Tetrahydrocannabinol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Dronabinol |

| License data |

|

| Dependence liability | 8–10% (Relatively low risk of tolerance)[1] |

| Routes of administration | Orally, local/topical, transdermal sublingual, smoked (or vaporized) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 10–35% (inhalation), 6–20% (oral)[3] |

| Protein binding | 97–99%[3][4][5] |

| Metabolism | Mostly hepatic by CYP2C[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 1.6–59 h,[3] 25–36 h (orally administered dronabinol) |

| Excretion | 65–80% (faeces), 20–35% (urine) as acid metabolites[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.153.676 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H30O2 |

| Molar mass | 314.469 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Specific rotation | -152° (ethanol) |

| Boiling point | 157 °C (315 °F) [6] |

| Solubility in water | 0.0028[7] (23 °C) mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

| | |

Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), or more precisely its main isomer (−)-trans-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol ( (6aR,10aR)-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol), is the principal psychoactive constituent (or cannabinoid) of the cannabis plant. First isolated in 1964, in its pure form, by Israeli scientists Raphael Mechoulam and Yechiel Gaoni at the Weizmann Institute of Science,[8][9][10] it is a glassy solid when cold, and becomes viscous and sticky if warmed. A pharmaceutical formulation of (−)-trans-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, known by its INN dronabinol, is available by prescription in the U.S. and Canada under the brand name Marinol. An aromatic terpenoid, THC has a very low solubility in water, but good solubility in most organic solvents, specifically lipids and alcohols.[7]

Like most pharmacologically-active secondary metabolites of plants, THC in cannabis is assumed to be involved in self-defense, perhaps against herbivores.[11] THC also possesses high UV-B (280–315 nm) absorption properties, which, it has been speculated, could protect the plant from harmful UV radiation exposure.[12][13][14]

Tetrahydrocannabinol with double bond isomers and their stereoisomers is one of only three cannabinoids scheduled by Convention on Psychotropic Substances (the other two are dimethylheptylpyran and parahexyl). Cannabis as a plant is scheduled by the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (Schedule I and IV).

Pharmacology

The pharmacological actions of THC result from its partial agonist activity at the cannabinoid receptor CB1 (Ki=10nM[15]), located mainly in the central nervous system, and the CB2 receptor (Ki=24nM[15]), mainly expressed in cells of the immune system.[16] The psychoactive effects of THC are primarily mediated by its activation of CB1G-protein coupled receptors, which result in a decrease in the concentration of the second messenger molecule cAMP through inhibition of adenylate cyclase.[17]

The presence of these specialized cannabinoid receptors in the brain led researchers to the discovery of endocannabinoids, such as anandamide and 2-arachidonoyl glyceride (2-AG). THC targets receptors in a manner far less selective than endocannabinoid molecules released during retrograde signaling, as the drug has a relatively low cannabinoid receptor efficacy and affinity. In populations of low cannabinoid receptor density, THC may act to antagonize endogenous agonists that possess greater receptor efficacy.[18] THC is a lipophilic molecule[19] and may bind non-specifically to a variety of receptors in the brain and body, such as adipose tissue (fat).[20][21]

Several studies have suggested that THC also has an anticholinesterase action[22][23] which may implicate it as a potential treatment for Alzheimer's and Myasthenia Gravis.

Interactions

The effects of the drug can be reduced by the CB1 receptor inverse agonist rimonabant (SR141716A) as well as opioid receptor antagonists (opioid blockers) naloxone and naloxonazine.[24][25] The α7 nicotinic receptor antagonist methyllycaconitine can block self-administration of THC in rates comparable to the effects of varenicline on nicotine administration.[26]

Cannabidiol, the second most abundant cannabinoid found in cannabis, is an indirect antagonist against cannabinoid agonists; thus reducing the effects of anandamide and THC agonism on the CB1 and CB2 receptors.

Metabolism

THC is metabolized mainly to 11-OH-THC by the body. This metabolite is still psychoactive and is further oxidized to 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC (THC-COOH). In humans and animals, more than 100 metabolites could be identified, but 11-OH-THC and THC-COOH are the dominating metabolites. Metabolism occurs mainly in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4.[27] More than 55% of THC is excreted in the feces and ~20% in the urine. The main metabolite in urine is the ester of glucuronic acid and THC-COOH and free THC-COOH. In the feces, mainly 11-OH-THC was detected.[28]

Detection in body fluids

THC, 11-OH-THC and THC-COOH can be detected and quantitated in blood, urine, hair, oral fluid or sweat using a combination of immunoassay and chromatographic techniques as part of a drug use testing program or in a forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal offense or suspicious death.[29][30][31]

Effects

THC has mild to moderate analgesic effects, and cannabis can be used to treat pain by altering transmitter release on dorsal root ganglion of the spinal cord and in the periaqueductal gray.[17] Other effects include relaxation, alteration of visual, auditory, and olfactory senses, fatigue, and appetite stimulation. THC has marked antiemetic properties, and may also reduce aggression in certain subjects.[32]

Due to its partial agonistic activity, THC appears to result in greater downregulation of cannabinoid receptors than endocannabinoids, further limiting its efficacy over other cannabinoids. While tolerance may limit the maximal effects of certain drugs, evidence suggests that tolerance develops irregularly for different effects with greater resistance for primary over side-effects, and may actually serve to enhance the drug's therapeutic window.[18] However, this form of tolerance appears to be irregular throughout mouse brain areas.

THC has been shown to have an effect on sex hormones within the endocannabinoid system, and has been linked with adverse effects on human fertility.[33][34][35]

THC, as well as other cannabinoids that contain a phenol group, possesses mild antioxidant activity sufficient to protect neurons against oxidative stress, such as that produced by glutamate-induced excitotoxicity.[16]

Appetite and taste

It has long been known that, in humans, cannabis increases appetite and consumption of food. The mechanism for appetite stimulation in subjects is believed to result from activity in the gastro-hypothalamic axis. CB1 activity in the hunger centers in the hypothalamus increases the palatability of food when levels of a hunger hormone ghrelin increase prior to consuming a meal. After chyme is passed into the duodenum, signaling hormones such as cholecystokinin and leptin are released, causing reduction in gastric emptying and transmission of satiety signals to the hypothalamus. Cannabinoid activity is reduced through the satiety signals induced by leptin release.

A study in mice suggested that based on the connection between palatable food and stimulation of dopamine (DA) transmission in the shell of the nucleus accumbens (NAc), cannabis may not only stimulate taste, but possibly the hedonic (pleasure) value of food as well. The study later demonstrates habitual use of THC lessening this heightened pleasure response, indicating a possible similarity in humans.[25] The inconsistency between DA habituation and enduring appetite observed after THC application suggests that cannabis-induced appetite stimulation is not only mediated by enhanced pleasure from palatable food, but through THC stimulation of another appetitive response as well.

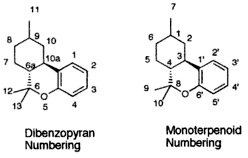

Isomerism

| 7 double bond isomers and their 30 stereoisomers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dibenzopyran numbering | Monoterpenoid numbering | Number of stereoisomers | Natural occurrence | Convention on Psychotropic Substances Schedule | Structure | |||

| Short name | Chiral centers | Full name | Short name | Chiral centers | ||||

| Δ6a,7-tetrahydrocannabinol | 9 and 10a | 8,9,10,10a-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl-3-pentyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ4-tetrahydrocannabinol | 1 and 3 | 4 | No | Schedule I |

|

| Δ7-tetrahydrocannabinol | 6a, 9 and 10a | 6a,9,10,10a-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl-3-pentyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ5-tetrahydrocannabinol | 1, 3 and 4 | 8 | No | Schedule I |

|

| Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol | 6a and 10a | 6a,7,10,10a-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl-3-pentyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ6-tetrahydrocannabinol | 3 and 4 | 4 | Yes | Schedule I |

|

| Δ9,11-tetrahydrocannabinol | 6a and 10a | 6a,7,8,9,10,10a-hexahydro-6,6-dimethyl-9-methylene-3-pentyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ1,7-tetrahydrocannabinol | 3 and 4 | 4 | No | Schedule I |

|

| Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol | 6a and 10a | 6a,7,8,10a-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl-3-pentyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ1-tetrahydrocannabinol | 3 and 4 | 4 | Yes | Schedule II |

|

| Δ10-tetrahydrocannabinol | 6a and 9 | 6a,7,8,9-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl-3-pentyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ2-tetrahydrocannabinol | 1 and 4 | 4 | No | Schedule I |

|

| Δ6a,10a-tetrahydrocannabinol | 9 | 7,8,9,10-tetrahydro-6,6,9-trimethyl-3-pentyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol | Δ3-tetrahydrocannabinol | 1 | 2 | No | Schedule I |

|

Note that 6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-1-ol is the same as 6H-benzo[c]chromen-1-ol.

- Further reading on cannabanoid isomerism: John C. Leffingwell (May 2003). "Chirality & Bioactivity I.: Pharmacology" (PDF). pp. 18–20. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

Toxicity

There has never been a documented human fatality solely from overdosing on tetrahydrocannabinol or cannabis in its natural form.[36] However, numerous reports have suggested an association of cannabis smoking with an increased risk of myocardial infarction.[37][38] Information about the toxicity of THC is primarily based on results from animal studies. The toxicity depends on the route of administration and the laboratory animal.

The estimated lethal dose of intravenous dronabinol is 30 mg/kg,[39] meaning lethality is unlikely. The typical dosage administered is two 2.5 capsules daily; for an 80-kg man (~170 lb) to die from a THC overdose, this would translate to 960 capsules infused intravenously to achieve this high a dose. Non-fatal overdoses have occurred: "Significant CNS symptoms in antiemetic studies followed oral doses of 0.4 mg/kg (28 mg/70 kg) of dronabinol capsules."[39]

Research

The discovery of THC was first described in "Isolation, structure and partial synthesis of an active constituent of hashish", published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society in 1964.[8] Research was also published in the academic journal Science, with "Marijuana chemistry" by Raphael Mechoulam in June 1970,[40] followed by "Chemical basis of hashish activity" in August 1970.[41] In the latter, the team of researchers from Hebrew University Pharmacy School and Tel Aviv University Medical School experimented on monkeys to isolate the active compounds in hashish. Their results provided evidence that, except for tetrahydrocannabinol, no other major active compounds were present in hashish.

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Studies in humans

Evidence suggests that THC helps alleviate symptoms suffered both by AIDS patients, and by cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, by increasing appetite and decreasing nausea.[42][43][44][45] It has also been shown to assist some glaucoma patients by reducing pressure within the eye, and is used in the form of cannabis by a number of multiple sclerosis patients, who use it to alleviate neuropathic pain and spasticity. The National Multiple Sclerosis Society is currently supporting further research into these uses.[46] Studies in humans have been limited by federal and state laws criminalizing marijuana.

In August 2009 a phase IV clinical trial by the Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem, Israel started to investigate the effects of THC on post-traumatic stress disorders.[47]

Dronabinol's usefulness as a treatment for Tourette syndrome cannot be determined without longer controlled studies on larger sample populations.[48][49][50]

Research on THC has shown that the cannabinoid receptors are responsible for mediated inhibition of dopamine release in the retina.[51]

In a 1981 double-blind, placebo-controlled study, oral THC was given to multiple sclerosis patients. A decrease in spasticity was shown when compared with placebo.[52] In a 1983 single-blind, placebo-controlled study, decreased tremor occurred in 1/4 of multiple sclerosis patients.[53]

Several studies have been conducted with spinal injury patients and THC. Decreased tremor occurred in 2/5 patients in a 1986 double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study.[54] THC was shown to decrease spasticity and pain in a 1990 double-blind, placebo-controlled study.[55]

Studies in animals and in vitro

A two-year study in which rats and mice were force-fed tetrahydrocannabinol dissolved in corn oil showed reduced body mass, enhanced survival rates, and decreased tumor incidences in several sites, mainly organs under hormonal control. It also caused testicular atrophy and uterine and ovarian hypoplasia, as well as hyperactivity and convulsions immediately after administration, of which the onset and frequency were dose related.[56]

Research in rats indicates that THC prevents hydroperoxide-induced oxidative damage as well as or better than other antioxidants in a chemical (Fenton reaction) system and neuronal cultures.[57] In mice low doses of Δ9-THC reduces the progression of atherosclerosis.[58]

Research has also shown that past claims of brain damage from cannabis use fail to hold up to the scientific method.[59] Instead, recent studies with synthetic cannabinoids show that activation of CB1 receptors can facilitate neurogenesis,[60] as well as neuroprotection,[61] and can even help prevent natural neural degradation from neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's, and Alzheimer's. This, along with research into the CB2 receptor (throughout the immune system), has given the case for medical marijuana more support.[62][63] THC is both a CB1 and CB2 agonist.[64]

Long-term effects

Its status as an illegal drug in most countries can make research difficult; for instance in the United States where the National Institute on Drug Abuse was the only legal source of cannabis for researchers until it recently became legalized in Colorado and Washington.[65]

Some studies report a variety of negative effects associated with long-term use, including short-term memory loss.[66][67] Using positron emission tomography (PET), one study found altered memory-related brain function in chronic daily cannabis users (23% better memory for the cannabis users in recalling the end of a list of things to remember, but 19% worse memory for cannabis users in recalling the middle of a list of things to remember).[68]

Some studies have suggested that cannabis users have a greater risk of developing psychosis than non-users. This risk is most pronounced in cases with an existing risk of psychotic disorder.[69][70] A 2005 paper from the Dunedin study suggested an increased risk in the development of psychosis linked to polymorphisms in the COMT gene.[71] However, a more recent study cast doubt on the proposed connection between this gene and the effects of cannabis on the development of psychosis.[72]

A 2008 German review reported that cannabis was a causal factor in some cases of schizophrenia and stressed the need for better education among the public due to increasingly relaxed access to cannabis.[73] Though cannabis use has increased dramatically in several countries over the past few decades, the rates of psychosis and schizophrenia have not generally increased, casting some doubt over whether the drug can cause cases that would not otherwise have occurred.[74]

Conversely, research from 2007 reported a correlation between cannabis use and increased cognitive function in schizophrenic patients.[75]

A 2008 National Institutes of Health study of 19 chronic heavy marijuana users with cardiac and cerebral abnormalities (averaging 28 g to 272 g (1 to 9+ oz) weekly) and 24 controls found elevated levels of apolipoprotein C-III (apoC-III) in the chronic smokers.[76] An increase in apoC-III levels induces the development of hypertriglyceridemia.

A 2008 study by the University of Melbourne of 15 heavy marijuana users (consuming at least 5 marijuana cigarettes daily for on average 20 years) and 16 controls found an average size difference for the smokers in the hippocampus (12 percent smaller) and the amygdala (7 percent smaller).[77] It has been suggested that such effects can be reversed with long term abstinence.[78]

A 2007 study at Karolinska Institute suggested that young rats treated with THC received an increased motivation for drug use, heroin in the study, under conditions of stress.[79][80]

A study of around 1000 people in New Zealand found that starting cannabis below the age of 18, when the brain is undergoing major development, induces an 8 point IQ drop on average. This effect was not fully reverted after stopping cannabis use.[81]

Impact on psychosis

A literature review on the subject concluded that "cannabis use appears to be neither a sufficient nor a necessary cause for psychosis. It is a component cause, part of a complex constellation of factors leading to psychosis."[82] In other words, THC and other active substances of cannabis may accentuate symptoms in people already predisposed, but likely don't cause psychotic disorders on their own. However, a French review from 2009 came to a conclusion that cannabis use, particularly that before age 15, was a factor in the development of schizophrenic disorders.[83]

Biosynthesis

In the cannabis plant, THC occurs mainly as tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA, 2-COOH-THC). Geranyl pyrophosphate and olivetolic acid react, catalysed by an enzyme to produce cannabigerolic acid,[84] which is cyclized by the enzyme THC acid synthase to give THCA. Over time, or when heated, THCA is decarboxylated, producing THC. The pathway for THCA biosynthesis is similar to that which produces the bitter acid humulone in hops.[85][86]

Natural occurrence

Cannabis indica may have a CBD:THC ratio 4–5 times that of Cannabis sativa.[citation needed]

Marinol

Dronabinol is the INN for a pure isomer of THC, (–)-trans-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol,[87] which is the main isomer found in cannabis. It is sold as Marinol (a registered trademark of Solvay Pharmaceuticals). Dronabinol is also marketed, sold, and distributed by PAR Pharmaceutical Companies under the terms of a license and distribution agreement with SVC pharma LP, an affiliate of Rhodes Technologies. Synthesized THC may be generally referred to as dronabinol. It is available as a prescription drug (under Marinol[88]) in several countries including the United States and Germany. In the United States, Marinol is a Schedule III drug, available by prescription, considered to be non-narcotic and to have a low risk of physical or mental dependence. Efforts to get cannabis rescheduled as analogous to Marinol have not succeeded thus far, though a 2002 petition has been accepted by the DEA. As a result of the rescheduling of Marinol from Schedule II to Schedule III, refills are now permitted for this substance. Marinol has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the treatment of anorexia in AIDS patients, as well as for refractory nausea and vomiting of patients undergoing chemotherapy, which can remain in the body for up to 5 years, which has raised much controversy[opinion] as to why natural THC is still a schedule I drug.[89]

An overdose usually presents with lethargy, decreased motor coordination, slurred speech, and postural hypotension. The FDA estimates the lethal human dose of intravenous dronabinol to be 30 mg/kg (2100 mg/ 70 kg).[90]

An analog of dronabinol, nabilone, is available commercially in Canada under the trade name Cesamet, manufactured by Valeant Pharmaceuticals. Cesamet has also received FDA approval and began marketing in the U.S. in 2006. Nabilone is a Schedule II drug.[91]

Comparisons with medical marijuana

Female cannabis plants contain more than 60 cannabinoids, including cannabidiol (CBD), thought to be the major anticonvulsant that helps multiple sclerosis patients;[92] and cannabichromene (CBC), an anti-inflammatory which may contribute to the pain-killing effect of cannabis.[93]

It takes over one hour for Marinol to reach full systemic effect,[94] compared to seconds or minutes for smoked or vaporized cannabis.[95] Some patients accustomed to inhaling just enough cannabis smoke to manage symptoms have complained of too-intense intoxication from Marinol's predetermined dosages[citation needed]. Many patients have said that Marinol produces a more acute psychedelic effect than cannabis, and it has been speculated that this disparity can be explained by the moderating effect of the many non-THC cannabinoids present in cannabis.[citation needed] For that reason, alternative THC-containing medications based on botanical extracts of the cannabis plant such as nabiximols are being developed. Mark Kleiman, director of the Drug Policy Analysis Program at UCLA's School of Public Affairs said of Marinol, "It wasn't any fun and made the user feel bad, so it could be approved without any fear that it would penetrate the recreational market, and then used as a club with which to beat back the advocates of whole cannabis as a medicine."[96] Mr. Kleiman's opinion notwithstanding, clinical trials comparing the use of cannabis extracts with Marinol in the treatment of cancer cachexia have demonstrated equal efficacy and well-being among patients in the two treatment arms.[97] United States federal law currently registers dronabinol as a Schedule III controlled substance, but all other cannabinoids remain Schedule I, except synthetics like nabilone.[98]

Regulatory history

Since at least 1986, the trend has been for THC in general, and especially the Marinol preparation, to be downgraded to less and less stringently-controlled schedules of controlled substances, in the U.S. and throughout the rest of the world.

On May 13, 1986, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) issued a Final Rule and Statement of Policy authorizing the "Rescheduling of Synthetic Dronabinol in Sesame Oil and Encapsulated in Soft Gelatin Capsules From Schedule I to Schedule II" (DEA 51 FR 17476-78). This permitted medical use of Marinol, albeit with the severe restrictions associated with Schedule II status[99]. For instance, refills of Marinol prescriptions were not permitted. At its 1045th meeting, on April 29, 1991, the Commission on Narcotic Drugs, in accordance with article 2, paragraphs 5 and 6, of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances, decided that Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (also referred to as Δ9-THC) and its stereochemical variants should be transferred from Schedule I to Schedule II of that Convention. This released Marinol from the restrictions imposed by Article 7 of the Convention (See also United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances).[citation needed]

An article published in the April–June 1998 issue of the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs found that "Healthcare professionals have detected no indication of scrip-chasing or doctor-shopping among the patients for whom they have prescribed dronabinol". The authors state that Marinol has a low potential for abuse.[100]

In 1999, Marinol was rescheduled from Schedule II to III of the Controlled Substances Act, reflecting a finding that THC had a potential for abuse less than that of cocaine and heroin. This rescheduling constituted part of the argument for a 2002 petition for removal of cannabis from Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, in which petitioner Jon Gettman noted, "Cannabis is a natural source of dronabinol (THC), the ingredient of Marinol, a Schedule III drug. There are no grounds to schedule cannabis in a more restrictive schedule than Marinol".[101]

At its 33rd meeting, in 2003, the World Health Organization Expert Committee on Drug Dependence recommended transferring THC to Schedule IV of the Convention, citing its medical uses and low abuse potential.[102]

See also

- Anandamide

- Cannabis (drug)

- Psychoactive drug

- Cannabinoids

- 11-Hydroxy-THC, metabolite of THC

- Anandamide, 2-Arachidonoylglycerol, endogenous cannabinoid agonists

- Cannabidiol (CBD), an isomer of THC

- Cannabinol (CBN), a metabolite of THC

- Dimethylheptylpyran

- Parahexyl

- Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid, the biosynthetic precursor for THC

- HU-210, WIN 55,212-2, JWH-133, synthetic cannabinoid agonists

- Medical cannabis

- War on Drugs

- Cannabis rescheduling in the United States

- Health issues and the effects of cannabis

References

- ^ Marlowe, Douglas B. (December 2010). "The Facts On Marijuana". NADCP.

Based upon several nationwide epidemiological studies, marijuana's dependence liability has been reliably determined to be 8 to 10 percent.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/dockets/05n0479/05N-0479-emc0004-04.pdf

- ^ a b c d e Grotenhermen, F (2003). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids". Clin Pharmacokinet. 42 (4): 327–60. doi:10.2165/00003088-200342040-00003. PMID 12648025.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (30 November 2006). "Cannabis". In Sean C. Sweetman (ed.). Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference: Single User (35th ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85369-703-9.[page needed]

- ^ "Tetrahydrocannabinol – Compound Summary". National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

Dronabinol has a large apparent volume of distribution, approximately 10 L/kg, because of its lipid solubility. The plasma protein binding of dronabinol and its metabolites is approximately 97%.

- ^ "Cannabis and Cannabis Extracts: Greater Than the Sum of Their Parts?" (PDF). Cannabis-med.org. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ a b Garrett, Edward R.; Hunt, C. Anthony (July 1974). "Physicochemical properties, solubility, and protein binding of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol". J. Pharm. Sci. 63 (7): 1056–64. doi:10.1002/jps.2600630705. PMID 4853640.

- ^ a b Gaoni, Y.; Mechoulam, R. (1964). "Isolation, structure and partial synthesis of an active constituent of hashish". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 86 (8): 1646–1647. doi:10.1021/ja01062a046.

- ^ "Interview with the winner of the first ECNP Lifetime Achievement Award: Raphael Mechoulam, Israel". February 2007.

- ^ Geller, Tom (2007). "Cannabinoids: A Secret History". Chemical Heritage Newsmagazine. 25 (2). Archived from the original on 19 June 2008.

- ^ Pate, David W. (1994). "Chemical ecology of Cannabis". Journal of the International Hemp Association. 1 (29): 32–37.

- ^ Pate, David W. (1983). "Possible role of ultraviolet radiation in evolution of Cannabis chemotypes". Economic Botany. 37 (4): 396–405. doi:10.1007/BF02904200.

- ^ Lydon, John; Teramura, Alan H. (1987). "Photochemical decomposition of cannabidiol in its resin base". Phytochemistry. 26 (4): 1216–1217. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)82388-2.

- ^ Lydon, John; Teramura, Alan H.; Coffman, C. Benjamin (1987). "UV-B radiation effects on photosynthesis, growth and cannabinoid production of two Cannabis sativa chemotypes". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 46 (2): 201–206. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.1987.tb04757.x. PMID 3628508.

- ^ a b "PDSP Database – UNC". NIMH Psychoactive Drug Screening Program. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16570099, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16570099instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11316486, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11316486instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17828291, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17828291instead. - ^ Rashidi H.; Akhtar M.T.; van der Kooy F.; Verpoorte R.; Duetz W.A. (November 2009). "Hydroxylation and Further Oxidation of Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol by Alkane-Degrading Bacteria" (PDF). Appl Environ Microbiol. 75 (22): 7135–7141. doi:10.1128/AEM.01277-09. PMC 2786519. PMID 19767471.

Δ9-THC and many of its derivatives are highly lipophilic and poorly water soluble. Calculations of the n-octanol/water partition coefficient (Ko/w) of Δ9-THC at neutral pH vary between 6,000, using the shake flask method, and 9.44 × 106, by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography estimation.

- ^ Ashton CH (February 2001). "Pharmacology and effects of cannabis: a brief review". Br J Psychiatry. 178: 101–106. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.2.101. PMID 11157422.

Because they are extremely lipid soluble, cannabinoids accumulate in fatty tissues, reaching peak concentrations in 4–5 days. They are then slowly released back into other body compartments, including the brain. ... Within the brain, THC and other cannabinoids are differentially distributed. High concentrations are reached in neocortical, limbic, sensory and motor areas.

- ^ Huestis MA (August 2007). "Human cannabinoid pharmacokinetics". Chem Biodivers. 4 (8): 1770–804. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790152. PMC 2689518. PMID 17712819.

THC is highly lipophilic and initially taken up by tissues that are highly perfused, such as the lung, heart, brain, and liver.

- ^ Brown, Hugh (1972). "Possible anticholinesterase-like effects of trans(−)δ8 and -δ9tetrahydrocannabinol as observed in the general motor activity of mice". Psychopharmacologia. 27 (2): 111–6. doi:10.1007/BF00439369. PMID 4638205.

- ^ Eubanks, Lisa M.; Rogers, C.J.; Beuscher, A.E. IV; Koob, G.F.; Olson, A.J.; Dickerson, T.J.; Janda, K.D. (2006). "A Molecular Link Between the Active Component of Marijuana and Alzheimer's Disease Pathology". Molecular Pharmaceutics. 3 (6): 773–7. doi:10.1021/mp060066m. PMC 2562334. PMID 17140265.

- ^ Lupica, Carl R; Riegel, Arthur C; Hoffman, Alexander F (2004). "Marijuana and cannabinoid regulation of brain reward circuits". British Journal of Pharmacology. 143 (2): 227–34. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0705931. PMC 1575338. PMID 15313883.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 22063718, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=22063718instead. - ^ Solinas, M (2007). "Nicotinic 7 Receptors as a New Target for Treatment of Cannabis Abuse". Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (21): 5615–20. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0027-07.2007. PMID 17522306.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help);|first8=missing|last8=(help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Watanabe K, Yamaori S, Funahashi T, Kimura T, Yamamoto I (March 2007). "Cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of tetrahydrocannabinols and cannabinol by human hepatic microsomes". Life Science. 80 (15): 1415–9. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2006.12.032. PMID 17303175.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Huestis, M. A. (2005). "Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism of the Plant Cannabinoids, Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol, Cannabidiol and Cannabinol". Cannabinoids. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 168 (168): 657–90. doi:10.1007/3-540-26573-2_23. ISBN 3-540-22565-X. PMID 16596792.

- ^ Schwilke, EW (2009). "Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), 11-Hydroxy-THC, and 11-Nor-9-carboxy-THC Plasma Pharmacokinetics during and after Continuous High-Dose Oral THC". Clinical Chemistry. 55 (12): 2180–2189. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.122119. PMC 3196989. PMID 19833841.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help);|first8=missing|last8=(help);|first9=missing|last9=(help) - ^ Röhrich, J (2010). "Concentrations of Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and 11-Nor-9-Carboxytetrahydrocannabinol in Blood and Urine After Passive Exposure to Cannabis Smoke in a Coffee Shop". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 34 (4): 196–203. doi:10.1093/jat/34.4.196. PMID 20465865.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help);|first8=missing|last8=(help) - ^ Baselt, R. (2011). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (9th ed.). Seal Beach, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1644–8.

- ^ Hoaken, PN (2003). "Drugs of abuse and the elicitation of human aggressive behavior". Addictive Behaviors. 28 (9): 1533–1554. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.033. PMID 14656544.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help) - ^

Morgan DJ, Muller CH, Murataeva NA, Davis BJ, Mackie K (April 2012). "Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) attenuates mouse sperm motility and male fecundity". Br J Pharmacol. 165 (8): 2575–83. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01506.x. PMC 3423255. PMID 21615727.

Morgan DJ, Muller CH, Murataeva NA, Davis BJ, Mackie K (April 2012). "Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) attenuates mouse sperm motility and male fecundity". Br J Pharmacol. 165 (8): 2575–83. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01506.x. PMC 3423255. PMID 21615727.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Sun X, Dey SK (16 May 2012). "Endocannabinoid signaling in female reproduction". ACS Chem Neurosci. 3 (5): 349–55. doi:10.1021/cn300014e. PMC 3382454. PMID 22860202.

Sun X, Dey SK (16 May 2012). "Endocannabinoid signaling in female reproduction". ACS Chem Neurosci. 3 (5): 349–55. doi:10.1021/cn300014e. PMC 3382454. PMID 22860202.

- ^ Harclerode J (1984). "Endocrine effects of marijuana in the male: preclinical studies". NIDA Res Monogr. 44: 46–64. PMID 6090909.

- ^ Walker, J.Michael; Huang, Susan M (2002). "Cannabinoid analgesia". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 95 (2): 127–35. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(02)00252-8.

...to date, there are no deaths known to have resulted from overdose of cannabis. (p. 128)

- ^ Thomas G, Kloner RA, Rezkalla S (January 2014). "Adverse cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular effects of marijuana inhalation: what cardiologists need to know". Am. J. Cardiol. 113 (1): 187–90. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.09.042. PMID 24176069.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aryana A, Williams MA (May 2007). "Marijuana as a trigger of cardiovascular events: speculation or scientific certainty?". Int. J. Cardiol. 118 (2): 141–4. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.08.001. PMID 17005273.

- ^ a b "DRONABINOL capsule [American Health Packaging]". National Library of Medicine. Daily Med. July 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

The estimated lethal human dose of intravenous dronabinol is 30 mg/kg (2100 mg/70 kg). Significant CNS symptoms in antiemetic studies followed oral doses of 0.4 mg/kg (28 mg/70 kg) of dronabinol capsules.

- ^ Mechoulam, R. (1970). "Marihuana Chemistry". Science. 168 (3936): 1159–1165. Bibcode:1970Sci...168.1159M. doi:10.1126/science.168.3936.1159.

- ^ Mechoulam, R.; Shani, A.; Edery, H.; Grunfeld, Y. (1970). "Chemical Basis of Hashish Activity". Science. 169 (3945): 611–612. Bibcode:1970Sci...169..611M. doi:10.1126/science.169.3945.611. PMID 4987683.

- ^ "Cannabis and Cannabinoids". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ Haney M; Gunderson EW; Rabkin J; Hart, Carl L; Vosburg, Suzanne K; Comer, Sandra D; Foltin, Richard W (2007). "Dronabinol and marijuana in HIV-positive marijuana smokers. Caloric intake, mood, and sleep". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 45 (5): 545–54. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31811ed205. PMID 17589370.

- ^ Abrams DI; Hilton JF; Leiser RJ; Shade SB; Elbeik TA; Aweeka FT; Benowitz NL; Bredt BM; Kosel B; Aberg JA, JA; Deeks SG, SG; Mitchell TF; Mulligan K; Bacchetti P; McCune JM; Schambelan M (2003). "Short-term effects of cannabinoids in patients with HIV-1 infection: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial". Annals of Internal Medicine. 139 (4): 258–66. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-139-4-200308190-00008. PMID 12965981.

- ^ Grotenhermen, Franjo; Russo, Ethan, eds. (2002). "Review of Therapeutic Effects". Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Toxicology and Therapeutic Potential. New York City: Psychology Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-7890-1508-2.

The only approved preparations to date, Marinol (dronabinol, Δ9-THC) and Cesamet (nabilone), are approved for the indication of nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy. Marinol is also approved for anorexia and cachexia in HIV/AIDS.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "Marijuana (Cannabis)". National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT00965809 for "Add on Study on Δ9-THC Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD) (THC_PTSD)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Müller-Vahl, K.R. (2002). "Treatment of Tourette's Syndrome with Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC): A Randomized Crossover Trial". Pharmacopsychiatry. 35 (2): 57–61. doi:10.1055/s-2002-25028. PMID 11951146.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help) - ^ Müller-Vah, K. R. (2003). "Delta 9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is Effective in the Treatment of Tics in Tourette Syndrome". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 64 (4): 459–65. doi:10.4088/JCP.v64n0417. PMID 12716250.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help) - ^ Müller-Vahl, Kirsten R (2003). "Treatment of Tourette Syndrome with Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC): No Influence on Neuropsychological Performance". Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (2): 384–8. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300047. PMID 12589392.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help) - ^ Schlicker, E; Timm, J; Göthert, M (1996). "Cannabinoid receptor-mediated inhibition of dopamine release in the retina". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's archives of pharmacology. 354 (6): 791–5. doi:10.1007/BF00166907. PMID 8971741.

- ^ Petro, DJ; Ellenberg, C (1981). "Treatment of human spasticity with delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 36: 189–261.

- ^ Clifford, DB (1983). "Tetrahydrocannabinol for tremor in multiple sclerosis". Annals of Neurology. 13 (6): 669–671. doi:10.1002/ana.410130616.

- ^ Hannigan, WC; Destree, R; Truong, XT (1986). "The effect of delta-9-THC on human spasticity". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 39: 198.

- ^ HMaurer, M; Henn, V; Dittrich, A; Hofmann, A. (1990). "Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol shows antispastic and analgesic effects in a single case double-blind trial". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 240 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1007/BF02190083. PMID 2175265.

- ^ Chan, P (1996). "Toxicity and Carcinogenicity of Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Fischer Rats and B6C3F1 Mice". Fundamental and Applied Toxicology. 30 (1): 109–17. doi:10.1006/faat.1996.0048. PMID 8812248.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help) - ^ Hampson, A. J.; Grimaldi, M; Axelrod, J; Wink, D (1998). "Cannabidiol and (−)Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol are neuroprotective antioxidants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (14): 8268–73. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.8268H. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.14.8268. PMC 20965. PMID 9653176.

- ^ Steffens, S (2005). "Low dose oral cannabinoid therapy reduces progression of atherosclerosis in mice". Nature. 434 (7034): 782–6. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..782S. doi:10.1038/nature03389. PMID 15815632.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help);|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help);|first8=missing|last8=(help);|first9=missing|last9=(help) - ^ Grant, I (2003). "Non-acute (residual) neurocognitive effects of cannabis use: A meta-analytic study". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 9 (5). doi:10.1017/S1355617703950016.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Jiang, W (2005). "Cannabinoids promote embryonic and adult hippocampus neurogenesis and produce anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 115 (11): 3104–3116. doi:10.1172/JCI25509. PMC 1253627. PMID 16224541.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help) - ^ Sarne, Yosef; Mechoulam, Raphael (2005). "Cannabinoids: Between Neuroprotection and Neurotoxicity". Current Drug Targets – CNS & Neurological Disorders. 4 (6): 677–684. doi:10.2174/156800705774933005.

- ^ Correa, F (2005). "The Role of Cannabinoid System on Immune Modulation: Therapeutic Implications on CNS Inflammation". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 5 (7): 671–675. doi:10.2174/1389557054368790. PMID 16026313.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help);|first8=missing|last8=(help);|first9=missing|last9=(help) - ^ Fernández-Ruiz, J (2007). "Cannabinoid CB2 receptor: a new target for controlling neural cell survival?". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 28 (1): 39–45. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2006.11.001. PMID 17141334.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help) - ^ Pertwee, RG (2010). "Cannabinoid Receptor Ligands" (PDF). Tocris. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Medical Marijuana". Multidisciplinary Association for Psychoactive Substances. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ Bartholomew, J.; Holroyd, S.; Heffernan, T. M (2009). "Does cannabis use affect prospective memory in young adults?". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 24 (2): 241–6. doi:10.1177/0269881109106909. PMID 19825904.

- ^ Indlekofer, F (2008). "Reduced memory and attention performance in a population-based sample of young adults with a moderate lifetime use of cannabis, ecstasy and alcohol". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 23 (5): 495–509. doi:10.1177/0269881108091076. PMID 18635709.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help);|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help);|first8=missing|last8=(help);|first9=missing|last9=(help) - ^ Block, R (2002). "Effects of frequent marijuana use on memory-related regional cerebral blood flow". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 72: 237–50. doi:10.1016/S0091-3057(01)00771-7.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help);|first11=missing|last11=(help);|first12=missing|last12=(help);|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help);|first8=missing|last8=(help);|first9=missing|last9=(help) - ^ Moore, Theresa HM (2007). "Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review". The Lancet. 370 (9584): 319–28. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3. PMID 17662880.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help) - ^ Henquet, C (2005). "Prospective cohort study of cannabis use, predisposition for psychosis, and psychotic symptoms in young people". BMJ. 330 (7481): 11–0. doi:10.1136/bmj.38267.664086.63. PMC 539839. PMID 15574485.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help) - ^ Caspi, A (2005). "Moderation of the Effect of Adolescent-Onset Cannabis Use on Adult Psychosis by a Functional Polymorphism in the Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Gene: Longitudinal Evidence of a Gene X Environment Interaction". Biological Psychiatry. 57 (10): 1117–27. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.026. PMID 15866551.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help);|first11=missing|last11=(help);|first12=missing|last12=(help);|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help);|first8=missing|last8=(help);|first9=missing|last9=(help) - ^ Zammit, S; Spurlock, G; Williams, H; Norton, N; Williams, N; O'Donovan, MC; Owen, MJ (2007). "Genotype effects of CHRNA7, CNR1 and COMT in schizophrenia: interactions with tobacco and cannabis use". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 191 (5): 402–7. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036129. PMID 17978319.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Kawohl, W; Rössler, W (2008). "Cannabis and Schizophrenia: new findings in an old debate". Neuropsychiatrie : Klinik, Diagnostik, Therapie und Rehabilitation : Organ der Gesellschaft Osterreichischer Nervenarzte und Psychiater. 22 (4): 223–9. PMID 19080993.

- ^ Degenhardt L; Hall W; Lynskey M (2001). Comorbidity between cannabis use and psychosis: Modelling some possible relationships (PDF). Technical Report No. 121. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre. ISBN 0-7334-1792-2. OCLC 50418990. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2006. Retrieved 19 August 2006.

- ^ Coulston, C; Perdices, M; Tennant, C (2007). "The neuropsychological correlates of cannabis use in schizophrenia: Lifetime abuse/dependence, frequency of use, and recency of use". Schizophrenia Research. 96 (1–3): 169–184. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2007.08.006. PMID 17826035.

- ^ Jayanthi, S (2008). "Heavy marijuana users show increased serum apolipoprotein C-III levels: evidence from proteomic analyses". Molecular Psychiatry. 15 (1): 101–112. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.50. PMC 2797551. PMID 18475272.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help);|first8=missing|last8=(help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Yucel, M (2008). "Regional Brain Abnormalities Associated With Long-term Heavy Cannabis Use". Archives of General Psychiatry. 65 (6): 694–701. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.694. PMID 18519827.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help) - ^ Chang, L. (2006). "Marijuana use is associated with a reorganized visual-attention network and cerebellar hypoactivation". Brain. 129 (5): 1096–1112. doi:10.1093/brain/awl064.

- ^ Ellgren, Maria (9 February 2007). Neurobiological effects of early life cannabis exposure in relation to the gateway hypothesis (in English and Swedish). Stockholm: Karolinska University Press. ISBN 978-91-7357-064-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Ellgren, Maria; Spano, Sabrina M; Hurd, Yasmin L (2006). "Adolescent Cannabis Exposure Alters Opiate Intake and Opioid Limbic Neuronal Populations in Adult Rats". Neuropsychopharmacology. 32 (3): 607–615. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301127. PMID 16823391.

- ^ "Young cannabis smokers run risk of lower IQ, report claims". BBC. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ Arseneault, L.; Cannon, M; Witton, J; Murray, RM (2004). "Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 184 (2): 110–117. doi:10.1192/bjp.184.2.110. PMID 14754822.

- ^ Laqueille, X. (2009). "Le cannabis est-il un facteur de vulnérabilité des troubles schizophrènes?". Archives de Pédiatrie. 16 (9): 1302–5. doi:10.1016/j.arcped.2009.03.016.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Fellermeier, M; Zenk, MH (1998). "Prenylation of olivetolate by a hemp transferase yields cannabigerolic acid, the precursor of tetrahydrocannabinol". FEBS Letters. 427 (2): 283–5. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00450-5. PMID 9607329.

- ^ Marks, MD (2009). "Identification of candidate genes affecting Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol biosynthesis in Cannabis sativa". Journal of Experimental Botany. 60 (13): 3715–26. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp210. PMC 2736886. PMID 19581347.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help);|first6=missing|last6=(help);|first7=missing|last7=(help);|first8=missing|last8=(help);|first9=missing|last9=(help) - ^ Baker, PB; Taylor, BJ; Gough, TA (June 1981). "The tetrahydrocannabinol and tetrahydrocannabinolic acid content of cannabis products". J Pharm Pharmacol. 33 (6): 369–72. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1981.tb13806.x. PMID 6115009.

- ^ "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2005. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

This international non-proprietary name refers to only one of the stereochemical variants of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, namely (-)-trans-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol

- ^ "Marinol – the Legal Medical Use for the Marijuana Plant". Drug Enforcement Administration. Archived from the original on 21 October 2002. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Eustice, Carol (12 August 1997). "Medicinal Marijuana: A Continuing Controversy". About.com. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Marinol" (PDF). FDA.gov. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations – PART 1308 — SCHEDULES OF CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES". US Department of Justice. DEA Office of Diversion Control. Retrieved 12 January 2014. With changes through 77 FR 4235 (January 27, 2012).

- ^ Pickens, JT (1981). "Sedative activity of cannabis in relation to its delta'-trans-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol content". British Journal of Pharmacology. 72 (4): 649–56. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb09145.x. PMC 2071638. PMID 6269680.

- ^ Burns, TL; Ineck, JR (2006). "Cannabinoid Analgesia as a Potential New Therapeutic Option in the Treatment of Chronic Pain". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 40 (2): 251–260. doi:10.1345/aph.1G217. PMID 16449552.

- ^ MARINOL (dronabinol) capsule drug label/data at DailyMed from U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

- ^ McKim, William A (2002). Drugs and Behavior: An Introduction to Behavioral Pharmacology (5th ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 400. ISBN 0-13-048118-1.

- ^ Greenberg, Gary (1 November 2005). "Respectable Reefer". Mother Jones. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/cam/cannabis/healthprofessional/page5

- ^ "Government eases restrictions on pot derivative". Online Athens. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ 51 Fed. Reg. 17476 (1986), Tuesday, May 13, 1986, pages 17476-17478

- ^ Calhoun, SR; Galloway, GP; Smith, DE (1998). "Abuse potential of dronabinol (Marinol)". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 30 (2): 187–96. doi:10.1080/02791072.1998.10399689. PMID 9692381.[better source needed]

- ^ "Petition to Reschedule Cannabis (Marijuana)" (PDF). Coalition for Rescheduling Cannabis. 9 October 2002.[better source needed]

- ^ "WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence". World Health Organization. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

Further reading

- Calhoun SR, Galloway GP, Smith DE (1998). "Abuse potential of dronabinol (Marinol)". J Psychoactive Drugs. 30 (2): 187–96. doi:10.1080/02791072.1998.10399689. PMID 9692381.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - DEA Moves Marinol To Schedule Three, But Leaves Marijuana in Schedule One. The Magic of Sesame Oil, Richard Cowan, MarijuanaNews.com.

- Template:Wayback, Filed October 9, 2002 with the DEA by the Coalition for Rescheduling Cannabis.