Russian invasion of Ukraine: Difference between revisions

Jim Michael (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

m →Leadership of Putin and Zelenskyy: "shunned by the global community" -> "shunned by much of the global community" |

||

| Line 398: | Line 398: | ||

== Leadership of Putin and Zelenskyy == |

== Leadership of Putin and Zelenskyy == |

||

The leadership of the presidents of Russia and Ukraine was a prominent factor in the conflict. According to the portrayal in Western media, as the autocratic ruler of Russia,<ref>{{cite news |date=13 November 2021 |title=Vladimir Putin has shifted from autocracy to dictatorship |work=The Economist |url=https://www.economist.com/briefing/2021/11/13/vladimir-putin-has-shifted-from-autocracy-to-dictatorship |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref> Putin was effectively in sole control of the country's policy and was the sole architect of the war with Ukraine. His leadership was characterised by his failures to anticipate the will of the Ukrainian people to oppose the invasion, the worldwide backlash, and the poor performance of his own forces.<ref>{{cite news |author-last1=Nast |author-first1=Condé |date=26 February 2022 |title=Putin's Bloody Folly in Ukraine |work=[[The New Yorker]] |url=https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/03/07/putins-bloody-folly-in-ukraine |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |author-last1=Bump |author-first1=Philip |date=28 February 2022 |title=The bizarre, literal isolation of Vladimir Putin |work=The Washington Post |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/02/28/putin-bizarre-isolation/ |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Harris |first1=Shane |date=2 March 2022 |title=In Putin, intelligence analysts see an isolated leader who underestimated the West but could lash out if cornered |work=[[The Washington Post]] |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2022/03/01/ukraine-cia-putin-analysis/ |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref> Putin swiftly became a pariah, and was shunned by the global community.<ref>{{cite news |author-last1=Beaumont |author-first1=Peter |author-last2=Graham-Harrison |author-first2=Emma |author-last3=Oltermann |author-first3=Philip |author-last4=Roth |author-first4=Andrew |date=26 February 2022 |title=Putin shunned by world as his hopes of quick victory evaporate |work=[[The Guardian]] |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/feb/26/the-world-shuns-pariah-putin |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref> This contrasted with the leadership of Zelenskyy, who quickly became a national hero,<ref>{{cite news |author-last1=Pieper |author-first1=Oliver |date=26 February 2022 |title=Ukraine's Volodymyr Zelenskyy: From comedian to national hero |work=[[Deutsche Welle]] |url=https://www.dw.com/en/ukraines-volodymyr-zelenskyy-from-comedian-to-national-hero/a-60924507 |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |date=26 February 2022 |title=Zelenskyy's unlikely journey, from comedy to wartime leader |work=[[AP News]] |url=https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-volodymyr-zelenskyy-kyiv-poland-europe-c270027c825e009ed66988bb98a3476e |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref> uniting the Ukrainian people and rising from obscurity to become an international icon.<ref>{{cite news |date=27 February 2022 |title=To many he's the face of Ukrainian bravery — but Volodymyr Zelenskyy is an unlikely wartime leader |work=[[ABC News (Australia)|ABC News]] |url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-02-27/zelenskyy-s-unlikely-journey-from-comedy-to-wartime-leader/100865896 |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author-last=Pierson |author-first=Carli |date=26 February 2022 |title='I need ammunition, not a ride': Zelenskyy is the hero his country needs as Russia invades |url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2022/02/26/ukrainian-president-zelenskyy-has-held-firm-against-russia-putin/6951859001/ |access-date=2 March 2022 |website=[[USA Today]]}}</ref> |

The leadership of the presidents of Russia and Ukraine was a prominent factor in the conflict. According to the portrayal in Western media, as the autocratic ruler of Russia,<ref>{{cite news |date=13 November 2021 |title=Vladimir Putin has shifted from autocracy to dictatorship |work=The Economist |url=https://www.economist.com/briefing/2021/11/13/vladimir-putin-has-shifted-from-autocracy-to-dictatorship |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref> Putin was effectively in sole control of the country's policy and was the sole architect of the war with Ukraine. His leadership was characterised by his failures to anticipate the will of the Ukrainian people to oppose the invasion, the worldwide backlash, and the poor performance of his own forces.<ref>{{cite news |author-last1=Nast |author-first1=Condé |date=26 February 2022 |title=Putin's Bloody Folly in Ukraine |work=[[The New Yorker]] |url=https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/03/07/putins-bloody-folly-in-ukraine |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |author-last1=Bump |author-first1=Philip |date=28 February 2022 |title=The bizarre, literal isolation of Vladimir Putin |work=The Washington Post |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/02/28/putin-bizarre-isolation/ |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Harris |first1=Shane |date=2 March 2022 |title=In Putin, intelligence analysts see an isolated leader who underestimated the West but could lash out if cornered |work=[[The Washington Post]] |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2022/03/01/ukraine-cia-putin-analysis/ |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref> Putin swiftly became a pariah, and was shunned by much of the global community.<ref>{{cite news |author-last1=Beaumont |author-first1=Peter |author-last2=Graham-Harrison |author-first2=Emma |author-last3=Oltermann |author-first3=Philip |author-last4=Roth |author-first4=Andrew |date=26 February 2022 |title=Putin shunned by world as his hopes of quick victory evaporate |work=[[The Guardian]] |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/feb/26/the-world-shuns-pariah-putin |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref> This contrasted with the leadership of Zelenskyy, who quickly became a national hero,<ref>{{cite news |author-last1=Pieper |author-first1=Oliver |date=26 February 2022 |title=Ukraine's Volodymyr Zelenskyy: From comedian to national hero |work=[[Deutsche Welle]] |url=https://www.dw.com/en/ukraines-volodymyr-zelenskyy-from-comedian-to-national-hero/a-60924507 |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |date=26 February 2022 |title=Zelenskyy's unlikely journey, from comedy to wartime leader |work=[[AP News]] |url=https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-volodymyr-zelenskyy-kyiv-poland-europe-c270027c825e009ed66988bb98a3476e |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref> uniting the Ukrainian people and rising from obscurity to become an international icon.<ref>{{cite news |date=27 February 2022 |title=To many he's the face of Ukrainian bravery — but Volodymyr Zelenskyy is an unlikely wartime leader |work=[[ABC News (Australia)|ABC News]] |url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-02-27/zelenskyy-s-unlikely-journey-from-comedy-to-wartime-leader/100865896 |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author-last=Pierson |author-first=Carli |date=26 February 2022 |title='I need ammunition, not a ride': Zelenskyy is the hero his country needs as Russia invades |url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2022/02/26/ukrainian-president-zelenskyy-has-held-firm-against-russia-putin/6951859001/ |access-date=2 March 2022 |website=[[USA Today]]}}</ref> |

||

In the beginning of the conflict, Zelenskyy refused to leave the capital, pledging to stay and fight.<ref>{{cite web |date=25 February 2022 |title=Ukraine's Zelenskyy says he is Russia's 'number one target' |url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/25/ukraine-president-vows-to-stay-put-russian-troops-approach-kyiv |access-date=2 March 2022 |website=[[Al Jazeera]]}}</ref> When the US offered to evacuate him, Zelenskyy replied that he needed ammunition and not a ride.<ref>{{cite web |date=26 February 2022 |title=Zelensky rejects US evacuation offer: I need ammunition, 'not a ride' |url=https://www.timesofisrael.com/zelensky-rejects-us-evacuation-offer-from-ukraine-i-need-ammunition-not-a-ride/ |access-date=2 March 2022 |website=[[Times of Israel]]}}</ref> He used social media effectively, posting selfies of himself walking the streets of Kyiv as the city was under attack to prove that he was still alive.<ref>{{cite web |author-last1=Jack |author-first1=Victor |author-last2=Stolton |author-first2= Samuel |date=1 March 2022 |title=Ukraine wages 'information insurgency' to keep Russia off balance |url=https://www.politico.eu/article/ukraine-wages-information-insurgency-to-keep-russia-off-balance/ |access-date=2 March 2022 |website=[[Politico]]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=26 February 2022 |title=Ukrainian President Zelenskyy posts a selfie video from Kyiv, says 'we will defend our country' |url=https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/ukrainian-president-zelenskyy-posts-a-selfie-video-from-kyiv-says-we-will-defend-our-country/videoshow/89846564.cms |access-date=2 March 2022 |website=[[The Economic Times]]}}</ref> Zelenskyy was highly effective in lobbying his allies for support. He appeared before numerous gatherings of international leaders, telling a conference of European leaders that this might be the last time they would see him,<ref>{{cite web |author-last=Ravid |author-first=Barak |date=25 February 2022 |title=Zelensky to EU leaders: 'This might be the last time you see me alive' |url=https://www.axios.com/zelensky-eu-leaders-last-time-you-see-me-alive-3447dbc0-620d-4ccc-afad-082e81d7a29f.html |access-date=2 March 2022 |website=[[Axios (website)|Axios]]}}</ref> and appearing before the European Parliament where he earned a standing ovation.<ref>{{cite news |date=1 March 2022 |title='Nobody is going to break us': Zelenskyy's emotional plea to EU brings interpreters to tears |work=[[ABC News (Australia)|ABC News) |url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-03-02/zelenskyy-calls-on-russia-to-cease-fire-before-talks/100852898 |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref> |

In the beginning of the conflict, Zelenskyy refused to leave the capital, pledging to stay and fight.<ref>{{cite web |date=25 February 2022 |title=Ukraine's Zelenskyy says he is Russia's 'number one target' |url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/25/ukraine-president-vows-to-stay-put-russian-troops-approach-kyiv |access-date=2 March 2022 |website=[[Al Jazeera]]}}</ref> When the US offered to evacuate him, Zelenskyy replied that he needed ammunition and not a ride.<ref>{{cite web |date=26 February 2022 |title=Zelensky rejects US evacuation offer: I need ammunition, 'not a ride' |url=https://www.timesofisrael.com/zelensky-rejects-us-evacuation-offer-from-ukraine-i-need-ammunition-not-a-ride/ |access-date=2 March 2022 |website=[[Times of Israel]]}}</ref> He used social media effectively, posting selfies of himself walking the streets of Kyiv as the city was under attack to prove that he was still alive.<ref>{{cite web |author-last1=Jack |author-first1=Victor |author-last2=Stolton |author-first2= Samuel |date=1 March 2022 |title=Ukraine wages 'information insurgency' to keep Russia off balance |url=https://www.politico.eu/article/ukraine-wages-information-insurgency-to-keep-russia-off-balance/ |access-date=2 March 2022 |website=[[Politico]]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=26 February 2022 |title=Ukrainian President Zelenskyy posts a selfie video from Kyiv, says 'we will defend our country' |url=https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/ukrainian-president-zelenskyy-posts-a-selfie-video-from-kyiv-says-we-will-defend-our-country/videoshow/89846564.cms |access-date=2 March 2022 |website=[[The Economic Times]]}}</ref> Zelenskyy was highly effective in lobbying his allies for support. He appeared before numerous gatherings of international leaders, telling a conference of European leaders that this might be the last time they would see him,<ref>{{cite web |author-last=Ravid |author-first=Barak |date=25 February 2022 |title=Zelensky to EU leaders: 'This might be the last time you see me alive' |url=https://www.axios.com/zelensky-eu-leaders-last-time-you-see-me-alive-3447dbc0-620d-4ccc-afad-082e81d7a29f.html |access-date=2 March 2022 |website=[[Axios (website)|Axios]]}}</ref> and appearing before the European Parliament where he earned a standing ovation.<ref>{{cite news |date=1 March 2022 |title='Nobody is going to break us': Zelenskyy's emotional plea to EU brings interpreters to tears |work=[[ABC News (Australia)|ABC News) |url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-03-02/zelenskyy-calls-on-russia-to-cease-fire-before-talks/100852898 |access-date=2 March 2022}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 13:18, 2 March 2022

This article documents a current military offensive. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (February 2022) |

| 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russo-Ukrainian War | |||||||

Military situation as of 9 July 2024 Ukraine Ukrainian territories occupied by Russia and pro-Russian separatists See also: Detailed map of the Russo-Ukrainian War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| |||||||

| Order of battle for the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

| |||||||

On 24 February 2022, Russia launched a large-scale military invasion of Ukraine, one of its neighbours to the southwest, marking an escalation to a conflict that began in 2014. Following Ukraine's Revolution of Dignity in 2014, Russia had annexed Crimea and Russian-backed separatist forces had seized part of the Donbas in eastern Ukraine, leading to an eight-year war in the region.[50][51] Many reports called the invasion the largest conventional warfare attack in Europe since World War II.[52][53][54]

Starting early in 2021, Russia built up its military around Ukraine's borders with Russia and Belarus. The US and others accused Russia of planning an invasion, but Russian officials repeatedly issued denials.[55][56] During the crisis, Russian president Vladimir Putin condemned the post-1997 enlargement of NATO as a threat to his country's security, a claim which NATO rejects,[57] and demanded Ukraine be barred from ever joining the NATO military alliance.[58] Putin expressed Russian irredentist views,[59] and questioned Ukraine's right to sovereignty.[60][61] Before the invasion, in an attempt to provide a casus belli, Putin accused Ukraine of committing genocide against Russian speakers in Ukraine, accusations that have been widely described as baseless.[62][63]

On 21 February 2022, Russia officially recognised the Donetsk and Luhansk people's republics, two self-proclaimed states controlled by pro-Russian forces in the Donbas.[64] The following day, Russia's Federation Council unanimously authorised Putin to use military force abroad, and Russia openly sent troops into the breakaway territories.[65] Around 05:00 EET (UTC+2) on 24 February, Putin announced a "special military operation"[d][67] in eastern Ukraine; minutes later, missiles began to hit locations across Ukraine, including the capital, Kyiv. The State Border Guard Service of Ukraine said that its border posts with Russia and Belarus were attacked.[68][69] Two hours later, Russian ground forces entered the country.[70] Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy responded by enacting martial law, severing diplomatic ties with Russia, and ordering general mobilisation.[71][72]

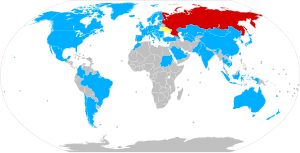

The invasion received widespread international condemnation, including new sanctions imposed on Russia, triggering a financial crisis. Global protests took place against the invasion, while protests in Russia were met with mass arrests.[73][74] Both prior to and during the invasion, various states provided Ukraine with foreign aid, including arms and other materiel support.[75]

Background

Post-Soviet context and Orange Revolution

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine and Russia maintained close ties. In 1994, Ukraine agreed to abandon its nuclear arsenal by signing the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances, on the condition that Russia, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States (US) would provide assurances against threats or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine. Five years later, Russia was one of the signatories of the Charter for European Security, which "reaffirmed the inherent right of each and every participating State to be free to choose or change its security arrangements, including treaties of alliance, as they evolve".[76]

In 2004, Viktor Yanukovych, then Prime Minister of Ukraine, was declared the winner of the Ukrainian presidential election, despite allegations of vote-rigging by election observers.[77] The results caused a public outcry in support of the opposition candidate, Viktor Yushchenko, and widespread peaceful protests challenged the outcome in what became known as the Orange Revolution. During the tumultuous months of the revolution, Yushchenko suddenly became gravely ill, and was soon found by multiple independent physician groups to have been poisoned by TCDD dioxin.[78][79] Yushchenko strongly suspected Russian involvement in his poisoning.[80] After the Supreme Court of Ukraine annulled the initial election result, a re-run of the second round was held, bringing Yushchenko and Yulia Tymoshenko to power and leaving Yanukovych in opposition.[81]

Yanukovych announced his intent to again run for president in the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election,[82] which he subsequently won.[83]

Euromaidan, Revolution of Dignity, and war in Donbas

The Euromaidan protests began in 2013 over the Ukrainian government's decision to suspend the signing of the European Union–Ukraine Association Agreement, instead choosing closer ties to Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union. Following weeks of protests, Yanukovych and the leaders of the Ukrainian parliamentary opposition signed a settlement agreement on 21 February 2014 that called for an early election. The following day, Yanukovych fled from Kyiv ahead of an impeachment vote that stripped him of his powers as president.[84][85][86] Leaders of Russian-speaking Eastern Ukraine declared continuing loyalty to Yanukovych,[87] leading to pro-Russian unrest.[88]

The unrest was followed by the annexation of Crimea by Russia in March 2014 and the war in Donbas, which started in April 2014 with the creation of the Russia-backed quasi-states of the Donetsk and Luhansk people's republics.[89][90] Russian troops were involved in the conflict, although Russia formally denied this.[91][92] The Minsk agreements were signed in September 2014 and February 2015 in a bid to stop the fighting, although ceasefires repeatedly failed.[93]

In July 2021, Putin published an essay titled On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians, in which he re-affirmed his view that Russians and Ukrainians were "one people".[94] American historian Timothy D. Snyder described Putin's ideas as imperialism.[95] British journalist Edward Lucas described it as historical revisionism.[96] Other observers have described the Russian leadership as having a distorted view of modern Ukraine and its history.[97][98][99] Ukraine and other European countries neighbouring Russia accused Putin of attempting Russian irredentism and of pursuing aggressive militaristic policies.[100][101][102]

Prelude

Russian military build-ups

From March to April 2021, Russia commenced a major military build-up near the Russo-Ukrainian border. The second phase of military build-ups took place from October 2021 to February 2022. Russian equipment marked with a white Z symbol, which is not a Cyrillic letter, were spotted on the sides of the equipment during the build-up. Tanks, fighting vehicles, and other equipment bearing the symbol were seen as late as 22 February 2022. Observers believed that the marking was a deconfliction measure meant to prevent friendly fire incidents.[104]

Russian officials' denials of plans to invade

Despite the Russian military build-ups,[105] Russian officials over months repeatedly denied that Russia had plans to invade Ukraine.[55][56][106] On 12 November 2021, Putin's spokesman Dmitry Peskov told reporters that "Russia doesn't threaten anyone"[55][56] and on 12 December, he said that tensions regarding Ukraine were "being created to further demonise Russia and cast it as a potential aggressor".[55]

On 19 January 2022, Russian deputy foreign minister Sergei Ryabkov said that Russia does "not want and will not take any action of aggressive character. We will not attack, strike, invade, quote unquote, whatever Ukraine."[55] On 12 February, Kremlin foreign affairs adviser Yuri Ushakov described warnings of an invasion as "hysteria".[55][56] On 20 February, Russia's ambassador to the US Anatoly Antonov said that Russian forces "don't threaten anyone. ... There is no invasion. There is [sic] no such plans."[56]

The US sought to counter Russian denials by releasing intelligence relating to Russian invasion plans, including satellite photographs of buildup and movement of Russian troops and equipment near the Ukrainian border. The US also claimed the existence of a list of key Ukrainians to be killed or detained upon invasion.[107]

On 31 January, Colonel-General Leonid Ivashov, as chairman of the Russian Officers' Assembly, issued an appeal against Russia's war with Ukraine.[108] He accused Putin and the leadership of Russia of preparing such a war and called on them to resign.[109][110]

Russian accusations and demands

In the leadup to the invasion, Putin and Kremlin officials engaged in a protracted series of accusations against Ukraine as well as demands against Ukraine and NATO, which some commentators and Western officials described as an attempt to generate justification for war.[111][112] On 9 December 2021, Putin spoke of discrimination against Russian speakers outside Russia, saying: "I have to say that Russophobia is a first step towards genocide."[113][114] On 15 February 2022, Putin told the press: "What is going on in Donbas is exactly genocide."[112] The Russian government also condemned the language policy in Ukraine.[115][116][117]

On 18 February, Anatoly Antonov, the Russian ambassador to the US, accused the US of condoning the forced cultural assimilation of Russians in Ukraine.[118] In an address on 21 February, Putin said that Ukrainian society "was faced with the rise of far-right nationalism, which rapidly developed into aggressive Russophobia and neo-Nazism."[119][120][121] Putin claimed that "Ukraine never had a tradition of genuine statehood" and was wrongly created by Soviet Russia.[60][122]

Putin's claims were generally ineffective and largely dismissed by the international community.[123] In particular, Russian claims of genocide have been widely rejected as baseless.[62][63] The European Commission has also rejected the allegations as "Russian disinformation".[124] The US embassy in Ukraine called the Russian genocide claim a "reprehensible falsehood".[125] Ned Price, a spokesperson for the US State Department, said that Moscow was making such claims as an excuse for invading Ukraine.[112]

According to press reports, Putin used a "false 'Nazi' narrative" to justify Russia's attack on Ukraine, taking advantage of collaboration in German-occupied Ukraine during World War II. Analysts said that while Ukraine has a far-right fringe, including the neo-Nazi Azov Battalion, Putin greatly exaggerated the scale of the issue, and that there is no widespread support for this ideology in the government, military, or electorate.[121][111][126]

Addressing the Russian claims specifically, Ukrainian president Zelenskyy, who is Jewish, stated that his grandfather served in the Soviet Army fighting against the Nazis;[127] three of his family members died in the Holocaust.[128] The US Holocaust Memorial Museum condemned Putin's abuse of Holocaust history as a justification for war.[129][130] Some commentators described Putin's claims as reflecting his isolation and reliance on an inner circle who were unable to give him frank advice.[131]

During the second build-up, Russia issued demands to the US and NATO, including a legally binding promise that Ukraine would not join NATO, as well as a reduction in NATO troops and military hardware stationed in Eastern Europe.[132] In addition, Russia threatened an unspecified military response if NATO continued to follow an "aggressive line".[133] These demands were largely interpreted as being non-viable; new NATO members had joined as their populations broadly preferred to move towards the safety and economic opportunities offered by NATO and the European Union (EU), and away from Russia.[134] The demand for a formal treaty preventing Ukraine from joining NATO was also seen as unviable, although NATO showed no desire to accede to Ukraine's requests to join.[135]

Alleged clashes

Fighting in Donbas escalated significantly on 17 February 2022. While the daily number of attacks over the first six weeks of 2022 ranged from two to five,[136] the Ukrainian military reported 60 attacks on 17 February. Russian state media also reported over 20 artillery attacks on separatist positions the same day.[136] The Ukrainian government accused Russian separatists of shelling a kindergarten at Stanytsia Luhanska using artillery, injuring three civilians. The Luhansk People's Republic said that its forces had been attacked by the Ukrainian government with mortars, grenade launchers, and machine gun fire.[137][138]

On 18 February, the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic ordered mandatory emergency evacuations of civilians from their respective capital cities,[139][140][141] although observers noted that full evacuations would take months to accomplish.[142] Ukrainian media reported a sharp increase in artillery shelling by the Russian-led militants in Donbas as attempts to provoke the Ukrainian army.[143][144] On 21 February, Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB) announced that Ukrainian shelling had destroyed an FSB border facility 150 metres from the Russia–Ukraine border in Rostov Oblast.[145] The Luhansk thermal power station in the Luhansk People's Republic was also shelled by unknown forces.[146] Ukrainian news stated that it was forced to shut down as a result.[147]

On 21 February, the press service of the Southern Military District announced that Russian forces had in the morning that day killed a group of five saboteurs near the village of Mityakinskaya, Rostov Oblast, that had penetrated the border from Ukraine in two infantry fighting vehicles, the vehicles having been destroyed.[148] Ukraine denied being involved in both incidents and called them a false flag.[149][150] Additionally, two Ukrainian soldiers and a civilian were reported killed by shelling in the village of Zaitseve, 30 kilometres (19 mi; 16 nmi) north of Donetsk.[151] Several analysts, including the investigative website Bellingcat,[152] published evidence that many of the claimed attacks, explosions, and evacuations in Donbas were staged by Russia.[153][154][155]

Escalation (21–23 February)

On 21 February, following the recognition of the Donetsk and Luhansk people's republics, Putin directed the deployment of Russian troops, including mechanised forces, into Donbas in what Russia referred to as a "peacekeeping mission".[156][157] Russia's military said it killed five Ukrainian "saboteurs" who crossed the border into Russia, a claim strongly denied by Ukrainian foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba.[158] Later that day,[159] several independent media outlets confirmed that Russian forces were entering Donbas.[160][161][162] The 21 February intervention in Donbas was widely condemned by the UN Security Council and did not receive any support.[163] Kenya's ambassador Martin Kimani compared Putin's move to colonialism and said: "We must complete our recovery from the embers of dead empires in a way that does not plunge us back into new forms of domination and oppression."[164]

On 22 February, US president Joe Biden stated that "the beginning of a Russian invasion of Ukraine" had occurred. Jens Stoltenberg, the secretary general of NATO, and Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau said that "further invasion" had taken place. Kuleba stated: "There's no such thing as a minor, middle or major invasion. Invasion is an invasion." Josep Borrell, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, stated that "Russian troops [had arrived] on Ukrainian soil" in what was "[not] a fully-fledged invasion".[165][166] On the same day, the Federation Council unanimously authorised Putin to use military force outside Russia.[65] In turn, Zelenskyy ordered a conscription of Ukraine's reservists, while not committing to general mobilisation at that time.[167]

On 23 February, the Verkhovna Rada proclaimed a 30-day nationwide state of emergency, excluding the occupied territories in Donbas, which took effect at midnight. The parliament also ordered the mobilisation of all reservists of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.[168][169][170] On the same day, Russia began to evacuate its embassy in Kyiv and also lowered the Russian flag from the top of the building.[171] The websites of the Ukrainian parliament and government, along with banking websites, were hit by DDoS attacks.[172]

By night on 23 February, Zelenskyy made a televised speech in which he addressed the citizens of Russia in Russian and pleaded with them to prevent war.[173][174][175] In the speech, Zelenskyy refuted claims of the Russian government about the presence of neo-Nazis in the Ukrainian government and stated that he had no intention of attacking the Donbas region.[176][177]

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said that the leaders of the Donetsk and Luhansk people's republics sent a letter to Putin appealing for military support from Russia "in repelling the aggression of the Ukrainian armed forces", with the letter claiming that Ukrainian government shelling had caused civilian deaths.[178] In response to the appeal, Ukraine requested an urgent UN Security Council meeting.[179] Another security council meeting was convened on 23 February, 21:30 (UTC-5).[180] Russia, which held the presidency of the UN Security Council for February 2022 and has veto power as one of five permanent members,[181][182] launched its invasion of Ukraine during the emergency meeting called to defuse the crisis. UN Secretary-General António Guterres pleaded with Putin: "Give peace a chance."[181]

Invasion

This section appears to be slanted towards recent events. (March 2022) |

24 February

Shortly before 06:00 Moscow Time (UTC+3) on 24 February, Putin announced that he had made the decision to launch a "special military operation" in eastern Ukraine.[183][184] In his address, Putin claimed there were no plans to occupy Ukrainian territory and that he supported the right of the peoples of Ukraine to self-determination.[185] Putin also stated that Russia sought the "demilitarisation and denazification" of Ukraine.[186][187] The Russian Ministry of Defence asked air traffic control units of Ukraine to stop flights, and the airspace over Ukraine was restricted to non-civilian air traffic, and the whole area was deemed an active conflict zone by the European Union Aviation Safety Agency.[188][189]

Within minutes of Putin's announcement, explosions were reported in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odessa, and the Donbas.[190] Ukrainian officials said that Russia had landed troops in Mariupol and Odessa and launched cruise and ballistic missiles at airfields, military headquarters, and military depots in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Dnipro.[191][192][193] Military vehicles entered Ukraine through Senkivka, at the point where Ukraine meets Belarus and Russia, at around 6:48 am local time.[194] A video captured Russian troops entering Ukraine from Russian-annexed Crimea.[195][196]

The Kremlin planned to initially target artillery and missiles at command and control centres and then send fighter jets and helicopters to quickly gain air superiority.[197] The Center for Naval Analyses said that Russia would create a pincer movement to encircle Kyiv and envelop Ukraine's forces in the east, with the Center for Strategic and International Studies identifying three axes of advance: from Belarus in the north, from Donetsk, and from Crimea in the south.[197] The US said it believed that Russia intended to "decapitate" Ukraine's government and install their own,[198] with US intelligence officials believing that Kyiv would fall within 96 hours given circumstances on the ground.[199]

According to former Ukrainian Deputy Minister of Internal affairs, Anton Herashchenko, now serving as an official government advisor, just after 06:30 (UTC+2), Russian forces were invading via land near the city of Kharkiv[200] and large-scale amphibious landings were reported in the city of Mariupol.[174][201][202] At 07:40, troops were also entering the country from Belarusian territory.[203] The Ukrainian Border Force reported attacks on sites in Luhansk, Sumy, Kharkiv, Chernihiv, and Zhytomyr, as well as from Crimea.[204] The Ukrainian interior ministry reported that Russian forces captured the villages of Horodyshche and Milove in Luhansk.[174] The Ukrainian Centre for Strategic Communication reported that the Ukrainian army repelled an attack near Shchastia (near Luhansk) and retook control of the town, claiming nearly 50 casualties from the Russian side.[205]

After being offline for an hour, the Ukrainian Defence Ministry's website was restored, and declared that it had shot down five planes and one helicopter in Luhansk.[206] Shortly before 07:00 (UTC+2), Zelenskyy announced the introduction of martial law in Ukraine.[207] Zelenskyy also announced that Russia–Ukraine relations were being severed, effective immediately.[208] Russian missiles targeted Ukrainian infrastructure, including Boryspil International Airport, Ukraine's largest airport, 29 km (18 mi) east of Kyiv.[209]

A military unit in Podilsk was attacked by Russian forces, resulting in six deaths and seven wounded.[210] Another person was killed in the city of Mariupol. A house in Chuhuiv was damaged by Russian artillery; its occupants were injured and one boy died.[211][212] Eighteen people were killed by Russian bombing in the village of Lipetske in Odesa Oblast.[212]

At 10:00 (UTC+2), it was reported during the briefing of the Ukrainian presidential administration that Russian troops had invaded Ukraine from the north (up to 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) south of the border). Russian troops were said to be active in Kharkiv Oblast, in Chernihiv Oblast, and near Sumy.[213] Zelenskyy's press service also reported that Ukraine had repulsed an attack in Volyn Oblast.[214] At 10:30 (UTC+2), the Ukrainian Defence Ministry reported that Russian troops in Chernihiv Oblast had been stopped, a major battle near Kharkiv was in progress, and Mariupol and Shchastia had been fully reclaimed.[215]

The Ukrainian military claimed that six Russian planes, two helicopters, and dozens of armoured vehicles had been destroyed.[215] Russia denied having lost any aircraft or armoured vehicles.[216] Ukrainian commander-in-chief Valerii Zaluzhnyi published photos of two captured Russian soldiers saying they were from the Russian 423rd Guards Yampolsky Motor Rifle Regiment (military unit 91701).[217] Russia's 74th Guards Motor Rifle Brigade recon platoon surrendered[191] near Chernihiv.[218]

In the Battle of Antonov Airport, Russian airborne troops seized the Hostomel Airport in Hostomel, a suburb of Kyiv, after being transported by helicopters early in the morning; a Ukrainian counteroffensive to recapture the airport was launched later in the day.[219][220] The Rapid Response Brigade of the Ukrainian National Guard stated that it had fought at the airfield, shooting down three of 34 Russian helicopters.[221]

Belarus allowed Russian troops to invade Ukraine from the north. At 11:00 (UTC+2), Ukrainian border guards reported a border breach in Vilcha (Kyiv Oblast), and border guards in Zhytomyr Oblast were bombarded by Russian rocket launchers (presumably BM-21 Grad).[212] A helicopter without markings reportedly bombed Slavutych border guards position from Belarus.[222] At 11:30 (UTC+2), a second wave of Russian missile bombings targeted the cities of Kyiv, Odessa, Kharkiv, and Lviv. Heavy ground fighting was reported in the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts.[223]

By 12:04 (UTC+2), Russian troops advancing from Crimea moved towards the city of Nova Kakhovka in Kherson Oblast.[224] Later that day, Russian troops entered the city of Kherson and took control of the North Crimean Canal, which would allow them to resume water supplies for the peninsula.[225]

At 13:00 and 13:19 (UTC+2), Ukrainian border guards and Armed Forces reported two new clashes—near Sumy ("in the direction of Konotop") and Starobilsk (Luhansk Oblast).[212] At 13:32 (UTC+2), Valerii Zaluzhnyi reported four ballistic missiles launched from the territory of Belarus in a southwestern direction.[212] Several stations of Kyiv Metro and Kharkiv Metro were used as bomb shelters for the local population.[212] A local hospital in Vuhledar (Donetsk Oblast) was reported to have been bombed with four civilians dead and 10 wounded (including 6 physicians).[212]

At 16:00 (UTC+2), Zelenskyy said that fighting between Russian and Ukrainian forces had erupted in the ghost cities of Chernobyl and Pripyat.[226] By around 18:20 (UTC+2), the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant was under Russian control,[227][228][229] as were the surrounding areas.[230][231][226]

At 16:18 (UTC+2), Vitali Klitschko, the mayor of Kyiv, proclaimed a curfew lasting from 22:00 to 07:00.[232]

At 22:00 (UTC+2), the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine announced that Russian forces had captured Snake Island following a naval and air bombardment of the island.[233] All thirteen border guards on the island were assumed to have been killed in the bombardment, after refusing to surrender to a Russian warship; a recording of the guards refusing an offer to surrender went viral on social media. President Zelenskyy announced that the presumed-dead border guards would be posthumously granted the title of Hero of Ukraine, the country's highest honour.[234][235] Seventeen civilians were confirmed killed, including thirteen killed in Southern Ukraine,[236] three in Mariupol, and one in Kharkiv.[237] Zelenskyy stated that 137 Ukrainian citizens (both soldiers and civilians) died on the first day of the invasion.[238]

Shortly after 23:00 (UTC+2), President Zelenskyy ordered a general mobilisation of all Ukrainian males between 18 and 60 years old; for the same reason, Ukrainian males from that age group were banned from leaving Ukraine.[72]

25 February

Around 04:00 (UTC+2) local time, Kyiv was rocked with two explosions from cruise and ballistic missiles.[239] The Ukrainian government said that it had shot down an enemy aircraft over Kyiv, which then crashed into a residential building, setting it on fire.[240] It was later confirmed that the aircraft was a Ukrainian Su-27.[29][clarification needed]

Independent military analysts noted that Russian forces in the north of the country appeared to have been heavily engaged by the Ukrainian military. Russian units were attempting to encircle Kyiv and advance into Kharkiv but were bogged down in heavy fighting, with social media images suggesting that some Russian armoured columns had been ambushed. In contrast, Russian operations in the east and south were more effective. The best trained and equipped Russian units were positioned outside Donbas in the southeast and appeared to have maneuvered around the prepared defensive trenches and attacked in the rear of Ukrainian defensive positions. Meanwhile, Russian military forces advancing from Crimea were divided into two columns, with analysts suggesting that they may have been attempting to encircle and entrap the Ukrainian defenders at Donbas, forcing the Ukrainians to abandon their prepared defences and fight in the open.[241]

On the morning of 25 February, Zelenskyy accused Russia of targeting civilian sites;[242] Ukrainian Interior Ministry representative Vadym Denysenko said that 33 civilian sites had been hit in the previous 24 hours.[243]

Ukraine's Defence Ministry stated that Russian forces had entered the district of Obolon, Kyiv, and were approximately 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) from the Verkhovna Rada building.[234] Some Russian forces had entered northern Kyiv, but had not progressed beyond that.[244] Russia's Spetsnaz troops infiltrated the city with the intention of "hunting" government officials.[245] A Russian tank from a military column was filmed crushing a civilian car in northern Kyiv, veering across the road to crush it. The car driver, an elderly man, survived and was helped out by locals.[246][247][248]

Ukrainian authorities reported that a non-critical increase in radiation, exceeding control levels, had been detected at Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant after Russian troops had occupied the area, saying that this was due to the movement of heavy military vehicles lifting radioactive dust into the air.[249][250] Russia claimed that it was defending the plant from nationalistic and terrorist groups, and that staff were monitoring radiation levels at the site.[234]

The mayor of Horlivka in the Russian-backed Donetsk People's Republic reported that a munition fired by the Ukrainian military hit a local school building, killing two teachers.[251]

As Russian troops approached Kyiv, Zelenskyy asked residents to prepare Molotov cocktails to "neutralise" the enemy. Putin meanwhile called on the Ukrainian military to overthrow the government.[252][253] Ukraine distributed 18,000 guns to Kyiv residents who expressed a willingness to fight and deployed the Territorial Defence Forces, the reserve component of the Ukrainian military, for the defence of Kyiv.[254] The Defence Ministry also announced that all Ukrainian civilians were eligible to volunteer for military service regardless of their age.[191]

By the evening, the Pentagon stated that Russia had not established air supremacy of Ukrainian airspace, which US analysts had predicted would happen quickly after hostilities began. Ukrainian air defence capabilities had been degraded by Russian attacks, but remained operational. Military aircraft from both nations continued to fly over Ukraine.[255] The Pentagon also said that Russian troops were also not advancing as quickly as either US intelligence or Moscow believed they would, that Russia had not taken any population centres, and that Ukrainian command and control was still intact. The Pentagon warned that Russia had sent into Ukraine only 30 percent of the 150,000–190,000 troops it had massed at the border.[256]

Reports circulated of a Ukrainian missile attack against the Millerovo air base in Russia, to prevent the base being used to provide air support to Russian troops in Ukraine.[257]

Zelenskyy indicated that the Ukrainian government was not "afraid to talk about neutral status".[258] On the same day, President Putin indicated to Xi Jinping, the Chinese paramount leader and general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, that "Russia is willing to conduct high-level negotiations with Ukraine".[259]

26 February

At 00:00 (UTC), heavy fighting was reported to the south of Kyiv, near the city of Vasylkiv and its air base.[260] The Ukrainian General Staff claimed that a Ukrainian Su-27 fighter had shot down a Russian Il-76 transport plane carrying paratroopers near the city.[261] Vasylkiv mayor Natalia Balasinovich said her city had been successfully defended by Ukrainian forces and the fighting was ending.[262]

Around 03:00, more than 48 explosions in 30 minutes were reported around Kyiv, as the Ukrainian military was reported to be fighting near the CHP-6 power station in the northern neighbourhood of Troieshchyna.[263] BBC News reported the attack may be an attempt to cut off electricity to the city. Heavy fighting was reported near the Kyiv Zoo and the Shuliavka neighbourhood. Early on 26 February, the Ukrainian military said it had repelled a Russian attack on an army base located on Peremohy Avenue, a main road in Kyiv;[264] it also claimed to have repelled a Russian assault on the city of Mykolaiv on the Black Sea.[265] American officials said a Russian Il-76 transport plane had been shot down by Ukrainian forces near Bila Tserkva, about 80 kilometres (50 mi) south of Kyiv.[22][266] President Zelenskyy, remaining in Kyiv, had refused US offers of evacuation, instead requesting more ammunition for Ukrainian troops.[267]

Hundreds of casualties were reported during overnight fighting in Kyiv, where shelling destroyed an apartment building, bridges, and schools.[22] The Russian defence ministry said it had captured Melitopol, near the Sea of Azov,[268] although UK minister James Heappey questioned this claim.[269] At 11:00, the Ukrainian General Staff reported that its aircraft had conducted 34 sorties in the past 24 hours, indicating that Russia had continued to, unexpectedly, fail to gain air superiority.[270]

By the afternoon, most of the Russian forces that had amassed around Ukraine were fighting in the country. Mayor Klitschko of Kyiv imposed a curfew from 5 p.m. Saturday until 8 a.m. Monday, warning that anyone outside during that time would be considered enemy sabotage and reconnaissance groups.[271] Internet connections were disrupted in parts of Ukraine, particularly in the south and east.[272] In response to a request from Mykhailo Fedorov, the Vice-Prime Minister of Ukraine, Elon Musk announced that he had turned on his Starlink service in Ukraine, with "more terminals en route".[273][274]

Ukrainian Interior Ministry representative Vadym Denysenko stated that Russian forces had advanced further towards Enerhodar and the Zaporizhia Nuclear Power Plant. He stated that they were deploying Grad missiles there and warned that they may attack the plant.[275] The Zaporizhia Regional State Administration stated that the Russian forces advancing on Enerhodar had later returned to Bolshaya Belozerka, a village located 30 kilometres (19 mi) from the city, on the same day.[276]

A Japanese-owned cargo ship, the MV Namura Queen with 20 crew members onboard was struck by a Russian missile in the Black Sea. A Moldovan ship, MV Millennial Spirit, was also shelled by a Russian warship, causing serious injuries.[277]

Ramzan Kadyrov, the head of the Chechen Republic, confirmed that the Kadyrovtsy, units loyal to the Chechen Republic, had been deployed into Ukraine as well.[278]

CNN obtained footage of a Russian TOS-1 system, which carries thermobaric weapons, near the Ukrainian border.[279] Western officials warned such weapons would cause indiscriminate violence.[280] The Russian military had used these kind of weapons in the First Chechen War in the 1990s.[281]

A six-year-old boy was killed and multiple others were wounded when artillery fire hit the Okhmatdyt Children's Hospital in Kyiv.[282] The Ukrainian military claimed to have blown up a convoy of 56 tankers in Chernihiv Oblast carrying diesel for Russian forces.[283]

By the end of the day, Russian forces had failed in their attempts to encircle and isolate Kyiv, despite mechanised and airborne attacks.[284] The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Russia had committed its operational northern reserve of 17 battalion tactical groups (BTGs) after Ukrainian forces halted the advance of 14 BTGs to the north of Kyiv.[270] Russia temporarily abandoned attempts to seize Chernihiv and Kharkiv after attacks were repelled by determined Ukrainian resistance, and bypassed those cities to continue towards Kyiv.[284] In the south, Russia took Berdiansk and threatened to encircle Mariupol.[270]

The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) said that poor planning and execution was leading to morale and logistical issues for the Russian military in northern Ukraine.[284] US and UK officials reported that Russian forces faced shortages of gasoline and diesel, leading to tanks and armoured vehicles stalling and slowing their advance.[285] Videos also emerged online of Russian tanks and armoured personnel carriers, or APCs, stranded on the roadside.[286] Russia continued to not use its full arsenal; the ISW said this was likely to avoid the diplomatic and public relations consequences of mass civilian casualties, as well as to avoid creating rubble that would impede the advance of its own forces.[270]

27 February

Overnight, a gas pipeline outside Kharkiv was reported to have been blown up by a Russian attack,[287] while an oil depot in the village of Kriachky near Vasylkiv ignited after being hit by missiles.[288] Heavy fighting near the Vasylkiv air base prevented firefighters from tackling the blaze.[289] Also at night, it was reported that a group of Ukrainian Roma (gypsies) had seized a Russian tank in Liubymivka, close to Kakhovka, in the Kherson Oblast.[290][291] Furthermore, the Presidential Office stated that Zhuliany Airport was also bombed.[292] Russian-backed separatists in Luhansk province said that an oil terminal in the town of Rovenky was hit by a Ukrainian missile.[293] The State Emergency Service of Ukraine rescued 80 people from a nine-story residential building in Kharkiv after Russian artillery hit the building, extensively damaging it and killing a woman.[294]

Nova Kakhovka's mayor, Vladimir Kovalenko, confirmed that the city had been seized by Russian troops, and he accused them of destroying the settlements of Kozatske and Vesele.[295] Russian troops also entered Kharkiv, with fighting taking place in the city streets, including in the city centre.[296] At the same time, Russian tanks started pushing into Sumy.[297] Meanwhile, the Russian Defense Ministry announced that Russian forces had completely surrounded Kherson and Berdiansk, in addition to capturing Henichesk and Kherson International Airport in Chernobaevka.[298][299] By the early afternoon, Kharkiv Oblast governor Oleh Synyehubov stated that Ukrainian forces had regained full control of Kharkiv,[300] and Ukrainian authorities said that dozens of Russian troops in the city had surrendered.[301] Hennadiy Matsegora, the mayor of Kupiansk, later agreed to hand over control of the city to Russian forces.[302]

Putin ordered Russian nuclear forces on a high alert, a "special regime of combat duty", in response to what he called "aggressive statements" by NATO members.[303][304][305] This statement was met with harsh criticism from NATO, the EU, and the United Nations (UN); NATP Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg described it as being "dangerous and irresponsible", while UN official Stéphane Dujarric called the idea of a nuclear war "inconceivable".[306][307]

Ukraine said that it would send a delegation to meet with a Russian delegation for talks in Gomel, Belarus. Zelenskyy's office said that they agreed to meet without preconditions.[308][309][310] Zelenskyy also said that he talked by telephone with Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko and stated that he was promised that Belarusian troops would not be sent to Ukraine.[311]

According to the intelligence analyst firm Rochan Consulting, Russia had been able to connect Crimea with areas in eastern Ukraine held by pro-Russian forces by besieging Mariupol and Berdiansk.[312] Oleksiy Arestovych, an advisor to President Zelenskyy, stated that Berdiansk had been captured by Russian forces.[313] The main Russian force from the Crimea was advancing north towards Zaporizhzhia, while a Russian force on the east bank of the Dnipro threatened Mykolaiv.[314]

Russian forces were pushed back in Bucha and Irpin to the north-west of Kyiv. According to UK military intelligence, Russian mechanised forces had bypassed Chernihiv as they moved towards Kyiv.[315] Luhansk Oblast governor Serhiy Haidai accused Russian forces of destroying Stanytsia Luhanska and Shchastia before capturing them, while Donetsk Oblast governor Pavlo Kyrylenko also accused them of destroying Volnovakha.[316]

The ISW said that Russian forces in northern Ukraine had likely conducted an "operational pause" starting the previous day in order to deploy additional forces and supplies; Russian military resources not previously part of the invasion force were being moved toward Ukraine in anticipation of a more difficult conflict than initially expected.[314]

28 February

Fighting took place around Mariupol throughout the night.[317] On the morning of 28 February, the UK defence ministry said that most Russian ground forces remained over 30 km (19 mi) north of Kyiv, having been slowed by Ukrainian resistance at Hostomel Airport. It also said that fighting was taking place near Chernihiv and Kharkiv, and that both cities remained under Ukrainian control.[318] Maxar Technologies released satellite images that showed a Russian column, including tanks and self-propelled artillery, traveling toward Kyiv.[319] The firm initially stated that the convoy was approximately 27 kilometres (17 mi) long, but clarified later that day that the column was actually more than 64 kilometres (40 mi) in length.[319]

The Russian Defense Ministry announced the capture of Enerhodar, in addition to the surroundings of Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant. Ukraine denied that it had lost control of the plant.[320] Enerhodar's mayor Dmitri Orlov denied that the city and the plant had been captured.[321]

The Times reported that the Wagner Group had been redeployed from Africa to Kyiv, with orders to assassinate Zelenskyy during the first days of the Russian invasion.[322] Both the Ukrainian and Russian governments meanwhile accused each other of using human shields.[323][324]

Arestovych claimed that more than 200 Russian military vehicles had been destroyed or damaged on the highway between Irpin and Zhytomyr by 14:00 EET.[325] Ihor Terekhov, the mayor of Kharkiv, stated that nine civilians were killed and 37 were wounded due to Russian shelling on the city during the day.[326] Oksana Markarova, the Ukrainian ambassador to the US, accused Russia of using a vacuum bomb.[327]

Talks between Ukrainian and Russian representatives in Gomel, Belarus, ended without a breakthrough.[328] As a condition for ending the invasion, Putin demanded Ukraine's neutrality, "denazification" and "demilitarisation", and recognition of Crimea, which had been annexed by Russia, as Russian territory.[329]

Russia increased strikes on Ukrainian airfields and logistics centres, particularly in the west, in an apparent attempt to ground the Ukrainian air force and disrupt resupply from nations to the west. In the north, the ISW called the decision to use heavy artillery in Kharkiv "a dangerous inflection." Additional Russian forces and logistics columns in southern Belarus appeared to be maneuvering to support a Kyiv assault.[330] An analyst with the Royal United Services Institute stated that the Ukrainian regular army is no longer functioning in formations but in largely fixed defenses, and was increasingly integrated with Territorial Defense Forces and armed volunteers.[331]

1 March

According to Dmytro Zhyvytskyi, the governor of Sumy Oblast, more than 70 Ukrainian soldiers had been killed during Russian shelling of a military base in Okhtyrka.[332] A Russian missile later hit the regional administration building on Freedom Square during a bombardment of Kharkiv, killing at least ten civilians, and wounding 35 others.[333][334] In southern Ukraine, the city of Kherson was reported to be under attack by Russian forces.[335] The Ukrainian government announced it would sell war bonds to fund its armed forces.[336]

The Ukrainian parliament stated that the Armed Forces of Belarus had joined Russia's invasion and were in Chernihiv Oblast, north-east of the capital. UNIAN reported that a column of 33 military vehicles had entered the region. The US disagreed with these claims, saying that there was "no indication" that Belarus had invaded.[337] Hours prior, Belarus's president Lukashenko said that Belarus would not join the war.[338]

After Russia's Defense Ministry announced that it would hit targets to stop "information attacks", missiles struck broadcasting infrastructure for the primary television and radio transmitters in Kyiv, taking TV channels off the air.[339] Ukrainian officials said the attack killed five people and damaged the nearby Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center, Ukraine's main Holocaust memorial.[340][341]

An official from the US Department of Defense stated that Russian forces had captured Berdiansk and Melitopol.[342]

2 March

The Ukrainian military reported a Russian paratrooper assault on northwest Kharkiv, where a military hospital came under attack.[343] Zhyvytskyi stated that Russian forces had captured Trostianets after entering it at 01:03.[344]

Arestovych stated that the Ukrainian forces had went on the offensive for the first time during the war, advancing towards Horlivka.[345]

Leadership of Putin and Zelenskyy

The leadership of the presidents of Russia and Ukraine was a prominent factor in the conflict. According to the portrayal in Western media, as the autocratic ruler of Russia,[346] Putin was effectively in sole control of the country's policy and was the sole architect of the war with Ukraine. His leadership was characterised by his failures to anticipate the will of the Ukrainian people to oppose the invasion, the worldwide backlash, and the poor performance of his own forces.[347][348][349] Putin swiftly became a pariah, and was shunned by much of the global community.[350] This contrasted with the leadership of Zelenskyy, who quickly became a national hero,[351][352] uniting the Ukrainian people and rising from obscurity to become an international icon.[353][354]

In the beginning of the conflict, Zelenskyy refused to leave the capital, pledging to stay and fight.[355] When the US offered to evacuate him, Zelenskyy replied that he needed ammunition and not a ride.[356] He used social media effectively, posting selfies of himself walking the streets of Kyiv as the city was under attack to prove that he was still alive.[357][358] Zelenskyy was highly effective in lobbying his allies for support. He appeared before numerous gatherings of international leaders, telling a conference of European leaders that this might be the last time they would see him,[359] and appearing before the European Parliament where he earned a standing ovation.[360]

Foreign military support to Ukraine

Under the leadership of Viktor Yanukovych, the Ukrainian military had deteriorated. It was further weakened following Yanukovych's fall and his succession by West-looking leaders. Subsequently, a number of Ukraine's allies[who?] began providing military aid to rebuild its military forces. This assisted the Ukrainian military to improve its quality, with the Ukrainian army achieving noticeable successes against Russian proxy forces in Donbas.[citation needed] Notably, the Ukrainian armed forces have begun acquiring Turkey's Bayraktar TB2 unmanned combat aerial vehicles since 2019,[361] which was first used in October 2021 to target Russian separatist artillery position in Donbas.[362]

As Russia began building up its equipment and troops on Ukraine's borders, NATO member states increased the rate of weapons delivery.[363] US president Joe Biden used Presidential Drawdown Authorities in August and December 2021 to provide $260 million in aid. These included deliveries of FGM-148 Javelins and other anti-armour weapons, small arms, various calibres of ammunition, and other equipment.[364][365][366]

Following the invasion, nations began making further commitments of arms deliveries. Belgium,[367] the Czech Republic,[368] Estonia,[369] France, Greece,[370] the Netherlands, Portugal,[371] and the UK announced that they would send supplies to support and defend the Ukrainian military and government.[372] On 24 February, Poland delivered some military supplies to Ukraine, including 100 mortars, various ammunition, and over 40,000 helmets.[373][374] While some of the 30 members of NATO are sending weapons, NATO as an organisation is not.[75]

In January 2022, Germany ruled out sending weapons to Ukraine and prevented Estonia, through export controls on German-made arms, from sending former East German D-30 howitzers to Ukraine.[375] Germany announced it was sending 5,000 helmets and a field hospital to Ukraine,[376] to which Kyiv mayor Vitali Klitschko derisively responded: "What will they send next? Pillows?"[377] On 26 February, in a reversal of its previous position, Germany approved the Netherlands' request to send 400 rocket-propelled grenades to Ukraine,[378] as well as 500 Stinger missiles and 1,000 anti-tank weapons from its own supplies.[379]

On 27 February, the EU agreed to purchase weapons for Ukraine collectively. EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell stated that it would purchase €450 million (US$502 million) in lethal assistance and an additional €50 million ($56 million) in non-lethal supplies. Borrell said that EU defence ministers still needed to determine the details of how to purchase the materiel and transfer it to Ukraine, but that Poland had agreed to act as a distribution hub.[380][381][382] Borrell also stated that they intended to supply Ukraine with fighter jets that they are already able to pilot. These would not be paid for through the €450 million assistance package. Poland, Bulgaria, and Slovakia have MiG-29s and Slovakia also has Su-25s, which are fighter jets that Ukraine already flies and can be transferred without pilot training.[383] On 1 March, Poland, Slovakia, and Bulgaria confirmed they would not provide fighter jets to Ukraine.[384]

On 26 February, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced that he had authorised $350 million in lethal military assistance, including "anti-armor and anti-aircraft systems, small arms and various caliber munitions, body armor, and related equipment".[385][386] Russia claimed that US drones gave intelligence to the Ukrainian navy to help target its warships in the Black Sea, which the US denied.[387] On 27 February, Portugal announced that it would send H&K G3 automatic rifles and other military equipment.[371] Sweden and Denmark both decided to send 5,000 and 2,700 anti-tank weapons, respectively, to Ukraine.[388][389] Denmark also provided parts from 300 non-operational Stinger missiles, that the US would first help make operational.[390]

The Norwegian government, initially saying it would not send weapons to Ukraine but would send other military equipment like helmets and protective gear,[391][392][393] announced on the evening of 28 February that it would also donate up to 2,000 M72 LAW anti-tank weapons to Ukraine.[394][395][396] In a similarly major policy shift for a neutral country, Finland announced that it would send 2,500 assault rifles together with 150,000 rounds, 1,500 single-shot antitank weapons and 70,000 combat-ration packages, to add to the bulletproof vests, helmets, and medical supplies already announced.[397]

Humanitarian impact

Casualties

Refugees

Due to the continued military build-up along the Ukrainian border, many neighbouring governments and aid organisations had been preparing for a potential mass displacement event in the weeks prior to the invasion. The Ukrainian Defence Minister estimated in December 2021 that an invasion could potentially force between three and five million people to flee their homes.[398]

It was reported that Ukrainian border guards did not permit a number of non-Ukrainians (many of them foreign students stuck in the country) to cross the border into neighbouring safe nations, claiming that priority was being given to Ukrainian citizens to cross first. The Ukrainian Foreign Minister said there were no restrictions on foreign citizens leaving Ukraine, and that the border force had been told to allow all foreign citizens to leave.[399][400] According to Bal Kaur Sandhu, General Secretary of Khalsa Aid, Indian students trying to leave Ukraine faced serious difficulties and discrimination when attempting to cross the border, were subjected to violence and "have quite verbally been told that your government is not supporting us, we are not supporting you."[401]

Numbers and countries

According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, more than a half-million Ukrainians fled the country in the first four days after the invasion;[402] about 281,000 went to Poland, almost 85,000 to Hungary, at least 36,390 to Moldova, more than 32,500 to Romania, 30,000 to Slovakia, and about 34,600 to various other countries.[402]

On 24 February, the government of Latvia approved a contingency plan to receive and accommodate approximately 10,000 refugees from Ukraine,[403] and two days later the first refugees, assisted by the Latvian Samaritan Association, began arriving. Several non-governmental organizations, municipalities, schools and institutions also pledged to provide accommodation.[404] On 27 February, around 20 volunteer professional drivers departed to Lublin with donated supplies, bringing Ukrainian refugees to Latvia on their way back.[405] To facilitate border crossings, Poland and Romania lifted COVID-19 entry rules.[406][407]

The government of Hungary announced on 24 February that all persons crossing the border from Ukraine, those without a travel document and arriving from third countries would also be admitted after appropriate screening.[408] Prime Minister Viktor Orbán said that Hungary is a "friendly place" for people arriving from Ukraine.[409] Many of the Ukrainians who fled to Hungary were Transcarpathian Hungarians; none of them requested any form of protection.[410] Men between the age of 18 and 60 were denied exit from Ukraine.[292]

Ukrainian refugees started crossing into Romania as well. Most of them entered through Siret in Suceava County.[411] In the first three days after the invasion, 31,000 Ukrainians entered Romania, of which only 111 requested some form of protection. Many used the Romanian or Ukrainian passport they held, preferring not to seek asylum for the time being. Romania's Interior Ministry approved on 26 February the installation of the first mobile camp near the Siret customs.[412]

А large group of refugees was also expected in Bulgaria.[413] Various municipalities announced their intention to provide accommodation for Bulgarians and Ukrainians fleeing the country, and began to modify and/or build housing for new arrivals.[414]

On 26 February, Slovakia announced that it would give money to people who supported Ukrainian refugees. Over the previous 24 hour period, Slovakia had received over 10,000 refugees, mostly women and children.[415]

International organizations

On 27 February, the EU agreed to take in Ukrainian refugees for up to three years without asking them to apply for asylum.[416] EU ministers asked Home Affairs Commissioner Ylva Johansson to prepare plans for invoking the Temporary Protection Directive, which would be the first time that the directive has ever been invoked.[417] Most countries of the Schengen Area, including Poland, Germany, and Switzerland, have waived passport requirements for Ukrainians fleeing the war zone.[418]

War crimes

The invasion of Ukraine was considered to have violated the Charter of the United Nations and constituted a crime of aggression according to international criminal law, raising the possibility that the crime of aggression could be prosecuted under universal jurisdiction.[419][420][421] The invasion also violated the Rome Statute, which prohibits "the invasion or attack by the armed forces of a State of the territory of another State, or any military occupation, however temporary, resulting from such invasion or attack, or any annexation by the use of force of the territory of another State or part thereof". However, Ukraine had not ratified the Rome Statute and Russia withdrew its signature from it in 2016.[422]

On 25 February, Amnesty International said that it had collected and analysed evidence showing that Russia had violated international humanitarian law, including attacks that could amount to war crimes; it also said that Russian claims to be only using precision-guided weapons were false.[423][424] Amnesty and Human Rights Watch said that Russian forces had carried out indiscriminate attacks on civilian areas and strikes on hospitals, including firing a 9M79 Tochka ballistic missile with a cluster munition warhead towards a hospital in Vuhledar, which killed four civilians and wounded ten others, including six healthcare staff.[425][426] Dmytro Zhyvytskyi, the governor of Sumy Oblast, said that at least six Ukrainians, including a seven-year-old girl, had died in a Russian attack on Okhtyrka on 26 February, and that a kindergarten and orphanage had been hit. Ukrainian foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba called for the International Criminal Court (ICC) to investigate the incident.[427]

On 27 February, Ukraine filed a lawsuit against Russia before the International Court of Justice, accusing Russia of violating the Genocide Convention by falsely claiming genocide as a pretext for military operations against Ukraine.[428] On 28 February, Karim Ahmad Khan, the chief prosecutor of the ICC, said there was a "reasonable basis" for allegations of war crimes and crimes against humanity.[335]

On 28 February, a diplomatic crisis within Greece–Russia relations was sparked when the latter's air forces bombarded two villages of ethnic minority Greeks in Ukraine near Mariupol, killing twelve Greeks.[429] Greece protested strongly, summoning the Russian ambassador. French president Emmanuel Macron and US Secretary of State Antony Blinken,[430] along with Germany,[431] and other countries, expressed their condolences to Greece. Russian authorities denied responsibility. Greek authorities stated that they had evidence of Russian involvement.[432] In response, Greek prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis announced that his country would send defensive military equipment and humanitarian aid to support Ukraine.[370][433]

On 28 February, Amnesty and Human Rights Watch denounced the use of cluster munitions and thermobaric weapons by Russian invasion forces in Ukraine. The use of cluster munitions in war is prohibited by the Convention on Cluster Munitions of 2008, though Russia and Ukraine are not part of such convention.[434]

On 1 March, President Zelenskyy said there was evidence that civilian areas had been targeted during a Russian artillery bombardment of Kharkiv earlier that day, and described it as a war crime.[335]

Ramifications

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (March 2022) |

Sanctions

Western countries and others began imposing limited sanctions on Russia when it recognised the independence of Donbas. With the commencement of attacks on 24 February, large numbers of additional countries began applying sanctions with the aim of crippling the Russian economy. The sanctions were wide-ranging, targeting individuals, banks, businesses, monetary exchanges, bank transfers, exports, and imports.[436][437][438] In a 22 February speech,[439] US president Joe Biden announced restrictions against four Russian banks, including V.E.B., as well as on corrupt billionaires close to Putin.[440][441]

The US also instituted export controls, a novel sanction focused on restricting Russian access to high-tech components, both hardware and software, made with any parts or intellectual property from the US. The sanction required that any person or company that wanted to sell technology, semiconductors, encryption software, lasers, or sensors to Russia request a licence, which by default was denied. The enforcement mechanism involved sanctions against the person or company, with the sanctions focused on the shipbuilding, aerospace, and defence industries.[442]

UK prime minister Boris Johnson announced that all major Russian banks would have their assets frozen and be excluded from the UK financial system, and that some export licenses to Russia would be suspended.[210] He also introduced a deposit limit for Russian citizens in UK bank accounts, and froze the assets of over 100 additional individuals and entities.[443] German chancellor Olaf Scholz indefinitely blocked the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline in response to the Russian invasion of Donbas.[444] Nord Stream 2 has become insolvent as a result.[445]

The foreign ministers of the Baltic states called for Russia to be cut off from SWIFT, the global messaging network for international payments. Other EU member states had initially been reluctant to do this, both because European lenders held most of the nearly $30 billion in foreign banks' exposure to Russia and because China had developed an alternative to SWIFT called CIPS; a weaponisation of SWIFT would provide greater impetus to the development of CIPS which, in turn, could weaken SWIFT as well as the West's control over international finance.[446][447] Other leaders calling for Russia to be stopped from accessing SWIFT include Czech president Miloš Zeman,[448] and UK prime minister Boris Johnson.[449]

Germany in particular had resisted calls for Russia to be banned from SWIFT, citing the effect it would have on payments for Russian gas and oil; on 26 February, the German foreign minister Annalena Baerbock and economy minister Robert Habeck made a joint statement backing targeted restrictions of Russia from SWIFT.[450][451] Shortly thereafter, it was announced that major Russian banks would be removed from SWIFT, although there would still be limited accessibility to ensure the continued ability to pay for gas shipments.[452] Furthermore, it was announced that the West would place sanctions on the Russian Central Bank, which holds $630bn in foreign reserves, to prevent it from liquidating assets to offset the impact of sanctions.[453]

Faisal Islam of BBC News stated that the measures were far from normal sanctions and were "better seen as a form of economic war." The intent of the sanctions was to push Russia into a deep recession with the likelihood of bank runs and hyperinflation. Islam noted that targeting a G20 central bank in this way had never been done before.[454] Deputy Chairman of the Security Council of Russia and former president Dmitry Medvedev derided Western sanctions imposed on Russia, including personal sanctions, and commented that they were a sign of "political impotence" resulting from NATO's withdrawal from Afghanistan. He threatened to nationalise foreign assets that companies held inside Russia.[455]

On the morning of 24 February, Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, announced "massive" EU sanctions to be adopted by the union. The sanctions targeted technological transfers, Russian banks, and Russian assets.[456] Josep Borrell, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, stated that Russia would face "unprecedented isolation" as the EU would impose the "harshest package of sanctions [which the union has] ever implemented". He also said that "these are among the darkest hours of Europe since the Second World War".[457] President of the European Parliament Roberta Metsola called for "immediate, quick, solid and swift action" and convened an extraordinary session of Parliament for 1 March.[458][459]

On 26 February, the French Navy intercepted Russian cargo ship Baltic Leader in the English Channel. The ship was suspected of belonging to a company targeted by the sanctions. The ship was escorted to the port of Boulogne-sur-Mer and was being investigated.[460]

The UK banned the Russian airline and flag carrier Aeroflot as well as Russian private jets from UK airspace.[210] On 25 February, Poland, Bulgaria, and the Czech Republic announced that they would close their airspace to Russian airlines;[461][462] Estonia followed suit the next day.[463] In response, Russia banned British airplanes from its airspace. S7 Airlines, Russia's largest domestic carrier, announced that it was cancelling all flights to Europe,[462] and US carrier Delta Air Lines announced that it was suspending ties with Aeroflot.[464]

Russia further banned from its airspace all flights from carriers in Bulgaria, Poland, and the Czech Republic.[465] Estonia, Romania, Lithuania, and Latvia announced they would also ban Russian airlines from their airspace.[466] Germany also banned Russian aircraft from its airspace.[467] On 27 February, the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that it had closed Portuguese airspace to Russian planes.[468] The same day, the EU announced that it would close its airspace to Russian aircraft.[393][469][470]

On 26 February, two Chinese state banks—the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, which is the largest bank in the world, and the Bank of China, which is the country's biggest currency trader—were limiting financing to purchase Russian raw materials, which was limiting Russian access to foreign currency.[471] On 27 February, Ignazio Cassis, the president of the Swiss Confederation, announced that the Swiss government was very likely to sanction Russia and to freeze all Russian assets in the country.[472] On February 28, Switzerland froze a number of Russian assets and joined EU sanctions. According to Cassis, the decision was unprecedented but consistent with Swiss neutrality.[473] On that same day, Monaco adopted economic sanctions and procedures for freezing funds identical to those taken by most European states.[474]

On 28 February, Singapore became the first Southeast Asian country to impose sanctions on Russia by restricting banks and transactions linked to Russia;[475] the move was described by the South China Morning Post as being "almost unprecedented".[476] The same day, South Korea announced it would participate in the SWIFT ban against Russia, as well as announcing an export ban on strategic materials covered by the "Big 4" treaties to which Korea belongs—the Nuclear Suppliers Group, the Wassenaar Arrangement, the Australia Group, and the Missile Technology Control Regime; in addition, 57 non-strategic materials, including semiconductors, IT equipment, sensors, lasers, maritime equipment, and aerospace equipment, were planned to be included in the export ban "soon".[477]