Partition of India: Difference between revisions

Bookishness (talk | contribs) |

Bookishness (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

Each side (the Muslims and the Congress/Sikhs) presented its claim through counsel with no liberty to bargain. The judges too had no mandate to compromise and on all major issues they "divided two and two, leaving Sir Cyril Radcliffe the invidious task of making the actual decisions."<ref name=spate/> |

Each side (the Muslims and the Congress/Sikhs) presented its claim through counsel with no liberty to bargain. The judges too had no mandate to compromise and on all major issues they "divided two and two, leaving Sir Cyril Radcliffe the invidious task of making the actual decisions."<ref name=spate/> |

||

==Administrative consequences of Partition== |

|||

===Economic partition=== |

|||

The Partition entailed a division of almost all property and staff of the Government of India. Bitter disputes had led to an impasse until the two senior bureaucrats H. M. Patil (representing India) and Mohamed Ali (representing Pakistan) were locked up in Sardar Patel’s bedroom with the instruction to stay there until they had reached a consensus. They haggled for hours eventually agreeing that Pakistan would get 17 ½ per cent of bank cash and sterling balances while also sharing 17 ½ per cent of India’s national debt”. Office possessions like desks, chairs down to inkpots and paperclips were partitioned, not without acrimonious haggling. In one instance, a British Superintendent of Police witnesses a fight between his two Hindu and Muslim deputies over who gets the last trombone in Punjab Police, after other musical instruments were equally divided. |

|||

===Military partition=== |

|||

The British Indian Army was divided along religious grounds despite protests from senior army officers, some politicians and bureaucrats. The Sikhs and the Hindus were given the choice to join the Pakistani Army and the Muslims the option of joining Pakistani Army. Even though the British Indian Army was largely secular, the sentiments had become so roused due to the communal riots that the communal harmony of the Army was no longer beyond dispute. |

|||

==Independence, population transfer, and violence== |

==Independence, population transfer, and violence== |

||

Revision as of 20:49, 1 October 2013

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

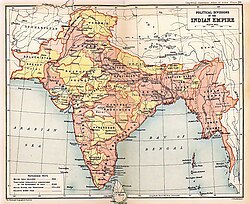

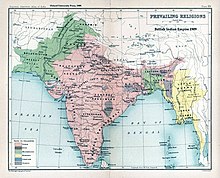

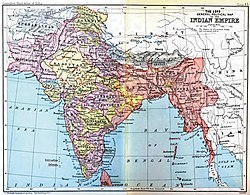

The Partition of India was the partition of the British Indian Empire[1] which led to the creation, on August 14, 1947 and August 15, 1947, respectively, of the sovereign states of the Dominion of Pakistan (later Islamic Republic of Pakistan and People's Republic of Bangladesh) and the Union of India (later Republic of India). "Partition" here refers not only to the division of the Bengal province of British India into East Pakistan and West Bengal (India), and the similar partition of the Punjab province into Punjab (West Pakistan) and Punjab (India), but also to the respective divisions of other assets, including the British Indian Army, the Indian Civil Service and other administrative services, the railways, and the central treasury.

The secession of Bangladesh from Pakistan in the 1971 is not covered by the term Partition of India, nor is the earlier separation of Burma (now Myanmar) from the administration of British India, or the even earlier separation of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Ceylon, part of the Madras Presidency of British India from 1795 until 1798, became a separate Crown Colony in 1798. Burma, gradually annexed by the British during 1826–86 and governed as a part of the British Indian administration until 1937, was directly administered thereafter.[2] Burma was granted independence on January 4, 1948 and Ceylon on February 4, 1948. (See History of Sri Lanka and History of Burma.)

The remaining countries of present-day South Asia, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives were unaffected by the partition. The first two, Nepal and Bhutan, having signed treaties with the British designating them as independent states, were never a part of the British Indian Empire, and therefore their borders were not affected by the partition.[3] The Maldives, which became a protectorate of the British crown in 1887 and gained its independence in 1965, was also unaffected by the partition.

Background

Late nineteenth and early twentieth century

Early independence revolutionaries were overwhelmingly Hindu and were mostly centred in the province of Bengal. Lord Curzon decided to partition Bengal along religious demographics in order to create a split between Hindus and Muslims. There were massive protests against this partition which in turn resulted in its revocation. Since the British did not trust the Hindu officers in the police and the Intelligence Bureau, they transferred Muslim officers from the United Provinces to Bengal, leading to the Hindu revolutionaries looking at Muslims, who were largely politically inactive in the 19th century, as hostile to their cause of freedom. The only Muslim group that was slightly connected with politics in the late 19th century was the Aligarh party, which supported the British Raj.[4] Later, several graduates of the Anglo-Mohammedan Oriental College (now Aligarh Muslim University) formed the All India Muslim League.

The All India Muslim League (AIML) had been formed in Dhaka in 1906 by Muslims who were suspicious[citation needed] of the Hindu-majority Indian National Congress. They complained that Muslim members did not have the same rights as Hindu members.[citation needed] A number of different scenarios were proposed at various times. Among the first to make the demand for a separate state was the writer and philosopher Allama Iqbal, who, in his presidential address to the 1930 convention of the Muslim League, proposed a separate nation for Muslims was essential in an otherwise Hindu-dominated Indian subcontinent. According to Iqbal, such a separation was imminent in a near future, according to his vision.

The Sindh Assembly passed a resolution making its separate nation a demand in 1935. Iqbal, Jouhar and others worked hard to draft a resolution, working with Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who had until then worked for Hindu-Muslim unity and who now was to lead the movement for this new nation. By 1930, Jinnah had begun to despair at the fate of minority communities in a united India and had begun to argue that mainstream parties such as the Congress, of which he was once a member, were insensitive to Muslim interests. By 1930, however, Congress had elected 8 Muslim presidents and included major Muslim figures like Abul Kalam Azad (twice elected President) and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan.

The 1932 Communal Award which seemed to threaten the position of Muslims in Hindu-majority provinces catalysed the resurgence of the Muslim League, with Jinnah as its leader. However, the League did not do well in the 1937 provincial elections, demonstrating the hold of the conservative and local forces at the time.

1932–1942

| Colonial India | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

In 1940, Jinnah made a statement at the Lahore conference that seemed to call for a separate Muslim country. This idea was taken up by Muslims and later by some Hindus[citation needed] in the next seven years, and became a more territorial plan. All Muslim political parties including the Khaksar Tehrik, Jamaat-ei-Islami and Allama Mashriqi opposed the partition of India.[citation needed] Mashriqi was arrested on 19 March 1940.

Savarkar of the Hindu Mahasabha strongly opposed the partition of India. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar summarizes Savarkar's position, in his Pakistan or The Partition of India as follows,

Mr. Savarkar... insists that, although there are two nations in India, India shall not be divided into two parts, one for Muslims and the other for the Hindus; that the two nations shall dwell in one country and shall live under the mantle of one single constitution;... In the struggle for political power between the two nations the rule of the game which Mr. Savarkar prescribes is to be one man one vote, be the man Hindu or Muslim. In his scheme a Muslim is to have no advantage which a Hindu does not have. Minority is to be no justification for privilege and majority is to be no ground for penalty. The State will guarantee the Muslims any defined measure of political power in the form of Muslim religion and Muslim culture. But the State will not guarantee secured seats in the Legislature or in the Administration and, if such guarantee is insisted upon by the Muslims, such guaranteed quota is not to exceed their proportion to the general population.[5]

Most of the Congress leaders were secularists and resolutely opposed the division of India on the lines of religion. Mohandas Gandhi and Allama Mashriqi believed that Hindus and Muslims could and should live in amity. Gandhi opposed the partition, saying, "My whole soul rebels against the idea that Hinduism and Islam represent two antagonistic cultures and doctrines. To assent to such a doctrine is for me a denial of God."[6]

For years, Gandhi and his adherents struggled to keep Muslims in the Congress Party when some Muslim activists began to exit the Congress in the 1930s[citation needed], thereby enghraging both Hindu Nationalists and Indian Muslim nationalists. Gandhi was assassinated soon after the Partition by Hindu extremist Nathuram Godse, who believed that Gandhi was appeasing Muslims at the cost of Hindus[citation needed].

Jinnah's vituperative speech to the Muslim League called forDirect Action Day in August 1946 in Calcutta, in which more than 5,000 people were killed and many more injured. Shaheed Suhrawardy, the Muslim League Chief Minister of Bengal gave a three day break to all civil servants during this period and the army was instructed to stay in barracks. [7] As public order broke down all across northern India and Bengal, the pressure increased to seek a political partition of territories as a way to avoid a full-scale civil war.

1942–1947

Until 1940, the definition of Pakistan as demanded by the League was so flexible that it could have been interpreted as a sovereign nation or as a member of a confederated India.

Some historians believe Jinnah intended to use the threat of partition as a bargaining chip in order to gain more independence for the Muslim dominated provinces in the west from the Hindu-dominated center.[8]

Other historians claim that Jinnah's real vision was for a Pakistan that extended into Hindu-majority areas of India, by demanding the inclusion of the East of Punjab and West of Bengal, including Assam, a Hindu-majority region. Jinnah also fought hard for the annexation of Kashmir, a Muslim majority state with Hindu ruler; and the accession of Hyderabad and Junagadh, Hindu-majority states with Muslim rulers.[citation needed]

The British colonial administration did not directly rule all of "India". There were several different political arrangements in existence: Provinces were ruled directly and the Princely States with varying legal arrangements, like paramountcy.

The British Colonial Administration consisted of Secretary of State for India, the India Office, the Governor-General of India, and the Indian Civil Service. The British were in favour of keeping the area united. The 1946 Cabinet Mission was sent to try and reach a compromise between Congress and the Muslim League. A compromise proposing a decentralized state with much power given to local governments won initial acceptance, but Nehru was unwilling to accept such a decentralized state and Jinnah soon returned to demanding an independent Pakistan.[9]

The Indian political parties were the following: All India Muslim League, Communist Party of India, Majlis-e-Ahrar-ul-Islam, Hindu Mahasabha, Indian National Congress, Khaksar Tehrik, Shiromani Akali Dal and Unionist Muslim League (mainly in the Punjab).

Geographic partition, 1947

Mountbatten Plan

The actual division of British India between the two new dominions was accomplished according to what has come to be known as the 3 June Plan or Mountbatten Plan. It was announced at a press conference by Mountbatten on 3 June 1947, when the date of independence was also announced – 15 August 1947. The plan's main points were:

- Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims in Punjab and Bengal legislative assemblies would meet and vote for partition. If a simple majority of either group wanted partition, then these provinces would be divided.

- Sindh was to take its own decision.

- The fate of North West Frontier Province and Sylhet district of Bengal was to be decided by a referendum.

- India would be independent by 15 August 1947.

- The separate independence of Bengal also ruled out.

- A boundary commission to be set up in case of partition.

The Indian political leaders accepted the Plan on 2 June. It did not deal with the question of the princely states, but on 3 June Mountbatten advised them against remaining independent and urged them to join one of the two new dominions.[10]

The Muslim league's demands for a separate state were thus conceded. The Congress' position on unity was also taken into account while making Pakistan as small as possible. Mountbatten's formula was to divide India and at the same time retain maximum possible unity.

Within British India, the border between India and Pakistan (the Radcliffe Line) was determined by a British Government-commissioned report prepared under the chairmanship of a London barrister, Sir Cyril Radcliffe. Pakistan came into being with two non-contiguous enclaves, East Pakistan (today Bangladesh) and West Pakistan, separated geographically by India. India was formed out of the majority Hindu regions of British India, and Pakistan from the majority Muslim areas.

On 18 July 1947, the British Parliament passed the Indian Independence Act that finalized the arrangements for partition and abandoned British suzerainty over the princely states, of which there were several hundred, leaving them free to choose whether to accede to one of the new dominions. The Government of India Act 1935 was adapted to provide a legal framework for the new dominions.

Following its creation as a new country in August 1947, Pakistan applied for membership of the United Nations and was accepted by the General Assembly on 30 September 1947. The Union of India continued to have the existing seat as India had been a founding member of the United Nations since 1945.[11]

Radcliffe Line

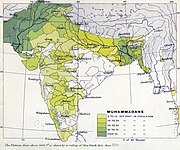

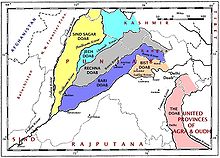

The Punjab – the region of the five rivers east of Indus: Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej — consists of interfluvial doabs, or tracts of land lying between two confluent rivers. These are the Sind-Sagar doab (between Indus and Jhelum), the Jech doab (Jhelum/Chenab), the Rechna doab (Chenab/Ravi), the Bari doab (Ravi/Beas), and the Bist doab (Beas/Sutlej) (see map). In early 1947, in the months leading up to the deliberations of the Punjab Boundary Commission, the main disputed areas appeared to be in the Bari and Bist doabs, although some areas in the Rechna doab were claimed by the Congress and Sikhs. In the Bari doab, the districts of Gurdaspur, Amritsar, Lahore, and Montgomery (Sahiwal) were all disputed.[12]

All districts (other than Amritsar, which was 46.5% Muslim) had Muslim majorities; albeit, in Gurdaspur, the Muslim majority, at 51.1%, was slender. At a smaller area-scale, only three tehsils (sub-units of a district) in the Bari doab had non-Muslim majorities. These were: Pathankot (in the extreme north of Gurdaspur, which was not in dispute), and Amritsar and Tarn Taran in Amritsar district. In addition, there were four Muslim-majority tehsils east of Beas-Sutlej (with two where Muslims outnumbered Hindus and Sikhs together).[12]

Before the Boundary Commission began formal hearings, governments were set up for the East and the West Punjab regions. Their territories were provisionally divided by "notional division" based on simple district majorities. In both the Punjab and Bengal, the Boundary Commission consisted of two Muslim and two non-Muslim judges with Sir Cyril Radcliffe as a common chairman.[12]

The mission of the Punjab commission was worded generally as the following: "To demarcate the boundaries of the two parts of the Punjab, on the basis of ascertaining the contiguous majority areas of Muslims and non-Muslims. In doing so, it will take into account other factors."[12]

Each side (the Muslims and the Congress/Sikhs) presented its claim through counsel with no liberty to bargain. The judges too had no mandate to compromise and on all major issues they "divided two and two, leaving Sir Cyril Radcliffe the invidious task of making the actual decisions."[12]

Administrative consequences of Partition

Economic partition

The Partition entailed a division of almost all property and staff of the Government of India. Bitter disputes had led to an impasse until the two senior bureaucrats H. M. Patil (representing India) and Mohamed Ali (representing Pakistan) were locked up in Sardar Patel’s bedroom with the instruction to stay there until they had reached a consensus. They haggled for hours eventually agreeing that Pakistan would get 17 ½ per cent of bank cash and sterling balances while also sharing 17 ½ per cent of India’s national debt”. Office possessions like desks, chairs down to inkpots and paperclips were partitioned, not without acrimonious haggling. In one instance, a British Superintendent of Police witnesses a fight between his two Hindu and Muslim deputies over who gets the last trombone in Punjab Police, after other musical instruments were equally divided.

Military partition

The British Indian Army was divided along religious grounds despite protests from senior army officers, some politicians and bureaucrats. The Sikhs and the Hindus were given the choice to join the Pakistani Army and the Muslims the option of joining Pakistani Army. Even though the British Indian Army was largely secular, the sentiments had become so roused due to the communal riots that the communal harmony of the Army was no longer beyond dispute.

Independence, population transfer, and violence

Massive population exchanges occurred between the two newly formed states in the months immediately following Partition. Once the lines were established, about 14.5 million people crossed the borders to what they hoped was the relative safety of religious majority. Based on 1951 Census of displaced persons, 7,226,000 Muslims went to Pakistan from India while 7,250,000 Sikhs and Hindus moved to India from Pakistan immediately after partition. [citation needed]

About 11.2 million or 78% of the population transfer took place in the west, with Punjab accounting for most of it; 5.3 million Muslims moved from India to West Punjab in Pakistan, potentially 3.8 million Hindus and Sikhs could have moved from West Pakistan to East Punjab in India but 500,000 had already migrated before the Radcliffe award was announced; elsewhere in the west 1.2 million moved in each direction to and from Sind.

The newly formed governments were completely unequipped to deal with migrations of such staggering magnitude, and massive violence and slaughter occurred on both sides of the border. Estimates of the number of deaths range around roughly 500,000, with low estimates at 200,000 and high estimates at 1,000,000.[13]

Punjab

The Indian state of East Punjab was created in 1947, when the Partition of India split the former British province of Punjab between India and Pakistan. The mostly Muslim western part of the province became Pakistan's Punjab province; the mostly Sikh and Hindu eastern part became India's East Punjab state. Many Hindus and Sikhs lived in the west, and many Muslims lived in the east, and the fears of all such minorities were so great that the partition saw many people displaced and much intercommunal violence.

Lahore and Amritsar were at the centre of the problem, the Boundary Commission was not sure where to place them – to make them part of India or Pakistan. The Commission decided to give Lahore to Pakistan, whilst Amritsar became part of India. Some areas in west Punjab, including Lahore, Rawalpindi, Multan, and Gujrat, had a large Sikh and Hindu population, and many of the residents were attacked or killed. On the other side, in East Punjab, cities such as Amritsar, Ludhiana, Gurdaspur, and Jalandhar had a majority Muslim population, of which thousands were killed or emigrated.

Bengal

The province of Bengal was divided into the two separate entities of West Bengal belonging to India, and East Bengal belonging to Pakistan. East Bengal was renamed East Pakistan in 1955, and later became the independent nation of Bangladesh after the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971.

While the Muslim majority districts of Murshidabad and Malda were given to India, the Hindu majority district of Khulna and the majority Buddhist, but sparsely populated Chittagong Hill Tracts was given to Pakistan by the award.

Sindh

Hindu Sindhis were expected to stay in Sindh following Partition, as there were good relations between Hindu and Muslim Sindhis. At the time of Partition there were 1,400,000 Hindu Sindhis, though most were concentrated in cities such as Hyderabad, Karachi, Shikarpur, and Sukkur. However, because of an uncertain future in a Muslim country, a sense of better opportunities in India, and most of all a sudden influx of Muslim refugees from Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajputana (Rajasthan) and other parts of India, many Sindhi Hindus decided to leave for India.

Problems were further aggravated when incidents of violence instigated by Muslim refugees broke out in Karachi and Hyderabad. According to the census of India 1951, nearly 776,000 Sindhi Hindus moved into India.[14] Unlike the Punjabi Hindus and Sikhs, Sindhi Hindus did not have to witness any massive scale rioting; however, their entire province had gone to Pakistan thus they felt like a homeless community. Despite this migration, a significant Sindhi Hindu population still resides in Pakistan's Sindh province where they number at around 2.28 million as per Pakistan's 1998 census while the Sindhi Hindus in India as per 2001 census of India were at 2.57 million. However Some bordering Districts in Sindh was Hindu Majority like Tharparkar District, Umerkot, Mirpurkhas, Sanghar and Badin, but number is reducing, in fact Umerkot, still has majority Hindu in district.[15]

Perspectives

The Partition was a highly controversial arrangement, and remains a cause of much tension on the Indian subcontinent today. The British Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten of Burma has not only been accused of rushing the process through, but also is alleged to have influenced the Radcliffe Line in India's favour.[16][17] However, the commission took so long to decide on a final boundary that the two nations were granted their independence even before there was a defined boundary between them. Even then, the members were so distraught at their handiwork (and its results) that they refused compensation for their time on the commission.[citation needed]

Some critics allege that British haste led to the cruelties of the Partition.[18] Because independence was declared prior to the actual Partition, it was up to the new governments of India and Pakistan to keep public order. No large population movements were contemplated; the plan called for safeguards for minorities on both sides of the new border. It was a task at which both states failed. There was a complete breakdown of law and order; many died in riots, massacre, or just from the hardships of their flight to safety. What ensued was one of the largest population movements in recorded history. According to Richard Symonds: At the lowest estimate, half a million people perished and twelve million became homeless.[19]

However, many argue that the British were forced to expedite the Partition by events on the ground.[20] Once in office, Mountbatten quickly became aware if Britain were to avoid involvement in a civil war, which seemed increasingly likely, there was no alternative to partition and a hasty exit from India.[20] Law and order had broken down many times before Partition, with much bloodshed on both sides. A massive civil war was looming by the time Mountbatten became Viceroy. After the Second World War, Britain had limited resources,[21] perhaps insufficient to the task of keeping order. Another viewpoint is that while Mountbatten may have been too hasty he had no real options left and achieved the best he could under difficult circumstances.[22] The historian Lawrence James concurs that in 1947 Mountbatten was left with no option but to cut and run. The alternative seemed to be involvement in a potentially bloody civil war from which it would be difficult to get out.[23]

Conservative elements in England consider the partition of India to be the moment that the British Empire ceased to be a world power, following Curzon's dictum: "the loss of India would mean that Britain drop straight away to a third rate power."[24]

Refugees settled in India

Many Sikhs and Hindu Punjabis migrated from Western Punjab and settled in the Indian parts of Punjab and Delhi. Hindus migrating from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) settled across Eastern India and Northeastern India, many ending up in close-by states like West Bengal, Assam, and Tripura. Some migrants were sent to the Andaman Islands where Bengali today form the largest linguistic group.

Hindu Sindhis found themselves without a homeland. The responsibility of rehabilitating them was borne by their government. Refugee camps were set up for Hindu Sindhis. Many refugees overcame the trauma of poverty, though the loss of a homeland has had a deeper and lasting effect on their Sindhi culture. In 1967, the Government of India recognized Sindhi as a fifteenth official language of India in two scripts. In late 2004, the Sindhi Diaspora vociferously opposed a Public Interest Litigation in the Supreme Court of India which asked the Government of India to delete the word "Sindh" from the Indian National Anthem (written by Rabindranath Tagore prior to the partition) on the grounds that it infringed upon the sovereignty of Pakistan.

Delhi received the largest number of refugees for a single city – the population of Delhi grew rapidly in 1947 from under 1 million (917,939) to a little less than 2 million (1,744,072) during the period 1941–1951.[25] The refugees were housed in various historical and military locations such as the Purana Qila, Red Fort, and military barracks in Kingsway (around the present Delhi University). The latter became the site of one of the largest refugee camps in northern India with more than 35,000 refugees at any given time besides Kurukshetra camp near Panipat. The camp sites were later converted into permanent housing through extensive building projects undertaken by the Government of India from 1948 onwards. A number of housing colonies in Delhi came up around this period like Lajpat Nagar, Rajinder Nagar, Nizamuddin East, Punjabi Bagh, Rehgar Pura, Jungpura and Kingsway Camp. A number of schemes such as the provision of education, employment opportunities, and easy loans to start businesses were provided for the refugees at the all-India level. The Delhi refugees, however, were able to make use of these facilities much better than their counterparts elsewhere.[26]

Refugees settled in Pakistan

In the aftermath of partition, a huge population exchange occurred between the two newly formed states. About 14.5 million people crossed the borders, including 7,226,000 Muslims who came to Pakistan from India while 7,249,000 Hindus and Sikhs moved to India from Pakistan. About 5.5 million settled in Punjab, Pakistan and around 1.5 million settled in Sindh.

Most of those migrants who settled in Punjab, Pakistan came from the neighbouring Indian regions of Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh while others were from Jammu and Kashmir and Rajasthan. On the other hand, most of those migrants who arrived in Sindh were primarily of Urdu-speaking background (termed the Muhajir people) and came from the northern and central urban centres of India, such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Rajasthan via the Wahgah and Munabao borders; however a limited number of Muhajirs also arrived by air and on ships. People who wished to go to India from all over Sindh awaited their departure to India by ship at the Swaminarayan temple in Karachi and were visited by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan.[27]

Later in 1950s, the majority of Urdu speaking refugees who migrated after the independence were settled in the port city of Karachi in southern Sindh and in the metropolitan cities of Hyderabad, Sukkur, Nawabshah and Mirpurkhas. In addition, some Urdu-speakers settled in the cities of Punjab, mainly in Lahore, Multan, Bahawalpur and Rawalpindi. The number of migrants in Sindh was placed at over 540,000 of whom two-third were urban. In the case of Karachi, from a population of around 400,000 in 1947, it turned into more than 1.3 million in 1953.

Former President of Pakistan, General Pervez Musharraf, was of Urdu-speaking background and born in the Nahar Vali Haveli in Daryaganj, Delhi, India. Several previous Pakistani leaders were also born in regions that are in India. Pakistan's first prime minister, Liaquat Ali Khan was born in Karnal (now in Haryana). The 7-year longest-serving Governor and martial law administrator of Pakistan's largest province, Balochistan, General Rahimuddin Khan, was born in the predominantly Pathan city of Kaimganj, which now lies in Uttar Pradesh. General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, who came to power in a military coup in 1977, was born in Jalandhar, East Punjab. The families of all four men opted for Pakistan at the time of Partition.

Aftermath

Rehabilitation of women

Both sides promised each other that they would try to restore women abducted during the riots. The Indian government claimed that 33,000 Hindu and Sikh women were abducted, and the Pakistani government claimed that 50,000 Muslim women were abducted during riots. By 1949, there were governmental claims that 12,000 women had been recovered in India and 6,000 in Pakistan.[28] By 1954 there were 20,728 recovered Muslim women and 9,032 Hindu and Sikh women recovered from Pakistan.[29] Most of the Hindu and Sikh women refused to go back to India fearing that they would never be accepted by their family; similarly, the families of some Muslim women refused to take back their relatives.[30]

-

Rural Sikhs in a long ox-cart train headed towards India. 1947. Margaret Bourke-White.

-

Two Muslim men (in a rural refugee train headed towards Pakistan) carrying an old woman in a makeshift doli or palanquin. 1947.

-

"With the tragic legacy of an uncertain future, a young refugee sits on the walls of Purana Qila, transformed into a vast refugee camp in Delhi." Margaret Bourke-White, 1947.

-

A refugee train on its way to Punjab, Pakistan.

-

Photo of a railway station in Punjab. Many people abandoned their fixed assets and crossed newly formed borders.

-

Train to Pakistan steaming out of New Delhi Railway Station, 1947.

-

Train to Pakistan being given a warm send-off. New Delhi railway station, 1947

-

Muslim couple and their grandchildren by the roadside: "The old man is dying of exhaustion. The caravan has gone on,"-Bourke-White.

Treatment of minorities by Pakistan and India

Before independence, Hindus and Sikhs had formed 20 per cent[31] of the population of the areas now forming Pakistan, presently the percentage has "whittled down to one-and-a half percent".[32]: 66 Mahommedali Currim Chagla, a friend of Mahomedali Jinnahbhai, in a speech at the UN General Assembly said that, Pakistan solved its minority problem by the ethnic cleansing of the Hindus, resulting in "hardly any" Hindu minority population in West Pakistan.[33] India suspected Pakistan of ethnic cleansing when millions of Hindus fled its province of East Pakistan in 1971.[34] Hindus remaining in Pakistan have been persecuted.[35][36] Yasmin Saikia writes that "although a large number of Muslims migrated to Pakistan in 1947, the bulk of the Muslim population chose to stay in their homelands in India".[37] According to Azim A. Khan Sherwani, the Hashimpura massacre case is "a chilling reminder of the apathy of the (Indian) state towards access to justice for Muslims", he writes that the case demonstrates that it is not just the Hindutva lobby, but also the Congress-Left and the socialists that are apathetic, and that Muslim "leaders" are more concerned with their personal ambitions and not with "issues afflicting the community".[38] In Pakistan, Hindus have been facing discrimination and often forced to convert to Islam.[39][40]

Pakistan tried preventing Harijans (untouchables etc.) from leaving Pakistan so that they stayed to clean toilets and other things. To this effect, the Government there passed the Essential Services Maintenance Act barring their emigration.[41] Eagerness to woo the Harijans was shown by India by instituting constitutional reforms for their upliftment[42] and setting up of various institutions for their rehabilitation.[43]

Integration of refugee populations with their new countries did not always go smoothly. Some Urdu speaking Muslims (Muhajirs) who migrated to Pakistan have at certain times complained of discrimination in government employment. Municipal political conflict in Karachi, Pakistan's largest city, often pitted native Sindhis against Muhajir settlers. Sindhi, Bengali, and Punjabi refugees in India also experienced poverty and other social issues as they largely came empty-handed. However, fifty years after partition, almost all ex-refugees have managed to rebuild their lives[citation needed]. The repression of minorities in Pakistan remains a global concern but Pakistani politicians have largely ignored the issue. Those who have attempted to lobby or campaign on this issue have been threatened and murdered like Sherry Rehman, and Salman Taseer and Shahbaz Bhatti.[44]

[[]]==Artistic depictions of the Partition==

The partition of India and the associated bloody riots inspired many creative minds in India and Pakistan to create literary/cinematic depictions of this event.[45] While some creations depicted the massacres during the refugee migration, others concentrated on the aftermath of the partition in terms of difficulties faced by the refugees in both side of the border. Even now, more than 60 years after the partition, works of fiction and films are made that relate to the events of partition.

Literature describing the human cost of independence and partition comprises Bal K. Gupta's memoirs "Forgotten Atrocities(2012), Khushwant Singh's Train to Pakistan (1956), several short stories such as Toba Tek Singh (1955) by Saadat Hassan Manto, Urdu poems such as Subh-e-Azadi (Freedom’s Dawn, 1947) by Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Bhisham Sahni's Tamas (1974), Manohar Malgonkar's A Bend in the Ganges (1965), and Bapsi Sidhwa's Ice-Candy Man (1988), among others.[46][47] Salman Rushdie's novel Midnight's Children (1980), which won the Booker Prize and the Booker of Bookers, weaved its narrative based on the children born with magical abilities on midnight of 14 August 1947.[47] Freedom at Midnight (1975) is a non-fiction work by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre that chronicled the events surrounding the first Independence Day celebrations in 1947. There is a paucity of films related to the independence and partition.[48][49][50] Early films relating to the circumstances of the independence, partition and the aftermath include Nemai Ghosh's Chinnamul (Bengali) (1950),[48] Dharmputra (1961)[51] Lahore (1948), Chhalia (1956), Nastik (1953)<ref. Gupta, Bal K.>Ritwik Ghatak's Meghe Dhaka Tara (Bengali) (1960), Komal Gandhar (Bengali) (1961), Subarnarekha (Bengali) (1962);[48][52] later films include Garm Hava (1973) and Tamas (1987).[51] From the late 1990s onwards, more films on this theme were made, including several mainstream films, such as Earth (1998), Train to Pakistan (1998) (based on the aforementined book), Hey Ram (2000), Gadar: Ek Prem Katha (2001), Pinjar (2003), Partition (2007) and Madrasapattinam (2010),.[51] The biopics Gandhi (1982), Jinnah (1998) and Sardar (1993) also feature independence and partition as significant events in their screenplay. A Pakistani drama Daastan, based on the novel Bano, also tells the tale of young Muslim girl during partition. The novel "Lost Generations" (2013) by Manjit Sachdeva describes March 1947 massacre in rural areas of Rawalpindi by Muslim League, followed by massacres on both sides of the new border in August 1947 seen through the eyes of an escaping Sikh family, their settlement and partial rehabilitation in Delhi, and ending in ruin (including death), for the second time in 1984, at the hands of mobs after a Sikh assassinated the prime minister.

See also

- List of Indian Princely States

- Indian independence movement

- Pakistan Movement

- History of Bangladesh

- History of India

- History of Pakistan

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1947

- India (disambiguation)

Notes

- ^ Khan 2007, p. 1.

- ^ Sword For Pen, TIME Magazine, April 12, 1937

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. "Nepal.", Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. "Bhutan."

- ^ India Wins Freedom. 1960.

- ^ Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji (1945). Pakistan or the Partition of India. Mumbai: Thackers.

- ^ Hanson, Eric O. Religion and politics in the international system today. Cambridge University Press,. p. 200. ISBN 0-521-61781-2. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Freedom at Midnight (1975)

- ^ Jalal, Ayesha Jalal (1985). The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, The Muslim League and the Demand Pakistan. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley. A New History of India.

- ^ Sankar Ghose, Jawaharlal Nehru, a biography (1993), p. 181

- ^ Thomas R. G. C., 'Nations, States, and Secession: Lessons from the Former Yugoslavia', in Mediterranean Quarterly, Volume 5 Number 4 (Duke University Press, Fall 1994), pp. 40–65

- ^ a b c d e (Spate 1947, pp. 126–137)

- ^ Death toll in the partition. Users.erols.com.

- ^ Markovits, Claude (2000). The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750–1947. Cambridge University Press. p. 278. ISBN 0-521-62285-9.

- ^ "Population of Hindus in the World". Pakistan Hindu Council.

- ^ K. Z. Islam, 2002, The Punjab Boundary Award, Inretrospect[dead link]

- ^ Partitioning India over lunch, Memoirs of a British civil servant Christopher Beaumont. BBC News (10 August 2007).

- ^ Stanley Wolpert, 2006, Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-515198-4

- ^ Richard Symonds, 1950, The Making of Pakistan, London, OCLC 245793264, p 74

- ^ a b Lawrence J. Butler, 2002, Britain and Empire: Adjusting to a Post-Imperial World, p. 72

- ^ Lawrence J. Butler, 2002, Britain and Empire: Adjusting to a Post-Imperial World, p 72

- ^ Ronald Hyam, Britain's Declining Empire: The Road to Decolonisation, 1918–1968, page 113; Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-86649-9, 2007

- ^ Lawrence James, Rise and Fall of the British Empire

- ^ Judd, Dennis, The Lion and the Tiger: The rise and Fall of the British Raj,1600–1947. Oxford University Press: New York. (2010) p. 138.

- ^ Census of India, 1941 and 1951.

- ^ Kaur, Ravinder (2007). Since 1947: Partition Narratives among Punjabi Migrants of Delhi. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-568377-6.

- ^ Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali Zamindar (2007). The long partition and the making of modern South Asia. Columbia University Press. Retrieved 22 May 2009. Page 52

- ^ Perspectives on Modern South Asia: A Reader in Culture, History, and ... – Kamala Visweswara. nGoogle Books.in (16 May 2011).

- ^ Borders & boundaries: women in India's partition – Ritu Menon, Kamla Bhasi. nGoogle Books.in (24 April 1993).

- ^ Jayawardena, Kumari; de Alwi, Malathi (1996). Embodied violence: Communalising women's sexuality in South Asia. Zed Books.

- ^ Cohen, Stephen (2004). the Idea of Pakistan. Brookings Institution Press. p. 43.

- ^ Outlook. Hathway Investments Pvt Ltd. 2003. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Jai Narain Sharma (1 January 2008). Encyclopaedia of eminent thinkers. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-81-8069-493-6. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Rainer Münz; Myron Weiner (1997). Migrants, refugees, and foreign policy: U.S. and German policies toward countries of origin. Berghahn Books. pp. 276–. ISBN 978-1-57181-087-8. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ US Congress religious freedom report on Pakistan, 2006. State.gov.

- ^ US Congress religious freedom report on Pakistan, 2004. State.gov.

- ^ Yasmin Saikia (2005). Assam and India: fragmented memories, cultural identity, and the Tai-Ahom struggle. Permanent Black. p. 44. ISBN 978-81-7824-123-4. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Khan Sherwani, Azim A. (26 September 2006). "Hashimpura Muslim Massacre Trial Reopens: Can Justice Be Expected?". Countercurrents.org. Kumaranalloor PO, Kottayam District, Kerala. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ "In pictures: Hindus in Pakistan". BBC News. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Walsh, DEclan (25 March 2012). "In Pakistan, Hindus Say Woman's Conversion to Islam Was Coerced". New York Times. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ Bhutalia, Urvashi (2000). The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India. Duke University Press.

- ^

"Constitution of a High Level Committee to prepare a report on the socioeconomic, health and educational status of the tribal communities of India" (Press release). Press Information Bureau , Government of India. 17-August, 2013. Retrieved 18-August, 2013.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Urvashi Butalia (27 August 1998). The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India. Penguin Books. p. 323. ISBN 978-0140271713. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ Saeed, Nasir (30 July 2013). "PAKISTAN: World's concern about minorities in Pakistan". Asian Human Rights Commission.

- ^ Cleary, Joseph N. (3 January 2002). Literature, Partition and the Nation-State: Culture and Conflict in Ireland, Israel and Palestine. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-521-65732-7. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

The partition of India figures in a goo deal of imaginative writing...

- ^ Bhatia, Nandi (1996). "Twentieth Century Hindi Literature". In Natarajan, Nalini (ed.). Handbook of Twentieth-Century Literatures of India. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-0-313-28778-7. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ a b Roy, Rituparna (15 July 2011). South Asian Partition Fiction in English: From Khushwant Singh to Amitav Ghosh. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 24–29. ISBN 978-90-8964-245-5. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ a b c Mandal, Somdatta (2008). "Constructing Post-partition Bengali Cultural Identity through Films". In Bhatia, Nandi; Roy, Anjali Gera (eds.). Partitioned Lives: Narratives of Home, Displacement, and Resettlement. Pearson Education India. pp. 66–69. ISBN 978-81-317-1416-4. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/03068374.2010.508231, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/03068374.2010.508231instead. (subscription required) - ^ Sarkar, Bhaskar (29 April 2009). Mourning the Nation: Indian Cinema in the Wake of Partition. Duke University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8223-4411-7. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ a b c Vishwanath, Gita; Malik, Salma (2009). "Revisiting 1947 through Popular Cinema: a Comparative Study of India and Pakistan" (PDF). Economic and Political Weekly. XLIV (36): 61–69. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Raychaudhuri, Anindya (2009). "Resisting the Resistible: Re-writing Myths of Partition in the Works of Ritwik Ghatak". Social Semiotics. 19 (4): 469–481. doi:10.1080/10350330903361158.(subscription required)

Further reading

- Academic studies

- Ishtiaq Ahmed, Ahmed, Ishtiaq. 2011. The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed: Unravelling the 1947 Tragedy through Secret British Reports and First Person Account. New Delhi: RUPA Publications. 808 pages. ISBN 978-81-291-1862-2

- Ansari, Sarah. 2005. Life after Partition: Migration, Community and Strife in Sindh: 1947—1962. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. 256 pages. ISBN 0-19-597834-X.

- Butalia, Urvashi. 1998. The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 308 pages. ISBN 0-8223-2494-6

- Butler, Lawrence J. 2002. Britain and Empire: Adjusting to a Post-Imperial World. London: I.B.Tauris. 256 pages. ISBN 1-86064-449-X

- Chakrabarty; Bidyut. 2004. The Partition of Bengal and Assam: Contour of Freedom (RoutledgeCurzon, 2004) online edition

- Chatterji, Joya. 2002. Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932—1947. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. 323 pages. ISBN 0-521-52328-1.

- Chester, Lucy P. 2009. Borders and Conflict in South Asia: The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Partition of Punjab.[dead link] Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-7899-6.

- Gilmartin, David. 1988. Empire and Islam: Punjab and the Making of Pakistan. Berkeley: University of California Press. 258 pages. ISBN 0-520-06249-3.

- Gossman, Partricia. 1999. Riots and Victims: Violence and the Construction of Communal Identity Among Bengali Muslims, 1905–1947. Westview Press. 224 pages. ISBN 0-8133-3625-2

- Gupta, Bal K. 2012 "Forgotten Atrocities: Memoirs of a Survivor of 1947 Partition of India". www.lulu.com

- Hansen, Anders Bjørn. 2004. "Partition and Genocide: Manifestation of Violence in Punjab 1937–1947", India Research Press. ISBN 978-81-87943-25-9.

- Harris, Kenneth. Attlee (1982) pp 355–87

- Hasan, Mushirul (2001), India's Partition: Process, Strategy and Mobilization, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 444 pages, ISBN 0-19-563504-3.

- Herman, Arthur. Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry that Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age (2009)

- Ikram, S. M. 1995. Indian Muslims and Partition of India. Delhi: Atlantic. ISBN 81-7156-374-0

- Jain, Jasbir (2007), Reading Partition, Living Partition, Rawat Publications, 338 pages, ISBN 81-316-0045-9

- Jalal, Ayesha (1993), The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 334 pages, ISBN 0-521-45850-1

- Kaur, Ravinder. 2007. "Since 1947: Partition Narratives among Punjabi Migrants of Delhi". Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-568377-6.

- Khan, Yasmin (2007), The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 250 pages, ISBN 0-300-12078-8

- Khosla, G. D. Stern reckoning : a survey of the events leading up to and following the partition of India New Delhi: Oxford University Press:358 pages Published: February 1990 ISBN 0-19-562417-3

- Lamb, Alastair (1991), Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy, 1846–1990, Roxford Books, ISBN 0-907129-06-4

- Metcalf, Barbara; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006), A Concise History of Modern India (Cambridge Concise Histories), Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Pp. xxxiii, 372, ISBN 0-521-68225-8

- Moon, Penderel. (1999). The British Conquest and Dominion of India (2 vol. 1256pp)

- Moore, R.J. (1983). Escape from Empire: The Attlee Government and the Indian Problem, the standard history of the British position

- Nair, Neeti. (2010) Changing Homelands: Hindu Politics and the Partition of India

- Page, David, Anita Inder Singh, Penderel Moon, G. D. Khosla, and Mushirul Hasan. 2001. The Partition Omnibus: Prelude to Partition/the Origins of the Partition of India 1936-1947/Divide and Quit/Stern Reckoning. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-565850-7

- Pal, Anadish Kumar. 2010. World Guide to the Partition of INDIA. Kindle Edition: Amazon Digital Services. 282 KB. ASIN B0036OSCAC

- Pandey, Gyanendra. 2002. Remembering Partition:: Violence, Nationalism and History in India. Cambridge University Press. 232 pages. ISBN 0-521-00250-8 online edition

- Panigrahi; D.N. 2004. India's Partition: The Story of Imperialism in Retreat London: Routledge. online edition

- Raja, Masood Ashraf. Constructing Pakistan: Foundational Texts and the Rise of Muslim National Identity, 1857–1947, Oxford 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-547811-2

- Raza, Hashim S. 1989. Mountbatten and the partition of India. New Delhi: Atlantic. ISBN 81-7156-059-8

- Shaikh, Farzana. 1989. Community and Consensus in Islam: Muslim Representation in Colonial India, 1860—1947. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 272 pages. ISBN 0-521-36328-4.

- Singh, Jaswant. (2011) Jinnah: India, Partition, Independence

- Talbot, Ian and Gurharpal Singh (eds). 1999. Region and Partition: Bengal, Punjab and the Partition of the Subcontinent. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 420 pages. ISBN 0-19-579051-0.

- Talbot, Ian. 2002. Khizr Tiwana: The Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 216 pages. ISBN 0-19-579551-2.

- Talbot, Ian. 2006. Divided Cities: Partition and Its Aftermath in Lahore and Amritsar. Oxford and Karachi: Oxford University Press. 350 pages. ISBN 0-19-547226-8.

- Wolpert, Stanley. 2006. Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 272 pages. ISBN 0-19-515198-4.

- Wolpert, Stanley. 1984. Jinnah of Pakistan

- Articles

- Brass, Paul. 2003. The partition of India and retributive genocide in the Punjab,1946–47: means, methods, and purposes Washington University

- Gilmartin, David. 1998. "Partition, Pakistan, and South Asian History: In Search of a Narrative." The Journal of Asian Studies, 57(4):1068–1095.

- Jeffrey, Robin. 1974. "The Punjab Boundary Force and the Problem of Order, August 1947" – Modern Asian Studies 8(4):491–520.

- Kaur Ravinder. 2007. "India and Pakistan: Partition Lessons". Open Democracy.

- Kaur, Ravinder. 2006. "The Last Journey: Social Class in the Partition of India". Economic and Political Weekly, June 2006. www.epw.org.in

- Khan, Lal (2003). Partition – Can it be undone?. Wellred Publications. p. 228. ISBN 1-900007-15-0.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Mookerjea-Leonard, Debali. 2005. "Divided Homelands, Hostile Homes: Partition, Women and Homelessness". Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 40(2):141–154.

- Mookerjea-Leonard, Debali. 2004. "Quarantined: Women and the Partition". Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 24(1): 35–50.

- Morris-Jones. 1983. "Thirty-Six Years Later: The Mixed Legacies of Mountbatten's Transfer of Power". International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs), 59(4):621–628.

- Noorani, A. G. (22 Dec. 2001 – 4 Jan. 2002). "The Partition of India". Frontline (magazine). 18 (26). Retrieved 12 October 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Spate, O. H. K. (1947), "The Partition of the Punjab and of Bengal", The Geographical Journal, 110 (4/6): 201–218

- Spear, Percival. 1958. "Britain's Transfer of Power in India." Pacific Affairs, 31(2):173–180.

- Talbot, Ian. 1994. "Planning for Pakistan: The Planning Committee of the All-India Muslim League, 1943–46". Modern Asian Studies, 28(4):875–889.

Visaria, Pravin M. 1969. "Migration Between India and Pakistan, 1951–61" Demography, 6(3):323–334.

- Chopra, R. M., "The Punjab And Bengal", Calcutta, 1999.

- Primary sources

- Mansergh, Nicholas, and Penderel Moon, eds. The Transfer of Power 1942–47 (12 vol., London: HMSO . 1970–83) comprehensive collection of British official and private documents

- Moon, Penderel. (1998) Divide & Quit

- Popularizations

- Collins, Larry and Dominique Lapierre: Freedom at Midnight. London: Collins, 1975. ISBN 0-00-638851-5

- Zubrzycki, John. (2006) The Last Nizam: An Indian Prince in the Australian Outback. Pan Macmillan, Australia. ISBN 978-0-330-42321-2.

- Memoirs and oral history

- Bonney, Richard; Hyde, Colin; Martin, John. "Legacy of Partition, 1947–2009: Creating New Archives from the Memories of Leicestershire People," Midland History, (Sept 2011), Vol. 36 Issue 2, pp 215–224

- Azad, Maulana Abul Kalam: India Wins Freedom, Orient Longman, 1988. ISBN 81-250-0514-5

- Mountbatten, Pamela. (2009) India Remembered: A Personal Account of the Mountbattens During the Transfer of Power

- Historical-Fiction

- Mohammed, Javed: Walk to Freedom, Rumi Bookstore, 2006. ISBN 978-0-9701261-2-2

- ((Chopra, R.M., "The Punjab And Bengal", Calcutta, 1999.

External links

- Bibliographies

- Select Research Bibliography on the Partition of India, Compiled by Vinay Lal, Department of History, UCLA; University of California at Los Angeles list

- A select list of Indian Publications on the Partition of India (Punjab & Bengal); University of Virginia list

- South Asian History: Colonial India — University of California, Berkeley Collection of documents on colonial India, Independence, and Partition

- Indian Nationalism — Fordham University archive of relevant public-domain documents

- Other links

- Clip from 1947 newsreel showing Indian independence ceremony

- Through My Eyes Website Imperial War Museum – Online Exhibition (including images, video and interviews with refugees from the Partition of India)

- A People Partitioned Five radio programmes broadcast on the BBC World Service in 1997 containing the voices of people across South Asia who lived through Partition.