25I-NBOMe

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Buccal (sublabial), sublingual, insufflated, inhalation, intravenous, intramuscular, rectal |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H22INO3 |

| Molar mass | 427.28 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

25I-NBOMe (2C-I-NBOMe, Cimbi-5) is a psychedelic drug and derivative of the substituted phenethylamine psychedelic 2C-I. It was discovered in 2003 by chemist Ralf Heim at the Free University of Berlin, who published his findings in his PhD dissertation.[1] The compound was subsequently investigated by a team at Purdue University led by David Nichols.[2]

The carbon-11 labelled version of 25I-NBOMe, [11C]Cimbi-5, was synthesized and validated as a radiotracer for positron emission tomography (PET) in Copenhagen.[3][4] Being the first 5-HT2A receptor full agonist PET radioligand, [11C]Cimbi-5 shows promise as a more functional marker of these receptors.[citation needed]

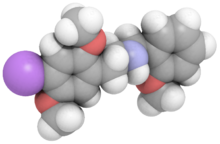

Chemistry and structure

Like other 2C-X-NBOMe molecules, 25I-NBOMe is a derivative of the 2C family of phenethylamines described by Alexander Shulgin in his book PiHKAL.[5][6] Specifically, 25I-NBOMe is an N-benzyl derivative of the phenethylamine molecule 2C-I, formed by adding a 2-methoxybenzyl (MeOB) onto the nitrogen (N) of the phenethylamine backbone. This substitution significantly increases the potency of the molecule.[5]

Synthesis

25I-NBOMe is usually synthesised from 2C-I and 2-methoxybenzaldehyde, in a reductive alkylation. It can be done stepwise by first making the imine and then reducing the formed imine with sodium borohydride, or by direct reaction with sodium triacetoxyborohydride.[1]

Pharmacology

| Receptor | Ki (nM) | ± |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT2A | 0.044 | |

| 5-HT2C | 2 | |

| 5-HT6 | 73 | 12 |

| μ-opioid | 82 | 14 |

| H1 | 189 | 35 |

| 5-HT2B | 231 | 73 |

| κ-opioid | 288 | 50 |

25I-NBOMe acts as a highly potent full agonist for the human 5-HT2A receptor,[7][9] with a Ki of 0.044 nM, making it some sixteen times the potency of 2C-I itself, and a radiolabelled form of 25I-NBOMe can be used for mapping the distribution of 5-HT2A receptors in the brain.[8] It is one of the only full agonists of the human 5-HT2A in existence. In vitro tests showed this compound acted as an agonist. Head twitch studies in mice have confirmed that 25I-NBOMe activates the 5-HT2A receptor in vivo, and demonstrated that 25I-NBOMe is approximately 14-fold more potent than 2C-I.[10] While the in vitro studies showed that N-benzyl derivatives of 2C-I were significantly increased in potency compared to 2C-I, the N-benzyl derivatives of DOI were inactive.[11]

Ki values of the following targets were greater than 500 nM: 5-HT1A, D3, H2, 5-HT1D, α1A adrenergic, δ opioid, serotonin uptake transporter, 5-HT5A, 5-HT1B, D2, 5-HT7, D1, 5-HT3, 5-HT1E, D5, muscarinic M1-M5, H3, and the dopamine uptake transporter.[8]

A forensic standard of 25I-NBOMe is available, and the compound has been posted on the Forendex website of potential drugs of abuse.[12]

25I-NBOMe induces a head-twitch response in mice which is blocked completely by a selective 5-HT2A antagonist, suggesting its psychedelic effects are mediated by 5-HT2A.[13]

Recreational use

Although 25I-NBOMe was discovered in 2003, it did not emerge as a common recreational drug until 2010, when it was first sold by vendors specialising in the supply of research chemicals.[citation needed] In a slang context, the name of the compound is often shortened to “25I”. According to a 2014 survery, 25I-NBOMe is the most frequently used of the NBOMe series.[14] Case reports of 25I-NBOMe intoxication, with and without analytic confirmation of the drug in the body, are increasing in the medical literature.[6]

25I-NBOMe is inactive orally, and the most common methods of administration are sublingual, buccal, and nasal.[14] For sublingual and buccal administration, 25I-NBOMe is applied to sheets of blotter paper — usually perforated with a uniform grid — of which small portions (tabs) are placed under the tongue or in the buccal space of the mouth, where the drug can be readily absorbed via mucous membranes.[5] There are reports of intravenous injection of 25I-NBOMe solution and smoking the drug in powdered form.[15][16]

Due to its potency, small quantities of 25I-NBOMe can provide a large numbers of doses. Vendors may import 25I-NBOMe in bulk and resell individual doses for considerable profit.[5]

Because blotter paper is also a common distribution medium for LSD, 25I-NBOMe blotters are sometimes misrepresented as, and mistaken for, LSD blotters.[17] It is challenging to differentiate the two using sensory techniques but reagent testing (particularly ehrlich's reagent) can be used to easily differentiate ergolines from 25-I NBOMe by a colour change.[18]

Dosage

25I-NBOMe is potent, being active in sub-milligram doses. A common dose of the hydrochloride salt is 600–1,200 µg. The UK Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs states that a common dose is between 50 and 100 µg,[5] although other sources indicate that these figures are incorrect; Erowid tentatively suggests that the threshold dosage for humans is 50–250 µg, with a light dose between 200–600 µg, a common dose at 500–800 µg, and a strong dose at 700–1500 µg.[19] At this level of potency, it is not possible to accurately measure a single dose of the powder without an analytical balance, and attempting to do so may put the user at risk of overdose.[5]

Effects

25I-NBOMe effects usually last 6–10 hours if taken sublingually or buccally.[16] When it is insufflated, effects usually last 4–6 hours.[16] Effects can however last significantly longer depending on dosage; durations longer than 12 hours have been reported.

25I-NBOMe can also be vaporized and inhaled, this may cause significantly quicker effects and shorter duration as is expected from that route of administration. This route of administration is however not recommended, unless when using precise liquid measurement, due to the difficulties of measuring and handling substances active in the microgram range.

25I-NBOMe has similar effects to LSD, though users report more negative effects while high and more risk of harm following use as compared to other classic psychedelics.[14]

Case reports of seven British males who presented to an emergency room following analytically confirmed 25I-NBOMe intoxication suggest the following potential adverse effects: tachycardia (n = 7), hypertension (4), agitation (6), aggression, visual and auditory hallucinations (6), seizures (3), hyperpyrexia (3), clonus (2), elevated white cell count (2), elevated creatine kinase (7), metabolic acidosis (3), and acute kidney injury (1).[15]

Desired

|

Neutral

|

Undesired(Includes negative side effects arising from overdose; likelihood of negative side effects increases with dose)

|

Tolerance

Users of 25I-NBOMe have reported that it causes physiological tolerance that may last for around 2-4 weeks. This tolerance is described as diminishing the efficacy of subsequent doses of 25I-NBOMe, as well as interfering with the efficacy of other phenethylamines.[20] This kind of temporary, rapidly-developed tolerance is a typical side effect of a number of other drugs of the phenethylamine class, such as MDMA.This tolerance will also affect the tolerance one has to a variety of other drugs.

Toxicity and harm potential

Recreational use of 25I-NBOME carries significant risk of both pharmacological and behavioral toxicity.[6][15] 25I-NBOMe is a relatively new substance, and little is known about its pharmacological risks or its interaction with other substances. The LD50 has not yet been determined.[21] It is a highly potent serotonin agonist and, due to its psychedelic effects and ambiguous legal status, a designer drug with reports of recreational use beginning in 2010. Reports of deaths and significant injuries have been attributed to the use of 25I-NBOMe, prompting some governments to control its possession, production, and sale. The harm-reduction website Erowid states that 25I-NBOMe is extremely potent and should not be snorted as this method of administration “appears to have led to several deaths in the past year.”[17] Several non-fatal overdoses requiring prolonged hospitalization have also been reported.[5][6][15]

The BBC carried a report in 2014 of a 26-year-old male who took "N-bomb" and drank alcohol the previous year at a party in Cornwall, and was found by passers-by having a seizure.

As of May 2013, 25I-NBOMe has reportedly led to five overdose deaths in the United States.[22] In June 2012, two teens in Grand Forks, North Dakota and East Grand Forks, Minnesota fatally overdosed on a substance that was allegedly 25I-NBOMe, resulting in lengthy sentences for two of the parties involved and a Federal indictment against the Texas based online vendor.[23] A 21-year-old man from Little Rock, Arkansas died in October 2012 after taking a liquid drop of the drug nasally at a music festival. He was reported to have consumed caffeinated alcoholic beverages for “several hours” beforehand. It is unclear what other drugs he may have consumed, as autopsies generally do not test for the presence of research chemicals.[24][25] In January 2013, an 18 year-old in Scottsdale, Arizona, died after consuming 25I-NBOMe sold as LSD; a toxicology screening found no other drugs in the person's system. The drug is the suspected cause of death in another Scottsdale, Arizona, incident in April 2013.[5]

25I-NBOMe has been implicated in multiple deaths in Australia.[5] In March 2012, a man in Australia died from injuries sustained by running into trees and power poles while intoxicated by 25I-NBOMe.[26] A Sydney teenager jumped to his death on June 5, 2013. He reportedly jumped off a balcony thinking he could fly.[27]

Legal status

Australia

25I-NBOMe was explicitly scheduled in Queensland (Australian) drug law in April 2012, and in New South Wales in October 2013, as were some related compounds such as 25B-NBOMe. The Australian federal government has no specific legislation concerning any of the N-benzyl phenethylamines.[citation needed]

Israel

Israel banned 25I-NBOMe in 2013.[28]

Russia

Russia was the first country to pass specific regulations on the NBOME series. All drugs in the NBOMe series, including 25I-NBOMe, became illegal in Russia in October 2011.[28]

Sweden

25I-NBOMe was classified as a Schedule I substance in publication LVFS 2013:15 by the Medical Products Agency.[29] The classification took effect on 1 Aug, 2013.

United Kingdom

N-benzylated phenethylamines such as 25I-NBOMe were initially unaffected by the legal status of phenethylamine-class drugs.[5] The British government issued a temporary class drug order on a list of emerging recreational drugs, including 25I-NBOMe, on 4 June 2013. The order, which took effect on 10 June 2013 and will last for up to twelve months, prohibits the production, import and sale of “the NBOMe and Benzofury groups of substances”.[30]

The UK Home Office announced that 25I-NBOMe would be made a class A drug on 10th June 2014 alongside every other N-benzyl phenethylamine.[31]

United States

On Nov 15, 2013, the DEA added 25I-NBOMe (and 25C-, and 25B-NBOMe) to Schedule I using their emergency scheduling powers, making those NBOMe compounds "temporarily" in Schedule I for 2 years.[32]

Romania

In 2011, Romania banned all psychoactive substances,[33] no matter what they really are.[34]

See also

- 2CBCB-NBOMe (NBOMe-TCB-2)

- 2CBFly-NBOMe (NBOMe-2CB-Fly)

- 25C-NBOMe (NBOMe-2CC)

- 25B-NBOMe (NBOMe-2CB)

- 25I-NBMD (NBMD-2CI)

- 25I-NBOH (NBOH-2CI)

- 25I-NBF (NBF-2CI)

- 5-MeO-NBpBrT

References

- ^ a b Ralf Heim PhD. (2010-02-28). "Synthese und Pharmakologie potenter 5-HT2A-Rezeptoragonisten mit N-2-Methoxybenzyl-Partialstruktur. Entwicklung eines neuen Struktur-Wirkungskonzepts" (in German). diss.fu-berlin.de. Retrieved 2013-05-10.

- ^ Michael Robert Braden PhD. (2007). "Towards a biophysical understanding of hallucinogen action". Purdue University. Retrieved 2012-08-08.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.2967/jnumed.109.074021, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.2967/jnumed.109.074021instead. - ^ Hansen, M. (2011).Design and Synthesis of Selective Serotonin Receptor Agonists for Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of the Brain. PhD Thesis, University of Copenhagen.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Iversen, Les (May 29, 2013). "Temporary Class Drug Order Report on 5-6APB and NBOMe compounds" (PDF). Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Gov.Uk. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d Rose, S. Rutherford; Justin L. Polkis and Alphone Polkis (March 2013). "A case of 25I-NBOMe (25-I) intoxication: a new potent 5-HT2A agonist designer drug". Clinical Toxicology. 51 (3): 174–177. doi:10.3109/15563650.2013.772191. PMID 23473462. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/s00259-010-1686-8, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/s00259-010-1686-8instead. - ^ a b c Nichols DE, Frescas SP, Chemel BR, Rehder KS, Zhong D, Lewin AH (June 2008). "High Specific Activity Tritium-Labeled N-(2-methoxybenzyl)-2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenethylamine (INBMeO): A High Affinity 5-HT2A Receptor-Selective Agonist Radioligand". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (11): 6116–23. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.04.050. PMC 2719953. PMID 18468904.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Silva ME, Heim R, Strasser A, Elz S, Dove S (January 2011). "Theoretical studies on the interaction of partial agonists with the 5-HT(2A) receptor". Journal of Computer-aided Molecular Design. 25 (1): 51–66. doi:10.1007/s10822-010-9400-2. PMID 21088982.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Halberstadt AL, Geyer MA (2013). "Effects of the hallucinogen 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenethylamine (2C-I) and superpotent N-benzyl derivatives on the head twitch response". Neuropharmacology. in press: 200–207. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.08.025. PMID 24012658.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1124/mol.106.028720, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1124/mol.106.028720instead. - ^ Southern Association of Forensic Scientists http://forendex.southernforensic.org/index.php/detail/index/1145

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.08.025, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.08.025instead. - ^ a b c Lawn, Will; Monica Barrat, Martin Wiliams, Abi Horne, Adam Winstock (February 24, 2014). "The NBOMe hallucinogenic drug series: Patterns of use, characteristics of users and self-reported effects in a large international sample". Journal of Psychopharmocology. doi:10.1177/0269881114523866.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Hill, Simon L.; Tom Doris, Shiv Gurung, Stephen Katebe, Alexander Lomas,Mick Dunn, Peter Blain, Simon H. L. Thomas (June 4, 2013). "Severe clinical toxicity associated with analytically confirmed recreational use of 25I–NBOMe: case series". Clinical Toxicology: 1–6. doi:10.3109/15563650.2013.802795. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "2C-I-NBOMe (25I) Effects". Erowid.org. Retrieved 2012-10-07Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b "25I-NBOMe". Erowid. April 26, 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ "LSD Identification Guide". Bunk Police. 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ "2C-I-NBOMe (25I) Dose". Erowid.org. Retrieved 2012-10-07Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ http://www.disregardeverythingisay.com/post/49302181054/25i-nbome-broken-down-and-described

- ^ "Fatalities / Deaths". Erowid. April 26, 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ Hastings, Deborah (May 6, 2013). "New drug N-bomb hits the street, terrifying parents, troubling cops". New York Daily News. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ "Breaking Bad: Digital Drug Sales, Analog Drug Deaths. Craig Malisow, Houston Press, March 13, 2013". houstonpress.com. 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- ^ "21-year-old dies after one drop of new synthetic drug at Voodoo Fest. Naomi Martin, NOLA, November 1, 2012". NOLA.com. 2012-11-01. Retrieved 2012-11-02.

- ^ http://www.erowid.org/chemicals/2ci_nbome/2ci_nbome_death.shtml

- ^ Rice, Steven (September 12, 2012). "New hallucinogenic drug 25B-NBOMe and 25I-NBOMe led to South Australian man's bizarre death". Adelaide Now. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ CUNEO, CLEMENTINE. "Henry Kwan jumps to his death in a synthetic psychosis". Daily Telegraph, Sydney, Australia. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ a b "2C-I-NBOMe Legal Status". Erowid.org. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ^ http://www.lakemedelsverket.se/upload/lvfs/LVFS_2013-15.pdf

- ^ "'NBOMe' and 'Benzofury' banned". gov.uk. 2013-06-04. Retrieved 2013-06-10Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ UK Home Office (2014-03-05). "The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Ketamine etc.) (Amendment) Order 2014". UK Government. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- ^ http://www.justice.gov/dea/divisions/hq/2013/hq111513.shtml

- ^ http://drogriporter.hu/node/2211

- ^ http://www.dreptonline.ro/legislatie/legea_194_2011_combaterea_operatiunilor_produse_susceptibile_efecte_psihoactive.php