% |

| Sikhism | 8.2% | 8.2% | 8.6% | 12.1% | 12.4% | 14.3% | 14.9% |

| Christianity | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.8% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Other religions / No religion | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 1.6% | 1.3% |

Punjabi Muslims

The people of Punjab were mainly Hindus with a Buddhist minority, when the Umayyad Muslim army led by Muhammad bin Qasim conquered Punjab and Sindh in 711 AD. Following this a variety of Muslim dynasties and kingdoms ruled the Punjab region, including Ghaznavids under Mahmud of Ghazni,[70][71][72] the Delhi Sultanate, the Mughal Empire and finally the Durrani Empire. The province became an important centre and Lahore was made into a second capital of the Turk Ghaznavid Empire. The Delhi Sultanate and later Mughal Empire ruled the region. The Punjab region became predominantly Muslim due to missionary Sufi saints whose dargahs dot the landscape of Punjab region. Sufis played a major role in the establishment of the literary and cultural traditions of the region, and comprised the educated elites of the Punjab for many centuries. Early classical Punjabi epics, such as Heer Ranjha were written by the sufi, Waris Shah.[73] Muslims established Punjabi literature, utilised Shahmukhi as the predominant script of the Punjab, as well as made major contributions to the music, art, cuisine and culture of the region. The Mughals controlled the region from 1524 until 1739 and would also lavish some parts of the province with building projects such as the Shalimar Gardens and the Badshahi Mosque, both situated in Lahore. The Muslim establishment in the Punjab occurred over a period of several centuries lasting until towards the end of the British Raj and the division of the Punjab province between Pakistan and India in August 1947. After the independence of Pakistan in 1947, the minority Hindus and Sikhs migrated to India while the Muslim refugees from India settled in the Pakistan.[74][75] Today Muslims constitute only 1.53% of Eastern Punjab in India as now the majority of Muslims live in Western Punjab in Pakistan.

The vast majority of Pakistan's population are native speakers of the Punjabi language and it is the most spoken language in Pakistan. The majority of Pakistani Punjabis speak the standard Punjabi dialect of Majhi, which is considered the Punjabi dialect of the educated class, as well as Lahnda (including Hindko and Saraiki).

Punjabi Hindus

In the pre-Islamic era and before the birth of Sikhism, the population of Punjab mainly followed Hinduism. Today Punjabi Hindus are mostly found in Indian Punjab and in neighbouring states like Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and Delhi, which together forms a part of the historical greater Punjab region. Many of the Hindu Punjabis from the Indian capital Delhi are immigrants and their descendants, from various parts of Western Pakistani Punjab. Some Punjabi Hindus can also be found in the surrounding areas as well as the recent cosmopolitan migrants in other big cities like Mumbai. There has also been continuous migration of Punjabi Hindus to western countries like USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, European Union, UAE and UK.

The Hindu Punjabis speak different dialects including Lahnda, as well as Majhi (Standard Punjabi) and others like Doabi and Malwi. Some still have managed to retain the Punjabi dialects spoken in Western Punjab, but many have also adopted Hindi.

Punjabi Sikhs

At the beginning of the fifteenth century, the religion of Sikhism was born, and during the Mughal period its Misls gradually emerged as a formidable military force, however, their rebellion was crushed by the Mughals when the Sikhs were defeated at Gurdas Nangal. Nearly a century later emerged the Sikh Empire. After fighting Ahmad Shah Durrani, the Sikhs wrested control of the Punjab from his descendants and ruled in a confederacy, which later became the Sikh Empire of the Punjab under Maharaja Ranjit Singh. A denizen of the city of Gujranwala, the capital of Ranjit Singh's empire was Lahore.[76] The Sikhs made architectural contributions to the city, utilising predominantly Mughal architectural practices. The Sikh Empire fell to the British only a few decades after it had arisen and the Sikhs played a major role in the British military under the British Raj.

Punjabi Christians

The death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in the summer of 1839 brought political chaos and the subsequent battles of succession and the bloody infighting between the factions at court weakened the state. Relationships with neighbouring British territories then broke down, starting the First Anglo-Sikh War; this led to a British official being resident in Lahore and the annexation of territory south of the Sutlej to British India.

In 1877, on St. Thomas' Day at Westminster Abbey, London, Rev Thomas Valpy French was appointed the first Anglican Bishop of Lahore, a large diocese which included all of the Punjab, then under British colonial rule, and remained so until 1887, during this period he also opened the Divinity College, Lahore in 1870.[77][78][79] Rev Thomas Patrick Hughes served as a Church Missionary Society missionary at Peshawar (1864–84), and became an oriental scholar, and compiled a 'Dictionary of Islam' (1885).[80]

Missionaries accompanied the colonising forces from Portugal, France, and Great Britain. Christianity was mainly brought by the British rulers of India in the later 18th and 19th century[citation needed]. This is evidenced in cities established by the British, such as the port city of Karachi, where the majestic St. Patrick's Cathedral[citation needed], Pakistan's largest church stands, and the churches in the city of Rawalpindi, where the British established a major military cantonment. American missionaries also played a significant part proselytizing in Punjab.[81]

The total number of Punjabi Christians in Pakistan is approximately 2,800,000 and 300,000 in Indian Punjab. Of these, approximately half are Roman Catholic and half Protestant. Many of the modern Punjabi Christians are descended from converts during British rule, however, other modern Punjabi Christians have converted from Churas. The Churas were largely converted to Christianity in North India during the British raj. The vast majority were converted from the Mazhabi Sikh communities of Punjab, and to a lesser extent Hindu Churas; under the influence of enthusiastic British army officers and Christian missionaries. Consequently, since the independence they are now divided between Pakistani Punjab and Indian Punjab. Large numbers of Mazhabi Sikhs were also converted in the Moradabad district and the Bijnor district[82] of Uttar Pradesh. Rohilkhand saw a mass conversion of its entire population of 4500 Mazhabi Sikhs into the Methodist Church.[83] Sikh organisations became alarmed at the rate of conversions among the Mazhabi Sikhs and responded by immediately dispatching Sikh missionaries to counteract the conversions[citation needed].

Culture

Punjabi culture is the culture of the Punjab region. It is one of the oldest and richest cultures in world history, dating from ancient antiquity to the modern era. The Punjabi culture is the culture of the Punjabi people, who are now distributed throughout the world. The scope, history, sophistication and complexity of the culture are vast. Some of the main areas include Punjabi poetry, philosophy, spirituality, artistry, dance, music, cuisine, military weaponry, architecture, languages, traditions, values and history. Historically, the Punjab/Punjabis, in addition to their rural-agrarian lands and culture, have also enjoyed a unique urban cultural development in two great cities, Lahore[84] and Amritsar.[85]

Role of women

In the traditional Punjabi culture women look after the household and children. Also women in general manage the finances of the household. Moreover, Punjabi women fought in the past along with the men when the time arose. Majority of Punjabi women were considered as warriors upon a time, they excelled in the art of both leadership and war. They are still considered and treated as leaders among many Punjabi villages. In certain divisions Punjabi philosophy states that Men are raised to be warriors and women are raised to be leaders. Mai Bhago is a good example in this regard. Punjabi women also have the strong literary tradition. Peero Preman was the first Punjabi woman poet of the mid 18th century.[86][87] She was followed by many other women of repute.

Language

Punjabi is the most spoken language in Pakistan and eleventh most spoken language in India. According to the Ethnologue 2005 estimate,[88] there are 130 million native speakers of the Punjabi language, which makes it the ninth most widely spoken language in the world. According to the 2008 Census of Pakistan,[89] there are approximately 76,335,300 native speakers of Punjabi in Pakistan, and according to the Census of India, there are over 29,102,477 Punjabi speakers in India.[90] Punjabi is also spoken as a minority language in several other countries where Punjabis have emigrated in large numbers, such as the United Kingdom (where it is the second most commonly used language[91]) and Canada, in which Punjabi has now become the fourth most spoken language after English, French and Chinese, due to the rapid growth of immigrants from Pakistan and India.[92] There are also sizeable communities in the United States, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Persian Gulf countries, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand.

Punjabis are linguistically and culturally related to the other Indo-Aryan peoples of South Asia. There are an estimated 102 million Punjabi speakers around the world.[93] If regarded as an ethnic group, they are among the world's largest. In South Asia, they are the second largest ethnic group after the Bengali People.

The main language of the Punjabi people is Punjabi and its associated dialects, which differ depending on the region of Punjab the speaker is from; there are notable differences in the Lahnda languages, spoken in the Pakistani Punjab. In the Pakistani Punjab, the vast majority still speak Punjabi, even though the language has no governmental support. In the Indian Punjab, most people speak Punjabi. English is sometimes used, and older people who lived in the undivided Punjab may be able to speak and write in Urdu. The Punjabi languages have always absorbed numerous loanwords from surrounding areas and provinces (and from English).

Cuisine

Punjabi cuisine has an immense range of dishes and has become world-leader in the field; so much so that many entrepreneurs that have invested in the sector have built large personal fortunes due to the popularity of Punjabi cuisine throughout the world. Punjabi cuisine uses unique spices.[94]

Music

Bhangra describes dance-oriented popular music with Punjabi rhythms, developed since the 1980s. The name refers to one of the traditional and folkloric Punjabi dances. Bhangra music is appreciated all over the globe. Sufi music and Qawali are other important genres in Punjab.[95][96]

Dance

Owing to the long history of the Punjabi culture and of the Punjabi people, there are a large number of dances normally performed at times of celebration, the time of festivals known as Melas and the most prominent dances are at Punjabi weddings, where the elation is usually particularly intense. Punjabi dances are performed either by men or by women. The dances range from solo to group dances and also sometimes dances are done along with musical instruments like Dhol, Flute, Supp, Dhumri, Chimta etc. Other common dances that both men and women perform are Karthi, Jindua, and Dandass.[97] "Bhangra" dance is the most famous aspect of Punjabi dance tradition. Its popularity has attained a level where a music is produced with the intent of aiding people to carry out this form of dancing.

Wedding traditions

Punjabi wedding traditions and ceremonies are conducted in Punjabi, and are a strong reflection of Punjabi culture. Many local songs are a part of the wedding and are known as boliyan.[98] While the actual religious marriage ceremony among Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus, and Jains may be conducted in Arabic, Punjabi, Sanskrit, by the Kazi, Pandit or Granthi, there are also many commonalities in ritual, song, dance, food, make-up and dress.

The Punjabi wedding has many rituals and ceremonies that have evolved since traditional times. Punjabi receptions of all sorts are known to be very energetic, filled with loud Bhangra music, people dancing, and a wide variety of Punjabi food. Alcohol consumption by the menfolk is part of the tradition amongst Hindu and some Sikh communities that allow it.

Folk tales

The folk tales of Punjab include many stories[99] which are passing through generations and includes folk stories like Heer Ranjha, Mirza Sahiban,[100] Sohni Mahiwal etc. to name a few.

Festivals

Vaisakhi, Jashan-e-Baharan, Basant, Kanak katai da mela ( Wheat cutting celebrations ) and many more. The jagrātā, also called jāgā or jāgran, means an all night vigil. This type of vigil is found throughout India and is usually held to worship a deity with song and ritual. The goal is to gain the favour of the Goddess, to obtain some material benefit, or repay her for one already received. The Goddess is invoked by the devotees to pay them a visit at the location of the jagrātā, whether it be in their own homes or communities, in the form of a flame.[101]

Traditional dress

The Punjabi traditional clothing is very diverse and for various occasions various clothing is chosen. It includes Shalwar Kameez, Kurta, Achkan and Dhoti in men while in women there is wide range of clothing but mainly it comprises Shalwar Kameez, Patiala salwar, Punjabi suit, Churidars with Dupatta with traditional Paranda Ghari worn on the hair. Khaddi topi (Embroidered cap) is also worn by some women with dupatta on special occasions. Shalwar Kameez and Sherwani are for formal occasions and office work while Dhoti is mostly worn by people who are involved in farming throughout Punjab. The shorter version of Dhoti that is unique to Punjab is known as Chatki with close resemblance to Kilt but use of Chatki for formal occasions is very very rare and not many people are familiar with Chatkis. Punjabi Jutti and Tillay wali Jutti is a very famous footwear for both men and women in Punjab. In men Pagri (turban) is also worn as a traditional cap in many occasions. Dupatta with embroidery of different styles with Matthay da Tikka is also very famous in Punjabi culture.

Sports

Various types of sports are played in Punjab. They are basically divided into outdoor and indoor sports. Special emphasis is put to develop both the mental and physical capacity while playing sports. That is why recently sports like Speed reading, Mental abacus, historical and IQ tests are arranged as well. Indoor sports are specially famous during the long summer season in Punjab. Also indoor sports are played by children in homes and in schools. Gilli-danda is vary famous indigenous sports among children along with Parcheesi. Pittu Garam is also famous among children. Stapu is famous among young girls of Punjab. Also many new games are included with the passage of time. The most notable are Carrom, Ludo (board game), Scrabble, Chess, Draughts, Go Monopoly. The Tabletop games games include billiards and snooker. Backgammon locally known as Dimaagi Baazi( Mental game) is famous in some regions as well.

The outdoor sports include Kusti (a wrestling sport), Kabaddi, Rasa Kashi (a rope pulling game), Patang (Kite Flying) and Naiza Baazi or Tent pegging (a cavalry sport).Gatka, is also taken as a form of sports, Punjabi's are naturally dominant in sports because of their physical attributes and genetic advantage. Punjab being part of South Asia, the sport of cricket is very popular. New forms of sports are also being introduced and adopted in particular by the large overseas Punjabis, such as Ice hockey, Soccer, Boxing, Mixed martial arts as part of the globalisation of sports.

Notable people

See also

Notes

- ^ Includes only Punjabi language-speaking populations.

References

- ^ a b Lahnda/Western Punjabi 90,512,900 Pakistan (2014). Eastern Punjabi: 28,200,000 India (2001), other countries: 1,314,770. Ethnologue 19.

- ^ Pakistan - Languages | Ethnologue

- ^ Ethnic Groups - The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency

- ^ McDonnell, John (5 December 2006). "Punjabi Community". House of Commons. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

We now estimate the Punjabi community at about 700,000, with Punjabi established as the second language certainly in London and possibly within the United Kingdom.

- ^ "Census Profile". 6 May 2015.

- ^ http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/population/ancestry_language_spoken_at_home.html

- ^ http://mcnair.com.au/wp-content/uploads/McNair-Ingenuity-Research-In-Language-Media-Consumption-Infographic.pdf

- ^ "Malaysia".

- ^ "Libya".

- ^ Strazny, Philipp (1 February 2013). "Encyclopedia of Linguistics". Routledge – via Google Books.

- ^ "Bangladesh".

- ^ http://www.stats.govt.nz/~/media/Statistics/Census/2013%20Census/data-tables/totals-by-topic/totals-by-topic-tables.xls

- ^ http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/sources/census/wphc/Nepal/Nepal-Census-2011-Vol1.pdf

- ^ a b Gandhi, Rajmohan (2013). Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten. New Delhi, India, Urbana, Illinois: Aleph Book Company. ISBN 978-93-83064-41-0.

- ^ Canfield, Robert L. (1991). Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 1 ("Origins"). ISBN 0-521-52291-9.

- ^ Shimmel, Annemarie (2004). The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture. London, United Kingdom: Reaktion Books Ltd. ISBN 1-86189-1857.

- ^ "Punjab, bread basket of India, hungers for change". Reuters. 30 January 2012.

- ^ "Columbia Water Center Released New Whitepaper: "Restoring Groundwater in Punjab, India's Breadbasket" – Columbia Water Center". Water.columbia.edu. 7 March 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Malhotra, edited by Anshu; Mir, Farina (2012). Punjab reconsidered : history, culture, and practice. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198078012.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Ayers, Alyssa (2008). "Language, the Nation, and Symbolic Capital: The Case of Punjab" (PDF). Journal of Asian Studies. 67 (3): 917–46. doi:10.1017/s0021911808001204.

- ^ Thandi, edited and introduced by Pritam Singh and Shinder S. (1996). Globalisation and the region : explorations in Punjabi identity. Coventry, United Kingdom: Association for Punjab Studies (UK). ISBN 1874699054.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Thandi, edited by Pritam Singh, Shinder Singh (1999). Punjabi identity in a global context. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019-564-8641.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Singh, Prtiam (2012). "'Globalisation and Punjabi Identity: Resistance, Relocation and Reinvention (Yet Again!)'" (PDF). Journal of Punjab Studies. 19 (2): 153–72.

- ^ "Languages : Indo-European Family". Krysstal.com. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Albert V., Carron; Lawrence R. Brawley (December 2012). "Cohesion: Conceptual and Measurement Issues". http://sgr.sagepub.com/ : Small Group Research. 43 (6).

{{cite journal}}: External link in|journal= - ^ http://www.oecd.org/dev/pgd/internationalconferenceonsocialcohesionanddevelopment.htm : The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Webpage for Group Cohesiveness

- ^ Mukherjee, Protap; Lopamudra Ray Saraswati (20 January 2011). "Levels and Patterns of Social Cohesion and Its Relationship with Development in India: A Woman's Perspective Approach" (PDF). Ph.D. Scholars, Centre for the Study of Regional Development School of Social Sciences Jawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi – 110 067, India.

- ^ Thandi, edited and introduced by Pritam Singh and Shinder S. (1996). Globalisation and the region : explorations in Punjabi identity. Coventry, United Kingdom: Association for Punjab Studies (UK). ISBN 1-874699-054.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Lloyd, Trevor Owen (1996). The British Empire 1558–1995. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-873134-5. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Rupture in South Asia" (PDF). UNHCR. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ Dr Crispin Bates (23 December 2015). "The Hidden Story of Partition and its Legacies". BBC. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ Ahmed, Ishtiaq (2012). The Punjab bloodied, partitioned and cleansed : unravelling the 1947 tragedy through secret British reports and first-person accounts. Karachi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199064709.

- ^ Muslim Peoples: A World Ethnographic Survey Richard V. Weekes, editor-in-chief Greenwood Press 1978

- ^ Brian Schwimmer. "Endogamy". Home.cc.umanitoba.ca.

- ^ dialect – definition and examples of dialects in linguistics. Grammar.about.com (15 July 2013).

- ^ UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile. Lmp.ucla.edu.

- ^ Bint photoBooks on INTernet: The Great Migration India Pakistan 1947 Life Magazine Margaret Bourke-White Sunil Janah Photojournalism Photography. Bintphotobooks.blogspot.de (11 April 2011).

- ^ Migration on India-Pakistan Partition of Punjab. YouTube (25 January 2011).

- ^ "Census 2011: %age of Sikhs drops in Punjab; migration to blame?". The Times of India.

- ^ indiatvnews (6 February 2015). "Delhi Assembly Elections 2015: Important Facts And Major Stakeholders Mobile Site". India TV News. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ^ Jupinderjit Singh. "Why Punjabis are central to Delhi election". http://www.tribuneindia.com/news/sunday-special/perspective/why-punjabis-are-central-to-delhi-election/36387.html. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ a b Sanjay Yadav (2008). The Invasion of Delhi. Worldwide Books. ISBN 978-81-88054-00-8.

- ^ http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/C-01/DDW04C-01%20MDDS.XLS

- ^ "Taxila, Pakistan: Traditional and Historical Architecture". Orientalarchitecture.com.

- ^ Jona Lendering (28 May 2008). "Taxila". Livius.org.

- ^ "Indus Valley Civilization". Harappa.com. 1 February 2010.

- ^ "The Ancient Indus Valley and the British Raj in India and Pakistan". Harappa.com.

- ^ a b Jona Lendering. "Porus". Livius.org.

- ^ "Alexander The Great in India at Jhelum with Porus, the Indian rajah". Padfield.com.

- ^ __start__ (4 April 2012). "Battle of Hydaspes ( Jhelum Punjab)_Alexander vs Porus ( Local King in Punjab, Former North India)". YouTube.

- ^ "Alexander the Great (Alexander of Macedon) Biography". Historyofmacedonia.org.

- ^ "Biographies: Chandragupta Maurya :: 0 A.D." Wildfire Games.

- ^ Kivisild et al. (2003)

- ^ "The History of Afghanistan". Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ Category: The Sikh Empire [1799 – 1839] (14 April 2012). "ARMY OF MAHARAJA RANJIT SINGH – The Sikh Empire [1799 – 1839]". Thesikhencyclopedia.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Jamrud Fort 1870". Softserv-intl.com.

- ^ "thefirstanglosikhwar.com". thefirstanglosikhwar.com.

- ^ "Untitled Document".

- ^ http://www.sikhs.org/summary.htm : Sikh Religious Philosophy

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/sikhism/ : BBC Report about the Sikh Religion

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/subdivisions/sufism_1.shtml : BBC report about Sufism

- ^ Gaur, edited by Surinder Singh, Ishwar Dayal (2009). Sufism in Punjab : mystics, literature, and shrines. Delhi: Aakar Books. ISBN 8189833936.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Gopal Krishan. "Demography of the Punjab (1849-1947)" (PDF). Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ Jones. (2006). Socio-religious reform movements in British India (The New Cambridge History of India). Cambridge University Press

- ^ Jones, R. (2007). The great uprising in India, 1857–58: Untold stories, Indian and British (worlds of the east India company). Boydell Press.

- ^ "Journal of Punjab Studies - Center for Sikh and Punjab Studies - UC Santa Barbara" (PDF).

- ^ "IslamAhmadiyya – Ahmadiyya Muslim Community – Al Islam Online – Official Website". Alislam.org.

- ^ .South Asia: British India Partitioned

- ^ Avari, B. (2007). India: The ancient past. ISBN 978-0-415-35616-9

- ^ John Louis Esposito, Islam the Straight Path, Oxford University Press, 15 January 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Lewis (1984), pp. 10, 20

- ^ Ali, Abdullah Yusuf (1991). The Holy Quran. Medina: King Fahd Holy Qur-an Printing Complex, pg. 507

- ^ Waqar Pirzada, Chasing Love Up against the Sun, Xlibris, p. 12

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Peers, Gooptu. (2012). India and the British empire (oxford history of the British empire companion). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Bryant, G. (2013). The emergence of British power in India, 1600–1784 (worlds of the east India company). BOYE6.

- ^ Sikh Period – Government of Pakistan. Heritage.gov.pk (14 August 1947).

- ^ Churches and Ministers: Home and Foreign Events New York Times, 13 January 1878.

- ^ An Heroic Bishop Chapter VI. His Fourth Pioneer Work: The Lahore Bishopric.

- ^ Beginnings in India By Eugene Stock, D.C.L., London: Central Board of Missions and SPCK, 1917.

- ^ British Library. Mundus.ac.uk (18 July 2002).

- ^ Singh, Maina Chawla (1999). Gender, religion, and the "heathen lands" : American missionary women in South Asia, 1860s-1940s. New York: Garland Pub. p. 45, 60, 188, 95. ISBN 9780815328247. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Alter, J.P and J. Alter (1986) In the Doab and Rohilkhand: north Indian Christianity, 1815–1915. I.S.P.C.K publishing p183

- ^ Alter, J.P and J. Alter (1986) In the Doab and Rohilkhand: north Indian Christianity, 1815–1915. I.S.P.C.K publishing p196

- ^ For various notable Punjabis belonging to this venerable city, please also see List of families of Lahore

- ^ Ian Talbot, 'Divided Cities: Lahore and Amritsar in the aftermath of Partition', Karachi:OUP, 2006, pp.1–4 ISBN 0-19-547226-8

- ^ "Piro Preman".

- ^ Malhotra, Anshu. "Telling her tale? Unravelling a life in conflict in Peero’s Ik Sau Saṭh Kāfiaṅ. (one hundred and sixty kafis)." Indian Economic & Social History Review 46.4 (2009): 541-578.

- ^ Ethnologue. 15th edition (2005).

- ^ According to statpak.gov.pk 44.15% of the Pakistani people are native Punjabi speakers. This gives an approximate number of 76,335,300 Punjabi speakers in Pakistan.

- ^ Census of India, 2001

- ^ "Punjabi Community". The United Kingdom Parliament.

- ^ "Punjabi is 4th most spoken language in Canada" The Times of India

- ^ Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin. Asterisks mark the 2010 estimates for the top dozen languages.

- ^ http://www.vahrehvah.com/punjab : Website for the dishes of Punjab

- ^ Pande, Alka (1999). Folk music & musical instruments of Punjab : from mustard fields to disco lights. Ahmedabad [India]: Mapin Pub. ISBN 18-902-0615-6.

- ^ Thinda, Karanaila Siṅgha (1996). Pañjāba dā loka wirasā (New rev. ed.). Paṭiālā: Pabalikeshana Biūro, Pañjābī Yūniwarasiṭī. ISBN 8173802238.

- ^ Folk dances of Punjab

- ^ Boliyan book. Infinity Squared Books. 2010. ISBN 978-0-9567818-0-2.

- ^ Tales of the Punjab. Digital.library.upenn.edu.

- ^ Peelu: The First Narrator of the Legend of Mirza-SahibaN. Hrisouthasian.org.

- ^ Erndl, Kathleen M. (1 June 1991). "Fire and wakefulness: the Devī jagrātā in contemporary Panjabi Hinduism". Journal of the American Academy of Religion: 339–360.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)

References and further reading

- Mohini Gupta, Encyclopaedia of Punjabi Culture & History – Vol. 1 (Window on Punjab) [Hardcover], ISBN 978-81-202-0507-9

- Iqbal Singh Dhillion, Folk Dances of Punjab ISBN 978-81-7116-220-8

- Punjabi Culture: Punjabi Language, Bhangra, Punjabi People, Karva Chauth, Kila Raipur Sports Festival, Lohri, Punjabi Dhabha, ISBN 978-1-157-61392-3

- Kamla C. Aryan, Cultural Heritage of Punjab ISBN 978-81-900002-9-1

- Shafi Aqeel, Popular Folk Tales from the Punjab ISBN 978-0-19-547579-1

- Online Book of Punjabi Folk Tales, https://archive.org/stream/KamalKahanisaeedBhuttaABookOnPunjabiFolktales/KamalKahaniReviewByHassnainGhayoor#page/n0/mode/2up

- Colloquial Panjabi: The Complete Course for Beginners (Colloquial Series) ISBN 978-0-415-10191-2

- Gilmartin, David. Empire and Islam: Punjab and the Making of Pakistan. Univ of California Press (1988), ISBN 0-520-06249-3.

- Grewal, J.S. and Gordon Johnson. The Sikhs of the Punjab (The New Cambridge History of India). Cambridge University Press; Reprint edition (1998), ISBN 0-521-63764-3.

- Latif, Syed. History of the Panjab. Kalyani (1997), ISBN 81-7096-245-5.

- Sekhon, Iqbal S. The Punjabis : The People, Their History, Culture and Enterprise. Delhi, Cosmo, 2000, 3 Vols., ISBN 81-7755-051-9.

- Singh, Gurharpal. Ethnic Conflict in India : A Case-Study of Punjab. Palgrave Macmillan (2000).

- Singh, Gurharpal (Editor) and Ian Talbot (Editor). Punjabi Identity: Continuity and Change. South Asia Books (1996), ISBN 81-7304-117-2.

- Singh, Khushwant. A History of the Sikhs – Volume 1.Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-562643-5

- Steel, Flora Annie. Tales of the Punjab : Told by the People (Oxford in Asia Historical Reprints). Oxford University Press, USA; New Ed edition (2002), ISBN 0-19-579789-2.

- Tandon, Prakash and Maurice Zinkin. Punjabi Century 1857–1947, University of California Press (1968), ISBN 0-520-01253-4.

Pakistan, India

This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}}

This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Wikipedia:Copyrights for more information.

- DNA boundaries in South and Southwest Asia, BMC Genetics 2004, 5:26

- Ethnologue Eastern Panjabi

- Ethnologue Western Panjabi

- Pakistan Census

- "The Genetic Heritage of the Earliest Settlers Persists Both in Indian Tribal and Caste Populations" (PDF). Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72: 313–332. 2003. doi:10.1086/346068. PMC 379225. PMID 12536373.

- Talib, Gurbachan (1950). Muslim League Attack on Sikhs and Hindus in the Punjab 1947. India: Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee.Online 1 Online 2 Online 3 (A free copy of this book can be read from any 3 of the included "Online Sources" of this free "Online Book")

- The Legacy of The Punjab by R. M. Chopra, 1997, Punjabee Bradree, Calcutta.

- http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/2891/11/11_chapter%204.pdf

External links