Newt Gingrich

Newt Gingrich | |

|---|---|

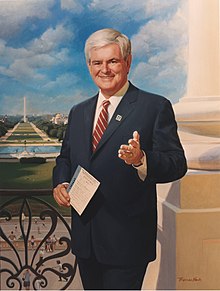

Gingrich in 2022 | |

| 50th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives | |

| In office January 4, 1995 – January 3, 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Tom Foley |

| Succeeded by | Dennis Hastert |

| Leader of the House Republican Conference | |

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 3, 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Robert H. Michel |

| Succeeded by | Dennis Hastert |

| House Minority Whip | |

| In office March 20, 1989 – January 3, 1995 | |

| Leader | Robert H. Michel |

| Preceded by | Dick Cheney |

| Succeeded by | David Bonior |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's 6th district | |

| In office January 3, 1979 – January 3, 1999 | |

| Preceded by | John Flynt |

| Succeeded by | Johnny Isakson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Newton Leroy McPherson June 17, 1943 Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | Jackie Battley

(m. 1962; div. 1981)Marianne Ginther

(m. 1981; div. 2000) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Candace Gingrich (maternal half-sibling) |

| Education | Emory University (BA) Tulane University (MA, PhD) |

| Signature |  |

| Website | Official website |

Newton Leroy Gingrich (/ˈɡɪŋɡrɪtʃ/; né McPherson; born June 17, 1943) is an American politician and author who served as the 50th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1995 to 1999. A member of the Republican Party, he was the U.S. representative for Georgia's 6th congressional district serving north Atlanta and nearby areas from 1979 until his resignation in 1999. In 2012, Gingrich unsuccessfully ran for the Republican nomination for president of the United States.

In the 1970s, Gingrich was a professor of history and geography at the University of West Georgia. He won election to the U.S. House of Representatives in November 1978, the first Republican in the history of Georgia's 6th congressional district to do so. He served as House Minority Whip from 1989 to 1995.[1][2] A co-author and architect of the "Contract with America", Gingrich was a major leader in the Republican victory in the 1994 congressional election. In 1995, Time named him "Man of the Year" for "his role in ending the four-decades-long Democratic majority in the House".[3]

As House Speaker, Gingrich oversaw passage by the House of welfare reform in 1996 and a capital gains tax cut in 1997. Gingrich played a key role in several government shutdowns, and impeached President Bill Clinton on a party-line vote in the House. A disappointing showing by Republicans in the 1998 congressional elections, a reprimand from the House for Gingrich's ethics violation, and pressure from Republican colleagues resulted in Gingrich's announcing that he would not run for the speakership in the upcoming congress, resigning from the House on January 3, 1999, the same day his term as speaker ended.[4] Academics have credited Gingrich with playing a key role in hastening political polarization and partisanship.[5][6][7][8][9][page needed]

Since leaving the House, Gingrich has remained active in public policy debates and worked as a political consultant. He founded and chaired several policy think tanks, including American Solutions for Winning the Future and the Center for Health Transformation. Gingrich ran for the Republican nomination for president in the 2012 presidential election, and was considered a potential frontrunner at several points in the race.[10] Despite a late victory in the South Carolina primary, Gingrich was ultimately unable to win enough primaries to sustain a viable candidacy. He withdrew from the race in May 2012, and endorsed eventual nominee Mitt Romney. Gingrich later emerged as a key ally of President Donald Trump, and was reportedly among the finalists on Trump's short list for running mate in the 2016 election.[11] Since 2020, Gingrich has supported Donald Trump's claims of a stolen election, and claims of voter fraud in the 2020 presidential election.[12]

Early life

[edit]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

U.S. Speaker of the House

2012 presidential election

Organizations

Writing

|

||

Gingrich was born as Newton Leroy McPherson at the Harrisburg Hospital in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, on June 17, 1943. His mother, Kathleen "Kit" (née Daugherty; 1925–2003), and biological father, Newton Searles McPherson (1923–1970),[13] married in September 1942, when she was 16 and McPherson was 19. The marriage fell apart within days.[14][15][16] He is of English, German, Scottish and Scots-Irish descent.[17][18]

In 1946, his mother married Robert Gingrich (1925–1996), who adopted him.[19] Robert Gingrich was a career Army officer who served tours in Korea and Vietnam. In 1956, the family moved to Europe, living for a period in Orléans, France and Stuttgart, Germany.[20]

Gingrich has three younger half-siblings from his mother, Candace and Susan Gingrich, and Roberta Brown.[19] Gingrich was raised in Hummelstown (near Harrisburg) and on military bases where his adoptive father was stationed. The family's religion was Lutheran.[21] He also has a half-sister and half-brother, Randy McPherson, from his biological father's side. In 1960 during his junior year in high school, the family moved to Georgia at Fort Moore.[20]

In 1961, Gingrich graduated from Baker High School in Columbus, Georgia, where he met, and later married, his math teacher. He had been interested in politics since his teen years. While living with his family in Orléans, France, he visited the site of the Battle of Verdun and learned about the sacrifices made there and the importance of political leadership.[22]

Gingrich received a Bachelor of Arts degree in history from Emory University in Atlanta in 1965. He went on to graduate study at Tulane University, earning an M.A. (1968) and a PhD in European history (1971).[23] He spent six months in Brussels in 1969–1970 working on his dissertation, Belgian Education Policy in the Congo 1945–1960.[24][25]

Gingrich received deferments from the military during the years of the Vietnam War for being a student and a father. In 1985, he stated, "Given everything I believe in, a large part of me thinks I should have gone over."[26]

In 1970, Gingrich joined the history department at West Georgia College, where he spent "little time teaching history."[27] He coordinated a new environmental studies program and was moved from the history to the geography department by 1976.[27] During his time in the college, he took unpaid leave three times to run for the U.S. House of Representatives, losing twice before leaving the college. Serving professors were not allowed under the rules of the university system to run for office. He left the college in 1977 after being denied tenure.[27]

Early political career

[edit]Gingrich was the southern regional director for Nelson Rockefeller in the 1968 Republican primaries.[28]

Congressional campaigns

[edit]

In 1974, Gingrich made his first bid for political office as the Republican candidate in Georgia's 6th congressional district in north-central Georgia. He lost to 20-year incumbent Democrat Jack Flynt by 2,770 votes.[29] Gingrich's relative success surprised political analysts. Flynt had never faced a serious challenger; Gingrich was the second Republican to ever run against him.[30] He did well against Flynt although 1974 was a disastrous year for Republican candidates nationally due to fallout from the Watergate scandal of the Nixon administration.[31]

Gingrich sought a rematch against Flynt in 1976. While the Republicans did slightly better in the 1976 House elections than in 1974 nationally, the Democratic candidate in the 1976 presidential election was former Governor of Georgia Jimmy Carter. Carter won more than two-thirds of the vote in his native Georgia.[32] Gingrich lost his race by 5,100 votes.[33] As Gingrich primed for another run in the 1978 elections, Flynt decided to retire. Gingrich defeated Democratic State Senator Virginia Shapard by 7,500 votes.[34][35] Gingrich was re-elected five times from this district, before it was modified by redistricting.[36] He faced a close general election race once—in the House elections of 1990—when he won by 978 votes in a primary race against Republican Herman Clark and won a narrow 974 vote victory over Democrat David Worley in the general.[37] Although the district was trending Republican at the national level, conservative Democrats continued to hold most local offices, as well as most of the area's seats in the General Assembly, well into the 1980s.[38]

Congress

[edit]In 1981, Gingrich co-founded the Military Reform Caucus (MRC) and the Congressional Aviation and Space Caucus. During the 1983 congressional page sex scandal, Gingrich was among those calling for the expulsion of representatives Dan Crane and Gerry Studds.[39] Gingrich supported a proposal to ban loans from the International Monetary Fund to Communist countries and he endorsed a bill to make Martin Luther King Jr. Day a new federal holiday.[40]

In 1983, Gingrich founded the Conservative Opportunity Society (COS), a group that included young conservative House Republicans. Early COS members included Robert Smith Walker, Judd Gregg, Dan Coats and Connie Mack III. The group gradually expanded to include several dozen representatives,[41] who met each week to exchange and develop ideas.[40]

Gingrich's analysis of polls and public opinion identified the group's initial focus.[41] Ronald Reagan adopted the "opportunity society" ideas for his 1984 re-election campaign, supporting the group's conservative goals on economic growth, education, crime, and social issues. He had not emphasized these during his first term.[42] Reagan also referred to an "opportunity" society in the first State of the Union address of his second term.[41]

In March 1988, Gingrich voted against the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 (as well as to uphold President Reagan's veto).[43][44] In May 1988, Gingrich (along with 77 other House members and Common Cause) brought ethics charges against Democratic Speaker Jim Wright, who was alleged to have used a book deal to circumvent campaign-finance laws and House ethics rules. During the investigation, it was reported that Gingrich had his own unusual book deal, for Window of Opportunity, in which publicity expenses were covered by a limited partnership. It raised $105,000 from Republican political supporters to promote sales of Gingrich's book.[45] Gingrich's success in forcing Wright's resignation contributed to his rising influence in the Republican caucus.[46]

In March 1989, Gingrich became House Minority Whip in a close election against Edward Rell Madigan.[47] This was Gingrich's first formal position of power within the Republican party.[48] He said his intention was to "build a much more aggressive, activist party".[47] Early in his role as Whip, in May 1989, Gingrich was involved in talks about the appointment of a Panamanian administrator of the Panama Canal, which was scheduled to occur in 1989 subject to U.S. government approval. Gingrich was outspoken in his opposition to giving control over the canal to an administrator appointed by the dictatorship in Panama.[49]

Gingrich and others in the House, including the newly minted Gang of Seven, railed against what they saw as ethical lapses during the nearly 40 years of Democratic control. The House banking scandal and Congressional Post Office scandal were emblems of the exposed corruption. Gingrich himself was among members of the House who had written NSF checks on the House bank. He had overdrafts on twenty-two checks, including a $9,463 check to the Internal Revenue Service in 1990.[50]

In 1990, after consulting focus groups[51] with the help of pollster Frank Luntz,[52] GOPAC distributed a memo with a cover letter signed by Gingrich titled "Language, a Key Mechanism of Control", that encouraged Republicans to "speak like Newt". It contained lists of "contrasting words"—words with negative connotations such as "radical", "sick," and "traitors"—and "optimistic positive governing words" such as "opportunity", "courage", and "principled", that Gingrich recommended for use in describing Democrats and Republicans, respectively.[51]

During negotiations with the Democrats who held majorities in the House and Senate, President George H. W. Bush reached a deficit reduction package which contained tax increases despite his campaign promise of "read my lips: no new taxes". Gingrich led a revolt that defeated the initial appropriations package and led to the 1990 United States federal government shutdown. The deal was supported by the President and Congressional leaders from both parties after long negotiations, but Gingrich walked out during a televised event in the White House Rose Garden. House Minority Leader Robert H. Michel characterized Gingrich's revolt as "a thousand points of spite".[53][54]

Due to population increases recorded in the 1990 United States census, Georgia picked up an additional seat for the 1992 U.S. House elections. However, the Democratic-controlled Georgia General Assembly, under the leadership of fiercely partisan Speaker of the House Tom Murphy, specifically targeted Gingrich, eliminating the district Gingrich represented.[55] Gerrymandering split Gingrich's territory among three neighboring districts. Much of the southern portion of Gingrich's district, including his home in Carrollton, was drawn into the Columbus-based 3rd district, represented by five-term Democrat Richard Ray. Gingrich remarked that "The Speaker, by raising money and gerrymandering, has sincerely dedicated a part of his career to wiping me out."[55] Charles S. Bullock III, a political science professor at the University of Georgia, said "Speaker Murphy didn't like having a Republican represent him."[56] At the onset of the decade, Gingrich proved to be the only Republican representative of Georgia's 10 congressional districts until 1992, with the creation of Georgia's 4th congressional district and the Republican gains of Jack Kingston and Mac Collins.[57]

The Assembly created a new, heavily Republican 6th district in Fulton and Cobb counties in the wealthy northern suburbs of Atlanta—an area that Gingrich had never represented. Gingrich sold his home in Carrollton and moved to Marietta in the new district. His primary opponent, State Representative Herman Clark, who had challenged Gingrich two years earlier, made an issue out of Gingrich's 22 overdraft checks in the House banking scandal, and also criticized Gingrich for moving into the district. After a recount, Gingrich prevailed by 980 votes, with a 51 to 49 percent result.[58] His winning the primary all but assured him of election in November. He was re-elected three times from this district against nominal Democratic opposition.[56]

In 1995, Gingrich's 1993 college course, entitled Renewing American Civilization, taught on Saturdays at Reinhardt College in Waleska, Georgia, was televised on the cable channel, Mind Extension University.[59]

In the 1994 campaign season, in an effort to offer an alternative to Democratic policies and to unite distant wings of the Republican Party, Gingrich and several other Republicans came up with a Contract with America, which laid out 10 policies that Republicans promised to bring to a vote on the House floor during the first 100 days of the new Congress, if they won the election.[60] The contract was signed by Gingrich and other Republican candidates for the House of Representatives. The contract ranged from issues such as welfare reform, term limits, crime, and a balanced budget/tax limitation amendment, to more specialized legislation such as restrictions on American military participation in United Nations missions.[61]

Republican Revolution

[edit]In the November 1994 midterm elections, Republicans gained 54 seats and took control of the House for the first time since 1954. Long-time House Minority Leader Bob Michel of Illinois had not run for re-election, giving Gingrich, the highest-ranking Republican returning to Congress, the inside track at becoming Speaker. The midterm election that turned congressional power over to Republicans "changed the center of gravity" in the nation's capital.[62] Time magazine named Gingrich its 1995 "Man of the Year" for his role in the election.[3]

Speaker of the House

[edit]

The House fulfilled Gingrich's promise to bring all ten of the Contract's issues to a vote within the first 100 days of the session. President Clinton called it the "Contract on America".[63]

Legislation proposed by the 104th United States Congress included term limits for Congressional Representatives, tax cuts, welfare reform, and a balanced budget amendment, as well as independent auditing of the finances of the House of Representatives and elimination of non-essential services such as the House barbershop and shoe-shine concessions. Following Gingrich's first two years as House Speaker, the Republican majority was re-elected in the 1996 election, the first time Republicans had done so in 68 years and the first time in 80 years that they won a House election simultaneous to a Democratic president being re-elected.[a][64]

As Speaker, Gingrich sought to increasingly tie Christian conservatism to the Republican Party. According to a 2018 study, Christian conservatism had become firmly ingrained in the Republican Party's policy platforms by 2000.[5] Yale University congressional scholar David Mayhew describes Gingrich as profoundly influential, saying "In Gingrich, we have as good a case as we are likely to see of a member of Congress operating in the public sphere with consequence."[65]

In 1997 Speaker Gingrich visited Taiwan as well as Beijing in mainland China.[66]

Role in political polarization

[edit]A number of scholars have credited Gingrich with playing a key role in undermining democratic norms in the United States, and hastening political polarization and partisan prejudice.[5][6][7][67][68][69][70][71][8][72][73][9] According to Harvard University political scientists Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky, Gingrich's speakership had a profound and lasting impact on American politics and health of American democracy. They argue that Gingrich instilled a "combative" approach in the Republican Party, where hateful language and hyper-partisanship became commonplace, and where democratic norms were abandoned. Gingrich frequently questioned the patriotism of Democrats, called them corrupt, compared them to fascists, and accused them of wanting to destroy the United States. Gingrich furthermore oversaw several major government shutdowns.[74][75][76][53]

University of Maryland political scientist Lilliana Mason identified Gingrich's instructions to Republicans to use words such as "betray, bizarre, decay, destroy, devour, greed, lie, pathetic, radical, selfish, shame, sick, steal, and traitors" about Democrats as an example of a breach in social norms and exacerbation of partisan prejudice.[5] Gingrich is a key figure in the 2017 book The Polarizers by Colgate University political scientist Sam Rosenfeld about the American political system's shift to polarization and gridlock.[6] Rosenfeld describes Gingrich as follows, "For Gingrich, responsible party principles were paramount... From the outset, he viewed the congressional minority party's role in terms akin to those found in parliamentary systems, prioritizing drawing stark programmatic contrasts over engaging the majority party as junior participants in governance."[6]

Boston College political scientist David Hopkins writes that Gingrich helped to nationalize American politics in a way where Democratic politicians on the state and local level were increasingly tied to the national Democratic party and President Clinton. Hopkins notes that Gingrich's view[73]

directly contradicted the conventional wisdom of politics... that parties in a two-party system achieve increasing electoral success as they move closer to the ideological center... Gingrich and his allies believed that an organized effort to intensify the ideological contrast between the congressional parties would allow the Republicans to make electoral inroads in the South. They worked energetically to tie individual Democratic incumbents to the party's more liberal national leadership while simultaneously raising highly charged cultural issues in Congress, such as proposed constitutional amendments to allow prayer in public schools and to ban the burning of the American flag, on which conservative positions were widely popular – especially among southern voters.

Gingrich's view was however vindicated with the Republican Party's success in the 1994 U.S. midterm elections, sometimes referred to as the "Gingrich Revolution."[73] Hopkins writes, "More than any speaker before or since, Gingrich had become both the strategic architect and public face of his party."[73] One consequence of the increasing nationalization of politics was that moderate Republican incumbents in blue states were left more vulnerable to electoral defeat.[73]

According to University of Texas political scientist Sean M. Theriault, Gingrich had a profound influence on other Republican lawmakers, in particular those who served with him in the House, as they adopted his obstructionist tactics.[7] A 2011 study by Theriault and Duke University political scientist David W. Rohde in the Journal of Politics found that "almost the entire growth in Senate party polarization since the early 1970s can be accounted for by Republican senators who previously served in the House after 1978" when Gingrich was first elected to the House.[77]

Gingrich consolidated power in the Speaker's office.[72] Gingrich elevated junior and more ideologically extreme House members to powerful committees, such as the Appropriations Committee, which over time led to the obliteration of internal norms in the committees.[70][78] Term limits were also imposed on committee chairs, which prevented Republican chairs from developing a power base separate from the Republican Party.[78] As a result, the power of Gingrich was strengthened and there was an increase in conformity among Republican congresspeople.[79]

Legislation

[edit]Welfare reform

[edit]A central pledge of President Bill Clinton's campaign was to reform the welfare system, adding changes such as work requirements for recipients. However, by 1994, the Clinton administration appeared to be more concerned with pursuing a universal health care program. Gingrich accused Clinton of stalling on welfare, and proclaimed that Congress could pass a welfare reform bill in as little as 90 days. He insisted that the Republican Party would continue to apply political pressure on the President to approve their welfare legislation.[80]

In 1996, after constructing two welfare reform bills that Clinton vetoed,[81] Gingrich and his supporters pushed for passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act, which was intended to reconstruct the welfare system. The act gave state governments more autonomy over welfare delivery, while also reducing the federal government's responsibilities. It instituted the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, which placed time limits on welfare assistance and replaced the longstanding Aid to Families with Dependent Children program. Other changes to the welfare system included stricter conditions for food stamp eligibility, reductions in immigrant welfare assistance, and work requirements for recipients.[82] The bill was signed into law by President Clinton on August 22, 1996.[83]

In his 1998 book Lessons Learned the Hard Way, Gingrich encouraged volunteerism and spiritual renewal, placing more importance on families, creating tax incentives and reducing regulations for businesses in poor neighborhoods, and increasing property ownership by low-income families. He also praised Habitat for Humanity for sparking the movement to improve people's lives by helping them build their own homes.[84]

Balancing the federal budget

[edit]

A key aspect of the 1994 Contract with America was the promise of a balanced federal budget. After the end of the government shutdown, Gingrich and other Republican leaders acknowledged that Congress would not be able to draft a balanced budget in 1996. Instead, they opted to approve some small reductions that were already approved by the White House and to wait until the next election season.[85]

By May 1997, Republican congressional leaders reached a compromise with Democrats and President Clinton on the federal budget. The agreement called for a federal spending plan designed to reduce the federal deficit and achieve a balanced budget by 2002. The plan included a total of $152 billion in bipartisan tax cuts over five years.[86] Other major parts of the spending plan called for $115 billion to be saved through a restructuring of Medicare, $24 billion set aside to extend health insurance to children of the working poor, tax credits for college tuition, and a $2 billion welfare-to-work jobs initiative.[87][88]

President Clinton signed the budget legislation in August 1997. At the signing, Gingrich gave credit to ordinary Americans stating, "It was their political will that brought the two parties together."[86]

In early 1998, with the economy performing better than expected, increased tax revenues helped reduce the federal budget deficit to below $25 billion. Clinton submitted a balanced budget for 1999, three years ahead of schedule originally proposed, making it the first time the federal budget had been balanced since 1969.[89]

Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997

[edit]In 1997, President Clinton signed into effect the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, which included the largest capital gains tax cut in U.S. history. Under the act, the profits on the sale of a personal residence ($500,000 for married couples, $250,000 for singles) were exempted if lived in for at least two of the previous five years. (This had previously been limited to a $125,000 once-in-a-lifetime exemption for those over the age of 55.)[90] There were also reductions in a number of other taxes on investment gains.[91][92]

Additionally, the act raised the value of inherited estates and gifts that could be sheltered from taxation.[92] Gingrich has been credited with creating the agenda for the reduction in capital gains tax, especially in the "Contract with America", which set out to balance the budget and implement decreases in estate and capital gains tax. Some Republicans felt that the compromise reached with Clinton on the budget and tax act was inadequate,[93] however Gingrich has stated that the tax cuts were a significant accomplishment for the Republican Congress in the face of opposition from the Clinton administration.[94] Gingrich along with Bob Dole had earlier set-up the Kemp Commission, headed by former US Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Jack Kemp, a tax reform commission that made several recommendations including that dividends, interest, and capital gains should be untaxed.[95][96]

Other legislation

[edit]Among the first pieces of legislation passed by the new Congress under Gingrich was the Congressional Accountability Act of 1995, which subjected members of Congress to the same laws that apply to businesses and their employees, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. As a provision of the Contract with America, the law was symbolic of the new Republican majority's goal to remove some of the entitlements enjoyed by Congress. The bill received near universal acceptance from the House and Senate and was signed into law on January 23, 1995.[97]

Gingrich shut down the highly regarded Office of Technology Assessment, and relied instead on what the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists called "self-interested lobbyists and think tanks".[98]

Government shutdown

[edit]

Gingrich and the incoming Republican majority's promise to slow the rate of government spending conflicted with the president's agenda for Medicare, education, the environment and public health, leading to two temporary shutdowns of the federal government totaling 28 days.[99]

Clinton said Republican amendments would strip the U.S. Treasury of its ability to dip into federal trust funds to avoid a borrowing crisis. Republican amendments would have limited appeals by death-row inmates, made it harder to issue health, safety and environmental regulations, and would have committed the president to a seven-year balanced budget. Clinton vetoed a second bill allowing the government to keep operating beyond the time when most spending authority expires.[99]

A GOP amendment opposed by Clinton would not only have increased Medicare Part B premiums, but it would also cancel a scheduled reduction. The Republicans held out for an increase in Medicare Part B premiums in January 1996 to $53.50 a month. Clinton favored the then current law, which was to let the premium that seniors pay drop to $42.50.[99]

The government closed most non-essential offices during the shutdown, which was the longest in U.S. history at the time. The shutdown ended when Clinton agreed to submit a CBO-approved balanced budget plan.[100]

During the crisis, Gingrich's public image suffered from the perception that the Republicans' hardline budget stance was owed partly to an alleged snub of Gingrich by Clinton during a flight on Air Force One to and from Yitzhak Rabin's funeral in Israel.[101] That perception developed after the trip when Gingrich, while being questioned by Lars-Erik Nelson at a Christian Science Monitor breakfast, said that he was dissatisfied that Clinton had not invited him to discuss the budget during the flight.[102] He complained that he and Dole were instructed to use the plane's rear exit to deplane, saying the snub was "part of why you ended up with us sending down a tougher continuing resolution".[103] In response to Gingrich's complaint that they were "forced to use the rear door," NBC news released their videotape footage showing both Gingrich and Dole disembarking at Tel Aviv just behind Clinton via the front stairway.[104]

Gingrich was widely lampooned for implying that the government shutdown was a result of his personal grievances, including a widely shared editorial cartoon depicting him as a baby throwing a tantrum.[105][106][107][108]

Democratic leaders, including Chuck Schumer, took the opportunity to attack Gingrich's motives for the budget standoff.[109][110] In 1998, Gingrich said that these comments were his "single most avoidable mistake" as Speaker.[111]

Discussing the impact of the government shutdown on the Republican Party, Gingrich later commented that, "Everybody in Washington thinks that was a big mistake. They're exactly wrong. There had been no reelected Republican majority since 1928. Part of the reason we got reelected ... is our base thought we were serious. And they thought we were serious because when it came to a show-down, we didn't flinch."[112] In a 2011 op-ed in The Washington Post, Gingrich said that the government shutdown led to the balanced-budget deal in 1997 and the first four consecutive balanced budgets since the 1920s, as well as the first re-election of a Republican majority since 1928.[113]

Ethics charges and reprimand

[edit]

Eighty-four ethics charges were filed by Democrats against Gingrich during his term as Speaker. All were eventually dropped except for one: claiming tax-exempt status for a college course run for political purposes.[114] On January 21, 1997, the House officially reprimanded Gingrich (in a vote of 395 in favor, 28 opposed) and "ordered [him] to reimburse the House for some of the costs of the investigation in the amount of $300,000".[115][116][117] It was the first time a Speaker was disciplined for an ethics violation.[117][118]

Additionally, the House Ethics Committee concluded that inaccurate information supplied to investigators on behalf of Gingrich represented "intentional or ... reckless" disregard of House rules.[119] The Ethics Committee's Special Counsel James M. Cole concluded that Gingrich had violated federal tax law and had lied to the ethics panel in an effort to force the committee to dismiss the complaint against him. The full committee panel did not agree whether tax law had been violated and left that issue up to the IRS.[119] In 1999, the IRS cleared the organizations connected with the "Renewing American Civilization" courses under investigation for possible tax violations.[120]

Regarding the situation, Gingrich said in January 1997, "I did not manage the effort intensely enough to thoroughly direct or review information being submitted to the committee on my behalf. In my name and over my signature, inaccurate, incomplete and unreliable statements were given to the committee, but I did not intend to mislead the committee ... I brought down on the people's house a controversy which could weaken the faith people have in their government."[121]

Leadership challenge

[edit]

In the summer of 1997, several House Republicans attempted to replace him as Speaker, arguing Gingrich's public image was a liability. The attempted "coup" began July 9 with a meeting of Republican conference chairman John Boehner of Ohio and Republican leadership chairman Bill Paxon of New York. According to their plan, House Majority Leader Dick Armey, House Majority Whip Tom DeLay, Boehner and Paxon were to present Gingrich with an ultimatum: resign, or be voted out.

However, Armey balked at the proposal to make Paxon the new Speaker, and told his chief of staff to warn Gingrich.[122] On July 11, Gingrich met with senior Republican leadership to assess the situation. He explained that under no circumstance would he step down. If he was voted out, there would be a new election for Speaker. This would allow for the possibility that Democrats, along with dissenting Republicans, would vote in Democrat Dick Gephardt as Speaker.

On July 16, Paxon offered to resign his post, feeling that he had not handled the situation correctly, as the only member of the leadership who had been appointed to his position – by Gingrich – instead of elected.[123] Gingrich accepted Paxon's resignation and directed Paxon to immediately vacate his leadership office space.[123][124][125]

Resignation

[edit]In 1998, Gingrich's private polls had given his fellow Republicans the impression that pushing the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal would damage Clinton's popularity and result in the party winning a net total of six to thirty seats in the House of Representatives. At the same time, Gingrich was having an affair with a woman 23 years his junior.[126] But instead of gaining seats, Republicans lost five, the worst midterm performance in 64 years by a party not holding the presidency.[127] Other ethics violations, including an unpopular book deal, added to his unpopularity even though he himself was reelected in his own district.[128][129]

The day after the election, a Republican caucus ready to rebel against him prompted his resignation of the speakership. He also announced his intended and eventual full departure from the House a few weeks later. In January 1999 he resigned his seat.[130] When relinquishing the speakership, Gingrich referred to other Republicans when he said he was "not willing to preside over people who are cannibals".[130] Writing a retrospective on his career at that point, The New York Times in November 1998 described Gingrich as "an expert in how to seize power, but a novice in holding it" further opining that he "illustrate[d] how hard it is for a radical, polarizing figure to last in leadership".[131]

In December 1997, Gingrich flirted with a potential run for president in the 2000 election, but his party's midterm performance and his subsequent resignation led to him drop any plans to do so.[132]

Post-speakership

[edit]Gingrich has since remained involved in national politics and public policy debate. McKay Coppins of The Atlantic summarized time with Gingrich in 2018:

[Gingrich] is dabbling in geopolitics, dining in fine Italian restaurants. When he feels like traveling, he crisscrosses the Atlantic in business class, opining on the issues of the day from bicontinental TV studios and giving speeches for $600 a minute. There is time for reading, and writing, and midday zoo trips—and even he will admit, "It's a very fun life."[133]

Policy

[edit]

In 2003, he founded the Center for Health Transformation. Gingrich supported the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, which created the Medicare Part D federal prescription drugs benefit program. Some conservatives have criticized him for favoring the plan, due to its cost. In a May 15, 2011, interview on Meet the Press, Gingrich repeated his long-held belief that "all of us have a responsibility to pay—help pay for health care", and suggested this could be implemented by either a mandate to obtain health insurance or a requirement to post a bond ensuring coverage.[134][135] In the same interview Gingrich said "I don't think right-wing social engineering is any more desirable than left-wing social engineering. I don't think imposing radical change from the right or the left is a very good way for a free society to operate." This comment caused backlash within the Republican Party.[134][135]

In 2005, with Hillary Clinton, Gingrich announced the proposed 21st Century Health Information Act, a bill which aimed to replace paperwork with confidential, electronic health information networks.[136] Gingrich also co-chaired an independent congressional study group made up of health policy experts formed in 2007 to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of action taken within the U.S. to fight Alzheimer's disease.[137]

Gingrich has served on several commissions, including the Hart–Rudman Commission, formally known as the U.S. Commission on National Security/21st century, which examined national security issues affecting the armed forces, law enforcement and intelligence agencies.[138] In 2005 he became the co-chair of a task force for UN reform, which aimed to produce a plan for the U.S. to help strengthen the UN.[139] For over two decades, Gingrich has taught at the United States Air Force's Air University, where, as of 2010, he was the longest-serving teacher of the Joint Flag Officer Warfighting Course.[140] In addition, he is an honorary distinguished visiting scholar and professor at the National Defense University and, as of 2012, was teaching officers from all of the defense services.[141][142] Gingrich informally advised Defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld on strategic issues, on issues including the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and encouraging the Pentagon to not "yield" foreign policy influence to the State Department and National Security Council.[143] Gingrich is also a guiding coalition member of the Project on National Security Reform.[144]

Gingrich founded and served as the chairman of American Solutions for Winning the Future, a 527 group established in 2007.[145] The group was a "fundraising juggernaut" that raised $52 million from major donors, such as Sheldon Adelson and the coal company Peabody Energy.[145] The group promoted deregulation and increased offshore oil drilling and other fossil-fuel extraction and opposed the Employee Free Choice Act;[145][146] Politico reported, "The operation, which includes a pollster and fundraisers, promotes Gingrich's books, sends out direct mail, airs ads touting his causes and funds his travel across the country."[146] American Solutions closed in 2011 after he left the organization.[145]

Other organizations and companies founded or chaired by Gingrich include the creative production company Gingrich Productions,[147] and religious educational organization Renewing American Leadership.[148]

Gingrich is a former member of the Council on Foreign Relations.[149]

He is a fellow at conservative think tanks the American Enterprise Institute and Hoover Institution. He sometimes serves as a commentator, guest or panel member on cable news shows, such as the Fox News Channel. He is listed as a contributor by Fox News Channel, and frequently appears as a guest on various segments; he has also hosted occasional specials for the Fox News Channel. Gingrich has signed the "Strong America Now" pledge committing to promoting Six Sigma methods to reduce government spending.[150]

Gingrich founded Advocates for Opioid Recovery together with former Rep. Patrick J. Kennedy and Van Jones, a former domestic policy adviser to President Barack Obama.[151]

Businesses

[edit]After leaving Congress in 1999, Gingrich started a number of for-profit companies:[152] Between 2001 and 2010, the companies he and his wife owned in full or part had revenues of almost $100 million.[153] As of 2015, Gingrich served as an advisor to the Canadian mining company Barrick Gold.[154]

According to financial disclosure forms released in July 2011, Gingrich and his wife had a net worth of at least $6.7 million in 2010, compared to a maximum net worth of $2.4 million in 2006. Most of the increase in his net worth was because of payments to him from his for-profit companies.[155]

Gingrich Group and the Center for Health Transformation

[edit]The Gingrich Group was organized in 1999 as a consulting company. Over time, its non-health clients were dropped, and it was renamed the Center for Health Transformation. The two companies had revenues of $55 million between 2001 and 2010.[156] The revenues came from more than 300 health-insurance companies and other clients, with membership costing as much as $200,000 per year in exchange for access to Gingrich and other perks.[153][157] In 2011, when Gingrich became a presidential candidate, he sold his interest in the business and said he would release the full list of his clients and the amounts he was paid, "to the extent we can".[156][158]

In April 2012, the Center for Health Transformation filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy, planning to liquidate its assets to meet debts of $1–$10 million.[159][160]

Between 2001 and 2010, Gingrich consulted for Freddie Mac, a government-sponsored secondary home mortgage company, which was concerned about new regulations under consideration by Congress. Regarding payments of $1.6 million for the consulting,[156] Gingrich said that "Freddie Mac paid Gingrich Group, which has a number of employees and a number of offices, a consulting fee, just like you would pay any other consulting firm."[161] In January 2012, he said that he could not make public his contract with Freddie Mac, even though the company gave permission, until his business partners in the Center for Health Transformation also agreed to that.[162]

Gingrich Productions

[edit]Gingrich Productions, which is headed by Gingrich's wife Callista Gingrich, was created in 2007. According to the company's website, in May 2011, it is "a performance and production company featuring the work of Newt and Callista Gingrich. Newt and Callista host and produce historical and public policy documentaries, write books, record audio books and voiceovers, produce photographic essays, and make television and radio appearances."[158]

Between 2008 and 2011, the company produced three films on religion,[163] one on energy, one on Ronald Reagan, and one on the threat of radical Islam. All were joint projects with the conservative group Citizens United.[164] In 2011, Newt and Callista appeared in A City Upon a Hill, on the subject of American exceptionalism.[165]

As of May 2011, the company had about five employees. In 2010, it paid Gingrich more than $2.4 million.[155]

Gingrich Communications

[edit]Gingrich Communications promoted Gingrich's public appearances, including his Fox News contract and his website, newt.org.[158] By 2011 Gingrich received as much as $60,000 for a speech, and did as many as 80 in a year.[153] One of Gingrich's nonprofit groups, Renewing American Leadership, which was founded in March 2009,[164] paid Gingrich Communications $220,000 over two years; the charity shared the names of its donors with Gingrich, who could use them for his for-profit companies.[166] Gingrich Communications, which employed 15 people at its largest, closed in 2011 when Gingrich began his presidential campaign.[158]

Other

[edit]- Celebrity Leaders is a booking agency that handled Gingrich's speaking engagements, as well as those other clients such as former Republican National Committee chair Michael Steele and former Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum.[152] Kathy Lubbers, the President and CEO of the agency,[167] who is Gingrich's daughter, owns the agency. Gingrich has shares in the agency, and was paid more than $70,000 by it in 2010.[168]

- FGH Publications handles the production of and royalties from fiction books co-authored by Gingrich.[158]

Political activity

[edit]Between 2005 and 2007, Gingrich expressed interest in running for the 2008 Republican presidential nomination.[169] On October 13, 2005, Gingrich suggested he was considering a run for president, saying, "There are circumstances where I will run", elaborating that those circumstances would be if no other candidate champions some of the platform ideas he advocates. On September 28, 2007, Gingrich announced that if his supporters pledged $30 million to his campaign by October 21, he would seek the nomination.[170]

However, insisting that he had "pretty strongly" considered running,[171] on September 29 spokesman Rick Tyler said that Gingrich would not seek the presidency in 2008 because he could not continue to serve as chairman of American Solutions if he did so.[172] Citing campaign finance law restrictions (the McCain-Feingold campaign law would have forced him to leave his American Solutions political organization if he declared his candidacy), Gingrich said, "I wasn't prepared to abandon American Solutions, even to explore whether a campaign was realistic."[173]

During the 2009 special election in New York's 23rd congressional district, Gingrich endorsed moderate Republican candidate Dede Scozzafava, rather than Conservative Party candidate Doug Hoffman, who had been endorsed by several nationally prominent Republicans.[174] He was heavily criticized for this endorsement, with conservatives questioning his candidacy for president in 2012[175][176] and even comparing him to Benedict Arnold.[177]

Prior to President Donald Trump leaving office in January 2021, Trump appointed Gingrich to the Defense Policy Board Advisory Committee of the Pentagon as part of a series of shakeups where prominent Trump loyalists replaced former members.[178] In February 2021, Biden-appointed Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin dismissed all appointments to the committee made by Trump, including Gingrich.[179]

2012 presidential run

[edit]

In late 2008, several political commentators, including Marc Ambinder in The Atlantic[180] and Robert Novak in The Washington Post,[181] identified Gingrich as a top presidential contender in the 2012 election, with Ambinder reporting that Gingrich was "already planting some seeds in Iowa, New Hampshire". A July 2010 poll conducted by Public Policy Polling indicated that Gingrich was the leading GOP contender for the Republican nomination with 23% of likely Republican voters saying they would vote for him.[182]

Describing his views as a possible candidate during an appearance on On the Record with Greta Van Susteren in March 2009, Gingrich said, "I am very sad that a number of Republicans do not understand that this country is sick of earmarks. [Americans] are sick of politicians taking care of themselves. They are sick of their money being spent in a way that is absolutely indefensible ... I think you're going to see a steady increase in the number of incumbents who have opponents because the American taxpayers are increasingly fed up."[183]

On March 3, 2011, Gingrich officially announced a website entitled "Newt Exploratory 2012" in lieu of a formal exploratory committee for exploration of a potential presidential run.[184] On May 11, 2011, Gingrich officially announced his intention to seek the GOP nomination in 2012.[185]

On June 9, 2011, a group of Gingrich's senior campaign aides left the campaign en masse, leading to doubts about the viability of his presidential run.[186] On June 21, 2011, two more senior aides left.[187][188]

In response, Gingrich stated that he had not quit the race for the Republican nomination, and pointed to his experience running for 5 years to win his seat in Congress, spending 16 years helping to build a Republican majority in the house and working for decades to build a Republican majority in Georgia.[189] Some commentators noted Gingrich's resilience throughout his career, in particular with regard to his presidential campaign.[190][191]

After then-front-runner Herman Cain was damaged by allegations of past sexual harassment, Gingrich gained support, and quickly became a contender in the race, especially after Cain suspended his campaign. By December 4, 2011, Gingrich was leading in the national polls.[192] However, after an abundance of negative ads run by his opponents throughout December, Gingrich's national polling lead had fallen to a tie with Mitt Romney.[193]

On January 3, 2012, Gingrich finished in fourth place in the Iowa Republican caucuses, far behind Rick Santorum, Romney, and Ron Paul.[194] On January 10, Gingrich finished in fifth place in the New Hampshire Republican primary, far behind Romney, Santorum, Jon Huntsman, and Paul.[195][196]

After the field narrowed with the withdrawal from the race of Huntsman and Rick Perry, Gingrich won the South Carolina Republican primary on January 21, obtaining about 40% of the vote, considerably ahead of Romney, Santorum and Paul.[197] This surprise victory allowed Gingrich to reemerge as the frontrunner once again heading into Florida.[198]

On January 31, 2012, Gingrich placed second in the Republican Florida primary, losing by a fifteen percentage point margin, 47% to 32%. Some factors that contributed to this outcome include two strong debate performances by Romney (which were typically Gingrich's strong suit), the wide margin by which the Gingrich campaign was outspent in television ads,[199] and a widely criticized proposal by Gingrich to have a permanent colony on the moon by 2020 to reinvigorate the American Space Program.[200]

It was later revealed Romney had hired a debate coach to help him perform better in the Florida debates.[201][202]

Gingrich did, however, significantly outvote Santorum and Paul. On February 4, 2012, Gingrich placed a distant second in the Nevada Republican caucuses with 21%, losing to Romney who received over 50% of the total votes cast.[203]

On February 7, 2012, Gingrich came in last place in the Minnesota Republican caucuses with about 10.7% of the vote. Santorum won the caucus, followed by Paul and Romney.[204][205]

On Super Tuesday Gingrich won his home state, Georgia, which has the most delegates, in "an otherwise dismal night for him". Santorum took Tennessee and Oklahoma, where Gingrich had previously performed well in the polls, though Gingrich managed a close third behind Romney.[206]

On April 4, the Rick Santorum campaign shifted its position and urged Gingrich to drop out of the race and support Santorum.[207]

On April 10, Santorum announced the suspension of his campaign.[208] Following this announcement, The Newt 2012 campaign used a new slogan referring to Gingrich as "the last conservative standing". Despite this, on April 19, Gingrich told Republicans in New York that he would work to help Romney win the general election if Romney secured the nomination.[209]

After a disappointing second place showing in the Delaware primary on April 24, and with a campaign debt in excess of $4 million,[210] Gingrich suspended his campaign and endorsed front-runner Mitt Romney on May 2, 2012,[211] on whose behalf he subsequently campaigned (i.e. stump speeches and television appearances).[212]

Gingrich later hosted a number of policy workshops at the GOP Convention in Tampa presented by the National Republican Committee called "Newt University".[213] He and his wife Calista addressed the convention on its final day with a Ronald Reagan-themed introduction.[214][215]

Because FEC regulations prevent campaigns from ceasing operations until they settle their debts, the Newt Gingrich campaign was never formally dissolved. In 2016, the campaign filed a proposal to shut down without paying back its outstanding debt to 114 businesses and consultants; the FEC rejected this proposal. By then, the campaign still owed $4.6 million in debt, with only $17,000 being raised by the campaign committee over the previous year.[216][217][218]

2016 election

[edit]Gingrich supported Donald Trump more quickly than many other establishment Republicans.[219] After having consulted for Trump's 2016 campaign, Gingrich encouraged his fellow Republicans to unify behind Trump, who had by then become the presumptive Republican presidential nominee.[220] Gingrich reportedly figured among Trump's final three choices to be his running mate;[221][222] the position ultimately went to Governor of Indiana Mike Pence.[223]

Following Trump's victory in the presidential election, speculation arose concerning Gingrich as a possible secretary of state, chief of staff or advisor.[224] Eventually, Gingrich announced that he would not be serving in the cabinet. He stated that he didn't have the interest in serving in any role related to the Trump administration, stressing that as a private citizen he would engage with individuals for "strategic planning" rather than job-seeking.[225]

In May 2017, he promoted a conspiracy theory that Hillary Clinton and the Democratic Party had Seth Rich, an employee for the Democratic National Committee, killed during the 2016 presidential race.[226]

Gingrich attended his wife's swearing-in as U.S. ambassador to the Holy See at the White House in October 2017.[227] According to journalist Robert Mickens, Newt Gingrich served as the de facto ambassador or the "shadow ambassador" while Callista Gingrich, as paraphrased by McKay Coppins of The Atlantic, "is generally viewed as the ceremonial face of the embassy".[228]

2020 election

[edit]While ballots were being counted during the 2020 election, Gingrich supported President Trump in his attempt to win re-election and called on him to stop the vote counts after unsubstantiated allegations of fraud emerged.[229] After the 2020 election, Gingrich made unsupported claims of election fraud and refused to acknowledge Joe Biden's victory.[230][231] He called for the arrest of poll workers in Pennsylvania following the election.[232][233][234]

2022 election

[edit]

In January 2022, Gingrich told Fox News presenter Maria Bartiromo that members of the House Select Committee investigating the January 6 attack on the Capitol faced a real risk of jail after Republicans take over Congress, accusing them of breaking laws without explaining which laws were broken:

"I think when you have a Republican Congress, this is all going to come crashing down, ... and the wolves are going to find out that they’re now sheep and they’re the ones who are in fact, I think, face a real risk of jail for the kinds of laws they’re breaking",[235]

which was interpreted by CNN and others as a threat.[235]

In July 2022, he was featured at an America First Policy Institute conference promoting a "Trump-inspired platform for the 2024 GOP presidential nominee".[236] As of August 2022, Gingrich was advising Kevin McCarthy and House Republicans for the 2022 midterm elections, according to journalist Dana Milbank.[237]

Political positions

[edit]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Gingrich is most widely identified with the 1994 Contract with America.[238] He is a founder of American Solutions for Winning the Future. More recently, Gingrich has advocated replacing the Environmental Protection Agency with a proposed "Environmental Solutions Agency".[239]

He favors an immigration border policy and a guest worker program.[240] In terms of energy policy, he has argued in favor of flex-fuel mandates for cars sold in the U.S. and promoted the use of ethanol generally.[241] In August 2021 Gingrich was said to have echoed the Great Replacement theory during a Fox News interview.[242]

Gingrich has taken a dim view of internationalism and the United Nations. He said in 2015, "after several years of looking at the UN, I can report to you that it is sufficiently corrupt and sufficiently inefficient that no reasonable person would put faith in it."[243]

In 2007, Gingrich authored a book, Rediscovering God in America.

Gingrich's later books take a large-scale policy focus, including Winning the Future, and the most recent, To Save America. Gingrich has identified education as "the number one factor in our future prosperity", and has partnered with Al Sharpton and Education Secretary Arne Duncan on education issues.[244] Although he previously opposed gay marriage, in December 2012, Gingrich suggested that Republicans should reconsider their opposition to it.[245]

In 2014, Gingrich sent a letter to Dr. John Koza of National Popular Vote, Inc. endorsing the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, under which participating states would award their Electoral College votes to the winner of the national popular vote of the United States.[246]

On July 14, 2016, Gingrich stated that he believes that Americans of Muslim backgrounds who believe in Sharia law should be deported,[247][248][249] and that visiting websites that promote the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant or Al-Qaeda should be a felony.[250] Some observers have questioned whether these views violate the free speech and free exercise of religion clauses of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.[251][252]

On July 21, 2016, Gingrich argued that members of NATO "ought to worry" about a U.S. commitment to their defense. He expanded, saying, "They ought to worry about commitment under any circumstances. Every president has been saying that the NATO countries do not pay their fair share". He also stated that, in the context of whether the United States would provide aid to Estonia (a NATO member) in the event of a Russian invasion, he "would think about it a great deal".[253]

According to Science magazine, Gingrich changed his view on climate change "from cautious skeptic in the late 1980s to believer in the late 2000s to skeptic again during the [2016] campaign."[254]

In January 2022, Gingrich characterized the House Select Committee on the January 6 Attack as "basically a lynch mob" that was violating laws and trampling on civil liberties, suggesting committee members might be jailed if Republicans took control of the House in that year's election.[255]

Personal life

[edit]Marriages and children

[edit]Jacqueline May "Jackie" Battley

[edit]Gingrich has been married three times. In 1962, he wed Jacqueline May "Jackie" Battley (February 21, 1936 – August 7, 2013), his former high school geometry teacher, when he was 19 years old and she was 26.[256][257] They had two daughters: Kathy, who is president of Gingrich Communications,[258] and Jackie Sue, who is an author, conservative columnist and political commentator.[259][260]

Throughout his congressional campaign in 1974, Gingrich was having an affair with a young volunteer. An aide who worked with Gingrich throughout the 1970s stated that "it was common knowledge that Newt was involved with other women during his marriage to Jackie."[261][262] In the spring of 1980, he filed for divorce from Jackie after beginning an affair with Marianne Ginther.[263][264] Jackie later said in 1984 that the divorce was a "complete surprise" to her.[265]

In September 1980, according to friends who knew them both, Newt visited Jackie in the hospital the day after she had undergone surgery to treat her uterine cancer; once there, Newt began talking about the terms of their divorce, at which point Jackie threw him out of the room.[266][265] Gingrich disputed that account.[267] Although Newt's presidential campaign staff continued to insist in 2011 that Jackie had requested the divorce, court documents from Carroll County, Georgia, indicated that she had in fact asked a judge to block the process, stating that although "she has adequate and ample grounds for divorce ... she does not desire one at this time [and] does not admit that this marriage is irretrievably broken."[268]

According to L. H. Carter, Gingrich's campaign treasurer, Gingrich said of Jackie: "She's not young enough or pretty enough to be the wife of the President. And besides, she has cancer."[269][270] Newt has denied saying it.[266] Following the divorce, Jackie had to raise money from friends in her congregation to help her and the children make ends meet; she later filed a petition in court stating that Newt had failed to properly provide for his family.[262] Newt submitted a financial statement to the judge, which showed that he had been "providing only $400 a month, plus $40 in allowances for his daughters. He claimed not to be able to afford any more. But in citing his own expenses, he listed $400 just for 'Food / dry cleaning, etc.'—for one person."[262] In 1981, a judge ordered him to provide considerably more; in 1993, Jackie stated in court that Newt had failed to obey the 1981 order "from the day it was issued."[269] Jackie, a deacon and volunteer in the First Baptist Church of Carrollton, Georgia, died in 2013 in Atlanta at the age of 77.[271]

Marianne Ginther

[edit]In 1981, six months after his divorce from Jackie was final, Gingrich wed Marianne Ginther.[272][273][274][275] Marianne helped control their finances to get them out of debt.[276] She did not, however, want to have the public life of a politician's wife.[261] His daughter Kathy described the marriage as "difficult".[277]

Callista Bisek

[edit]

In 1993, while still married to Marianne, Gingrich began an affair with House of Representatives staffer Callista Bisek, more than two decades his junior.[278] Gingrich was having this affair even as he led the impeachment of Bill Clinton for perjury related to Clinton's own extramarital affair.[279][128] Gingrich filed for divorce from Marianne in 1999, a few months after she had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.[280] The marriage produced no children. On January 19, 2012, Marianne alleged in an interview on ABC's Nightline that she had declined to accept Newt's suggestion of an open marriage.[281] Newt disputed the account.[282]

In August 2000, Gingrich married Callista Bisek four months after his divorce from Marianne was finalized.[283] He and Callista live in McLean, Virginia.[284]

In a 2011 interview with David Brody of the Christian Broadcasting Network, Gingrich addressed his past infidelities by saying, "There's no question at times in my life, partially driven by how passionately I felt about this country, that I worked too hard and things happened in my life that were not appropriate."[274][275] In December 2011, after the group Iowans for Christian Leaders in Government requested that he sign their so-called "Marriage Vow", Gingrich sent a lengthy written response. It included his pledge to "uphold personal fidelity to my spouse".[285]

Religion

[edit]

Raised as a Lutheran,[286] Gingrich was a Southern Baptist in graduate school. He converted to Catholicism, the faith of his third wife Callista Bisek, on March 29, 2009.[287][288] He said: "over the course of several years, I gradually became Catholic and then decided one day to accept the faith I had already come to embrace". He decided to officially become a Catholic when he saw Pope Benedict XVI, during the Pope's visit to the United States in 2008: "Catching a glimpse of Pope Benedict that day, I was struck by the happiness and peacefulness he exuded. The joyful and radiating presence of the Holy Father was a moment of confirmation about the many things I had been thinking and experiencing for several years."[289] At a 2011 appearance in Columbus, Ohio, he said, "In America, religious belief is being challenged by a cultural elite trying to create a secularized America, in which God is driven out of public life."[163]

The Catholic Church recognizes his third marriage as a valid marriage, based on a declaration of nullity granted for his second marriage and the passing of his wife from his first.[290][291][292]

Other interests

[edit]

Gingrich has expressed a deep interest in animals.[293][294] Gingrich's first engagement in civic affairs was speaking to the city council in his native Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, as to why the city should establish its own zoo.[295] He authored the introduction to America's Best Zoos and claims to have visited more than 100.[296]

Gingrich has shown enthusiasm towards dinosaurs. The New Yorker said of his 1995 book To Renew America: "Charmingly, he has retained his enthusiasm for the extinct giants into middle age. In addition to including breakthroughs in dinosaur research on his list of futuristic wonders, he specified 'people interested in dinosaurs' as a prime example of those who might benefit from his education proposals."[297]

Space exploration has been an additional interest of Gingrich since a fascination with the United States/Soviet Union Space Race started in his teenage years.[298] Gingrich wants the U.S. to pursue new achievements in space, including sustaining civilizations beyond Earth,[299] but advocates relying more on the private sector and less on the publicly funded NASA to drive progress.[300] Since 2010, he has served on the National Space Society Board of Governors.[301]

During the 2012 election campaign, Artinfo noted that Gingrich has expressed appreciation for the work of two American painters. He has described James H. Cromartie's painting of the U.S. Capitol as "an exceptional and truly beautiful work of art"; in Norman Rockwell's work, he saw the embodiment of an America circa 1965, at odds with the prevailing sentiment of the modern day "cultural elites".[302]

CNN announced on June 26, 2013, that Gingrich would join a new version of Crossfire re-launching in fall 2013, with panelists S. E. Cupp, Stephanie Cutter, and Van Jones.[303] Gingrich represented the right on the revamped debate program.[303] The show was cancelled the following year.[304]

Books and film

[edit]Nonfiction

[edit]- The Government's Role in Solving Societal Problems, Associated Faculty Press, January 1982, ISBN 978-0-86733-026-7

- Window of Opportunity, Tom Doherty Associates, December 1985, ISBN 978-0-312-93923-6

- Contract with America (co-editor). Times Books, December 1994, ISBN 978-0-8129-2586-9

- Restoring the Dream, Times Books, May 1995, ISBN 978-0-8129-2666-8

- Quotations from Speaker Newt. Workman Publishing Company, July 1995, ISBN 978-0-7611-0092-8

- To Renew America, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, July 1996, ISBN 978-0-06-109539-9

- Lessons Learned The Hard Way. HarperCollins, May 1998, ISBN 978-0-06-019106-1

- Presidential Determination Regarding Certification of the Thirty-Two Major Illicit Narcotics Producing and Transit Countries, DIANE Publishing Company, September 1999, ISBN 978-0-7881-3186-8

- Saving Lives and Saving Money, Alexis de Tocqueville Institution, April 2003, ISBN 978-0-9705485-4-2

- Winning the Future, Regnery Publishing, January 2005, ISBN 978-0-89526-042-0

- Rediscovering God in America: Reflections on the Role of Faith in Our Nation's History and Future, Integrity Publishers, October 2006, ISBN 978-1-59145-482-3

- The Art of Transformation, with Nancy Desmond. CHT Press, November 2006, ISBN 978-1-933966-00-7

- A Contract with the Earth, with Terry L. Maple. Johns Hopkins University Press, October 2007, ISBN 978-0-8018-8780-2

- Real Change: From the World That Fails to the World That Works, Regnery Publishing, January 2008. ISBN 978-1-59698-053-2

- Drill Here, Drill Now, Pay Less: A Handbook for Slashing Gas Prices and Solving Our Energy Crisis, with Vince Haley. Regnery Publishing, September 2008, ISBN 978-1-59698-576-6

- 5 Principles for a Successful Life: From Our Family to Yours, with Jackie Gingrich Cushman, Crown Publishing Group, May 2009, ISBN 978-0-307-46232-9

- To Save America: Stopping Obama's Secular-Socialist Machine, with Joe DeSantis, Regnery Publishing, May 2010, ISBN 978-1-59698-596-4

- Ronald Reagan: Rendezvous with Destiny, Dunham Books, January 2011, ISBN 978-1-45074-672-4

- A Nation Like No Other: Why American Exceptionalism Matters, Regnery Publishing, June 2011, ISBN 978-1-59698-271-0

- Breakout: Pioneers of the Future, Prison Guards of the Past, and the Epic Battle That Will Decide America's Fate, Regnery Publishing, November 2013, ISBN 978-1-62157-021-9

- Understanding Trump, Center Street, June 2017, ISBN 978-1-4789-2308-4

- Trump's America: The Truth about Our Nation's Great Comeback, Center Street, June 2018, ISBN 978-1-5460-7706-0

- Trump vs China: America's Greatest Challenge, Center Street, October 2019, ISBN 978-1-5460-8507-2

- Trump and the American Future: Solving the Great Problems of Our Time, Center Street, June 2020, ISBN 978-1-5460-8504-1

- Beyond Biden: Rebuilding the America We Love, Center Street, November 2021, ISBN 978-1-5460-0025-9

- Defeating Big Government Socialism, Center Street, July 2022, ISBN 978-1-5460-0322-9

- March to the Majority: The Real Story of the Republican Revolution, Center Street, June 2023, ISBN 978-1-5460-0484-4

Fiction

[edit]Gingrich co-wrote the following alternate history novels and series of novels with William R. Forstchen.

- 1945, Baen Books, August 1995; ISBN 978-0-671-87739-2

- Civil War series

- Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War, Thomas Dunne Books, June 2003 ISBN 978-0-312-30935-0

- Grant Comes East, Thomas Dunne Books, June 2004 ISBN 978-0-312-30937-4

- Never Call Retreat: Lee and Grant: The Final Victory, Thomas Dunne Books, June 2005 ISBN 978-0-312-34298-2

- The Battle of the Crater: A Novel, Thomas Dunne Books, November 2011 ISBN 978-0-312-60710-4

- Pacific War series

- Pearl Harbor: A Novel of December 8, Thomas Dunne Books, May 2007 ISBN 978-0-312-36350-5

- Days of Infamy, Thomas Dunne Books, April 2008 ISBN 978-0-312-36351-2

- Revolutionary War series

- To Try Men's Souls: A Novel of George Washington and the Fight for American Freedom, Thomas Dunne Books, October 2009, ISBN 978-0-312-59106-9

- Valley Forge: George Washington and the Crucible of Victory, Thomas Dunne Books, November 2010, ISBN 978-0-312-59107-6

- Victory at Yorktown, Thomas Dunne Books, November 2012, ISBN 978-0-312-60707-4

- Brooke Grant series

- Duplicity: A Novel, Center Street Press, October 13, 2015, co-author Pete Earley, ISBN 978-1455530427

- Treason: A Novel, Center Street Press, October 11, 2016, co-author Pete Earley, ISBN 978-1455530441

- Vengeance: A Novel, Center Street Press, October 10, 2017, co-author Pete Earley, ISBN 978-1478923046

- Mayberry and Garrett series

- Collusion: A Novel, Broadside Books, April 30, 2019, co-author Pete Earley, ISBN 978-0062859983

- Shakedown: A Novel, Broadside Books, March 24, 2020, co-author Pete Earley, ISBN 978-0062860194

Films

[edit]- Ronald Reagan: Rendezvous with Destiny, Gingrich Productions, 2009[305]

- Nine Days That Changed the World, Gingrich Productions, 2010[306]

See also

[edit]- List of federal political scandals in the United States

- List of federal political sex scandals in the United States

- List of United States representatives expelled, censured, or reprimanded

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ While the Republican party won the most seats in 1916, adjacent to the re-election of Wilson, Democratic Speaker Champ Clark managed to retain his position due to an alliance with Progressive and Socialist representatives.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Patrick, John J.; Pious, Richard M.; Ritchie, Donald A. (July 4, 2001). The Oxford Guide to the United States Government. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 264. ISBN 9780195142730.

- ^ "Biographical Directory of the United States Congress: Gingrich, Newton Leroy". bioguide.congress.gov/. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "Gingrich's Path From 'Flameout' To D.C. Entrepreneur". NPR. December 8, 2011. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ "Did Gingrich leave speakership". PolitiFact. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Mason, Lililana (2018). Uncivil Agreement. University of Chicago Press. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Rosenfeld, Sam (2017). The Polarizers. University of Chicago Press. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ a b c Theriault, Sean M. (May 23, 2013). The Gingrich Senators: The Roots of Partisan Warfare in Congress. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199307456. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ a b Harris, Douglas B. (2013). "Let's Play Hardball". Politics to the Extreme. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 93–115. doi:10.1057/9781137312761_5. ISBN 9781137361424.

- ^ a b Zelizer, Julian (2020). Burning Down the House: Newt Gingrich, the Fall of a Speaker, and the Rise of the New Republican Party. Penguin.

- ^ "Gingrich tops polls in Iowa, South Carolina, North Carolina and Colorado". PoconoRecord.com. December 6, 2011. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ^ The Unprecedented 2016 Presidential Election | Rachel Bitecofer | Palgrave Macmillan. p. 146. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ Mastrangelo, Dominick (December 22, 2020). "Gingrich won't accept Biden as president, says Democrats, Republicans 'live in alternative worlds'". The Hill. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Newt Gingrich Parents and Grandparents". 1989.Republican-Candidates.org. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- ^ Rourke, Mary (September 25, 2003). "Kathleen Gingrich, 77; Mother of House Speaker Made News". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- ^ "The Long March of Newt Gingrich". Frontline. PBS. January 16, 1996. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ^ "Biography of Newton Gingrich". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. 2007. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ^ "Immigration Divides Republican Opinion". Contra Costa Times. November 24, 1997. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ^ Boeri, David (March 18, 2011). "Newt Gingrich Arrives In N.H., In Search Of Elephants". WBUR-FM. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ a b "Robert Gingrich; Retired Army Officer, Father of House Speaker". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. November 21, 1996. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- ^ a b "A Newt Chronology". PBS.org. Archived from the original on June 7, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ^ Zeleny, Jeff. "Newt Gingrich – Election 2012". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ^ Gingrich, Newt; Gingrich Cushman, Jackie (May 12, 2009). 5 Principles for a Successful Life: From Our Family to Yours. Crown Publishing Group. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-307-46232-9. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ "Newt Gingrich". Answers.com. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ Norman, Laurence (October 18, 2011). "Newt Gingrich's Brussels Digs". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- ^ Gingrich, Newton Leroy (1971). Belgian Education Policy In The Congo, 1945-1960 (Ph.D. thesis). Tulane University. OCLC 319989994. ProQuest 302627314.

- ^ Boyer, Peter J. (July 1989). "Good Newt, Bad Newt". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c Williamson, Elizabeth (January 18, 2012). "Gingrich's college records show a professor hatching big plans". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 30, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ Kilgore, Ed (March 3, 2011). "Chameleon". The New Republic. Archived from the original on March 6, 2011. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- ^ "Race details for 1974 election [in 6th District]". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ "John James Flynt". OurCampaigns. bio page. Archived from the original on June 11, 2016.

- ^ "A Newt Chronology | The Long March Of Newt Gingrich | FRONTLINE | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ "1976 Presidential General Election Results - Georgia". Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ "Race details for 1976 House election". Ourcampaigns.com. Archived from the original on January 8, 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- ^ "Shepard, Virginia". Our Campaigns. June 23, 2007. Archived from the original on January 21, 2012. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ "Shapard, Virginia". GGDP Library Special Collections. Georgia State University Library (library.gsu.edu). January 26, 1988. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved September 5, 2010.

- ^ Gingrich was also elected to 4 terms from a new 6th District (after redistricting following the 1990 census), as described in the next section.

- ^ MacGillis, Alec (December 14, 2011). "The Forgotten Campaign". The New Republic. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (March 2, 2021). "Georgia's center of political gravity shifting toward Atlanta". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved May 25, 2021.