Joe Biden

Joe Biden | |

|---|---|

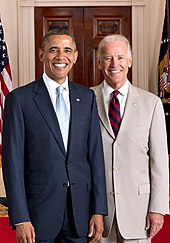

Official portrait, 2013 | |

| President-elect of the United States | |

| Assuming office January 20, 2021 | |

| Vice President | Kamala Harris (elect) |

| Succeeding | Donald Trump |

| 47th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 2009 – January 20, 2017 | |

| President | Barack Obama |

| Preceded by | Dick Cheney |

| Succeeded by | Mike Pence |

| United States Senator from Delaware | |

| In office January 3, 1973 – January 15, 2009 | |

| Preceded by | J. Caleb Boggs |

| Succeeded by | Ted Kaufman |

| Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee | |

| In office January 3, 2007 – January 3, 2009 | |

| Preceded by | Richard Lugar |

| Succeeded by | John Kerry |

| In office June 6, 2001 – January 3, 2003 | |

| Preceded by | Jesse Helms |

| Succeeded by | Richard Lugar |

| In office January 3, 2001 – January 20, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Jesse Helms |

| Succeeded by | Jesse Helms |

| Chair of the International Narcotics Control Caucus | |

| In office January 3, 2007 – January 3, 2009 | |

| Preceded by | Chuck Grassley |

| Succeeded by | Dianne Feinstein |

| Chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1987 – January 3, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Strom Thurmond |

| Succeeded by | Orrin Hatch |

| Member of the New Castle County Council from the 4th district | |

| In office November 4, 1970 – November 8, 1972 | |

| Preceded by | Henry Folsom |

| Succeeded by | Francis Swift |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. November 20, 1942 Scranton, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Family of Joe Biden |

| Education | |

| Occupation |

|

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom with distinction (2017) |

| Signature |  |

| Website | |

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. (/ˈbaɪdən/ BY-dən; born November 20, 1942) is an American politician and the president-elect of the United States. He defeated incumbent president Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election and will be inaugurated as the 46th president on January 20, 2021. A member of the Democratic Party, Biden served as the 47th vice president during the Obama administration from 2009 to 2017. He represented Delaware in the United States Senate from 1973 to 2009.

Raised in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and New Castle County, Delaware, Biden studied at the University of Delaware before earning his law degree from Syracuse University in 1968. He was elected a New Castle County Councillor in 1970 and became the sixth-youngest senator in American history when he was elected to the U.S. Senate from Delaware in 1972, at the age of 29. Biden was a longtime member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and eventually its chairman. He opposed the Gulf War in 1991 and supported expanding the NATO alliance into Eastern Europe and its intervention in the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s. He supported the resolution authorizing the Iraq War in 2002, and later opposed the surge of U.S. troops in 2007. He also chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee from 1987 to 1995, dealing with drug policy, crime prevention, and civil liberties issues; led the effort to pass the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act and the Violence Against Women Act; and oversaw six U.S. Supreme Court confirmation hearings, including the contentious hearings for Robert Bork and Clarence Thomas. He ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1988 and again in 2008.

Biden was reelected to the Senate six times, and was the fourth-most senior senator when he resigned to serve as Barack Obama's vice president after they won the 2008 presidential election; Obama and Biden were reelected in 2012. As vice president, Biden oversaw infrastructure spending in 2009 to counteract the Great Recession. His negotiations with congressional Republicans helped pass legislation including the 2010 Tax Relief Act, which resolved a taxation deadlock; the Budget Control Act of 2011, which resolved a debt ceiling crisis; and the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, which addressed the impending "fiscal cliff". He also led efforts to pass the United States–Russia New START treaty and helped formulate U.S. policy toward Iraq through the withdrawal of U.S. troops in 2011. Following the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, he led the Gun Violence Task Force. In January 2017, Obama awarded Biden the Presidential Medal of Freedom with distinction.

In April 2019, Biden announced his candidacy in the 2020 presidential election, and he reached the delegate threshold needed to secure the Democratic nomination in June 2020.[1] On August 11, he announced his choice of U.S. Senator Kamala Harris of California as his running mate. Biden defeated Trump in the November 3 election.[2][3]

Early life (1942–1965)

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal U.S. Senator from Delaware 47th Vice President of the United States Vice presidential campaigns 46th President of the United States Incumbent Tenure  |

||

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. was born November 20, 1942, at St. Mary's Hospital in Scranton, Pennsylvania,[4]: 5 to Catherine Eugenia "Jean" Biden (née Finnegan) and Joseph Robinette Biden Sr.[5][6] The oldest child in a Catholic family, he has a sister, Valerie, and two brothers, Francis and James.[4]: 9 Jean was of Irish descent,[7][8][4]: 8 while Joseph Sr. had English, French, and Irish ancestry.[9][4]: 8

Biden's father was initially wealthy but had suffered several financial setbacks by the time Biden was born. After transferring his family to Boston in 1944, Biden Sr. tried to set up a furniture store with a family friend, only to have his friend run off with their start-up money. Next, he attempted a crop-dusting enterprise on Garden City, Long Island, which also went bust.[10][11][12] In 1947, he relocated his family back to Scranton and for several years they lived with Biden's maternal grandparents.[13]

Scranton fell into economic decline during the 1950s and Biden's father could not find steady work.[14] Beginning in 1953, the family lived for several years in an apartment in Claymont, Delaware, then moved to a house in Wilmington, Delaware.[13] Biden Sr. later became a successful used car salesman, maintaining the family in a middle-class lifestyle.[13][14][15]

At Archmere Academy in Claymont,[4]: 27, 32 Biden was a standout halfback and wide receiver on the high school football team;[13][16] he also played baseball.[13] Though a poor student, he was class president in his junior and senior years.[4]: 40–41 [17]: 99 He graduated in 1961.[4]: 40–41

At the University of Delaware in Newark, Biden briefly played freshman football[18][19] and earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1965 with a double major in history and political science, and a minor in English.[20][17]: 98 He had a C average and ranked 506th in his class of 688.[21][22]

Biden has a stutter, which has improved since his early twenties.[23] He says he has reduced it by reciting poetry before a mirror,[17]: 99 [24] but it has been suggested that it affected his performance in the 2020 Democratic Party presidential debates.[25]

First marriage, law school, and early career (1966–1972)

On August 27, 1966, Biden married Neilia Hunter (1942–1972), a student at Syracuse University,[20] after overcoming her parents' reluctance for her to wed a Roman Catholic; the ceremony was held in a Catholic church in Skaneateles, New York.[26] They had three children: Joseph R. "Beau" Biden III (1969–2015), Robert Hunter Biden (born 1970), and Naomi Christina "Amy" Biden (1971–1972).[20]

In 1968, Biden earned a Juris Doctor from Syracuse University College of Law, ranked 76th in his class of 85,[21][22] and was admitted to the Delaware bar in 1969.[27] While in school, he received student draft deferments,[28] and afterward was classified as unavailable for military service due to asthma.[28][29]

In 1968, Biden clerked at a Wilmington law firm headed by prominent local Republican William Prickett and, he later said, "thought of myself as a Republican".[30][31] He disliked incumbent Democratic Delaware governor Charles L. Terry's conservative racial politics and supported a more liberal Republican, Russell W. Peterson, who defeated Terry in 1968.[30] Biden was recruited by local Republicans but registered as an Independent because of his distaste for Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon.[30]

In 1969, Biden practiced law first as a public defender and then at a firm headed by a locally active Democrat[32][30] who named him to the Democratic Forum, a group trying to reform and revitalize the state party;[4]: 86 Biden subsequently reregistered as a Democrat.[30] He and another attorney also formed a law firm.[32] Corporate law, however, did not appeal to him, and criminal law did not pay well.[13] He supplemented his income by managing properties.[33]

Later that year Biden was elected to a county council seat in a usually Republican district of New Castle County, Delaware, running on a liberal platform that included support for public housing in the suburbs.[32][34][4]: 59 He served on the council, while still practicing law, until 1972.[27][35] He opposed large highway projects that might disrupt Wilmington neighborhoods.[4]: 62

1972 U.S. Senate campaign in Delaware

In 1972, Biden defeated Republican incumbent J. Caleb Boggs to become the junior U.S. senator from Delaware. He was the only Democrat willing to challenge Boggs.[32] His campaign had almost no money, and he was given no chance of winning.[13] Family members managed and staffed the campaign, which relied on meeting voters face-to-face and hand-distributing position papers,[36] an approach made feasible by Delaware's small size.[33] He received some help from the AFL–CIO and Democratic pollster Patrick Caddell.[32] His platform focused on withdrawal from Vietnam, the environment, civil rights, mass transit, more equitable taxation, health care, and public dissatisfaction with "politics as usual".[32][36] A few months before the election Biden trailed Boggs by almost thirty percentage points,[32] but his energy, attractive young family, and ability to connect with voters' emotions worked to his advantage,[15] and he won with 50.5 percent of the vote.[36]

Death of wife and daughter

On December 18, 1972, a few weeks after the election, Biden's wife and one-year-old daughter Naomi were killed in an automobile accident while Christmas shopping in Hockessin, Delaware.[20] Neilia's station wagon was hit by a tractor-trailer truck as she pulled out from an intersection. Their sons Beau and Hunter survived the accident and were taken to the hospital in fair condition, Beau with a broken leg and other wounds, and Hunter with a minor skull fracture and other head injuries.[4]: 93, 98 Doctors soon said both would make full recoveries.[4]: 96 Biden considered resigning to care for them,[15] but Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield persuaded him not to.[37]

Years later, Biden said he had heard that the truck driver allegedly drank alcohol before the collision. The driver's family denied that claim, and the police never substantiated it. Biden later apologized to the family.[38][39][40][41][42]

United States Senate (1973–2009)

Second marriage

Biden was sworn in on January 5, 1973, by secretary of the Senate Francis R. Valeo at the Delaware Division of the Wilmington Medical Center.[43][4]: 93, 98 Present were his sons Beau (whose leg was still in traction from the automobile accident) and Hunter and other family members.[43][4]: 93, 98 At 30, he was the sixth-youngest senator in U.S. history.[44][45]

To see his sons every day,[46] Biden commuted by train between his Delaware home and Washington, D.C.—90 minutes each way—and maintained this habit throughout his 36 years in the Senate.[15] But the accident had filled him with anger and religious doubt. He wrote later that he "felt God had played a horrible trick" on him,[47] and he had trouble focusing on work.[48][49]

In 1975, Biden met Jill Tracy Jacobs, who had grown up in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania, and would become a teacher in Delaware.[50] They met on a blind date arranged by Biden's brother, although Biden had already noticed a photograph of her in an advertisement for a park in Wilmington.[50] Biden credits her with renewing his interest in both politics and life.[51] On June 17, 1977, Biden and Jacobs were married by a Catholic priest at the Chapel at the United Nations in New York.[52][53] Jill Biden has a bachelor's degree from the University of Delaware; two master's degrees, one from West Chester University and the other from Villanova University; and a doctorate in education from the University of Delaware.[50] They have one daughter together, Ashley Blazer (born 1981),[20] who became a social worker and staffer at the Delaware Department of Services for Children, Youth, and Their Families.[54] Biden and his wife are Roman Catholics and regularly attend Mass at St. Joseph's on the Brandywine in Greenville, Delaware.[55] From 1991 to 2008, Biden co-taught a seminar on constitutional law at Widener University School of Law.[56] The seminar often had a waiting list. Biden sometimes flew back from overseas to teach the class.[57][58][59][60]

Early Senate activities

During his early years in the Senate, Biden focused on consumer protection and environmental issues and called for greater government accountability.[61] In a 1974 interview, he described himself as liberal on civil rights and liberties, senior citizens' concerns and healthcare but conservative on other issues, including abortion and the military conscription.[62]

In his first decade in the Senate, Biden focused on arms control.[63][64] After Congress failed to ratify the SALT II Treaty signed in 1979 by Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev and President Jimmy Carter, Biden met with Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko to communicate American concerns, and secured changes that addressed the Senate Foreign Relations Committee's objections.[65] When the Reagan administration wanted to interpret the 1972 SALT I treaty loosely to allow development of the Strategic Defense Initiative, Biden argued for strict adherence to the treaty.[63] He received considerable attention when he excoriated Secretary of State George Shultz at a Senate hearing for the Reagan administration's support of South Africa despite its continued policy of apartheid.[30]

Biden became ranking minority member of the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1981. In 1984, he was a Democratic floor manager for the successful passage of the Comprehensive Crime Control Act; over time, the law's tough-on-crime provisions became controversial and in 2019, Biden called his role in passing the bill a "big mistake".[66][67] His supporters praised him for modifying some of the law's worst provisions, and it was his most important legislative accomplishment to that time.[68] This bill included the Federal Assault Weapons Ban[69][70] and the Violence Against Women Act,[71] which he has called his most significant legislation.[72]

In 1993, Biden voted for a provision that deemed homosexuality incompatible with military life, thereby banning gays from serving in the armed forces.[73][74][75] In 1996, he voted for the Defense of Marriage Act, which prohibited the federal government from recognizing same-sex marriages, thereby barring individuals in such marriages from equal protection under federal law and allowing states to do the same;[76] in 2015, the act was ruled unconstitutional in Obergefell v. Hodges.[77]

Opposition to busing

In the mid-1970s, Biden was one of the Senate's leading opponents of race-integration busing. His Delaware constituents strongly opposed it, and such opposition nationwide later led his party to mostly abandon school integration policies.[78] In his first Senate campaign, Biden had expressed support for busing to remedy de jure segregation, as in the South, but opposed its use to remedy de facto segregation arising from racial patterns of neighborhood residency, as in Delaware; he opposed a proposed constitutional amendment banning busing entirely.[79]

In May 1974, Biden voted to table a proposal containing anti-busing and anti-desegregation clauses but later voted for a modified version containing a qualification that it was not intended to weaken the judiciary's power to enforce the 5th Amendment and 14th Amendment.[80] In 1975, he supported a proposal that would have prevented the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare from cutting federal funds to districts that refused to integrate;[81] he said busing was a "bankrupt idea [violating] the cardinal rule of common sense" and that his opposition would make it easier for other liberals to follow suit.[68] At the same time he supported initiatives on housing, job opportunities and voting rights.[80] Biden supported a measure[when?] forbidding the use of federal funds for transporting students beyond the school closest to them. In 1977, he co-sponsored an amendment closing loopholes in that measure, which President Carter signed into law in 1978.[82]

1988 presidential campaign

Biden formally declared his candidacy for the 1988 Democratic presidential nomination on June 9, 1987.[83] He was considered a strong candidate because of his moderate image, his speaking ability, his high profile as chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee at the upcoming Robert Bork Supreme Court nomination hearings, and his appeal to Baby Boomers; he would have been the second-youngest person elected president, after John F. Kennedy.[30][84][17]: 83 He raised more in the first quarter of 1987 than any other candidate.[84][17]: 83

By August his campaign's messaging had become confused due to staff rivalries,[17]: 108–109 and in September, he was accused of plagiarizing a speech by British Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock.[85] Biden's speech had similar lines about being the first person in his family to go to university. Biden had credited Kinnock with the formulation on previous occasions,[86][87] but did not on two occasions in late August.[88]: 230–232 [87] Earlier that year he had also used passages from a 1967 speech by Robert F. Kennedy (for which his aides took blame) and a short phrase from John F. Kennedy's inaugural address; two years earlier he had used a 1976 passage by Hubert Humphrey.[89] Biden responded that politicians often borrow from one another without giving credit, and that one of his rivals for the nomination, Jesse Jackson, had called him to point out that he (Jackson) had used the same material by Humphrey that Biden had used.[15][90]

A few days later an incident in law school in which he drew text from a Fordham Law Review article with inadequate citations was publicized.[90] Biden was required to repeat the course and passed with high marks.[91] At Biden's request the Delaware Supreme Court's Board of Professional Responsibility reviewed the incident and concluded that he had violated no rules.[92]

He also made several false or exaggerated claims about his early life: that he had earned three degrees in college, that he had attended law school on a full scholarship, that he had graduated in the top half of his class,[93][94] and that he had marched in the civil rights movement.[95] The limited amount of other news about the race amplified these revelations[96] and on September 23, 1987, Biden withdrew from the race, saying his candidacy had been overrun by "the exaggerated shadow" of his past mistakes.[97]

Brain surgeries

In February 1988, after several episodes of increasingly severe neck pain, Biden was taken by ambulance to Walter Reed Army Medical Center for surgery to correct a leaking intracranial berry aneurysm.[98][99] While recuperating he suffered a pulmonary embolism, a serious complication.[99]

After a second aneurysm was surgically repaired in May,[99][100] Biden's recuperation kept him away from the Senate for seven months.[101]

Senate Judiciary Committee

Biden was a longtime member of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary. He chaired it from 1987 to 1995 and was ranking minority member from 1981 to 1987 and from 1995 to 1997.

As chairman, Biden presided over two highly contentious U.S. Supreme Court confirmation hearings.[15] When Robert Bork was nominated in 1988, Biden reversed his approval—given in an interview the previous year—of a hypothetical Bork nomination. Conservatives were angered,[102] but at the hearings' close Biden was praised for his fairness, humor and courage.[102][103] Rejecting some Bork opponents' less intellectually honest arguments,[15] Biden framed his objections to Bork in terms of the conflict between Bork's strong originalism and the view that the U.S. Constitution provides rights to liberty and privacy beyond those explicitly enumerated in its text.[103] Bork's nomination was rejected in the committee by a 9–5 vote[103] and then in the full Senate, 58–42.[104]

During Clarence Thomas's nomination hearings in 1991, Biden's questions on constitutional issues were often convoluted to the point that Thomas sometimes lost track of them,[105] and Thomas later wrote that Biden's questions had been akin to "beanballs".[106] After the committee hearing closed, the public learned that Anita Hill, a University of Oklahoma law school professor, had accused Thomas of making unwelcome sexual comments when they had worked together.[107][108] Biden had known of some of these charges, but had initially shared them only with the committee because at the time Hill had been unwilling to testify.[15] The committee hearing was reopened and Hill testified, but Biden did not permit testimony from other witnesses, such as a woman who had made similar charges and experts on harassment;[109] Biden said he wanted to preserve Thomas's privacy and the hearings' decency.[105][109] The full Senate confirmed Thomas by a 52–48 vote, with Biden opposed.[15] Liberal legal advocates and women's groups felt strongly that Biden had mishandled the hearings and not done enough to support Hill.[109] Biden later sought out women to serve on the Judiciary Committee and emphasized women's issues in the committee's legislative agenda.[15] In 2019, he told Hill he regretted his treatment of her, but Hill said afterward she remained unsatisfied.[110]

Biden was critical of Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr during the 1990s Whitewater controversy and Lewinsky scandal investigations, saying "it's going to be a cold day in hell" before another independent counsel would be granted similar powers.[111] He voted to acquit during the impeachment of President Clinton.[112] During the 2000s, Biden sponsored bankruptcy legislation sought by credit card issuers.[15] President Bill Clinton vetoed the bill in 2000, but it passed in 2005 as the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act,[15] with Biden one of only 18 Democrats to vote for it, while leading Democrats and consumer rights organizations opposed it.[113] As a senator, Biden strongly supported increased Amtrak funding and rail security.[114][115]

Senate Foreign Relations Committee

Biden was also a longtime member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He became its ranking minority member in 1997, and chaired it from June 2001 to 2003 and 2007 to 2009.[116] His positions were generally liberal internationalist.[63][117] He collaborated effectively with Republicans and sometimes went against elements of his own party.[116][117] During this time he met with at least 150 leaders from 60 countries and international organizations, becoming a well-known Democratic voice on foreign policy.[118]

Biden voted against authorization for the Gulf War in 1991,[117] siding with 45 of the 55 Democratic senators; he said the U.S. was bearing almost all the burden in the anti-Iraq coalition.[119]

Biden became interested in the Yugoslav Wars after hearing about Serbian abuses during the Croatian War of Independence in 1991.[63] Once the Bosnian War broke out, Biden was among the first to call for the "lift and strike" policy of lifting the arms embargo, training Bosnian Muslims and supporting them with NATO air strikes, and investigating war crimes.[63][116] The George H. W. Bush administration and Clinton administration were both reluctant to implement the policy, fearing Balkan entanglement.[63][117] In April 1993, Biden spent a week in the Balkans and held a tense three-hour meeting with Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević.[120] Biden related that he had told Milošević, "I think you're a damn war criminal and you should be tried as one."[120]

Biden wrote an amendment in 1992 to compel the Bush administration to arm the Bosnians, but deferred in 1994 to a somewhat softer stance the Clinton administration preferred, before signing on the following year to a stronger measure sponsored by Bob Dole and Joe Lieberman.[120] The engagement led to a successful NATO peacekeeping effort.[63] Biden has called his role in affecting Balkans policy in the mid-1990s his "proudest moment in public life" related to foreign policy.[117]

In 1999, during the Kosovo War, Biden supported the 1999 NATO bombing of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[63] He co-sponsored with John McCain the McCain-Biden Kosovo Resolution, which called on President Clinton to use all necessary force, including ground troops, to confront Milošević over Yugoslav actions toward ethnic Albanians in Kosovo.[117][121]

Biden was a strong supporter of the 2001 war in Afghanistan, saying, "Whatever it takes, we should do it."[122] As head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Biden said in 2002 that Saddam Hussein was a threat to national security and there was no option but to "eliminate" that threat.[123]

In October 2002, he voted in favor of the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq, approving the U.S. invasion of Iraq.[117] As chair of the committee, he assembled a series of witnesses to testify in favor of the authorization. They gave testimony grossly misrepresenting the intent, history and status of Saddam and his secular government, which was an avowed enemy of al-Qaida, and touting Iraq's fictional possession of weapons of mass destruction.[124]

Biden eventually became a critic of the war and viewed his vote and role as a "mistake", but did not push for U.S. withdrawal.[117][120] He supported the appropriations to pay for the occupation, but argued repeatedly that the war should be internationalized, that more soldiers were needed, and that the Bush administration should "level with the American people" about the cost and length of the conflict.[116][121]

By late 2006, Biden's stance had shifted considerably, and he opposed the troop surge of 2007,[117][120] saying General David Petraeus was "dead, flat wrong" in believing the surge could work.[125] Biden instead advocated dividing Iraq into a loose federation of three ethnic states.[126] In November 2006, Biden and Leslie H. Gelb, president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations, released a comprehensive strategy to end sectarian violence in Iraq.[127] Rather than continuing the present approach or withdrawing, the plan called for "a third way": federalizing Iraq and giving Kurds, Shiites, and Sunnis "breathing room" in their own regions.[4]: 572–573 In September 2007, a non-binding resolution endorsing such a scheme passed the Senate,[127] but the idea was unfamiliar, had no political constituency, and failed to gain traction.[125] Iraq's political leadership denounced the resolution as de facto partitioning of the country, and the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad issued a statement distancing itself from it.[127] In May 2008, he sharply criticized President George W. Bush for a speech to Israel's Knesset in which he compared some Democrats to Western leaders who appeased Hitler before World War II; Biden called the speech "bullshit", "malarkey", and "outrageous". He later apologized for his language.[128]

Reputation

Elected to the Senate in 1972, Biden was reelected in 1978, 1984, 1990, 1996, 2002, and 2008, usually getting about 60% of the vote.[114] He was junior senator to William Roth, who was first elected in 1970, until Roth was defeated in 2000.[129] As of 2020[update] he was the 18th-longest-serving senator in U.S. history.[130]

Biden was consistently ranked one of the least wealthy members of the Senate,[131][132][133] which he attributed to his having been elected young.[134] Feeling that less-wealthy public officials may be tempted to accept contributions in exchange for political favors, he proposed campaign finance reform measures during his first term.[68]

The political writer Howard Fineman has written, "Biden is not an academic, he's not a theoretical thinker, he's a great street pol. He comes from a long line of working people in Scranton—auto salesmen, car dealers, people who know how to make a sale. He has that great Irish gift."[33] Political columnist David S. Broder wrote that Biden has grown over time: "He responds to real people—that's been consistent throughout. And his ability to understand himself and deal with other politicians has gotten much much better."[33] James Traub has written, "Biden is the kind of fundamentally happy person who can be as generous toward others as he is to himself."[125] In 2006, Delaware newspaper columnist Harry F. Themal wrote that Biden "occupies the sensible center of the Democratic Party".[135]

Biden has a reputation for loquacity;[136] he is a strong speaker and debater and an effective guest on Sunday morning talk shows.[137] He often deviates from prepared remarks[138] and sometimes "puts his foot in his mouth".[139][140][141][137] The New York Times wrote that Biden's "weak filters make him capable of blurting out pretty much anything".[140]

2008 presidential campaign

Biden chose not to run for president in 1992 in part because he had voted against authorizing the Gulf War,[114] and did not run in 2004 because, he said, he felt he had little chance of winning and could best serve the country by remaining in the Senate.[142] In January 2007, he declared his candidacy in the 2008 election.[143]

During his campaign, Biden focused on the Iraq War, his record as chairman of major Senate committees, and his foreign-policy experience. Biden rejected speculation that he might become Secretary of State,[144] focusing on only the presidency.[145] In mid-2007, Biden stressed his foreign policy expertise compared to Obama's, saying of the latter, "I think he can be ready, but right now I don't believe he is. The presidency is not something that lends itself to on-the-job training."[146] Biden also said Obama was copying some of his foreign policy ideas.[125] Biden was noted for his one-liners during the campaign; in one debate he said of Republican candidate Rudy Giuliani: "There's only three things he mentions in a sentence: a noun, and a verb and 9/11."[147] Overall, Biden's debate performances were an effective mixture of humor and sharp and surprisingly disciplined comments.[148]: 336

Biden had difficulty raising funds, struggled to draw people to his rallies, and failed to gain traction against the high-profile candidacies of Obama and Senator Hillary Clinton.[149] He never rose above single digits in national polls of the Democratic candidates. In the first contest on January 3, 2008, Biden placed fifth in the Iowa caucuses, garnering slightly less than one percent of the state delegates.[150] He withdrew from the race that evening.[151]

Despite its lack of success, Biden's 2008 campaign raised his stature in the political world.[148]: 336 In particular, it changed the relationship between Biden and Obama. Although they had served together on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, they had not been close: Biden resented Obama's quick rise to political stardom,[125][152] while Obama viewed Biden as garrulous and patronizing.[148]: 28, 337–338 Having gotten to know each other during 2007, Obama appreciated Biden's campaigning style and appeal to working-class voters, and Biden said he became convinced Obama was "the real deal".[152][148]: 28, 337–338

2008 vice-presidential campaign

Shortly after Biden withdrew from the presidential race, Obama privately told him he was interested in finding an important place for Biden in his administration.[153] Biden declined Obama's first request to vet him for the vice-presidential slot, fearing the vice presidency would represent a loss in status and voice from his Senate position, but he later changed his mind.[125][154] In a June 22, 2008 interview, Biden said that while he was not actively seeking the vice-presidential nomination, he would accept it if offered.[155] In early August, Obama and Biden met in secret to discuss the possibility,[153] and developed a strong personal rapport.[152] On August 22, 2008, Obama announced that Biden would be his running mate.[156] The New York Times reported that the strategy behind the choice reflected a desire to fill out the ticket with someone with foreign policy and national security experience—and not to help the ticket win a swing state or to emphasize Obama's "change" message.[157] Others pointed out Biden's appeal to middle-class and blue-collar voters, as well as his willingness to aggressively challenge Republican nominee John McCain in a way that Obama seemed uncomfortable doing at times.[158][159] In accepting Obama's offer, Biden ruled out running for president again in 2016,[153] but his comments in later years seemed to back off that stance, as he did not want to diminish his political power by appearing uninterested in advancement.[160][161][162] Biden was officially nominated for vice president on August 27 by voice vote at the 2008 Democratic National Convention in Denver.[163]

Biden's vice-presidential campaigning gained little media visibility, as far greater press attention was focused on the Republican running mate, Alaska Governor Sarah Palin.[140][164] During one week in September 2008, for instance, the Pew Research Center's Project for Excellence in Journalism found that Biden was included in only five percent of coverage of the race, far less than the other three candidates on the tickets received.[165] Biden nevertheless focused on campaigning in economically challenged areas of swing states and trying to win over blue-collar Democrats, especially those who had supported Hillary Clinton.[125][140] Biden attacked McCain heavily despite a long-standing personal friendship.[nb 1] He said, "That guy I used to know, he's gone. It literally saddens me."[140] As the financial crisis of 2007–2010 reached a peak with the liquidity crisis of September 2008 and the proposed bailout of the United States financial system became a major factor in the campaign, Biden voted in favor of the $700 billion Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, which went on to pass in the Senate 74–25.[167]

On October 2, 2008, Biden participated in the vice-presidential debate with Palin at Washington University in St. Louis. Post-debate polls found that while Palin exceeded many voters' expectations, Biden had won the debate overall.[4]: 655–661 During the campaign's final days, he focused on less populated, older, less well-off areas of battleground states, especially Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, where polling indicated he was popular and where Obama had not campaigned or performed well in the Democratic primaries.[168][169][170] He also campaigned in some normally Republican states, as well as in areas with large Catholic populations.[170]

Under instructions from the campaign, Biden kept his speeches succinct and tried to avoid offhand remarks, such as one about Obama's being tested by a foreign power soon after taking office, which had attracted negative attention.[168][169] Privately, Biden's remarks frustrated Obama. "How many times is Biden gonna say something stupid?" he asked.[148]: 411–414, 419 Obama campaign staffers referred to Biden blunders as "Joe bombs" and kept Biden uninformed about strategy discussions, which in turn irked Biden.[162] Relations between the two campaigns became strained for a month, until Biden apologized on a call to Obama and the two built a stronger partnership.[148]: 411–414 Publicly, Obama strategist David Axelrod said Biden's high popularity ratings had outweighed any unexpected comments.[171] Nationally, Biden had a 60% favorability rating in a Pew Research Center poll, compared to Palin's 44%.[168]

On November 4, 2008, Obama and Biden were elected with 53% of the popular vote and 365 electoral votes to McCain–Palin's 173.[172][173][174]

Biden ran for reelection to his Senate seat as well as for vice president,[175] as permitted by Delaware law.[114] On November 4, he was also reelected to the Senate, defeating Republican Christine O'Donnell.[176] Having won both races, Biden made a point of holding off his resignation from the Senate so he could be sworn in for his seventh term on January 6, 2009.[177] He became the youngest senator ever to start a seventh full term, and said, "In all my life, the greatest honor bestowed upon me has been serving the people of Delaware as their United States senator."[177] Biden cast his last Senate vote on January 15, supporting the release of the second $350 billion for the Troubled Asset Relief Program,[178] and resigned from the Senate later that day.[nb 2] In an emotional farewell, Biden told the Senate: "Every good thing I have seen happen here, every bold step taken in the 36-plus years I have been here, came not from the application of pressure by interest groups, but through the maturation of personal relationships."[182] Delaware Governor Ruth Ann Minner appointed longtime Biden adviser Ted Kaufman to fill Biden's vacated Senate seat.[183]

Vice president (2009–2017)

Biden said he intended to eliminate some of the explicit roles assumed by George W. Bush's vice president, Dick Cheney, and did not intend to emulate any previous vice presidency.[184] He chaired Obama's transition team[185] and headed an initiative to improve middle-class economic well-being.[186] In early January 2009, in his last act as chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, he visited the leaders of Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan,[187] and on January 20 he was sworn in as the 47th vice president of the United States[188]—the first vice president from Delaware[189] and the first Roman Catholic vice president.[190][191]

Obama was soon comparing Biden to a basketball player "who does a bunch of things that don't show up in the stat sheet".[192] In May, Biden visited Kosovo and affirmed the U.S. position that its "independence is irreversible".[193] Biden lost an internal debate to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton about sending 21,000 new troops to Afghanistan,[194][195] but his skepticism was valued,[154] and in 2009, Biden's views gained more influence as Obama reconsidered his Afghanistan strategy.[196] Biden visited Iraq about every two months,[125] becoming the administration's point man in delivering messages to Iraqi leadership about expected progress there.[154] More generally, overseeing Iraq policy became Biden's responsibility: Obama was said to have said, "Joe, you do Iraq."[197] Biden said Iraq "could be one of the great achievements of this administration".[198] His January 2010 visit to Iraq in the midst of turmoil over banned candidates from the upcoming Iraqi parliamentary election resulted in 59 of the several hundred candidates being reinstated by the Iraqi government two days later.[199] By 2012, Biden had made eight trips there, but his oversight of U.S. policy in Iraq receded with the exit of U.S. troops in 2011.[200][201]

Biden was also in charge of overseeing infrastructure spending from the Obama stimulus package intended to help counteract the ongoing recession, and stressed that only worthy projects should get funding.[202] He talked with hundreds of governors, mayors, and other local officials in this role.[200] During this period, Biden was satisfied that no major instances of waste or corruption had occurred,[154] and when he completed that role in February 2011, he said the number of fraud incidents with stimulus monies had been less than one percent.[203]

In late April 2009, Biden's off-message response to a question during the beginning of the swine flu outbreak, that he would advise family members against traveling on airplanes or subways, led to a swift retraction by the White House.[204] The remark revived Biden's reputation for gaffes.[205][196][206] Confronted with rising unemployment through July 2009, Biden acknowledged that the administration had "misread how bad the economy was" but maintained confidence the stimulus package would create many more jobs once the pace of expenditures picked up.[207] On March 23, 2010, a microphone picked up Biden telling the president that his signing the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was "a big fucking deal" during live national news telecasts. White House press secretary Robert Gibbs replied on Twitter, "And yes Mr. Vice President, you're right ..."[208] Despite their different personalities, Obama and Biden formed a friendship, partly based around Obama's daughter Sasha and Biden's granddaughter Maisy, who attended Sidwell Friends School together.[162]

Members of the Obama administration said Biden's role in the White House was to be a contrarian and force others to defend their positions.[209] Rahm Emanuel, White House chief of staff, said that Biden helped counter groupthink.[192] White House press secretary Jay Carney, Biden's former communications director, said Biden played the role of "the bad guy in the Situation Room".[209] Another senior Obama advisor said Biden "is always prepared to be the skunk at the family picnic to make sure we are as intellectually honest as possible."[154] Obama said, "The best thing about Joe is that when we get everybody together, he really forces people to think and defend their positions, to look at things from every angle, and that is very valuable for me."[154] On June 11, 2010, Biden represented the United States at the opening ceremony of the World Cup, attended the England v. U.S. game, and visited Egypt, Kenya, and South Africa.[210] The Bidens maintained a relaxed atmosphere at their official residence in Washington, often entertaining their grandchildren, and regularly returned to their home in Delaware.[211]

Biden campaigned heavily for Democrats in the 2010 midterm elections, maintaining an attitude of optimism in the face of predictions of large-scale losses for the party.[212] Following big Republican gains in the elections and the departure of White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel, Biden's past relationships with Republicans in Congress became more important.[213][214] He led the successful administration effort to gain Senate approval for the New START treaty.[213][214] In December 2010, Biden's advocacy for a middle ground, followed by his negotiations with Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell, were instrumental in producing the administration's compromise tax package that included a temporary extension of the Bush tax cuts.[214][215] Biden then took the lead in trying to sell the agreement to a reluctant Democratic caucus in Congress.[214][216] The package passed as the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010.

In foreign policy, Biden supported the NATO-led military intervention in Libya in 2011.[217] He supported closer economic ties with Russia.[218]

In March 2011, Obama delegated Biden to lead negotiations between Congress and the White House in resolving federal spending levels for the rest of the year and avoiding a government shutdown.[219] By May 2011, a "Biden panel" with six congressional members was trying to reach a bipartisan deal on raising the U.S. debt ceiling as part of an overall deficit reduction plan.[220][221] The U.S. debt ceiling crisis developed over the next few months, but Biden's relationship with McConnell again proved key in breaking a deadlock and bringing about a deal to resolve it, in the form of the Budget Control Act of 2011, signed on August 2, 2011, the same day an unprecedented U.S. default had loomed.[222][223][224] Biden had spent the most time bargaining with Congress on the debt question of anyone in the administration,[223] and one Republican staffer said, "Biden's the only guy with real negotiating authority, and [McConnell] knows that his word is good. He was a key to the deal."[222]

Some reports suggest that Biden opposed to going forward with the May 2011 U.S. mission to kill Osama bin Laden,[200][225] lest failure adversely affect Obama's reelection prospects.[226][227] He took the lead in notifying Congressional leaders of the successful outcome.[228]

Reelection

In October 2010, Biden said Obama had asked him to remain as his running mate for the 2012 presidential election,[212] but with Obama's popularity on the decline, White House chief of staff William M. Daley conducted some secret polling and focus group research in late 2011 on the idea of replacing Biden on the ticket with Hillary Clinton.[229] The notion was dropped when the results showed no appreciable improvement for Obama,[229] and White House officials later said Obama had never entertained the idea.[230]

Biden's May 2012 statement that he was "absolutely comfortable" with same-sex marriage gained considerable public attention in comparison to Obama's position, which had been described as "evolving".[231] Biden made his statement without administration consent, and Obama and his aides were quite irked, since Obama had planned to shift position several months later, in the build-up to the party convention, and since Biden had previously counseled the president to avoid the issue lest key Catholic voters be offended.[162][232][233][234] Gay rights advocates seized upon Biden's statement,[232] and within days, Obama announced that he too supported same-sex marriage, an action in part forced by Biden's unexpected remarks.[235] Biden apologized to Obama in private for having spoken out,[233][236] while Obama acknowledged publicly it had been done from the heart.[232] The incident showed that Biden still struggled at times with message discipline,[162] as Time wrote, "Everyone knows Biden's greatest strength is also his greatest weakness."[200] Relations were also strained between the campaigns when Biden appeared to use his position to bolster fundraising contacts for a possible run for president in 2016, and he ended up being excluded from Obama campaign strategy meetings.[229]

The Obama campaign nevertheless still valued Biden as a retail-level politician who could connect with disaffected, blue-collar workers and rural residents, and he had a heavy schedule of appearances in swing states as the Obama reelection campaign began in earnest in spring 2012.[237][200] An August 2012 remark before a mixed-race audience that Republican proposals to relax Wall Street regulations would "put y'all back in chains" led to a similar analysis of Biden's face-to-face campaigning abilities versus his tendency to go off track.[237][238][239] The Los Angeles Times wrote, "Most candidates give the same stump speech over and over, putting reporters if not the audience to sleep. But during any Biden speech, there might be a dozen moments to make press handlers cringe, and prompt reporters to turn to each other with amusement and confusion."[238] Time magazine wrote that Biden often went too far and "Along with the familiar Washington mix of neediness and overconfidence, Biden's brain is wired for more than the usual amount of goofiness."[237]

Biden was nominated for a second term as vice president at the 2012 Democratic National Convention in September.[240] Debating his Republican counterpart, Representative Paul Ryan, in the vice-presidential debate on October 11 he made a spirited and emotional defense of the Obama administration's record and energetically attacked the Republican ticket.[241][242] On November 6, Obama and Biden were reelected[243] with 332 of 538 Electoral College votes and 51% of the popular vote.[244]

In December 2012, Obama named Biden to head the Gun Violence Task Force, created to address the causes of gun violence in the United States in the aftermath of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting.[245] Later that month, during the final days before the United States fell off the "fiscal cliff", Biden's relationship with McConnell once more proved important as the two negotiated a deal that led to the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 being passed at the start of 2013.[246][247] It made many of the Bush tax cuts permanent but raised rates on upper income levels.[247]

Second term (2013–2017)

Biden was inaugurated to a second term on January 20, 2013, at a small ceremony at Number One Observatory Circle, his official residence, with Justice Sonia Sotomayor presiding (a public ceremony took place on January 21).[248] He continued to be in the forefront as, in the wake of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, the Obama administration put forth executive orders and proposed new gun control measures[70] (they failed to pass).[249] Biden played little part in discussions that led to the October 2013 passage of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2014, which resolved the federal government shutdown of 2013 and the debt-ceiling crisis of 2013. This was because Senate majority leader Harry Reid and other Democratic leaders cut him out of any direct talks with Congress, feeling Biden had given too much away during previous negotiations.[250][251][252]

Biden's Violence Against Women Act was reauthorized again in 2013. The act led to related developments, such as the White House Council on Women and Girls, begun in the first term, as well as the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault, begun in January 2014 with Biden and Valerie Jarrett as co-chairs.[253][254] Biden discussed federal guidelines on sexual assault on university campuses while giving a speech at the University of New Hampshire. He said, "No means no, if you're drunk or you're sober. No means no if you're in bed, in a dorm or on the street. No means no even if you said yes at first and you changed your mind. No means no."[255][256][257]

Biden favored arming Syria's rebel fighters.[258] As Iraq fell apart during 2014, renewed attention was paid to the Biden-Gelb Iraqi federalization plan of 2006, with some observers suggesting Biden had been right all along.[259][260] Biden himself said the U.S. would follow ISIL "to the gates of hell".[261] On December 8, 2015, Biden spoke in Ukraine's parliament in Kyiv[262][263] in one of his many visits to set U.S. aid and policy stance on Ukraine.[264][265] Biden had close relationships with several Latin American leaders and was assigned a focus on the region during the administration; he visited the region 16 times during his vice presidency, the most of any president or vice president.[266]

In 2015, Speaker of the House John Boehner and Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell invited Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu to address a joint session of Congress without notifying the Obama administration. This defiance of protocol led Biden and more than 50 congressional Democrats to skip Netanyahu's speech.[267] In August 2016, Biden visited Serbia, where he met with Serbian president Aleksandar Vučić and expressed his condolences for civilian victims of the bombing campaign during the Kosovo War.[268] In Kosovo, he attended a ceremony renaming a highway after his son Beau, in honor of Beau's service to Kosovo in training its judges and prosecutors.[269][270][271]

Biden never cast a tie-breaking vote in the Senate, making him the longest-serving vice president with this distinction.[272]

Role in the 2016 presidential campaign

During his second term, Biden was often said to be preparing for a possible bid for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination.[273] At age 74 on Inauguration Day in January 2017, he would have been the oldest president on inauguration in history.[274] With his family, many friends, and donors encouraging him in mid-2015 to enter the race, and with Hillary Clinton's favorability ratings in decline at that time, Biden was reported to again be seriously considering the prospect and a "Draft Biden 2016" PAC was established.[273][275][276]

As of September 11, 2015[update], Biden was still uncertain about running. He cited his son's recent death as a large drain on his emotional energy, and said, "nobody has a right ... to seek that office unless they're willing to give it 110% of who they are."[277] On October 21, speaking from a podium in the Rose Garden with his wife and Obama by his side, Biden announced his decision not to run for president in 2016.[278][279][280] In January 2016, Biden affirmed that it was the right decision, but admitted to regretting not running for president "every day".[281]

After Obama endorsed Hillary Clinton on June 9, 2016, Biden endorsed her later that day.[282] Though Biden and Clinton were scheduled to campaign together in Scranton on July 8, Clinton canceled the appearance in light of the shooting of Dallas police officers the previous day.[283] Throughout the 2020 election, Biden strongly criticized Clinton's opponent, Donald Trump, in often colorful terms.[284][285]

Post-vice presidency (2017–19)

After leaving the Vice-Presidency, Biden became a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, while continuing to lead efforts to find treatments for cancer.[286] Biden wrote his memoir Promise Me, Dad in 2017 and went on a book tour.[287] Biden earned $15.6 million in 2017–18.[288] In 2018, he gave a eulogy for his close friend John McCain, US Senator from Arizona, praising the Senator's embrace of American ideals and bipartisan friendships.[289]

Biden remained in the public eye, endorsing candidates while continuing to comment on politics, climate change, and the ongoing presidency of Donald Trump.[290][291][292] He also continued to speak out in favor of LGBT rights, continuing advocacy on an issue which he had become more closely associated with during his Vice Presidency.[293][294] By 2019, Biden and his wife reported that their assets had increased to between $2.2 million and $8 million, thanks to speaking engagements and a contract to write a set of books.[295]

2020 presidential campaign

Speculation and announcement

Between 2016 and 2019, media outlets often mentioned Biden as a likely candidate for president in 2020.[296] When asked if he would run, he gave varied and ambivalent answers, saying "never say never".[297] At one point he suggested he did not see a scenario where he would run again,[298][299] but a few days later, he said, "I'll run if I can walk."[300] A political action committee known as Time for Biden was formed in January 2018, seeking Biden's entry into the race.[301]

Biden said he would decide whether to run or not by January 2019,[302] but made no announcement at that time. Friends said he was "very close to saying yes" but was concerned about the effect another presidential run could have on his family and reputation, as well as fundraising struggles and perceptions about his age and relative centrism.[303] On the other hand, he said he was prompted to run by his "sense of duty", offense at the Trump presidency, what he felt was a lack of foreign policy experience among other Democratic hopefuls, and his desire to foster "bridge-building progressivism" in the party.[303] He launched his campaign on April 25, 2019.[304]

Campaign

In September 2019, it was reported that Trump had pressured Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky to investigate alleged wrongdoing by Biden and his son Hunter Biden.[305] Despite the allegations, as of September 2019, no evidence has been produced of any wrongdoing by the Bidens.[306][307][308] The media widely interpreted this pressure to investigate the Bidens as trying to hurt Biden's chances of winning the presidency, resulting in a political scandal[309][310] and Trump's impeachment by the House of Representatives.

Beginning in 2019, Trump and his allies falsely accused Biden of getting the Ukrainian prosecutor general Viktor Shokin fired because he was supposedly pursuing an investigation into Burisma Holdings, which employed Hunter Biden. Biden was accused of withholding $1 billion in aid from Ukraine in this effort. In 2015, Biden pressured the Ukrainian parliament to remove Shokin because the United States, the European Union and other international organizations considered Shokin corrupt and ineffective, and in particular because Shokin was not assertively investigating Burisma. The withholding of the $1 billion in aid was part of this official policy.[311][312][313][314]

Throughout 2019, Biden stayed generally ahead of other Democrats in national polls.[315][316] Despite this, he finished fourth in the Iowa caucuses, and eight days later, fifth in the New Hampshire primary.[317][318] He performed better in the Nevada caucuses, reaching the 15% required for delegates, but still was behind Bernie Sanders by 21.6 percentage points.[319] Making strong appeals to black voters on the campaign trail and in the South Carolina debate, Biden won the South Carolina primary by more than 28 points.[320] After the withdrawals and subsequent endorsements of candidates Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, he made large gains in the March 3 Super Tuesday primary elections. Biden won 18 of the next 26 contests, including Alabama, Arkansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia, putting him in the lead overall.[321] Elizabeth Warren and Mike Bloomberg soon dropped out, and Biden expanded his lead with victories over Sanders in four states (Idaho, Michigan, Mississippi, and Missouri) on March 10.[322]

When Sanders suspended his campaign on April 8, 2020, Biden became the Democratic Party's presumptive nominee for president.[323] On April 13, Sanders endorsed Biden in a live-streamed discussion from their homes.[324] Former President Barack Obama endorsed Biden the next day.[325] In March 2020, Biden committed to choosing a woman as his running mate.[326] In June, Biden met the 1,991-delegate threshold needed to secure the party's presidential nomination.[1] On August 11, he announced U.S. Senator Kamala Harris of California as his running mate, making her the first African American and South Asian American vice-presidential nominee on a major-party ticket.[327]

On August 18, 2020, Biden was officially nominated at the 2020 Democratic National Convention as the Democratic Party nominee for president in the 2020 election.[328][329][330]

Allegations of inappropriate physical contact

Biden has been accused several times of inappropriate non-sexual contact, such as embracing, kissing, and gripping, and once of sexual assault.[331][332] He has described himself as a "tactile politician" and admitted this behavior has caused trouble for him in the past.[333]

By 2015, a series of swearings-in and other events at which Biden had placed his hands on people and talked closely to them attracted attention in the press and on social media.[334][335][336] Various people defended Biden, including a senator who issued a statement,[337] as well as Stephanie Carter, a woman whose photograph with Biden had gone viral, who described the photo as "misleadingly extracted from what was a longer moment between close friends".[338] On February 28, 2016, Biden gave a speech about sexual assault awareness at the 88th Academy Awards, before introducing Lady Gaga.[339]

In March 2019, former Nevada assemblywoman Lucy Flores alleged that Biden had touched her without her consent at a 2014 campaign rally in Las Vegas. In an op-ed, Flores wrote that Biden had walked up behind her, put his hands on her shoulders, smelled her hair, and kissed the back of her head, adding that the way he touched her was "an intimate way reserved for close friends, family, or romantic partners—and I felt powerless to do anything about it."[340] Biden's spokesman said Biden did not recall the behavior described.[341] Two days later, Amy Lappos, a former congressional aide to Jim Himes, said Biden touched her in a non-sexual but inappropriate way by holding her head to rub noses with her at a political fundraiser in Greenwich in 2009.[342] The next day, two more women came forward with allegations of inappropriate conduct. Caitlin Caruso said Biden placed his hand on her thigh, and D.J. Hill said he ran his hand from her shoulder down her back.[343][344] In early April 2019, three women told The Washington Post Biden had touched them in ways that made them feel uncomfortable.[345] In April 2019, former Biden staffer Tara Reade said she had felt uncomfortable on several occasions when Biden touched her on her shoulder and neck during her employment in his Senate office in 1993.[346] In March 2020, Reade accused him of a 1993 sexual assault.[347] Biden and his campaign vehemently denied the allegation.[348][349]

Biden apologized for not understanding how people would react to his actions, but said his intentions were honorable and that he would be more "mindful of people's personal space". He went on to say he was not sorry for anything he had ever done, which led critics to accuse him of sending a mixed message.[350]

President-elect of the United States

Biden was elected the 46th president of the United States in November 2020, defeating the incumbent, Donald Trump, the first sitting president to lose reelection since George H. W. Bush in 1992. He is the second non-incumbent vice president (after Richard Nixon in 1968) to be elected president.[351] He is also expected to become the oldest president,[352] as well as the first president whose home state is Delaware (although he was born in Pennsylvania), and the second Catholic president after John F. Kennedy. Biden is expected to be inaugurated at noon on January 20, 2021.[nb 3][nb 4]

Days after the election Biden created a COVID-19 task force[359][360] He pledged a larger government response to the pandemic than Trump's,[361] including increased testing, a steady supply of personal protective equipment, distributing a vaccine, and funds for schools and hospitals under the aegis[clarification needed] of a national "supply chain commander" who would coordinate manufacturing and distribution protective gear and test kits. This would be distributed by a "Pandemic Testing Board".[361] Biden also pledged to use the Defense Production Act more aggressively than Trump in order to build up supplies, as well as employ 100,000 contact tracers to track and limit outbreaks.[361]

On November 11, 2020, Biden chose Ron Klain as his White House Chief of Staff. Klain was a Senate aide to Biden in the 1980s, Biden's first chief of staff as Vice President, and chief of staff to Vice President Al Gore.[362]

On November 23, 2020, Biden made his first national security nominations and appointments, nominating Antony Blinken for Secretary of State, Alejandro Mayorkas for Secretary of Homeland Security, Avril Haines for Director of National Intelligence, Jake Sullivan for National Security Advisor, Linda Thomas-Greenfield for United States Ambassador to the United Nations, and former Secretary of State John Kerry for Special Presidential Envoy for Climate.[363] If confirmed, Haines would be the first woman to serve as Director of National Intelligence, and Mayorkas would be the first Latin American and immigrant to serve as head of the United States Department of Homeland Security.

Also on November 23, General Services Administrator Emily W. Murphy formally recognized Biden as the apparent winner of the 2020 presidential election and authorized the start of a transition process to the Biden administration.[364]

Political positions

Biden has been characterized as a moderate Democrat.[365] He has a lifetime liberal 72% score from the Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) through 2004, while the American Conservative Union (ACU) gave him a lifetime conservative rating of 13% through 2008.[366]

Biden supported the fiscal stimulus in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009;[367][368] the Obama administration's proposed increased infrastructure spending;[368] mass transit, including Amtrak, bus, and subway subsidies;[369] and the reduced military spending in the Obama administration's fiscal year 2014 budget.[370][371] He has proposed partially reversing the corporate tax cuts of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, saying that doing so would not hurt businesses' ability to hire.[372][373] He voted for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)[374] and the Trans-Pacific Partnership.[375] Biden is a staunch supporter of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).[376][377] He has promoted a plan to expand and build upon it, paid for by revenue gained from reversing some Trump administration tax cuts.[376] Biden's plan is to create a public option for health insurance, with the aim of expanding health insurance coverage to 97% of Americans.[378]

Biden has supported reproductive rights;[379] same-sex marriage;[380] the Roe v. Wade decision; and since 2019 has supported repealing the Hyde Amendment.[381][382] He opposes drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and supports governmental funding to find new energy sources.[383] He believes action must be taken on global warming. He co-sponsored the Sense of the Senate resolution calling on the United States to take part in the United Nations climate negotiations and the Boxer–Sanders Global Warming Pollution Reduction Act, the most stringent climate bill in the United States Senate.[384] He wants to achieve a carbon-free power sector in the U.S. by 2035 and stop emissions completely by 2050.[385] His program includes reentering Paris Agreement, nature conservation, and green building.[386] Biden wants to pressure China and other countries to cut greenhouse gas emissions, by carbon tariffs if necessary.[387][388] As a senator, he forged deep relationships with police groups and was a chief proponent of a Police Officer's Bill of Rights measure that police unions supported but police chiefs opposed. As vice president, he served as a White House liaison to police.[389][390]

Biden has said he is against regime change, but for providing non-military support to opposition movements.[391] He opposed intervention in Libya;[392][393] voted against U.S. participation in the Gulf War;[394] voted in favor of the Iraq War;[395] and supports a two-state solution in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.[396] Biden has pledged to end U.S. support for the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen and to reevaluate the relationship with Saudi Arabia.[397] He has called North Korea a "paper tiger".[398] As Vice President, Biden supported Obama's Cuban thaw.[399] He has said that, as president, he would restore U.S. membership in key United Nations bodies, such as UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the World Health Organization,[400] and possibly the Human Rights Council.[401] Biden pledged, if elected, to sanction and commercially restrict Chinese government officials and entities who carry out repression.[402]

Distinctions

Biden has received honorary degrees from the University of Scranton (1976),[403] Saint Joseph's University (LL.D 1981),[404] Widener University School of Law (2000),[58] Emerson College (2003),[405] Delaware State University (2003),[406] his alma mater the University of Delaware (LL.D 2004),[407] Suffolk University Law School (2005),[408] his other alma mater Syracuse University (LL.D 2009),[409] Wake Forest University (LL.D 2009),[410] the University of Pennsylvania (LL.D 2013),[411] Miami Dade College (2014),[412] University of South Carolina (DPA 2014),[413] Trinity College, Dublin (LL.D 2016),[414] Colby College (LL.D 2017),[415] and Morgan State University (DPS 2017).[416]

Biden also received the Chancellor Medal (1980) and the George Arents Pioneer Medal (2005) from Syracuse University.[417][418]

In 2008, Biden received Working Mother magazine's Best of Congress Award for "improving the American quality of life through family-friendly work policies".[419] Also in 2008, he shared with fellow senator Richard Lugar the Government of Pakistan's Hilal-i-Pakistan award "in recognition of their consistent support for Pakistan".[420] In 2009, Kosovo gave Biden the Golden Medal of Freedom, the region's highest award, for his vocal support for its independence in the late 1990s.[421]

Biden is an inductee of the Delaware Volunteer Firemen's Association Hall of Fame.[422] He was named to the Little League Hall of Excellence in 2009.[423]

On May 15, 2016, the University of Notre Dame gave Biden the Laetare Medal, considered the highest honor for American Catholics. The medal was simultaneously awarded to John Boehner, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives.[424][425]

On June 25, 2016, Biden received the Freedom of the City of County Louth in the Republic of Ireland.[426]

On January 12, 2017, Obama surprised Biden by awarding him the Presidential Medal of Freedom with Distinction—for "faith in your fellow Americans, for your love of country and a lifetime of service that will endure through the generations".[427][428] It was the only award by Obama of the Medal of Freedom with Distinction; other recipients include Ronald Reagan, Colin Powell and Pope John Paul II.[429]

On December 11, 2018, the University of Delaware renamed its School of Public Policy and Administration the Joseph R. Biden, Jr. School of Public Policy and Administration. The Biden Institute is housed there.[430]

Electoral history

| Election results | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Office | Party | Votes for Biden | % | Opponent | Party | Votes | % | |||

| 1970 | County councilor | 10,573 | 55% | Lawrence T. Messick | Republican | 8,192 | 43% | ||||

| 1972 | U.S. senator | 116,006 | 50% | J. Caleb Boggs | Republican | 112,844 | 49% | ||||

| 1978 | 93,930 | 58% | James H. Baxter Jr. | Republican | 66,479 | 41% | |||||

| 1984 | 147,831 | 60% | John M. Burris | Republican | 98,101 | 40% | |||||

| 1990 | 112,918 | 63% | M. Jane Brady | Republican | 64,554 | 36% | |||||

| 1996 | 165,465 | 60% | Raymond J. Clatworthy | Republican | 105,088 | 38% | |||||

| 2002 | 135,253 | 58% | Raymond J. Clatworthy | Republican | 94,793 | 41% | |||||

| 2008 | 257,484 | 65% | Christine O'Donnell | Republican | 140,584 | 35% | |||||

| 2008 | Vice president | 69,498,516 365 electoral votes (270 needed) |

53% | Sarah Palin | Republican | 59,948,323 173 electoral votes |

46% | ||||

| 2012 | 65,915,795 332 electoral votes (270 needed) |

51% | Paul Ryan | Republican | 60,933,504 206 electoral votes |

47% | |||||

| 2020 | President | >80,000,000; 306 electoral votes projected (270 needed) | TBA | Donald Trump | Republican | >73,000,000; 232 electoral votes projected | TBA | ||||

Publications

- Biden, Joseph R., Jr.; Helms, Jesse (April 1, 2000). Hague Convention On International Child Abduction: Applicable Law And Institutional Framework Within Certain Convention Countries Report To The Senate. Diane Publishing. ISBN 0-7567-2250-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Biden, Joseph R., Jr. (July 8, 2001). Putin Administration's Policies toward Non-Russian Regions of the Russian Federation: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 0-7567-2624-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Biden, Joseph R., Jr. (July 24, 2001). Administration's Missile Defense Program and the ABM Treaty: Hearing Before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 0-7567-1959-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Biden, Joseph R., Jr. (September 5, 2001). Threat of Bioterrorism and the Spread of Infectious Diseases: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 0-7567-2625-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Biden, Joseph R., Jr. (February 12, 2002). Examining The Theft Of American Intellectual Property At Home And Abroad: Hearing before the Committee On Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 0-7567-4177-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Biden, Joseph R., Jr. (February 14, 2002). Halting the Spread of HIV/AIDS: Future Efforts in the U.S. Bilateral & Multilateral Response: Hearings before the Comm. on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate. Diane Publishing. ISBN 0-7567-3454-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Biden, Joseph R., Jr. (February 27, 2002). How Do We Promote Democratization, Poverty Alleviation, and Human Rights to Build a More Secure Future: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 0-7567-2478-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Biden, Joseph R., Jr. (August 1, 2002). Hearings to Examine Threats, Responses, and Regional Considerations Surrounding Iraq: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 0-7567-2823-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Biden, Joseph R., Jr. (January 1, 2003). International Campaign Against Terrorism: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate. Diane Publishing. ISBN 0-7567-3041-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Biden, Joseph R., Jr. (January 1, 2003). Political Future of Afghanistan: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate. Diane Publishing. ISBN 0-7567-3039-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Biden, Joseph R., Jr. (September 1, 2003). Strategies for Homeland Defense: A Compilation by the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate. Diane Publishing. ISBN 0-7567-2623-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Biden, Joseph (2005). "Foreword". In Nicholson, William C. (ed.). Homeland Security Law and Policy. C. C Thomas. ISBN 0-398-07583-2.

- Biden, Joe (July 31, 2007). Promises to Keep. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6536-3. Also paperback edition, Random House 2008, ISBN 0-8129-7621-5.

- Biden, Joe (November 14, 2017). Promise Me, Dad: A Year of Hope, Hardship, and Purpose. Flatiron Books. ISBN 978-1-250-17167-2.

Notes

- ^ Biden admired McCain politically as well as personally. In May 2004, he had urged McCain to run as vice president with presumptive Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry, saying the cross-party ticket would help heal the "vicious rift" in U.S. politics.[166]

- ^ Delaware's Democratic governor, Ruth Ann Minner, announced on November 24, 2008, that she would appoint Biden's longtime senior adviser Ted Kaufman to succeed Biden in the Senate.[179] Kaufman said he would serve only two years, until Delaware's special Senate election in 2010.[179] Biden's son Beau ruled himself out of the 2008 selection process due to his impending tour in Iraq with the Delaware Army National Guard.[180] He was a possible candidate for the 2010 special election, but in early 2010 said he would not run for the seat.[181]

- ^ As of Monday, November 9, 2020, ever since major media outlets called the election for Biden a few days earlier, most reliable sources have been referring to Joe Biden as president-elect, and to Kamala Harris as vice president-elect. At that time, incumbent president Donald Trump was still refusing to concede defeat and claiming the election had been stolen from him by alleged electoral fraud, and Emily W. Murphy, the Trump-appointed Administrator of the General Services Administration (GSA), whose task it is to formally certify the winners as "President-elect" and "Vice-President-elect" in order to start the transition,[353][354] had not yet done so.[355][354] The criteria for the GSA to certify the winners are "legally murky".[354]

- ^ However, like previous potential transition teams, such as that of unsuccessful candidate Mitt Romney in 2012, the Biden transition team remains eligible for government funding in accordance with the Pre-Election Presidential Transition Act of 2010,[356][357] and Biden has been eligible to receive classified intelligence briefings since his nomination in August.[358] At least some government agencies had reportedly started their transition plans as of November 9, 2020, with airspace being restricted over his home, and "the Secret Service has begun using agents from its presidential protective detail for the president-elect and his family."[354]

References

Citations

- ^ a b Linskey, Annie (June 9, 2020). "Biden clinches the Democratic nomination after securing more than 1,991 delegates".

- ^ "Joe Biden elected president". CNN. November 7, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ "US Election 2020: Joe Biden wins the presidency". BBC News. November 7, 2020. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Witcover, Jules (2010). Joe Biden: A Life of Trial and Redemption. New York City: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-179198-7.

- ^ Chase, Randall (January 9, 2010). "Vice President Biden's mother, Jean, dies at 92". WITN-TV. Associated Press.

- ^ "Joseph Biden Sr., 86, father of the senator". The Baltimore Sun. September 3, 2002. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Smolenyak, Megan (July 2, 2012). "Joe Biden's Irish Roots". Huffington Post. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ "Number two Biden has a history over Irish debate". The Belfast Telegraph. November 9, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- ^ Smolenyak, Megan (April–May 2013). "Joey From Scranton—Vice President Biden's Irish Roots". Irish America. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ https://www.telegraph.co.uk/family/life/joe-biden-family-tree-children-ashley-hunter/

- ^ Biden, Joe (2008). Promises to Keep: On Life and Politics. Random House. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0812976212.

- ^ Witcover, Jules (2019). Joe Biden: A Life of Trial and Redemption. William Morrow. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0062982643.